ABSTRACT

This article examines a form of activism in Myanmar that emerged after the 2021 coup: solidarity art, wherein art is sold overseas and the proceeds returned to the artists that produced it. Myanmar’s solidarity art demonstrates a new version of the phenomenon, where digital transmission replaces older modes of distribution, and the artwork is displayed publicly. While artwork of this nature may be useful, it requires interrogation because of the potential for imbalance between the producer and consumer – in this case between the Global South and the Global North. In this article, I review critiques of this art and its well-intentioned siblings, humanitarianism and advocacy. I then identify three elements of Myanmar’s transnational solidarity art that mitigate concerns about potential North/South imbalances – multiple transnationalisms, collective self-representation, and resource reciprocity. This newest form of solidary art, I conclude, can play a generative role in supporting transnational human rights activism.

Introduction

On 1 February 2021, the chief of Myanmar’s military, General Min Aung Hlaing, staged a coup against the democratically elected government. No strangers to authoritarianism nor to resistance against it, the people of Myanmar – ethnic nationalities who have continually struggled for recognition, workers and labour activists, middle-class Gen Z who have been raised on a decade of the discourse of democracy, and old-school dissidents who remember well the shadow of five decades of the prior junta – engaged in an astonishing number of forms of anti-coup protests in response. These creative and courageous expressions of dissent were filmed, recorded, and, thanks to the internet, projected internationally, often with the hashtag #WhatIsHappeningInMyanmar. A growing tome of popular writing about the coup and its responses now exists. One can glean coverage of Myanmar’s protest art across mainstream Western media (Beech, Citation2021; Hayes, Citation2021; Tan, Citation2021), regional media (Duncan, Citation2021; Thu Ra Kyaw et al., Citation2021; Win, Citation2021) and niche arts publications (Cascone, Citation2021; Coyer, Citation2021; Htet et al., Citation2021; Johnston, Citation2021; Movius, Citation2021; Smith, Citation2021). Coverage has also been given to Myanmar’s poetry (Byrne, Citation2021).

This article examines one form of Myanmar protest that has materialized in the transnational realm. I write of art produced by Myanmar artists, who then send the digital versions of these works overseas, where they are printed, hung, shown, and sold, with the proceeds returning to the artists who produced them, many of whom remain in Myanmar. This form of art is not a new phenomenon; in intent and transnational character, it describes solidarity art, defined by Jacqueline Adams as ‘art made by individuals experiencing state violence and economic hardship, which others distribute, sell, and buy to express solidarity with the artists and give them financial support’ (Citation2013, p. 2). Adams’ extensive coverage of arpilleras – Chilean-made cloth pictures depicting the political and economic violence of the Pinochet dictatorship – offers a crucial backdrop on which to build the examination in this article. In the case of Myanmar, the art has been sent digitally, rather than smuggled out physically, and it has been shown in highly public spaces, magnifying the possibility to broadcast the repression of the Myanmar regime. This is, then, a new form of solidarity art, although the primary elements that comprise the phenomenon remain much the same.

I analyse this new form of solidary art in the article that follows. First I review the phenomenon of resistance art, sketching the literatures that speak to the intersection of art and, broadly defined, social justice. Solidarity art is a subset of this, and I cover it also. I then synthesize the literatures that show that resistance art and its well-intentioned siblings, humanitarianism and advocacy, all run the risk of reinforcing the power relationships they purportedly seek to dismantle. What, then, are we to make of art that rests at the intersection of these phenomena? Drawing on analyses of works featured in a travelling Myanmar exhibit, Fighting Fear, I identify three aspects of solidarity art in Myanmar that, taken together, provide a corrective to a potentially worrying Global South/North divide. This newest form of solidary art, I conclude, can play a generative role in supporting transnational human rights activism.

Interrogating art and activism

The use of art as a means to address lacunae in social justice has been documented in a range of literatures through a range of art forms. Fine art that documents difficult pasts can deny repressive states the chance to perform historical amnesia (Dirgantoro, Citation2020). Performance art can articulate individual and historicized traumas for those who have endured social justice violations (Schlund-Vials, Citation2017). Creative writing has the power to redistribute the targets of public attention, making exploited subjects visible, in fiction (Shapiro, Citation2015) and film (Opondo & Shapiro, Citation2019). All of these fall under the category of resistance art, wherein artists express resistance against a repressive government (Adams, Citation2013, p. 15). Solidarity art, as a subset of resistance art, returns the proceeds to the artists. Further, those who purchase the art are not simply buying in order to possess an object, but in order to express solidarity (Adams, Citation2013, p. 166). Adams notes that the solidarity chains that link local artists with those in the international arena radiate not just the art, but the messages behind it (Citation2013, p. 163). Further, the solidarity flows that move in the opposite direction – returning something to the original artists – deliver not just money, but moral support and information (Adams, Citation2013, p. 164). Solidarity chains and solidarity flows are part of a system of production and distribution that have the potential to magnify critique of a repressive regime, but they may also be part of a problem of imbalance, as described below.

Art can be a form of resistance, and it can also be a form of healing. In the field of human rights, the process of creating art has been noted as a means by which the victims of trauma work through the experience with the hope that the artmaker is released from the pain of difficult memories, expressing the past not as a mimetic replica, but as a visual statement that the experience is, in fact, unrepresentable (Guerin & Hallas, Citation2007, p. 8). Further, expression through art can help people to seek answers to individual and collective human rights abuses beyond the rational and linear, without compelling victims to relive their trauma in the process of representing it (Atkins & Eberhart, Citation2014; Knill et al., Citation2005; Lederach, Citation2005; Levine & Levine, Citation2011). Its power is both healing and demanding attention – allowing survivors of trauma to resist against the feeling of disempowerment to demand alternatives to abuse witnessed and suffered. Artistic expressions that bear witness to human rights violations also ‘open up forms of witnessing that create alternative juridical spaces, rendering judgments without issuing punishments, … (doing) what legal and campaign testimony cannot, in acknowledging the moral complexities of human rights abuse’ (Jensen & Jolly, Citation2014, p. 5). In other words, art is transformative in human rights both for the way it broadens legal approaches to affective ones, and also for its potential to straddle physical domains: from the proverbial courtroom to the rooms of a gallery.

In a related field, the sphere of transitional justice and the space it provides for memorializing past atrocities have enabled artists to use creative approaches to consider ways to collectively heal from injustices. (d’Evie, Citation2014; McLeod et al., Citation2014). In retelling the painful narratives that defined periods of injustice, artists have unique opportunities to reclaim the physical and ideological space – building on a Foucauldian concept of heterotopia – needed to repair continuing cleavages in a post-revolution or post-conflict state (Kurze, Citation2019). The use, and, critically, the revival of art as a form of social commentary in transitional countries represents not just a powerful form of recollection and raising awareness, but a means by which a country and its people performatively return to a state that has the time and inclination to respond to and appreciate the richness and beauty of, in the case of Cambodia, dance, music and fine arts (Jeffery, Citation2021).

Finally, art in all its forms plays a role in critical social commentary. I will not cover the extensive literature on art and awareness-raising here, but instead offer some examples of its operationalization in the digital era, as new technologies have significantly increased the efficacy and reception of artworks produced by activists on a global scale. Beginning in the Middle East in 2011, ‘The Year of Revolutions’ sparked not only resistance against oppressive governments from Tunisia to Egypt to Syria thanks to the arrival of broadband services, but also the resistance art that accompanied it. Street art dominated the resistance in Arab States. Murals, photographs and videos that documented the protests reached worldwide audiences through the use of social media. Marwan Shahin, an illustrator and designer based in Egypt, produced street art that would later become synonymous with the resistance against the ousted Egyptian President, Hosni Mubarak. The image of Tutankhamun wearing a Guy Fawkes mask was an indication of the visible and visceral manipulation of known art pieces (ancient archeological icons and the film V for Vendetta, respectively) and one that was adopted by street protestors (McQuiston, Citation2019, pp. 218–219).Footnote1

Resistance art played a similar role during the Umbrella Revolution in Hong Kong. The protest group ‘Occupy Central with Peace and Love’ set up encampments in the central part of the city, holding umbrellas and blocking transport and thoroughfares (McQuiston, Citation2019, p. 228). As well as being recognized by umbrellas and the adornment of yellow ribbons, the colour of universal suffrage, protesters became renowned for impromptu art pieces during the height of the protests. Solidarity posters began appearing on the internet, and large public sculptures were visible at the site of resistance in the city. One famous example was Umbrella Man, a 3.6m tall sculpture made of wood that stood at the centre of the protests. Even after the statue was removed and the protest site closed, online images of it have facilitated an enduring reminder of those struggles, demonstrating the power of digital technology to mobilize and materialize solidarity and support through the reception of art (McQuiston, Citation2019, p. 228), something to which I return later.

For all of art’s potential to address social justice issues, its utility as a form of activism is fraught. The certification and approval of art by institutional forces may mean the loss of the art creator’s autonomy, and, if Robertson is to be believed, his or her metaphorical life blood. Museums and galleries, as she asserts, ‘act vampirically, encouraging the creation of subversive work, sucking the active opposition out of it, and leaving an empty shell that nevertheless conveys a sense of edginess upon the institution’ (Citation2011, p. 474). The need for art to seek value through the eyes of others even if not displayed in a museum – buyers, intermediaries, viewers – can be similarly problematic, particularly when that power imbalance is overlaid with the fact that the social justice issues that instigated the art remain. As noted, solidarity chains and solidarity flows move a range of resources in different directions, but when the solidarity art system is too focused on the financial value of the sale of the work, the art itself can be compromised (Adams, Citation2005).

A different set of power imbalances problematize representations of bodily suffering, whether called art or not. An extensive literature critiques humanitarian and media organizations for their creation and manipulation of images in ways that simplify victim identities and reinforce inequalities along a range of vectors: rich and poor (Maddox, Citation1993); Global North and Global South (Chouliaraki, Citation2013); and citizen and refugee (Johnson, Citation2011). Whether graphic imagery effectively attracts the sympathy of powerful/rich stakeholders in the Global North (Hagan, Citation2010) or generates ‘compassion fatigue’ (McLagan, Citation2006) or overwhelms and paralyzes even the best-intentioned actors (Szörényi, Citation2006), the humanitarian and media regimes’ respective hunger for resources, attention, and viewership ensures that art used in the service of those regimes is a panacea neither for awareness-raising nor for explicit policy change.

This ‘hunger’, is, of course, structural; this is not necessarily a critique of artworks themselves, although it can be (Schuck et al., Citation2013). Likewise, humanitarian and advocacy aid organizations based in the Global North with well-intentioned motivations for improving rights or livelihoods still possess, whether they acknowledge it or not, an institutional survival drive that ensures that strategies that support the organization are highly prioritized, to the potential exclusion of respectful and reciprocal relationships with those they seek to support (Banki & Schonell, Citation2018; De Waal, Citation2010; Duffield, Citation2001). Critiques of the Global North/Global South divide in relation to development, humanitarianism and human rights advocacy are far too vast to cover here, but the colonial, imperial, and unreflective tendencies they reveal risk being mirrored in situations where art and activism intersect. The following sections interrogate these charges as they relate empirically to the recent work of artists and artwork from Myanmar.

Myanmar art: home and away

In the ten years that preceded the February 2021 coup in Myanmar, the country, especially the urban centres of Yangon and Mandalay, produced a lively art scene. Building on centuries of homage to art in the form of sculpture, puppetry, and, in the twentieth century, photography (Condee, Citation2011; Sadan, Citation2014; Skidmore, Citation2005), Myanmar’s art flowered. As noted in Painting Myanmar’s Transition, a book that remarkably showcases 80 artworks and the artists who have created them, a wide temporal scope characterized Myanmar painting during this transitional time. Looking backward, for example, one artist portrayed the monks’ 2007 campaign of resistance. Focused on the present, artists depicted both the city and countryside in times of transition. And while few paintings were oriented toward the future, the interviews, rather depressingly and presciently, focused on the continuing overpowering presence of the military (Holliday & Myat, Citation2021).

Following the coup, that art scene found outlets elsewhere. On the one hand, creative expression thrived in the public eye in the weeks following the coup, with well-documented performative protest taking front stage in the form of culturally subversive posters, costumes, and dances (ArtForum, Citation2021). On the other hand, artists whose work was clearly supportive of the anti-coup movement were increasingly targeted and had to go into hiding (Beech, Citation2021). Art workshops held at Myanm/art, a contemporary art space in Yangon, and attended by artists, writers, and journalists, provided a means of self-care, and were carried out clandestinely (Pyae, Citation2021). Due to an increasingly aggressive military response, the public displays of protest art later receded from public view within Myanmar, mirroring past moments of censorship and selective patronage of the arts in the country (Carlson, Citation2016).

A good deal of creative expression, including Myanm/art, then moved into the transnational realm, with its director organizing a travelling exhibition, Fighting Fear, which has been showcased in Sydney and Paris, and which allowed buyers the chance to purchase the art to send back to the artists.Footnote2 As noted, the radiating effect of this artwork mirrors the solidarity art of Chile’s arpilleras, with a few important exceptions: first, as noted, the advance of technology has enabled the digital movement of both art and money, allowing for more fluid resource flows. Second, Chile’s artists were very often the poorest women from rural areas, and this was reflected in the subjects they illustrated, which was often the deep poverty of their lives, exacerbated by the abuses of the Pinochet dictatorship. By contrast, the people who could attend workshops at Myanm/art were by definition those who could afford to live in Yangon and were therefore at the very least, middle class urbanites. The content, as described below, reflected this.

In the coming pages I describe the art in Fighting Fear and the events associated with it – a practice that constitutes a new form of solidarity art – through three characteristics that, together, further the role of resistance activism and temper concerns about its international projection.

Multiple transnationalisms

Transnationalism, as a form of crossborder movement that works outside of state-to-state relations, is a vehicle through which images, art and activism flow regularly.Footnote3 From the oft-cited boomerang model (Keck & Sikkink, Citation1998) to a rich diaspora mobilization literature (Betts & Jones, Citation2016; Koinova, Citation2021; Quinsaat, Citation2019), transnationalism helps to explain a range of strategies and channels for cross-border action. The Fighting Fear exhibition is an obvious example of the transnational movement of image and emotion, materializing the sentiments felt during the height of protests in Myanmar. In line with Koinova, the coup represented a ‘critical juncture’ – an event that disrupted current state power structures – following which transnational activism was a logical outcome. Koinova suggests that the strength of such conflict-generated diaspora activism is contingent on ‘contextual embeddedness’, wherein diaspora actors’ potential for mobilization is linked to the ‘sociospatial’ characteristics of the diaspora community – that is, its position of status within the host state, and that host state’s position within a regional/global architecture of power (Citation2018).

Transnational resistance art, however, finds new avenues for establishing relevant (embedded) contexts. Rather than relying on diaspora communities to be the loci of transnational social fields (Levitt, Citation2009), I suggest that the art itself becomes the locus by projecting its status through its cultural, political, and aesthetic relevance. The very symbol of the now-famous three-fingered salute, whose origins in a movie produced in the Global North, and then adopted in Hong Kong, Thailand and now Myanmar, is a stirring example of a new kind of sociospatial power. When the salute is repeated and ritualized, it becomes what Dobson and McGlynn (Citation2013) point to as the performance of contemporary activism. Caught in transnational spaces, such performances move in ‘myriad directions at once, playing the dual roles of “protest art” where provocation and witticism are visible in portable mediums such as signs and banners, and the “art object”’ (Dobson & McGlynn, Citation2013, pp. 11–12). Indeed, transnational audiences mean that the artwork risks being subject to different narratives and interpretations, including, but not limited to, examinations of design, perspective, and artistry.

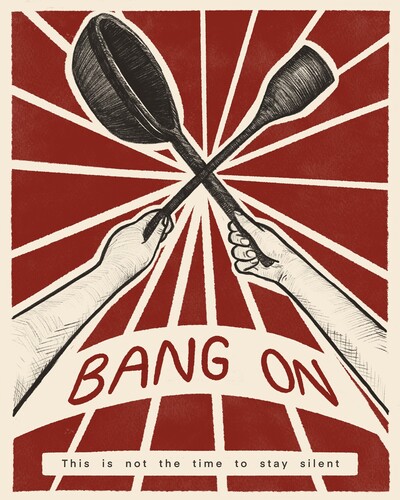

The Fighting Fear exhibition demonstrates these multiple transnationalisms through its subjects and broader messages. Its most recognizable series, We Make Art in Peace, by Kyaw Htoo Bala and other artists, features a dove flying above diverse versions of the three-finger salute whose varying colours and shapes seem to represent different ethnicities and ages – a resonant transnational reminder of protest. Similarly, the posters of Thee Oo Thazin illustrate numerous ways that ideas, ideologies, and icons defy and operate around and across nation state borders. The artworks in this series contain beige lines striking through a rusty red background, evoking the constructivist art of the Soviet revolution, representing protest and resistance. The messages themselves suggest movement and mobilization: in Bang On, hands hold a wooden spoon and pan, highlighting the noisy nightly protest of banging pots of pans, a tactic to drive away bad spirits, and reminiscent, whether its executors knew it or not, of Latin American protests of the 1970s (Oo, Citation2021). In Circulate, the word ‘Circulate’ sits atop a mobile phone, potentially our planet’s most transnational instrument. These artworks further addressed multiple audiences. Thazin’s artwork was presented in tandem in English and Burmese, clearly asserting the importance of appealing to, and valuing, both viewers at home in Myanmar and those in the international sphere ().

Following Tarrow, these posters represent the cosmopolitan aspects of publics that can play simultaneous roles as transnational activists, transnational audiences, and transnational consumers (Tarrow, Citation2005). They also highlight the relative cosmopolitan character of the artists themselves. After all, Thee Oo Thazin is herself a cosmopolitan, transnational subject, having studied in Singapore, and thereafter returning to Myanmar. She is, therefore, both place-based and place-bound (Dirgantoro, Citation2020, p. 302). Her representations of Myanmar thus straddle the Global North-South divide – a divide marked so clearly in this region of the world by resources and not geography; Singapore after all is south of Myanmar. Thazin could then be criticized for her outside-in orientation, much like other people from Myanmar outside the country.Footnote4 We may ask, then, does Thee Oo Thazin’s work flip dominant discourses produced by the global human rights regime, with its unequal distribution of varying forms of capital and humanitarian narratives infused with neo-colonial ideologies? On the one hand, one might argue that her work relies on the institutional support of actors in the Global North such as the school she attended in Singapore (LaSalle College of the Arts). On the other hand, the artwork she showcased in the Fighting Fear exhibit effectively challenges assumptions about subjects in Myanmar. For example, the mobile phone, potentially understood by the Global North as a sophisticated tool of the upper class, is seen everywhere in Myanmar, even among the lower classes. That Thee Oo Thazin foregrounds the smartphone to give autonomy to the user through the spread and access of images and information, as a way to reflect on the flattening of global information hierarchies, is a means by which to flip the script for those still in the country.

Thazin’s choice to portray not people but themes and messages similarly imbues her work with, I argue, an effort to equalize the inside-outside imbalance, and disrupt simplistic understandings of Myanmar’s people and democratic processes. More broadly, Fighting Fear’s works were reproduced and disseminated through global exhibitions that truly focused on that phrase whose currency has only grown over time: what is happening in Myanmar, i.e. not to those from Myanmar. The transnational power of these artworks lies not in the position of any one artist, but in the themes present in the art, and in the comprehensive ways in which the artworks hold their transnational themes.

Collective self-representation

There is no shortage of art produced about human rights violations. Emotive photographs of the suffering of human rights victims adorn the walls of United Nations buildings and photography prizes regularly award top kudos for the photograph that best captures a moment of suffering. A 2015 exhibit by the Agence France-Presse highlighted the dual suffering and agency of the Rohingya (Yeung & Lenette, Citation2018). And yet, the creators of such art are often not borne of that suffering themselves. It is not at all a foregone conclusion that representations of those who require support from advocacy or humanitarian agencies have the resources (material, relational, political) to represent themselves. It is thus worth noting when art that aims to raise awareness is produced exclusively by the community in question. I term this collective self-representation to showcase the fact that such artists re-appropriate stories and narratives that had heretofore been captured by outsiders. Of course, the notion of a ‘collective’ in Myanmar is deeply fraught. There are a bewildering number of soft multichotomies that suggest that we cannot paint those who have suffered at the hands of the military as one community. There are divides based on majority/multiple ethnic nationality positions (Jones, Citation2014). There is the everpresent question of elite vs. non-elite status (Hong & Chun, Citation2021; Woods, Citation2020). Social class is an enduring issue, one that heavily shapes the ways in which Myanmarese civil society expresses resistance (Prasse-Freeman, Citation2012; Ra & Ju, Citation2021). Indeed, as noted, the artists described here do not represent the lower class rungs of society. There is intra-Rohingya fracturing along questions of identity statehood (Prasse-Freeman, Citation2022). And, as in countless cases noted in refugee studies where there is tension between those who have ‘stayed’ and those who have ‘left’, there are branches of tension between those in Myanmar, those who reside in the near diaspora, and those who have made their homes further afield (Williams, Citation2012). Nevertheless, I assert that at this moment, one can differentiate between those who are from Myanmar and non-Myanmarese. While not every artist is engaged in self-portraiture, those who exhibit in Fighting Fear portray the harms done to people from the country of the birth, where the memory of past harms lies not in history books or NGO reports, but in the bodies of family and loved ones. This ‘corporeal vulnerablity’ – an aspect of precarity associated with those exposed to conflict (among other things) – effectively creates a collective of artists who resist oppression through self-representation (Lobo, Citation2021, p. 4620).

This is, of course, the case with the artworks showcased in Fighting Fear. These artists have reclaimed a voice that is recalcitrant not only to the military coup and its oppressive tactics, but also to the gaze of the West in viewing and responding to images of suffering. Keysar’s notion of spatial testimony is relevant here. Through ‘do-it-yourself’ aerial photography, activist artists practiced a form of resistance against discriminatory urban planning policies in East Jerusalem. Here, the activists’ choice to use kite photography to generate political action from near real-time imagery of local urban construction conveyed the embodied process of activism and the ways in which it created new forms of testimony, witnessing and public action. Creativity and experimentation with the art form, Keysar notes, is key to the way that spatial testimony allows its creators to be owners of their activism (Citation2019, pp. 523–528).Footnote5

Similarly, on the streets of Yangon in the days following the coup, artists found countless creative ways to protest, moving between public spaces and social media platforms, with visual, cartoon-like images of the three-finger salute, projected by activists on buildings throughout the city on the evenings of the protests, as a way to infiltrate zones that were increasingly restricted following the military coup (Beech, Citation2021). Thus the creative processes developed by resistance artists in Yangon represented a transformation of public space from sites of protest and abusive counter-protest during the day to truth-telling imagery by night.

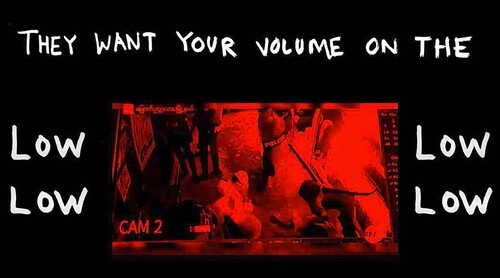

In Fighting Fear, spatial testimony takes on new meaning as a form of self-representation. One of the most visible examples of this was Artist 882021s video LEE 199.Footnote6 LEE 199 features video clips of the coup and its violent fallout, overlaid with reverberating hip-hop beats that evoke clarion calls for racial and economic justice. This mirrors a style used by the musical artist Dre, whose video Captured On A iPhone displays fractured images of protests against police violence in the wake of the death of George Floyd. In LEE 199, the everpresent bass rhythm is accompanied by the refrain ‘Paranoid, 1 Double 9 on my mind’, underscoring the futility of asking the police for help (by dialing 199, the Myanmar emergency call number for police). To the contrary, the viewer is told, ‘They want your volume on the low low … When you speak up they’re gonna shoot you in the tango … Who do we call when the po po committing the crimes? … Might accidentally kill a pig in defense’ ().

Figure 2. 882021, Lee199 (still), single channel video, 2 min 17 sec. Reproduced with the permission of the artist.

These lyrics – and the (I warn you) earworm tune underscoring it – do at least two things to orient the viewer/listener to the artist’s viewpoint. First, and most plainly, they convey the gravity and danger of the anti-coup struggle, with momentary video clips of police violence shaded in a blood-red hue. Second, they complicate assumptions about protestors that might have otherwise positioned them as helpless and exclusively non-violent. This is a key point, because as several scholars of Myanmar have argued, external representations of the country’s activists have been stripped of nuance, with material consequences that produce blatant culprit-perpetrator binaries (Prasse-Freeman, Citation2014) or undermine the possibility for funding and international legitimacy (Brooten, Citation2004). Instead, the artist, by demonstrating the extent to which desperation might lead him to consider violent self-defense, primes the viewer to consider a potentially more realistic narrative about the need for protestors to use weapons, and not just banners (Cheesman, Citation2021).

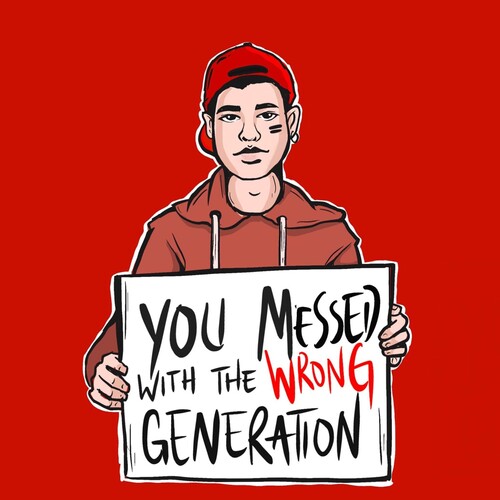

Nuance is the name of the game here. Daring line-drawn images are presented on the screen with video footage of military and police brutality against protesters in the background, the moving images cast under that same red film evocative of blood. In one scene, a line-drawn figure dances on corpses to the sound of the hne, a traditional Burmese instrument used in dances of ancient mythologies and folk tales, its sharp sound cutting through the more familiar (at least to Western audiences) sounds of hip-hop rhythms. Perhaps lost on an international audience, but no less representative for those in Myanmar, is the head of the figure dancing, adorned with a helmet similar to those worn by the police, and its face reminiscent of images of Ravana, a Burmese mythological figure who was believed to be the embodiment of evil (Emery, Citation2021). The video closes with a confident finality with words that really could only come from those within the struggle, and not external to it: ‘To the police & military. You will be held accountable for your crimes. We will not forgive. We will not forget’. There is a truth-telling autonomy here that arguably limits the potential for an international audience to succumb to ‘compassion fatigue’ of witnessing images of suffering, or to view the representations in the video through a purely Myanmar-focused or purely Western-pop culture lens. Neither of these tropes do justice to the complexity of the video. In fact, the entire Fighting Fear exhibition – with representations of powerful young women wielding guns and middle fingers, ethnic Karen demonstrators waving the three-finger salute, and young hip protestors holding ‘You Messed with the Wrong Generation’ signs – contest dominant tropes about gender, ethnic divisions, and tradition in Myanmar today. They do this through the creation of both evidentiary and ludic images (Strassler, Citation2020), wherein the artists use art both as testimony and parody to communicate collective harms done ().

Resource reciprocity

The accessibility of art materials to a broad spectrum of society – paint, photography, technical know-how – has ensured that making art is no longer only the provenance of the wealthy as it was in past centuries. Myanmar, for example, historically hosted a class-based tussle centred on the ability of amateurs and professionals to respectively dabble or work in photography (Sadan, Citation2014). Today, photography as a form of a political action has been called ‘the weapon of the weak’ in relation to Cambodia (Young, Citation2021, p. 5). Despite this, art today, while arguably democratized to some extent, still bears the markings of class and colonialism. Class is still relevant because art materials are still not accessible for the poor. Colonialism retains its power when art is showcased in galleries and museums – frequently the museums that retain vast stores of artefacts taken from former colonies, benefitting economically and culturally from that repository. Along a different sort of imperial line, art galleries and museums serve as the cultural arbiters for what is normatively appropriate for the public to view. Art curators, as ‘reputational entrepreneurs’ can play an oversized role in elevating artists and artworks that mirror the cultural zeitgeist in the curator’s orbit (Braden, Citation2021; Fine, Citation1996).

The transnational and self-representing art that I have described thus far runs the risk of similar colonial cultural co-option when exhibited overseas. After all, viewers in the Global North, far removed from the violence in Myanmar, viewed the exhibit in three quiet and peaceful rooms in Sydney and in a vibrant outdoor space in Paris, embodying the privileged power of the spectator (Sontag, Citation1979/Citation2001). While the subjects of the work suffer the direct impacts of Myanmar’s coup, viewers overseas benefitted from a culturally meaningful experience, and the exhibitors raised their profiles and gained new patrons.

But two processes at play for the Myanmar exhibit suggest an encouraging reciprocity. First, rather than seeking to financially profit from the showing, the Fighting Fear exhibit promised to send all proceeds – minus printing costs – back to the artists who made the art. This return process was communicated in both written and verbal form at the art gallery, in a clear message letting viewers know a way that they could offer support. Importantly, many of the exhibit’s images were available free for download within Myanmar, so that protestors inside the country could print them out to use as posters or banners (Coyer, Citation2021). This is relevant because it shows how much an exhibit in the Global North has the potential to value-add. By returning these funds to the artists themselves, Fighting Fear breaks the colonial chokehold on resources. The Australia leg of the exhibition, for example, raised more than 13,000 AUD that was returned to the artists (John Cruthers, email to author, 22 July, 2021). In Paris, Bart Was Not Here, one of the exhibition’s artists, was public about his intention to return all sales of his artwork to the resistance inside the country (Cabot, Citation2021).Footnote7 While the return of funds to local artists depicting human rights abuses is not unique to this story – solidarity art already possessed this key characteristic (Adams, Citation2013, Citation2018) – the telescoping of this art, and the speed of the exchange points to an increasingly useful form of reciprocity.

Second, the exhibits in both Sydney and Paris included unapologetic awareness-raising and calls to action that were meant to catalyse public response. In Sydney, members of the Burmese diaspora, a researcher from Human Rights Watch, and a university academic (the author) were invited to speak at the exhibit’s (delayed) opening reception. The gallery also posted on its website a powerful speech delivered at the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and Trade by Melinda Tun, an Australian-Myanmarese.Footnote8 In Paris, artists from the exhibit (Richie Htet and Bart Was Not Here) spoke to the media about the role of the international community, and France specifically, in placing pressure on Myanmar. Further, the exhibit was accompanied by a street performance re-enacting arrests by the military, carried out by actors from Myanmar. In both countries, the intentional incorporation of Myanmar voices supported the notion that members of the Myanmarese diaspora function not as victims, but as experts (Banki, Citation2022), offering reciprocity in the form of respect and acknowledgment.

While one could view awareness-raising events like those held in Sydney and Paris as yet more examples of the unhelpful gaze of the Global North (Pussetti, Citation2013), the fact that both exhibits emphasized further action points may quell this charge. In Australia, attendees were encouraged to inform their friends, write to their representatives, donate to one of many Myanmar protest causes, and purchase the art to benefit the Myanmar artists. Coverage of the Paris exhibit by Human Rights Watch linked to several action items: the release of political prisoners, the laying down of firearms by the police, and a call for two oil companies, Total and Chevron, to exit Myanmar.Footnote9 While it is easy to dismiss petitions and calls for actions as window dressing, they do, occasionally, create the desired influence. In January 2022, both Chevron and Total Energies announced that they were exiting Myanmar.Footnote10

These two processes hint at an aesthetic economy that potentially returns more to its creators and subjects than one might ordinarily expect. In its most basic form, the provision of hard cash is useful to a people suffering severe economic deprivation. And encouragement that the world is watching has the potential to feed a much-starved cause. It is not strictly necessary to refer to the vast resource mobilization literature to highlight the importance of material and motivational resources in mobilizing populations (McAdam et al., Citation1996). But as a form of, say, post-colonial resource mobilization, the art gallery plays an understudied role.

Conclusion

While the artists themselves, the networks that formed, and the modes of production and distribution of Myanmar’s transnational art differ from those of the arpilleras, Adams’ notion of solidarity art remains exceptionally relevant for examining transnational art activism. This is because, as this article demonstrates, art and payment for that art is not the only thing that crosses borders. Information, moral support, and solidarity itself travels transnationally.

In this paper, I have examined a new form of solidarity art, wherein art produced by artists from Myanmar was transmitted electronically and reprinted, to be shown in spaces of the Global North, expanding the audience base but potentially muddying the message. Not naïve about the ways that well-meaning practices can still reflect the deep historical colonial dynamics in which they are embedded, I set out to examine the potential for transnational resistance art to overcome the perils of the Global North/Global South divide. I identified three characteristics of solidarity art in Myanmar, which, taken together, attend to some of the problems present in the Global North/Global South imbalance and also serve as useful criteria for further conceptualizations of balanced transnational action.

First, Myanmar’s solidary art encompasses multiple transnationalisms – of themes, actors, and messages – that allow multiple publics to envision myriad responses to the subjects of the art. Second, Myanmar’s solidarity art – like the solidarity art in a previous era – is characterized by collective self-representation, in which the art is produced not only for those suffering harms, but by those affected. These two elements, which offer both the potential and peril of resistance art, are made more palatable by the third characteristic that solidarity art possesses: resource reciprocity, in which the funds generated by the artworks in the Global North are re-infused into the affected communities. While resource reciprocity is not new, the speed and ease of transferring funds enhances the possibility of empowering artists quickly.

An analysis of the artworks in the travelling Fighting Fear exhibit demonstrates that the artwork mobilizes multiple transnational elements, showcases representations of Myanmar subjects by those from Myanmar, and returns resources to the Myanmar community. While not the subject of this article, I also assert that these artworks stand on their own as art qua art, not only as instrumental advocacy fodder. The artworks are sophisticated and timely, offering nuanced messages about Myanmar and the international actors that have been part of the reason that Myanmar finds itself in its current situation of chaos. They require a thinking and rethinking of the status quo, disrupting our assumptions about the role of artists and activists alike.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Alison Francis, (PhD candidate, University of Sydney), who offered important contributions to several sections in this article. Elliot Prasse-Freeman is also to be thanked for careful and insightful suggestions throughout. Three excellent anonymous reviewers significantly improved the content of this article. I am grateful to all of them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Susan Banki

Susan Banki is the Chair of Sociology and Criminology at the University of Sydney and the Director of its Master of Social Justice programme. Her research interests lie in the political, institutional, and legal contexts that explain the roots of and solutions to international human rights violations. In particular, she is interested in the ways that questions of sovereignty, citizenship/membership and humanitarian principles have shaped our understanding of and reactions to various transnational phenomena, such as the international human rights regime, international migration and the provision of international aid. Susan's focus is in the Asia-Pacific region, where she has conducted extensive field research in Thailand, Nepal, Bangladesh and Japan on refugee/migrant protection, statelessness and border control. She has authored or co-authored more than 20 peer-reviewed publications and is currently writing a manuscript on the ecosystem of exile politics.

Notes

2 The entirety of the Fighting Fear exhibit can be accessed through an online version of the catalogue produced by 16Albermarle, the gallery in Sydney that showcased the exhibit, at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d566a1b3286c70001282e7a/t/6095f6aa8f02b11d5e376db8/1620440771743/Ex%237MyanmarCatalogue_7May21-compressed.pdf (accessed 23 January 2022).

3 Transnationalism also offers the means for transnational repression. See Moss, Citation2016.

4 The example of Aye Min Thant comes to mind, an expatriate Myanmar journalist who was lambasted for critiquing the People’s Defense Force by those inside the country. See, for example, https://twitter.com/the_ayeminthant/status/1407524578289668096?lang=en (accessed 5 March 2022). It was lost neither on Aye Min Thant nor on their detractors that Aye Min Thant themself has excoriated journalists from the Global North who have swooped into Myanmar with a saviour complex (Aye Min, Citation2021).

5 It is not only artists who engage in spatial testimony. Herscher writes powerfully about US Secretary of State Colin Powell’s use of aerial photography, replete with dates, captions, and explanations, to lay bare the abuses of Saddam Hussein’s regime to the United Nations Security Council (Citation2014). Herscher exposes the ways in which this type of surveillance – possible because of structural technological asymmetries – creates fraught relationships between the surveillor, the surveilled, and the public that seeks to absorb the testimony.

6 The pseudonym 882021 represents the merging of two of the most significant years of democracy protests in Myanmar: 1988 and 2021. Lee is the transliteration of the word လီး which is typically understood in on-line memedom to mean ‘penis’. I thank Elliot Prasse-Freeman for this observation.

7 Article in French, author’s translation: https://www.france24.com/fr/asie-pacifique/20210918-l-artiste-birman-bart-was-not-here-en-r%C3%A9sistance-contre-la-junte-militaire

8 https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d566a1b3286c70001282e7a/t/60da74128829b90f5cce7788/1624929298709/Melinda±Tu.pdf (accessed 15 February 2022).

9 https://www.hrw.org/fr/news/2021/07/31/myanmar-le-coup-detat-engendre-des-crimes-contre-lhumanite (accessed 15 February 2022).

10 https://www.hrw.org/fr/news/2022/01/20/myanmar-totalenergies-soutient-des-sanctions-ciblees (accessed 15 February 2022).

References

- Adams, J. (2005). When art loses its sting: The evolution of protest art in authoritarian contexts. Sociological Perspectives, 48(4), 531–558. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2005.48.4.531

- Adams, J. (2013). Art against dictatorship: Making and exporting arpilleras under Pinochet. University of Texas Press.

- Adams, J. (2018). What is solidarity art? In J. Stites-Mor & M. D. C. S. Posas (Eds.), The Art of solidarity: Visual poetics of empathy. University of Texas Press.

- ArtForum. (2021, February 17). Myanmar Artists Protest Military Coup. ArtForum. https://www.artforum.com/news/myanmar-artists-protest-military-coup-85093

- Atkins, S., & Eberhart, H. (2014). Presence and process in expressive arts work: At the edge of wonder. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Aye Min, T. (2021, April 13). “Every Journalist’s Worst Nightmare”: CNN’s Myanmar Misadventure. New Naratif. https://newnaratif.com/every-journalists-worst-nightmare-cnns-myanmar-misadventure/

- Banki, S. (2022). The Co-construction of the Myanmar diaspora in Australia. In M. Phillips & L. Olliff (Eds.), Understanding diaspora development: Lessons from Australia and the pacific (pp. 37–58). Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Banki, S., & Schonell, R. (2018). Voluntourism and the contract corrective. Third World Quarterly, 39(8), 1475–1490. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1357113

- Beech, H. (2021, February 17). Paint, poems and protest anthems: Myanmar’s coup inspires the art of defiance. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/17/world/asia/myanmar-coup-protest-art.html

- Betts, A., & Jones, W. (2016). Mobilising the diaspora: How refugees challenge authoritarianism. Cambridge University Press.

- Braden, L. E. (2021). Networks created within exhibition: The curators’ effect on historical recognition. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218800145

- Brooten, L. (2004). Human rights discourse and the development of democracy in a multi-ethnic state. Asian Journal of Communication, 14(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/0129298052000343958

- Byrne, J. (2021, May 24). “I’ll lay down my life for you all”: Poetry and activism on the streets of Myanmar. World Literature Today. https://www.worldliteraturetoday.org/blog/essay/ill-lay-down-my-life-you-all-poetry-and-activism-streets-myanmar-james-byrne

- Cabot, C. (2021, September 18). L'artiste birman Bart Was Not Here en résistance contre la junte militaire. France 24. https://www.france24.com/fr/asie-pacifique/20210918-l-artiste-birman-bart-was-not-here-en-r%C3%A9sistance-contre-la-junte-militaire

- Carlson, M. (2016). Painting as cipher: Censorship of the visual arts in post-1988 Myanmar. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 31(1), 145–172. https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/apps/doc/A452374552/AONE?u = usyd&sid = bookmark-AONE&xid = 6c183b26 https://doi.org/10.1353/soj.2016.0001

- Cascone, S. (2021, February 16). After a military coup, artists across Myanmar are making protest art to share their struggle for democracy with the world. ArtNet. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/myanmar-artists-protest-coup-1943543

- Cheesman, N. (2021). Revolution in Myanmar. Arena, (8), 60–65.

- Chouliaraki, L. (2013). The ironic spectator: Solidarity in the age of post-humanitarianism. John Wiley & Sons.

- Condee, W. (2011). Three bodies, one soul: Tradition and Burmese puppetry. Studies in Theatre and Performance, 31(3), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1386/stp.31.3.259_1

- Coyer, C. (2021, March 10). Art for freedom: Artists at Frontline of Myanmar’s protests,’ Untitled Magazine. Untitled Magazine. https://untitled-magazine.com/art-for-freedom-artists-at-front-lines-of-myanmar-protests/

- d’Evie, F. (2014). Dispersed truths and displaced memories: Extraterritorial witnessing and memorializing by diaspora through public Art. In P. D. Rush & O. Simić (Eds.), The arts of transitional justice (pp. 63–79). Springer.

- De Waal, A. (2010). The humanitarians’ tragedy: Escapable and inescapable cruelties. Disasters, 34, S130–S137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01149.x

- Dirgantoro, W. (2020). From silence to speech: Witnessing and trauma of the anti-communist mass killings in Indonesian contemporary art. World Art, 10(2-3), 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/21500894.2020.1812113

- Dobson, K., & McGlynn, Á. (2013). Transnationalism, activism, art. University of Toronto Press.

- Duffield, M. (2001). Global governance and the new wars: The merging of development and security. Zed Books.

- Duncan, K. (2021, May 10). The portrait artists honouring Myanmar’s imprisoned and murdered. Southeast Asia Globe. https://southeastasiaglobe.com/protest-art-myanmar/

- Emery, J. (2021, April 12). Tatmadaw coup D’État As The Ramayana – Analysis Eurasia Review News and Analysis. https://www.eurasiareview.com/12042021-tatmadaw-coup-detat-as-the-ramayana-analysis/

- Fine, G. A. (1996). Reputational entrepreneurs and the memory of incompetence: Melting supporters, partisan warriors, and images of President Harding. American Journal of Sociology, 101(5), 1159–1193. https://doi.org/10.1086/230820

- Guerin, F., & Hallas, R. (2007). The image and the witness: Trauma, memory and visual culture. Wallflower Press.

- Hagan, M. (2010). The human rights repertoire: Its strategic logic, expectations and tactics. The International Journal of Human Rights, 14(4), 559–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642980802704312

- Hayes, S. (2021, February 12). Myanmar's creatives are fighting military rule with art—despite the threat of a Draconian new cyber-security law. Time. https://time.com/5938674/myanmar-protest-digital-crackdown/

- Herscher, A. (2014). Surveillant witnessing: Satellite imagery and the visual politics of human rights. Public Culture, 26(3), 469–500. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2683639

- Holliday, I., & Myat, A. K. (2021). Painting Myanmar's transition. Hong Kong University Press.

- Hong, M. S., & Chun, Y. J. (2021). Symbolic habitus and new aspirations of higher education elites in transitional Myanmar. Asia Pacific Education Review, 22(1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-020-09649-7

- Htet, S. H. L., Ko, A., & Satt, M. (2021, February 17). Beaten pots, three finger salutes and car horns: The Art of protest in Myanmar. Art Review, https://artreview.com/beaten-pots-three-finger-salutes-and-car-horns-the-art-of-protest-in-myanmar/

- Jeffery, R. (2021). The role of the arts in Cambodia’s transitional justice process. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 34(3), 335–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-020-09361-9

- Jensen, M., & Jolly, M., (Eds) (2014). We shall bear witness: Life narratives and human rights. The University of Wisconsin Press.

- Johnson, H. L. (2011). Click to donate: Visual images, constructing victims and imagining the female refugee. Third World Quarterly, 32(6), 1015–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.586235

- Johnston, N. (2021, February 19). The artists fighting for a different future in Myanmar. Frieze. https://www.frieze.com/article/artists-protest-myanmar-coup-2021

- Jones, L. (2014). Explaining Myanmar's regime transition: The periphery is central. Democratization, 21(5), 780–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.863878

- Keck, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. Cornell University Press.

- Keysar, H. (2019). A spatial testimony: The politics of do-it-yourself aerial photography in east Jerusalem. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(3), 523–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818820326

- Knill, P. J., Levine, E. G., & Levine, S. K. (2005). Principles and practice of expressive arts therapy: Toward a therapeutic aesthetics. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Koinova, M. (2018). Critical junctures and transformative events in diaspora mobilisation for Kosovo and Palestinian statehood. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(8), 1289–1308. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1354158

- Koinova, M. (2021). Diaspora entrepreneurs and contested states. Oxford University Press.

- Kurze, A. (2019). Youth Activism, Art, And Transitional Justice: Emerging spaces of memory after the jasmine revolution. In A. Kurze & C. K. Lamont (Eds.), New critical spaces in transitional justice (pp. 63–86). Indiana University Press.

- Kyaw, T. R., Chin, S., Art, B., Sadain, A. Z., Hlaing, K., & Ali, M. (Eds) (2021, March 22). Artists respond: Myanmar fights for democracy. New Naratif. https://newnaratif.com/comics/ar-myanmar-fights-for-democracy/

- Lederach, J. P. (2005). The moral imagination: The art and soul of building peace. Oxford University Press.

- Levine, E. G., & Levine, S. K. (Eds) (2011). Art in action: Expressive arts therapy and social change. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Levitt, P. (2009). Roots and routes: Understanding the lives of the second generation transnationally. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35(7), 1225–1242. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830903006309

- Lobo, M. (2021). Living on the edge: Precarity and freedom in Darwin, Australia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(20), 4615–4630. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732585

- Maddox, M. (1993). Ethics and rhetoric of the starving child. Social Semiotics, 3(1), 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350339309384410

- McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D., & Zald, M. N. (1996). Introduction: Opportunities, mobilizing structures, and framing processes - toward a synthetic, comparative perspective on social movements. In D. McAdam, J. D. McCarthy, & M. N. Zald (Eds.), Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings (pp. 1–20). Cambridge University Press.

- McLagan, M. (2006). Introduction: Making human rights claims public. American Anthropologist, 108(1), 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.191

- McLeod, L., Dimitrijević, J., & Rakočević, B. (2014). Artistic activism, public debate and temporal complexities: Fighting for transitional justice in Serbia. In P. D. Rush & O. Simić (Eds.), The arts of transitional justice (pp. 25–42). Springer.

- McQuiston, L. (2019). Protest! A history of social and political protest graphics. Princeton University Press.

- Moss, D. M. (2016). Transnational repression, diaspora mobilization, and the case of the Arab Spring. Social Problems, 63(4), 480–498. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spw019

- Movius, L. (2021, 1 March). The artists on the frontline of Myanmar’s deadly protests. The Art Newspaper.

- Oo, P. P. (2021, February 11). The importance of Myanmar’s Pots and Pans Protests The Lowy Interpreter. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/importance-myanmar-s-pots-and-pans-protests

- Opondo, S. O., & Shapiro, M. J. (2019). Subalterns ‘speak’: Migrant bodies, and the performativity of the arts. Globalizations, 16(4), 575–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1473373

- Prasse-Freeman, E. (2012). Power, civil society, and an inchoate politics of the daily in Burma/Myanmar. The Journal of Asian Studies, 71(2), 371–397. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911812000083

- Prasse-Freeman, E. (2014). Fostering an objectionable Burma discourse. Journal of Burma Studies, 18(1), 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1353/jbs.2014.0010

- Prasse-Freeman, E. (2022). Resistance/refusal: Politics of manoeuvre under diffuse regimes of governmentality. Anthropological Theory, 22(1), 102–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499620940218

- Pussetti, C. (2013). Woundscapes’: Suffering, creativity and bare life–practices and processes of an ethnography-based art exhibition. Critical Arts, 27(5), 569–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2013.855522

- Pyae. (2021, June 19). Recharging for the revolution: self-care in post-coup Myanmar raise three fingers. https://www.threefingers.org/blog-post/recharging-for-the-revolution-self-care-in-post-coup-myanmar

- Quinsaat, S. M. (2019). Transnational contention, domestic integration: Assimilating into the Hostland polity through homeland activism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(3), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1457433

- Ra, D., & Ju, K. K. (2021). ‘Nothing about us, without us’: Reflections on the challenges of building land in our hands, a national land network in Myanmar/Burma. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 48(3), 497–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1867847

- Robertson, K. (2011). Capitalist cocktails and Moscow mules: The Art world and alter-globalization protest. Globalizations, 8(4), 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2011.585849

- Sadan, M. (2014). The historical visual economy of photography in Burma. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde/Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 170(2-3), 281–312.

- Schlund-Vials, C. J. (2017). Art, activism, and agitation: Anida Yoeu Ali. Verge: Studies in Global Asias, 3(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.5749/vergstudglobasia.3.1.0054

- Schuck, R. I., Gorsevski, E. W., & Lin, C. (2013). On body snatching: How the rhetoric of globalization elides cultural difference in ‘bodies … The exhibition’. Globalizations, 10(4), 603–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2013.806738

- Shapiro, M. J. (2015). Insurrectional arts: Restoring a politics and ethics of attention. Globalizations, 12(6), 886–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2015.1100868

- Skidmore, M. (2005). Burma at the turn of the twenty-first century. University of Hawaii Press Honolulu.

- Smith, E. (2021, April 12). In Myanmar, Protests Harness Creativity and Humor. Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/637088/myanmar-protests-harness-creativity-and-humor/

- Sontag, S. (1979/2001). On photography. Macmillan.

- Strassler, K. (2020). Demanding images: Democracy, mediation, and the image-event in Indonesia. Duke University Press.

- Szörényi, A. (2006). The images speak for themselves? Reading refugee coffee-table books. Visual Studies, 21(01), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860600613188

- Tan, Y. (2021, February 7). Myanmar coup: How citizens are protesting through art. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55930799

- Tarrow, S. (2005). The New transnational activism. Cambridge University Press.

- Williams, D. C. (2012). Changing Burma from without: Political activism Among the Burmese diaspora. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 19(1), 121–142. https://doi.org/10.2979/indjglolegstu.19.1.121

- Win, T. L. (2021, February 19). Young, creative and angry: Myanmar's youth pushes back. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Life-Arts/Young-creative-and-angry-Myanmar-s-youth-pushes-back

- Woods, K. M. (2020). Smaller-scale land grabs and accumulation from below: Violence, coercion and consent in spatially uneven agrarian change in Shan state, Myanmar. World Development, 127, 104780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104780

- Yeung, J., & Lenette, C. (2018). Stranded at sea: Photographic representations of the Rohingya in the 2015 Bay of Bengal crisis. The Qualitative Report, 23(6), 1301–1313.

- Young, S. (2021). Citizens of photography: Visual activism, social media and rhetoric of collective action in Cambodia. South East Asia Research, 29(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967828X.2021.1885305