ABSTRACT

General practitioners (GPs) make timely and accurate clinical decisions, often in the contexts of complexity and uncertainty. However, structured approaches to facilitate development of these complex decision-making skills remain largely unexplored. Here, the educational use of formative script concordance testing (SCT), a written assessment format originally designed to test clinical reasoning, is evaluated in this context through an in-depth qualitative exploration of the learning experiences of participating GP trainees. A ‘think-aloud’ approach to SCT is used, which requires question responses to be justified with a short clinical rationale. Eleven 1st-year GP trainees in Oxford (United Kingdom) completed the formative SCT activity, before taking part in individual semi-structured interviews. Data exploring their learning experiences was transcribed and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Thirty-seven codes were generated, and schematically organised into six sub-themes, that provide a descriptive summary of the data and insights into the practical educational utility of the SCT format. Three overarching themes were subsequently produced that relate specifically to aim of exploring in-depth the learning experiences of GP trainees to formative think-aloud SCT: 1) developing complex decision-making skills; 2) opportunity for self-evaluation and awareness; and 3) promoting community and professional identity. The development of complex clinical decision-making and reasoning skills is proposed to occur through guided reflection on performance, facilitated by the think-aloud approach to questioning. Together, this suggests a potential role for think-aloud SCT as a distinctive, structured learning activity to complement trainees’ professional development.

Introduction

General practitioners (GPs) are required to make timely and accurate clinical decisions, often in the challenging contexts of complexity and uncertainty [Citation1]. The intricate series of cognitive processes and skills involved, collectively referred to as ‘clinical reasoning’, allow GPs to become experts in assessing and managing undifferentiated symptoms, and identify serious pathology amongst an assortment of common conditions [Citation2,Citation3]. Indeed, clinical errors in primary care are more commonly associated with inappropriate reasoning than insufficient knowledge of the relevant topic [Citation4]. This illustrates the importance of GPs developing these contextualised skills, and their emphasis during postgraduate speciality training [Citation5,Citation6]. It also indicates a role for supplementing trainees’ workplace-based experiences with activities specifically designed to facilitate this learning through repeated practice, personalised feedback and self-reflection [Citation7,Citation8]. To date, the use of such structured approaches in GP training curricula remain limited. The aim of this study is to provide an evaluation of the novel use of a formative think-aloud SCT assessment in this context, through an exploration of the learning experiences and perspectives of UK GP trainees.

The script concordance test (SCT) is a written assessment that aligns its question structure with the principal steps of clinical reasoning [Citation9–11]. SCT first presents candidates with a brief clinical scenario that deliberately retains a degree of uncertainty. Individual questions propose a hypothesis for a related diagnostic, investigatory or management decision (‘If you were thinking of …’), before introducing a novel piece of data (‘and then you find …’). The candidate is then asked to evaluate the effect of this new information on the initial statement (‘this becomes … ’). Responses are given on a five-point scale ranging from −2 (e.g. very unlikely/useless), through 0 (neither more or less likely/useful) to +2 (very likely/useful) (.). Scoring is assigned based on responses to each question independently provided by a panel of expert clinicians (typically individuals fully qualified/certified in their speciality) [Citation12]. An example of an SCT question and scoring is provided in the supplementary information available online.

Figure 1. The principle steps of clinical reasoning in alignment with SCT question construction (adapted from Lubarsky et al., 2013) [Citation9].

![Figure 1. The principle steps of clinical reasoning in alignment with SCT question construction (adapted from Lubarsky et al., 2013) [Citation9].](/cms/asset/582d051c-cab2-4390-960d-c539f7357d97/tepc_a_2057240_f0001_oc.jpg)

Originally intended to summatively evaluate clinical reasoning skills, the suitability of SCT in this context has become the subject of debate [Citation11,Citation13–15]. Such limitations of SCT relate to the challenging nature of determining thresholds of competency for these intricate skills, and reliability and validity concerns raised by the use of a graded answer scale and the approach to scoring [Citation16–20]. Despite this, the unique features of SCT have the ability to engage learners in discussion and higher-order cognitive processing of their decision-making behaviours [Citation21–23]. As such, there is increasing acknowledgement of the educational value of SCT as a learning tool used in formative capacities. The deliberate introduction of ambiguity into scenarios and the use of a graded answer scale attempts to avoid a single ‘correct’ and multiple ‘incorrect’ responses to each question [Citation10]. This facilities SCT to function as a written assessment that more closely resembles the subtleties of real-life clinical practice and decision-making between a variety of justifiable options, whilst allowing broad sampling of topics, practical across cohorts and within a short timeframe [Citation9,Citation24]. Recently, the leaning opportunities provided by formative SCT has been shown to be enhanced by adopting a ‘think-aloud’ approach to questioning [Citation22,Citation25,Citation26]. Here, learners are required to justify their Likert scale responses with verbal or written clinical rationales, encouraging reflection on the deeper cognitive processes involved in decision-making in conditions of uncertainty [Citation22–28]. To date, the use of formative think-aloud SCT as a learning tool in postgraduate GP settings is yet to be evaluated. This is despite widespread acknowledgement of the relevance and importance of decision-making skills in the context of uncertainty by clinicians in primary care [Citation29].

The SCT assessment used in this study was delivered by the author to their peer cohort of 1st-year GP trainees enrolled in the Oxford GP training scheme. Access was granted to use a previously validated 145-question primary care SCT assessment, designed by the Department of General Practice, University of Liège [Citation30]. Following translation, 10 scenarios (30 questions) were selected to represent a range of topics across the Royal College of General Practitioners’ (RCGP) training Curriculum [Citation31]. To ensure the expert panels’ answers reflected up-to-date UK primary care practice, responses (including a brief corresponding think-aloud written rationale) were obtained from 13 UK GPs (6 female: 7 male, mean post-qualification experience 13.1 years, across 10 counties in England, Scotland and Wales). Trainees were individually sent an electronic copy of the SCT paper and asked to provide answers with accompanying justifications as an unsupervised, open-book written activity. Their numerical responses were marked according to the scoring approach previously described and returned alongside a copy of the ‘mark scheme’ including the GP panel justifications, and an overall pass mark for the paper (determined using a standard setting approach described by Fournier et al.) [Citation10]. The trainees’ written think-aloud responses were reviewed and considered during a subsequent remote educational session. In small peer groups, allocated scenarios were discussed in depth, including reasons for discrepancies in the expert panel/peer rationales, and techniques that could be used in practice to manage the clinical uncertainties raised. Finally, this was fed back to the whole group in a facilitator-led (GP Training Programme Director) closing debrief.

Methods

This study adopts a ‘big Q’ approach, i.e. utilises both a qualitative research paradigm and methodology, designed to investigate participants’ learning experiences to formative think-aloud SCT through the gathering of non-numerical data [Citation32,Citation33]. The subjectivity of the researcher and their position as an ‘insider’ (i.e. in the same GP training cohort) is therefore considered integral to the overall investigative process [Citation34,Citation35]. GP trainees who completed the SCT activity were invited to participate in the study via email. The study sample size was not specifically determined in advance to achieve ‘data saturation’, however is considered to have generated sufficient information to produce meaningful and practical findings [Citation36,Citation37].

Individual, audio-recorded interviews were conducted by the author remotely using online video conferencing software (Zoom TM). The use of interactive questioning provided a focused, but flexible and non-prescriptive framework to generate rich data relating to each participants’ experience [Citation38,Citation39]. Interviews were guided by a topic schedule, consisting of a series of open-ended questions to explore participants’ learning experiences (see supplementary information available online). The schedule was refined during two initial pilot interviews (included in the analysis), allowing data collection to adapt to emerging findings [Citation40]. Recordings (with corresponding interview notes) were anonymised, stored securely and transcribed verbatim by the author. To ensure accuracy, transcripts were returned to participants for comment and correction (none required) [Citation41].

Data were analysed using qualitative research software (NVivo TM), according to the six phases of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis [Citation34,Citation42,Citation43]. Familiarisation with the data was achieved during transcription and review of audio recordings. Data-driven coding was performed, with individual codes (consisting of phrases, sentences or paragraphs) considered as features in the data capable of conveying a shared underlying meaning when taken out of their original context [Citation36]. These were defined and referenced to facilitate consistency of coding across transcripts (see supplementary information available online). Codes were first schematically analysed into sub-themes to produce a descriptive summary of the data, and facilitate subsequent interpretation and reflexivity during theme generation [Citation42]. Peer debriefing (discussion with an experienced clinical education researcher, see acknowledgements) provided an external perspective through the analytic process [Citation41].

Results

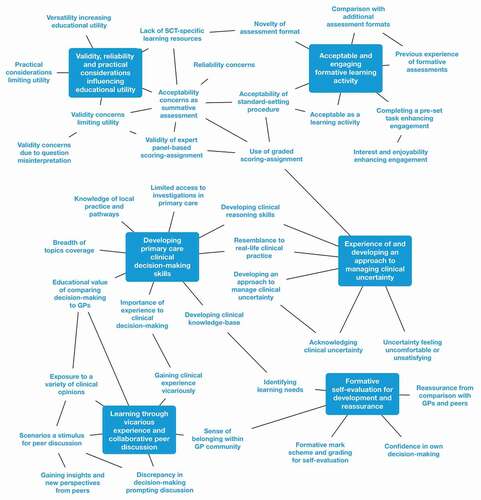

All 11 GP trainees who completed the educational activity consented to be interviewed as part of the study. Participants were in their first year of GP speciality training in Oxford, and had no prior experience of SCT as an assessment method (demographic details presented in ). Interviews (mean duration 41 minutes) yielded a wealth of qualitative data, from which 37 codes were derived. These were grouped into six sub-themes that provide a descriptive overview of the data, and provide practical insights into the educational utility of SCT as an assessment format (). From this, 3 overarching themes that specifically relate to the learning experiences and value of engaging with formative think-aloud SCT, from the perspective of GP trainees, were produced.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Theme 1 – developing complex decision-making skills

The educational value of formative SCT aligns closely with the development of complex primary care decision-making skills. Exposure to their application in the context of uncertainty and across a wide topic coverage, was valued by participants as more authentically reflecting real-life clinical practice (quotes 1–2, see ). The think-aloud approach enhanced the learning opportunities provided by SCT through a number of mechanisms. First, it actively engaged participants in the process of clinical reasoning (quote 3). Providing justifications for their question responses prompted trainees to acknowledge and reflect more deliberately on their underlying thought processing. The ability to then compare and gain feedback from the rationales provided by the expert panel (as well as peers during group discussion) was considered by trainees as being integral to the overall opportunity for learning (quotes 4–5).

Table 2. Participant quotations.

Theme 2 – opportunity for self-evaluation and awareness

Formative think-aloud SCT facilitated GP trainees to evaluate their own clinical performance, recognise relevant learning needs, and gain insights into behaviours and characteristics capable of influencing their professional practice. In turn, identifying areas for development prompted self-study, ‘mark scheme’ review and further discussion with peers (quote 6). Furthermore, alignment of their clinical reasoning with the GP panel (as well as peers) was capable of reassuring trainees about their development and progression through training. This was reinforced by receiving a pass mark, indicating a role for standard-setting in the formative assessment (quotes 7–8). The purposeful design of SCT to include clinical uncertainty was identified by trainees, and had the potential to be perceived unfavourably. Interestingly, despite this, trainees reflected on the value of being required to directly acknowledge the issue, contemplate their emotional response and consider strategies to managing it in future practice (quotes 9–10).

Theme 3 – promoting community and professional identity

The SCT activity encouraged trainees to consider their personal identity within, and an appreciation of belonging to, a wider GP community. The think-aloud approach provided a basis for trainees’ clinical thought-processes to be actively sought out, appreciated, and validated in relation to the opinions of others. Participants valued the insights and perspectives offered by their peers and the expert panel, and the opportunity for vicarious learning through exposure to their unique set of experiences and expertise (quotes 11–12). Proficiency in complex and contextual decision-making skills was also recognised by trainees as integral to the identity of a GP, and contributing to the provision of quality patient care. Engaging with, and learning from an activity intended to facilitate this development was perceived as contributing to a sense of legitimate progression through training (quote 13).

Discussion

This study provides the first in-depth qualitative exploration of GP trainees’ learning experiences to formative think-aloud SCT. In doing so, it highlights the potential educational value of its application as a structured activity in speciality training. By requiring the use of clinical reasoning to aid decision-making in the context of uncertainty, trainees are facilitated to develop skills widely recognised as integral to effective primary care clinical practice [Citation2,Citation43]. In addition to the themes outlined above, this study also provides primary care educators with an opportunity to gain insight into the format and innovative application of SCT. Its use as a formative tool in this context is supported by participants widely considering it to be an acceptable, engaging and versatile learning approach (quotes 14–15).

Furthermore, the ability of the SCT assessment design to create meaningful opportunities for learning is consistent with current theories and approaches utilised in postgraduate clinical education [Citation44]. The challenging question structure requires engagement with ‘higher-order’ cognitive processing, as described in the revised Bloom taxonomy [Citation45,Citation46]. Here, these skills are arranged into an overlapping hierarchical, yet recursive structure. By adopting a think-aloud approach, trainees are encouraged to move towards ‘evaluating’ their own decision-making by providing (and/or verbally discussing) their clinical justifications. Each individual SCT scenario is therefore capable of providing a concrete experience from which learning can be derived, and later refined by trainees through application in their clinical practice. This is proposed to occur through a process of guided reflection on performance, as described by Kolb’s model of ’experiential learning’ () [Citation47]. GP trainees consistently highlighted the perceived educational value of comparing their own thought-processing to that of the expert panel and their peers, and gaining feedback through the written think-aloud responses and opportunity for collaborative group discussion. Gibbs’ ‘reflective cycle’ expands on these principles by emphasising the influence of evaluating and analysing the emotional response to an event to generate learning [Citation48]. Here, think-aloud SCT was capable of prompting trainees to acknowledge their feelings around the complexity of decision-making in primary care, especially in relation to clinical ambiguity. Indeed, the issue of dealing with uncertainty in primary care is associated with negative influences on GP trainee wellbeing (e.g. clinician anxiety, concern about bad outcomes) and performance (e.g. reluctancy to disclose uncertainty) [Citation29]. Trainees were provided with an opportunity to recognise and understand their initial ‘gut reaction’ to uncertainty, an important aspect of managing this issue in practice [Citation8].

Figure 3. Kolb’s cycle of ‘experiential learning’ (1984) and think-aloud SCT [Citation47].

![Figure 3. Kolb’s cycle of ‘experiential learning’ (1984) and think-aloud SCT [Citation47].](/cms/asset/10d3a70f-c660-420f-b35e-257212451578/tepc_a_2057240_f0003_oc.jpg)

There are a few limitations of the study. First, it was designed to provide an in-depth evaluation of the learning experiences of a small cohort of participants, at a single stage of training and from the same locality. The findings of the study therefore inform the practical application of formative think-aloud SCT as a learning activity in a GP training curriculum, as opposed to relating to wider generalsibility. The potential for the author’s pre-existing relationship with participants to influence the views expressed is also acknowledged. Finally, the proposed learning opportunities provided by formative think-aloud SCT are derived from perceived self-development of clinical skills that are inherently difficult to measure. Further work would therefore required to assess how trainees may apply this learning to complex decision-making in their subsequent clinical practice.

Conclusion

This study evaluates the educational value of formative think-aloud SCT through an in-depth qualitative exploration of the perspectives of a cohort of UK GP trainees, and in doing so supports the ability of this approach to create rich and meaningful learning opportunities. Furthermore, it provides educators with practical insights into the application of SCT as a structured tool in postgraduate speciality training. Due to the complexity of developing clinical reasoning and contextualised decision-making skills, this is suggested to complement (as opposed to replace) existing workplace-based learning approaches. It is also hoped this study will act as a springboard to justify the further integration and evaluation of formative think-aloud SCT across additional primary care education settings.

Ethical Considerations

This study involved recruiting GP trainees as participants and implementing an educational activity, with associated ethical considerations. As such, approval was sought and obtained from the authors’ academic institution (The University of Edinburgh Medical Education Research Ethics Committee, ref: 2020/19), and the educational body responsible for the participants’ clinical training (Oxford GP vocational training school). Eligible participants were provided with written information outlining nature of the study and their involvement, alongside their right to withdraw, prior to voluntary recruitment.

Availability of data

Available from the author upon request.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (97.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr Derek Jones (Clinical Education Programme Director, University of Edinburgh) for his guidance and support as their MSc Clinical Education dissertation supervisor, and the reviewers for their valuable comments on the draft manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alam R, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Panagioti M, et al. Managing diagnostic uncertainty in primary care: a systematic critical review. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0650-0

- Atkinson K, Ajjawi R, Cooling N. Promoting clinical reasoning in general practice trainees: role of the clinical teacher. Clin Teach. 2011;8(3):176–180.

- Green C, Holden J. Diagnostic uncertainty in general practice. Eur J Gen Pract. 2003;9(1):13–15.

- Scott IA. Errors in clinical reasoning: causes and remedial strategies. BMJ. 2009;338(2):b1860–b1860.

- Danczak A, Lea A. What do you do when you don’t know what to do? GP associates in training (AiT) and their experiences of uncertainty. Educ Primary Care. 2014;25(6):321–326.

- Tanna S, Fyfe M, Kumar S. Learning through service: a qualitative study of a community-based placement in general practice. Educ Primary Care. 2020;31(5):305–310.

- Anders-Ericsson K. Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: a general overview. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):988–994.

- Gheihman G, Johnson M, Simpkin AL. Twelve tips for thriving in the face of clinical uncertainty. Med Teach. 2019;42(5):493–499.

- Lubarsky S, Dory V, Duggan P, et al. Script concordance testing: from theory to practice: AMEE GUIDE No. 75. Med Teach. 2013;35(3):184–193.

- Fournier JP, Demeester A, Charlin B. Script concordance tests: guidelines for construction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-8-18

- Charlin B, Leduc C, Brailovsky CA, et al. The diagnosis script questionnaire: a new tool to assess a specific dimension of clinical competence. Adv Health Sci Educ. 1998;3(1):51–58.

- Gagnon R, Charlin B, Coletti M, et al. Assessment in the context of uncertainty: how many members are needed on the panel of reference of a script concordance test? Med Educ. 2005;39(3):284–291.

- Custers EJ. The script concordance test: an adequate tool to assess clinical reasoning? Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(3):145–146.

- See K, Tan K, Lim T. The script concordance test for clinical reasoning: re-examining its utility and potential weakness. Med Educ. 2014;48(11):1069–1077.

- Lineberry M, Hornos E, Pleguezuelos E, et al. Experts’ responses in script concordance tests: a response process validity investigation. Med Educ. 2019;53(7):710–722.

- Eva K. What every teacher needs to know about clinical reasoning. Med Educ. 2005;39(1):98–106.

- Ahmadi S, Khoshkish S, Soltani-Arabshahi K, et al. Challenging script concordance test reference standard by evidence: do judgments by emergency medicine consultants agree with likelihood ratios? Int J Emerg Med. 2014;7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-014-0034-3

- Lineberry M, Kreiter C, Bordage G. Threats to validity in the use and interpretation of script concordance test scores. Med Educ. 2013;47(12):1175–1183.

- Lubarsky S, Dory V, Meterissian S, et al. Examining the effects of gaming and guessing on script concordance test scores. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(3):174–181.

- Gawad N, Wood T, Cowley L, et al. The cognitive process of test takers when using the script concordance test rating scale. Med Educ. 2020;54(4):337–347.

- Funk KA, Kolar C, Schweiss SK, et al. Experience with the script concordance test to develop clinical reasoning skills in pharmacy students. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9(6):1031–1041.

- Ottolini MC, Chua I, Campbell J, et al. Pediatric hospitalists’ performance and perceptions of script concordance testing for self-assessment. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(2):252–258.

- Deschênes M, Goudreau J. Script concordance testing to understand the hypothesis processes of undergraduate nursing students - multiple case study. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2021;11(6):73.

- Cooke S, Lemay J-F. Transforming medical assessment: integrating uncertainty into the evaluation of clinical reasoning in medical education. Acad Med. 2017;92(6):746–751.

- Power A, Lemay J-F, Cooke S. Justify your answer: the role of written think aloud in script concordance testing. Teach Learn Med. 2016;29(1):59–67.

- Deschênes M-F, Goudreau J, Fernandez N. Learning strategies used by undergraduate nursing students in the context of a digital educational strategy based on script concordance: a descriptive study. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;95:104607.

- Tedesco-Schneck M. Use of script concordance activity with the think-aloud approach to foster clinical reasoning in nursing students. Nurse Educ. 2018;44(5):275–277.

- Wan M, Tor E, Hudson J. Examining response process validity of script concordance testing: a think-aloud approach. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:127–135.

- Cooke G, Tapley A, Holliday E, et al. Responses to clinical uncertainty in Australian general practice trainees: a cross-sectional analysis. Med Educ. 2017;51(12):1277–1288.

- Subra J, Chicoulaa B, Stillmunkès A, et al. Reliability and validity of the script concordance test for postgraduate students of general practice. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017;23(1):209–214.

- Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). The RCGP curriculum: being a general practitioner. 2019. Available from: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/GP-training-and-exams/Curriculum/curriculum-being-a-gp-rcgp.ashx?la=en

- Ng S, Baker L, Cristancho S, Kennedy TJ, Lingard L.Qualitative research in medical education: methodologies and methods. In: Swanwick T, Forrest K, O'Brien BC, editors. Understanding medical education: evidence, theory and practice. London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2019. p. 427–441.

- Kidder LH, Fine M. Qualitative and quantitative methods: when stories converge. New Directions Program Eval. 1987;1987(35):57–75.

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all. What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2020;18(3):328–352.

- Hayfield N, Huxley C. Insider and outsider perspectives: reflections on researcher identities in research with lesbian and bisexual women. Qual Res Psychol. 2015;12(2):91–106.

- Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;13(2):201–216.

- Malterud K, Siersma V, Guassora A. Sample size in qualitative interview studies. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760.

- Hanson J, Balmer D, Giardino A. Qualitative research methods for medical educators. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(5):375–386.

- Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, et al. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J. 2008;204(6):291–295.

- Kallio H, Pietilä A, Johnson M, et al. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):2954–2965.

- Nowell L, Norris J, White D, et al. Thematic Analysis. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):160940691773384.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Dede C. Immersive interfaces for engagement and learning. Science. 2009;323(5910):66–69.

- Swanwick T, Forrest K, O’Brien BC. Understanding medical education: evidence, theory and practice. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley Blackwell; 2019.

- Bloom BS, Blyth WA, Krathwohl DR. Taxonomy of educational objectives. handbook I: cognitive domain. Br J Educ Stud. 1966;14(3):119

- Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman; 2001.

- Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice-Hall; 1984.

- Gibbs G. Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. London (UK): Further Education Unit at Oxford Polytechnic; 1988.