ABSTRACT

This article explores continuities and changes in the damming of rivers in the global South. By the 2000s, the infrastructural promises of large dams seemed exhausted. Yet, currently dams are making a strong comeback with new justifications highlighting their capacity to produce low-carbon energy and climate-proofed waterscapes, while the harms they generate are being presented as fixable. Through cases from the Mekong (Laos and Cambodia), and the Grijalva (Mexico) River Basins, we problematize these claims. Despite changes in the aspirations and agencies that foster damming, obdurate dam materialities and the new profit-maximizing operation modes provoke violent continuities of infrastructural harms and hinder the repurposing of dams to serve climate combat. Neoliberalised dams even augment climate vulnerabilities, as the more volatile rivers increasingly exceed their ordering capacities. We also show how the new dam assemblages continue dispossessing riverine residents while divergently strengthening corporate and state powers and obscuring relations of responsibility.

1. Introduction

In this article, we explore continuities and changes in damming rivers in the global South, with a focus on large-scale hydropower dams and the harms they generate. By the 2000s, dams had morphed from triumphs of modernization into embodiments of the failure of high-modernist schemes, whose promise of mastery of nature had given way to broad-based acknowledgement of their socio-environmental harms (Khagram, Citation2004; Sneddon, Citation2015). More recently, however, dams have made a comeback, this time promising fixability of dam-related harms and a transition to a low-carbon future with climate-proofed rivers (Ahlers et al., Citation2017; IHA, Citation2019; Randle & Barnes, Citation2018).

Through cases from the Mekong (Laos and Cambodia) and Grijalva (Mexico) River Basins that mirror global waves of damming, we examine the shifting promises of large dams. We approach dams as infrastructural assemblages, which assists us in making sense of a seeming paradox: despite changing aspirations and multivalent political trajectories, dams generate socio-environmental harms that manifest considerable persistence. It also enables us to explore the extent to which it is possible to fix or repurpose dams, the challenges that fluvial volatilities create for large-scale hydraulic infrastructures, and the changing patterns of harm visibility.

Our study contributes to discussions on the infrastructural violence of low-carbon energy transition that problematize mainstream expectations of fixing the climate crisis by simply replacing fossil energy with renewable energy and thereby creating other kinds of socio-environmental harms (Dunlap, Citation2018; McCarthy, Citation2015; Sovacool, Citation2021). We argue that hydropower dams should feature centrally in these debates. In 2015, about 85% of the world’s renewable electricity was produced by hydropower (IEA, Citation2016). If all planned projects go through, the global river volume affected by dams will increase from 48% in 2015–93% by 2030 (Grill et al., Citation2015). Yet, energy policies focusing on low-carbon technological fixes risk downplaying the harms of hydropower dams on riverine ecologies and livelihoods (Käkönen, Citation2020; Schulz & Adams, Citation2019). The relevance of our analysis stems from the infrastructural power of dams to define futures by locking in certain hydro-social relations while foreclosing others for long periods of time, if not irreversibly.

Conceptually, our contribution bridges developments from two research areas: work on the social and political life of infrastructure influenced by science and technology studies (STS) (Appel et al., Citation2018; Harvey & Knox, Citation2015; Larkin, Citation2013) and the political ecology of hydro-social relations and vulnerability (Linton & Budds, Citation2014; Ribot, Citation2014; Swyngedouw, Citation2015; Taylor, Citation2015; Boelens et al., Citation2016). While STS-oriented infrastructure studies advance understanding on the complexities of infrastructural assemblages and the materialities of power relations, they lack sufficient accounting for the responsibility related to associated harms (Kallianos et al., Citationin press; Rodgers & O'Neill, Citation2012). We argue that political-ecological research can assist in addressing this gap, as it draws attention to the power-laden processes that make people differentially vulnerable and is attuned to identifying those agencies and institutions that can be held accountable.

Our study draws on long-term research carried out in the Mekong and Grijalva River Basins. The analysis of Mekong builds on the first author’s work on hydraulic infrastructures there, covering basin-wide dynamics while zooming into the concessionary dams of Nam Theun 2 in Laos, marketed as a flagship project of ‘sustainable hydropower’ with transnational exposure, and Chinese projects in Cambodia with suspended environmental regulations, which also produce carbon credits through Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) while concealing dam-induced harms. The field research on the effects of Nam Theun 2 was carried out in 2010, 2015, and 2016, and that on the Chinese CDM dams in 2013 and 2014. Research materials include interviews with experts, public authorities, international development actors, (I)NGO staff, and dam-affected people; these are combined with an analysis of relevant project and policy documents and impact assessments.

The second author conducted fieldwork among Chontalpa floodplain communities and resettlement sites around the city of Villahermosa in the Lower Grijalva Basin, Tabasco, south-eastern Mexico between 2011 and 2019, investigating dam-related harms, including flood disasters. Empirical data consist of dozens of interviews with fisher-farmers in lower-basin communities, residents in resettlement sites, and water-management, dam-operation, and flood-prevention authorities, flood-risk consultants, representatives of NGOs, and environmental and human-rights advocates. These were complemented with media reports, policy documents, and hydraulic infrastructure-related reports.

Bringing together research on the Mekong and the Grijalva expands on the single-case studies that have dominated previous research on hydropower (Sovacool & Walter, Citation2019), allowing us to identify patterns of (green) (post)neoliberalisation that spur resurgent damming and variegate between contexts of high dependence on foreign financing and expertise, which lends to a concessionary model of damming (Laos and Cambodia), and those with higher domestic infrastructural capacities and more state-led damming (Mexico). It also allowed us to highlight how damming has similarly evolved from high-modern, multi-purpose projects to those run by profit-motivated operators – either corporate agencies or state agencies mimicking the private sector. We argue that the way dams have been geared at hydro-electricity maximization constrains harm-mitigation efforts, uncouples damming from river-basin management, and because of augmented vulnerabilities contradicts the justificatory attempts of repurposing dams to serve as climate solutions.

We begin with a conceptual section, explaining how we approach dams as infrastructural assemblages. We then discuss the temporal waves of dam construction and associated power constellations on the Mekong and the Grijalva. Thereafter, we analyse how and to what effect damming has been neoliberalised, and we go on to show how the harms caused by newly volatile rivers are exacerbated by profit-maximizing dam-operation modes. We conclude by emphasizing that although dam assemblages have changed, their corollary socio-environmental harms persist and are even intensified, while the distribution of related responsibilities are obscured.

2. Dams as infrastructural assemblages

In our analysis, we make use of the concept of infrastructural assemblage developed in STS-oriented infrastructure studies. It illuminates how water infrastructures bind together and gather around them interacting human determinations, discursive powers and more-than-human forces, and how the characteristics and effects of dams emerge out of these interactions (Anderson et al., Citation2012; Harvey et al., Citation2017; Sneddon, Citation2015). Instead of focusing on infrastructures as fixed facilities, it foregrounds the relational processes and effects of infrastructuring (Blok et al., Citation2016). Approaching dams as (infrastructural) assemblages allows accounting for a wide set of contributing actors without conflating their intentions. It also brings into focus the materialities of dam infrastructures and the forces of fluvial waters which, together with competing or intersecting governing rationales, are key to understanding the malleability of dam assemblages and the possibilities and limits of repurposing them. We enrich the assemblage analytic with political-ecological research on the power-laden distribution of dam-generated harms, vulnerabilities, and related relations of responsibility (Atkins, Citation2021; Folch, Citation2013; Käkönen, Citation2020; Klein, Citation2015; Middleton, Citation2022 Nygren, Citation2021;).

Assemblage analysis has been associated with indeterminacy in relation to responsibility (Ferguson, Citation2012) because of its emphasis on distributed agency (Barry, Citation2020). We propose that attentiveness to diffuse responsibilities does not exclude concern for identifying those parties that could be held accountable for generated harms. Instead, a nuanced analysis of the infrastructural assemblage composition and tracing of the involved parties and forces, can assist in addressing that concern. The relevance for this stems from the increasingly complex nature of large-scale infrastructure projects (Schindler et al., Citation2019), the enduring violence that may get built into infrastructures such as dams (Blake & Barney, Citation2018; Rodgers & O'Neill, Citation2012), and the ways climate change is mobilized to abdicate responsibility for disaster vulnerability (Ribot, Citation2014; Taylor, Citation2015).

Infrastructure is not only ‘matter that enables the movement of other matter’ (Larkin, Citation2013, p. 329), but more importantly it comprises a support system that provides conditions for other things to exist or for the emergence of another order; while opening up new possibilities, it simultaneously closes others, and thus the key feature of infrastructure is dis/enabling (Boyer, Citation2017; Harvey et al., Citation2017). With the concept of infrastructural harm Kallianos et al. (Citationin press) refer to a necropolitical double-bind of infrastructure by which the generative qualities of infrastructure that affirm life of some go hand-in-hand with deleterious effects that injure others. This double-bind is evident for dams. The enabling potential of hydropower dams is to some extent multivalent, entailing two key promises: the production of electricity flows and the production of manageable river flows to be optimized for various, yet limited uses (Sneddon, Citation2015; Wyrwoll & Grafton, Citation2021). The extent to which these purposes can be aligned depends on the composition of the broader dam assemblage and the modes of the dam operation at stake. The more commercial the dam operation rationale, the more radically the purpose of the dam is reduced to hydroelectricity production, with attention paid to the broader riverine orderability only if the profits of single-commodity production are at risk. Through our cases, we highlight that as rivers are becoming increasingly volatile, tensions between the production of hydroelectricity and manageable river flows are growing. Yet, even in multipurpose operations, the enabling functions of hydropower dams inhibit various other river uses and are produced at the expense of major harms.

A key disruptive effect of dams is the disturbance to the lives and livelihoods of those who are displaced: the larger the reservoir, the larger the zones to be drowned. Furthermore, dams hold back not only water but also sediment and fish migration, drastically degrading hydroecologies that have sustained various forms of riparian livelihoods (Scudder, Citation2019). New electricity flows and market connectivities are thus produced through damaging disconnections. Some of the dam-induced connectivities can also in themselves be problematic, for example, when accompanying roads and other infrastructures instigate harmful frontier dynamics that accelerate land speculation and logging (Käkönen & Thuon, Citation2019; Milne, Citation2015) or enable state territorialization that enforces coercive rule among riverine communities (Blake & Barney, Citation2018).

The visibility of dams and their harms is relational and socio-spatially differentiated: for the dam-affected riverine residents they are intimately experienced, while for hydroelectricity consumers in faraway urban centres they easily remain in the background. There is also visibility variation because of differing harm temporalities and related patterns of resistance: reservoir-induced displacements are immediate, while downstream effects occur over longer periods of time, resembling slow violence that often receives less attention (Blake & Barney, Citation2018; Klein, Citation2015). Overall, dams entail a range of (in)visibilities from ‘opacity to spectacle’ (Harvey & Knox, Citation2015, p. 4), serving as ‘spectacular proofs’ of the powers of states, transnational companies, and/or international development agencies – or of their failures (Hetherington & Campbell, Citation2014, p. 192). Our contribution highlights key changes in the visibility of dam-related harms and relations of responsibility that are importantly tied to alterations in dam-assemblage compositions.

Recent literature has highlighted the processual features of infrastructural matter as well as how infrastructures may take new trajectories of use and function (Appel et al., Citation2018; Barry Citation2020). The liveliness of dam materialities manifests in a proneness to failure and decay, with sedimentation limiting the most productive period of electricity generation to 30–50 years. Unlike spatially dispersed urban water infrastructure (Anand, Citation2017), however, large dams offer limited space for unauthorized agency and situational manoeuvring. As spatially concentrated, sturdy constructions, dams re-scale power relations by creating nodes for centralized decision-making, which together with their capital-intensive nature and complexity opens avenues for expert, state, and corporate power formations, albeit in non-predetermined ways (Ley & Krause, Citation2019). Indeed, the reciprocally constitutive relations between infrastructure and power formations (Harvey & Knox, Citation2015) are contingent on the changing compositions of dam assemblages. From the perspective of dam-affected people, however, they are often similarly dispossessive, as the opportunities of riverine communities to decide over river uses diminish drastically while their possibilities to influence how dams are built and operated are highly limited (Ahlers et al., Citation2017) and resistance is often violently (Del Bene et al., Citation2018) or more subtly (Weißermel, Citation2021) repressed. Large dams thus serve as important reminders about the variance of infrastructural malleability: while some infrastructures can be surprisingly alterable, others can from the outset be rather obdurate and dispossessive. The most malleable or negotiable part of hydropower facilities is their operation mode, which, depending on reservoir capacity and set priorities, can accommodate flood protection or some other purposes, such as navigation, irrigation, or limited mitigation of some adverse impacts. Through our analysis, we highlight alterations in dam assemblages through which this negotiability of dam operations gets restricted.

Whereas the obduracy of dam materialities contributes to a certain persistence of the infrastructural harms, the fluidity and shifting qualities of rivers are key for understanding their changes, particularly in the form of more devastating floods. A key ambiguity of infrastructures is that they simultaneously aim at mitigating risks while producing new ones (Howe et al., Citation2016). Although damming entails attempts at socio-hydrological stabilization, it produces new complexities and instabilities. With the concept of volatile rivers, we draw attention to how increased infrastructuring together with a changing climate make river flows erratic in new ways and thus complicate the rendering of engineered rivers as ‘the infrastructure of infrastructure’ (Carse, Citation2014). At the same time dams may intensify climate-related adversities. Paradoxically, this again invokes new infrastructural controlling efforts. The way we use the term infrastructuring (Blok et al., Citation2016) draws attention to these recursive processes of river engineering.

3. Historical waves of dams

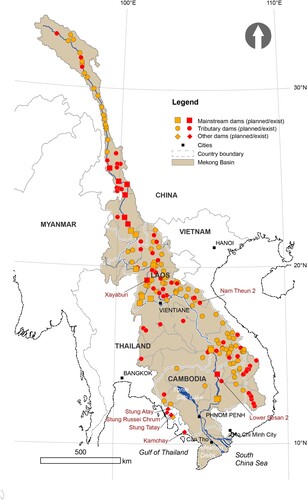

The Mekong is the twelfth-longest and in terms of flow, the eighth-largest river in the world, with an average annual discharge of 446 km3 (MRC, Citation2017). The mountainous Upper Mekong Basin is situated in China and Myanmar, and the larger Lower Mekong Basin in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The rugged topography of Laos provides the greatest hydropower potential of the Lower Basin: almost half of the basin’s estimated capacity (60,000 MW) is situated in Laos (Räsänen et al., Citation2018). In Cambodia, 400 MW of 9,000 MW potential is developed with Lower Sesan 2 dam, while most of Cambodia’s off-the-Mekong capacity has been developed with four recently built dams (). The Mekong fisheries, particularly important for Cambodia, are among the richest in the world, being sustained by a flood-pulse ecology, while the sediment-rich waters have nourished one of the world’s most productive rice-growing areas in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam.

Figure 1. Existing and planned large dams in the Mekong Basin in 2019. The Cambodian dams situated outside of the basin are marked on the map as ‘Other dams’ (by Matti Kummu).

The Grijalva River arises in the highlands of Guatemala and flows through the mountains of Chiapas in Mexico to the floodplains of Tabasco, joining the Usumacinta River before running into the Gulf of Mexico. The Grijalva-Usumacinta Basin is amongst the largest in Mexico; with 46 tributaries, it contains 31% of the freshwater sources in the country, with an annual discharge of 105 km3 (García García, Citation2013; Horton et al., Citation2021). The upper parts of the Grijalva are located at an altitude of 2,500 m, while the lowest parts are at sea level, comprising an altitude drop which makes hydropower dams attractive. The four Grijalva dams in operation – Angostura, Chicoasén, Malpaso, and Peñitas – have a total electricity generation capacity of 4,830 MW (), amounting to 40% of the country’s constructed capacity (12,125 MW) (IHA, Citation2019). Recently, the dammed Grijalva has been classified as the world’s eighteenth-riskiest deltaic river (Tessler et al., Citation2015): during heavy rains, the water levels can increase up to 3 metres in 12 h, provoking devastating floods and socially differentiated harms in the densely populated lower basin.

Figure 2. Large dams in Mexico with a focus on the Grijalva Basin (by Ohto Nygren. Sources: CONAGUA, Citation2015; INEGI, Citation2018).

Both the Mekong and the Grijalva have a long history of infrastructural interventions. The US Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which epitomized the high-modern river-basin development rationale, evolved in the 1950s into a template for numerous river basins in the global South. Subsequently it was promoted by experts from the US Bureau of Reclamation, including the Mekong and the Grijalva (Molle et al., Citation2009; Sneddon, Citation2015; Wester, Citation2009). In these first-wave TVA-influenced schemes, dams were the key technology for bringing rivers under control, serving not only the production of hydroelectricity but also flood prevention, irrigation, and agricultural modernization. They also entailed ‘hydraulic Orientalism’ (Linton, Citation2010, p. 123) with their assumptions of ‘normal’ rivers based on rivers in temperate Europe and North America. The pulsing temporalities of the monsoonal Mekong appeared as something to be rectified and disciplined (Sneddon, Citation2015) by hydraulic infrastructures with little attention paid to the ways in which this would disrupt the fluvial relationalities sustaining rich fisheries and fertile lands. Correspondingly, the rivers in the Grijalva Basin were perceived as ‘destructive giants’ (Echeagaray, Citation1957), whose capricious forces were to be tamed by massive hydropower and irrigation projects in order to turn the flood-prone Tabascan wetlands into an agricultural oasis (Tudela, Citation1989, p. 90).

North American technoscientific expertise became enmeshed with pursuits of extending US geopolitical power, especially in the Mekong Region (Sneddon, Citation2015). Massive hydraulic schemes were planned to tame not only unruly monsoonal rivers but also unruly rural populations, feared for their potential to fuel the spread of communism. Technopolitical interventions, however, devolved into intensifying military conflicts and most dam projects were derailed. Meanwhile, other rivers in Thailand and Vietnam were dammed; like most first-wave dams, they were built and operated by host-country state agencies and supported according to Cold War allegiances by the US (in Thailand) and the Soviet Union (in Vietnam) (Hirsch, Citation2010). In contrast to suspended first-wave dam projects in the Mekong, the Grijalva River in Mexico was impounded by four large dams orchestrated by Mexican state agencies with support from US experts. The Malpaso Dam, the largest in Latin America at the time, was inaugurated in 1964; Angostura in 1974, Chicoasén in 1980, and Peñitas in 1987. Together they flooded 100,000 ha of agricultural land (Tudela, Citation1989, pp. 125–126) the Angostura Dam alone displacing 15,000 indigenous and non-indigenous farmers (Dominguez, Citation2019, p. 21). They also cut off possibilities for smallholders to practise temporary agriculture (estiaje) in the floodplains during the drier periods of the year and fishing in (temporary) lagoons during rainy periods (Diaz-Perera & de los Santos González, Citation2021). The dams and the associated, mainly failed irrigation projects were planned to show the power of the state in the resource-rich ‘peripheries’ and to modernize agricultural production through the convergence of technocratic governance and state territorialization (Nygren, Citation2021). As part of the display of state power, most dams were officially named after Mexican politicians.

In the 1990s, dam development was globally challenged by environmental-social movements mobilizing anti-dam campaigns (Atkins, Citation2021; Khagram, Citation2004; McCully, Citation2001), and large dams morphed from emblems of progress (Kaika, Citation2006) into symbols of development-induced displacements and ravaged riverine ecologies and livelihoods. This exemplifies how imaginaries attached to infrastructures can change rapidly (Dalakoglou & Kallianos, Citation2018). Such contestations culminated in the establishment of the World Commission on Dams (WCD) in 1997 and its report (WCD Citation2000), which made visible previously overlooked harms, including the widely circulated estimate of 40–80 million dam-displaced people worldwide between 1960 and 1990. As a result, the World Bank and other dam supporters withdrew from many projects and the international funding for dams stalled (Richter et al., Citation2010; Zarfl et al., Citation2015). The World Bank funded Pak Mun Dam on a Mekong tributary in Thailand spurred one of the most intensive anti-dam struggles in the Mekong Region that did not stop the project but forced limited changes to dam-operation policy to accommodate fish migrations and contributed into World Bank suspending new projects (Middleton, Citation2022). In Mexico, strong mobilisations against dams resulted in the suspension of several hydropower projects planned on the Grijalva-Usumacinta and elsewhere in the country (Kauffer, Citation2013).

Recently, new hydropower projects have proliferated in many parts of the global South (Zarfl et al., Citation2015), amounting to a second wave of damming. The Mekong makes up one of the most intensive scenes of current hydropower development, with around 200 large dams in different stages of development (). Correspondingly, in Mexico, many new hydropower projects are under development, including some that were suspended earlier. Two of these are on the Grijalva: Chicoasén II and La Angostura II ().

The second wave of dam-making manifests significant shifts in the composition of infrastructural assemblages with the much more engaged private sector. In an attempt to turn hydropower dams into an attractive asset for foreign investors and business consortiums, the twenty-first-century dams are shaped by neoliberal, investor-friendly policies advanced by international development banks (Merme et al., Citation2014). The involved actors have also changed because of China’s new infrastructural foreign policy, which has made Chinese state-owned banks and enterprises (SOEs) the biggest financiers and builders of dams, particularly in contexts where damming is dependent on external infrastructural capacities,Footnote1 making use of investor-friendly policies albeit with distinctive viability rationalisations (Siciliano et al., Citation2019). The justificatory discourses have also shifted; in an attempt to re-legitimise hydropower, previously predominant and still-important dam proponents such as the World Bank have attempted to replace exhausted promises with more enchanting ones, including a ‘green economy’, sustainability, and climate change mitigation and adaptation (Ahlers et al., Citation2017; Käkönen & Kaisti, Citation2012; Sneddon, Citation2015).

Thus, the new dam assemblages are in many instances internally contradictory: while dams are expected to fix previous harms and take on new multi-purpose functions, including the climate-proofing of rivers, neoliberal reforms encourage dam operators to single-purposely optimize hydroelectricity production. At the same time, the earlier amalgamation of river-basin planning and dam development is being increasingly uncoupled. The power effects have altered as well: the centralized nodes of hydro-social ordering now lend more to strengthened corporate power rather than hydraulic state powers.

4. Neoliberalised dams: persistent harms and obscured responsibilities

Herein we examine the formation and effects of the new dam assemblages in Mekong and Grijalva, showing how the second wave of damming has evolved through variegated neoliberalisation that intersects with authoritarian and neo-patrimonial governing. In Mekong, because of dependencies on external finances and capacities, the new dams have been contracted out to various types of international business consortiums, while in Grijalva the previously and more recently built dams continue to be operated by state-owned agencies that have been restructured to operate like private ones. Common in both cases is the business-oriented mode of dam-making and operations, which generates complex and obscured relations of responsibility for the harms persistently generated. In both cases dam assemblages also exhibit certain (differing) post-neoliberal features that, however, rather build on the neoliberal profit-maximization logic than alter it.

Key agencies that have shaped the new Mekong dam assemblages include the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, which since the 1990s have attempted to transition the Mekong Region from ‘battlefield to marketplace’ with neoliberal juridico-institutional reforms of investor friendliness (Bakker, Citation1999, Glassman, Citation2010). These include the concessionary Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) property arrangement for dams, which has facilitated their recent proliferation in Laos and Cambodia. The BOT contracts of 24–45 years guarantee the concessionaire with profitable years after the loan payback period, while handing the dam over to the state authority before the maintenance costs of decaying infrastructure increase. They also guarantee a high degree of autonomy in altering riverine flows to create a regime that is optimal for maximized electricity sales and frequently include clauses to pre-empt riverine uses and regulations, which may threaten the profitability of dam operations. The details of these contracts are mostly occluded from the public, adding significant opacity to the terms of dam operations (Merme et al., Citation2014). The way the concessionary deals materialize in exclusionary dam enclaves further shields them from external oversight and public scrutiny. At the same time, the attempts of the intergovernmental Mekong River Commission to tie hydropower development to integrated planning of basin development have been side-lined (Middleton, Citation2022).

On one hand, the new concessionary dam assemblages in Laos and Cambodia cohere. They all generate corporate enclaves with dam controllers that maximize electricity sales and thus disrupt seasonal flow rhythms, related hydroecology, hydro-social relations, and livelihoods by generating erratic off-season flow patterns determined by peaks in daily, weekly, and seasonal electricity demand in faraway urban centres (mostly in Thailand in the case of Laos, and the domestic capital in Cambodia) (Baird & Quastel, Citation2015). On the other hand, the concessionary dams have attracted a wide range of agencies, and many aspects of dam governance thus differ as they depend on the composition of the assembled parties. In Laos, the dam concessionaires are predominately private Thai and state-owned Vietnamese and Chinese companies and investors. The first spearhead projects also included European companies with the involvement of the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. In Cambodia, all the five large dams have been concessioned to Chinese SOEs. Together with the high degree of autonomy granted to the heterogeneous concessionaire consortiums, this means that the dams are variously networked and transnationalised resulting in differing patterns of visibility, harm-mitigation, treatment of affected people, and relations of responsibility. As a result, the projects range from those attempting to set higher harm-mitigation standards to those with added exploitative opportunities provided by exemptions from the existing jurisdiction of the host state. The former is exemplified by the World Bank-supported Nam Theun 2 (NT2) dam in Laos, and the latter by the China-built and operated dams in Cambodia.

NT2 is the largest tributary dam in Laos (1070 MW), exporting 95% of its electricity to Thailand. It marks the come-back of the World Bank to the dam business, as well as its attempt to contain previous critiques by demonstrating the fixability of dam-induced harms. It has been formative of a new assemblage of ‘sustainable hydropower’ that consists less of altered material infrastructures than of discursive shifts and altered governing practices. Its novel elements are contradictory. It meant to turn Lao dams into an attractive asset class while validating globally that dams can be sustainable and provide ‘net benefits’ for those affected. Laos has offered an expedient environment for both objectives because of its one-party rule, which effectively restricts local opposition.

The project represents a complex public-private partnership: it is concessioned for 25 years to a company consisting of shareholders from France and Thailand with a state-owned Lao company; its financiers comprise 27 parties, including Thai and OECD commercial banks, for whom the World Bank provided risk guarantees (Merme et al., Citation2014). The World Bank obliged the concessionaire to compensate for losses on a scale not seen previously in the global South and provided additional funds for the compensatory programmes. Yet, the harm-mitigation promises have fallen short. The resettlement scheme of 6,300 people has delivered the promised houses, electricity, and schools but the programmes of livelihood restoration have experienced major setbacks (Hunt et al., Citation2018). The pioneering attempts to address the losses in fisheries and flood-recession harvests suffered by the 155,000 downstream residents have been even more disappointing. Instead of considering less-harmful dam-operation modes, the fixation efforts have consisted of insufficient compensation programmes with micro-credit schemes that have furthered indebtedness (Baird et al., Citation2015; field interviews in 2015 and 2016). Thus, despite novel harm-mitigation efforts, the project has remained dispossessionary. It has, however, succeeded in its other objective: by building investor confidence, it paved the way for new projects. Instead of leveraging more ‘sustainable dams’, it triggered projects with lower sustainability standards (Johns, Citation2015) and less international exposure. According to interviewed local authorities and ex-NT2 consultants, the Thai, Vietnamese, and Chinese developers of the subsequent dams are less exposed to reputational risks and have considered the compensation costs of the NT2 sustainability model to be too profit-inhibitive. Instead of proving the fixability of dams, NT2 illustrates that even partial harm mitigation is perceived to be too costly by the profit-maximizing operators of the concessionary dams. Despite its significant shortcomings, NT2 is continuously referenced in order to validate and promote the model of ‘sustainable hydropower’ in other parts of the world (Middleton, Citation2018).

In Cambodia, the World Bank pushed a similar template of pro-corporate concessionary dams. Attracting foreign private investors and developers, however, has been challenging because of less clear profit-prospects. The BOT dam contracts have been taken up instead by state-owned Chinese banks and companies, which operate with a post-neoliberal rationale in the sense that they may undertake not-so-profitable projects if they yield other opportunities that China considers geopolitically or geoeconomically important (Lee, Citation2018; Siciliano et al., Citation2019). Chinese state-owned enterprises are, however, expected to optimize the economic viability of their not-so-profitable contracts (Lee, Citation2018). Herein the authoritarian Cambodian ruling regime has provided the concessionaires with augmented exploitative opportunities via exemptions in EIA regulations and labour laws. It has also granted exceptional access to rivers within protected forest areas. The insulation of projects from host-state regulatory frameworks allows for invisibilisation and nominal mitigation of socio-environmental harms, while the exclusivity of the dam enclaves further shields them from external oversight. Interviewed local-level authorities and NGOs (March 2014) expressed strong frustration because of denied access to inspect cases of worker maltreatment, injuries, and lethal accidents in the dam construction sites, and they accused the highest level of authorities for overt non-interference.

Meanwhile, four out of the five large Cambodian dams are CDM projects, which produce not only electricity but also carbon offsets, adding a new justification for the dams and an additional layer of harm concealment. Three are located within the protected forests of the Cardamom Mountains, a watershed for the Mekong Basin. While the integration of the dams into the global governing space of climate change exposed the projects internationally, the harms they produced were obscured because the CDM’s regulatory assessments mainly focus on carbon, allowing slack accounting, verification, and monitoring of other socio-environmental impacts. What the enclave exclusivity and carbon reductionism jointly concealed were the dispossession of fishers, vulnerabilisation of coastal residents, exploitation of construction workers and intimidation of communities by violent logging tycoons (Käkönen & Thuon, Citation2019). At the same time, sold carbon credits complicate the dam assemblage and extend relations of responsibility for these harms to CDM regulatory bodies as well as to international credit buyers (in this case, corporations in Sweden, Switzerland, and the Netherlands).

In terms of power effects, all of the Mekong second-wave concessionary dams strengthen corporate powers. By contracting out the dam operations, the state authorities give away the concentrated capacities to order rivers and hydro-social relations. The complex dam assemblages, however, also accommodate state interests that are disparate from those of the concessionaires and strengthen not hydraulic but instead other state capacities through the ways dams connect with other infrastructural processes. The roads that accompany dams, together with reservoir-related salvage logging, trigger timber extraction in vast, previously inaccessible areas from which rents are captured through elite patronage relations and, particularly in Cambodia, channelled into consolidating the powers of the ruling party (Käkönen & Thuon, Citation2019; Milne, Citation2015). In Laos, state authorities have been able to gear the dam-induced roads and resettlements schemes towards their long-term objectives of rendering the unruly upland parts of the country and their dispersed settlements of ethnic minorities into more readily governable units (Blake & Barney, Citation2018). The Chinese dams, especially in Cambodia, spearhead broader infrastructural corridors and constellations of bilateral affairs, which, while entailing new political-economic dependencies on China, include generous grants, loans, military assistance, and new opportunities for state patronage free from external oversight. These effects should also be accounted for as part of the infrastructural harms of dams to the extent that they strengthen coercive patronage-based authoritarian rule.

On the Grijalva, the Federal Commission of Electricity is in charge of the dams, but since the 1990s it has been restructured to manage them like private corporations in order to maximize sales and satisfy growing electricity demand. Each of the four Grijalva dams nowadays operates separately, competing for electricity sales during peak periods of consumption in the mega-cities and industrial production zones of central and northern Mexico. This has meant a shift away from previous state corporatism and centrally coordinated river-basin management. Also, the two new dams under construction, of which Angostura II is projected to export electricity to Central America, are market-oriented and being developed through new types of public-private partnerships and modes of hybrid outsourcing. Interviewed dam-operation authorities emphasized that the use of river flows is optimized ‘for not letting a drop of water run to the sea without maximizing its utility through several rounds of hydroelectricity generation’ (Interviews, April 2013, Nov. 2019). Meanwhile, they argued that the possible harms of such maximization are temporary and kept carefully under control. This is highly questionable, however, as we will show in the following section.

Despite neoliberal reforms, state ownership enables a certain continuation for integrating dams in basin planning. For example, the authorities suggested that if harnessing of the Grijalva was maximized, the adjacent Usumacinta could be ‘left intact’ (Interview, April 2016). The concessionary governing mode in the Mekong, in contrast, limits such considerations and side-lines the suggestions of the Mekong River Commission to prioritize only the least harmful projects. The neoliberal policies, however, have fragmented water governance also in Grijalva, as the dams are made to compete with each other and the environmental impact assessments are outsourced to private consultants. There is also a long-term challenge related to the institutional division of labour: the federal-level National Water Commission (CONAGUA) administers rivers used for hydroelectricity production and the Federal Electricity Commission manages dam operations, while the state-level Ministry of Civil Protection is responsible for flood-prevention strategies. In the multifaceted negotiations, rivalries, and trade-offs between the institutions, local resource rights and livelihood needs are ignored, while the complex upper-, middle-, and lower-basin interconnections and interlinked effects of dams and other forms of infrastructuring are under-recognised. Similarly, the project-by-project assessments of Mekong dams make the more cumulative dam effects invisible, as well as the ways they interact with the effects of other forms of river engineering and with other extractive projects (Baird & Barney, Citation2017).

The governing modes in Mexico have partly morphed into post-neoliberal ones, not in terms of altered profit-maximization logic, but in terms of claims on altered usage of profits, as the new left-wing populist rulers promise to address long-term grievances regarding unjust benefits and harm distribution. Local residents have repeatedly complained about the dams producing a ‘huge amount of electricity for Mexico City, while we who live nearby the dams are suffering from poorly maintained water and electricity networks’ (Interviews, Aug. 2011, April 2013). The promises to address these complaints are combined with enforced suppression of dissent and new authoritarian psycho-political tactics (Coates & Nygren, Citation2020; Dunlap, Citation2018). The construction of Chicoasén II Dam by a consortium of Mexican and Chinese-Costa Rican companies began in 2014 but was halted in 2016 due to conflicts with local residents who felt they had not been adequately consulted. In 2019, however, the federal government announced that work would start again, with a planned inauguration in 2024 (El Heraldo de Chiapas, 15 July 2019). Resistance was suppressed through a combination of harsh mobilization of authoritarian state powers and justifications drawing from discourses of energy sovereignty and national patrimony with claims of using the revenues from electricity sales more fairly, including offering better public services for the riparian poor. The advocates of anti-dam mobilization, in turn, are categorized as traitors to the homeland, who seek to prevent ‘green’ and ‘socially just’ development.

The way neoliberal governing is combined with authoritarian control in the remodified Grijalvan dam assemblages not only ensures efficient surveillance of newly emerging anti-dam movements but also hides relations of liability. The hybridization of state-led and market-based forms of regulation, clientelist networking, and neoliberal outsourcing in the multifaceted public-private partnerships insulate the impacts of dams from public scrutiny and diffuse issues of responsibility, making it difficult for residents to identify who is responsible for what and to whom.

On both the Mekong and the Grijalva, the (post)neoliberalised modes of assembling and governing dams invisibilise infrastructural harms and obscure related responsibilities while authoritarian measures have assisted in supressing resistance. In both cases dam assemblages exhibit change in terms of how they are financed and justified, what kinds of agendas they are made to serve, whose capacities they strengthen, and how responsibility for harms is distributed; meanwhile, the actual dam facilities remain relatively unaltered, with most of their harms in-built to their material properties. The negotiability of dam operation, in turn, is restricted by the ways dams have been set to maximize electricity sales. This is becoming increasingly problematic, because the properties of rivers are rapidly changing.

5. More volatile rivers: new harms and sacrificed zones

Climate change has altered the dam assemblages in several interrelated ways. New climate-related discursive elements have been key in the re-legitimation efforts of dams. In Mexico, a powerful petro-state, hydropower is framed as strategic for transitioning to a post-carbon economy while in Laos and Cambodia, hydropower is framed as essential for avoiding fossil lock-in and it plays a key role in nationally determined mitigation contributions. The climate mitigation claims are particularly questionable in Mekong, however, where the emissions from biggest reservoirs can equal to those fossil-fuel plants (Räsänen et al., Citation2018). At the same time, climate change shapes the dam assemblages because it alters the rivers that have been or are to be dammed. This challenges the ordering capacities of dams and provokes aspirations of taming river flows that are fluctuating in newly erratic ways. Because the rivers are not becoming more volatile only because of the changing climate, but also because of accelerated river engineering, new dynamics get introduced to the politics of responsibility, which relates to how lines of causality are drawn between the climate and the engineered, as evidenced by both cases. Experiences from Grijalva and Mekong also demonstrate that the neoliberalised dams work against rather than for climate adaptation, thus highlighting the limits of their repurposing.

As a deltaic river, the Lower Grijalva is inclined to modify its course through avulsions, with archival sources listing six large-scale avulsions and 55 serious floods during the last four hundred years (García García, Citation2013). In recent years, the rivers of the Grijalva Basin have become increasingly volatile, as massive dams and irrigation projects have altered water and sediment flows, soil characteristics, fisheries, and agro-ecologies (Ezcurra et al., Citation2019). The altered hydro-ecological conditions, together with the changing climate, have intensified flood risks and vulnerabilities (Horton et al., Citation2021).

An exceptionally devastating flood occurred on the Grijalva in 2007, when 62% of Tabasco was inundated, resulting in damages calculated at USD 3 billion (CEPAL 2008). The role of the Grijalva dams in exacerbating the disaster has been heavily debated. In many interviews, water and dam authorities argued that the 2007 disaster was caused by extreme hydro-meteorological conditions that are becoming more frequent because of climate change, while representatives of NGOs and environmental activists attributed responsibility for the disaster to the dams’ operation patterns calibrated to maximum energy production. In fact, the water level in the Peñitas reservoir had reached four metres above the maximum level of operation before the emergency spillways were opened. This caused an exceptional increase in downstream water levels, provoking devastating floods, especially in the city of Villahermosa and its surroundings (SEGOP 2008). After the disaster, the government resettled 30,000 informal residents from the city of Villahermosa to peri-urban margins. In these resettlement sites, people recounted their traumatic disaster experiences, during which their homes ‘were flooded up to the roof’ (Interview, August 2011), and told how the state officials thereafter ‘brutally ordered their relocation’ (Interview, April 2013). People claimed that the disaster smelled of ‘dam water’ (Interview, Oct. 2011), pointing to the eagerness of the Federal Committee of Electricity (CFE) to maximize electricity production. The CFE has never denied the operating logic of maximum electricity production but has repeatedly argued that it does not compromise sustainable dam management (Nygren, Citation2016). Information-sharing on dam operations is severely restricted and referred to as a matter of national safety, which makes it difficult to trace liabilities for devastating disasters and enables dam operators and authorities to evade questions of responsibility. However, it does seem that the dam-operation mode did contribute to the 2007 disaster, together with heavy rainfall and settlement policies ignoring disparities in residents’ flood vulnerabilities.

Similar events were repeated in the 2020 flood disaster, albeit with new patterns of harm distribution related to recently implemented projects of flood prevention, which included new levees, embankments, floodwalls, gate structures, canals for water transfers, and river-straightening efforts. Governmental authorities have been hesitant to admit that these infrastructuring efforts may be exacerbating the problems they aim to correct, provoking new risks. Due to dense riverbank building, many Grijalvan rivers have little room to expand, and embankments may prove counter-effective as floodwaters often flow over protective structures, which then hinder their receding. While enhancing safety for some, water diversions through channels increase the vulnerability of others. The construction of the Macayo gate structure in 2013 to divert critical water flows from the Carrizal River to the Samaria has shifted the flood problem from Villahermosa to the indigenous communities of Nacajuca. The justification has been that indigenous people are accustomed to living with water and have traditional means to adapt to high water, while densely populated Villahermosa, as an engine of economic progress, needs maximum protection. After the 2020 disaster, Mexican President Manuel Andrés López Obrador confirmed in an interview for the newspaper Universal: ‘The [Macayo] gate was closed, so that all the water from the dams would flow through the Samaria … This harmed the people of Nacajuca, the [indigenous] Chontales, the poorest of the poor.’ He added, however, that ‘it was justified to prevent a major flood in Villahermosa’.Footnote2 Such views legitimise socially differentiated governance, which distributes the burdens of dams and hydraulic infrastructuring to marginalized indigenous communities and smallholder villages while protecting better-off urban populations.

While global media has paid attention to organized anti-dam struggles in the Grijalva upper and middle basins, the long-term effects of damming on lowland populations have been overlooked. During dam constructions, the surrounding middle-basin inhabitants were paid moderate compensations, while lower-basin residents suffering from floods aggravated by maximized electricity production are asked to develop strategies of self-help, based on neoliberal principles of self-responsibilisation (Nygren, Citation2018). In interviews, residents of the Grijalva lower-basin agricultural communities and peri-urban resettlement sites called for better recognition of the harms they had suffered, including increased exposure to flood disasters, deteriorated livelihoods, and forced relocations. Many indigenous groups and peasant fisher-farmers feel that they have had no say over interventions which have drastically changed their lives and livelihoods and rendered the lowlands of the Grijalva ‘zones of sacrifice’ to the benefit of affluent urban populations.

In the monsoonal Mekong, seasonal variations in water levels are greater than in the humid-tropical Grijalva. As dams reduce seasonal variation, a persistent narrative that dams beneficially temper floods and droughts has circulated for decades (Sneddon, Citation2015). This acclimatizing function of dams is gaining a new valence because the changing climate is augmenting seasonal extremes and riverine volatilities (Käkönen, Citation2020). Recent modelling exercises suggest that the cumulative impacts of dams indeed reduce seasonal fluctuations, including their climate change-induced augmentation (Horton et al., Citation2022). Yet, the potential of reservoirs to mitigate floods is largely applicable to regular, seasonally pulsing floods that are vital for Mekong’s hydro-ecology, fisheries, and soil fertility, with the Mekong River Commission estimating the average annual value of flood benefits at USD 8–10 billion and flood costs at USD 60–70 million. In terms of extreme events, however, dams have a limited capacity to store abruptly increased inflow, particularly when they are set to maximize hydroelectricity production; in the worst cases, dam operators resort to emergency releases that exacerbate downstream flooding (MRC, Citation2017). The paradox is that while dams do away with important flood-related riverine affordances, they can aggravate exceptional floods, which are becoming more frequent due to climate change.

On a tributary scale, trans-basin diversion dams, such as the NT2, are especially problematic. Before the dam, the benefits of floods in terms of ‘free’ alluvium and pest management had made Xe Bang Fai valley one of the most fertile rice-growing areas in Laos. Now it has been identified as one of the country’s ‘hotspots’ for future climate-induced flood disasters. In official documents and interviews with ministry officials (June 2016) the intensified floods are readily discussed within the frame of climate change; at the same time, attention is deflected from how additional water discharge from the NT2 reservoir has transformed the floods from a force that is beneficial to harvests into one that is destructive. There are also indications that the profit-maximizing dam-operation mode may exacerbate exceptional floods, of which the devastating flood of 2011 provides an example. While the hydropower company denies responsibility and claims that it refrained from releasing water when the river had reached the maximum level, at which the company is obliged to shut off water discharges, it remains possible that the dam-operation mode added to the intensity and duration of the flooding (Baird & Quastel, Citation2015). Interviewed Laos-based experts suggested that other dams have resorted to similarly harmful emergency releases, although confirmed evidence is lacking because dam-related public discussions are sanctioned.

The NT2 case in Mekong tributary resonates with Grijalva in terms of differential flood-protection measures that have been partly provoked by dam-intensified floods. While some flood-affected rural communities – mostly more affluent ones – have been provided with upgraded flood-protection infrastructures, other communities with ethnic minorities have been targeted with forced resettlement. Moreover, interviewed provincial and commune authorities (July 2016) reported that flood-protection systems risk exacerbating floods in unprotected areas, and they can malfunction in cases of exceptional floods, thus strengthening the infrastructural basis of flood disasters.

On the basin scale, the new Mekong dams have displaced tens of thousands of people. Cumulative effects from flow alterations and the blocking of fish migration may amount to a 40–80% loss of Basin’s fisheries by 2040 if all planned dams are built, injuring the lives of 40 million fishers and threatening food security in Laos and Cambodia (MRC, Citation2017). These cascading harms also make affected people more vulnerable to climate change. The ways the dams trap sediment is particularly detrimental for the Vietnamese Delta because of amplified effects from rising sea levels (Kondolf et al., Citation2014).

Common to both the Grijalva and Mekong is that the responses to more volatile rivers have not included alterations to profit-maximizing dam operations but instead have included new rounds of river engineering, which in turn engender new risks. In the worst cases, these entail infrastructural violence as the lives of more affluent groups are protected at the expense of those already marginalized, who are put in harm’s way. On the Grijalva, the stronger state ownership of dams means that at least in principle, state authorities are able to intervene in how the dams are operated, leaving the possibility for social movements to apply pressure, while with the Mekong dams, attempts at such interventions are more forcefully pre-empted by the decades-long concessionary contracts.

6. Conclusion

This article has analysed the trajectories of damming rivers in the global South through cases from the Mekong and Grijalva, showing how dams have evolved from high-modern, multi-purpose projects towards variegated (green) neoliberalisation, materializing in concessionary corporate hydropower enclaves in the Mekong and in state-led dam-operating agencies restructured to mimic private-sector operators in the Grijalva. Despite alterations in the dam assemblages, including constitutive and resultant power formations and the promises animating the dams, the dam-related harms are strikingly persistent. Even the recent dams designed on the basis of principles of sustainability and eco-modern safeguards disrupt fluvial relationalities, reduce diverse riverine uses and dispossess riparian residents.

The persistence of harms is closely related to the dams’ obdurate materialities, which inherently disrupt fluvial relationalities and create centralized nodes for hydro-social ordering. While recent infrastructure studies have emphasized the alterability of infrastructures, our study reminds that some infrastructures are less malleable than others underlining the importance of detailed reflection on the variation of infrastructural qualities. Limited success in harm fixation is also related to operation modes increasingly geared towards maximizing sales of hydroelectricity.

Our study highlights that the more profit-oriented the operation logic, the more restricted the possibilities are to repurpose dams to serve climate governance, through which dams have forcefully been re-legitimised. Instead of climate-proofing rivers, the profit-maximizing dams may exacerbate devastating floods, which are becoming more frequent because of the changing climate. Thus, it is the way that the changing qualities of rivers interact with the governing modes of dams that brings about newly intensified forms of harms. Our study shows how infrastructural harm-mitigation efforts have not altered dam operations but instead provoked new infrastructural interventions that result in severe injustices as exemplified by new flood gates on the Grijalva, which in extreme floods render the waterscapes of already marginalized rural communities into ‘zones of sacrifice’ in order to protect more affluent urban populations.

The power effects of damming the Mekong and the Grijalva share a resemblance in the concentration of the hydro-social ordering powers whilst the corporate and state powers are strengthened divergently and in differing intensities. Whereas the first-wave dams were drawn into developmentalist statecraft (Molle et al., Citation2009) in congruence with ‘full control’ basin development generating more-or-less centrally coordinated river engineering, the more private second-wave dams in both cases fragment basin planning and generate more complex and diffuse relations of responsibility. Because of the continued state ownership of dams on the Grijalva, the dam-operation modes could at least in principle be re-negotiated, leaving potential for public pressure; while on the Mekong, the decades-long concessionary contracts severely constrain any changes in operations. In both cases, the way that second-wave damming materializes in complex dam assemblages with manifold public-private networks obscures issues of responsibility related to socially differentiated harms. In addition, climate change is increasingly framed as causing water disasters, thereby distracting from more proximate causes on how infrastructural decisions may aggravate them. Amidst these complexities, a nuanced analysis of the changing infrastructural assemblage compositions when combined with political-ecological analyses of differentiated vulnerabilities becomes potent, as it reduces zones of opacity and assists in disentangling liabilities and identifying parties that could be held accountable.

Reversing the extractive pathways that put liveable environments at risk is closely intertwined with infrastructural politics. It is as if we are at an infrastructural watershed, facing questions about the extent to which current infrastructural formations can be retrofitted or decommissioned to avoid a looming environmental catastrophe (Boyer, Citation2017; Truscello, Citation2020). Given the in-built socio-environmental harms and the restricted repurposing possibilities, we contend that the central role dams have been accorded to facilitate low-carbon transitions and climate-proofing of rivers should be seriously questioned.

Acknowledgements

Comments by Dimitris Dalakoglou, Yannis Kallianos, Alexander Dunlap, and the three anonymous reviewers improved the argument. Helpful comments were received from Chris Sneddon and others at the AAG 2022 Session ‘Contesting Hydropower: Novel Approaches to Water Conflict’. The paper has also benefited from insightful discussions with Keith Barney, Jessica Budds, Sango Mahanty, Carl Middleton, Tuomas Tammisto as well as with the WATVUL project colleagues including Miguel A. Díaz Perera, Alexander Horton, Edith Kauffer, Matti Kummu, Anu Lounela, Dora Elia Ramos Muñoz and Try Thuon. Thanks to Matti Kummu and Ohto Nygren for help in producing the maps.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mira Käkönen

Mira Käkönen is a postdoctoral fellow at the Tampere Institute for Advanced Study and the Unit of Social Research, Tampere University. Her research topics include political ecology of water, climate change, and resource making. She has particularly focused on exploring the changing entanglements of rivers, infrastructure, and power relations in the Mekong Region, Southeast Asia. Her work has been published in journals that range from The Journal of Peasant Studies to Journal of Hydrology.

Anja Nygren

Anja Nygren is Professor of Global Development Studies at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Her research interests include extractivism, political ecology, water governance, disasters and displacements, and responsibility and justice. She has carried out long-term research in Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. She has published articles in many scientific journals, such as Annals of the American Association of Geographers, Critique of Anthropology, Development and Change, Journal of Latin America Studies, Geoforum, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Journal of Hydrology, Journal of Peasant Studies, and World Development.

Notes

1 In 2001–2020 the Chinese policy banks have mobilized twice the amount of financing ($44 billion) compared to multilateral development banks (Kong, Citation2021).

References

- Ahlers, R., Zwaerteveen, M., & Bakker, K. (2017). Large dam development: From Trojan horse to Pandora's box. In B. Flyvbjerg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of mega project management (pp. 566–576). Oxford University Press.

- Anand, N. (2017). Hydraulic city: Water and the infrastructures of citizenship in Mumbai. Duke University Press.

- Anderson, B., Kearnes, M., McFarlane, C., & Swanton, D. (2012). On assemblages and geography. Dialogues in Human Geography, 2(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820612449261

- Appel, H., Anand, N., & Gupta, A. (2018). Introduction: Temporality, politics, and the promise of infrastructure. In N. Anand, A. Gupta, & H. Appel (Eds.), The promise of infrastructure (pp. 1–38). Duke University Press.

- Atkins, E. (2021). Contesting hydropower in the Brazilian Amazon. Routledge.

- Baird, I., & Barney, K. (2017). The political ecology of cross-sectoral cumulative impacts: Modern landscapes, large hydropower dams and industrial tree plantations in Laos and Cambodia. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(4), 769–795. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1289921

- Baird, I., & Quastel, N. (2015). Rescaling and reordering nature-society relations: The Nam Theun 2 hydropower dam and Laos-Thailand electricity networks. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105(6), 1221–1239. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2015.1064511

- Baird, I., Shoemaker, B., & Manorom, M. (2015). The people and their river, the World Bank and its dam: Revisiting the Xe Bang Fai River in Laos. Development and Change, 46(5), 1080–1105. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12186

- Bakker, K. (1999). The politics of hydropower: Developing the Mekong. Political Geography, 18(2), 209–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(98)00085-7

- Barry, A., (2020). The material politics of infrastructure. In S. Maasen et al. (Ed.), Technosciencesociety. Springer.

- Blake, D., & Barney, K. (2018). Structural injustice, slow violence? The political ecology of a “best practice” hydropower dam in Lao PDR. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 48(5), 808–834. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2018.1482560

- Blok, A., Nakazora, M., & Winthereik, B. R. (2016). Infrastructuring environments. Science as Culture, 25(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2015.1081500

- Boelens, R., Hoogesteger, J., Swyngedouw, E., Vos, J., & Wester, P. (2016). Hydrosocial territories: A political ecology perspective. Water International, 41(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2016.1134898

- Boyer, D. (2017). Revolutionary infrastructure. In P. Harvey, J. C. Bruun, & A. Morita (Eds.), Infrastructures and social complexity: A companion (pp. 174–186). Routledge.

- Carse, A. (2014). Beyond the big ditch: Politics, ecology, and infrastructure at the Panama canal. MIT Press.

- Coates, R., & Nygren, A. (2020). Urban floods, clientelism, and the political ecology of the state in Latin America. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110(5), 1301–1317. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2019.1701977

- CONAGUA [Comisión Nacional del Agua]. (2015). Estadísticas del agua en méxico. CONAGUA.

- Dalakoglou, D., & Kallianos, Y. (2018). ‘Eating mountains’ and ‘eating each other’: Disjunctive modernization, infrastructural imaginaries and crisis in greece. Political Geography, 67, 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.08.009

- Del Bene, D., Scheidel, A., & Temper, L. (2018). More dams, more violence? A global analysis on resistances and repression around conflictive dams through co-produced knowledge. Sustainability Science, 13(3), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0558-1

- Diaz-Perera, M. A., & de los Santos González, C. C. (2021). La frontera olvidada: El poblamiento costero a través de cuatro momentos decisivos 1518–2020. El Colegio de la Frontera Sur.

- Dominguez, J. (2019). La construcción de presas en México: Evolución, situación actual y nuevos enfoques para dar viabilidad a la infraestructura hídrica. Gestión y Política Pública, 28(1), 3–37. https://doi.org/10.29265/gypp.v28i1.551

- Dunlap, A. (2018). Counterinsurgency for wind energy: The Bíi Hioxo wind park in Juchitán, Mexico. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(3), 630–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1259221

- Echeagaray, B. L. (1957). La cuenca del Grijalva-Usumacinta a escala nacional y mundial. Secretaria de Recursos Hidráulicos.

- Ezcurra, E., Barrios, E., Ezcurra, P., Ezcurra, A., Vanderplank, S., Vidal, O., Villanueva-Almanza, L., & Aburto-Oropeza, O. (2019). A natural experiment reveals the impact of hydroelectric dams on the estuaries of tropical rivers. Science Advances, 5(3), eaau9875. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau9875

- Ferguson, J. (2012). Structures of responsibility. Ethnography, 13(4), 558–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138111435755

- Folch, C. (2013). Surveillance and state violence in Stroessner's Paraguay: Itaipú hydroelectric dam, archive of terror. American Anthropologist, 115(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2012.01534.x

- García García, A. (2013). Las inundaciones fluviales históricas en la planicie tabasqueña. In E. Kauffer (Ed.), Cuencas en tabasco: Una visión a contracorriente (pp. 61–99). CIECAS.

- Glassman, J. (2010). Bounding the Mekong: The Asian Development Bank, China and Thailand. University of Hawai’i.

- Grill, G., Lehner, B., Lumsdon, A., MacDonald, G., Zarfl, C., & Liermann, C. (2015). An index-based framework for assessing patterns and trends in river fragmentation and flow regulation by global dams at multiple scales. Environmental Research Letters, 10(1). http://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/1/015001

- Harvey, P., Jensen, C. B., & Morita, A. (2017). Introduction: Infrastructural complications. In P. Harvey, J. C. Bruun, & A. Morita (Eds.), Infrastructures and social complexity: A companion (pp. 1–22). Routledge.

- Harvey, P., & Knox, H. (2015). Roads: An anthropology of infrastructure and expertise. Cornell University Press.

- Hetherington, K., & Campbell, J. (2014). Nature, infrastructure, and the state: Rethinking development in Latin America. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology, 19(2), 191–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12095

- Hirsch, P. (2010). The changing political dynamics of dam building on the Mekong. Water Alternatives, 3(2), 312–323. http://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol3/v3issue2/95-a3-2-18/file

- Horton, A. J., Triet, N. V., Hoang, L. P., Heng, S., Hok, P., Chung, S., Koponen, J., & Kummu, M. (2022). The Cambodian Mekong floodplain under future development plans and climate change. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 22(3), 967–983. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-967-2022

- Horton, A., Nygren, A., Diaz Perera, M. A., & Kummu, M. (2021). Flood severity along the Usumacinta River, Mexico: Identifying the anthropogenic signature of tropical forest conversion. Journal of Hydrology X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydroa.2020.100072

- Howe, C., Lockrem, J., Appel, H., Hackett, E., Boyer, D., Hall, R., Schneider-Mayerson, M., Pope, A., Gupta, A., Rodwell, E., & Ballestero, A. (2016). Paradoxical infrastructures. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 41(3), 547–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915620017

- Hunt, G., Samuelsson, M., & Higashi, S. (2018). Broken pillars: The failure of the Nakai Plateau livelihood resettlement program. In B. Shoemaker, & W. Robichaud (Eds.), Dead in the water: Global lessons from the World Bank’s model hydropower project in Laos (pp. 106–140). Wisconsin University Press.

- INEGI [Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía]. (2018). Estados Unidos México: Presas. Geoestadístico Nacional.

- International Energy Agency. (2016). Key world energy statistics 2015. OECD.

- International Hydropower Association [IHA]. (2019). Hydropower status report. https://www.hydropower.org/publications/status2019.

- Johns, F. (2015). On failing forward: Neoliberal legality in the Mekong River Basin, Cornell International Law Journal, 48(2), 347–383. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol48/iss2/3

- Kaika, M. (2006). Dams as symbols of modernization: The urbanization of nature between geographical imagination and materiality. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 96(2), 276–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2006.00478.x

- Kallianos, Y., Dunlap, A., & Dalakoglou, D. (in press). Introducing infrastructural harm: Rethinking moral entanglements, spatio-temporal modalities, and resistance(s). Globalizations.

- Käkönen, M. (2020). Fixing the fluid: Making resources and ordering hydrosocial relations in the Mekong Region. Doctoral dissertation. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-6316-5.

- Käkönen, M., & Kaisti, H. (2012). The World Bank, Laos and renewable energy revolution in the making: Challenges in alleviating poverty and mitigating climate change. Forum for Development Studies, 39(2), 159–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2012.657668

- Käkönen, M., & Thuon, T. (2019). Overlapping zones of exclusion: Carbon markets, corporate hydro-power enclaves and timber extraction in Cambodia. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(6), 1192–1218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1474875

- Kauffer, E. (2013). Represas en la cuenca transfronteriza del río Usumacinta: Un conflicto crónico. In E. Kauffer (Ed.), Cuencas en Tabasco: Una visión a contracorriente (pp. 101–132). CIECAS.

- Khagram, S. (2004). Dams and development: Transnational struggles for water and power. Cornell University Press.

- Klein, P. T. (2015). Engaging the Brazilian state: The Belo Monte dam and the struggle for political voice. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 42(6), 1137–1156. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.991719

- Kondolf, G., Rubin, Z., & Minear, J. (2014). Dams on the Mekong: Cumulative sediment starvation. Water Resources Research, 50(6), 5158–5169. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR014651

- Kong, B. (2021). Domestic push meets foreign pull: The political economy of Chinese development finance for hydropower worldwide, GCI Working Paper, Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2021/07/GCI_WP_017_FIN.pdf

- Larkin, B. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522

- Lee, C. K. (2018). The specter of global China: politics, labor, and foreign investment in Africa. The University of Chicago Press.

- Ley, L., & Krause, F. (2019). Ethnographic conversations with Wittfogel's ghost: An introduction. Environment and Planning C, 37(7), 1151–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419873677

- Linton, J. (2010). What is water? The history of a modern abstraction. UBC Press.

- Linton, J., & Budds, J. (2014). The hydrosocial cycle: Defining and mobilizing a relational-dialectical approach to water. Geoforum, 57, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.10.008

- McCarthy, J. (2015). A socioecological fix to capitalist crisis and climate change? The possibilities and limits of renewable energy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 47(12), 2485–2502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15602491

- McCully, P. (2001). Silenced rivers: The ecology and politics of large dams. St. Martin’s Press.

- Merme, V., Ahlers, R., & Gupta, J. (2014). Private equity, public affair: Hydropower financing in the Mekong Basin. Global Environmental Change, 24, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.11.007

- Middleton, C. (2018). Branding dams: Nam Theun 2 and its role in producing the discourse of ‘sustainable development’. In W. Robichaud, & B. Shoemaker (Eds.), Dead in the water: Global lessons from the World Bank’s model hydropower project in laos (pp. 271–292). Wisconsin University Press.

- Middleton, C. (2022). The political ecology of large hydropower dams in the Mekong Basin: A comprehensive review. Water Alternatives, 15(2), 251–289. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol15/v15issue2/668-a15-2-10/file

- Milne, S. (2015). Cambodia’s unofficial regime of extraction: Illicit logging in the shadow of transnational governance and investment. Critical Asian Studies, 47(2), 200–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2015.1041275

- Molle, F., Mollinga, P., & Wester, P. (2009). Hydraulic bureaucracies and the hydraulic mission: Flows of water, flows of power. Water Alternatives, 2(3), 328–349. http://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/allabs/65-a2-3-3/file

- MRC [Mekong River Commission]. (2017). The Council Study. The study on the sustainable management and development of the Mekong River Basin, including impacts of mainstream hydropower project. Vientiane.

- Nygren, A. (2016). Socially differentiated urban flood governance in Mexico: Ambiguous negotiations and fragmented contestations. Journal of Latin American Studies, 48(2), 335–365. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X15001170

- Nygren, A. (2018). Inequality and interconnectivity: Urban spaces of justice in Mexico. Geoforum, 89, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.015

- Nygren, A. (2021). Water and power, water’s power: State-making and socionature shaping volatile rivers and riverine people in mexico. World Development, 146), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105615

- Randle, S., & Barnes, S. (2018). Liquid futures: Water management systems and anticipated environments. WIRES Water, 5(2), e1274. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1274

- Räsänen, T., Varis, O., Scherer, L., & Kummu, M. (2018). Greenhouse gas emissions of hydropower in the Mekong River Basin. Environmental Research Letters, 13(3). https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aaa817

- Ribot, J. (2014). Cause and response: Vulnerability and climate in the Anthropocene. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(5), 667–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.894911

- Richter, B. D., Postel, S., Revenga, C., Scudder, T., Lehner, B., Churchill, A., & Chow, M. (2010). Lost in development’s shadow: The downstream human consequences of dams. Water Alternatives, 3(2), 14–42. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/volume3/v3issue2/80-a3-2-3/file

- Rodgers, D., & O'Neill, B. (2012). Infrastructural violence: Introduction to the special issue. Ethnography, 13(4), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138111435738

- Schindler, S., Fadaee, S., & Brockington, D. (2019). Contemporary Megaprojects: An introduction. Environment and Society, 10(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2019.100101

- Schulz, C., & Adams, W. M. (2019). Debating dams: The World Commission on Dams 20 years on. WIRES Water, 6, https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1369

- Scudder, T. (2019). Large dams: Long term impacts on riverine communities and free flowing rivers. Springer Nature.

- Siciliano, G., Del Bene, D., Scheidel, A., Liu, J., & Urban, F. (2019). Environmental justice and Chinese dam-building in the global South. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 37, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.04.003

- Sneddon, C. (2015). Concrete revolution: Large dams, Cold war geopolitics, and the US Bureau of Reclamation. University of Chicago Press.

- Sovacool, B. (2021). Who are the victims of low-carbon transitions? Towards a political ecology of climate change mitigation. Energy Research & Social Science, 73), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.101916

- Sovacool, B., & Walter, G. (2019). Internationalizing the political economy of hydroelectricity: Security, development and sustainability in hydropower states. Review of International Political Economy, 26(1), 49–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2018.1511449

- Swyngedouw, E. (2015). Liquid power: Contested hydro-modernities in twentieth century Spain. MIT Press.

- Taylor, M. (2015). The political ecology of climate change adaptation: Livelihoods, agrarian change and the conflicts of development. Routledge.