ABSTRACT

Long seen as divergent in nature, the fields of populist studies and social movement analysis have rarely been the focus of cross-disciplinary research. This paper, by encouraging such convergence makes two significant contributions to both the study of populism and social movements. First, by combining a discourse theoretical approach to populism with social movement theories of abeyance and ‘cultural repertoires’, it examines populist discourse as a form of contentious politics. Second, using primary and secondary sources of both a textual and visual nature, it applies this framework to a case study of North Italian populist regionalism and in doing so takes a diachronic approach to populism. This allows for a clearer understanding of not only of the decline of certain populist movements, but also how these movements’ repertoires are transmitted between separate waves of activism.

1. Introduction

For some time, the respective fields of populist studies and social movement analysis have tended to diverge from each other with ‘neither scholarly tradition … [devoting] much energy to a search for common spawning grounds or points of intersection between the two phenomena’ (Roberts, Citation2015, p. 681).

Despite these divergences, however, there have been signs of increasing collaboration between populist studies and social movement analysis. Recent literature has recognised that ‘studying social movements under the framework of populism opens up the prospect of productive cross-fertilisation between political scientists and social movement theorists.’ (Aslanidis, Citation2017, p. 306). Following this logic, I sustain that the same is true with regards to the study of populist movements under the framework of social movement theory. By recognising populism’s latent nature, this paper contributes to the field of populism studies by analysing it as a socio-political phenomenon under the social movement theory of abeyance (Roberts, Citation2015, p. 692).

Abeyance theory, developed by Mizruchi (Citation1983) and later enhanced by contributions from various scholars, forms part of a wider literature on historical sociology which engages with cycles of mobilisation or waves of activism of social movements. It helps explain how ‘repertoires of contention’ survive periods of inactivity ((Tilly, 2)) During a period of abeyance, social movements ‘often retreat from public visibility’ and move into ‘stand-by mode, […] ‘temporary suspension’ or ‘hibernation’(Gade, Citation2019, p. 73). In terms of populist studies, abeyance matters as it allows for a clearer understanding of not only of the decline of certain populist movements, but also how populist discourse is transmitted between cycles of moblisation or waves of activism. With this in mind, my paper addresses the following research question:

How can populist discourse survive a period of political inactivity?

Following this introduction, the article will address this question in 3 sections. The first section reviews literature on abeyance theory and populism and then develops a conceptual framework to examine the creation, maintenance in abeyance and transmission of populist regionalist discursive repertoires .

Table 1. (Newth, Citation2018, p. 297).

The second section consists of a case study which illustrates how the decline of one period of populist regionalist activism in North Italy the 1960s represented by Movements for Regional Autonomy (MRAs) formed part of a longer process of ‘abeyance’ during which there was a continuity of populist regionalist discourse through a maintenance of discursive repertoires. These would later be adopted and adapted by the populist regionalist Lega Nord party, which prior the advent of Matteo Salvini and his nationalist turn, was led between 1991 and 2012 by Umberto Bossi and acted as junior coalition partner in four Silvio Berlusconi led administrations. (Albertazzi et al, Citation2018).

The case study demonstrates how populist regionalist discursive repertoires developed in the 1950s by North Italian MRAs were subsequently maintained by rump movements i.e. cadres of committed activists, during a period of abeyance between 1960 and 1980; it then demonstrates how these repertoires were transmitted to a new wave of activists through inter-generational links of friendship, rivalry and family.

The sources used are both primary and secondary and were produced by both MRA and Lega Nord activists. Interviews with Roberto Gremmo, former Piedmontese regionalist activist in Piedmont, and Giuseppe Sala, son-in-law of 1950s Lombard autonomist, Gianfranco Gonella, helped shed light on the period of abeyance in question in this article.Footnote1 The final concluding section discusses the significance of abeyance for the study of political movements in general and populist movements in particular.

2. Conceptual framework

The following section examines how and to what extent the two different theories of populism and abeyance, despite having their own unique intellectual traditions, hold the potential to complement each other. It then establishes a framework which allows for the examination of the transmission of populist repertoires.

Populism and abeyance

Populism has come to represent a high degree of contestability, the acknowledgement of which has by now become an ‘axiomatic feature’ of literature on the subject (Moffit & Tormey, Citation2013, p. 382) Differences between these approaches are by no means negligible with long-standing debates sometimes leading to refutations of paradigms (Aslanidis, Citation2015). Nevertheless, it can also be argued that a certain ‘centre of gravity’ can be found on populism’s key features (Heinisch et al., Citation2020) in particular with regards to a manichean view of society which centres around ‘the presence of an antagonistic ‘relationship’? between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ and ‘a vertical down/up axis that refers to power, status and hierarchical position’ (De Cleen et al 2019).

This vertical positioning is relevant in distinguishing populism from other concepts with which it is often conflated, such as nationalism and nativism. Recent debates has viewed populism and nationalism as ‘intersecting and mutually implicated […] fields of phenomena’ (Brubaker, Citation2020, p. 55). Such an argument posits that populist discourse is mutually constituted by ‘vertical opposition to those on top and horizontal opposition to outside groups or forces’ (Brubaker, Citation2020, p. 55). Instead, I support a clearer differentiation between populist and nationalist discourses in that the central theme of such nationalism is not the staging of an antagonism between a ‘people’ and an ‘elite’, but rather the opposition of an ethnic community with its alleged dangerous ‘others,’ (Stavrakakis & De Cleen, Citation2017; Citation2020).

This helps avoid populism being associated exclusively with ideologies and narratives of the far-right which has resulted at times in ‘populist hype’, i.e. the skewing of the meaning of the populist phenomenon, the exaggeration of the significance of the populist phenomenon and the characterization of this phenomenon in apocalyptic terms (Glynos & Mondon, Citation2016).

In this paper, I interpret populism as

a dichotomic discourse in which “the people” are juxtaposed to ”the elite” along the lines of a down/up antagonism in which “the people” is discursively constructed as a large powerless group through opposition to “the elite” conceived as a small and illegitimately powerful group.” (Stavrakakis & De Cleen, Citation2017, p. 310)

Populism therefore relies on a ‘discursive construction and interpellation of “the people” as a collective subject and key actor of social change’ (Katsambekis, Citation2017, p. 204). This is due to the fact that

populists are placed on the side of ‘the people’, pledging to serve the popular will and reinforce popular sovereignty … making the political process more open and accountable to popular demands and grievances against power-holders and oligarchs’(Katsambekis, Citation2017, p. 204)

Populism should be judged ‘by its usefulness in capturing a relevant (populist) aspect of social reality.’ (De Cleen et al., Citation2018, p. 3). In the case of this paper, this aspect of social reality relates to demands for greater regional autonomy put forward by regionalist movements in both the 1950s and later in the 1980s/90s. These movements used populist regionalism i.e. a populist articulation of regionalist ideology to depict ‘the hard-working and virtuous region as exploited by the political elites’ (Newth , Citation2018)

This reflects Katsambekis’ observation that it is “the specific ideology behind targeting an ‘elite’ and calling upon a ‘people’ that defines [the] essence and orientation’ of populism (Katsambekis, Citation2017, p. 205). Such a definition of populism as a discourse or style means that it can be used by a multitude of movements, even if they have almost nothing else in common’ (Diamanti & Lazar, Citation2018)

Particularly useful in terms of populist regionalism is the notion of what Taggart (Citation2000, p. 98) labels as a ‘heartland’ i.e. ‘a single territory of the imagination’. Not only do populist regionalists use ‘a meshing of a “heartland” based on a sub-national community with a wider critique of central state politics’ (Taggart, Citation2017, p. 250) but also ‘put forward their respective regionalist programmes as the best way to return popular sovereignty to the heartland.’ (Newth, Citation2019, p. 390).

Populism appears to be a recurrent but also somewhat intermittent phenomenon through political history (Canovan, Citation1982, Citation1999, Citation2004). With this in mind, what efforts have already been made to understand populism’s latent nature? Social movement theory has been used in conjunction with populism to demonstrate how social movements and populism, ‘appear sequentially, with mass social protest often preceding and setting the stage for populism’ (Roberts, Citation2015, p. 681). Diani (Citation1996, p. 1054), has previously explained the success of the Lega Nord’s populist discourse in the early 1990s by linking ‘the congruence between the leagues’ message and the master frame that characterized the political opportunity structure of the early 1990s in Italy. Such theory has also been used to demonstrate that ‘populism is not the exclusive domain of political parties and their leaders’ but can be forged outside established political institutions in a grassroots fashion, instigated by anonymous political entrepreneurs and substantiated through protests and social movements. (Aslanidis, Citation2017, p. 305).

However, what is often not examined in adequate detail is the issue of how and by what form of agency populist discourses are preserved and transmitted during times when populism has apparently disappeared from the public sphere. It is here that abeyance theory allows a more diachronic approach to populism due to the fact that it ‘fits with a historical sociology that strives to identify and explain not just passing phenomena but also longer-term patterns of social interactions.’ (Veugelers, Citation2011, p. 244).

The understanding of abeyance owes much to the conceptual work of Ephraim Mizruchi who coined the term as a theory of social control in which marginal groups are integrated or put ‘under the surveillance and control of functionaries in both institutionalised organisations and by control of peers in less formally organised groups’ (Mizruchi, Citation1983, p. 163). These organisations temporarily retain potential challengers to the status quo, thereby reducing threats to the larger social systems (Mizruchi, Citation1983, p.17; Taylor, Citation1989, p. 762).

Further to decline and absorption, abeyance theory also sustains the idea that ‘social movements persist over long periods in various stages of mobilization, decline, or abeyance. During abeyance, movements sustain themselves but are less visible in interaction with authorities’ (Meyer & Sawyers, Citation1999, p. 188). In other words, ‘the abeyance of a social movement […] aims to convey a state of hibernation with a liability to further mobilization in the future.’ (Taylor Citation1997: 409, cited in Bagguley, p. 171). Therefore, while a number of theories ranging from ‘cycles of contention’ (Tarrow, Citation2011), ‘collective action frames’ (Benford & Snow, Citation2000) and ‘path dependence’ (Mahoney, Citation2000) have developed over the years to examine the decline and re-emergence of social movements, where abeyance differs from these theories is in not simply concentrating on the moments when movements are at their most visible and instead recognising ‘the continuity between visible challenges’ (Meyer & Sawyers, Citation1999, p. 188).

The potential convergence between populism and abeyance has been touched on by Aslanidis who observes that often ‘populist identities remain latent, “in abeyance”, awaiting political reactivation, bound to inspire and inspire again, sparing activists the need to reinvent the wheel.’ Such (re)activation can come from ‘fertile political opportunities such as an economic crisis, a sudden disaster, or a high-profile case of corruption (Aslanidis, Citation2017, p. 313). Aslanidis also notes that ‘failed attempts at reaping immediate political benefits do not necessarily signal the political irrelevance of grassroots populist episodes. Once it establishes itself, the sheen of “the people” will rarely dull’ (Aslanidis, Citation2017, p. 313).

While such insights are invaluable in observing how populism re-emerges throughout history, they are in need of both greater elaboration and nuance. Until now not enough attention has been dedicated to the fundamental role of abeyance in the decline of movements and the maintenance and subsequent transmission of populist discourse from one period of activism to another. Furthermore, the contextual differences between these waves of activism do indeed entail, if not a total reinvention of the wheel, then at least a modification of its parts by a second wave of activism to suit the new socio-political reality.

Having established how abeyance theory may account for the latent nature of populism, the remaining paragraphs of this section establish a conceptual framework which allows for the analysis of the survival of populist discourse.

Repertoire creation, maintenance in abeyance and transmission

Social and political movements often draw on a toolkit of strategies and tactics in order to make and receive claims in a broader context of ‘contentious politics’, which had been used by previous waves of activism (Tilly, Citation1978, Citation2008) (Tarrow, Citation1993).

The various features of this toolkit, have been labelled by Tilly (Citation1978, Citation2008) as ‘repertoires of contention’; the choice of the word repertoire as a ‘theatrical metaphor […] calls attention to the clustered, learned, yet improvisational character of people’s interactions as they make and receive each other’s claims.’ (Tarrow & Tilly, Citation2007, p. 441). In terms of ‘contentious politics’, this term has been used to denote a ‘collective political struggle’ or moreover

episodic, public collective interaction among makers of claims and their objects when (a) at least one government is a claimant, an object of claims, or a party to the claims and (b) the claims, would, if realised, affect the interests of at least on of the claimants.’ (Tarrow & Tilly, Citation2007)

In terms of collective action, such ‘contentious repertoires’ have been referred to as ‘arrays of performances that are currently known and available within some set of political actors. These more practical manifestations may involve, among many other actions ‘some mixture of public meetings, press statements, demonstrations and petitions’ (Tilly, Citation2008, p. 15).

However, as Swidler (Citation1986, p. 277) has correctly pointed out

people do not build up lines of action from scratch […] Instead they construct chains of action beginning with at least some pre-fabricated links. Culture influences action through the shape and organization of those links

Actors can therefore draw on ‘cultural repertoires’ which consist of a ‘toolkit of habits, skills, and styles from which people construct ‘strategies of action’ (Swidler, Citation1986, p. 273). As different waves of activism may use the same symbols, discourse and styles but ‘individuals and groups know how to do different kinds of things in different circumstances’ (Swidler, Citation1986, p. 277), certain cultural repertoires may need to be (re)-elaborated and adjusted to suit different contexts. Indeed, the diverse and sometimes contradictory nature of culturally shaped political strategies has previously been demonstrated in the context of territorially-based political activism in North Italy (Caruso, Citation2015; Vitale, Citation2015). This is due to the fact that, as noted by Sewell (Citation2005, pp. 89–91), cultures are not only ‘loosely integrated, ‘contested’ and ‘subject to constant change’, but they can also be ‘contradictory’ insofar as certain symbols, for example, may have simultaneously two opposing meanings.

One of the ‘styles’ within this cultural tool-kit is that of discourse or discursive repertoires which are the ‘recognizable routines of arguments, descriptions and evaluations found in people’s talk often distinguished by familiar clichés, anecdotes and tropes (Reynolds & Wetherell, Citation2003, p. 496). The aforementioned importance of context is highlighted by the fact that such discursive repertoires operate within broader “discursive fields” i.e. sets of discourses – such as discourses of “nationalism,” “citizenship,” or “gender” – that change slowly over time’ (King, Citation2007, p. 303). Challengers, therefore, seek both to legitimize their claims within the existing ideology of domination and to subvert some of the powerholder’s justifications’ (Steinberg, Citation1995, p. 60).

Due to the fact that ‘repertoires involve repetition […] for innovative tactics to diffuse and ignite further activism, they need to be recognizable, that is, borrow from previous routines of claim making’ (Grimm and Harders, Citation2018, p. 4). Indeed, ‘the collectively shared social consensus behind a repertoire is often so established and familiar that only a fragment of the argumentative chain needs to be formulated’ (Reynolds & Wtherell, Citation2003, p. 496)

In order for such repertoires to be evoked, however, they must often survive periods of inactivity. Following a process of decline, ‘the move into abeyance fragments social movements and marginalizes some parts of the movement, whilst co-opting others into conventional political processes’ (Bagguley, Citation2002, p. 173). Central to the maintenance of repertoires is ‘the creation of abeyance structures that retain and sustain activists between waves of mobilization’ (Bagguley, Citation2002, p. 171) and act as ‘a holding process by which movements sustain themselves in non-receptive political environments and provide continuity from one stage of mobilisation to another.’ (Taylor, Citation1989, p. 761).

As noted by Sawyers and Meyer

during abeyance, movements sustain themselves, but are less visible in interaction with authorities. At the same time, values, identity and political vision can be sustained through internal structures that permit organisations to maintain a small, committed core of activists and focus on internally-oriented activities. (Citation1999, p. 188).

Indeed, Melucci has highlighted that ‘during periods of latency “submerged”, networks of actors continue to interact, exchange experiences and generate ideas.’ (Melucci, Citation1989, as cited in Beaumont et al., Citation2020). The activist networks which play such a central role in the maintenance of repertoires and identities have been referred to as ‘rump movements’ by Taylor (Citation1989) in her research on the The National Woman’s Party in the United States. Following the granting of national suffrage in 1920, this group stopped making demands of the authorities. Nevertheless, the survival of a core of committed activists in the subsequent four decades ‘provided the organizational basis, collective action repertoires, and collective identity for a new generation of American feminists in the 1960s’ (Taylor, Citation1989, as cited in Gade Citation2018).

Therefore, while activists may be confronted with ‘a non-receptive political and social environment’ (Taylor, Citation1989, p. 762) during a period of hiatus ‘remnants of past episodes of contention survive: new waves of contention may be expected, especially if the external context provides an opportunity’ (Fillieule, Citation2006, p. 207, as cited in Gade, Citation2019, p. 59). These new waves of contention depend on the transmission of past repertoires which had previously been held in abeyance and re-emerge ‘through imitation of other observed performances […] and handed-down templates and, perhaps most centrally, through interactions with other actors and parties involved’ (Alimi, Citation2015, p. 410).

In terms of how such transmission is possible, there are three aspects which should be highlighted; family, friendship and rivalry. With regards to family and inter-generational links as means via which ideas may be transmitted between one generation of activism and the next, this has been closely examined by Veugelers in his study on neo-fascism. Veugelers used abeyance theory to ‘document the preservation of a neo-fascist mobilisation potential after 1945 through the parent–child transmission of frames’ (Veugelers, Citation2011, p. 241), also highlighting how family acts as an abeyance structure by ‘harbouring a latent mobilization potential even when parents are not activists (Veugelers, 2010, p. 244). What played a vital role in the transmission of ideas was that ‘a minority of families dissented from the officially sanctioned memory of a unified national and patriotic resistance’ and taught ‘their children oppositional framings of history, society and politics (Veugelers, 2010, p. 242). Furthermore, Press has demonstrated that transmission may be possible through ‘professional ties or friendships, or both’ (Press, Citation2015, p. 173). Through such relationships, ‘a variety of tactics, individuals, small groups and, on occasion mass participation’ may play a key role in ‘transmitting repertoires’ (Press, Citation2015, p. 152). Further to friendship, however, Newth (Citation2018) has also highlighted how rivalry between activists can encourage transmission of repertoires as a battle over ownership of a particular discourse leads to the reproduction of repertoires.

3. Case study: two waves of North Italian populist regionalism

The following section presents a case study which illustrates three north Italian populist regionalist ‘cultural repertoires’, namely ‘The North exploited by Southern elites’, ‘A Free Padanian Heartland’ and ‘The Battle of Legnano’, which formed part of a ‘strategy of action’ of the 1950s of North Italian Movements for Regional Autonomy (MRAs). It then examines how such repertoires were maintained over a 20-year period of abeyance between 1960 and 1980 and subsequently transmitted in the 1980s at the beginning of a second period of populist regionalist activism instigated by North Italian ‘regionalist leagues’, later to form the Lega Nord.

In 1946 and 1947 two associations were formed to campaign for the inclusion of the regional statute in the Italian Republican Constitution, following the end of the Second World War (Paini Citation1949). These respective organisations, the Associazione Regionale Italiana (ARI) of Turin and the Movimento per le Autonomie Locali (MAL) in Bergamo would later evolve into The Movement for Piedmontese Regional Autonomy (The MARP) and the Movement for Bergamascan Autonomy (the MAB), to protest against the fact that the ‘ordinary regions were simply not set up’ following the constitution of the post-war Italian Republic in 1948 (Hine, Citation1996, p. 111), and stand in the 1956 administrative elections.

The MRAs’ strategy of action was couched in a context of regionalism, which emphasised the imperative of Italian unity following the transition from Fascism to Democracy. As a result, any suggestion of regional autonomy was accompanied by a profession of loyalty towards Italy (Newth, Citation2018). The MRAs, thus, pointed to the inactive regional statutes in the Constitution to justify their political programme, claiming regional autonomy would strengthen Italian unity, in an attempt to legitimize their claims within the hegemony of centralism.

While the MAB was a direct descendent of the MAL, the Piedmontese MARP had been founded in 1955 by Enrico Villarboito but was taken over by members of the ARI in 1956. Although ousted by the ARI’s members, Villarboito remained a significant figure in populist regionalism for two key reasons. First, he formed two further movements, namely the Movimento Autonomie Regionali (the MAR) and the SCOPA (Servire Coscientemente Ogni Pubblica Amministrazione – To serve consciously every public administration) both of which ensured the proliferation of populist discourse in the 1950s. While acting as an acronym for a cumbersome title, the SCOPA, meaning ‘broom’ in Italian, gave the impression that this party would ‘sweep up’ politics in Piedmont, thus conveying the image of a party led by the people v the elites.

Second, Villarboito would also later form a direct link between the first and second waves of activism through his friendship with Roberto Gremmo, with whom he would collaborate in regionalist organisations in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Also present in the MARP were Pietro Molino, and Antonio Brodrero, who would become representatives for Lega Nord Piemont. (Piemont Autonomista, Citation1987; La Stampa, Citation1994).

In the lead up to the 1956 administrative elections in Turin, the MARP published the following message to its voters via Piemonte Nuovo stating,

Torinesi! […] We’ve had enough of politicians and bureaucrats! It’s time to leave the door open for a breath of fresh air […] the MARP is not a political movement, but a movement tired of the partitocrazia with one aim: regional autonomy. (Piemonte Nuovo, Citation1956a)

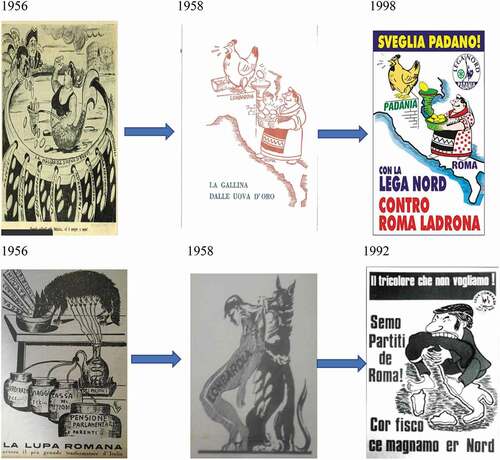

This highlights the first cultural repertoire of ‘a Northern underdog exploited by Southern and centralist elites.’ At the centre of this populist regionalism was an anti-political and anti-southern discourse protesting against a ‘partitocrazia’ (regime of parties) whilst demanding fewer contributions to the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno (The fund for the South) and a stop to post-war migration from the South to the North (Newth, Citation2019). This is captured by imagery released by the MRAs throughout the 1950s which depicts a hard-working north being sucked dry by the parasitic south ().

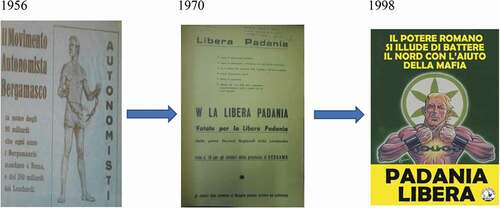

A second cultural repertoire of a ‘Free Northern/Padanian’ heartland is also reflected in imagery produced by the MRAs. An image released by the MAB in 1956 shows a slave breaking free of the bondage of Roman power and bureaucracy () reflecting how the MRAs defined the North as liberal and free, while Rome was depicted as responsible for imposing a suffocating centralism on the region. While the MARP stated that it was ’a movement conducted by free men who were tired of the partitocrazia and the bureaucratic centralism of Rome,’ Guido Calderoli, put forward a call to ‘free Bergamascans from bureaucratic slavery (Piemonte Nuovo, Citation1956; Calderoli, Citation1958, p. 72).’

The 1956 administrative elections saw the MRAs elect communal and provincial councillors. (Author, 2018). Those for the MAB were Guido Calderoli, grandfather of future Lega Nord senator, Roberto, and Ugo Gavazzeni who would later play a key role in the maintenance of repertoires in the 1960s and 1970s. These results gave the idea of a ‘Free Northern/Padania heartland’ extra impetus and on 19 January 1958, the MARP and the MAB allied with other North Italian autonomist movements from Lombardy, Trento, the Veneto and Liguria in Verona, to form the Movimento per l’Autonomia Regionale Padane (Movement for Padanian Regional Autonomy or ‘MARPadania’). ‘Padania’ in this case represented northern Italy across which these groups wished to campaign for greater regional autonomy in the 1958 general election (Newth, Citation2018; Piemonte Nuovo, Citation1958a; La Stampa, Citation1958).

The juxtaposition of ‘the people’ against the ‘Roman elites’ is present in a further cultural repertoire of ‘the Battle of Legnano’. In 1959, the MAB launched a newspaper entitled La Regione Lombarda, using a symbol of Alberto Da Giussano and the Oath of Pontida, to hark back to the 1179 Lega Lombarda’s victory at ‘battle of Legnano’ and reappropriate this medieval event as a symbol of ‘independence from Roman centralism.’ (Gremmo, Citation1992, p. 75).

In the early 1960s, divisions emerged between those who wished to keep the MRAs alive and those who wished to see them merge with larger political organisations (Author, 2018). While in 1960, members of the MAB joined a Christian Democrat (DC) list (Freddi, Citation1963, p. 20), in 1962, similar plans were put into motion to merge the MARP with the Italian Social Democratic Party (PSDI) (Turn National Archives, Citation1962a). The role of the PSDI and the DC in the abeyance process was, therefore, in facilitating a process of absorption of the MARP and the MAB following the movements’ respective decline. (Mizruchi, Citation1983, p. 2).’

On the Piedmontese side, an initial rump movement was led by former MARP exponent, Franco Bruno who in the 1964 local elections attempted to present a second MARP list at the 1964 election entitled MARP bis (La Stampa, Citation1964) and continued to campaign for regional autonomy into the 1960s, ensuring a survival of populist regionalist discourse (Turin National Archives, Citation1962b). With the implementation of the 1970 regional reforms and the implementation of the region in Italy, however, demands shifted towards a ‘special statute’ and would see the emergence of a new rump movement named Federassion Piemonteisa which involved another of the MARP’s former members, Toni Brodrero.

With regards to the MAB, several autonomists did not opt to join the DC’s electoral list, but, led by former respective communal and provinical councillors Guido Calderoli and Ugo Gavazzeni who chose instead, to ‘assume the new name of Autonomisti’. This rump movement would later evolve into the Unione Autonomisti d’Italia (UAI) (Freddi, Citation1963, pp.20–21; Bergamo Communal Archive, Citation1960; L’Eco di Bergamo, Citation1960). The UAI allied itself to the Sud-Tiroler Volkspartei (SVP) in a movement entitled La Stella Alpina, which also involved the aforementioned MARP activist Toni Brodrero. This provides evidence of how Lombard and Piedmontese regionalist movements continued to collaborate in the 1960s.

The UAI survived into the 1970s and provided continuity of populist regionalist discourse in a seeming period of hiatus (Newth, Citation2018). On 17 December 1968, Gavazzeni’s UAI met at Pontida to celebrate the 18th centenary celebration of the ‘Oath of Pontida’ by proposing a ‘new Lega Lombarda’ (Boulliaud and DeMatteo, Citation2004, p. 43) (L’Eco di Bergamo, Citation1968). Following the 1970s’ regional reforms a poster was produced which saw the re-emergence of the terms ‘Padania’ and ‘Padanians’ to denote a North-Italian identity with pledges made to ‘defend Padanian work and Padanian traditions’, (UAI, Citation1970) ().

In 1980, a second wave of activism began when Roberto Gremmo formed one of the first regionalist leagues by using the acronym of M.A.R.P for Movimento Autonomista Rinascita Piemonteisa (Movement for a Piedmontese Rebirth). In doing so he revived a logo, which had promoted populist regionalism in the 1950s. (Newth, Citation2018). Two years later, Umberto Bossi founded the Lega Lombarda; however, as Passalacqua (Citation2009, p. 17) notes, ‘paradoxically, the Lega Lombarda did not come from Lombardy’ and was the ‘little brother’ of Gremmo’s movement. Indeed, Bossi wrote in a 1983 edition of its mouthpiece Lombardia Autonomista, ‘our thanks go to Roberto Gremmo of M.A.R.P, who … allows us to publish Lombardia Autonomista as the supplement of Rinascista Piemontese.’ (Bossi, Citation1982). The fact that Bossi – a hugely important figure in the Lega’s success – was first active in a movement which had roots in Piedmont meant he was influenced by Gremmo, who had in turn been influenced by his friendship with former MARPista, Toni Brodero (Gremmo Citation2016).

Brodrero, who had also been active in various rump movements, in 1978 had collaborated with Gremmo to write l’Oppressione Culturale Italiana in Piemonte, (Italian cultural oppression in Piedmont) pitting the ‘Piedmontese people’ against the ‘Roman bureaucrats’(Brodrero & Gremmo, Citation1978, p. 14). A year prior to this book’s publication, Gremmo had also formed L’Unione Ossolana (L’UOPA) which whilst having its origins in Piedmont was not restricted to this region but instead represented a connection between the Piedmontese and Lombard autonomists. Cachafeiro (Citation2001, p. 76) observes that ‘in the Lombard region, [Umberto] Bossi launched in the province of Varese, l’Unione Nord-Occidentale per i Laghi pre-Alpini’, therefore working with Gremmo in the second wave of populist regionalism.

These friendships turned to rivalry in 1987 when Brodrero abandoned Gremmo to join a rival faction formed by Piedmontese folk singer Gipo Farassino Piemont Autonomista (Cachafeiro, Citation2001). Brodrero’s defection to Farassino’s movement established a rivalry between Piemont Autonomista and Umberto Bossi’s Lega Lombarda on one side and Gremmo’s renamed movement Union Piemonteisa on the other and a proliferation of materials to claim ownership of north Italian regionalism. Activists in Piemont Autonomista published an article paying tribute to the ‘important cultural figure of Toni Brodrero’ stating that ‘the seed, planted 35 years ago by MARP was not in vain but instead has developed like never before.’ (Borsotti, Citation1987). The same article also praised former MARP leader, Enrico Villarboito in an attempt to attract him to Piemont Autonomista. However, the MARP founder instead came out in support Gremmo’s radical plan for the creation of a separate ‘North-West alpine state’, joining Gremmo in renaming Union Piemonteisa as the Lega Alpina (La Stampa, Citation1989).

In terms of the Lombard section, further to Bossi’s friendship and later rivalry with Gremmo, it was the Calderoli family which helped the transmission of repertoires. Guido Calderoli had been a key figure in both the MAB and the subsequent Autonomisti. It was subsequently his son, Innocente, and grandson Roberto, (of whom Innocente was the uncle, not father) who helped form the Bergamascan section of the Lega Lombarda in 1985 (Bossi, Citation1999, pp. 61–62). Calderoli was elected to the Bergamo communal council (Bergamo Election Results, Citation1990), thus representing a ‘family tradition which helped push the movement forward between the two periods’ (Sala, Citation2016). While Giuseppe Calderoli, Roberto’s father was not involved in such activism, repertoires which encouraged dissent from ‘the officially sanctioned’ centralist form of governance in Italy were nevertheless transmitted to Roberto via his uncle and grandfather. This demonstrates how family can harbour ‘a latent mobilisation potential even when parents are not activists’ (Veugelers, Citation2011, p. 244)

Under the leadership of Bossi in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the leagues’ strategy of action became increasingly organised, culminating in the institutionalisation of the movement into single federation of the Lega Nord in 1991. This brought together sections from Lombardy, Veneto, Liguria, Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna and Piedmont succeeding in performing lead a ‘headlong attack’ against the centralist state (Cento Bull, Citation2015, p. 205). This had not been the case with the MARPadania in 1958, and was linked to important contextual differences between the first and second wave of populist regionalism.

While the MRAs had challenged the parties of the Republic, they also advocated for national unity and their regionalist message did not share the anti-nation-state message which became central to the ideology of the Lega. By the time the regionalist leagues emerged, the regional statutes for which the MRAs had campaigned had been active for nearly a decade and the Lega’s populist regionalism aimed to fragment the state and weaken the Italian unity which its precursors had defended, reflecting a ‘reaction against a heavily bureaucratized welfare state’ with demands for a ‘neo-liberal and autonomist’ policies In Italy. (Cento Bull & Gilbert, Citation2001). The end of the Cold War, a major corruption scandal in 1992 and subsequent electoral reform in 1993, saw all old parties ‘either wiped out or … much weakened’ (Sassoon, Citation1995, p. 128). These contextual differences necessitated if not a complete ‘reinvention of the wheel’, then a modification of pre-existing populist regionalist cultural repertoires.

In terms of ‘a Northern underdog exploited by Southern and Centralist elites’ a series of Lega posters which ‘showed a pained-looking Lombard hen laying golden eggs into a basket held by a distastefully caricatured Roman matron’ were reproduced throughout the 1990s and 2000s. (Cento Bull & Gilbert, Citation2001, p. 14). These drew on MRA cultural repertoires and reflect how the Northern Question was embedded in a well-defined frame: that of the dispute of the labouring North against an inefficient, inefficacious and ineffective (good-for-nothing) political centre’ (Biorcio & Vitale, Citation2011, p. 175). Further to this, a poster released by the Lega following its declaration of Padania, draws heavily on the cultural repertoire of a ‘Free Padanian’ heartland used and (). demonstrates a logical progression from the MAB to the UAI to the Lega Nord and an evolution of terms.

A key development, in both the aforementioned cultural repertoires however, lies in the overall message of the posters, which changed due to the differing historical contexts. The imagery of the wolf has been substituted with a stereotypical image of a ‘southern Mafioso’ to represent Rome whilst also employing Roman dialect to emphasise the juxtaposition between North and South. The Lega opted to associate Roman power with the Mafia, taking advantage of the increased publicity surrounding organized crime and its association with the south of the peninsula, which it argued had infiltrated the state. The Lega’s notion of Padania was also more radical than either the MRAs’ ‘MARPadania’ or the UAI’s ‘Free Padania’, with Bossi proposing a separate North Italian state.

Finally, in terms of the ‘Battle of Legnano’, Bossi’s claims in his autobiography that the symbol of Alberto da Giussano ‘was my invention’ (Bossi, Citation1992, p. 75) can be challenged by viewing it instead as a reproduction of the discursive repertoire developed by the MAB in 1959. However, the use of this symbol is much more central to the Lega’s identity, providing party activists with an image to rally around. The Battle of Legnano’s historic link to Pontida, previously highlighted by the MAB in La Regione Lombarda and then developed further by the UAI’s repertoire of gatherings and oaths in the 1960s and 1970s, was also re-emphasised by the Lega through its annual party rally of the “Festa di Pontida” (). This gathering in itself has acted as a key platform for the reproduction and reinforcement of cultural repertoires with roots in 1950s populist regionalism.

4. Conclusion

To better understand the latent nature of populism, this article has strengthened the bridge between political studies and social movement research. I have used a conceptual framework rooted in abeyance theory to explain how populist discourse survives a period of inactivity through its maintenance via abeyance structures and subsequent transmission via inter-generational links. By viewing populist discourse as an expression of ‘contentious politics’, this article has emphasised the importance of understanding repertoires of contention not only in terms of action, but also in its cultural variant.

The case study of North Italian populist regionalism has reinforced the importance of contextual factors in the success of contentious politics and political challengers, but also noted the importance of agency. Following repertoire creation in the 1950s by the MRAs, the abeyance structures in the 1960s and 1970s, allowed for the maintenance of populist regionalist repertoires. Following the transmission of these repertoires in the 1980s, in terms of structure, the crisis of the Italian party system caused by the twin factors of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Tangentopoli scandals saw a breakthrough of the Lega’s demands as it marked the end of a party or coalition being able to achieve overall control and shut out regionalist demands. Regarding agency, Umberto Bossi’s leadership and his ability to unite the various regionalist leagues into the Lega Nord represented the real point of departure for this wave of populist regionalism.

The article raises two important conceptual points. First, the contextual differences between waves of activism underlines the importance of avoiding an over-emphasis on continuity and to notice that activists in a second wave of activism cannot rely completely on the content of past repertoires. Second, while this case study has involved the study of past movements, this does not mean that the framework is only retrospective. Instead, the concepts examined can be used as a predictive paradigm allowing for the analysis of how current waves of activism may act as a source of future actvism.

Potential future applications of this framework involve both the logical progression of and expansion beyond the North Italian case. Applying it to Matteo Salvini’s latest wave of Lega activism could examine the absorption of the traditional regionalist elements of the party. Debates within the Lega in 2018 over referendums in Lombardy and the Veneto for greater autonomy from Rome and opposition to Matteo Salvini’s change of the party’s official name to ‘Lega per Salvini’ may represent abeyance structures which promote both continuities and discontinuities with past activism (Giovannini & Vampa, Citation2019). The activities, of more intransigent populist regionalist activists in the Lega and their links with pre-Salvini activism, therefore deserve greater examination.

Future researchers may apply the framework developed in this article to trace continuities and discontinuities in populist discourse and between specific populist movements at both a national and transnational level. Beyond populism, the framework may also be used to examine a wide range of ideologies, parties and social movements. The re-emergence of political narratives of both the far left and far right, continuing debates over European Union membership and integration, and militant climate crisis activism are all phenomena which have both deep roots in a variety of social and historical repertoires and are likely to act as reference points for future waves of activism. Linked into these phenomena are the seeming collapse of a social-democratic consensus in Europe since the financial crisis of 2008 and the ensuing economic, social and political deficit in many societies which, since the outbreak of Coronavirus, have been exacerbated, threatening new waves of contention. Abeyance can be used to illustrate how such instances of contention are not independent events but instead form part of longer-term patterns of social and political interaction thus paving the way for greater collaboration between sociology and political studies.

Funder details

No funding has been received for this paper.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgements

This article was first presented at a Politics Research Seminar at the University of Bath on 28 April 2020. I would like to thank the seminar convenor Jack Copley and my colleagues at this seminar for their helpful comments and feedback. Big thanks also go to Dr Aurelien Mondon, Professor Anna Cento Bull and the anonymous reviewers of this paper for their invaluable comments on earlier drafts.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

George Newth

George Newth holds a PhD in Politics, Languages and International Studies from University of Bath where he is Lecturer in Italian Politics. His research focuses on the links between regionalism, nationalism and populism with a particular interest in the history of the Lega Nord.

Notes

1. Primary sources at the following locations:Archivio di Stato di Torino Fasc.Movimento per l’Autonomia Regionale Piemontese, vol.1, Cat.A3A,; Istituto Bergamasco per la Storia della Resistenza e dell’età contemporanea (ISREC); Biblioteca Angelo Mai, Bergamo; Biblioteca Nazionale di Roma

References

- Albertazzi, A., Giovannini, A., & Seddone, A. (2018). “No regionalism please, we are Leghisti!” The transformation of the Italian Lega Nord under the leadership of Matteo Salvini. Regional and Federal Studies, 28(5), 645–671. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1512977

- Alimi, E. Y. (2015). Repertoires of Contention. In D. Della Porta & M. Diani (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of social movements (pp. 410–422). Oxford University Press.

- Aslanidis, P. (2015). Is populism an Ideology? A refutation and a new perspective. Political Studies, 65, (1), 88–104. h ttps://d oi.org.ezproxy1.bath.ac.uk/ 1 0.1111/1467.9248.12224

- Aslanidis, P. (2017) Populism and social movements. In C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P.A. Taggart, P.Ochoa Espejo, P.Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 305–325). Oxford University Press.

- Bagguley, P. (2002). Contemporary British Feminism: A social movement in abeyance? Social Movement Studies, 1(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1474283022000010664

- Beaumont, C., Clancy, M., Ryan, L., (2020). Networks as “laboratories of experience”: Exploring the life cycle of the suffrage movement and its aftermath in Ireland 1870–1937. Womens History Review, 29(6), 1–21. h ttps:// doi.org.ezproxy1.bath.ac.uk/ 1 0.1080/09612025.2020.1745414

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing Processes and Social Movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Bergamo Communal Archive. (1960). Dati statistici ufficiali relativi alle votazioni nel comune di Bergamo. Elezioni Proviniciali 1960. Archivio Storico Comune di Bergamo, Cat. 6(Governo). Classe a. Fasc. 1 e 2. Anni 1954-1964.

- Bergamo Election Results. (1990). Elezioni Amministrative del 6/7 Maggio 1990. Comune di Bergamo. Retrieved June 10, 2018, from http://www.comune.bergamo.it/upload/bergamo_ecm8/gestionedocumentale/AMMINISTRATORIDIBGDAL1946AL2014_784_25292.pdf

- Biorcio, R., & Vitale, T. (2011). Culture, values and social basis of Northern Italian centrifugal regionalism: A contextual political analysis of the Lega Nord. In M.Huysseune (Ed.) Contemporary centrifugal regionalism: Comparing flanders and Northern Italy (pp. 171–199). Royal Flemish Academy of Belgium for the Science and the Arts Press

- Borsotti. (1987). 35 anni di Lotta. Piemont Autonomista, April.

- Bossi, U. (1982). Lombardia Autonomista. Oct-Nov.

- Bossi, U. (1992). Vento dal Nord: La mia Lega, la mia vita. Sperling and Kupfer.

- Bossi, U. (1999). La Lega: 1979-1989. Editoriale Nord.

- Boulliaud, C, and DeMatteo, L, (2004) ‘Autonomismo e Leghismo dal 1945 ad oggi’, In A.Castagnoli (Ed.), Culture, politiche e territoriali in Italia 1945–2000 (pp. 32–45). Milan, Franco Angeli.

- Brodrero, A., & Gremmo, R. (1978). L’Oppressione culturale Italiana in Piemonte. Editrice BS.

- Brubaker, R. (2020), ‘Populism and Nationalism’ Nations and Nationalism, 26(1), 44–66.

- Cachafeiro, M. (2001). Ethnicity and nationalism in Italian politics: Inventing the Padania: Lega Nord and the northern question. Ashgate.

- Calderoli, G. (1958). Zibaldone Autonomista di un montanaro Bergamasco. Gruppo Autonomisti Bergamaschi.

- Canovan, M. (1982). Two strategies for the study of populism. Political Studies, 30(4), 544–552. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1982.tb00559.x

- Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 2(16), 2–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Canovan, M. (2004). Populism for political theorists. Journal of Political Ideologies, 9(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1356931042000263500

- Caruso, L. (2015). Theories of the political proces, political opportunities structure and local moblizations. The case of Italy. Sociologica, 9(3). 1–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2383/82471

- Cento Bull, A. (2015). The fluctuating fortunes of the Lega Nord. In A. Mammone, E. Giap Parini, & G. A. Veltri (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of contemporary Italy, history, politics and society (pp. 204–214). Routledge.

- Cento Bull, A., & Gilbert, M. (2001). The Lega Nord and the northern question in Italian politics. Basingstoke.

- De Cleen, B., Glynos, J., & Mondon, A. (2018). Critical research on populism: Nine rules of engagement. Organization, 1(13), 649–661. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508418768053

- Diamanti, I., & Lazar, M. (2018). Popolocrazia: La Metamorfosi delle nostre democrazie. Laterza.

- Diani, M. (1996). Linking moblisation frames and political opportunities: Insights from regional populism in Italy. American Sociological Review, 61(6), 1053–1069. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2096308

- Fillieule, O. (2006). Requiem pour un concept. Vie et mort de la notion de ‘structure des opportunités politiques. In G. Dorronsoro (Ed.), La Turquie conteste (pp. 201–218). Presses du CNRS.

- Freddi, A. (1963). Breve Storia del MAB. Movimento Autonomista Bergamaschi.

- Gade, T, (2018), 'Together all the Way? Abeyance and co-optation of Sunni networks in Lebanon', Social Movement Studies, 18(1), 56–77.

- Gade, T. (2019). Together all the way? Abeyance and cooptation of Sunni networks in Lebanon. Social Movement Studies, 18(1), 56–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1545638

- Giovannini, A., & Vampa, D. (2019). Towards a new era of regionalism in Italy? A comparative perspective on autonomy referendums. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1582902

- Glynos, J., & Mondon, A. (2016). The political logic of populist hype: The case of right-wing populism’s “meteoric rise” and its relation to the status quo”. Populismus Working Papers No.4. p.2.

- Gremmo, R. (1992). Contro Roma. Storia, idee e programmi delle leghe autonomiste del Nord. Stem Editoriale Spa.

- Gremmo, R. (2016). Interview with author, 8th February

- Grimm, J., & Harders, C. (2018). Unpacking the effects of reperession: The evolution of Islamist repertoires of contention in Egypt after the fall of president Morsi. Social Movement Studies, 17(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2017.1344547

- Heinisch, R., Masetti, E., & Mazzoleni, O. (2020). Introduction: European party-based populism and territory. In Idem (Ed.), The people and the nation: Populism and territorial politics in Europe (pp. 1–19). Routledge.

- Hine, D. (1996). Federalism, regionalism and the Unitary State. In C. Levy (Ed.), Italian regionalism: History, identity, politics (pp. 109–131). Berg.

- Katsambekis, G. (2017). The populist surge in post-democratic times: Theoretical and political challenges. The Political Quarterly, 88(2), 202–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12317

- King, L. (2007). Charting a discursive field: Environmentalists for U.S. populiation stablization. Sociological Inquiry, 77(3), 301–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.2007.00195.x

- L’Eco di Bergamo. (1960). Così schierati i partiti per le elezioni 13th October.

- L’Eco di Bergamo. (1968). Newspaper article clipping entitled “La Nuova Lega Lombarda”. in Fasc.MAB-Autonomisti, Archivio Aldo Rizzi, Biblioteca Angelo Mai, 15th January.

- La Stampa. (1958). Il MARP diventa Padano per presentarsi alle elezioni. 24th February.

- La Stampa. (1964). Il MARP bis non intende modificare il simbolo. 29th October.

- La Stampa. (1989). Gipo Farassino fonda la Lega Nord. Va con Gremmo il fondatore del MARP. 27th November.

- La Stampa. (1994). Il MARP degli anni 50 Padre della Lega. 12th April.

- Mahoney, J. (2000). Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory and Society, 29(4), 507–548. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007113830879

- Melucci, A. (1989). Nomads of the present: Social movements and individual needs in contempoarary society. Radius.

- Meyer, D. S., & Sawyers, T. M. (1999). Missed opportunities: Social movement abeyance and public policy. Social Problems, 46(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3097252

- Mizruchi, E. (1983). Regulating society: Marginality and social control in historical perspective. Free Press.

- Moffit, B., & Tormey, S. (2013). Rethinking populism: Politics, mediatisation and political style. Political Studies, 62(2), 381–397. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12032

- Newth, G. (2018). Fathers of the Lega Nord [PhD Thesis]. University of Bath.

- Newth, G. (2019). The roots of the Lega Nord’s populist regionalism. Patterns of Prejudice, 53(4), 384–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2019.1615784

- Paini, A. (ed.). (1949). L’istituto Regionale e la nostra riforma. Tipografia Orfanotrofio Maschile.

- Passalacqua, G. (2009). Il Vento della Padania: Storia della Lega Nord 1984-2009. Mondadori.

- Piemont Autonomista. (1987). Elezioni politiche ’87 – I nostri candidati. Piemont Autonomista. 18th May.

- Piemonte Nuovo. (1956). Perchѐ ho scelto la lista del MARP 23rd March.

- Piemonte Nuovo. (1956a). M. Rosboch. L’autonomia regionale amministrativa non potrà dividere il popolo Italiano. 23rd March

- Piemonte Nuovo. (1958a). Vei Piemunt! Gli Autonomisti Italiani vedono nel MARP l’algiere dell’autonomia regionale – Il congresso di Verona ha messo in luce che l’idea autonomista ѐ oggi diventata la forza motrice del popolo italiano. 1st February.

- Press, R.M, (2015). Ripples of Hope, How Ordinary People Resist Repression Without Violence, Amsterdam University Press.

- Reynolds, J., & Wetherell, M. (2003). The discursive climate of singleness: The consequences for women’s negotiation of a single identity. Feminism & Psychology, 13(4), 489–510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/09593535030134014

- Roberts, K. M. (2015). Populism, social movements and popular subjectivity. In D. Della Porta & M. Diani (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of social movements (pp. 681–695). Oxford University Press.

- Sala, G. (2016). Interview with author. 20th March.

- Sassoon, D. (1995). Tangentopoli or the democratization of corruption: Considerations on the end of Italy’s First Republic. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 1(1), 124–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13545719508454910

- Sewell, W. H. (2005). The Concepts of Culture. In G. M. Spiegel (Ed.), Practicing history: New directions in historical writing after the linguistic turn (pp. 76–95). Routledge.

- Stavrakakis, Y., & De Cleen, B. (2017). Distinctions and articulations: A discourse theoretical framework for the study of populism and nationalism. Javnost- The Public, 24(4), 301–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2017.1330083

- Stavrakakis, Y., & De Cleen, B. (2020). How should we analyze the connections between populism and nationalism: A response to Rogers Brubaker, Nations and nationalism 26(2), 314–322. Stavrakakis

- Steinberg, M. W. (1995). The roar of the crowds: Repertoires of discourse and collective action among the spitalfields silk weavers in nineteenth-century London. In M. Traugott (Ed.), Repertoires and Cycles of Collective Action(pp. 57–87). Due University Press.

- Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies. American Sociological Review, 51(2), 273–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2095521

- Taggart, P. (2000). Populism. Buckingham.

- Taggart, P, (2017) ‘New Populist Parties in Western Europe’. In C.Mudde (Ed.), The populist radical right:A reader (pp. 225–241). Routledge.

- .Tarrow, S. (1993). Cycles of collective action: Between momemnts of madness and the repertoire of contention. Social Science History, 17(2), 281–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0145553200016850

- Tarrow, S., & Tilly, C. (2007). Contentious politics and social movements. In C. Boix & S. C. Syokes (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative politics(pp. 435–460). Oxford University Press.

- Tarrow, S. (2011). Power in movement: Social movement and contentious politics (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, V. (1989). Social movement continuity: The women’s movement in abeyance. American Sociological Review, 54(5), 761–775. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2117752

- Taylor, V.(1997) ‘Social Movement Continuity: The Women’s Movement in Abeyance’, In D. McAdam and D. A. Snow (Eds), Social Movements:Readings on their Emergence, Mobilization and Dynamics, Roxbury (pp. 409–20).

- Tilly, C. (1978). From mobilization to revolution. Addison Wesley.

- Tilly, C. (2008). Contentious Performances. Cambridge University Press.

- Turin National Archives. (1962b). Notes by the Turin police commissioner entitled “MARP-Confluenza nel PSDI”. In Fasc. Movimento per l’Autonomia Regionale Piemontese, vol.1. Archivio di Stato Torino, Cat A3A, 18th December.

- Turn National Archives. (1962a). Notes by the Turin police commissioner entitled “Passaggio del MARP al PSDI”. In Fasc. Movimento per l’Autonomia Regionale Piemontese, vol.1, Archivio di Stato Torino, Cat.A3A, 15th November.

- UAI. (1970). Electoral poster.

- Veugelers, J. W. P. (2011). Dissenting families and social movement abeyance: The transmission of neo-fascist frames in post-war Italy. The British Journal of Sociology, 62(2), 241–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2011.01363.x

- Vitale, T. (2015). Territorial conflicts and new forms of left-wing political organization: From political opportunity structure to structural contexts of opportunities. Sociologica, 9(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2383/82475