ABSTRACT

Clinicians with teaching and training roles should be adequately trained and assessed. However, some debate exists as to what the nature of this training should be. Historically, a postgraduate certificate in education was a pre-requisite to becoming a GP trainer but this is changing with growing concern that such a pre-requisite might act as a deterrent to potential GP trainers. This research examines the impact of a scheme designed to provide an alternative, more practical and focused, pathway to becoming a GP trainer. We interviewed 26 course participants and stakeholders of the London GP Training Course (LGPTC), observed teaching sessions, and analysed course materials. We asked what elements of the course were and weren’t effective, for whom, and under what circumstances. Here, we present a summary of our main findings – that GP trainers want to know practically, not theoretically, how to be a trainer; formative assessment boosts trainees’ confidence in their own skills and abilities; short, practical GP training courses can help enhance the numbers of GP trainers; important questions remain about the role and value of educational theory in education faculty development.

Background

Concern is growing around the declining numbers of general practitioners (GPs) in the UK and the impact this has on the capacity of primary care [Citation1–5]. Educational Supervisors of GPs in specialty training – or GP trainers – are a key part of this, as they help to train and build the GP workforce. To meet increasing GP specialty trainee recruitment targets it is therefore crucial to also increase the numbers of GP trainers available to train them. Historically, new GP trainers were required to complete formal (often time-consuming) training themselves, such as a Postgraduate Certificate in Medical Education (PGCME or PGCert) before they could begin any form of educational supervision [Citation6–8]. We know that a lack of available time is a significant barrier to attracting GPs to such roles [Citation9–12].

Health Education England (HEE) launched the London General Practitioner Trainer Course (LGPTC) in February 2018 which attempted to attract new GP trainers to the role by reducing the time commitment required to become one. Compared with the postgraduate certificate (PGCert) it had previously required, the LGPTC was shorter and focussed on developing individuals’ practical skills rather than theoretical knowledge. Teaching methods included face-to-face teaching and small group work, self-directed learning, and reflective portfolios (the topics covered and delivery methods are provided in ). Crucially, course architects intentionally reduced expectations of participant engagement with educational theory (compared to the PGCert) and their knowledge and understanding of it was not assessed. Indeed, there was no formal assessment on the LGPTC. LGPTC participants were also invited to join a local GP trainer’s workshop. The content of these varied by location, but the intent was to put all GP trainers and trainee-trainers together to share experiences and foster an environment of collaborative, peer to peer, learning. Attendance at these meetings was optional and was not monitored. It was instead offered as an additional learning resource. Once they had completed the course, participants were issued with a certificate of completion and were eligible to formally apply to become a GP trainer. The authors were commissioned to conduct a critical evaluation of this new course [Citation13].

Table 1. LGPTC Course content and format.

Aims

The central aim of our research was to understand whether the LGPTC effectively prepared GPs to work as GP trainers. Guided by the realist approach to research [Citation14–17], we sought to discover ‘what was working, for whom, in what context, in what respects, and how’. [Citation17] Our research questions are detailed in . This paper summarises our main findings, which are informed by all of the research questions.

Table 2. Research questions.

Design and setting

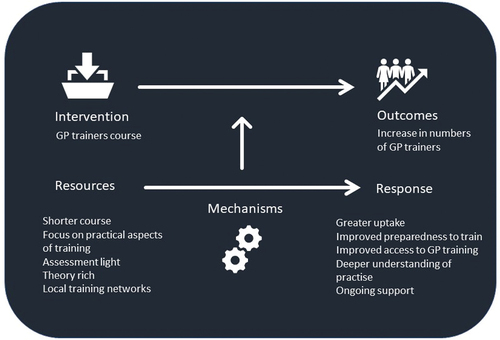

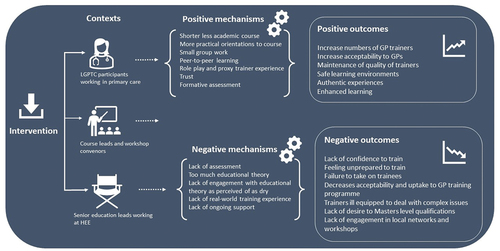

Employing the realist approach to research [Citation10–13] enabled us to delve into stakeholders and course participants’ experiences of the LGPTC and answer our research questions. First, the research team developed initial programme theories (IPTs) about how the LGPTC was intended to work (). IPTs were developed via discussions with LGTPC ‘course architects’ and a documentary analysis of course materials. These theories were then ‘tested’ in field.

The study population comprised of participants from Cohorts 1 (n = 3) and 2 (n = 12) of the LGPTC, as well as stakeholders in the course (n = 11). The ‘stakeholder’ group included those involved in the design and delivery of the course, those with a vested interest in increasing GP training capacity in London, and those involved with GP training more broadly at HEE.

Methods

Documentary analysis

All course materials and information documents shared with participants were analysed and used to develop our IPTs.

Observations

We observed two teaching sessions during cohort 2. Observations permitted contextual understandings about the LGPTC which aided discussions with research participants. A summary of the findings from these observations can be found in the original research report [Citation10].

Recruitment of participants

Stakeholders and course participants from cohort 1 were recruited via email sent by HEE on behalf of the research team; course participants from cohort 2 were recruited in person during their penultimate and last in-person training days (all detailed in ). Individuals who consented to participate took part in a focus group or a semi-structured interview. Interviews and focus groups took place in person or by telephone June – September 2018.

Table 3. Participants roles and data source.

Ethical approval was given by UCL Joint Research Office 13,311/001. All materials were anonymised and held confidentially in compliance with General Data Protection regulations 2018 (GDPR).

Interviews and focus groups

Interviews and focus groups were conducted with 26 participants (participant demographics relevant to the course are detailed in ). Both focus groups and one interview were conducted face-to-face. The remaining interviews were conducted via telephone. Semi-structured interview schedules for interviews and focus groups were designed to test IPTs. Allowing the research team to explore the lines of enquiry and concepts deemed important to the study, whilst allowing sufficient flexibility for participants to share their views and experiences. All interviews were audio recorded for accuracy and transcribed professionally.

Data analysis

The principles of realist analysis [Citation10–13] guided data analysis. Coding of transcripts was iterative, sensitised by realist theory [Citation10–13] and framed using our IPTs We then developed Context-Mechanism-Outcome (C-M-O) configurations for all outcomes identified which were then used to develop our modified programme theories about how the LGPTC worked. (see ).

An initial coding scheme was developed based on the analysis of four transcripts. The comparison between researchers’ coding of the same transcripts and a team discussion about these was used to devise the coding framework that was used on remaining transcripts. All of the research interviews were then coded in accordance with this framework, using QSR NVIVO 11©.

Results

Here, we summarise our findings by presenting the main results from our analysis of the interviews and focus groups. Due to the complexity of the various C-M-O configurations produced during data analysis, results are presented thematically but with reference to them.

Strengths

Broadly speaking, stakeholders and participants felt that the LGPTC prepared individuals to become GP trainers. It’s practical focus and short time commitment were popular and considered to be an advantage over a longer, theoretical programme (context):

“I had been really nervous about the level of work required for a PGCERT, and people often talk about how it’s really theoretical, […] And people are quite down on it, generally […] So I was pleased not to be doing it […] what was really nice about this course, and I think a lot of people felt it, it was really practical. You felt like they taught you the stuff that you needed to actually do the job, rather than the theory.” (Course Participant)

This less demanding and flexible approach (mechanism) was reported to have no impact on the quality of GP trainer produced (outcome):

“I think the ADs [Associate Directors] […] don’t seem to have spotted the difference between those who have done postgraduate certificate and those coming through in anything they’ve said to me.” (Senior GP Education Lead)

Participants were positive about the in-person teaching days (outcome); particularly the ways they maintained a healthy balance between theory and practice (mechanism):

“I like the way as well though, you’re taught for the first part of the morning, entertained at the taught theory of it with a bit of a presentation and didactic slides, etc., but then towards the end of the morning you’d have that small group where we’d all break out a little bit and we’d have our own thoughts and then we’d represent them back”. (Course Participant)

It was clear that small group work (mechanism) created trusted ‘safe spaces’ for participants to share their experiences and concerns (outcome). Trust built within these small groups (context) enabled peer learning to take place (outcome), as the groups felt able to try out new learning or teaching styles, and receive and provide constructive critiques without feeling ‘judged’ (mechanism):

“I think one of the benefits […] was a smaller group in a separate room and there was an understanding that we would keep our discussions amongst ourselves, you felt very protected. And you felt that you could role play […] without the fear of being looked at by lots of people and judged […] It was the same group throughout five weeks, and it did feel very comfortable that we could feed back to each other, critique to each other, question each other in a nice way, which definitely wouldn’t have been possible in a large group.” (Course Participant)

“And we can give each other constructive feedback and we’ve been doing it long enough that we’re not so nervous or scared by that, I think it’s a much more effective way of learning rather than a lot of […] lectures.” (Course Participant)

Weaknesses

Not all LGPTC participants felt confident to train after the course (outcome). This lack of confidence (context) is important as it may impact on participants’ willingness to take on trainees (outcome):

“I don’t think that I feel super-confident based on just this course to then go ahead and be a trainer.” (Course Participant)

Lack of confidence arose because participants did not yet have trainees (context) and feared the unknown (mechanism):

“So, I still feel anxious about what it’s actually going to be like, being a trainer and what I know is, kind of, the overall gist of what they have to do.” (Course Participant)

Some stakeholders expressed concern that the LGPTC was too short to prepare new trainers adequately:

“Comparing it to my own experience of being trained to be a trainer, obviously I thought it [PGCERT] was a better course. I think it [the new course] feels a bit too short and a bit too rushed.” (Course Tutor)

“One of my concerns is - I mean, as you saw this afternoon, several people went early, we’d got two people away, and given this is their only course that they’re doing and it’s five days […] it feels a bit superficial at times.” (Course Tutor)

Perceived stakeholder limitations of the shorter course included a lack of content on GP registrar assessments, and a reduced opportunity to develop the multitude of skills required to manage complex situations experienced as a GP trainer. The need for ongoing support beyond the end of the LGPTC was voiced by many research participants:

Maybe after they had a trainee for six months, they need to have, you know, actually did it work, what new needs did you identify […] maybe a little bit of ongoing support […] once you’ve had a trainee and are actually doing it. (Course Tutor)

The role of educational theory

Stakeholders and course participants held differing views about the need for educational theory on the LGPTC (and GP training more generally). Some stakeholders were concerned that the LGPTC’s reduction in educational theory (mechanism) meant participants were not as well prepared for training as they could be (outcome). This was because theory was felt to be valuable for trainers, particularly when they are dealing with unfamiliar or challenging situations (context). For stakeholders, ensuring that participants understood educational theory was believed to be key to preparing trainers for training.

“I think you’re much more likely to be a better educator if you’ve got a thorough understanding of educational theory. You know I think it’s something that assist you in that developmental journey.” (Senior GP Education Lead)

“I think what we’re talking about is being educators and not trainers, and […] I think that gets to the heart of it. And I think you need some basic adult education theory.” (Senior GP Education Lead)

However, stakeholders also recognised that a reduced exposure to educational theory (mechanism) made the course more appealing and improved enrolment rates (outcome):

“It’s much more condensed and it’s much more relevant than the course that I did [PGCert]. If I’m right in saying, they really do look at the things like the e-portfolio, so it’s much more focused to what the trainer will be required to do.” (Local Workshop Convener)

“The new course there are people jumping to do it and queuing to do it because it’s much more, as I understand it to be, much more practical and less time-consuming.” (Associate Director)

There was a strong sense that theory should be relevant to everyday practice and not taught for the sake of it – ‘going OTT’ (Associate Director). Further that the theory could be learnt by self-study and reflection rather than through lecture-based activities.

Course tutors felt that there was sufficient theoretical content on the LGPTC (context), but there was hope that trainers would continue to engage with educational theory as they progressed though their career (outcome):

“I think they get an introduction into educational theory and the basics, but I think it is very much the start of it […] I mean, I think it’s knowing the theory exists, which they have varying experience of how much they know about it. It’s understanding how it’s put into practice.” (Course Tutor)

Indeed, the general feeling amongst stakeholders, was that the role of the LGPTC was to spark an interest in educational theory (mechanism-outcome) that would inform future practice (outcome) as educational theory was considered useful for a variety of reasons (context).

Most course participants were unenthusiastic about learning theory and, despite a reduction in compulsory theoretical content, some participants still perceived the LGPTC to be ‘theory-heavy’ (context). This theoretical focus (mechanism) did not help them to feel prepared or confident in their abilities to train (outcome):

“actually what I’m worried about is how am I going to actually translate that into having somebody sat in a room with me and trying to be their supervisor.” (Course Participant)

“I think you should be aware of the principles and the different theories that are out there, but, I mean, you’ve still got to be able to deliver it and be practical and adjustable to your learner.” (Course Participant)

Nor did it help engagement with the course (outcome). For participants, the ‘dry’, more academic texts were challenging to engage with because they were difficult to understand (mechanism) and the real-world applicability of it was questioned (outcome):

“Some of the papers - I mean, like there was a very dry one on curriculum planning which you could - I think maybe if they’d chosen sort of things that were - or tried to think of tasks that were a bit more relevant to their actual work of being a GP trainer and their own experience of having been a trainee, it might have got a bit more buy in.” (Course Tutor)

“The facilitators, you could see, were really keen too. They’re obviously keen educators and experienced educators, and it was clear to see their enthusiasm [for the theory]. But […] there are people here that are thinking, I don’t really necessarily care […] What do I need to really tell my trainee to get on board with doing?” (Course Participant)

Academic texts provided as pre-course reading appeared to be off-putting (mechanism), making LGPTC participants less likely to explore postgraduate options after completing (outcome).

Assessment

All interviewees noted that assessment (mechanism) acts as a barrier to GPs becoming trainers (outcome).

“And some people really aren’t theory people. They really aren’t essay people. So that did cut out a little, a group at points when it came to those aspects, I suppose.” (Course Participant)

“But, you know, there are some very, very good less-academic people teaching who I think stand a better chance with the new course and the PGCert did put some of them off.” (Associate Director)

For stakeholders who valued assessment as a tool for identifying struggling students (context), the lack of assessment on the LGPTC (mechanism) was worrisome as they felt it could lead to a slip in standards (outcome):

“So in the current context, I get it. We need more trainers and we have no money. But I think we still have to think about quality and the bar, and how we’re assessing people, you know, but there is no assessment.” (Senior GP Education Lead)

“I guess the assessment is really the training application, but the question is, does that assure quality? And I don’t think, it probably doesn’t.” (Senior GP Education Lead)

For such stakeholders (context), the removal of accreditation and assessment (mechanism) positioned the LGPTC as a less robust programme (outcome):

“It used to be an achievement to be a trainer and I think they [trainers with PGCert] also feel it’s eroding the level of achievement of them being a trainer themselves because now it’s become easier to be a trainer.” (Senior GP Education Lead)

A sentiment that was shared by some participants:

‘I think that adding in an assessment to something this condensed, what do you assess? […] Are you making the assessment more about the educational theory side of things? In which case I […] would have done a PG Cert and got a higher level qualification?’ [emphasis added] (Course Participant)

The lack of assessment on the course was concerning for LGPTC participants too. They felt that assessment prepared them for training (context), and that without it (mechanism) they had no way of knowing if they knew (i) the right things, (ii) enough to be able to train (outcome). However, it was important for participants that the assessment undertaken was formative in nature (outcome) – where the purpose is to give feedback and assist with learning but is not too demanding on participants’ time (mechanism):

“I don’t like assessment, but […] you don’t know if I’ve learnt anything. And I really might not have done.” (Course Participant)

“Sometimes we would like to know that we’ve achieved something so we have some formative assessment at the end of it to say actually, yes, you reached the required standard and now you can go forward. And sometimes that can act as some form of - get some confidence from that essentially to say, actually, yes, I’m of a certain level whereas at the moment it’s uncertain really, where we are.” (Course Participant)

The relationship between assessment and confidence is underpinned by a ‘rubber stamping’ process; that passing an assessment provides confidence as it tells the participant that they know all that they need to know to effectively train. Offering the opportunity to provide feedback to the participants was deemed vital and provided a benchmark for them to measure themselves against so that they know where they stood, and how they can improve.

Discussion

Summary

This study found that, for stakeholders, the LGPTC effectively prepared participants to be GP trainers as participants were thought to be exposed to the necessary information to effectively train and supervise GP trainees. However, it failed to invoke this sense in course participants who were insecure about their preparedness to train. One way to counter this insecurity is to include more personalised and detailed feedback through formative assessment. The importance of this finding is that it suggests that assessment of some kind is necessary not just for learning, but for giving learners confidence in their acquired skills and knowledge.

This study also found that exposure to, and learning about, educational theory was more important to GP trainer course stakeholders than it was to course participants. It was suggested that a reduced exposure to educational theory did not affect individuals’ perceived abilities to train. This finding is important as it raises an important (albeit open) question that GP trainer course conveners need to consider – how much educational theory do GP trainers need to know in order to train effectively?

Strengths and limitations

One limitation of this study is that we spoke to a disproportionate number of participants from the second cohort of the LGPTC. However, there was no evidence that the programme was delivered differently between cohorts one and two. Another was that, participation was entirely voluntary and so there may be some self-selection bias. One strength of this study is that it utilises a well-defined methodology and conceptualisation to shape its design, data gathering, and data analysis. Researchers were also careful to gather a range of different perspectives and so the conclusions drawn here are considered and robust.

Comparison with existing literature

Within medical education, the adage that ‘assessment drives learning’ is generally accepted [Citation18] Our findings support this, and we also found that assessment fosters confidence in one’s skills and abilities, creating a willingness to go on and begin to train. Not only does assessment drive learning here, it drives confidence and action. Furthermore, this evaluation highlights a need and desire for formative assessment. The beneficial impact of formative assessment to student achievement has long been argued by educational researchers [Citation19–21] and there is a growing body of work recognising it’s importance in medical education, particularly at the undergraduate level [Citation22–24]. Formative assessment in medical education is thought to guide learning by offering detailed feedback rather than just a grade [Citation25]. Although more time-consuming than alternative forms of assessment, it is known to make the learning encounter engaging and worthwhile [Citation25] as it can focus learners on effective learning and divert their attention away from grades and ‘reproductive thinking’. [Citation26] Our findings contribute to this literature, offering an additional benefit of formative assessment in medical education faculty development – building learners’ confidence in their knowledge and abilities.

Our findings question the importance of educational theory in delivering effective GP training. This question is implicit within the literature relating to GP training in the UK and internationally, but we have been unable to find an explicit exploration of it. For example, it is accepted that the relationship between GP trainee and trainer is an important factor in trainee success [Citation27,Citation28]. Strong bonds in these trainer/trainee relationships, underpinned by elements such as pastoral support and positive role-modelling, are known facilitators for effective training [Citation27], as learners can struggle to disclose their vulnerabilities or accept the feedback given from supervisors they have no (or shallow) relationships with [Citation28]. This outlook foregrounds the importance of a GP trainers’ interpersonal skills in effectively training. It is also accepted that experience gives valuable and meaningful insight to help trainers train more effectively [Citation29], foregrounding the importance of exposure to varied, and practical, learning opportunities for trainers to train effectively.

Our findings support previous works that suggest requiring new trainers to achieve a postgraduate certificate may dissuade some GPs from becoming trainers [Citation6], that trainee-trainers seek to understand the ‘nuts and bolts’ of becoming a trainer more than educational theory [Citation7], and that not all trainers desire academic qualifications in education [Citation30].

Implications for research and/or practice

Our research has a number of implications for future practice. It has shown that GP trainers want to know practically how to be a trainer, which has significance for educational practice and curriculum development; highlighting the importance for practical aspects of training to be included. It has shown that formative assessment boosts trainees’ confidence in their own skills and abilities; highlighting the importance of quality feedback. It has also shown that short, practical, ‘theory light’ training courses can help enhance the number of GP trainers.

An area for future research is to explore in more detail the role and value of educational theory in education faculty development, as well as to evaluate the impact of the new training regime in terms of trainer quality or capacity.

Ethical approval

The project was presented to the UCL Joint Research Office 13,311/001 and given ethics clearance by Chair’s Action.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr Asta Medisauskaite, Dr Graham Easton, Dr Leila Mehdizadeh, Dr Elliot Rees and Halima Shah for their help with data collection; staff at Health Education England for supporting recruitment to the study; and all research participants whose time and insights were invaluable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Royal College of General Practitioners, British medical association, NHS England, health education England. Building the workforce - the new deal for general practice [Internet] 2015 2 Feb 2023]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/01/building-the-workforce-new-deal-gp.pdf

- NHS England. General practice forward view [Internet] 2016 [cited 2 Feb 2023]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/gpfv/

- Peckham S, Marchand C, Peckham A General practitioner recruitment and retention: an evidence synthesis: Final report. Policy Research Unit In Commissioning And The Healthcare System, University Of Kent. Kent, England. [Internet] 2016 [cited 2 Feb 2023]. Available from: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/58788/1/PRUComm%20General%20practitioner%20recruitment%20and%20retention%20review%20Final%20Report.pdf

- NHS Long Term Plan [Internet] 2019 [cited 2 Feb 2023]. Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf

- The Government’s 2022-23 mandate to NHS England [Internet] 2022 [cited 2 Feb 2023]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1065713/2022-to-2023-nhs-england-mandate.pdf

- Lake J. Upping the game? Attitudes towards combining a GP trainer course with a postgraduate certificate in medical education in Wessex, UK. Educ Prim Care. 2014;25(5):263–267. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2014.11494292

- Main P, Pitts J, Hall A, et al. Becoming a general practice trainer: experience of higher preparatory training. Educ Prim Care. 2006;17(4):334–342. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2006.11864083

- Lyon-Maris J, Scallan S. Procedures and processes of accreditation for GP trainers: similarities and differences. Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(6):444–451. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2013.11494215

- Pitts J, While R, Smith F. Educating doctors within primary care: attracting non-training general practitioners to train. Educ Prim Care. 2005;16(1):36–41. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2005.11493480

- Thomson J, Haesler E, Anderson K, et al. What motivates general practitioners to teach. Clin Teach. 2014;11(2):124–130. doi: 10.1111/tct.12076

- Ingham G, Fry J, O’Meara P, et al. Why and how do general practitioners teach? An exploration of the motivations and experiences of rural Australian general practitioner supervisors. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):190–198. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0474-3

- Sturman N, Régo P, Dick M-L. Rewards, costs and challenges: The general practitioner’s experience of teaching medical students. Med Educ. 2011;45(7):722–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03930.x

- Griffin A, Knight L, Page M, et al. A critical evaluation of the London GP trainer programme. [Internet] 2018 [cited 27 April 2023] Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/medical-school/sites/medical-school/files/lgptc-final-report-september-2018.pdf

- Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation. London (UK): Sage; 1997.

- Pawson R, Tilley N. An introduction to scientific realist evaluation. In: Chelimsky E Shadish WR, editors Evaluation for the 21st century: a handbook. Sage Publications, Inc; 1997. pp. 405–418.

- Pawson R. The Science of Evaluation: a Realist Manifesto. London (UK): SAGE Publications Ltd; 2013. doi: 10.4135/9781473913820

- Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, et al. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0643-1

- Wormald BW, Schoeman S, Somasunderman A, et al. Assessment drives learning: an unavoidable truth? Anat Sci Educ. 2009 Oct;2(5):199–204. doi: 10.1002/ase.102

- Black P, Wiliam D. Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment In Edu Principles, Policy & Practice. 1998;5(1):7–74. doi: 10.1080/0969595980050102

- Black P, Harrison C, Lee C, et al. Working inside the black box: assessment for learning in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan. 2004;86(1):8–21. 2004. doi: 10.1177/003172170408600105

- Black P, Wiliam D. Inside the black box: raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan. 1998 Oct;80(2):139–148.

- Burgess A, Mellis C. Feedback and assessment for clinical placements: Achieving the right balance. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:373–381. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S77890

- Konopasek L1, Norcini J, Krupat E. Focusing on the formative: building an assessment system aimed at student growth and development. Academic Medicinequery. 2016 Nov;91(11):1492–1497. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001171

- Srivastava TK, Mishra V, Waghmare LS. Actualizing mastery learning in preclinical medical education through a formative medical classroom. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;8(3):450–464. doi: 10.5455/njppp.2018.8.1144129112017

- Ferris HA, O’Flynn D. Assessment in medical education; What are we trying to achieve? Int J Higher Edu. 2015;4(2):139–144. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v4n2p139

- Liu N, Carless D. Peer feedback: the learning element of peer assessment. Teach Higher Educ. 2006;11(3):279–290. doi: 10.1080/13562510600680582

- Jackson D, Davison I, Adams R, et al. A systematic review of supervisory relationships in general practitioner training. Med Educ. 2019;53(9):874–885. doi: 10.1111/medu.13897

- Wearne S. Effective feedback and the educational alliance. Med Educ. 2016;50(9):891–892. doi: 10.1111/medu.13110

- Lesmes-Anel J, Robinson G, Moody S. Learning preferences and learning styles: A study of Wessex general practice registrars. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(468):559–564.

- Waters M, Wall D. Educational CPD: how UK GP trainers develop themselves as teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):e160–e169. doi: 10.1080/01421590701482431