ABSTRACT

Introduction

There is a need for anti-seizure medications (ASMs) that are well tolerated and effective as monotherapy or first adjunctive therapy to reduce the need for adjunctive ASMs to treat newly diagnosed epilepsy, and to reduce the number of concomitant ASMs in patients with refractory epilepsy. Although the pivotal trials of perampanel evaluated its adjunctive use in patients with refractory seizures, open-label/real-world studies support its use in first/second-line settings.

Areas covered

This paper reviews the pharmacology, efficacy, and safety/tolerability of perampanel, focusing on its use as monotherapy or first adjunctive therapy. The safety of perampanel in special populations and its safety/tolerability compared with that of other ASMs is also discussed.

Expert opinion

Perampanel is a favorable candidate for initial or first adjunctive therapy due to its favorable efficacy and safety/tolerability as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy, its long half-life and ease of use, and its limited drug–drug interactions. The proposed mitigation strategies for managing the risk of serious psychiatric adverse events are appropriate patient selection, use of low doses, and slow titration. The growing body of evidence might shift current treatment strategies toward the early use of perampanel and its use at a low dose (4 mg/day).

1. Introduction

Approximately 50% of patients with epilepsy fail to achieve seizure control with first-line anti-seizure medication (ASM); therefore, an alternative monotherapy or concomitant ASMs are commonly prescribed with the aim of improving seizure control [Citation1]. However, adjunctive treatment has been associated with an increased frequency of adverse events (AEs) due to the combination of different AE profiles and potential pharmacokinetic (PK)/pharmacodynamic interactions between the ASMs [Citation2,Citation3]. Thus, ASMs that are well tolerated and effective as monotherapy or first adjunctive therapy are needed for reducing the need for adjunctive ASMs to treat newly diagnosed epilepsy and reducing the number of concomitant ASMs to treat refractory epilepsy. Further considerations when choosing first-line or first adjunctive ASMs include compatibility with other ASMs, convenient route of administration, and long half-life [Citation3,Citation4].

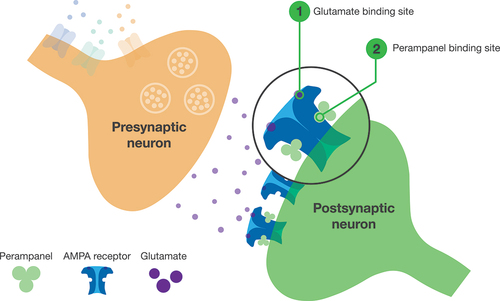

Perampanel, a selective, noncompetitive α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor antagonist is a once-daily oral ASM [Citation5–7] (). Perampanel was initially approved as adjunctive therapy for focal onset seizures (FOS) and later for generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS) in the US and EU, based on pivotal Phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with refractory FOS (Studies 304 [NCT00699972], 305 [NCT00699582], and 306 [NCT00700310]) or GTCS (Study 332 [NCT01393743]) [Citation8–11]. Perampanel monotherapy for FOS later gained approval in the US, based on efficacy and safety/tolerability data extrapolated from pivotal trials of adjunctive perampanel, and in Japan, based on the open-label Phase III Study 342 (NCT03201900) [Citation12,Citation13]. Notably, Study 342 was the first study in which perampanel was administered as first-line monotherapy [Citation12]. Perampanel has been on the market for 10 years (initial approval was in 2012) and thus has a well-established safety profile and acceptable tolerability. As of 22 July 2018, there had been an estimated ~45 million patient-days of perampanel exposure since product launch [Citation14].

There are increasing open-label/real-world data on perampanel monotherapy and first adjunctive therapy across different seizure types and age groups [Citation12,Citation15–26] that complement data from RCTs. Perampanel use with fewer previous/concomitant ASMs was associated with improved seizure control and reduced likelihood of AEs, suggesting an optimized therapeutic benefit when taken early in the treatment pathway [Citation26]. In line with this growing body of evidence, experts justified perampanel use as a first adjunctive therapy in the 2021 Italian consensus, based on its efficacy, tolerability, retention rate, limited drug–drug interactions, and ease of use [Citation4].

This review article summarizes the safety/tolerability of perampanel monotherapy and first adjunctive therapy, and provides an expert opinion on perampanel use in first/second-line settings.

2. Mechanism of action and pharmacology

Perampanel is the only currently approved ASM that acts by selectively blocking AMPA receptors [Citation4–7] (). Perampanel is rapidly absorbed after oral administration and is ~95% bound to plasma proteins [Citation5,Citation6]. It is primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4/5 and has a half-life of ~105 hours [Citation5,Citation6].

Figure 1. Mechanism of action of perampanel.

Perampanel has no apparent drug–drug interactions with other ASMs that worsen tolerability, although its apparent clearance is increased by enzyme-inducing ASMs (EIASMs; including carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin), which decreases perampanel exposure [Citation4–6,Citation27]. Therefore, patients receiving concomitant EIASMs may require a higher perampanel dose to achieve similar efficacy to patients receiving non-EIASMs [Citation28,Citation29].

Perampanel has few drug–drug interactions apart from the effect of concomitant EIASMs on its exposure [Citation5,Citation6]. Although using 12-mg/day perampanel with contraceptives containing levonorgestrel may render these contraceptives less effective, perampanel does not reduce the exposure of these contraceptives when co-administered at 4 or 8 mg/day [Citation4,Citation5].

3. Clinical efficacy

In pivotal RCTs (Studies 304, 305, and 306), adjunctive perampanel demonstrated efficacy in improving FOS control with doses of ≥4 mg/day [Citation8–10,Citation30]. In a pooled analysis of these trials, reduction in FOS was significantly higher with perampanel 4–12 mg/day than placebo (median, 23.3–28.8% vs 12.8%, respectively; all P < 0.01) [Citation31]. The 50% responder and seizure-freedom rates with perampanel 4–12 mg/day were 28.5–35.3% and 3.5–4.4%, respectively, which were significantly higher vs the placebo group (all P < 0.05) [Citation31]. Perampanel 8 mg/day was efficacious in patients with GTCS in Study 332, with median GTCS reduction from baseline of 76.5%, 50% responder rate of 64.2% (GTCS only), and seizure-freedom rate of 23.5% (all seizures) [Citation11].

RCT data showed reduction in seizure frequency with perampanel across multiple seizure types (FOS, FBTCS, GTCS), with greater reductions observed in FBTCS vs FOS [Citation11,Citation31,Citation32]. This supports use of perampanel as a broad-spectrum agent in patients with unclear or multiple seizure types [Citation32].

The effectiveness of perampanel monotherapy and adjunctive therapy has been demonstrated in open-label/real-world studies, with seizure-freedom rates of up to 76% reported in patients with FOS [Citation12,Citation15–25]. Discontinuations due to inadequate therapeutic effect or lack of efficacy were reported in 4.9–6.7% of patients receiving perampanel as a first-line monotherapy [Citation12,Citation18,Citation19].

4. Safety evaluation

4.1. Safety/tolerability of perampanel adjunctive therapy in RCTs

In the pooled analysis of pivotal FOS trials (n = 1038 perampanel-treated patients) [Citation31], treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) occurred in 77.0% of patients receiving adjunctive perampanel (vs 66.5% with placebo); however, fewer TEAEs were reported with lower perampanel doses (61.7% and 64.5% with 2 and 4 mg/day, respectively) than with higher doses (81.2% and 89.0% with 8 and 12 mg/day, respectively). Serious TEAEs were reported in 5.5% with adjunctive perampanel vs 5.0% with placebo; serious psychiatric TEAEs were reported in 1.2% of patients receiving perampanel, the most common being aggression.

In patients with GTCS (n = 81 perampanel-treated patients) [Citation11], TEAEs occurred in 82.7% with adjunctive perampanel 8 mg/day vs 72.0% with placebo. Serious TEAEs were reported in 7.4% with perampanel and 8.5% with placebo; serious psychiatric TEAEs were reported in 2.5% of patients receiving perampanel (one event of suicide ideation and one of suicide attempt).

The most common TEAEs with adjunctive perampanel (≥10% of patients in any treatment group) were dizziness, somnolence, headache, fatigue, and irritability in patients with FOS/GTCS, plus falls in patients with FOS [Citation11,Citation31]. The incidence of TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation was ~10% in perampanel-treated patients (FOS: 9.5% with perampanel vs 4.8% with placebo, most common: dizziness, convulsion, and somnolence; GTCS: 11.1% with perampanel [most common: dizziness and vomiting] vs 6.1% with placebo) [Citation11,Citation31].

Based on pooled data from RCTs (n = 1119 perampanel-treated patients), hostility/aggression-related TEAEs were reported in 12.2% of perampanel-treated patients with FOS/GTCS, including irritability (7.3%), aggression (1.6%), and anger (1.1%) [Citation33]. Homicidal ideation and/or threat was reported in 0.1% of 4368 perampanel-treated patients in Phase II/III trials and their open-label extensions for FOS, and non-epilepsy studies [Citation34].

In a post hoc analysis of low-dose perampanel (4 mg/day; n = 1376), TEAEs were reported in 30.5% of patients, serious TEAEs in 1.2% of patients, and TEAEs leading to discontinuation in 2.0% of patients, suggesting perampanel 4 mg/day is generally well tolerated [Citation30].

4.2. Safety/tolerability of perampanel monotherapy or early adjunctive therapy in open-label/real-world studies

Data from four Eisai-sponsored trials that included patients taking perampanel monotherapy (Study 342 and the real-world Phase IV Studies 504 [NCT02736162] and 506 [PROVE; NCT03208660]) or first adjunctive perampanel (the open-label Phase IV Study 412 [NCT02726074]) were selected by the authors for review in this section [Citation12,Citation15,Citation16,Citation20]. Additionally, a PubMed literature search was conducted in January 2022 to identify other relevant studies of perampanel monotherapy/first adjunctive therapy. Shortlisted articles included the terms ‘perampanel’ AND ‘monotherapy’ OR ‘first’ AND ‘adjunctive’ OR ‘add-on.’ Six additional articles were identified and included, which described studies that were considered relevant in terms of clinical safety and included ≥20 patients receiving perampanel monotherapy (two studies; Toledano Delgado retrospective study and Chinvarun retrospective study) or first adjunctive therapy (four studies; PERADON, Santamarina retrospective study, Rea retrospective study, and COM-PER study) [Citation18,Citation19,Citation22–25].

The most common AEs reported with perampanel in these open-label/real-world studies are summarized in . The incidence of TEAEs ranged from 20.0–75.3% with perampanel monotherapy and 38.1–75.5% with first adjunctive perampanel (including patients taking perampanel second adjunctive therapy in PERADON); serious TEAEs were reported in 0.0–10.1% and 0.0–7.8% of patients, respectively (where reported), and the incidence of TEAEs leading to discontinuation were 6.7–16.3% and 9.5–22.2%, respectively [Citation12,Citation15–25].

Table 1. Summary of study length, TEAEs, and most common TEAEs (occurring in ≥5% of patients) across studies that included patients treated with perampanel monotherapy or early adjunctive therapy (Safety Analysis Sets, where specified).

The incidence of psychiatric TEAEs was generally comparable with perampanel monotherapy/first adjunctive therapy (7.1–37.0% in open-label/real-world studies [Citation18,Citation20,Citation22,Citation24]) and perampanel adjunctive therapy (21.0–24.4% in real-world/post-approval studies [Citation16,Citation26,Citation35] and 24.3% based on pooled RCT data [Citation35]). No changes in cognition were observed with perampanel based on a systematic review including data from an RCT/open-label extension and real-world studies [Citation36].

Evidence suggests that incidence of TEAEs can be dependent on titration schedule. In Study 412, lower incidence of overall TEAEs was observed with slow vs fast titration of perampanel (70.5% with titration at ≥2-week intervals vs 82.9% at <2-week intervals) [Citation20]. This was consistent with a real-world study showing that slow vs fast titration of perampanel (at ≥3–4-week vs 1- or 2-week intervals) was associated with lower incidence of TEAEs (P = 0.006) and numerically lower incidence of psychiatric TEAEs [Citation37].

4.3. Safety in special populations

4.3.1. Pregnant women

There are limited data available for safety of perampanel in pregnancy [Citation38,Citation39]. As of August 2018, 96 pregnancies were reported to have had perampanel exposure: 43 were known to result in normal live births, 28 did not reach full-term, 18 were lost to follow-up, and seven were ongoing at data cutoff [Citation38]. Preclinical data suggest perampanel exposure during pregnancy could potentially lead to diverticulum of the intestine, delays in aspects of physical development, and pregnancy loss [Citation38]. Thus, pregnant women taking perampanel should be carefully monitored (including drug-level monitoring, if available, since dose adjustments may be needed to maintain consistent exposure) and encouraged to enroll in a pregnancy registry to allow more data to be collected in this population [Citation5,Citation38].

4.3.2. Pediatric patients

The incidence of TEAEs with adjunctive perampanel in patients aged 4 to <12 years in Study 311 (NCT02849626) was 89% (most common: somnolence, 26%; nasopharyngitis, 19%; dizziness, irritability, and pyrexia, 13% each) [Citation40]. The incidence of TEAEs and most common types of TEAEs reported in this population were generally comparable with those reported in adolescent and adult patients in RCTs with adjunctive perampanel 4–12 mg/day (total TEAEs, 64.5–89.0%; dizziness, 16.3–42.7%; somnolence, 9.3–17.6%; headache, 11.0–13.3%; fatigue, 7.6–14.8%; irritability, 4.1–11.8%) [Citation11,Citation31]. Interim data from Study 506 also supported use of perampanel monotherapy or adjunctive therapy in patients aged 1 to <18 years with a safety/tolerability profile consistent with that of the overall study population [Citation41].

4.3.3. Older patients

In the small cohort of older patients (n = 28; aged ≥65 years) in pivotal FOS trials, the incidence of TEAEs was similar vs adults aged <65 years; however, falls, dizziness, fatigue, and balance disorders were more common in older patients [Citation42]. In line with the evidence discussed in section 4.2, slow titration is often recommended when initiating a new ASM to reduce the risk of AEs and improve tolerability [Citation20,Citation37,Citation43]. According to the prescribing information, slow perampanel titration is also advised in older patients to reduce the risk of TEAEs that are more common in this population [Citation5,Citation42]. In real-world studies, the safety/tolerability of perampanel in older patients (aged >60 or ≥65 years) was generally in line with that of younger patients and/or the overall study population assessed (total incidence of AEs: 34.8–80.0% in older patients vs 38.5–67.6% in younger patients/overall study population) [Citation19,Citation35,Citation44–46].

4.4. Safety after overdosage

Post-marketing cases of accidental and intentional perampanel overdoses have been reported; the highest reported overdose was 300 mg [Citation5,Citation6]. AEs reported after an overdose include somnolence, stupor, coma, psychiatric or behavioral reactions, altered mental status, and dizziness or gait disturbances; all patients recovered from their TEAEs without sequelae. There is no specific treatment for perampanel overdose and standard supportive treatment for overdose management should be used [Citation5,Citation6].

5. Comparison with the safety/tolerability of other ASMs

The most common TEAEs reported in the prescribing information for perampanel and other commonly used ASMs, including brivaracetam, cenobamate, eslicarbazepine acetate, lacosamide, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam, are described in ; there is some overlap in the most common TEAEs across these ASMs, although direct comparisons cannot be made with these data.

Table 2. Summary of the most common TEAEs (in ≥10% of patients for any ASM and at a higher frequency in the treatment group vs placebo) reported in clinical trials of adjunctive orala PER, BRV, CNB, ESL, LCM, LMT, and LEV in adultsb with FOS,c as described in the US prescribing information for each ASM.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses generally found that adjunctive perampanel was associated with a higher frequency of TEAEs than adjunctive brivaracetam and levetiracetam, and a similar number of TEAEs as adjunctive cenobamate, eslicarbazepine acetate, and lamotrigine [Citation53–55]. However, one systematic review and indirect treatment comparison of adjunctive perampanel and brivaracetam found both ASMs generally had similar TEAE profiles [Citation56]. Dizziness was reported more commonly with perampanel than brivaracetam or lacosamide and occurred at a similar frequency with eslicarbazepine acetate and levetiracetam; somnolence rates were similar for all these ASMs [Citation53,Citation56,Citation57]. Perampanel was generally associated with similar or lower rates of TEAEs leading to discontinuation compared with that of brivaracetam, cenobamate, eslicarbazepine acetate, lacosamide, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam [Citation53,Citation54,Citation56,Citation58], but high-dose perampanel (12 mg/day) was associated with higher discontinuation rates than high-dose levetiracetam [Citation55,Citation58]. A systematic review of observational studies found weighted mean incidences of anger and aggression were similar for perampanel, brivaracetam, levetiracetam, and topiramate but the incidence of irritability was higher for perampanel than for brivaracetam and topiramate [Citation59]. No evidence of increased risk of suicidality was found with perampanel, brivaracetam, cannabidiol, cenobamate, or eslicarbazepine acetate in a meta-analysis of Phase II/III RCTs [Citation60].

6. Summary

Perampanel demonstrated efficacy for improving seizure control: in RCTs, highest seizure-freedom rates (up to 23.5%) were observed with adjunctive perampanel (8 mg/day) in patients with GTCS, whereas in open-label/real-world studies, highest seizure-freedom rates (up to 76%) were reported for perampanel monotherapy (4-mg/day median dose) in patients with FOS. Additionally, perampanel was generally well tolerated, with safety outcomes for perampanel as monotherapy or early adjunctive therapy consistent with those of adjunctive perampanel. The safety/tolerability of perampanel is generally consistent with that of other commonly used ASMs.

7. Expert opinion

7.1. Improvement over other therapies

Although pivotal studies included patients with refractory seizures receiving adjunctive perampanel [Citation8–11], open-label/real-world studies support perampanel use in first/second-line settings. Seizure-freedom rates of up to 76% have been demonstrated with perampanel monotherapy/first adjunctive therapy in patients with FOS in open-label/real-world studies [Citation12,Citation15–25]. Additionally, perampanel use with fewer previous ASMs may be better tolerated based on a bivariate analysis of data pooled from 44 real-world studies (PERMIT) [Citation26]. Furthermore, perampanel monotherapy or adjunctive therapy has demonstrated effectiveness at a low dose (with seizure-freedom rates of up to 63% reported specifically for 4-mg/day perampanel monotherapy in patients with FOS), which may lead to improved tolerability relative to that of higher doses, without compromising efficacy [Citation4,Citation12,Citation30].

Perampanel is an oral tablet taken once daily and has a long half-life [Citation5,Citation6]; therefore, it has favorable PK properties. A long half-life of immediate-release ASMs is associated with reduced pill burden and may particularly benefit patients who are not fully adherent to prescribed medication by reducing the likelihood of seizures occurring after missed doses [Citation61,Citation62]. Furthermore, perampanel has few drug–drug interactions [Citation4–6], allowing perampanel to be easily combined with other medications.

A systematic review and indirect treatment comparison found perampanel had greater efficacy than brivaracetam in patients taking concomitant levetiracetam, possibly because its mechanism of action is different to that of brivaracetam and levetiracetam [Citation56]. Perampanel first adjunctive therapy was associated with higher adherence to treatment regimen and treatment persistence rates than carbamazepine, topiramate, or valproate in a retrospective observational cohort study of claims data in South Korea [Citation63]. Additionally, lower healthcare resource utilization was reported with perampanel vs non-perampanel based ASM combinations in several studies [Citation63–65].

7.2. Impact on current treatment strategies

Key aspects to consider when selecting a first-line ASM are favorable safety/tolerability profile, good efficacy with a low dose, and possibility for slow titration. ASMs that can be used at a low dose may provide benefit in terms of improved tolerability without compromising efficacy [Citation2]. Based on evidence discussed in Sections 3 and 4.2, we believe perampanel is a favorable candidate for a first/second line of therapy.

The use of perampanel as first adjunctive therapy is supported by the 2021 Italian consensus statements, based on the optimal criteria to guide the choice of first adjunctive ASM [Citation4]. It should be noted that many of these criteria also apply to optimal choice of first-line treatment [Citation3]. These consensus statements considered aspects such as efficacy for both FOS and GTCS, tolerability (especially when used with fewer concomitant ASMs), favorable retention rate, and ease of use [Citation4]. Additionally, perampanel fulfills recommendations for achieving a desirable safety profile suggested in Cramer et al. 2010: there is no evidence for the need of laboratory monitoring with perampanel (indicating a lack of organ toxicity), no lethal drug-related AEs have been identified, and AEs reported with perampanel (including psychiatric AEs) can usually be managed with dose adjustments and/or treatment discontinuation [Citation2,Citation4,Citation11,Citation31,Citation35].

7.3. How likely are physicians to prescribe perampanel?

Perampanel is likely to be prescribed due to its route of administration, long half-life, ease of use (i.e. one pill taken once daily), unique mechanism of action, and compatibility with other ASMs. Its unique mechanism of action may lead to improved efficacy with monotherapy (when ASMs targeting other mechanisms have failed) and adjunctive therapy (by targeting multiple mechanisms at once) [Citation3,Citation4,Citation56].

Evidence suggests patients with a history of psychiatric events are predisposed to psychiatric AEs with perampanel. A post hoc analysis of Phase III FOS trials found an increased risk of psychiatric AEs in patients with vs without prior psychiatric history, particularly with higher perampanel doses (8 or 12 mg/day; this association were also observed in the placebo group) [Citation66]. Similarly, in real-world studies, the frequency of psychiatric AEs was significantly higher in patients with vs without prior psychiatric history (P < 0.001) [Citation26,Citation37], whereas no significant effect of perampanel on psychiatric symptoms was observed in the overall study populations [Citation23,Citation67]. Therefore, suggested mitigation strategies that could be considered when prescribing perampanel include appropriate patient selection (e.g. patients without history of psychiatric events and/or who are earlier in their treatment pathway), low starting dose, and slow titration [Citation22,Citation37,Citation66].

7.4. Data gaps

More data on timing of rare/serious AEs during perampanel treatment and the incidence of these AEs across age groups are needed to identify further risk mitigation strategies. Additionally, further data on fetal safety during perampanel use in pregnancy are needed.

7.5. Future implications

Based on the evidence discussed, perampanel shows many characteristics favoring first/second-line use. Previous and new emerging data on efficacy and safety/tolerability of perampanel as monotherapy and first adjunctive therapy, and its effectiveness across a broad spectrum of seizure types, long half-life, limited drug–drug interactions, and efficacy at a low dose (4 mg/day) might lead to its greater use in both settings.

Table

Declaration of interests

J Wheless has received grants support from Aquestive, Eisai, Greenwich, INSYS Inc., LivaNova, Mallinckrodt, Neurelis, NeuroPace, the Shainberg Foundation, and West; has served as a consultant for Aquestive, BioMarin, Eisai, Greenwich, Mallinckrodt, Neurelis; NeuroPace, Shire, Supernus, and Zogenix; and has received speaker bureau honoraria from BioMarin, Eisai, Greenwich, LivaNova, Mallinckrodt, and Supernus. N Chourasia have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Scientific accuracy review

Eisai provided a scientific accuracy review at the request of the journal editor.

Author contribution statement

All authors were involved in the decision to submit this article for publication, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version for submission.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brodie MJ, Barry SJE, Bamagous GA, et al. Patterns of treatment response in newly diagnosed epilepsy. Neurology. 2012;78(20):1548–1554.

- Cramer JA, Mintzer S, Wheless J, et al. Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs: a brief overview of important issues. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(6):885–891.

- Gambardella A, Tinuper P, Acone B, et al. Selection of antiseizure medications for first add-on use: a consensus paper. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;122:108087.

- Bonanni P, Gambardella A, Tinuper P, et al. Perampanel as first add-on antiseizure medication: Italian consensus clinical practice statements. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):410.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FYCOMPA® prescribing information. December 2021. Available at: https://www.fycompa.com/-/media/Files/Fycompa/Fycompa_Prescribing_Information.pdf. Accessed 2022 Feb 28.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). FYCOMPA® Annex I: summary of product characteristics. July 2022. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/fycompa-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 2022 Aug 8.

- Hanada T, Hashizume Y, Tokuhara N, et al. Perampanel: a novel, orally active, noncompetitive AMPA-receptor antagonist that reduces seizure activity in rodent models of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52(7):1331–1340.

- French JA, Krauss GL, Biton V, et al. Adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial-onset seizures: randomized phase III study 304. Neurology. 2012;79(6):589–596.

- French JA, Krauss GL, Steinhoff BJ, et al. Evaluation of adjunctive perampanel in patients with refractory partial-onset seizures: results of randomized global phase III study 305. Epilepsia. 2013;54(1):117–125.

- Krauss GL, Serratosa JM, Villanueva V, et al. Randomized phase III study 306: adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial-onset seizures. Neurology. 2012;78(18):1408–1415.

- French JA, Krauss GL, Wechsler RT, et al. Perampanel for tonic-clonic seizures in idiopathic generalized epilepsy: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2015;85(11): 950–957.

- Yamamoto T, Lim SC, Ninomiya H, et al. Efficacy and safety of perampanel monotherapy in patients with focal-onset seizures with newly diagnosed epilepsy or recurrence of epilepsy after a period of remission: the open-label Study 342 (FREEDOM Study). Epilepsia Open. 2020;5(2):274–284.

- Eisai News Release. Approval of antiepileptic drug Fycompa® in Japan for monotherapy and pediatric indications for partial-onset seizures, as well as a new formulation. 2020. Available at: https://www.eisai.com/news/2020/pdf/enews202004pdf.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 20.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Fycompa Assessment Report. 2020. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/fycompa-h-c-2434-ii-0047-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf. Accessed 2022 Mar 1.

- Gil-Nagel A, Burd S, Toledo M, et al. A retrospective, multicentre study of perampanel given as monotherapy in routine clinical care in people with epilepsy. Seizure. 2018;54:61–66.

- Wechsler RT, Wheless J, Zafar M, et al. PROVE: retrospective, non-interventional, Phase IV study of perampanel in real-world clinical care of patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia Open. 2022;7(2):293–305.

- Yamamoto T, Gil-Nagel A, Wheless JW, et al. Perampanel monotherapy for the treatment of epilepsy: clinical trial and real-world evidence. Epilepsy Behav. 136; 2022 108885.

- Toledano Delgado R, García‐Morales I, Parejo‐Carbonell B, et al. Effectiveness and safety of perampanel monotherapy for focal and generalized tonic-clonic seizures: experience from a national multicenter registry. Epilepsia. 2020;61(6):1109–1119.

- Chinvarun Y. A retrospective, real-world experience of perampanel monotherapy in patient with first new onset focal seizure: a Thailand experience. Epilepsia Open. 2022;7(1):67–74.

- Kim JH, Kim DW, Lee SK, et al. First add-on perampanel for focal-onset seizures: an open-label, prospective study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020;141(2):132–140.

- Im K, Lee S-A, Kim JH, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of perampanel as a first add-on therapy in patients with focal epilepsy: three-year extension study. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;125:108407.

- Abril Jaramillo J, Estévez María JC, Girón Úbeda JM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of perampanel as early add-on treatment in patients with epilepsy and focal seizures in the routine clinical practice: Spain prospective study (PERADON). Epilepsy Behav. 2020;102:106655.

- Santamarina E, Bertol V, Garayoa V, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of perampanel as a first add-on therapy with different anti-seizure drugs. Seizure. 2020;83:48–56.

- Rea R, Traini E, Renna R, et al. Efficacy and impact on cognitive functions and quality of life of perampanel as first add-on therapy in patients with epilepsy: a retrospective study. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;98(Pt A):139–144.

- Canas N, Félix C, Silva V, et al. Comparative 12-month retention rate, effectiveness and tolerability of perampanel when used as a first add-on or a late add-on treatment in patients with focal epilepsies: the COM-PER study. Seizure. 2021;86:109–115.

- Villanueva V, D’Souza W, Goji H, et al. PERMIT study: a global pooled analysis study of the effectiveness and tolerability of perampanel in routine clinical practice. J Neurol. 2022;269(4):1957–1977.

- Takenaka O, Ferry J, Saeki K, et al. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis of adjunctive perampanel in subjects with partial-onset seizures. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;137(4):400–408.

- Gidal BE, Laurenza A, Hussein Z, et al. Perampanel efficacy and tolerability with enzyme-inducing AEDs in patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 2015;84(19):1972–1980.

- Kwan P, Brodie MJ, Laurenza A, et al. Analysis of pooled phase III trials of adjunctive perampanel for epilepsy: impact of mechanism of action and pharmacokinetics on clinical outcomes. Epilepsy Res. 2015;117:117–124.

- Steinhoff BJ, Patten A, Williams B, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive perampanel 4 mg/d for the treatment of focal seizures: a pooled post hoc analysis of four randomized, double-blind, phase III studies. Epilepsia. 2020;61(2):278–286.

- Steinhoff BJ, Ben-Menachem E, Ryvlin P, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive perampanel for the treatment of refractory partial seizures: a pooled analysis of three phase III studies. Epilepsia. 2013;54(8):1481–1489.

- Trinka E, Lattanzi S, Carpenter K, et al. Exploring the evidence for broad-spectrum effectiveness of perampanel: a systematic review of clinical data in generalised seizures. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(8):821–837.

- Chung S, Williams B, Dobrinsky C, et al. Perampanel with concomitant levetiracetam and topiramate: post hoc analysis of adverse events related to hostility and aggression. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;75:79–85.

- Ettinger AB, LoPresti A, Yang H, et al. Psychiatric and behavioral adverse events in randomized clinical studies of the noncompetitive AMPA receptor antagonist perampanel. Epilepsia. 2015;56(8):1252–1263.

- Maguire M, Ben-Menachem E, Patten A, et al. A post-approval observational study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of perampanel as an add-on therapy in adolescent, adult, and elderly patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;126:108483.

- Witt JA, Helmstaedter C. The impact of perampanel on cognition: a systematic review of studies employing standardized tests in patients with epilepsy. Seizure. 2022;94:107–111.

- Villanueva V, Garcés M, López-González FJ, et al. Safety, efficacy and outcome-related factors of perampanel over 12 months in a real-world setting: the FYDATA study. Epilepsy Res. 2016;126:201–210.

- Vazquez B, Tomson T, Dobrinsky C, et al. Perampanel and pregnancy. Epilepsia. 2021;62(3):698–708.

- Maguire M. Response to “Perampanel and pregnancy: could experience be a gloomy lantern that does not even illuminate its bearer?” Epilepsy Behav. 2022;129:108654.

- Fogarasi A, Flamini R, Milh M, et al. Open-label study to investigate the safety and efficacy of adjunctive perampanel in pediatric patients (4 to <12 years) with inadequately controlled focal seizures or generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Epilepsia. 2020;61(1):125–137.

- Segal E, Moretz K, Wheless J, et al. PROVE-phase IV study of perampanel in real-world clinical care of patients with epilepsy: interim analysis in pediatric patients. J Child Neurol. 2022;37(4):256–267.

- Leppik IE, Wechsler RT, Williams B, et al. Efficacy and safety of perampanel in the subgroup of elderly patients included in the phase III epilepsy clinical trials. Epilepsy Res. 2015;110:216–220.

- Seiden LG, Connor GS. The importance of drug titration in the management of patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;128:108517.

- Rohracher A, Zimmermann G, Villanueva V, et al. Perampanel in routine clinical use across Europe: pooled, multicenter, observational data. Epilepsia. 2018;59(9):1727–1739.

- Inoue Y, Sumitomo K, Matsutani K, et al. Evaluation of real-world effectiveness of perampanel in Japanese adults and older adults with epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2022;24(1):123–132.

- Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Foschi N, et al. Adjunctive perampanel in older patients with epilepsy: a multicenter study of clinical practice. Drugs Aging. 2021;38(7):603–610.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). BRIVIACT® (brivaracetam) prescribing information. Sept 2021. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/205836Orig1s011;205837Orig1s009;205838Orig1s008lbl.pdf. Accessed 2022 Feb 28.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). XCOPRI® (cenobamate tablets) prescribing information. August 2020. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/212839s001lbl.pdf. Accessed 2022 Feb 28.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). APTIOM® (eslicarbazepine acetate) prescribing information. March 2019. Available at: http://www.aptiom.com/Aptiom-Prescribing-Information.pdf. Accessed 2022 Feb 28.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). VIMPAT® (lacosamide) prescribing information. October 2021. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/022253s049,022254s039,022255s031lbl.pdf. Accessed 2022 Feb 28.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). LAMICTAL® (lamotrigine) prescribing information. March 2021. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/020241s064,020764s057,022251s028lbl.pdf. Accessed 2022 Mar 8.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). KEPPRA® (levetiracetam) prescribing information. October 2020. Available at: https://www.ucb.com/_up/ucb_com_products/documents/Keppra_IR_Current_COL_10_2020.pdf. Accessed 2022 Feb 28.

- Jeon J, Oh J, Yu KS. A meta-analysis: efficacy and safety of anti-epileptic drugs prescribed in Korea as monotherapy and adjunctive treatment for patients with focal epilepsy. Transl Clin Pharmacol. 2021;29(1):6–20.

- Lattanzi S, Trinka E, Zaccara G, et al. Third-Generation antiseizure medications for adjunctive treatment of focal-onset seizures in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Drugs. 2022;82(2):199–218.

- Zhu LN, Chen D, Xu D, et al. Newer antiepileptic drugs compared to levetiracetam as adjunctive treatments for uncontrolled focal epilepsy: an indirect comparison. Seizure. 2017;51:121–132.

- Trinka E, Tsong W, Toupin S, et al. A systematic review and indirect treatment comparison of perampanel versus brivaracetam as adjunctive therapy in patients with focal-onset seizures with or without secondary generalization. Epilepsy Res. 2020;166:106403.

- Zhuo C, Jiang R, Li G, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of second and third generation anti-epileptic drugs in refractory epilepsy: a network meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):2535.

- Zaccara G, Giovannelli F, Giorgi FS, et al. Tolerability of new antiepileptic drugs: a network meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(7):811–817.

- Steinhoff BJ, Klein P, Klitgaard H, et al. Behavioral adverse events with brivaracetam, levetiracetam, perampanel, and topiramate: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;118:107939.

- Klein P, Devinsky O, French J, et al. Suicidality Risk of newer antiseizure medications: a meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(9):1118–1127.

- Gidal BE, Ferry J, Reyderman L, et al. Use of extended-release and immediate-release anti-seizure medications with a long half-life to improve adherence in epilepsy: a guide for clinicians. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;120:107993.

- Gidal BE, Majid O, Ferry J, et al. The practical impact of altered dosing on perampanel plasma concentrations: pharmacokinetic modeling from clinical studies. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;35:6–12.

- Lee JW, Kim JA, Kim MY, et al. Evaluation of persistence and healthcare utilization in patients treated with anti-seizure medications as add-on therapy: a nationwide cohort study in South Korea. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;126:108459.

- Laliberté F, Duh MS, Barghout V, et al. Real-world impact of antiepileptic drug combinations with versus without perampanel on healthcare resource utilization in patients with epilepsy in the United States. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;118:107927.

- Faught E, Li X, Choi J, et al. Real-world analysis of hospitalizations in patients with epilepsy and treated with perampanel. Epilepsia Open. 2021;6(4):645–652.

- Kanner AM, Patten A, Ettinger AB, et al. Does a psychiatric history play a role in the development of psychiatric adverse events to perampanel … and to placebo? Epilepsy Behav. 2021;125:108380.

- Deleo F, Quintas R, Turner K, et al. The impact of perampanel treatment on quality of life and psychiatric symptoms in patients with drug-resistant focal epilepsy: an observational study in Italy. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;99:106391.