ABSTRACT

This article analyses the growing emphasis on mobilizing private finance for development. Previous critiques have rightly highlighted the dangers of this turn, which empowers the extractive operations of financial capital at the expense of states and populations in the global south. This article calls for a more careful examination of what is driving this trend. Many previous analyses treat the turn to private finance as reflective of the interests of finance capital. The article highlights two empirical challenges for this reading: there is demonstrably little actual interest on the part of finance in engaging with development projects, and formal development interventions have sought to mobilize private capital using broadly similar tools since at least the 1960s. I argue in the final part of this paper that we should view the private turn as the latest of many failure-prone efforts to grapple with intensifying social and ecological contradictions amid overaccumulation.

Introduction

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres’ foreword to the UN’s Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development’s 2021 Financing for Sustainable Development report, speaks to a prevalent piece of common sense in global Development:

Financing for sustainable development is at a crossroads. Either we close the yawning gap between political ambition and development financing, or we will fail to deliver the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) … . (United Nations, Citation2021, p. iii)

There is a growing critical literature engaging with this push (e.g. Banks & Overton, Citation2021; Dafermos et al., Citation2021; Gabor, Citation2021; Jafri, Citation2019; Karwowski, Citation2021; Mawdsley, Citation2018; Perry, Citation2021; Tan, Citation2021; Van Waeyenberge, Citation2015). In different ways, authors have emphasized the ways that this ‘private turn’ (Van Waeyenberge, Citation2015) in development finance empowers financial capital at the expense of exposing states, ecosystems, and people in the global south to new risks, as well as restricting policy space for development. Existing critiques are broadly correct about the dangers of the ‘private turn’. This article calls for sustained analysis of what is driving it. Insofar as the causes of the ‘private turn’ are explicitly considered, there is a frequent presumption that the turn to private finance reflects the interests of finance capital in carving out new spaces for the profitable deployment of speculative capital (see especially Dafermos et al., Citation2021; Gabor, Citation2021).

A reading that puts finance capital in the driver’s seat is hard to square with the dismal track record of these initiatives in terms of actually mobilizing private capital. Finance capital, in short, is often a curious presence-in-absence in global Development. As I’ll show further in the latter part of this article, efforts to mobilize private capital using some of the same tools have a much longer and more failure-prone pedigree than is commonly acknowledged. I’m certainly not the first to notice that the ‘private turn’ has fallen short of expectations (e.g. Attridge & Engen, Citation2019; Dembele et al., Citation2022). Indeed, Guterres’ comments betray a growing sense of frustration at how far short of expectations private finance has fallen in practice. Yet more explicit expressions of similar frustrations can also be found in specialist reports (some of which are cited below, e.g. Dembele et al., Citation2022, p. 33; Convergence, Citation2021). But previous critical discussions have generally not centred these failures analytically, nor reflected systematically on their implications in terms of how we should understand the role of finance capital in relation to the private turn. This article starts from the premise that we need to take these shortfalls seriously, especially for what they imply about the politics driving the push for private finance in Development.

In order to more clearly grasp the ambivalent place of finance capital in Development, this article draws on Hart’s analyses of d/Development (Hart, Citation2001, Citation2002, Citation2009; cf. Mawdsley & Taggart, Citation2022), alongside Harvey’s (Citation2006) discussion of ‘finance capital’. Hart (Citation2001, p. 650) distinguishes between ‘big-D’ ‘Development’ – the formal apparatus of ‘developmental’ intervention in the global south – and ‘small-d’ ‘development’ – the systemically uneven development of global capitalism. In Hart’s reading, ‘Big-D’ development is part and parcel of how ‘the conditions for global capital accumulation must be actively created and constantly reworked’ (Citation2001, p. 650) – a continual process of papering over contradictions of capitalist development necessary in order to enable its continuation. Hart takes as her task to analyse ‘how instabilities and constant redefinitions of official discourses and practices of Development since the 1940s shed light on the current conjuncture’ (Citation2009, p. 120). In short, tracking the continual adaptation and adjustment of Development offers us a valuable lens on the contradictions of development.

Harvey’s distinction between understandings of finance capital as a ‘process’, and finance capital as a ‘power bloc’ is helpful in thinking about the place of finance capital in relation to d/Development. Harvey notes that Marx’s notes on money and finance imply a definition of finance capital as ‘a particular kind of circulation process of capital which centres on the credit system’ (Citation2006, p. 283). This contrasts with more explicit uses of the term in later writing, which have tended to talk in terms of finance capital as ‘a power bloc which wields immense influence over the process of accumulation in general’ (Citation2006, p. 283). Harvey’s discussion here evidently predates the debate about the ‘financialization’ of development, but the latter conception of finance capital as power bloc would nonetheless fit with the way finance is conceived in much of the debate. A ‘power bloc’ view can tend to lend finance capital an illusory coherence, and obscure its complex and contradictory linkages with the wider circuits of capitalist accumulation. Most importantly for present purposes, it can nudge analyses towards a certain functionalism – interventions privileging the interests of finance must be driven by the actions of the ‘power bloc called “finance capital”’ (Harvey, Citation2006, p. 283). We can usefully follow Harvey’s insistence on a ‘process’ view, in which finance capital is instead seen as a form of circulation process which must be situated in the wider uneven development of global capitalism. Tracing the dialectic of d/Development is particularly informative in relation to this latter task.

This approach suggests a shift in emphasis: ‘Big-D’ Development increasingly relies on encouraging finance capital to circulate in particular ways, which are at odds with the actually existing organization and infrastructures of the credit system. The private turn thus represents the latest in a series of intensifying efforts to grapple with the limits posed on Development practice by embedded patterns of uneven development. Amidst entrenched patterns of uneven development, hopeful moves to attract private capital to invest in poverty reduction, climate adaptation and mitigation, and badly needed infrastructure increasingly represent some of the only readily available means by which state and international governors can seek to mitigate intensifying social and ecological contradictions.

This argument is developed in four steps. The first section introduces the major elements of the ‘private turn’, and summarizes key debates about them. The following two sections trace out two arguably under-analysed features of these trends – the patently uneven involvement of finance capital itself in financing Development, and the long historical roots of both ‘finance gap’ framings and of efforts to plug them with private capital. The final section turns to a wider discussion of how MF4D and like initiatives reflect wider conjunctural shifts in the uneven development of global capitalism.

Sustainable development and the ‘financing gap’

Preparatory discussions for the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals identified ‘enormous unmet financing needs’, and a concomitant need to ‘un[lock] the transformative potential of people and the private sector’ in order to address that gap (UN, Citation2015, p. 1). On this basis, the World Bank and other MDBs laid out what was initially called the ‘Billions to Trillions’ agenda in 2015. The ‘ambitious’ 2030 SDGs ‘demand equal ambition in using the “billions” in ODA and in available development resources to attract, leverage, and mobilize “trillions” in investments of all kinds’ (World Bank, Citation2015b, p. 1). The ‘Billions to Trillions’ report emphasizes a wide range of interventions aimed at improving the ‘environment’ for private investment:

Governments play a critical role in providing a conducive investment climate through supportive governance structures, competition policy, hard and soft infrastructure and instruments that foster healthy, commercially sustainable markets. (World Bank, Citation2015a, p. 12)

Daniela Gabor compellingly describes these developments as epitomizing the rise of a ‘Wall Street Consensus’ – a new ‘development mantra’ aiming ‘to create investible development projects that can attract global investors’ (Citation2021, p. 430). Gabor’s account highlights both the growing power of institutional investors and the central role of macro-financial policies. The ‘Wall Street Consensus’, in the words of Dafermos et al. (Citation2021, p. 239) is taken to ‘reflec[t] attempts by global finance to expand in the Global South and policy initiatives that aim to facilitate that expansion’. In this sense, the Wall Street Consensus represents a hegemonic framing of Development articulated around what, in Harvey’s terms, we could usefully call a ‘power bloc’ centred on finance capital. Dafermos et al. (Citation2021, p. 239) argue that the Wall Street Consensus ‘successfully articulated a new development narrative shared by G20 governments, multilateral development banks and private financial actors from institutional investors and their asset managers to global and local banks’. For Gabor, the ‘Wall Street Consensus’ is thus Development ‘designed by finance capital seeking to expand into new areas’ (Citation2021, p. 436). The state in development is increasingly oriented toward a role radically subordinated to the needs to global finance capital. While Gabor’s account is particularly influential among recent engagements, similar readings are reflected, notwithstanding important differences of emphasis, across much of the literature on the financialization of development (e.g. Carroll & Jarvis, Citation2014; Musthaq, Citation2021).

But the actual relationship of finance capital to these initiatives is arguably less clear than this picture suggests. Mawdsley rightly notes that ‘converting the “mundane”, into investible objects and tradeable commodities (whether risk, the weather, the control of infectious diseases, girls’ education or Tanzanian government pensions) requires work’ (Citation2018, p. 271). What needs to be unpicked more explicitly is who is undertaking these kinds of work, why, and with what implications? Gabor’s (Citation2021) argument – and more generally, in many cases, the concept of ‘financialization’ – provides an intuitive, and prima facie compelling, answer: This is action for and on behalf of finance capital. But it’s not clear this is an entirely satisfactory diagnosis.

Previous critical engagements with the ‘Wall Street Consensus’ have raised questions about the role of states in fostering the turn to private capital. Schindler et al. (Citation2022) note that peripheral states have increasingly sought to facilitate the pursuit of strategic objectives through engagements with ‘Wall Street Consensus’ forms of de-risking. Derisking strategies, then, are not as starkly determined by finance capital as the accounts of Gabor (Citation2021) and others would imply. Alami et al. (Citation2021) point to a wider shift in the place of the state in Development, with a cautious embrace of a more active role for the state in directing, even owning capital, in response to wider ideological and geopolitical shifts. These pieces, in different ways, suggest that the political underpinnings of the private turn require further unpicking. The present argument does so from a slightly different angle, emphasizing the fundamental contradictions around which the d/Development dialectic operates. In order to do this, over the next two sections I highlight two respective features of the ‘private turn’ – the relative disinterest of finance capital, and its longer historical roots – in turn.

The ambivalent involvement of finance capital

As this section demonstrates, both in terms of the spatial distribution of private financing and in terms of the kinds of projects and activities that are funded (or not), capital’s interest in Development remains highly uneven (Attridge & Engen, Citation2019). Bigger and Webber (Citation2021) hit on an important aspect of the problem here in describing the rise of ‘green structural adjustment’ in the World Bank’s urban infrastructure programming. The Bank, they argue, seeks to produce cities as sites of investment through policy conditionalities, describing this as a ‘preparatory program for creating “surfaces” to which spatially fixing capital might adhere’ (Citation2021, p. 37, emphasis added). Crucially, though, ‘not all frontiers are equally investable, nor do they all promise lucrative returns’ (Citation2021, pp. 47–48). There is, undoubtedly, a glut of finance capital which exists alongside a desperate need for resources and investment in many areas. What is perhaps less clear is whether and how far the holders of finance capital are actually much interested in carving investable assets out of the needs of Development. In aggregate, the answer seems to be that they’re not.

To take one high-profile example, in 2015 when the 21st Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change renewed the target of mobilizing USD 100 billion per year in climate finance for developing countries, it was projected that a third of this would be delivered through the mobilization of private investment. Between 2016 and 2019 – as shows – less than half of the private finance of 33.3 billion target has ever been met (OECD, Citation2021). Indeed, while public and multilateral climate financing has increased marginally since the 2015 pledge (albeit remaining significantly below promised levels), there has been little notable change in private ‘climate-linked’ financing to developing countries. Not only has private finance fallen short of targets, then, it has hardly responded at all to the initiatives adopted in the aftermath of the Paris Agreement. Even setting aside the important question of whether private financing can deliver effective or equitable climate action, private finance for Development activities linked to the climate crisis is seemingly simply not forthcoming.

Table 1. Climate finance provided or mobilized by donor countries, 2013–2019.

The sectoral and geographical distribution of private finance for Development has also been profoundly uneven. An OECD survey of transactions between 2012 and 2016 found that upwards of 80% of private finance mobilized through Development interventions went to projects in energy, banking, mining and construction, and industry (the considerable bulk of which went to the former two). Virtually none funded projects in health, education, or civil society (OECD, Citation2018, p. 25). With respect to blended finance transactions in particular, estimates from the OECD and from industry advocates Convergence also show that very little blended finance reaches low-income countries (cf. Attridge & Engen, Citation2019). An OECD-run survey conducted in 2018 found that only 12% of total blended funds, and 7% of commercial funds invested in blended finance vehicles, were directed to least-developed countries (Basile & Dutra, Citation2019, p. 49). This proportion, notably, was ‘consistent with the proportion of total private finance mobilised going to LDCs between 2012–2017’ (Citation2019, p. 49). A follow-on survey in 2020 found that the volume and proportion of blended finance directed to LDCs had fallen in the intervening years, concluding that ‘to date, blended finance has not been able to attract significant financial resources to LDCs’ (Dembele et al., Citation2022, p. 33). Convergence notes, commenting on similar data, that ‘Challenges arise when applying blended finance in LDC contexts, in part due to the relative … appetite from commercial investors’ (Convergence, Citation2021, p. 21).

We see similar patterns in the activities of the largest asset managers, which could be taken as the foremost institutional manifestations of global finance capital (see Fichtner & Heemskerk, Citation2021). As Buller and Braun note (Citation2021, p. 2), in 2021 the two largest such firms globally (BlackRock and Vanguard), managed roughly USD 9 and 8 trillion worth of assets, respectively – or, enough for each to buy all the listings on the London Stock Exchange twice over.Footnote1 Alongside pensions and mutual funds, these make up a considerable portion of the pools of institutional capital which MF4D and the like seek to attract. Some significant pools of capital are increasingly under the control of a handful of states through sovereign wealth funds and other state-owned investment vehicles (see Alami et al., Citation2021), but these are neither exempt from the wider pressure to ensure returns, nor generally controlled by peripheral states. Blackrock's activities are especially notable insofar as it has also increasingly positioned itself publicly as a leading face of the ‘Wall Street Consensus’. During COP 26 in Glasgow, for instance, Blackrock launched its ‘Climate Finance Partnership’ (CFP) to considerable fanfare. CFP – a blended finance vehicle dedicated to climate-themed investments in developing countries – is a quintessential ‘Wall Street Consensus’ project in many ways.

It is, in this respect, worth noting to begin that CFP is relatively minuscule next to Blackrock’s overall portfolio of assets under management – raising an initial USD 673 million (Louch, Citation2021). In 2021, Blackrock spent more than triple this amount (USD 2.17 billion) on new real estate acquisitions alone (Blackrock, Citation2022, p. 9). More generally, tailored ‘alternative’ investments of this kind are unquestionably peripheral to Blackrock’s overall asset management strategy. The firm’s assets under management are heavily concentrated in equities and fixed income securities (e.g. corporate and sovereign bonds) – see . Or, put slightly differently, the largest asset managers continue to prefer investments predominantly in highly liquid financial securities, those more specialized in 'alternative' assets (e.g. Blackstone) are arguably even more concentrated on the core economies. By some distance Blackrock’s largest ‘impact’ funds consist of a series of green bond indices predominantly made up of European sovereign green bonds. In total, these manage roughly USD 10 billion.Footnote2 Moreover, if there is a crisis of capitalist profitability in general, it has left Blackrock largely unscathed. Blackrock’s returns remain high amidst concerted action across leading economies to maintain and boost asset prices (Adkins et al., Citation2021; Langley, Citation2021). Blackrock itself, equally, reports operating margins of 35% or higher over the years 2017–2021, over 38% in every year except 2020 (Blackrock, Citation2022, p. 2). While this figure represents fee income to the company itself and not, directly, returns on assets under management, it does suggest that the firm is not in dire need of new outlets for investment beyond already the deep and liquid core financial markets.

Table 2. Blackrock long-term assets under management, 2017–2021, in USD billions, Total AUM includes cash reserves not included in chart, and may not add precisely due to rounding.

This clearly matches a wider pattern. A number of authors have, in different ways, linked the stagnation of core economies to the growing concentration of wealth and concommitant emphasis on investment in rent-generating assets rather than in production (Benanav, Citation2020; Christophers, Citation2020; Moraitis, Citation2021; Schwartz, Citation2021). There is considerable debate about the drivers of these tendencies. For the moment, though, the key point is that the frontiers of greatest interest to finance capital seem to be much more in the realm of creating rent-bearing assets in core economies (see Christophers, Citation2020) – notably through intellectual property regimes (see Schwartz, Citation2021), digital platforms (Sadowski, Citation2020), and growing control over housing (Christophers, Citation2021; Fields, Citation2019).

The crucial point here is that, across the board, it is not at all clear that either finance capital in aggregate or its chief organizational manifestations are actually particularly interested in ‘maximizing’ their opportunities to invest in Development projects. All of this suggests that the role of finance capital in driving these shifts in Development strategy is less direct than many accounts of the financialization of development often suggest. MF4D may prioritize the interests of the financial circuits of capital, but does not do so at the behest of finance capital. This point is further supported by the fact that similar interventions, in fact, have a very long pedigree, as I show in the next section.

The long pre-history of the private turn

While contemporary modes of mobilizing finance are novel in important ways, they form part of a longer lineage of efforts to coax recalcitrant finance capital into investing in Development. This longer history is not entirely overlooked in previous analyses of MF4D or the ‘Wall Street Consensus’. Gabor, for one, locates direct precursors to contemporary ‘de-risking’ in the activities of German development bank KfW from the 1990s, and collaborative work between Deutsche Bank and the United Nations Development Programme starting in 2011 (Citation2021, pp. 433–434). Here I want to suggest that we might usefully read MF4D and its immediate predecessors as the latest iterations of set of tools with a much longer pedigree. While a complete history would be beyond the scope of this paper, a brief example should suffice to show that both ‘finance gaps’ and failed efforts to resolve them by laying the groundwork for prospective flows of private finance are longstanding features of neoliberal development. Housing is especially useful to consider here, as one of the earliest areas where neoliberal development frameworks were articulated in practice (see Alexander, Citation2012; Rolnik, Citation2013; Soederberg, Citation2017; Van Waeyenberge, Citation2018).

John F.C. Turner and his Freedom to Build (Turner, Citation1972), were hugely influential over World Bank policy on housing in the 1970s. Turner articulated an approach to housing development which was deeply skeptical of state involvement in housing, celebrated the self-organizing capacity of slum-dwellers, and called for targeted ‘self-help’ programmes providing access to basic services and secure tenancy. The Bank’s own employees and consultants cite Turner’s influence directly (Werlin, Citation1999, p. 1523). From the mid-1970s, the Bank’s discussions of housing policy reflect an explicit embrace of informal housing as legitimate dwellings. What’s critical for present purposes is that, for the Bank much more than Turner, this came with an emphasis on regularizing residents’ land tenure as a means of granting access to credit (Grimes, Citation1976, p. 26).

The Bank’s first housing project was a site and service scheme in Senegal (see Van Waeyenberge, Citation2018, p. 293). The appraisal report for the project tellingly makes note of the government’s turn to a sites and services approach based on ‘a growing awareness of the impossibility of providing more than a small proportion of families’ with homes on a public or state-owned enterprise basis (World Bank, Citation1973, p. 6). The project relied instead on mobilizing community resources, a move that was notably explicitly justified as a means of ‘freeing’ public resources to be spent elsewhere. But if the Senegalese project turned to self-help the assets and incomes of informal settlement-dwellers themselves, the broader approach to housing very quickly started to reflect a recognition that scaling-up these projects required injections of outside capital.

To a considerable extent, the response at the Bank and elsewhere to these issues, and parallel questions like agricultural credit (see Bernards, Citation2022a) presaged and help shape key elements of the Washington Consensus agenda later pushed through structural adjustment – particularly around the liberalization of interest rates. Restrictions on access to credit for housing were largely blamed on government interference, particularly caps on interest rates, which could be remedied with liberalization (World Bank, Citation1975, p. 30). A study commissioned by the Bank on financing housing in developing countries, for instance, concludes that: ‘Points of view that interpret usury as an evil have often led to the pegging of commercial bank interest rates at artificially low levels … With excessive demand thus created by controlled interest rates, banks prefer lending to the least risky borrowers’ (Grimes, Citation1976, p. 57).

Yet this ‘negative’ liberalization was always accompanied in practice by more active efforts to shift the risk-reward calculation of private investors. One prominent example here is the Housing Investment Guaranty Fund (HIGF), administered by USAID. The HIGF was launched, with $10 million, by the US Congress in 1961. By the mid-1970s, it guaranteed more than $1 billion in loans. The HIGF was designed explicitly to mobilize American commercial lenders for housing projects in favoured countries in the global south. The HIGF worked with national governments and local lenders to design projects, often with a strong ‘institutional development’ component, aiming to:

assist in the accumulation of local capital for long-term mortgage finance operations, the promotion of effective cost recovery systems, the reduction of subsidies, the elimination of unrealistic standards for Basic services and the stimulation of the private sector to expand economic development opportunities in urban centers. (USAID, Citation1983, p. 3.2)

It is worth noting that these interventions (like more recent experiments) generated deeply uneven outcomes that often mirrored the existing distribution of capital flows. The HIGF was never well-suited to mobilizing finance for the poorest people or countries, a point acknowledged explicitly in a number of evaluations: ‘[USAID] does not believe that countries with very low per capita incomes are suitable recipients for [HIGF] project loans, since these loans are made on commercial rather than concessional terms’ (USGAO, Citation1978, p. 3). Likewise, ‘The commercial-rate financing provided under the … program is not, for the most part, appropriate to meet either the shelter needs of the very poorest income levels (below the 15th income percentile)’ (USGAO, Citation1978, p. 5).

The point here is that we can see a kind of leveraging of public funds to derisk private investment, with the aim of mobilizing finance capital to meet a Development challenge considered to be beyond the capacity of public resources to solve, as far back as the 1960s. The ‘finance gap’ and efforts to coax finance capital into Development projects, are thus in important senses constitive problems shaping the trajectory of neoliberal approaches to Development rather than recent emergences. These projects on housing developed prior to, and continued alongside, the violent ‘ground-clearing’ intervention that was structural adjustment. The HIGF operated on a relatively restricted scale, and did not reach the level of systematic framing of development practice that MF4D did. However, similar modalities of practice have been visible across the entire history of neoliberal Development (see Bernards, Citation2022b). Crucially, as with more recent interventions, there is little indication this has been driven directly by the interests of finance capital. In short, development agencies and states have spent quite a lot of time, with variable success, and over several decades, trying to assemble Development projects into asset streams that might interest finance capital. The sheer persistence of this broad mode of practice reinforces the argument here that it is reflective of more embedded contradictions than of active intervention on the part of finance capital.

Recasting the finance gap: d/Development amidst overaccumulation

The work being undertaken under the rubric of mobilizing private finance for Development is fundamentally anticipatory and uncertain. It is work seeking to guide finance capital into activities that will further the ‘palliative’ functions (per Hart, Citation2009) of Development. The turn to private finance is often, or even largely, about states and multilateral institutions with restricted means trying to coax finance capital into circulating in ways the latter is reluctant to do. What is needed, then, is an account of the private turn that can account for the features outlined in the two previous sections: (1) the relative disinterest of finance capital in Development projects, and (2) the long-run persistence of similar mechanisms. Following Hart’s (Citation2001, Citation2009) emphasis on the dialectic of d/Development, I argue in this final section that the private turn reflects efforts to articulate the key functions of Development – that is, smoothing the contradictions, mitigating the worst effects of capitalist development – against the limits posed by increasingly uneven control over capital.

The private turn is an effort to mitigate the worst consequences of the restructuring of the global economy since the 1970s, facilitated by processes of neoliberalization, while working within the limits of those processes. To give a very short summary: Large-scale privatization and contracting out of state enterprises has led to the widespread ‘rentierization’ of core economies (see Christophers, Citation2020). Global production has been radically restructured in ways that have extended the reach of corporate power, both directly and indirectly, across a number of sectors. Manufacturing and agricultural industries in particular have increasingly come to be dominated by complex supply chains. The lowest-margin, highest risk, and most competitive aspects of production processes have been externalized to locations primarily in the global south. Studies across a number of sectors point to a tendency for firms beholden to equity markets to prioritize share buybacks and dividends, driving supply chain re-organizations and at times underinvestment in productive capacity (Milberg, Citation2008), and traced trends towards increasing monopoly and monopsony power in global value chains (Selwyn & Leyden, Citation2022).

The concentration of capital in this sense has been intimately linked to accelerating social and ecological crises. The acceleration of climate breakdown is perhaps the most visible manifestation, but not the only one. The last few decades have been marked by intensifying precarity and exposure to climate breakdown for working classes globally (see Bernards & Soederberg, Citation2021). Authors have highlighted links between the re-organization of global supply chains and hyper-exploitation through various forms of unfree labour (Phillips, Citation2016). Selwyn (Citation2019) argues that given these imbalances and tendencies towards the hyper-exploitation of workers at the periphery of global supply chains, they are better understood as ‘global poverty chains’. Rural producers in the global south, meanwhile, are increasingly displaced from land and livelihoods by land grabbing, volatile prices, and the effects of the above processes amplified longer-run dynamics of exposure to variable climates (see Li, Citation2009; Natarajan et al., Citation2019).

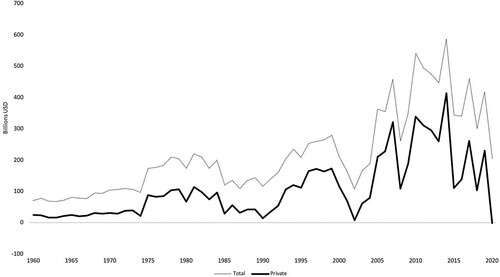

This global restructuring has also severely restricted the means by which states and multilateral agencies are able to respond to these contradictions. It has created the conditions for recurrent debt crises and deepened quasi-permanent conditions of austerity in global north and (especially) south. Restructured global financial systems have tightened persistent restrictions on resources available to developing country governments (see Alami et al., Citation2022). Private investment in peripheral countries is thus is increasingly determined by global market conditions over which they have little control (see Alami, Citation2020; Bassett, Citation2018; Bonizzi et al., Citation2020). We can see a fairly clear illustration of this ‘big picture’ in , which shows the total volume of ‘Development Flows’, as measured by the OECD, into DAC-recipient countries. The volatility of private investment accounts for much of the overall volatility of investment and capital inflows – as is clear from how closely total flows (including official development aid) track private inflows. These pressures have been exacerbated by political imperatives to privatize key industries and assets and to restrict public spending, especially for social purposes (see Kentikelenis et al., Citation2016).

Figure 1. Total and private ‘Development Flows’ to DAC countries, 1960–2020, in USD Billions. Source: OECD.

Neoliberal development has, in short, generated a conjuncture marked by what we could call ‘organic crisis’ in Gramsci’s (Citation1971) terms. The climate crisis and other accelerating contradictions call for the mobilization of social resources on a global scale, at the same time as the concentration of capital, entrenchment of financial subordination, and weakening of state institutions has stripped away many of the mechanisms by which public responses to these might be asserted.

Re-framing private finance in d/Development

If one side of the picture is the tightening constraints on resources available for Development, the other is the accelerating concentration of capital, and the emergence of massive asset managers as major global shapers of investment allocation. The connection between the growing concentration of capital, deprivation, and the ‘private turn’ is made explicit both by its critics and by its promoters. Bayliss and Van Waeyenberge – writing about the revival of public–private partnerships in particular, but making a point of wider relevance – note a substantive shift in the ways that public–private partnerships are understood: ‘PPP policy is now driven far more by the availability of global finance than by the previously perceived potential for efficiency gains through privatisation’ (Citation2018, p. 581). This is a critical distinction – the promotion of PPPs is a means of attracting overaccumulated capital into involvement in formal Development, not necessarily something being done at the behest of finance capital. For advocates of private financing, precisely the point is often that we simply have no choice but to try to steer the largest pools of capital available. In the words of one Financial Times columnist, writing about the challenges facing the development of ESG ratings for financial markets: ‘Regardless of your view on the power large companies wield, harnessing it still seems one of the most promising ways to address our greatest collective challenges’ (Edgecliffe-Johnson, Citation2021).

This kind of anticipatory positioning is evident in some major multilateral and donor discussions of the role of private finance. Private investment – particularly held in institutional funds and asset management – is framed as a potentially extensive pool of untapped capital. Meanwhile, a USAID-commissioned guide to MF4D, produced by Deloitte notes that ‘Private capital is abundantly available and seeking investment in … developing economies. Thus, development agencies can play a critical role in facilitating that investment’ (USAID, Citation2019, p. 5). A World Bank report on infrastructure and urban ‘resilience’ notes that

There is large funding potential among traditional as well as non-traditional investors for urban infrastructure. Long-term-investors such as pension funds and insurance companies have expressed willingness to increase their allocation to this asset class … And USD 106 trillion of institutional capital, in the form of pension and sovereign-wealth funds, is available for potential investment. (World Bank, Citation2015c, p. 57)

The point here is that, with increasingly limited means by which to ‘steer’ capital directly, and faced with volatile movements of capital, Development is increasingly framed in terms of laying the groundwork in anticipation of attracting spatially fixing capital. Efforts to plug various ‘financing gaps’ generated by the uneven geography of finance capital often look like precisely the reverse of capital ‘prospecting’ for new streams of income (in Leyshon & Thrift’s, Citation2007 evocative phrase). Here Harvey’s distinction between ‘finance capital’ as a power bloc and finance capital as a particular kind of circulation process is particularly helpful. Seeking means of addressing the pervasive tension between the interests of particular capitals, and the reproduction of capitalism as a whole, as Clarke notes, is the fundamental activity of the capitalist state (Citation1988, p. 122). The growing concentration of capital and intensification of uneven development have amplified this tension and rendered it particularly acute, while restricting the available means by which it can be addressed. State and multilateral managers are increasingly oriented towards navigating this tension, and barring widespread political support for outright expropriation, appealing to the interests of asset managers in hopes of aligning the circulation of finance capital with the needs of Development is one of few remaining alternatives.

Critically, framing the ‘private turn’ in this way – as an error-prone effort to grapple with a deepening crisis of overaccumulation and uneven development – casts the power of finance and of major asset managers differently. The power of finance here is primarily not exercised directly as a 'power bloc' steering Development programming, but in the sense that Development often cannot proceed without finding a way of enrolling finance capital. The concentration of capital generates crucial social and ecological contradictions, while also simultaneously posing barriers to their resolution. State institutional structures have in many cases been hollowed out, and fiscal constraints in the global south in particular have been progressively tightened. In this context we should read the turn to efforts to coax private capital into investing in Development as efforts by state and multilateral governing institutions to re-shape flows of capital in ways that will mitigate these contradictions without requiring radical changes to existing structures of accumulation.

Conclusion

The ‘financing gap’, and efforts to resolve it by escorting capital into Development are best seen as the product of a conjuncture in which intensifying and interconnected tendencies towards overaccumulation in a few core markets and deprivation and underdevelopment in much of the global south increasingly threaten both the social legitimacy and the ecological and material durability of global capitalism. Efforts to mobilize private finance are (likely doomed) means of mitigating these tendencies, rather than initiatives directly at the behest of a power bloc called ‘finance capital’.

In concluding here, I want to underscore why it’s useful to cast the problem this way. Previous critics are, broadly, right about the hazards of the Wall Street Consensus. But more attention is needed to its political drivers. The private turn is reflective not (only) of the capture of Development by financial interests, but of state and multilateral action grappling with embedded contradictions of overaccumulation and uneven development (see Copley, Citation2022). Moreover, these are contradictions with which neoliberal modes of Development practice have been grappling, arguably, from the beginning. MF4D, and the recourse to similar mechanisms over the much longer-run, are embedded in more fundamental, longer-run, structural contradictions in contemporary capitalism.

This casts the power of finance capital differently. As Mawdsley (Citation2018) in particular has noted in, assembling assets streams amenable to investment out of Development objectives takes considerable work. It’s notable that, both in the case of more contemporary MF4D and longer-term developments, much of this work is being undertaken by states and international governors, rather than by finance capital itself. While the structural power of finance capital in the context of global overaccumulation is important, finance capital figures marginally as a direct driver of MF4D or its predecessors. This matters insofar as what it can tell us about the politics of the ‘private turn’. The political problem, then, is not solely or even primarily how to reduce the influence of global finance, but the rather more difficult question of how the deep-rooted contradictions of capitalist development might be overcome.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the anonymous reviewers at this journal for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript, which have greatly improved the final product.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nick Bernards

Nick Bernards is Associate Professor of Global Sustainable Development at the University of Warwick. He is author of The global governance of precarity (Routledge, 2018) and A critical history of poverty finance (Pluto, 2022).

Notes

1 The figure for Blackrock is now over USD 10 trillion, see .

2 Based on information available from Blackrock here, as of September 2022: https://www.blackrock.com/uk/products/product-list.

References

- Adkins, L., Cooper, M., & Konings, M. (2021). Class in the twenty-first century: Asset inflation and the new logic of inequality. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(3), 548–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19873673

- Alami, I. (2020). Money power and financial capital in emerging markets: Facing the liquidity tsunami. Routledge.

- Alami, I., Alves, C., Bonizzi, B., Kaltenbrunner, A., Koddenbrock, K., Kvangraven, I., & Powell, J. (2022). International financial subordination: A critical research agenda. Review of International Political Economy, https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2022.2098359

- Alami, I., Dixon, A. D., & Mawdsley, E. (2021). State capitalism and the new d/Development regime. Antipode, 53(5), 1294–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12725

- Alexander, A. (2012). “A disciplining method for holding standards down”: How the World Bank planned Africa’s slums. Review of African Political Economy, 39(134), 590–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2012.738603

- Attridge, S., & Engen, L. (2019). Blended finance in the poorest countries: The need for a better approach. Overseas Development Institute.

- Bamberger, M. (1983). The role of self-help housing in low-cost shelter programmes for the third world. The Built Environment, 8(2), 95–107.

- Banks, G., & Overton, J. (2021). Grounding financialization: Development, inclusion, and agency. Area, https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12740

- Basile, I., & Dutra, J. (2019). Blended finance funds and facilities – 2018 survey results, part I: Investment strategy (OECD Development Cooperation Working Paper 59). OECD.

- Bassett, C. (2018). Africa’s next debt crisis: Regulatory dilemmas and radical insights. Review of African Political Economy, 44(154), 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2017.1313730

- Bayliss, K., & van Waeyenberge, E. (2018). Unpacking the public-private partnership revival. Journal of Development Studies, 54(4), 577–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1303671

- Benanav, A. (2020). Automation and the future of work. Verso.

- Bernards, N. (2022a). The World Bank, agricultural credit and the rise of neoliberalism in global development. New Political Economy, 27(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1926955

- Bernards, N. (2022b). A critical history of poverty finance: Colonial roots and neoliberal failures. Pluto Press.

- Bernards, N., & Soederberg, S. (2021). Relative surplus populations and the crises of contemporary capitalism: Reviving, revisiting, recasting. Geoforum, 126, 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.12.009

- Bigger, P., & Webber, S. (2021). Green structural adjustment in the world bank’s resilient city. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1749023

- Blackrock. (2022). Investing with purpose: Blackrock 2021 annual report.

- Bonizzi, B., Laskaridis, C., & Griffiths, J. (2020). Private lending and debt risks of low-income developing countries. Overseas Development Institute.

- Buller, A., & Braun, B. (2021). Under new management: Share ownership and the rise of UK asset manager capitalism. Common Wealth.

- Carroll, T., & Jarvis, D. (2014). Financialisation and development in Asia under late capitalism. Asian Studies Review, 38(4), 533–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2014.956284

- Christophers, B. (2020). Rentier capitalism: Who owns the economy, and who pays for it? Verso.

- Christophers, B. (2021). How and why US single-family housing became an investor asset class. Journal of Urban History. https://doi.org/10.1177/00961442211029601

- Clarke, S. (1988). Keynesianism, monetarism, and the crisis of the state. Edward Elgar.

- Convergence. (2021). The state of blended finance, 2021. Convergence.

- Copley, J. (2022). Decarbonizing the downturn: Addressing climate change in an age of stagnation. Competition and Change. https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294221120986

- Dafermos, Y., Gabor, D., & Mitchell, J. (2021). The Wall Street Consensus in pandemic times: What does it mean for climate-aligned development? Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 42(1–2), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2020.1865137

- Dembele, F., Randall, T., Vilalta, D., & Bangun, V. (2022). Blended finance funds and facilities: 2022 survey results (OECD Development Cooperation Working Paper 107). OECD.

- Edgecliffe-Johnson, A. (2021, August 23). Business can stop the ESG backlash by proving it’s making a difference. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/2e77a83b-bf88-4efb-8294-31db74db03c5

- Fichtner, J., & Heemskerk, E. (2021). The new permanent universal owners: Index funds, patient capital, and the distinction between feeble and forceful stewardship. Economy and Society, 49(4), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2020.1781417

- Fields, D. (2019). Automated landlord: Digital technologies and post-crisis financial accumulation. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19846514

- G20. (2017). Principles of MDBs’ strategy for crowding-in private sector finance for growth and sustainable development. G20 International Financial Architecture Working Group.

- Gabor, D. (2021). The Wall Street Consensus. Development and Change, 52(3), 429–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12645

- Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks. (Quintin Hoare & Geoffrey Howell Smith, Trans.). Lawrence and Wishart (Original work published 1971).

- Grimes, O. F. (1976). Housing for low-income urban families: Economics and policy in the developing world. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hart, G. (2001). Development critiques in the 1990s: Cul de sacs and promising paths. Progress in Human Geography (4), 649–658.

- Hart, G. (2002). Geography and development: Development/s beyond neoliberalism? Power, culture, political economy. Progress in Human Geography (6), 812–822.

- Hart, G. (2009). Development/s after the meltdown. Antipode (s1), 117–141.

- Harvey, D. (2006). The limits to capital. Verso.

- Jafri, J. (2019). When billions meet trillions: Impact investing and shadow banking in Pakistan. Review of International Political Economy, 26(3), 520–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1608842

- Karwowski, E. (2021). Commercial finance for development: A backdoor for globalization. Review of African Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2021.1912722

- Kentikelenis, A., Stubbs, T. H., & King, L. P. (2016). IMF conditionality and development policy space, 1985–2014. Review of International Political Economy, 23(4), 543–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1174953

- Langley, P. (2021). Assets and assetization in financialized capitalism. Review of International Political Economy, 28(2), 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1830828

- Leyshon, A., & Thrift, N. (2007). The capitalization of almost everything: The future of finance and capitalism. Theory, Culture, and Society, 24(7–8), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407084699

- Li, T. M. (2009). To make live or let die? Rural dispossession and the protection of surplus populations. Antipode, 41(S1), 66–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2009.00717.x

- Louch, W. (2021, November 2). BlackRock’s new climate finance vehicle draws $673 million. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-02/blackrock-says-new-climate-finance-vehicle-draws-673-million

- Mawdsley, E. (2018). Development geography II: Financialization. Progress in Human Geography, 42(2), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516678747

- Mawdsley, E., & Taggart, J. (2022). Rethinking d/Development. Progress in Human Geography (1), 3–20.

- Milberg, W. (2008). Shifting sources and uses of profits: Sustaining US financialization with global value chains. Economy and Society, 37(3), 420–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140802172706

- Moraitis, A. (2021). From the post-industrial prophecy to the de-industrial nightmare: Stagnation, the manufacturing fetish and the limits of capitalist wealth. Competition and Change. https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294211044314

- Musthaq, F. (2021). Development finance or financial accumulation for asset managers? The perils of the global shadow banking system in developing countries. New Political Economy, 26(4), 554–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1782367

- Natarajan, N., Brickell, K., & Parsons, L. (2019). Climate change adaptation and precarity across the rural-urban divide in Cambodia: Towards a ‘climate precarity’ approach. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 2(4), 899–921. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619858155

- OECD. (2018). Sector financing in the SDG era: The development dimension.

- OECD. (2021). Climate finance provided and mobilized by developed countries – aggregate trends updated with 2019 data.

- Perry, K. (2021). The new “bond-age”, climate crisis and the case for climate reparations: Unpicking the old/new colonialities of finance for development within the SDGs. Geoforum, 126, 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.09.003

- Phillips, N. (2016). Labour in global production: Reflections on coxian insights in a world of global value chains. Globalizations, 13(5), 594–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2016.1138608

- Rolnik, R. (2013). Late neoliberalism: The financialization of homeownership and housing rights. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), 1058–1066. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12062

- Sadowski, J. (2020). The internet of landlords: Digital platforms and new mechanisms of rentier capitalism. Antipode, 52(2), 562–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12595

- Schindler, S., Alami, I., & Jepson, N. (2022). Goodbye Washington Confusion, hello Wall Street Consensus: Contemporary state capitalism and the spatialisation of development strategy. New Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2022.2091534

- Schwartz, H. M. (2021). Global secular stagnation and the rise of intellectual property monopoly. Review of International Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1918745

- Selwyn, B. (2019). Poverty chains and global capitalism. Competition and Change (1), 71–97.

- Selwyn, B., & Leyden, D. (2022). Oligopoly-driven development: The world bank's trading for development in the age of global value chains in perspective. Competition and Change (2), 174–196.

- Soederberg, S. (2017). Universal access to affordable housing? Interrogating an elusive development goal. Globalizations, 14(3), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2016.1253937

- Tan, C. (2021). Audit as accountability: Technical authority and expertise in the governance of private financing for development. Social and Legal Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663921992100

- Turner, J. F. C. (1972). Freedom to build. McMillan.

- United Nations. (2015). Zero draft- Addis Ababa accord.

- United Nations. (2021). Financing for sustainable development report 2021.

- USAID. (1983). Handbook 7: Housing guarantees. Department of State.

- USAID. (2019). Mobilizing finance for development: A comprehensive introduction.

- USGAO. (1978). Report to congress by the comptroller general of the United States: Agency for international development’s housing investment guaranty program. Government Accounting Office.

- Van Waeyenberge, E. (2015). The private turn in development finance (FESSUD Working Paper Series No. 140). Financialisation, Economy, Society and Sustainable Development Project.

- Van Waeyenberge, E. (2018). Crisis? What crisis? A critical appraisal of World Bank housing policy in the wake of the global financial crisis. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(2), 288–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17745873

- Werlin, H. (1999). The slum upgrading myth. Urban Studies, 36(9), 1523–1534. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098992908

- World Bank. (1973). Appraisal of a site and services project in Senegal. World Bank Group.

- World Bank. (1975). Housing: Sector policy paper. World Bank Group.

- World Bank. (2015a). From billions to trillions: Transforming development finance.

- World Bank. (2015b). From billions to trillions: MDB contributions to financing for development.

- World Bank. (2015c). Investing in urban resilience: Protecting and promoting development in a changing world.

- World Bank. (2017). Maximizing finance for development: Leveraging the private sector for growth and development.