ABSTRACT

Commercialization via value-chain agriculture, under which small farmers often collaborate with big companies, has become a prominent development strategy across Africa. Often framed in win-win terms, the dark sides of such projects (e.g. project failure, related losses) are often sidelined in both academic and practitioner discourses on agricultural commercialization. Informed by a collaborative ethnography of a failed value-chain agriculture project in Ghana, this paper seeks to contribute to a better understanding of how farmers, agribusiness companies, and development organizations engage with and shape commercialization processes, and how those most affected – farmers and their communities – experience often risky and conflict-prone ventures. In contrast to the win-win-rhetoric adopted by funders and corporate partners in such projects, we foreground the uneven distribution of risk and sacrifice/losses between farmers, communities, and corporate partners; the socially and materially disruptive nature of commercialization projects for host communities; and the clashes between a planner’s view of the world and the environmental realities of commercialization.

1. Introduction

‘Commercialization’ has been a recurrent policy trope in the recent history of African agriculture. Ranging from colonial-era efforts to ‘improve’ smallholder farming and pastoralism (while dispossessing people at the same time), to post-colonial experiments in state farms, contract farming schemes and mechanization, commercialization as a transformative process can entail that ‘smallholder farm households shift from semi-subsistence agriculture to production primarily for the market’ (Poulton, Citation2017, p. 4). Alternatively, it entails being ‘complemented or replaced by medium and – large-scale farm enterprises that are predominantly or purely commercial in nature’ (Poulton, Citation2017). At various moments in history, it has been pushed as the route to ‘development’ by both colonial and postcolonial governments and their commercial allies (Baglioni & Gibbon, Citation2013). After agricultural commercialization was largely unsuccessfully left to the workings of ‘the market’ as part of the structural adjustment programmes of the 1980s and 1990s, it received a comeback in the early 2000s in the form of what McMichael (Citation2013) calls ‘value-chain agriculture’ (hereafter: VCA). The approach incorporates both academic and practitioner takes on value and supply chains, contract farming models,Footnote1 and various forms of lending instruments. Often steered by hybrid governance models such as public-private partnerships or multi-stakeholder networks, it quickly became a staple in development programmes across the Global South (Amanor, Citation2019; Niebuhr, Citation2016; Werner et al., Citation2014).

At first sight, VCA could be viewed as only the latest harbinger of commercialization in the chequered and often oppressive history of agricultural modernization in Africa. But besides comprising new elements such as hybrid modes of governance and novel micro- and meso-level thinking about how to engineer regional and global market connections, it also differs from earlier approaches with regard to another dimension: while earlier attempts aimed at reducing rural poverty and ‘backwardness’ by promoting production (‘modern’ technology adoption, increasing productivity, promotion of extension services), contemporary VCA projects address farmers not as merely ‘producers’ that should enter the ‘modern’ world of farming, but also as ‘subjects’ that should view farming as a business and usually need to be nudged to do so (Ouma, Citation2015). As such, compared to older contract farming models, VCA can be viewed as a more intrusive and comprehensive political technology of commercialization (McMichael, Citation2013, p. 671). Because it seeks to enrol farmers and nature more firmly into the circuits of capital, the often merely formal subsumption of smallholder farmers of earlier periods of agricultural commercialization is reengineered towards a real subsumption (McMichael, Citation2013, p. 675). In other words, while African farmers in the past retained ‘considerable autonomy in shaping the material character, organization, and management of production’ (Boyd & Prudham, Citation2017, p. 878), the tight control and surveillance regime of VCA (quality standards, certification mechanisms, ‘mindset changing’ training sessions etc.) further intensifies the labour process and takes away some of that autonomy.

Despite the fact that many VCA projects were started since the early 2000s by governments, development institutions, and the private sector across rural Africa, they have received little critical scrutiny with regard to moments of crisis, collapse, and ruination, as well as their differentiated impacts on the farmers, workers and communities enrolled in often-risky endeavours.Footnote2 Rather, development organizations, agribusiness and state-players usually frame VCA in win-win terms ‘as a benign facilitator of agricultural productivity and rural income’ (McMichael, Citation2013, p. 627). However, classic studies on earlier rounds of agricultural commercialization in Africa remind us for the need to attend to the crises moments of such projects and the ruins left behind by these (Amanor, Citation1999; Coulson, Citation2015; Hagedorn & Scott, Citation1981). Moments of crisis, for instance, can be conflicts about land or between farmers and businesses about the surplus generated, while ruins can be conceptualized as the ‘blasted landscapes’ (Tsing, Citation2015, p. 158) that capitalist valorization projects leave behind after divestment. This can include lost livelihood opportunities due to altered agrarian landscapes, enduring social conflict or other ‘durabilities of duress’ (Stoler, Citation2008, p. 192) that capitalist ‘formations produce as ongoing, persistent features of their ontologies’ (Kimari & Ernstson, Citation2020; Stoler, Citation2008). Or, in other words: ‘[W]ho remains with the risks, and who is left to pay the debts, becomes acute when some partners leave' (Kaarhus Citation2018, p. 138).

We address these lacunae by revisiting one of the most prominent value chainprojects in Ghana, which has been at the forefront of VCA in Africa since the early 2000s. We argue that a focus on ‘dark sides’ (see also Werner, Citation2019) reveals a number of things about ‘commercialization via value-chain agriculture’, in which small farmers often collaborate with big companies: the uneven distribution of risk and sacrifice; the socially and materially disruptive nature of commercialization; and clashes between a planner’s view of the world and the environmental realities of commercialization.

We contribute to agricultural commercialization debates in a number of ways. We first seek to nurture a better understanding of how farmers, agribusiness companies and development organizations engage with and shape commercialization processes, and how those most affected – farmers and their communities – fare under these. Second, we demonstrate that value chain projects are poised to incorporate previously ‘un-chained’ farmers and natures deeper into market relations and logics may fail to do so due to ontological cleavages between ‘value-chain agriculture in theory’ and the social and ecological realities of farming in particular places. Like contract farming, VCA can be considered ‘an instrument to impose capitalist discipline for the exploitation of land, labour and nature’ (Oliveira et al., Citation2020, p. 5). However, as we will show, it may also fail to ‘“impose […] its own order” on smallholdings (van der Ploeg, cited in McMichael, Citation2013, p. 674)'. Besides placing crisis, collapse and ruins as ontic moments firmly in debates on agricultural commercialization via VCA (and thus challenging donor narratives and expert discourses which side-line issues such as bankruptcy, failure, loss and decline), we offer a distinct methodological contribution: a triangulating, collaborative ethnography. Building on Burawoy’s (Citation2003) notion of the ‘revisit’, we combine the insights of three researchers who have done independent research on the same case study, but who markedly differ in terms of their research periods, foci, theoretical and methodological approaches, as well as positionalities. We enrich data from our original research period (2008–2012) with data from a less extensive but collectively planned revisit in 2017 (plus one online interview in 2018). We opted for this approach because we are convinced that collaborative research efforts over long periods of time are needed in order to acquire a ‘careful understanding of how places and livelihoods have been transformed at the nexus of development as capitalism and development as intervention’ (Bebbington, Citation2003, p. 306; see also Ponte & Brockington, Citation2020). This allows us to offer a truly forensic account of why the most prominent commercial agriculture project of the 2000s in northern Ghana has failed and what ruins it left behind. Eventually, our collective account of the failed promises of VCA contradicts the widely held assumption in market-oriented development circles that contract farming schemes and associated value chain interventionsFootnote3 are fundamentally symmetrical risk-sharing arrangements (Brüntrup et al., Citation2018).

The paper proceeds as follows. We shall first briefly sketch the rise of VCA in Ghana and situate our case study accordingly. In order to study the complex dynamics that underpin crisis, collapse and ruins as ontic states of commercialization, we have adopted a triangulating, collaborative ethnography, which we will pin down in section 3. We then introduce our case study in section 4, before we root the collapse of our case study of agricultural commercialization in a series of accumulated crises. In section 6, we engage with the ruins that commercialization via VCA left behind in northern Ghana.

2. Agricultural commercialization’s new clothes: the rise of value-chain agriculture in Ghana

The expansion of global food chains, backed up by structural adjustment programmes and the rise of market-oriented agricultural policies, has led to new agricultural frontiers in Africa since the late 1980s. The rise of new agricultural spaces emerging in the 1980s and 1990s, from green beans production in Kenya to pineapple production in Ghana, was largely supported by export promotion strategies of the structural adjustment era and its laissez-faire approach towards markets (Ouma, Citation2015). From the early 2000s onwards, the increasing proliferation of value chain thinking, combined with a renewed interest in contract farming models (including outgrower schemes)Footnote4 and agricultural financing arrangements (Eaton & Shepherd, Citation2001), paved the way for more interventionist takes on transforming agriculture into a ‘modern business’. In addition, as Baglioni and Gibbon (Citation2013) note, the growing dissatisfaction with the phenomenon of large-scale land acquisitions since the late 2000s has reinforced those voices who have argued that VCA, underpinned by inclusive agribusiness-farmer linkages, should be the future of farming in much of Africa.

Ghana is an interesting example in this regard. Since the late 1980s, the country made repeated attempts to reform its land sector, instituted export processing zones, provided tax reliefs and infrastructure to attract agro-based companies to help modernize its agricultural sector and improve the lives of the small farmers (Addo & Marshall, Citation2000). Since at least the early 2000s, the state, in alliance with ‘development partners’, has promoted ‘modern’ value chains, nucleus outgrower arrangements, and other forms of contract farming systems through a variety of initiatives (for a detailed overview, see Niebuhr, Citation2016, p. 54). Ghana now boasts of several global value chains for commodities such as pineapples, mangoes, papaya, cashew, and yams, having slightly diversified its export base away from colonial commodities such as cocoa and palm oil. Development players and the state have also promoted the development of regional value chains for several other food crops such as cassava (Amanor, Citation2019; Ouma, Citation2015).

While some early observers have painted outgrower schemes – a central pillar of VCA – as theatres of exploitation (Amanor, Citation1999; Pérez Niño, Citation2016; Singh, Citation2002; Watts, Citation1994) – in today’s mainstream development discourse they are largely presented as the panacea to overcoming marketing and food safety challenges in both domestic and global value chains (Brüntrup et al., Citation2018). As was the case for the first generation of contract farming schemes in the 1960s–1970s, they are said to offer market access, technology transfer, and increased income for farmers (nowadays re-imagined as ‘upgrading’) (Amanor, Citation2019; Werner et al., Citation2014). But in the early twenty-first century age of value-chain thinking, they also claim to promise a reliable and traceable supply of commodities to consumers.

The overall enthusiastic embrace of commercialization via value chains among development researchers and practitioners has often tended to be blind to the ‘darks sides’ (Phelps et al., Citation2018) of farmer-business linkages. There is a wide range of phenomena we could qualify as ‘dark sides’ in the context of African VCA, from power asymmetries between different value chain players; to various producer-risks related world market dynamics; to the threat of indebtedness or moments of land and seed dispossession (Amanor, Citation2019; Bolwig et al., Citation2010; McMichael, Citation2013).

In the remainder of this paper, we shall single out three important dark sides that rarely attract scholarly attention: the nexus between outgrower livelihoods and corporate crises, the actual collapse of VCA projects, and the ruins they leave behind. Concerning the latter, Tsing (Citation2015, p. 6) notes: ‘When its singular asset can no longer be produced, a place can be abandoned. The timber has been cut; the oil has run out; the plantation soil no longer supports crops. The search for assets resumes elsewhere’. However, while affected companies usually can write off losses and move on, it is often local farmers involved in such commercial asset-making projects who may continue to struggle with the ruins these left behind.

3. Crisis, collapse and ruins: studying commercialization’s socio-economic and -environmental complexities

We seek to contribute to a better understanding of how different actors (e.g. farmers, agribusiness companies and development organizations) engage with and shape commercialization processes, how those most affected – farmers and their communities – experience these, and how commercialization projects may fail to reformat farmers and nature alike in the image of the market. The moments of crisis, collapse and ruination that shoot through these highly complex processes are difficult to study from the position of single researching subject and within the confines of a single study (Fraser et al., Citation2014; Murray et al., Citation2011). Often, crises – potentially leading to collapse – unfold over a longer period of time. Crises are also often conflict-ridden and layered processes of multiple determinations, often lurking beneath the surface of the visible socio-ecological landscape. The crisis of one group of actors in a value chain project (e.g. low wages that do not allow a humane reproduction) does not necessarily represent a crisis of another group, but crisis can quickly proliferate as a dynamic and social category (e.g. the financial problems of a company can affect its service provision to outgrowers). Likewise, ruins, as the economic, social, affective and ecological remains of capitalist valorization projects, often evade the gaze of researchers even though these are what people on the ground have to live with (Stoler, Citation2008; Tsing, Citation2015). What further complicates research on the dark sides of VCA is that associated projects are power-laden and heterogeneous assemblages, in which actors with different power endowments, economic rationalities and ontological orders (including regimes of property) become articulated (Tsing, Citation2012). At the same time, those studying such projects are socially positioned in differentiated ways vis-a-vis these articulations. This usually results in research strategies that either focus on the internally differentiated categories of capital (e.g. managers and shareholders), or on labour (e.g. workers and smallholder farmers), or on the communities where labour makes a living. In turn, this makes it difficult to write comprehensive accounts of the dynamics that actively shape and reshape the practices of and relations between capital and labour in a particular setting. Even if researchers have the intention to come to terms with dynamics in both social fields symmetrically, they often sit uncomfortably on the fence between actors with often opposing interests (see also Salverda, Citation2021). Any researcher perceived to be too close to the management of a company can quickly result in losing trust among workers or farmers within a certain value chain and the other way around. This affects analysis in terms of.

Inspired by the work of sociologist Michael Burawoy (Citation2003) and other ‘re-studies’ in agrarian political economy (e.g. Ponte & Brockington, Citation2020), we propose the boundary-spanning research strategy of triangulating, collaborative ethnography that combines a so-called ‘punctuated’ with the ‘heuristic revisit’ (Burawoy, Citation2003, p. 669). A punctuated revisit advances ‘the idea of long-term field research in which ethnographers, either as individuals or as a team, revisit a field site regularly over many years […] with a view to understanding historical change and continuity’ (Burawoy, Citation2003, pp. 669-f.), while a heuristic revisit ‘appeals to another study-not always strictly ethnographic and not necessarily of the same site but of an analogous site-that frames the questions posed, provides the concepts to be adopted, or offers a parallel and comparative account’ (Burawoy, Citation2003, p. 671).

We adapt this approach to come to terms with the political, socio-economic and environmental complexities that characterize the dark sides of commercialization via VCA, triangulating differently situated research accounts. Discrepancies between two accounts of the same case study ‘can be attributed to differences in: (1) the relation of observer to participant, (2) theory brought to the field by the ethnographer, (3) internal processes within the field site itself, or (4) forces external to the field site’ (Burawoy, Citation2003, p. 645).

Therefore, we combined three different theoretical and methodological approaches used by three different researchers working on the same case study. Our research periods, focus and positionalities are also markedly different (see ). For instance, the first one of us (Ouma, 2015, p. 176) adopted a science and technology studies inspired view of markets and organizations during his original research. This led him to differentiate between the everyday crisis of the commodity form (Tsing, Citation2008) and Crises. The former i.e. crisis, refers to a situation where the heterogeneous engineering of markets faces daily challenges and controversies, such as when a load of mangoes fails a food safety test or when buyers in Europe suddenly cancel their orders. The latter i.e. Crises, are moments when the drawing together of heterogeneous elements becomes increasingly difficult or is no longer possible, leading to the breakdown and disintegration of particular market socio-technical assemblages, such as when mango trees do not produce fruits. The other two of us adopted a more classic agrarian political-economy perspective that focussed on the complex social and socio-ecological embeddedness of mango farmers’ economic practices (Iddrisu, Citation2012; Yaro and Tsikata, Citation2013; Tsikata and Yaro Citation2014). Merging these two perspectives and their associated epistemologies and methods enabled a triangulated, comprehensive reconstruction of the multiple dynamics of crises and change at play in the commercialization project that we studied. The work of Burawoy is also useful, because it strives to situate the concrete into its extra-local, historical, and relational context without resorting to simple global–local dichotomies or causal determinisms (Burawoy, Citation1998, p. 21) – an objective well-aligned with that of critical agrarian studies (Akram-Lodhi et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. Collaborative ethnography profile

While we triangulate earlier published and unpublished work on the case study, we back up our reconstruction by findings generated via a collectively undertaken re-visit by Iddrisu and Yaro in 2017, where around 20 additional formal and informal interviews with farmers and workers in the project area, as well as with existing and former corporate staff were conducted.Footnote5 As in other cases where researchers with different positionalities and approaches have joined forces (e.g. Vira & James, Citation2011), we believe that our work has produced productive friction.

In a broader sense, the boundary-spanning exercise presented here is sympathetic to the project of those scholars who have argued that we need to better incorporate the traditional concerns of livelihoods research, e.g. poverty, exclusion, territorial structures, assets etc., with those of research on global-local economic entanglements (Bebbington, Citation2003; Bolwig et al., Citation2010; Murray et al., Citation2011; Scoones, Citation2009). However, we move beyond this by demonstrating the synergies generated through a boundary-spanning research strategy of three differently positioned researchers engaged with the same case. As part of this endeavour, we understand ethnography as a relational arrangement of sensitizing questions, sites of interest, and different methods of text generation (interviews, document analysis, observations) and analysis in a recursive and reflexive manner in order to come to terms with how actors on the ground – farmers and agribusiness managers – make sense of and navigate crisis dynamics and the ruins they leave behind. This allows us to reconstruct agricultural commercialization processes as multi-layered. Crisis moments and their aftermaths often emerge exactly from this multi-layeredness, the interaction of processes unfolding, and are hard to grasp by a single researcher.

4. The promises of inclusive agricultural commercialization

Policies aimed at developing the agricultural potential of northern Ghana as a poverty alleviation strategy embraced by the state, international organizations and private companies predate the country’s independence in 1957. Earlier attempts to incorporate northern Ghana into what today would be called global commodity chains achieved little in developing the region’s agricultural potential. This included investments in cotton, shea nuts, cereals via state projects such as the Gonja Development Company set up in 1951, and private undertakings such as the British Cotton Growers Association. The failures of these past projects resulted mainly due to the labour policiesFootnote6 of the colonial administration and faulty technical assumptions (Nabila, Citation1972; Plange, Citation1979; Songsore & Denkabe, Citation1995).

Post-colonial attempts have continually targeted the production of raw materials for factories and food for the urban populations. These efforts have been deemed as inadequate for increasing the participation of northern farmers in global commodity markets from which technological progress may diffuse (Yaro and Tsikata, Citation2013; Ouma, Citation2015). Typifying the ‘sleeping giant’ imagined by the World Bank (2009), the region is perceived to have vast areas of ‘idle’ and ‘unused’ land – a common trope in contemporary (and colonial) narratives of agricultural frontier markets across the Global South – even though the realities of land use and ownership in many places suggests otherwise (Yaro and Tsikata, Citation2013).

The investment of Organic Fruit Limited (OFL) has been the first harbinger of VCA in northern Ghana. While it may be quickly lumped together with the later wave of large-scale land deals that took place in Ghana and elsewhere in Africa from 2007, the project is more intimately linked to the rise of VCA in the early 2000s. The project sought to bring lucrative organic mango farming to farmers who previously had never been involved in commercial tree cultivation. Mango had grown wild and ‘by default’, not by cultivation in Ghana’s northern parts. The provision of technology, access to global markets and good corporate social responsibilities that did not distort customary land tenure arrangements and local food production systems were key selling points of the project’s architects, who managed to pitch their project to donors and policy-makers as one of inclusive commercialization.

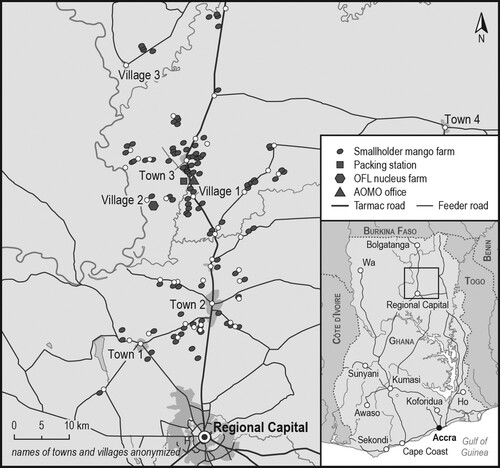

OFL was incorporated in 1999 into SENCO* Ghana Limited as the majority shareholder and has its headquarters in a small village near the regional capital* (see ). Its main shareholder had a keen interest in developing northern Ghana, to which he had close historical ties (Ouma, Citation2015). He teamed up with other shareholders, as well as a prominent local chief to set up OFL. The developmental appeal of the project was its collaborative model with local farmers, using a nucleus-outgrower scheme for organic mango production. The business model seemed to avoid the socio-ecological problems of the plantation model and instead targeted a niche market for a ‘noble product’ i.e. organic mangoes.

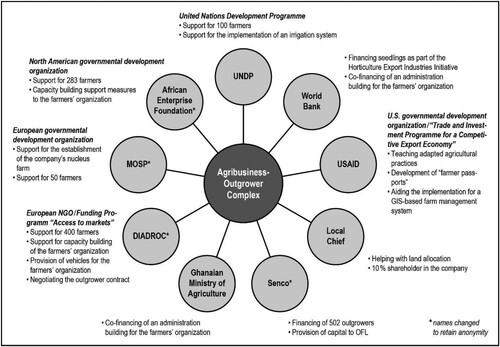

In the beginning, state, development organizations’ and community perceptions of the initiative were overwhelmingly positive. It promised to provide income and employment to farmers and workers in one of most deprived areas in Ghana and to open it up for further investments. This promise was crucial for bringing in other actors. From 2001 onwards, the company subsequently received substantial financial support for the establishment of its nucleus farm, the formation of numerous outgrower groups and building of a processing facility. Contributing organizations in these regards included the European NGOs MOSP* and DIADROC*, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the African Enterprise Foundation*, the Ministry of Food and Agriculture, the World Bank, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and even local chiefs (see ).

Farmers queued up to join the project. As outgrowers, farmers could only farm one acre of the organic mango and were encouraged to form groups. The groups were responsible for clearing the land (e.g. stumping of trees and weeding), planting of the mango seedlings, fencing the plots, and watering of the plants. OFL on its part supplied the tools, water tanks, seedlings, field extension services, and transportation of inputs through interest-free credit arrangements. The farmers had to repay the credit via deductions from fruit sales in national or international markets. The process was mediated by the Association of Organic Mango Outgrowers (AOMO)*, founded in 2001, and supported with more donor money from 2004 onwards.

By 2010, over 1295 outgrowers (122 of which were women) convinced by the promises of VCA had joined the project. While this was less than envisioned by the company, for many development organizations and state players, the scheme, then spread across 44 villages (), had become an example for inclusive agricultural commercialization.Footnote7 By 2017, however, the enthusiasm for the project had drastically decreased. Initially, the outgrowers, who would largely plant the Kent mango variety, were promised that after a gestation period of 3–4 years, their trees would bear fruits, reaching full productivity in year 10. In reality, they had repeatedly experienced stagnant or even decreases in mango yields and the company had to significantly downsize its operations and even abandon contractual promises. Both company staff and farmers dropped out of the project. Indeed, a view behind the curtain reveals a bumpy road to ‘world market integration’. The project had slowly manoeuvred into an economic and political crisis that resulted from an accumulation of factors, leaving behind different kinds of ruins in different corners of the outgrower scheme.

5. The dark sides of agricultural commercialization in northern Ghana

5.1. Mango trees as costly and contested commodities

Proponents praise outgrower schemes for not disenfranchising local people of their landed resources while allowing them to benefit from market connections (Brüntrup et al., Citation2018; Eaton & Shepherd, Citation2001); this is also the main argument to promote this form of agricultural commercialization. Empirical evidence from several countries in the Global South, however, counters these assertions (Amanor, Citation1999; Carney, Citation1988; Hall et al., Citation2017; Pérez Niño, Citation2016; Watts, Citation1994). The collective findings in our own case study align with various points made in this literature, including the conflict-ridden transformation of land into resources for export-production, the politics of labour, the differentiated outcomes of commercialization, which often benefit better-off, male farmers, as well as the uneven distribution of risks between companies and farmers.

As a land-based activity, organic mango farming required that both the company and farmers secured contiguous lands with enough tenure security. When the project started in 1999, ‘carving out’ the nucleus plantation in village 2 from existing relations of land tenure quickly became a matter of political contention that could have sealed the fate of the project at an early stage. As Yaro and Tsikata (Citation2013) found out, the nucleus farm located in village 2 (cf. ) is on land that was forcibly given to the company by the Paramount Chief of the Dagomba people (the Ya-Naa), without passing through negotiation stages with the community members and the village chief and his sub-chiefs.Footnote8 This severed the relationship between the company and the community, which had lost its major source of livelihood. A poor appreciation of local cultures and poor engagement of local communities in land negotiations plunged the company into a risky, potentially toxic investment. It led to the breakdown of traditional relations of respect between village chiefs, divisional chiefs and the Ya-Naa as the top-down allocation of local land violated custom and tradition. This created a tense atmosphere. Bushfires repeatedly destroyed farms in village 2 from 2009 onwards. Our corporate interviewees mainly attributed fires to the ‘laziness’ of local farmers, disregarding the reality that the these were actually a form of resistance against land enclosures mobilized by alienated community members.

The ever-looming issue of local resistance against mango farm enclosures made the development of an outgrower scheme around the nucleus farm of the company geographically impossible. Thus, the company resorted early to contract more distant communities. The need to only enrol those communities where the land question could easily be solved resulted in significant diseconomies of scale since the costs associated with the supply of water and other services to outgrowers rose sharply. Similarly, the establishment of outgrower farms in other communities by farmers themselves were fraught with contentions over land use. Communities were divided with regard to the use of farmlands for mango cultivation, which was new to the area. The planting of mango trees effectively was equal to laying a long-term and thus private claim on land in a setting with communal land ownership. Planting the trees also resulted in the enclosure of communal lands, the destruction of indigenous economic trees such as shea and locust bean, and a restriction of the movements of animals. Contrary to the classic doctrine that asks outgrowers to use their own lands for production, the scheme preferred relatively contiguous large areas shared by groups of outgrowers to increase economies of scale and fight bush fires more effectively. These block farms were released to the outgrower groups by village chiefs and large farmers who had been convinced by the project. Substantial negotiations were undertaken in some communities, with significant implications for future land tenure relations. Many farmers would ask themselves how they could be sure that mango trees, whose fruits will only be available in a distant future, would bring them better returns than trees such as shea that were sacrificed for the block farms. Shea trees are a gendered resource (Chalfin, Citation2004). In contrast to shea trees, which benefit women, few women participated in mango farming, leading to a new gendered redistribution of income and opportunities in the area (Tsikata and Yaro Citation2014). The case highlights how knowledge of local customs and social relations – demonstrated by both the work of Iddrisu and Yaro – brings the differentiated outcomes of commercialization and its politics to surface.Footnote9

5.2. Mango trees and the politics of labour

As a key pillar of VCA, contract farming is lauded for guaranteeing farmers’ autonomy with regard to control over lands and labour, thereby ensuring equity, independence and livelihood enhancement (Baglioni & Gibbon, Citation2013). However, several studies show how the ‘autonomy’ of the farmers over both land and labour is severely curtailed through the corporate control of the process of production, conditions of enrolment, determination of prices, and the labour exactions on family members (Amanor, Citation1999; Citation2019; Watts, Citation1994). Contract farming is documented for creating conditions for labour exploitation by capital, resulting in the transformation of smallholders into ‘disguised workers’, ‘a self-employed proletariat’ and ‘quasiemployees’ (Pérez Niño, Citation2016, p. 1787). At the same time, smallholder farmers may adversely incorporate family members into such schemes of value extraction in order to sustain practices of accumulation (Singh, Citation2003).

While such processes may happen in many contexts, we cannot assume that they take root or can be sustained wherever VCA touches ground. In our case, joining the mango project was perceived as risky from the very beginning among many farmers, who were either sceptical to join or refused to release lands to others. In 2008, the assistant outgrower manager remarked:

(…) it is a new idea altogether in the north here. It is not that there are no tree crops for export, there are tree crops for export but these tree crops are not planted.

In retrospect, many outgrowers remember the added stress the project put on family resources, as revisits in 2017 by Iddrisu and Yaro revealed:

(…) Initially, many family members assisted but as they realized that it was hard work, they preferred to go to food crop farms or give excuses. Before we established the farm, we mobilized many people and removed all the trees including economic trees because we were sure the mangoes will replace the losses. (…) Also, we had conflicts with our neighbours for allowing their livestock onto our fields in the dry season. (…). After all these years, the amount of labour my family and I have put into this dead farm could have been used to grow food crops for the market. (outgrower 1 village G.)

The mango trees caused a lot of problems within families. First was the difficulty of getting other family members to provide labour (…). Secondly, our wives were not happy that we were cutting down shea trees to plant mangoes. (former AOMO chairman in town 3, 2017)

I can remember when they (OFL) came and said they wanted to start these mango farms here, my father told them mangoes will not do well here. But they refused and now we can all see the results. They (the farmers) thought they could use the money from the mango to become rich. I can say they have even become poorer. Look at Mr. G., he was doing well before he diverted all his time and resources to this mango thing. Now, I pity him. (outgrower in town 3, 2017)

5.3. Fruitless mango trees and the flawed simplifications of expert agriculture

One of the recurrent core arguments for outgrower schemes is that farmers would receive scientific assistance by experts, assuming that the latter have some superior form of agricultural knowledge (Baglioni & Gibbon, Citation2013). Such experts – consultants hired by OFL’s mother company – also came up with the promising projections that helped enrol local farmers into a hitherto unknown venture and shaped the temporalities of contracting. Existing historical documents and interviews assembled by Ouma (Citation2015) show how positively these experts imagined future returns at the beginning of the project. The hired consultants projected that the mango trees would yield in the fifth year after planting, starting with about 300 kg per acre. This would steadily increase until the tenth year, when the yields would total more than 6000 kg per acre.Footnote10 It was also assumed that irrigation would only be required for the first three years of production, and could be largely done by hand. The architects of the project calculated that the outgrowers could pay back their debts after the fifth year and from the eighth year onwards, they would not have to rely on credit any more but could finance OFL services from their mango income. Within 12–15 years after planting, the credit would have been settled, and with a life span of several decades, the mango trees would eventually become a long-term source of income.

This calculation was catalytic and the project was up scaled very quickly. However, due to a combination of the resource and labour politics outlined earlier, and the fact that the mango trees due to microclimatic particularities (climate, wind, soil/water) behaved differently than expected, the initial goal of 2000 outgrowers (producing 20,000 mt of fruits per annum by 2015) was never reached. As Ouma (Citation2015), Yaro and Tsikata (Citation2013) and Tsikata and Yaro (Citation2014) showed in great detail, the calculations of the experts rested on flawed assumptions about the growth of new mango trees in a complex Savannah ecosystem. To cite Scott (Citation1998, p. 273): ‘Imported faith and abstraction prevailed […] over close attention to the local context.’ Given the overall reliance on expert knowledge, and a disregard of local particularities, nature could just not be effectively subsumed to the logic of industrial production that even an organic outgrower scheme exhibited.Footnote11 As Ouma (Citation2015, p. 192) noted earlier:

With trees, mistakes in the past are particularly costly (…). Fields cannot be abandoned if the water level or soil quality in a given location is poor. Often, there are also serious constraints with regard to technical manipulation, all the more with organically grown trees, where the range of chemical or even genetic manipulation is limited or forbidden altogether. All this makes trees a kind of spatially fixed capital and precarious commodities at the same time

6. Organic ruins: ‘suffering for nothing', social cleavages and material debris

Scholars of globalized peripheral spaces have repeatedly shown that the ebbs and flows of global capitalism (Bebbington, Citation2003) can leave behind ragged landscapes, in which ruins are made of both broken promises and material debris. In our case, the process of ruination is not rooted in world market dynamics (cf. e.g. Fraser et al., Citation2014; Whitfield, Citation2017), but rather in an accumulation of internal crises linked to the politics of land and labour, as well as the failure to tame nature according to the objectives of the project. However, just like there were divergent views of the future of the mango project among its sceptics and proponents in its early days, it still generated similar divergent views about its future during the revisit of two of our authors in 2017. Farmers who had abandoned their farms due to no yields and the stoppage of supply of water, inputs and technical support from OFL saw a collapsed business. Former AOMO members were not alone in seeing the scheme as a failed project with no future. Some former retrenched workers of the company did so, too. However, farmers whose mangoes still yielded fruits and the few workers remaining with OFL still saw a bright future in domains beyond mango cultivation. Some of these farmers also capitalized on the lowered monitoring capacity of the company to sell some of their produce in the local markets. Also, the heavily downsized management still saw some light at the end of tunnel, e.g. by restructuring the company and venturing into new areas like beekeeping in the nucleus farm and the cultivation of moringaFootnote12 and vegetables, among others.

Despite these glimpses of hope, a transect across the outgrower project largely suggested a landscape of ruins, made up of broken promises, social cleavages and material debris. There were abandoned mango farms by former outgrowers ravaged by bushfires, bushy mango farms with broken water tanks, cemented stands of water tanks removed from their bases and destroyed irrigation tubes. Farmers who had previously toiled to nurture mango seedlings to survive the harsh dry climatic conditions of the north, cleared bushes around to protect the mango farms from fires and fenced their mango farm holdings to prevent intrusion of livestock, were suddenly doing the opposite (see and ).

The project is a sad story. When I drive along the road where some of the farms are located, my heart bleeds over the dead trees and when you get into the pack-house and offices, it is like a cemetery. Most of the workers have left. (online interview former manager, 2018)

(..) before the company came here, I was one of the opinion leaders in this area and not just this village. We stood for the company and our people listened to us. But after all what saw from OFL, I can say we have lost our credibility even among our wives. I can say it will be difficult, if not impossible, to convince anybody in this village to collaborate with any company which comes here to engage us in a similar venture again. (chairman T, interviewed in village 1, 2017)

The educated people who worked with the company got what they wanted. Almost all of them now have houses in the regional capital and live better lives. Where did they get the money from? (Chairman T., village 1)

7. Conclusion

Agricultural commercialization, in general, requires a reordering of social and socioenvironmental relations to meet the profit motives of corporate investors. As a political technology, VCA is an intensification of that rationale insofar as it directly seeks to reformat farmers as subjects of commercialization in a much deeper sense, while often incorporating hitherto unmarketized or at least differently marketized crops, animals and trees into tightly regulated market relations. This article has problematized the proliferation of value chain projects as a new political technology of commercialization in rural Africa. In policy circles, such projects are largely framed as win-wins for both participating farmers and corporate players. However, we showed that these must be scrutinized for their multiple dark sides. We did this for one concrete project in northern Ghana, but our findings point beyond the single case and call upon other researchers to use collaborative efforts and longitudinal studies, including revisits and mixed-methods, to arrive at comprehensive accounts of value-chain agriculture that also come to terms with moments of crisis, collapse and ruination. By doing this, we are able to point out that the real subsumption of farmers and nature envisioned by McMichael (Citation2013), and flagged above, often remains a ‘fallacy of capital’.

Our aggregated analysis reveals that even though the commercialization project under scrutiny started with a promising set of objectives on the side of managers and shareholders, it quickly ran into troubles, and eventually slowly died over a period of several years. A combination of interrelated factors contributed to this trajectory: local power relations that quickly complicated the investor’s plans, struggles over the making of resources and farm labour among outgrowers and miscalculated human-environmental relations by company managers. It is particularly our account of the problem of labour mobilization and the uneven returns flowing back to different subgroups of labour that reaffirms the need to scrutinize global commodity chains not just for the production, enhancement and capture of value, but also for the socially and spatially unevenly distributed monetary and non-monetary risks that come along with the incorporation into new market relations for different actors along the chain. While company personnel may move on after some years, often having lived well from their salaries, especially in the case of expatriate managers, and shareholders of failing companies may write off losses, farmers often have to live with the ruins left behind by failed projects of commercialization. As our case suggests, farmers participating in VCA are often expected to buy into the timescale of companies while the latter are able to leverage time to their advantage. Yet even in successful commercialization projects, participation may grant certain actors new freedoms, but simultaneously comes along with social risks and actual material losses as the cases of ourgrowers and their female family members or female OFL workers show, who sacrificed alternative sources of income and social value for the mangoes.

We can conclude that the ‘blasted landscapes’ of the collapsed project include sentiments of disappointment and shame among past and remaining mango farmers, dead labour (i.e. non-remunerated), lost or destroyed sources of alternative income for participating households (i.e. other food or cash crops) and strained social relations in affected communities. Our contribution reminds researchers not only to attend to the changing political technologies of agricultural commercialization in rural Africa, but also to recurrent occurrences of disarticulations between capital, farmers and the communities where farmers live. What local farmers need and get and what (foreign) investors want and get often diverges. This reiterates our call to scrutinize VCA particularly for the uneven distribution of risk and sacrifice, as well as the social and material debris that projects of commercialization may leave behind after capital has moved on.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this paper to Professor Kojo Sebastian Amanor (University of Ghana), whose grounded, critical and dedicated research in agrarian political economy has been a true inspiration. We also thank Dr Festus Boamah (University of Bayreuth) and Professor Tanu Biswas (University Stavanger) for helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. We also thank Julia Blauhut at Bayreuth University for the cartography. Lastly, we thank the guest editors of the themed issue and the anonymous reviewers for their guidance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Azindow Yakubu Iddrisu

Azindow Yakubu Iddrisu is a PhD candidate at the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana.

Stefan Ouma

Stefan Ouma is Professor of Economic Geography at the University of Bayreuth.

Joseph Awetori Yaro

Joseph Awetori Yaro is Professor of Geography at the University of Ghana.

Notes

1 Following the classic contribution of Watts (Citation1994, pp. 26–27), we define contract farming as institutionalized

relations between growers and private or state enterprises that substitute for open-market exchanges by linking nominally independent family farmers of widely variant assets with a central processing, export, or purchasing unit that regulates in advance prices, production practices, product quality, and credit.

2 The lack of engagement with failed investments and the ruins these leave behind can also be found in the literature on large-scale land acquisitions that have unfolded since the late 2000s (but see Li, Citation2015). However, while such investments certainly exhibit overlaps with value-chain agriculture, their drivers are more organically linked to the food and financial crises of 2007–2008 and the emergent push to ‘feed the world’ (Ouma, Citation2014) than to the more general interest in VCA that evolved from the early 2000s as part of the post-Washington Consensus (Gereffi, Citation2014). Thus, we date the dawn of value-chain agriculture earlier than McMichael (Citation2013), who coined the term and published his paper at the height of the global land rush controversy.

3 We acknowledge that the distinctions between contract farming and VCA today are blurry. We argue that contract-farming thinking has become so much engrained in VCA that one often cannot have the latter without the former. However, whereas earlier rounds of contract-farming promotion in Africa and beyond also tried to produce particular farming subjects, there were less concerned with microeconomic reengineering. This is a specific aspect of VAC, which has to be seen in light of the emerging post-Washington Consensus paradigm in which market interventions are given a firm place in development (Werner et al. Citation2014).

4 Outgrower schemes can take a variety of forms. The case we shall discuss in this paper is the ‘nucleus-estate model’ (Eaton & Shepherd, Citation2001, p. 50), in which a financing company ‘also owns and manages an estate plantation, which is usually close to the processing plant’ (Eaton & Shepherd, Citation2001, p. 50).

5 In this paper, we anonymize the case and stick to the names used in Ouma (Citation2015). This means that work cited in the reference list published by the other authors will contain an anonymized version of the company name accordingly. Names of other organizations named here have been altered, too, and are normally indicated by an asterisk*.

6 The British colonialists instituted a system of forced labour movements in Ghana that linked the north and the cocoa, mining and urban regions of the south. Purposeful uneven development created north-south migration flows that continue to asymmetrically link these different parts of Ghana today.

7 These celebratory accounts, however, usually glossed over the fact that women made up only 10% of the total outgrower force, and the majority of these fronted for male relatives with little control over the plantations.

8 That local or regional power brokers play a central role in the transfer of landed property from local communities to investors in Ghana has been document both for the colonial and early post-colonial period (Amanor, Citation1999) as well as more recent times (Boamah, Citation2014).

9 For a classic take on this problem, see Carney (Citation1988).

10 The authors withhold monetary figures here due to confidentiality reasons.

11 We here build on the notion of the real subsumption of nature (Boyd & Prudham, Citation2017).

12 Moringaceae, a widely used local tree.

References

- Addo, E., & Marshall, R. (2000). Ghana's non-traditional export sector: Expectations, achievements and policy issues. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 31(3), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(99)00049-4

- Akram-Lodhi, A. H., Dietz, K., Engels, B., & McKay, B. (2021). An introduction to the handbook of critical Agrarian studies. In A. Haroon Akram-Lodhi, K. Dietz, B. Engels, & B. M. McKay (Eds.), Handbook of critical agrarian studies, 1–7. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Amanor, K. S. (1999). Global restructuring and land rights in Ghana: Forest food chains, timber and rural livelihoods. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Amanor, K. S. (2010). Family values, land sales and agricultural commodification in southeastern Ghana. Africa, 80(1), 104–125. https://doi.org/10.3366/E0001972009001284

- Amanor, K. S. (2019). Global value chains and agribusiness in Africa: Upgrading or capturing smallholder production? Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, 8(12), 30–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277976019838144.

- Baglioni, E., & Gibbon, P. (2013). Land grabbing, large- and small-scale farming: What can evidence and policy from 20th century Africa contribute to the debate? Third World Quarterly, 34(9), 1558–1581. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.843838

- Bebbington, A. (2003). Global networks and local developments: Agendas for development geography. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 94(3), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00258

- Boamah, F. (2014). How and why chiefs formalise land use in recent times: The politics of land dispossession through biofuels investments in Ghana. Review of African Political Economy, 41(141), 406–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2014.901947

- Bolwig, S., Ponte, S., Du Toit, A., Riisgaard, L., & Halberg, N. (2010). Integrating poverty and environmental concerns into value-chain analysis: A conceptual framework. Development Policy Review, 28(2), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00480.x

- Boyd, W., & Prudham, S. (2017). On the themed collection, “The formal and real subsumption of nature”. Society & Natural Resources, 30(7), 877–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2017.1304600

- Brüntrup, M., Schwarz, F., Absmayr, T., Dylla, J., Eckhard, F., Remke, K., & Sternisko, K. (2018). Nucleus-outgrower schemes as an alternative to traditional smallholder agriculture in Tanzania – strengths, weaknesses and policy requirements. Food Security, 10(4), 807–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0797-0

- Burawoy, M. (1998). The extended case method. Sociological Theory, 16(1), 4–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00040

- Burawoy, M. (2003). Revisits: An outline of a theory of reflexive ethnography. American Sociological Review, 68(5), 645–679. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519757

- Carney, J. (1988). Struggles over crop rights and labour within contract farming households in a Gambian irrigated rice project. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 15(3), 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066158808438366

- Chalfin, B. (2004). Shea butter republic. State power, global markets, and the making of an indigenous commodity. Routledge.

- Coulson, A. (2015). Small-scale and large-scale agriculture: Tanzanian experiences. In M. Ståhl (Ed.), Looking back, looking ahead—land, agriculture and society in east Africa (pp. 44–73). Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Dolan, C. (2001). The ‘good wife': Struggles over resources in the Kenyan horticultural sector. Journal of Development Studies, 37(3), 39–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331321961

- Eaton, C., & Shepherd, A. W. (2001). Contract farming partnerships for growth. A guide. FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin, 145.

- Fraser, J., Fisher, E., & Arce, A. (2014). Reframing ‘crisis’ in fair trade coffee production: Trajectories of agrarian change in Nicaragua. Journal of Agrarian Change, 14(1), 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12014

- Gereffi, G. (2014). Global value chains in a post-Washington consensus world. Review of International Political Economy, 21(1), 9–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2012.756414

- Hagedorn, J. S., & Scott, K. M. (1981). The east African groundnut scheme: Lessons of a large-scale agricultural failure. African Economic History, 10, 81–115.

- Hall, R., Scoones, I., & Tsikata, D. (2017). Plantations, outgrowers and commercial farming in Africa. Agricultural commercialisation and implications for agrarian change. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(3), 515–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1263187

- Iddrisu, A. Y. (2012). An analysis of the impact of contract farming on land tenure systems. Unpublished Master thesis, University of Ghana [full title withheld to ensure anonymity of case study company].

- Kaarhus, R. (2018). Land, investments and public-private partnerships: What happened to the Beira agricultural growth corridor in Mozambique? The Journal of Modern African Studies, 56(1), 87–112. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X17000489

- Kimari, W., & Ernstson, H. (2020). Imperial remains and imperial invitations: Centering race within the contemporary large/ scale infrastructures of east Africa. Antipode, 52(3), 825–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12623

- Li, T. M. (2015). Transnational farmland investment: A risky business. Journal of Agrarian Change, 15(4), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12109

- McMichael, P. (2013). Value-chain agriculture and debt relations: Contradictory outcomes. Third World Quarterly, 34(4), 671–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.786290

- Murray, W. E., Chandler, T., & Overton, J. (2011). Global value chains and disappearing rural livelihoods: The degeneration of land reform in a Chilean village, 1995-2005. The Open Area Studies Journal, 4(1), 86–95. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874914301104010086

- Nabila, J. S. (1972). Depopulation in Northern Ghana- Migration of the Frafra people. Interdisciplinary approaches to population studies. West African conference on population studies, University of Ghana, Population Studies, No. 4.

- Niebuhr, D. (2016). Making global value chains: Geographies of market-oriented development in Ghana and Peru. Springer Gabler.

- Oliveira, G. d. L. T., McKay, B. M., & Liu, J. (2020). Beyond land grabs: New insights on land struggles and global agrarian change. Globalizations, 18(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1843842.

- Ouma, S. (2014). Situating global finance in the land rush debate: A critical review. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 57, 162–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.09.006

- Ouma, S. (2015). Assembling export markets. The making and unmaking of global food connections in West Africa. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Pérez Niño, H. (2016). Class dynamics in contract farming: The case of tobacco production in Mozambique. Third World Quarterly, 37(10), 1787–1808. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1180956

- Phelps, N. A., Atienza, M., & Arias, M. (2018). An invitation to the dark side of economic geography. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(1), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17739007

- Plange, N.-K. (1979). Opportunity costs and labour migration: A misinterpretation of proletarianisation in northern Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 17(4), 655–676. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00007497

- Ponte, S., & Brockington, D. (2020). From pyramid to pointed egg? A 20-year perspective on poverty, prosperity, and rural transformation in Tanzania. African Affairs, 119(475), 203–223. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adaa002

- Poulton, C. (2017). What is agricultural commercialization, why is it important and how do we measure it? APRA Working Paper 6, Future Agricultures Consortium. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/13560

- Salverda, T. (2021). Multiscalar moral economy. Global agribusiness, rural Zambian residents, and the distributed crowd. Focaal, 2021(89), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.3167/fcl.2020.033101

- Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1), 171–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820503

- Scott, C. (1998). Seeing like a state. How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press.

- Singh, S. (2002). Contracting out solutions: Political economy of contract farming in the Indian Punjab. World Development, 30(9), 1621–1638. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00059-1

- Singh, S. (2003). Contract Farming in India: Impacts on Women and Child Workers. IIED:Gatekeeper Series No.111. https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/9281IIED.pdf

- Songsore, J., & Denkabe, A. (1995). Challenging rural poverty in northern Ghana: The case of the upper-west region. University of Trondheim.

- Stoler, A. (2008). Imperial debris: Reflections on ruins and ruination. Cultural Anthropology, 23(2), 191–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2008.00007.x

- Tsikata, D., & Yaro, J. A. (2014). When a good business model is not enough: Land transactions and gendered livelihood prospects in rural Ghana. Feminist Economics, 20(1), 202–226. http://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.866261

- Tsing, A. L. (2008). Contingent commodities: Mobilizing labor in and beyond southeast Asian forests. In J. Nevins & N. L. Peluso (Eds.), Taking Southeast Asia to market: Commodities, nature, and people in the neoliberal Age (pp. 27–42). Cornell University Press.

- Tsing, A. L. (2012). Empire's salvage heart: Why diversity matters in the global political economy. Focaal, 2012(64), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.3167/fcl.2012.640104

- Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

- Vira, B., & James, A. (2011). Researching hybrid ‘economic'/'development’ geographies in practice: Methodological reflections from a collaborative project on India's new service economy. Progress in Human Geography, 35(5), 627–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510394012

- Watts, M. (1994). Life under contract: Farming, Agrarian restructuring, and flexible accumulation. In P. D. Little & M. Watts (Eds.), Living under contract (pp. 21–77). University of Wisconsin Press.

- Werner, M. (2019). Geographies of production I. Progress in Human Geography, 43(5), 948–958. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518760095

- Werner, M., Bair, J., & Fernández, V. R. (2014). Linking up to development? Global value chains and the making of a post-Washington consensus. Development and Change, 45(6), 1219–1247. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12132

- Whitfield, L. (2017). New paths to Capitalist Agricultural Production in Africa: Experiences of.

- Yaro, J. A., & Tsikata, D. (2013). Savannah fires and local resistance to transnational land deals: the case of organic mango farming in Dipale, northern Ghana. African Geographical Review, 32(1), 72–87. http://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2012.759013