ABSTRACT

General practice (GP) supervisors – the key resource for training the future GP workforce – are often described as ‘occupying a role’ or enacting a series of roles. However, as much of the discourse uses a lay understanding of role, or merely hints at theory, a significant body of theoretical literature is underutilised. We reasoned that a more rigorous application of role theory might provide a conceptually clearer account of the GP-supervisor’s job. To this end, we describe the use of organisational role theory and job analysis to identify and define the roles of the Australian GP-supervisor. Our search of the academic literature identified 64 role titles, which we condensed to an initial iteration of core roles, using inclusion and exclusion criteria. We analysed GP training organisations’ documents to map embedded supervisory tasks against our list of roles to verify their presence, review our role titles and definitions, and look for additional roles that we may have missed. We used subject matter experts iteratively, to authenticate a final list of ten roles and their accompanying definitions, which can be used to support Australian GP-supervisors to perform effectively. We encourage those who support GP-supervisors in other countries and those who educate other health professionals in primary care settings to review the roles to judge whether they are transferable to their contexts.

Introduction

In Australia, the majority of general practice (GP) registrars’ training occurs in accredited community GP-training posts. Trainees work under the supervision of experienced general practitioners, known respectively as GP-supervisors in Australia and GP-trainers in the UK, who are on hand to observe, work with, and teach in response to both ad hoc requests for support and in protected teaching sessions.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) state that ‘Supervisors are the backbone of the general practice training program’ [Citation1,p.19]. The use of this metaphor conveys that GP-supervisors are the key resource upon which general practice training is based. As the backbone acts as the fundamental structural support in keeping humans upright, GP-supervisors give the training system its strength, and without whom the system cannot function. Recognising this, Wearne et al. stated in their review of general practitioners as supervisors, “It is important to clearly define [supervisors’] roles and what makes them effective. [Citation2,p.1161, bold added].

Such use of ‘role’ is commonplace when talking or writing about GP-supervisors, either referring to the supervisory role as a formal position or in relation to specific roles which sit beneath this overarching label. For example, Brown and Wearne write in their overview of supervision in GP settings, ‘For the senior postgraduate trainee, the supervisor’s role becomes primarily a mentoring one’ [Citation3,p.8, bold added].

Role may also be used to refer to the specific tasks that supervisors are expected to undertake as a consequence of taking-up a supervisory position. In the aforementioned review, Wearne et al. state, ‘Learning from practice was threatened when residents were used solely as a workforce and therefore an important role of supervisors was to manage residents’ workload’ [Citation2,p.1164, bold added].

While these references to ‘role’ are not a core concept in these authors’ writing, ‘role’ is used more centrally in other writers’ work. In running professional development sessions with new GP-supervisors, we have used Harden and Crosby’s [Citation4] well-cited medical education guide on ‘the twelve roles of the teacher’. Although the paper is targeted at university-based medical educators, it has proved to be a useful resource to ‘kick-start’ discussion with new GP-supervisors about their understandings of the position’s different components. Morgan [Citation5] drew on this guide in his explication of the role of the Australian GP-supervisor, describing five core roles (assessor, clinical educator, mentor, pastoral carer and role model) and seven ‘other’ roles (cultural mentor, doctor, employer, examiner, friend, medical educator, patient).

Whereas the articles cited earlier are evoking a lay understanding of role, Harden, Crosby and Morgan are hinting at a significant body of social science literature on role theory, but without explicit citations or the underpinning of theory that is called for in more contemporary medical education scholarship [see Citation6, for example].

Our collective experiences as a GP-supervisor (GI), supervisors in other contexts (JW and TC), medical educators, and researchers in the GP-training field, have shown ‘role’ to be a useful concept in helping GP-supervisors make sense of what they are expected to do when supervising GP-registrars on a day-to-day basis. Although its lay meaning – the function performed by someone in a particular situation [Citation7] – is easily understood, we reasoned that a more rigorous application of role theory might provide a conceptually clearer account of what GP-supervisors are expected to do in comparison to earlier works and also negate the need to fall back on and translate work that had been developed for other contexts.

The rekindling of a focused interest in ‘role’ came about through our involvement in a project to develop a national professional development curriculum for Australian GP-supervisors [Citation8]. As medical educators, we were faced with the practical problem of developing a curriculum and thought that ‘role’ could be integral to an ‘authentic curriculum’, which would enhance the likelihood of GP-supervisors performing competently in the workplace [see Citation9]. We undertook a form of research that Hammersley [Citation10] labels ‘dedicated practical research’, where the aim was to produce an academically informed understanding of GP-supervisor roles for the curriculum development team during the curriculum development process. In this article, we outline the explicit use of role theory and aspects of job analysis to identify and define the roles of the Australian GP-supervisor.

Methods

Ontological and epistemological stance

Our research integrates ontological realist and epistemological constructivist perspectives. The former posits that there is a real world that exists independently of our perceptions and theories, while the latter suggests that our understanding of this world is constructed from our perspectives [Citation11]. On this basis, it is entirely reasonable to accept that the role of ‘assessor’, for example, is both a construction and that the incorporation of tasks that flow from this role into a job description will have real consequences for how GP-supervisors think about and enact the job; by, for example, understanding that they are expected to undertake workplace-based assessments. Maxwell [Citation11] argues that the integration of these two perspectives is a common-sense basis for conducting social research.

Theoretical stance: role theory

There are different versions of role theory, with a lineage back to the work of Katz and Kahn [Citation12] in the 1960s. We chose to use organisational role theory, framing the GP-supervisor’s position as an occupational role, which prescribes the behaviours that supervisors are expected to conform to, so that they are able to perform their specified tasks and duties effectively [Citation13]. We also privileged a managerial perspective, assuming that people in GP training organisations design the GP-supervisor’s job; that is, the job is planned, task-oriented, and seen as vital to training of the future GP workforce [Citation14].

Reflexivity, methodology and rhetorical choices

We have written reflexively throughout the paper, clearly identifying the ideas on which we have drawn. Our methodological approach is constructivist interpretivist, but more important than this label is the description of how we went about identifying and defining the roles of the Australian GP-supervisor, so that readers can make their own ‘credibility’ assessment [see Citation15,Citation16]. In writing the paper, we have made a rhetorical choice, which suits its qualitative nature; opting, at times, to weave literature, description, analysis, interpretation and details of the aforementioned methodological steps together seamlessly, rather than confine them to discrete sections [Citation17].

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for the project was granted by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project Identification Number 21,426.)

Identifying, naming and defining the roles of the Australian GP-supervisor

We identified ten roles through an iterative process, drawing on three sources: the medical education literature, organisational documents and the perspectives of general practice stakeholders in the full research team (the authors plus additional medical educators, GP-supervisors and a research assistant) and the project’s Expert Advisory Committee, a group of subject matter experts. The Acknowledgements section details the membership of the full research team and the committee.

Building on the relevant literature that was known to us, we searched the academic literature for studies that had used ‘role’ as a framing device for understanding the GP-supervisor’s job; expanding our search to include terms like ‘preceptor’, ‘trainer’ and ‘family medicine’ when the initial search yielded a small number of papers. We extracted role titles and definitions (where given) to create an initial list of 64 roles ().

Table 1. Initial list of role titles extracted from the academic literature.

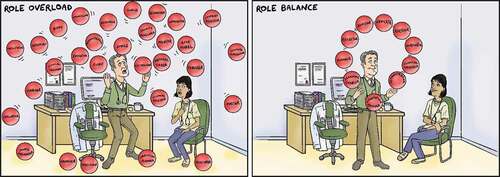

Our documentation of this large number of roles underscores that one can create an almost endless number of roles when thinking about a job [Citation18], but one will reach a point when the incumbent has too many to handle. When this point is reached, the person experiences role overload, which leads to the harmful form of role stress, known as role strain [Citation19].

The proliferation of roles that we found in the literature, combined with apparent conceptual confusion, such as the same label being used to describe different constructs [Citation20], affirmed the importance of clearly defining the roles that are essential for GP-supervisors to perform effectively.

We clustered roles that had similar titles or were conceptually similar (e.g. assessor and student assessor) and kept those that were core to our understanding of the GP-supervisor’s position and consistent with our framing of it as an occupational role. We wrote a draft definition of each role, with the aim of minimising overlap between roles, and excluded roles that were:

overarching position titles, e.g. clinical educator and practice teacher.

more strongly embedded in the clinical role, e.g. physician and professional expert.

extra-roles, that is, roles that are not intrinsic to the job [Citation21], e.g. health advisor and helping hand.

more applicable to university positions, e.g. curriculum developer and study guide producer

related to how roles should be enacted, e.g. enthusiast.

conceptually weak, e.g. guru.

This process resulted in a provisional list of roles with accompanying definitions, which were reviewed and revised by the full project team.

We thought it helpful to unlink the clinical and educational elements of the GP-supervisor’s job; that is, to consider them as two separate jobs, influenced by Stoddard and Brownfield’s [Citation22] assertion that GP-supervisors fulfil two professional roles, that of clinician and that of educator. Their use of ‘role’ mirrors the term’s lay meaning, suggestive of broad clinical and educational functions. As clinicians, it is knowledge of general practice, associated skills and accumulated practice wisdom that enables general practitioners to be accredited as GP-supervisors, and from which the educational role unfolds [Citation23]. The demands of these two professional roles illustrate a commonly reported example of inter-role conflict [Citation18], where GP-supervisors struggle with the competing expectations of each role, that of providing the best care to patients and high-quality education for GP-registrars.

Drawing a boundary between the two professional roles was both an analytic and conceptual choice, which helped in managing the tension between comprehensiveness and parsimoniousness. Specifically, we decided that some roles are intrinsic to the general practitioner’s job and could be attached to it, reasoning that they will enact the knowledge, skills and attitudes related to these clinical sub-roles when performing the supervisory job. This also illustrates that our conceptual ‘trick’ is just that, and ‘in practice’ the clinical and supervisory roles are intertwined [Citation2], so that in performing either job, one will be able to draw on the transferable skills of the other. For example, as a clinician, Australian general practitioners are expected to develop their clinical knowledge and skills once they have become a Fellow of the RACGP, which demands that they enact the role of learner; a role that GP-supervisors will also enact when learning about the process of supervising through professional development activities and the act of supervising.

So as not to overload the GP-supervisor’s job with too many roles, we sought a state of role balance, a concept borrowed from the broader social science literature [Citation24], whereby the job would not suffer from either role overload or role underload (). GP-supervisors have to divide their attention between multiple clinical and educational roles and if the right balance can be maintained across this system of roles, we deduced that they may be less likely to report role strain, be able to fully engage with every role in the total role system, and be more likely to report positive experiences about enacting the job [Citation25].

Drawing on job analysis [Citation18] and document analysis [Citation26], we analysed a selection of documents that prescribe the activities that Australian GP-supervisors are expected to undertake, such as supervisor handbooks, [for example, Citation27] and training standards [for example, 1]. We mapped the tasks identified in these documents against our provisional list of roles to verify their presence, review our role titles and definitions, and look for additional roles that may have been missed in the academic literature. This iteration of the roles was reviewed by the project’s Expert Advisory Group, which resulted in further refinements. Using the perspectives of subject matter experts in this way is called a technical conference in the job analysis literature [Citation18].

The ten roles

The labels for the ten roles, arranged alphabetically, are shown in . Although it may be tempting to try and organise the roles differently, perhaps through clustering the educational roles, or claiming that one role is more important than another; we concluded that there was no added value in doing this. All of the roles are intrinsic to the supervisor’s job and the competent GP-supervisor integrates the knowledge and skills related to all of them in the day-to-day practice of supervising.

Word limitations mean that we are not able to provide each role’s definition within this article, but they are available in Supplementary File 1. Without these definitions the labels serve little purpose. The definitions describe the essential nature of each role and guide supervisors to behave in specific ways in order to perform the specified role effectively. Having a clear understanding of what each role entails is necessary to avoid role ambiguity, which arises when the expectations of a role are unknown or unclear [Citation18]. The definitions will enable supervisors and other stakeholders to have a shared understanding of the job, provide a common language for discussing it and share the professional knowledge of supervising [Citation28]. We encourage those organisations involved in training the Australian GP workforce to facilitate a common language, by using the roles and definitions in future handbooks, guidance documents, policies and procedures.

Trustworthiness

Articulating the ten roles was an interpretive undertaking that should be assessed against the evidentiary standards for qualitative research [Citation29] and dedicated practical research [Citation10]. The evaluative criteria of the latter are less stringent than those for theoretical and scientific research, because practitioners will make functional assessments about the transferability of the findings to their contexts. We have detailed the steps that gave rise to the roles, which we suggest were systematic and sufficiently analytically rigorous. Different sources of data were used in their construction (intertextuality) and the subject matter expertise within the full research team and the Expert Advisory Committee served as member checks, reinforcing our claim that the roles are recognisable to other supervisors, which is indicative of both credibility and ‘fittingness’; that is, the roles are transferable to the range of Australian general practice contexts [Citation30,Citation31].

Application, future work, research and evaluation

We have used organisational role theory and facets of job analysis methodology to identify and define ten credible roles for the contemporary Australian GP-supervisor, which reflect the challenging and complex nature of the GP-supervisor’s job. Rather than an end-point, they provide the basis for further work if they are to have any utility. In this final section, we reiterate how we are using the roles and flag other possibilities for applying them in work settings as well as further opportunities for research and evaluation.

As we stated earlier, the roles were identified as an integral part of a professional development curriculum that is being finalised for Australian GP-supervisors. The roles are central to its organisation and delivery, envisioned as threads that run through a spiral curriculum [Citation32]. As part of a curriculum, their value is primarily in helping to ensure that new GP-supervisors have the requisite knowledge and skills to be effective and efficient performers, but they may also have utility in the recruitment process, and the professional development of existing GP-supervisors.

As part of the process for recruiting new GP-supervisors, the roles could be used to create both an accurate job description and a realistic job preview. Fournies identifies that a major reason for employees not doing what organisations want them to do is that employees do not know what they are supposed to do [Citation33]. One step to solving this problem is to give people accurate job descriptions. As is detailed above, we choose organisational role theory as a means to better articulate what is expected of Australian GP-supervisors when performing the job.

Realistic job preview is an additional tool to provide potential candidates with a comprehensive and balanced description of the job so that they know what is expected of them [Citation34]. The job preview is realistic in the sense that it conveys the job’s challenges and derails any misperceptions that would-be GP-supervisors might have. If done well, realistic job previews help to stop the application process for those for whom the job is a poor fit, can help successful applicants better cope with the new job, and socialise people into it. A realistic job preview may also be of use to other stakeholders, such as GP-registrars, who could obtain a clear vision of what to expect from their supervisors.

For existing supervisors, the roles provide a series of benchmarks against which they can self-assess, to judge how well they are meeting the refreshed expectations. It would be relatively easy to develop a more purpose-built self-reflective tool to identify professional development needs, which could be used as a stand-alone process or incorporated into the process for re-accrediting GP-supervisors.

The practical application of the ten roles creates numerous possibilities for future research and evaluation. For example:

A curriculum must be evaluated to judge whether the requisite knowledge, skills and attitudes to competently perform the ten GP-supervisor roles have been taught and learnt.

If a realistic job preview, based on the ten roles, is introduced; then, what is its impact on the retention of GP-supervisors?

Are GP-supervisors who are judged to perform better on the roles rated as better supervisors by registrars?

Role theory itself provides a useful theoretical lens for investigating whether the roles have been effectively communicated by employing or accrediting organisations and whether they have been fully understood, accepted and agreed to by GP-supervisors. Unfortunately, and despite our member checking, role theory informs us of the possibility that some roles may not be accepted by some supervisors [Citation12].

Although the immediate audience for the roles was the curriculum development team, the medical educators who would deliver it and the GP-supervisors who will experience it, we believe that they are also likely to be relevant to medical educators who have a practical interest in delivering professional development in other primary care contexts and general practice contexts in other countries. We also believe that they are practically useful to clinical supervisors in these contexts. While we claim that the roles have a good fit to Australian general practice, we encourage these stakeholders to review the roles to judge whether they are transferable to their contexts. We expect that they will have more relevance than roles developed for other settings, such as clinical educators in tertiary care and university-based medical education.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the remaining members of the full research team from Eastern Victoria General Practice Training; Dr Elisabeth Wearne, Ms Lisa Vandenberg, Dr Caroline Johnson, Professor Neil Spike, and Dr Angelo D’Amore, and the members of the Expert Advisory Group; Professor David Snadden (University of British Columbia), Dr Rebecca Stewart (General Practice Training Queensland/RACGP), Dr Greg Gladman (Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine), Dr Gerard Connors (General Practice Supervisors Australia), Dr Danielle James (General Practice Training Queensland), Justine Mayer (Northern Territory General Practice Education), Dr Lawrie McArthur (James Cook University), Dr Catherine Pendrey (National Faculty GPs in Training), and Dr Taras Mikulin (Remote Vocational Training Scheme). is produced with courtesy of Simon Goodway.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- RACGP. Standards for general practice training. 3rd ed. East Melbourne: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2021.

- Wearne S, Dornan T, Teunissen PW, et al. General practitioners as supervisors in postgraduate clinical education: an integrative review. Med Educ. 2012;46(12):1161–1173. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04348.x.

- Brown J, Wearne S. Supervision in general practice settings. In: Nestel D, Reedy G, McKenna L, editors. Clinical education for the health professions. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2020;1–26.

- Harden RM, Crosby J. AMEE guide No 20: the good teacher is more than a lecturer – the twelve roles of the teacher. Med Teach. 2000;22(4):334.

- Morgan S. A balancing act - The role of the general practice trainer. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(12):19–22.

- Rees CE, Monrouxe LV. Theory in medical education research: how do we get there?. Med Educ. 2010;44(4):334–339.

- Oxford English Dictionary. “role, n.”. Oxford University Press. English. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/166971?rskey=BDxwGc&result=1&isAdvanced=false

- Ingham G, Willems J, Clement T, et al. Joint report for the national gp supervisor professional development curriculum project and the GP supervisor professional development framework project. Hawthorn: Eastern Victoria General Practice Training; 2021.

- Harden RM, Laidlaw JM. Essential skills for a medical teacher: an introduction to teaching and learning in medicine. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier; 2017.

- Hammersley M. Varieties of social research: a typology. Soc Res Method. 2000;3(3):221–229.

- Maxwell JA. A realist approach for qualitative research. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 2012.

- Katz D, Kahn RL. The social psychology of organisations. New York NY: Wiley; 1966.

- Biddle BJ. Recent development in role theory. Annu Rev Sociol. 1986;12:67–92.

- Wickham M, Parker M. Reconceptualising organisational role theory for contemporary organisational contexts. J Manage Psychol. 2007;22(5):440–464.

- Wolcott HF. Writing up qualitative research. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2001.

- Hammersley M. Methodology: who needs it? London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2011.

- Richardson L, St. Pierre EA. Writing: a method of inquiry. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications; 2005. p. 959–978.

- Dipboye RL, Smith CS, Howell WC. Understanding industrial and organizational psychology: an integrated approach. Orlando FL: Harcourt Brace College Publishers; 1994.

- Handy C. Understanding organizations. 4th ed. London: Penguin; 1993.

- D’Abate CP, Eddy ER, Tannenbaum SI. What’s in a name? A literature-based approach to understanding mentoring, coaching, and other constructs that describe developmental interactions. Hum Resour Dev Rev. 2003;2(4):360–384.

- Stoddard HA, Borges NJ. A typology of teaching roles and relationships for medical education. Med Teach. 2016;38:280–285.

- Stoddard H, Brownfield ED. Clinical-Educators as dual professionals: a contemporary reappraisal. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):921–924.

- Danish Health and Medicines Authority. The seven roles of physicians. Copenhagen: Danish Health and Medicines Authority (Sundhedsstyrelsen); 2014.

- Marks SR, MacDermid SM. Multiple roles and the self: a theory of role balance. J Marriage Family. 1996;58(May):417–432.

- Grzywacz JG, Carlson DS. Conceptualizing work-family balance: implications for research and practice. Adv Dev Human Res. 2007;9(4):455–471.

- Forster N. The analysis of company documentation. In: Cassell C, Symon G, editors. Qualitative methods in organizational research: a practical guide. London: Sage Publications; 1994. p. 147–166.

- GPEx. Supervisor manual 2018. Unley South Australia: GPEx; 2018.

- Loughran J. Developing a pedagogy of teacher education: understanding teaching and learning about teaching. Abingdon: Routledge; 2006.

- Yanow D. Neither rigorous nor objective?; Interrogating criteria for knowledge claims in interpretive science. In: Schwartz-Shea P, Yanow D, editors. Interpretation and method: empirical research methods and the interpretive turn. 2nd ed. Armonk NY: M. E. Sharp Inc; 2015. p. 97–119.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. An expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications; 1994.

- Schwartz-Shea P. Judging quality: evaluative criteria and epistemic communities. In: Schwartz-Shea P, Yanow D, editors. Interpretation and method: empirical research methods and the interpretive turn. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2015. p. 120–146.

- Harden RM, Stamper N. What is a spiral curriculum?. Med Teach. 1999;21(2):141–143.

- Fournies FF. Why employees don’t do what they’re supposed to do and what to do about it. Blue Ridge Summit PA: Liberty Hall Press; 1988.

- Larson SA, O’Nell SN, Sauer JK. What is this job all about? Using realistic job previews in the hiring process. In: Larson SA, Hewitt AS, editors. Staff recruitment, retention, training strategies for community human service organizations. Baltimore MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.; 2005. p. 47–74.

- Nikendei C, Ben-David MF, Mennin S, et al. Medical educators: how they define themselves - Results of an international web survey. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):715–723. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1073236.

- Reitz R, Simmons PD, Hodgson J, et al. Multiple role relationships in healthcare education. Families Systems & Health. 2013;31(1):96–107. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031862.

- The Bridging Project. Competencies comprising the role of doctor as educator. Canberra: Australian General Practice Training, VMA General Practice Training. Monash Univ Med Nurs Health Sci.

- Jackson D, Davison I, Adams R, et al. A systematic review of supervisory relationships in general practitioner training. Med Educ. 2019;53(9):874–885. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13897.

- Bourgeois-Law G, Regehr G, Teunissen PW, et al. Educator, judge, public defender: conflicting roles for remediators of practising physicians. Med Educ. 2020;54(12):1171–1179. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14285.

- Ullian JA, Bland CJ, Simpson DE. An alternative approach to defining the role of the clinical teacher. Acad Med. 1994;69(10):832–838.