ABSTRACT

Unfree labour has been central to the Indian tea industry’s ‘business model’ since its establishment under British colonial rule. In this paper, we investigate forms of unfree labour in south Indian tea plantations based on a mixed methods study. Conceptualizing unfree labour in a multi-dimensional way our analysis brings to the fore how economic and social coercions that work on tea workers’ desire to guarantee their household’s daily and generational reproduction enable companies to control workers’ time, that way facilitating profit making in the global tea industry. Gender ideologies and hierarchies normalize these coercions for women workers. They translate into gendered obstacles to exit plantation employment and lead to long working hours for low pay. At the same time, we show that the desire of women and men to secure their families’ present and future livelihood also triggers and fuels unfree workers’ resistance.

1. Introduction

Policy debates about corporations’ accountability throughout their supply chain reflect a rising international concern about coerced forms of labour in the global South. The global tea value chain that provides consumers with the second-most popular drink after water has largely remained invisible in these debates about contemporary forms of unfree labour, though.

Unfreedom among tea plantation labourers has persisted in the Indian tea industry’s ‘business model’ since its establishment under British colonial rule (Bhowmik, Citation2011; Gupta, Citation1992; LeBaron, Citation2018; Mishra et al., Citation2011; Ravi Raman, Citation2002). We understand unfree labour relations under contemporary capitalism as springing from the marriage of contracts and – economic, social, and physical – coercions (Hahamovitch, Citation2017, p. 238). McGrath’s (Citation2013) concept of multidimensional unfreedom captures such diverse dimensions along which workers’ freedom might be restricted. Precluding the exit from the employment relation, unfree labour is associated with harsh, degrading, and dangerous conditions of work and the violation of workers’ rights (Phillips, Citation2013, pp. 177–179).

This article’s focus on south India addresses the contrast between the paucity of contemporary scholarly work on coerced labour in the region’s tea plantations and its significance for tea production and trade. While in-depth studies exist on unfree labour in the tea plantations of West Bengal (e.g. Bhowmik, Citation2011) and Assam (e.g. Mishra et al., Citation2011), less has been written about tea plantations in the south (with LeBaron’s, Citation2018 report presenting some findings on Kerala alongside Assam). This lack of attention diverges from the region’s role in making India the fourth exporter of the ‘green gold’ globally. Whereas, in 2020, 18 per cent of the tea made in India originated from southern states (Tea Board of India, Citation2021), tea exports from the region actually exceed those from north India (Neilson & Pritchard, Citation2016, p. 37).

This study investigates the ways in which social reproduction and gender shape not only the unfreedom of south Indian tea plantation workers, but also their resistance. We understand social reproduction as ‘[…] the material social practices through which people reproduce themselves on a daily and generational basis and through which the social bases and material relations of capitalism are renewed’ (Katz, Citation2001, p. 709). Reflecting Mezzadri’s (Citation2019) work on how reproductive realms subsidize surplus extraction, to date, social reproduction has clearly shaped plantation workers’ unfreedom through Indian tea companies’ heavy reliance on workers’ households for recruitment and workers’ dependence on plantation owners for housing and other facilities. This has enabled tea companies to achieve the improbable combination of employing a captive labour force at low cost amidst labour shortage (Besky, Citation2017; Bhowmik, Citation2011). Yet, historically, studies of unfree labour in Indian tea plantations have focussed on the role of economic coercion associated with indebtedness and physical punishment in preventing workers’ exit from employment and in labour control, more broadly (e.g. Baak, Citation1999; Gupta, Citation1992) – neglecting to look at accommodation and workers’ reproduction more broadly.

The ways in which the braiding of productive and reproductive realms catalyse capital accumulation in the Indian tea sector are imbued with gender-related social pressures. Intertwined with ethnic and caste hierarchies, gender hierarchies have contributed to the justification of workers’ dependency and the exploitative working conditions that plantation workers endure to date (Bhowmik, Citation2011). We conceptualize this role of gender through Kurian and Jayawardena’s (Citation2017) lens of ‘plantation patriarchy’ that positions women under male domination both in fieldwork and within the household.

We also trace how social reproduction and gender relate to unfree labourers’ resistance in south India’s tea value chain. This is significant in the context of a widespread conceptual separation of unfree labour and agency (McGrath, Citation2013, p. 1009; McGrath & Strauss, Citation2015, p. 303) as well as against the backdrop of feminist political economists’ foregrounding of how reproductive realms are subordinated to capitalist exploitation rather than on the levers they offer for resistance.

We develop our argument in six steps. In the next section, we conceptualize the relationship between unfree labour, social reproduction, and gender as well as unfree workers’ resistance. We present the mixed data sources that our paper ties together to investigate reproduction and resistance in unfree labour relations in section 3. Subsequently, we identify gendered meanings of the compulsion to provide overtime work and find that the need and desire to regenerate the household biologically and generationally prevents workers’ exit from estate employment (section 4). Foregrounding the 2015 strike in a tea estate in Kerala, section 5 presents ways in which women tea plantation workers resist and investigates the types of power resources that these workers mobilized. In a final step, we relate our results to dynamics in the wider tea value chain and discuss how they speak to conceptual discussions of unfree labour and resistance.

2. Understanding coercion and agency in unfree labour

Frameworks that seek to address coerced labour relations in the global economy are often limited by their binary understandings of labour un/freedom and victimhood/agency as well as by their focus on the realm of production. In this section, we outline alternative conceptualisations that inform the analysis presented in sections 4 and 5.

2.1. Social reproduction and gender in unfree labour

While different in several important ways, liberal as well as many Marxist accounts of unfree labour agree on a clear delineation between free and unfree labour with the latter relegated to pre-capitalist modes of production. Marxist theory assumes wage labour under capitalism to be ‘free’ in a double sense of the term: dispossessed from the means of production and ready to sell her or his labour (e.g. Brass & Bernstein, Citation1992). Laconically summarizing that ‘[t]he worker is therefore ‘free to starve’ if [s]he does not enter into a ‘free’ labor contract’, Rioux et al. (Citation2020, p. 713) bring to the fore that such Marxian free labour goes hand in hand with economic compulsions. Extra-economic coercion and politico-legal constraints, in contrast, are considered incompatible with capitalism as a system of free labour from both liberal and many Marxist perspectives (Rioux et al., Citation2020, p. 716).

Building on insights from labour history that ‘[…] reveal that in the past, the dividing line between chattel slaves, serfs, and other unfree subalterns taken together and “free” wage earners was rather vague at best’ (van der Linden, Citation2012, p. 64), however, new interdisciplinary streams of theory have sprung from the persistence of coerced forms of labour amidst neoliberal capitalism. Such critical studies of unfree labour reject binary understandings of unfree labour as they ‘[…] may render situations falling outside the category as inherently unproblematic, normalising “lesser” exploitation and abuse’ (McGrath, Citation2013, p. 1009). Instead, McGrath (Citation2013) proposes a multi-dimensional approach that separates such social, legal and but also economic restrictions of workers’ freedoms on the one hand from the consequences of these unfreedoms in the form of degrading working and living conditions on the other hand. This accounts for ‘the many legal and social fetters’ imposed on ‘free’ individuals (O’Connell Davidson, Citation2010, p. 245), including ideologies of nationalism, racism and sexism as ‘everyday’ forms of discrimination harnessed to justify coercive consequences (Fudge, Citation2019, p. 115).

This understanding of labour unfreedom captures the role of economic and social coercions in the governance of south Indian tea plantation labour. Migrants belonging to marginalized communities have provided the bulk of labour in south India’s tea plantations. For the early plantations, Adivasis or tribal communities who were violently detached from their communal property cleared for tea cultivation formed a major source of labour supply (Ravi Raman, Citation2002, p. 10). Later, the threat of eviction based on colonial tax policies added agricultural tenants primarily from what is now Tamil Nadu ‘[…] to the ranks of the landless agricultural labourers ready to be recruited to the plantations’ (Ravi Raman, Citation2002, p. 12). With caste hierarchy coinciding with economic power, this mainly affected Dalits and other lower caste people who laboured on lands owned by caste-Hindus (Ravi Raman, Citation2002, pp. 10–12). While the geographical reach of recruitment has increased with the recent mobilization of migrant labour from India’s east and northeast, the dominance of Adivasi and lower caste communities among the plantation labour force persists (Labour Bureau, Citation2009, p. 19; Lalitha et al., Citation2013, pp. 35–36; Raj, Citation2019, p. 679).

Multidimensional approaches acknowledge that compulsions in the realms of social reproduction can constitute a source of unfreedom and that the domestic sphere can be a space where the degrading effects of coercions are played out (e.g. Fudge, Citation2019; McGrath, Citation2013). By denoting reproductive work as ‘wageless work’, Mezzadri (Citation2020, p. 157) directly relates it to unfree labour. The braiding of productive and reproductive realms extends labour control – for instance, where housing is embedded in the workspace like in Indian tea plantations. Besides, the reproduction of the labour force through housework and other forms of unpaid work mostly performed by women provides a subsidy to capital (Mezzadri, Citation2019, p. 38). These mechanisms demonstrate that coercions implicit in the gendered responsibility assigned for social reproduction are deeply intertwined with accumulation (Mezzadri, Citation2016, p. 1881).

These processes have been relevant for accumulation in the Indian tea industry. Family-based recruitment of the early plantation labour force ensured that labour could be reproduced and lowered labour costs (Bhowmik, Citation2011, p. 240; Sen, Citation2004, p. 90). Gupta’s (Citation1992, p. 184) observation that fixing of wages below-subsistence levels was the basic mechanism compelling whole families to work in the tea plantations of colonial Assam remains relevant throughout the tea sector in contemporary India. To date, the presence of plantation labourers’ unemployed or casually employed family members places employers in an advantageous position in wage negotiations. Bhowmik (Citation2011, p. 247) points out that they can threaten to compensate wage raises by a reduction in the number of casual workers. As a result, present-day wage rates – even the comparatively high daily rate in Kerala – have remained far below an adequate level (e.g. Bhowmik, Citation2015, p. 29; LeBaron, Citation2018, p. 20; Siegmann et al., Citation2019, p. 77).

The concept of ‘plantation patriarchy’ (Kurian & Jayawardena, Citation2017) foregrounds the role of gender in its integrated analysis of workers’ productive and reproductive conditions. This contrasts with most historical analyses of plantation labour in South Asia, which do not unpack how class and gender intersect in the enclave economy of the plantation. The lack of spatial separation between work in the field and in the household has allowed for highly intensive forms of patriarchal control (Kurian & Jayawardena, Citation2014, p. 7). In Sri Lankan tea plantations where colonial legacies of ‘slave-like’ practices persist, such controls were justified and normalized by ‘[…] gender prejudices and patriarchal norms stemming from colonialism, race, caste, ethnicity, religion and culture’ (Kurian, Citation2018, p. 13). As a result, women ‘[…] are treated much like children in need of paternal control and guidance, which comes from male supervisors at work, and male kin at home’ (Philips, Citation2003, p. 21). Patriarchal controls historically included women workers’ exposure to physical violence, the payment of lower wages and longer working hours than their male counterparts. Shouldering the main responsibility for the reproductive chores in the household, they were simultaneously being denied equal access to education, health and other welfare services and being excluded from political leadership (Kurian, Citation2018, p. 13). ‘Such plantation patriarchy was directly linked to the profitability of production, and it was in the interests of those in power to sustain norms and practices that promoted the low status and therefore the lesser entitlements for women workers’ (Kurian, Citation2018, pp. 13–14). This is also true for the cases we examine (see also Raj, Citation2019, p. 673). Since the establishment of tea plantations, the labour-intensive, repetitive tea leaf harvest has been largely assigned to women, while men are generally given work seen as requiring ‘physical exertion’, such as the maintenance and upkeep of the estate (Ravi Raman, Citation2002, p. 14). Justified on the grounds of women’s ‘nimble fingers’ and men’s greater physical strength (Jayawardena & Kurian, Citation2015, p. 41; Sen, Citation2004, p. 90), this gender division of labour persists to date, with tea factory work, too, being dominated by men.

We deploy these conceptual insights to inform our empirical investigation of the role of social production in shaping unfree labour in section 4.

2.2. Understanding workers’ resistance amidst unfreedom and reproduction

Mullings (Citation2021) challenges feminist accounts that frame women’s disproportionate involvement in social reproductive work solely through the lens of their subordination within male-centred systems of exploitation. Her re-reading of ‘life’s works’ of Caribbean communities from the eighteenth century to the present brings to the fore how practices of social reproduction have provided sources of resistance to people in situations of extreme precarity. More cautiously, Mezzadri (Citation2016) reminds us that the interconnection of production and reproduction – being ‘“managed” by multiple masters at once’ (Mezzadri, Citation2016, p. 1892) – implies that women’s labour struggles also involve reproduction.

South Indian tea plantations reflect this ambiguous role of social reproduction for tea plantation workers’ unfreedoms. As outlined above, the need and desire to regenerate the household biologically and generationally ties workers to estate employment. At the same time, early strikes in south Indian tea plantations triggered by the denial of workers’ basic right to food (Ravi Raman, Citation2002, pp. 35–36) exemplify that the dependence on employers for their families’ sustenance also nurtures expectations – expectations that may serve as a launching pad for workers’ resistance (Sen & Majumder, Citation2011, p. 31).

A set of lenses framed as ‘power resources approach’ (Schmalz et al., Citation2018) have become influential in analysing – and strategizing – such resistance, including the engagement with unfree workers’ agency (McGrath & Strauss, Citation2015). This approach builds on Wright (Citation2000, p. 962) who distinguished structural power that springs from workers’ location within the economic system – be it at the workplace or the wider labour market – from associational power as the resources provided by workers’ collective organizations.

Wright’s framework was differentiated and enriched by other scholars. Unpacking the black box of associational power, Lévesque and Murray (Citation2010) perceive cohesive collective identities as a key component of worker organizations’ internal solidarity. While recognizing that the hypermobility of capital in neoliberal capitalism has weakened workers’ structural power both at work and in the marketplace, Silver (Citation2003, pp. 13–15) also highlights that, simultaneously, relatively small groups of workers hold great disruptive power in the context of globalized production networks. Webster et al. (Citation2008, p. 12) denote this with logistical power which: ‘[…] blocks roads and lines of communication, and crashes internet servers.’ Chun’s work complements these power resources with the notion of workers’ symbolic leverage. It refers to ‘[…] the ways in which structurally marginal groups of workers invoke notions of collective morality to cultivate a ‘positional advantage’ over more powerful social actors and institutions’ (Chun, Citation2008, p. 446).

In section 5, we read south Indian tea plantation workers’ resistance through the lens of the power resources approach.

3. Tying together mixed threads of data

The empirical analysis presented in sections 4 and 5 ties together threads of survey and interview data from a study of South Asian tea plantations with secondary sources, especially on the 2015 strike of women workers in tea plantation in Kerala.

The study on working conditions and collective agency of tea plantation workers in India and Sri Lanka commissioned by an international certifying agency was coordinated by the first author (Siegmann et al., Citation2020). While it was conducted in 2016 in the two south Indian states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, as well as in Assam and Sri Lanka, this article zooms in on the data generated in the five participating estates in south India.

The mixed methods study combined a worker survey with qualitative interviews with workers, management, and other actors. On each estate, focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with separate groups of men and women workers. As part of the certifying agency’s concern for core labour rights, both the survey and the FGD items addressed forced labour. Besides, the research instruments covered topics such as wages, labour and living conditions, and workers’ ability to improve these.

summarizes the resulting data sources by estate. While the dominance of women workers among survey participants in some estates are likely to be an overrepresentation, the high shares of respondents belonging to lower castes is supported by other sources (Labour Bureau, Citation2009, p. 19; Hari P., Citation2019a, p. 176).

Table 1. Overview estates and research participants by state.

Research participants’ informed consent and confidentiality featured prominently in our commitment to research ethics. Estate management’s agreement to participate in the study was the door through which we could reach out to workers and invite their participation. This was due to the contractual relations between the commissioning agency and three of the five participating plantation companies. The certifier insisted on these partners’ involvement based on a written confidentiality protocol. For reasons of comparability, the same approach was used in the other two estates. Seeking to protect research participants from harm, workers’ and estates’ names have been changed. The commitment to confidentiality also implies that in the dilemma between greater contextualization to enable a deeper analysis and the protection of research participants’ identities, we opted for the latter.

4. Forms of unfree labour: gendered controls on tea plantation workers’ time

Our data analysis brings to the fore that tea plantation workers’ economic coercions are mediated by plantation patriarchy. In the sub-section that follows, we demonstrate that this positions women simultaneously in charge of the labour-intensive tea harvest and of their households’ social reproduction, generating – and normalizing – gendered understandings of unfree labour. Subsequently, we show that these coercions are aggravated as workers turn to the management for loans to guarantee their household’s biological and generational reproduction. The need to repay these debts prevents workers’ exit from the estate.

4.1. Compelled to or kept from work? Gendered notions of unfree labour

Harsh disciplinary action no longer characterizes south Indian plantations’ labour governance, yet, remains central to workers’ understanding of unfree labour. At the time of their establishment during the second part of the nineteenth century, unfree labour in south Indian tea plantations was shaped by legally sanctioned physical coercion, alongside spatial isolation and economic bondage (Baak, Citation1999; Ravi Raman, Citation2002). Post-Independence, shifts from outright repressive to more patrimonial relations have taken place (Makita, Citation2012, p. 91). V., a tea plucker in her late forties, exemplifies such shifts when looking back at the changed working conditions in her estate in the Nilgiri hills of Tamil Nadu: ‘Initially, it was very difficult to work here. If we [got] late by a few minutes, the supervisor came and asked us. We [didn’t] get permission to go home once we reached the field. Now, there is no problem.’ Disciplinary action imposed by the management earlier still figures prominently in south Indian tea plantation workers’ understanding of forced labour. Therefore, asked about it in the worker survey, women and men alike unanimously respond that freedom from forced labour is guaranteed on their estate.

Economic compulsion, though, has remained a key factor that characterizes tea plantation workers’ conditions to date. V.’s undertone of satisfaction with current conditions fades later in the conversation when she talks about her difficulties to make ends meet. According to her, a wage raise of more than half the current wage would be required to cover food expenses alone. The decline in real wages alongside the steep increase in harvesting targets that affects the women-dominated workforce employed in the tea leaf harvest, in particular (Siegmann et al., Citation2019, pp. 77–79; Siegmann et al., Citation2020, p. 49), results in a situation in which the stick of poverty has replaced management’s disciplinary action as a productivity-enhancing tool.

Workers do not understand such economic compulsion as forced labour, though. For instance, south Indian tea plantation workers do not label compulsory overtime practices as forced labour when prompted. However, in continuation of colonial practices that stretched time limits ‘[…] to suit the planter, and workers were generally forced to work beyond the stipulated hours, often on empty stomachs’ (Ravi Raman, Citation2002, pp. 14–15), men state that, although remunerated at a premium rate, ‘extra work’ or kaikasu is compulsory for workers due to the widespread labour shortage (Siegmann et al., Citation2020, p. 54). Field workers carrying harvesting machines in a Keralite plantation elaborate: ‘R.: We have to do extra work whenever the management informs us. It is actually an extra burden for us. Even though we are paid for that, it is quite hectic for us. The payment for extra work is just Rs. 290 only.Footnote1 It is very little.’ – J.: ‘We need to spend almost Rs. 120 daily for children’s education.’ – R.: ‘Due to extra work [in machine harvesting], we have so many health issues such as shoulder pain, body pain etc.’ […] – Interviewer: ‘So you don’t want extra work?’ – B.: ‘It is not like that, because of this extra work only we are able to manage our household expenses. Without that, our life would become miserable.’ The futility of the liberal criterion of free and informed choice for distinguishing between forced and voluntary provision of work employed, e.g. used by the International Labour Organization (ILO) (ILO, Citation2009, pp. 8–9), becomes clear when the interviewer is trying to draw that line, asking about B.’s lack of interest in overtime work. B.’s response reflects that, beyond mutually exclusive categories of choice or coercion, it is poverty that forces him to stay on.

There are marked gender differences in how workers perceive such lengthening of the working day. Both women and men consider the regulation of their working hours a key component of their labour rights. Yet, while men foreground rights that limit their working day to eight hours, women pluckers underline their right to pause their harvest for a cup of tea or lunch. This gendered understanding of the regulation of working time reflects differences in how women and men are positioned in the ‘plantation patriarchy’s’ reproduction. After finishing their work in field or factory, social norms entitle men to rest. Paralleling what Jayawardena and Kurian (Citation2015, pp. 303–304) describe for Sri Lankan tea plantations, women workers, in contrast, normalize their duty to provide continued care to their families after their paid work in the tea leaf harvest is done. Their ability to perform the labour of care for family depends on their ability to earn cash through wage labour (Besky, Citation2017, p. 628). Hence, what humanizes tea pluckers’ working day are breaks in between, not just a merely meaningless boundary between their paid and unpaid work to secure their families’ livelihood.

As a result of this normalization, women workers criticize restrictions of overtime work, rather than complaining about it as adding to their work burden and leading to physical strain as some of the male field workers do. V. is outraged about an international certifier prohibiting the additional tea harvest for an incentive wage or ilakasu beyond the standard eight hours in an estate in Tamil Nadu: ‘If we work very hard, we used to get ilakasu along with our salary. But two years ago, one auditor visited our estate and said workers should not work in the field after 4:30pm.’ Considering that ilakasu represented about one sixth of their already insufficient monthly earnings, this implies a huge loss for poor households. The certifiers’ cap on working hours apparently did not affect men’s overtime work. The gender difference in field workers’ working hours – with, e.g. male sprayers and weeders leaving their work at 1 or 2pm – explains this: This way, even with the certifier’s cap on working hours, men can still generate overtime earnings until 4:30pm.

Women workers’ weak representation in trade unions is another facet of south India’s ‘plantation patriarchy’ that mediates such gendered experiences. Rooted in the ‘long history of class, caste, and gender domination that predates trade unionism and industrialisation in India’ (Gothoskar, Citation2021, p. 373), the leadership of tea plantation unions that rapidly emerged after their legalization post-Independence has overwhelmingly consisted of men. This contrasts with the fact that most workers and trade union members are women. In part, this is because reproductive obligations that largely fall on women limit their involvement in trade union activities (Lalitha et al., Citation2013, p. xxvi, 65–66; Raj, Citation2019, p. 683).

Gendered union politics are reflected in the implementation of labour rights (Gothoskar, Citation2021, pp. 386–390). The 1951 Plantation Labour Act (PLA) regulates Indian tea plantation workers’ wages and working time as well as their families’ welfare, including healthcare and education. After the fall in tea prices in the late 1990s, the time-rated daily wages mandated by the PLA were eroded by the growing importance of piece-rated productivity incentives. Seeking to reward workers for increased daily plucking volumes this chiefly affected women. It intensified their working conditions without entitling them to the PLA-stipulated overtime rates (Neilson & Pritchard, Citation2010, p. 1839; Siegmann et al., Citation2020, p. 48). Taken together, the interplay of the gendered nature and patriarchal control of activities in field, home, and unions invisibilise tea pluckers’ longer working hours that lower tea companies’ labour costs (Kamath & Ramanathan, Citation2017, p. 248; Siegmann et al., Citation2020, p. 48). It has implied a formalization of rights around male workers’ experiences, leading, for instance, to clearly defined shifts in the tea factory coupled with the entitlement to overtime payments, and sprayers or weeders’ shorter working days. As a result of this normalization, in contrast to men, women tea pluckers do not problematize the extension of their working day, whether induced by management controls or poverty. Rather, they protest violations of their right to secure their livelihood through incentive work. This gendered form of labour control allows tea companies to date to increase productivity by prioritizing ‘[…] increasing absolute surplus value over relative surplus value largely through extensions of the working day and through intensifying the labour process by enhancing skills through repetition’ (Kurian, Citation2018, p. 2).

4.2. Pawning off the exit from estate employment

Tea plantation workers’ economic compulsion caused by poverty wages is exacerbated as they turn to the management for loans to support their daily and generational reproduction. This practice is steeped in colonial forms of labour control, where advances that tied workers to their employers were an integral part of labour recruitment and control (the so-called kangany system) (Kumar, Citation1988; Ravi Raman, Citation2002). Loan repayments follow food and education as the two biggest expense items for south Indian tea plantation workers and are, in fact, closely connected (Siegmann et al., Citation2020, pp. 52–53).

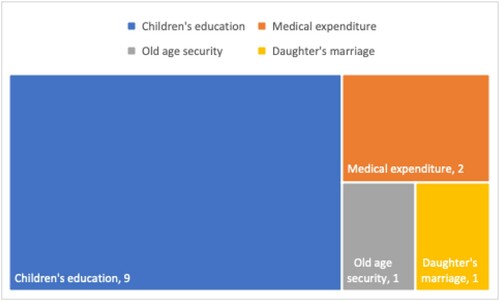

reflects that tea plantation workers take loans to pave the way for occupational mobility and, thus, a better future for their daughters and sons through higher education, an aspiration shared by plantation workers in other parts of India (e.g. Bhowmik, Citation2011, pp. 250–251; Mishra, Citation2020, p. 1102). As a result, children’s education is a key reason for plantation workers’ debt.

Figure 1. Loan uses among south Indian tea plantation workers.

Note: Numbers reflect the number of times that the respective purpose is mentioned as a use for a loan during qualitative interviews.

References to loans to cover the high costs of children’s education regularly cooccur with demands for higher wages. This is reflected in the following excerpt from a discussion among tea pluckers in a plantation in Kerala:

M.: The situation has changed over the years. The cost of living has increased and wages are not enough to meet our day to day expenses. – V.: Education expenses also increased, to meet them we are taking loans and joined in chit funds as well. […] – Moderator: What are the changes that have happened in the estate with respect to supervisors’ behaviour, individual and collective freedom for bargaining etc.? – L.: In this estate, the conditions are really good. The supervisor also behaves properly towards us and gives due respect to everyone. Also, if we inform them about our needs, they will help us. Say, for instance, for my daughter who is doing nursing in E. wanted some money for her project and I gave an application to the office and they sanctioned the amount without any delay. – A.: They are very much cooperative to us. […] – D.: Those who come for work regularly get a little bit more money, but for others who take leave frequently get only a very small amount.

Workers’ dependence on the estate management for loans translates these into a tool for labour control. Specifically, D.’s sober remark that loan amounts vary with workers’ presence suggests that loans are used to reduce workers’ absence from work in the context of widespread labour scarcity in south Indian estates.

Beyond the reduction of absenteeism, debt forms a perverse tie between workers’ care for their children’s future and management’s goal to replenish the labour pool, a tie that prevents workers from leaving the estate. While, in exceptional cases, high quality schooling is provided by the estate management (see, e.g. Moore, Citation2010, p. 26), commonly, the quality of estate primary schools mandated by the PLA is insufficient for upward mobility. The fact that workers increasingly send their children to nearby primary schools outside the estate, burdening them with high expenses for transport and fees, probably reflects both dissatisfaction with the quality of education provided in the estate school and their aim to learn English, seen as an effective steppingstone for upward mobility.

Paradoxically, this desire for their children’s social mobility ties tea plantation labourers to the estate. Without land as collateral, pledging their labour remains necessary to pay off debts. A group of Tamil speaking workers in a Keralite plantation specify indebtedness as one of the reasons for their lack of interest in employment outside the estate, revealing compulsion rather than work satisfaction: ‘A.: There is no way to leave. – P.: We have already spent the amount which we usually get during retirement.’ Taking an advance on their entitlement to provident funds comes out as a common way to meet the expenses for children’s education (Gothoskar, Citation2021, p. 391; Lalitha et al., Citation2013, p. 61). Pawning off their own old age security this way implies that ‘retirement’ is not a realistic option for elderly plantation workers. A. specifies that as long as his son does not find a ‘good job’, he and his wife are unable to exit estate employment: ‘I have one son and I am giving education to him using my salary and the Fairtrade committee’s help. We will be free from here only when he gets a job after education.’ Amidst a global tea chain in which an oligopoly of buyers and retailers put pressure on tea prices, these advances and loans guarantee plantation owners a steady supply of poorly paid labour and intensified work effort as this is the only way for workers to repay their debt (Lalitha et al., Citation2013, p. 82; LeBaron, Citation2018, p. 25).

5. From coping with plantation patriarchy to striking women: tea workers’ resistance

The multiple and gendered coercions that south Indian tea workers experience do not preclude their collective agency. Ranging from women’s informal spaces for coping to a successful women-led campaign for redistribution in Kerala’s tea industry, the examples below show how workers’ reproductive responsibilities both trigger resistance to the coercions they experience and become a resource in it.

5.1. Getting by through chit funds

While male-dominated trade unions play an ambiguous role for women workers, their own groups enable coping with plantation patriarchy. Bank loans may be out of their reach, yet, V.’s remark above reflects that informal ways of accessing loans through ‘chit funds’, i.e. rotating informal savings groups, are common among women workers, though. For her, the chit funds represent a coping strategy in the context of rising expenses for her children. Discussing Nilgiri plantation workers’ ability to save, two women point out that these informal groups do provide relief: ‘R.: Since our children are studying, we don’t have enough money to have savings at a bank. – S.: The chit fund is there.’ Such groups provide loans, e.g. for children’s education or medical emergencies with amounts up to 100 times the saved amount.

Based on our data, we can merely speculate about the deeper meaning of the chit funds for women workers in south Indian tea plantations. Parallels to what Sen’s (Citation2017) ethnography of women plantation workers in Darjeeling brings to the fore are likely, though. In the context of a weakened movement for workers’ rights (p. 109), the informal savings group (ghumauri) ‘[…] provides a space for women to discuss their daily economic and social problems away from the attention of plantation owners and Fair Trade certifiers’ (p. 108), a space where their economic and workplace needs are being taken care of (p. 130). Sen (Citation2017, p. 208) qualifies the scope of what can be achieved through the groups, though, when she concludes that women plantation workers’ ‘[…] sense of limited possibility was reinforced because the ghumauri activities only helped them cope with the discipline of the thika (wage)’, making ‘exploitation habitable’ (Sen, Citation2017, p. 193).

Yet, as detailed in the following, south Indian tea plantation workers’ response to the coercions associated with their reproductive needs and gendered normative obligations has not remained confined to such acts of resilience. Like the chit funds that enable women to cope with the multidimensional compulsions of plantation work, Katz (Citation2004, p. 246) understands resilient acts as ambiguous in their relation to the forces that necessitate them in the first place. She used the concept of reworking to refer to actions that go further to address and alter such conditions, thereby enabling more workable lives (Katz, Citation2004, p. 247).

5.2. Striking women

The Pembilai Orumai’s (Women’s Unity’s) strike in Munnar in September 2015 positioned the organization as a social actor that – successfully – demanded redistribution in Kerala’s tea industry. The month-long strike of more than 5,000 lower caste Tamil women was triggered by the plantation management’s announcement to lower workers’ annual bonus combined with the rumour that trade union leaders had secretly agreed with the company to share the undisbursed part of the bonus between them (Raj, Citation2019, p. 675). The striking women demanded a hike in their bonus, a doubling of the meagre daily wages as well as the proper implementation of their rights to healthcare and leaves (Munnar upheaval, Citation2015, p. 8; Raj, Citation2019, p. 671). While organizing not just outside the established unions, but also against them, their protest was supported by other local actors. Men were asked not to participate directly, yet, strikers’ husbands formed a tight cordon around the sit-in to prevent the violence by the Keralite police against the Tamil women (Kamath & Ramanathan, Citation2017, p. 252; Raj, Citation2019, p. 675). This way, the women cleverly mobilized gendered and ethnicised notions of vulnerability to prevent a violent escalation of the conflict (Raj, Citation2019, p. 676). The women were supported by shop keepers, artisans and restaurants owners who provided meals, collected funds and closed their shops in solidarity. A shop owner’s statement reflects that this alliance was inspired by a logic of social reproduction: ‘They spend the money that they earn in our shops for all those things they need. They help me support my family. Now was our duty to support them’ (Levy, Citation2017, p. 20). The striking women were successful in their demand for a wage raise, albeit smaller than demanded (Kamath & Ramanathan, Citation2017, p. 253).

Women workers’ outrage about their inability to provide for their children’s future was central in causing the protests. All participants of this estate’s women’s FGD declared they had joined the strike. S., a tea plucker, underlines the strike’s urgency: ‘Due to the low wage, we stopped the education of our children halfway.’ Levy (Citation2017, p. 18) argues that for many workers, the substantial drop in the annual bonus ‘[…] was particularly upsetting because [it] is the sole contributor to the plantation families’ university savings funds – one of very few ways out of the plantation livelihood.’ While an interviewed manager sketches a picture of an inclusive estate school, with children of managers and workers: ‘All of them are studying together!’, the slogan that the women shouted during the strike: ‘English medium education for your children – Tamil medium for our children … ’ (Harikrishnan, Citation2015) tells a story of class – and ethnicity-based segregation that harms their children’s prospects. The slogan’s ‘you’ – the other of the striking workers – is likely to include the trade union leaders which the women accused of accepting benefits from the estate management ‘in return for turning a blind eye to the company “squeezing the workers”’ (Raj, Citation2019, p. 682). Raj (Citation2019, p. 681) cites Pembillai Orumai leader Ponnuthai who states that: ‘The unions thought that we were just Tamil workers, and this money (the low bonus) is more than enough for us. Don't they know that we have also children like them, and needs to be taken care of.’

Ponnuthai’s remark points to historical mapping of ethnicity, gender, caste and class in Kerala’s tea plantations – and the shift marked by the rise of the Pembilai Orumai. As during the time of the plantation’s establishment under colonial rule when indentured labour was brought in from neighbouring, impoverished Tamil-speaking regions, most workers and Pembilai Orumai’s members are of Tamil origin and belong to lower castes (Hari P., Citation2019a, p. 170; Raj, Citation2019, p. 674). The discrimination that they experience to date based on their gender, caste and ethnicity detaches them from the trade unions largely led by Malayalam speaking upper caste men (Raj, Citation2019, p. 683). Rejecting the ethnic and castist disdain of being seen as cheap and undeserving labour, the strike started from women workers’ ‘retooling as political subjects and social actors’ (Katz, Citation2004, p. 247) when demanding recognition of their dignity. Rejecting the view that casts trade unions as key vehicles for collective agency and progressive change in the plantations, the movement led by poor Tamil women who refused to allow unions to be part of their struggle was seen as a slap in the face of the male-dominated unions.

Pembilai Orumai’s struggle that also targeted trade unions’ co-optation by the management was reflecting upon the plantation’s change in ownership. In 2005, the previous management Tata Tea Ltd sold the plantation to the employees of the company as part of an Employee Buy Out model, making workers shareholders of the new company Kanan Devan Hills Plantation (KDHP). Whereas Tata still holds the largest share in KDHP and workers have little say in it (Bhowmik, Citation2015, p. 31; Levy, Citation2017, p. 15), in the new situation, there is not much of a distance between the managers and trade union leaders, both of whom are mostly Malayalam-speaking men (Hari P, Citation2019b, p. 23). Yet, ‘worker ownership’ provided real opportunities to Pembilai Orumai, too. According to a KDHP manager it is productivity that qualifies a worker representative for inclusion in the cooperative company’s board. This representation increased workers’ awareness about the company’s economic situation and fed into Pembilai Orumai campaign, reflecting Sen and Majumder’s (Citation2011, p. 31) point that ideas of inclusiveness nurture expectations that make people aware of their rights and give rise to counterpolitics. Kamath and Ramanathan (Citation2017, p. 249) detail:

The president of the newly formed union, Lissy Sunny, refuted management claims of losses, saying: They said the company is facing a loss. But we know that they are making profits. So that was one of our slogans – show us your profit figures.

Pembillai Orumai made strategic use of the public sphere. In an ironic twist of their tea’s brand name ‘Ripple’, the strikers’ sit-in on the hill town’s main traffic artery for almost a month had ripple effects throughout the region. It blocked entry to and exit from Munnar, as such battering the tourism industry, another main stimulant of the local economy (Levy, Citation2017, pp. 19–20), exerting what Webster et al. (Citation2008, pp. 12–13) denote with logistical power. Foregrounding their reproductive needs rather than class antagonism provided Pembillai Orumai with what Chun (Citation2008, p. 437) terms symbolic leverage of understandings of justice that are shared in the wider society: ‘When they talked of living in decent houses and educating their children, they gained the sympathy of television viewers […] Lizzy: “Everyone who heard us cried. We cried so much we created history.”’ (Kamath & Ramanathan, Citation2017, p. 253, 255). Webster et al. (Citation2008, p. 12) summarize succinctly: ‘As symbolic power takes morality outside the realm of the employment relationship into the public domain, logistical power takes structural power outside the workplace and into the public domain’.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Fetishized images of women in colourful dresses harvesting the ‘green gold’ in gently sloping south Indian hills veil the continuity of unfree labour in the tea value chain’s capillary. The colonial plantation’s systematic use of physical punishment to discipline the workforce has ended, yet, our analysis brings to the fore how economic and social coercions that work on tea workers’ desire to guarantee their household’s daily and generational reproduction spur an equally violent circular interaction between accumulation in the global tea value chain and unfree labour (Phillips, Citation2013).

Hierarchies and ideologies of gender normalize workers’ unfreedoms. Constructions of femininity justify the lengthening of women tea pluckers’ working day as well as the intensification of their work and translate into gendered obstacles to exit plantation employment. Ironically, it is workers’ effort to enable their children’s social mobility that contributes to immobilizing the parents. Our findings complicate Bhowmik’s (Citation2011, pp. 250–251) suggestion that the situation of tea plantation workers can be improved through better education and technical training. They point to what Katz (Citation2004, p. 255) terms ‘diabolical contradictions’ of agency at the margins, like in her examples, involving quintessential issues of social reproduction where advances that workers take for the sake of their children’s future, in fact bond parents to plantation employment. The significance of workers’ concern for generational reproduction that comes to the fore here supports Shah and Lerche’s (Citation2020, p. 722) plea for an intersectional expansion of ‘[…] social reproduction theory from gender to kinship over generations’.

Our analysis suggests that technical innovation does not break the cycle between accumulation in the south India’s tea sector and unfree labour. As price-takers in the international market, to date local plantation producers concentrate on ensuring an elastic and cheap labour force. While the ongoing shift to shear and machine plucking is likely to change the gender composition of the workforce in the tea harvest in line with the dynamics, e.g. observed as a result of ‘Green Revolution’ packages, these changes do not augur well for workers’ enhanced control over their working time and conditions. Like the large workforce of women who harvest the tea manually or with shears, the men carrying harvesting machines, too are compelled ‘[…] to do extra work whenever the management informs us’, as R. puts it. While ameliorating gender inequalities in tea plantation workers’ working hours, intensity and remuneration, this is likely to be an instance of feminization as ‘harmonising down’, implying that ‘jobs [are] changed to have characteristics associated with women's historical pattern of labor force participation’ (Standing, Citation1999, p. 583).

Our findings speak to conceptual discussions of unfree labour and resistance in multiple ways. In contrast to Mezzadri (Citation2016) and Phillips’s (Citation2013) studies of the Indian garment industry, the unfreedoms we discuss do not emerge among an informal workforce but amidst India’s largest formal workforce, questioning the connections between informality, unfreedom and exploitation that Phillips (Citation2013, p. 183) identifies. Thus, while contractual even in a formal sense, different from Breman’s (Citation2007) concept of neo-bondage, these labour unfreedoms affect a workforce that is migratory largely in name only, but has, in fact, been immobilized in the plantation over generations.

Our study adds to the critique of binary understandings of unfree labour. The unfreedoms we identify predominantly have economic and social dimensions. With scholars like Lerche (Citation2007), we therefore reject conceptual and policy discourses that use physical violence or other forms of extra-economic force as defining characteristics of unfree labour, such as those spearheaded by the ILO. An earlier ruling of the Indian Supreme Court on forced labour already embraces such a broader, multi-dimensional view of unfree labour (Sreerekha, Citation2017, p. 230). Stressing that the pervasive economic compulsions of poverty and indebtedness, and the coercions associated with hegemonic gender norms are no less violent, also sets our analysis apart from the exceptionalism of ‘[…] the modern slavery discourse that positions unfree forms of labour as aberrations that operate outside of capitalism’ (Pesterfield, Citation2021, p. 1). Lastly, the unfreedoms we encounter among workers in south India’s tea plantations which are rooted in their family ties alongside hierarchies of class, gender, caste, and ethnicity are distinct from an individualized, liberal notion of unfreedom. This way, our emphasis on the ambiguous role of social reproduction for unfree labour affirms and goes beyond Mishra (Citation2020, p. 11) who argues that: ‘[…] it is the totality of the structural relations between workers and employers, rather than a narrower individualistic conceptualisation of ‘unfreedom’ in specific contracts, that informs the understanding of ‘unfree labour’ that exist in the capitalist global economy’.

Alongside the persistence of racial capitalism in the post-colonial tea value chain in which the toiling of tightly controlled brown bodies crystallises in tea ingested by consumers in the global North (Manjapra, Citation2018, p. 380), our analysis also shows how unfree labour’s desire to ‘sustain life across generations’ (Guérin & Venkatasubramanian, Citation2020, p. 2) can disrupt this violent logic. Whilst workers’ ‘fixity’ (Besky, Citation2017) in the enclaves of the tea plantations might be hard to escape even intergenerationally, it does not preclude and may even foster loud and successful demands for recognition, rights and redistribution. In contrast to Brass (Citation2003, 114) who argues that the mechanisms that shape labour unfreedoms often simultaneously fragment workers’ solidarity, we demonstrate that the factors that shape coercions among the tea value chain’s weakest links can also fuel unfree workers’ resistance. Similar to domestic workers’ organizations in New Delhi and Mumbai which use gender strategically as an exclusionary axis for organizing (Agarwala, Citation2018, pp. 50–51), women workers in south Indian and other plantations (Gothoskar, Citation2021, pp. 390–391) have turned the gender-based segregation that positioned them at the bottom of ‘plantation patriarchy’ into a source of internal solidarity. This solidarity enables resilient coping, for instance, through informal savings groups. What is more, gaining public sympathy and support by appealing to a shared need to care for their families, Pembilai Orumai’s rise and strike contributed to the reworking of south India’s plantation patriarchy.

Acknowledgements

This paper would have been impossible without the insightful collaboration with the other members of the research team in south India (in alphabetical order): Sajitha Ananthakrishnan, K.J. Joseph, Rachel Kurian, Vimal Raj, Namrata Thapa and P.K. Viswanathan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Karin Astrid Siegmann

Karin Astrid Siegmann works as Associate Professor in Labour and Gender Economics at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) of Erasmus University Rotterdam in The Hague, the Netherlands. Holding a PhD in agricultural economics, her research has been concerned with how precarious work is fashioned at the intersection of global economic processes with local labor markets, stratified by gender and other social identities.

Sreerekha Sathi

Sreerekha Sathi is an Assistant Professor in Gender and Political Economy at ISS. Prior to ISS, she taught at the University of Virginia, USA, in its Global Studies Program, and at the Department for Women’s Studies at Jamia Millia Islamia in New Delhi, India. Her areas of academic interest span theories of gender and political economy, feminist theories of development, women social welfare workers in South Asia, feminist research methodologies and epistemologies, social movements in the global south, caste politics in India and South Asia, land rights in India and Kerala Model of Development.

Notes

1 During the time of the research, €1.00 equaled INR 71.22.

References

- Agarwala, R. (2018). From theory to praxis and back to theory: Informal workers’ struggles against capitalism and patriarchy in India. In R. Agarwala, & J. J. Chun (Eds.), Gendering struggles against informal and precarious work (pp. 29–57). Bingley.

- Baak, P. E. (1999). About enslaved Ex-slaves, uncaptured contract coolies and unfreed freedmen: Some notes about ‘free’ and ‘unfree’ labour in the context of plantation development in southwest India, early sixteenth century-Mid 1990s. Modern Asian Studies, 33(1), 121–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X99003108

- Besky, S. (2017). Fixity: On the inheritance and maintenance of tea plantation houses in Darjeeling, India. American Ethnologist, 44(4), 617–631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12561

- Bhowmik, S. K. (2011). Ethnicity and isolation: Marginalization of tea plantation workers. Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts, 4(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2979/racethmulglocon.4.2.235

- Bhowmik, S. K. (2015). Living conditions of tea plantation workers. Economic and Political Weekly, 50(46), 29–32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44002859

- Brass, T. (2003). Why unfree labour is not ‘so-called’: The fictions of Jairus Banaji. Journal of Peasant Studies 31(1), 101–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0306615031000169143

- Brass, T., & Bernstein, H. (1992). Introduction: Proletarisation and deproletarisation on the colonial plantation. In E. V. Daniel, H. Bernstein, & T. Brass (Eds.), Plantations, proletarians and peasants in colonial Asia (pp. 1–40). Frank Cass.

- Breman, J. (2007). The poverty regime in village India. Oxford University Press.

- Chun, J. J. (2008). The limits of labor exclusion: Redefining the politics of split labor markets under globalization. Critical Sociology, 34(3), 433–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920507088167

- Fudge, J. (2019). (Re)Conceptualising unfree labour: Local labour control regimes and constraints on workers’ freedoms. Global Labour Journal, 10(2), 108–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15173/glj.v10i2.3654

- Gothoskar, S. (2021). Women’s relationship with trade unions – the more it changes … ? In M. E. John, & M. Gopal (Eds.), Women in the worlds of labour: Interdisciplinary and intersectional perspectives (pp. 373–395). Orient Black Swan.

- Guérin, I., & Venkatasubramanian, G. (2020). The socio-economy of debt. Revisiting debt bondage in times of financialization. Geoforum, 1–11. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.05.020.

- Gupta, R. D. (1992). Plantation labour in colonial India. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 19(3-4), 173–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03066159208438492

- Hahamovitch, C. (2017). Conclusion. In M. Sarkar (Ed.), Work out of place (pp. 238–244). Walter de Gruyter.

- Harikrishnan, C. (2015, September 17). Two leaves and a rebellion. Open. Retrieved June 28, 2021, from https://openthemagazine.com/features/india/two-leaves-and-a-rebellion/

- Hari P., S. (2019a). Assertion, negotiation and subjugation of identity: Understanding the tamil-malayali conflict in munnar. Millennial Asia, 10(2), 167–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0976399619853711

- Hari P., S. (2019b). Grievance in identity conflict: A review of Pembilai Orumai (women’s united) in munnar. Conversations in Development Studies, 2(1), 21–29. http://eprints.nias.res.in/id/eprint/596

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2009). The cost of coercion. Report of the director-general, 98th session, international labour conference. ILO.

- Jayawardena, K., & Kurian, R. (2015). Class, patriarchy and ethnicity on Sri Lankan plantations - two centuries of power and protest. Orient Blackswan Pvt.

- Kamath, R., & Ramanathan, S. (2017). Women Tea plantation workers’ strike in munnar, kerala: Lessons for trade unions in contemporary India. Critical Asian Studies, 49(2), 244–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2017.1298292

- Katz, C. (2001). Vagabond capitalism and the necessity of social reproduction. Antipode, 33(4), 709–728. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00207

- Katz, C. (2004). Growing up global: Economic restructuring and children’s everyday lives. University of Minnesota Press.

- Kumar, S. S. (1988). The kangany system in the plantations of south India: A study in the colonial mode of production. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 49, 516–519. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44148440

- Kurian, R. (2018). The industrial plantation under Colonialism in South Asia: Finance capital price takers and labour regimes, paper presented at the workshop on colonial agricultural modernities, 1750s-1870s: Capital, concepts, circulations Berlin, Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, March 22 and 23.

- Kurian, R., & Jayawardena, K. (2014). Persistent patriarchy. Pamphlet No. 03. Social Scientists’ Association.

- Kurian, R., & Jayawardena, K. (2017). Plantation patriarchy and structural violence: Women workers in Sri Lanka. In M. S. Hassankhan, L. Roopnarine, & R. Mahase (Eds.), Social and cultural dimensions of Indian indentured labour and its diaspora: Past and present (pp. 25–50). Routledge.

- Labour Bureau. (2009). Socio-economic conditions of women workers in plantation industry 2008-09. Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour & Employment.

- Lalitha, N., Nelson, V., Martin, A., & Posthumus, H. (2013). Assessing the poverty impact of sustainability standards: Indian tea. University of Greenwich.

- LeBaron, G. (2018). The global business of forced labour: Report of findings. Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) & University of Sheffield.

- Lerche, J. (2007). A Global Alliance Against Forced Labour? Unfree Labour, neo-liberal Globalization and the International Labour Organization. Journal of Agrarian Change, 7(4), 425–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2007.00152.x

- Lévesque, C., & Murray, G. (2010). Understanding union power: Resources and capabilities for renewing union capacity. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 16(3), 333–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258910373867

- Levy, S. (2017). Munnar plantation strike, 2015: A case study of Keralan female tea workers’ fight for justice. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection, 2624, 1–34. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2624

- Makita, R. (2012). Fair trade certification: The case of tea plantation workers in India. Development Policy Review, 30(1), 87–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2012.00561.x

- Manjapra, K. (2018). Plantation dispossessions: The global travel of agricultural racial capitalism. In S. Beckert, & C. Desan (Eds.), American capitalism. New histories (pp. 361–387). Columbia University Press.

- McGrath, S. (2013). Many chains to break: The multi-dimensional concept of slave labour in Brazil. Antipode, 45(4), 1005–1028. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01024.x

- McGrath, S., & Strauss, K. (2015). Unfreedom and workers’ power: Ever-present possibilities. In K. van der Pijl (Ed.), Handbook of the international political economy of production (pp. 299–317). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mezzadri, A. (2016). Class, gender and the sweatshop: On the nexus between labour commodification and exploitation. Third World Quarterly, 37(10), 1877–1900. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1180239

- Mezzadri, A. (2019). On the value of social reproduction: Informal labour, the majority world and the need for inclusive theories and politics. Radical Philosophy, 2(4), 33–41.

- Mezzadri, A. (2020). The informal labours of social reproduction. Global Labour Journal, 11(2), 156–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15173/glj.v11i2.4310

- Mishra, D. K. (2020). Seasonal migration and unfree labour in globalising India: Insights from field surveys in odisha. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63(4), 1087–1106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00277-8

- Mishra, D. K., Sarma, A., & Upadhyay, V. (2011). Invisible chains? Crisis in the tea industry and the ‘unfreedom’ of labour in Assam’s tea plantations. Contemporary South Asia, 19(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2010.549557

- Moore, L. B. (2010). Reading tea leaves: The impact of mainstreaming fair trade, LSE Working Paper Series No.10-106. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Mullings, B. (2021). Caliban, social reproduction and our future yet to come. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 118, 150–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.11.007

- Munnar upheaval. (2015). Economic & Political Weekly, 50(38), 8.

- Neilson, J., & Pritchard, B. (2010). Fairness and ethicality in their place: The regional dynamics of Fair trade and ethical sourcing agendas in the plantation districts of south India. Environment and Planning A, 42(8), 1833–1851. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a4260

- Neilson, J., & Pritchard, B. (2016). Big is not always better: Global value chain restructuring and the crisis in south Indian tea estates. In C. Stringer, & R. B. Le Heron (Eds.), Agri-food commodity Chains and Globalising networks (pp. 35–48). Routledge.

- O’Connell Davidson, J. (2010). New Slavery, Old Binaries: Human Trafficking and the Borders of Freedom. Global Networks, 10(2), 244–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2010.00284.x

- Pesterfield, C. (2021). Unfree labour and the capitalist state: An open marxist analysis of the 2015 modern slavery act. Capital & Class, 45(4), 543–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309816821997122.

- Philips, A. (2003). Rethinking culture and development: Marriage and gender among the tea plantation workers in Sri Lanka. Gender & Development, 11(2), 20–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/741954313

- Phillips, N. (2013). Unfree labour and adverse incorporation in the global economy: Comparative perspectives on Brazil and India. Economy and Society, 42(2), 171–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2012.718630

- Raj, J. (2019). Beyond the Unions: The Pembillai Orumai Women’s Strike in the South Indian Tea Belt. Journal of Agrarian Change, 19(4), 671–689. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12331

- Ravi Raman, K. (2002) Bondage in freedom: Colonial plantations in southern India, c. 1797–1947. Working Paper No. 327. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies (CDS).

- Rioux, S., LeBaron, G., & Verovšek, P. J. (2020). Capitalism and unfree labor: A review of marxist perspectives on modern slavery. Review of International Political Economy, 27(3), 709–731. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1650094

- Schmalz, S., Ludwig, C., & Webster, E. (2018). The power resources approach: Developments and challenges. Global Labour Journal, 9(2), 113–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15173/glj.v9i2.3569

- Scott, J. C. (1972). The erosion of patron-client bonds and social change in rural Southeast Asia. Journal of Asian Studies, 32(1), 5–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2053176

- Sen, D. (2017). Everyday sustainability: Gender justice and fair trade tea in Darjeeling. SUNY Press.

- Sen, D., & Majumder, S. (2011). Fair trade and fair trade certification of food and agricultural commodities. Environment and Society, 2(1), 29–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2011.020103

- Sen, S. (2004). “Without his consent?”: Marriage and women’s migration in colonial india. International Labor and Working-Class History, 65(Spring), 77–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547904000067

- Shah, A., & Lerche, J. (2020). Migration and the invisible economies of care: Production, social reproduction and seasonal migrant labour in India. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45(4), 719–734. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12401

- Siegmann, K. A., Ananthakrishnan, S., Fernando, K., Joseph, K. J., Kulasabanathan, R., Kurian, R., & Viswanathan, P. K. (2020). Fairtrade-certified tea in the hired labour sector in India and Sri Lanka: Impact study and baseline data collection. Fairtrade International.

- Siegmann, K. A., Sajitha, A., Fernando, K., Joseph, K., Romeshun, K., Kurian, R., & Viswanathan, P. K. (2019). Testing fairtrade’s labour rights commitments in South Asian tea plantations. Revue Internationale des Etudes du Developpement, 240(4), 63–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3917/ried.240.0063

- Silver, B. (2003). Workers’ movements and globalization since 1870: Forces of labour. Cambridge University Press.

- Sreerekha, M. S. (2017). State without honour. Women workers in India’s Anganwadis. Oxford University Press.

- Standing, G. (1999). Global feminization through flexible labor: A theme revisited. World Development, 27(3), 583–602. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00151-X

- Tea Board of India. (2021). State/region wise and month wise tea production data for the year 2019-20 FINAL. Tea Board of India. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from http://www.teaboard.gov.in/pdf/Production_20202_21_Apr_May_and_2020_Jan_May_pdf7291.pdf.

- van der Linden, M. (2012). The promise and challenges of global labor history. International Labor and Working-Class History, 82, 57–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547912000270

- Webster, E., Lambert, R., & Bezuidenhout, A. (2008). Grounding globalization: Labour in the age of insecurity. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wright, E. O. (2000). Working-class power, capitalist-class interests, and class compromise. American Journal of Sociology, 105(4), 957–1002. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/210397