ABSTRACT

Based on work with three youth-led activist groups in Aotearoa New Zealand, we explore the hybrid relationship between online and offline activism. This hybridity serves as a ‘third space’ (Bhabha, Citation2004) that combines elements of collective and connective action. Our understanding of hybridity draws on and extends Bennett and Segerberg’s (2012) theory of connective action and MacDonald’s (2002) notion of ‘fluidarity.’ Building on their work, we interpret activist spaces as hybrid spaces where activist identities are constructed as both connective and collective. Hybrid activism contextualizes the ways corporeality remains central to the affective experience of many activist campaigns. The interacting affordances of each space generate possibilities for community organizing and community building that are qualitatively different than either on- or offline spaces alone. Communicative complexity Treré (Citation2018) and activist self-narration are key elements of the hybridity that emerged in our study. In addition, the connective action properties of digital media were maximized when physical and digital campaigns were porous. Digital and material spaces are therefore co-constructing and complementary.

Introduction

For young activists, digital media have become basic tools for disseminating information, connecting with communities that share their interests or political affiliations, and seeking support. Online activity is also increasingly seamlessly integrated with offline lives, augmenting and interweaving with, but not replacing, face-to-face activism. Thus, hybrid activist spaces are increasingly important.

Developed out of our interviews with and observations of three youth-led activist groups, our definition of hybridity embraces Homi Bhabha’s (Citation2004) view of hybridities as a ‘third space’ of emergent possibilities. In doing so, it combines and expands upon Bennett and Segerberg’s (Citation2012) theory of ‘connective action’ and MacDonald’s (Citation2002) notion of ‘fluidarity.’ Building on their work, we interpret activist spaces as hybrid spaces where activist identities are constructed as both connective and collective. In this space individual activists narrate themselves, building an activist identity in and through group activities that cross spatial boundaries while operating within clear organizational value structures and the movement goals of their groups, which are also connecting with other like-minded organizations.

Hybrid activism contextualizes the ways corporeality remains central to the affective experience of many activist campaigns, reflects the ‘collapsed contexts’ (Davis & Jurgenson, Citation2014) of digital and material worlds, and acknowledges the different types of access available to members of activist communities. While not all contemporary activism with an online presence is an example of hybridity, the interacting affordances of digital and face-to-face spaces generate possibilities for community organizing and community building that are qualitatively different than either on- or offline spaces alone. There is no ‘one size fits most’ understanding of just what hybridity will mean or offer to all organizations. Context matters.

Participants and methods

This work is drawn from a larger study of six youth-led activist groups in Aotearoa New Zealand.Footnote1 We defined ‘youth’ as those aged roughly 18–29, and we selected groups working across a range of issues.Footnote2 For this article, we are examining how three of the six groups use and talk about different spaces of activism, particularly social media and face-to-face events. We chose these three groups to represent our range of findings on this topic because they were the most consistent users of social media. The three groups are Protect Ihumātao, a Māori-led movement fighting the impact of colonization in reclaiming Indigenous land confiscated in 1863; ActionStation (AS), a ‘people-powered online petition platform’ addressing diverse social justice issues, including education on sexual consent in high schools, racism online, and mental health funding; and InsideOUT Kōaro (IO-K), a nation-wide group promoting rainbow youth visibility and safety in schools and communities.

We conducted one-to-one interviews with a total of 42 people from across the three groups: 13 from Protect Ihumātao, 15 from ActionStation and 14 from InsideOUT Kōaro. Participants also completed a brief demographic survey, based on the New Zealand Census questions. Sixteen participants identified as Māori, twenty-eight as New Zealand European and ten with other ethnicities. Ten people identified with more than one ethnicity. The participants were aged between 18 and 57, with an average age of 26. (Protect Ihumātao is youth-led, but includes older members.) Six participants were cis-male, twenty-nine cis-female and seven identified with other or multiple genders. Our participants were more ethnically and gender diverse than the population as a whole, likely reflecting the age cohort, which is more diverse than the population as a whole, and the concern ethnic and gender minorities have in combatting the inequalities they experience directly (Citation2021; Statistics New Zealand/Tataruranga Aotearoa, Citation2020).Footnote3

For each group, from 2018 to 2020, we conducted two interviews with individual participants approximately one year apart, as well as attending group events and meetings at which we took extensive fieldnotes. We also undertook an analysis of each group’s social media channels.Footnote4 We draw from all of these in the study below.

Conceptualizing online and hybrid activism

Research about digitally networked activism initially focused on comparing offline and online activism (McCaughey, Citation2014). However, as offline activism became increasingly enmeshed with the internet, different modes of thinking through interaction and hybridity emerged (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012; Castells, Citation2012; MacDonald, Citation2002; Milošević-Đorđević & Žeželj, Citation2016; Stewart & Schultze, Citation2019; Vromen, Citation2015). The research challenging spatial dualism has been especially pronounced as internet activism has moved from the more static and uni-directional Web 1.0 to the hyperconnectivity of the more dynamic Web 2.0 and its potential for increasing civic participation (Yang, Citation2016). Understanding the form and meaning of this participation is now a key feature of activist research.

Early studies such as MacDonald’s (Citation2002) argued that social media sharing, liking, and commenting reflects and produces a personalized ‘self’ trying to connect with others who are also seeking personal alliances and transformative possibilities. From this perspective, personalization can be seen as relaxing collective identity requirements that were a feature of older activist organizing principles (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012), but where the lack of collective identity formation does not presume lack of connection to a group or cause or signal a turn to individualism.

MacDonald (Citation2002, pp. 121–126) instead conceptualizes this personalization as ‘activist fluidarity’, a neologism signaling less collective but still connected identities, i.e. fluid solidarities. Here organizational structures are looser than in traditional social movement organizations, and relationships between individuals are mediated through ‘emotion,’ ‘embodied communication,’ and ‘visibility’ or ‘the public experience of self.’ Fluidarity thus retains an emphasis on the individual’s distinct experiences while embracing ‘the dynamism, complexity and plurality of contemporary social movements’ (Stewart & Schultze, Citation2019, p. 18).

In their theory of ‘connective action,’ Bennett and Segerberg (Citation2012) extended these ideas of personalized communication, discussing how group ties are replaced by large-scale and fluid social networks through iterative sharing of emotionally-charged ideas with the goal of building communities without collective identities. This is distinguished from older models of collective action where activism is coordinated via organizations, has a members-and-followers model, relies on collective identity, uses collective action framing, and relies on organizations to bridge differences among problem framings (Bennett & Segerberg Citation2012, pp. 750–751). Instead, in connective action, the starting point of action is self-motivated, and activism occurs through personalized sharing. Actions can be both customized and outsourced, e.g., to platforms like Twitter (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012, p. 757). As Jeppesen (Citation2018, p. 7) argues, ‘the potential virality of connective action frames translates into participatory leadership from multiple translocal sites, but with shared overall objectives.’ In this vein, Stewart and Schultze (Citation2019) demonstrate how connective action and fluidarity achieved through hybridized on- and offline activism are updated forms of, rather than replacements for, collective action and solidarity.

Seeing the hybrid relationship between on and offline activism also challenges early critiques of online activism as ‘lazy’ ‘feel-good’ clicking (i.e., clicktivism or slacktivism) (see Smith et al., Citation2019). Clicktivist arguments rested on a spatial dualist fallacy: the idea that online and offline are distinct spaces, usually predicated on the idea of offline activism as more ‘real’ than online activism (Craddock, Citation2019). Many scholars argue that notions of ‘spatial dualism’ are flawed. Specifically, Kolko et al. (Citation2000) challenge the idea that offline activism is more authentic because it is ostensibly more corporeal, while Craddock (Citation2019, p. 149) unpacks the gendered dynamics of spatial dualism, noting that ‘the binary construction of direct action as “real” activism versus online “slacktivism” is problematic because it minimizes online activism … , which women’s narratives reveal as being a central form of activism that they can combine with caring roles.’ Thus, the relegation of some spaces of resistance as more ‘real’ than others ‘can reinforce dominant gendered power structures while ostensibly fighting against them’ (Craddock, Citation2019, p. 137; 140). Further, as Trott (Citation2020) demonstrates, while some ‘hashtag activism’ like #MeToo is technologically easy, it can be emotionally and physically taxing given the vulnerability to online abuse and other repercussions. And Krista Lynes (Citation2015, p. 7) argues ‘the constitutive effects of race offline always already shape cyberspace and our interactions within it. It is in this constitutive sense that racial cybertyping reveals the effects of racism both on- and offline; cyberspace and “real life” cannot be separated into two mutually exclusive spaces.’

Treré (Citation2018) argues that online activism is rife with ‘communicative complexity’ as a result of the erosion of spatial boundaries. Thus, nuance is required to investigate how the affordances of digital media open the pathways to navigate the material barriers experienced by marginalized groups and how the porous relationship between online and offline engagement facilitates activist engagement, participation, and empowerment. Costanza-Chock (Citation2014, p. 50) theorizes a different form of communicative complexity through the idea of transmedia activist organizing. This ‘includes the creation of a narrative of social transformation across multiple media platforms, involving the movement’s base in participatory media making, and linking attention directly to concrete opportunities for action.’ As such, transmedia organizing adds complexity and hybridity to the layers of identity meaning-making and connections between on- and offline actions. This communicative complexity is another feature of ‘hybridity’ that we unpack below.

‘Traditional’ activist organizations often underestimate the commitment behind young activists’ online activity (Elliott & Earl, Citation2018, p. 3) and multiple studies find that young people who engage in either online or offline activism are more likely to engage in both (Lane & Cin, Citation2018, p. 1536; Milošević-Đorđević & Žeželj, Citation2016; Van Stekelenburg & Klandermans, Citation2017). For example, by producing live streaming of offline events and selfies as methods of contesting how others represent them, young activists can connect with people who might be unable to participate directly in offline activities. These networked connections can witness actions and participate from afar, increasing their own visibility and connectivity in activist spaces (Rodan & Mummery, Citation2018, p. 1; Stewart & Schultze, Citation2019) on their own terms rather than those of traditional gatekeepers and storytellers (Stornaiulo & Thomas, Citation2017). This is one way of producing what Castells (Citation2012, p. 250) refers to as a ‘hybrid of cyberspace and [offline] space … the space of autonomy.’ Social media allows activists to tell their stories in their own words, often through video narration (MacDonald, Citation2002). Even hashtags are frequently an effort by ‘counterpublic activists’ to exert some definitional control over a narrative and to help (re)shape discourses used to discuss social issues (Trott, Citation2020, p. 6).

Research on the relationship between online and offline activism reminds us that activism is communicative, and ‘movements and communication technologies are co-constitutive’ (Treré, Citation2018, p. 204). So too are the spaces of activism. When researchers talk about ‘online activism,’ the focus is generally on ‘the frontstage’ (e.g., Twitter tweets, Facebook posts), but the ‘backstage’ (e.g., Facebook Messages, Slack, Google Docs) is equally important and shapes the public-facing activity (Treré, Citation2018). Frontstage and backstage technologies have porous boundaries, and activities are in ‘continuous interaction’ (Treré, Citation2018, p. 210). Treré (Citation2018, p. 211) argues that these interactions help shape collective identities through connective action. Hence, researchers need to focus on the ‘communicative complexity’ between different online spaces, as well as between online and offline modes of engagement (Treré, Citation2018, p. 1). Digital affordances are key to offline activist success, undermining ‘the fallacy of spatial dualism’ (Treré, Citation2018, p. 8).

In short, the literature on the relationship between on and offline activism speaks to the limits of the spatial dualism concept because it fails to account for the hybridity of spaces and activist identity work (fluidarity) that digital media can facilitate. Hybridity has many valences. Following Bhabha’s (Citation2004) idea of hybridity as a ‘third space,’ we think about hybridity as facilitating new activist possibilities through connective action and activist fluidarity. Communicative complexity, corporeality, and activist self-narration are key elements of this concept of hybridity that emerged in our study.

Findings: connection, hybridity, corporeality

Rather than distinguishing groups by whether they engage primarily in connective or collective action (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012), fit into particular conceptual frames for autonomous digital media movements (Jeppesen, Citation2016, Citation2018) or work primarily on or offline, we argue it is more appropriate to look at the purpose of specific actions at a specific time. This emphasis on time and purpose emphasizes the fluid nature of hybrid activism and how activist identities and communities are shaped. Even within a group, different members will have varying senses of what ‘real’ activism looks like and where it takes place.

Social media is ‘like a whole new world’: online communities are both collective and connective

Bennett and Segerberg (Citation2012) argue that connective action replaces activist collective identities with fluid social networks. But Jemima (IO-K) and Madeleine (AS), like many of our participants, speak to different ways of doing community and building activist identities through shared values in fluid social networks. Connectivity is a process grounded in the building of and search for collectives, often ones that move between or coordinate on- and offline activities.

There is a huge power in the collective. And I think, as much as some people can do individually, you can do so much more when you’ve got a really passionate group of people. There’s such safety in numbers, and loudness in numbers […] such a volume in numbers that just can’t be matched by one person alone … . I definitely like using social media as my space to sort of blast my thoughts about things. But I wouldn’t just do that.

It’s more about building meaningful connections rather than getting as many people involved at a petition level, for example. […] It’s more like who those people are that are already on board and building stronger connections with them and then also inviting them through those connections to be able to take higher bar actions. […] And ActionStation takes movement generosity quite seriously and we understand that if we are making the effort to not only pursue and further our own campaign interest or organizational interest but actually the interest of everybody that we are allies with and consider ourselves in community or in relationship with, then that is going to be a far more powerful thing.

Jemima suggests that online activism that does not connect with a collective has its place but is insufficient on its own to make change. And Madeleine talks about how ActionStation’s online petition site uses the organization’s space and voice as a tool for building meaningful communities for connected and collective social action. Akin to many other translocal and transmedia groups, ActionStation’s collaborations with allies reinforces its commitment to addressing issues intersectionally, harnessing the digital affordances of their social media pages and petition site to collaborate and connect across groups and issues to build social justice solidarities (Jeppesen, Citation2018, pp. 7–8).

In reflecting on the relationship of on- and offline actions, other participants describe social media as a tool to help them stay connected to their communities during periods when they have no time for offline activism, or when they want to learn from others in a wider national or global network. Such comments reflect how the ‘different flows and challenges within a cycle of protest affect the way in which activists use social media’ (Mattoni, Citation2017, p. 498).

Jae from ActionStation offers an example of these spatial, connective, and collective ideas, ultimately describing social media as a ‘a whole new world’:

So with this [conservative politics monitoring] page, people can go ‘hey there’s heaps of stickers in town, can someone go and take some down’ or whatever. So that’s a way of using or mobilizing the collective or going ‘hey this rally’s coming up, we’re assuming that some people are going to be there, can someone manage that’ or whatever. So yeah, there’s definite power in a collective and the internet and social media is really helping that. And if I think about activism and Bastion Point and these things where it’s actual physical bodies present in a space as a collective, when I think of collective versus individual, that’s what I think of. But actually, social media is a collective as well, it’s like a whole new world.

Here Jae starts by talking about social media as a resource for organizing activities in the offline space, and in that sense, the digital space is facilitating the ‘real action’ in physical space in line with the ‘spatial dualism’ literature. She then elaborates that when she thinks of activism, she immediately thinks of embodied, offline protests, like the 506-day occupation of Bastion Point in New Zealand in the late 1970s. But she ends up critiquing the characterization of and division between online activism as individualized and offline protests as collective. Instead, these are complementary, and potentially collective, spaces.

Frances and Jemima also identify connective campaigns that bridge activist spaces. Frances (Protect Ihumātao) offers an example of an early campaign experience when the group was alerting politicians to the public’s increasing awareness of the justice issues at stake at Ihumātao. The power of social media turned what could be (only) offline actions into hybrid ones:

So the intention was to create another form of visual protest to influence the politicians. It’s all about the numbers. We had an event, ‘Hands Around The Land’, that attracted 300–400 people on a beautiful Sunday afternoon. Now it just happened a week later, [a group of us] went down to Wellington and we presented to the Social Services Select Committee at Parliament. So we were able to say to the politicians, ‘You will read in the media that there were 300–400 people at that event but you need to know that there were 13,000 hits on social media and multiple shares.’

Jemima from InsideOUT Kōaro talks about the visibility social media brings to the work IO-K does and the needs and interests of the queer community.

Last year, [we did] a project called ‘Out on the Shelves,’ and I saw stuff [about it] all over social media. In some of the schools … they’ve had really cool library setups about ‘Out on the Shelves,’ and I think that’s been a really wonderful, wonderful project, and resource now that so many people have access to this website that lists all of these rainbow-inclusive books.

An event like ‘Hands Across the Land’ could be interpreted as hyper-local, yet participation via social media magnified the political impact of the claims being pressed. Frances points out how both material and virtual supporters can be included in demonstrating to government and other officials the degree of popular support for their cause. It is the reach of connective action that makes the material petition and testimony more persuasive. Rodan and Mummery (Citation2018) call this ‘strategic witnessing,’ arguing that such witnessing generates both visibility and collective identity. Visibility campaigns, as described by Jemima, coincide in on- and offline spaces: ‘Out on the Shelves’ is itself a visibility campaign, and social media and websites promoting the campaign not only increase its audience but bring the content of that project into the online space (queer people and issues are ‘out on the online shelves’ now too).

Activism happens in hybrid spaces: online/offline fluidarities

Social media can reduce the cost of outreach in ways that do not fundamentally challenge how groups organize. However, Bennett and Segerberg argue that digital media networks can change the fundamental principles of organizing if there is the right interplay of technology and personal action frames so that ‘organizations relax collective identification requirements in favor of personalized social networking among followers’ (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012, p. 748).

ActionStation, part of the global OPEN network for online activism, offers a good example of personalization and collectivity. The original model of the OPEN network was ‘member-driven’ campaigns but ActionStation has been at the forefront of an evolution to a model of ‘values-driven’ campaigns (Hall, Citation2022). The ActionStation principles of organizing are deeply connected to personalization through social media as well as their own petition site. As Madeleine explains

‘Our ActionStation’ is a platform where anybody can start a campaign for something they care about and then that campaign goes to moderation by our member review panel to see if it’s consistent with ActionStation’s values and vision. If it is, it goes online and we support those community campaigners to achieve the goals that they want.Footnote5

Our observation of their social media channels found that ActionStation ‘personalizes’ most of their Facebook posts through collaborative cross-posting of other groups’ material, often with commentary added to shape the values and discussion as the material is shared on the ActionStation page. shows one of many such collaborations with the national youth-led prison abolitionist group JustSpeak. On the flip side, they post very little on Instagram, with most of their Instagram tagging and interaction coming from AS supporters who tag them in their individual posts. ActionStation is building a personalized network on Facebook, and others are using the imprimatur of ActionStation to personalize their own politics through tagging and sharing on Instagram. This seems best described as connectivity, but not collectivity.

Figure 1. ActionStation using Facebook to promote the social justice work of groups they supportFootnote6.

InsideOUT Kōaro and Protect Ihumātao are more hybrid and collective than ActionStation. While these groups’ use of social media also included ‘personalized sharing,’ this sharing was in the service of connecting people on social media with the group and their issues. For example, Protect Ihumātao’s Instagram posts have shifted over time from images of nature to memes about Treaty partnership and decolonization. They also post videos with cross-generational storytelling aimed at helping to strengthen community ties. And much more than ActionStation, Protect Ihumātao uses Twitter and Facebook for raw, unfettered access to activism as it is happening. is a screenshot from a live video shared during the period when police had moved in to try to remove Indigenous land protectors.

Figure 2. Protect Ihumātao using Facebook live to let supporters participate virtually in events during the occupation.

After using Facebook and Twitter to get more supporters physically on the land, Protect Ihumātao broadcast Facebook Live videos of peaceful actions on the land, such as group karakia (prayers) and waiata (songs). Occasionally the Facebook feed during the more intense period of the occupation took on the format of a TV show: Grayson, their Facebook Live correspondent, would walk around the encampment reading and responding to live comments from social media users posting on the Protect Ihumātao Facebook page. Protect Ihumātao was also very active with tagging and cross-posting in ‘red alert’ posts about threatened or in-progress major events in order to generate connective action to raise awareness and build a sense of urgency (See ). This included cross-posting from other groups but also posting across all of their own social media platforms. All are seen as spaces for political organizing, getting people to the land, and encouraging followers to contact politicians. Here, the hybridity of offline and online action and organizing is most apparent.

Figure 3. Protect Ihumātao using Twitter to make a plea for supporters to show up when bodies are needed to physically defend the land in real time.

Figure 4. ‘If you can’t get to the land, tweet about the cause’: hybrid activism where online actions are amplifying offline activities in real time.

show Protect Ihumātao using social media as an organizational and educational tool, blending online and offline ‘occupation’ and embodied support for land rights. This is most explicit in , where protectors like the first commenter who were not able to walk could still be there, and another commented on having a shared sense of breathing together, across space. These affordances of social media are interlinked, and over a multi-week event, the same people might connect in multiple ways at different times. Notice, too, that in a Tweet includes a video from a supporter that has been retweeted by Protect Ihumātao. A supporter’s social media personalization became part of the organization’s official media, demonstrating organizational hybridity directly in line with Costanza-Chock’s (Citation2014, p. 50) definition of transmedia organizing.

InsideOUT Kōaro also uses Facebook as a hybrid and interactive tool. For IO-K, Facebook is implicitly political in serving as a welcoming space for discussing issues and reading educational posts rather than an overtly political organizing space. As with Protect Ihumātao, InsideOUT Kōaro’s Facebook page is full of highly personalizable and sharable content. IO-K members were the youngest of our youth activists (they ‘age out’ of the group at 27), and they were also the highest users of Instagram in this study. Their Instagram page draws users in with vibrant color and activity, presenting a welcoming, affirming place for the rainbow community (see ). Like Protect Ihumātao, InsideOUT Kōaro rely heavily on livestreaming and not just static images. is an example of how this allows young people to interact with InsideOUT Kōaro activities even if they can’t attend in person.

Figure 5. InsideOUT kōaro’s Facebook page demonstrating a strong narrative of inclusivity, a wide range of issues addressed, highly personalized & personalizable space, and a bridging of online/offline. All of their social media pages are places of hope.

Shift hui is an annual multi-day social and educational gathering for rainbow youth. While the goal is to gather young people in one space (a marae, a Māori meeting house), social media extends this space in critical ways. Making use of the potential for Facebook Live to enable more youth to attend – for example, those who are too young to join in person – means InsideOUT Kōaro can hybridize the space of Shift hui, using connective action to build collective identity and commitment (see ). And when Covid forced the whole event online in 2020, IO-K made use of Discord, where different ‘channels’ allowed for chatting and replicating group spaces. These channels allowed InsideOUT Kōaro to continue to fulfil the group bonding and individual psychological support aspects of Shift. In an example of Treré's (Citation2018) communicative complexity: Discord also enabled features that would not have happened at a face-to-face event such as channels dedicated to participants sharing photos of their pets, book and podcast recommendations, and photos of their nature walks during lockdown.

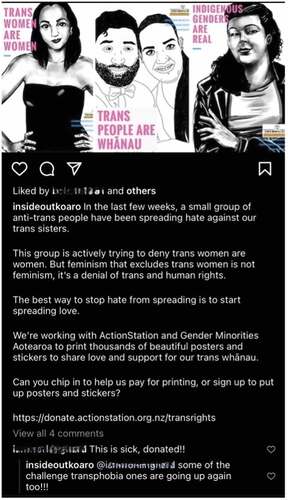

In addition to making Shift more accessible through Facebook and Discord, IO-K used Instagram to support queer youth. IO-K pre-recorded videos they then shared through Instagram to promote an inclusive and affirming space, connecting rainbow youth support with the promotion of Indigenous language and culture in the group, all in the context of promoting mental health for rainbow communities. shows how InsideOUT Kōaro extends this fluidarity in a few key ways: their Instagram post advertises posters and stickers to be shared in offline public spaces, a project undertaken in collaboration with ActionStation and Gender Minorities Aotearoa, a form of intersectional, values-driven connectivity. Such work is part of transmedia organizing that helps to construct social movement identity ‘beyond individual campaign messaging’ with the goal of ‘transforming the consciousness of broader publics’ (Costanza-Chock, Citation2014, p. 50). In line with Costanza-Chock’s theorization of transmedia organizing, we see collaboration across multiple groups, actions people can take in their daily lives, and participation that can be driven by movement members rather than relying on designated leaders.

Figure 7. InsideOUT Kōaro collaborating with other activists on a project demonstrating shared values, a project that connects visibility on- and offline.

These examples demonstrate MacDonald’s (Citation2002) argument that personalization of information – bringing one’s (or a group’s) perspectives to the posts that are being shared while operating in solidarity with other groups – is different from hyper-individualized and depoliticized ‘clicktivism.’ Sharing personalized material can require more engagement than signing an online petition: sharing is part of negotiating place and identity in a network (Lane & Cin, Citation2018, p. 1536). To share on digital media is to be ‘authentic’ in declaring where you stand and who you are, even if that ‘authenticity’ is not the whole self. As we see in the examples from InsideOUT Kōaro and Protect Ihumātao, these declarations are made in values-based and identity-based connection with others.

Further, both IO-K and Protect Ihumātao show how personalization regularly takes the form of ‘narrativizing their own story’ (Stornaiuolo & Thomas, Citation2017) to either counteract or expand the coverage offered by mainstream media sources and simultaneously manifesting their social identity within and outside of the group. Writing their own identities and stories into social media is a profound way of countering dominant ‘deficit’ narratives about LGBTQ+ youth and Indigenous communities. In short, young people are writing themselves into the media that have excluded them (Stornaiuolo & Thomas, Citation2017).

Secondly, self-narrativizing works to knit together on- and offline actions while building group identity, a ‘politics of representation [as] … civic activism’ (Stornaiuolo & Thomas, Citation2017, p. 348). Here, rather than sharing someone else’s content with one’s own personalized endorsement added, group members rewrite their own narratives to replace dominant narratives that exist about them or their campaigns. Our fieldnotes from one weekend during the height of the occupation at Ihumātao record one of the event marshals saying to the crowd of over 5000 that Protect Ihumātao was taking control of the media from now on: It would be ‘tikanga before TV.’ ‘Tikanga’ refers to indigenous protocols and ethics. Here the marshal is saying that rather than responding immediately to questions from the traditional media, the group would craft their own story in line with their worldview and share it through their Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter accounts, and other outlets as they desired and had capacity for. Such privileging is an example of social practices ‘anchoring’ activist media practices, ‘imposing their own logic on the way people interact with the media’ (Mattoni, Citation2017, p. 501). This is a counterpoint to studies finding media practices ‘anchor’ social practices, changing the way activism happens based on the structure of and demands of media such as TV or digital apps (Mattoni, Citation2017).

Protect Ihumātao’s Qiane spoke in her interview about multiple practices of self-narration and information sharing:

In many past movements the narrative was dictated by the media. Whereas here, the narrative is dictated by us, mostly via social media. Often when people who support us see a news report on TV, they come straight to our page to see if it’s true. Whereas in the past, the wider public would just take the news for what it was. Social media, and our multi-media campaign like the ‘Voices of Ihumātao’ video series we made, has helped us to really highlight the narrative that this is a whānau [extended family] issue, this is multiple generations of people, it’s people of different experiences and different backgrounds. […] Honestly, having two professional video and photo image-makers in the group is a luxury and … it shows our privilege. We’re so lucky we can have professional videos created every day for whatever we want in this campaign, and they go viral. 100,000 views of videos really help to push our messaging out and that’s been really powerful. This whole reclamation has been run off koha [donations]. We would release a daily social media with our needs in maintaining the reclamation/occupation, one day we needed paint, the next day it showed up. People donate money. People donate tents, food, clothing, toilet paper. The generosity and solidarity is incredible.

Here Qiane describes a rich example of Costanza-Chock’s (Citation2014, p. 50) transmedia organizing, while ‘working to ensure accessibility and accountability to those at the forefront of … anti-oppression struggles’ (Jeppesen, Citation2018, p. 3). The immediacy and personalization of social media made it the trusted source of information about the occupation as members of Protect Ihumātao shared the information online. ‘Voices of Ihumātao’ is a YouTube series the group filmed and released to let members speak about who they are and why this movement is so important to them. Other media stories tried to paint the movement as being a small group of ‘radical and professional’ non-Indigenous protestors (Qiane), so producing and sharing their stories was a powerful way to speak back to public perceptions, but also to build ties with members of the larger community.

A third form of self-narrativizing takes the politics of representation beyond disrupting dominant narratives of group identities (Stornaiuolo & Thomas, Citation2017, p. 348, 351) by modeling a just world and the values underpinning it. For example, ActionStation has a pinned post at the top of their Facebook page that details their expectations for online safety and respectful dialogue (see ), which was consistent with their Tauiwi Tautoko campaign to train non-Māori activists to engage with and attempt to diffuse racist rhetoric on social media. Rather than relying on the Facebook’s corporate, legalistic standards, ActionStation is working to create the kind of community they want to see in all spaces (see Figure 9). They ‘action’ this through their posting policy and moderation activities while also pressuring government to address online hatred via contracting research reports, press releases and media articles (ActionStation, Citation2019):

ActionStation’s mission is to tautoko (support) and whakamana (uplift) everyday New Zealanders to act together to create what we cannot achieve on our own: a society, economy and democracy that serves people and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother). […] We want our Facebook page to be a safe and progressive corner of the internet so we moderate the comments on this page. The principles that guide our moderation are collective wellbeing and whanaungatanga (familial relationship building). When we interact online, we also represent our families, communities and heritage. When we make comments, we are also speaking to other peoples’ families, communities and heritage. We have the power to say things that will uplift the mana of others, or harm others – especially those families, communities and heritages that have experienced widespread or structural harm and violence.

Here ActionStation is engaging in community building (connective action) in the online space and simultaneously in a form of hybrid action to impact offline communities. The use of te reo Māori to express and specify their values demonstrates how this group is rooted in a particular, physical place while they operate as a translocal online platform. Through living these values digitally and materially, they bring together connective and collective identities.

Embodied connections and sticky affects: the limits of living digitally

Social media offer many ways to connect with others, personalize action, and build communities with a shared sense of purpose, and often a shared identity. And digital media more broadly have eased the behind-the-scenes work of activists in many important ways: Google Drive and Slack make rapid organizing around busy schedules much easier. Zoom, Skype, What’s App and other programs enable far-flung group members to join meetings they would otherwise miss. However, the participants in this study talked about the need for face-to-face actions to encourage and maintain members’ engagement and enhance social relationships and connective identities. While Facebook messages and emails might spark interest in events, what keeps members involved is feeling part of a collective endeavor, having face-to-face conversations, sharing food and blowing off steam – in addition to ‘doing the work.’ The affect generated through embodied engagements in non-digital spaces is difficult to reproduce in a Zoom meet-up.

For example, online spaces have been essential for members of InsideOUT Kōaro – young people, regardless of their physical location, can discover and connect with other queer young people and gain greater acceptance and knowledge through online communities. Yet, as the quote from Daisy below illustrates, central to IO-K’s members’ connection to the group is offline events and actions like the annual Day of Silence, public and school workshops on rainbow issues, and information stalls at campus and community events.

I think that’s what energizes us and motivates us is when we have – even if it’s just a really small group of young people, you know, even if it’s just our volunteers meeting up with each other, and sharing both their positive and negative experiences, and actually hearing each other, and supporting each other – that really energizes me to commit myself to this stuff.

ActionStation members Jae and Oliver argue that Tauiwi Tautoko was successful in large part because the ‘keyboard warriors’ tackling racist comments online have spent significant time together in offline spaces:

I think the initial human and face-to-face interaction was really important. […] I mean you get a feel for somebody and that developed that trust through that initial human meeting

We had spent those hours together in the first hui [before launching Tauiwi Tautoko], and you can put a name to a face, it’s not just an online profile. … And then, of course, at the last hui, you feel really like you know them really well because you’ve spent two months responding to racism online together, supporting them

When Áine from ActionStation was asked what made the campaign she worked on for Fossil Free UoA so successful, she pointed to the need to support digital community with face-to-face connection, reflecting Treré's (Citation2018) idea of ‘communicative complexity’:

I think [it succeeded because of] the combination of the ability to communicate quite collectively and rapidly on something like Slack and meet face-to-face

Madeleine reflected on why AS is so successful, suggesting that dedicated time for collective reflexivity – especially where at least some members can meet face-to-face for this engagement even as others join virtually– is essential to activism but missing from the rapid response online-only activities:

I think ActionStation has done that [self-questioning and reflexivity] very well [with] a couple of smaller things about the way that the organization is run that helps you consistently reflect, and one of them is we do fortnightly retrospective meetings where you set aside an hour and basically you ask, ‘in the past two weeks, what went well, what didn’t go well, what did we learn and how do we do better next time?’

For a group like Protect Ihumātao fighting for land, there was a real need to be in connection with – to be on – that land with others. In the interview with Qiane, quoted above, she speaks to the need to build the community that Māori want to see and to the kind of mutual support that offline actions provide – food, music, dance, gardens:

[MP] Marama Davidson has talked about recently coming to Ihumātao and it being reflective of what community should be like […] We have three caravans here that are wellness tents, so they’re not for people with sickness, they’re to keep people well. And so we have Mirimiri [massage] and we have Rongoā Māori [traditional medicine]. We are living the way society should be living in the sense that if you don’t have anywhere to sleep, here’s a bed. If you don’t have any kai [food], here’s some kai.

What we observed at group meetings was how a commitment to physically being together for multiple hours also meant committing to sitting with others with whom you were (sometimes heatedly) disagreeing until that disagreement had been worked through. Everyone gets to speak, even when it is tedious or fraught. Learning to be present with the bodies and energies of others was part of the activism to protect Ihumātao.

The activists in our study frequently articulated their enjoyment of offline activism but it was still part of their online activism. Many activists who are deeply engaged with digital media are building up a sense of commitment to a network, are embedded in online communities, have an affective relationship with their digital networks and feel a sense of presence when connecting online. This is different from merely ‘using’ social media to further enhance offline work (see Smith et al., Citation2019). Part of this may be different criteria for ‘effective’ action or dependent on the goal of a campaign. But in either case, there’s little point in arguing for the primacy of one mode over the other, or of sharp distinctions between the two spaces. Thus, our work supports the thesis put forward by Lane and Cin (Citation2018) and Christensen (Citation2011, n.p.): ‘being involved in effortless political activities online does not replace traditional forms of participation, if anything, they reinforce offline engagement.’

Conclusion

In our study we found little to support the idea of spatial dualism. While participants sometimes spoke as though offline actions were more ‘real’ or represented a deeper commitment, through the course of their interviews they articulated a more porous spatial relationship, one that was rife with ‘communicative complexity’ (Treré, Citation2018). Similarly, we found that hybridity is useful for understanding social (collective and connective) identities in activist groups in addition to thinking about the ‘spaces’ of activism. Connective action, like personalizing and sharing videos from the Ihumātao occupation or participating in Shift with InsideOUT Kōaro via Facebook Live, is individualized and emotionally-motived fluidarity (MacDonald, Citation2002). It is also collective in the sense of ‘we-ness’ (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012; Stewart & Schultze, Citation2019), and in the care for others that grounds the work (Sligo et al., Citation2022). This we-ness is particularly pronounced when activists interact with groups in ‘frontstage’ and ‘backstage’ digital spaces (Treré, Citation2018).

We were finishing data collection when the COVID-19 pandemic forced groups to pivot exclusively to online actions through periods of ‘lockdown’ in 2020. Activists talked about what they missed about being face-to-face for events, but also how much they valued connecting with their communities through digital means. Shift hui (InsideOUT Kōaro) happened exclusively online to ensure this significant event went ahead. Protect Ihumātao introduced new modes of engagement such as a ‘fireside chat’ (webinar) with one of the leaders in the house on the reclaimed land. ActionStation facilitated Zoom discussions about key policies. All of these events were enhanced by the previous hybrid actions that provided a sense of community, which online actions then sustained through the pandemic. In this sense, being able to pivot online and keep working does not undermine the affective centrality of hybridity so much as confirm its status as unique ‘third space’ (Bhabha, Citation2004) that could sustain groups through pandemic lockdowns.Footnote7

Young activists articulated few distinctions between online and offline. Rather, these spaces – and specifically the actions that occur there – are hybridized. Activist spaces are hybrid partly because people are embodied both digitally and corporeally (Magnet, Citation2007). Bodies are not erased online but are hyper-visible. We saw this as members of Protect Ihumātao and InsideOUT Kōaro made their material selves central to their online work. Indeed, the materiality of offline discrimination makes the self-narrativizing features of online spaces critical to the decolonial and queer campaigns these activists are pursuing. The connective action properties of digital media are maximized when physical and digital campaigns are porous.

In sum, hybrid action among our participants looked somewhat different from Bennett and Segerberg’s (Citation2012) definition. In their model, hybrid action is in between connective and collective forms of engagement, where ‘conventional organizations operate in the background of protest and issue advocacy networks to enable personalized engagement’ (p. 754). Rather, we found that ‘hybrid activist spaces’ encompassed activists taking advantage of the affordances of offline and online modes of engagement in complementary ways through a symbiosis of activities and spaces. If we were to build a model from our findings, it would center neither digital nor material spaces but instead represent them as co-constructing and complementary. As Jemima from InsideOUT Kōaro says ‘there’s so many different ways to do activism these days’ and none of them can be isolated as more ‘real’ than others or as the root of successful action.

Ethic statement

Ethics approval granted by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee, reference code 18/045.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carisa R. Showden

Carisa R. Showden is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Social Sciences at the University of Auckland. Her work is interdisciplinary, and uses feminist, queer, and phenomenological theories to examine gender and violence, critical theories of political agency, and youth political activism, among other issues.

Emma Barker-Clarke

Emma Barker-Clarke is a violence prevention educator and PhD candidate at the University of Auckland. Her current research is co-constructed with young people and explores how their developing perception of gender influences the perpetration and victimisation of peer-to-peer image-based sexual abuse. Emma completed her Masters in Criminology and Criminal Psychology, researching the suitability of violence prevention programmes for young people who perpetrated intimate partner violence in teenage relationships.

Judith Sligo

Judith Sligo is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine at the University of Otago. Judith has a range of research interests but much of her work has focused on children, young people and family well-being. She has a particular interest in issues of equity. Her research has involved working with young people across a variety of contexts using different methodologies.

Karen Nairn

Karen Nairn is a Professor in the School of Education at the University of Otago. Her current project focuses on what inspires young people to join others to create social change. This research on youth-led activism builds on her earlier work with young people who grew up during New Zealand’s economic reforms, which explored their post-high school paths in the book Children of Rogernomics: A neoliberal generation leaves school.

Notes

1. See Nairn et al. (CitationCitation2022).

2. While our groups were ‘youth-led,’ some members were older than 29. We allowed participants to self-define the parameters of ‘youth’ when deciding whether to participate.

3. According to the 2018 New Zealand census, the ethnic identification in the country was 70.2% European, 16.5% Māori, 8.1% Pacific peoples, 15.1% Asian, and 2.7% other ethnicities. (Exceeds 100% because respondents could select multiple ethnic identities.) In 2020, Statistics New Zealand reported the adult (18+) population to be 48.9% male, 50.7% female, and .3% ‘other gender’.

4. There were exceptions to this process: e.g., not all interviewees consented to a second interview. Protect Ihumātao is youth-led but has many middle-aged and older members, so a group interview was conducted with the ‘older’ contingent and individual interviews only with younger members.

5. These values include ‘honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi,’; ‘inclusive and diverse communities’; ‘equality and fairness,’ among others. For more on ActionStation’s values-driven approach, see Nairn et al. (Citation2022).

6. JustSpeak is working to eliminate incarceration. For more on their work see Nairn et al. (Citation2022).

7. Our data collection ended in mid-2020, which means we cannot speak to the effects of the longer lockdowns through late 2020 and mid-late 2021 that may have attenuated some group ties precisely because online rather than hybrid actions had to carry an increased burden of holding together fluidarities.

References

- ActionStation. (2019, February 18). Report calls for action to address harassment online. https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO1902/S00124/report-calls-for-action-to-address-harassment-online.htm

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

- Bhabha, H. (2004). The location of culture. Routledge.

- Castells, M. (2012). Networks of outrage and hope. Polity.

- Christensen, H. S. (2011). Political activities on the internet: Slacktivism or political participation by other means? First Monday, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v16i2.3336

- Costanza-Chock, S. (2014). Out of the shadows, into the streets!: Transmedia organizing and the immigrant rights movement. MIT Press.

- Craddock, E. (2019). ‘Doing ‘Enough’ of the ‘Right’ thing: The gendered dimension of the ‘Ideal Activist’ identity and its negative emotional consequences. Social Movement Studies, 18(2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1555457

- Davis, J. L., & Jurgenson, N. (2014). Context collapse: Theorizing context collusions and collisions. Information, Communication & Society, 17(4), 476–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.888458

- Elliott, T., & Earl, J. (2018). Organizing the next generation: Youth engagement with activism inside and outside of organizations. Social Media + Society, 4(1), 205630511775072. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117750722

- Hall, N. (2022). Transnational advocacy in the digital era. Oxford University Press.

- Jeppesen, S. (2016). Understanding alternative media power: Mapping content & practice to theory, ideology, and political action. Democratic Communique, 27, 54–77.

- Jeppesen, S. (2018). Digital movements: Challenging contradictions in intersectional media and social movements. Communicative Figurations Working Paper No Working Paper No, 21, 1–25.

- Kolko, B. E., Nakamura, L., & Rodman, G. B. (2000). Race in cyberspace: An introduction. In B. E. Kolko, L. Nakamura, & G. B. Rodman (Eds.), Race in cyberspace (pp. 1–13). Routledge.

- Lane, D. S., & Cin, S. D. (2018). Sharing beyond slacktivism: The effect of socially observable prosocial media sharing on subsequent offline helping behavior. Information, Communication & Society, 21(11), 1523–1540. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1340496

- Lynes, K. (2015). Cyborgs and virtual bodies. In L. Disch & M. Hawkesworth (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.7

- MacDonald, K. (2002). From solidarity to fluidarity: Social movements beyond ‘collective identity’—the case of globalization conflicts. Social Movement Studies, 1(2), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/1474283022000010637

- Magnet, S. (2007). Feminist sexualities, race and the internet: An investigation of suicidegirls.com. New Media & Society, 9(4), 577–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807080326

- Mattoni, A. (2017). A situated understanding of digital technologies in social movements. Media ecology and media practice approaches. Social Movement Studies, 16(4), 494–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2017.1311250

- McCaughey, M. (2014). Cyberactivism on the participatory web. Routledge.

- Milošević-Đorđević, J. S., & Žeželj, I. L. (2016). Civic activism online: Making young people dormant or more active in real life? Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.070

- Nairn, K., Sligo, J., Showden, C. R., Matthews, K. R., & Kidman, J. (2022). Fierce hope: Youth activism in Aotearoa. Bridget Williams Books.

- Rodan, D., & Mummery, J. (2018). Activism and digital culture in Australia. Roman and Littlefield International.

- Sligo, J., Besley, T., Ker, A., & Nairn, K. (2022). Creating a culture of care to support rainbow activists’ well-being: An exemplar from Aotearoa/New Zealand. Journal of LGBT Youth, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2022.2077274

- Smith, B. G., Krishna, A., & Al-Sinan, R. (2019). Beyond slacktivism: Examining the entanglement between social media engagement, empowerment, and participation in activism. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(3), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1621870

- Statistics New Zealand/Tataruranga Aotearoa. (2020). Ethnic group summaries reveal New Zealand’s multicultural make-up. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/ethnic-group-summaries-reveal-new-zealands-multicultural-make-up/

- Statistics New Zealand/Tataruranga Aotearoa. (2021). ‘LGBT+ population of Aotearoa: Year ended June 2020.’. https://www.stats.govt.nz/reports/lgbt-plus-population-of-aotearoa-year-ended-june-2020

- Stewart, M., & Schultze, U. (2019). Producing solidarity in social media activism: The case of my stealthy freedom. Information and Organization, 29(3), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.003

- Stornaiuolo, A., & Thomas, E. (2017). Disrupting educational inequalities through youth digital activism. Review of Research in Education, 41(1), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X16687973

- Treré, E. (2018). Hybrid media activism: Ecologies, imaginaries, algorithms. Routledge.

- Trott, V. (2020). Networked feminism: Counterpublics and the intersectional issues of #metoo. Feminist Media Studies, 21(7), 1125–1142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1718176

- Van Stekelenburg, J., & Klandermans, B. (2017). Protesting youth: Collective and connective action participation compared. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 225(4), 336–346. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000300

- Vromen, A. (2015). Campaign entrepreneurs in online collective action: GetUp! in Australia. Social Movement Studies, 14(2), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2014.923755

- Yang, G. (2016). Activism. In B. Peters (Ed.), Digital keywords: A vocabulary of information society and culture (pp. 1–17). Princeton University Press.