ABSTRACT

Portfolios are often implemented to target multiple purposes, e.g. assessment, accountability and/or self-regulated learning. However, in educational practice, it appears to be difficult to combine different purposes in one portfolio, as interdependencies between the purposes can cause tensions. This paper explored directions to manage tensions that are inextricably linked to multipurpose portfolio use. We used a systems thinking methodology, that was based on the polarity thinkingTM framework. This framework provides a step-by-step approach to chart a polarity map® that can help to balance the tensions present in specific settings. We followed the steps of the framework to chart a polarity map for multipurpose portfolio use. Based on literature and our prior research, we selected one overarching polarity: accountability and learner agency. This polarity seems responsible for multiple tensions related to multipurpose portfolio use. We formulated values (potential benefits) and fears (tensions that can arise) of the two poles of this polarity. Then, we organised a session with stakeholders who work with the portfolio of the Dutch General Practice speciality programme. Together we formulated action steps and early warnings that can help to balance accountability and learner agency during multipurpose portfolio use. In addition to previous recommendations concerning portfolio use, we advocate that it is important to create a shared frame of reference between all involved with the multipurpose portfolio. During this process, the acknowledgement and discussion of tensions related to multipurpose portfolio use are vital.

Introduction

Over the last decades, portfolios are implemented in medical education with the aim to support the qualification of competent, lifelong learning professionals [Citation1,Citation2]. The use of portfolios is not an isolated practice within medical curricula, instead it strongly relates to other current educational practices. Two of these practices we would like to mention here specifically: competency-based education and programmatic assessment.

Competency-based education (CBE) is centred around the competencies that are considered vital to the field being educated [Citation3]. CBE is outcome-based, as it prescribes the competencies that learners ought to possess in order to graduate. It is therefore considered more flexible and learner-centred than traditional education that also specifies how and when learners (and teachers) should achieve the desired results [Citation3]. Programmatic assessment aims to combine two purposes of assessment: learning and decision-making. These aims are pursued by developing an integrated programme of assessment that is intertwined with the curriculum, rather than assessing knowledge and/or skills (once at the end) of individual courses [Citation4]. In light of these educational practices, portfolios have been introduced within medical education around 1990 [Citation5]. Portfolios are often integrated into the assessment programme and may fulfil a role for formative assessment, summative assessment and/or accountability [Citation1,Citation2]. The exact role of the portfolio within the assessment programme may vary between the portfolio being the place where evidence for assessments and/or assessment results are collected and the portfolio content itself being assessed. Furthermore, portfolios are used to support self-regulated learning (SRL), which refers to ‘the degree to which students are metacognitively, motivationally, and behavio[u]rally active participants in their own learning process’ [Citation6]. Portfolio use is considered to support various SRL processes, in particular feedback seeking, reflection, self-assessment, goal setting and monitoring [Citation1,Citation2]. It is a common practice to implement portfolios that are intended to support multiple purposes [Citation5].

However, in educational practice, it proves to be complicated to serve different purposes with one portfolio [Citation1,Citation7–9]. This is exemplified by perceptions of learners, who often experience their portfolio to be an instrument for faculty that can assess their performance with using the portfolio rather than a tool that is beneficial for their own learning process [Citation10–12]. Apparently, the value of portfolio use for SRL can be compromised if assessment and/or accountability need to be served as well. Often discussed in this context is the combination of (summative) assessment and support of reflection for learning in one portfolio [Citation1,Citation7,Citation13–15]. The interdependency between purposes can cause tensions during portfolio use. Although reflective skills are considered vital for physicians and therefore important during competency assessment, learners may be reluctant to document in-depth reflections in their portfolios, because they fear that exposing doubts or uncertainties may give faculty members reading the contents of the portfolio a negative impression of their competence level, leading to an unfavourable assessment [Citation16,Citation17]. Insights of researchers and educators differ whether and how to deal with these tensions [Citation1,Citation7,Citation13,Citation15].

The approaches that have been suggested to deal with tensions of multipurpose portfolio use (e.g. the advice to stop assessing portfolios in order for reflection to take place) do not acknowledge the complexity of the problem at hand. Complexity theory describes that complex problems are signified by a large number of interconnected elements, that share interdependencies, are dynamic and intransparent [Citation18]. A pitfall is the expectation that a single, fit-for-purpose solution can solve a complex problem [Citation19–21]. The mentioned solution regarding multipurpose portfolio use shows that such solutions do not sufficiently address the interdependent and dynamic nature of a complex problem: when portfolios are not assessed, learners can be left with the feeling ‘what am I doing it for?’ [Citation9,Citation22].

In contrast, systems thinking methodologies are considered suitable to deal with complex problems [Citation21,Citation23], as these ‘recognize that factors relating to a problem are connected and dynamic, are considerate of diverse perspectives, and are aware of boundaries surrounding issues’ [Citation21]. An approach that fulfils the criteria of systems thinking methodologies is described by the polarity thinking TM framework. This framework focuses on polarities (also described as paradoxes or interdependent pairs) and offers an approach to find a balance for both poles of the polarity to co-exist [Citation19,Citation20].

This paper describes how the polarity thinkingTM framework was applied in order to explore possibilities to manage the tensions that are inextricably linked to multipurpose portfolio use.

Methods

Study context

This paper is part of a research project that studied the use of portfolios for the support of SRL within the Dutch General Practice (GP) speciality programme. During this project, a realist literature review, portfolio content analysis and qualitative focus group study were conducted [Citation24–26]. The results of these studies informed the formulation of the polarity map that is described in this paper (Appendix A provides a summary of these studies). In particular, the results of the focus group study were an important source for our discussions and decisions during the process of polarity map building. During this study, we organised nine focus groups to gather the perspectives on portfolio use of trainees, supervisors and faculty from three Dutch GP training institutes.

Methodological approach

The polarity thinkingTM framework was selected as it fulfils the criteria of a systems thinking methodology, which was considered suitable due to the complex problems related to multipurpose portfolio use. Central to the polarity thinkingTM framework is the concept of polarities, which encompasses different poles of a situation that appear to be in competition, but in fact depend on and need each other to thrive [Citation19,Citation20,Citation27]. Polarities are omnipresent and can be found within individuals (inhale vs. exhale), organisations (cost-effectiveness vs. service excellence) or nations (social security vs. self-reliance). Naturally, also medical education comes with polarities, as already shown by Govaerts et al., who outlined and reflected on two polarities of assessment: standardisation vs. authenticity and numbers (quantitative data) vs. words (qualitative data) [Citation19].

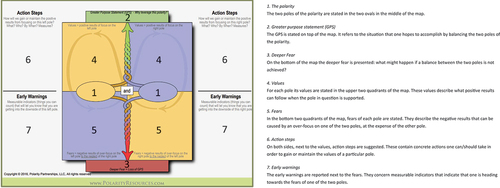

Polarity thinkingTM is based on the observation that tensions between the poles of a polarity are usually accommodated by solutions that focus on one of the two poles, which are referred to as either-or solutions. However, these types of solutions are generally too simplistic, as they do not take into account the interdependency between the two poles of the polarity. For this reason, polarity thinkingTM suggests that instead of an either-or solution, one should opt for a both-and approach, i.e. a balance in which both poles can co-exist [Citation19,Citation20]. In order to reach such a balance, a polarity map is composed through a step-by-step approach. shows the polarity map with a description of the different components.

Study procedure

Govaerts et al. described an approach to formulate a polarity map that aligns with the principles and instructions of the polarity thinkingTM framework [Citation19,Citation27]. Four members of the research team (RG, BT, SH, NS) performed these steps to chart a polarity map for the use of multipurpose portfolios in medical training. As described by the approach of Govaerts et al., stakeholders were involved during the third step of the process [Citation19]. The other members of the research team (JM, MS, AT) were involved on a consultation basis; they were regularly asked for their ideas and feedback.

Step 1: seeing

This step entails the appraisal of the polarities present in a specific setting. In accordance with the instructions of the polarity thinking frameworkTM, we first formulated issues of multipurpose portfolio use. These issues had been identified during literature study and the other studies of this research project, thereby describing the challenges we had encountered (problem) and the intended purpose of portfolio use (possibility). We primarily used problems that we encountered during our focus group study, but made sure that these problems were also described in the extended literature on portfolio use.

Secondly, we formulated an explanation for these problems (moving FROM) and the situation that one intends to reach through portfolio use (moving TO). These actions were performed individually by the team members (RG, BT, SH, NS). Thereafter, the proposed polarities of the different team members were discussed, which resulted in the selection of one overarching polarity. We quickly reached consensus, as the selected polarity was identified as the most important hindrance of portfolio use during our focus group study and we also encountered this polarity in papers that were read during our literature review.

Step 2: mapping

During this step, the components at the centre of the polarity map (the Greater Purpose Statement (GPS), deeper fear, values and fears) were completed. First, the team members (RG, BT, SH, NS) formulated these components individually. Then, the different suggestions were assembled, discussed and adjusted during multiple iterations, until a final version was established.

Step 3: tapping/leveraging

This step encompasses the formulation of action steps and early warnings through discussion during a session with stakeholders. We wanted to weigh-in a diversity of viewpoints and therefore included representatives of relevant stakeholder groups of the Dutch GP speciality training. These representatives were purposively approached via email and asked to participate in the stakeholder session. The final participants were two residents, two faculty members, two clinical supervisors, and one team leader. They all provided consent to participate in the stakeholder session.

Due to the COVID-19 guidelines in place at the time, the stakeholder session took place through videoconferencing (Zoom) and was moderated by the first author. First, the polarity thinking TM framework was presented. Next, the stakeholders were introduced to the polarity map on multipurpose portfolios, which had been drawn up during the first two steps. When it was clear that all participants understood the concept of polarity thinking TM and the different components of the polarity map on multipurpose portfolio use, the participants were invited to propose and discuss potential action steps and early warnings. The suggestions of participants were noted and shared on screen by the moderator. After 50 min, the discussion ended, as the participants did not offer any new ideas. The stakeholder session was audio recorded and later transcribed verbatim.

After the stakeholder session, the first researcher critically reviewed the suggested action steps and early warnings, in order to make sure that they were clear (i.e. easily comprehendable), concrete (i.e. easily observable) and distinctive (i.e. only applicable to the pole they were assigned to). Some adjustments were proposed and this version was sent to the participants of the stakeholder session, together with an explanation of the changes made to the initial version. Participants were invited to reply to this new version.

Reflexivity

As described above, the system thinking methodologies are characterised by – amongst others – a recognition of multiple perspectives. We believe this aligns with a constructivist paradigm, that acknowledges the social construction of reality. Therefore, we aimed to gather varying perspectives by utilising the different experiences, opinions and knowledge of the research team and including stakeholders with various backgrounds. In concern to the research team differences were amongst others the result of our professional backgrounds – psychology (RG, AT), educational science (BT, SH, MS), health science (SH) and medicine (BT, JM, NS) – and our own involvement with portfolios, as developer (BT, SH, MS), user (AT), or researcher (all authors).

Findings

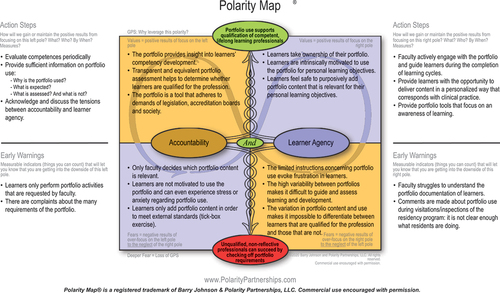

The polarity map on multipurpose portfolio use is presented in . The (reflections on) choices made during the development of this polarity map are explained below.

Step 1: seeing

The different polarities of multipurpose portfolio use that were proposed are presented in . Through discussion of this list, we recognised that the last four polarities could be seen as consequences of the first polarity, which focuses on accountability and learner agency. We defined accountability as ‘the responsibility of educators to the public’ and agency as ‘one’s capacity to act purposefully and autonomously’ [Citation28]. When striving for accountability (polarity 1) chances are that the portfolio will be used to handle (polarity 3) portfolio content of learners in order to assess (polarity 4) in a structured (polarity 5) and data-driven (polarity 6) way. In contrast, striving for learner agency (polarity 1) will probably relate to coaching (polarity 3), reflection (polarity 4), personalisation (polarity 5) and intuitive knowing (polarity 6). The second polarity that focused on time constraints of portfolio use in a workplace setting was considered unrelated. However, given the interrelatedness, we expected that focusing on the first polarity could also inform us about the four polarities that can result from this overarching polarity.

Table 1. The list of possible polarities of multipurpose portfolio use in medical education that was proposed during the first step of the polarity map formulation.

The description of this overarching polarity in focuses on problems that can arise when accountability overshadows learner agency, as we had encountered this situation in our previous studies. In such a situation, portfolio requirements installed to ensure the portfolio’s value for accountability, restrict the (experienced) possibilities of learners to use the portfolio for their personal learning objectives. However, also the opposite situation might arise: portfolios that have no value for accountability, as personal choices of learners have resulted in a disparity of portfolio content. Given the importance of both poles of this polarity in medical training, we considered it important to explore possibilities to balance the polarity.

Step 2: mapping

We easily agreed on the values of both poles, as there was a high degree of similarity between the proposed values, e.g. (intrinsic) motivation was by most team members mentioned as a value of learner agency. Our proposals for the GPS were also similar, as everyone considered lifelong learning an important aspiration of balanced portfolio use. In contrast, the components on the bottom half of the polarity map required more extensive discussion, as the initial suggestions of the deeper fear and fears for both polarities were more varied. However, through discussion, we realised that these suggestions shared commonalities. For example, the following suggested fears of accountability,

Deliberate choice for performance assessment of what is already mastered,

Selective documentation,

Adding socially desirable portfolio content in order to meet external standards,

Avoidance of portfolio entries that are personal (and potentially meaningful),

were combined into the fear: learners only add portfolio content in order to meet external standards (tick-box exercise).

Our final version of the GPS, deeper fear, values and fears is shown in .

Step 3: tapping/leveraging

During the stakeholder session, it became clear that participants recognised the selected polarity and the proposed values and fears from their own experiences with the multipurpose portfolio of the GP speciality training.

The action steps and early warnings that were proposed by participants of the stakeholder session are presented at the centre of . While participants easily suggested possible action steps and early warnings, they often struggled to assign these to only one of the two poles of the polarity.

The adjustments that were made after the stakeholder session and were shared with participants are explained in the boxes surrounding the table in . While three participants replied that they agreed with the adjusted version of the polarity map, one faculty member responded specifically to the removal of the proposed early warning ‘there is little documentation in the portfolio’ by underlining that an empty portfolio could indicate all sorts of problems and was therefore interesting. Despite this response, we decided that no early warning would be included regarding the amount of documentation, the faculty member’s response did not refute the primary reason for removal by the research team (a lack of distinctiveness). The other participants did not reply to our invitation to comment on the adjusted version of the polarity map.

The final version of the action steps and early warnings is presented in .

Discussion

Multipurpose portfolios are implemented in medical education with the aim to support the qualification of competent, lifelong learning professionals. However, in educational practice, it appears difficult to combine multiple purposes in one portfolio, as different tensions undermine the portfolio’s potential. We identified accountability and learner agency as an overarching polarity that can explain various tensions related to multipurpose portfolio use. Using the polarity thinkingTM framework, we charted a polarity map, in order to clarify the polarity and provide concrete advice on how to manage tensions that result from this polarity.

Tensions related to multipurpose portfolio use have been discussed previously, in concern to the combination of (summative) assessment and reflection [Citation1,Citation7,Citation13–15]. Moreover, multiple fears described in our polarity map have been reported in studies that evaluated multipurpose portfolio use in medical education, thereby indicating imbalances between accountability and learner agency. Fears that indicate a focus on accountability at the cost of learner agency were reported most often: portfolio use as a tick-box exercise, motivational problems and/or stress and anxiety of learners [Citation10,Citation29–33]. However, also the opposite situation (learner agency overshadowing accountability) might occur, as studies discussed reliability and/or validity problems of portfolio assessment due to the disparity of portfolio content [Citation34,Citation35].

Given that multipurpose portfolios are an important component of medical curricula across the world, it is troublesome that intended purposes are often not met. As discussed, previously suggested solutions can add to imbalances between portfolio purposes, as they are usually focused on one of the purposes (e.g. rubrics that are intended to increase the interrater reliability of portfolio assessment) [Citation36]. It is time to consider solutions that fit the criteria of systems thinking methodologies.

Implications for practice

Many of the action steps included in our polarity map are similar to previous recommendations regarding portfolio use. In line with research literature that emphasises the importance of clear guidelines, participants of the stakeholder session formulated the action step ‘provide sufficient information on portfolio use’ [Citation5,Citation12,Citation37]. Furthermore, the literature stresses the importance of faculty development, which could be seen as a prerequisite for another action step ‘faculty actively engage with the portfolio and guide learners during the completion of learning cycles’ [Citation5,Citation13,Citation37]. Moreover, it is not surprising that action steps have been proposed considering the content (i.e. ‘provide portfolio tools that focus on an awareness of learning’), use (i.e. ‘evaluate competences periodically’) and technical aspects of the portfolio (‘provide the opportunity to deliver content in a personalised way that corresponds with clinical practice’) [Citation13,Citation37].

In addition, there is one action step unique to our polarity map: ‘acknowledge and discuss the tensions between accountability and learner agency’. We advocate that it is important that all stakeholders (e.g. learners, faculty, and curriculum coordinators) exchange information on the purposes, expectations and assessment of the multipurpose portfolio in use, in order to create a shared frame of reference between all involved. During this exchange, the focus should not be on isolated aspects (or problems) of the portfolio, but instead a holistic approach is needed, i.e. systems thinking.

In these implications, we would like to highlight an important concept related to systems thinking: continuous quality improvement [Citation23]. While (most of) abovementioned actions points will probably be considered during the introduction of a multipurpose portfolio, attention for the functioning often fades when the portfolio has become an established component of the training programme. At that point, imbalances between the different purposes, and therewith tensions, will often arise. Therefore, it is important that portfolio use is periodically evaluated. Evaluation should go beyond a strengths and weaknesses assessment, and the use of a comprehensive Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle is advised [Citation38]. During this process, the action steps and early warnings of our polarity map can be helpful.

In concern to the above, we think it is important to emphasise that the polarity between accountability and learner agency is not unique to portfolio use, as it has also been described in concern to other aspects of current medical training programmes [Citation38]. We have mentioned that medical training programmes are often defined by the use of CBE. While CBE is theoretically meant to be flexible and learner-centred, the outcome-oriented nature of CBE can also be seen as a fixed and prescriptive picture of how doctors should perform, think and act [Citation38,Citation39]. Another important component of many medical training programmes is programmatic assessment. While single assessments are intended to support learning, it has been reported that learners can also perceive these assessments to be high-stake (i.e. resulting in pass/fail decisions), which is stressful for learners and can reduce experienced learning opportunities [Citation40]. Considering that the polarity between accountability and learner agency can be fundamentally present in medical training programmes, one might wonder whether it is possible to balance the polarity by means of portfolio use only. Instead, it is probably necessary to embed the abovementioned suggestions in all aspects of the training programme [Citation41].

Strengths and limitations

Although tensions that can result from the use of multipurpose portfolios have been discussed previously [Citation5–7,Citation13], little guidance has been provided on how to adequately manage these tensions in educational practice. The polarity thinkingTM framework offered an approach that aligns with systems thinking and enabled the provision of concrete advice on how to deal with the complex problems related to multipurpose portfolio use.

However, the construction of a polarity map was also complex and possibilities to make alterations were limited due to the trademark agreement. Moreover, we considered one of the instructions regarding the formulation of the polarity map to be at odds with the principles of the polarity thinkingTM framework. The instructions specify that the values, fears, action steps and early warnings should be unique to one of the two poles. However, this seems to contradict the primary principles of the polarity thinkingTM framework that underlines the importance of interdependency between the two poles of a polarity. Consequently, it was difficult for participants of the stakeholder session to formulate action steps and early warnings that applied to one of the two poles only. Therefore, some suggestions were removed after the stakeholder session, as they were not considered distinctively related to one pole (e.g. accessibility of the portfolio). However, during later discussion of the polarity map, we realised that some of the action steps could be considered important to both poles (e.g. acknowledgement and discussion of tensions). Nevertheless, as we wanted to do justice to the suggestions resulting from the stakeholder session, we decided to make no further alterations to the polarity map than those shared with the participants directly after the session.

Finally, the inclusion of seven representatives related to the Dutch GP speciality programme summons us to mention that this is just one example of a polarity map on multipurpose portfolio use. The same exercise in other settings might provide different results.

Conclusions

Portfolio use in medical training has the potential to serve various purposes. However, in educational practice, it appears to be difficult to maintain a balance between the different purposes of a portfolio, as interrelatedness between the purposes can cause tensions. We considered accountability and learner agency as an important overarching polarity that can explain a multitude of tensions associated with portfolio use. Polarity thinkingTM enabled us to suggest action steps and early warnings that can help to balance accountability and learning agency. Most importantly, an awareness of the interdependency between this polarity is essential to support multiple purposes with one portfolio.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of the stakeholder session for their valuable contributions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tochel C, Haig A, Hesketh A, et al. The effectiveness of portfolios for post-graduate assessment and education: BEME Guide No 12. Med Teach. 2009;31(4):299–318. doi: 10.1080/01421590902883056

- Buckley S, Coleman J, Davison I, et al. The educational effects of portfolios on undergraduate student learning: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review BEME Guide No 11. Med Teach. 2009;31(4):282–298. doi: 10.1080/01421590902889897

- Frank JR, Mungroo R, Ahmad Y, et al. Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: a systematic review of published definitions. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):631–637. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.500898

- van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW. Assessing professional competence: from methods to programmes. Med Educ. 2005;39(3):309–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02094.x

- Van Tartwijk J, Driessen EW. Portfolios for assessment and learning: AMEE Guide no. 45. Med Teach. 2009;31(9):790–801. doi: 10.1080/01421590903139201

- Zimmerman BJ. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. Am Educ Res J. 2008;45(1):166–183. doi: 10.3102/0002831207312909

- McMullan M, Endacott R, Gray MA, et al. Portfolios and assessment of competence: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(3):283–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02528.x

- Snyder J, Lippincott A, Bower D. The inherent tensions in the multiple uses of portfolios in teacher education. Teach Educ Q. 1998;12:45–60.

- Tigelaar DE, Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen IH, et al. Using a conceptual framework and the opinions of portfolio experts to develop a teaching portfolio prototype. Stud Educ Eval. 2004;30(4):305–321. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2004.11.003

- Halder N, Subramanian G, Longson D. Trainees’ views of portfolios in psychiatry. The Psych. 2012;36(11):427–433. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.111.036681

- Brown JM, McNeill H, Shaw NJ. Triggers for reflection: exploring the act of written reflection and the hidden art of reflective practice in postgraduate medicine. Reflective Pract. 2013;14(6):755–765. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2013.815612

- Jenkins L, Mash B, Derese A. The national portfolio of learning for postgraduate family medicine training in South Africa: experiences of registrars and supervisors in clinical practice. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):149. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-149

- Driessen E, van Tartwijk J, van der Vleuten C, et al. Portfolios in medical education: why do they meet with mixed success? A systematic review. Med Educ. 2007;41(12):1224–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02944.x

- Plaza CM, Draugalis JR, Slack MK, et al. Use of reflective portfolios in health sciences education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2):1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9459(24)03323-0

- Heeneman S, Driessen EW. The use of a portfolio in postgraduate medical education–reflect, assess and account, one for each or all in one? GMS J Med Educ. 2017;34(5):Doc57. doi: 10.3205/zma001134

- Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 2009;31(8):685–695. doi: 10.1080/01421590903050374

- O’Connell TS, Dyment JE. The case of reflective journals: is the jury still out? Reflective Pract. 2011;12(1):47–59. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2011.541093

- Funke J. Complex problem solving: a case for complex cognition? Cogn Process. 2010;11(2):133–142. doi: 10.1007/s10339-009-0345-0

- Govaerts MJ, van der Vleuten CP, Holmboe ES. Managing tensions in assessment: moving beyond either–or thinking. Med Educ. 2019;53(1):64–75. doi: 10.1111/medu.13656

- Johnson B. Reflections: a perspective on paradox and its application to modern management. J Appl Behav Sci. 2014;50(2):206–212. doi: 10.1177/0021886314524909

- Khalil H, Lakhani A. Using systems thinking methodologies to address health care complexities and evidence implementation. JBI Evid Implement. 2022;20(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000303

- Driessen EW, van Tartwijk J, Overeem K, et al. Conditions for successful reflective use of portfolios in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2005;39(12):1230–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02337.x

- Woodruff JN. Accounting for complexity in medical education: a model of adaptive behaviour in medicine. Med Educ. 2019;53(9):861–873. doi: 10.1111/medu.13905

- van der Gulden R, Timmerman A, Muris JW, et al. How does portfolio use affect self-regulated learning in clinical workplace learning: what works, for whom, and in what contexts? Perspect Med Educ. 2022;11(5):1–11. doi: 10.1007/S40037-022-00727-7

- van der Gulden R, Heeneman S, Kramer A, et al. How is self-regulated learning documented in e-portfolios of trainees? A content analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02114-4

- van der Gulden R, Timmerman AA, Sagasser MH, et al. How does portfolio use support self-regulated learning during general practitioner specialty training? A qualitative focus group study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(2):e066879. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066879

- Polarity Partnerships [Internet]. Sacramento: Polarity Partnerships, LCC; 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 24] Available from: https://www.polaritypartnerships.com

- Nieminen JH, Tai J, Boud D, et al. Student agency in feedback: beyond the individual. Assess Eval High Educ. 2021;47(1):1–14. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2021.1887080

- Elango S, Jutti R, Lee L. Portfolio as a learning tool: students’ perspective. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2005;34(8):511–514.

- Hrisos S, Illing JC, Burford BC. Portfolio learning for foundation doctors: early feedback on its use in the clinical workplace. Med Educ. 2008;42(2):214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02960.x

- Belcher R, Jones A, Smith L-J, et al. Qualitative study of the impact of an authentic electronic portfolio in undergraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):265. doi: 10.1186/s12909-014-0265-2

- Vance GH, Burford B, Shapiro E, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of a pilot e-portfolio-based supervision programme for final year medical students: views of students, supervisors and new graduates. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0981-5

- Tailor A, Dubrey S, Das S. Opinions of the ePortfolio and workplace-based assessments: a survey of core medical trainees and their supervisors. Clin Med. 2014;14(5):510–516. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-5-510

- Pitts J, Coles C, Thomas P. Educational portfolios in the assessment of general practice trainers: reliability of assessors. Med Educ. 1999;33(7):515–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00445.x

- Roberts C, Newble DI, O’Rourke AJ. Portfolio-based assessments in medical education: are they valid and reliable for summative purposes? Med Educ. 2002;36(10):899–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01288.x

- O’Sullivan PS, Reckase MD, McClain T, et al. Demonstration of portfolios to assess competency of residents. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2004;9(4):309–323. doi: 10.1007/s10459-004-0885-0

- Van Tartwijk J, Driessen E, Van Der Vleuten C, et al. Factors influencing the successful introduction of portfolios. Qual High Educ. 2007;13(1):69–79. doi: 10.1080/13538320701272813

- Pietrzak M, Paliszkiewicz J. Framework of strategic learning: PDCA cycle. Management. 2015;10(2):149–161.

- Watling C, Ginsburg S, LaDonna K, et al. Going against the grain: an exploration of agency in medical learning. Med Educ. 2021;55(8):942–950. doi: 10.1111/medu.14532

- Frost HD, Regehr G. “I am a doctor”: negotiating the discourses of standardization and diversity in professional identity construction. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1570–1577. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a34b05

- Schut S, Maggio LA, Heeneman S, et al. Where the rubber meets the road - an integrative review of programmatic assessment in health care professions education. Perspect Med Educ. 2021;10(1):6–13. doi: 10.1007/s40037-020-00625-w