ABSTRACT

Background

In 2011, the authors published an algorithm summarizing practice guidelines related to the use of long-acting antipsychotics (LAIs) called the Québec Algorithme Antipsychotique à Action Prolongée (QAAPAPLE), and proposed that it be revised every 5–10 years to update it according to most recent scientific knowledge. Therefore, a re-evaluation of the algorithm was conducted to determine which recommendations were still relevant and which needed modification.

Methods

The authors conducted a two-fold approach: a review of the literature to include new evidence since 2011 (controlled trials, meta-analyses, and practice guidelines); and a participatory component involving electronic surveys, conferences, encounters with opinion leadres, and patients’ representatives.

Results

Overall, prescribers tended to make decisions based on personal experience and conversations with colleagues rather than consulting evidence-based guidelines. To test if the algorithm was useful worldwide, it was presented in the United Arab Emirates, where the feedback was in agreement with the algorithm and its limitations.

Conclusions

Since its initial publication, the QAAPAPLE algorithm has been updated to guide clinicians on the use of LAIs. The new algorithm has also been assessed outside Canada to test its generalizability worldwide, and indicated its flexibility, efficiency, and user-friendliness in order to guide clinicians on the use of LAIs.

1. Introduction

In part one of the American Psychiatry Association (APA) practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, in the formulation and implementation of a treatment plan, one can sometimes find an algorithm that is an explicit description of the steps taken in the dispensation of patient care in specific circumstances [Citation1]. What is an algorithm? Some authors distinguish it from guidelines in the following way: guidelines are tactics whereas algorithms are strategies for implementing guidelines. These are the ‘instances of specific application of the guidelines’ [Citation2]. Those developed in the project ‘The Texas Medication Algorithm Project’ which began in 1996 represented the standard model of the algorithms [Citation3]. In this project, the algorithm represented a series of treatment steps, each of which is defined in turn by the clinical response of the patient to the previous step. The development of algorithms is largely based on expert consensus conferences. It is generally recognized that general practitioners use little practice guidelines, and it is even more evident with psychiatrists. If psychiatrists are informed of the existence of treatment guidelines, these are not often consulted when making clinical decisions [Citation4]. In our previous study in 2011 [Citation5], 0% considered that an algorithm is influential in their practice compared to 30% in 2017 [Citation6]. In addition, substantial change in practice has not constantly resulted from guideline publication. It is also recognized that the context of clinical practice must be taken into account.

2. QAAPAPLE

In 2011, we created and published an algorithm summarizing practice guidelines pertaining to the use of long-acting antipsychotics (LAIs) [Citation5]. Our expert committee proposed an algorithm (Québec Algorithme Antipsychotique à Action Prolongée, QAAPAPLE) LAIs as a result of a consensus reached by the four university psychiatry departments in Quebec, Canada [Citation5,Citation7]. Taking into account the frequency of non-adherence, heightened risk of relapse, and subsequent deterioration, our committee of experts strongly advised to increase LAIs prescriptions. At the time it was estimated that 15% to 25% of schizophrenia patients received LAIs prescriptions. The use of LAIs varied substantially according to the geographical region [Citation5].

In order to establish practice guidelines for prescribing and administering LAIs for treatment of first-episode psychosis and treatment-resistant psychosis, taking into account comorbidities and risk factors of non-adherence we suggested that it would be advisable to develop and disseminate recommendations based on the available epidemiological studies, randomized controlled trials, and naturalistic studies. For these reasons, the committee proposed the QAAPAPLE algorithm. In order to establish a consensus from the specialists from the departments of psychiatry of the 4 Quebec university medical school, we conducted a survey to examine percentages of LAIs prescription and reasons for prescribing antipsychotic treatment. All the Quebec psychiatrist were reached via an electronic survey sent by the Quebec Association of psychiatrists. Furthermore, to identify barriers and facilitators for prescribing LAIs, we examined the theoretical basis of the algorithm alongside the opinions of psychiatrists in the province of Quebec. In this sense, our approach contributes to knowledge transfer in psychiatry [Citation5]. The aim of this article is a narrative description of the methodology used to update the QAAPAPLE 1 algorithm, which was published in 2011. It provides opinions of how to develop and implement an algorithm. In the following sections, we describe the literature search and the series of different meetings organized to collect expert opinions, as well as surveys. This process led to developing QAAPAPLE 2 [Citation8].

3. QAAPAPLE revisited

Three relevant arguments form the basis of creating a second revised version of the QAAPAPLE algorithm. From the beginning of the process, we decided that an algorithm needs to be revised every 5 or 10 years and that a useful algorithm can be modified and improved. The first argument in favor for reviewing the algorithm is that it is necessary to update it according to current advanced scientific knowledge. The second argument, as with clinical practice guidelines, is that it is necessary to update the Algorithm as it is a crucial process for accumulating evidence of the reliability and validity of recommendations. The third, in line with the first and second arguments, proposes that creating valid recommendations can help to encourage and facilitate good clinical practices based on evidence and in this case the use of LAIs.

Taking into account new scientific data and relevant comments made by the prescribers, professionals, patients, and families concerned with LAIs formulations, a re-evaluation of the algorithm was conducted in order to determine which recommendations needed to be modified and which were still relevant. In addition, since 2012, other recommendations, practice guidelines, and other algorithms have been published and discussed across the globe [see 8 for synthesis].

4. Methodology

The chosen approach was threefold:

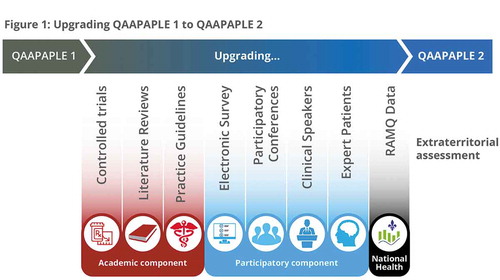

- University/Academic component: literature review including new evidence since 2011 (controlled trials, meta-analyses, and practice guidelines);

- Participatory component: psychiatric practice (electronic survey, participatory conferences aiming to present a new preliminary version of the algorithm and to gather comments of possible prescribers) and opinions from clinial experts as well as patients’ feedback.

- An extra-territorial component: An algorithm can be local, regional and it is appropriate for the clinical practice of physicians for a specific population [Citation9–12]. QAAPAPLE was created as a request from the association of Quebec psychiatrists, for the population of Quebec. We wanted to have a supplementary and additional assessment to test if such an algorithm could be useful worldwide in a very different context. The algorithm was presented, discussed, and modified in Canada and Europe (Belgium and France). We also presented it in the United Arab Emirates through another academic department of psychiatry at the United Arab Emirates University (UAEU).

4.1. Literature review

The various co-authors have each worked on different themes, reviewed the evidence through various selected publications (via PubMed electronic databases), including the latest literature reviews, guidelines, and meta-analyses on the use and effectiveness of LAIs [see 8] and collected administrative data from various centers in Quebec related to the use of LAIs [Citation13–15]. The systematic literature review was summarized in the article of QAAPAPLE 2.

Since our initial publication the number of publications, including meta-analyses and systematic reviews, have more than doubled thus improving the evidence supporting the use of LAIs [Citation9]. As a result, 15 meta-analyses were published from 2011 to 2018 from which we simply extracted the results (see Stip et al. 2019) [Citation8]. In short, instead of redoing a new meta-analysis, we have summarized all the conclusions of the meta-analyses to get the main directions of potential change of the algorithm. We did not perform a new meta-analysis. In addition, using a qualitative and selective literature review, the experts focused on several aspects related to the use of LAIs and the relevance of modifying the algorithm: 1) new data on LAIs (including polypharmacy and co-prescription with clozapine, dose frequency/interval); 2) perception and attitude regarding algorithms and evidence; 3) difficulties in implementing algorithms; 4) polypharmacy involving LAIs and co-prescriptions with clozapine; 5) expert patient perspectives on the algorithm. Based on quantitative findings, we noted a superiority of LAIs (in terms of relapse prevention and/or rehospitalisation) in observational studies [Citation9–31] and mirror studies but not in randomized controlled trials. The literature indicates specifications about using some drug associations as well as dose frequency and interval.

4.2. Participatory component

4.2.1. Conferences, lectures, and consensus meetings

To support the participatory component of the present QAAPAPLE algorithm review, we had inter-faculty expert-coauthoring meetings for the discussion and proposal, in the light of the literature review conducted by a variety of expert coauthors. During the initial discussions’ experts identified key elements that could influence the evolution of the algorithm, including the perception and attitude of psychiatrists regarding algorithms and evidence, as well as the difficulties of applying algorithms in a psychiatric environment.

Subsequently, 15 scientific presentations on the revision of the algorithm took place throughout the province of Quebec (Montreal, Quebec, Trois Rivières, Sherbrooke, Laurentians, Montérégie, Mauricie, Laval, and Outaouais), at the Quebec & Eastern Canada District Branch of the APA meetings and 7 presentations in France and Belgium where 360 clinicians participated. The sessions were as follows: a presentation on the construction of the algorithm, and the process of revising the algorithm, and then presented a modified version of QAAPAPLE. In doing so, participants could make comments, react later by e-mail, and suggest changes that were then discussed.

4.2.2. Survey

An anonymous electronic survey, similar to the previous one (distributed in 2011 to psychiatrists via the AMPQ) following the publication of the first version of QAAPAPLE, was distributed to Quebec psychiatrists by e-mail via the integrated university health network (RUIS)[see 8].

4.3. Extra-territorial component

The mission of the department of Psychiatry at the United Arab Emirates University is to meet the mental health needs of the United Arab Emirates and the community through providing an undergraduate educational program in psychiatry that meets international standards. It also strives to promote postgraduate training and continuing professional education in psychiatry, in partnership with other health-care providers in the country. Members of this academic department agreed to review and comment on the QAAPAPLE. A panel of experts who are faculty psychiatrist members of this academic department agreed to review and comment the QAAPAPLE algorithm. The process was the following: The expert panel (N = 6) was initially mailed relevant information about the QAAPAPLE algorithm and had a chance to review it and comment on it initially by return e-mail. The process involved a focus group within the academic department of psychiatry at the United Arab Emirates University followed by a regional focus group in the emirate of Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates.

5. Results

5.1. Results of the literature

LAIs have been developed mainly to improve adherence to medication in response to non-compliance found with oral antipsychotics. In addition to the traditionally available bi-monthly and monthly injections, longer intervals appeared on the market in quarterly or seasonal formulations (substantially reducing the number of visits required). This greater choice in terms of interval raises new issues such as: the frequency of visits, the role of the nurse with the increasing rarity of injections, the impact of these measures on the return to employment or education, and the decreased attention to pharmacological treatment in interviews. Overall, results suggest that administration of short intervals and high-frequency LAIs is more effective in the short term. Whereas, administering long-intervals of LAIs is more cost-effective and contributes to a better quality of life in the long run.

Amongst the literature, one study was instrumental because the data set was from a registry of the Quebec prescription of LAIs (RAMQ Registry) [Citation13,Citation15]. Thus, it was a good reflection of a real-life practice in Quebec per se. In this study, we measured the outcome of LAIs on clinical (relapse and re-hospitalization) and pharmacoeconomic consequences of these drug formulations. The data from the national RAMQ register allowed us to establish a portrait of the use of Quebec LAIs prescriptions.

From the survey, overall, prescribers tended to make decisions based on personal experience and conversations between colleagues rather than guideline based on evidence [see 8] ().

Figure 1. Upgrading QAAPAPLE 1 to QAAPAPLE 2

The QAAPAPLE algorithm was updated in 2018 after a consultation with clinicians throughout Quebec for the purpose of re-evaluation. This algorithm was adapted following a Registration with the Health Insurance Plan (RAMQ registry) study investigating thousands of patients who were prescribed LAIs [Citation15].

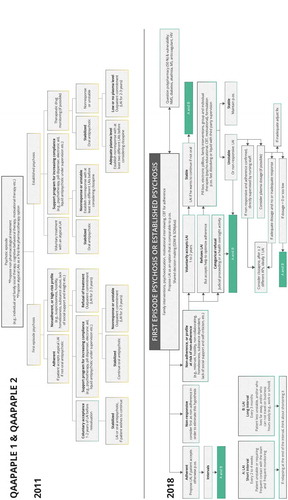

In addition, the shared decision making (SDM) has attracted a great deal of interest in mental health care over the course of the last decade. This interest has evolved to focus on the patient’s capacity to make informed decisions and involvement in the decision-making process of their treatment. Significant correlations have been established between SDM interventions and the improvement of knowledge, the participation of patients, and satisfaction of care. To date, a number of studies have assessed SDM interventions for several mental disorders, mainly schizophrenia and depression. Most of them have shown a positive effect on their satisfaction of their care. However, psychiatrists tend to exercise precaution and assume a more conservative position in involving patients in the decision-making process as a measure of reducing risk to the patient. Now that the SDMplus movement is starting to make its way to Canada, it would have been difficult not to revise our algorithm without including this new paradigm, regarding prescription and adherence to treatment. This has led us to propose that SDM and/or SDMplus should be initiated early on in the treatment planning. As a result, we have placed it at the very top of the algorithm ().

Figure 2. QAAPAPLE 1 and QAAPAPLE 2. LAI: Long Acting Injectable antipsychotic. (a) Short interval between injection; (b) long Interval between injection

From the extra-territorial assessment, one academic psychiatrist in child psychiatry underlined the lack of data to validate the algorithm, and she was not able to find any article or data looking into its use in the Middle-East region. There is also minimal evidence supporting its use. This comment was in agreement with the QAAPAPLE algorithm and its limitation was already documented in the publication. The process included the majority of prescribing clinicians familiar with local LAIs practices in the United Arab Emirates. A summary of the discussion was again emailed to them to review. This version was discussed in a workshop-like meeting that included a larger number oflocal clinical psychiatrists. Their feedback was taken into consideration. The discussions and statements were incorporated in a final agreed version which included the entirety of the deliberations before finalizing thedocument. The context of the law and of the community treatment orders are so different across countries that some arms of the algorithm require changes. There was a general agreement with the QAAPAPLE overall, although some of the changes proposed for the Arabic version require substantial variation and will be published separately in the near future. This is a good indication that an algorithm should be adjusted according to different cultures.

6. Discussion

An algorithm is not a dogma. Rather, it is a proposed route and process. Nine years ago, a committee of experts from Quebec’s four medical schools proposed this QAAPAPLE algorithm, linked to the use of LAI drugs. Since that first time, we have been able to examine changes in prescriptions, the literature, and better understand the use of the algorithm in interaction with psychiatrists in Quebec. We have drawn conclusions on the methodological issues related to clinical studies on LAIs and how to integrate them into best practices. Prescribers tend to make decisions based on personal experience and conversations between colleagues rather than considering an evidence-based guideline. This expert opinion raises doctors’ awareness of this algorithm and highlights its flexibility, efficiency, and user-friendliness in order to guide the use of LAI for psychotic disorders. Our expert approach is based on the idea that we reason by applying logical rules (deduction, classification, hierarchy, etc.). The systems designed on this principle apply different methods, based on the development of interaction models, syntactic and linguistic approaches, or development of ontologies (representation of knowledge). These models are then used by logical reasoning systems to produce new facts. We expect, with the involvement of community prescribers and mental health teams in the co-construction of an algorithm, to see a better relationship between evidence-based and practice-based medicine. The experience to work on this algorithm in Middle-East countries shows that its construct is relative to the local culture.

How could the advances or research being discussed impact real-world outcomes? Can changes be realistically implemented into clinical/research practice? What is preventing adoption in clinical practice?

There are three models for developing best practices based on evidence: the ‘evidence-based model,’ the ‘expert-consensus model,’ and a mixed model that depends on the nature of the object studied. Despite efforts to collect evidence, issues remain on what are the best practices in situations for which there is no clear evidence available. These deficiencies can be explained by three factors according to Kahn et al. [Citation32]. 1) the impossibility of developing a research model that measures all possible permutations of a disease; 2) the possibility that patients participating in the studies are not representative of clinical populations; 3) the fact that research is often done to demonstrate the superiority of an intervention compared to a placebo or other treatment models, instead of answering a more general question: among different treatment options:- what is the best way to treat a disorder? In the QAAPAPLE updating process, we took into account all kinds of design: randomized control trials (RCTs) included in the meta-analyses, observational and registry data set, surveys, and discussion following presentation, in different cultural and clinical settings.

We were aware that there are at least six methods for consensus building: 1) Consultations with experts chosen informally. The results of this method depend on the quality of the individuals who participate, their number being limited. In such a method, there is no systematic procedure followed or external review to validate the conclusions; 2) Large group conferences aimed at reaching consensus. This model brings together experts, non-experts, and consumers who discuss the literature review (in closed and open plenary sessions), who do a draft, then receive public comments, and rewrite the project after analysis of these comments; 3) groups of experts formally chosen. Some means have been foreseen to counter the influence on the discussions of certain personalities and external policies, corporatist, or not. The guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association are developed with this model; 4) Delphi groups. This method uses written questionnaires answered privately by the experts, without a group discussion, and the results of the group are then revised. The process can be repeated the number of times it is necessary to know if opinions converge. This survey can be done with or without a literature review and can be done by meetings or by mail or e-mail. This method is not without problems such as a tendency to compliance with emerging consensus. There is also the lack of reliability by using only nine experts to represent one or more disciplines. 5) The fifth method is based on a one-time mail or electronic survey to elicit a group opinion. A large number of experts are joined by this method. 6) For their part, the authors [Citation32] developed a sixth method to perform quantitative analysis of a postal survey. According to them, their method is an improvement for the following reasons: 1) it uses an enlarged group of experts; 2) it uses a mail or electronic survey so that respondents cannot influence each other; 3) it compares the opinions of research experts with those of practitioners; 4) it focuses on specific, important, and practical issues faced by practitioners; 5) It quantifies all results and provides the data in an easily understandable visual format, so that readers can easily determine the power of opinions. In the process of revisiting QAAPAPLE, more than 6 versions of the graphic presentation were presented and discussed. It was crucial to place well in the diagram the notion of Long Interval and Short Interval.

What are the key areas for improvement in the area being discussed and how can current problems and limitations be solved? Are there any technical, technological, or methodological limitations that prevent research from advancing as it could?

The algorithm now includes a new parameter: the influence of the inter-injection interval. The idea is to prescribe based on the interval and frequency that would most benefit a patient; this new questioning arises following the introduction to the market of therapeutic options administered every 2 weeks and every 3 months. We have thus modified the tree structure: high-frequency LAI – short interval and low-frequency LAI – long interval LAIs to allow a range of dosage intervals to be administered. Short intervals can be inconvenient for patients and staff. There are few clinical reasons for using them. Where a service user is prescribed a LAI with a short dosage interval consideration should be given to increase the interval. This can free up service user and staff time. Medication focused review can also lead to other benefits such as dosage reduction.

The possibility of no longer differentiating between established psychosis and the first episode in terms of using LAI has been widely discussed [Citation14,Citation32–36]. In Early Intervention programs in Quebec, the rate of implantation of LAI would reach up to 50% [Citation8].

At the top of the algorithm, we have specified the precautions to take for indications depending on the patient. Adverse reactions (e.g. extrapyramidal signs or neuroleptic malignant syndrome), and concomitant disorders (e.g. diabetes, HIV) and their treatments should be considered early on. For example, a neuroleptic malignant syndrome in the past should raise the question of the suitability of a long interval injection.

The co-use of LAI with clozapine is now included in the algorithm due to the latest observational data from Quebec [Citation13,Citation15].

What potential does further research hold? Is there a definitive end-point?

More research based on large data sets and registries are needed. The intensity of follow-up in RCTs may obscure the advantages of LAI over orals regarding compliance. Conflicting findings between RCTs and large observational studies may be a consequence of the methodological rigor of RCTs over observational studies.

Does the future lie in this area of research? Are there other promising fields of interest which could be progressed?

LAIs have been developed as a strategy to improve patient adherence, particularly in the management of schizophrenia. Significant proportion of individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders relapse during LAI formulation treatment. Since non-adherence to the antipsychotic maintenance treatment can affect up to half of people, relapse of psychosis can often be confused with interruption of treatment. The search for relapse during confirmed exposure to antipsychotics such as LAIs also needs to be studied. Studies with other populations than schizophrenia are needed since LAIs are prescribed in mood disorders as well. There is a need to explore better the LAIs' use in affective disorders and may be in other durable or recurrent psychosis with drug use disorder [Citation34–36]. Of note, those patients also require antipsychotics and might not be compliant to their drug regimens. How to justify LAIs to insurance companies, given that almost all LAIs are not registered for disorders other than schizophrenia? This field of research is a work in progress, and we are planning to use the Quebec registry to explore the actual prescription of LAIs for different indications than schizophrenia per se.

How will the field evolve in the future? What will the standard procedure have gained or lost from the current norm in five or ten years?

In the development of new LAI formulations, we will see an extension of the interval up to 6 months or 12 months. So, the patient profile should be better defined according to the length of the interval.

A speculative viewpoint on how the field will have evolved five years from the point at which the review was written.

The so-called ‘expert systems’ and symbolic approach will help the decision about the choice about a LAI for a specific patient. Some interval between injections will vary between 2 weeks to 6 months or 1 year. Algorithms qualified as decision support, knowledge management, or e-health will be more sophisticated. They will benefit from better reasoning models as well as better techniques for describing medical knowledge, patients, and medical procedures. Whilst the mechanics of algorithms is basically the same, language representation tends to become more efficient over time and technological innovation more empowering. To be acceptable or legitimate, or even to be discarded as deemed irrelevant, the decisions of the algorithm must be clearly understood, and therefore explained as neatly as possible. For instance, polypharmacy is very common with LAIs [Citation13,Citation15] and it adds complexity to prescribing choices. A major advantage of algorithms such as the one proposed here, is to provide guidance to clinical reasoning based on knowledge on LAI. In the future, it is conceivable that Artificial Intelligence will be able to interact directly with prescribers to facilitate decision making.

7. Conclusion

Since our initial publication, interacting with Quebec psychiatrists, we have examined changes in prescription and literature to better understand the use of our QAAPAPLE algorithm [Citation8]. The committee has updated the QAAPAPLE algorithm to guide clinicians in using LAIs along the path of patients with psychosis as early as the first episode and through different clinical settings in order to have a more flexible and user-friendly treatment. Since the publications of the second version of the algorithm, new literature has emerged on first episode psychosis [Citation14,Citation33,Citation37,Citation38], and studies have been published from provinces other than Quebec describing trends of LAIs prescriptions. We exposed the new algorithm to objective appraisal of its supporting evidence, in a very different country such as the United Arab Emirates to test the global value of the process. Finally, the process of revising QAAPAPLE has contributed to educate doctors about the algorithm, its flexibility, efficiency, and user-friendliness in guiding the use of LAIs for psychotic disorders.

8. Expert opinion

Evidence based algorithms require to be regularly updated to reflect changes in prescribing trends and incorporate newly available evidence. In this work the authors describe the process leading to the update of the QAAPAPLE algorithm, first developed in Canada to guide clinicians in the use of long acting anti-psychotic medication. The new version of QUAAPALE is based on international consensus and offers an inclusive view of clinically meaningful, evidence-based best practice.

Article highlights

LAIs remain an underused therapeutic modality, an updated algorithm can help clinicians to find their way around treatment options to facilitate use.

The injection frequency palette allows intervals of 2 weeks to 3 months, which allows adjustment to the patient's needs in terms of clinical stability and frequency of contact.

Observational studies show that LAIs reduce relapses, re-hospitalizations and excess mortality.

An algorithm needs to be revised every 5 or 10 years and a useful algorithm can be modified and improved.

Declaration of interest

E Stip received fees for lecturing, advisory board work, and traveling and MA Roy received fees for lecturing from Janssen-OtsukaCanada, Lunbeck Canada. E Stip, MA Roy, S Grignon, and D Bloom received fees from the AMPQ for the first version of the QAAPAPLE. E Stip and MA Roy received funding from CIHR and FRQS. D Arnone has received travel grants from Jansen-Cilag and Servier and sponsorship from Lundbeck. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

A peer reviewer on this manuscript has received honoraria from most companies manufacturing second-generation antipsychotics, including LAIs. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the department of psychiatry of University of Montreal for funding the project for QAAPAPLE2 and the CHUM Foundation.

Additional information

Funding

References

- McIntyre JS, Charles S, Anzia D, et al. 2010. Practice guideline for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 2nd ed. APA. Jun 2006. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/psychevaladults.pdf

- Toprac MG, Rush AJ, Conner TM, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project and patient and family education program: a consumer-guided initiative. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(7):477–486.

- Chiles JA, Miller AL, Crismon ML, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: development and implementation of the schizophrenia algorithm. Psychiatric Serv. 1999;50:69–74.

- Mellman TA, Miller AL, Weissman EM, et al. Evidence-based pharmacologic treatment for people with severe mental illness: a focus on guidelines and algorithms. Psychiatric Serv. 2001;52(5):619–625.

- Stip E, Abdel-Baki A, Bloom D, et al. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: an expert opinion from the Association des médecins psychiatres du Québec. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(6):367–376.

- Healy DJ, Goldman M, Florence T, et al. A survey of psychiatrists’ attitudes toward treatment guidelines. Community Ment Health J. 2004;40(2):177–184.

- Zhornitsky S, Stip E. Oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia and special populations at risk for treatment nonadherence: a systematic review. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2012;2012(12):1–12.

- Stip E, Abdel-Baki A, Roy M-A, et al. Long-acting antipsychotics: the QAAPAPLE algorithm review. Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(10):697–707.

- Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. Patients with early-phase schizophrenia will accept treatment with sustained-release medication (Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics): results from the recruitment phase of the PRELAPSE trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(3). DOI:10.4088/JCP.18m12546.

- Lee K. The long-acting injectable antipsychotics in clinical practice. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2019;58(1):29–37.

- Arango C, Baeza I, Bernardo M, et al. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia in Spain. Revista de Psiquiatríay Salud Mental (English Edition). 2019;12(2):92–105.

- Kim HO, Seo GH, Lee BC. Real-world effectiveness of long-acting injections for reducing recurrent hospitalizations in patients with schizophrenia. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):1–7.

- Lachaine J, Lapierre ME, Abdalla N, et al. Impact of switching to long-acting injectable antipsychotics on health services use in the treatment of schizophrenia. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2015;60(3 Suppl 2):S40.

- Abdel‐Baki A, Thibault D, Medrano, et al. Long‐acting antipsychotic medication as first‐line treatment of first‐episode psychosis with comorbid substance use disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2020;14(1):69–79.

- Stip E, Lachaine J. Real-world effectiveness of long-acting antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 3957 patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and other diagnoses in Quebec. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2018;8(11):287–301.

- Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(6):603–609.

- Kishimoto T, Robenzadeh A, Leucht C, et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Schizophr Bull. 2012;40(1):192–213.

- Kishi T, Oya K, Iwata N. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(9):pyw038.

- Kirson NY, Weiden PJ, Yermakov S, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of depot versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: synthesizing results across different research designs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):568–575.

- Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957–965.

- Fusar-Poli P, Kempton MJ, Rosenheck RA. Efficacy and safety of second-generation long-acting injections in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;28(2):57–66.

- Cameron C, Zummo J, Desai D, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole lauroxil once-monthly versus aripiprazole once-monthly long-acting injectable formulations in patients with acute symptoms of schizophrenia: an indirect comparison of two double-blind placebo-controlled studies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(4):725–733.

- Misawa F, Kishimoto T, Hagi K, et al. Safety and tolerability of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled studies comparing the same antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):220–230.

- Ostuzzi G, Bighelli I, So R, et al. Does formulation matter? A systematic review and meta-analysis of oral versus long-acting antipsychotic studies. Schizophr Res. 2017;183:10–21.

- Pae CU, Wang SM, Han C, et al. Comparison between long acting injectable aripiprazole versus paliperidone palmitate in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic review and indirect treatment comparison. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(5):235–248.

- Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Nitta M, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Schizophrenia Bull. 2017;44(3):603–619.

- Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822–829.

- La¨hteenvuo M, Tanskanen A, Taipale H, et al. Real-world effectiveness of pharmacologic treatments for the prevention of rehospitalization in a Finnish nationwide cohort of patients with bipolar disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):347–355.

- Taipale H, Mehta¨la¨ J, Tanskanen A, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs for rehospitalization in schizophrenia – a nationwide study with 20-year follow-up. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1381–1387.

- Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2017 Jul;197:274–280.

- Leucht C, Heres S, Kane JM, et al. Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia – a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1–3):83–92.

- Kahn DA, Docherty JP, Carpenter D. Consensus methods in practice guideline development: a review and description of a new method. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(4):631–639.

- Barnes TR, Drake R, Paton C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2020 Jan;34(1):3–78. DOI:10.1177/0269881119889296. Epub 2019 Dec 12. PMID:31829775.

- Ostuzzi G, Barbui C. Comparative effectiveness of long-acting antipsychotics: issues and challenges from a pragmatic randomised study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25:21–23.

- Kurata T, Hashimoto T, Suzuki H. Concurrent, successful management of bipolar I disorder with comorbid alcohol dependence via aripiprazole long‐acting injection: a case report. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2019;39:238–240.

- Keramatian K, Chakrabarty T, Yatham LN. Long-acting injectable second-generation/atypical antipsychotics for the management of bipolar disorder: a systematic review. CNS Drugs. 2019;33:431–456.

- Kane JM, Agid O, Baldwin ML, et al. Clinical guidance on the identification and management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80:12123.

- Gorwood P, Bouju S, Deal C, et al. Predictive factors of functional remission in patients with early to mid-stage schizophrenia treated by long acting antipsychotics and the specific role of clinical remission. Psychiatry Res. 2019;281:112560.