ABSTRACT

Introduction

Negative symptoms in schizophrenia are associated with poor response to available treatments, poor quality of life, and functional outcome. Therefore, they represent a substantial burden for people with schizophrenia, their families, and health-care systems.

Areas covered

In this manuscript, we will provide an update on the conceptualization, assessment, and treatment of this complex psychopathological dimension of schizophrenia.

Expert opinion

Despite the progress in the conceptualization of negative symptoms and in the development of state-of-the-art assessment instruments made in the last decades, these symptoms are still poorly recognized, and not always assessed in line with current conceptualization. Every effort should be made to disseminate the current knowledge on negative symptoms, on their assessment instruments and available treatments whose efficacy is supported by research evidence. Longitudinal studies should be promoted to evaluate the natural course of negative symptoms, improve our ability to identify the different sources of secondary negative symptoms, provide effective interventions, and target primary and persistent negative symptoms with innovative treatment strategies. Further research is needed to identify pathophysiological mechanisms of primary negative symptoms and foster the development of new treatments.

1. Introduction

Negative symptoms represent a fundamental clinical aspect of schizophrenia [Citation1–4]. They are associated with scarce response to available treatments, and poor quality of life and functional outcome [Citation5–14]. Therefore, they represent a substantial burden for patients, relatives, and health-care systems, and remain an unmet need in the care of people with schizophrenia [Citation1,Citation2,Citation15,Citation16].

The last decades have testified important advances in the clinical characterization of negative symptoms which, however, remain poorly recognized and not always evaluated according to current definitions and conceptualizations both in research and clinical settings [Citation1].

In this manuscript, we will provide clinicians with an update on the conceptualization, assessment, and treatment of this complex and often neglected psychopathological dimension of schizophrenia. For this narrative review, we searched the pertinent literature on PubMed until January 2022, focusing on systematic reviews and original studies published in the last 5 years. Other older reviews and landmark studies were selected from the reference list of these more recent papers.

2. Burden of negative symptoms

Negative symptoms represent a reduction in normal behaviours and functions. For some of them, i.e. avolition, anhedonia, and asociality, the reduction involves motivation and interest; for others, i.e. blunted affect and alogia, it is relevant to expressive aspects of mental life [Citation1,Citation3,Citation17]. Fifty percent of subjects with schizophrenia have at least one negative symptom of moderate severity and approximately 10–30% of them experience two or more negative symptoms [Citation1]. A greater severity of negative symptoms has been reported in males, as compared to female subjects with schizophrenia [Citation18–21].

The huge burden of these symptoms depends mostly on their ‘direct’ or ‘indirect’ (e.g. through resilience, internalized stigma, service engagement) impact on different domains of real-life functioning. Indeed, they limit patient’s abilities to live independently, work, study, perform daily activities, be socially active, and maintain personal relationships [Citation5–14]. Unfortunately, limited treatment options are available for the care of negative symptoms, especially when they are primary and enduring.

Negative symptoms might be present since the early phases of the illness, in first-episode psychosis (FEP), and in at-risk states for psychosis (HR) and show an elevated stability along the course of the illness [Citation22–25]. In the early phases of the disorder [Citation18,Citation19,Citation26,Citation27], as well as in high-risk states [Citation28] a gender difference has been reported, with males experiencing more severe negative symptoms, as compared to females. In FEP subjects, negative symptoms are associated with poor premorbid functioning, increased risk of deliberated self-harm [Citation26,Citation27,Citation29,Citation30], scarce treatment adherence [Citation31], poor quality of life, and functional outcome [Citation32,Citation33], the latter one reported as poor up to 7 years after the first presentation to psychiatric services [Citation34,Citation35]. In subjects at risk of psychosis, negative symptoms emerge before the attenuated psychotic symptoms [Citation36–39] and have a higher prevalence than the positive ones [Citation38,Citation40,Citation41]. Severity of negative symptoms in these subjects is associated with the risk of conversion to psychosis [Citation40,Citation42–45], as well as with poor functioning [Citation1,Citation41–43,Citation46–52].

In the light of these observations, negative symptoms have become an important focus for the development of new treatments.

3. Conceptualization and classification of negative symptoms

3.1. Negative symptoms domains

According to current views, negative symptoms include (1) blunted affect, i.e. a reduction in the expression of emotions, characterized by diminished facial and vocal expression, as well as body gestures; (2) alogia, i.e. a reduction in quantity of words spoken and amount of spontaneous elaboration; (3) avolition, i.e. a reduction in the ability to initiate and persist in goal-directed activities, due to a lack of motivation; (4) asociality, i.e. a reduction in the drive to engage in relationships with a consequent reduction of social interactions; and (5) anhedonia, i.e. a reduction in the ability to experience pleasure for current events (consummatory anhedonia) or for future anticipated activities (anticipatory anhedonia) [Citation53] (). While several studies reported deficits in the anticipation of pleasure both in the early stages and chronic phase of the disease, it is controversial whether non-depressed subjects with schizophrenia experience consummatory anhedonia [Citation54–63]. However, the use of first-generation rating scales, which are unable to discriminate between anticipatory and consummatory anhedonia, has hampered the clarification of this issue [Citation1,Citation64–68].

Table 1. Definitions of negative symptoms [Citation53].

Several factor analytic studies, using different assessment scales, demonstrated that negative symptoms in subjects with schizophrenia cluster in two domains: the Experiential domain, consisting of avolition, anhedonia, and asociality, and the Expressive domain, consisting of blunted affect and alogia [Citation1,Citation69–73]. More recently, it has been shown that a five-factor model reflecting the five individual negative symptoms and a hierarchical model (five individual negative symptoms as first-order factors and the two factors, Experiential and Expressive, as second-order factors) provide a better fit as compared with the two-factor solution [Citation74–79]. However, these findings need replications. The two-factor solution is supported by the evidence that the two factors (Experiential and Expressive) show different behavioral and neurobiological correlates, as well as different clinical and social outcomes [Citation17]. Some studies have shown that the Experiential domain has a greater impact on real-world functioning than the Expressive one [Citation7,Citation9–11,Citation22,Citation59,Citation80–83].

The factor structure of negative symptoms in FEP and HR subjects is much more controversial, since most studies used scales adapted from the adult population and/or scales not in line with the current conceptualization of negative symptoms [Citation39,Citation43,Citation84–96].

Some studies using either the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [Citation97] or the Scale for the Assessment of Positive/Negative Symptoms (SAPS/SANS) [Citation98,Citation99] analyzed the scale as a whole and reported a unidimensional structure of negative symptoms in FEP subjects [Citation84–86]. However, the inclusion of aspects that are not conceptualized as negative symptoms limits the interpretation of these results. Very few studies used the same scales to investigate the factor structure of negative symptoms in FEP and focused on the negative scale or subscales only [Citation87–90]. In particular, one study [Citation87] conducted a factor analysis on the SANS and found a three-factor model of negative symptoms in first episode schizophrenia subjects (FES): the Expressive factor (including the SANS item ‘Poverty of Speech’ and the SANS ‘Affective Flattening’ subscale without the item ‘inappropriate affect’ which was not included in the analysis), the Experiential factor (including the SANS ‘Anhedonia-Asociality’ and ‘Avolition/Apathy’ subscales), and the Alogia/Inattention factor (including the SANS ‘Attention’ subscale and the items ‘Poverty of Content of Speech’, ‘Blocking’ and ‘Increased latency of Response’) [Citation87]. However, the authors included in their analysis the attention subscale and the item poverty of content of speech, which evaluate aspects related to cognitive impairment and disorganization but not to negative symptoms as currently conceptualized [Citation1].

A recent study [Citation88] conducted in FES supported a two-factor solution of negative symptoms evaluated with the PANSS: an Experiential factor, including the PANSS items ‘Poor Rapport’, ‘Passive/Apathetic Social Withdrawal’, ‘Active Social Avoidance’ and ‘Lack of Spontaneity’, and an Expressive factor, including PANSS items ‘Blunted Affect’, ‘Emotional Withdrawal’ and ‘Motor Retardation’. Only the Expressive factor correlated with the functioning as measured with the Global Assessment Scale. However, the results are inconsistent with a large literature body that reported an association of the Experiential factor with the impairment of functioning [Citation17,Citation100–102]. The same research group conducted two other factor analytic studies and found that a three-factor solution was more appropriate in FES whereas a two-factor solution was more appropriate in FEP without schizophrenia-spectrum disorders [Citation89,Citation90]. However, the interpretation of these results is limited by the inclusion of some aspects, such as motor retardation and active social avoidance, which currently are not conceptualized as negative symptoms. Indeed, these symptoms are related to other clinical features: motor retardation may be due to extrapyramidal symptoms or depression and active social avoidance to social anxiety or suspiciousness/persecutory delusions [Citation1].

As to the negative symptom structure in HR populations, some studies using either the Comprehensive Assessment of the At-Risk Mental State (CAARMS) [Citation103] or the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes (SIPS) [Citation104] analyzed the scale as a whole and reported a unidimensional structure of negative symptoms [Citation39,Citation43,Citation95,Citation96]. However, the inclusion of aspects other than negative symptoms might have influenced the results. Very few studies, on the other hand, examined the factor structure of negative symptoms in HR populations focusing on the negative symptom scale or subscale only [Citation52,Citation91–94].

A confirmatory factor analysis, conducted on the PANSS negative items, showed a two-factor structure for both schizophrenia and HR subjects: an Expressive and an Experiential factor [Citation91]. The latter predicted functioning in both groups at one-year follow-up. However, the authors used the PANSS, a scale developed for adult psychosis populations, and included motor retardation and active social avoidance, which currently are not conceptualized as negative symptoms [Citation1]. Another study [Citation92] using the SIPS supported the two-factor solution of negative symptoms: an Expressive factor (expression of emotions, experience of emotions, and social anhedonia) and an Experiential factor (occupational functioning and avolition). The latter was strongly correlated with role functioning while the Expressive factor showed only a weak correlation. However, the authors included in their analysis the occupational functioning, an aspect that is not conceptualized as a negative symptom and is in overlap with the role functioning. A more recent study conducted in children and adolescents at ultra-high risk to develop psychosis, using the SIPS without considering the occupational functioning, found a two-factor solution of negative symptoms: an Expressive factor (expression of emotions, experience of emotions and ideational richness) and an Experiential factor (avolition and social anhedonia), and also found a strong correlation of the latter with role functioning [Citation52].

Finally, two studies [Citation93,Citation94] used the Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS) [Citation105] for the evaluation of negative symptoms in HR subjects. The exploratory factor analysis [Citation93] supported the two-factor solution of negative symptoms, with the Experiential factor correlating with functioning. The confirmatory factor analysis [Citation94] showed that the 5-factor model provided a better fit, as compared to the two-factor model.

Given the high heterogeneity of negative symptoms, factor analytic studies using scales in line with the current conceptualization of negative symptoms are hence crucial for an optimal management of negative symptoms especially in FEP and HR populations.

3.2. Primary and secondary negative symptoms

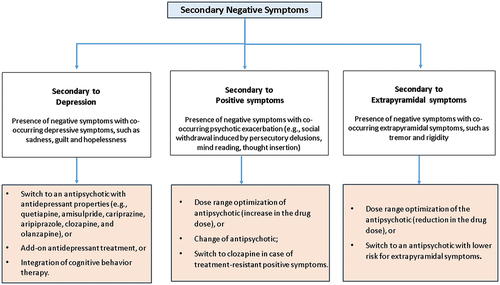

An important aspect of the conceptualization of negative symptoms, too often neglected by current research and clinical practice, is the differentiation between primary and secondary negative symptoms. While primary negative symptoms are a core feature of the disorder, whose pathophysiology remains to be clearly identified, secondary negative symptoms are due to factors other than the disorder itself, such as positive symptoms, depression, iatrogenic parkinsonism or environmental hypostimulation [Citation1,Citation17,Citation106–108]. This distinction has important clinical implications, both from a therapeutic and a prognostic perspective. In fact, primary negative symptoms tend to be persistent and treatment resistant [Citation1,Citation17,Citation107,Citation109], while factors underlying secondary negative symptoms can be often identified and effectively treated, leading to an improvement of the symptomatology and, consequently, of functional outcome. The identification of sources of secondary negative symptoms is sometimes difficult and may require a longitudinal observation that, especially in first-episode subjects is not always feasible. The secondary nature of observed negative symptoms might be suggested by the presence of negative symptoms during periods of psychotic exacerbation or co-occurring with depressive symptoms or following changes in pharmacotherapy. For instance, clinicians should evaluate whether negative symptoms, e.g. the social withdrawal, might be induced by persecutory delusions, mind reading, thought insertion, other psychotic symptoms, or depression. The presence of sadness, hopelessness and guilt should be evaluated since it might suggest that the negative symptomatology could be secondary to depression. Similarly, changes in antipsychotic treatment and concomitant occurrence of extrapyramidal side effects and negative symptoms strongly suggest that both are due to the antipsychotic drug treatment: an augmentation of the drug dose might induce the occurrence or increase in the severity of some extrapyramidal signs, such as hypomimia, which might be regarded as blunted affect. A standard clinical examination aimed to evaluate the presence of other extrapyramidal signs, such as tremor or rigidity to rule out or diagnose drug-induced parkinsonism may clarify the picture.

3.3. Transient and persistent negative symptoms

Negative symptoms may be transient or persistent over time. The presence of at least two primary and persistent negative symptoms (for at least 12 months including periods of clinical stability) is the basis for the diagnosis of Deficit Schizophrenia (DS), regarded by some researchers as a separate disease entity with respect to non-deficit schizophrenia (NDS). This distinction has clinical implications since subjects with DS, in comparison with subjects with NDS, show a greater impairment of neurocognitive and social cognition abilities, a poorer response to treatment and a worse outcome [Citation107,Citation108,Citation110–118]. To date, the Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (SDS) [Citation119] is the gold standard instrument for the diagnosis of DS. However, to correctly address the differentiation between DS and NDS, clinicians need to conduct a careful longitudinal evaluation, which is particularly difficult especially in subjects with a first-episode psychosis, thus limiting the use of this construct in clinical settings and stimulating the formulation of alternative constructs, such as the ‘persistent negative symptoms’ construct, that refers to the presence of negative symptoms of at least moderate severity for at least 6 months [Citation53,Citation112] (). Persistent negative symptoms are associated with a prolonged duration of untreated psychosis, poor patient functioning and worse quality of life [Citation1,Citation109]. Compared to the DS construct, this concept shows several advantages, since it identifies a larger patient population and requires a shorter longitudinal observation. In clinical trials, also the ‘predominant negative symptoms’ and ‘prominent negative symptoms’ constructs () have been used to describe the severity of negative symptoms, without looking at their persistence. However, the use of these constructs should be improved, as their definitions are inconsistent across studies and standardized methods for ruling out possible confounding factors (i.e. positive symptoms, depression and extrapyramidal symptoms) are rarely used [Citation1].

Table 2. Criteria for ‘persistent negative symptoms’, ‘predominant negative symptoms’, and ‘prominent negative symptoms’ [Citation1].

4. Assessment instruments for the evaluation of negative symptoms

An accurate evaluation of negative symptoms, including both quantitative (frequency, duration, and intensity) and qualitative aspects (such as differentiation between anticipatory and consummatory aspects of anhedonia, or differentiation between behavioral and experiential aspects) requires the use of validated instruments.

First-generation assessment tools, developed before the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) consensus initiative on negative symptoms [Citation53], such as the PANSS [Citation97] and the SANS [Citation98], include features which at that time were erroneously regarded as negative symptoms, such as disorganization and cognitive impairment or aspects largely overlapping subject’s psychosocial functioning. In fact, PANSS negative subscale includes stereotyped thinking, a psychopathological feature part of the disorganization dimension, and difficulty in abstract thinking, relevant to the cognitive dimension. In some studies, the PANSS items ‘motor retardation’ and ‘active social avoidance’ were included within the negative symptoms factor [Citation1]; of course, these symptoms are not conceptualized as negative symptoms any longer, as they more often reflect other aspects: motor retardation may be due to extrapyramidal symptoms or depression, and active social avoidance to social anxiety or suspiciousness/persecutory delusions. The SANS includes the attention subscale in the evaluation of negative symptoms, and current conceptualizations require the exclusion of cognition-related items from instruments aimed to assess negative symptoms; it includes also other items, such as ‘poverty of content of speech’, and ‘inappropriate affect’, which are relevant to the disorganization dimension [Citation1]. Furthermore, the PANSS does not evaluate avolition and anhedonia, while the SANS rates together anhedonia and asociality, and does not distinguish between anticipatory and consummatory anhedonia [Citation120]. Finally, both PANSS and SANS focus on behavioral observation as opposed to internal experiences in the assessment of negative symptoms. For instance, the SANS evaluates asociality through the observed behavior without considering the environment in which the subject lives and the desire to have social relationships [Citation1].

The introduction of second-generation clinician-rated scales, such as the BNSS [Citation105,Citation121] and the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS) [Citation122] has been instrumental to overcome these limitations. Both BNSS and CAINS are in line with the current conceptualization of negative symptoms, as they do not include symptoms relevant to other psychopathological dimensions or functioning [Citation1,Citation3,Citation17,Citation105,Citation121,Citation122]; both scales take into account subject’s internal experiences together with observed behaviors and provide a separate assessment of consummatory and anticipatory anhedonia. In particular, the BNSS provides separate ratings for internal experiences and observed behaviors. Both BNSS and CAINS have been translated and validated into several languages and showed high validity across different countries/languages [Citation1,Citation15,Citation121,Citation123–133]. A recently validated self-assessment instrument, the Self-evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS) [Citation134,Citation135], has been developed according to the current conceptualization of negative symptoms. This scale includes an evaluation of the two aspects of pleasure (consummatory and anticipatory) and is regarded as a useful instrument to integrate the clinician-based assessment of negative symptoms [Citation135,Citation136]. SNS demonstrated good psychometric properties [Citation134], has been validated in several European countries [Citation135,Citation137] and was also used in a general adolescent population [Citation137].

A brief description of the above-mentioned rating scales is provided in .

Table 3. Available instruments to assess negative symptoms in schizophrenia.

The recognition and correct evaluation of negative symptoms is also important in first-episode subjects and in subjects at risk to develop psychosis. In both cases, first-generation scales are more frequently used than the second-generation ones, despite having the same limitations described above for chronic patients. Unfortunately, also second-generation rating scales designed for adult subjects might not be sensitive enough to capture subtle negative symptoms of children, adolescents and young adults and have not been validated in first episode studies [Citation15].

Similar limitations apply to studies including the assessment of negative symptoms in HR subjects. Actually, adapted versions of the BNSS and CAINS have been developed and tested in small samples [Citation93,Citation94,Citation138,Citation139] and the Prodromal Inventory of Negative symptoms (PINS) [Citation140] has been recently developed specifically for use in the HR population. Although they currently represent the best available measures of negative symptoms in this population, as they are adapted, such as BNSS and CAINS or are developed specifically for HR subjects, such as PINS, further studies are needed to confirm their sensitivity to detect negative symptoms in HR subjects [Citation1,Citation48].

5. Main pathophysiological hypotheses of negative symptom domains

Understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of negative symptoms could foster the development of new care strategies [Citation141–144].

One of the most up-to-date pathophysiological hypotheses underlying negative symptoms indicates a relationship between the Experiential domain and an impairment in several aspects of motivation [Citation17,Citation59,Citation70,Citation145–152], which might be underpinned by abnormalities in two brain circuits, the ‘Motivational value circuit’ and the ‘Motivational salience circuit’ [Citation17,Citation71,Citation153,Citation154]. The former one, which is activated only in positive situations, is related to the evaluation of stimuli and action, anticipated pleasure and instrumental learning [Citation17,Citation155]; the latter one, which is activated in both negative and positive situations, refers to the more general aspects of motivation, cognitive activation, and the ability to orient to salient stimuli [Citation17,Citation156–159]. Different treatment approaches should target the impairment of these two circuits. For instance, if there is a dysfunction of the motivational value circuit, pharmacological and/or psychosocial interventions should aim to increase the salience of stimuli and stimulate cognition; in case of a dysfunction of the motivational salience circuit an enhancement of instrumental learning and of reward processes might be necessary.

The Expressive deficit domain has been less investigated than the Experiential domain. Several studies suggest that it is linked to cognitive impairment and might be subtended by a diffuse neurodevelopmental alteration in brain connectivity leading to deficits in neurocognition, social cognition, and neurological soft signs, often observed in subjects with schizophrenia, especially in those with a high genetic risk for schizophrenia [Citation3,Citation71,Citation109,Citation114,Citation116,Citation145–148,Citation160–163]. Despite the interest of the hypothesis, relevant findings are inconsistent and need further investigation.

In a near future, new research methods, like multiomics (genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, metabolomics, connectomics, and gut microbiomics), and inducible pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs), might lead to progress in the identification of pathophysiological mechanisms of persistent negative symptoms [Citation164–169]. To date, these techniques are at the beginning, and much effort is needed for their implementation in research and clinical practice.

For instance, a recent study by Kauppi et al. [Citation169,Citation170], using protein interactome to map polygenic link between antipsychotic drug targets and schizophrenia risk genes, found that some risk genes (e.g. CHRN, PCDH, and HCN families) involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia might represent reliable targets to treat some aspects of schizophrenia that do not respond to current available treatments, like negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunctions [Citation170].

Furthermore, iPSCs from human donors, by retaining the genetic background of risk genetic variants, represent novel basic research tools developed with the aim to model psychiatric disorders and to discover novel pharmacologic treatments [Citation164]. One iPSC study [Citation171], for instance, found in iPSC-derived cortical interneurons of subjects with schizophrenia a metabolic abnormality, i.e. a mitochondrial bioenergetic deficit, which could be reverted with Alpha Lipoic Acid/Acetyl-L-Carnitine [Citation164]. Considering the role that dopamine dysfunctions play in the pathophysiology of motivational deficits in subjects with schizophrenia [Citation17], it would be interesting to investigate metabolic dysfunctions also in iPSC-derived dopamine neurons [Citation164]. This approach might offer the perspective of the development of new therapeutic drugs targeting, for instance, the metabolism of iPSCs-derived neurons. It is hoped that in the next few years this method will be able to provide a meaningful characterization of schizophrenia subtypes, e.g. subjects with primary and persistent negative symptoms and favor the development of specific treatments.

6. Psychopharmacological and psychosocial interventions for negative symptoms

Limited treatment options are available for the care of negative symptoms, especially when they are primary and enduring over the time. The lack of effective treatments for negative symptoms might derive from a great amount of literature that did not distinguish between primary and secondary negative symptoms and/or used a global/total score for these symptoms and/or used outdated tools for assessing negative symptoms [Citation1].

Antipsychotic drugs generally ameliorate negative symptoms secondary to positive symptoms during acute phases of schizophrenia. In subjects treated with an antipsychotic medication and presenting negative symptoms considered secondary to positive symptoms, a change of antipsychotic or an increase in the drug dose should be considered. In the presence of negative symptoms regarded as secondary to treatment-resistant positive symptoms, a pharmacological switch to clozapine should be taken into account [Citation122,Citation172]. When the negative symptomatology is considered as an adverse effect of the pharmacotherapy, a dose range optimization or a switch to another antipsychotic with lower risk of extrapyramidal and/or sedative side effects could be helpful. Moreover, in subjects with negative symptoms secondary to depression a clinical improvement could be reached with a switch to an antipsychotic with antidepressant properties (e.g. quetiapine, amisulpride, cariprazine, aripiprazole, clozapine, and olanzapine) [Citation173,Citation174] or with an add-on antidepressant treatment or with the integration of cognitive behavior therapy [Citation173,Citation174] ().

While secondary negative symptoms generally improve with the above-mentioned strategies, primary and persistent negative symptoms do not respond satisfactorily to available antipsychotics. A careful comparison of the efficacy of various treatments for the care of negative symptoms in schizophrenia is challenging since most studies did not distinguish between primary and secondary negative symptoms and/or used a global/total score for these symptoms and/or used outdated tools for assessing negative symptoms [Citation15].

A meta-analysis conducted by Fusar-Poli et al. [Citation175], to investigate the effects of antipsychotics (first-generation antipsychotics-FGAs, and second-generation antipsychotics-SGAs) as compared to placebo in improving negative symptoms, found a small improvement in these symptoms with SGAs, but not with FGAs. Within SGAs, Leucht and colleagues [Citation173] reported that amisulpride, clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone were more efficacious than FGA in improving negative symptoms. However, in these metanalyses, included clinical data were very heterogeneous, and no specific information on the characteristics of negative symptoms was provided.

Another meta-analysis has specifically analyzed the results of available trials in the population of patients with prominent or predominant negative symptoms [Citation176]. However, most studies included in this metanalysis, especially those focused on prominent negative symptoms, did not take into account the effects of possible confounding factors, such as depression, positive symptoms or extrapyramidal side effects. In addition, most included studies were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. According to this metanalysis, olanzapine and quetiapine significantly outperformed risperidone in ameliorating prominent negative symptoms; these data, however, are based on single studies [Citation177,Citation178] and need replications.

As regards to predominant negative symptoms, the metanalysis of Krause and colleagues [Citation176] found some promising results for amisulpride and cariprazine. According to this meta-analysis, only amisulpride was more efficacious than placebo in ameliorating predominant negative symptoms, but also depressive symptoms [Citation176]. Amisulpride is both a selective dopamine D2/D3 receptor antagonist (which could explain its efficacy vs predominant negative symptoms) and a 5-HT7 antagonist, a profile that accounts for antidepressant effects [Citation179]. As depressive and negative symptoms overlap, without a proper evaluation and differentiation of negative symptomatology, it is difficult to say whether amisulpride reduces primary or only negative symptoms secondary to depression [Citation15].

Cariprazine, approved by the FDA in September 2015 for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, is a dopamine D3-D2 receptor partial agonist and serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist [Citation180]. This drug has showed a beneficial effect in the treatment of patients with predominant and enduring negative symptoms in schizophrenia [Citation176,Citation181–186]. In particular, in a 26-week, multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind manufacturer-sponsored study, the efficacy of cariprazine versus risperidone was investigated in adult patients with schizophrenia and with predominant and enduring negative symptoms [Citation184]. Sources of secondary negative symptoms, such as positive symptoms, depression, and extrapyramidal side effects were also controlled. This manufacturer-sponsored study found that cariprazine outperformed risperidone in the treatment of predominant and enduring negative symptoms as measured by a negative factor of the PANSS [Citation184]. Deconstructing the PANSS factor into individual items, the effect of cariprazine was observed on the PANSS items N1-N5 (blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, poor rapport, passive/apathetic social withdrawal, difficulty in abstract thinking) but not on N6 (lack of spontaneity/flow of conversation) or N7 (stereotyped thinking) [Citation187].

Furthermore, some studies investigated the potential role of different molecules, such as pro-dopaminergic agents, anti-inflammatory drugs, or antibiotics as add-on treatments to antipsychotics for negative symptoms [Citation15]. However, findings are not consistent, and no conclusion can be drawn yet about their efficacy [Citation15].

Available evidence on pharmacological treatments for negative symptoms is scarce and in need for further research. Given that negative symptoms represent an unmet therapeutic need, there is hope that new solutions will be provided by the search for new drugs and the development of innovative treatments, such as trace amine receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonist (SEP-856) [Citation188] and roluperidone (MIN-01) [Citation189]. SEP-856 is an agonist of the trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and 5-HT1a receptor, which has shown potential activity in targeting positive and negative symptoms in preclinical studies [Citation188,Citation190]. MIN-101 is a new sigma-2 receptor antagonist [Citation191]. In a 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial conducted in subjects with schizophrenia, roluperidone has shown superiority over placebo in improving negative symptoms [Citation189,Citation192]. Results from the roluperidone phase 3 trial do not lead to solid conclusions. Indeed, in 513 patients with moderate-to-severe negative symptoms, using the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis data set, there was no statistically significant difference between two doses of roluperidone (32 and 64 mg), as compared to placebo, in ameliorating negative symptoms. However, using the modified ITT data set (excluding from the dataset implausible behavioral and physiological data), the 64 mg dose of roluperidone showed superiority over placebo (p ≤ .044) in improving negative symptoms [Citation191]. Despite the potential of this new pharmacological treatment in targeting negative symptoms, these data need replication and further investigation.

Other biological interventions, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation, have gained attention as a promising approach for the treatment of negative symptoms in association with SGA, although there is no sufficient evidence of their positive effects on negative symptoms [Citation193–196].

Also, some psychosocial interventions have shown efficacy in improving negative symptoms [Citation15]. In particular, different systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrated the efficacy of social skills training, as compared to active controls and treatment as usual, in ameliorating negative symptoms of subjects with schizophrenia [Citation15,Citation197–199]. Furthermore, also cognitive remediation might improve negative symptoms in subjects with schizophrenia, in particular, in those who also show impairment in neurocognition and social cognition [Citation15,Citation199–203]. Other interventions include body-oriented and mind–body psychotherapies [Citation204,Citation205], art therapy and music therapy [Citation206,Citation207], physical exercise [Citation208–210], as well as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT); however, to date, available data are not sufficient to demonstrate their efficacy in targeting negative symptoms.

Given the key role of negative symptoms in determining a poor functioning in subjects with schizophrenia, every effort should be made to foster the advancement in the knowledge of negative symptoms, and in the development of innovative treatments.

7. Expert opinion

There are still many gaps in the management of negative symptoms in subjects with schizophrenia. These symptoms are still poorly recognized by physicians, family members/caregivers and by patients themselves, probably because they cause much less concern than other clinical features, such as positive symptoms, aggressiveness or psychomotor agitation.

Despite the effort made in the last decades to advance the conceptualization of negative symptoms and develop state-of-the-art assessment instruments, their evaluation needs to be improved both in research and clinical settings. Indeed, after more than 15 years from the NIMH consensus initiative on negative symptoms, different investigations and clinical trials use first-generation rating scales for the evaluation of negative symptoms, thus including also aspects that are not currently conceptualized as negative symptoms (e.g. for the PANSS, active social avoidance and motor retardation; for the SANS, the attention subscale and poverty of content of speech). As a matter of fact, the improvement in the conceptualization and evaluation of negative symptoms has not yet been taken into account by drug regulatory authorities and consequently by designers of randomized controlled trials, hindering research progress related to the use of second-generation rating scales [Citation17].

The inclusion of aspects not conceptualized as negative symptoms should be avoided, and researchers and clinicians should be encouraged to enhance the dissemination of second-generation rating scales which have been developed according to the consensus conference and provide a better assessment of negative symptoms. To this aim, the training of psychiatrists should focus more on the careful and up-to-date recognition and evaluation of negative symptoms, implementing the use of more appropriate assessment tools in daily clinical practice and including the evaluation of internal experience and the promotion of self-reporting of negative symptoms. For this purpose, state-of-the-art assessment instruments are available and have been translated and validated in several languages showing a good agreement between clinicians across many countries [Citation1,Citation15,Citation121,Citation123–133]. In addition, the use of these instruments would be important also to clarify whether the greater severity of negative symptoms, widely reported in male patients as compared to females, involves all negative symptoms or only one of the two negative symptom domains (the Experiential or the Expressive Deficit domain). This would have prognostic and therapeutic implications, since it has been found that the two negative symptom domains are subtended by different pathophysiological mechanisms and show different associations with patient’s functioning [Citation17,Citation19]. In particular, as male subjects have a greater severity of negative symptoms than females both in the UHR and in the first-episode groups, it can be hypothesized that they present a higher frequency of neurodevelopmental alterations and primary negative symptoms of the Expressive deficit type, which might be related to more severe neurodevelopmental disturbances, as indicated by their association with low general cognitive abilities and soft neurological signs [Citation17]. The validation of this hypothesis would have diagnostic and therapeutic implications for the early recognition of male subjects with poor outcome.

Large multicenter longitudinal studies are highly needed to evaluate the natural course of negative symptoms and detect the impact of possible confounding factors, such as positive symptoms, depression, extrapyramidal side effects and hypostimulation, at different stages of the disorder, to improve our ability to identify the different sources of secondary negative symptoms, provide effective interventions, and target primary and persistent negative symptoms with innovative integrated treatment strategies.

Moreover, the differentiation between primary and secondary negative symptoms should be carefully considered when conducting research on these symptoms in transdiagnostic samples [Citation211]. Indeed, although negative symptoms are typically described in subjects with schizophrenia, they might be observed in other mental disorders (e.g. schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder), in neurological disorders (e.g. multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease) and also in the general population. However, it is not clear whether negative symptoms that occur in disorders other than schizophrenia might be primary to the disease process or whether they are always secondary to other factors (e.g. cognitive impairment) [Citation211]. It still remains to be clarified whether the negative symptom constructs, their correlates, and neurobiological underpinnings are homogeneous across diagnoses [Citation17]. A detailed characterization of the occurrence of the different negative symptoms, their course and association with other clinical features and neurodevelopmental indices, might represent a step towards a transdiagnostic approach to mental illnesses or might contribute to model the boundaries between categories that present important overlap in terms of biological underpinnings, etiopathological mechanisms, clinical presentations and outcomes [Citation4,Citation13].

It is hoped that innovative methods, like multiomics, IPSCs, and computational neuroscience, in the near future might contribute to clarify pathophysiological mechanisms of negative symptoms and develop new treatments [Citation164,Citation168,Citation212].

In conclusion, every effort should be made to (i) provide a clinical assessment of negative symptoms using state-of-the-art assessment tools; (ii) promote large-scale longitudinal studies; (iii) take into account all available treatment whose efficacy is supported by research evidence; (iv) support translational research in order to improve knowledge on the pathophysiology of negative symptoms and foster the development of innovative treatments.

Article highlights

Negative symptoms are associated with poor functional outcome and represent a substantial burden for people affected from schizophrenia, their families, and health-care systems.

Negative symptoms are currently conceptualized as five individual domains: blunted affect, alogia, avolition, asociality, and anhedonia.

Second-generation rating scales are available for the assessment of negative symptoms, in line with current conceptualizations.

Despite the progress made in the last decades in the conceptualization of negative symptoms and development of second-generation rating scales, these symptoms are still poorly recognized, and not always assessed in line with their current conceptualization.

The development of specific assessment instruments for negative symptoms in subjects at risk to develop psychosis and in those with a first episode of psychosis should represent a priority within early intervention settings.

Clear procedures for the differentiation between primary and secondary negative symptoms should be developed, in order to plan appropriate interventions.

Limited treatment options are available for negative symptoms and, therefore, they remain an unmet therapeutic need for the care of people with schizophrenia.

Further research studies are needed in order to improve the knowledge on the negative symptom pathophysiology to foster the development of innovative treatment strategies.

Declaration of interests

S Galderisi has been consultant and/or advisor to and/or received honoraria or grants from Millennium Pharmaceutical, Innova Pharma-Recordati Group, Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Gedeon Richter-Recordati, Lundbeck and Angelini. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Galderisi S, Mucci A, Dollfus S, et al. EPA guidance on assessment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(1):e23.

- Correll CU, Schooler NR. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a review and clinical guide for recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:519–534.

- Marder SR, Galderisi S. The current conceptualization of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):14–24.

- Maj M, van Os J, De Hert M, et al. The clinical characterization of the patient with primary psychosis aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):4–33.

- Novick D, Haro JM, Suarez D, et al. Recovery in the outpatient setting: 36-month results from the Schizophrenia Outpatients Health Outcomes (SOHO) study. Schizophr Res. 2009;108(1–3):223–230.

- Harvey PD, Strassnig M. Predicting the severity of everyday functional disability in people with schizophrenia: cognitive deficits, functional capacity, symptoms, and health status. World Psychiatry. 2012;11(2):73–79.

- Galderisi S, Rossi A, Rocca P, et al. The influence of illness-related variables, personal resources and context-related factors on real-life functioning of people with schizophrenia. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):275–287.

- Galderisi S, Rossi A, Rocca P, et al. Pathways to functional outcome in subjects with schizophrenia living in the community and their unaffected first-degree relatives. Schizophr Res. 2016;175(1–3):154–160.

- Galderisi S, Rucci P, Kirkpatrick B, et al. Interplay among psychopathologic variables, personal resources, context-related factors, and real-life functioning in individuals with Schizophrenia: a network analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):396–404.

- Galderisi S, Rucci P, Mucci A, et al. The interplay among psychopathology, personal resources, context-related factors and real-life functioning in schizophrenia: stability in relationships after 4 years and differences in network structure between recovered and non-recovered patients. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):81–91.

- Mucci A, Galderisi S, Gibertoni D, et al. Factors associated with real-life functioning in persons with schizophrenia in a 4-Year Follow-up Study of the Italian network for research on psychoses. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):550–559.

- Giuliani L, Giordano GM, Bucci P, et al. Improving knowledge on pathways to functional outcome in schizophrenia: main results from the Italian network for research on psychoses. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:791117.

- Galderisi S, Giordano GM. We are not ready to abandon the current schizophrenia construct, but should be prepared to do so. Schizophr Res. 2022;242:30–34.

- Bucci P, Galderisi S, Mucci A, et al. Premorbid academic and social functioning in patients with schizophrenia and its associations with negative symptoms and cognition. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(3):253–266.

- Galderisi S, Kaiser S, Bitter I, et al. EPA guidance on treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(1):e21.

- Heckers S, Kendler KS. The evolution of Kraepelin’s nosological principles. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):381–388.

- Galderisi S, Mucci A, Buchanan RW, et al. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new developments and unanswered research questions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(8):664–677.

- Ochoa S, Usall J, Cobo J, et al. Gender differences in schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive literature review. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2012;2012:916198.

- Giordano GM, Bucci P, Mucci A, et al. Gender differences in clinical and psychosocial features among persons with schizophrenia: a mini review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:789179.

- Muralidharan A, Finch A, Bowie CR, et al. Older versus middle-aged adults with schizophrenia: executive functioning and community outcomes. Schizophr Res. 2020;216:547–549.

- Muralidharan A, Harvey PD, Bowie CR. Associations of age and gender with negative symptom factors and functioning among middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(12):1215–1219.

- Galderisi S, Mucci A, Bitter I, et al. Persistent negative symptoms in first episode patients with schizophrenia: results from the European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(3):196–204.

- Austin SF, Mors O, Budtz-Jørgensen E, et al. Long-term trajectories of positive and negative symptoms in first episode psychosis: a 10 year follow-up study in the OPUS cohort. Schizophr Res. 2015;168(1–2):84–91.

- Hovington CL, Bodnar M, Joober R, et al. Identifying persistent negative symptoms in first episode psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):224.

- Bucci P, Mucci A, van Rossum IW, et al. Persistent negative symptoms in recent-onset psychosis: relationship to treatment response and psychosocial functioning. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;34:76–86.

- Quattrone D, Di Forti M, Gayer-Anderson C, et al. Transdiagnostic dimensions of psychopathology at first episode psychosis: findings from the multinational EU-GEI study. Psychol Med. 2019;49(8):1378–1391.

- Thorup A, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, et al. Gender differences in young adults with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders at baseline in the Danish OPUS study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(5):396–405.

- Barajas A, Ochoa S, Obiols JE, et al. Gender differences in individuals at high-risk of psychosis: a comprehensive literature review. ScientificWorldJournal. 2015;430735.

- Challis S, Nielssen O, Harris A, et al. Systematic meta-analysis of the risk factors for deliberate self-harm before and after treatment for first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(6):442–454.

- Morgan VA, Castle DJ, Jablensky AV. Do women express and experience psychosis differently from men? Epidemiological evidence from the Australian national study of low prevalence (psychotic) disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42(1):74–82.

- Leclerc E, Noto C, Bressan RA, et al. Determinants of adherence to treatment in first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive review. Braz J Psychiatry. 2015;37(2):168–176.

- Santesteban-Echarri O, Paino M, Rice S, et al. Predictors of functional recovery in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;58:59–75.

- Watson P, Zhang JP, Rizvi A, et al. A meta-analysis of factors associated with quality of life in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2018;202:26–36.

- Best MW, Grossman M, Oyewumi LK, et al. Examination of the positive and negative syndrome scale factor structure and longitudinal relationships with functioning in early psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(2):165–170.

- Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, et al. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):495–506.

- Hafner H, Maurer K, Ruhrmann S, et al. Early detection and secondary prevention of psychosis: facts and visions. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254(2):117–128.

- Iyer SN, Boekestyn L, Cassidy CM, et al. Signs and symptoms in the pre-psychotic phase: description and implications for diagnostic trajectories. Psychol Med. 2008;38(8):1147–1156.

- Lencz T. Nonspecific and attenuated negative symptoms in patients at clinical high-risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(1):37–48.

- Piskulic D, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, et al. Negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196(2–3):220–224.

- Velthorst E, Nieman DH, Becker HE, et al. Baseline differences in clinical symptomatology between ultra high risk subjects with and without a transition to psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2009;109(1–3):60–65.

- Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2–3):131–142.

- Carrion RE, Demmin D, Auther AM, et al. Duration of attenuated positive and negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk: associations with risk of conversion to psychosis and functional outcome. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;81:95–101.

- Demjaha A, Valmaggia L, Stahl D, et al. Disorganization/cognitive and negative symptom dimensions in the at-risk mental state predict subsequent transition to psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(2):351–359.

- Mason O, Startup M, Halpin S, et al. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with ‘at-risk mental states’. Schizophr Res. 2004;71(2–3):227–237.

- Zhang T, Cui H, Wei Y, et al. Neurocognitive assessments are more important among adolescents than adults for predicting psychosis in clinical high risk. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2022;7(1):56–65.

- Devoe DJ, Peterson A, Addington J. Negative symptom interventions in youth at risk of psychosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(4):807–823.

- Lee SJ, Kim KR, Lee SY, et al. Impaired social and role function in ultra-high risk for psychosis and first-episode schizophrenia: its relations with negative symptoms. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14(5):539–545.

- Strauss GP, Pelletier-Baldelli A, Visser KF, et al. A review of negative symptom assessment strategies in youth at clinical high-risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:104–112.

- Ucok A, Direk N, Kaya H, et al. Relationship of negative symptom severity with cognitive symptoms and functioning in subjects at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2021;15(4):966–974.

- Glenthoj LB, Jepsen JR, Hjorthoj C, et al. Negative symptoms mediate the relationship between neurocognition and function in individuals at ultrahigh risk for psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(3):250–258.

- Schlosser DA, Campellone TR, Biagianti B, et al. Modeling the role of negative symptoms in determining social functioning in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2015;169(1–3):204–208.

- Giordano GM, Palumbo D, Pontillo M, et al. Negative symptom domains in children and adolescents at ultra-high risk for psychosis: association with real-life functioning. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open. 2022;3(1).

- Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT Jr., et al. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):214–219.

- Heerey EA, Gold JM. Patients with schizophrenia demonstrate dissociation between affective experience and motivated behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116(2):268–278.

- Waltz JA, Frank MJ, Robinson BM, et al. Selective reinforcement learning deficits in schizophrenia support predictions from computational models of striatal-cortical dysfunction. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(7):756–764.

- Kring AM, Moran EK. Emotional response deficits in schizophrenia: insights from affective science. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(5):819–834.

- Barch DM, Dowd EC. Goal representations and motivational drive in schizophrenia: the role of prefrontal-striatal interactions. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(5):919–934.

- Cohen AS, Minor KS. Emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia revisited: meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):143–150.

- Foussias G, Remington G. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: avolition and Occam’s razor. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):359–369.

- Dowd EC, Barch DM. Pavlovian reward prediction and receipt in schizophrenia: relationship to anhedonia. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35622.

- Simpson EH, Waltz JA, Kellendonk C, et al. Schizophrenia in translation: dissecting motivation in schizophrenia and rodents. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(6):1111–1117.

- Strauss GP. The emotion paradox of anhedonia in schizophrenia: or is it? Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):247–250.

- Morris RW, Quail S, Griffiths KR, et al. Corticostriatal control of goal-directed action is impaired in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(2):187–195.

- Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, et al. Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. Neuroreport. 2001;12(17):3683–3687.

- Horan WP, Kring AM, Blanchard JJ. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: a review of assessment strategies. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):259–273.

- Gard DE, Kring AM, Gard MG, et al. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophr Res. 2007;93(1–3):253–260.

- Blanchard JJ, Kring AM, Horan WP, et al. Toward the next generation of negative symptom assessments: the collaboration to advance negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(2):291–299.

- Gold JM, Waltz JA, Matveeva TM, et al. Negative symptoms and the failure to represent the expected reward value of actions: behavioral and computational modeling evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):129–138.

- Horan WP, Kring AM, Gur RE, et al. Development and psychometric validation of the clinical assessment interview for negative symptoms (CAINS). Schizophr Res. 2011;132(2–3):140–145.

- Strauss GP, Horan WP, Kirkpatrick B, et al. Deconstructing negative symptoms of schizophrenia: avolition-apathy and diminished expression clusters predict clinical presentation and functional outcome. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(6):783–790.

- Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, et al. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment. Schizophr Res. 2017;186:39–45.

- Gaebel W, Falkai P, Hasan A. The revised German evidence- and consensus-based schizophrenia guideline. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):117–119.

- Peralta V, Gil-Berrozpe GJ, Sanchez-Torres A, et al. Clinical relevance of general and specific dimensions in bifactor models of psychotic disorders. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):306–307.

- Strauss GP, Ahmed AO, Young JW, et al. Reconsidering the latent structure of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a review of evidence supporting the 5 consensus domains. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(4):725–729.

- Strauss GP, Esfahlani FZ, Galderisi S, et al. Network analysis reveals the latent structure of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(5):1033–1041.

- Strauss GP, Nunez A, Ahmed AO, et al. The latent structure of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(12):1271–1279.

- Ahmed AO, Kirkpatrick B, Galderisi S, et al. Cross-cultural validation of the 5-factor structure of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(2):305–314.

- Mucci A, Vignapiano A, Bitter I, et al. A large European, multicenter, multinational validation study of the brief negative symptom scale. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(8):947–959.

- Dollfus S, Mucci A, Giordano GM, et al. European validation of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS): a large multinational and multicenter study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:826465.

- Beck AT, Himelstein R, Bredemeier K, et al. What accounts for poor functioning in people with schizophrenia: a re-evaluation of the contributions of neurocognitive v. attitudinal and motivational factors. Psychol Med. 2018;48(16):2776–2785.

- Foussias G, Agid O, Fervaha G, et al. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: clinical features, relevance to real world functioning and specificity versus other CNS disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(5):693–709.

- Chang WC, Hui CL, Chan SK, et al. Impact of avolition and cognitive impairment on functional outcome in first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorder: a prospective one-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(2–3):318–321.

- Ahmed AO, Murphy CF, Latoussakis V, et al. An examination of neurocognition and symptoms as predictors of post-hospital community tenure in treatment resistant schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2016;236:47–52.

- Rapado-Castro M, Soutullo C, Fraguas D, et al. Predominance of symptoms over time in early-onset psychosis: a principal component factor analysis of the positive and negative syndrome scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(3):327–337.

- Langeveld J, Andreassen OA, Auestad B, et al. Is there an optimal factor structure of the positive and negative syndrome scale in patients with first-episode psychosis? Scand J Psychol. 2013;54(2):160–165.

- Tibber MS, Kirkbride JB, Joyce EM, et al. The component structure of the scales for the assessment of positive and negative symptoms in first-episode psychosis and its dependence on variations in analytic methods. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:869–879.

- Lyne J, Renwick L, Grant T, et al. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms structure in first episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):1191–1197.

- Pelizza L, Landi G, Pellegrini C, et al. Negative symptom configuration in first episode Schizophrenia: findings from the “Parma Early Psychosis” program. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020;74(4):251–258.

- Pelizza L, Azzali S, Paterlini F, et al. Negative symptom dimensions in first episode psychosis: is there a difference between schizophrenia and non-schizophrenia spectrum disorders? Early Interv Psychiatry. 2021;15(6):1513–1521.

- Pelizza L, Maestri D, Leuci E, et al. Negative symptom configuration within and outside schizophrenia spectrum disorders: results from the “parma early psychosis” program. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294:113519.

- Lam M, Abdul Rashid NA, Lee SA, et al. Baseline social amotivation predicts 1-year functioning in UHR subjects: a validation and prospective investigation. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(12):2187–2196.

- Azis M, Strauss GP, Walker E, et al. Factor analysis of negative symptom items in the structured interview for prodromal syndromes. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(5):1042–1050.

- Chang WC, Lee HC, Chan SI, et al. Negative symptom dimensions differentially impact on functioning in individuals at-risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2018;202:310–315.

- Chang WC, Strauss GP, Ahmed AO, et al. The latent structure of negative symptoms in individuals with attenuated psychosis syndrome and early psychosis: support for the 5 consensus domains. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47(2):386–394.

- Hawkins KA, McGlashan TH, Quinlan D, et al. Factorial structure of the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2–3):339–347.

- Tso IF, Taylor SF, Grove TB, et al. Factor analysis of the scale of prodromal symptoms: data from the early detection and intervention for the prevention of psychosis program. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2017;11(1):14–22.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276.

- Andreasen NC. The scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry Suppl.1989; 155(7):49–58.

- Andreasen NC. The scale for the assessment of positive symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City Iowa: The University of Iowa; 1984.

- Chang WC, Kwong VW, Hui CL, et al. Relationship of amotivation to neurocognition, self-efficacy and functioning in first-episode psychosis: a structural equation modeling approach. Psychol Med. 2017;47(4):755–765.

- Chang WC, Kwong VW, Chan GH, et al. Prediction of motivational impairment: 12-month follow-up of the randomized-controlled trial on extended early intervention for first-episode psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;41(1):37–41.

- Chang WC, Wong CSM, Pcf O, et al. Inter-relationships among psychopathology, premorbid adjustment, cognition and psychosocial functioning in first-episode psychosis: a network analysis approach. Psychol Med. 2020;50(12):2019–2027.

- Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11–12):964–971.

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703–715.

- Kirkpatrick B, Strauss GP, Nguyen L, et al. The brief negative symptom scale: psychometric properties. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(2):300–305.

- Strauss GP, Nuñez A, Ahmed AO, et al. The latent structure of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(12):1271–1279.

- Kirkpatrick B, A M, Galderisi S. Primary, enduring negative symptoms: an update on research. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(4):730–736.

- Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, Ross DE, et al. A separate disease within the syndrome of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(2):165–171.

- Mucci A, Merlotti E, Üçok A, et al. Primary and persistent negative symptoms: concepts, assessments and neurobiological bases. Schizophr Res. 2017;186:19–28.

- Carpenter WT Jr., Heinrichs DW, Wagman AM. Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: the concept. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(5):578–583.

- Galderisi S, Maj M, Mucci A, et al. Historical, psychopathological, neurological, and neuropsychological aspects of deficit schizophrenia: a multicenter study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):983–990.

- Buchanan RW. Persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(4):1013–1022.

- Galderisi S, Maj M. Deficit schizophrenia: an overview of clinical, biological and treatment aspects. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(8):493–500.

- Kirkpatrick B. Progress in the study of negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(Suppl 2):S101–6.

- Kirkpatrick B, Miller B, García-Rizo C, et al. Schizophrenia: a systemic disorder. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2014;8(2):73–79.

- Galderisi S, Merlotti E, Mucci A. Neurobiological background of negative symptoms. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(7):543–558.

- Bucci P, Galderisi S. Categorizing and assessing negative symptoms. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(3):201–208.

- Kirkpatrick B, Galderisi S. Deficit schizophrenia: an update. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):143–147.

- Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, McKenney PD, et al. The Schedule for the Deficit syndrome: an instrument for research in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1989;30(2):119–123.

- Kumari S, Malik M, Florival C, et al. An assessment of five (PANSS,SAPS,SANS,NSA-16, CGI-SCH) commonly used symptoms rating scales in schizophrenia and comparison to newer scales (CAINS, BNSS). Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy. 2017;8(3):324.

- Mucci A, Galderisi S, Merlotti E, et al. The brief negative symptom scale (BNSS): independent validation in a large sample of Italian patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(5):641–647.

- Kring AM, Gur RE, Blanchard JJ, et al. The clinical assessment interview for negative symptoms (CAINS): final development and validation. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):165–172.

- Ang MS, Rekhi G, Lee J. Validation of the brief negative symptom scale and its association with functioning. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:97–104.

- Nazlı I P, Ergül C, Ö A, et al. Validation of Turkish version of brief negative symptom scale. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(4):265–271.

- Gehr J, Glenthøj B, Ødegaard Nielsen M. Validation of the Danish version of the brief negative symptom scale. Nord J Psychiatry. 2019;73(7):425–432.

- Wójciak P, Górna K, Domowicz K, et al. Polish version of the brief negative symptom scale (BNSS). Psychiatr Pol. 2019;53(3):541–549.

- Bischof M, Obermann C, Hartmann MN, et al. The brief negative symptom scale: validation of the German translation and convergent validity with self-rated anhedonia and observer-rated apathy. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):415.

- Mané A, García-Rizo C, Garcia-Portilla MP, et al. Spanish adaptation and validation of the brief negative symptoms scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(7):1726–1729.

- Chan RC, Shi C, Lui SS, et al. Validation of the Chinese version of the clinical assessment interview for negative symptoms (CAINS): a preliminary report. Front Psychol. 2015;6:7.

- Xie DJ, Shi HS, Lui SSY, et al. Cross cultural validation and extension of the clinical assessment interview for negative symptoms (CAINS) in the Chinese context: evidence from a spectrum perspective. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(suppl_2):S547–s55.

- Jung SI, Woo J, Kim YT, et al. Validation of the Korean-version of the clinical assessment interview for negative symptoms of schizophrenia (CAINS). J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(7):1114–1120.

- Valiente-Gómez A, Mezquida G, Romaguera A, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the clinical assessment for negative symptoms (CAINS). Schizophr Res. 2015;166(1–3):104–109.

- Engel M, Fritzsche A, Lincoln TM. Validation of the German version of the clinical assessment interview for negative symptoms (CAINS). Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(1–2):659–663.

- Dollfus S, Mach C, Morello R. Self-evaluation of negative symptoms: a novel tool to assess negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(3):571–578.

- Dollfus S, Mucci A, Giordano GM, et al. European validation of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS): a large multinational and multicenter study. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2022; 13:826465. DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.826465.

- Tatsumi K, Kirkpatrick B, Strauss GP, et al. The brief negative symptom scale in translation: a review of psychometric properties and beyond. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;33:36–44.

- Rodríguez-Testal JF, Perona-Garcelán S, Dollfus S, et al. Spanish validation of the self-evaluation of negative symptoms scale SNS in an adolescent population. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):327.

- Strauss GP, Chapman HC. Preliminary psychometric properties of the brief negative symptom scale in youth at clinical high-risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2018;193:435–437.

- Gur RE, March M, Calkins ME, et al. Negative symptoms in youths with psychosis spectrum features: complementary scales in relation to neurocognitive performance and function. Schizophr Res. 2015;166(1–3):322–327.

- Pelletier-Baldelli A, Strauss GP, Visser KH, et al. Initial development and preliminary psychometric properties of the Prodromal Inventory of Negative Symptoms (PINS). Schizophr Res. 2017;189:43–49.

- Kotov R, Jonas KG, Carpenter WT, et al. Validity and utility of Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): i. Psychosis Superspectrum. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):151–172.

- Krueger RF, Hobbs KA, Conway CC, et al. Validity and utility of Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): II. Externalizing Superspectrum. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):171–193.

- Lahey BB, Moore TM, Kaczkurkin AN, et al. Hierarchical models of psychopathology: empirical support, implications, and remaining issues. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):57–63.

- First MB, Gaebel W, Maj M, et al. An organization- and category-level comparison of diagnostic requirements for mental disorders in ICD-11 and DSM-5. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):34–51.

- Amodio A, Quarantelli M, Mucci A, et al. Avolition-apathy and white matter connectivity in schizophrenia: reduced fractional anisotropy between amygdala and insular cortex. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2018;49(1):55–65.

- Giordano GM, Pezzella P, Quarantelli M, et al. Investigating the relationship between white matter connectivity and motivational circuits in subjects with deficit schizophrenia: a Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) study. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1):61.

- Giordano GM, Stanziano M, Papa M, et al. Functional connectivity of the ventral tegmental area and avolition in subjects with schizophrenia: a resting state functional MRI study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(5):589–602.

- Mucci A, Dima D, Soricelli A, et al. Is avolition in schizophrenia associated with a deficit of dorsal caudate activity? A functional magnetic resonance imaging study during reward anticipation and feedback. Psychol Med. 2015;45(8):1765–1778.

- McCutcheon RA, Krystal JH, Howes OD. Dopamine and glutamate in schizophrenia: biology, symptoms and treatment. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):15–33.

- Giordano GM, Perrottelli A, Mucci A, et al. Investigating the relationships of p3b with negative symptoms and neurocognition in subjects with chronic schizophrenia. Brain Sci. 2021;11(12):1632.

- Giordano GM, Koenig T, Mucci A, et al. Neurophysiological correlates of avolition-apathy in schizophrenia: a resting-EEG microstates study. NeuroImage Clin. 2018;20:627–636.

- Galderisi S, Caputo F, Giordano GM, et al. Aetiopathological mechanisms of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Die Psychiatrie. 2016;13(3):121–129.

- Menon V. Brain networks and cognitive impairment in psychiatric disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):309–310.

- Sanislow CA. RDoC at 10: changing the discourse for psychopathology. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):311–312.

- Harvey PD, Strassnig MT, Silberstein J. Prediction of disability in schizophrenia: symptoms, cognition, and self-assessment. J Exp Psychopathol. 2019;10(3):2043808719865693.

- Miller EM, Shankar MU, Knutson B, et al. Dissociating motivation from reward in human striatal activity. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014;26(5):1075–1084.

- Bissonette GB, Roesch MR. Development and function of the midbrain dopamine system: what we know and what we need to. Genes Brain Behav. 2016;15(1):62–73.

- Bissonette GB, Roesch MR. Neurophysiology of reward-guided behavior: correlates related to predictions, value, motivation, errors, attention, and action. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016;27:199–230.

- O’Doherty JP. Multiple systems for the motivational control of behavior and associated neural substrates in humans. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016;27:291–312.

- Galderisi S, Bucci P, Mucci A, et al. Categorical and dimensional approaches to negative symptoms of schizophrenia: focus on long-term stability and functional outcome. Schizophr Res. 2013;147(1):157–162.

- Kirschner M, Aleman A, Kaiser S. Secondary negative symptoms — a review of mechanisms, assessment and treatment. Schizophr Res. 2017;186:29–38.

- Giordano GM, Brando F, Perrottelli A, et al. Tracing links between early auditory information processing and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an ERP study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:790745.

- Moritz S, Silverstein SM, Dietrichkeit M, et al. Neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia are likely to be less severe and less related to the disorder than previously thought. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):254–255.

- Collo G, Mucci A, Giordano GM, et al. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia and dopaminergic transmission: translational models and perspectives opened by ipsc techniques. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:632.

- Noh H, Shao Z, Coyle JT, et al. Modeling schizophrenia pathogenesis using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863(9):2382–2387.

- Rastgar N. Schizophrenia; recent cognitive and treatment approaches using induced pluripotent stem cells. Int Clin Neurosci J. 2020;7(4):171–178.

- Giordano GM, Pezzella P, Perrottelli A, et al. Die “Präzisionspsychiatrie” muss Teil der “personalisierten Psychiatrie” werden. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2020;88(12):767–772.

- Sun Y, Zhou W, Chen L, et al. Omics in schizophrenia: current progress and future directions of antipsychotic treatments. Journal of Bio-X Research. 2019;2(4):145–152.

- Guan F, Ni T, Zhu W, et al. Integrative omics of schizophrenia: from genetic determinants to clinical classification and risk prediction. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):113–126.

- Kauppi K, Rosenthal SB, Lo MT, et al. Revisiting antipsychotic drug actions through gene networks associated with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(7):674–682.

- Ni P, Noh H, Park GH, et al. Correction: iPSC-derived homogeneous populations of developing schizophrenia cortical interneurons have compromised mitochondrial function. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(11):3103–3104.

- Lyne J, Renwick L, O’Donoghue B, et al. Negative symptom domain prevalence across diagnostic boundaries: the relevance of diagnostic shifts. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(3):347–354.

- Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):31–41.

- Leucht S, Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, et al. A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):152–163.

- Fusar-Poli P, Papanastasiou E, Stahl D, et al. Treatments of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of 168 randomized placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(4):892–899.

- Krause M, Zhu Y, Huhn M, et al. Antipsychotic drugs for patients with schizophrenia and predominant or prominent negative symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(7):625–639.

- Alvarez E, Ciudad A, Olivares JM, et al. A randomized, 1-year follow-up study of olanzapine and risperidone in the treatment of negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(3):238–249.

- Riedel M, Müller N, Strassnig M, et al. Quetiapine has equivalent efficacy and superior tolerability to risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255(6):432–437.