ABSTRACT

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a concern as this increases morbidity, mortality, and costs, with sub-Saharan Africa having the highest rates globally. Concerns with rising AMR have resulted in international, Pan-African, and country activities including the development of national action plans (NAPs). However, there is variable implementation across Africa with key challenges persisting.

Areas covered

Consequently, there is an urgent need to document current NAP activities and challenges across sub-Saharan Africa to provide future guidance. This builds on a narrative review of the literature.

Expert Opinion

All surveyed sub-Saharan African countries have developed their NAPs; however, there is variable implementation. Countries including Botswana and Namibia are yet to officially launch their NAPs with Eswatini only recently launching its NAP. Cameroon is further ahead with its NAP than these countries; though there are concerns with implementation. South Africa appears to have made the greatest strides with implementing its NAP including regular monitoring of activities and instigation of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Key challenges remain across Africa. These include available personnel, expertise, capacity, and resources to undertake agreed NAP activities including active surveillance, lack of focal points to drive NAPs, and competing demands and priorities including among donors. These challenges are being addressed, with further co-ordinated efforts needed to reduce AMR.

1. Background

1.1. General overview including antimicrobial resistance

The greatest burden of infectious diseases globally, including acute respiratory diseases, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), malaria, and tuberculosis (TB), is in sub-Saharan Africa [Citation1–5]. Currently, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and TB account for over 1.2 million deaths per year across countries principally within sub-Saharan Africa [Citation1]. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) adds to this burden in a region with already inequitable access to essential medicines [Citation6]. A recent study published in the Lancet estimated that 1.27 million deaths globally in 2019 were due to bacterial AMR, with the greatest burden in Western sub-Saharan Africa with Australasia having the least number of deaths due to AMR [Citation6]. The COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated the burden of infectious diseases and antimicrobial use across sub-Saharan Africa; however to date, its perceived impact on morbidity and mortality appears to be less than for other endemic diseases including HIV/AIDS, malaria, and TB [Citation2,Citation7].

Challenges with health system infrastructure across sub-Saharan Africa, including regular access to clean water and good sanitation, exacerbated by poverty, coupled with the endemicity of HIV/AIDS, enhance the risk of infection and subsequent AMR [Citation6,Citation8–11], with COVID-19 further compromising healthcare infrastructures. The high rates of resistance to commonly prescribed and dispensed antibiotics across sub-Saharan Africa are further worsened by high rates of inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antimicrobials, weak diagnostic capabilities, variable implementation of regulations concerning the dispensing of antimicrobials without a prescription as well as variable access to effective health care [Citation5,Citation6,Citation8,Citation12–21].

Other compounding factors that add to the challenges of rising AMR rates in sub-Saharan Africa include the availability of substandard or falsified antibiotics. This arises from currently weak regulatory systems, limited local manufacturing, and inadequate quality assurance testing of antimicrobials, as well as concerns with available professionals and co-operation between professional groups [Citation1,Citation22–26]. Concerns about the impact of substandard and falsified medicines in Africa resulted in the recent Lomé Initiative organized by the World Health Organization (WHO) [Citation27,Citation28]. This strategy included 12 actions, ranging from education to border control as well as from supply chain integrity to transparent legal processes. Two of the 12 suggested actions in the WHO’s strategy relate to tightening of the legal frameworks to curtail this vice. The Lomé initiative has helped raise the priority for activities in this area as one of the key ways to reduce rising AMR rates [Citation28], which will continue. This is important as there have been shortages of quality medicines across Africa in recent years including antimicrobials. Shortages also carry with them the potential to increase AMR unless proactively addressed through improved stock control, donor schemes, and agreed therapeutic interchange programs [Citation29–32]. Concerns with shortages and their implications are likely to remain until there are sufficient structures in place to strengthen pharmaceutical supply chains across Africa [Citation29,Citation33,Citation34].

Vaccines are also a key preventative measure to limit future infectious diseases and any subsequent inappropriate antimicrobial use with implications for the development of AMR [Citation35–42]. Vaccines are also less likely to induce resistance [Citation42]. However, there are concerns with current vaccination uptake and coverage against infectious diseases among African countries, which are affected by available facilities for their administration and poor communication, both of which can be addressed [Citation43,Citation44]. This is a critical issue with the role of vaccines generally undervalued across countries to counteract AMR [Citation41]. Immunization rates across Africa have been further affected by lockdown and other measures to combat the spread of COVID-19 as well as fears of contracting the virus at primary healthcare facilities [Citation35,Citation45–50]. This is a concern given the implications for future morbidity and mortality among children, which are appreciably greater than the impact of COVID-19 among children across Africa [Citation45,Citation47,Citation51]. In some countries, mobile clinics, as well as healthcare workers visiting families with unvaccinated children, have been instigated to address these issues [Citation52,Citation53], with such activities likely to grow. Alongside this, there is also a need to increase educational and other activities to address concerns with vaccine hesitancy, including for COVID-19, to reduce the subsequent occurrence of infectious diseases and AMR [Citation35,Citation54–57].

Additional activities to reduce AMR rates across Africa include ensuring that pertinent quality improvement programs are instigated across sectors to reduce inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antimicrobials. These programs typically start in hospitals through ascertaining current antimicrobial utilization and resistance patterns, which includes conducting point prevalence surveys (PPS) [Citation58–64]. The findings can subsequently be used to direct future quality improvement programs in hospitals across Africa. Such programs include the instigation of infection, prevention, and control (IPC) committees and associated activities to reduce health care-infections (HAIs). This can be undertaken through antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) where these currently do not exist [Citation65–72]. Studies have also been undertaken regarding the management of surgical site infections (SSIs) across Africa, given concerns with extended antibiotic prophylaxis and the implications for adverse events and AMR [Citation73–75]. The findings have resulted in a range of educational and other multimodal activities being instigated in hospitals to reduce high rates of extended prophylaxis postoperatively [Citation76–78].

Additional activities that can be conducted as part of ASPs to reduce AMR include assessing prescribing against agreed criteria and antibiograms given variable rates of compliance to treatment guidelines among African countries [Citation58,Citation79–83]. However, there have been concerns with the level of knowledge regarding antibiotics and ASPs, as well as the extent of their implementation, among African countries due to resource limitations and other issues, especially in rural areas [Citation84–92]. Encouragingly, this situation is now changing with ASPs increasingly being instigated across Africa [Citation65,Citation68]. These activities have been aided by a growing focus on AMR and antimicrobial use across Africa, coupled with the increasing availability of treatment and other guidelines across Africa [Citation68,Citation93,Citation94]. This is seen as beneficial with ASPs known to improve future antimicrobial use as well as reduce costs and resistance rates across countries [Citation65,Citation67,Citation95,Citation96].

The WHO has also reclassified antibiotics into the Access, Watch, and Reserve (WHO AWaRe) list to help contain AMR [Citation97,Citation98]. The ‘Access’ group of antibiotics are considered as first- or second-line antibiotic choices for empiric treatment for up to 26 common or severe clinical syndromes. The recommended first-line choices of antibiotics in the ‘Access’ group typically have a narrow spectrum as well as low toxicity risk and resistant potential. The ‘Watch’ group of antibiotics are considered as having a higher resistance potential and side effects. Finally, the ‘Reserve’ group of antibiotics should only be considered as last resort antibiotics and prioritized as key targets for any national or local ASP [Citation97–100]. Assessing antimicrobial prescribing against current guidance, and monitoring their use based on the WHO AwaRe list, is increasingly being undertaken across Africa to improve prescribing, which builds on examples globally [Citation98,Citation99,Citation101,Citation102]. This is because the AwaRe list provides robust quality indicators to improve future antimicrobial use across sectors [Citation58,Citation61,Citation82,Citation83,Citation98,Citation99,Citation103,Citation104]. Such activities are critical at this time with high rates of antimicrobial prescribing for patients with COVID-19 across countries, despite limited evidence of concomitant bacterial or fungal infections, adding to AMR concerns [Citation105–113].

Another key concern is the current high levels of inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antimicrobials in ambulatory care among a number of sub-Saharan African countries, especially for self-limiting conditions, including acute respiratory tract infections (ARIs) [Citation14,Citation15,Citation35,Citation114–116]. Furthermore, adherence to prescribing guidelines for patients with respiratory tract infections (RTIs) is currently needed to reduce inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing for these patients [Citation80,Citation117]. Successful programs have been introduced among physicians across countries, including other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), to improve antibiotic prescribing, providing guidance to others [Citation14,Citation35]. Multifaceted interventions have generally been more successful than single educational activities to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing [Citation14,Citation35,Citation118,Citation119]. Studies conducted in Kenya and Namibia have also shown that the presence of trained pharmacists in community pharmacies, alongside knowledge of the current regulations, can reduce inappropriate dispensing of antibiotics without a prescription especially for patients with ARIs [Citation120–123]; however, this is not always the case for other prevalent infections seen in community pharmacies [Citation124].

There are also concerns with increasing resistance rates in animals through the overuse of antibiotics, which exacerbate AMR in the human population [Citation125–128]. This should also be a key element of multisectoral co-ordinated activities among African countries to reduce AMR given current concerns [Citation93,Citation129–132].

1.2. WHO Global Action Plan (GAP) and National Action Plan (NAP) among sub-Saharan African countries

High rates of AMR are a major challenge across countries as they increase morbidity, mortality, and costs [Citation35,Citation133–139], with AMR rates currently exacerbated by the overuse of antimicrobials to treat patients with COVID-19 [Citation108,Citation110,Citation140,Citation141]. For instance, the World Bank (2017) expected that even in a low-AMR scenario, the economic costs of AMR would be considerable. They estimated that the loss of world output arising from AMR could exceed US$1 trillion annually after 2030, and potentially up to US$3.4 trillion annually, unless AMR is addressed. This would be equivalent to 3.8% of annual Gross Domestic Product [Citation142]. In any event, the costs of AMR will appreciably exceed the costs of any antibiotics prescribed or dispensed across sectors [Citation143].

Concerns with rising AMR rates across countries, including sub-Saharan African countries, and the implications on costs and health, have resulted in many national, regional, and international initiatives to try and reverse this trend. The WHO/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Organization for Animal Health (WHO/FAO/OIE) action plan in 2015 resulted in several global activities. These included the Fleming Fund to tackle AMR, the Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (ICGAR) group, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the World Bank initiatives. These activities ran in conjunction with global educational and other initiatives, along with co-ordinated activities at regional and national levels [Citation14,Citation144–157]. We have also seen the development of the first African guidelines for treating common bacterial infections across age groups, with such activities likely to grow given ongoing concerns with rising AMR rates across Africa [Citation158–160].

The GAP of the WHO has resulted in the development of NAPs across countries to reduce AMR [Citation147,Citation148,Citation161–166]. However, there are concerns with their implementation, including among African countries [Citation93,Citation167]. Poor implementation has resulted in renewed calls from the WHO to tackle AMR [Citation168], as well as developing handbooks to help with the implementation of NAPs [Citation169]. In addition, regular monitoring is needed regarding their implementation to optimize their impact [Citation170].

Against this background, we sought to ascertain current issues and challenges associated with the implementation of NAPs across sub-Saharan Africa to reduce AMR rates. Box 1 lists identified pillars within the Global NAP in order to provide direction to individual countries [Citation93,Citation161]. The findings can be used to help guide future activities.

Box 1. Five Strategic Pillars within the WHO Global Action Plans to reduce AMR (adapted from [Citation72,Citation93,Citation161,Citation164])

In their recent study, Elton et al. documented concerns with the overall preparedness of sub-Saharan African countries to tackle AMR [Citation93]. However, there was considerable variation among the countries with East Africa being the most prepared. Southern Africa scored highest for the routine reporting of resistant pathogens and highest for IPC training [Citation93]. Overall, only 25% of sub-Saharan African countries had NAPs in place and only 32% had been conducting routine AMR surveillance, with a similar number stating that they had national guidelines in place for the distribution and use of antimicrobials [Citation93].

As of 31 December 2019, 33 African countries had produced their NAPs, with 16 endorsed at the Government level [Citation8]. This was built on the study by Iwu and Patrick (2021) which documented the implementation of NAPs among the WHO African region in 2018/2019 [Citation72]. There were concerns with developing NAPs among African countries including Lesotho, whereas awareness and training for AMR scored higher in Kenya than other African countries [Citation72]. Implementation of IPC groups was also more advanced in Kenya, Namibia, and the United Republic of Tanzania when compared with the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, and Malawi. Namibia, Rwanda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. These countries were also reported to be more advanced than other African countries regarding activities to optimize the use of antimicrobials in their human population, i.e., more advanced than Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone [Citation72]. A major concern across Africa has been the lack of documented strategies addressing key issues including hygiene, water, and sanitation [Citation171]. The major exceptions to date regarding reporting strategies to address hygiene and sanitation among the African countries include Ethiopia, Mauritius, and South Africa [Citation171].

While more recent published studies have documented that most African countries currently have NAPs to address AMR, there are concerns with the lack of transparency and accountability across countries [Citation172]. This situation has not been helped by problems experienced with the preparedness among some sub-Saharan African countries, to fully tackle AMR in the first place as well as the necessary resources to fully implement their respective NAPs [Citation8,Citation93]. In Zimbabwe, it was estimated that investments of over US$7.5 million per year would be needed to fully fund the activities documented in their NAP [Citation8,Citation173], while US$21 million dollars would be needed in Ghana to implement the activities outlined in their 5-year NAP [Citation174]. In addition, implementation of NAPs are largely donor-driven among a number of sub-Saharan African countries potentially adversely affecting the achievement of documented goals, especially if the focus of the donors change [Citation8]. This includes available resources to develop capacities to improve AMR surveillance [Citation93]. However, monitoring of infectious diseases has been enhanced across Africa with the recent COVID-19 pandemic [Citation175], with such activities likely to remain.

Addressing AMR in a co-ordinated way, with sub-Saharan African countries learning from each other and developing local solutions, will provide a more robust architecture for responding to future and reemerging infectious diseases [Citation8,Citation139,Citation168]. We have already seen a number of innovations being developed among African countries to deal with the recent COVID-19 pandemic providing hope for the future [Citation175,Citation176]. In addition, Southern African Infectious Diseases groups are coming together to co-ordinate research and push forward joint activities, including guideline development and enhanced surveillance, to improve the management of infectious diseases and reduce AMR [Citation152,Citation177,Citation178].

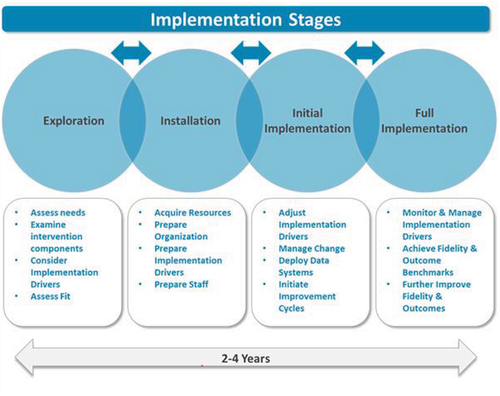

Consequently, the objective of this paper is to document the current situation regarding ongoing activities to address rising AMR rates among a range of sub-Saharan African countries. This includes their current status alongside ongoing challenges regarding their NAPs. Subsequently, discuss how key issues are being addressed across sub-Saharan Africa to improve future antimicrobial utilization and reduce AMR. Our approach builds on the recent studies of Elton et al., Essack, Iwu and Patrick, and Harant for Africa; Engler et al for South Africa; recent studies assessing such issues across Asia; and the recent study of Munkholm et al., who ascertained that published NAPs among African countries were mostly aligned with the GAPs although cross-country learnings could be improved [Citation72,Citation93,Citation166,Citation167,Citation172,Citation179]. We are fully aware that implementation and monitoring of NAPs is multifaceted and typically involves a number of building blocks and key stakeholder groups within a country. Examples from Nigeria and Kenya are illustrated in , respectively.

2. Research design and methods

We adopted a mixed methods approach, which is similar to other Pan-African projects we have undertaken to document and debate key topics, including general issues as well as important matters surrounding both infectious and noninfectious diseases [Citation35,Citation76,Citation175,Citation180–185].

The first stage involved conducting a narrative review of recent published literature regarding activities across Africa, including the development of NAPs and their status, to improve antibiotic utilization through increased knowledge, and other activities, to reduce AMR among a range of sub-Saharan African countries [Citation72,Citation175]. This was not a systematic review as the principal aim of this paper was to document the current situation and strategies regarding AMR and NAPs among selected sub-Saharan African countries to provide future direction. However, the documented studies, including internet publications surrounding the introduction of the NAPs in each country, were based on the considerable knowledge of the senior-level coauthors. This included individual country studies documenting current antimicrobial utilization and resistance rates across all sectors known to the coauthors from each country. We have adopted this approach before when discussing key activities and their future implications across countries and continents [Citation14,Citation35,Citation76,Citation96].

The African countries chosen were also based on the considerable knowledge of the senior-level coauthors to address the objectives of the paper and provide future guidance. The African countries were not split into either low- or middle-income African countries, or by their geography, as the issues and challenges surrounding the implementation of the NAPs were common across Africa [Citation72,Citation93]. Overall, the selected countries provided a range of geographies, economic status [gross domestic product (GDP)/capita] [Citation186], and population size [Citation187] () in order to meet the study objectives.

Table 1. Current population size and GDP/capita among participating African countries.

The second stage involved a summary of key ongoing activities among the selected African countries for 2020/2021, building on summaries within the WHO, FAO, and OIE global tripartite database [Citation188], combined with feedback from senior-level personnel among the various African countries ().

The final stage involved an explorative study among senior-level government, academic, and healthcare professional personnel across Africa using an analytical framework approach, combined with a pragmatic paradigm, to provide future direction [Citation299–301].

The key questions following an analysis of the literature included the following:

Is there a NAP in place in your country to reduce AMR? If so, when was this launched and what are the key organizations involved?

What are the key objectives of the NAP (national/provincial/local) and does this include a One Health approach? Do the objectives include enhancing public awareness regarding antimicrobial use/AMR? If so, how is this instigated?

How is progress toward the objectives of the NAP being measured, e.g. issues surrounding audit and feedback? What key achievements have occurred to date/what are still outstanding?

What structures/activities are in place to improve appropriate antibiotic prescribing and dispensing in humans, e.g. the extent of ASPs now and in the future? What monitoring/surveillance systems are in place across sectors to monitor antibiotic use/resistance/ASP activities? How have these been implemented and any successes to date to improve future antibiotic use?

What are the key challenges to implementing NAPs (national/provincial/local)/key lessons learnt? How are these being addressed?

The senior-level coauthors in each participating country were approached using a purposeful sampling methodology [Citation302]. The coauthors collated the replies from each country, which were subsequently collated and reviewed by the principal author (BG). The initial findings were fed back to each country for review and refinement to enhance their accuracy. The final responses were subsequently analyzed using thematic analysis techniques [Citation183,Citation303]. Common themes were identified and subsequently discussed with the coauthors in each country to provide future direction [Citation183]. During the initial stages of this process, pertinent points arising from the country feedback, including additional key publications, were combined with the findings from the narrative review to provide comprehensive up-to-date feedback for each country. This was seen as crucial in order to fully identify ongoing activities and challenges within each surveyed sub-Saharan African country when implementing their NAPs, with the findings used to discuss potential next steps. The findings were subsequently summarized into the key challenges faced by participating sub-Saharan African countries when implementing their NAPs, which were categorized into limited or no challenge, a challenge or a considerable challenge based on the experiences of the coauthors [Citation304].

There was no ethical approval for this study as we did not include human subjects. In addition, the coauthors were typically technical experts in their field who voluntarily provided the information for this paper. This mirrors similar studies conducted by the coauthors across an appreciable number of African countries and wider, involving both infectious and noninfectious diseases as well as general subjects, and is in line with institutional guidance [Citation35,Citation76,Citation175,Citation180,Citation181,Citation183–185,Citation305,Citation306].

Table 2. Key activities, groups, and evaluation of progress within NAPs to reduce AMR among sub-Saharan African countries.

3. Results

3.1. Current status of NAPs and the monitoring of activities

We will first document the current situation regarding the NAPs in each selected African countries. This includes current structures and activities, as well as ongoing monitoring and evaluation of continuing activities, to achieve agreed target objectives and goals. This will be followed by a summary of key identified challenges regarding the implementation of the NAP across countries and how these are currently being addressed to provide future direction.

All surveyed sub-Saharan African countries have developed country NAPs (). However, implementation of the NAPs varies across Africa. NAPs are currently not launched in some of the included African countries, including Botswana and Namibia, just launched in others including Eswatini and further ahead in several African countries including Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zambia.

3.2. Current challenges and how these are being addressed

summarizes the key challenges seen among the various sub-Saharan African countries when trying to implement their NAPs. These include inadequate regulatory enforcement as well as logistics and other personnel to translate the ambitions in the country NAPs into necessary activities to achieve agreed targets. These issues and concerns are often exacerbated by a lack of adequate finances in reality.

Table 3. Summary of key challenges among sub-Saharan African countries when implementing their NAPs.

Other identified issues and concerns with implementing country NAPs included the lack of representation from other key ministries, including Education and Environment Ministries at NAP monitoring meetings, which compromises delivering agreed multisectoral initiatives. Agreed targets and activities are also being hampered by concerns with their co-ordination at national and local levels. Partner coordination and support including from donors is often not well streamlined, again compromising attaining the ambitious targets within NAPs. There can also be a disconnect between public, private, and industry alignment of AMR activities, which needs to be addressed going forward.

Box 2 summarizes key activities being undertaken among surveyed sub-Saharan African countries to address current NAP challenges ().

Box 2. Summary of key activities to address current challenges

4. Discussion

High rates of AMR across sub-Saharan Africa, with the subsequent impact on morbidity, mortality, and costs, emphasize the importance of rapidly implementing NAPs and monitoring their progress [Citation6,Citation35,Citation133]. It was encouraging to see that all the sub-Saharan African countries surveyed had made progress with constructing and implementing their NAPs. However, some countries are more advanced than others. For instance, Namibia is currently awaiting approval to start implementing their NAP while Botswana will shortly be launching their NAP. Alongside this, countries including Eswatini have just begun their NAP journey. This compares with Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, which are further ahead with their NAPs, including regular monitoring of agreed activities. Countries including Cameroon are also further ahead with their NAP compared with Namibia and Kenya; however, there are concerns with their implementation arising from key issues, including knowledge and training regarding AMR.

It was also encouraging to see there is active monitoring of antimicrobial utilization patterns across sectors among the various sub-Saharan African countries. This includes PPS studies in hospitals as well as seeking greater knowledge of resistance patterns through WHO-GLASS and other activities. Both activities are essential to develop and instigate pertinent quality improvement programs as part of ASPs to improve future prescribing and dispensing of antimicrobials. However, ASP activities are variable across sub-Saharan Africa, and their effectiveness is influenced by available resources, personnel, and knowledge within countries [Citation35,Citation85,Citation88]. Among the sub-Saharan African countries assessed, South Africa appears to have made greatest strides with the implementation of activities to curb AMR across sectors including regular monitoring activities with the implementation of their NAP as well as multiple ASP and other activities [Citation65,Citation307–311]. However, there is still room for improvement [Citation94]. We are also seeing greater use of the AWaRe classification of antibiotics, to facilitate the assessment of the quality of antimicrobial prescribing, alongside greater instigation of IPC programs and activities as well ASPs across countries. These activities will continue as progress is made. This includes the development of potential quality indicators in ambulatory care across Africa building on the AWaRe classification and guidelines.

The challenges with implementing NAPs appeared similar among African countries. Key challenges included a lack of personnel including secretariat personnel to drive forward agreed NAP activities. This accentuates challenges with inter-sectoral synchrony. In addition, there are major issues with available funding, including from donors, to fully implement agreed activities alongside competing demands for scarce resources. The situation has been made worse by the recent COVID-19 pandemic and its unintended consequences which also need to be addressed [Citation175]. Unintended consequences include reduced immunization, especially among children [Citation45,Citation47,Citation49], as well as the management of patients with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) who were not properly monitored and treated during the pandemic due to lockdown measures. As a result, also increasing morbidity, mortality, and costs unless adequately addressed [Citation312–315]. This needs to be acknowledged since if unchecked, undue focus on improving the management of patients with NCDs may divert scarce resources away from implementing agreed NAP activities.

Finally, there are recognized issues and challenges with expertise and knowledge regarding AMR and ASPs across sub-Saharan Africa. However, this is beginning to change with increasing educational and implementation activities, including Apps for electronic prescribing, to improve future prescribing coupled with calls to improve qualitative research in this area [Citation63,Citation310,Citation316–319]. Furthermore, there are a number of ongoing initiatives across sub-Saharan Africa to address current challenges including general and specific activities to progress NAPs (Box 2). Such activities will continue given the high and growing rates of AMR across sub-Saharan Africa as well as the economic costs [Citation6,Citation142]. Consequently, urgent actions are needed across sub-Saharan Africa to reduce high AMR rates. This will increasingly include social media outlets addressing concerns with often limited involvement of key healthcare workers [Citation321,Citation320]. Such actions will be the responsibility of all key stakeholder groups going forward, including donors.

We are aware that there are several limitations with this paper. First, similar to our approach in previous papers, we did not undertake a systematic review as the main aim of this paper was to document the current situation and strategies regarding AMR and NAPs among a number of sub-Saharan African countries to provide future direction. As such, we did not include all sub-Saharan African countries just those where the coauthors were able to provide considerable input to meet the study objectives. We also did not categorize sub-Saharan African countries by geography or GDP as we believed the challenges applied to all sub-Saharan African countries and our objective was to consolidate current information and guidance. Furthermore, we recognize that the feedback and potential ways forward are not always based on published studies. However, to address this concern, we have included senior-level personnel, who are extensively involved with issues of antimicrobial utilization, AMR and ASPs in their countries. Despite these limitations, we believe our findings and suggestions are robust and provide future direction.

5. Expert opinion including potential ways forward

There is increasing recognition among all key stakeholders, including donors, in sub-Saharan African countries that AMR is an increasing concern that must be adequately addressed through a co-ordinated NAP approach involving all sectors, which includes humans, animals, and agriculture. However, while all surveyed sub-Saharan African countries had developed their NAPs, they are at different stages of implementation. These range from shortly looking to implement country NAPs to regularly monitor agreed activities within country NAPs to reduce AMR. Current challenges to implementing NAPs include the lack of available personnel, expertise, and funds. Challenges also include issues of capacity including surveillance, competing demands for scarce resources as well as concerns with inter-sectoral synchrony. It is likely we will see these challenges being addressed over the coming years across sub-Saharan Africa with the support of donors and others to improve surveillance and other activities. In addition, articulation and communication of agreed activities will improve to reach stated goals. Alongside this, enhancing engagement among all key stakeholders for end-to-end processes to improve ownership and implementation of NAPs to achieve desired ends.

Specific activities to help achieve desired goals within country NAPs include expansion of educational activities within university curricula and post-qualification among key healthcare groups. We will also likely see IPC programs becoming a routine part of all hospital activities. PPS studies and other activities will also be routinely undertaken in hospitals to identify potential interventions to further enhance the rational use of antibiotics within hospitals. Potential targets in hospitals for quality improvement programs include greater documentation regarding the rationale behind the chosen antibiotics, reducing extended prophylaxis for antibiotics administered to reduce SSIs in patients undergoing surgery, greater adoption of the WHO AWaRe classification as part of potential quality indicators, and increased monitoring of adherence to agreed guidelines when antibiotics are administered. This includes greater monitoring of prescribing of antibiotics from the WHO Watch list. Greater use of electronic technology including Apps will assist with routine surveillance and assist with appropriate responses to reduce hospital acquired antibiotic-resistant infections.

There will also be growing introduction of ASPs within ambulatory care to address inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics in this key sector, especially for potentially self-limiting conditions such as ARIs. Potential quality targets include the percentage of patients prescribed an antibiotic for an ARI and the nature of any antibiotic prescribed. The dispensing of antibiotics without a prescription is also an increasing concern across Africa, with increasing activities likely to address this. Potential activities include greater education of patients and community pharmacists, as well as regular monitoring of community pharmacies to enhance their compliance with any regulations. Different mass media sources will also be increasingly used to educate patients regarding the harms associated with AMR and ways to reduce this. Mobile telephones, and other technologies, will also be increasingly used to track dispensing of antibiotics. Alongside this, increasing monitoring of the availability of sub-standard antibiotics, with associated activities to curtail their availability, as part of community activities to reduce AMR.

Lessons from the current COVID-19 pandemic will lead to the instigation of educational and other activities to ensure continued high rates of pertinent vaccinations to reduce future infectious diseases, and with this inappropriate antibiotic use and AMR. This will necessarily entail interventions targeting healthcare professionals and patients to address vaccine hesitancy as well as ensuring vaccination programs continue during future pandemics. This can involve the use of mobile clinics and other community service points, e.g. pharmacies, if accessing hospital clinics is a challenge. This ensures the situation seen when lockdown and other measures were first introduced to curb the spread of COVID-19 is not repeated. These activities recognize the important role of vaccination policies, communication, and demand creation in preventing infectious diseases, inappropriate antibiotic utilization, and the development of AMR.

Article highlights

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) rates are growing especially in sub-Saharan Africa with increasing morbidity, mortality, and costs, with sub-Saharan Africa currently having the highest mortality due to AMR globally.

Concerns with rising AMR rates have resulted in the WHO instigating national action plans to try and address AMR among countries. This includes African countries.

While all surveyed African countries have developed NAPs, there is currently variable introduction and implementation across Africa, with key challenges persisting.

Currently, South Africa appears to have made the greatest strides with implementing its NAP, which includes regular monitoring of agreed activities as well as instigation and monitoring of antimicrobial stewardship programs.

However, sub-Saharan countries including Botswana and Namibia are yet to officially launch their NAPs with Eswatini only recently launching its NAP. Cameroon is further ahead with its NAP than these countries; however, there are currently concerns with implementation.

Key challenges remain across Africa with implementing NAPs, although these are starting to be addressed. Key challenges include available personnel and expertise, lack of focal points to drive NAPs forward, and resources issues to undertake active surveillance of resistance patterns across sectors exacerbated by competing demands and priorities including among donors.

Declaration of interest

A Egwuenu, E Wesangula, C Tiroyakgosi, Joyce Kgatlwane, AN Guantai, S Opanga, F Kalemeera, BE Ebruke, JC Meyer, OO Malande, O Kapona, T Kujinga, AA Jairoun, AJ Brink are employed by National Health Services or Ministries of Health, or are advisers to Ministries of Health, the WHO or other leading Infectious Disease Groups. In addition, S Opanga received a grant from Kenya AIDS Vaccine Institute -Institute of Clinical Research and Institut Merieux for tackling antimicrobial resistance in Kenya. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the development of this paper and approved the various submissions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Nkengasong JN, Tessema SK. Africa needs a new public health order to tackle infectious disease threats. Cell. 2020;183(2):296–300.

- Bell D, Schultz Hansen K. Relative burdens of the COVID-19, malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;105(6):1510–1515.

- Dwyer-Lindgren L, Cork MA, Sligar A, et al. Mapping HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017. Nature. 2019;570(7760):189–193.

- Williams PCM, Isaacs D, Berkley JA. Antimicrobial resistance among children in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(2):e33–e44.

- Bernabé KJ, Langendorf C, Ford N, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in West Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50(5):629–639.

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629–655. •• Landmark study highlighting the growing importance of AMR as the next pandemic.

- Wamai RG, Hirsch JL, Van Damme W, et al. What could explain the lower COVID-19 burden in Africa despite considerable circulation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8638.

- Mpundu M Moving from paper to action – the status of national AMR action plans in African countries. 2020 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://revive.gardp.org/moving-from-paper-to-action-the-status-of-national-amr-action-plans-in-african-countries/

- Collignon P, Beggs JJ, Walsh TR, et al. Anthropological and socioeconomic factors contributing to global antimicrobial resistance: a univariate and multivariable analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(9):e398–e405.

- Hendriksen RS, Munk P, Njage P, et al. Global monitoring of antimicrobial resistance based on metagenomics analyses of urban sewage. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1124.

- Mabirizi D, Kibuule D, and Adorka M, et al. Promoting the rational medicine use of ARVs. Anti-TB, and Other Medicines and Preventing the Development of Antimicrobial Resistance in Namibia: Workshop and Stakeholders Forum; Namibia. 2013 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00JP4B.pdf

- Balala A, Huong TG, Fenwick SG Antibiotics resistance in sub Saharan Africa; literature review from 2010 – 2017. 2020; 37(- 0).

- Laxminarayan R, Van Boeckel T, Frost I, et al. The lancet infectious diseases commission on antimicrobial resistance: 6 years later. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):e51–e60.

- Godman B, Haque M, McKimm J, et al. Ongoing strategies to improve the management of upper respiratory tract infections and reduce inappropriate antibiotic use particularly among lower and middle-income countries: findings and implications for the future. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(2):301–327.

- Kalungia AC, Burger J, Godman B, et al. Non-prescription sale and dispensing of antibiotics in community pharmacies in Zambia. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14(12):1215–1223.

- Ayukekbong JA, Ntemgwa M, Atabe AN. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6(1):47.

- Tadesse BT, Ashley EA, Ongarello S, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):616.

- Workneh M, Katz MJ, Lamorde M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of sterile site infections in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(4):ofx209.

- Sriram AKE, Kapoor G, Craig J, et al. State of the world’s antibiotics 2021: a global analysis of antimicrobial resistance and its drivers. Washington (DC): Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy; 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/The-State-of-the-Worlds-Antibiotics-in-2021.pdf

- Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(15):E3463–e70.

- Huemer M, Mairpady Shambat S, Brugger SD, et al. Antibiotic resistance and persistence-Implications for human health and treatment perspectives. EMBO Rep. 2020;21(12):e51034.

- Asrade B Prevalence of Substandard and Falsified Drugs in Africa; 2021. Available from: https://www.globalpharmacyexchange.org/post/prevalence-of-substandard-and-falsified-drugs-in-africa.

- Kelesidis T, Falagas ME. Substandard/counterfeit antimicrobial drugs. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(2):443–464.

- WHO. 1 in 10 medical products in developing countries is substandard or falsified; 2017 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-11-2017-1-in-10-medical-products-in-developing-countries-is-substandard-or-falsified

- Ghanem N. Substandard and falsified medicines: global and local efforts to address a growing problem. Clin Pharm. 2019;11(5) DOI:10.1211/PJ.2019.20206309.

- Tessema GA, Kinfu Y, Dachew BA, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and healthcare systems in Africa: a scoping review of preparedness, impact and response. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(12). 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007179.

- Adepoju P. African nations to criminalise falsified medicine trafficking. Lancet. 2020;395(10221):324.

- WHO. Launch of the Lomé Initiative; 2020 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/launch-of-the-lom%C3%A9-initiative

- Acosta A, Vanegas EP, Rovira J, et al. Medicine shortages: gaps between countries and global perspectives. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:763.

- Modisakeng C, Matlala M, Godman B, et al. Medicine shortages and challenges with the procurement process among public sector hospitals in South Africa; findings and implications. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):234.

- Chigome AK, Matlala M, Godman B, et al. Availability and use of therapeutic interchange policies in managing antimicrobial shortages among South African public sector hospitals; Findings and implications. Antibiotics. 2019;9(1):4.

- MacPherson EE, Reynolds J, Sanudi E, et al. Understanding antimicrobial resistance through the lens of antibiotic vulnerabilities in primary health care in rural Malawi. Glob Public Health. 2021:1–17. 10.1080/17441692.2021.2015615.

- Meyer JC, Schellack N, Stokes J, et al. Ongoing initiatives to improve the quality and efficiency of medicine use within the public healthcare system in South Africa; A preliminary study. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:751.

- Leung N-HZ, Chen A, Yadav P, et al. The impact of inventory management on stock-outs of essential drugs in sub-Saharan Africa: secondary analysis of a field experiment in Zambia. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0156026–e.

- Godman B, Egwuenu A, Haque M, et al. Strategies to improve antimicrobial utilization with a special focus on developing countries. Life. 2021;11(6):528.

- Jansen KU, Anderson AS. The role of vaccines in fighting antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(9):2142–2149.

- Micoli F, Bagnoli F, Rappuoli R, et al. The role of vaccines in combatting antimicrobial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(5):287–302.

- Cohen R, Cohen JF, Chalumeau M, et al. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for children in high- and non-high-income countries. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;16(6):625–640.

- Troisi M, Andreano E, Sala C, et al. Vaccines as remedy for antimicrobial resistance and emerging infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 2020;65:102–106.

- Lewnard JA, Lo NC, Arinaminpathy N, et al. Childhood vaccines and antibiotic use in low- and middle-income countries. Nature. 2020;581(7806):94–99.

- Bloom DE, Black S, Salisbury D, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and the role of vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(51):12868–12871.

- Buchy P, Ascioglu S, Buisson Y, et al. Impact of vaccines on antimicrobial resistance. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;90:188–196.

- Montwedi DNMJ, Nkwinika VV, Burnett RJ. Health facility obstacles result in missed vaccination opportunities in Tshwane region 5, Gauteng province. South Afr J Child Health. 2021;15(3):159–164.

- Muhoza P, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Diallo MS, et al. Routine vaccination coverage - worldwide, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(43):1495–1500.

- Abbas K, Procter SR, van Zandvoort K, et al. Routine childhood immunisation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a benefit-risk analysis of health benefits versus excess risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(10):e1264–e72.

- Olorunsaiye CZ, Yusuf KK, Reinhart K, et al. COVID-19 and child vaccination: a systematic approach to closing the immunization gap. Int J MCH AIDS. 2020;9(3):381–385.

- Gaythorpe KA, Abbas K, Huber J, et al. Impact of COVID-19-related disruptions to measles, meningococcal A, and yellow fever vaccination in 10 countries. Elife. 2021;10. DOI:10.7554/eLife.67023.

- Lassi ZS, Naseem R, Salam RA, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immunization campaigns and programs: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):988.

- Ota MOC, Badur S, Romano-Mazzotti L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on routine immunization. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):2286–2297.

- Roberts L. Pandemic brings mass vaccinations to a halt. Science. 2020;368(6487):116–117.

- Coker M, Folayan MO, Michelow IC, et al. Things must not fall apart: the ripple effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children in sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatr Res. 2021;89(5):1078–1086.

- Jarchow-MacDonald AA, Burns R, Miller J, et al. Keeping childhood immunisation rates stable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(4):459–460.

- Rana S, Shah R, Ahmed S, et al. Post-disruption catch-up of child immunisation and health-care services in Bangladesh. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(7):913.

- Shahwan M, Suliman A, Abdulrahman Jairoun A, et al. Prevalence, knowledge and potential determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among university students in the United Arab Emirates: findings and implications. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022;15:81–92.

- Afolabi AA, Ilesanmi OS. Dealing with vaccine hesitancy in Africa: the prospective COVID-19 vaccine context. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38:3.

- Cooper S, van Rooyen H, Wiysonge CS. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa: how can we maximize uptake of COVID-19 vaccines? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021;20(8):921–933.

- Mutombo PN, Fallah MP, Munodawafa D, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Africa: a call to action. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(3):e320–e1.

- Anand Paramadhas BD, Tiroyakgosi C, Mpinda-Joseph P, et al. Point prevalence study of antimicrobial use among hospitals across Botswana; findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019;17(7):535–546.

- Kruger D, Dlamini NN, Meyer JC, et al. Development of a web-based application to improve data collection of antimicrobial utilization in the public health care system in South Africa. Hosp Pract. 2021;49(3):184–193.

- Momanyi L, Opanga S, Nyamu D, et al. Antibiotic prescribing patterns at a leading referral hospital in Kenya: a point prevalence survey. J Res Pharm Pract. 2019;8(3):149–154.

- Skosana PP, Schellack N, Godman B, et al. A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial utilisation patterns and quality indices amongst hospitals in South Africa; findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021;19(10):1353–1366.

- Ogunleye OO, Oyawole MR, Odunuga PT, et al. A multicentre point prevalence study of antibiotics utilization in hospitalized patients in an urban secondary and a tertiary healthcare facilities in Nigeria: findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2022;20(2):297–306.

- D’Arcy N, Ashiru-Oredope D, Olaoye O, et al. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in Ghana, Uganda, Zambia and Tanzania hospitals: results from the global point prevalence survey (G-PPS) on antimicrobial use and stewardship interventions implemented. Antibiotics. 2021;10(9):1122.

- Afriyie DK, Sefah IA, Sneddon J, et al. Antimicrobial point prevalence surveys in two Ghanaian hospitals: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2020;2(1):dlaa001.

- Brink AJ, Messina AP, Feldman C, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship across 47 South African hospitals: an implementation study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(9):1017–1025.

- Department of Health Republic of South Africa. National infection prevention and control strategic framework. 2020 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/National-Infection-Prevention-and-Control-Strategic-Framework-March-2020-1.pdf

- Nathwani D, Varghese D, Stephens J, et al. Value of hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs [ASPs]: a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8(1):35.

- Akpan MR, Isemin NU, Udoh AE, et al. Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in African countries: a systematic literature review. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;22:317–324.

- Mpinda-Joseph P, Anand Paramadhas BD, Reyes G, et al. Healthcare-associated infections including neonatal bloodstream infections in a leading tertiary hospital in Botswana. Hosp Pract. 2019;47(4):203–210.

- Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Owusu E, et al. Multi-centre point-prevalence survey of hospital-acquired infections in Ghana. J Hosp Infect. 2019;101(1):60–68.

- Irek EO, Amupitan AA, Obadare TO, et al. A systematic review of healthcare-associated infections in Africa: an antimicrobial resistance perspective. Afr J Lab Med. 2018;7(2):796.

- Iwu CD, Patrick SM. An insight into the implementation of the global action plan on antimicrobial resistance in the WHO African region: a roadmap for action. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2021;58(4):106411.

- Ariyo P, Zayed B, Riese V, et al. Implementation strategies to reduce surgical site infections: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40(3):287–300.

- Mwita JC, Souda S, Magafu M, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent surgical site infections in Botswana: findings and implications. Hosp Pract. 2018;46(3):97–102.

- Cooper L, Sneddon J, Afriyie DK, et al. Supporting global antimicrobial stewardship: antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of surgical site infection in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): a scoping review and meta-analysis. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. 2020;2(3). DOI:10.1093/jacamr/dlaa070.

- Mwita JC, Ogunleye OO, Olalekan A, et al. Key issues surrounding appropriate antibiotic use for prevention of surgical site infections in low- and middle-income countries: a narrative review and the implications. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:515–530.

- Allegranzi B, Aiken AM, Zeynep Kubilay N, et al. A multimodal infection control and patient safety intervention to reduce surgical site infections in Africa: a multicentre, before-after, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(5):507–515.

- Menz BD, Charani E, Gordon DL, et al. Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in an era of antibiotic resistance: common resistant bacteria and wider considerations for practice. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:5235–5252.

- Olaru ID, Meierkord A, Godman B, et al. Assessment of antimicrobial use and prescribing practices among pediatric inpatients in Zimbabwe. J Chemother. 2020;32(8):456–459.

- Sefah IA, Essah DO, Kurdi A, et al. Assessment of adherence to pneumonia guidelines and its determinants in an ambulatory care clinic in Ghana: findings and implications for the future. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(2):dlab080.

- van der Sandt N, Schellack N, Mabope LA, et al. Surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis among pediatric patients in South Africa comparing two healthcare settings. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(2):122–126.

- Niaz Q, Godman B, Campbell S, et al. Compliance to prescribing guidelines among public health care facilities in Namibia; findings and implications. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(4):1227–1236.

- Seni J, Mapunjo SG, Wittenauer R, et al. Antimicrobial use across six referral hospitals in Tanzania: a point prevalence survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e042819.

- Ogunleye OO, Fadare JO, Yinka-Ogunleye AF, et al. Determinants of antibiotic prescribing among doctors in a Nigerian urban tertiary hospital. Hosp Pract. 2019;47(1):53–58.

- Fadare JO, Ogunleye O, Iliyasu G, et al. Status of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in Nigerian tertiary healthcare facilities: findings and implications. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;17:132–136.

- Babatola AO, Fadare JO, Olatunya OS, et al. Addressing antimicrobial resistance in Nigerian hospitals: exploring physicians prescribing behavior, knowledge, and perception of antimicrobial resistance and stewardship programs. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021;19(4):537–546.

- Kalungia AC, Mwambula H, Munkombwe D, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship knowledge and perception among physicians and pharmacists at leading tertiary teaching hospitals in Zambia: implications for future policy and practice. J Chemother. 2019;31(7–8):378–387.

- Cox JA, Vlieghe E, Mendelson M, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in low- and middle-income countries: the same but different? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(11):812–818.

- Hijazi K, Joshi C, Gould IM. Challenges and opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship in resource-rich and resource-limited countries. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019;17(8):621–634.

- Pierce J, Apisarnthanarak A, Schellack N, et al. Global antimicrobial stewardship with a focus on low- and middle-income countries. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:621–629.

- Nampoothiri V, Bonaconsa C, Surendran S, et al. What does antimicrobial stewardship look like where you are? Global narratives from participants in a massive open online course. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2022;4(1):dlab186.

- Yau JW, Thor SM, Tsai D, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship in rural and remote primary health care: a narrative review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10(1):105.

- Elton L, Thomason MJ, Tembo J, et al. Antimicrobial resistance preparedness in sub-Saharan African countries. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):145.

- Engler D, Meyer JC, Schellack N, et al. Compliance with South Africa’s antimicrobial resistance national strategy framework: are we there yet? J Chemother. 2021;33(1):21–31.

- Majumder MAA, Rahman S, Cohall D, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship: fighting antimicrobial resistance and protecting global public health. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:4713–4738.

- Haque M, Godman B. Potential strategies to improve antimicrobial utilisation in hospitals in Bangladesh building on experiences across developing countries. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2021;20(3):469–477.

- Sharland M, Pulcini C, Harbarth S, et al. Classifying antibiotics in the WHO essential medicines list for optimal use-be AWaRe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):18–20.

- Sharland M, Gandra S, Huttner B, et al. Encouraging AWaRe-ness and discouraging inappropriate antibiotic use-the new 2019 essential medicines list becomes a global antibiotic stewardship tool. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(12):1278–1280.

- Hsia Y, Lee BR, Versporten A, et al. Use of the WHO Access, Watch, and Reserve classification to define patterns of hospital antibiotic use (AWaRe): an analysis of paediatric survey data from 56 countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(7):e861–e71

- Klein EY, Milkowska-Shibata M, Tseng KK, et al. Assessment of WHO antibiotic consumption and access targets in 76 countries, 2000-15: an analysis of pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):107–115.

- Pauwels I, Versporten A, Drapier N, et al. Hospital antibiotic prescribing patterns in adult patients according to the WHO Access, Watch and Reserve classification (AWaRe): results from a worldwide point prevalence survey in 69 countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76(6):1614–1624.

- Sulis G, Adam P, Nafade V, et al. Antibiotic prescription practices in primary care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(6):e1003139.

- Okoth C, Opanga S, Okalebo F, et al. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic use and resistance at a referral hospital in Kenya: findings and implications. Hosp Pract. 2018;46(3):128–136.

- Sulis G, Daniels B, Kwan A, et al. Antibiotic overuse in the primary health care setting: a secondary data analysis of standardised patient studies from India, China and Kenya. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(9):e003393.

- Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(4):520–531.

- Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfection in individuals with coronavirus: a rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(9):2459–2468.

- Iwu CJ, Jordan P, Jaja IF, et al. Treatment of COVID-19: implications for antimicrobial resistance in Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2):119.

- Alshaikh FS, Godman B, Sindi ON, Seaton RA, Kurdi A. Prevalence of bacterial coinfection and patterns of antibiotics prescribing in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0272375

- Founou RC, Blocker AJ, Noubom M, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: a threat to antimicrobial resistance containment. Future Sci OA. 2021;7(8):Fso736.

- Hsu J. How covid-19 is accelerating the threat of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ. 2020;369:m1983.

- Cheng LS, Chau SK, Tso EY, et al. Bacterial co-infections and antibiotic prescribing practice in adults with COVID-19: experience from a single hospital cluster. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2020;7:2049936120978095.

- Goncalves Mendes Neto A, Lo KB, Wattoo A, et al. Bacterial infections and patterns of antibiotic use in patients with COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021;93(3):1489–1495.

- Hughes S, Troise O, Donaldson H, et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfection among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study in a UK secondary-care setting. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(10):1395–1399.

- Tiroyakgosi C, Matome M, Summers E, et al. Ongoing initiatives to improve the use of antibiotics in Botswana: university of Botswana symposium meeting report. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018;16(5):381–384.

- Mathibe LJ, Zwane NP. Unnecessary antimicrobial prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in children in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Afr Health Sci. 2020;20(3):1133–1142.

- Ocan M, Aono M, Bukirwa C, et al. Medicine use practices in management of symptoms of acute upper respiratory tract infections in children (≤12 years) in Kampala city, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):732.

- Ncube NB, Solanki GC, Kredo T, et al. Antibiotic prescription patterns of South African general medical practitioners for treatment of acute bronchitis. S Afr Med J. 2017;107(2):119–122.

- Köchling A, Löffler C, Reinsch S, et al. Reduction of antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory tract infections in primary care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):47.

- Nair MM, Mahajan R, Burza S, et al. Behavioural interventions to address rational use of antibiotics in outpatient settings of low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26(5):504–517.

- Opanga S, Rizvi N, Wamaitha A, et al. Availability of medicines in community pharmacy to manage patients with COVID-19 in Kenya; Pilot study and implications. Sch Acad J Pharm. 2021;10(3):36–42.

- Mukokinya MMA, Opanga S, Oluka M, et al. Dispensing of antimicrobials in Kenya: a cross-sectional pilot study and its implications. J Res Pharm Pract. 2018;7(2):77–82.

- Kamati M, Godman B, Kibuule D. Prevalence of self-medication for acute respiratory infections in young children in Namibia: findings and implications. J Res Pharm Pract. 2019;8(4):220–224.

- Kibuule D, Nambahu L, Sefah IA, et al. Activities in Namibia to limit the prevalence and mortality from COVID-19 including community pharmacy activities and the implications. Sch Acad J Pharm. 2021;10(5):82–92.

- Mokwele RN, Schellack N, Bronkhorst E, et al. Using mystery shoppers to determine practices pertaining to antibiotic dispensing without a prescription among community pharmacies in South Africa—a pilot survey. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. 2022;4(1). DOI:10.1093/jacamr/dlab196

- Morel CM, Alm RA, Årdal C, et al. A one health framework to estimate the cost of antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):187.

- Mohsin M, Van Boeckel TP, Saleemi MK, et al. Excessive use of medically important antimicrobials in food animals in Pakistan: a five-year surveillance survey. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(sup1):1697541.

- Van Boeckel TP, Pires J, Silvester R, et al. Global trends in antimicrobial resistance in animals in low- and middle-income countries. Science. 2019;365(6459). DOI:10.1126/science.aaw1944.

- Samutela MT, Kwenda G, Simulundu E, et al. Pigs as a potential source of emerging livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus in Africa: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;109:38–49.

- McEwen SA, Collignon PJ. Antimicrobial resistance: a one health perspective. Microbiol Spectr. 2018;6(2). DOI:10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0009-2017

- Aidara-Kane A, Angulo FJ, Conly JM, et al. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on use of medically important antimicrobials in food-producing animals. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(1):7.

- Kaupitwa CJ, Nowaseb S, Godman B, Kibuule D. Analysis of policies for use of medically important antibiotics in animals in Namibia: implications for antimicrobial stewardship. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 2022 (EPrint).

- Van TTH, Yidana Z, Smooker PM, et al. Antibiotic use in food animals worldwide, with a focus on Africa: pluses and minuses. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;20:170–177.

- Hofer U. The cost of antimicrobial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(1):3.

- Founou RC, Founou LL, Essack SY. Clinical and economic impact of antibiotic resistance in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2017;12(12):e0189621.

- Zhen X, Lundborg CS, Sun X, et al. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance in ESKAPE organisms: a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8(1):137.

- Dadgostar P. Antimicrobial resistance: implications and costs. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:3903–3910.

- Cassini A, Högberg LD, Plachouras D, et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):56–66.

- Naylor NR, Atun R, Zhu N, et al. Estimating the burden of antimicrobial resistance: a systematic literature review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(1):58.

- Wilson LA, Van Katwyk SR, Weldon I, et al. A global pandemic treaty must address antimicrobial resistance. J Law Med Ethics. 2021;49(4):688–691.

- Ghosh S, Bornman C, Zafer MM. Antimicrobial resistance threats in the emerging COVID-19 pandemic: where do we stand? J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(5):555–560.

- Jampani M, Chandy SJ. Increased antimicrobial use during COVID-19: the risk of advancing the threat of antimicrobial resistance. Health Sci Rep. 2021;4(4):e459.

- The World Bank. Final report - Drug-resistant infections. A threat to our economic future; 2017 Mar. [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/323311493396993758/pdf/final-report.pdf

- Shrestha P, Cooper BS, Coast J, et al. Enumerating the economic cost of antimicrobial resistance per antibiotic consumed to inform the evaluation of interventions affecting their use. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(1):98.

- Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance. No time to wait: securing the future from drug-resistant infections - Report to the secretary-General of the united nations; April 2019 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/interagency-coordination-group/IACG_final_report_EN.pdf?ua=1

- OECD Health Policy Studies, Stemming the Superbug Tide. 2018 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9789264307599-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/9789264307599-en&mimeType=text/html

- World Health Organisation. Antimicrobial resistance. 2018. [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance

- Federal Ministries of Agriculture, Rural Development, Environment and Health, Abuja, Nigeria. National action plan for antimicrobial resistance, 2017–2022; 2017 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://ncdc.gov.ng/themes/common/docs/protocols/77_1511368219.pdf

- Saleem Z, Hassali MA, Hashmi FK. Pakistan’s national action plan for antimicrobial resistance: translating ideas into reality. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(10):1066–1067.

- Fürst J, Čižman M, Mrak J, et al. The influence of a sustained multifaceted approach to improve antibiotic prescribing in Slovenia during the past decade: findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13(2):279–289.

- Sartelli M, Catena F, Chichom-Mefire A, et al. Antibiotic use in low and middle-income countries and the challenges of antimicrobial resistance in surgery. Antibiotics. 2020;9(8):497.

- Frost I, Van Boeckel TP, Pires J, et al. Global geographic trends in antimicrobial resistance: the role of international travel. J Travel Med. 2019;26(8). DOI:10.1093/jtm/taz036

- Matee M. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) at the Southern Africa centre for infectious disease surveillance; 2018 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/southern-africa-centre-for-infectious-disease/52063/

- WHO. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report; 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027336

- World Bank Group. Pulling together to beat superbugs knowledge and implementation gaps in addressing antimicrobial resistance; 2019 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/32552/Pulling-Together-to-Beat-Superbugs-Knowledge-and-Implementation-Gaps-in-Addressing-Antimicrobial-Resistance.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- WHO. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance - Report by the Secretariat. 2016 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_24-en.pdf

- GASPH. Global Antimicrobial Stewardship Partnership Hub; 2022 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://global-asp-hub.com/

- BSAC. Global antimicrobial stewardship accreditation scheme; 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://bsac.org.uk/global-antimicrobial-stewardship-accreditation-scheme/

- Craig J, Frost I, Sriram A, et al. Development of the first edition of African treatment guidelines for common bacterial infections and syndromes. J Public Health Afr. 2022;12(2). DOI:10.4081/jphia.2021.2009.

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy. African antibiotic treatment guidelines for common bacterial infections and syndromes - recommended antibiotic treatments in neonatal and pediatric patients; 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://africaguidelines.cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Quick-Reference-Guide_Peds_English.pdf

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy. African antibiotic treatment guidelines for common bacterial infections and syndromes - recommended antibiotic treatments in adult patients; 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://africaguidelines.cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Quick-Reference-Guide_Adults_English.pdf

- WHO. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance; 2015 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/193736/9789241509763_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Ghana Ministry of Health, Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation, Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development. Ghana National Action Plan for Antimicrobial Use and Resistance; 2017–2021 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/NAP_FINAL_PDF_A4_19.03.2018-SIGNED-1.pdf

- Mendelson M, Matsoso M. The South African antimicrobial resistance strategy framework. AMR Control. 2015;54–61.

- Republic of Kenya. National action plan on prevention and containment of antimicrobial resistance, 2017–2022; 2017 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/national-action-plan-prevention-and-containment-antimicrobial-resistance-2017-2022

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of Bangladesh. National action plan: antimicrobial resistance containment in Bangladesh 2017-’22; 2017 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.flemingfund.org/wp-content/uploads/d3379eafad36f597500cb07c21771ae3.pdf

- Munkholm L, Rubin O. The global governance of antimicrobial resistance: a cross-country study of alignment between the global action plan and national action plans. Global Health. 2020;16(1):109.

- Saleem Z, Godman B, Azhar F, et al. Progress on the national action plan of Pakistan on antimicrobial resistance (AMR): a narrative review and the implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2022;20(1):71–93.

- WHO. Call to action on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – 2021; [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.un.org/pga/75/wp-content/uploads/sites/100/2021/04/Call-to-Action-on-Antimicrobial-Resistance-AMR-2021.pdf

- WHO implementation handbook for national action plans on antimicrobial resistance: guidance for the human health sector; 2022 [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041981

- World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). Monitoring global progress on antimicrobial resistance: Tripartite amr country self-assessment survey (TRACSS) 2019-2020 global analysis report; 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/monitoring-global-progress-on-antimicrobial-resistance-tripartite-amr-country-self-assessment-survey-(tracss)-2019-2020

- Essack S. Water, sanitation and hygiene in national action plans for antimicrobial resistance. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(8):606–608.

- Harant A. Assessing transparency and accountability of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance in 15 African countries. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022;11(1):15.

- Government of Zimbabwe. The Zimbabwe one health antimicrobial resistance national action plan, 2017-2021; 2017. [cited 2022 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.flemingfund.org/wp-content/uploads/23599b35adfb6d04c2d3f422d34bcff3.pdf

- Opintan JA. Leveraging donor support to develop a national antimicrobial resistance policy and action plan: Ghana’s success story. Afr J Lab Med. 2018;7(2):825.

- Ogunleye OO, Basu D, Mueller D, et al. Response to the Novel Corona Virus (COVID-19) pandemic across Africa: successes, challenges, and implications for the future. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1205.

- Afriyie DK, Asare GA, Amponsah SK, et al. COVID-19 pandemic in resource-poor countries: challenges, experiences and opportunities in Ghana. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14(8):838–843.

- Govender NP, Avenant T, Brink A, et al. Federation of infectious diseases societies of Southern Africa guideline: recommendations for the detection, management and prevention of healthcare-associated Candida auris colonisation and disease in South Africa. S Afr J Infect Dis. 2019;34(1):163.

- Hanin MCE, Queenan K, Savic S, et al. A One Health evaluation of the Southern African Centre for Infectious Disease Surveillance. Front Vet Sci. 2018;5. DOI:10.3389/fvets.2018.00033

- Chua AQ, Verma M, Hsu LY, et al. An analysis of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance in Southeast Asia using a governance framework approach. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;7:100084.

- Godman B, Basu D, Pillay Y, et al. Ongoing and planned activities to improve the management of patients with Type 1 diabetes across Africa; implications for the future. Hosp Pract. 2020;48(2):51–67.

- Godman B, Basu D, Pillay Y, et al. Review of ongoing activities and challenges to improve the care of patients with type 2 diabetes across Africa and the implications for the future. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:108.

- Godman B, Leong T, Abubakar AR, et al. Availability and use of long-acting insulin analogues including their biosimilars across Africa: findings and implications. Intern Med. 2021;11:343.

- Etando A, Amu AA, Haque M, et al. Challenges and innovations brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic regarding medical and pharmacy education especially in Africa and implications for the future. Healthcare. 2021;9(12):1722.

- Godman B, Grobler C, Van-De-Lisle M, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic interventions for bipolar disorder type II: addressing multiple symptoms and approaches with a particular emphasis on strategies in lower and middle-income countries. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20(18):2237–2255.

- Sefah IA, Ogunleye OO, Essah DO, et al. Rapid assessment of the potential paucity and price increases for suggested medicines and protection equipment for COVID-19 across developing countries with a particular focus on Africa and the implications. Front Pharmacol. 2021;11:588106.