1. Introduction

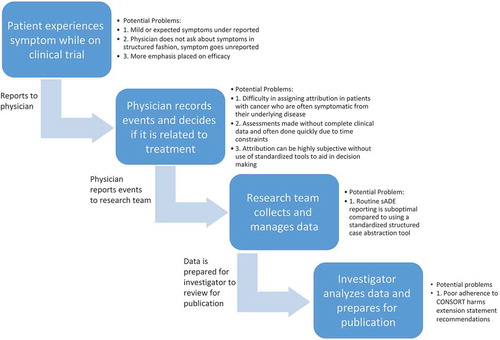

Appropriately conducted randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard of evidence development utilized to define therapeutic standards for human disease. Thus, complete and transparent reporting of clinical trial results is essential for not only determining which treatments may be most beneficial but also for defining the potential risks of treatment-related harms. The series of steps involved in adverse event reporting (), from the patient’s experience to the physician’s interpretation of that experience to the data coordinator’s abstraction of the source documents to the analyst’s synthesis of the data and finally the investigator’s reporting of that data, is like the game ‘telephone’, with plenty of opportunity for information to get lost in translation. Indeed, evidence suggests that physician-driven reporting of adverse events is inferior to a complementary approach using both patient- and physician-reported outcomes.[Citation1] Attribution of adverse events to therapies has been shown to be unreliable and there are few standards for structured data collection.[Citation2] Finally, peer-reviewed publications are the primary source from which clinicians obtain information regarding the results of RCTs; however, historical evidence suggests that harms are suboptimally reported in clinical trial publications.[Citation3] Analyses of nononcologic RCTs continue to demonstrate substantial heterogeneity in adverse event reporting.[Citation3] Recent studies have also explored adoption of harms reporting standards in oncology RCTs; herein, we review this literature, particularly focusing on the final step in the continuum, the actual reporting, and highlight the need for additional work and the establishment of standards in this area.

2. Patient-reported outcomes

Definitions to standardize both the type and severity of adverse events have been established through the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).[Citation4] A growing body of evidence suggest that physicians underestimate and underreport the severity and incidence of adverse events.[Citation5,Citation6] There are likely several factors that contribute to physicians’ underreporting of symptoms including less attention paid to mild or subjective toxicities, less attention paid to expected toxicities, increased attention paid to efficacy rather than adverse events, and inadequate and unstructured elicitation of all toxicities from patients.[Citation5,Citation7] Additionally, patient volume, physician time constraints, and limited resources for data management likely also contribute to underreporting of adverse events.[Citation7] Most patients, even those with late stage disease and poor performance status, are able and willing to characterize their own symptoms, and evidence also suggests improvement in characterization of baseline symptoms at trial entry when patients self-report.[Citation8,Citation9] As a result, the NCI has developed a Patient Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE), a standardized patient-centered method of adverse event reporting, that could be implemented in oncology trials to enhance and complement physician reporting of adverse events.[Citation10] Incorporation of such a tool into standard research data collection may overcome a key barrier and bring us closer to comprehensive adverse event reporting.

3. Data management

3.1. Attribution of adverse events

Assignment of attribution of adverse events is the responsibility of the treating investigator. Studies have demonstrated poor concordance between multiple physicians reviewing medical records to identify which adverse events were treatment related.[Citation11] Additionally, there is considerable heterogeneity in the categories of attribution used by trial sponsors despite the Common Toxicity Criteria recommendations and little standardization in attributing causality to adverse events. In a qualitative study evaluating causality attribution in early phase clinical trials, researchers found that clinicians described a logical method of assigning attribution but admit that these assessments are highly subjective without use of standardized tools to aid in decision-making. Clinicians also voiced that assessments were made without complete clinical data and were often done quickly due to time constraints. As a result, standardized tools for attributing adverse events are in development.[Citation12] Still, better standards for adverse event attribution through the development of standardized tools for assessing and assigning adverse events, and training of appropriate research personnel, may improve assessments of treatment-related versus disease-related signs and symptoms.

3.2. Data collection

Serious adverse drug events (sADE) are reviewed by the Institutional Review Board, Food and Drug Administration, and drug manufacturers. Studies have demonstrated that the current practice of routine sADE reporting is suboptimal compared to using a standardized structured case abstraction tool partly derived from the Naranjo instrument, a previously validated causality assessment instrument.[Citation2] Additionally, efforts are being made to develop adverse event capture and management systems within electronic health records so that data can be shared in a more efficient manner.[Citation13] Standardized, structured, easily accessible data collection and management strategies will aid in optimizing comprehensive adverse event data collection.

4. Evolution of the CONSORT harms statement

4.1. CONSORT harms extension statement recommendations

Prior to 1996, several analyses concluded that clinical trials were being reported in a nonuniform and often biased manner.[Citation14] Spurred on by these analyses, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement was developed to promote uniformity and transparency in clinical trial reporting. Notably, the original CONSORT statement did not include recommendations for reporting of treatment-related harms. However, the statement has been revised several times over the years to include basic recommendations on harms reporting. Given the lack of attention to harms reporting in the original CONSORT statement, an extension statement was published in 2004 comprising a 10-item checklist. These 10 items (), corresponding to specific items included in the original CONSORT checklist, are meant to enhance the quality of reporting harms data as well as balance reporting of efficacy versus safety data.[Citation15]

4.2. Adherence to individual CONSORT harms extension statement recommendations

Three systematic reviews derived a scoring system based on the CONSORT extension statement for harms to determine adherence to the individual elements as well completeness of reporting in oncology RCTs. Some elements of the CONSORT extension statement for harms were inadequately reported across all studies reviewed particularly with regards to collection and plans for presenting and analyzing harms ( – recommendations 3–5). Additionally, although deaths were consistently reported across all reviews, descriptions of these events were poorly reported ( – recommendation 6). There is also inconsistency in the threshold at which events are reported, whether all events are reported, and whether grades of varying toxicity were combined when reported ( – recommendation 8). Of concern is the lack of a balanced discussion of harms and benefits and the use of vague and subjective terminology ( – recommendation 10). Overall, all studies demonstrated suboptimal completeness in adverse event reporting.

Table 1. Elements of adverse event reporting[Citation16].

Although the number of points in each scoring system varied slightly, overall all three reviews found that the median completeness scores included just over half of the checklist items in each scoring system.[Citation17-Citation19]

The three reviews analyzed factors of published trials that may contribute to improved reporting. Peron et al. found, in multivariable analysis, a higher quality of reporting in trials that had industrial funding, were intercontinental trials, were conducted in the metastatic setting, and when the author provided a conclusion about the relative toxicity of the experimental arm.[Citation18] Sivendran et al. found a trend toward improved reporting with each subsequent publication year but no other significant factors suggesting that inadequacy of reporting is not limited to certain journal types or interventions.[Citation19] Chen et al. concluded that for immunotherapy trials there was higher quality of reporting in journals with higher impact factors and those published in the last 5 years in multivariable analysis.[Citation17] Across the three reviews, there were no consistent factors related to improved reporting suggesting that suboptimal completeness is a generalized issue and not specific to certain journals or intervention types.

5. Conclusion

Adverse event collection, abstraction, and reporting is a multistep process highly prone to allowing the patient’s experience to become lost in translation. Standards and guidelines for tabulation, attribution assessment, and reporting of harms are urgently needed, in addition to efforts to enforce such standards, to provide patients and physicians with the information needed to make critical treatment decisions.

6. Expert opinion

In the context of often modest benefits and narrow therapeutic indices, concerns have been raised regarding the adequacy of harms reporting from oncologic clinical trials. As the landscape of therapies in oncology expands, reducing variability in data collection and reporting as well as incorporating the patient voice through the PRO-CTCAE is critical in allowing physicians to accurately interpret toxicity data.

In this review, we have outlined the complex steps () required for adverse event reporting which lead to multiple opportunities for the patient’s experience to get ‘lost in translation.’ Coordinated efforts are underway to improve adverse event data collection, attribution, and accuracy through incorporating patient reported outcomes. However, without comprehensive standards developed specifically for oncology trials, the reporting of adverse event data will face limitations. The CONSORT harms extension statement represented a move in the right direction toward standardization. However, adherence to these guidelines has been variable likely for multiple reasons including lack of knowledge regarding the guidelines, lack of enforcement, and perhaps most importantly, that the guidelines focus largely on transparency of reporting rather than establishing standards to ensure consistency of data presentation across trials. There is an urgent need within the oncologic community for stakeholders to develop a standard approach to the analysis, synthesis, and reporting of clinical trial adverse event data.

Declaration of interests

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- Basch E, Iasonos A, McDonough T, et al. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: results of a questionnaire-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:903–909.

- Belknap SM, Georgopoulos CH, Lagman J, et al. Reporting of serious adverse events during cancer clinical trials to the institutional review board: an evaluation by the research on adverse drug events and reports (RADAR) project. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53:1334–1340.

- Ioannidis JP, Lau J. Completeness of safety reporting in randomized trials: an evaluation of 7 medical areas. JAMA. 2001;285:437–443.

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0 [Internet]. U.S. Department of health and human services, National Institutes of Health. [cited 2016 Mar 28]. Available from http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf

- Di Maio M, Gallo C, Leighl NB, et al. Symptomatic toxicities experienced during anticancer treatment: agreement between patient and physician reporting in three randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:910–915.

- Fromme EK, Eilers KM, Mori M, et al. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3485–3490.

- Montemurro F, Mittica G, Cagnazzo C, et al. Self-evaluation of adjuvant chemotherapy-related adverse effects by patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1–8. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4720. [Epub ahead of print]

- Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:865–869.

- Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, et al. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1624–1632.

- Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, et al. Development of the National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(9):dju244.

- Thomas EJ, Lipsitz SR, Studdert DM, et al. The reliability of medical record review for estimating adverse event rates. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:812–816.

- Mukherjee SD, Coombes ME, Levine M, et al. A qualitative study evaluating causality attribution for serious adverse events during early phase oncology clinical trials. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:1013–1020.

- Lencioni A, Hutchins L, Annis S, et al. An adverse event capture and management system for cancer studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16(Suppl 13):S6.

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, et al. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408–412.

- Mucklow JC. Reporting drug safety in clinical trials: getting the emphasis right. The Lancet. 2001;357:1384.

- Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gotzsche PC, et al. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:781–788.

- Chen TW, Razak AR, Bedard PL, et al. A systematic review of immune-related adverse event reporting in clinical trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1824–1829.

- Péron J, Maillet D, Gan HK, et al. Adherence to CONSORT adverse event reporting guidelines in randomized clinical trials evaluating systemic cancer therapy: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3957–3963.

- Sivendran S, Latif A, McBride RB, et al. Adverse event reporting in cancer clinical trial publications. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:83–89.