ABSTRACT

Disagreement exists within the UK and Ireland regarding how Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should be defined, and the relevance of international definitions. In this modified, online Delphi study, we presented the UK and Ireland experts in Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships with statements drawn from international definitions, published LIC literature, and the research team’s experience in this area and asked them to rate their level of agreement with these statements for inclusion in a bi-national consensus definition. We undertook three rounds of the study to try and elicit consensus, making adaptations to statement wording following rounds 1 and 2 to capture participants’ qualitative free text-comments, following the third and final round, nine statements were accepted by our panel, and constitute our proposed definition of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships within the UK and Ireland. This definitional statement corresponds with some international literature but offers important distinctions, which account for the unique context of healthcare (particularly primary care) within the UK and Ireland (for example, the lack of time-based criteria within the definition). This definition should allow UK and Irish researchers to communicate more clearly with one another regarding the benefits of LICs and longitudinal learning and offers cross-national collaborative opportunities in LIC design, delivery and evaluation.

Introduction

Though Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships (LICs) are an increasingly popular model of clinical education within the UK and Ireland, particularly within primary care [Citation1], there is a lack of a cross-nation consensus definition. In 2009, Norris et al., [Citation5] writing on behalf of the international Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships (CLIC), defined LICs internationally as involving three core features:

Student participation in patient care over time

Developing relationships with those patients’ clinicians

Meeting the majority of the year’s core clinical competencies through the experience

Given the openness of some of these criteria (e.g. how does one define ‘majority’ or decide when a relationship is sufficiently developed), this definition has produced different types of LICs. Worley et al. [Citation2] categorised these types into a typology, which includes: amalgamative clerkships (LIC-A), blended LICs (LIC-B) and comprehensive LICs (LIC-C), based on a repository of LIC-data from CLIC. Amalgamative clerkships involve less than 50% of the academic year (less than 20 weeks), cover two or more but fewer than 50% of a year’s disciplines, are treated as one of the many rotations in a rotation-based course, and occur in any of the last three years of a degree programme. In contrast, blended LICs occupy 50–89% of the academic year (20–32 weeks), cover all/the majority of disciplines, are linked to complementary external rotations, and usually are based in students’ penultimate year. Comprehensive LICs occupy over 90% of the academic year (above 32 weeks), cover all disciplines, may include brief discipline-specific immersive experiences, and are usually in students’ penultimate year.

Including a time-bound restriction within the typology definition of LICs means that many LICs in the UK and Ireland would be classified as LIC-As, or amalgamative clerkships, given that shorter clerkships are commonly employed within the UK and Ireland to better suit local context [Citation1,Citation3]. Worley et al. [Citation2] draw attention to the fact that LIC-As are clerkships that are LIC-like, as opposed to representing LICs in and of themselves.

Presently, within the UK, there is a lack of definitional clarity regarding what constitutes an LIC that leads to significant variation in institutional self-reports of LIC prevalence [Citation4]. It is unclear whether the definition proposed by CLIC is well suited to the UK and Irish context, given that, at the time this definition was developed, no UK or Irish LICs existed and the definition was created from programmes running in the US, Canada, Australia, and South Africa where healthcare provisions and systems differ widely [Citation5]. Most UK LICs are based solely or primarily within primary care [Citation4], though there are some emerging secondary care models modelled on the Harvard-Cambridge Integrated Clerkship [Citation6]. Primary care within the UK and Ireland, contexts which are largely similar, are well integrated as care settings in a way that differs from primary care services in, for example, the US [Citation7]. [Citation8] Primary care practitioners act as gatekeepers to secondary care services within the UK, meaning that most patients’ first point of contact with the healthcare service for an illness is within primary care, and primary care practitioners are involved in the ongoing management of patient chronic illness [Citation9]. Given that primary care offers an integrated structure based on patient continuity, we speculate that it may be that students can achieve the outcomes of an LIC within UK and Irish general practice in a shorter period than mandated by Worley et al’.s [Citation2] definitional typology. Further research is necessary to move the UK and Ireland towards a consensus definition of LICs that pays due heed to local context. This is not to say that CLIC’s international definition and typology is not useful, just that work is necessary to scrutinise its application within our national contexts.

Given all this, we conducted a modified Delphi study to explore how medical education leaders within UK and Irish institutions define ‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships’, to consider how the definition is variously applied, and to reach consensus on a definition that meets the nuances of local context.

Methods

We conducted a modified Delphi study to explore institutional LIC leaders’ perspectives and reach a consensus on a definition of LICs within the UK and Ireland. The Delphi technique is a widely used consensus method for medical education research, which uses multiple iterations of a questionnaire (or rounds) to reach agreement on a specific topic or focus (Humphrey-Murto et al. [Citation20]). Ontologically, Delphi studies assume the existence of an objective reality which, through consensus amongst a group of experts, can be known [Citation10].

Modified Delphi studies decide the number of rounds prior to commencement (usually 2–3 rounds) [Citation11]. From our discussion of resources, likely sample size, and the scope of our question, we decided to hold three rounds.

Sampling

We purposively sampled medical education leaders at medical schools within the UK (n = 33) and Ireland (n = 6). We recruited UK leaders through the GP Heads of Teaching network, advertising our call for study participants in the network newsletter. We chose to recruit using this network as a result of UK LICs being, in the main, based within primary care. Previous UK LIC research has recruited through this network with success [Citation1,Citation3]. Those with experience of LICs were asked to volunteer to take part in our Delphi study. We also asked participants to recruit via snowballing and forward the study opportunity on to colleagues who may be based in other care settings (e.g. secondary care).

Within Ireland, this network does not exist, and so institutional heads of teaching were identified from reviewing each institution’s website and emailing leaders individually using publicly available email addresses hosted on their institution’s website. We allowed participants to self-identify as an LIC expert in recognition that not everyone with experience of LICs across their careers (both practically, and within research) will have a current role in LIC delivery. Many who research LICs, for example, are independent of LIC education.

Questionnaire development

Delphi studies include six stages (Humphrey-Murto et al. 2017):

Identifying a research problem

Completing a literature review

Developing a questionnaire of statements

Conducting anonymous iterative mail or email questionnaire rounds

Providing individual and/or group feedback between rounds

Summarising findings

We developed the first questionnaire for round one using existing LIC literature (e.g. [Citation5] and [Citation2]to test the definitions within these papers), a recent survey/interview study conducted by two members of the research team (MB, RP) which enquired after LIC prevalence and structure within the UK during 2020 (for context-specific knowledge), and our experience as educators and researchers interested in longitudinal learning. The questionnaire (Appendix 1) included proposed definitional criteria as statements, a 7-point Likert scale to indicate the level of agreement and open text boxes for comments regarding necessary revisions, or additional statements. A 7-point Likert scale was chosen as it has been shown to be optimal in terms of reliability and discriminatory power whilst also being favoured by respondents due to its inclusion of a neutral option (Trevelyan et al. 2015). We also collected participant demographics (medical education role, institution). We hosted the questionnaire in Qualtrics. Round 2 and Round 3 of the questionnaire were developed in response to participant suggestions on wording and quantitative consensus on inclusion or exclusion of existing statements.

Data analysis

The Likert scales were analysed using descriptive statistics in SPSS for windows v 27. There is no agreement on what is meant by ‘consensus’ within Delphi studies [Citation12]. After discussion as a team and following a review of methods literature on the Delphi approach, we defined consensus on individual items as a median score of ≥ 6 (agreeing/strongly agreeing) or ≤ 2 (disagreeing/strongly disagreeing) with 75% or over of the expert panel assigning this score. Any statements that reached consensus in Round 1 or 2, were removed from the survey for subsequent rounds, and were included in the final definition. Percentage agreement, median score and interquartile range were calculated for each statement, as appropriate for Likert-type ordinal-level data (Trevelyan, 2015). Stability, or the consistency of individual participants’ responses between the rounds were checked using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. This is an important process to ensure that the results are reliable [Citation13]. Responses were deemed to be stable if there was no significant difference in individuals’ scores between the rounds (alpha was set at 0.05).

Qualitative feedback was collated following each round to identify recurring suggestions for rewording or additions using content analysis. Qualitative data was discussed as a team following round one and two, to decide whether an item should be reformulated or added, and how.

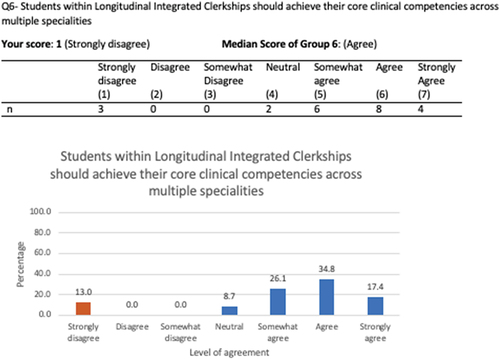

Following analysis of round 1 and 2 data, we provided individual feedback to our participants, with information regarding how their levels of agreement compared to the distribution of the entire sample. This was provided visually in bar charts so participants could easily see the distribution of responses to each question and see how they compared to the group. An example is provided in Appendix 2. We have clearly indicated any changes in wording, or additional statements. Participants were made aware that round 3 was the final round of the study and offered a final opportunity to accept or reject proposed statements.

Results

A total of 30 experts engaged with the survey, with 23 providing completed responses. Only data from the 23 who completed the survey were used in the analysis. Demographic information is provided in .

Table 1. Characteristics of Participants.

Round 1

The first-round questionnaire comprised 20 questions. Out of these twenty questions, two reached consensus. 95.6% agreed/strongly agreed to the statement ‘LICs should involve student participation in patient care over time’ and 100% agreed/strongly agreed to the statement ‘LICs should involve the development of relationships between clinicians and students.’

Several edits to wording were suggested across included statements – for example, comments in response to the statement ‘In LICs, students learn through managing their own patient caseload’ suggested the critical role of supervision, and so we revised this statement prior to Round 2 to read ‘In LICs, students learn through supervised responsibility for their own patient caseload’. The statements ‘LICs should include learning across all specialities taught within the year of study they are situated”’ and ‘LICs should be mandatory placements”’ were added following participant suggestions.

Full results from Round 1 are presented in .

Table 2. Summary of results from Round 1.

Round 2

Of the 23 participants responding in Round 1, 19 responded in Round 2. Due to statements being removed either through reaching consensus, revised statements making existing statements redundant due to similarity, and additional participant suggested statements included, the Round 2 questionnaire consisted of 19 questions. In this round, a further three statements reached consensus, with 78.9% of respondents agreeing/strongly agreeing to the statements ‘In LICs, students learn through having supervised responsibility of their own patient caseload’, ‘In LICs students should follow their patients across primary, secondary, and other care settings’, and ‘LICs involve the development of collaborative relationships between student peers’. The statement that ‘LICs should have a minimum duration of three months’ had the highest level of disagreement (66.7%) with a higher level of agreement for a longer minimum duration (e.g. 6–9 months). Free-text comments suggested division in opinion regarding the utility of time-based restrictions. Some strongly felt that time was critical in realising the educational benefits of LICs (‘I think 6 months is the minimum duration for the educational benefits of LICs to be realised’), whilst others disagreed, suggesting that the context of healthcare within the UK and Ireland was such that benefits could be achieved in a time shorter than three months (‘Not really helpful or practical in this country to define LIC like this – there is an issue with the term LIC as defined in America and how it applies to a different healthcare system in a geographically completely different country’), particularly when focussed on primary care (‘In the UK I believe primary is an ideal setting for a LIC due to the breadth of caseload and the way it is set up to support continuity elements critical to a LIC’). However, despite the disagreement evident within the free-text comments within Round 2, no statements reached consensus through disagreement.

The wording of five statements was edited in response to participant suggestions. For example, within ‘Students within LICs should achieve their core clinical competencies across multiple specialities’, the term ‘specialities’ was variably interpreted (some participants took this to mean topics within medicine (e.g. cardiology and paediatrics), while some interpreted this to mean placement in multiple care settings (e.g. general practice, secondary care specialities). We changed ‘specialities’ to ‘areas’ to reflect our intended meaning that student learning should span multiple topics. Stability of participants' statements between Round 1 and Round 2 was determined by Wilcoxon matched-pair signed rank tests, and are presented alongside the summary of results in . For most statements, participants’ answers were consistent between the two rounds, although two statements failed to reach stability.

Table 3. Summary of results for Round 2.

Round 3

In Round 3, 17 participants completed the questionnaire, which comprised of 15 questions. A further four statements reached consensus in this round. 82.5% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statements ‘Students within LICs should achieve their core clinical competencies across multiple areas of medicine’, and ‘Students within LICs should where practically possible, meet the majority of the year’s core clinical competencies through the clerkship’. 76.5% strongly agreed/agreed that ‘Students in LICs should ideally have some patients who have presentations spanning two or more specialities’. 100% agreed with the statement that ‘LICs should offer students the opportunity for multiple contacts (3 or more) with their patients.’ The three statements did not demonstrate stability between Rounds 2 and 3.

The results for Round 3 are presented in .

Table 4. Summary of results from Round 3.

The nine statements achieving consensus following three rounds of review by our experts and, therefore, constituting the agreed definition of LICs within the UK and Ireland, are listed in .

Discussion

Our definition aligns with Norris et al.’s [Citation5], three statement international definition of what constitutes a Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship (LICs involve student participation in patient care over time; LIC students develop relationships with their patients’ clinicians; and LIC students meet the majority of the year’s core clinical competencies through the experience). These definitional statements are echoed in statements 1, 2, and 8 of our definition, respectively. It is important to note that statement 8 is more tentative than within Norris et al.’s original definition – we have added ‘where practically possible’ which likely represents the diversity of LICs within the UK and Ireland in terms of clerkship structure and length [Citation3].

Regarding Worley’s et al.'s [Citation2], international typology, our definition highlights important contextual differences. Whilst it was not our aim to produce a typology, disagreement was expressed by our participants in relation to time-bound definitional criteria, and no criteria specifying the necessary minimum length of an LIC qualified as part of our final definition. Free-text comments suggested that many experts within the UK and Ireland believed that where LICs are based within primary care, as a result of breadth of caseload and continuity, associated benefits can be achieved in shorter durations of time than the criteria Worley et al. note is necessary for classification as an LIC (more than 50% of the academic year, or more than 20 weeks). In lieu of a time-based criterion, our definition includes instead guidance on the number of repeat contacts (3) with a patient likely necessary to begin to establish relational benefits. In addition, our definition focusses on qualitative criteria, which could be assessed in programme evaluations and student examination performance (e.g. the development of relationships with clinicians, participation in patient care, responsibility, patient follow-up, achieving core clinical competencies). These definitional features are unified by the organising principle of continuity – seamless learner experience with few abrupt changes [Citation14] that leads to relationship development, trust, and belonging [Citation15].

In addition to the above, our definition includes new areas of focus not captured by existing definitions. The importance of collaborative relationships with peers, supervised responsibility, and following the patient journey across care settings are noted as important within the wider LIC literature (e.g. [Citation16–18] but are not formalised within existing definitions. Recent research on identity development within LICs notes that there is a unique benefit within the UK and Ireland (where primary and secondary care exist as separate paradigms (Johnson and Bennett, [Citation8])) to crossing care settings with patients [Citation17]. Previous UK work has noted that medical students want to be placed with friends, which can act as a barrier to immersion in LIC patient communities [Citation7] and has highlighted that peer camaraderie (facilitating friendships, and opportunities for collaborative working) should be considered when designing and evaluating UK LICs [Citation19]. The importance of crossing care settings and peer relationships is not only supported by our definition but appears to be of particular relevance within our bi-national context. These are important design considerations for UK and Irish LICs based either in primary or secondary care.

Though we achieved consensus on nine statements for inclusion in our final definition, there were statements within our rounds on contemporary areas of disagreement within the LIC literature where consensus was not achieved. Notably, disagreement amongst the participants surveyed existed on whether LICs were best suited for a particular care setting, the year in which LICs should run (the [Citation2]typology states that LICs should usually run in the penultimate year of medical school but no consensus existed amongst our participants), whether LICs should be mandatory or voluntary, and whether LICs can run in parallel to block rotations. These questions represent possible directions for future, empirical research.

Although this Delphi study was conducted with the UK and Irish context in mind, the findings have international applicability. We would suggest that, particularly where there is a robust primary care infrastructure, educators should consider using primary care as fertile ground within which to situate a LIC, supporting some of the key definitional criteria we have highlighted, namely continuity with repeated contacts with a patient caseload, ongoing clinical supervision, managing multiple specialities, and providing students with space to navigate and bridge across primary and secondary care systems.

Limitations

We asked participants to self-identify as LIC experts, to recognise that not all with significant knowledge of LICs would hold a formal educational role – this risks a variation of experiences within our panel sample. We have collated these experiences within our demographic data for transparency. Within the UK, we recruited experts using the primary care Heads of Teaching (HoTs) network, which risks over-representation of primary care experiences and preferences in our sample though previous UK LIC research has recruited using this network [Citation1,Citation3], and existing evidence suggests that LICs are most commonly hosted within UK primary care [Citation3]. Although we measured stability, this was not used as a criterion for selecting statements for our final definition. Although not routinely included, some previous research suggests that stability measures should be used as an additional requirement for Delphi selection [Citation12]. Some statements reached consensus but not stability between rounds – future research might focus on establishing stability for this definition.

Conclusion

We set out to explore whether and how the international definitions of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships as proposed by [Citation2] and [Citation5] apply to a UK and Irish context through exploring consensus amongst a group of organisational leaders in teaching with experience and expertise in relation to LICs. Though our experts agreed upon statements which align with the international definition of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships (most notably in reference to involvement in patient care, developing relationships with supervisors and meeting most of the academic year’s core clinical competencies), they note important differences in relation to existing international typologies (most notable is a lack of time-based restriction within our definition). Furthermore, the definitional statement this Delphi process generated provides new qualitative criteria which capture areas of importance within a UK and Irish context (such as the development of collaborative relationships between student peers, learning through supervised responsibility of one’s own patient caseload, and following patients across primary/secondary/other care settings). We recommend that those interested in LICs within the UK consider how their programme relates to this consensus definition and use this to scaffold discussions and decisions regarding LIC design and evaluation. This work demonstrates the importance of situating international work within local contexts – it would be useful for future research in other countries with unique healthcare contexts to consider how international LIC definitions apply (or not) to their setting. Formalising these considerations in the academic literature provides a useful audit trail for differences in definitional interpretation between contexts, which facilitates international working despite contextual differences.

We hope this definitional statement will act as a useful guide in future discussions of what constitutes an LIC within the UK and Ireland and inspire similar work across varied international contexts. Perhaps most importantly, we hope that this rich definitional statement will encourage researchers to explore how various models demonstrate the achievement of these core characteristics to enable sharing of good practice and collaboration across institutions.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the experts who participated in this study and shared their experiences of LICs within UK and Irish practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brown M, Parekh R, Anderson K, et al. ‘It was the worst possible timing’: the response of UK longitudinal integrated clerkships to Covid-19. Educ Primary Care. 2022;33(5):288–295.

- Worley P, Couper I, Strasser R, et al. A typology of longitudinal integrated clerkships. Med Educ. 2016;50(9):922–932. DOI:10.1111/medu.13084

- McKeown A, Mollaney J, Ahuja N, et al. UK longitudinal integrated clerkships: where are we now? Educ Prim Care. 2018;30(5):1–5. DOI:10.1080/14739879.2019.1653228

- McKeown A, Parekh R. Longitudinal integrated clerkships in the community. Educ Primary Care. 2017;28(3):185–187.

- Norris TE, Schaad DC, DeWitt D, et al. Longitudinal integrated clerkships for medical students: an innovation adopted by medical schools in Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United States. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):902–907.

- Bansal A, Singh D, Thompson J, et al. Developing medical students’ broad clinical diagnostic reasoning through GP-facilitated teaching in hospital placements. Advances in Medical Education and Practice. 2020;11:379–388.

- Harding A. ‘A rose by any other name; longitudinal (integrated) placements in the UK and Europe. Educ Primary Care. 2019;30(5):317–318.

- Johnston JL, Bennett D. Lost in translation? Paradigm conflict at the primary–secondary care interface. Med Educ. 2019;53(1):56–63.

- Dixon J, Holland P, Mays N. Primary care: core values developing primary care: gatekeeping, commissioning, and managed care. BMJ. 1998;317(7151):125–128.

- Guzys D, Dickson-Swift V, Kenny A, et al. Gadamerian philosophical hermeneutics as a useful methodological framework for the Delphi technique. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2015;10(1):26291.

- Nasa P, Jain R, Juneja D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: how to decide its appropriateness. World J Methodol. 2021;11(4):116.

- Von der Gracht HA. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol Forecasting Social Change. 2012;79(8):1525–1536.

- Trevelyan EG, Robinson N. Delphi methodology in health research: how to do it? Eur J Integr Med. 2015;7(4):423–428.

- Ellaway RH, Graves L, Cummings BA. Dimensions of integration, continuity and longitudinality in clinical clerkships. Med Educ. 2016;50(9):912–921.

- Brown ME, Whybrow P, Kirwan G, et al. Professional identity formation within longitudinal integrated clerkships: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2021b;55(8):912–924.

- Birden H, Barker J, Wilson I. Effectiveness of a rural integrated clerkship in preparing medical students for internship. Med Teach. 2016;38(9):946–956.

- Brown ME, Ard C, Adams J, et al. Medical student identity construction within longitudinal integrated clerkships: an international, longitudinal qualitative study. Acad Med. 2022b;97:10–1097.

- Van Schalkwyk S, Bezuidenhout J, De Villiers M. Understanding rural clinical learning spaces: being and becoming a doctor. Med Teach. 2014;37(6):589–594.

- Brown ME, Crampton PE, Anderson K, et al. Not all who wander are lost: evaluation of the Hull York medical school longitudinal integrated clerkship. Educ Primary Care. 2021;32(3):140–148.

- Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Wood TJ, et al. The use of the Delphi and other consensus group methods in medical education research: a review. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1491-8.

Appendix 1:

Round 1 questionnaire

Towards a contextual definition of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships within the UK and Ireland: A Delphi study.

Thank you for agreeing to participate in this study as an expert panellist. We would first like to collect some demographic data from you. All demographic questions are voluntary, please feel free to leave any questions blank that you do not wish to answer. Demographic data will never be used to identify individual responses, but will be used to ensure our panel represent a variety of perspectives.

Which of the following best describes your role in medical education?

LIC course lead

LIC course faculty

Clinician involved in teaching

Educational researcher

Which higher education institution are you affiliated with?

Does your institution host a placement branded or described as a ‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship’? Y/N

Have you been involved with LICs in any other roles in your current or another institution? Y/N

You will now be presented with a series of statements related to LICs which have been collected from academic literature and expert discourse. We believe these may be important characteristics for LICs in the UK. You will be asked to rate your agreement with each of these statements.

You will also be provided with free text boxes to justify your response and suggest edits or removal of any statements we provide.

Later in the questionnaire, you will have the chance to add any statements you feel we have missed.

Students’ Role

In this section of the survey, we are interested in your opinion on what students’ role within Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships in the UK and Ireland should be.

1. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should involve student participation in patient care over time’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

2. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘In Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships, students learn through managing their own patient caseload’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

3. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘In Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships, students should follow their patients across primary, secondary, and other care settings’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

4. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should be based in one care setting, e.g. primary care or secondary care’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

5. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should be based in primary care’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

6. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Students within Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should achieve their core clinical competencies across multiple specialities’.

Core clinical competencies include aspects of practice expected to be successfully performed by medical students at a particular level, e.g. gathers appropriate information from a patient to formulate differential diagnoses; assesses and generates management plans; works effectively as a member of a team.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

7. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Students within Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should achieve their clinical competencies across multiple specialities simultaneously’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

8. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Students within Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should meet the majority of the year’s core clinical competencies through the clerkship’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

9. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Students in Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should have patients in their caseload who have medical presentations/backgrounds spanning two or more specialities. e.g. A pregnant woman with depression, or an elderly man who has a history of alcohol dependency and experiences a heart attack’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

10. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Students in Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should cover the majority or all of the year’s specialities through the clerkship’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

11. Please rate your level of agreement with the following: ‘The minimum percentage of the year’s specialities students within Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should cover is…’

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

Student relationships

In this section of the survey, we are interested in your opinion on the relationships students might develop during Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships.

12. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships involve the development of collaborative relationships between student peers’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

13. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should involve the development of relationships between clinicians and students’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

14. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should require that students have multiple contacts (3 or more contacts) with their patients during the placement’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

Timing

In this section of the survey, we are interested in a more detailed view on your opinion of the structure of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships in the UK and Ireland.

15. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should be a whole educational experience’.

Whole educational experiences are the only curriculum students engage in for the duration they run. e.g. a 6 month LIC would be 5 days/week for 6 months.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

16. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships can run in parallel to traditional placements’.

By this we mean that, in a 6 month Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship, students might spend one day a week in their Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship for 6 months, with the rest of the time spent in traditional rotational placements.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

17. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘UK and Ireland Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should have a minimum duration of … ’

18. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should be placements for senior medical students only (students in their penultimate or final year)’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

19. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should be placements for medical students in all years’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

20. Please rate your level of agreement with the following:

‘Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships should be voluntary placements’.

If you would like to provide additional justification for your response, or reword/remove this statement, please expand below.

Thank you for rating and responding to the above statements.

If there is anything you believe is important that we have not covered, please describe this below.

We are also interested in hearing about anything special or different you’re doing in any Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships you’re involved with.

Appendix 2:

Example of feedback provided to a participant at the start of Round 2 (please note, this is a fictional example to protect anonymity)