ABSTRACT

Background: Inconsistencies in information on safety of medicine use during pregnancy and lactation can result in sub-optimal treatment for pregnant and lactating women, risks to the fetus or child and unnecessary weaning off breastfeeding. The objective of this study was to analyze information discrepancies regarding medicine use during pregnancy and lactation between on-line sources for patients and health care professionals (HCPs) in four European languages.

Research design and methods: The medicines analyzed were ibuprofen, ondansetron, olanzapine, fingolimod, methylphenidate and adalimumab. Recommendations were classified into different data source categories, for patients and for HCPs, and compared between the data source categories for each medicine and language.

Results: For patients, 11/24 (46%) and 4/24 (17%) comparisons of the pregnancy and lactation recommendations, respectively, were consistent between all sources. The corresponding figures for HCP-sources were 13/24 (54%) and 5/24 (21%). Regulatory sources had generally more restrictive recommendations. Teratology Information Services (TIS) centers’ recommendations for medicine use during pregnancy and lactation were consistent in 25/27 (93%) and 15/22 (68%) of cases respectively.

Conclusion: Discrepancies between online information sources regarding medicine use during pregnancy and lactation are common, especially for lactation. TIS centers recommendations were more aligned. Additional work is needed to harmonize information within and between countries to avoid conflicting messages.

1. Introduction

Consistent, adequate information on the safety of medicine use in pregnancy and lactation is important for women’s therapeutic decision making. In a multinational study, more than 80% of pregnant women reported using multiple information sources on medicine use during pregnancy. Many used both formal sources, e.g. advice from physicians or patient information leaflets (PILs), and informal sources such as family and friends [Citation1]. The majority of pregnant women search the internet for information on medicines [Citation1,Citation2]. Health service sites were most commonly used and deemed to be the most ‘helpful and trusted’ in a British study [Citation2].

Health care professionals (HCPs) appear to largely use the manufacturer’s prescribing information [Citation3] or drug formularies, for example the Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas in the Netherlands. Health care professionals and pharmacists also often use the internet to find scientific evidence and consensus reports regarding medicines during pregnancy [Citation4].

Some countries offer Teratology Information Services (TIS) which counsel HCPs and the public on the safety of medicines related to pregnancy and lactation, via for example telephone, chat [Citation5–7], or written information, sometimes via national knowledge databases [Citation8]. Other available information sources for HCPs are Pharmacovigilance or Drug information centers. These specialized services are independent from the manufacturer or medicine regulatory agencies and run by government funded health care institutions, health authorities or nonprofit organizations. They are however not available in all countries and are not always widely known.

With an increasing number of information sources, there is an increased risk that the information will vary or even conflict [Citation1,Citation3,Citation9–13], especially when using information from non-formal data sources. It has been previously shown that these information sources are often unreliable and lack evidence to support their conclusions [Citation11–13]. This may cause uncertainty about whether or not to use a medicine, resulting in more anxiety, non-adherence to essential therapy [Citation1] or even terminations of pregnancies [Citation14]. It might also result in inappropriate prescribing to pregnant and breastfeeding women which could expose the fetuses, the newborn or breastfed children to risks. Furthermore, it may result in unnecessary weaning off breastfeeding [Citation10].

The aim of this study was to analyze the frequency and nature of discrepancies between online information sources for patients and HCPs in four European languages. Knowing that pregnant and lactating women can rely on both formal and non-formal sources we have included both types of data sources in our analysis of patient’s discrepancies. The study was conducted within the scope of the IMI (Innovative Medicines Initiative) ConcePTION project, a public-private partnership, with the aim to improve information on safety of medicine use during pregnancy and breastfeeding (www.imi-conception.eu).

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of medicines

The selection criteria were a) medicines used for common acute illnesses experienced during pregnancy and lactation and b) medicines used for chronic diseases in the reproductive age.

Based on these criteria, the medicines analyzed were ibuprofen, ondansetron, olanzapine, fingolimod, methylphenidate and adalimumab. Details on the main indications and selection criteria of each medicine are provided in Table S1.

2.2. Selection of data sources and search strategy

The study was performed via internet data sources in Swedish, Dutch, French, and English. For the patient information, a first investigational step was conducted by searching the internet to find information sources on medicine use during pregnancy and lactation that are frequently appearing via google search. The purpose was to identify sources that pregnant or breastfeeding women would find when searching information independently. Based on these results the following data source categories were defined i) Regulatory sources, mostly the Patient Information Leaflet (PIL) approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) or a national Medicines Agency ii) Scientific sources, e.g. TIS/national knowledge databases and drug formularies iii) Blogs/forums/social media iv) News articles and v) Commercial websites for patients.

The PIL and information from the TIS/national knowledge databases were always included in the analyses irrespective of whether they appeared among the top searches or not, since they were considered as essential sources for the comparisons. The reason for this is that the PIL – which provides detailed descriptions of the medicine for lay people – is included in all medicine packages and is available online, and that the TIS/national knowledge databases are nonprofit services and provide information from experts independent from the manufacturer and regulatory procedures.

For the other data sources, standardized google searches were performed in the respective language for each medicine: i) generic medicine name + pregnancy ii) generic name + breastfeeding iii) most well-known brand name + pregnancy and iv) most well-known brand name + breastfeeding. The brand name, usually the original drug product, was selected by professionals from the study group who are familiar with the brands in the respective country. The top search hit within each data source category with enough information to allow the evaluation of the content was then selected, provided that it appeared among the top 10 search hits on google overall.

For Swedish, French and Dutch, only national data sources from Sweden, France and the Netherlands were used. For English, we used data sources from the United Kingdom (UK), but additionally some data sources from the United States (US), because they appeared high up among the top 10 search results. However, the regulatory sources used in English were approved for the UK. For a detailed overview of the included patient data sources, see Table S2.

For HCPs, the data source categories were chosen based on experience within the study group members, consisting of pharmacists and physicians working on benefit-risk evaluation and medical information within TIS centers and pharmaceutical companies. The following data source categories were identified as the most important and/or most used information sources in the respective language: i) Regulatory sources: Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC), approved by the EMA or a national Medicines Agency ii) Drug formularies, if available (drug formularies are descriptions of different drug products including prescribing information, frequently used by HCPs at the point of care, and provided by e.g. specialist medical/pharmaceutical associations) iii) Scientific sources: TIS information/national knowledge databases iv) Treatment guidelines and v) Main national medical journals.

Information from the selected sources were included, irrespective of whether they appeared among the top 10 searches via Google or not. Only national data sources from Sweden, France, the Netherlands and the UK were used for HCPs. Several of the data sources were not publicly available but accessible for HCPs using their professional credentials. Details of the HCP data sources are presented in Table S3.

2.3. Classification of recommendations

From each data source, recommendations concerning treatment during pregnancy and lactation were collected for the six medicines and classified into the following six categories ‘Can be used’; ‘Individual benefit-risk assessment’; ‘Should not be used’; ‘Trimester specific information’ (for pregnancy recommendations), ‘Not classifiable’; ‘No available information’, based on a previously settled categories by Frost-Widnes [Citation9]. The descriptions of each category were then detailed () to ensure consistent categorization of the recommendations by the team.

Table 1. Description of the recommendation categories

The distribution of the pregnancy and lactation recommendations categories were analyzed for differences between medicines, languages and types of information sources.

2.4. Classification of discrepancies

To classify the discrepancies, the collected recommendation categories above were compared for each medicine and each language. The following discrepancy classes by Brown [Citation3] were used:

1. SmPC/PIL agrees with all other sources, 2. SmPC/PIL has different recommendations from other information sources but those other sources are in agreement (2.a. SmPC/PIL is most conservative (more restrictive), 2.b. SmPC/PIL is least conservative + which source/s is more conservative in free text), 3. One or more of the non-SmPC/PIL sources has a recommendation different from the others (+ which resource/s contained the most and the least conservative statement/s in free text), 4. Unclassifiable: Information unable to be categorized within the above three categories.

Recommendations that were not classifiable and sources with no available information were excluded from the discrepancy analysis.

2.5. Detailed analyses of discrepancies

To explore discrepancies in more detail, recommendations from selected data sources were compared with each other for each medicine. First, totally divergent recommendations defined as recommendations differing from ‘Can be used’ in one source to ‘Should not be used’ in another source, for the same medicine and language, were analyzed to see whether the discrepancies were completely contradictory and whether some resource categories were more restrictive than others.

In a second analysis, the SmPC information was compared to the drug formularies for the HCP data sources. Sweden and France were excluded from these analyses, since the Swedish drug formulary is completely based on the SmPC and no corresponding drug formulary is available in France.

Further, the TIS information for both patients and HCPs were compared between the different languages. Patients’ information in the PIL and news articles were also compared with the TIS information. The TIS information was considered as a reference, since it is produced by independent experts within the field. Finally, the PIL recommendations were compared between the different languages.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to identify the frequency and nature of the discrepancies

3. Results

In total, the searches yielded 249 pregnancy and lactation recommendations from the patient sources and 185 recommendations from HCP sources. An overview is presented in Supplementary Table S4. It should be noted that pregnancy and lactation recommendations were not available for each medicine in all data sources and all languages.

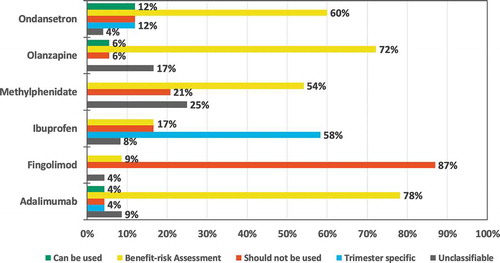

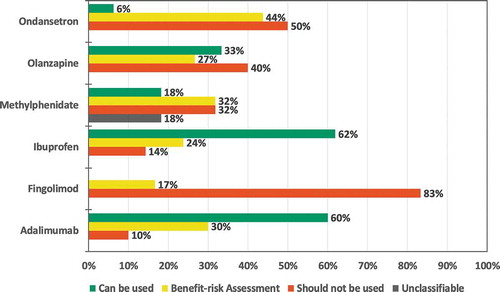

3.1. Distribution of pregnancy and lactation recommendations

There was more homogeneity between data sources regarding the recommendation of use during pregnancy than regarding use during lactation for all medicines except ibuprofen in patient data sources ( and ) and for ondansetron in HCP data sources (Supplementary Figure S1 and S2). Additional details, e.g. distribution of recommendations by type of data source category for the patient information are available in Supplementary Table S5. A significant proportion of the information from social media was not classifiable since different posts provided conflicting statements (Supplementary Table S5).

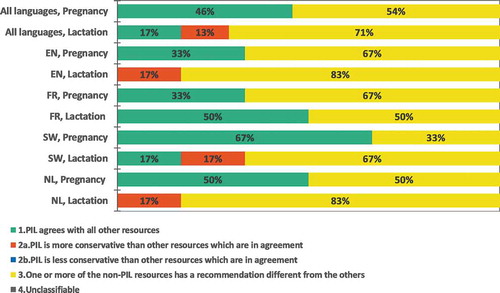

3.2. Discrepancy analysis

For all languages and medicines, 24 pregnancy and 24 lactation discrepancy comparisons were undertaken for both patient and HCP data sources. In the patient data sources, 15 (31%) corresponded to consistent recommendations in all data sources (category 1): 46% for pregnancy recommendation and 17% for lactation recommendation (). The Swedish pregnancy recommendations showed the most consistency between data sources: 4 out of 6 medicines (67%) had consistent recommendations in all data sources (category 1). The least consistent recommendations were found for lactation in English and Dutch sources, where no medicine had consistent recommendations in all data sources (category 2a and 3).

In the HCP data sources, 18 (38%) corresponded to consistent recommendations in all data sources (category 1): 54% of the pregnancy and 21% of the lactation comparisons (Supplementary Figure S3). Swedish and English pregnancy recommendations showed the most consistency: 4 out of 6 (67%) medicines had uniform recommendations in all data sources (category 1). The least consistent recommendations were found for lactation in English, Dutch and Swedish, 1 out of 6 (17%) of the medicines had consistent recommendations between the data sources (category 1).

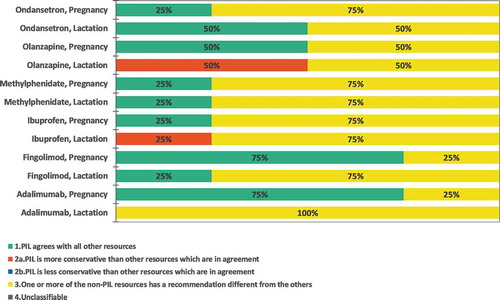

Regarding the individual medicines, none had consistent recommendations in all languages in the patient data sources (). In the HCP data sources, pregnancy recommendations were consistent in all data sources for fingolimod, while inconsistences were found for all other medicines (Supplementary Fig S4).

3.3. Detailed analysis of discrepancies

3.3.1. Medicines with totally divergent recommendations

Among the 48 comparisons in patient data sources, 11 (23%) (13% for pregnancy recommendations and 33% for lactation recommendations) included a totally divergent recommendation between different data sources. For pregnancy, totally divergent recommendations were seen for ondansetron and adalimumab (Supplementary Table S6). For lactation, totally divergent recommendations were seen for olanzapine, adalimumab, ondansetron, ibuprofen and methylphenidate (Supplementary Table S6). Differences between the PIL and a forum discussion (social media) or a scientific data source, were common reasons for the deviations, PIL being more restrictive in these cases.

For the HCPs, 6 were totally divergent (13%). All concerned lactation recommendations for olanzapine, ibuprofen, methylphenidate and adalimumab (Supplementary Table S7). For all medicines except for adalimumab, the discrepancies were partly due to the SmPC being more restrictive than information from at least one other data source (frequently the TIS information).

3.3.2. Comparing Summary of Product Characteristics with drug formularies

Overall, 30 (83%) out of the 36 compared recommendations were consistent (88% and 78% for pregnancy and lactation recommendations, respectively). In the UK, the SmPC and the drug formulary were always consistent, while in the Netherlands, the SmPC differed from one of the two the drug formularies in 6/24 (25%) of the comparisons. For the pregnancy recommendations, the Dutch SmPC for ondansetron was more restrictive than the Dutch drug formulary for physicians, whereas the SmPC for methylphenidate was less restrictive than the Dutch drug formulary for pharmacists. For lactation recommendations, the Dutch SmPC was more restrictive than the Drug formulary for pharmacists for fingolimod, olanzapine, ondansetron and methylphenidate. No discrepancy was totally divergent.

3.3.3. Comparing Teratology Information Services’ recommendations between languages

There was a limited number of discrepancies between the TIS/national knowledge database recommendations for patients and HCPs in different languages. For the pregnancy recommendations, 25/27 (93%) and 20/22 (91%) were similar for patients and HCPs respectively. None was totally divergent.

For lactation, 15/22 (68%) and 14/23 (61%) of the recommendations were similar for patients and HCPs, respectively. One lactation recommendation was totally divergent: methylphenidate ranged from ‘Can be used’ in Swedish and in one of the two TIS recommendations in English (US: Mother to Baby) to ‘Should not be used’ in French (Supplementary Table S8).

3.3.4. Comparing Patient Information Leaflets with Teratology Information Services

The PIL pregnancy recommendations were frequently consistent with those of the TIS 18/22 (82%), while there were significant inconsistencies between the PIL and TIS lactation recommendations, only 7/14 (41%) agreed. When discrepancies were found, the PIL was more restrictive in all cases, except for adalimumab in the Swedish lactation recommendations.

3.3.5. Comparing Patient Information Leaflets between languages

As expected, the 3 EU-centrally approved products, i.e. adalimumab, fingolimod, and olanzapine, were consistent in all languages. Discrepancies were however noted across languages between the PILs for nationally approved products. For methylphenidate and ibuprofen, the lactation recommendation varied from ‘Should not be used’ in one language versus ‘Benefit Risk Assessment’ in all other languages. For ondansetron, the pregnancy recommendation varied between ‘Should not be used’, ‘Trimester specific’ and ‘Individual Benefit Risk Assessment’ in different languages. For lactation it varied between ‘Should not be used’ and ‘Individual Benefit Risk assessment’.

3.3.6. Comparing news articles with Teratology Information Services

For pregnancy, 7/11 (64%) of the recommendations were consistent between the news articles and the TIS. In 2/11 (18%) the news articles had more restrictive recommendations, both regarding the use of ibuprofen, and in 2/11 (18%) the TIS had more restrictive recommendations, one for ibuprofen and one for ondansetron.

For lactation, only 4 recommendations were comparable. Of these, 3/4 (75%) were consistent between the two information sources, and in 1/4 (25%) the TIS had more restrictive recommendations (adalimumab).

4. Discussion

This analysis aimed to describe the frequency and nature of discrepancies between different online information sources for patients and HCPs in four European languages. The results show that inconsistencies regarding pregnancy and lactation recommendations are common, with only 31% and 38% of the comparisons being consistent in patients’ and HCPs’ data sources respectively. The differences in recommendations were also frequently highly contradictory, i.e. one source stating that a medicine can be used and another source that it should not be used.

One reason for the higher discrepancy between data sources for patients might be that we included both formal and non-formal sources, since in a real word setting many pregnant and lactating women would use both these data sources while searching information on the safety of medicine use. However, the significant discrepancies also between HCPs’ data sources are especially noteworthy since this analysis only included highly credible data sources. The inconsistencies between the drug formularies for pharmacists and physicians are unfortunate, since different categories of HCPs might rely on contradictory information when counseling the same woman.

For the majority of selected medicines there was more homogeneity between data sources regarding pregnancy than lactation recommendations. For pregnancy recommendations, 46% and 54% were consistent in patients and HCPs’ data sources respectively versus 17% and 21% for lactation recommendations. One explanation might be differences in lactation cultures and national lactation plans between countries [Citation15]. Even though these national plans and general lactation culture do not address safety of medicines during breastfeeding, they might have an impact on medicine use as well. Furthermore, medicine exposure during lactation is avoidable to a higher extent than during pregnancy, which might contribute to some sources being more restrictive regarding medicine use during breastfeeding. Online information concerning medicines and lactation is overall sparser and more difficult to find than for pregnancy. Lack of data complicate the risk assessments, which might be another reason for the differences in lactation recommendations.

The information discrepancies varied by languages and by the selected medicines in the analysis. Even though it is probably most common to search in a local language, some women might search for information in other languages. Therefore, discrepancies between different languages and countries may cause further confusion.

There was good consistency for fingolimod and adalimumab pregnancy recommendations. Both are centrally authorized medicines by the EMA, and thereby the regulatory information was consistent between the countries, which might promote more consistent information than in other data sources. Compared to the other medicines in our study, fingolimod was more recently introduced to the market and is clearly contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation from the manufacturer, which probably adds to the fact that most data sources correspond to the labeled information. In addition, the EMA had issued updated restrictions for the use of the medicine in pregnancy a few months before this analysis was conducted [Citation16].

At the time of the study, the EMA had announced a warning for using ondansetron during early pregnancy due to a potential link to orofacial clefts [Citation17]. This was probably a reason for the inconsistencies in pregnancy recommendations for ondansetron, since some recommendations were published before this announcement. Secondly, this warning was debated and scientific sources like the TIS centers did not agree with the EMA recommendation and had consistently less restrictive recommendations for ondansetron use than the PIL/SmPC.

Comparison of TIS/national knowledge database information for HCPs and patients showed that there was good consistency between languages regarding pregnancy recommendations (93% and 91% of consistency between patients and HCPs data sources respectively) with no medicine having totally divergent recommendations. However, there is still room for improvement when it comes to lactation recommendations (68% and 61% of lactation recommendations were consistent in patients’ and HCPs’ data sources, respectively). Even though there are some discrepancies for lactation between the TIS centers, the information from these specialists is generally in agreement.

Regulatory sources tended to be more restrictive than other data sources. For example, there was good consistency between TIS and PIL pregnancy recommendations, but worse for lactation recommendations, with PIL being generally more restrictive. The same tendency was seen in our analysis of medicines with totally divergent recommendations where the regulatory recommendations were generally more restrictive. This is in accordance with the Australian study by Brown et al [Citation3], which showed that discrepancies frequently occur between the Australian Prescribing Information and Australian and international clinical sources. The same was demonstrated in the Norwegian study by Frost Widnes et al, where the Norwegian Pharmaceutical Product Compendium (Felleskatalogen) was commonly more restrictive than advice from the drug information centers [Citation9].

Whilst a more restrictive approach may be necessary based on available data, it can leave the HCP and patient without the optimal information in a given situation. Also, there is a considerable risk that women resort to single case reports/blogs/social media or other untrustworthy sources. It has been indicated in previous studies that many posts on social media provide inaccurate evidence, especially for medicines that should only be used on a strict or second-line indication [Citation11,Citation13]. Another study found that 42% of medicines classified as safe on different internet sites, were not safe according to the Teratogen Information System (TERIS) classification [Citation18].

To avoid non-adherence to therapy [Citation1] and other negative effects due to conflicting information, pregnant/lactating women and HCPs should be encouraged to use well-grounded and updated sources produced by experts in the field, such as TIS centers or independent knowledge databases. If women are in doubt whether to use a medicine, it is obviously important that they have the possibility to discuss any online advice that they discover with a medical professional. This is especially true for chronic diseases where treatment may be essential. Preferably, patients and HCPs should use the same information source so that they will receive uniform messages. Our results indicate that the recommendation categories can vary considerably between patient and HCP data sources. A specific example was a news article in a Swedish tabloid stating that ibuprofen should not be used during early pregnancy due to risks of fetal cardiac malformations and miscarriage whilst the HCP data sources recommended that a benefit risk assessment should be undertaken regarding the use of ibuprofen during early pregnancy.

It would also be advantageous if regulatory sources provide updated and detailed information in the SmPC and PIL in a timely fashion. However, this could be challenging since regulatory changes in SmPCs/PILs currently take a protracted period of time. Therefore, it is especially important that TISs and other credible sources provide current information while regulatory updates are awaited. Independent sources like the TIS centers and knowledge databases additionally take the information needs from a clinical perspective into account, which has not historically always been the case with the information in the SmPC/PIL.

A working procedure where TIS centers collaborate could potentially save resources and time and reduce the risk of conflicting messages. The TIS centers should preferably work together with national stakeholders to harmonize information also within the respective countries. Currently, a common European knowledge bank produced by experts from several countries and TIS centers is under development within the IMI ConcePTION project to improve the situation. This approach will provide women in countries lacking TIS centers and other specialized information sources with reliable information regarding medicine use during pregnancy and lactation. Additional efforts should also focus on ensuring that this European knowledge bank is known among HCPs and patients and that other information sources will rely on it to provide consistent high-quality recommendations.

This study has its limitations. Firstly, pregnancy and lactation recommendations were not available in every data source category for every medicine, resulting in potential bias in the analysis where all data sources for all medicines were compared. Some data sources might have focused more on medicines that have been linked to a negative impact on the fetus or breastfed child. This bias was however addressed in the detailed analysis where recommendations were compared between different data sources for the same medicine in the same language. Secondly, in the majority of cases, no clear recommendations could be concluded from social media discussions, and therefore, their recommendations were frequently categorized as not classifiable. Thirdly, selected medicines for the analysis were partly medicines for which risk assessments are complicated, which could therefore limit the representativeness and generalization of the study results.

To our knowledge, our study is one of the few published studies [Citation1,Citation10] analyzing information discrepancies between different languages and data sources. Most of the available previous studies focused on discrepancy analysis between data sources within one country or language. Overall, our results with substantial discrepancies between different online data sources are in line with previous research. They further emphasize the importance of increasing the availability of reliable, consistent information to enable women to receive as safe medicine treatment as possible during this period of life.

5. Conclusion

There are significant discrepancies between online information sources for both patients and health care professionals concerning medicine use during pregnancy and lactation. These discrepancies are also seen between languages. To ensure the health of the mother, fetus and breastfed child, it is crucial to provide women in the reproductive age with consistent and evidence-based information. A common European knowledge bank produced by experts from several countries and TIS centers is therefore under development within the IMI ConcePTION project to facilitate access to harmonized, scientifically based and updated information.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

The results concerning information in patient data sources in this study have previously been presented as a poster at the ICPE all access conference: Sep 16-17, 2020 in Berlin, Germany and as an abstract at the 31st ENTIS conference (published in Reprod.Toxicol. 2020;97:11). The data regarding information in data sources for health care professionals have not been presented before nor simultaneously submitted to any other journal.

Author contributions

Ulrika Nörby, Ludivine Douarin, Benedikte-Noël Cuppers, Sashka Hristoskova, Monali Desai, Linda Härmark and Michael Steel planned and designed the study. Ulrika Nörby, Benedikte-Noël Cuppers, Ludivine Douarin, Sashka Hristoskova, Chantal El-Haddad and Monali Desai, collected and analyzed the data. Ulrika Nörby and Chantal El-Haddad drafted the initial manuscript. All authors critically reviewed, and revised the manuscript and approved the final version as submitted. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Declaration of interest

S Hristoskova is an employee and shareholder in Novartis Pharma AG and shareholder in Alcon. M Steel is an employee and shareholder in Novartis Pharma AG. C El-Haddad is an employee of Excelya working as a contractor for Sanofi. L Douarin is an employee and shareholder in Sanofi. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Online_information_discrepancies_supplement_R2.docx

Download MS Word (302 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2021.1935865.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hämeen-Anttila K, Nordeng H, Kok ki E, et al., Multiple Information sources and consequences of conflicting information about medicine use during pregnancy: a multinational internet-based survey. J Med Internet Res. 16(2): e60. 2014.

- Sinclair M, Lagan BM, Dolk H, et al. An assessment of pregnant women’s knowledge and use of the internet for medication safety information and purchase. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:137–147. .

- Brown E, Hotham E, Hotham N. Pregnancy and lactation advice: how does Australian product information compare with established information resources? Obstet Med. 2016;9:130.

- Ververs T, van Dijk L, Yousofi S, et al. Depression during pregnancy: views on antidepressant use and information sources of general practitioners and pharmacists. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009 july 17;9:119. .

- Schaefer C, Hannemann D, Meister R. Post-marketing surveillance system for drugs in pregnancy—15 years experience of ENTIS. Reprod Toxicol. 2005;20:331–343.

- Hancock RL, Koren G, Einarson A, et al. The effectiveness of Teratology Information Services (TIS). Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23:125–132.

- Clementi M, Di Gianantonio E, Ornoy A. Teratology information services in Europe and their contribution to the prevention of congenital anomalies. Community Genet. 2002;5:8–12.

- Nörby U, Källén K, Eiermann B, et al. Drugs and Birth Defects: a knowledge database providing risk assessments based on national health registers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:889–899.

- Frost Widnes SK, Schjøtt J. Advice on drug safety in pregnancy: are there differences between commonly used sources of information? Drug Saf. 2008;31:799–806. .

- Warrer P, Aagaard L, Hansen EH. Comparison of pregnancy and lactation labeling for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder drugs marketed in Australia, the USA, Denmark, and the UK. Drug Saf. 2014;37:805–813.

- Gelder MMHJ, Rog A, Bredie SJH, et al. Social media monitoring on the perceived safety of medication use during pregnancy: a case study from the Netherlands. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2580–2590. .

- Hansen C, Interrante JD, Ailes EC, et al. Assessment of YouTube videos as a source of information on medication use in pregnancy: youTube videos on medication use in pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25:35–44.

- Palosse-Cantaloube L, Lacroix I, Rousseau V, et al. Analysis of chats on French internet forums about drugs and pregnancy: drugs and pregnancy related online conversations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:1330–1333.

- Walfisch A, Sermer C, Matok I, et al. Perception of teratogenic risk and the rated likelihood of pregnancy termination: association with maternal depression. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56:761–767.

- Theurich MA, Davanzo R, Busck-Rasmussen M, et al. Breastfeeding rates and programs in europe: a survey of 11 national breastfeeding committees and representatives. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68:400–407.

- Czarska-Thorley D. Updated restrictions for Gilenya: multiple sclerosis medicine not to be used in pregnancy [Internet]. Eur Med Agency 2019. Accessed 2020 May 29. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/updated-restrictions-gilenya-multiple-sclerosis-medicine-not-be-used-pregnancy

- Michie LA, Hodson KK. Ondansetron for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: re-evaluating the teratogenic risk. Obstet Med. 2020;13:3–4.

- Peters SL, Lind JN, Humphrey JR, et al. Safe lists for medications in pregnancy: inadequate evidence base and inconsistent guidance from web-based information, 2011: web safe lists for medications in pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:324–328.