ABSTRACT

In the context of the revitalized scholarly interest in small and middle powers, we employ a relational network approach to study the role of non-major powers as bridges and hubs. Contrary to prominent conceptions that centre on preconceived country groupings or states’ variable attributes, such as the size of their territory, economy, or armed forces, our study foregrounds the influence that states gain from their position in international networks. We begin by developing an ideal-typical theory of bridges and hubs. We then employ these concepts to discuss empirical examples, examining the extent to which our cases embody these ideal types. Our approach sheds light on the rationale for geostrategic relocation and how states can use networks to gain influence in world politics.

1. Introduction

The international order is going through a unique form of flux. Patterns of production, investment, and trade have shifted, first and foremost because of China’s dramatic ascendancy, but also because of the ancillary rise of major countries among the ‘rest’ in the international system. At the same time, the discourse and policy of Western ‘core’ countries have raised doubts about their commitment to open multilateral cooperation that has long provided ‘peripheral’ states with opportunities to partake in global governance.Footnote1

With respect to both anticipation and response to these challenges, countries beyond those at the top tier of the global hierarchy have persistently albeit unevenly tried to adjust and find new roles. The search for a new role has been a common theme among these countries since the end of the Cold War ‘unfroze’ the rigid alliance structure. In recent years, however, the tendency of geostrategic relocation has gathered momentum, leading to the emergence of new roles for secondary states that call into question the dichotomous distinction between vulnerable ‘small states’ and activist ‘middle powers’ (Long, Citation2022; Sharman, Citation2017; Thorhallsson, Citation2018; Cooper & Shaw, Citation2009).

We argue that relational thinking is helpful for understanding how secondary states relate to the international system and the conditions under which they gain influence in global politics. Relationalism refers to a family of theories that foreground actors’ embeddedness in webs of social relations (Abbott, Citation2016; Emirbayer, Citation1997). Applied to world politics, it suggests that who the actors are and what roles they can play internationally is not determined by their unit-level attributes – such as the size of a country’s territory or the level of economic development—but derives from the structure and content of their ties with others (Jackson & Nexon, Citation1999; Citation2019; McCourt, Citation2016; Duque, Citation2018; Qin, Citation2018). A relational perspective challenges the prevailing view that understands influence in international politics primarily as a function of states’ material resources, shifting the focus to states’ ‘social power’ that derives from their position in networks of relations (Goddard, Citation2018; Hafner-Burton et al., Citation2009).

We apply a relational network approach to the common geostrategic notions of ‘bridges’ and ‘hubs.’ While an increasing number of states draw on these metaphors, these concepts have received little scholarly attention. We argue that this neglect represents a major gap as ‘bridges’ and ‘hubs’ represent examples of a larger family of emergent role conceptions that reflect states’ aspirations to acquire influence even in a global environment in which they appear to be structurally disadvantaged.Footnote2

In a first step, we introduce relationalism as an analytical perspective to understand secondary states’ attempts to carve out a place in the international order. Building on a relational network approach, we then develop the ideal-typical constructs of ‘bridges’ and ‘hubs.’ Bridges, from this perspective, are countries that gain influence by connecting otherwise disconnected groups of states. Bridges often exalt their ‘cusp’ position between world regions. In this sense, they are typically geographically specific. By contrast, hubs seek to attain importance by transcending their local or regional contexts, gaining influence by establishing an unusually high number of global connections.

In a second step, we employ these concepts to discuss empirical examples of bridges and hubs. We consider the cluster of MIKTA states—Mexico, Turkey, and South Korea—as examples of bridges. We contrast this group with the examples of Panama, Qatar, and Singapore, three countries that are often discussed as global hubs. We examine the extent to which these cases comply with the ideal-typical conceptions of bridges and hubs, how the international community has responded to their claims to place and position, and explore whether their relocation has paid off in terms of social power. Although both groups of states have benefitted from a policy of geostrategic relocation, our analysis shows tensions between ascribed and attained positions; it also highlights that ‘locational vulnerabilities’ need to be factored in when discussing the position of bridges and hubs (Cooper, Citation2018).

2. Approaching bridges and hubs from a relational network perspective

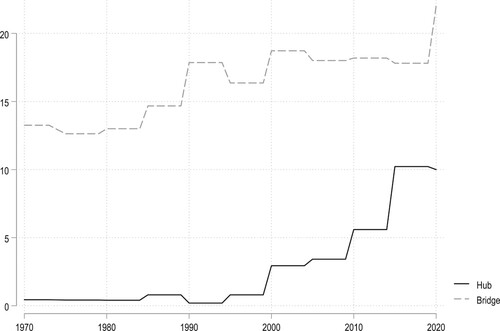

As metaphors, bridges and hubs have become increasingly common in world politics over the past decades. Although it is difficult to capture the true number of countries that now seek to position themselves as either bridges or hubs, the growing attraction of these geostrategic images is evident in the number of UN General Assembly speeches that mention these terms (). The hub notion, in particular, has experienced a marked uptick. In more recent years, approximately 5% of countries mentioned the term in their annual address.

Figure 1. Five-year average of UNGA speeches that mention ‘bridge’ or ‘hub’ at least once. Word frequency analysis based on Baturo et al.'s (Citation2017) corpus of UN General Assembly speeches between 1970–2020 (N = 8,471). Only nouns are considered as a more conservative approach to detecting the use of either metaphor.

Relationalism provides a fruitful approach to understanding the appeal of these images and the conditions under which they provide secondary states with influence. Relational theories argue that agents develop their properties not in isolation but as the result of the ties they maintain with others. This is in contrast to substantialist approaches, which assume that agents possess certain inherent and fixed properties that are prior to and independent from their interactions with others (Abbott, Citation2016; Emirbayer, Citation1997). A common substantialist view in IR research holds that the power of states derives from their relative weight in the international system—especially the size of their territory, economy and armed forces. Structural realists, for example, consider the distribution of material capabilities among states to be the determining factor in international politics. As a consequence, non-great powers have little political importance and can be safely ignored in parsimonious analysis (Waltz, Citation1979, p. 72; for a discussion, see Sharman, Citation2017; Long, Citation2022, pp. 17–21). The substantialism that underpins IR theories, such as structural realism, renders them poorly equipped to account for the opportunities that the international system provides to secondary states.

Relational thinking allows analysts to steer clear of some of the controversies surrounding ‘middle powers’ and ‘small states.’ Debates on either category suffer from substantialism, defining middle powers and small states either in terms of other variable attributes such as material powers, or they discuss them in terms of preconceived country groupings. For example, although the middle power category has been extended beyond Australia and Canada, there is little consensus on whether the concept can be meaningfully applied to other states that are not liberal democracies (Cooper, Citation2018; Jordaan, Citation2017). Small statehood is commonly associated with an activist or ‘entrepreneurial’ foreign policy, but here, too, no consensus exists of what ultimately defines a small state (Cooper, Citation1997; Ingebritsen, Citation2006; Ravenhill, Citation2018). In response, Panke (Citation2012) and Long (Citation2017b) have argued for a move away from debates over the relative size of these actors, towards greater attention to the relationships they seek and maintain. Our approach advances the conversation in this direction.

Relational approaches posit that states, their properties, and the role they play internationally are the result of ongoing processes and cannot be properly understood in isolation from one another (Jackson & Nexon, Citation1999; Citation2019; McCourt, Citation2016; Qin, Citation2018). Relationalism emphasizes that agents’ attributes are emergent properties that depend on networks of relations. These relationships vary in content and form: they can involve material and immaterial transactions,Footnote3 and they differ in terms of their strength or intensity (Granovetter, Citation1973). This also means that relationships are never devoid of intersubjective meaning. To paraphrase Erikson (Citation2013:, p. 227), the meaning that an actor assigns to another is the basis of any relationship; ‘in fact,’ she adds, ‘the absence of meaning could easily be understood as the absence of a relationship’ (see also Goddard, Citation2018; Tilly, Citation1998).

Relationalism suggests that actors’ roles are conditioned by the structure of the network and their place therein (Borgatti & Everett, Citation1992; Hafner-Burton et al., Citation2009). Although earlier discussions treated networks as open and relatively egalitarian structures (see Heine, Citation2013; Slaughter, Citation1997), network analysis has extensively documented that complex networks tend to be hierarchical, with few ‘nodes’ exercising disproportionate control over the rest of the network (Barabási & Albert, Citation1999). As Farrell and Newman (Citation2019) note, rather than ushering in an open and egalitarian international order, networks distribute power and vulnerabilities unevenly.

Hafner-Burton et al. (Citation2009, pp. 570–572) propose a distinction between ‘access’ and ‘leverage’ as two sources of ‘social power’: the influence that actors gain from their positionality. Access depends on the overall centrality of an actor, defined by an unusually large number of connections; leverage stems from exclusive ties with marginal actors or otherwise weakly connected nodes. Centrally-located actors, for example, can access material and ideational resources more easily than peripheral actors. States with vast material resources often occupy central positions in international networks, as captured by the idea that imperial systems tend to exhibit ‘hub-and-spokes’ structures (Nexon & Wright, Citation2007; see also MacDonald, Citation2018, p. 142). But great powers are not automatically central actors, nor are they necessarily the only central actors in international affairs. Consider, for example, the role of ‘brokers.’ The influence of brokers stems from their structurally advantageous position as sites that connect otherwise disconnected groups of actors (Burt, Citation1992). According to Granovetter (Citation1973) the ‘strength of weak ties’ lies in their ability to act as conduits between diverse and often disparate social groups.Footnote4 Because brokers control resources and information flows between loosely integrated (but often internally cohesive) communities, they can act as innovators or gatekeepers. IR approaches draw on these insights to explain how seemingly marginal actors can introduce new norms (Goddard, Citation2009), leverage their position to prevent issues from emerging on the policy agenda (Carpenter, Citation2011), or gain international status (Baxter et al., Citation2018).Footnote5

Importantly, neither a network’s structure nor actors’ positions therein are fixed. As a result, actors can strategically seek out positions that empower them. However, because a network necessarily consists of other actors and the ties that connect them, the opportunities that networks create are constrained by the preferences and actions of others. As Goddard (Citation2018) elaborates, the creation of ties is a ‘two-way street’ that depends on interlocutors’ willingness to invest in relationships; and while states may have some control over their immediate ties, ‘they cannot determine or even anticipate the systemic evolution of their network position’ (Goddard, Citation2018, p. 768, emphasis in original).Footnote6 Network analysis suggest that actors can occupy influential positions without necessarily being aware of their own centrality (see Padgett & Christopher, Citation1993). The systemic effects of networks, and the understanding that actors have of them, is not only dependent on the meaning that actors attach to their direct ties with others; it also depends on the connections of their connections, andsoforth. Thus, actors only have so much control over their position within a network.

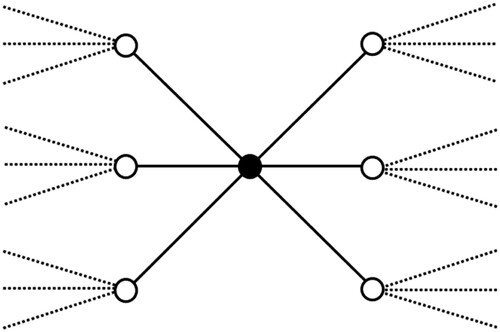

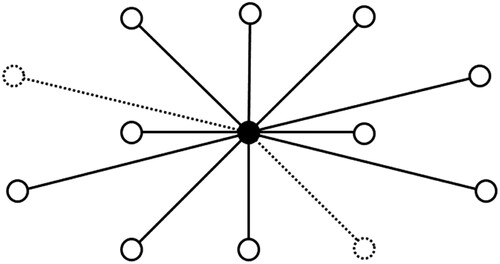

2.1. Bridges

We build on relational network thinking to examine the role that bridges and hubs (can) play on the international stage. Bridge countries, in this view, gain social power by leveraging their in-between position. Viewed in strictly structural terms, bridges are similar to brokers in that they occupy intermediary positions, connecting otherwise disconnected communities (see ). Moving beyond this minimal definition, however, we note two important conceptual differences. First, although bridges can connect different types of communities, they tend to be geographically situated, typically located between two or more world regions. As Deutschmann (Citation2022) explains, human networks often coalesce into regional clusters, emphasizing the continuing importance of geography in a globalized and increasingly interconnected world.Footnote7As a result, we expect bridge roles to be commonly found in ‘cusp’ countries that lie somewhat uneasily between communities, such as regions or regional organizations (Herzog & Robins, Citation2014).Footnote8 However, states do not automatically become bridges by virtue of their geographic location: whether they effectively occupy this role depends on their policies and the ties they create.

Second and related, although both brokers and bridges gain influence through the ‘power of weak ties,’ the position of bridge countries creates ambiguities that brokers can easily avoid. By definition, bridge countries are outsiders or liminal members of regional configurations, which can create tensions as bridges have to deal with different and at times conflicting interests and identities. Turkey’s relationship with the EU and NATO, for example, is often viewed in this fashion (Kaya, Citation2020).

2.2. Hubs

Hubs are centrally-located sites defined by their unusually large number of connections (see ). Where bridges serve to connect different geographical regions, hubs thrive in their adaptability and versatility to situate themselves as central actors. Geographic attributes, such as the physical location of a coastline and the ability to serve as a shipping hub, may help the creation of this role, but are not required to be a hub.

Hubs can serve a variety of functions. Some countries serve as diplomatic hubs, hosting headquarters for key international organizations, such as the United Nations. Others may serve a transportation hubs, connecting the world through infrastructural nodal points, such as major air or sea ports. Other hubs play a central role in the provision of international services, including trade, finance, and technology. Yet another type of hub emerges in context of culture and sports, including through museum, art fairs and exhibitions, or the hosting of major sports events such as the Formula 1 Grand Prix races (see, for example, Lee, Citation2021; Lekakis, Citation2021).Footnote9 All hubs, though, share the same relational attributes in that they establish or seek to establish an unusually large number of connections.

3. Case studies

We argue that a relational network perspective that focuses on actors’ relationships rather than variable attributes provides important insights into the rationale and effects of secondary states’ geostrategic relocation. We first discuss the case of non-traditional middle powers that form part of the MIKTA grouping, including Mexico, Turkey, and South Korea. MIKTA is an informal alliance explicitly created to ‘bridge divides’ and ‘build consensus on issues which would be relevant to all regions’ (MIKTA, Citationn.d.). Because we conceive bridges and hubs as ideal types, we do not expect empirical cases to perfectly embody these concepts. However, we do expect MIKTA countries to exhibit at least some of the characteristics of bridges, as discussed above. The same applies to our discussion of hubs, which focuses on the case of Panama, Singapore and Qatar, which should occupy central positions as a result of their unusually large number of ties with others. In keeping with our relational network approach, we discuss states’ positions in diplomatic and commercial networks, and the meaning that states attach to their relations with others.

3.1. Bridges

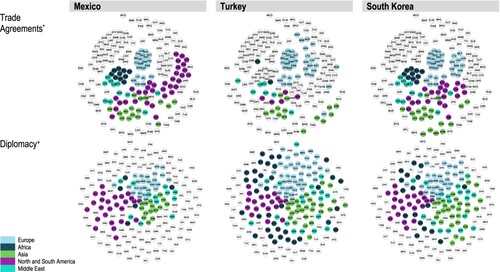

We define bridges as countries that connect otherwise disconnected communities. shows the ego-centric networks for Mexico, Turkey, and South Korea. Ego-centric networks show subsets of larger networks, focusing on the connections of individual nodes. All graphs below are created with the network analysis package Gephi. They use the Fruchterman-Reingold layout algorithm, which plots networks based on the strength of ties (better-connected nodes are placed more centrally, less connected nodes occupy peripheral positions; closely connected communities form clusters). The first network is based on the DESTA database (version 2.0), containing information on 690 preferential trade agreements in force by Nov 2020 (Dür et al., Citation2014). The second, showing countries’ position in the network of diplomatic missions, builds on the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index (2021), which we supplemented with information from the Qatari and Panamanian ministries of foreign affairs. Both networks are weighted, which means that they treat the repetition of ties as a measure of the strength of connections.Footnote10 In addition, the diplomatic network is directed, distinguishing between outgoing and ingoing ties. The regional classification follows the Correlates of War (CoW) geocode scheme.Footnote11

Figure 4. Ego-centric networks (bridges). *Undirected, weighted network based on DESTA 2.0 (Dür et al., Citation2014); +directed, weighted network based on the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index and complemented with information from the Qatari and Panamanian ministries of foreign affairs.

Beginning with Mexico, it is noteworthy that the country has historically labelled itself as a bridge (Chagas-Bastos & Franzoni, Citation2019; Pellicer, Citation2006). During the Cold War, it exalted its role as a bridge that would foster dialogue between the two contending ideological blocs; after 1990, various Mexican governments employed bridge metaphor to highlight the countries’ intermediary position between Latin America and the United States.Footnote12 Mexico is not only a member of the MIKTA initiative, it also played a key role in the creation of regional blocs in the Americas. Mexico was instrumental in the founding of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), a regional bloc aimed at political coordination and the representation of regional interests vis-à-vis external actors, most notably the United States, but also China and the European Union. Mexico was also a founding member of the Pacific Alliance, initially devised by right-wing governments in Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru to serve as a ‘platform’ or ‘bridge’ to connect Latin American economies with Asian markets (Schulz & Rojas-De-Galarreta, Citation2022).

Yet, as shows, Mexico’s bridge role is not immediately clear from its position in the network of free trade agreements. While the country is connected to a large number of states in North and South America, it also maintains links to many countries from other world regions. Overall, these links do not suggest that it occupies a priviledged intermediary position. The picture is clearer with regard to Mexico’s diplomatic missions. Much of the Mexican diplomatic presence focus on the Americas with further ties to particularly central countries in Europe and Asia.

Note also that the vast majority of Mexico’s Official Development Assistant (ODA) is destined to the Americas. Mexico’s international development cooperation reached USD 288 million in 2014, down from USD 396 million in 2013 (OECD, Citation2018). Mexico’s priority partner countries are those in Latin America and the Caribbean, with a concentration on Central America. With its experience in Mesoamerica behind it, Mexico has also taken other regional initiatives in the Caribbean and the Northern Triangle (OECD, Citation2018). This intense regional concentration limits its overall ability to serve as a diplomatic bridge despite its geographic position and longstanding tradition of diplomatic activism (Schiavon & Figueroa, Citation2019; Gómez Bruera, Citation2015).

This ambiguous picture is consistent with international perceptions of Mexico. While it may be connected to a host of countries through free trade agreements, its commercial relations with the United States through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, now USMCA) stand out, concentrating a staggering 85% of Mexican exports (78% go to the United States alone) (Workman, Citation2022a). In fact, its diplomatic presence largely reflects the outsized importance of the United States, where the number of consulates exceeds that of any other country by a wide margin.Footnote13

It is no surprise, then, that Mexico’s bridge role is externally contested. Brazil in particular disputes Mexico’s self-image as a natural ‘bridge’ between North and South, with some marked inclination and capacity for building connections within multilateral forums and creating links on a regional or cross-regional basis (Maihold, Citation2016). Rather than being depicted as a bridge, other Latin American countries view Mexico as inextricably bound to North America (Neto & Malamud, Citation2019); as a results, Latin Americans have shown ‘little enthusiasm’ towards Mexican regional leadership (Pellicer, Citation2006, p. 4; see also Cepik et al., Citation2021; Chagas-Bastos & Franzoni, Citation2019).

Mexico’s ‘social power’ is further curtailed by inconsistent messaging. Successive presidents have varied in their use of the bridge metaphor, often employing it in different ways. This was evident in the case of the lack of momentum on the Plan Puebla-Panama and the Mesoamerican Initiative designed to forge Mexican relations with its southern neighbours (Call, Citation2003). Tensions are also evident with regard to the Pacific Alliance. Although member states have established cooperation in a number of issue areas, such as student exchanges and consular representation, they also compete for attention from Asian partners, especially China. Further, under president Andrés Manuel López Obrador the arrangement has come under stress. All things considered, Mexico does not conform to the ideal-typical definition of a bridge, which explains why it has gained little social power despite its discourse.

Finally, not only does Mexico lack the connectivity associated with an ideal-typical bridge, it also lacks the intersubjective recognition of its peers. In other words, it is not enough for a state to declare itself a bridge; it must establish itself in an intermediary position and be acknowledged as such by its interlocutors.

Turkey appears to be a more convincing case of a bridge country. Since the 1970s, Turkish policymakers have explicitly emphasized their country’s unique position connecting the Middle East with Europe (Altunışık, Citation2014, p. 31; Bayer & Keyman, Citation2012). It is not surprising, then, that Turkey regularly employs this trope in its UNGA speeches. As Foreign Minister İsmail Cem noted in 2000, ‘[t]he rapidly globalizing world provides an appropriate environment for Turkey, at the heart of Eurasia, to serve as a bridge between many nations and civilizations’ (Baturo et al., Citation2017).

More recently, Turkey’s use of the bridge metaphor has evolved from an argument in favour of Turkey’s added value as a prospective member of the EU into a claim about its wider transregional importance. President Erdogan’s strategic shift reflects multi-relations and not privileged relationship with a single dominant power or bloc. This shift away from seeking closer ties with the EU is also reflected in its approach to global governance, more generally, as evidenced during its G20 presidency, during which it attempted to provide greater space for non-traditional middle powers (Parlar Dal, Citation2014). One obvious sign of this change is the erosion of its relationship with the EU, punctuated by the migration issue (İçduygu & Üstübici, Citation2014) which has resulted in greater securitization of Turkish relations with Syria (Kösebalaban, Citation2020) in an attempt to limit the spillover from current and future conflicts (Parlar Dal, Citation2016a). This is compounded by Turkey’s declining influence in the Middle East in the middle half of the 2010s (Parlar Dal, Citation2016b). As relationships with the EU and NATO ebb, relationships with Russia and China rise (Çelikpala, Citation2019). A push towards a Eurasian identity has gained momentum.

Turkey’s multiple institutional connections reinforce a ‘straddling’ profile. Turkey possesses ties in its extended neighbourhood, reflected in its membership in the Black Sea Economic Cooperation Business Council (BSEC), but also encompassing the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and Africa. Another example is Turkey’s participation in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), whose membership concentrates in North Africa, the Middle East, and Central and South East Asia (Deva, Citation2008). On some functional dimensions Turkey’s centrality is reinforced. Most notably, Turkish Airlines claims that it has the largest international flight network in the world.Footnote14

Turkey’s position in the network of commercial agreements suggests a similar intermediary role, connecting Europe with Asia and the Middle East. Particularly noteworthy, although not surprising, are Turkey’s connections with Central Asian countries located at the ‘outer rim’ of the graph that are geographically and culturally proximate to Turkey.Footnote15 In financial terms, the volume of Turkey’s trade clearly lags behind Mexico’s USD 225.3 billion and 31.25% of GDP. But, again, Turkey’s footprint is wider. Although 55% of Turkish exports are bound for Europe, this is not concentrated in a single country but spread across the entire region. Asian markets account for a further 25% (Workman, Citation2022b).

In diplomatic terms, our dataset shows that Turkey ranks fourth in the number of missions abroad (and sixth in the number of embassies, tied with Russia). Turkey has 36 embassies in Africa alone, and is present in many Central Asian countries. Turkey also has a wide number of missions in core Middle East/majority Islamic countries, including 2 in Saudi Arabia, 4 in Iran, 4 in Iraq, and 2 in the UAE. Thus, in addition to its geographic location, Turkey enjoys a unique cultural and diplomatic position (Babalı, Citation2009; Kalin, Citation2011; Shichor, Citation2009).

Turkey comes closer than Mexico to approximating the ideal type of a bridge. This is evident in ., especially in terms of diplomatic ties. Whereas Mexico’s diplomatic network is much more focused on the Americas (and Europe), Turkey has a wide-ranging network that covers these regions, in addition to Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Although Turkey has been unable to leverage its position to gain entry into the EU, it has nevertheless gained ‘social power’ from its transregional ties.

South Korea also exhibits many characteristics of a bridge. This role became particularly pronounced in the period after the global financial crisis, as the Korean government worked to act as a bridge between the old establishment and emerging powers within the G20, and to institutionalize the summits.Footnote16 But, as in Mexico, changes of government undermined this image.Footnote17

The symbolic importance of South Korea’s commitment to its role as a bridge is tied to its own experience with economic development, as a former aid recipient turned member of the OECD (Marx & Soares, Citation2013). Its position as an economic bridge is affirmed by the many private-sector links that place the country in a strategically advantageous position. Its corporate networks are global in scope; openness to foreign direct investment has grown in recent years, further expanding these economic ties.

This in turn has facilitated South Korea’s participation in IGOs, and in the negotiation of preferential trade agreements with a host of international actors. Various dimensions of soft power reinforce the network approach (Green, Citation2017).Footnote18

South Korea’s diplomatic relations facilitate the bridge between European nations and the rest of Asia. In particular, South Korea has the majority of its diplomatic missions in these two regions, with 38 missions to Europe as well as 54 to other Asian nations. Interestingly, given their relative size Australia and New Zealand host a combined 5 South Korean diplomatic missions: 3 in Australia and 2 in New Zealand. In this way, South Korea features prominently as a bridge between Europe and the Indo-Pacific. This dispersion of diplomatic relationships is consistent with South Korea’s business-focused expansion of diplomatic relations (Snyder, Citation2018) and also aligns with its focus on strong diplomatic ties to China and East Asia (Li, Citation2020).

In many ways, this soft network component is far more impressive than the traditional measures. While South Korea has made giant strides in trade, the divergence between the global reach of the core BRICS and its own more restricted profile is evident. Although the export figures are comparatively high (USD 644.4 billion or 39.5% of GDP), it is the regional focus that is most relevant. East Asia and Oceania account for 65.5% of South Korean trade, with only 17.8% destined to North America and 12.8% going to Europe (Workman, Citation2022c). Outside Asia, South Korea’s network of free trade agreements concentrates mostly on centrally located countries.

Spending $2 billion USD in 2016, South Korea is a major international aid donor. Its bilateral assistance is concentrated in Asia. Funding to this region encompassed 51% of ODA between 2013 and 2015. The largest recipient during this time was Vietnam, which received around 15% of bilateral ODA, predominantly as loans. Of South Korea’s 24 priority countries for ODA, 11 are in the Asia-Pacific region, 7 in sub-Saharan Africa, 4 in Latin America and 2 in Central Asia. The focus on Asia was reaffirmed by the 2017 International Cooperation Action Plan which allocates 57% of bilateral ODA to the Asia-Pacific region, 25 percent to sub-Saharan Africa and 11% to the Middle East/Central Asia (Donor Tracker, Citation2018).

South Korea’s economic development has transformed the country into an attractive international partner. However, the country’s ‘middle power’ diplomacy actively aided in the construction of ties that placed it in an advantageous position between North America and Europe, on the one hand, and Asian markets on the other. Perhaps more so than Mexico, which is closely tied to a single node (the United States), and more similar to Turkey, South Korea has gained prominence from occupying an intermediary role.

3.2. Hubs

Bridges and hubs acquire social power by occupying strategically advantageous positions. While bridges gain leverage from their intermediate location, hubs benefit from their vast number of connections. Whereas bridges are typically situated between different regional configurations, hubs attempt to overcome the limitations of their geography and relatively small size. While bridges tend to be territorial states, the hub metaphor applies to a much wider range of actors, including sovereign states, and global metropoles, and port cities.Footnote19

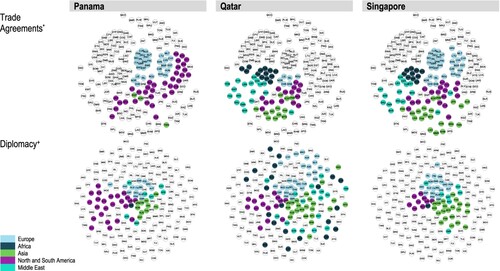

Our discussions centres on the cases of Panama, Qatar, and Singapore. These states are particularly entrepreneurial in their approach, often times inviting the world in through their activism in a specific functional domain. plots the ego-centric network of these countries. As before, we compare states’ ties in terms of free trade agreements and their diplomatic connections through resident missions (including consulates, consulates general, and embassies).

Figure 5. Ego-centric networks (hubs). *Undirected, weighted network based on DESTA 2.0 (Dür et al., Citation2014); +directed, weighted network based on the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index and complemented with information from the Qatari and Panamanian ministries of foreign affairs.

At first sight, Panama fits into this category due to the combination of physical infrastructure via the Canal, with a network of ports, bridges and power stations (Muñoz & Rivera, Citation2010). Panama also plays an important role in offshore banking and shipping services. As a result of its open ship registry, Panama boasts one of the world’s largest merchant fleets. Panama also has the benefit of a major airline, COPA, amplifying the role and connectivity of a hub not just for movement of goods, but also people. All of this is particularly noteworthy given Panama’s small population and otherwise unassuming location away from major powers.Footnote20 That said, Panama’s geographic location on the Central American Isthmus connecting North and South America has long been the focus of US interest, which exercised direct control over the Canal until 1999. Panama’s geostrategic value to the United States has also served as the justification for numerous US interventions.

In fact, inspecting Panama’s position in the commercial and diplomatic networks (), it appears that its position more closely resembles that of a bridge than a hub, as its networks concentrate heavily on the Americas and Europe. Comparing and , despite being a much smaller states that lacks the diplomatic tradition and resources of Mexico, Panama’s diplomatic footprint (measured in missions alone) is comparable. It is notewothy, for example, that Panama maintains only one mission in Africa (South Africa). What is not captured here, however, is the wider network of honorary consulates that Panama has established in port cities throughout the world, even though here, too, the emphasis lies on Europe and the Americas, in addition to Asia (Minsterio de Relaciones Exteriores, n.d.).

Reputationally, Panama, along with other countries such as Cyprus and Malta, has come under scrutiny for questionable practices, including global money laundering and tax evasion schemes. This raises an important question about the nature of hubs: must they be based on virtuous activities? While a perspective that centres on reputation and prestige would suggest that hubs gain influence from moral authority (Wohlforth et al., Citation2017; Schulz, Citation2019, p. 99), a relational network approach is not inherently normative. So long as other countries are connected to a hub and regard it as such, the virtuosity of transactions does not matter. Qatar and Singapore have also been subject to criticism, primarily for their human rights abuses (Human Rights Watch, Citation2022; see also Bishop & Cooper, Citation2018).

Similiar to Panama, Singapore and Qatar are central transport nodes. They are also major financial centres, with top-tier sovereign wealth funds; and both have become major airline transit points (Fan & Lingblad, Citation2016). Both also serve as significant sites for art and architecture, luxury goods, and high-tech forums and summits. Both Singapore and Qatar have persisted in their sustained commitment to this self-identification with an appreciable increase in networking capacity. In the case of Singapore, events such as the IISS Asia Security Summit: The Shangri-La Dialogue stands out (Lim, Citation2020). In Qatar’s case, Al Jazeera needs to be privileged as a foundational vehicle. Other mechanisms, though, include the Qatar Foundation, among others.

Diplomatically, both stand out for their convening capabilities whether on an ad hoc or a regularized basis. Signs and signals of recognition abound. Qatar in particular has worked towards a reputation as a mediator of conflict among other Middle Eastern countries that often lack direct diplomatic ties (Baxter et al., Citation2018).

Beyond these similarities, Singapore and Qatar function as very different kinds of hubs in our networks. In fact, they could be described as mirror images. shows Qatar does not occupy a hub position in the trade agreements network, as its relationships concentrate in a few world regions. This contrasts with its position in the diplomatic network, characterized by many dispersed connections across varying regions internationally. The opposite is true in the Singaporean case: the ASEAN country maintains relatively few and highly concentrated diplomatic connections, largely focused on Asia and particularly influential countries (such as Britain, China, or the United States). However, it clearly features as a hub in trade affairs where it has dispersed agreements internationally.

Because bridges are much more geographically embedded, they tend to face fewer competitors than hubs, which seek to transcend such confines. As hubs, both Singapore and Qatar have important regional competitors. Singapore for instance is often described as one of the strategic points of support, or as a critical transport transfer station (Yoshihara & Holmes, Citation2011). In doing so, other competitive sites are played up in comparative perspective, in keeping with the logic of accentuating the comparative advantage between Singapore and ‘mainland’ China. These competitors include not only Hong Kong – Singapore’s longstanding rival – but also cites such as Shenzhen, the twenty-first century maritime silk road’s development’s pioneer and main force (Fung, Citation2001). However, not unlike Mexico, the problem these sites face is their integration into the much larger Chinese market, which can overshadow other international relationships. Just as Singapore’s traditional rival is Hong Kong, Qatar’s rivals are Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, that also benefit from dynastic ties to other Gulf states.

In terms of competition, hubs are engage in a zero-sum game: as the number and significance of global hubs increases, the relative importance of each individual hub decreases. Part of what makes Singapore and Qatar successful as hubs is the fact that they are not in direct competition with one another. Each has carved out a distinctive niche that cannot easily be co-opted by the other.

4. Conclusion

This study has outlined a relational network approach to understanding the rationale and effects of secondary states’ geostrategic relocation. We argued that this take clarifies the conditions under which secondary states gain influence in global politics; it also frees the analysis from the conceptual and normative trappings of the middle and small power categories in IR. Singular labels, especially those privileging diplomatic statecraft, are not as useful in capturing projections of identities and interests in an international system in flux.

Our discussion centred on bridges and hubs as two common geostrategic concepts. Bridges, in our ideal-typical conception, act as geographically-located brokers that connect otherwise disconnected groups of states. We considered three empirical cases of bridges. However, of the MIKTA group analysed here, Turkey and South Korea comes closest to approximately the ideal type of a bridge. Whereas Turkey increasingly sees and positions itself as a central broker between Europe, Asian and the Middle East, South Korea acts as a conduit between Asia and Europe. By contrast, Mexico’s close integration with North America, both economically and diplomatically, undermine its position and ability to leverage its ties.

Whereas bridges gain social power from their in-between position, hubs depend on their unusually large number of connections. Both Singapore and Qatar has distinguished themselves as successful hubs, though in different domains. Panama, however, more closely resembles a bridge than a hub due to its geographic position between North and South America, and the pattern of its economic and diplomatic relationships.

The case of Panama raises the question of whether a bridge can also be a hub, and vice versa. For a bridge to serve as a hub, it must have network ties to a wide range of countries beyond its immediate neighbourhood. From the perspective of Panama’s formal economic and diplomatic ties, the Central American country clearly fails to meet this criterion as it lacks ties with countries outside Europe and the Americas. Conversely, for a hub to serve as a bridge, it must connect two distinctive communities that are not otherwise integrated. Thus, the success of a hub as a bridge is largely dependent on the existence of local competitors. This illustrates a central feature of networks, as states have limited control over the wider structure and roles played by other states.

The relational network lens overcomes many limitations of past debates. It avoids the association of middle powers with an attachment to the West, which gave rise to the question of whether non-Western countries can also be middle powers. At the same time, it avoids the substantialist trap of equating a country’s international position with its unit-level characteristics. Countries can overcome their structural conditions. Physical location is not destiny. The dynamism of the international order requires a more flexible approach that overcomes established and often binary conceptions, such as great powers and small states, the West and the rest, the Global North and the Global South, and so forth. The discussion of bridge and hubs contributes to the broader understanding of relationism in IR theory and the broader role that states play in defining their own position in the international hierarchy.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ names are listed alphabetically and both authors contributed equally to the article. We would like to thank the journal editors and reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Laura Levick for feedback, and Brandon Dickson and Hani El Masry for valuable research assistance. An earlier version was presented at the 2020 International Studies Association (ISA) Annual Meeting. Although we are appreciative of all this support the usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrew F. Cooper

Andrew F. Cooper is University Research Chair, Department of Political Science, and Professor, Balsillie School of International Affairs, University of Waterloo. He holds a DPhil in International Relations from Oxford University. From 2004 to 2010 he was Associate Director and Distinguished Fellow at The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI). He was Visiting Professor, International Relations and Governance Studies Department, Shiv Nadar University, India in 2019. His books include The BRICS – A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), and co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy (Oxford University Press, 2013). His articles have appeared in leading journals such as International Organization, International Affairs, World Development, International Studies Review, and Global Policy Journal. In 2019 he was the first recipient of the Distinguished Studies Award, Diplomatic Studies Section, International Studies Association.

Carsten-Andreas Schulz

Carsten-Andreas Schulz is Assistant Professor in International Relations at the Department of Politics and International Studies and Tun Suffian College Lecturer at Gonville and Caius College, University of Cambridge. He holds a DPhil in International Relations from Nuffield College, Oxford University. His research has appeared or is forthcoming in journals including International Organization, European Journal of International Relations, and International Studies Quarterly, among others.

Notes

1 See, for example, Malamud and Viola (Citation2020). On the role of multilateral fora as platforms for influence for smaller countries, see Keohane (Citation1969), Panke (Citation2012), and Long (Citation2017a).

2 Our approach shares important similarities with role theory. Role theory argues that people’s actions are shaped by the different roles that they hold in society. It foregrounds the collective expectations attached to social positions and the way in which individuals interpret and play out their roles in their relationships with others (Biddle, Citation1986, p. 71). Because most adaptations in International Relations (IR) follow a symbolic interactionist approach of role theory centered on the social construction of role conceptions, they tend to understate the structural embeddedness of roles (but see Breuning, Citation2019). For a critique of the ‘oversocialized conception of human action’ that centers on structural embeddedness, see Granovetter (Citation1985).

3 According to Tilly (Citation1998, p. 399), relationalism defines ties as ‘continuing series of transactions to which participants attach shared understandings, memories, forecasts, rights, and obligations.’ Roles, accordingly, are understood as ‘bundles of ties attached to a single site’ and identities as an ‘actor's experience of a category, tie, role, network, or group, coupled with a public representation of that experience.’

4 Note that scholars disagree on whether social power (or ‘capital’) derives from ‘social closure’ (Putnam, Citation2000) or ‘structural holes’ (Burt, Citation1992).

5 On the use of network analysis to measure status, see Kinne (Citation2013), Renshon (Citation2016), Duque (Citation2018), and Røren and Beaumont (Citation2019).

6 Network research suggests that actors can occupy influential positions without necessarily being aware of their own centrality (see Padgett & Christopher, Citation1993). The marco effects of networks, and the understanding that actors have of them, should not be confused with the meaning that actors attach to their direct ties with others.

7 On the importance of geography in asymmetrical relations, see Womack (Citation2015); Long (Citation2022, p. 28).

8 Wehner (Citation2020), for example, discusses the case of Chile, which does not closely identify with its South American neighbors. As a result, the Southern Cone country has long pursued a policy of positioning itself as a ‘transpacific bridge’ between South America and the Asia-Pacific region (Wehner & Thies, Citation2014; Schulz & Rojas-De-Galarreta, Citation2022). Or consider Brazil as another South American example. Brazilian decisionmakers have long argued that the country occupies a bridge position between the Global North and South and should therefore be granted a seat at the table in instances of global governance (Burges, Citation2013).

9 Although our analysis focuses of sovereign states, it is worth noting that bridges and hubs operate at different scales. Bridges, as defined here, tend to be larger territorial entities. Rather many can be defined as globally prominent sites, as for example highlighted in the work on cities of Sassen (Citation2001). Connection can be made between top tier hub states such as Singapore and Qatar with historically important city states, above all London, New York and Tokyo.

10 Although the Lowy Institute’s database does not cover the diplomatic ties of all sovereign states, it provides up-to-date information on the number and type of missions (including consulates, consulates general, and embassies). The coding of additional cases follows the Lowy Institute’s (Citation2021) coding rules. Our network covers the diplomatic missions of 66 countries to 199 independent territories and states (N = 7,154).

11 As implemented by Raciborski’s (Citation2008) kountry command.

12 The idea that Mexico would gain importance due to its close relationship with the United States goes back, at least, to the the presidency of Luis Echeverría (1970-1976). We thank an anonymous reviewer for this observation.

13 With 52 missions, Mexico’s relationship with the United States is the ‘strongest’ in the entire dataset, followed by Canada (17) and Japan (15). The number of consulates is all the more striking considering that Mexico ‘only’ maintains 80 embassies worldwide, according to our data.

14 An investor fact sheet grounds this claim: ‘As of December 2021, Turkish Airlines flies to 333 destinations in 128 countries having the largest international flight network in the world’ (Turkish Airlines, Citation2021).

15 Turkey ODA followed a similar straddling approach, focusing on the Caucuses, Central Asia, and the Balkans and East Europe. Between 2011 and 2012, the increase in Turkey’s ODA was due to circumstances related to its response to the refugee crisis in its neighboring country, Syria. The share of Turkey’s total ODA allocated to Syria increased to 70 percent in 2015, compared to 65 percent in 2014 and 52 percent in 2013 (Piccio, Citation2017; OECD, Citation2018).

16 Specifically, among other components of diplomatic activity, former finance minister Yoon Jeung-hyun spent 88 days out of his two-year tenure in overseas trips, mostly to negotiate for the G20 (Ikenberry et al., Citation2013).

17 For example, the salience of the bridge role was deemphasized under the presidency of Park Geun-hye. The controversy over President Lee Myung-bak’s global initiatives shows that South Korea’s bridging strategy continues to face serious domestic hurdles.

18 South Korea has benefitted from the so-called Korean wave, encompassing tv dramas (k-drama) and pop music (k-pop). As early as 2004, Samsung Economic Research Institute released a report titled ‘The Korean Wave Sweeps the Globe’ analyzing the economic effects of the Korean Wave. The report identified four stages that countries fit into: enjoying Korean pop culture; buying Korean pop culture-related merchandise; buying ‘Made in Korea’ products; and a general preference for Korean culture’ (Jeong-Min, Citation2004). Although often considered an expression of South Korea’s ‘soft power,’ the Korean wave facilitated ties to foreign communities, notably in Latin America and the Middle East (Nye & Kim, Citation2019).

19 Ethiopia, for example, is often described as a potential hub in Chinese discourse (Venkataraman & Solomon, Citation2015). It shares many of the typical characteristics of global hubs. The headquarters of the African Union are located in its capital, Addis Adaba; Ethiopian Airlines has become the leading African connector; and there is a push to established Ethiopia as a medical hub. At the other end of the spectrum are cities, often ports, that seek to position themselves as hubs or nodal points, for example as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Vienna has historically been a diplomatic hub. However, it lacks most of the international connectiveness of other major metropoles today.

20 On Panamanian agency in the renegotiation of the Panama Canal Treaties, see Long, Citation2014.

References

- Abbott, A. D. (2016). Processual sociology. The University of Chicago Press.

- Altunisik, M. (2014). Geographical representation of Turkey’s cuspness: Discourse and practice. In M. Herzog & P. Robins (Eds.), The role, position and agency of cusp states in International Relations (pp. 25–42). Routledge.

- Babalı, T. (2009). Turkey at the energy cossroads. Middle East Quarterly, 25–33.

- Barabási, A.-L., & Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science, 286(5439), 509–512. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5439.509

- Baturo, A., Dasandi, N., & Mikhaylov, S. J. (2017). Understanding state preferences with text as data: Introducing the UN general debate corpus. Research & Politics, 4(2), 2053168017712821. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168017712821

- Baxter, P., Jordan, J., & Rubin, L. (2018). How small states acquire status: A social network analysis. International Area Studies Review, 21(3), 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/2233865918776844

- Bayer, R., & Keyman, E. F. (2012). Turkey: An emerging Hub of globalization and internationalist humanitarian actor? Globalizations, 9(1), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2012.627721

- Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12, 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.000435

- Bishop, M., & Cooper, A. F. (2018). The FIFA scandal and the distorted influence of small states. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 24(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02401003

- Borgatti, S. P., & Everett, M. G. (1992). Notions of position in social network analysis. Sociological Methodology, 22, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/270991

- Breuning, M. (2019). Role theory in politics and international relations. In A. Mintz, & L. Terris (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of behavioral political science (pp. 584–99). Oxford University Press.

- Burges, S. W. (2013). Brazil as a bridge between old and new powers? International Affairs, 89(3), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12034

- Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Harvard University Press.

- Call, W. (2003). Mexicans and Central Americans ‘can’t take any more’. NACLA Report on the Americas, 36(5), 9–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2003.11722471

- Carpenter, C. (2011). Vetting the advocacy agenda: Network centrality and the paradox of weapons norms. International Organization, 65(1), 69–102. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818310000329

- Çelikpala, M. (2019). Viewing present as history: The state and future of Turkey-Russia relations. EDAM: 25–28.

- Cepik, M., Chagas-Bastos, F. H., & Ioris, R. R. (2021). Missing the China factor: Evidence from Brazil and Mexico. Economic and Political Studies, 9(3), 358–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/20954816.2021.1933767

- Chagas-Bastos, F., & Franzoni, M. (2019). Frustrated emergence? Brazil and Mexico’s coming of Age. Rising Powers Quarterly, 3(4), 33–59.

- Cooper, A. F. (1997). Niche diplomacy: A conceptual overview. In A. F. Cooper (Ed.), Niche diplomacy: Middle powers after the cold War (pp. 1–24). Macmillan.

- Cooper, A. F. (2018). Entrepreneurial states versus middle powers: Distinct or intertwined frameworks? International Journal, 73(4), 596–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702018809532

- Cooper, A. F., & Shaw, T. S. (2009). The diplomacies of small states at the start of the twenty-first century: How vulnerable? How resilient? In A. F. Cooper & T. S. Shaw (Eds.), The diplomacies of small states: Between vulnerability and resilience (pp. 1–18). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Deutschmann, E. (2022). Mapping the transnational world: How We move and communicate across borders, and Why it matters. Princeton University Press.

- Deva, N. (2008). Turkey: A success in modernization, a failure in self-promotion. Turkish Policy Quarterly, 7(3), 25–31.

- Donor Tracker. (2018). South Korea. Available at: https://donortracker.org/country/south-korea(Accessed: 22 June 2022).

- Duque, M. G. (2018). Recognizing international status: A relational approach. International Studies Quarterly, 62(3), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqy001

- Dür, A., Baccini, L., & Elsig, M. (2014). The design of international trade agreements: Introducing a new dataset. The Review of International Organizations, 9(3), 353–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-013-9179-8

- Emirbayer, M. (1997). Manifesto for a relational sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 281–317. https://doi.org/10.1086/231209

- Erikson, E. (2013). Formalist and relationalist theory in social network analysis. Sociological Theory, 31(3), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275113501998

- Fan, T. P. C., & Lingblad, M. (2016). Thinking through the meteoric rise of middle-east carriers from Singapore airlines vantage point. Journal of Air Transport Management, 54, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2016.04.003

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2019). Weaponized interdependence: How global economic networks shape StateCoercion. International Security, 44(1), 42–79. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00351

- Fung, K.-F. (2001). Competition between the ports of Hong Kong and Singapore: A structural vector error correction model to forecast the demand for container handling services. Maritime Policy & Management, 28(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830119563

- Goddard, S. E. (2009). Brokering change: Networks and entrepreneurs in international politics. International Theory, 1(2), 249–281. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971909000128

- Goddard, S. E. (2018). Embedded revisionism: Networks, institutions, and challenges to world order. International Organization, 72(4), 763–797. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818318000206

- Gómez Bruera, H. F. (2015). To be or not to be: Has Mexico got what It takes to be an emerging power? South African Journal of International Affairs, 22(2), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2015.1053978

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469

- Granovetter, M. S. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/228311

- Green, M. J. (2017). The Korean pivot: The study of South Korea as a global power. Center for Strategic & International Studies.

- Hafner-Burton, E. M., Kahler, M., & Montgomery, A. H. (2009). Network analysis for international relations. International Organization, 63(3), 559–592. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818309090195

- Heine, J. (2013). From club to network diplomacy. In A. Cooper, J. Heine, & R. Thakur (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of modern diplomacy (pp. 54–69). Oxford University Press.

- Herzog, M., & Robins, P. (2014). The role, position and agency of cusp states in international relations. Routledge.

- Human Rights Watch. (2022). Qatar: Rights Abuses Stain FIFA World Cup.

- İçduygu, A., & Üstübici, A. (2014). Negotiating mobility, debating borders: Migration diplomacy in Turkey-EU relations. In H. Schwenken, & S. Ruß-Sattar (Eds.), New border and citizenship politics (pp. 44–59). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ikenberry, G. J., Mo, J., & Jongryn, M. (2013). The rise of Korean leadership: Emerging powers and liberal international order. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ingebritsen, C. (2006). Small states in international relations. University of Washington Press.

- Jackson, P. T., & Nexon, D. H. (1999). Relations before States: Substance, process and the study of World politics. European Journal of International Relations, 5(3), 291–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066199005003002

- Jackson, P. T., & Nexon, D. H. (2019). Reclaiming the social: Relationalism in anglophone international studies. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 32(5), 582–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1567460

- Jeong-Min, K. (2004). Korean wave sweeps the globe. Samsung Economic Research Institute.

- Jordaan, E. (2017). The emerging middle power concept: Time to Say goodbye? South African Journal of International Affairs, 24(3), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2017.1394218

- Kalin, I. (2011). Soft power and public diplomacy in Turkey. Perceptions: Journal of International Affairs, 16(3), 5–23.

- Kaya, A. (2020). Right-Wing populism and islamophobism in Europe and their impact on Turkey–EU relations. Turkish Studies, 21(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2018.1499431

- Keohane, R. O. (1969). Lilliputians' dilemmas: Small states in internatinal politics. International Organization, 23(2), 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830003160X

- Kinne, B. J. (2013). Network dynamics and the evolution of international cooperation. American Political Science Review, 107(4), 766–785. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000440

- Kösebalaban, H. (2020). Transformation of turkish foreign policy toward Syria: The return of securitization. Middle East Critique, 29(3), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2020.1770450

- Lee, J. W. (2021). Olympic winter games in Non-western cities: State, sport and cultural diplomacy in sochi 2014, PyeongChang 2018 and Beijing 2022. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 38(13-14), 1494–1515. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2021.1973441

- Lekakis, N. (2021). Fifa diplomacy and global actors’ interests in Cyprus: An unsuccessful ‘alliance’, 2013–2019. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 32(4), 829–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2021.1996726

- Li, Y. (2020). China and South Korea diplomatic relations present status and perspectives. Modern Economics & Management Forum, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.32629/memf.v1i1.123

- Lim, J. (2020). The Shangri-La dialogue: Ensuring Singapore’s relevance in defence diplomacy. Singapore Policy Journal, 8. https://spj.hkspublications.org/2020/11/08/the-shangri-la-dialogue-ensuring-singapores-relevance-in-defence-diplomacy/ (Last accessed 2 January 2023).

- Long, T. (2014). Putting the canal on the Map: Panamanian agenda-setting and the 1973 security council meetings. Diplomatic History, 38(2), 431–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/dh/dht096

- Long, T. (2017a). Small states, great power? Gaining influence through intrinsic, derivative, and collective power. International Studies Review, 19(2), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viw040

- Long, T. (2017b). It’s not the size, it’s the relationship: from ‘small states’ to asymmetry. International Politics, 54(2), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-017-0028-x

- Long, T. (2022). A small state’s guide to influence in world politics. Oxford University Press.

- Lowy Institute. (2021). Global Diplomatic Index. https://globaldiplomacyindex.lowyinstitute.org/country_rank.html.

- MacDonald, P. M. (2018). Embedded authority: A relational network approach to hierarchy in world politics. Review of International Studies, 44(1), 128–150. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210517000213

- Maihold, G. (2016). Mexico: A leader in search of like-minded peers. International Journal: Canada's Journal of Global Policy Analysis, 71(4), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702016687336

- Malamud, A., & Viola, E. (2020). Multipolarity is in, multilateralism out: Rising minilateralism and the downgrading of regionalism. In D. Nolte, & B. Weiffen (Eds.), Regionalism Under Stress (pp. 47–64 ). Routledge.

- Marx, A., & Soares, J. (2013). South Korea’s transition from recipient to DAC donor: Assessing Korea’s development cooperation policy. International Development Policy| Revue Internationale de Politique de développement, 4.2, 107–142. https://doi.org/10.4000/poldev.1535

- McCourt, D. M. (2016). Practice theory and relationalism as the new constructivism. International Studies Quarterly, 60(3), 475–485. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqw036

- MIKTA. (n.d). What Is MIKTA? http://mikta.org/about/what-is-mikta/?ckattempt=1.

- Muñoz, D., & Rivera, M. L. (2010). Development of Panama as a logistics hub and the impact on Latin America. PhD dissertaion. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Neto, O. A., & Malamud, A. (2019). The policy-making capacity of foreign ministries in presidential regimes: A study of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, 1946–2015. Latin American Research Review, 54(4), 812–834. https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.273

- Nexon, D. H., & Wright, T. (2007). What’s at stake in the American empire debate. American Political Science Review, 101(2), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055407070220

- Nye, J., & Kim, Y. (2019). Soft power and the Korean wave. In Y. Kim (Ed.), South Korean popular culture and North Korea (pp. 41–53). Routledge.

- OECD. (2018). Country statistical profiles 2018. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/country-statistical-profiles-key-tables-from-oecd_20752288?page=29.

- Padgett, J. F., & Christopher, K. (1993). Robust action and the rise of the Medici, 1400-1434. American Journal of Sociology, 98(6), 1259–1319. https://doi.org/10.1086/230190

- Panke, D. (2012). Dwarfs in international negotiations: How small states make their voices heard. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 25(3), 313–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2012.710590

- Parlar Dal, E. (2014). On Turkey’s trail as a “rising middle power” in the network of global governance: Preferences, capabilities, and strategies. Perceptions: Journal of International Affairs, 19(4), 107–136.

- Parlar Dal, E. (2016a). Conceptualising and testing the ‘emerging regional power’ of Turkey in the shifting ınternational order. Third World Quarterly, 37(8), 1425–1453. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1142367

- Parlar Dal, E. (2016b). Impact of the transnationalization of the Syrian civil War on Turkey: Conflict spillover cases of ISIS and PYD-YPG/PKK. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 29(4), 1396–1420. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2016.1256948

- Pellicer, O. (2006). México-A reluctant middle power. New powers in global change, dialogue on globalization. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Piccio, L. (2017). Post-Arab Spring, Turkey flexes its foreign aid muscle. Devex. https://www.devex.com/news/post-arab-spring-turkey-flexes-its-foreign-aid-muscle-82871 (Accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

- Qin, Y. (2018). A relational theory of world politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Raciborski, R. (2008). kountry: A Stata utility for merging cross-country data from multiple sources. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 8(3), 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0800800305

- Ravenhill, J. (2018). Entrepreneurial states: A conceptual overview. International Journal, 73(4), 501–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702018811813

- Renshon, J. (2016). Status deficits and war. International Organization, 70(3), 513–550. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818316000163

- Røren, P., & Beaumont, P. (2019). Grading greatness: Evaluating the status performance of the BRICS. Third World Quarterly, 40(3), 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1535892

- Sassen, S. (2001). Global cities and global city-regions: A comparison. In A. J. Scott (Ed.), Global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy (pp. 78–95). Oxford University Press.

- Schiavon, J. A., & Figueroa, B. (2019). Foreign policy capacities, state foreign services, and international influence: Brazil versus Mexico. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 30(4), 816–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2019.1673560

- Schulz, C.-A. (2019). Hierarchy salience and social action: Disentangling class, status, and authority in world politics. International Relations, 44(1), 88–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117818803434

- Schulz, C. A., & Rojas-De-Galarreta, F. (2022). Chile as a transpacific bridge: Brokerage and social capital in the pacific basin. Geopolitics, 27(1), 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2020.1754196

- Sharman, J. C. (2017). Sovereignty at the extremes: Micro-states in world politics. Political Studies, 65(3), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321716665392

- Shichor, Y. (2009). Ethno-Diplomacy: The uyghur hitch in sino-turkish relations. East West Centre.

- Slaughter, A.-M. (1997). The real new world order. Foreign Affairs, 76(5), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.2307/20048208

- Snyder, S. A. (2018). South Korea at the crossroads: Autonomy and alliance in an Era of rival powers. Columbia University Press.

- Thorhallsson, B. (2018). Studying small states: A review. Small States & Territories, 1(1), 17–34.

- Tilly, C. (1998). International communities, secure or otherwise. In E. Adler, & M. Barnett (Eds.), Security Communities (pp. 397–412). Cambridge University Press.

- Turkish Airlines. (2021). Investor fact sheet. https://investor.turkishairlines.com/documents/infografik/fact-sheet-2021.pdf.

- Venkataraman, M., & Solomon, G. M. (2015). The dynamics of China-Ethiopia trade relations: Economic capacity, balance of trade & trade regimes. Bandung: Journal of the Global South, 2(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40728-014-0007-1

- Waltz, K. (1979). Theory of international politics. Random House.

- Wehner, L. (2020). Chile’s soft misplaced regional identity. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 33(4), 555–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2020.1752148

- Wehner, L. E., & Thies, C. G. (2014). Role theory, narratives, and interpretation: The domestic contestation of roles. International Studies Review, 16(3), 411–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/misr.12149

- Wohlforth, W. C., Benjamin de Carvalho, H. L., & Neumann, I. B. (2017). Moral authority and status in international relations: Good states and the social dimension of status seeking. Review of International Studies, 44(3), 526–546. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210517000560

- Womack, B. (2015). Asymmetry and international relationships. Cambridge University Press.

- Workman, D. (2022a). Mexico’s top trading partners. Worlds Top Exports. https://www.worldstopexports.com/mexicos-top-import-partners/.

- Workman, D. (2022b). Turkey’s top trading partners. Worlds Top Exports. https://www.worldstopexports.com/turkeys-top-import-partners/.

- Workman, D. (2022c). South Korea’s top trading partners. Worlds Top Exports. https://www.worldstopexports.com/south-koreas-top-import-partners/.

- Yoshihara, T., & Holmes, J. R. (2011). Can China defend a “core interest” in the South China Sea? The Washington Quarterly, 34(2), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2011.562082