ABSTRACT

Introduction

Effective communication is essential for patient-centred relationships. Although medical graduates acquire communication skills during undergraduate training, these have been shown to be inadequate in early practice. Both students’ and patients’ perspectives are required to improve readiness for the workplace, patient satisfaction, and health outcomes. Our research question was: to what extent are medical students prepared with patient-centred communication skills in primary care settings?

Methods

A qualitative descriptive research study using in-depth semi-structured interviews was conducted with Year 3 medical students and patients to study their experiences at a primary care clinic, over two weeks. Data were transcribed verbatim and analysed using Braun and Clark’s thematic analysis. Both students’ and patients’ views on communication skills were obtained.

Results

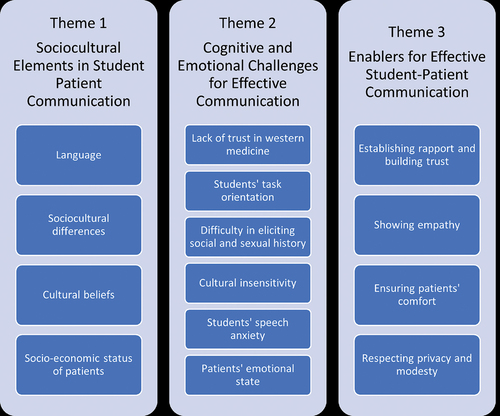

Three themes were established based on student-patient communication in primary care settings: socio-cultural elements in student-patient communication; cognitive and emotional challenges for effective communication; and enablers for effective student-patient communication. The themes and sub-themes describe both students and patients valuing each other as individuals with socio-cultural beliefs and needs.

Conclusion

The findings can be used to structure new approaches to communication skills education that is patient-centred, culturally sensitive, and informed by patients. Communication skills training should encourage students to prioritise and reflect more on patient perspectives while educators should engage patients to inform and assess the outcomes.

Introduction

Communication skills training in undergraduate medicine is fundamental for information gathering, patient education, counselling, healthcare team interactions, and establishing the doctor-patient relationship. Although medical graduates learn basic communication skills during undergraduate training, the literature has shown that these skills can be inadequate for their professional careers as doctors [Citation1–3]. Junior doctors face challenges in communication skills and patients report poor attitudes, lack of verbal and non-verbal communication skills, and inadequate information as sources of communication errors [Citation1,Citation3–9]. Consequently, cultural beliefs have been shown to influence the way practising doctors communicate with their patients [Citation5,Citation6,Citation10–12].

Evolution of doctor-patient communication

The doctor-patient relationship has evolved tremendously in the last five decades. Before the 1970s, the doctor-patient relationship was predominantly paternalistic where the patient assumed the ‘sick role’ in society, and the physician who ‘knew best’ became ‘an agent of social control’ and used his skills to decide on the treatment the patient received [Citation6]. This resulted in an asymmetrical power imbalance between the doctor and patient in the relationship. However, in recent decades, patient’s perspectives have been prioritised with a more autonomous patient-centred role [Citation13], cognisance of the ‘therapeutic effect’ of the doctor-patient relationship [Citation14], and changes in the way physicians perceive themselves [Citation15]. Changes in the doctor-patient relationship were attributed to the acknowledgement of patients’ rights and ethical issues brought about by technological advances in medicine, as well as the impact of economic and healthcare policies [Citation16]. The desired communication skills of general practitioners not only led to patient satisfaction but to greater job satisfaction for physicians [Citation17]. The ‘patient-centred clinical method’ appropriate for family medicine was conceptualised, where after explaining the patient’s illness, the doctor encouraged the patient to express his/her expectations, feelings, and fears [Citation18]. In the 1990s, there was a rise in malpractice claims [Citation19] and the doctor-patient relationship evolved into a more participatory, patient-centred partnership-style [Citation5,Citation12]. Subsequently, intercultural communication and patient education became essential components in the communication skills training of doctors [Citation20–25]. What has now become of utmost importance is to treat the ‘patient’ instead of the ‘disease’, and for the doctor to counsel the patient about the uncertainties and limitations of interventions and obtain informed consent before treatment [Citation26]. This remains the predominant model in clinical practice today.

In the global south, hierarchical respect for authority, coupled with strong family and communal ties, as well as heavy patient loads, have contributed to the culturally unique model of paternalistic communication [Citation4–7,Citation27,Citation28]. Nevertheless, medical educationalists in the global south or non-western countries began to see the need for a partnership style in doctor-patient communication with a more culturally sensitive patient-centred communication model, tailored to the local context [Citation4–7,Citation27,Citation28]. This need was driven by literature that showed patient-centredness repeatedly emerging as the common thread linking all aspects of communication skills leading to improved patient satisfaction and desired health outcomes [Citation19,Citation29–31].

Communication skills and patient-centred care in the primary care setting

Primary care is a powerful learning environment because it offers a unique socio-cultural and developmental learning space for students. In primary care, students are often confronted by the varying views of patients and their families on health and illness, requiring the need to adopt a biopsycho-sociocultural approach for increased patient-centredness [Citation32]. The context of primary care where many patients come for longitudinal follow up, presents a less hectic environment for the health professional, and is an important setting where students can learn and nurture their communication skills. Longitudinal integrated clinical placements (LICs) in primary care have been shown to inculcate patient-centredness [Citation9,Citation33], where continuity of care, triggers meaningful student-patient relationships, and the learning of appropriate communication skills. Compared to the hospital environment, patients in primary care are available to be approached, and students can interact and communicate at length with them to understand them beyond their ailments as whole persons [Citation34].

Owing to globalisation, doctors in primary care encounter more culturally diverse patients [Citation35]. To ensure safe and quality healthcare for all patients, primary care doctors need to understand how each patient’s socio-cultural and economic background affects their health beliefs, behaviours, values, and attitudes [Citation36]. This has underscored the need for doctors to be cognisant of their own communication skills and its impact on patient perspectives and patient-centred care [Citation29,Citation37–39]. This is an additional reason why the primary setting is suitable for learning patient-centred communication skills.

Given the importance of communication skills in the evolving doctor-patient relationship and importance of primary care in learning these skills, this study is guided by the following research question: to what extent are medical students prepared with patient-centred communication skills in primary care settings? The question aims to identify challenges and solutions that will be able to close the gap in preparing medical students with patient-centred communication skills and improve their readiness for the workplace. A differentiating feature of this study is that both patients and medical students’ voices were sought, aligned and analysed.

Methods

Study design

The study employed a qualitative descriptive research design to explore and understand [Citation40] the desired patient-centred communication skills required of medical students in primary care settings.

Study context and sampling

The study was conducted in the outpatient department of a Government Primary Care Clinic which serves as a teaching facility for students at the International Medical University (IMU) in Malaysia. The medical programme at IMU is a five-year undergraduate medical programme with two and a half years in medical sciences and another two and a half years in clinical sciences. The students begin their formal clinical rotation in Year three. Participants were recruited through purposive sampling with the following inclusion criteria: both must be Malaysian with voluntary participation and gave consent prior to the interview. The number of participants was guided by data saturation. Both students and patients were interviewed separately following student-patient medical consultations.

Data collection

The research team was the primary instrument of data collection, and analysis [Citation41]. A semi-structured interview protocol was developed by research team members after extensively reviewing existing literature on communication skills. It consisted of semi-structured questions both for students and patients and helped the researchers remain flexible by adapting questions and elaborating on ideas to help generate rich data. Before the interview, written consent was obtained from the participants. The interviews were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim manually.

Data analysis

Transcriptions were coded and analysed by the research team using the thematic analysis method of Braun and Clark [Citation42] framework of thematic analysis. In Step 1 – familiarisation of the data, the data from the transcription was repeatedly read by two members to familiarise with the transcript and identify codes. Samples of codes from transcription data are shown in Appendix 1. In Step 2 – identifying initial codes, all members worked on the coding process starting from initial codes generated on culture, communication behaviour and doctor-patient relationship. In Step 3 – searching for themes, the subsequent coding process involved examining the identified codes and narrowing it into more specific codes. The codes identified in Step 1 and Step 2 were further reviewed by the members and led to emergence of preliminary themes such as ‘culture’, ‘language’, ‘health anxiety’, ‘performing the task versus patient’s expectation’, ‘patient as a “teacher”’, ‘experiential learning’, ‘reflection’, ‘doctor-patient relationship’, and ‘patient as a “person”’. In Step 4 – reviewing themes, the preliminary themes identified through data coding that represented the elements in student-patient rapport were reviewed and refined. In Step 5 – defining and naming themes, a total of three themes were defined and established namely ‘Socio-cultural elements in student-patient communication’, ‘Cognitive and emotional challenges for effective communication’ and ‘Enablers of effective student-patient communication’. Finally in Step 6 – producing the report, each team member wrote the results based on the established themes. During this entire process, we looked at students’ and patients’ views to further understand the two perspectives.

Rigour

To ensure qualitative rigour and credibility of the results, two methods to enhance trustworthiness were employed. Firstly, the study employed investigator triangulation to establish credibility. Two members initially conducted the familiarisation of data and identification of initial codes and initial theme. Then all four members collectively reviewed the codes, themes and re-define the themes where relevant to generate final themes. Secondly, member-checking was carried out to obtain participants’ feedback on the interview transcripts and summary of codes to verify accuracy with their experiences.

Researcher reflexivity

In the study, two members of the research team were engaged in face-to-face interviews with participants. As interactions with participants might be influenced by the researchers’ professional background, experiences, and prior assumptions, careful consideration was given to put aside the assumptions and judgements during the interview and data analysis. Throughout the course of the research, the main author kept a reflexive diary in a form of an e-logbook which was cross-checked by team members to assess prior assumptions and beliefs. All members consciously critiqued, appraised, and evaluated how subjectivity and contexts could influence the research process. Regular meetings were held between authors to discuss the progress of the research including analysis of data.

Results

Eight Year three early-phase clinical students in the Family Medicine rotation and eight patients attending primary care clinics during the students’ rotation participated in the study. Demographically, students recruited into the study belonged to the three main ethnicities in Malaysia: Malay, Chinese, and Indian. Two were male and the remaining six were female. Ages ranged 22 to 27 years. Patients recruited equally belonged to three main ethnicities: Malay, Chinese, and Indian, and were from different socio-economic backgrounds. Two patients were male and the remaining six were female. Their ages ranged between 56 and 79 years and they were a retired machine operator, a retired draughtsman, a retired accounts clerk, a hawker, a cashier in a petrol station, a businesswoman, a retired nurse, and a housewife. Each interview lasted between 20 to 30 minutes.

Three themes were established based on medical student-patient communication skills in primary care settings as shown in . The three themes were socio-cultural elements in student-patient communication, cognitive and emotional challenges for effective communication, and enablers for effective student-patient communication.

Theme 1: socio-cultural elements in student-patient communication

Language and socio-cultural differences create barriers between patients and health professionals and can pose challenges to achieving patient satisfaction and successful clinical outcomes. In the interview, students mentioned difficulty and discomfort when they were not communicating using their own mother tongue.

“I think it’s the language barrier, if they don’t understand what we are saying, and we don’t ask them proper questions”. -S7.

Cultural beliefs of an individual were identified as vital for communication. Both students and patients perceived that the meaning of each conversation was different due to different cultural beliefs, stereotyping, and preconceived ideas. This includes patients’ beliefs in seeking western medicine for some conditions and traditional medicine for others.

“Culture plays an important role when we are talking to patients, because sometimes when we mean something else, they might understand it as something else”-S1.

Both students and patients highlighted that the socio-economic status of patients, including the level of education, job, social standing, and upbringing, influenced communication and caused distress to patients.

‘Basically, your surrounding factors affect who you are as a person, your nationality, your education, family background, and past experiences’-S8.

‘Some doctors in the private speak negatively, like they told me once in hospital if you came any later your head would have burst. At that time, I was so upset and I thought to myself, doctors should not speak like that’-P5.

Theme 2: cognitive and emotional challenges for effective communication

Challenges for effective student-patient communication include lack of trust in western medicine, students’ task orientation, difficulty in eliciting a social and sexual history, cultural insensitivity, students’ speech anxiety, and patients’ emotional state. Students perceived that some patients were still strongly holding on to their beliefs in traditional and ancestorial medicine. This caused the patients to have a lack of trust in western or modern medicine and posed a challenge for the doctor to communicate well and provide treatment for them. Students described it as sometimes difficult to elicit from patients whether they were already taking traditional medicine.

‘You can roughly tell how the average patients react to Western medicine. Some will still stick to taking traditional medicine. So doctor will try to advise them to drop the belief’-S6.

During clinical training, students encountered challenges in communicating as they were too focused on carrying out the required task and completing the checklist, rather than paying attention to what the patient is trying to convey to them. Similarly, patients commented that students were more focused on their task and solving a problem instead of focusing on them and their needs.

‘They never concentrate, and only take care of their problem. They forget to ask me things’-P1.

Students shared that a patient’s emotional state, including their anxiety, fears, and expectations of doctors, can also pose a challenge to good doctor-patient communication.

‘If the patient comes in with different emotion, then this is another factor that will cause trouble’-S6.

Theme 3: enablers for effective student-patient communication

Effective student-patient communication skills can be enabled by establishing rapport and building trust, showing empathy, ensuring patients’ comfort and both respecting privacy and modesty. This perspective was echoed by both students and patients.

‘They stroke my hand and I like it when they explain to me before they do anything’-P5.

Students added that early experiential learning helped them become more engaged with their studies, strengthened skills acquisition, and made learning more relevant. Students highlighted the importance of having good role models in the learning environment to help them learn communication skills and were aware of the influence of both positive and negative behaviours or emotions of the surrounding health professionals with their patients.

‘In clinic setting, the patients came to the clinic to consult on their conditions, so they are willing to talk to you’-S4

‘Sometimes, the patient just sits there, and the doctor will just read through the BHT (bed head ticket) and say, “Ok! I’ll pass you the medication and send you back home!”’-S2.

Discussion

Our study highlighted that socio-cultural differences can affect communication, the doctor-patient relationship, and ultimately patient outcomes. There are studies that show doctors behave less affectively and empathetically when interacting with ethnic minority patients [Citation43]. In multi-ethnic societies, recognising this difference is crucial as patients prefer to speak in their own language, or they encounter difficulties in explicitly expressing themselves [Citation44]. Both students and patients highlighted the importance of having a common language when communicating with one another. Patients’ level of education was perceived by students to influence their social behaviour which in turn impacted the way they were able to converse and comprehend information. Malpractice litigation against doctors has often arisen because of miscommunication [Citation19].

Cultural beliefs, being embedded in family values, are crucial in patients’ acceptance of western medicine [Citation4,Citation5,Citation11,Citation38,Citation45]. Elderly patients attending the primary care facilities hail from different backgrounds and ethnicities and often have their own perceptions about illness and treatment [Citation46]. Our findings confirmed that early experiential learning with clinical immersion in the primary care setting helped to contextualise students’ learning, making it more realistic, and creating awareness of patients’ cultural beliefs. Early experiential learning in the context of primary care helps facilitating socialisation with relatively less ill patients and familiarisation with roles of other members in the clinical team. This may foster early professional identity formation [Citation47–49].

The findings have allowed medical educators and physicians to better visualise what they had previously taken for granted. Although clinicians are experienced in the patient-doctor relationship, this is often inadequate for the purposes of teaching communication skills to medical students [Citation50,Citation51]. The primary care or the community setting, is a powerful learning environment [Citation46], however learning can be impacted by clinician educators’ workload, readiness to supervise and provide immediate feedback to students. However, patient voices as shown in this study, highlights to faculty the biggest ally they have when training medical students, the patient. By engaging patients to provide more feedback to students, the faculty now role models to students the importance of patient voices in developing and enhancing a doctor’s skills. Patients have an important role in contributing to, assessing, and perhaps even designing undergraduate communication skills education. To encourage patient participation in training in a multilingual environment, more efforts should be directed towards the development of formalised interpreter services to build the communication and learning bridges with students [Citation52].

Our study has highlighted like others, opportunities for students’ self-reflection, are key for developing their communication skills. Compared to classroom learning with standardised patients, authentic learning from patients enhances students’ self-efficacy and self-reflection towards the importance of communication skills [Citation47–49]. Models used as frameworks for undergraduate communication skills training have always been in the ‘ideal’ context which is often different from the ‘real’ world context. Faculty should be trained to encourage students to embrace their own unique styles in the real world while keeping within the framework [Citation52,Citation53]. They must be transparent about their own struggles with difficult doctor-patient consultations, and by sharing their personal experiences with students, inculcate reflective practices for more patient-centred communication.

It is important to highlight that, while a whole range of factors emanating from sociocultural differences may pose a challenge to medical students’ communication behaviour, these unique cultural experiences can be used positively as enablers to inculcate not only self-reflection and metacognition [Citation45], but also cultural awareness and cultural competence for medical students early in training.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. As doctor/student-patient interactions are frequently long term and involving multiple visits, the generalisability of this study, which is cross-sectional, can be a limitation. We acknowledge that the presence of other health professionals or patients in a primary care setting may impact these interactions. The context of the study was a primary health clinic with students from one institution and the restricted access to students and patients during the COVID-19 pandemic was another limitation. Students may have less exposure for primary care as clinical teaching time was reduced by 30%.

Conclusion

Socio-cultural differences in communication can cause discordance in the doctor-patient relationship. In our study, aligning student and patient voices helped to identify and broaden perspectives on factors, challenges and enablers that influenced patient-centred communication skills. This in-depth perspective is important in designing clinical learning activities, reiterating the importance of early and continuous experiential learning in authentic cross-cultural primary care settings. The study highlighted students’ need for socio-cultural competence with patients of diverse ethnicities and cultures for work readiness, and faculty’s readiness to facilitate this. Supplementing the voices of patients in addition to those of medical students, is the unique feature of this study, widening the door for patient involvement in primary care training and assessment of undergraduate medical education.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the IMU Research and Ethics Committee [Ref no.4. 12/JCM-200/2020] and the National Medical Review and Ethics Committee [NMRR-20-2552-56163 (IIR)].

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our thanks to all students and patients for sharing their experiences, views and participation in this study. We would also like to express our appreciation to Prof Ian Wilson for his valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Hall P, Keely E, Dojeiji S, et al. Communication skills, cultural challenges and individual support: challenges of international medical graduates in a Canadian healthcare environment. Med Teach. 2004;26(2):120–125. DOI:10.1080/01421590310001653982

- Wright A, Regan M, Haigh C, et al. Supporting international medical graduates in rural Australia: a mixed methods evaluation. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:91–108.

- Gude T, Vaglum P, Anvik T, et al. Do physicians improve their communication skills between finishing medical school and completing internship? A nationwide prospective observational cohort study. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(2):207–212. DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2008.12.008

- Claramita M, Dalen JV, van der Vleuten CPM. Doctors in a Southeast Asian country communicate sub-optimally regardless of patients’ educational background. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):e169–174.

- Claramita M, Nugraheni MDF, van Dalen J, et al. Doctor–patient communication in Southeast Asia: a different culture? Adv Health Sci Educ. 2013;18(1):18. DOI:10.1007/s10459-012-9352-5

- Claramita M, Arininta N, Fathonah Y, et al. A partnership-oriented and culturally-sensitive communication style of doctors can impact the health outcomes of patients with chronic illnesses in Indonesia. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(2):292–300. DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2019.08.033

- Lee Y-M, Lee YH. Evaluating the short-term effects of a communication skills program for preclinical medical students. Korean J Med Educ. 2014;26(3):26.

- Kee JWY, Khoo HS, Lim I, et al. Communication skills in patient-doctor interactions: learning from patient complaints. Health Professions Educ. 2018;4(2):97–106. DOI:10.1016/j.hpe.2017.03.006

- Walters L, Greenhill J, Richards J, et al. Outcomes of longitudinal integrated clinical placements for students, clinicians and society. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1028–1041. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04331.x

- Claramita M, Susilo AP, Kharismayekti M, et al. Introducing a partnership doctor-patient communication guide for teachers in the culturally hierarchical context of Indonesia. Educ Health. 2013;26(3):26. DOI:10.4103/1357-6283.125989

- Claramita M, Utarini A, Soebono H, et al. Doctor–patient communication in a Southeast Asian setting: the conflict between ideal and reality. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2011;16(1):69–80. DOI:10.1007/s10459-010-9242-7

- Moore M. What do Nepalese medical students and doctors think about patient-centred communication? Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(1):38–43.

- Szasz TS, Hollender MH. A contribution to the philosophy of medicine: the basic models of the doctor-patient relationship. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;97(5):585–592.

- Balint M The doctor, his patient and the illness. 2000.

- McWhinney I. The need for a transformed clinical method. Communicating with medical patients. Stewart M, Roter D, editors. London: Sage; 1989.

- Hellin T. The physician–patient relationship: recent developments and changes. Haemophilia. 2002;8(3):450–454.

- Byrne PS, Long BEL Doctors talking to patients: a study of the verbal behavior of general practitioners consulting in their surgeries. 1976;

- Levenstein JH, McCracken EC, McWhinney IR, et al. The patient-centred clinical method. 1. A model for the doctor-patient interaction in family medicine. Fam Pract. 1986;3(1):24–30. DOI:10.1093/fampra/3.1.24

- Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, et al. Physician-patient communication the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277(7):277. DOI:10.1001/jama.1997.03540310051034

- Kaba R, Sooriakumaran P. The evolution of the doctor-patient relationship. Int J Surg. 2007;5(1):57–65.

- Paternotte E, van Dulmen S, van der Lee N, et al. Factors influencing intercultural doctor–patient communication: a realist review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(4):420–445. DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.018

- Paternotte E, Fokkema JPI, van Loon KA, et al. Cultural diversity: blind spot in medical curriculum documents, a document analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):14. DOI:10.1186/1472-6920-14-176

- Paternotte E, Scheele F, Seeleman CM, et al. Intercultural doctor-patient communication in daily outpatient care: relevant communication skills. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(5):268–275. DOI:10.1007/S40037-016-0288-Y

- Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care: the patient should be the judge of patient centred care. Br Med J. 2001;322(7284):444–445.

- Stewart M, Meredith L, Ryan BL, et al. The patient perception of patient-centeredness questionnaire (PPPC). London, ON: Centre for Studies in family medicine, Schulich College of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University; 2004.

- Junaid A, Rafi MS. Communication barriers between doctors, nurses and patients in medical consultations at hospitals of Lahore Pakistan. Pakistan Armed Forces Med J. 2019;69:560–565.

- Mukohara K, Kitamura K, Wakabayashi H, et al. Evaluation of a communication skills seminar for students in a Japanese medical school: a non-randomized controlled study. BMC Med Educ. 2004;4(1).

- Pun JKH, Chan EA, Wang S, et al. Health professional-patient communication practices in East Asia: an integrative review of an emerging field of research and practice in Hong Kong. South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Mainland China: Patient Educ Couns; 2018.

- Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(7):51.

- Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. Br Med J. 2001;323(7318):323. DOI:10.1136/bmj.323.7318.908

- Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38–43.

- Kusnanto H, Agustian D, Hilmanto D. Biopsychosocial model of illnesses in primary care: a hermeneutic literature review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7(3):497.

- Grau Canét-Wittkampf C, Eijkelboom C, Mol S, et al. Fostering patient-centredness by following patients outside the clinical setting: an interview study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–8. DOI:10.1186/s12909-020-1928-9

- Perron NJ, Sommer J, Louis-Simonet M, et al. Teaching communication skills: beyond wishful thinking. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14064.

- Carrillo JE, Green AR, Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural primary care: a patient-based approach. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):829–834.

- McQuaid EL, Landier W. Cultural issues in medication adherence: disparities and directions. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):200–206.

- Balint E. The possibilities of patient-centered medicine. J Royal Coll Gen Practit. 1969;17(82):17.

- Chandratilake M, Nadarajah VD, Mohd Sani RMB. IMoCC–Measure of cultural competence among medical students in the Malaysian context. Med Teach. 2021;43(sup1):43.

- Ho MJ, Gosselin K, Chandratilake M, et al. Taiwanese medical students’ narratives of intercultural professionalism dilemmas: exploring tensions between Western medicine and Taiwanese culture. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2017;22(2):22. DOI:10.1007/s10459-016-9738-x

- Merriam SB, Tisdell EJ. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2015.

- Paisley PO, Reeves PM. Qualitative research in counseling. Handbook Counsel. 2001;481–498.

- Clarke V, Braun V, Hayfield N Thematic analysis. Qualitative psychology: a practical guide to research methods. 2015;222:248.

- Schouten BC, Meeuwesen L. Cultural differences in medical communication: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1–3):21–34.

- Seijo R, Gomez H, Freidenberg J. Language as a communication barrier in medical care for Hispanic patients. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1991;13(4):363–376. Internet. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/07399863910134001

- Yamada S, Maskarinec GG, Greene GA, et al. Family narratives, culture, and patient-centered medicine. Fam Med. 2003;35:279–283.

- Yunus NM, Abd Manaf NH, Omar A, et al. Determinants of healthcare utilisation among the elderly in Malaysia. Institut Econom. 2017;9:115–140.

- Dornan T, Littlewood S, Margolis SA, et al. How can experience in clinical and community settings contribute to early medical education? A BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2006;28(1):3–18. DOI:10.1080/01421590500410971

- Whitford DL, Hubail AR. Cultural sensitivity or professional acculturation in early clinical experience? Med Teach. 2014;36(11):951–957.

- Wenrich MD, Jackson MB, Wolfhagen I, et al. What are the benefits of early patient contact? - a comparison of three preclinical patient contact settings. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1).

- Perron NJ, Cullati S, Hudelson P, et al. Impact of a faculty development programme for teaching communication skills on participants’ practice. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90(1063):90. DOI:10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131700

- Bylund CL, Brown RF, di Ciccone BL, et al. Training faculty to facilitate communication skills training: development and evaluation of a workshop. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(3):70. DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.024

- Pocock NS, Chan Z, Loganathan T, et al. Moving towards culturally competent health systems for migrants? Applying systems thinking in a qualitative study in Malaysia and Thailand. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231154. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0231154

- Bombeke K, Symons L, Vermeire E, et al. Patient-centredness from education to practice: the ‘lived’ impact of communication skills training. Med Teach. 2012;34(5):e338–348. DOI:10.3109/0142159X.2012.670320

Appendix 1

The interview was guided by an interview protocol which included samples as shown below.

For students: -

How well do you think you conduct a medical interview with a patient?

Can you think of any factors that may cause a medical interview with a patient to be easy or difficult for you?

When interviewing patients, what areas are you most uncomfortable enquiring about?

What can you do better in communication skills or medical interviews with a patient?

For patients: -

What are your perceptions about the communication skills of medical students?

What do you think are the challenges medical students have with their communication skills?

How would you like medical students to communicate with you?

Which areas of medical interviews can be improved further?