ABSTRACT

In this article we explore the extent of the digital connectivity and character of the mediated solidarity discernible between a selection of militant antifascist groups in the USA and UK on Twitter. By studying the geographical scalarity of the retweet practices of six case study groups in these two countries (from New York City, Philadelphia, Portland, Brighton, Liverpool, and London) and the content of a sub-sample of these groups’ retweets we highlight that their Twitter connectivity is relatively limited. We also suggest that the sorts of mediated solidarity, or as we specifically refer to it here ‘retweet solidarity’, that this connectivity reflects is rather shallow. As such the article’s broader contributions relate to firstly the need for studies of digital connectivity within social movements that do not preemptively assume that translocal or transnational activism is an automatic by-product of social media use, and secondly the necessity to continue problematizing the idea of solidarity in digital contexts.

Introduction

Even if mostly associated with the febrile domestic politics of the USA, and unknown to most Americans until after Donald Trump’s 2016 election, the militant antifascist movement, or ‘Antifa’, is a global phenomenon with lengthy historical provenance (Braskén et al., Citation2020). Decentralized and non-hierarchical, this radical social movement is loosely structured on dispersed networks of local groups whose scale of action is largely, though not exclusively, determined by local and/or national contexts. This is not to say that Antifa activists and groups do not operate across national borders. For the most part, this involves joining demonstrations in neighboring countries particularly where geographical proximity lowers the physical barriers to such forms of mobilization.Footnote1 However, for activists who are more geographically distant and located on opposite sides of the Atlantic, the physical barrier of thousands of nautical miles remains an obvious inhibiting factor.

If the transatlantic flow of Antifa activists – transatlantic, here referring to exchange between the USA and UK – is more of a trickle than a deluge, then the uptake of social media platforms, in compressing geographical distances (and time), might compensate for, and offset, some of the physical barriers to their connectivity. In fact, it is now often taken for granted that these platforms promote transnational social movement activism. Given that Antifa activists in the USA are partly inspired by those in the UK (Bray, Citation2017) and share a common language, we might then expect to uncover evidence of ‘new transnational activism’ (Tarrow, Citation2005) taking place between Antifa groups from these countries on social media. At the same time, the pervasiveness of social media has led to what Cammaerts has called ‘new-new social movements’ – movements partly characterised by ‘a digital context more prone to foster weak rather than strong ties’ (Cammeaerts, Citation2021, p. 350).

Focusing on solidarity as one invocation of connectivity (Cammeaerts, Citation2021), in this article we start from the premise that social media might have facilitated new modalities of transatlantic connection between Antifa groups in the USA and UK. In doing so we respond to Antifa’s claims that their project is global, as well as those of their right-wing detractors who demonize them as part of a world-wide conspiracy. Ultimately, we ask: What is the extent of the digital connectivity between USA and UK Antifa groups on Twitter, and what is the character of the mediated solidarity conveyed by this connectivity?

To answer these questions, we place militant antifascism within the social movement field. We then review the literature on digital antifascism before discussing mediated solidarity. Thereafter we present six Antifa groups from the USA and UK as cases and outline our data collection and analysis methods. Two analysis sections then follow: one concerned with the extent of the digital connectivity between the groups on Twitter and one that addresses the character of the ‘retweet solidarity’ conveyed by this connectivity. We conclude by summarizing our findings and highlighting potential avenues for future research.

Locating militant antifascism in the social movement field

The study of militant antifascism is most developed within historical scholarship where the neologism ‘antifascist studies’ has recently emerged. Nonetheless, the subject of antifascism finds itself dwarfed by the volume of historical literature devoted to fascism and is still largely approached from the perspective of the interwar period when antifascism was ‘corrupted’ through its historical association with Communism, and Stalinism in particular (Furet, Citation2004). Within ‘antifascist studies’ there is a greater emphasis on antifascism’s plurality of form, captured in the phrase ‘varieties of antifascism’ (Copsey & Olechnowicz, Citation2010). An appreciation of antifascism’s polymorphic complexity thus now sits alongside growing recognition of how the global menace of fascism in the 1930s not only gave rise to transnational protest, but also occasioned intersections between antifascism, anticolonialism, and antiracism (Braskén et al., Citation2020). Historians of antifascism have also made clear that transnational antifascist activism continued after 1945, even if efforts in the 1990s to establish a militant antifascist ‘International’ ultimately proved abortive (Copsey, Citation2016).

Within social movement studies, the study of antifascist activism is yet to gather anything resembling a similar pace. Tellingly, the index to the Oxford Handbook of Social Movements does not include any reference to ‘antifascism’ or to ‘antifascism’ movements (Della Porta & Diani, Citation2015).Footnote2 By way of comparison, it draws five references to ‘antiracism’ movements. However, even then, as Egger and Giugni point out, ‘research on anti-racist and pro-migrant movements is extremely limited’ (Eggert & Giugni, Citation2015, p. 167). Social movement research on antifascist movements is even more limited.

To its credit, the most detailed work that has been carried out on Antifa in the USA so far opines that the ‘structure, actions, and culture of militant antifascism are best understood in an analytical framework which recognizes that it is a radical social movement’ (Vysotsky, Citation2021, p. 11). According to Vysotsky (Citation2021, p. 10), part of the reason for Antifa’s comparative neglect amongst social movement theorists is that it ‘operates outside of the bounds of normative social movement processes’. In other words, since Antifa is not reform-oriented, and on account of the movement-countermovement interaction - (violent) contest between far-right forces and antifascists – it falls outside ‘existing models developed in the social movements canon’ (Vysotsky, Citation2021, p. 11). Furthermore, alternative theoretical models that have emerged in response to radical social movement organizations (RSMOs) do not entirely fit Anifa either. Admittedly, many of the defining characteristics of Fitzgerald and Rodgers’ RSMO ideal type (Fitzgerald & Rodgers, Citation2000) can apply to Antifa: non-hierarchical leadership; radical agendas, ideologies, and networks; global consciousness; ignored or misrepresented by the media; egalitarianism; subject to opposition and government surveillance etc. However, while Fitzgerald and Rodgers further identify direct action as a characteristic of RSMOs, their qualification of this as ‘non-violent’ precludes Antifa, whose direct action often takes violent form.

Even as we are being encouraged to understand Antifa as a RSMO, there is silence when it comes to transnational coalition-building and campaigning. This is, so it seems, marginal to the Antifa experience in the USA – local Antifa groups do not come across in Vysotsky’s account as giving any precedence to transnational activism. While all street activism or political protest in public space in some respects remains inescapably local, antifascist activism in particular does, because its primary purpose is to respond to locally manifested far-right threats (Merrill & Pries, Citation2019). Thus, it is useful to think about the global phenomenon of Antifa in translocal terms. Translocality ‘does not merely indicate a new geographical scale between the local and the global but stresses the fluidity and relationality of these scales’ (Merrill & Pries, Citation2019, p. 251). Neither is it anchored to a static framework of distinguishable geographic scales in the way transnationalism is (Greiner & Sakdapolrak, Citation2013). It provides an umbrella term that encompasses transnationality (including transatlantic transnationality) in referring to ‘multiple forms of spatial connectedness’ and ‘multidirectional and overlapping networks that facilitate the circulation of people, resources, practices, and ideas’ (Greiner & Sakdapolrak, Citation2013, p.375).

Digital antifascism and retweet solidarity

Although the analysis of militant antifascism remains underdeveloped within social movement studies, it is gaining increasing attention from digital activism scholars. These scholars’ research generally confirms Gerbaudo’s distinction between two phases of left-wing digital activism corresponding to shifts between web 1.0 and web 2.0 technology, protest waves and ideologies (Gerbaudo, Citation2017). The first phase relates to the anti-globalization movements of the 1990s and 2000s that were underpinned by anarchist and autonomist ideologies. These sought to establish autonomous digital communication infrastructures, free from state and market control (Gerbaudo, Citation2017). The second phase relates to the so-called ‘movements of the squares’ that emerged in the 2010s and were supported by a populist, citizen-focused ideology that sought radical democracy and authentic forms of political participation free from liberal-democratic institutions. These harnessed rather than shunned corporate social media like Facebook and Twitter (Gerbaudo, Citation2017).

For Antifa groups, however, using corporate social media has not been unproblematic. Greek and Swedish Antifa groups have been hesitant to fully embrace them because of the risks of media censorship, state surveillance and far-right retribution that they can pose (Andersson, Citation2016; Highfield & Croeser, Citation2015). Research has also shown that the use of social media platforms by German antifascist activists can depend on their individual commitment and the character of the platforms themselves (Merrill & Lindgren, Citation2020; Neumayer et al., Citation2016). Ultimately, however, Antifa activists rarely completely shun corporate social media (Kaun & Treré, Citation2020).

Antifa groups will use, and prioritize, social media for some tasks while turning to more secure, sometimes independent digital communication infrastructures for others (Highfield & Croeser, Citation2015; Merrill & Lindgren, Citation2020). Even so, activists will weigh the benefits of the visibility that social media offer over the risks to their security differently (Neumayer et al., Citation2016). Still, the general failure of the first phase of left-wing digital activism coupled with the recent rise of the far right off- and online, has led increasing numbers of Antifa groups and activists to use corporate social media (Koch, Citation2018). The point to make here is that they have done this partly to attract solidarity and mobilize broader sections of the public.

The widespread adoption of these platforms by Antifa’s adversaries has in turn created new ‘political communication battlespaces’ necessitating different forms of antifascist engagement (Mirrlees, Citation2019, p. 28). These include reporting hateful far-right digital content to moderators so to have it and its creators removed from platforms; doxing or ID-ing (revealing the identity of far-right activists online); ideological critique (using social media to produce and spread content that criticizes far-right ideology); and so-called ‘meme wars’ (the creation and circulation of digital cultural content designed to humiliate far-right actors) (Mirrlees, Citation2019).

Prefiguring calls for a balanced analysis of left- and right-wing digital activism (see Freelon et al., Citation2020), Klein (Citation2019) compared the rhetoric of American Antifa and Alt-right groups’ Twitter posts and found that the former called for non-violent opposition and defense more often than the latter and less often resorted to forms of mockery and appeals to force (Klein, Citation2019). Copsey and Merrill (Citation2020) also found that Antifa groups exercise rhetorical restraint on Twitter. Xu meanwhile found that on Twitter both Antifa and the alt-right use identity-affirming hashtags but for Antifa these hashtags convey a more decentralized, activist-oriented identity that is strengthened by displays of solidarity relating to local street activis (Xu, Citation2020). While the alt-right relies on trolling, Antifa uses connective action - ‘digitally enabled, networked, personalized, and decentralized actions of mobilization’ - to support street activism and digital direct action (see Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012; Xu, Citation2020, p. 1071).

Merrill and Pries have also shown how Swedish Antifa activists have used Facebook and Twitter to reach beyond their radical milieus and mobilize thousands of people to join street demonstrations against neo-Nazi violence (Merrill & Pries, Citation2019). In this case a protest hashtag helped Antifa groups to frame the demonstrations in a way that generated transnational and translocal solidarity even if loss of control over this frame eventually forced them to ‘relocalize’ their efforts via a second hashtag.

Collectively these studies indicate that Antifa groups use Twitter partly to connect with one another and to build networks of solidarity. Twitter, in other words, provides an opportunity to ‘mediate solidarity’ (Fenton, Citation2008). Fenton defines solidarity as ‘a morality of cooperation, the ability of individuals to identify with each other in a spirit of mutuality and reciprocity without individual advantage or compulsion, leading to a network of individuals or secondary institutions that are bound to a political project involving the creation of social and political bonds’ (Fenton, Citation2008, p. 49). While acknowledging that solidarity exceeds mediation, she discusses how digitally mediated solidarity can embrace a multitude of geographically distributed individuals and groups (Fenton, Citation2008). Initially, digitally mediated solidarity was regularly derided as a lazy form of protest – as ‘slacktivism’ or ‘clicktivism’ - but more recently it has been reappraised as a legitimate political act (Fenton, Citation2008; Halupka, Citation2014).

The solidarity mediated by social media is further complicated because social media companies are motivated by the generation of financial returns rather than connecting activists. Croeser suggests the solidarity expressed through social media is incidental – it is squeezed through corporate social media logics to meet business models and please users and advertisers (Croeser, Citation2018). Still, corporate like independent social media platforms can mediate solidarity by serving as vehicles of expressions of support across wide geographic distances; forming and reinforcing emotional and identity bonds; facilitating crowdfunding efforts; mobilizing activist lobbying; and spreading ideas (Croeser, Citation2018). Croeser also distinguishes between traditional and transformative forms of mediated solidarity. The former, akin to Fenton’s broader definition, is linked to empathetic, emotional, and imaginative connections of support. The latter ‘more radically transforms those engaged in solidarity effort’ – it questions the one-directional character of solidarity and re-envisions it not in terms of short-term support but longer-term engagement (Croeser, Citation2018, p. 32). However, in Croeser’s own study of the mediated solidarity displayed towards the Kurdish autonomous movement on Facebook and Libcom she found little evidence that either corporate or independent social media platforms supported transformative solidarity (Croeser, Citation2018).

Building on Croeser’s work, we further problematize assumptions about what constitutes solidarity online, within the context of social movements in general, and Antifa groups specifically. We do this by conceiving of a spectrum of ‘deep’ and ‘shallow’ forms of mediated solidarity with more traditional forms at one end and more transformative forms at the other. This resonates with other gradated conceptualizations of digital activism that take seriously these phenomena’s micro-expressions. Dennis, for example, conceives of a continuum of digital activism that stresses the political authenticity and legitimacy of social media ‘likes’ and ‘shares’ (Dennis, Citation2019). Similarly, George and Leidner discuss a hierarchy of digital activism with sharing, endorsement, and content creation activities at the base; boycotting, fundraising, petition and bot-based activities in the centre; and data activism, exposure (including ‘doxing’) and hacking activities at the apex (Dennis, Citation2019).

More precisely, we explore the gradated mediated solidarity evidenced in the origin and content of the tweets that USA and UK Antifa groups retweet as ‘retweet solidarity’. This term is intended to diversify rather than dilute the broader concept of (mediated) solidarity by recognizing that retweets in digital activist settings not only often contain explicit expressions of solidarity but also that the act of retweeting can itself be considered solidaristic (Mercea & Levy, Citation2019). In this sense ‘retweet solidarity’, relates to the amplifying and sharing function of retweeting that George and Leidner call ‘metavoicing’ (George & Leidner, Citation2019). While we do not wish to inhibit a multifarious conception of retweets in social movement contexts (as also, for example, a form of social validation, knowledge sharing or brokerage) and, while we accept that there are diverse individual-level motivations for retweeting that vary at different times (boyd et al., Citation2010; Mercea & Levy, Citation2019), for the purposes of this article we conceive retweets primarily as expressions and acts of mediated solidarity. We do this partly because mediated solidarity in the more gradated and expansive sense that we conceive it promises to accommodate these alternative conceptualisations to some extent. While among some types of Twitter users the disclaimer ‘retweets ≠ endorsements’ is common, research suggests Antifa activists’ acute awareness of Twitter’s recommendation algorithms and surrounding attention economy means they usually reserve retweeting for that content that they support and are intentionally trying to boost, with the corollary that they will usually avoid retweeting their adversaries so not to contribute to the spread of oppositional content (Copsey & Merrill, Citation2020, Citation2021).

Material and methods

In this article we focus on the transatlantic retweet connections between USA and UK Antifa groups. While such connections exist between Antifa groups beyond these countries, we chose to study Antifa groups from the USA and UK because their common language and historical linkages were expected to contribute to more prominent, and therefore more observable, degrees of mutual, contemporary connection and in turn mediated solidarity.

Translocal connections existed between antifascists in the USA and UK before social media platforms. These usually relied on ‘relational diffusion’ based on pre-existing personal ties or when unconnected actors became linked through ‘brokerage’ (see Tarow & McAdam, Citation2005). In the interwar period, members of the radical Italian diaspora in New York had contacts with their counterparts in London, sending funds and, in one case, an anarchist across the Atlantic, as part of an abortive effort to assassinate Mussolini (Copsey & Merrill, Citation2021). During the 1930s, in response to the Nazi seizure of power, solidarity networks between USA and UK antifascists were quickly established through Communist-led movement ‘brokers’ (Braskén, Citation2020).

In the late 1990s, in response to the rise of the far right in Europe along with concerns over the increasing isolation of nation-based militant antifascist groups, there was an ambitious launch of a new ‘International Militant Anti-Fascist Network’. Activists from the USA attended the network’s first conference in London in 1997, with one American group affiliating to it when it was formally launched in April 1998. However, beyond issuing a joint manifesto and establishing a static website, the transnational cooperation and communication was modest. In fact, the network soon folded when one of its chief architects, the UK’s Anti-Fascist Action, fragmented (Copsey, Citation2016).

Relational ties between antifascists in the USA and UK have also been maintained more recently: in mid-2018, for instance, members of the London Antifascists visited Rose City Antifa in Portland; they were also interviewed for a podcast on It’s Going Down, a digital hub for North American anarchist, antifascist, autonomous anticapitalist, and anticolonial groups. Relational contacts can be often informal and personal: several of Rose City Antifa’s members having lived in the UK, for example (Copsey & Merrill, Citation2021). Nonetheless, such relational diffusion remains minimal thus justifying the closer interrogation of these groups’ digital connection.

In this article we focus on Antifa groups from six different cities – three from the USA (New York City, Philadelphia, and Portland) and three from the UK (Brighton, Liverpool, and London). These groups were selected because they are relatively high profile, engage in both street and digital activism, and because of their use of social media platforms. The groups are New York City Antifa (NYCA); Philly Antifa (PA); Rose City Antifa (RCA); Brighton Antifascists (BA); London Antifascists (LA); and the Liverpool-based Merseyside Anti-Fascist Network (MAFN).Footnote3 These groups have, at various times, used a combination of blogs, Twitter and/or Facebook as their primary public-facing social media platforms (). Interviews conducted with group members as part of a wider study (see Copsey & Merrill, Citation2020, Citation2021), like other research (see Merrill & Pries, Citation2019), highlighted how the group’s anonymised accounts on these platforms were often run by more than one individual and that while individual group members might have their own personal accounts they would not disclose their group membership on these for security reasons, not least to avoid being targeted by far-right activists or surveilled by law enforcement agencies. Besides indicating how group accounts provide individuals protective anonymity, the interviews – which in this article serve contextualisation purposes rather than as a main data source – also highlighted that individual members often differentiated their views from their group’s and as such were careful that any posts to social media platforms made on behalf of the group reflected group consensus.

Table 1. The case groups’ digital presence (as of 18 October 2021).Footnote4.

Twitter was selected for further analysis because each group was active on the platform at the time of research and because studies suggest that Antifa groups have been more tolerated by the platform and find it more palatable than other corporate platforms (see Merrill & Lindgren, Citation2020).Footnote5

Twitter also provided practical advantages because its regulations more easily allow for the collection of user-generated-content for research purposes. The tweets were collected from each group’s Twitter account according to these regulations on 28 August 2020. At this time the collection of up to 3200 of the most recent tweets posted by an account was permitted. provides more information about the Twitter sample. The ‘date range’ and ‘tweets’ columns convey the groups’ different levels of commitment to maintaining a Twitter presence. As suggested by others (see Mirrlees, Citation2019), these groups use Twitter partly to avoid ceding the platform to their adversaries. This connects to the groups’ perceived imperative to remain vigilant and ‘on-guard’, even if the extent to, and manner by, which they do this differs. NYCA, RCA and MAFN stand out in their higher use of Twitter. While it is important to consider how much of this activity is automatic or apathetic and geared towards only maintaining a digital presence, the interviews, the Twitter data, and some of the analysis carried out below implies that these groups for the most part use Twitter in an intentional and considered, if somewhat sporadic, manner.

Table 2. The Twitter sample (collected 28 August 2020).

While we have explored the discourses and rhetoric of the collected tweets in more qualitative detail elsewhere so to better understand the groups and their modes of social media communication (see Copsey & Merrill, Citation2020, Citation2021), in this article we focus specifically on retweets as more easily quantifiable digital points of connection between the groups. As mentioned, we do so through reference to ‘retweet solidarity’, generally – although not exclusively – approaching retweets as indicating forms of solidarity in content and practice (see Mercea & Levy, Citation2019). While the epistemological value of retweets continues to be debated (especially by critics and proponents of clicktivism), studies of the motivations behind retweeting have highlighted how – even before a dedicated retweet function was added to Twitter in 2009 - they have primarily been used to indicate affinity and agreement with or to further validate and amplify an original tweet (see boyd et al., Citation2010) in ways that support their consideration as solidaristic expressions and acts. The connotations of endorsement that retweets exemplify – in comparison to @replies or @mentions which indicate more interactive lines of connection without necessarily conveying agreement (Larsson, Citation2015) – have arguably been strengthened by Twitter’s introduction of quote tweets in 2015 which allow users to reproduce original tweets alongside their own approving or disapproving commentaries thus further freeing the use of the retweet function to be generally perceived as a sympathetic gesture.

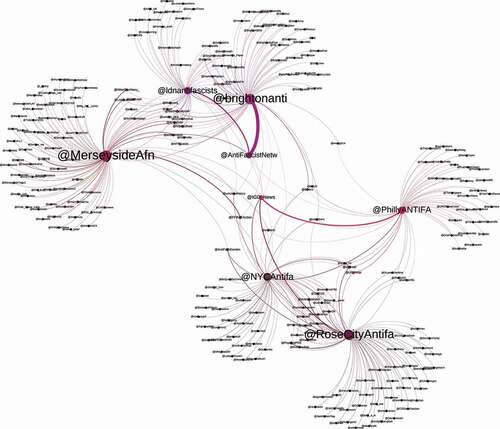

We analysed the retweets in several ways. First, the accounts that each group retweeted five or more times were manually coded according to their geographical relationship to the retweeting group. This coding relied primarily on the locations stated in each retweeted account’s profile information or on other indicators that disclosed the account’s geographic location including other profile information elements and tweet content. Three substantive codes were used: transnational, national, and local. Accounts from different national settings to the group in question or with a transnational scope were coded as transnational. Accounts from the same national setting as the group in question were coded as national whereas local was used for those originating from the same cities, federal states (USA), or counties (UK) as the group in question. If an account’s location could not be reliably determined, it was coded as unknown. Descriptive statistics were then applied to these codes to convey the geographic scalarity of each group’s retweet activity. The Gephi open-source software package was also used to visualise the retweet connections relating to the accounts that were retweeted at least five times as a social network, thereby foregrounding the direct and indirect Twitter connections between the case groups.

Second, we closely inspected a sub-sample of 329 retweets, shown in the network visualisation, that directly and indirectly connected the USA and UK groups. This allowed us to explore whether these retweets related to events in the USA and UK. It also allowed us to consider the character of the retweets and determine whether they indicated forms of ‘deep’ or ‘shallow’ mediated solidarity. Again, this analysis relied on qualitative coding procedures communicated in part via descriptive statistics. The retweets were first coded with respect to the national locations to which their content related. Where a retweet referred to multiple national locations all were coded. The retweets were then grouped according to the following headings: USA; UK; other Europe, other world, transnational/non-applicable. Then the content of each retweet was coded in terms of its thematic focus. This led to the refinement of five, sometimes co-occurring, themes: action; ideological; organising; profiling; and reporting – outlined more later in the article.

Although consent to analyse the six groups’ Twitter content was not legally required due to the platform’s user agreements, activists were informed of this during interviews carried out as part of a wider project. Ethical considerations also guided our decision to focus on anonymous group accounts rather than single user accounts because these afforded greater anonymity to individual activists. Following the prevailing ethical guidelines for the publication of Twitter content (Williams et al., Citation2017), we limited the reproduction of retweets in this article to five indicative examples involving only anonymous group accounts.Footnote6

Analysis I: the extent of digital connectivity

As below conveys, several patterns can be discerned across the groups regarding the geographic scales of their retweeting activity. Firstly, in all cases the majority of the groups’ retweets related to accounts originating beyond their own local settings but still within their national context. Secondly, in four of the six cases local retweeting outweighed transnational retweeting.

Table 3. The geographical scales of the retweets from accounts retweeted by the case groups five or more times.

While not of primary concern to this article’s transatlantic focus, the degree to which each group retweeted local and national accounts is likely influenced by the specific dynamics of street activism and differing far-right threat levels in their immediate and neighboring localities. For example, @PhillyANTIFA’s comparatively low retweeting of local accounts might reflect the prominence of other Antifa groups (and potentially struggles) in nearby large cities. Suggestive of this, @NYCAntifa was @PhillyAntifa’s second most retweeted account (81 retweets) whereas @NYCAntifa did not retweet @PhillyAntifa (see ).Footnote7 Meanwhile @PhillyAntifa’s comparatively higher percentage of retweets originating from national accounts might reflect the group’s involvement in antifascist street activism in cities of neighboring states like New York. Similar patterns can be discerned between @brightonanti and @ldnantifascists in the UK (see ).Footnote8

Table 4. The case groups’ direct retweet connections in real terms and as percentages of their total retweets.

This sort of un-reciprocal retweet activity between geographically proximate Antifa groups suggests that such groups avoid just automatically retweeting one another and that the platform does not necessarily facilitate mutual solidarity between Antifa groups that may face roughly similar far-right threat levels and even collaborate in street activism. In short, multiple factors beyond or entangled with geographic proximity influence their connection on Twitter. It might be speculated, for example, that those groups with stronger local connections (and likely shared private digital platforms) are less motivated to publicly display solidarity via retweets not least because it might be assumed.Footnote9 These observations serve as reminders not to reductively equate retweets to all forms of connectivity between the groups even if the implications of such an equation might be lessened with respect to groups that are more geographically remote from one another including, as foregrounded in this article, those in the USA and UK.

As further conveys four of the six groups retweeted transnational accounts to a similar degree (8–10% of their total retweets) - the exceptions being @RoseCityAntifa (4%) and @MerseysideAfn (23%). We might interpret @RoseCityAntifa’s lower proportional rate of transnational retweeting as being related to the group’s pronounced local struggles with far-right groups. The opposite is arguably the case for @MerseysideAfn – one of only two groups (with @PhillyAntifa) whose transnational retweets outnumbered their local ones. For @MerseysideAfn this is likely related to a lack of ongoing local struggles, freeing up the opportunity to engage in transnational solidarity.Footnote10 Leaving aside @MerseysideAfn, the extent of each of the five other account’s transnational retweeting activity indicates rather limited degrees of transnational connectivity. This is even more noticeable when considering the direct retweet connections between the six groups conveyed in . None of the USA groups retweeted the UK groups. Yet all the UK groups retweeted @NYCAntifa, albeit rather minimally, perhaps reflecting the account’s overall influence and level of activity on Twitter (see ). @MerseysidAfn additionally retweeted @RoseCityAntifa once. Besides suggesting only minimal direct transatlantic Twitter connections between the USA and UK groups, a slightly greater inclination towards transatlantic mediated solidarity from the UK groups is implied.

The six groups were also connected indirectly via the common accounts that they retweeted. The strongest of these indirect connections are conveyed below in a network visualization of the accounts that each group retweeted at least five times ().Footnote11 The weight of the connecting lines conveys the extent to which the group retweeted the adjoining account. While many different accounts connect different pairs and triplets of UK or USA groups, only ten indicate indirect transatlantic connections. These are the accounts in the middle of the network that link the USA and UK groups. All are either group or anonymous accounts. They include the accounts of the UK’s Antifascist Network (@AntifascistNetw); It’s Going Down – a North American anarchist digital news and media platform (@IGD_News); CrimethInc – a USA-based decentralized anarchist collective (@crimethinc); Enough 14 – an anarchist reporting group publishing content relating to the USA and Europe in English and occasionally German (@enough14); and the internationally orientated Working Class History project (@wrkclasshistory). They also include accounts dedicated to amplifying reports of antifascist struggles from across the world (@antifaintl, @th1an1 (now deleted)) and to sharing scholarship, publications, and news of interest to antifascist activists (@FFRAFAction) as well as anonymous individual accounts from the USA (@AntiFashGordon) and Sweden (@b9AcE). As conveys, these indirect transnational retweet connections are also rather weak and discontinuous with their one-sided weighting revealing that many of the linking accounts are most associated with either the USA or UK groups (often reflecting their origin) and are only then minimally connected to their transatlantic counterparts.

Analysis II: the character of mediated solidarity

The 329 retweets that contributed to the direct and indirect connections between the six groups (as displayed in ) indicate the sorts of mediated solidarity conveyed between the groups. , which summarizes the number and origin of these retweets, reconfirms the limited degree of the six groups’ overall retweet connections and further suggests that the UK groups invested more in these connections than the USA groups. This is additionally highlighted when the content of these retweets is considered.

Table 5. The origin and distribution of the retweets that were subjected to close reading.Footnote12.

reveals how the content of the USA groups’ retweets more often related to the USA than the content of the UK groups’ retweets did the UK. Collectively, 49 of the USA groups’ 154 retweets referred to the USA whereas only 28 of the UK groups’ 175 retweets referred to the UK. In other words, even when the USA groups retweeted transnationally active accounts that created indirect transatlantic connections, the content that they retweeted still often related to the USA. Collectively and individually, the USA groups relatively rarely retweeted tweets with UK-related content (17 retweets in total) but the extent to which they retweeted tweets with content related to other countries in Europe (59) might suggest their grouping of UK antifascism within a wider European tradition. From the perspective of the UK groups, while they all also retweeted UK-related content posted by transnational accounts, individually and collectively they always retweeted tweets containing USA-related content to a greater extent (54 retweets in total).

Table 6. The locational content of the retweets.Footnote13.

The 329 retweets were also coded in relation to five different themes: action; ideological; organising; profiling; and reporting. The action theme was illustrated by retweets that made direct calls to action or represented forms of direct action themselves. These might be retweets calling on individuals to join a strike or demonstration or that ‘doxed’ political adversaries. For instance, @ldnantifascists retweeted a @IGD_News call to join the counterprotests against the Unite the Right rally that took place in Charlottesville, Virginia on 11 and 12 August 2017:

Best way to stop Alt-Right and Neo-Nazi violence in #Charlottesville is to show up in the thousands and #DefendCville-not ignore the threat.

The ideological theme was indicated by retweets that featured ideological statements, general expressions of solidarity, and identity and memory related content with the latter being the most pronounced. Examples include retweets containing manifesto and solidarity statements, claims about Antifa identity and accounts of historical antifascism. Indicative of this theme @NYCAntifa retweeted the following tweet from @antifaintl:

For those of you who don’t know: The Battle of Lime Street was fought in Liverpool 5 years ago today, when proscribed terror group ‘National Action’s’ ‘White Man March’ was met with all of Merseyside mobbing them, forcing them to hide in a lost luggage booth in the train station.

The organising theme was exemplified by retweets that sought to educate antifascist activists, share intelligence, or raise funds. Illustrative of this theme were retweets that highlighted fake Antifa Twitter accounts, provided information on how to start an Antifa group, or advertised merchandise for fundraising purposes. Another example is @brightonanti’s retweeting of @crimethinc’s educational tweet concerning tactical responses to tear gas:

Comrades in Minneapolis – this video from Chile shows how to extinguish tear gas canisters quickly, safely, and easily. Please pass it on! Verbal instructions below. Don’t let the police or #COVID19 cut off your air supply. Fight back! #icantbreathe #GeorgeFloyd #Minneapolis

The retweets associated with the profiling theme shared a common interest in a wide array of adversaries considered by the case groups to be ‘fascistic’ in some sense or another. These retweets outlined and defined perceived fascist threats sometimes using ridicule. Exemplifying this theme @RoseCityAntifa retweeted the following @FFRAFAction tweet:

British Revival, a campaign set up as an alternative to Extinction Rebellion encouraging young people to become ‘patriotic environmentalists’, was run by Michael Wrenn a former member of far right extremist organisation, Generation Identity

The reporting theme encapsulated retweets that provided commentary on contemporary antifascist activities. Most of the retweets grouped under this theme contained reports of Antifa-related protests. For example, @PhillyAntifa retweeted the following tweet by @AntiFascistNetw that contained a link to a longer demonstration report:

Neo-Nazi no-show in Glasgow yesterday. Nice statement from Anti-Capitalist Queers:[link]

The overall distribution of these themes, which sometimes co-appeared in single retweets, not only suggests each group’s different priorities when it comes to social media communication but also the sorts of mediated solidarity encapsulated in their transatlantic retweet connections (see ).

Table 7. The main themes referred to in the retweets.

shows that the groups only minimally retweeted those action- and organizing-orientated tweets that can be associated with more transformative sorts of mediated solidarity (see Croeser, Citation2018). For only @PhillyAntifa and @RoseCityAntifa were these themes not the two least represented. While the exact split of the ideological, profiling and reporting themes differed between groups, collectively the UK groups more often retweeted reporting-orientated tweets and the USA groups, ideological-orientated tweets. While these three themes account for most of the retweets at group and country level, as well as overall, the profiling-orientated tweets were a little less regularly retweeted even if for some groups they played a more significant role (e.g @MerseysideAfn). Overall, these findings suggest the groups’ tendency towards more shallow, traditional forms of mediated solidarity connected to, for example, the sharing of protest reports, manifestos and memories related to what antifascism is, and general information about perceived adversaries, rather than deeper, transformational forms of mediated solidarity that might, for example, involve calls for, and forms of direct action, or educational and fundraising activities.

This situation becomes even more clear when we consider the few retweets that most strongly encapsulate the transatlantic mediated solidarity facilitated by Twitter between the USA and UK groups. Of the 17 tweets retweeted by the USA groups that concerned the UK (see ), 11 included the ideological theme, six included the profiling theme and two included the reporting theme. Eight of the ideological tweets concerned memories of UK-based antifascism foregrounding the importance of digital memory work among antifascist activists (see Merrill et al., Citation2020).

Of the 54 tweets retweeted by the UK groups that concerned the USA (see ), 24 included the profiling theme, 19 included the reporting theme and 17 included the ideological theme (of which ten related to memory). Additionally, three retweets included the action theme and two included the organizing theme. This provides tentative evidence that the degrees of mediated solidarity extended from the UK groups towards their USA counterparts might not only exceed the reverse but also be qualitatively different in its transformative potential. This evidence also suggests that, the USA groups extend shallower forms of mediated solidarity towards their UK counterparts to establish historical legitimacy and collective identity, whereas the UK groups extend parallel forms of mediated solidarity to their USA equivalents to also highlight a general fascist threat and those efforts being taken to combat this threat. This means that on the spectrum of transatlantic solidarity, there is subtle asymmetry: the solidarity displayed by the UK groups is comparatively deeper and more transformative, even if this is not especially pronounced in absolute terms.

Conclusion

This article has suggested that the transatlantic digital connectivity facilitated by Twitter between the six chosen Antifa groups in the USA and UK is rather limited, lending credence to historical arguments that more meaningful attempts to connect antifascism in the two countries were made before social media. This not only complicates the idea that social media platforms are predisposed to facilitating transnational activism, but also different assumptions made about the state of the antifascist movement that originate from both Antifa groups themselves and their adversaries. In short, our findings suggest a very loosely integrated transatlantic Twitter network of antifascist groups.

Our analysis also indicates that the retweet solidarity conveyed by the six Antifa groups was mostly shallow in character. In other words, it was mostly concerned with expressing ideological support, sharing reports, and profiling adversaries rather than contributing to organizational efforts or forms of direct action. Nuancing these general findings, our analysis did suggest that the UK groups displayed a slightly greater tendency to extend more transformative mediated solidarity towards USA antifascist struggles. Overall, the relationship between the UK and USA groups appears to reflect the countries’ broader cultural relations with the latter historically connected to the former yet now in a position of greater global influence. Thus, the UK groups tended to echo their USA counterparts in emphasizing the heightened far-right threat exemplified by Trump’s presidential election and further amplified reports that conveyed the new-found media prominence of USA antifascism that commenced during his presidential term and has continued since. The USA groups meanwhile turned towards UK antifascism for more ideological reasons including to invoke a historical legacy rooted not only in the UK – where antifascist groups command relatively little mainstream media attention – but also, outside the exclusively English-speaking world, within a broader European antifascist tradition.

Our study points to the need for further research into these matters. This might benefit from exploring a broader selection of cases and other translocal and transatlantic digital linkages and networks beyond the anglophone. While we have focused on Antifa groups on different sides of the transatlantic and therefore our analyses might be interpreted as foregrounding the influence of geographical distance on mediated solidarity, we are not making any causal claims regarding the relationship between these factors not least because our findings also suggest that intergroup histories and dynamics related, in part, to common or competing political perspectives and threats likely also influence the digital connections between Antifa groups. Thus, much might be gained from further studying how all these factors influence the digital connectivity and mediated solidarity of Antifa groups. One place to start this effort may be with respect to those groups that are geographically close, including those from neighboring countries that are active in shared ‘transborder’ spaces or are responding to the same far-right activity. Future research might also target the role of memory within Antifa’s mediated solidarity and would also benefit from exploring the sorts of digital connectivity afforded to Antifa groups by platforms other than Twitter.

Beyond antifascism studies, this article’s contribution lies in further stressing the need for more detailed studies of digital connectivity and mediated solidarity that do not preemptively assume that translocal or transnational activism is an automatic by-product of social media use. There are, as we reveal, different shades and depths of such connectivity and solidarity. Furthermore, it highlights the potential of conceptualizing solidarity in new ways and gestures towards the role of historians as well as social movement scholars in doing this by not only problematizing the concept in new digital contexts but also by historicizing its development in relation to street activism, digital activism, and everything in between. In this sense, the article hopes to help configure a new emphasis on these matters.

Acknowledgments

This work was part funded by the Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST) (ESRC Award: ES/N0009614/1) and by a Swedish Research Council project entitled: Algorithms of Resistance: Analysing and harnessing anti-racist activism in the age of datafication (2019-03351). The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Samuel Merrill

Samuel Merrill is Associate Professor at Umeå University’s Department of Sociology and Centre for Digital Social Research. He specializes in digital and cultural sociology and his research interests concern the intersections between collective memory, digital media, social movements, and cultural heritage.

Nigel Copsey

Nigel Copsey is Professor (Research) in Modern History at Teesside University (UK). He has published extensively on anti-fascism in both national and transnational contexts. He recently co-edited Anti-Fascism in the Nordic Countries (2019) and Anti-Fascism in a Global Perspective (2020). With Samuel Merrill, he was the author of Understanding 21st Century Militant Anti-Fascism (2021), a report published by the Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats. Forthcoming projects include a global history of anti-fascism.

Notes

1. There have been recent cases of foreign Antifa activists joining conflicts in Syria and Ukraine, but this is exceptional.

2. The handbook was published before Trump’s election raised the profile of antifascist activism.

3. For their historical background see Copsey and Merrill (Citation2021).

4. *PA had a Facebook community page that is no longer available. ** In September 2019 PA’s Facebook page had around 4600 followers (Copsey & Merrill, Citation2021). *** PA’s Twitter account was public when the research was conducted but was later made private. **** RCA’s Facebook community page was briefly suspended in August 2019. ***** This date span covers two blogs. The first features 77 posts from between January 2013 and July 2017. The second features 10 posts since its launch in September 2018.

5. Twitter’s new private media policy (introduced in November 2021) may change this.

6. Ethical clearance for the projects within which the research for this paper was carried out was provided by CREST’s Security Research Ethics Committee and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Ref 2020–03017).

7. This may reflect differences in the amount of original content that these two accounts generated (see ).

8. This may also reflect differences in how much original content these two Twitter accounts generated (see ).

9. Excluding groups that did not retweet each other, only @NYCAntifa and @RoseCityAntifa display something close to reciprocal retweet activity (see ).

10. This is less likely for @PhillyAntifa where retweet activity seems to have been directed towards struggles in neighbouring states with national rather than transnational retweets overshadowing local retweets. The percentage proportion of @PhillyAntifa’s transnational retweets adheres to the pattern conveyed by three other accounts.

11. The weaker direct retweet connections (under five retweets – see ) do not appear in .

12. Retweets from accounts associated with the same national context as the retweeting group were not further scrutinized even if they contributed to indirect transatlantic connections. For example, the USA groups’ retweeting of the USA-based @AntiFashGordon and North American @IGD_News accounts and the UK groups’ retweeting of the UK-based @AntifascistNetw and @FFRAFAction were not analyzed in further detail as these primarily indicated national connections. Accounts that contributed retweets to the sub-sample which linked case groups across the Atlantic either had origins besides, beyond, or in both the USA and UK and were more widely transnational in scope.

13. Totals exceed those in because a single tweet could contain references to locations in more than one country.

References

- Andersson, L. (2016). No digital “Castles in the Air”: Online non-participation and the radical left. Media and Communication, 4(4), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i4.694

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

- boyd, D., Golder, S., & Lotan, G. (2010). Tweet, Tweet, retweet: Conversational aspects of retweeting on Twitter. In 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Honolulu, HI, USA (pp. 1–10).

- Braskén, K. (2020). Aid the victims of German fascism!’: Transnational networks and the rise of anti-Nazism in the USA, 1933-1935. In K. Braskén, N. Copsey, & D. Featherstone (Eds.), Anti-Fascism in a global perspective: transnational networks, exile communities, and radical internationalism (pp. 197–217). Routledge.

- Braskén, K., Copsey, N., & Featherstone, D. (Eds.). (2020). Anti-Fascism in a global perspective: transnational networks, exile communities, and radical internationalism. Routledge.

- Bray, M. (2017). Antifa: The anti-fascist handbook. Melville House.

- Cammeaerts, B. (2021). The new-new social movements: are social media changing the ontology of social movements? Mobilization, 26(3), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671X-26-3-343

- Copsey, N. (2016). Crossing borders: Anti-Fascist action (UK) and transnational anti-fascist militancy in the 1990s. Contemporary European History, 25(4), 707–727. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960777316000369

- Copsey, N. (2020). Radical diasporic anti-fascism in the 1920s: Italian anarchists in the English-speaking world. In K. Braskén, N. Copsey, & D. Featherstone (Eds.), Anti-Fascism in a global perspective: transnational networks, exile communities, and radical internationalism (pp. 23–42). Routledge.

- Copsey, N., & Merrill, S. (2020). Violence and restraint within antifa: A view from the United States. Perspectives on Terrorism, 14(6), 122–138. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26964730

- Copsey, N., & Merrill, S. (2021). Understanding 21st-Century militant anti-fascism, CREST Report. Available from: https://crestresearch.ac.uk/.

- Copsey, N., & Olechnowicz, A. (Eds.). (2010). Varieties of anti-fascism: Britain in the inter-war period. Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Croeser, S. (2018). Rethinking networked solidarity. In M. Mortensen, C. Neumayer, & T. Poell (Eds.), Social media materialities and protest: Critical reflections (pp. 28–41). Routledge.

- Della Porta, D., & Diani, M., Eds. (2015). The Oxford handbook of social movements. Oxford University Press.

- Dennis, J. (2019). Beyond Slacktivism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eggert, N., & Giugni, M. (2015). Migration and social movements. In D. D. Porta & M. Diani (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of social movements (pp. 159–172). Oxford University Press.

- Fenton, N. (2008). Mediating solidarity. Global Media and Communication, 4(1), 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742766507086852

- Fitzgerald, K. J., & Rodgers, D. M. (2000). Radical social movement organizations: A theoretical model. The Sociological Quarterly, 41(4), 573–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2000.tb00074.x

- Freelon, D., Marwick, A., & Kreiss, D. (2020). False equivalencies: Online activism from left to right. Science, 369(6508), 1197–1201. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb2428

- Furet, F. (2004). The Dialectical Relationship. In F. Furet & E. Nolte, Fascism and communism (pp. 31–39). University of Nebraska Press.

- George, J. J., & Leidner, D. E. (2019). From clicktivism to hacktivism: Understanding digital activism. Information and Organization, 29(3), 100249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.001

- Gerbaudo, P. (2017). From cyber-autonomism to cyber-populism: An ideological analysis of the evolution of digital activism. Triple C, 15(2), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v15i2.773

- Greiner, C., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2013). Translocality: Concepts, applications, and emerging research perspectives. Geography Compass, 7(5), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12048

- Halupka, M. (2014). Clicktivism: A systematic heuristic. Policy and Internet, 6(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/1944-2866.POI355

- Highfield, S., & Croeser, T. (2015). Harbouring dissent: Greek independent and social media and the antifascist movement. Fiberculture Journal, 26(26), 136–158. https://doi.org/10.15307/fcj.26.193.2015

- Kaun, A., & Treré, E. (2020). Repression, resistance and lifestyle: Charting (dis)connection and activism in times of accelerated capitalism. Social Movement Studies, 19(5–6), 697–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1555752

- Klein, A. (2019). From Twitter to Charlottesville: Analyzing the fighting words between the Alt-right and Antifa. International Journal of Communication, 13, 297–318. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/10076

- Koch, A. (2018). Trends in anti-fascist and anarchist recruitment and mobilization. Journal of Deradicalization, 14, 1–51. https://journals.sfu.ca/jd/index.php/jd/article/view/134

- Larsson, A. O. (2015). Comparing to prepare: Suggesting ways to study social media today and tomorrow. Social Media + Society, 1(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115578680

- Mercea, D., & Levy, H. (2019). Curing collective outcomes on Twitter: A qualitative reading of movement social learning. International Journal of Communication, 13, 5629–5651.

- Merrill, S., Keightley, E., & Daphi, P. (2020). Introduction: The digital memory practices of social movements. In S. Merrill, E. Keightley, & P. Daphi (Eds.), Social movements, cultural memory and digital (pp. 1–30). Mobilising Mediated Remembrance, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Merrill, S., & Lindgren, S. (2020). The rhythms of social movement memories: The mobilisation of Silvio Meier’s activist remembrance across platforms. Social Movement Studies, 19(5–6), 657–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1534680

- Merrill, S., & Pries, J. (2019). From #kämpashowan to #kämpamalmö: Framing antifascist struggles from the local to the translocal and back again. Antipode, 51(1), 248–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12451

- Mirrlees, T. (2019). The Alt-right’s platformization of fascism and a new left’s digital united front. Democratic Communique, 28(2), 28–46. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/democratic-communique/vol28/iss2/3

- Neumayer, C., Rossi, L., & Karlsson, B. (2016). Contested hashtags: Blockupy Frankfurt in social media. International Journal of Communication, 10, 5558–5579. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5424

- Tarow, S., & McAdam, D. (2005). Scale shift in transnational contention. In D. D. Porta & S. Tarrow (Eds.), Transnational protest and global activism (pp. 121–150). Rowman and Littlefield.

- Tarrow, S. (2005). The new transnational activism. Cambridge University Press.

- Vysotsky, S. (2021). American antifa: The tactics, culture, and practice of militant antifascism. Routledge.

- Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., & Sloan, L. (2017). Towards an ethical framework for publishing twitter data in social research: Taking into account users’ views, online context and algorithmic estimation. Sociology, 51(6), 1149–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517708140

- Xu, W. W. (2020). Mapping connective actions in the global alt-right and antifa counterpublics. International Journal of Communication, 14, 1070–1091. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/11978/2978