ABSTRACT

This article is based on an exploratory study of jeevanshalas, a network of ‘schools for life’ run by the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA), an anti-dam movement in the Indian states of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra that did not succeed in its mission of stopping the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam. Based on participant observation and conversations with movement leaders, teachers, administrators, parents and community volunteers, and on participatory research with children living in the localities of Jeevan Nagar and Trishul, Maharashtra, this article illuminates how the NBA reinvented itself through education. It argues that the jeevanshalas offer a model of long-term sustainability for social movements whose aim is not necessarily to grow the movement’s membership but to catalyse wider societal change that might eliminate the need for the movement. The findings suggest that the NBA’s understanding of the social purpose of education reflects a view of young people as political agents whose voices shape the community’s collective future, in marked contrast with India’s state-run depoliticising education system. The jeevanshalas thus represent a previously under-researched model of social movement led education whose explicit aim is not to train movement agents but to leverage the transformative potential of education to address underlying patterns of oppression. The article theorises this rearticulation of the concept of ‘social movement schools’ through Spivak’s notion of ‘infrastructural followup’, which parallels recent debates about the nature of prefigurative politics.

Introduction

Education is central to activism, and activism is in turn central to education. This is particularly true when it comes to effecting social change that addresses the issues of environmental decay and environmental justice. Environmental social movements often seek to educate the public as well as their members about the environmental and human costs of extractivist policies, consumerist lifestyles and the pursuit of progress central to our ‘runaway world’ (Leach, Citation1968). Educators, too, are increasingly concerned with tackling the ‘environmental multi-crisis’ (Litfin, Citation2016) of climate change, biodiversity loss, endemic inequality and other mounting challenges. Doing so in the context of depoliticised and often outdated education systems has led many to look for inspiration in activist pedagogies (Hodson, Citation2014; Lowan-Trudeau & Niblett, Citation2017; Sutoris, Citation2022a), as Crouzé et al. (Citation2023) recently demonstrated in their analysis of strikes against climate change as catalysts for democratic engagement among young people in Belgium. Indeed, both the practices of and the knowledge generated by social movements are profoundly relevant to the theory and practice of education (Niesz, Citation2019).

Grassroots environmental social movements in particular have been recognised for generating ideas and practices that are better suited to meaningfully address environmental decay than mainstream formal education systems (Kahn, Citation2010; Misiaszek, Citation2016; Prakash & Esteva, Citation2008). However, empirical research into educational efforts by social movements is scarce, and it remains a relatively unexplored yet promising area of social movement research (Isaac et al., Citation2020), as does the study of the intellectual contributions made by activists and of the learning processes unfolding within activist movements (Choudry, Citation2015). This article addresses the nexus between social movements and education by reporting on a study of educational efforts made by the Narmada Bachao Andolan [Save the Narmada, or NBA], an anti-dam movement that operates a network of jeevanshalas (schools for life) in the Indian states of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra.

This research is motivated by two main objectives. First, it aims to illuminate the ways in which the NBA – a movement with an almost 40-year history that, even as it achieved improved rehabilitation for displaced families, ultimately did not accomplish its key aim of stopping the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam on the Narmada river – adapted to changing circumstances by diversifying its efforts through building schools. As Driscoll (Citation2018) has argued, a sustained commitment to environmental activism is not necessarily formed through membership in an organisation but through factors such as life events, a personal mission and a strong connection to nature. All these factors play a significant role in the jeevanshala pedagogy, which may help explain why the NBA’s educational work has helped the movement maintain momentum in the face of adversity. The sustainability of movements also depends on support from local populations, particularly where the state is hostile toward a movement. Educational efforts can help build and maintain this type of support, as Pahnke (Citation2018) demonstrated in the case of the Brazilian Landless Movement, whose educational projects under the banner of Educação do Campo (Education for the Countryside) gave it greater legitimacy and helped protect it from being persecuted by government authorities. Jeevanshalas similarly provide NBA activists with an important interface with local populations, which strengthens support for the movement, even in areas not directly affected by the dams being built on the Narmada River. The NBA’s work in education points to its underlying strategies for long-term sustainability, and also challenges the conventional historiography of the NBA as a largely failed movement (Nilsen, Citation2013; Ranjan, Citation2018).

The second objective of this study is to put to the test the notion of ‘social movement schools’, which Isaac et al. have defined as ‘organizational spaces deliberately created by movements to train, educate, mentor, and otherwise prepare individuals for work as effective movement agents’ (Citation2020, p. 161). The research presented in this article problematises this definition. While jeevanshalas are spaces with intentional pedagogies for ‘directing the mental, moral and tactical disposition of participants’ (Isaac et al., Citation2020, p. 162), they are not primarily intended to generate new NBA members. They instead fill a vacuum in the provision of education to the subaltern populations in the Narmada region. Jeevanshalas have adopted a pedagogy designed to prevent the exploitation of these communities, and to empower young people to assert their place in a rapidly changing India without sacrificing their ancestral traditions and their connection to the land, the river and the forests. Some graduates have gone on to participate in the NBA, which movement leaders see more as a welcome by-product of a jeevanshala education than its primary aim. Jeevanshalas thus offer a model of long-term sustainability for social movements, wherein the aim is not necessarily to grow the movement’s membership but to catalyse wider societal change that might in time eliminate the need for the movement.

The article presents this argument in three parts. After outlining the methodology, it provides a historical contextualisation of the NBA’s struggle, which identifies the dynamics that gave rise to the movement and which the jeevanshalas seek to eliminate. It then presents an ethnographic account of learning in the jeevanshala in Jeevan Nagar, including a brief discussion of the impact of this learning on students’ environmental imaginations. It demonstrates how this account supports a rethinking of the concept of ‘social movement schools’ along the lines of Spivak’s idea of the ‘infrastructural followup’ (Spivak, Citation1999), which is a move consistent with Yates (Citation2015) rearticulation of prefigurative politics. It concludes by reflecting on the potential of this conceptualisation to offer new models for citizenship and environmental education, and thus to intervene in debates about the social purpose of education in the face of environmental decay.

Methodology

The research presented in this article is part of a larger, multi-sited ethnographic project that investigated the educational potential of environmental activism in India and South Africa (Sutoris, Citation2022a). While the larger project relied on long-term, immersive research at two research sites (a dam resettlement site in northern India and a township in South Africa that suffers from high levels of industrial pollution), this article is based on data collected during a short, intensive period of fieldwork conducted in Jeevan Nagar and Trishul, Maharashtra in September 2017, communications with NBA activists before and after this field visit, and a review of documents and literature pertaining to the jeevanshala.Footnote1 The research presented here is therefore more exploratory than the work previously published about the other research sites (Sutoris, Citation2021, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). This article is, nonetheless, informed by the comparative insights of the larger project, particularly those into the relationship between grassroots social movements, narratives of development and environmental decay.

The fieldwork relied on a range of qualitative research methods. These included 8 extended semi-structured interviews (of these, 2 were with movement leaders, 4 with jeevanshala teachers, and 2 with community members involved with running the school), and an extended focus group with 7 local community members, most of whom were parents of children studying in the jeevanshala (). The fieldwork took place at the school in Jeevan Nagar and in the nearby town of Trishul, where the NBA operates a student dormitory. This site was chosen due to its accessibility and high concentration of NBA-affiliated activists. The study relied on opportunistic and snowball sampling. The interviews and focus group were conducted in local languages (Pavri, Marathi and Hindi) with the help of translators.

The fieldwork also involved the observation of lessons and extracurricular activities at the school, and the organisation of a participatory ‘temporal arc’ exercise, in which children at the school were asked to draw pictures of what they imagined their community looked like 100 years ago, and how it might look 100 years into the future. This technique was part of a repertoire of visual-ethnographic participatory methods deployed in the larger research project and described in detail elsewhere (Sutoris, Citation2021). This method, which was motivated by the recognition that children are often overlooked as participants in anthropological research and inspired by previous studies that utilised participatory drawing (Johnson et al., Citation2012), was intended to stimulate the children’s environmental imagination and illuminate their understandings of anthropogenic environmental decay, as informed by the jeevanshala education and wider experience of life in this region. While this method was a form of creative pedagogy consistent with the activist pedagogy of the jeevanshala and therefore straddled the participation side of participant-observation, it was not primarily intended as an intervention. The researcher’s role in the activity was to explain the assignment to the students and let them work on their drawings independently.

The research took place with ethics approval by the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, UK. Except for two movement leaders who gave consent to be identified – Medha Patkar and Yogini Khanolkar – all the data was anonymised and no names or identifying details are used in this article. The people who appear in the photographs published in this article gave their consent to be photographed, and the legal guardians of the children participating in the drawing activity consented to the children’s participation. All research activities were undertaken under the supervision of the school staff.

All the interview and focus group data was transcribed and translated into English and analysed for patterns of thematic divergence and convergence (LeCompte & Schensul, Citation2013). The children’s drawings were analysed for their depiction of themes central to the research project – including the relationship between the human and non-human/more-than-human elements – using the tools of composition analysis and visual semiotics (Aiello, Citation2020).

The overall aim of the methodology was to construct what van Maanen (Citation2011) calls ‘jointly told tales’ of life in a jeevanshala as it relates to the material realities of the populations affected by the Narmada struggle, and to do so in the context of the local, historical, national and global dimensions of authoritarian developmentalism, accelerating environmental decay and the environmentalism of the poor (Martinez-Alier, Citation2012).

Displacement, resistance and grassroots school-building

The NBA was formed in response to a long history of exploitation of indigenous populations in the name of ‘development’, epitomised by the construction of large dams. These concrete behemoths have been central to the development imagination of India’s political elites since the country gained independence from Britain (Sutoris, Citation2016; Zachariah, Citation2012). Described by Jawaharlal Nehru, independent India’s first prime minister, as ‘temples of modern India’ (Guha & Martinez-Alier, Citation1997, p. 165), as many as 4,000 large dams were built between 1947 and 2000 (Klingensmith, Citation2007, p. 212); 44,182 people on average were displaced by each dam (Dias, Citation2002, p. 5). At the turn of the 21st century, it was estimated that India had displaced as many as 20 million people in the name of ‘development’, of which 65% was due to large dams (Dwivedi, Citation1999, p. 44).

Damming the Narmada, India’s largest west-flowing river, was conceived in 1946; the foundation stone was laid by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1961. The original blueprint entailed building 30 large, 135 medium, and 3,000 minor dams on the Narmada and its tributaries (Maitra, Citation2009, p. 196). The construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam, the largest of these projects, began in 1987. It was estimated that the dam would uproot as many as 40,000 families upon completion, most of them indigenous peoples or Adivasis (Modi, Citation2004).

Discrimination and exploitation of the Adivasis has a long history in India. During the colonial period, ‘tribal’ Adivasis were seen by the colonial authorities as ‘primitive’, ‘childlike’ and ‘violent’. The state impinged on their lifestyles by restricting their access to natural resources and cracking down on their agricultural practices (Das Gupta, Citation2020). India’s independence did not fundamentally transform the relationship between the state and the Adivasis; as Ramachandra Guha has argued, Adivasis ‘have gained least and lost most from six decades of democracy and development in India’ (Guha, Citation2007). These longstanding patterns of oppression and exclusion gave rise to the NBA’s activism and eventually helped it capture the public’s imagination in unprecedented ways.

Although protests against large dams have a long history in India, dating back to the Mulshi satyagraha [insistence on truth] of 1920–1924 (Vora, Citation2009), it was the NBA that brought anti-dam struggles firmly into the country’s public consciousness. Protests against the Sardar Sarovar Dam began as early as 1977 in the Nimad region of Madhya Pradesh; by 1989 the movement had gained significant momentum (Gadgil & Guha, Citation1994, pp. 112–113). The NBA was distinguished from earlier movements by its wide reach, its ‘tenacity in the face of government repression’, sympathetic coverage in the media both at home and abroad, and links with environmental groups elsewhere, including Japan and the United States (Gadgil & Guha, Citation1994, p. 113). Influential public figures, including Booker Prize-winning novelist Arundhati Roy (Citation1999), social worker Medha Patkar (Bose, Citation2004) and filmmaker Anand Patwardhan (Citation1995), have helped amplify the movement’s message, which encompasses a sophisticated critique of India’s development trajectory. As Krishna Mallick writes, the NBA exposed ‘the role of the state and the “modern Western” scientific project of dam-building, arguing that science in the service of large-scale capitalist and bureaucratic projects aimed at the appropriation of the natural commons is violent and against people, livelihoods, and cultures’ (Citation2021, p. 60). This was a powerful argument that resonated with many at home and abroad.

Even though the Sardar Sarovar was ultimately built – the dam was inaugurated in 2017 by Narendra Modi (Ranjan, Citation2018) – the jeevanshalas show that stopping its construction has not been the NBA’s only goal, nor has resistance been the movement’s only strategy. The first jeevanshala came into being as early as 1991 in the village of Chimalkhedi in Maharashtra, one of the first villages to be submerged by the rising waters caused by construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam. This school only lasted a year, as the area where it was set up was also submerged. A total of 12 jeevanshalas have opened since – in Manibeli (where the submerged school in Chimalkhedi moved in 1993), Danel, Thuwani, Sawaryadigar, Bhabri, Jeevan Nagar, Trishul, Shobhanagar and Tinismal in Maharashtra, and Kharya Bhadal, Bhitada and Jalsindhi in Madhya Pradesh. As of 2024, the NBA operates seven of these schools; four had closed, including those in Trishul and Tinismal in Maharashtra, as well as those in Bhitada and Jalsindhi in Madhya Pradesh, due primarily to the new government schools that opened in these areas, and one (Shobhanagar) has been handed over to the district panchayat (local government). There are approximately 100 students in each jeevanshala, for a total of about 700 students; at least 30 students are admitted to each jeevanshala every year; the schools aim for a 1:1 girls to boys ratio. The movement leaders report that approximately 6,000 students had graduated from jeevanshalas by 2024. Instruction takes place in both regional languages and indigenous dialects and much emphasis is placed on athletics and drama education. The schools employ approximately 40 support staff members from the local community and 40 teachers, who are brought together for training at least six times a year. In the past, the movement also sent some of the teachers for training and observation at experimental schools in the region that catered to rural and indigenous populations, including the Aksharnandan School in Pune and Grammangal in Dahanu. The jeevanshalas are financed by voluntary contributions to the NBA and do not receive any state support, even though they are making up for the lack of government education provision in the region (despite India’s policy of universal and compulsory education).

Many of the jeevanshalas were started as demand from local communities spread across the region through word-of-mouth. This was also the case in the resettled community of Jeevan Nagar, where the research behind this study took place. This community consists of displaced Adivasi families shifted from six original villages on the bank of the Narmada river. A jeevanshala was established in 2002 in Bharad, one of these villages, after a group of local residents visited the jeevanshala in Nimgavhan. One of the parents in the community focus group who was displaced from Bharad recalled this history: ‘There was a [government] school [in our village] but on paper only […] It was the first time in our whole life that we saw the school [jeevanshala] running, functioning’. As there was no school building, teaching the first batch of students took place in the village head’s house. A year later, local community members erected a simple bamboo structure using local materials; as one community member in the focus group commented, ‘Every person from the village came with a single bamboo stick’ to the construction site. When the villages were submerged in 2005, the displaced families insisted on the jeevanshala being relocated along with them, a demand that was granted by the government, which constructed a school building in Jeevan Nagar. Children from other nearby villages also study there today, linking the NBA with families and communities beyond the displaced Adivasi families. As one of the community members explained during the focus group, ‘because this school came, so activists started coming here […] School was a bridge to connect with the movement. And it helped us to resolve the issues of forest rights and many other local issues’. This is a pattern that repeated itself in other villages where jeevanshalas were built, which shows that, apart from providing education where the state failed to provide any, the schools have helped the NBA penetrate new territories and mobilise new communities.

The jeevanshala activist pedagogy

Although the NBA leaves the initiative for building the physical structures to the local communities, which consequently feel greater ownership over the schools, it exerts significant influence over the educational philosophy promoted by the jeevanshalas. Medha Patkar, an NBA leader who retained ties to the region even as she rose to national prominence, commented in an interview that formal education systems, both under British colonialism and since India gained independence, were ‘oriented towards the lifestyle which was going away from the natural eco-systems’. In contrast, the NBA sought to promote ‘the environmental vision, ecological vision’, one that ‘is to be necessarily rooted into the local resource system’. This is consistent with the NBA’s broader tenets of a neo-Gandhian environmentalism that focuses on locality, self-sufficiency and ecological balance (Chowdhury, Citation2014; Whitehead, Citation2007). The NBA’s leaders view activism as a key mechanism to bring about this vision. When asked what ‘activism’ means in the context of the jeevanshala, Medha Patkar commented:

Activism is not just resistance. Activism is in the struggle as well as reconstruction, regeneration, revival of many things that are getting lost otherwise, and rights-based approach towards transformation in any sector of the society […] We want the larger and larger section of the next generation to be not just career oriented or professional in the sense of without considering the ethical part of profession, only considering the commercial part of profession.

This holistic definition – which is at odds with much of the Western academic discourse on ‘environmental activism’ (McCalman, Citation2022) – suggests that jeevanshalas are not necessarily training grounds for resistance and civil disobedience but, rather, educational institutions that emphasise ethics and moral education. Yogini Khanolkar, an NBA activist involved in setting up and managing jeevanshalas, echoed this point:

It may not be that each and every person will become an activist and do that full time, as a military school, you know, they have their aims that we want to build a military, or we want to build what you say […] Naxalites [a Maoist group in India], it is not like that. In our school our aim is not making each and every child an activist but at least a good person, a person who wherever he will go will not cheat anybody, will not fraud, will keep in mind his culture, his village, who will respect his culture and love his culture.

School teachers interviewed in Jeevan Nagar also suggested that they did not have particular career trajectories in mind for their students. One teacher commented that a jeevanshala education is meant to be versatile and to allow ‘some students to join activism’ and others to ‘join the government by doing government jobs’. Some of the graduates have gone on to serve on the boards of local fishing cooperatives and the electricity board, while others have become jeevanshala teachers.

While these comments appear to suggest that the educational philosophy of jeevanshalas may be similar to other schools that emphasise character development and moral education, the demographics of jeevanshala students gives the education in these schools a particular focus, as Khanolkar explained:

Because all these schools are Adivasi schools, tribal schools and tribe is a deprived community, therefore just to teach them to write and read, and give exams with a particular syllabus is not enough, we think. Within that if [the student] wants to survive then he must have knowledge of his culture, what are his rights and what are the rights of his community and how to get those rights. So our focus is not only on giving that formal, stereotyped education but making them more aware about their practical life.

Indeed, the jeevanshalas’ emphasis on the Gandhian tradition of empowerment through self-sufficiency was evident during the fieldwork in Jeevan Nagar.

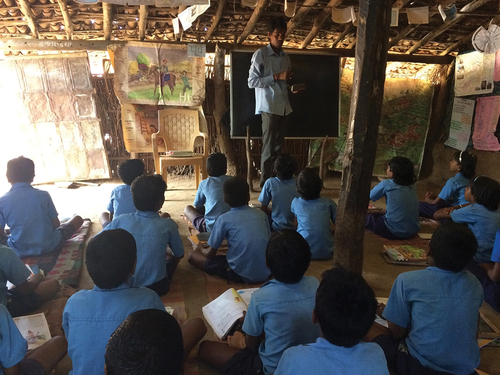

The jeevanshala in Jeevan Nagar is surrounded by fields and rolling hills (). It consists of two bamboo structures and a central courtyard that doubles as a playground. The bamboo structures are subdivided into classrooms, a dormitory and a canteen. Student drawings, photographs of past school events, and various visual aids and posters are arranged into colourful mosaics that line the walls (). On approaching the school, children can be heard singing and chanting, accompanied by the sound of drums.

The immersion of the campus in its natural surroundings mirrored the central role of the environment in how the teachers described their pedagogy. One of the educators remarked in an interview that ‘nature is our Adivasi home; dev [the giver] and danav [the taker] both reside in the forest’. Another teacher spelled out some of the activities the children engage in that are intended to facilitate environmental learning:

They learn how to do our own farming, how to cook food and collect wood from the forest. Not to cut healthy live branches, but those which have dried up and fallen down. They go in the forest on their own and collect wood, cook food, help the cook in the school, fill up water […] We tell them that they should not be ashamed to do their own work, because that is how we are going to be able to stand on our own feet and live our life.

Natural materials are also used in art lessons. In a class that took place on the first day of fieldwork, for example, students made sculptures using the soil that surrounded the school ().

The activist pedagogy of the jeevanshalas appears to do more than emphasise the injustice of displacement or the environmental destruction caused by the Sardar Sarovar Dam. It also historicises the relationship between the ousted Adivasis and the natural landscapes inhabited by their ancestors. One of the parents noted in an interview that the school teaches the students that ‘this river and forest is not the government’s, it is our property. We have to preserve it and we have to fight for it, to remain the owners of the forest and the river’. By emphasising the need to remain the stewards of the river and the forests, the school connects the Narmada struggle to a long and complex history of diminishing the Adivasis’ access to the natural environment, during both the colonial and postcolonial periods of India’s history. History – and particularly the aim of learning from the past – also plays a big role in the teachers’ approach to the topic of large dams. As one of the teachers put it, ‘there is no accountability on how many people have been displaced and sent off to slums. So we need to learn how to struggle against these things and we must learn about our rights so we don’t have to face the same loss again’.

Given the focus on the historical context of the Narmada struggle, it is not surprising that the teachers would not view ‘development’ as inherently desirable. When asked what he thought of this concept, one of the teachers explained:

To explain to children we would say that the construction of road is a sign of development, but it can also lead to destruction. To clear land to make road, they do destroy trees and plants in the forest, so that is destruction. For example, now with road, the people of other villages also have access to our forest and they are coming and taking timber from the forest, earlier that wood was only for our use. So it can lead to development as well as destruction.

This context-dependent understanding of development sets the jeevanshalas apart from the mainstream of India’s state education, where the idea of development is rarely questioned (Sarangapani, Citation2003; Vasavi, Citation2015).

Aside from historicising present social issues and contextualising the notion of development, the jeevanshalas put a lot of emphasis on the community and on acting in unison. This is reflected in the songs and slogans that form an integral part of the pedagogy (). Some key slogans were shared by the teachers in interviews and observed during lessons in Jeevan Nagar:

‘What is the aim of the Jeevanshala’? ‘Struggle and learning together’!

‘We are all together’!

‘Forest and land are whose’? ‘Ours, ours’!

Some of the slogans are used to build unity by de-emphasising the differences between groups of people. A prayer song ‘Where is Ram [a common Hindu name] and where is Rahim [a common Muslim name]? This nature is our life!’ is used to convey that religious differences do not matter in the Narmada struggle, and that there are no religious divides among the Adivasis. Some of the songs the children learn to sing in the jeevanshala are more overtly aligned with the NBA aims. For example, the song Wake Up BhilalaFootnote2 is, in the words of one teacher, ‘a call to the community to wake up, to see all the atrocities that are happening to us, to know our rights and to fight back. The song also says that, before the dam was built, the villagers were able to grow sorghum and pearl millet and fill their stomachs, but since the dam was built their fields have been under water.’ This and many of the other movement songs taught at the school are sung in Pavri and Bhilari, the local dialects, to emphasise that this is a struggle of the local people.

The commitment to locality – understanding and appreciating local histories – is also reflected in the role models the school spotlights for the students. These can be seen in the photographs and drawings of various political, spiritual and activist leaders that are posted on the wall of one classroom () – the Dalit leader B. R. Ambedkar, Baba Amte, a Gandhian social worker and supporter of leprosy patients who lived with the NBA for an extended period of time, as well as Adivasi freedom fighters like Tantya Bhil, Khaja Naik and Shirishkumar, who died in 1942 at the age of 16 in an altercation with the British during a pro-independence march in the nearby town of Nandurbar. One teacher remarked that these people are ‘hardly ever mentioned in the textbooks. We should teach the students about their contribution towards the nation’s freedom, and they also lost their lives fighting for the country, so we don’t forget about them’. This point echoed a statement by Medha Patkar, who commented during a conversation about why learning about local history was important: ‘Otherwise the convent students know who is Obama but not who is Ambedkar, they know who is Trump but not Tagore’. When asked why a photograph of Medha Patkar was not included on the wall, Yogini Khanolkar said that it was ‘because we don’t believe in that idolism and that single leadership’.

In addition to the pictures of Adivasi leaders, photographs of politicians such as Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi, both of whom advanced the cause of large dams, are prominently displayed in the classroom. When asked why they were included, Yogini Khanolkar explained that the movement stands against specific policies of the government rather than against the Indian nation ‘because this nation gave us the beautiful constitution compared to the other countries. We can say our constitution is beautiful in all aspects and in the whole diversity we have equality’. Khanolkar explained further that this is also why the school hoists two flags – the national flag alongside the NBA flag, which is always kept slightly lower than the national flag.

Despite this respect for the country and its constitution, the relationship between the jeevanshalas and the state is fraught with tension. Although the jeevanshala students are allowed to appear in government exams and thus to continue their education in government schools after passing through, the jeevanshalas are not formally recognised by government authorities. The community members in Jeevan Nagar recalled that the government, in fact, once attempted to close down the jeevanshala. A government officer came to the school and claimed it was illegal. ‘He even threatened our teachers, we had encircled the officer saying that it is our right to study, and we want to learn like all other children’, a local resident recalled. ‘We said we want to study in our Jeevan Shala itself. We held the officer for one whole day, the next day we held a rally also’.

An even tenser episode took place in 2006 in the jeevanshala in Danel. Due to the rising water levels behind the Sardar Sarovar Dam, the school was flooding. The students decided to remain inside the school, as Yogini Khanolkar recalled: ‘At that time we did not have to teach the students that you do it, you stand in the water; it was their own reaction, the reaction came out of the attachment to the school’. The children agreed to leave the structure only after the jeevanshala staff pleaded with them by promising that the fight for the school would go on. Subsequently, the students and the teachers prepared a list of demands for the government, which included building a new school. According to Khanolkar, the government fulfilled some of the demands. ‘They built a school with temporary sheds, which is not very hygienic but at least they did [it]. If we had not done this [demanded a new school], if we would have gone somewhere being afraid of government or police force, then we would not have achieved that’. This episode was not just an instance of activist mobilisation within the broader NBA struggle, but also a form of experiential learning for the children, as Khanolkar observed: ‘This has made some impact in their childhood and the thinking process and definitely when these children grew up and went everywhere, if something happens like that, so now they can share their own experiences with the outer world’.

An experiential pedagogy of resistance may not be part of the ‘official’ jeevanshala curriculum, but is nevertheless evidence of the schools’ engagement with the lived realities of the surrounding communities. Just as the bamboo walls of the jeevanshalas are permeable to air and light, the challenges facing the larger community enter the classroom in visceral ways, stimulating the children’s environmental imagination.

Student voices

It is beyond the scope of this study to determine to what extent the struggle to save the flooding school in Danel might be representative of wider patterns of politicisation of the young people attending these schools or, more broadly, what learning outcomes the students might achieve as a result of the jeevanshalaactivist pedagogy. However, the study did include an exploratory activity with children to learn about how they imagine the past and the future of their community, the aim being to identify activist narratives that influence the children’s perceptions. The activity entailed drawing pictures of the past (100 years ago) and the future (in 100 years’ time). This section of the article focuses on two pairs of pictures from the jeevanshala students that illustrate how two young people have navigated the upheaval of resettlement.Footnote3

The first pair of drawings (-past, -future) depicts a dramatic transformation from a habitable, even hospitable world to an apocalyptic vision of an uninhabitable future. A past in which fish, birds and trees jointly inhabit a landscape dominated by India’s national flag – indicating that such amity was once possible in India – gives way to a future in which all are drowned. Although submerged animals, plants and houses are usually not visible in the dams’ deep waters, the destruction is clear in this student’s drawing, which renders the many losses transparent. While these two drawings could be seen to communicate hopelessness about the future, they also point to a high degree of sensitisation to the interconnectedness of the human and the non-human, and an awareness of the long-term consequences of human actions.

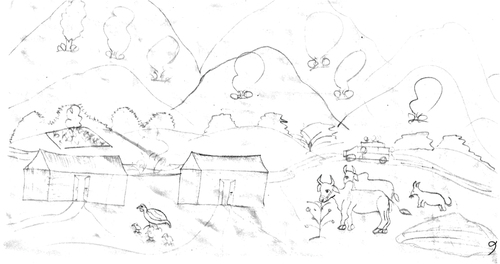

The second set of drawings (-past, -future) also shows dramatic change. It appears to be focussing more on the idea of urban development than on large dams. The landscape, dominated in the drawing of the imagined past by hills, trees and animals, turns into a ‘concrete jungle’ of densely packed tall buildings. The air pollution emanating from one of the buildings is prominent, and the birds in the sky are the only sign of biological life in this child’s vision of the future. While more habitable than the apocalyptic vision of , this vision nevertheless appears to suggest that development comes at the expense of the natural environment, which leaves little space for biodiversity and disconnects human beings from their natural surroundings.

These themes of an ‘idyllic’ past and uninhabitable and heavily denatured future appeared in virtually all the students’ drawings. While these depictions might be suggestive of a tendency to romanticise the past, they nevertheless reflect a sensitivity to environmental decay and to the changing relationship between humans and their natural surroundings. These depictions are consistent with how children elsewhere who are exposed to environmental decay register the acceleration of the slow violence (Nixon, Citation2011) against their communities and environments as an existential threat that could reach apocalyptic dimensions within their lifetimes (Sutoris, Citation2022a). However, the children in Jeevan Nagar – a village that had not been submerged by the dam – may not have been directly exposed to such environmental threats. It is, therefore, reasonable to hypothesise that the activist pedagogy and educational philosophy of the jeevanshala, as discussed in previous sections, may have contributed to – or at least did not get in the way of – the children developing an environmental imagination sensitive to anthropogenic environmental decay.

The prefigurative politics of jeevanshala as ‘infrastructural followup’

Cultivating such an imagination – and the associated politicisation of environmental learning – is indicative of an effort by the NBA to help mould a society in which there is no need for activists, to paraphrase the South African veteran activist leader Chris Albertyn (as quoted in Sutoris, Citation2022a).The jeevanshalas focus on empowering students to be political agents through experiential learning about social justice, self-sufficiency and connectedness to the natural environment inhabited by the Adivasis. They also aim to empower the Adivasis to protect their own rights, both by recognising their collective potential as political beings and by acquiring the cultural capital that comes with the academic skills gained through formal education. If such an educational effort is successful, there may not be a future role for the NBA in the region. In this respect, the jeevanshalas blur the line between activism and citizenship, suggesting that being an activist is not to be a ‘figure apart’ but simply to be a citizen.

The jeevanshala can be viewed as an example of ‘infrastructural followup’, which Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has called for as a prerequisite to meaningfully amplifying the political voices of the subaltern. In A Critique of Postcolonial Reason, Spivak refers to the need for ‘infrastructural followup’ (Citation1999, p. 419) in her discussion of the fate of the child workers who were dismissed from garment factories following Western campaigns to boycott products made using child labour. This concept resonates with Spivak’s reflections about efforts to ‘unmute’ the voices of the subaltern – a problem posed in her essay Can the Subaltern Speak? (Spivak, Citation2010) – in the context of human rights struggles. Spivak noted that ‘nothing achieved here will last when the engaged persons leave, as they necessarily must, unless there is maximal follow up’ (Citation2012, p. 131). In both cases, Spivak highlights the failures of activism to truly help the subaltern be heard, the often self-serving nature of activist agendas, and the unsustainability of activist interventions once the ‘engaged persons’ have left. The jeevanshala, despite its precarity, lack of institutional recognition and a hostile regulatory environment,reflects an awareness on the part of NBA activists of the kinds of pitfalls Spivak warns against, and their effort to follow up their activism with lasting change.

A rearticulation of the concept of the ‘social movement schools’ along the lines of Spivak’s ‘infrastructural followup’ parallels Yates’ (Citation2015) critique of prefigurative politics. A ‘social movement school’ designed to train movement agents can be seen as a space of prefiguration, traditionally defined as an effort ‘to create (or prefigure) utopic alternatives, though on a limited scale, in the present’ (Yates, Citation2015, p. 3), where the ‘means reflect the ends’ (p. 4). A model of a social movement school that aims to transform underlying patterns of oppression, and thus to limit the need for the social movement, is consistent with Yates’ proposed refinement in the conceptualisation of prefiguration, which he argues ‘necessarily combines the experimental creating of “alternatives” within either mobilisation-related or everyday activities, with attempts to ensure their future political relevance’ (Yates, Citation2015, p. 13). The jeevanshala pedagogy is an example of such hybrid politics, where the utopian meets the everyday in an effort to dismantle oppression through both resistance and empowerment.

Concluding reflections: implications for activism and education

This article has sketched out the contours of learning within a network of schools operated by a grassroots social movement in rural India, thereby illustrating the ways the schools advance the movement’s agendas and aid in its mobilisation. It has argued that the jeevanshalas are more an attempt to fill a gap in the state provision of education to the indigenous populations of the Narmada region than an ideological training ground for activists, and that they thus represent a type of social movement school that differs from definitions in the existing literature.

The NBA’s evolution to incorporate the jeevanshalas provides a model for social movements to adapt to changing external circumstances. In the face of adversity, the jeevanshalas have provided a new future-oriented focal point for the movement’s activism, thereby helping to generate hope and energising the movement’s activists. This illustrates the ways social movements might leave educational legacies and suggests that incorporating activist education into the work of movements might be an important mechanism for fostering long-term commitment among movement agents.

The jeevanshala model is also deeply relevant to ongoing conversations about the role of formal education in tackling climate change and the wider ecological breakdown in the Anthropocene (Sutoris, Citation2022a).Footnote4 The jeevanshalas’ focus on education as a social good, as well as on locality and collective political agency, is counter-cultural to the dominant global paradigms of the commercialisation of education (Ball, Citation2012), globalising curricula (Rappleye, Citation2012) and a depoliticised approach to environmental education that stresses individual over collective action (Komatsu et al., Citation2019; Maniates, Citation2001). While the jeevanshala approach to education may not be directly replicable – indeed, such an effort would go against the jeevanshala philosophy of localisation – it represents not merely an isolated experiment but a network of schools across multiple Indian states that has sustained itself for more than three decades. The lack of prior research into the jeevanshalas and the general scarcity of scholarship about experimental and activist schools reflects the Education field’s preoccupation with large-scale, state-run education systems. As this article has illustrated, jeevanshalas and other similar learning ‘experiments’ around the world are well worth studying.

When interviewed for this study, Medha Patkar concluded by saying, ‘And today again after all this materialism, market-ism, corporate-ism and all of that, humanity is also somewhere thinking about going back’. While a return to the past may not be possible – and the kind of idyllic past shown in the students’ drawings perhaps never existed – the jeevanshalas help their students ‘go back’ by understanding how the suffering of their community has come to be seen as an acceptable sacrifice for India’s economic development. Such an experiential ‘history of the present’ (Foucault, Citation1979) is, perhaps, what is needed more broadly in response to the environmental multi-crisis.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the community members, activists, teachers, parents and students who generously contributed their time and insight to this study, and would like to thank Tarini Manchanda for her help during fieldwork.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Peter Sutoris

Peter Sutoris is Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Climate and Development at the Sustainability Research Institute, School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds. He is the author of books Visions of Development (OUP, 2016) and Educating for the Anthropocene (MIT Press, 2022). His research focuses on imagination of environmental futures and activist pedagogies of change.

Notes

1. Given the time lag between the initial data collection and publication, several of the people interviewed reviewed a draft of this article in early 2023, and again prior to publication in April 2024 to update their earlier statements.

2. Bhilala refers to the local Adivasi communities living in Jeevan Nagar.

3. These drawings were chosen for their representativeness of the larger sample.

4. The word ‘Anthropocene’ is being used here to refer to the magnitude, complexity and unprecedented consequences of environmental change induced by human civilisations. It is not intended to imply either that responsibility for environmental decay is evenly distributed among all people nor that all people are affected equally.

References

- Aiello, G. (2020). Visual semiotics: Key concepts and new directions. In L. Pauwels & D. Mannay, eds. The SAGE handbook of visual research methods (pp. 367–380). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526417015.n23

- Ball, S. (2012). Global education Inc.: New policy networks and the neo-liberal imaginary. Routledge.

- Bose, P. S. (2004). Critics and experts, activists and academics: Intellectuals in the fight for social and ecological justice in the Narmada Valley, India. International Review of Social History, 49(S12), 133–157. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859004001671

- Choudry, A. (2015). Learning activism: The intellectual life of contemporary social movements. University of Toronto Press. https://utorontopress.com/9781442607903/learning-activism

- Chowdhury, A. R. (2014). ‘Repertoires of contention’ in movements against hydropower projects in India. Social Movement Studies, 13(3), 399–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2013.830564

- Crouzé, R., Godard, L., & Meurs, P. (2023). Learning democracy through activism: The global climate strike movement and Belgian youth’s democratic experience in times of environmental emergency. Social Movement Studies, 23(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2023.2184792

- Das Gupta, S. (2020). Indigeneity and violence: The Adivasi experience in eastern India. International Review of Sociology, 30(2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2020.1807862

- Dias, A. (2002). Development-induced displacement and its impact. In S. Tharakan (Ed.), The nowhere people: Responses to internally displaced persons (pp. 1–23). Books for Change.

- Driscoll, D. (2018). Beyond organizational ties: Foundations of persistent commitment in environmental activism. Social Movement Studies, 17(6), 697–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1519412

- Dwivedi, R. (1999). Displacement, risks and resistance: Local perceptions and actions in the Sardar Sarovar. Development and Change, 30(1), 43–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00107

- Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Penguin.

- Gadgil, M., & Guha, R. (1994). Ecological conflicts and the environmental movement in India. Development and Change, 25(1), 101–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.1994.tb00511.x

- Guha, R. (2007). Adivasis, naxalites and Indian democracy. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(32), 3305–3312.

- Guha, R., & Martinez-Alier, J. (1997). Varieties of environmentalism: Essays north and south. Earthscan.

- Hodson, D. (2014). Becoming part of the solution: learning about activism, learning through activism, learning from activism. In J. Bencze & S. Alsop (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (pp. 67–98). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4360-1_5

- Isaac, L. W., Jacobs, A. W., Kucinskas, J., & McGrath, A. R. (2020). Social movement schools: Sites for consciousness transformation, training, and prefigurative social development. Social Movement Studies, 19(2), 160–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2019.1631151

- Johnson, G. A., Pfister, A. E., & Vindrola‐Padros, C. (2012). Drawings, photos, and performances: Using visual methods with children. Visual Anthropology Review, 28(2), 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-7458.2012.01122.x

- Kahn, R. (2010). Critical pedagogy, ecoliteracy, & planetary crisis: The ecopedagogy movement. Peter Lang.

- Klingensmith, D. (2007). One valley and a thousand: Dams, nationalism, and development. Oxford University Press.

- Komatsu, H., Rappleye, J., & Silova, I. (2019). Culture and the independent self: Obstacles to environmental sustainability? Anthropocene, 26, 100198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2019.100198

- Leach, E. R. (1968). A runaway world?. Oxford University Press.

- LeCompte, M. D., & Schensul, J. J. (2013). Analysis and interpretation of ethnographic data: A mixed methods approach (2nd ed.). AltaMira Press.

- Litfin, K. (2016). Person/Planet politics: Contemplative pedagogies for a new earth. In S. Nicholson & S. Jinnah (Eds.), New earth politics: Essays from the anthropocene (pp. 115–134). The MIT Press.

- Lowan-Trudeau, G., & Niblett, B. (2017). Guest editorial: Activism and environmental education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 22, 5–10.

- Maitra, S. (2009). Development induced displacement: Issues of compensation and resettlement – experiences from the Narmada Valley and Sardar Sarovar Project. Japanese Journal of Political Science, 10(2), 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109909003491

- Mallick, K. (2021). Environmental movements of India: Chipko, narmada bachao andolan, navdanya. Amsterdam University Press.

- Maniates, M. F. (2001). Individualization: Plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world? Global Environmental Politics, 1(3), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1162/152638001316881395

- Martinez-Alier, J. (2012). The environmentalism of the poor: Its origins and spread. In J. R. McNeill, & E. S. Mauldin (eds.), A companion to global environmental history (pp. 513–529). John Wiley & Sons.

- McCalman, C. (2022). ‘A proper environmentalist wouldn’t do that’: Discourses of alienation from the environmental periphery. Social Movement Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2022.2054796

- Misiaszek, G. W. (2016). Ecopedagogy as an element of citizenship education: The dialectic of global/local spheres of citizenship and critical environmental pedagogies. International Review of Education, 62(5), 587–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-016-9587-0

- Modi, R. (2004). Sardar Sarovar oustees: Coping with displacement. Economic and Political Weekly, 39(11), 1123–1126.

- Niesz, T. (2019). Social movement knowledge and anthropology of education. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 50(2), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12286

- Nilsen, A. G. (2013). Against the current, from below: Resisting dispossession in the Narmada Valley, India. Journal of Poverty, 17(4), 460–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2013.804482

- Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press.

- Pahnke, A. (2018). From hostile skepticism to strategic utilization: How the Brazilian landless movement learned from repression to use legislation. Social Movement Studies, 17(2), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1428549

- Patwardhan, A. ( Director). (1995). Narmada Diary [Documentary].

- Prakash, M. S., & Esteva, G. (2008). Escaping education: Living as learning within grassroots cultures. Peter Lang.

- Ranjan, A. (2018). Anti-dam protests in India: Examining the profile of the Sardar Sarovar Dam. New Water Policy & Practice, 4(2), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.18278/nwpp.4.2.5

- Rappleye, J. (2012). Reimagining attraction and ‘borrowing’ in Education: Introducing a political production model. In G. Steiner-Khamsi & F. Waldow (Eds.), World yearbook of education 2012: Policy borrowing and lending in education (Vol. 2012, pp. 121–147). Routledge.

- Roy, A. (1999). The greater common good. India Book Distributors.

- Sarangapani, P. (2003). Constructing school knowledge: An ethnography of learning in an Indian village. Sage Publications.

- Spivak, G. C. (1999). A critique of postcolonial reason: Toward a history of the vanishing present. Harvard University Press.

- Spivak, G. C. (2010). Can the subaltern speak? Reflections on the history of an idea. ( R. C. Morris (Ed.). Columbia University Press.

- Spivak, G. C. (2012). An aesthetic education in the era of globalization. Harvard University Press.

- Sutoris, P. (2016). Visions of development: Films division of India and the imagination of progress, 1948-75. Oxford University Press.

- Sutoris, P. (2021). Environmental futures through Children’s eyes: Slow observational participatory videomaking and multi-sited ethnography. Visual Anthropology Review, 37(2), 310–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12240

- Sutoris, P. (2022a). Educating for the anthropocene: Schooling and activism in the face of slow violence. The MIT Press.

- Sutoris, P. (2022b). Slow violence, depoliticisation and hope: Cultural landscapes of schooling in Wentworth, South Africa. Ethnography, 146613812211302. https://doi.org/10.1177/14661381221130278

- van Maanen, J. (2011). Tales of the field: On writing ethnography (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Vasavi, A. R. (2015). Culture and life of government elementary schools. Economic and Political Weekly, 50(33), 36–50.

- Vora, R. (2009). The world’s first anti-dam movement: The mulshi satyagraha, 1920-1924. Permanent Black.

- Whitehead, J. (2007). Sunken voices: Adivasis, Neo-Gandhian Environmentalism and State—civil society relations in the Narmada Valley 1998-2001. Anthropologica, 49(2), 231–243.

- Yates, L. (2015). Rethinking prefiguration: Alternatives, micropolitics and goals in social movements. Social Movement Studies, 14(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2013.870883

- Zachariah, B. (2012). The ‘Nehruvian’ State, developmental imagination, nationalism, and the government. In R. Samaddar & S. K. Sen (Eds.), Political transition and development imperatives in india (pp. 53–85). Routledge.