ABSTRACT

This article analyzes the impacts of resource extraction on indigenous communities focusing on the case studies of two indigenous minorities in Russia: Veps in Karelia and Soiots in Buriatia. Veps and Soiots have a history of engagement with resource extraction, which goes back to the eighteenth century and continues till the present time. By focusing on two models of human – landscape relations and industrial development in indigenous territories, the article discusses the perceptions of decorative stones among Veps and Soiot households. It specifically focuses on parallels between mining and other forms of economic activities such as hunting, fishing, or tourism development. The article demonstrates that different forms of resource extractions are closely connected in Veps and Soiot villages, forming a common resourcescape. Both mining and other forms of extracting natural resources contribute to local visions of sustainability, which unite various forms of engagement with nature.

Introduction

As indigenous cooperation in the North is under threat as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (Larsen, Citation2022), the analysis of indigenous peoples’ position and their relations with the state in Russia becomes especially important. In the spring of 2022, several Russian indigenous organizations supported the actions of the Russian government. At the same time, independent indigenous groups and activists are repeatedly making statements condemning the war.Footnote1 Indigenous minorities are also among the groups hit hardest by the mobilization announced in Russia in September 2022 (Bessonov, Citation2022). This situation illustrates the divisions inside Russian indigenous groups, as well as their limited opportunities for political expression within the state borders. While the period of the 1990s and early 2000s was marked by intensive revitalization movements and focused on indigenous political participation, contemporary policies of the Russian state primarily target cultural aspects of indigeneity placing indigenous residents into a marginalized position (Nikolaeva, Citation2017). As a result, Russian indigenous politics is characterized by power imbalances and a lack of indigenous peoples’ inclusion in decision-making processes (Sulyandziga & Sulyandziga, Citation2020). These challenges are manifested in the realm of resource extraction, where it is often extremely difficult for indigenous communities to receive compensation for environmental damage or take part in decision-making (Tysiachniouk et al., Citation2018).

This article focuses on indigenous and local relations with natural resources in the setting of uneven power distribution in Russia. It focuses on two indigenous communities residing in different parts of the country: Veps in Karelia (Northwestern Russia) and Soiots in Buriatia (South-Central Siberia). Both Veps and Soiots received indigenous status relatively late, in the year 2000, as a result of revitalization campaigns initiated by local activists in the 1990s (Donahoe, Citation2011; Puura & Tánczos, Citation2016). Both communities reside close to mining sites and participate in resource extraction, although in different forms. The article demonstrates how indigenous narratives on resource extraction are shaped by state policies, but simultaneously constructed through daily interaction with landscape and industry. Mining narratives, therefore, become embedded in local identity articulations and human-landscape connections. The article discusses how stone mining becomes a part of local bonds with the landscape in Karelia and Buriatia.

To address this question, in this article I bring forward the notion of resourcescape that encompasses the interactions between different types of resource extraction in the shared more-than-human landscape. I draw on the concept of ‘-scape’ suggested by Arjun Appadurai in his study on global cultural flows for the concepts like ethnoscapes, mediascapes, or technoscapes ‘to point to the fluid, irregular shapes of these landscapes’ (Appadurai, Citation1996, p. 33). Natural resource extraction is often perceived as the activity opposing other forms of interaction with the landscape such as ecotourism (Büscher & Davidov, Citation2013), hunting, or fishing. In this article, I argue that the extraction of stone may become deeply embedded in the established forms of human – landscape interactions, and the relations between different forms of resource extraction are fluid and unsettled.

The article focuses on two case studies of human-resource entanglement in Prionezhskii district of Karelia (Prionezhie) and Okinskii district of Buriatia (Oka). These areas have traditionally been inhabited by Indigenous communities: northern Veps in Karelia and Oka Soiots in Buriatia. Due to the migratory processes of the 18th – 20th centuries, the communities of Prionezhie and Oka are currently more diverse. Because of this diversity, the notions of indigeneity are in constant flux in both regions. In Oka, the notion of ‘Okans’ is frequently used to unite Soiots and Oka Buriats as long-term inhabitants of the territory. In Prionezhie, many residents of Veps villages come from mixed ethnic backgrounds, as many mining workers moved to the villages in the Soviet years from various parts of the country. In such situations, it often becomes difficult to divide the community into clear and distinct categories such as ‘local’ versus ‘incomer’, as many community members would fall in between these categories (Liarskaya, Citation2017). Therefore, indigeneity could be viewed as a relative category or a continuum: the fact that a certain group exercises its indigenous claims in one context does not mean that this identity remains unchanged in other contexts (Hicks, Citation2011, p. 229). In this article, I view Veps and Soiot indigeneity as such a continuum potentially including those who are not indigenous by origin but who feel strongly connected to the region.Footnote2

The types of stone extraction in Prionezhie and Oka are different, and the level of local participation in mining also varies. Prionezhie Veps have engaged in the mining of two rare decorative stones, gabbro-diabase and raspberry quartzite,Footnote3 since the 18th – 19th centuries. Both stones were used for the construction and ornamentation of well-known buildings and monuments, including the Red Square ensemble in Moscow and Napoleon’s sarcophagus in Les Invalides in Paris. Veps experienced the shift from small-scale artisanal mining to rapid Soviet-era industrialization and the closure or privatization of state enterprises in the post-Soviet period. In Oka, graphite extraction was developing for brief periods in the 19th and 20th centuries. In the Soviet period, Oka became a place of active geological explorations. However, gold and nephrite (jade) mining started there in the 1990s, soon after the automobile road to Oka was constructed (Varfolomeeva, Citation2020). Starting from the early 2000s, many Okans have been engaged in the informal search for pieces of jade. At times, this involves extracting or collecting stones from the mining sites, but there have also been cases of jade stealing from private companies’ warehouses.

The article is based on participant observation and semi-structured biographical interviews conducted during several research visits in Prionezhie and Petrozavodsk in Karelia (2015–2018 and 2021) and Oka and Ulan-UdeFootnote4 in Buriatia (2016, 2017, and 2021).Footnote5 In Prionezhie, I conducted 87 interviews with current and former mining workers, residents not involved in mining, administration representatives, as well as Veps scholars, teachers, and members of the Veps speaking club Paginklub. In Oka, I conducted 56 interviews in total with residents, administration representatives, Buddhist lamas, teachers, and activists. All research participants have been fully informed about the contents and purpose of the study and have provided their consent to be interviewed and recorded. To protect the interviewees’ anonymity, pseudonyms have been used for all interviewees cited in the article. When citing the interviews, I use the code ‘K’ for Karelia and ‘B’ for Buriatia as well as the sequential number of the interview.

Resource extraction as a part of resourcescape

Natural resource extraction entails the boundary-making process between humans and objects, or ultimately between nature and culture, and thus is closely linked to the perceptions of modernity (Richardson & Weszkalnys, Citation2014). An unknown and unnamed substance becomes a resource only with the human act of appropriation, which constitutes its symbolic ‘birth’ (Ferry & Limbert, Citation2008). In the concept of resource social and material correlate, as it is at the same time a physical entity and an object characterized by certain meanings and values. At the same time, natural resources produce new social configurations (Gilberthorpe, Citation2007; Richardson & Weszkalnys, Citation2014). As Andy Bruno (Citation2018, p. 147) points out, ‘a rock can excite and destroy, facilitate and undermine, or create value and costs’.

This article focuses on decorative stones, including diabase, quartzite, and jade, as a part of a dynamic landscape viewed as the ongoing ‘cultural process’ (Hirsch, Citation1995, p. 5) of locating an individual or a community in the world. The suffix ‘-scape’ addresses fluidity, irregularity, and constant change (Appadurai, Citation1996, p. 33). As Edward Soja (Citation2006, p. xv) notes, the adaptability and versatility of the suffix – scape is limitless, and it can be easily transformed into ‘escape’, ‘shape’, ‘scope’, and receive additional layers of meanings with each transformation. By connecting such concepts, as ethnoscapes, mediascapes, technoscapes, financescapes, and ideoscapes through their shared suffix, Arjun Appadurai (Citation1996, p. 33) discusses them as ‘deeply perspectival constructs, inflected by the historical, linguistic, and political situatedness of different sorts of actors’.

The – scape suffix has been employed to create concepts like ‘borderscape’ – an understanding of borders as mobile spaces extending beyond the border itself (Schimanski, Citation2015; Wagner Tsoni, Citation2019) – and ‘lawscape’, seen as an interplay between law and space (Graham, Citation2010; Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, Citation2014). Melina Ey and Meg Sherval use the concept of ‘minescape’ that characterizes extraction sites as more than economic areas and views them as ‘complex socio-cultural terrains’ (Ey & Sherval, Citation2016, p. 178). By using the notion of ‘resourcescape’ rather than ‘minescape’ in this article, I build on the understanding of extraction sites as being embedded in socio-cultural landscapes. At the same time, I focus on the interconnectedness between mining and other forms of resource extraction such as hunting, fishing, or tourism development. The concept of resourcescape stresses that the entanglements of mining and landscape are not happening in isolation, but they are a part of the larger notion of human – resource relations. The embeddedness of mining in the landscape may take different forms. As the case study discussed in this article demonstrates, stone mining may become a connecting point between new residents and unfamiliar landscape; it may change the landscape significantly, but at the same time human – landscape ties influence local attitudes towards extraction.

Resource-making is a process that rarely follows a simple linear trajectory (D’Angelo & Pijpers, Citation2018). The production of the resource subsequently produces multiple temporalities which are often intertwined. At the same time, resource production is integrated into the landscape and connected to its past and future as mining and other forms of extraction modify the surroundings. The usage of the concept could potentially emphasize the interdependence of different forms of resource extraction in local and indigenous households. By focusing on mining as a part of resourcescape, it is possible to step beyond its destructive potential and analyze how resource extraction simultaneously creates new connections and social configurations, modifying the community’s relations with the landscape as well as citizen – state communication. The history of resource extraction in the Russian North and Siberia has been inherent to irreversible transformations of indigenous lifestyles (Funk, Citation2018). As Veps have been situated much closer to the federal centres than Soiots, the influence of state policies on their livelihoods and their links with industrial resources is more articulated. While the Veps resourcescape has largely been governed by state-organized industries, the Soiot resourcescape formed through intimate multispecies communication in a harsh climate.

Through the analysis of Veps and Soiot resourcescapes, this article stresses that the notions of sustainability are place-specific (Sörlin, Citation2020). Today, the concept of sustainability is heavily debated and used so commonly that, as critics argue, it bears a risk of turning into ‘sustainababble’, a buzzword devoid of meaning (Engelman, Citation2013). Generalized notions of sustainability bear the risk of overshadowing and suppressing those whose perspectives differ from mainstream discourses, (Virtanen et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it is important to pay attention to whose practices get ignored and overlooked in sustainability discourse, including Indigenous communities who are often conceptualized through the lens of ‘ecological nobility’ and expected to live up to unreachable standards imposed on them (Nadasdy, Citation2005, p. 293). Failure to maintain these standards leads to creating new labels of ‘non-authentic’, ‘ignoble’ or ‘anti-environmentalists’. The reinforced dichotomy between ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ leads to disregarding the possibility ‘that aboriginal people may possess distinct cultural perspectives on modern industrial activities such as logging or mining’ (Nadasdy, Citation1999, p. 4). However, the relations between extractive industries and traditional subsistence activities of Indigenous communities are complex, and there are cases when industrial development supports traditional subsistence (Southcott & Natcher, Citation2018). The cases of Veps and Soiots demonstrate that in indigenous and local epistemologies mining is not necessarily alien to other forms of resource extraction such as hunting, fishing, or tourism. The perceptions of mining as sustainable or unsustainable are closely linked to the problems of symbolic ownership and responsibility in human – landscape relations.

Human-industry ties in Veps villages

Veps are a Finno-Ugric ethnic minority primarily residing in three regions of Russia: Karelia, Leningrad region, and Vologda region. This article centres on Veps in Prionezhie in Karelia, as this group is characterized by their long-term involvement in the stone mining industry. In Karelia, Veps reside in several villages and settlements on the shore of Lake Onega. I primarily worked in Shoksha, Sheltozero, and Rybreka villages and Kvartsitnyi mining settlement (see ).

In the 18th – 19th centuries, Veps were well-known in Karelia and its neighbouring regions as skilled stoneworkers. Stone extraction was an important source of subsistence in Prionezhie Veps villages in addition to agriculture and commercial fishing (Davidov, Citation2017). It was carried out by working brigades who often travelled with diabase and quartzite to St. Petersburg, Kronstadt, and many other cities for construction work. At the end of the nineteenth century, more than half of the male population in Veps villages was involved in seasonal stoneworking labour in different parts of the country (Korablyov, Citation1999). Because of their engagement in stone extraction and trade, Prionezhie Veps were viewed by nineteenth-century researchers as more prosperous compared to other groups of Veps in the neighbouring regions; their level of literacy was also higher (Strogalschikova, Citation2014). Fast mining development in Prionezhie Veps villages started in the early Soviet period when large state-owned quarries producing diabase and quartzite opened in the 1920s. Both stones were used for decorative and industrial purposes (such as enamel production). After the fall of the Soviet Union, due to financial difficulties of the 1990s, state mining enterprises gradually went bankrupt and were closed or sold to private owners. Currently, the extraction of raspberry quartzite near the Shoksha village almost ceased; there is one private company working there, and it employs around twenty people. The quartzitic sandstone quarry near the Kvartsitnyi settlement has closed. In Rybreka, diabase mining is being continued by several private companies of different sizes. These changes in the stone industry influence the perceptions of the local resourcescape in Veps villages.

Formed and disrupted ties with stone

In Veps folklore, various landscape features such as forests, lakes, and rivers, were believed to have their ‘masters’ (in Vepsian, ižand) (Vinokurova, Citation1994). Stones also had sacred meanings in Veps culture and were a part of various rituals partly because of their physical characteristics such as weight, coldness, or immobility (Vinokurova, Citation2015). Stones often served as a connecting point between a person and the master of the forest, as they were used for leaving sacrifices. Another example of stones’ role as a link between humans and spirits is their usage in the past as a part of fortunetelling rituals (Vinokurova, Citation2015). However, in the interviews I conducted with the residents of Veps villages in Karelia in 2015–2018, it was almost impossible to find traces of the traditional beliefs described by the ethnographers working with Veps in the late 1980s. ‘Our parents did not teach us about that’, – an older informant from Rybreka told me with an apologetic expression when I asked her about the forest master (Interview K56). Another informant, a middle-aged man also residing in Rybreka, when asked the same question, briskly replied, ‘I don't believe in such things! Oh wait, there is a forest master – the bear! And you know, I would not want to meet him for sure’ (Interview K54). This discontinuity in human – landscape relations could partly be explained by the closeness of Veps villages to Petrozavodsk, the capital of Karelia, and their susceptibility to state influence resulting from this closeness.

The connections between Veps residing in different regions were weakened during the Soviet period due to administrative divisions. In 1924, Veps villages on the coast of Lake Onega were divided between Karelia (in that period Karelian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic) and the Leningrad region (Kurs, Citation2001). Due to these changes, as well as limited transportation opportunities, the communication between the villages belonging to different administrative units was largely disrupted. In the mid-twentieth century, many Karelian Veps migrated to Petrozavodsk due to the state policy of ‘Liquidation of Villages without Prospects’, which was carried out by the Soviet state in the 1960s–1970s.Footnote6 At the same time, many young professionals from other regions of the Soviet Union moved to Prionezhie to work in the mining industry. This wave of migration became especially noticeable in the 1970s–1980s, as the newly built quartzitic sandstone quarry in Kvartsitnyi was recruiting workers from different parts of the country. Between the end of World War II and the end of the 1980s, the ethnic composition of the area changed rapidly. The existing local beliefs deeply rooted in landscape features were not immediately shared with newcomers.

Initially, many of the young professionals coming to Karelia to work in the mining quarries did not plan to stay there for long. As fresh graduates of geological departments, they treated Karelia as a temporary workplace, though later, as they started families, a number of them stayed in Prionezhie. Therefore, the district was seen as a ‘transit point’, but it was not filled with deeper meanings yet. Stone quarries served as unifying elements bringing people together from different parts of the country. As a result, rapid mining development and changing ethnic composition of Veps villages and Prionezhie resulted in the rupture in formerly existing human-landscape relations, reinstating the stone industry as the new animated and sacred entity in the Veps community.

As diabase and quartzite have been used for well-known buildings and monuments, the stoneworkers’ labour serves as a symbolic connection to the state. Sergei, a former mining worker, recalled how during his studies in Moscow, he proudly told other students at Red Square, ‘This is our stone!’ (Interview K21). When among fellow students from other regions of the Soviet Union, Sergei shared his knowledge of diabase and quartzite as a part of Red Square's ensemble as an indicator of his belonging to one of the focal points of the Moscow landscape. By claiming Red Square's stone as ‘our stone’, Sergei reinforced the connection between Veps villages in Karelia and well-known places in the country. Diabase and quartzite thus serve as a source of patriotic feelings towards Karelia: the stones’ fame is simultaneously the fame of their producers and their home region.

Both diabase and quartzite have a dual status: on the one hand, they were commonly used in the Soviet period for industrial needs or building pavements, and were therefore valued for their firmness and durability. On the other hand, they are also used in decorations and are thus seen as precious stones. This duality is reflected in the interviews with locals who often mention the value of stones as a material resource: ‘Our diabase is the hardest stone; it is even sent to nuclear power plants, that's how hard it is’ (Interview K29). The informants also perceive the value of stones as beautiful objects, especially in the case of quartzite due to its unusual colour and glorious history: ‘It is amazing, what a color it is. The color of ripe raspberry, over ripe berries … It is such a beautiful color’. (Interview K24). Other interviewees emphasized the creative aspect of working with stone: ‘This is hard labor, but one feels like an artist when doing it’ (Interview K13).

In Soviet-era enterprises, pride in diabase and quartzite was cultivated by quarry managers and local administrations. In the office of Onezhskoe rudoupravlenie, the main mining enterprise of Prionezhie, there was a map showing all the destinations where the local stone was going (Kostin, Citation1977). The newspapers of Prionezhie published articles devoted to all noticeable destinations of diabase and quartzite, as well as interviews with prominent stoneworkers. In such an interview, the stoneworker Aleksandr Ryboretskii mentioned, ‘When we are in Moscow, Leningrad, Petrozavodsk or other cities, we do not part with our Rybreka. We are proud that monument details in those cities have been made with our hands’. (Kommunist Prionezhia, November 4, 1967). However, as mining enterprises were privatized, the links between the workers and the resources they have been engaged with have weakened. Many informants feel that private mining companies ‘waste the stone’ by selling it for private graveyard monument construction. In the interviews, the decline of the mining industry is often connected with the overall state of rupture the Veps villages have experienced in the post-Soviet period. The common complaint expressed in the interviews is that unknown quarry directors, most of them not from Karelia, do not demonstrate care for local needs and interests. The residents are also worried that the stone is carried away from the region to unknown places. Simultaneously, they complain about the noise and dust from the stone extraction, or about road damages resulting from frequent trucks carrying stone blocks.

The situation I observed during my fieldwork offers a radical contrast to the Soviet-era promotion of diabase and quartzite's well-known destinations expressed in the interviews. Veps miners’ role in producing rare and unique materials needed in different places of the country is also questioned in the post-Soviet period. A local whom I met in Rybreka village noted, ‘they [private companies] just take the stone from us, and we are not needed anymore’. Another interviewee noted that the current owners of the quarries do not know the community:

The owner of Interkamen’ [one of the mining companies in Rybreka] – people say he has a helicopter field next to his house here. He just gets in the helicopter, flies to Moscow, then back … He does not know the village. (Interview K51)Footnote7

Nina, an elderly resident of Rybreka, said to me bitterly,

… Rudoupravlenie [The name of the Soviet-time mining enterprise] does not exist anymore … Now it’s not our people here, the owners [of the quarries] are all from Moscow and Petersburg, and we are … I do not know who we are anymore. They do not do anything for the village … They do not do anything, nothing is being built and there is no help. (Interview K29)

In several quotes, there is an overall sense of loss or obscurity: ‘we are not needed anymore’ or ‘I do not know who we are anymore’. However, even when private companies are accused of mismanagement, the importance of mining itself is not doubted. ‘Our village would not exist without mining’, – a resident of Rybreka stated plainly in an informal conversation.

The changes in Veps resourcescape reflect the shifting relations between the villages’ community and the state. During the Soviet period of the quarries’ history, Veps relations with the sacred landscape were largely replaced with new ties formed with the diabase and quartzite industry. As mining quarries were privatized in the 1990s, however, the links established with industry got disrupted as well. Many residents of Veps villages feel that they lose perceived control over local stone extraction as unknown private owners are managing the local resources and not investing in development of the area. Whereas, as the following section will demonstrate, residents of Veps villages do not draw strict borders between mining and other forms of extraction, they differentiate between beneficial and ‘wasteful’ management of local resources.

Mining and nature interrelated

The rapid development of the mining industry in Karelia in the Soviet period resulted in significant landscape changes. The miner’s settlement of Kvartsitnyi (deriving its name from raspberry quartzite) was built in the 1970s next to the centuries-old Veps village Shoksha. The panorama of Rybreka village is now defined by the long rocky mountain where diabase is extracted. Most of the villagers combined work in the quarry and close contact with nature in their surroundings. Svetlana, a resident of Shoksha village, remembered how she and her husband went fishing or berry-picking after a work shift or on a day off:

We also had time to pick blueberries, two buckets of blueberries over a weekend; then we would go to the city to sell them. And then he [the informant's husband] would return home at 2 am with a bag of perch. And imagine, I need to wake up at five in the morning to go to work, but at two, I am still standing and scaling the perch! (Interview K13)

In the interviews, many informants mentioned the beautiful nature of Karelia as one of the reasons for staying in the village even if work prospects were not good. The radical changes of nature were often perceived as something negative. The attitudes towards the possible negative impact of mining on nature are, nevertheless, complex. While many interviewees mentioned the negative impacts of mining (such as the dust in the air or the water pollution), they still acknowledged it as an important industry for development of the villages. A former worker of the boiler house who moved to Karelia in 1971 stated when describing her life in the settlement, ‘There were explosions almost every day in the quarry, but they were not bothering me. This was their work, you know’ (Interview K37). Even though the boiler-house worker mentioned the negative impacts of the mining industry (such as the noise from the explosions), she simultaneously noted that this noise was a necessary part of the work which could not be avoided.

Even in situations when possible environmental harm (for example, fewer berries in the forest or fewer fish in the lake) was acknowledged, mining companies were not necessarily the ones to blame. In the neighbouring settlements of Shoksha and Kvartsitnyi, the residents’ anger is rather aimed at the private tourist companies situated in Kvartsitnyi, at the shore of Lake Onega. The services such companies provide mostly target wealthy tourists from Moscow or St. Petersburg who are willing to experience the countryside life in Karelia with fishing, swimming, boat trips, and excursions to the raspberry quartzite extraction site as a bonus. Svetlana from Shoksha, after recalling how her husband returned home with a catch of perch, added angrily:

There were tons of fish! Tons! But no, today there are no fish in the lake, especially salmon or trout. We had it before … But now these [tourist] bases fished it out. (Interview K13)

Tourist companies are perceived negatively as outsiders: they, as the locals claim, mostly have Moscow owners. As a result, the interviewees feel that the tourist companies have taken possession of the resources meant first and foremost for locals. ‘Are you from Petrozavodsk? – a resident of Shoksha asked me, and quickly added: – That's good, I thought it was somebody from Moscow!’ (Interview K28). He later explained that the tourists from Moscow are appropriating the land near the villages, including the shore of Lake Onega. Similarly, the seller in a local shop in Kvartsitnyi told me, ‘Our entire coast has been bought, and we are just cobblers without shoes: we see no fish these days’.

The resourcescape of Veps villages has been largely formed by state-managed Soviet stone quarries that promoted diabase and quartzite extraction as a vital industry serving the state. The perceptions of stone as a resource of high importance are still common among Veps villages’ residents, and stone extraction largely governs other forms of interacting with the landscape. As a result, Veps resourcescape is arranged as a division of different forms of resource extraction into positive – when it serves the community, and negative – when the locals feel that they are deprived of their resources without any profit in return. Thus, in many cases, Soviet-era quarries were perceived positively, as they provided services, accommodation, support for kindergartens and schools, or other daily assistance. In contrast, tourist companies and private mining enterprises may be commonly blamed for appropriating local resources and not supporting the residents who are engaged in extraction. Mining and nature are presented in the interview narratives as being not in opposition but in interdependence. Their transformations are mutually related: stone extraction is seen as the outcome of the natural richness of Prionezhie, and the development or decline of mining defines the future of the villages.

Graphite legends and jade hunting in Oka

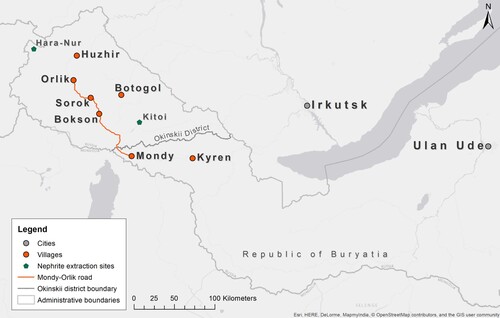

Oka is a remote part of Buriatia and a sparcely populated region with 5,400 people in its territory of twenty-six thousand square kilometers (See ). The majority of its population consists of Oka Buriats and Soiots, whose cultures in the 19th-twentieth century were developing in mutual influence (Pavlinskaya, Citation1999). The ancestors of Soiots, the Samoyedic people of the Saian Mountains, moved to the territory of contemporary Oka in the late Neolithic period (Pavlinskaya, Citation1999). The influx of Buriats in the region started after the border between Russia and China was established in 1727 and Buriat families migrated to Oka from Mongolia (Zhukovskaya, Citation2005). By the nineteenth century, the number of Buriats in Okinskii district was more than two times higher than the number of Soiots. Due to intermarriages, the cultures of Buriats and Soiots largely merged (Pavlinskaya, Citation1999).

The climate of Oka is relatively harsh. In winter time, the temperature may go below – 40, and the snow may stay from November till May. The warm summer period is rarely longer than forty days, and even during this time, night frosts may occur (Pavlinskaya, Citation2002). The harsh climate of Oka, which did not allow opportunities for agriculture, resulted in the preservation of the traditional ways of subsistence, such as nomadic pastoralismFootnote8 and hunting (Pavlinskaya, Citation2002). The shared Soiot and Buriat identity of ‘Okans’ is reinforced by the remote location of the region and the strong connections of residents with the Oka landscape.

The invisible presence of graphite, gold, and jade

Oka has a rich history of resource extraction. In the mid-nineteenth century, Soiot and Buriat hunters discovered graphite of high quality near Mount Botogol in Oka (Dorzhieva, Citation2014). Following this, Jean-Pierre Alibert, an entrepreneur of French origin living in Russia, initiated graphite extraction on Mount Botogol (Gishardaz & Chernykh, Citation2017). Alibert’s mine employed local Soiots and Buriats in graphite extraction. The extracted graphite was transferred to Germany, to the Faber Company in Nuremberg. In 1857, the extraction of graphite in Botogol stopped as the new technology of making pencil leads out of lower-quality graphite was discovered in France. Soon after that, Alibert left the region, and the graphite pit was slowly abandoned, despite Soviet-era attempts to revive the extraction in 1931–1932 (Gishardaz & Chernykh, Citation2017). In the Soviet period, geological brigades were searching for gold, jade, wolframite, molybdenum, and other natural resources in Oka. The construction of the gravel road to Orlik, the central settlement of Oka, began in 1985–1986, and approximately at the same time, the fast development of gold extraction was begun. At the time of my field research, the leading company extracting gold in Oka was Buriatzoloto operating in Samarta, the settlement situated approximately 100 km from Sorok, the settlement traditionally inhabited by Soiots.

Geological institutes began probing for jade in Oka in the 1970s, but extraction only started in the 1990s. Nevertheless, as the representative of Orlik’s administration explained to me, as the companies owning licences to extract jade had administrative and financial problems, the extraction was carried out on small-scale or, at times, it would stop completely (Interview B9). Since early 2000, when the demand for jade increased in China, informal extraction of the stone began in Oka (Interview B10). Nowadays, China is the main market for Buriat jade, as it is considered a sacred stone there and in certain historical periods was valued higher than gold or silver. Informal jade extraction is a widespread occupation in Oka among young and middle-aged men (Interview B4), as otherwise, job opportunities in this sparcely populated region are limited. In most cases, they travel to Kitoi or Hara-Nur, two main jade deposits. The extracted jade is then brought to Irkutsk or Ulan-Ude and sold to informal Chinese buyers. The contacts of these buyers are shared by word of mouth (Interview B8). The residents of other neighbouring regions (for example, Tunka district) also often travel to Oka to extract jade (Interview B5).

The mineral richness of Oka is often used as a marker of its value as a land. The locals often say that they have ‘all Periodic table under their feet’ (Interview B15, B17) referring to the richness of natural resources in Oka. The claims about the district’s mineral richness are often followed by the interviewees’ regrets that these resources are not used ‘in the right way’. One of the informants stated, ‘Everybody here [in Oka] is surprised, we live in such a rich area but we do not know how to manage these riches’ (Interview B17). ‘The right way’ of managing the resources, as the interviewees see it, would be to leave more control on gold and graphite mines for the local administration and to involve the local population in resource extraction (currently, it is managed by fly-in-fly-out workers) (Interview B5).

The story of French entrepreneur Jean-Pierre Alibert and his nineteenth-century graphite mine is also often mentioned in the interviews; residents refer to it as one of the proofs of the uniqueness of their region and its resources (Interview B5, B15). There are even legends that some residents of the district descend from French entrepreneurs who were working with Alibert: one of my interviewees told me that her relative did not look Buriat or Soiot at all having fair hair and blue eyes, and that was a sign that he was the descendant of a French entrepreneur who worked for Alibert (Interview B16). Alibert’s mine is often mentioned as proof of their region’s uniqueness, but the extraction also made Oka even more special by popularizing the Siberian graphite and leaving French descendants.

In contemporary Oka, locals know little about the gold extraction which is going on in the region, as most of them are not involved in gold mining and the extraction is separated from the villages they reside in. During my fieldwork, when I asked about gold mining, in most cases the respondents would reply that they did not know much as the gold mines were situated far away. Unlike in Prionezhie, where the quarries are located next to the Veps villages, the gold mining in Oka is not visible or audible, but at the same time it is indirectly present. As an example, the main company Buriatzoloto supports local youth initiatives financially (Interview B6) and sometimes sponsors local schools. Therefore, gold mining becomes present and absent at the same time.

Jade mining in Oka has a similar position of simultaneous presence and absence, as locals rarely speak about it openly, and the trips are also often kept secret even from relatives. As my interviewee Andrei explained, ‘I did not tell anyone at home that I went for jade. I said that we just went to the forest to fell timber. So that my mum and dad would not worry’ (Interview B8). Even if jade is not present in the villages of Oka as obviously as diabase and quartzite in Karelia, it is still there – though indirectly. ‘Look at the number of expensive cars there [in Oka], – an interviewee in Ulan-Ude who formerly worked in Oka told me. – Where do you think they all come from?’ (Interview B25). He was certain that the expensive cars were most probably related to illegal jade extraction. Although the extraction is kept secret, many locals do not perceive it as theft. Through informal extraction, they realize their symbolic ownership over local resources. As many Okans state, they may not comply with official legal norms of resource extraction, but they have the moral right to the local jade as a part of their land. As one of the interviewees framed it, ‘Why not take something that belongs to you anyway’ (Interview B5).

Therefore, the presence of mining in Oka is much more subtle when compared to Veps villages in Karelia. The opportunities to be formally engaged in mining are limited in Oka, and therefore the connections formed between humans and natural resources are very different here in comparison to Veps villages. Both in Prionezhie and Oka, natural resource extraction is closely connected with the locals’ attitudes towards their territory. In contrast, mining in Prionezhie has largely modified human – landscape connections and is currently dominating the local resourcescape. In Oka, mining becomes embedded in strong human – landscape relations as a part of them, but not as a dominating entity. Graphite extraction legends serve as a symbol of the region’s natural wonders and glorious history. Gold extraction generates worries as it is managed by outside investors and the locals do not have much knowledge about its state and prospects. Finally, informal jade mining reinforces Okans’ connections with the region as a source of unofficial employment allowing young men to stay in their home villages. Through informal extraction, the residents of Oka assert their symbolic ownership over the resource as a part of the region’s natural richness.

Jade as a subsistence resource

The high dependence on nature in Oka created a special connection of residents with the land which merges Buddhism and shamanism. Buriat and Soiot shamanist beliefs view the landscape as a sacred entity various parts of which – including subsurface resources – are animated and governed by spirit masters. These beliefs focus on a pantheon of celestial beings (tengri) where each god or spirit is associated with a specific natural force or a part of a landscape (such as a river or a mountain). Natural resources are an integral part of this spiritual ensemble. Therefore, when extracting resources from the earth, one is at the same time negotiating with the spiritual masters who may allow or prohibit the extraction. The sacred views on stones are represented in the cult of oboo – human-made stone pyramids that are used for leaving sacrifices for spirit masters governing a particular territory.

The characteristics of the Oka mountainous landscape influenced the patterns of local multispecies communication. As it is not possible to predict the changes in nature, it is important to remain flexible when dwelling in the Oka landscape. Locals change their routes or plans rather easily following the changes in nature. I saw an example of such flexibility during the drive from Orlik to Huzhir, a small settlement in the northern part of the district. On the way, our car needed to pass a narrow road next to the mountain. Our guide Aleksandr announced cheerfully, ‘This is quite a dangerous part; the stones may fall down on the road at any moment’. The car stopped, and Aleksandr asked us to join the ritual of treating the masters of the territory with rice and drops of vodka. As this was the only road connecting Huzhir with other settlements in Oka, I asked Aleksandr how the locals manage to pass here every day without being afraid of possible rock falls. ‘Well, you just need to be prepared to take the risk’, – he answered. In situations like this, leaving treats for the spirits is seen as a way of negotiating with the spirits of the territory. As it is not possible to predict the rockfall and it can happen at any moment, locals try to search for cooperation with the forces of nature. In this way, they exercise their agency by direct negotiating, such as bringing treats or performing rituals.

Close connections of residents with the land influence their perceptions of jade extraction. As my interviewees articulated, it is considered important to follow a set of rules when extracting jade, and these rules are similar to those held by hunters (Interview B4). ‘Jade does not like those who are greedy’, – one of the interviewees told me indicating that the stone may bring bad luck to those who do not respect it and take too large amounts at once (Interview B7). Another informant was worried about the level of illegal jade extraction and trade: ‘This greed would not bring anything good to the community’ (Interview B25). Therefore, the informal rules of extracting jade reflect the general attitudes of residents to land and resources. Jade is viewed as an animated entity that may bring good or bad luck to its miners depending on their behaviour. The extraction of gold also becomes related to local spiritual relations with the land, and the development of gold extraction in Oka is viewed as a possible danger for the land as well as an offence towards its spirits.

The attitudes to jade extracted in Buriatia are complex. The locals often claim that they see no value in jade per se and do not understand why it is so appreciated in China (Interview B4). Some of the residents use pieces of jade for sauna ovens, as jade steam is considered especially pure (Interview B10), but otherwise, I could not trace any examples of practical use of jade in the community. The interviewees note that until the early 2000s when the demand for jade in China increased nobody needed the stone (Interview B5). At the same time, many locals keep small pieces of jade at home and are ready and proud to show them to their guests (Interview B11, B30). These pieces are the ones they found or extracted when organizing a jade trip, but not valuable enough to be sold. I had the impression that these pieces are kept at homes similarly to hunting trophies or souvenirs, to illustrate the owner’s courage and luck. As jade trips are often linked to risk-taking, keeping pieces of jade at home indicates that the jade’s owner has managed to overcome all the risks and challenges and has not returned empty-handed.

The resourcescape of Oka, therefore, reflects a complex entanglement of various forms of natural resource extraction. The extraction (or picking) of jade, which has started relatively recently has become integrated into previously existing forms of subsistence hunting or fishing. Nowadays, it follows a similar logic, first and foremost respect for the resource and its sustainable use to avoid overharvesting. Other similarities between different forms of resource extraction include the concepts of luck as one of their organizing principles, the ‘hunting trophies’ as reminders of previous trips, the risks associated with the activity, and, finally, the demonstration of strength and masculinity through overcoming dangers. The line between these forms of extraction is, therefore, blurred, even though for the state these activities are divided into ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’. Both informal jade mining and other forms of extraction are embedded into the perceptions of the sacred landscape and sustainable use of resources in Oka.

Conclusion

In both case studies discussed in this article, the concept of resourcescape stresses connectivity between humans and various forms of resource extraction, such as mining, hunting, fishing, berry-picking, or tourism. In Veps and Soiot settlements, stone mining has become an activity deeply rooted in the landscape. Stone legends praising famous destinations of Karelian diabase and quartzite and Siberian graphite reinforce local connections with the territory. At the same time, the activities of private mining enterprises generate concerns in both communities. Private companies are viewed as outsiders taking possession of local resources and taking them away to unknown places without informing the residents or collaborating with them.

Other types of extractive activities, such as tourism, generate similar concerns in Karelia. The residents of Veps villages claim that tourist companies appropriate the shore of Lake Onega and use local natural resources to attract tourists from federal centres. In this sense, both private mining and tourism development reinforce the peripherality of Veps villages and strengthen the alienation of Veps from their natural resources. In Veps villages, stones were traditionally viewed as connecting points, either between humans and masters of territory (ižandad) or between Prionezhie and famous destinations of diabase and quartzite. Veps mining brigades brought the extracted stone to other parts of the country and thus expanded the local resourcescape far beyond their home villages. Nevertheless, these connection types are currently ruptured, and therefore the Veps resourcescape has become fragmented as interrelations inside it loosen. While the residents of Veps villages feel distanced from their stone, they simultaneously experience a lack of control over their lakeshore territory and fishing resources.

While the resourcescape of Veps villages has been strongly impacted by the Soviet state and the development of a large-scale stone mining industry, in Oka in Buriatia, due to its remote location, state influence has been more subtle. Just as Veps miners used to travel to other regions and build ties with the outside world, Oka residents have been submerged into intimate connections with the more-than-human landscape while being occasionally disturbed by outside influences such as Alibert’s mining enterprise. The presence of mining in contemporary Oka is fluid and uncertain, as graphite extraction is long in the past, the local involvement in gold mining is limited, and jade extraction is largely kept secret. Here, rather than radically changing human – landscape relations as it has happened in Veps villages, jade mining is embedded in the existing bonds between human and nonhuman actors. As a result, mining does not symbolically dominate the local resourcescape but rather integrates into it, following the established logic of interactions with the landscape.

In both cases, residents claim their ownership and knowledge of natural resources. In Veps villages in Karelia, local ties with the stone industry are an important factor in identity construction. Mining is not viewed as an alien activity but instead is entangled with other traditional Veps activities, such as fishing on Lake Onega, and many mining workers simultaneously engage in fishing as a free-time activity. However, the privatization of mining enterprises, similar to lakeshore appropriation by tourism companies, has increased Veps alienation from both activities. In Buriatia, the engagement of Soiots and Oka Buriats in informal jade extraction is caused by their limited opportunities to be formally employed in mining. By extracting jade, Soiots and Oka Buriats question the established state narratives and reinstate their symbolic ownership over natural resources. The process of jade extraction follows a set of rules similar to hunting (e.g. the prohibition of taking too much from nature or perception of both as men-dominated activities). In this sense, the relatively new business of informal extraction abides by the established patterns of communication with non-human actors.

The concept of resourcescape views mining activities through their embeddedness in human-landscape relations, when mining is not necessarily viewed as a less sustainable form or extraction in comparison to other forms of obtaining resources. Through using resourcescape as an umbrella term for an array of human – resource relations, the article brings attention to the voices and perspectives of Indigenous and local residents, as both communities discussed in this article are excluded from decision-making with regard to the development of their territories. Due to their long-term experiences of interacting with the landscape, however, they possess deep knowledge of sustainable resource use. Their traditional practices of extraction rely on respect for the resource, avoidance of overharvesting, and the creation of strong ties between the resource and its producers. Both communities wish to participate in resource extraction on equal terms as local knowledge holders. However, the residents’ perspectives in Prionezhie and Oka are repeatedly not taken into account in extraction activities, local participation is limited, and private businesses are viewed as alien forces not investing in the settlements’ well-being. In this situation, forms of extraction – including mining, fishing, and tourism, – do not align with local understandings of sustainable resource use and thus strengthen the peripheral position of indigenous minorities in the Russian state.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Varfolomeeva

Anna Varfolomeeva is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science, University of Helsinki. Her postdoctoral project focuses on indigenous conceptualizations of sustainability in industrialized areas of the Russian North and Siberia. Anna received her PhD (2019) at Central European University in Budapest. She is the co-editor of the volume Multispecies Households in the Saian Mountains: Ecology at the Russian – Mongolian Border (2019) and has published on indigeneity, human – resource relations, and the symbolism of infrastructure.

Notes

1 Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) issued a statement in support of the Russian war in Ukraine (referred to as ‘special military operation’) on 1 March 2022. However, on 11 March 2022, the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia issued its own statement condemning the position of RAIPON; its members withdrew from all Russia-based indigenous organizations. Similarly, while the Association of Kola Saami supported the war, OOSMO (Public organization of the Saami of the Murmansk region) officially opposed it, and some members of OOSMO had to leave Russia to seek asylum. After the statement of support expressed by the Association of Kola Saami, the Saami Council put on hold all common projects with the Saami organizations in Russia in April 2022.

2 Throughout the article, I use the notion ‘Prionezhie’ to refer to the Veps area in Karelia, and the notion ‘Oka’ as the Soiot and Oka Buriat area in Buriatia. Between 1994 and 2004, Veps villages were separated into a special territorial unit ‘Veps National Volost’ (Veps: Vepsän rahvahaline volost’), but in 2004 the unit was discontinued, and the villages now form a part of the Prionezhskii district.

3 Both diabase and quartzite are commonly referred to as ‘the stone’ by the residents of Veps villages.

4 Petrozavodsk is the capital of the Republic of Karelia; Ulan-Ude is the capital of the Republic of Buriatia.

5 The data collection followed the guidelines and principles of the Central European University Ethical Research Policy (document number: P-1012-1v1805).

6 Within this policy, residents of smaller villages, viewed as ‘villages without prospects’ (Russian: neperspektivnye derevni) were forced to resettle to larger villages or towns.

7 In contrast, Yuri Koren’kov, former director of the Soviet-time enterprise in Kvartsitnyi settlement, is portrayed in the interviews as a person having equal status to ordinary workers: living in a similar house, engaging in the same activities, and knowing most of the workers personally.

8 Nomadic pastoralism is a form of pastoralism when livestock are herded in order to find fresh pastures on which to graze, following an irregular pattern of movement.

References

- Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity al large: Cultural dimensions of globalization (Vol. 1). University of Minnesota Press.

- Bessonov, A. (2022). Russian ethnic minorities bearing brunt of Russia’s war mobilization in Ukraine. Canada Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). October 5. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/russia-mobilization-ethnic-minorities-buryat-1.6605501.

- Bruno, A. (2018). How a rock remade the Soviet North. Nepheline in the Khibiny Mountains. In N. Breyfogle (Ed.), Eurasian Environments: Nature and ecology in imperial Russian and Soviet history (pp. 147–164). University of Pittsburg Press.

- Büscher, B., & Davidov, V. (2013). Introduction: The ecotourism-extraction nexus. In B. Büscher, & V. Davidov (Eds.), The ecotourism-extraction nexus: Political economies and rural realities of (un)Comfortable bedfellows (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

- D’Angelo, L., & Pijpers, R. J. (2018). Mining temporalities: An overview. The Extractive Industries and Society, 5(2), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2018.02.005

- Davidov, V. (2017). Long night at the Vepsian museum: The forest folk of northern Russia and the struggle for cultural survival. University of Toronto Press.

- Donahoe, B. (2011). On the creation of indigenous subjects in the Russian federation. Citizenship Studies, 15(3-4), 397–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2011.564803

- Dorzhieva, G. (2014). Pik Alibera (Frantsiia) i doroga Alibera (Rossiia, Buriatiia) – vremen sviazuiushchaia nit’. Vestnik Irkutskogo gosudarstvennogo tekhnicheskogo universiteta, 7(90), 190–194.

- Engelman, R. (2013). Beyond sustainababble. In State of the world 2013 (pp. 3–16). Island Press. https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-458-1_1

- Ey, M., & Sherval, M. (2016). Exploring the Minescape: Engaging with the complexity of the extractive sector. Area, 48(2), 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12220

- Ferry, E., & Limbert, M. (2008). Introduction. In E. Ferry, & M. Limbert (Eds.), Timely assets: The politics of resources and their temporalities (1st ed., pp. 3–24). School of Advanced Research Press.

- Funk, D. A. (2018). The “resource curse” phenomena in post-Soviet Siberia (Russia): Anthropological perspectives. Sibirskie Istoricheskie Issledovaniia, (2), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.17223/2312461X/20/5

- Gilberthorpe, E. (2007). Fasu solidarity: A case study of kin networks, land tenure, and oil extraction in Kutubu, Papua New Guinea. American Anthropologist, 109(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2007.109.1.101

- Gishardaz, F., & Chernykh, A. (2017). Rol’ frantsuzskogo predprinimatelia Zhan-Polia Alibera v razvitii poznavatel'nogo turizma v Baikal'skom regione. Evroaziatskoe sotrudnichestvo: gumanitarnye aspekty, (1), 32–41.

- Graham, N. (2010). Lawscape: Property, environment, Law. Routledge-Cavendish.

- Hicks, S. (2011). Between indigeneity and nationality: The politics of culture and nature in Russia’s diamond province [Doctoral dissertation]. Department of Anthropology, University of British Columbia.

- Hirsch, E. (1995). Landscape: Between place and space. In E. Hirsch, & M. O’Hanlon (Eds.), Anthropological studies of landscape: Perspectives on space and place (pp. 1–30). Clarendon Press.

- Korablyov, N. (1999). Razvitie postoiannoi torgovli v Sheltozerskom krae vo vtoroi polovine XIX veka. In I. Vinokurova (Ed.), Vepsy: Istoriia, kul’tura i mezhetnicheskiie kontakty (pp. 80–85). Izdatel’stvo Petrozavodskogo Universiteta.

- Kostin, I. (1977). Kamennykh del mastera. Karelia.

- Kurs, O. (2001). The vepsians: An administratively divided nationality. Nationalities Papers, 29(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905990120036385

- Larsen, D. R. (2022, April 10). Samerådet stopper alt samarbeid med samiske organisasjoner i Russland. Norsk Rikskringkasting (NRK). https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/samarbeidet-med-samiske-organisasjoner-i-russland-stoppes-1.15927907.

- Liarskaya, E. (2017). Where do you get fish? Practices of individual supplies in Yamal as an indicator of social processes. Sibirica, 16(3), 124–149. https://doi.org/10.3167/sib.2017.160306

- Nadasdy, P. (1999). The politics of TEK: Power and the “integration” of knowledge. Arctic Anthropology, 36(1/2), 1–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40316502

- Nadasdy, P. (2005). Transcending the debate over the ecologically noble Indian: Indigenous peoples and environmentalism. Ethnohistory, 52(2), 291–331. https://doi.org/10.1215/00141801-52-2-291

- Nikolaeva, S. (2017). Post-Soviet melancholia and impossibility of indigenous politics in the Russian North. Arktika XXI vek. Gumanitarnye nauki, 2(12), 12–22.

- Pavlinskaya, L. (1999). Vostochnye Saiany i etnicheskie sud'by korennykh narodov. In L. Pavlinskaya (Ed.), Etnos, landshaft, kul'turа (pp. 60–75). Evropeiskii Dom.

- Pavlinskaya, L. (2002). Kochevniki golubykh gor. Sud'ba traditsionnoi kul'tury narodov Vostochnykh Saian v kontekste vzaimodeistviia s sovremennost'iu. Evropeiskii Dom.

- Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, A. (2014). Spatial justice. Routledge.

- Puura, U., & Tánczos, O. (2016). Division of responsibility in karelian and veps language revitalisation discourse. In R. Toivanen, & J. Saarikivi (Eds.), Linguistic genocide or superdiversity?: New and old language diversities (pp. 299–325). Multilingual matters.

- Richardson, T., & Weszkalnys, G. (2014). Introduction: Resource materialities. Anthropological Quarterly, 87(1), 5–30. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2014.0007

- Schimanski, J. (2015). Border aesthetics and cultural distancing in the Norwegian-Russian borderscape. Geopolitics, 20(1), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.884562

- Soja, E. (2006). Foreword: Cityscapes as cityspaces. In C. Lindner (Ed.), Urban space and cityscapes: Perspectives from modern and contemporary culture (pp. xv–wviii). Routledge.

- Sörlin, S. (2020). Is there such a thing as ‘best practice’? Exploring the extraction/sustainability dilemma in the Arctic. In D. C. Nord (Ed.), Nordic perspectives on the responsible development of the Arctic: Pathways to action (pp. 321–348). Springer.

- Southcott, C., & Natcher, D. (2018). Extractive industries and Indigenous subsistence economies: A complex and unresolved relationship. Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue Canadienne d’études Du Développement, 39(1), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2017.1400955

- Strogal’schikova, Z. (2014). Vepsy: Ocherki Istorii i Kul’tury. Inkeri.

- Sulyandziga, L., & Sulyandziga, R. (2020). Russian federation: Indigenous peoples and land rights. Fourth World Journal, 20(1), 1–19. doi:10.3316/informit.273811531265701

- Tysiachniouk, M., Henry, L. A., Lamers, M., & van Tatenhove, J. P. M. (2018). Oil extraction and benefit sharing in an illiberal context: The nenets and komi-izhemtsi indigenous peoples in the Russian Arctic. Society & Natural Resources, 31(5), 556–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2017.1403666

- Varfolomeeva, A. (2020). Lines in the sacred landscape. Sibirica, 19(2), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.3167/sib.2020.190203

- Vinokurova, I. (1994). Kalendarnye obychai, obriady i prazdniki vepsov. Rossiiskaia akademiya nauk.

- Vinokurova, I. (2015). Mifologiia Vepsov: Entsiklopediia. Izdatel’stvo Petrozavodskogo Universiteta.

- Virtanen, P. K., Siragusa, L., & Guttorm, H. (2020). Editorial overview: Indigenous conceptualizations of ‘sustainability’. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 43, 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.04.004

- Wagner Tsoni, I. (2019). Affective borderscapes: Constructing, enacting and contesting borders across the southeastern mediterranean [Doctoral dissertation]. Department of Global Political Studies, Malmö University.

- Zhukovskaya, N. (2005). K istorii soiotskoi problemy. In N. Dashieva (Ed.), Etnicheskie protsessy i traditsionnaia kul'tura (pp. 4–19). Izdatel’sko-poligraficheskii kompleks VSGAKI.