ABSTRACT

Background: Despite several studies focusing on the negative aspects of general medicine, the speciality seems attractive for students. Researchers from the European General Practice Research Network created a group to study job satisfaction in general practice. The aim of this eight-country European study was to determine which positive view students have about general practice.

Method: Systematic review of the literature from Pubmed, Embase and Cochrane databases. Articles published between 01/01/2000 and 12/31/2018 were searched and analysed by two researchers working blind. The data on satisfaction factors were extracted from the full text article used as verbatims. Then the data were coded with a thematic analysis.

Results: 24 articles out of 414 were selected. Satisfaction factors were classified: teaching of general practice, workplace and organisational freedom, quality of life, variety in practice, workload balance and income. The analysis highlighted intellectual stimulation and the relationship built with patients and other professionals.

Conclusion: Literature on the appeal of general practice for students revealed many factors of job satisfaction in general practice. It is possible to create a global view of a satisfied GP on the students’ opinion. Courses and clerkships in general practice with positive role models are determining factors in career choice.

Introduction

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries are facing a shortage of general practitioners (GPs) because of a declining physician population and a lack of interest from students in this speciality. The World Health Organisation (WHO) also stressed the central role of general practice, especially in the different European healthcare systems [Citation1]. The European Commission estimated that the demand for healthcare is increasing as the population ages but the number of physicians is decreasing. In 2009, 30% of all European medical physicians were over 55 years old and by 2020 over 60,000 (3.2%) of them will retire annually. Consequently, in 2020, Europe overall will face a shortage of 230,000 physicians [Citation1]. The Association of American Medical Colleges estimates that in 2020, the United States will face a shortage of 45,000 primary care physicians. The National Health System believes that the shortage of GPs in the United Kingdom will be about 16,000 in 2021. This estimate is corroborated by the Royal College of General Practitioners [Citation2].

The OECD countries tried different strategies to increase the numbers of GPs because of the looming GP shortage but, so far, they have been unsuccessful. Some researchers have focused on the negative aspects of the profession. They highlighted the reasons why doctors are leaving clinical practice [Citation3–Citation5]. Nevertheless, some medical students and trainees choose the path of general practice and are attracted by this speciality. Throughout the literature, several studies identified all the satisfaction factors that GPs find in their work that would encourage students to choose general practice.

EGPRN brought together an eight-country research group to consider the positive aspects of general practice [Citation6]. The aim of this research group was to determine what attracts those students who choose general practice in order to use this information to develop new strategies to obtain a higher intake into the profession.

Method

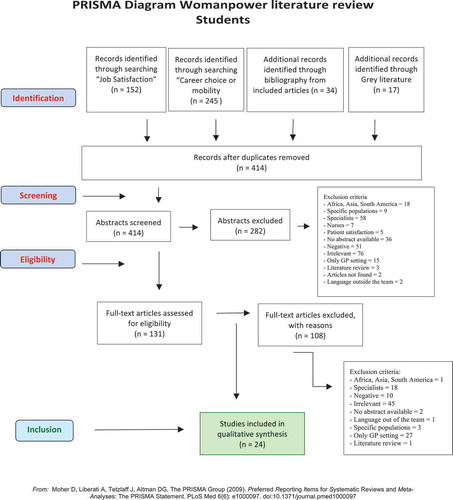

The search strategy used to select articles of interest was based on a systematic literature review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis statement (PRISMA) [Citation7,Citation8] ( – Annexes).

Table 1. Quality appraisal.

Relevant studies were identified by a systematic research in the databases PubMed and Embase. The time interval selected for the bibliography screening was from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2018. The target population of the literature review comprised medical students and trainees.

The database-specific search included the following equitation for PubMed: ((‘Family Practice’[Majr] OR ‘General Practitioners’[Majr] OR ‘Physicians, Family’[Majr]) AND (‘Career Choice’[Majr] OR ‘Career Mobility’[Majr])) AND hasabstract[text] AND (‘2000/01/01’[PDAT]: ‘2018/12/31’[PDAT]) and ((‘Family Practice’[Majr] OR ‘General Practitioners’[Majr]) OR ‘Physicians, Family’[Majr]) AND ‘Job satisfaction’[Majr] AND hasabstract[text] AND (‘2000/01/01’[PDAT]: ‘2018/12/31’[PDAT]).

‘Job satisfaction’, ‘career choice’ and ‘career mobility’ were chosen by the research team because they were the best possible MESH terms to describe positive factors at work. The use of a MESH term was efficient because it included all possible synonyms.

The inclusion criteria were:

The study is about general practice

The study was on career perspectives

The study described the working conditions in primary care

The study described satisfaction in general practice

The study described the medical education for general practice (vocational training, lectures …)

The exclusion criteria were:

01- The study was conducted in Africa, Asia, South America

02- The research was about specific populations

03- Specialists or specific doctors

04- Nurses but no doctors

05- The research was about patient’s satisfaction

06- The article had no abstract available or was an editorial or a protocol without a result

07- Research on negative topics about general practice

08- The study was irrelevant to the research question

09- The study focused on GPs and not on students

10- The language was not spoken by any member of the team

11- Literature review

12- Article not found: the research team was unable to find the article

All documents were analysed for identification, screening and inclusion by two separate researchers using inclusion and exclusion criteria. To be included, the article had to score ‘yes’ on every question. This quality appraisal form was adapted from the quality appraisal form of the CASP [Citation9,Citation10].

For all the articles identified, the following information was extracted: title, authors, year, journal, language, country, research question, research type, method, detailed method and setting.

The data extraction and analysis were based on a descriptive approach used in qualitative studies [Citation11]. For the articles included, the two researchers independently coded verbatim data using open codes, interpretative codes and themes. Open coding requires reading through data several times and creating labels for data reduction and clustering in order to summarise the essence. Interpretative coding identifies the relationship or central tenets among the open codes. Finally, these codes have been organised into sub-themes and themes, this by comparing themes to avoid redundancies.

Results

The research group found 414 articles after removing duplicates. Many studies had research questions on a specific problem in general practice, but not specifically on job satisfaction or career choice. Finally, 24 articles were selected for the study. The full process is described in the PRISMA flow chart in . Nearly all the studies included (n = 23) were published in the English language. One article was published in German and the results of this study were analysed by the German team.

Analysis of the data

The open coding of the included articles led to 196 open codes. Clustering of the codes led to the formulation of fifteen interpretative codes, which were classified into four major themes. The four main themes are GP in society, organisation of the practice, characteristics of GP work content and medical education. gives an overview of the results from the studies included in the review [Citation12–Citation35].

Table 2. Overview of the results from the studies included.

Major themes

GP in society

This theme is related to the image of GPs in society and in their personal environment but also to the importance of the living environment for potential candidates for general practice [Citation22,Citation31,Citation32,Citation34]. GPs wanted responsibilities and professional recognition for quality of work [Citation28,Citation31]. They liked the professional recognition [Citation30], that goes with the job, whether it be from family, patients or the community [Citation36].

Senior GP support, family support, support from friends, the influence of media and collaboration networks with specialists and paramedics all influenced the students’ career choice [Citation30,Citation37]. Shorter residency and lifestyle advantages were also decisive because of the improvement in quality of life [Citation31,Citation32]. The family of a young GP needs to feel at home in the community. A good living environment has enough facilities for leisure time and has good schools. Future GPs want to have their family and friends in the neighbourhood [Citation15].

The type of community background the students themselves come from is important. Students and trainees from a rural background are more likely to choose to become a GP [Citation21,Citation37]. Students from a rural background (90%) would tend to look for a practice location in rural areas [Citation14,Citation16]. The literature found that students and trainees liked the lifestyle advantages of the profession [Citation29].

General practice organisation

The topic of workload and income was widely discussed in selected articles. This theme was mentioned in 17 of the 24 articles included. Medical students seemed to be worried about the heavy workload. Meli et al. found that the total GP satisfaction score was negatively correlated with actual hours of work per week [Citation19]. Future physicians want a good work–life balance. Both male and female students want the opportunity to work part-time [Citation13,Citation14]. Moreover, general practice is a profession with job security and a good income [Citation20]. They seek a reasonable workload to fit in with family life [Citation26] and allow time for leisure activities [Citation35]. Young GPs also favoured an equitable income [Citation34] and valued job security [Citation20].

Freedom to choose workplace and work organisation: This was the most studied theme. Twenty research studies investigated this subject which is a very significant area [Citation20,Citation22].

Furthermore, students and trainees liked the freedom to organise their working hours and their work methods to suit their lifestyle [Citation28]. They liked to have autonomy [Citation26,Citation35] and less hospital orientation [Citation27]. Work in general practice can be viewed positively if there is freedom to organise the work. With the possibility of flexible hours [Citation28], they could manage their schedule. Working conditions are an important determinant of satisfaction if they have been chosen [Citation18,Citation20,Citation22].

Most students want to work in a well-organised group practice, with pleasant colleagues and good supportive staff. In these practices, it is possible to work part-time with flexible working hours. Students are attracted by a low requirement to provide out-of-hours service, especially at night [Citation20]. Practices need to be located in an environment with hospitals and good specialists. A good relationship with other professionals was important to attract young GPs [Citation32].

Characteristics of the work content

Dedication and individual commitment are important characteristics required to become a GP [Citation22,Citation25,Citation26].

General practice is a clinical discipline with a high-intellectual level of stimulation [Citation34] and with a wide variety of pathologies [Citation33]. Students and trainees liked to take care of patients of all ages [Citation31] and backgrounds and to give medical attention to all kinds of health issues, even the most commonplace ones, throughout the lifespan of a patient [Citation32]. They enjoyed preventive medicine [Citation20,Citation22,Citation35] and family-focused medicine [Citation22]. Students see GPs as important figures, being the patient’s primary care physician and being the one who coordinates with the hospital or specialists [Citation29]. Students and trainees appreciated the wide range of patients [Citation22], the broad scope of practice [Citation22,Citation31,Citation33] and the holistic approach that creates variety in practice [Citation26,Citation30].

Having a key role in the management of patients’ care was a positive factor. Petek Šter et al. found that students appreciated a long-term physician–patient relationship which enabled patient-centred care and took into account the prevention and treatment of physical and psychosocial problems [Citation17]. Additionally, they enjoyed the bio-psychosocial focus of healthcare and the high responsibility involved [Citation29].

The doctor–patient relationship was studied by a number of researchers [Citation22,Citation26]. For the GP, the patient is the focus of care. The long-term doctor–patient relationships were important [Citation15].

The variety in practice [Citation33]: Students and trainees liked to take care of patients of all ages [Citation31] and backgrounds and to give medical attention to all kinds of health issues, even the most commonplace ones, throughout the lifespan of a patient [Citation32]. They enjoyed preventive medicine [Citation20,Citation22,Citation35] and family-focused medicine [Citation22]. They attached considerable importance to being the patient’s primary care physician and the one who coordinated with the hospital or specialists [Citation29]. Students and trainees appreciated the wide range of patients [Citation22], the broad scope of practice [Citation22,Citation31,Citation33] and the holistic approach that creates variety in practice [Citation26,Citation30].

Medical education

The last major theme emphasised the quality of general practice teaching in faculty. It is a determinant factor in a career choice with clerkship. The stages and clerkships permitted to learn specific competencies and students appreciate the specific context of general practice. Among students, a positive image of teachers and trainers within general practice is associated with a higher interest in general practice [Citation19]. The length and intensity of general practice programmes at the university have a positive influence on choice [Citation31]. Positive experience and role models were highly valued by students and trainees [Citation19,Citation25].

Discussion

Main results

Students and trainees have positive views on general practice when they are exposed to high-quality education as early, and with as much impact, as possible during the curriculum. Autonomous motivation for choosing general practice is determined by intrinsic motivation such as the desire to help people and positive valuation by parents and society. This is in line with Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory [Citation38]. Another important result of this literature review is that the positive factors for students are very similar to those for older GPs [Citation39]. This supports a ‘trans-generational’ portrait of the doctor satisfied with his/her job. Students and GPs have the same expectations towards workload, income, freedom of workplace and in work organisation. Both valued variety in their practice. As Roos et al. mentioned, more than two-thirds rated themselves as satisfied (very satisfied – fairly satisfied) with time spent at work or training and the majority of trainees would choose general practice again, given a second chance [Citation18].

What was already known and was highlighted by this review is the role of clinical teaching in initial medical education. Internships with a senior GP provide a positive role model [Citation19,Citation25] and influence the choices of students and trainees in their future practice. Non-specific professional aspects, such as income or workload balance, are always important for students, as in every profession [Citation18,Citation22].

Freedom in work management and organisation is also an important element to take into consideration [Citation20,Citation22]. They are the major factors which have an impact on students’ career. The individual characteristic of GP vocation is underrepresented because it has not been studied in any depth in surveys [Citation22,Citation26,Citation40]. Some factors that are specific to general practice activities, such as intellectual stimulation, the holistic approach and variety in practice become more and more important over time but are not determinant factors in career choice for students [Citation33]. Intellectual stimulation would be a surprising item as general practice was often mistakenly considered to be a speciality with a low-intellectual content. Some students commented as follows about general practice: ‘too dull and monotonous, not practically challenging, too many “social” patients, too much paperwork and administrative work’ [Citation41]. This literature review has shown that this is not true. Students are attracted by the competencies needed to become a GP.

Students and trainees from a rural background are more likely to choose to become a GP. This was a result found in previous literature [Citation21,Citation37,Citation40,Citation42]. The opportunity to strike a good balance between professional and private life should be taken into account by all policy-makers to enhance the general practice workforce. Social recognition and respect are values that influence the career choice of students and trainees so stakeholders and health systems must take this into consideration [Citation28,Citation31]. Articles conducted by questionnaire fail to take into consideration the competence and vocation of students. In the literature, individual characteristics required to be a GP and doctor intellectual stimulation is important for students.

Comparison with previous reviews

Senf et al. conducted a literature review in 2003 on factors related to the choice of family medicine [Citation43]. Their results indicated that early career intentions are a good predictor of eventual speciality choice. They found that spending time in family medicine during the process of medical education increased the number of graduates in family medicine.

Strength and limits of the study

The strength of this literature review lies in its ability to show an overall view of the positive factors, for students and trainees, which lead to GP satisfaction. There could be a selection bias because only articles in English were included, with the exception of one article in German.

There could be confounding factors or interpretation bias because of the differences between the social health systems and the difficulties in linguistic understanding. This bias was limited by the fact that the research team was international and each member worked with users of health systems from different countries. Previous research mainly focused on the health system and problems of the country concerned in the study. Most studies were carried out by questionnaire, focusing on issues of organisation or business and did not fit into the heart of general practice. Those studies showed only a partial view of the positive aspects experienced by students about general practice. Those articles were not selected as ‘not relevant’ because their objective was not the satisfaction of the profession of GP. Their content was not rich enough. These articles would not have changed the results.

Conclusion

The literature review provides a general overview of the satisfaction of students and trainees attracted to general practice. Intrinsic motivation and positive valuation are important drivers for choosing general practice. Medical students listen to the influence of family and community. The quality of teaching and clerkships in general practice is also an important factor. Medical schools should organise high-quality courses and clerkships in primary care, with positive role models who actively promote the clinical work of a GP. General practice clerkships should show well-organised practice with professionals who are examples of people with a good work–life balance. Governments should invest in opportunities for good practice and well-organised out-of-hours services. As a main conclusion, an alternative way for stakeholders to continuously improve the primary care workforce could be to consider the positive factors in health system policies rather than the negative ones.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical approval

The Ethical Committee of the ‘Université de Bretagne Occidentale’ (UBO), France approved the study for the whole of Europe: Decision N ° 6/5 of 5 December 2011.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank the European General Practice Research Network for its support in the survey. The authors are grateful for the comments and suggestions provided by Alex Gillman and the work of PM Bosser, S Drevillon, W Haertle, A Gicquel and G Huiban.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Evans T, Van Lerberghe W. The world health report 2008: primary health care : now more than ever. World Health Organization, editor. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

- Practitioners RC of G. New league table reveals GP shortages across England, as patients set to wait week or more to see family doctor on 67m occasions [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Apr 22]. Available from: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/news/2015/february/new-league-table-reveals-gp-shortages-across-england.aspx

- Dagrada H, Verbanck P, Kornreich C. General practitioner burnout: risk factors. Rev Med Brux. 2011;32:407–412.

- Lebensohn P, Dodds S, Benn R, et al. Resident wellness behaviors: relationship to stress, depression, and burnout. Fam Med. 2013;45:541–549.

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2016 Apr 10];81:354–373. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16565188

- Hummers-Pradier E, Beyer M, Chevallier P, et al. Series: the research agenda for general practice and primary health care in Europe. Part 4. Results: specific problem solving skills. Eur J Gen Pract. 2010;16:174–181.

- Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151.

- Beller EM, Glasziou PP, Altman DG, et al. PRISMA for abstracts: reporting systematic reviews in journal and conference abstracts. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001419.

- Ibbotson T, Grimshaw J, Grant A. Evaluation of a programme of workshops for promoting the teaching of critical appraisal skills. Med Educ. 1998;32:486–491.

- Taylor RS, Reeves BC, Ewings PE, et al. Critical appraisal skills training for health care professionals: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2004;4:30.

- Finlay L. Debating phenomenological research methods. Phenomenol Pract [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2014 Aug 28];3:6–25. Available from: https://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/pandpr/article/viewFile/19818/15336

- Phillips J, Prunuske J, Fitzpatrick L, et al. Initial development and validation of a family medicine attitudes questionnaire. Fam Med. 2018;50:47–51.

- Gisler LB, Bachofner M, Moser-Bucher CN, et al. From practice employee to (co-)owner: young GPs predict their future careers: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18:12.

- Harding C, Seal A, McGirr J, et al. General practice registrars’ intentions for future practice: implications for rural medical workforce planning. Aust J Prim Health. 2016;22:440.

- Deutsch T, Lippmann S, Frese T, et al. Who wants to become a general practitioner? Student and curriculum factors associated with choosing a GP career–a multivariable analysis with particular consideration of practice-orientated GP courses. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33:47–53.

- Wright KM, Ryan ER, Gatta JL, et al. Finding the perfect match: factors that influence family medicine residency selection. Fam Med. 2016;48:279–285.

- Petek Šter M, Švab I, Šter B. Prediction of intended career choice in family medicine using artificial neural networks. Eur J Gen Pract. 2015;21:63–69.

- Roos M, Watson J, Wensing M, et al. Motivation for career choice and job satisfaction of GP trainees and newly qualified GPs across Europe: a seven countries cross-sectional survey. Educ Prim Care. 2014;25:202–210.

- Meli DN, Ng A, Singer S, et al. General practitioner teachers’ job satisfaction and their medical students’ wish to join the field - a correlational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:50.

- Steinhäuser J, Miksch A, Hermann K, et al. What do medical students think of family medicine? Results of an online cross-sectional study in the federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2013;138:2137–2142.

- Gill H, McLeod S, Duerksen K, et al. Factors influencing medical students’ choice of family medicine: effects of rural versus urban background. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e649–57.

- Zurro AM, Villa JJ, Hijar AM, et al. Medical student attitudes towards family medicine in Spain: a statewide analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:47.

- Kiolbassa K, Miksch A, Hermann K, et al. Becoming a general practitioner–which factors have most impact on career choice of medical students? BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:25.

- Watson J, Humphrey A, Peters-Klimm F, et al. Motivation and satisfaction in GP training: a UK cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e645–9.

- Laurence CO, Williamson V, Sumner KE, et al. “Latte rural”: the tangible and intangible factors important in the choice of a rural practice by recent GP graduates. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10:1316.

- Elliott T, Bromley T, Chur-Hansen A, et al. Expectations and experiences associated with rural GP placements. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9:1264.

- Feldman K, Woloschuk W, Gowans M, et al. The difference between medical students interested in rural family medicine versus urban family or specialty medicine. Can J Rural Med. 2008;13:73–79.

- Hogg R, Spriggs B, Cook V. Do medical students want a career in general practice? A rich mix of influences!. Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.; 2008.

- Lu DJ, Hakes J, Bai M, et al. Rural intentions: factors affecting the career choices of family medicine graduates. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1016–1017.e5.

- Thistlethwaite J, Kidd MR, Leeder S, et al. Enhancing the choice of general practice as a career. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37:964–968.

- Scott I, Wright B, Brenneis F, et al. Why would I choose a career in family medicine?: reflections of medical students at 3 universities. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1956–1957.

- Sinclair HK, Ritchie LD, Lee AJ. A future career in general practice? A longitudinal study of medical students and pre-registration house officers. Eur J Gen Pract. 2006;12:120–127.

- Jordan J, Brown JB, Russell G. Choosing family medicine. What influences medical students? Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:1131–1137.

- Somers GT, Young AE, Strasser R. Rural career choice issues as reported by first year medical students and rural general practitioners. Aust J Rural Health. 2001;9(Suppl 1):S6–13.

- Weaver SP, Mills TL, Passmore C. Job satisfaction of family practice residents. Fam Med. 2001;33:678–682.

- Henderson E, Berlin A, Fuller J. Attitude of medical students towards general practice and general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:359–363.

- Bunker J, Shadbolt N. Choosing general practice as a career - the influences of education and training. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38:341–344.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can Psychol Can. 2008;49:182–185.

- Le Floch B, Bastiaens H, Le Reste JY, et al. Which positive factors determine the GP satisfaction in clinical practice? A systematic literature review. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17.

- Williamson M, Gormley A, Bills J, et al. The new rural health curriculum at Dunedin school of medicine: how has it influenced the attitudes of medical students to a career in rural general practice? N Z Med J. 2003;116:U537.

- Lambert T, Goldacre R, Smith F, et al. Reasons why doctors choose or reject careers in general practice: national surveys. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:851–858.

- Woloschuk W, Tarrant M. Does a rural educational experience influence students’ likelihood of rural practice? Impact of student background and gender. Med Educ [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2013 Dec 29];36:241–247. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11879514

- Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:502–512.