ABSTRACT

This article advances Rodrik's political trilemma of the world economy by using insights from Polanyi’s The Great Transformation, which helps to grasp the interwoven dynamics of long-term transformations due to climate change and geopolitical reordering on one hand, and on the other short-term political ruptures due to countermovements. Rodrik's globalization trilemma shows the incompatibility of hyperglobalization with the need for an enlarged democratic policy space. Its nodes (globalization, nation state and democracy), however, have to be redefined to grasp contemporary dynamics of deglobalization. Based on a modified political trilemma of contemporary social-ecological transformation, I discuss and compare three visions and the resultant strategies: (1) Liberal globalism, focusing on hyperglobalization and individualism, (2) nationalistic capitalism, stressing national sovereignty and authoritarian governance, and (3) foundational economy based on planetary coexistence which combines selective economic deglobalization with a strengthening of a place-based foundational economy, and their respective social-ecological infrastructural configurations.

Introduction

Long before the Covid-19-crisis led to an abrupt interruption of logistics as well as travel, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, Citation2018, p. 1) had already alerted that ‘Limiting global warming to 1.5°C would require rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.’ It is in this specific conjuncture of contested neoliberalism and globalization that Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Polanyi [Citation1944/Citation2001], henceforth TGT) has spurred renewed interest.

This article analyzes different interpretations of the ongoing profound social-ecological transformations, especially the climate crisis. It contests one key assumption of different strands of progressive ‘reglobalization’, i.e. ‘The only plausible solutions are global ones, requiring a global response by actors operating via institutions at the global level’ (Bishop & Payne, Citation2020, p. 4), while at the same time problematizing a simplistic reduction of deglobalization to ‘rocky shores and false promises’ (Bishop & Payne, Citation2020, p. 17). My argument is that certain forms of economic deglobalization are already taking place (cf. Van Bergeijk, Citation2019), some are here to stay (eg. increased geopolitical rivalry), and that certain forms of economic deglobalization, like the downsizing, in part even dismantling, of globalized fossil-fuel infrastructures like airports, ports, container and road infrastructure has to be permanent if global warming is to be limited to 1.5°C.

Instead of limiting analysis to superficial and rather ephemeral phenomena like electoral surprises, be it Brexit or Trump, this article will relate these short-term phenomena to long-term processes. This broader framework will improve the evaluation of different contemporary strategies that aim at enabling ‘a good life for all within planetary boundaries’ (O’Neill et al., Citation2018), without succumbing to the temptation of easy solutions. Such a practical interest is best served by rigid conceptual ‘underlabouring’ (Bhaskar et al., Citation2018) to prepare the ground for a better understanding of the contemporary conjuncture and the necessary conditions for universalizing social well-being. Section two discusses Karl Polanyi's conceptualization of transformation in TGT. Section three describes the globalization trilemma which has been modified by Dani Rodrik himself over the years. Both explore the linkages between socioeconomic and political dynamics, giving key attention to spatial configurations. Section four confronts Polanyi's conceptualization of transformation and Rodrik's model of the world economy with contemporary debates on social-ecological transformations. Finally, section five integrates insights from Polanyi and Rodrik and elaborates the trilemma of contemporary social-ecological transformation as the base for competing visions and political strategies in times of deglobalization.

Karl Polanyi’s conceptualization of transformation

Karl Polanyi uses the term transformation with two different meanings, similar to Braudel’s (Citation1992) distinction between the longue durée and episodes: (1) Transformation as a metamorphosis, an evolutionary process of long-term change, and (2) transformation as a certain political-economic moment of radical rupture, a type of political revolution and short-term change which might accelerate ongoing profound transformations. The two conceptualizations rest on different temporalities: the first being an enduring phenomenon, a mainly socio-economic evolution, the second an abrupt rupture, a political revolution. The main thesis in TGT is: ‘In order to comprehend German fascism, we must revert to Ricardian England’ (TGT, p. 32). The short-term cannot be understood without the long-term. However, understanding the socio-economic conditions of the Industrial Revolution, following from David Ricardo's conceptualizations, had the openly political objective of influencing post-war development in the 1940s.

In TGT, Polanyi investigated the Industrial Revolution, which despite its name was an evolutionary process with a revolutionary outcome: a slow but profound transformation of modern civilizations, institutions, and routinized ways of living and working: from agrarian subsistence to rural exodus, urbanization and factory work. In this process, the emerging market society was based on the liberal utopia of globalizing self-regulating markets even for fictitious commodities like land, labour and money. Polanyi offers a beautiful metaphor: The ‘transformation to this system from the earlier economy is so complete that it resembles more the metamorphosis of the caterpillar than any alteration that can be expressed in terms of continuous growth and development’ (TGT, p. 44).

But although this long-term shift towards a market society is a profound transformation of working and living, it is not Polanyi's ‘great transformation’, a term only used twice in TGT – and it refers to a profound political change with lasting socioeconomic consequences. At the very beginning of the book, to be exact in its second sentence, Polanyi clarifies the objective of his oeuvre: ‘Nineteenth-century civilization has collapsed. This book is concerned with the political and economic origins of this event, as well as with the great transformation which it ushered in’ (TGT, p. 3). The second time ‘great transformation’ is mentioned in TGT is in a short sentence following the description of Britain abandoning the gold standard in 1931 and Roosevelt's New Deal from 1933 onwards: ‘Both were moves of adjustment of single countries in the great transformation’ (TGT, p. 236). In this quote, the ‘great transformation’ refers to the rapid collapse of an only apparently stable order and the beginning of a new era. According to Polanyi, the ‘conservative twenties’ (dominated by liberal capitalism) resulted in the collapse of liberal civilization and led to the ‘revolutionary thirties’ (that heralded the beginning of more organized forms of socio-economic organization).

Unlike ‘transformation,’ understood as the metamorphosis of the agricultural pre-market economy, the ‘great transformation’ relates to the profound anti-liberal and anti-globalist turn of the 1930s, with enduring consequences in the following decades. This politico-spatial turn resulted in the collapse of the League of Nations, of world trade and finance and, simultaneously, in the strengthening of territorialized and statist economic interventions. This great transformation was a consequence of liberal resistance to policy reforms that offered social protection. Large parts of the liberal-conservative mainstream of the 1920s identified socialism as the main threat, while sticking to a dysfunctional marriage of a market society with parliamentary democracy. Liberals as well as some social democrats (e.g. in Germany and the UK) tried, without success, to defend the gold standard and democracy. Instead of sustaining this inviable politico-economic order, fascism could reap ‘the advantages of those who help to kill that which is doomed to die’ (TGT 254) and become dominant in Central Europe. Fascism defended capitalism and destroyed the socialist movement – but also the global world economy, liberal democracy and an open society.Footnote1

Dani Rodrik’s globalization trilemma

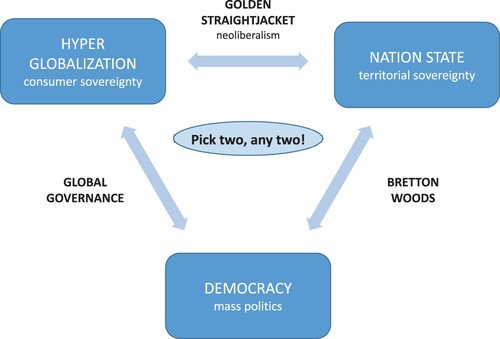

Dani Rodrik is an important mainstream economist who has been inspired by Polanyi's arguments on embeddedness (Rodrik, Citation2019).Footnote2 Already after a decade of rapid globalization following the fall of the Soviet Union, Rodrik discussed how far international economic integration might go. He starts with the standard trilemma of open-economy macroeconomics: ‘Countries cannot simultaneously maintain independent monetary policies, fixed exchange rates, and an open capital account’ (Rodrik, Citation2000, p. 180). As a consequence, policy-makers have to pick two of these three, sacrificing one. Hence, Rodrik proposes an ‘augmented trilemma’ that requires more fundamental political decisions. His ‘political trilemma of the world economy’, later called globalization trilemma, consists of three nodes which represent different normative principles for the world economic order today (cf. ): (i) hyperglobalization (originally called ‘integrated national economies’) avoids all interferences in consumer sovereignty and the global exchange of goods, services, or capital. Such a deep integration goes beyond eliminating tariffs, and has to eliminate all national regulations for goods, services and capital that hinder global exchange; (ii) national sovereignty as a territorialized form of self-determination that permits space for national economic policy-making and (iii) democracy (originally called ‘mass politics’) as a form of popular rule allowing citizens to shape their own destiny. According to Rodrik, one of these three normative principles must always be relinquished in order to pursue the remaining two (Rodrik, Citation2000, p. 181, Citation2011a, p. 201).

Figure 1. Rodrik’s globalization trilemma. Source: Own elaboration based on Rodrik (Citation2011b, p. 201).

Three options are thus possible. Historically, the first option was the ‘Golden Straightjacket’, imposed by the gold standard in the nineteenth century. This ‘first globalization’ before 1914 accommodated hyperglobalization and national sovereignty, but democracy was either non-existent or highly restricted. Transnational transactions flourished, property rights and contracts were respected. Nation states were sovereign, but according to Polanyi, this sovereignty ‘was a purely political term, for under unregulated foreign trade and the gold standard governments possessed no powers in respect to international economics’ (TGT, p. 261).

Historically, the second option was the ‘Bretton Woods compromise’ of the post-World-War II period (1945–1973), that aimed at a modest form of international integration diverging from hyperglobalization, while strengthening the nation state and democracy during the Cold War. GATT, together with capital controls as the cornerstone of the Bretton Woods system, promoted trade liberalization without undermining autonomous national policy space, enabling ‘countries to follow their own, possibly divergent paths of development’ (Rodrik, Citation2000, p. 183). Promoting free trade while simultaneously defending national policy space by capital controls and other measures, this international regime was even called ‘embedded liberalism’ (Ruggie, Citation1982).

Since the 1980s, hyperglobalization has again limited national spaces for maneuver, raising hopes of a new regime of global governance to diffuse liberal institutions beyond national power containers. In ‘Globalization Round II’ (Friedman, Citation2000, p. xvii), economic policy-making following the end of the Soviet Union has again become increasingly insulated from democratic decision-making: political choices are, according to apologists like Friedman, reduced to ‘Pepsi or Coke’, with no local options available.

Conceptually, there exists a third option: In 2000, Rodrik coined ‘global federalism’, based on a perfectly integrated world economy in which national borders are irrelevant for economic activities, as ‘transaction costs and tax differentials are minor. A world government would substitute national government’; he finished his article with a forecast:

If I were making a prediction for the next 20 years rather than 100, I would regard either one of these scenarios [referring to options one or two: author's comment] as more likely than global federalism. But a longer time horizon leaves room for greater optimism. (Citation2000, p. 185)

A critical appraisal of Polanyi’s conceptualization of transformation and Rodrik's globalization trilemma

This section looks at both contemporary ‘transformations’, i.e. the long-term ecological, geopolitical and socioeconomic dynamics shaping the twenty-first century, and the accompanying political struggles in the contemporary ‘great transformation’ of spatial and political reconfigurations. This includes a critique of contemporary Polanyian research on transformation as well as a revision of Rodrik's globalization trilemma.

An influential study on transformation as a profound and multidimensional change was a report from The German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU), entitled World in Transition: A Social Contract for Sustainability (WBGU, Citation2011), identifying similarities between past historical changes and current developments. According to WBGU, a ‘Great Transformation’ took place from the end of the eighteenth century onwards, in which ‘the economy has been extensively disembedded from its relation to society and life worlds’ (WBGU, Citation2011, p. 67). While conflating and confounding profound evolutionary changes with the ‘great transformation’, WBGU correctly describes the Industrial Revolution as an evolutionary process with revolutionary results (WBGU, Citation2011, 82), only comparable to one other deep civilizational change – the Neolithic Revolution (5000–10000 years ago). This transition, from hunter-gathering to agriculture, led to sedentariness, a more diversified division of labour, and biomass as the main energy source. According to WBGU, the transformation in the twenty-first century will once again be an epochal change, a metamorphosis: it will not consist simply of technological adaptations, while leaving modes of production, provisioning, societal routines and cultural practices unaffected. The report proposes profound changes across diverse fields, from global governance to land use. WBGU is silent, however, on the perils of global markets,Footnote3 structures of inequality, and the power of vested interests, especially oil, gas, automotive, and aviation, as well as hegemonic Western institutions. In the report, there is a systematic incoherence of apocalyptic predictions and trust in the institutional status quo (Brand et al., Citation2020, p. 165). The foundations of capitalist market economies are not questioned, thereby ignoring the destructive potential of the contemporary ‘imperial mode of living’ (Brand & Wissen, Citation2018), a mode of producing and living at the cost of other persons, regions, and generations. Living a good life within planetary boundaries would imply a ‘trans-form-ation’ in Polanyi's sense of long-term transformation. This means changing basic social forms, i.e. consumption norms, the profit and growth imperative, commodification, and the specific form of the state. This would have severe implications for provisioning systems, everyday routines, norms, and infrastructures (O’Neill et al., Citation2018). Therefore, it is contested in the short-term and will immediately lead to profound conflicts in the here and now. Vested interests, whether the fossil-fuel industry or finance capital, will defend the existing socio-economic order.

Therefore, the analysis of ongoing epochal change – especially the climate crisis and struggles for geopolitical hegemony – and the analysis of short-term political conflicts must go together. Brand et al. (Citation2019) correctly criticize WBGU as prototypical of a ‘new critical orthodoxy’ that does not question capitalist social forms. But even Brand et al. (Citation2019, p. 161ff.) erroneously postulate a ‘historical great transformation towards a ‘market society’ in the nineteenth century, and equate the social-ecological transformation that will take place during the twenty-first century with Polanyi's ‘great transformation’. This impedes grasping the full implications of the interplay of social-ecological changes and the contemporary short-term spatial-political conflicts. Similarly, Joseph Stiglitz (Citation1944/Citation2001, p. xii), in his foreword to the new edition of TGT, also conflates the two forms of transformation, exclusively focusing on the potential of progressive countermovements – turning Polanyi into ‘a theorist of counterhegemonic movements’ (Munck, Citation2002, p. 18). Recently, the potential of regressive countermovements has received increasing attention (Block & Somers, Citation2014; Dörre, Citation2019; Holmes, Citation2018; Novy et al., Citation2019). Rarely are short-term right-wing movements and long-term ecological and geopolitical challenges discussed together. Bridging this divide is a key objective of this article.

The current conjuncture is often described as dominated by right-wing politics in the form of neoliberal globalization. In analyzing neoliberalism, critical scholars share the conviction that it is a political project. Blyth denounces neoliberalism as ‘a warmed-over version’ of economic liberalism (Blyth, Citation2002, p. 126). For Harvey (Citation2005), it promotes class struggle from above, while Peck (Citation2013) focuses on the process of neoliberalizations, and Jessop (Citation2012) defines neoliberalism as a political project that ‘seeks to extend competitive market forces, consolidate a market-friendly constitution, and promote individual freedom.’ Mirowski (Citation2013, p. 40) identifies neoliberalism as a thought collective with a ‘set of proposals and programs to infuse, take over, and transform the strong state, in order to impose the ideal form of society, which they conceive to be in pursuit of their very curious icon of pure freedom.’ Mirowski's reading is close to Polanyi's reflections on fascism and liberalism. In two unpublished manuscripts written before TGT and entitled ‘the fascist virus’, Polanyi elaborated his argument that fascism is only the latest outburst of the anti-democratic virus that accompanies industrial capitalism (Polanyi, Citation1934/2005, p. 278) – and Western colonial endeavours, we should add. The fascist virus is the metaphysical conviction of the superiority of the propertied class (Polanyi, Citation1934/2005, p. 295). Fascism, therefore, according to Polanyi, is only the radicalized anti-democratic version of a lordly and supremacist mentality, based upon class societies as well as colonial, racial and sexist forms of domination. This supremacist spirit was constitutive of liberal individualism, present in Locke's theory of property, based on the right to appropriate indigenous land in the Americas (Arneil, Citation1996). Eminent Western thinkers, from Locke and Macaulay to Burke, were convinced that extending civic, political, and social rights to non-propertied classes contained a dangerous egalitarian logic (Dale & Desan, Citation2019; Mac Pherson, Citation1962);Footnote4 political democracy might endanger private property and liberal capitalism (Hayek, Citation1978), while abolishing empires might endanger Western civilization (Slobodian, Citation2018).

Cosmopolitanism, too, has always had an elitist leaning, including a spirit of white superiority. Even a pioneering liberal thinker like John Stuart Mill was highly contradictory. In some respects, such as female emancipation, Mill was culturally progressive. In others, he had much in common with Hayek, defending civic and minority rights while being sceptical about majority rule. He criticized the democratic ‘despotism of society over the individual’ (Mill, Citation1985, p. 73) and defended colonialism: ‘Despotism is a legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians’ (Mill, Citation1985, p. 69). Hayek shared Mill's elitist rejection of mass society and endorsed his plea for non-conformism and the ‘permission to differ’ (Mill, Citation1985, p. 66). For both, political tyranny is less threatening than the coercive power exercised by the state through democratically legitimated institutions.

My reading of neoliberalism is close to Polanyi's critical stance towards liberalism as an anti-egalitarian project, as it was developed in Vienna by Ludwig von Mises, mentor of Hayek. Mirowski elaborated on the systemic conformance between Carl Schmitt and Friedrich Hayek, of a Nazi-Führer cult and neoliberalism. Hayek's ‘political ‘solution' ended up resembling Schmitt's ‘total state' more than he could bring himself to admit < … > effectively advocating an authoritarian reactionary despotism as a replacement for classical liberalism’ (Mirowski, Citation2013, p. 85). While the applied methods of fascism and economic liberalism diverge profoundly, they share a supremacist and anti-egalitarian outlook, acknowledging necessary leadership by a selected few (Hayek, Citation1978, p. 45) – Hayek's ‘gardener’ of the market society (Hayek, Citation1944, p. 18) is state authority controlled by neoliberals. Based on the

double truth doctrine of neoliberalism … an elite would be tutored to understand the deliciously transgressive Schmittian necessity of repressing democracy, while the masses would be regaled with ripping tales of “rolling back the nanny state” and being set “free to choose”. (Mirowski, Citation2013, p. 86)

Neoliberal and right-wing politics not only constitute a reaction to geo-economic reordering, but also to the challenges posed by climate change – albeit in a paradoxical way. Ingolfur Blühdorn identifies a broad alliance to sustain a ‘politics of unsustainability’, legitimized by electoral majorities, including neoliberals and supremacists, that insist on non-interference with individual lifestyles. The ‘established economic order, patterns of resource exploitation, wealth distribution and lifestyles in Western(ised) consumer societies are profoundly unsustainable’ (Blühdorn, Citation2014, p. 147). Right-wing movements combat the environmental movement and are often fierce climate-change ‘deniers’ (Oreskes & Conway, Citation2011), while segments of Europe's population are willing to abandon the West's civilizational self-justification of promoting universal human dignity, preferring short-term gains in stabilizing their own imperial mode of living (Brand & Wissen, Citation2018).

Meanwhile, Dani Rodrik has over the years developed his trilemma further. He has clarified the distinction between different forms of globalization that aim at eliminating transaction costs in cross-border economic activities. The ‘first globalization’ was based on the gold standard and the military power of the British Empire, imposing legal isomorphism by means of imperial power. The hyperglobalization of recent decades has been a political project inspired by neoliberal globalists, brilliantly described by Quinn Slobodian (Citation2018). The global rule of property and contractual rights creates ‘One Big Market’ (TGT, p. 187) free of political interference by national and democratic institutions, but politically imposed and controlled by transnational investors. Deep integration annihilating non-tariff trade barriers has led to unprecedented levels of locational competition, commodification and financialization of housing, health, and nature. While not explicitly referring to these Polanyian concepts, Rodrik is aware of the disembedding dynamics of hyperglobalization.

Polanyi (Citation1945) was a fierce critic of ‘universal capitalism’, especially the dominance of ‘one big market’ rendered possible by the gold standard, and favoured regionalism, which (in the case of Eastern Europe) would have several advantages, including curing ‘intolerant nationalism, petty sovereignties and economic non-cooperation’. He trusted in a diversity of institutional settings – regionalized forms of mixed economies which would enable embedding market relations in systems of reciprocity and redistribution. His daughter could not agree more. Already in 1970, long before globalization became a popular term in the 1990s, Kari Polanyi Levitt (Levitt, Citation2002, p. 97) declared her position against globalization avant la lettre (in the 1970s still termed in a generic way ‘internationalism') in favour of self-reliant development: ‘It is becoming clear that the international corporations would find it profitable to impose on the world an “internationalism” which would break down all possible cultural, institutional and political barriers to their unlimited expansion’. Indeed, contemporary globalization has not only changed international rules, but also domestic policies: Liberalization, privatization and financialization have become an ‘engine of inequality and instability’ (Polanyi Levitt, Citation2013, p. 13).

Although Polanyi was aware of the impossibility of transferring ‘our troubles to another planet’ (TGT, p. 259), he was also aware of the socio-spatial foundations of individual flourishing – social freedom is relational, but also place-based. Even given the current threat to the eco-system, solely focusing on the ‘ontological facet of our shared existence’ to Earth as the ‘home planet of humanity’ (Pedersen, Citation2020, p. 1) would create deadlock, especially for collective agency. In a long, affirmative citation of Hawtrey, Polanyi insists that humans improve particular places, gradually and patiently building home and infrastructure. Hence, sovereignty is territorial in character. In 1944, he declared: ‘For a century these obvious truths were ridiculed’ (TGT, p. 239). Today political turmoil is again a response to the renewed failure of combining the liberal creed of economic hyperglobalization with broader socio-cultural cosmopolitan aspirations. To assume that struggling for competitive superiority with all means is compatible with international cooperation, effective climate policies and social cohesion is again turning out to be illusory.

But while Polanyi would probably have been skeptical of overcoming hyperglobalization by the ‘coming together of ordinary people’ to forge a ‘singular planetary community’ (Pedersen, Citation2020, p. 11), Polanyian research has a pro-globalization bias. For Burawoy (Citation2015, p. 24), a contemporary ‘countermovement will have to assume a global character, couched in terms of human rights’. Patomäki (Citation2014, p. 735) elaborates policy proposals for social protection against the market, arguing the ‘next synthesis must be globally orchestrated’. This is understandable, given according to Polanyi, ‘the new and tremendous hazards of planetary interdependence’ (Pearson et al., Citation1965, p. 181). But Polanyi was well aware that, during the nineteenth century, it was haute finance which built a ‘global’ liberal cosmopolitan order that denounced – in the words of Gentz, an Austrian diplomat supporting Metternich's repressive and reactionary politics in the 1820s – patriots as the new barbarians (TGT, p. 7). Even then, social conflict was camouflaged as a spatio-cultural conflict between civilized openness and provincial backwardness. We should not reproduce today these distorted views of social conflicts of an Austrian aristocrat at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Over the years, Rodrik too has taken a more realistic stance with respect to openness and the nation state, identifying the latter as the most effective container for policy space to shape socio-economic development. While nation states have been weakened over recent decades, predictions of their ‘hollowing out’ have been premature. For Rodrik, it is the territorial state that remains a crucial but underestimated node in the trilemma:

Let me begin by clarifying my terminology. The nation-state evokes connotations of nationalism. The emphasis in my discussion will be not on the ‘nation’ or ‘nationalism' part, but on the ‘state' part. In particular, I am interested in the state as a spatially demarcated jurisdictional entity. From this perspective, I view the nation as a consequence of a state, rather than the other way around. (Rodrik, Citation2017, p. 24)

Simply empowering national sovereignty has, however, several drawbacks, due to ‘societal multiplicity’ and the related coexistence of different socio-economic systems (Kurki & Rosenberg, Citation2020, p. 398). The exclusionary dynamics inherent in nationalism endanger minorities within a country as well as peace internationally (Hobsbawm, Citation1990). As national sovereignty in contemporary capitalism is often of inadequate scale, especially and foremost in Europe's Kleinstaaterei (small-statism), Polanyi (Citation1945) promoted ‘regional planning’ as an alternative to ‘universal capitalism’. In line with this reasoning, I propose entangled territorialized forms of self-determination as a cornerstone for planetary coexistence that empowers a diversity of mixed economies with a proper policy space – the city, region, nation and beyond. This would be crucial to fix social-ecological improvements in a particular place and to organize livelihoods in accordance with long-term social-ecological exigencies (TGT, p. 193).

Rodrik has further specified his understanding of democracy. A recent article written together with Sharun W. Mukand distinguishes between property rights, political rights, and civic rights. Mukand and Rodrik (Citation2020) identify two societal cleavages: between the elite and the masses, and between the majority and the minority. While liberal democracies have been able to protect all three types of rights in a context of low inequality and cultural homogeneity, electoral democracies tend to sacrifice civil rights, if minorities are socially and culturally different from mainstream society. This clarifies some contemporary political ruptures in countries like Turkey. Although Mukand and Rodrik's study clarifies the node ‘democracy/mass politics’ in the trilemma, its definition of democracy remains restricted to the political domain. Polanyi, however, had a broader understanding of democracy and freedom, extending to the democratization of the socio-economic domain via state regulations, cooperatives, or functional planning (Valderrama, Citation2019). With a dose of ingenuity, he even assumed that popular majorities could control parliaments and governments (Markantonatou & Dale, Citation2019).

For Polanyi, democracy must effectively strengthen co-responsibility for organizing ‘human livelihood’ (Polanyi, Citation1977, p. xxxxix), locally and at planetary scale. Taking responsibility implies acknowledging that living and working are never just private activities, but require collective decisions. This has to be done in a democratic manner. In Europe, the foundational economy providing essential goods and services to fulfil human needs was built in two stages. The material infrastructure of pipes and cables (water, gas, electricity), from the nineteenth century onwards, became an impressive equalizer of urban living standards (Foundational Economy Collective, Citation2018). After World War II, mass politics was extended to the socio-economic domain – civic and political rights were enriched by social rights in the national power container (Marshall, Citation1950). National welfare states delivered providential services like health, education and housing – an important step towards a socio-economic model enabling ‘freedom not only for the few, but for all’ (TGT, p. 265).

Under hyperglobalization, the foundational economy was again subordinated to the logic of capitalist markets. Foundational services and goods were privatized and financialized and, thereby, decisions concerning access and quality were restricted and insulated from the democratic process. The WTO as well as trade and investment agreements institutionalized a global order privileging property rights over democratic deliberation (Slobodian, Citation2018). Market-prone democracy limits policy space by privileging austerity over public investment (Streeck, Citation2016) and the foundational economy. Therefore, to tackle the drivers of the ongoing contemporary metamorphosis requires changing basic social forms, including the reorganization not only of the economy, but of democracy as well. Democracy will have to go beyond not only electoral democracy, but also market-prone and liberal democracy. It has to become more a process – socio-economic democratization – than an end state.

The political trilemma of social-ecological transformation

The strength of Polanyi’s TGT resides in analyzing long-term and short-term dynamics together. Today, as in the 1930s, profound changes in core institutions and routines are imminent: ‘The world as we know it is literally breaking down’ (Gills, Citation2020, p. 1). But there are similarities and differences between the catastrophes of the 1930s and today: (1) There is (as yet) no linear and comprehensive dynamic towards deglobalization. While soft globalization has continued in fields like culture, sport, science and tourism (pre-Covid-19), military and economic globalization have lost momentum (Olivié & Gracia, Citation2020). The value of exported goods as a share of global GDP reached an all-time high in 2008 (26.23%), but shrank over most of the following years (Livesey, Citation2018). Discontent with globalization rose in the Global North, while the population of the Global South seems to have embraced it (Horner et al., Citation2018). (2) The deglobalization of the 1930s and 1940s was violent, but brought an era of US hegemony as well as lasting social progress in the form of decolonialization and welfare states. The shift from UK to US hegemony was a geopolitical shift within the West – the current crisis of US-hegemony and the rise of China and Asia in general implies more profound changes, leading to acute social and political conflict and struggles for dominance (Van Bergeijk, Citation2019, p. 7). After 500 years, the dynamics of capitalist competition are for the first time changing the international division of labour and geopolitical hierarchies, to the detriment of the West. (3) Today's ecological crisis is of planetary dimensions, far exceeding the ‘dust bowls’ of 1930s US agriculture. Loss of biodiversity is dramatic, as is soil erosion; the climate crisis is accelerating (IPCC, Citation2018), and inequality in resource use soaring (Gough, Citation2017, p. chap. 3), potentially presaging unprecedented natural disasters (Farrell & Newman, Citation2020). (4) At the same time, a liberal worldview, criticized by Polanyi as incompatible with freedom for all in a complex society, is much more widespread today. Anti-discrimination policies have enlarged the freedom of minorities, oppressed and disadvantaged groups over the last decades – a huge civilizational progress. Large parts of the Left have, however, at the same time adhered to an individualist worldview and liberal value pluralism (‘I do not care how you live, and you must not interfere in my life’), often to the detriment of social freedom and collective agency. Liberal-value pluralism legitimizes consumer sovereignty and rejects societal responsibility for a common mode of living and working that is sustainable and inclusive. Therefore, it is horrified by its opponents – be it the new type of right-wing politics advocating political decisions which limit individual choice or a radical environmental movement propagating limits to growth.

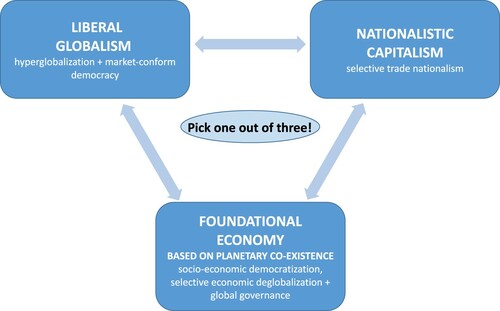

The profound long-term changes are again accompanied by a rather abrupt politically induced ‘great transformation’ of competing movements and countermovements. It is possible that the errors of the 1930s, when ‘<t>he victory of fascism was made practically unavoidable by the liberals’ obstruction of any reform involving planning, regulation, or control’ (TGT, p. 265), are being repeated. This need not and should not be the fate today – alternative strategies are possible. Rodrik's globalization trilemma offers insights for such strategies, but reconceptualizing it in the form of the Political Trilemma of Contemporary Social-Ecological Transformation exposes even better the dynamics resultant from the current crisis of globalization (cf. ). While Rodrik argues that one may pick two out of three, I identify in each strategy one key node and one normative principle, with secondary or no scope for the other two principles. In the contemporary conjuncture, we can identify (1) Liberal globalism that aims at fostering hyperglobalization by strengthening global governance and further hollowing out nation states. This strategy has been dominant over the last decades, while becoming increasingly challenged in recent years. (2) Nationalistic capitalism has emerged as a potential resolution of the current crisis of liberal globalism, as it is based on different degrees of anti-liberal, anti-enlightenment, and anti-democratic ideologies. Similarities to and differences from the fascist solutions of the ‘great transformation’ in the 1930/40s are of utmost interest. Going beyond the apparent clash of nationalism and globalism, as well as Rodrik's sympathy for a renewed Bretton-Woods system, I argue for (3) a strengthened foundational economy based on planetary coexistence to restrain hyperglobalization and avoid a civilization backlash comparable to the 1930s.Footnote5

Figure 2. Political trilemma of contemporary social-ecological transformation. Source: own conceptualization.

Liberal globalism

Key proponents of liberal globalism deny that a trilemma exists, assuming that hyperglobalization is compatible with individual flourishing, vivid liberal democracies, and strong nation states. EU institutions sympathize with liberal globalism, promoting a world order led by the West. In 2015, the SDGs (sustainable development goals) as well as the COP-21 Paris agreement were signed by nearly all national governments. The success of these treaties, however, has remained limited under conditions of fierce economic competition and geopolitical rivalry. Effective global governance with binding treaties has so far been limited to economic affairs, with the WTO as well as investment protection (including ISDS, the notorious state dispute settlement system) as key pillars. Liberalized financial markets have facilitated global transactions, subsidized fossil-fuel transport systems have cheapened logistics, and mobility and global production networks have been dominated by large corporations. Furthermore, supranational legislation as well as legalized tax avoidance structures (e.g. tax havens) have empowered global investors, leading to commodification and financialization even in the foundational economy and in hitherto public domains like health, education, and housing. Decades of increasing the range of individual freedoms have gone hand in hand with increasing inequalities (Piketty, Citation2014).

Liberal globalism is cosmopolitan, fiercely combatting nationalism and all forms of limits and borders. But its elitist, Western and class-based bias results in a neglect of societal, often territorialized, responsibilities concerning the well-being of ordinary people. It assumes that individuals can take direct responsibility for global affairs, from human rights to the climate crisis. It supports voluntary self-organization, but restrains national policy space whenever it threatens individual freedoms, from property rights to lifestyle choices. Liberal globalism provides the legal framework for producers to choose their business model and consumers to choose products and services. State agency is framed as, at best, paternalistic, and, at worst, unacceptable interference in the personal domain, whether it be a tax on certain products, parking restrictions in cities, or limits on air travel – all of which would be decisive policies for decarbonization.

Politics should abstain from further interventions and value judgements on specific modes of producing, working, and living. Consumer sovereignty is not only endorsed by neoliberal free marketeers, but is perceived as a means of emancipation. This underestimates how strong consumption and behavioural patterns have always been influenced by a given ‘choice architecture’ (Gough, Citation2017, p. 158). The available range of options is severely biased, as consumer preferences are ‘constrained by corporate power, system lock-in, and the interaction between the two’ (Galbraith, Citation1970; Gough, Citation2017, p. 160). Furthermore, cosmopolitans of all ideological shades tend to have the highest ecological footprint and hardly question causes of inequality and uneven development. But liberal globalism is not simply a class project of increasing commodification to favour the rich. Limiting or even prohibiting private consumption patterns has been rejected not only by elites, but also by ordinary people, hindering or even impeding collective forms of provisioning. Blühdorn identifies a broad alliance to sustain a ‘politics of unsustainability’, legitimized by electoral majorities. The ‘established economic order, patterns of resource exploitation, wealth distribution and lifestyles in Western(ised) consumer societies are profoundly unsustainable’ (Blühdorn, Citation2014, p. 147). However, public institutions that might restrain commodification have lost administrative efficacy due to liberalization and privatization – they are increasingly unable to provide well-being for citizens. This delegitimizes not only liberal globalism, but the West in general – its routines, values, economic and political models are perhaps under even more pronounced threat than in the 1930s, when Western dominance was unchallenged.

Polanyi criticized the liberal illusion ‘to assume a society shaped by man’s will and wish alone’ which ‘is the result of a market view of society which equated economics with contractual relationships and contractual relationships with freedom’ (TGT, p. 266). Analyzing the cataclysm of market societies in the 1930s, Polanyi was convinced that within a framework of ‘One Big Market’, with universal money facilitating the exchange of everything, democracy could not be sustained (Scheiring, Citation2016). Today again, selective restrictions on finance, trade and investment – especially restraining financial markets by means of capital controls and abandoning a legal framework that privileges privatization and capital globally (Pistor, Citation2019) – are a prerequisite for flourishing foundational economies and democracy. By adhering to hyperglobalization and neglecting the need for social protection by means of a foundational economy, liberal globalism paves the way for anti-liberal and anti-globalization countermovements – some more reactionary, others more progressive.

Nationalistic capitalism

Neoliberals have genuinely been globalists, but aware that a world without borders is impossible: ‘The normative neoliberal world is not a borderless market without states but a doubled world kept safe from mass demands for social justice and redistributive equality by the guardians of the economic constitution’ (Slobodian, Citation2018, p. 16). Already in the nineteenth century, the ‘Golden Straitjacket’, dominated by haute finance – like contemporary globalization, dominated by global financial markets and multinational corporations – was precursor of a spatial shift towards ‘deglobalization’ as a countermovement against openness (Van Bergeijk, Citation2019).

Nationalistic capitalism is a populist and reactionary form of countermovement against the destruction of ‘habitation’, framed as a loss of cultural identity (Holmes, Citation2018). While liberal with respect to economic values, socio-culturally this new Right has been overtly reactionary in challenging humanitarian values. Instead of problematizing increasing inequality and the loss of social protection, it has acquired an anti-systemic image by contesting certain tenets of enlightened and liberal societies: religious fundamentalism challenging Darwinism, free marketeers doubting climate change, heads of state implementing controlled and illiberal democracies and tolerating racism and sexism. Although neoliberal policies have long excluded the poor by means of economic power, moralizing poverty and blaming victims (Levitas, Citation1996), reactionary discourse has long reinforced the cleavage between the ‘West’ and the ‘rest’ (Said, Citation1978/Citation1995), constructing a highly differentiated and antagonistic ‘us’ against an essentialized ‘other’; this open adherence to anti-enlightenment values signals a civilizational rupture. Trump, Bolsonaro, Orbán and others insist on their own supremacy and make a huge effort to polarize, create scapegoats and prepare for cultural warfare. Their policies aim at deepening socio-spatial hierarchies by culturalizing politics and radicalizing policies of discrimination, exclusion and repression. They undermine respect for human dignity and pillars of liberal societies, like ‘moral freedom and independence of mind’ (Bugra, Citation2018, p. 88) as well as systematically ignoring scientific expertise from climate change to Covid-19.

Nationalistic capitalism capitalizes on the failures of globalism and promises to resist pressure for structural change (Blühdorn, Citation2014, p. 157), especially that resulting from global competition and the need for deep social-ecological changes. This apparently anti-systemic countermovement wages a cultural war against ‘foreign’ and new modes of living. That is why the car, patriarchal relations, ethnic homogeneity, and anti-veganism have attained such a pre-eminent symbolic place in right-wing identity politics. They offer imaginaries of habitation, socio-cultural protection against the apparently uncontrolled changes induced by globalization (Holmes, Citation2018). Reactionary politics, which is sometimes denounced as even ‘denying’ climate change, seems to be well aware of the ongoing profound transformation and its accompanying multiple upheavals, acknowledging ‘that prevalent norms and patterns of self-determination and self-realization can be sustained for only some sections of society and have to be accompanied by equivalent restrictions for others’ (Blühdorn, Citation2014, p. 159). This is a key difference to liberal globalism and its – at least rhetorical – aspiration to universalize human rights. For nationalistic capitalism, ‘the politics of unsustainability is crucially about the management of – or societal resilience and adaptation to – increasing social injustice, marginalization and exclusion’ (Blühdorn, Citation2014, p. 159). The radicalization of right-wing politics ‘solves’ the problem of scarcity by sustaining the good life only for the selected few.

Nationalistic capitalism is increasingly hostile to supranational economic institutions like the WTO and trade and investment treaties, as well as EU bureaucracy. Proponents criticize globalization, especially in the form of migration, multiculturalism, and ‘unfair’ competition, always eroding liberal democracy, especially the rule of law, the free press, minority rights, and the defense of countervailing powers. Assessing that under ‘fair’ conditions their ‘superiority’ will prevail, they do not question key pillars of global capitalism like markets and property rights. It combines dominium, domination via private property rights, and imperium, domination via political force – a hybrid model that is difficult to imagine for neoliberal globalists (Slobodian, Citation2018), but is in line with an imperialist understanding of international relations. To effectively defend the dominance of the West and the capitalist market order, important dominant groups ally tactically with proponents of nationalistic capitalism, whether neoliberal segments, Christian fundamentalists and the Republican Party in the US, or the military, agribusiness and Christian fundamentalists in Brazil. Brazil is probably the best example of these reactionary and patriotic alliances against human rights and climate policies, but fiercely supportive of capitalist institutions. In line with Locke’s liberalism, Bolsonaro opens indigenous land to agribusiness, promoting assimilation to Western civilization as the fate of indigenous communities. Nationalistic capitalism, hostile to liberal open-mindedness, but sympathetic to the elitist and supremacist leanings of liberalism is – sometimes openly, but in general implicitly – concerned with defending the prevailing world economic hierarchy and its own mode of living – if necessary, by avoiding a fair economic and political playing field. Electoral democracy, in place even in Putin’s Russia, is selectively instrumentalized for exclusionary policies. Political leaders, most evidently in the EU in Hungary and Poland, have obtained control of local business, captured state bureaucracies and undermined the rule of law (Gerőcs & Szanyi, Citation2019). Others try to follow. By disempowering countervailing powers and the opposition, an anti-egalitarian authoritarianism is emerging.

Foundational economy based on planetary coexistence

Neither liberal globalists nor proponents of nationalistic capitalism put long-term social-ecological transformation at centre stage. As a consequence their short-term strategies – either combating or promoting ‘globalization’ – remain flawed, as the ongoing contemporary metamorphosis is not a simple spatial turn that leaves the market society unaffected, but a profound social-ecological and a politico-economic change. To shape these changes in a cooperative and inclusive way, democracy will have to go beyond market-prone liberal democracy. Socioeconomic democratization is the process of changing the basic functioning of the economy in a democratic way, prioritizing the provisioning of foundational goods and services. Needs should be satisfied with less tradeable commodities, overcoming the growth imperative and consumerism inherent in a hyperglobalized economy. In my understanding, strengthening the foundational economy on a basis of planetary coexistence offers the most coherent strategy to deal with these challenges.

The Foundational Economy Collective (Citation2018) distinguishes different zones of economic activities: Producing and consuming cars and computers differs from the collective provisioning of water, health, food, and education. Therefore, different sectoral and spatial zones of the economy have to be dealt with by context-sensible policies. The foundational economy is based on a value judgement in line with Polanyi's quest for ‘freedom in a complex society’ (TGT, p. 265): The only sustainable modes of living are those that can be universalized’, enabling freedom for more than the selected few, i.e. private swimming pools and private gardens for all are illusionary, but municipal swimming pools and public parks are possible. Such a Polanyian vision prioritizes equality as a basic form of democracy – in short, ‘freedom for all’ (Brie & Thomasberger, Citation2018).

The foundational economy satisfies basic needs like physical health and autonomy, preconditions for effective participation in social life (Barbera & Jones, Citation2020; Gough, Citation2017). But these universal needs are satisfied by context-specific forms of needs satisfaction in which collective provisioning trumps individual consumption. Social-ecological infrastructural configurations are collective forms of needs satisfaction that combine artifacts (material infrastructures, like utilities for gas and water, schools and hospitals) and the respective regulations for their provisioning, access and use (like property and citizen rights) (Bärnthaler et al., Citationforthcoming). Infrastructural configurations are multi-scalar, ranging from municipal material and providential infrastructures to national health and rent regulation to global treaties on human rights and climate mitigation. Infrastructural configurations as crucial satisfiers differ spatially. Leading a dignified and civilized everyday life is not the same in Britain, Greece or Rwanda. The concrete form of infrastructures and their regulations have to be created and decided ‘from the bottom up’ in a participatory manner. Neither local actors alone, nor civil society by itself can offer such collective provision independent of public authorities, especially municipalities.

However, hyperglobalization has subsumed the foundational economy to the same uniform logic of the neoliberalized tradeable sector. Spreading commodification and financialization in hitherto protected zones like health and education have been a key factor in popular discontent with the current form of globalization. Popular support for alternatives to liberal and nationalistic forms of capitalism can be enhanced by better access to secure and good-quality provisioning of basic goods and services. A foundational approach favours common, public and regionalized provisioning of basic goods and a shift away from privatized consumption. Breaking the dominance of ‘one big market’ for financial transactions by means of capital control has implications for accumulation strategies. Corporations lose part of their bargaining power with respect to labour and public authorities, as it complicates exit strategies. This favours more coordinated and ‘greener’ forms of capitalism (Gough, Citation2017, p. 200ff.).

In capitalism, the tradeable sector with private corporations transacting on a globalized market is the dominant economic zone. The greening of this sector via strategies of green growth has remained the dominant environmental policy objective, even given empirical evidence that green growth is no viable option (Hickel & Kallis, Citation2020). Environmental policies continue focusing on efficiency, technology and pricing (Haberl et al., Citation2020, p. 31) without questioning basic capitalist institutions. A recent comprehensive comparison of national economies (Cahen-Fourot, Citation2020, p. 14f.) shows that socially inclusive and coordinated forms of capitalism are more sensible to environmental concerns as well. ‘Material security seems to be associated with more support for environmental policies’ and ‘social cohesion is strongly correlated with climate-friendly stances’. However, those nations with committed environmental policies and strong welfare regimes are at the same time more open economies that offshore their environmental impact. Financialization and globalization of production ‘enabled them to temporarily stabilize at the domestic scale the tensions arising from improvement in living conditions favoring both the conditions for ecology-prone socio-political stances and an environmentally harmful way of life.’ Even more egalitarian and ecology-prone countries remain trapped in the contradictions of growth and expansion-addicted capitalism. To effectively tackle the social-ecological challenges they have to change basic forms of living and working. This will not be possible without downsizing their global impact due to their excessive economic openness and to reorganize their mode of living towards the collective provisioning of foundational goods and services. Sufficiency has to trump efficiency.

The foundational approach has strong popular appeal, as it promises short-term egalitarian policies that improve the quality of life ‘for all’, from the collective provisioning of good-quality public transport, energy systems and public providential services of excellence like care and housing (Engelen et al., Citation2017). In the long run, relying less on the commodified and resource-intensive satisfaction of individual wants provided by the world market will have strong positive social-ecological effects – waste will be reduced and equality increased.

In line with Aristotle (Nussbaum, Citation2006; Sen, Citation1999), humans are caring, social and political beings, related to one another. A flourishing foundational economy needs a proper policy space, requiring a spatial framework of planetary coexistence that enlarges spaces for maneuver in diverse forms and at different scales. Humans are at home in their respective localities, embedded in contextualized socio-economic relations, and a proper territorial political order. Given this existential socio-spatial entanglement, there are huge challenges for a democratic social-ecological transformation: (1) To obtain popular support, participatory and democratic forms of governance have to be extended beyond the political domain to the democratization of broader socio-economic domains, especially the workplace and welfare institutions. Broad debates on context-specific infrastructural configurations have to lead to collective decisions: Should care be offered in more or less centralized, more or less professionalized forms? Which forms of mobility should be encouraged and which restricted? (2) However, democracy is more than common deliberation. Its legitimacy depends on delivering results – offering better prospects for a good life. The urgency of ongoing ecological changes has to make certain environmentally harmful choices become unavailable (e.g. FCKW, plastic bottles, or unrestricted air travel). Effective democratic institutions have to limit the destructive potential of opponents to collectively binding changes, whether they be liberal globalists insisting on unrestricted consumer sovereignty or adherents to nationalistic capitalism pushing for authoritarian and exclusionary measures to sustain the status quo. Democracy, as a rule of majorities, has to set levels for ‘conformity which is needed for the survival of the group’ (TGT, p. 267) – but this must go hand in hand with ‘strengthening the rights of the individual in society’ (TGT, p. 264), a challenging task of striking a balance.

Current ‘choice architectures’ (Gough, Citation2017, p. 158) of the resource-intensive and growth-oriented status quo, framed as consumer sovereignty to optimize individual wants satisfaction, has to be substituted by alternative, more sustainable and equitable choice architectures, which offer plural forms of collective provisioning favouring the satisfaction of basic needs as well as climate change mitigation. Unplanned, in 2020 public policies imposing severe restraints on choice and individual preferences have been very quickly implemented to combat the Covid-19 pandemic. Choice architectures that enable climate-friendly living could be created as well – if there were a corresponding sense of urgency. To implement adequate social-ecological infrastructural configurations will, however, encounter fierce resistance not only from dominant and vested interests (Geels, Citation2014; Hausknost & Haas, Citation2019), but also from ordinary people, the working and middle classes (Blühdorn, Citation2019); stopping subsidies for the car industry and its extensive fossil-fuel infrastructure will generate opposition not only from the automotive industry and its trade unions, but from committed drivers and ordinary citizens accustomed to or dependent on the car. To foster regional and organic agricultural systems, agro-business and its trade unions as well as some retail interests and customers will also resist changes to nutritional habits. The success or failure of a peaceful and inclusive social-ecological transformation will depend on the outcome of struggles over the form of and access to provisioning systems; such struggles will be facilitated by a clear commitment to compensate losers and to prioritize foundational services and goods like health, education and a life-friendly climate ‘for all’. Therefore, a commitment to combat wealth concentration and luxury consumption is a decisive component of successful foundational strategies.

Nationalistic capitalism fosters deglobalization via trade and currency wars and military aggression. This is not, however, the only possible path towards deglobalization. Also helpful would be to reduce concentration of economic and political power (Bello, Citation2013, p. 268ff) and overcome unsustainable models of individualized consumption of tradeable goods. Further steps towards economic deglobalization as well as policies for strengthening cooperation-oriented forms of globalization have to be combined to offer a dignified life to all inhabitants of the planet. What Novy (Citation2017) calls ‘emancipatory economic deglobalization’ is at the same time a form of ‘reglobalization’ (Bishop & Payne, Citation2020), as both concepts acknowledge the merits of the Bretton Woods system that combined ‘multilaterialism’ with ‘domestic interventionism’ (Ruggie, Citation1982, p. 393). While Bishop and Payne insist on a simplistic spatial preference for globalization, my proposed approach acknowledges the respective strengths and weaknesses in a more balanced way. Indeed, a multi-scalar strategy towards planetary coexistence takes responsibility for the global commons and intensifies international political cooperation in those domains with a high risk of lose-lose situations, like climate, biodiversity, human rights or unrestrained financial markets. However, planetary coexistence is more than nation-centered multilateralism, being open to innovative models of governance that empower civil society organizations as well as local and regional actors. It aims at enlarging policy space at multiple scales, e.g. by taxing wealth and luxury consumption, re-negotiating or abandoning bilateral trade and investment treaties, dissolving tax havens, regulating and restraining the markets for digital platforms, dismantling fossil-fuel infrastructures, extending IMF Special Drawing Rights, and promoting global redistribution, e.g. in the form of a Global Green Deal (Newell & Taylor, Citation2020; UNCTAD, Citation2019).

To sum up, multi-scalar strategies to increase territorialized policy space ‘from below’ need not limit, but might even support planetary responsibility. National wealth taxation can reduce global inequality and weaken plutocratic power. Restricting quasi monopolistic delivery systems like Amazon or AliBaba and supporting local retailing can help to strengthen the repair economy and dismantle fossil-fuel-driven global logistics. Urban citizenship can strengthen residents’ rights independent of nationality and passport. ‘Grounded’ in neighbourhood, city and region, sustainable and affordable infrastructures might contribute to a resilient planet (Engelen et al., Citation2017).

Conclusions

This article has distinguished two types of transformation discussed in Polanyi's TGT, and analysed entanglements of long-term and short-term dynamics. Short-term hegemonic struggles and the rise of a new type of nationalistic capitalism take place under conditions of long-term social-ecological transformation, a contested liberal creed of universalizing markets and geopolitical shifts. In this sense, we are witnessing a new ‘great transformation’, with short-term political upheavals generated by the exhaustion of neoliberal globalization. The rise of nationalistic capitalism is a reaction not only to the failure of liberal globalism, but also contemporary transformations. It potentially accelerates ongoing long-term social-ecological and geopolitical transformations, leading to a new, more deglobalized socio-economic order.

The current ‘great transformation’ is again a contested spatial shift, but incompatible with simplistic spatialized solutions. As the political trilemma of contemporary social-ecological transformation shows, neither embracing nor condemning ‘globalization’ leads to feasible strategies. However, nationalistic capitalism profits from the severe shortcomings of liberal globalism, especially its denial of the trilemma, its elitist leanings, and illusory trust in individualistic solutions. Viable alternatives to nationalistic capitalism have to offer alternatives to liberal globalism as well.

Covid-19 has helped justify selective economic deglobalization as a necessity for sovereign policy-making, due to the shortcomings of global supply chains. Downsizing global mass tourism would be conducive to decarbonization. Economic deglobalization in specific sectors and specific world regions is here to stay, leading to more or less inclusive, more or less authoritarian and sustainable solutions: A shift towards protective agricultural and industrial policies might support the foundational economy or, alternatively, serve as justification for nationalistic neo-mercantilist competition.

Strengthening the foundational economy from a planetary co-existence footing builds place-based social-ecological infrastructural configurations, empowers people as well as local business, but also promotes a common planetary consciousness. It is a strategy of ‘empowerment without hubris’ (Block, Citation2018, p. 170), combining a radical vision with a gradual strategy. Success is not guaranteed – a sustainable foundational economy that offers access to essential goods and services for all residents combined with planetary coexistence and international cooperation might not result in the required political decisions for a peaceful social-ecological transformation. It is, though, the only strategy with the potential to concretize the Polanyian vision of equal freedom for all, place-based as well as embedded in a resilient planet.

Acknowledgment

The argument of this article has been substantially improved due to feedback from Richard Bärnthaler, Joachim Becker, Michael Brie, Ingolfur Blühdorn, Julia Fankhauser, Leonhard Plank, Kari Polanyi-Levitt, Werner Raza, Mikael Stigendal, Alexandra Strickner, three anonymous referees, the editors of the journal and John Billingsley for proof-reading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andreas Novy

Andreas Novy is associate professor and head of the Institute for Multi-Level Governance and Development at the Department of Socioeconomics at WU Vienna. In 2019, he received, together with Brigitte Aulenbacher, Richard Bärnthaler and Veronika Heimerl, the Kurt-Rothschild-Award for his work on Karl Polanyi. He has been head of the Austrian Green Foundation, co-founder of the Viennese Paulo Freire Center and co-organizer of two Good Life for all-Congresses in Vienna. His most recent publications include Local social innovation to combat poverty and exclusion: a critical appraisal (co-eds. S. Oosterlynck and Y. Kazepov (2020, Polity Press), Kari Polanyi: Die Finanzialisierung der Welt. Karl Polanyi und die neoliberale Transformation der Weltwirtschaft (2020, Beltz Verlag; co-eds. M. Brie and C. Thomasberger; German translation of From the Great Transformation to the Great Financialisation), Karl Polanyi: Wiederentdeckung eines Jahrhundertdenkers (2020, Falter, co-eds. B. Aulenbacher, M. Marterbauer and A. Thurnher) and Zukunftsfähiges Wirtschaften (Future-fit Economics) (2020, Beltz Verlag, together with R. Bärnthaler and V. Heimerl).

Notes

1 Already in 1934, Polanyi had defined fascism as ‘this form of revolutionary solution that leaves capitalism unaffected’ (Polanyi, Citation1934/2005, p. 236).

2 Others have been the Nobel Prize laureates Douglas North and Joseph Stiglitz.

3 It even proposes further market instruments, like emissions trading (WBGU, Citation2011).

4 Lord Macaulay, a modernizer in charge of introducing English in Indian schools, was convinced that if majority rule determines government, ‘either civilization or liberty must perish’ (Polanyi, Citation1934/2005).

5 Coexistence was the name of a journal which Karl Polanyi and his wife Ilona Duszinskaya founded in the 1960s to counter the Cold War.

References

- Arneil, B. (1996). John Locke and America. The defence of English colonialism. OUP.

- Barbera, F., & Jones, I. R. (Eds.). (2020). The foundational economy and citizenship. Comparative perspectives on civil repair. Policy Press.

- Bärnthaler, R., Novy, A., & Stadelmann, B. (2020). A Polanyi-inspired perspective on social-ecological transformations of cities. Journal of Urban Affairs. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2020.1834404

- Bello, W. (2013). Capitalism's last stand?: Deglobalization in the age of austerity. Zed Books.

- Bhaskar, R., Danermark, B., & Price, l. (2018). Interdisciplinarity and wellbeing. A critical realist general theory of interdisciplinarity. Routledge.

- Bishop, M. L., & Payne, A. (2020). The political economies of different globalizations: Theorizing reglobalization. Globalizations, 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1779963

- Block, F. (2018). Karl Polanyi and human freedom. In M. Brie & C. Thomasberger (Eds.), Karl Polanyi's vision of a socialist transformation (pp. 168–184). Black Roses.

- Block, F., & Somers, M. (2014). The power of market fundamentalism. Karl Polanyi's critique. Harvard University Press.

- Blühdorn, I. (2014). Post-ecologist governmentality: Post-democracy, post-politics and the politics of unsustainability. In J. Wilson & E. Swyngedouw (Eds.), The post-political and its discontents. Spaces of depolitication, spectres of radical politics (pp. 146–166). Edingburgh University Press.

- Blühdorn, I. (2019). The legitimation crisis of democracy: Emancipatory politics, the environmental state and the glass ceiling to socio-ecological transformation. Environmental Politics, 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1681867

- Blyth, M. (2002). Great transformations. Economic ideas and institutional change in the twentieth century. Cambridge University Press.

- Brand, U., Görg, C., & Wissen, M. (2019). Contested social-ecological transformation. Shortcomings of current debates and Polanyian perspectives. In R. Atzmüller, B. Aulenbacher, U. Brand, K. Fischer, & B. Sauer (Eds.), Capitalism in transformation. Movement and countermovements in the 21st century (pp. 184–197). Edward Elgar.

- Brand, U., Görg, C., & Wissen, M. (2020). Overcoming neoliberal globalization: Social-ecological transformation from a Polanyian perspective and beyond. Globalizations, 17(1), 161–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2019.1644708

- Brand, U., & Wissen, M. (2018). The limits to capitalist nature: Theorizing and overcoming the imperial mode of living. Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Braudel, F. (1992). Civilization and capitalism, 15th-18th century. The perspective of the world (Vol. 3). University of California Press. (Original work published 1979)

- Brie, M., & Thomasberger, C. (Eds.). (2018). Karl Polanyi's vision of a socialist transformation. Black Rose Books.

- Bugra, A. (2018). Revisiting “freedom in a complex society”: A view from the periphery. In M. Brie & C. Thomasberger (Eds.), Karl Polanyi's vision of a socialist transformation (pp. 77–90). Black Rose: Montreal.

- Burawoy, M. (2015). Facing an unequal world. Current Sociology, 63(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392114564091

- Cahen-Fourot, L. (2020). Contemporary capitalisms and their social relation to the environment. Ecological Economics, 172, 106634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106634

- Dale, G., & Desan, M. (2019). FASCISM. In G. Dale, C. Holmes, & M. Markantonatou (Eds.), Karl Polanyi's political and economic thought (pp. 151–170). Agenda Publishing.

- Dörre, K. (2019). Take back control!. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 44(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-019-00340-9

- Engelen, E., Froud, J., Johal, S., Salento, A., & Williams, K. (2017). The grounded city: From competitivity to the foundational economy. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(3), 407–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx016

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2020, March 16). Will the coronavirus end globalization as we know it? Foreign Affairs.

- Foundational Economy Collective. (2018). Foundational economy. The infrastructure of everyday life. Manchester University Press.

- Friedman, T. L. (2000). The Lexus and the olive tree: Understanding globalization. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Galbraith, J. K. (1970). Economics as a system of belief. The American Economic Review, 60(2), 469–478.

- Geels, F. (2014). Regime resistance against low-carbon transitions: Introducing politics and power into the multi-level perspective. Theory, Culture and Society, 31(5), 21–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414531627

- Gerőcs, T., & Szanyi, M. (Eds.). (2019). Market liberalism and economic patriotism in the capitalist world-system. Palgrave macmillan.

- Gills, B. (2020). Deep restoration: From the great implosion to the great awakening. Globalizations, 1–3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1748364

- Gough, I. (2017). Heat, greed and human need. Climate change, capitalism and sustainable wellbeing. Edward Elgar.

- Haberl, H., Wiedenhofer, D., Virág, D., Kalt, G., Plank, B., Brockway, P., Fishman, T., Hausknost, D., Krausmann, F., Leon-Gruchalski, B., Mayer, A., Pichler, M., Schaffartzik, A., Sousa, T., Streeck, J., & Creutzig, F. (2020). A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: Synthesizing the insights. Environmental Research Letters, 15(6), 065003. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

- Hausknost, D., & Haas, W. (2019). The politics of selection: Towards a transformative model of environmental innovation. Sustainability, 11(2), 506. http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/2/506 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020506

- Hayek, F. A. (1944). The road to serfdom. Routledge.

- Hayek, F. A. (1978). The constitution of liberty. University of Chicago Press.

- Hickel, J., & Kallis, G. (2020). Is green growth possible? New Political Economy, 25(4), 469–486. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964

- Hobsbawm, E. (1990). Nations and nationalism since 1780. Programme, myth, reality. Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

- Holmes, C. (2018). Polanyi in times of populism: Vision and contradiction in the history of economic ideas. Routledge.

- Horner, R., Schindler, S., Haberly, D., & Aoyama, Y. (2018). Globalisation, uneven development and the North–South ‘big switch’. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx026

- IPCC. (2018). Summary for policymakers of IPCC special report on global warming of 1.5(C approved by governments [Press release].

- Jessop, B. (2012). Neoliberalism. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), Wiley-Blackwell encyclopedia of globalization. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470670590.wbeog422

- Kurki, M., & Rosenberg, J. (2020). Multiplicity: A new common ground for international theory? Globalizations, 17(3), 397–403. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1717771

- Levitas, R. (1996). The concept of social exclusion and the new Durkheimian hegemony. Critical Social Policy, 16(46), 5–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/026101839601604601

- Levitt, K. (2002). Silent surrender: The multinational corporation in Canada (Vol. 196). McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP.

- Livesey, F. (2018). Commentary unpacking the possibilities of deglobalisation. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 177–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx030

- Mac Pherson, C. B. (1962). The political theory of possessive individualism: Hobbes to Locke. Clarendon Press.

- Markantonatou, M., & Dale, G. (2019). THE STATE. In M. Markantonatou, G. Dale, & C. Holmes (Eds.), Karl Polanyi's political and economic thought (pp. 49–68). Agenda Publishing.

- Marshall, T. H. (1950). Citizenship and social class (Vol. 11). Cambridge University Press.

- Mill, J. S. (1985). On liberty. Penguin Books.

- Mirowski, P. (2013). Never let a serious crisis go to waste: How neoliberalism survived the financial meltdown. Verso.

- Mukand, S. W., & Rodrik, D. (2020). The political economy of liberal democracy. The Economic Journal, 130(627), 765–792. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueaa004

- Munck, R. (2002). Globalization and democracy: A New “great transformation”? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 581(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000271620258100103

- Newell, P., & Taylor, O. (2020). Fiddling while the planet burns? COP25 in perspective. Globalizations, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1726127

- Novy, A. (2017). Emancipatory economic deglobalisation: A Polanyian perspective | Desglobalização econômica emancipatória: Uma perspectiva a partir de Polanyi. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Regionais e Urbanos, 19(3), 554–575. http://rbeur.anpur.org.br/rbeur/article/view/5555 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22296/2317-1529.2017v19n3p554

- Novy, A., Bärnthaler, R., & Stadelmann, B. (2019). Navigating between improvement and habitation: Countermovements in housing and urban infrastructure in Vienna. In R. Atzmüller, B. Aulenbacher, U. Brand, F. Décieux, K. Fischer, & B. Sauer (Eds.), Capitalism in transformation. Movement and countermovements in the 21st century (pp. 228–244). Edward Elgar.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2006). Poverty and human functioning: Capabilities as fundamental entitlements. In D. B. Grusky, & R. Kanbur (Eds.), Poverty and inequality (pp. 47–76). Stanford University Press.

- Olivié, I., & Gracia, M. (2020). Is this the end of globalization (as we know it)? Globalizations, 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1716923

- O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F., & Steinberger, J. (2018). A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability, 1(2), 88–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4

- Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2011). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Patomäki, H. (2014). On the dialectics of global governance in the twenty-first century: A Polanyian double movement? Globalizations, 11(5), 733–750. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2014.981079