1. Introduction

Addressing a seemingly straightforward question such as the long-term prognosis of schizophrenia often prompts an automatic response, typically conveying a harsh outlook characterized by poor long-term outcomes. This perspective has persisted since Kraepelin’s classification of ‘dementia praecox’ over a century ago, defining it as a group of conditions marked by a gradual decline in cognitive functioning and overall functionality in various aspects of life [Citation1].

Throughout the years, the prevailing belief in the field has been that schizophrenia uniformly entails a bleak prognosis, featuring a deteriorating course of illness marked by neuroprogressive trajectory. This condition is commonly perceived as following a stereotypical pattern, where the majority of patients experience clinical deterioration, a hallmark of schizophrenia, leading to an end-stage characterized by persistent symptoms and profound functional disability.

The cumulative impact of these findings contributes to the notorious reputation of schizophrenia as one of the most devastating illnesses affecting mankind. It stands as a leading contributor to the global burden of disease, marked not only by its profound impact on individuals but also by the considerable economic costs associated with its management [Citation2].

2. Antipsychotic treatment response and dilemma

While there is a broad consensus acknowledging the poor prognosis and deteriorating course associated with schizophrenia, there is also widespread consensus regarding the notably robust response to antipsychotic treatment observed in individuals experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia. Typically, these patients exhibit a significant response to antipsychotic interventions, achieving full symptom remission within a relatively short period [Citation3]. When subjected to optimal treatment strategies, they often demonstrate a high likelihood of attaining clinical recovery [Citation4].

When considering these dual consensuses, a perplexing question emerges: how does a disorder characterized by progressive brain deterioration and a generally deteriorating course exhibit such a remarkably robust response to treatment, resulting in full recovery for individuals experiencing their initial episode? One possible explanation is that schizophrenia manifests as a neuroprogressive disorder, demonstrating a significant response to treatment in the early phases and as the illness progresses, a steady decline follows, indicating a progressive course.

Is schizophrenia truly a progressive brain disorder? Schizophrenia is a major cause of disability worldwide. Originally characterized by Kraepelin as leading to severe cognitive and behavioral decline, it is often viewed as a progressive brain disease. Neuroimaging studies support this by showing structural brain changes. However, the debate persists: Is schizophrenia a result of stable early deficits (neurodevelopmental) or a progressive decline (neuroprogressive) [Citation5,Citation6]?

Stable symptomatic and functional remission rates suggest it may not be inherently progressive. Clinical deterioration often results from non-adherence to medication, lifestyle factors, and environmental issues like poverty and lack of support, rather than the illness itself. While there are progressive brain changes in schizophrenia, they might not stem from the illness’s progression but from factors like substance use, stress, and medication effects. Some brain abnormalities occur early in development, preceding the illness [Citation7–9].

Comparing schizophrenia to Alzheimer’s, patients with schizophrenia do not experience the same level of decline in orientation and function. Cognitive impairment is significant in schizophrenia but appears early and does not necessarily worsen over time [Citation7]. The complexity of schizophrenia likely involves a combination of developmental and progressive processes, with considerable variation among patients. Despite evidence of brain changes and cognitive impairment, most patients do not exhibit a progressive deterioration inherently linked to the disease. While schizophrenia shows elements of both neurodevelopmental and neuroprogressive processes, it is not predominantly a progressive illness, and various factors contribute to its manifestations [Citation6].

Another possible explanation for this dilemma is the occurrence of relapses.

3. Impact of relapses

If schizophrenia is, indeed, a condition that responds well to treatment when managed effectively and consistently from the beginning, and it does not inherently follow a deteriorating course, then it is the episodes of relapse that could contribute to its perceived progressive decline. Experiencing a relapse involves numerous adverse consequences, involving both psychosocial and biological aspects.

On the psychosocial front, each relapse entails significant costs, including elevated care expenses, an increased burden on families and caregivers, loss of prior accomplishments, making it challenging to reclaim those achievements. The stigma attached to relapses contributes to a loss of self-esteem and fosters social stigma leading to discrimination. The cumulative effect of each additional relapse exacerbates these consequences exponentially [Citation10].

From a biological perspective, relapses can diminish the efficacy of antipsychotic treatment. Naturalistic studies indicate that patients may demonstrate reduced responsiveness to antipsychotic compounds that produced a robust response prior to relapse. Furthermore, a subset of individuals may cease responding altogether, evolving into cases of treatment-resistant schizophrenia [Citation11]. While the biological reason to this phenomenon is not clear, it is important to note that evidence from brain imaging studies underscores the negative impact of extended periods of relapse on the integrity of brain structures [Citation12].

Relapse is a common occurrence among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. The overwhelming majority, if not all, are likely to experience relapse. It is so prevalent that clinicians consider it as an inherent aspect of the syndrome.

Contrary to this perception, relapse is not an inevitable component of schizophrenia. While a significant number of patients may experience relapse, those who adhere with antipsychotic treatment can remain in remission for extended periods. Numerous factors may contribute to the occurrence of relapse, including exposure to stress and substance use. However, the primary and most influential factor explaining relapse in the majority of cases is non-adherence with continuous antipsychotic treatment [Citation13].

The close association between non-adherence and relapse has led clinicians to mistakenly perceive relapse as an inherent aspect of the illness. From the onset of the illness, many patients display non-adherence, with a substantial proportion subsequently experiencing relapse. Non-adherence to treatment is widespread among patients with schizophrenia, mirroring the high prevalence of relapse in this population. Evidence suggests that only a small minority of individuals with schizophrenia fully adhere to medications, rendering them less susceptible to relapse. In contrast, patients who are non-adherent face a significantly elevated risk of relapse, emphasizing the crucial role of adherence in preventing relapse among individuals with schizophrenia [Citation14]. Taken together, it appears that schizophrenia is a highly treatable illness when managed effectively and continuously from the outset but can assume a progressively deteriorating course in the presence of relapse.

4. Algorithm-based treatment approach

A highly recommended and effective approach for optimizing treatment in patients with schizophrenia, regardless of the stage of the illness, involves the application of algorithm-based treatment. Algorithms, distinct from guidelines, provide standardized treatment protocols that enhance clinical decision-making, support treatment choices, minimize errors, allow prompt selection of the best treatment, rely on evidence-based medicine, and address practical issues not covered by clinical trial data [Citation14].

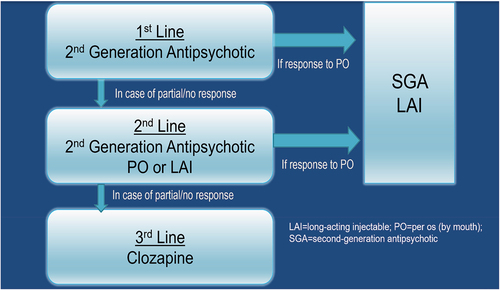

The algorithm for optimizing schizophrenia treatment has two primary goals (): firstly, preventing relapse through the early introduction of long-acting therapies, and secondly, identifying patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia from the outset. This early identification aims to minimize the duration of ineffective antipsychotic treatment, reduce untreated psychosis duration, and facilitate the early use of clozapine, the most appropriate treatment for resistant cases.

The algorithm involves the routine use of rating scales (CGI and BPRS) and clear response definitions, enabling the identification of non-responders early in the course of illness. Long-acting therapies are then offered to responders as a frontline treatment due to their superior effectiveness in relapse prevention compared to oral antipsychotics. Their advantage lies in providing clinicians with a clear understanding of treatment adherence, unlike oral medications where adherence levels are unknown and often wrongly estimated.

Similarly, clozapine is recommended early in the treatment course for patients with treatment-refractory illness. This early positioning reduces the duration of untreated psychosis effectively, lessens the duration of psychotic symptoms, and improves the response to clozapine.

Unfortunately, both long-acting therapies and clozapine are commonly underused and positioned later in the treatment course, possibly contributing to less favorable outcomes in patients with schizophrenia. The algorithm emphasizes the importance of early implementation of these treatments to enhance patient outcomes [Citation15].

5. Untangling the methodological challenges: oral treatment vs. LAI in schizophrenia management

Our algorithm recommends the early positioning of long-acting injectables (LAI) in the treatment course and suggests preferring LAI over oral treatment due to their superior efficacy in relapse prevention. This early positioning may raise questions, as the comparison between LAI and oral treatments in schizophrenia has been widely debated over the years and faces significant methodological challenges.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) often encounter inherent biases when comparing these treatments. One major issue is that RCTs typically include more adherent patients, which artificially enhances adherence to oral medications. Consequently, RCTs represent only about 20% of real-life schizophrenia patients, making it difficult to generalize their findings.

The effectiveness of LAIs has been questioned due to inconsistent findings in the clinical literature. Meta-analyses of RCTs indicate that LAIs are not significantly superior to oral treatments. However, when study designs shift toward prospective and retrospective observational studies, LAIs demonstrate a significant advantage over oral medications. This suggests that the study design itself plays a crucial role in the observed outcomes [Citation16].

Overall, the debate on the effectiveness of LAIs versus oral treatments in schizophrenia is complex, influenced by the methodological constraints of different study designs.

An example to the above is a recent study that compared long-acting injectable (LAI) versus oral treatment, with the primary outcome measure being all-cause discontinuation. However, among the reasons counted for discontinuation, the investigators included factors where no difference is expected between LAI and oral medications, such as treatment response or tolerability. These factors are not strengths of LAI over oral treatment, and no advantage is expected in them. As expected, the combined analysis of all-cause discontinuation showed no advantage for LAI over oral medication. However, the area where LAI was expected to have an advantage over oral treatment, is in adherence, provided other reasons – where LAI has no expected benefit – are excluded. Indeed, LAI showed no benefit over oral treatment in terms of combined all-cause discontinuation. However, when the reasons without an expected LAI advantage were removed (response and tolerability), LAI significantly outperformed oral treatment [Citation17].

Despite many methodological challenges, recent evidence suggests a clear advantage of long-acting injectable (LAI) over oral treatment in preventing relapse in schizophrenia. A recent meta-analysis, the first to include all available evidence on LAIs versus oral antipsychotics across randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort, and pre – post study designs, offers a comprehensive comparison. This analysis incorporated at least 1.5 times the number of studies compared to previous meta-analyses, which targeted each study design separately, and evaluated all meta-analyzable outcomes. It found that LAIs were consistently more effective than oral antipsychotics in preventing hospitalization for schizophrenia across various study designs. The summary effect size was small in RCTs and cohort studies but large in pre – post studies [Citation18].

These findings indicate that LAIs have a significant and substantial risk benefit over oral antipsychotics in preventing hospitalization or relapse. These benefits were observed across RCTs, cohort studies, and pre – post studies, despite the inherent limitations of each study design. The results suggest potential benefits of increased use of LAIs in clinical practice for patients with schizophrenia.

Additionally, a real-world effectiveness study of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of nearly thirty thousand patients with schizophrenia showed that LAIs, along with clozapine, had the highest rates of relapse prevention. The risk of rehospitalization was about 20% to 30% lower with LAI treatments compared to equivalent oral formulations [Citation19]

Taken together, studies with appropriate methodology demonstrate that LAI treatment outperforms oral treatment in the majority of patients with schizophrenia in terms of preventing relapse.

6. Navigating limitations: cognitive impairment and treatment resistance in schizophrenia

Although schizophrenia is generally a highly treatable illness, we must acknowledge the challenges that cannot be successfully addressed through psychopharmacological means.

Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia: A subset of patients inevitably experiences cognitive impairment. While current antipsychotic medications do not adequately address these deficits, Cognitive Remediation (CR) is a noteworthy non-pharmacological intervention. CR aims to improve cognitive processes and enhance overall functioning in schizophrenia and is recommended in treatment guidelines in several countries. Meta-analyses show that CR positively impacts global cognition and functioning. Effective CR involves a trained therapist, intensive practice, cognitive strategy development, and integration with psychosocial rehabilitation [Citation5].

Treatment-Refractory Schizophrenia (TRS): Although most patients with schizophrenia respond to antipsychotic medications, a subset experiences positive symptoms that cannot be controlled by non-clozapine antipsychotics [Citation20,Citation21]. This group is classified as having treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS). While clozapine can manage the positive symptoms in some TRS patients, there are those who do not respond even to clozapine. These patients are categorized as having ultra-treatment-resistant schizophrenia (URS) [Citation22,Citation23]. Some individuals in the TRS/URS categories likely develop this condition following relapse [Citation11], while others exhibit this form of illness from the onset [Citation21]. Those with URS from the outset have a refractory form of schizophrenia that is particularly difficult to manage pharmacologically, leading to a poor prognosis that current treatments cannot effectively address.

7. Expert opinion

The question regarding the prognosis of schizophrenia remains unanswered, yet it is still valid. Decades of research have indicated a poor outcome for schizophrenia, with an inevitable downhill trajectory in the course of the illness and a rarity of good outcomes for the majority of patients [Citation24]. However, it is essential to recognize that the studies providing this information focus on patients who are non-adherent with treatment, never received treatment, or never received optimized treatment, leading to multiple relapses.

Furthermore, these studies often involve patients with comorbidities such as intellectual disability and substance use disorders, which complicate and negatively impact the outcome and prognosis of schizophrenia. Unfortunately, long-term studies investigating the prognosis of schizophrenia in patients who were effectively and continuously treated from the onset of illness, maintained adherence to treatment, and never experienced relapse are not available.

Existing evidence indicates that a significant portion of patients with schizophrenia either goes untreated, receives inconsistent treatment, or not treated effectively. Psychopharmacological tools for effective treatment and relapse prevention, such as Long-Acting Injectables (LAI) and clozapine, are underutilized, often introduced later in the course of illness after relapse-related damage has occurred.

Legal tools, like community treatment orders, which can assist in optimizing treatment, are seldom employed, and only a minority of clinicians utilize the available effective means (medical or legal) to enhance care and treatment. It is not surprising that schizophrenia has garnered a bad reputation, fostering therapeutic nihilism, prevailing pessimism, and stigma.

Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous and complex syndrome, characterized by various subtypes with distinct clinical manifestations, differing responses to treatment, and diverse illness trajectories. Some patients may experience a debilitating chronic illness, while others might have only a single episode of schizophrenia.

The syndrome’s heterogeneity is so pronounced that some clinicians view it as a collection of different syndromes grouped under the title of schizophrenia. These illnesses share the common feature of psychotic symptoms but differ significantly in their biological underpinnings and course of illness [Citation22,Citation23].

This diversity also impacts treatment. Although there is a consensus that antipsychotics are the cornerstone of schizophrenia treatment, there remains an ongoing debate about the duration of such treatment – whether it should be lifelong or intermittent – and whether the benefits of antipsychotics always outweigh their risks [Citation25]. Some longitudinal studies suggest that a subset of patients with schizophrenia may not benefit from antipsychotic medications at all [Citation26]. While these studies can be challenging to interpret due to methodological issues, it is clear to clinicians that, despite general recommendations, antipsychotics may pose more risks than benefits for certain patients. Similarly, lifelong antipsychotic treatment, though beneficial and necessary for some, may harm others [Citation25,Citation27].

Psychopharmacological treatment for schizophrenia is not a panacea; there are no easy solutions or magic bullets. Personalized treatment plans, considering each patient’s unique circumstances and needs, are crucial. Decisions regarding initiating, continuing, or discontinuing medication should be made collaboratively, if possible, among the patient, their family, and the clinician, weighing the risks and benefits. Antipsychotic medications should be integrated with psychosocial interventions, such as psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and support systems, which are essential components of a comprehensive treatment plan.

The algorithm presented here, should be used as a roadmap. While antipsychotics are not universally recommended for every patient with schizophrenia, many can benefit from optimizing antipsychotic treatment to prevent relapse. Evidence strongly suggests that schizophrenia is highly treatable, but too often, patients do not receive optimized treatment and suffer from preventable, sometimes catastrophic relapses. For many patients, optimizing treatment could significantly improve their journey with the illness and lead to better outcomes. By considering long-term outcomes and implementing timely interventions, we can potentially achieve more favorable results than those typically observed in individuals with this syndrome.

Declaration of interest

O Agid has served on the Advisory Boards of and acted as a consultant for Janssen-Ortho (Johnson & Johnson), Otsuka, Lundbeck, Allergan/AbbVie, Mylan/Viatris and Teva Pharmaceuticals. He has also served as a speaker for Janssen-Ortho (Johnson & Johnson), Lundbeck, Otsuka, Mylan/Viatris, HLS Therapeutics and Allergan/AbbVie. O Agid has also received research funding from Janssen-Ortho (Johnson & Johnson), Lundbeck, Otsuka and Boehringer Ingelheim. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks his mentors, Dr. Gary Remington and Dr. Robert Zipursky.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kendler KS. The development of kraepelin’s concept of dementia praecox: a close reading of relevant texts. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Nov 1;77(11):1181–1187. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1266

- Collaborators GBDMD. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022 Feb;9(2):137–150. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3

- Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 Apr;156(4):544–549. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.544

- Malla AK, Norman RM, Manchanda R, et al. Status of patients with first-episode psychosis after one year of phase-specific community-oriented treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2002 Apr;53(4):458–463. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.4.458

- Harvey PD, Bosia M, Cavallaro R, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia: an expert group paper on the current state of the art. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2022 Sep;29:100249. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2022.100249

- Zipursky RB, Reilly TJ, Murray RM. The myth of schizophrenia as a progressive brain disease. Schizophr Bull. 2013 Nov;39(6):1363–1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs135

- DeLisi LE. The concept of progressive brain change in schizophrenia: implications for understanding schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008 Mar;34(2):312–321. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm164

- Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Bertens MG, et al. Volume changes in gray matter in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 Feb;159(2):244–250. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.244

- Vita A, De Peri L, Deste G, et al. Progressive loss of cortical gray matter in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of longitudinal MRI studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2012 Nov 20;2(11):e190. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.116

- Kane JM. Treatment adherence and long-term outcomes. CNS Spectr. 2007 Oct;12(10 Suppl 17):21–26. doi: 10.1017/S1092852900026304

- Takeuchi H, Siu C, Remington G, et al. Does relapse contribute to treatment resistance? Antipsychotic response in first- vs. second-episode schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018 Nov 22;44(6):1036–1042. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0278-3

- Andreasen NC, Liu D, Ziebell S, et al. Relapse duration, treatment intensity, and brain tissue loss in schizophrenia: a prospective longitudinal MRI study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Jun;170(6):609–615. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12050674

- Caseiro O, Perez-Iglesias R, Mata I, et al. Predicting relapse after a first episode of non-affective psychosis: a three-year follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res. 2012 Aug;46(8):1099–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.05.001

- Takeuchi H, Takekita Y, Hori H, et al. Pharmacological treatment algorithms for the acute phase, agitation, and maintenance phase of first-episode schizophrenia: Japanese society of clinical neuropsychopharmacology treatment algorithms. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2021 Nov;36(6):e2804. doi: 10.1002/hup.2804

- Agid O, Arenovich T, Sajeev G, et al. An algorithm-based approach to first-episode schizophrenia: response rates over 3 prospective antipsychotic trials with a retrospective data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011 Nov;72(11):1439–1444. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05785yel

- Kirson NY, Weiden PJ, Yermakov S, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of depot versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: synthesizing results across different research designs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013 Jun;74(6):568–575. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r08167

- Winter-van Rossum I, Weiser M, Galderisi S, et al. Efficacy of oral versus long-acting antipsychotic treatment in patients with early-phase schizophrenia in Europe and Israel: a large-scale, open-label, randomised trial (EULAST). Lancet Psychiatry. 2023 Mar;10(3):197–208. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00005-6

- Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021 May;8(5):387–404. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00039-0

- Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Majak M, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29 823 Patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jul 1;74(7):686–693. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1322

- Bozzatello P, Bellino S, Rocca P. Predictive factors of treatment resistance in first episode of psychosis: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:67. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00067

- Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017 Aug;47(11):1981–1989. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000435

- Farooq S, Agid O, Foussias G, et al. Using treatment response to subtype schizophrenia: proposal for a new paradigm in classification. Schizophr Bull. 2013 Nov;39(6):1169–1172. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt137

- Lee J, Takeuchi H, Fervaha G, et al. Subtyping schizophrenia by treatment response: antipsychotic development and the central role of positive symptoms. Can J Psychiatry. 2015 Nov;60(11):515–522. doi: 10.1177/070674371506001107

- Zipursky RB. Why are the outcomes in patients with schizophrenia so poor? J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(Suppl 2):20–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13065su1.05

- Zipursky RB, Odejayi G, Agid O, et al. You say “schizophrenia” and I say “psychosis”: just tell me when I can come off this medication. Schizophr Res. 2020 Nov;225:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.02.009

- Sturup AE, Nordentoft M, Jimenez-Solem E, et al. Discontinuation of antipsychotics in individuals with first-episode schizophrenia and its association to functional outcomes, hospitalization and death: a register-based nationwide follow-up study. Psychol Med. 2023 Aug;53(11):5033–5041. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722002021

- Correll CU, Rubio JM, Kane JM. What is the risk-benefit ratio of long-term antipsychotic treatment in people with schizophrenia? World Psychiatry. 2018 Jun;17(2):149–160. doi: 10.1002/wps.20516