ABSTRACT

Objectives

Social care in the United Kingdom (UK) refers to care provided due to age, illness, disability, or other circumstances. Social care provision offers an intermediary step between hospital discharge and sufficient health for independent living, which subsequently helps with National Health Service (NHS) bed capacity issues. UK Health Technology Assessments (HTAs) do not typically include social care data, possibly due to a lack of high-quality, accessible social care data to generate evidence suitable for submissions.

Methods

We identified and characterized secondary sources of UK social care data suitable for research (as of 2021). Sources were identified and profiled by desk research, supplemented by information from custodians and data experts.

Results

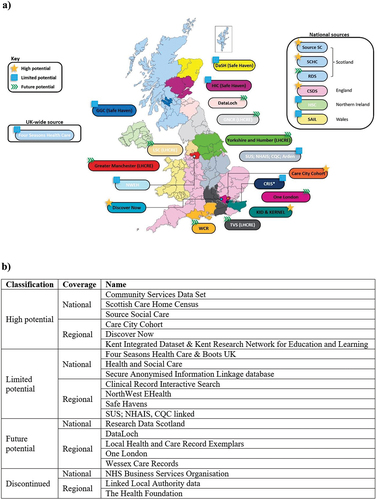

We identified twenty-one sources; six high potential (three national, three regional data sources), five future potential, seven limited potential, and three not considered further (outdated or lacking social care data).

Conclusion

Despite identifying numerous sources of social care data across the UK, opportunities and access for researchers appeared limited and could be improved. This would facilitate a deeper understanding of the clinical and economic burden of disease, the impact of medicines and vaccines on social care, enable better-informed HTA submissions and more efficient allocation of NHS and local council social care resources.

1. Introduction

Social care in the United Kingdom (UK) generally refers to care provided for persons who require such care due to age, illness, disability, or other circumstances [Citation1]. This care can be administered in community (e.g. community nursing), residential (e.g. care homes and nursing homes), or domiciliary (e.g. care at home, support workers, and occupational therapists) settings and may include services such as assistance with activities of daily living (such as dressing and washing) [Citation2] and reablement (supporting independent living after a period of illness or injury) [Citation3]. Social care plays a crucial role in care pathways by keeping people well for longer outside of hospital and enabling more rapid and safer discharges to home. However, public spending on adult social care in the UK has fallen by 9.9% between 2009/10 and 2016/17 [Citation1], although spending increased 4.8% in real terms from 2019/20 to 2020/21 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation4]. Despite this increase, a survey of health-care leaders across the National Health Service (NHS; survey closed in July 2022) concluded that there is unsustainable pressure on health and care services, driven in part by capacity challenges that affect social care. Most respondents to this survey believed that lack of a social care pathway was the primary cause of delayed discharge of medically fit patients, and that inadequate social care capacity had a significant impact on addressing the elective care backlog [Citation5]. Accordingly, social care is critical for ensuring UK NHS capacity and its ability to provide high-quality and safe care [Citation5]. Unlike services provided by the NHS, which are free at the point of access, access to publicly funded social care depends on the person’s needs and assets. Social care is funded by those who pay for their own care, local government, or a combination [Citation6]. However, the NHS provides short-term reablement services and funding to local authorities for continuing health care which is available for eligible persons with serious disability or illness [Citation7].

Health technology assessments (HTAs) are a multidisciplinary process that seek to determine the value of a health technology at different points in its lifecycle [Citation8]. Cost-effectiveness analyses conducted by HTA bodies in the UK, including The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England, impact access to health technologies such as medicines and vaccines. By improving health or preventing disease, medicines, and vaccines can reduce the clinical and economic burden of disease, which in turn may reduce the burden on the NHS and social care services.

Despite the importance of social care to the NHS, social care data are rarely used in HTAs in the UK. Social care resource use can be included in the base case of a cost-effectiveness model for NICE if the costs are directly incurred by the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS; social work or social care services outside the remit of health services, such as residential care homes) [Citation9]. Other costs that may be considered in a scenario analysis include those to government bodies other than the NHS (may be exceptionally included if agreed with Department of Health and Social Care [DHSC]); costs paid by patients not reimbursed by the NHS or PSS; productivity costs; and care by family members, friends, or a partner that might otherwise have been provided by the NHS or PSS. As local authorities fund most social care, with some services falling under other government bodies, e.g. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, instead of the DHSC, it remains unclear whether all types of social care would be included in the base case. A brief informal review conducted by the authors identified two recent NICE appraisals on therapies for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (HST9 and HST10) that included social care evidence in the base case [Citation10,Citation11]. The Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) does not have explicit requirements for inclusion of social care costs when making assessments of new medicines [Citation12]. The SMC states that costs should relate to those under the remit of NHS in Scotland and social work (equivalent to PSS in England); thus, the SMC adopts a similar approach to NICE [Citation13]. The SMC also solicits patient and carer input for its decision-making process, which may indirectly describe social care costs [Citation14]. Furthermore, the SMC acknowledges that finding social service costs for Scotland is challenging and providing English data is acceptable [Citation13]. The All Wales Medicines Strategy Group adopts NICE guidance when available and assesses the remaining new medicines not considered by NICE [Citation15]. The Department of Health in Northern Ireland is formally linked with NICE and reviews NICE guidance for local applicability [Citation16].

The limited consideration of social care data by HTA bodies in the UK may reflect a lack of sufficient evidence exacerbated by the limited availability of high-quality and accessible social care data across the UK suitable for research to inform appraisals by HTA bodies. For example, one of the appraisals for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis described above would have considered the cost of residential care in the base case had sufficient evidence been available [Citation10].

Given the financial pressures on adult social care and the importance of social care for NHS capacity, social care remains a key policy concern in the UK. Lack of, or limited consideration of, social care data by HTA bodies may preclude quantification of the clinical and economic burden of certain diseases on social care, which may ultimately determine if patients can access certain medicines or vaccines free of charge. The lack of social care data may also hinder efficient decision-making on preventive care and health care provided by the NHS. Understanding the availability and accessibility of social care data in the UK to researchers, including collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry for public health benefit, may facilitate evidence generation from a social care perspective by national and international researchers for both publicly and privately funded studies, help inform and support policy on health and social care provision at a government level, and improve the efficiency of limited health and social care resources. The aim of this research was to identify and characterize secondary sources of social care data in the UK suitable for research purposes to enable social care evidence generation for meaningful consideration in UK HTA appraisals.

2. Patients and methods

A protocol-driven, four-step approach was employed to identify and characterize potential sources.

2.1. Research planning

Search terms (Table S1) were developed based on key care settings and data requirements (contents) as defined in the protocol; search strings were developed from these search terms. Key care settings for the search were community, residential, and domiciliary care; key data requirements were health-care resource use, demographics, and diagnoses (). These key care settings and data requirements were considered by the authors to be essential variables required for research purposes. Beneficial care settings and data requirements represented desirable elements of a data source if found or available. The social care settings considered were intentionally broad so as to maximize the number of data sources initially identified whereby elements of social care are recorded, whilst HTA bodies may consider a wide range of social care services, and costs should data and evidence of sufficient quality exist.

Table 1. Source classification requirements.

2.2. Identification

Potential data sources were first identified from March to April 2021 via desk research of published and gray literature. Google Search and Google Scholar were used as the primary platforms for the identification and characterization of data sources. Additional platforms were used as necessary in a secondary capacity, including those directly describing specific data source characteristics (e.g. National Institutes of Health Data Sharing Resources/Repositories, NHS Digital Data Collections and Data Sets, Academic Research Data Repositories) and those indirectly describing data source characteristics through published research (e.g. PubMed, The Cochrane Library). A flexible approach was employed, and new search platforms of relevance discovered during this step were further investigated to identify additional data sources. A pragmatic and targeted approach with iterative improvement was employed; iterative improvements of the search strings were used until relevant results were no longer returned. Stopping rules for a given search engine or platform were pre-defined (Appendix S1).

2.3. Profiling, evaluation, and prioritization

Sources were assessed for social care settings and data attributes captured. A template and associated dictionary (Table S2) constructed by the authors based on previous research experience with secondary health/social care data were used to extract key information to determine the research potential. It was anticipated that not all fields would be retrieved/completed for each source. Once the key characteristics of each data source were extracted from the initial searches, the sources were classified into three tiers (level 1, high value; level 2, low priority; level 3, exclude) to inform the next phase of data custodian/expert outreach to obtain additional information, based on their likely utility and accessibility for research.

Level 1 sources met all key requirements to possibly enable social care research () and were investigated further; level 2 sources met most of the key requirements and were a potential source for further exploration; level 3 sources met few of the key requirements and were not further explored. As the social care data landscape in the UK was largely unknown at the start of this research, a flexible approach to the tiered classification criteria was employed; i.e. a source that met most key requirements but had an abundance of other beneficial requirements may be classified as level 1. A pragmatic approach was employed for level 2 sources, whereby further discussion among the authors reclassified level 2 sources as either level 1 (further investigation) or level 3 (exclusion). The level 1–3 classification scheme is subjective and based upon initial, likely, or perceived value (or combinations thereof) by the authors.

2.4. Interviews and gap resolution

Once data sources deemed of potential value (from initial searches only) were identified, they were extensively profiled based upon information extracted from the initial search and any additional searches. Subsequently, data custodians and experts associated with these data sources were contacted to enquire whether they could provide details on the characteristics of the database and to elicit outstanding information, validate desk research findings, and discuss potential for access or collaboration, including with the pharmaceutical industry. Conversations with data custodians were guided by a pre-specified set of questions. Multiple contacts per data source were contacted, up to a maximum of three times, to increase the likelihood of response. Custodian or expert knowledge supplemented the gaps in literature, which subsequently informed the value of key sources. Sources were subjectively classified as limited, high, or future potential for research purposes after discussion among authors and consideration of the knowledge obtained from the desk research and custodians or experts, including, but not limited to, care settings covered, data points captured, time period covered, data latency, accessibility, eligibility for linkage to other data sources, and previous research conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

Thirty unique search strings (Table S3) were used, which yielded 24 data sources. Some data sources were identified as ultimately being the same parent source and were therefore grouped. Of the 24 sources, 18 sources were prioritized for full profiling, i.e. likely of high value, after discussion among the authors (), with the remaining six sources excluded (Table S4).

Figure 1. Source selection process. Initial desk research identified 24 sources, of which 14 were initially classified as high priority, 4 as low priority, and 6 excluded. Following discussion among the authors, among the 4 low-priority sources, 2 were upgraded to high priority and the remaining 2 were combined and considered a single high priority source. Another source (Kent Integrated Care) was identified and included by the authors after the initial desk research and was considered a high-priority source. Eighteen high-priority sources remained at the conclusion of this process.

Availability of desirable data fields varied by data source based upon this initial search. Fields typically missing or unknown following the search included data refresh lag (approximate time from data entry to availability for analysis) and access route and fees. Fifty-eight custodians from 17 potential high-value sources (custodians from one high-value source not contacted due to existing relationship) were identified and contacted, of which 22 responded. Data discussions were held with custodians of 14 data sources; some custodians responded via e-mail with useful information, but a data discussion was either not warranted or forthcoming. There were 36 non-responders and five rejections.

A total of 21 sources remained at the completion of this process. From 18 initial sources, one source was upgraded from a grouped entry to an independent entry (DataLoch), and two further sources were identified with information from custodians (Care City Cohort, Research Data Scotland). These 21 sources were classified into three categories based on the authors’ subjective assessment of their potential suitability for research; five had future potential, seven had limited potential, and six had high potential (). Three sources were not pursued further as they were unlikely to have future research potential. Of these, one source did not actually collect or hold record-level data (the Health Foundation), and the remaining two sources were outdated based on information acquired from custodians (discontinued sources, ). The full characterization of all data sources identified in this research is available from the authors on request.

Figure 2. (a) overview and (b) breakdown of sources.

3.2. High-potential sources

Three national (Community Services Data Set [CSDS], Scottish Care Home Census [SCHC], Source Social Care [Source SC]) and three regional (Care City Cohort, Discover-NOW, linked Kent Integrated Dataset & Kent Research Network for Education and Learning [KID & KERNEL]) high-potential sources were identified. Details of each source are shown in (national sources) and (regional sources). Possible barriers and challenges associated with these sources included minimal/no published evidence of prior use, limited scope of data capture/lack of linkage to additional datasets, and access to data ()

Table 2. National level 1 (high potential) sources.

Table 3. Regional level 1 (high potential) sources.

Table 4. Barriers and challenges of high-potential sources.

3.3. Future potential sources

Sources considered to be of future potential were DataLoch, Research Data Scotland, KERNEL, Wessex Care Records, and other Local Health and Care Record Exemplars (Table S5). These sources were attempting to increase the availability of regional or national social care data to researchers, integrate social care with health-care data (i.e. established linkages), and/or widen the scope of social care data captured. These sources were generally still in development. However, they were considered to have future potential based on their objectives as described by the data custodians. Once the data availability, access route, and/or scope of social care data captured have been established, these sources may be suitable for research purposes in the future.

4. Discussion

This research identified six social care data sources in the UK (three in England; three in Scotland) with current high potential to facilitate research studies that were accessible to researchers in general, if the research need met the data governance requirements. Several other sources are anticipated to be of value in the coming years. All devolved nations had at least one national health-care source, albeit with varying social care coverage. When compared to those in England, data custodians of national sources in Scotland were more open to collaboration with industry (not limited to academic or public health institutions only) and were responsive and informative regarding opportunities for collaboration, and the data sources had transparent access routes. However, regional sources in England were eager to collaborate with industry and generally had flexible access (i.e. determined in a case-by-case basis) and extensive, established linkages. Regional sources in Scotland consisted of isolated pools of data in Safe Havens (platforms for the use of NHS electronic data in Scotland) [Citation17] with limited social care scope. Given existing research conducted by non-industry researchers, Care City Cohort may be one source ready for immediate collaboration with industry given its extensive linkages, established requirements for working with industry, and datasets that include hospital episode statistics.

Although this search identified numerous sources of social care data, the full utility of these sources for research purposes is unknown given the limited use in existing literature. While access routes may be transparent, there may also be challenges when accessing these sources in practice. For example, access to CSDS is via the NHS Digital Data Access Request Service, which can be a lengthy and comprehensive process that requires a legal basis (among other requirements) for a limited scope dataset. This may explain in part why no published studies using this source were identified in this search. Improving access is of benefit to researchers (primary research is both costly and time-consuming), patients (research findings inform patient care), and society (data can be more readily considered by government bodies). Difficulty in accessing social care data may in part explain the limited consideration of such data by the UK HTA bodies. Greater integration of social care data in HTA processes may not only better capture the social care impact on patients but also improve access to medicines and vaccines.

Some recommendations as to how these data sources could be improved for research purposes may be considered. Firstly, if data custodians were to ensure sources of social care data were more visible online, this would enable researchers to identify and comprehensively assess candidate data sources more quickly. Some data sources appeared promising but would be of limited value without linkage to other data sources for elements that would be of interest to HTA bodies, such as primary and secondary care data and comprehensive clinical data; of the six high-potential data sources, linkage to established external health data was feasible for four of the sources, with another source planning to accept linkages to such data in the future. Ready access to such integrated data would provide a more thorough picture of the patient journey and what services are accessed and when; this access would inform HTAs and consequently inform policy, ultimately improving care pathways. For example, the ability to link anonymized patient data collected from general practitioners to a range of secondary care and other health and area-based datasets is a feature of the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) [Citation18]. CPRD data have been used extensively for research purposes (over 3000 peer-reviewed publications over 30 years), and new linked datasets are added regularly to facilitate further research, such as those of the COVID-19 Hospitalisation in England Surveillance System and COVID-19 intensive care admissions of the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre [Citation18,Citation19]. HTA processes, access to medicines and vaccines, and ultimately UK society would benefit from reduced fragmentation across the social care data landscape, standardized, and simplified access procedures, connectivity between health and social care data, and transparency in permissions, costs, and time required to use and access such data. Standardized and transparent access schemes, such as those of the UK CPRD [Citation18], NHS Trusted Research Environment [Citation20], or NHS Hospital Episode Statistics [Citation21] may be suitable models; access to each of the six high-potential data sources identified here requires a lawful basis and clear indication of public benefit, suggesting access by the pharmaceutical industry is feasible. Routine data collection would minimize researcher and recall bias. The DHSC could be tasked with guaranteeing access and connectivity between social and health-care data and creating a standardized framework to social care data collection, which would facilitate incorporation of social care data in HTAs. This would enable a more holistic assessment of the burden of disease and the impact of new health technologies across health and social care settings. Given the current limitations in the quality and the availability of social care data, future NICE guidelines should propose acceptable proxies that could be used instead (to increase inclusion or consideration of social care data). These guidelines should also advise on how best to integrate social care data in HTAs once high-quality data are more available.

Several additional recommendations from a commentary on gaps in UK care home data may also be applicable here. These recommendations include use of standardized identifiers to allow linkage between data sources from different sectors; investment in large-scale, anonymized linked data analysis in social care in collaboration with academics; and a core national dataset developed in collaboration with key stakeholders to support integrated care delivery, service planning, commissioning, policy, and research [Citation22]. Recommendations from the Goldacre report on using health data for research and analysis, such as standardized data curation and coding practices, also warrant consideration [Citation23].

Integrated care systems (ICSs) were formally established in England on 1 July 2022 with the Health and Care Act 2022. Forty-two ICSs currently exist. ICSs are partnerships of organizations that plan and deliver joined health and care systems, with the goal of improving outcomes in population health and health care reducing inequality in outcomes, experience, and access, and enhancing productivity and cost efficiency [Citation24]. The regions covered by some ICSs overlap with some of the sources presented here. For example, the One London LHCRE is a collaborative of the five ICSs of London and the London Ambulance Service [Citation25]. One London aims to include electronic health records, imaging and pathology records, mobile and wearable data, and local authority and social care records. It is anticipated that several years will be required for this source to be functional and accessible [Citation26]. Given the remit of ICSs, it is crucial that they are well informed based on local, high-quality health and social care data. Collaboration with researchers, including industry, may provide suitable opportunities to accelerate proper data collection to better support decisions to improve health and economic growth. Moreover, a centralized data collection framework developed by the DHSC would ensure the standardization of all social care data collection by ICSs, thus increasing the research potential of these data.

The barriers and challenges of the sources identified in this research reflect some of the difficulties encountered by other researchers using UK social care data over the last decade. Knapp et al. had access to detailed electronic clinical records of over 3000 individuals with Alzheimer’s disease in London to identify predictors of care home and hospital admissions and associated costs. However, analyses were limited by what was available in the records-derived data set; the authors did not have comprehensive data on primary or community health or social care use [Citation26]. Bardsley et al. used data from a convenience sample of five primary care trust areas in England and their associated councils with social services responsibilities to construct models to predict intensive social care use. The limited accuracy of their models may have been due in part to the insufficient quality and completeness of the routine data collected. In addition, the social care data sets used were limited to assessments and services recorded by the local authority [Citation27]. Furthermore, in a study on antibiotic prescribing in UK care homes, Smith et al. analyzed data from administrative care home systems that were not designed for research (Four Seasons Health Care & Boots UK; Limited potential sources, ). Data on specific comorbidities, relevant risk factors, and antibiotic indication were not available [Citation28]. Moreover, both Witham et al. and Atherton et al. explored access to social care data and the value of linkage to health-care data in Scotland, but acknowledged the barriers that need to be overcome, such as data provenance and quality of data, as well as processes for data sharing and access [Citation29,Citation30]. The DHSC recently published a new health in data strategy aiming to reshape health and social care with data – in part to clear the backlog and apply learnings from the COVID-19 pandemic – which includes principles such as, improving data for adult social care, empowering researchers with the data they need to develop life-changing treatments and diagnostics, and developing the right technical infrastructure [Citation31]. However, it remains to be seen whether this strategy will result in higher quality or more accessible social care data in the UK for research.

This research has some limitations. The search strategy was not a systematic literature review or an exhaustive search of all possible combinations of relevant terms; it is possible that the search strategy employed would miss relevant sources. The classification of sources was based on subjective discussions, and some sources may be of greater or lesser value for research purposes than suggested by the classification provided. Some historical but nevertheless useful sources may have been missed by our search strategy. Given the non-response rate of the contacted custodians and data experts, it is likely that there remain some gaps and uncertainties in the sources presented here. As such, our findings are subject to publicly available information on social care data sources and the responsiveness, availability, and willingness of data custodians to share knowledge on each source for collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry. Nevertheless, this research provides an extensive overview of the social care data landscape in the UK, with desk research conducted to an approved search protocol. Information extracted via desk research was also validated and/or supplemented through interviews with data custodians, thus resulting in a more comprehensive profiling and understanding of each data source and associated potential.

5. Conclusion

This study identified several social care data sources that are currently suitable for research purposes or that may be suitable in the future should data availability, access route, and/or scope of social care data captured be established, and data custodians’ aspirations are achieved. However, there is still a need to improve the availability and the accessibility of social care data to researchers. Given the extreme cost and resource pressures on social care and the interdependence between social and health care, the ability to perform studies with comprehensive, high-quality, and readily accessible social care data may improve the efficiency and use of social care in the UK, allow for better integration of social care data in HTA processes, improve assessment of the impact of medicines and vaccines on social care, and ultimately save very limited financial and other resources.

Article highlights

Social care data are rarely used in HTAs in the UK, despite the importance of social care to the NHS

This may reflect the limited availability of high-quality and accessible social care data across the UK suitable for research

We employed a protocol-driven approach to identify, characterize, and appraise secondary sources of UK social care data suitable for research purposes

We found six data sources of social care data (three national; three regional) with high potential for research, and five sources with future potential (one national; four regional)

Key barriers or challenges to conducting research using the high potential sources included data access processes/methods, limited published evidence of prior use, and limited scope of data capture/lack of linkage to health and other data

Declaration of interest

D Mendes and S Collings are employees of Pfizer and hold stock or stock options of Pfizer.

R Wood and M Seif are employees of Adelphi Real World; Adelphi Real World received funds from Pfizer to conduct this research.

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in project conception and design, implementation of research, interpretation of findings, manuscript development, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (75.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eunmi Ha, Joe Thomas and Vicky Banks (all former employees of Adelphi Real World) for their contributions to the initial research and interpretation of findings; Tendai Mugwagwa and James Campling (employees of Pfizer Ltd.), and Susan Donaldson and Siobhan Ainscough (both former employees of Pfizer Ltd.) for their contributions to the conceptualization and interpretation of findings; Rachel Russell (of Pfizer Ltd.) for her contributions to the conceptualization, interpretation of findings and critical review of this paper; Derek Ho for drafting and finalizing the paper.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2023.2274843

Additional information

Funding

References

- Thorlby R, Starling A, Broadbent C, et al. What’s the problem with social care, and why do we need to do better? The Health Foundation, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust; 2018.

- The King’s Fund. Bite-sized social care: what is social care? 2017 [cited 2023 Jan 4th]. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/bite-sized-social-care-what-is-social-care

- Healthwatch. What is adult social care? 2021 [cited 2023 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.healthwatch.co.uk/advice-and-information/2021-10-07/what-adult-social-care

- The King’s Fund. Social care 360. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/social-care-360

- NHS Confederation. System on a cliff edge: addressing challenges in social care capacity. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.nhsconfed.org/publications/system-cliff-edge-addressing-challenges-social-care-capacity

- The King’s Fund. Bite-sized social care: how is social care paid for? 2017 [cited 2023 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/bite-sized-social-care-how-social-care-paid

- NHS. Care and support you can get for free. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/social-care-and-support-guide/care-services-equipment-and-care-homes/care-and-support-you-can-get-for-free/

- O’Rourke B, Oortwijn W, Schuller T, et al. The new definition of health technology assessment: a milestone in international collaboration. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020;36(3):187–190. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320000215

- Spicker P The personal social services. 2014 [cited 2023 Jan 5]. Available from: http://spicker.uk/social-policy/pss.htm

- NICE. Inotersen for treating hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. 2019 [cited 2023 Jan 27]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/hst9

- NICE. Patisiran for treating hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. 2019 [cited 2023 Jan 27]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/hst10/documents/html-content-3

- Scottish Medicines Consortium. New product assessment form. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 6]. Available from: https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/making-a-submission/

- Scottish Medicines Consortium. Guidance to submitting companies for completion of New Product Assessment Form (NPAF). 2022.

- Scottish medicines Consortium: a guide for patient group partners. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 6]. Available from: https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/making-a-submission1/

- Varnava A, Bracchi R, Samuels K, et al. New medicines in Wales: the all Wales medicines strategy group (AWMSG) appraisal process and outcomes. PharmacoEconomics. 2018;36(5):613–624. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0632-7

- Department Of Health. Circular HSC (SQSD) 12 22 - NICE technology appraisals - process for endorsement, implementation, monitoring and assurance in Northern Ireland. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 6]. Available from: https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/circular-hsc-sqsd-12-22-nice-technology-appraisals-process-endorsement-implementation-monitoring-and

- NHS Research Scotland. Data safe haven. [cited 2023 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.nhsresearchscotland.org.uk/research-in-scotland/data/safe-havens

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Clinical practice research datalink. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 5]. Available from: https://cprd.com/

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. CPRD linked data. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 25]. Available from: https://cprd.com/cprd-linked-data

- NHS. Trusted research environment service for England. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 5]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/coronavirus/coronavirus-data-services-updates/trusted-research-environment-service-for-england

- NHS. Hospital episode statistics (HES). [cited 2023 Jan 5]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/hospital-episode-statistics#top

- Burton JK, Goodman C, Guthrie B, et al. Closing the UK care home data gap - methodological challenges and solutions. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2021;5(4):1391. doi: 10.23889/ijpds.v5i4.1391

- Goldacre BM. Better, broader, safer: using health data for research and analysis. A review commissioned by the secretary of State for health and social care. Dept Health Soc Care. 2022;1–221.

- NHS England. What are integrated care systems? 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 6]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/integratedcare/what-is-integrated-care/

- One London. About OneLondon. [cited 2023 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.onelondon.online/about/

- Knapp M, Chua KC, Broadbent M, et al. Predictors of care home and hospital admissions and their costs for older people with Alzheimer’s disease: findings from a large London case register. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e013591. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013591

- Bardsley M, Billings J, Dixon J, et al. Predicting who will use intensive social care: case finding tools based on linked health and social care data. Age Ageing. 2011;40(2):265–270. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq181

- Smith CM, Williams H, Jhass A, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in UK care homes 2016-2017: retrospective cohort study of linked data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):555. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05422-z

- Witham MD, Frost H, McMurdo M, et al. Construction of a linked health and social care database resource–lessons on process, content and culture. Inform Health Soc Care. 2015;40(3):229–239. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2014.892491

- Atherton IM, Lynch E, Williams AJ, et al. Barriers and solutions to linking and using health and social care data in Scotland. Br J Soc Work. 2015;45(5):1614–1622. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcv047

- Department of Health and Social Care. New data strategy to drive innovation and improve efficiency. [cited 2023 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-data-strategy-to-drive-innovation-and-improve-efficiency

Appendix

Stopping rules Search terms were modified if the current search term did not yield a new source or information of interest within the top 30 publications published since 2016 (a filter was applied to discard publications prior to 2016). This stopping rule was implemented for each search engine or platform. Thus, approximately 30 abstracts or journal articles were evaluated before a search string was discarded (if it was clear after 20 publications that the search term yielded irrelevant results, the search term was discarded prior to the 30-publication point). The next combination of search terms was then subsequently employed.