ABSTRACT

In an age of ‘radical uncertainty,’ state capacity proves critical for countries to contain ‘wicked crises’ and improve the resilience of societies. At the same time, authoritarian populism has come to dominate politics in several countries. The impact of populist leadership on state capacity, however, remains an under-researched theme. We explore how populist rule has impeded effective management of the COVID-19 pandemic by weakening state capacity. We compare Brazil and Turkey as cases with similar degrees of state capacity but diverging pandemic management performance. We also examine South Korea as a benchmark case combining high state capacity and effective leadership. We show that state capacity is central in managing ‘wicked crises,’ but populist leadership undermines it through a set of mechanisms. On a broader scale, we aim to contribute to the debate by exploring the interactions among crises, state capacity, and populist rule.

Introduction

We live in a period of multiple crises that have, once again, brought the concept of ‘state capacity’ to the forefront. The 2008 global financial crisis, the climate emergency, the COVID-19 pandemic, and global geopolitical turmoil highlighted the importance of effective states in tackling unanticipated shocks surpassing national borders. The complex nature of the ongoing global power shifts added further instability and uncertainty, creating a delicate political-economic equilibrium that renders the current international order ‘unlikely to persist in its present form’ (Rodrik & Walt, Citation2021, p. 1). As Kay and King (Citation2020) put it, ‘radical uncertainty’ emerges as the defining aspect of the global political economy. All these developments bring state capacity and national resilience to the forefront. In this context, much effort has gone into studying state capacity in relation to various areas in contemporary global politics, such as climate change (Meckling & Nahm, Citation2018), security (Hendrix, Citation2010), and migration (Micinski & Bourbeau, Citation2023).

COVID-19 has not been immune to these discussions. This article focuses on COVID-19 as a critical case that reveals the central importance of state capacity in an age of ‘radical uncertainty.’ COVID-19 belongs in the category of what scholars refer to as ‘wicked crises’ in that it is ‘transboundary, unique, and characterized by a high degree of uncertainty’ and is hence ‘the most demanding because [it] transcend[s] administrative levels, sectors and ministerial areas’ (Christensen et al., Citation2016, p. 888). The pandemic led to an extensive discussion among political scientists on those attributes of states that make them better positioned in containing the crisis, reducing insecurities, and improving the resilience of societies.

A large volume of political science literature emerged on the governance of COVID-19 as the pandemic raised certain interesting puzzles. For example, while some democracies have fared relatively well in tackling COVID-19, others lagged considerably behind. Also, while some authoritarian states are often cited among the successful cases in fighting COVID-19, others are considered to have failed (Brown et al., Citation2020). This has led some observers to call for a focus on the ‘specific strengths and weaknesses of different forms of government’ instead of attempting to generalize based on regime type, with an emphasis on the capacity that states possess (Stasavage, Citation2020). The early published studies on the management of the pandemic in select country cases have underlined the significance of state capacity and the presence/absence of a legitimate political system capable of cultivating public trust in tackling the pandemic (Capano et al., Citation2020; Christensen et al., Citation2016; Hartley & Jarvis, Citation2020; Kleinfeld, Citation2020; Moisio, Citation2020; Weiss & Thurbon, Citation2022). Several large-N studies also suggest that certain features of state capacity, such as government effectiveness, are linked with lower mortality rates from COVID-19 (Bosancianu et al., Citation2020, p. 39; Serikbayeva et al., Citation2021).

The role of political agency should not be underestimated either. The COVID-19 pandemic emerged at a time when populist authoritarian leaders have already become key political actors in many developed and developing countries. COVID-19 provided yet another opportunity for those leaders to ‘capitalize on the fears of the people through the discourse of ‘managing’ and ‘containing’ ‘risks’ in society’ (Aydın-Düzgit & Keyman, Citation2020, p. 3; on populist rule also see Moffitt, Citation2015; Pappas & Kriesi, Citation2015). Hence, the COVID-19 pandemic constituted a critical test for populist leadership. Despite rapidly growing social sciences literature on the subject matter documenting the poor performance of populist leaders in managing the COVID-19 pandemic (for example, see Mudde, Citation2020; Kavaklı, Citation2020, p. 17; McKee et al., Citation2021, p. 511; Kapucu & Moynihan, Citation2021), the ways in which state capacity and populist leadership interact in crisis management still needs in-depth analysis. In this paper, we argue that populist leaders are likely to undermine state capacity due to extensive institutional erosion under their rule. Based on a comparative method, we determine three key characteristics of populist rule – that is, disregard of scientific expertise; a push for centralization; and measures to reduce accountability – have undermined these countries’ crisis management capabilities precisely by weakening state capacity, conceptualized as the ability of the state to achieve extraction, coordination, and compliance (capacity for). We also show that state capacity is weakened as these features of populist rule target the resources upon which it is built and deployed (capacity through). In doing so, we aim to bring the ongoing but largely separate debates on state capacity and the populists’ response to the COVID-19 crisis together to demonstrate that the professed ‘strong leadership’ by populist leaders does not necessarily lead to strong capacity in articulating an effective response.Footnote1

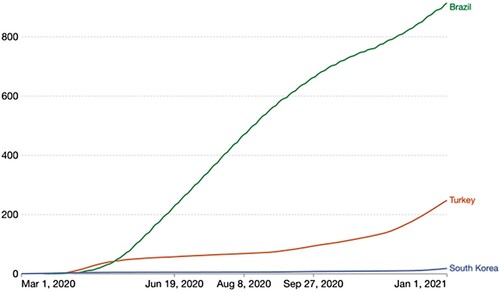

We maintain that our findings extend beyond the challenges posed by COVID-19. In the post-pandemic era, state capacity is likely to play a central role in developing successful responses to unprecedented global challenges, but populist governments are likely to undermine state capacity at a time when it is required most. We substantiate our argument through an analysis of how the COVID-19 crisis was handled in three late developing countries – South Korea, Brazil, and Turkey. We focus on the initial phase of the pandemic, during which Brazil experienced the highest cumulative confirmed deaths per million people, whereas South Korea emerged as a highly successful case. Turkey, on the other hand, remained in between as a case of moderate performer (). The variation in select cases enables us to demonstrate how different modes of interaction between state capacity and populist leadership (or lack thereof) lead to divergent outcomes.

Figure 1. Cumulative confirmed COVID-19 deaths (per million people). Source: Our World in Data figure, based on Johns Hopkins University CSSE COVID-19 Data.

A caveat is in order at this point. Although these numbers give a clear idea about significant divergence among the three cases, they should still be approached with caution due to two factors. One relates to the problem of substantial underreporting (Do Prado et al., Citation2020; Turkish Medical Association, Citation2020). The second factor relates to how attributes such as a country's demography and the structure of its health system were shown to have an impact on death figures, especially in the initial months of the pandemic (Balta & Özel, Citation2020; Kayaalp & İbrahim, Citation2020). Hence, we believe that an exclusive focus on the numbers, be it confirmed cases or mortality rates, runs the risk of leading to distorted views on the dynamics behind governments’ relative success or failure in fighting the pandemic.

To mitigate this caveat, we unpack the responses in country cases and demonstrate the observable implications of state capacity and the impact of the populist rule on managing the pandemic in Brazil and Turkey, compared with South Korea as a benchmark. We use process tracing in this paper, as this method ‘gives us a better understanding of how a cause produces an outcome’ (Beach, Citation2016, p. 463; also see Bengtsson & Ruonavaara, Citation2017; Bennett & Checkel, Citation2015). We show how policies adopted by the populist leaders in Brazil and Turkey in the early phases of the pandemic have resulted in poor management of the crisis by undermining the material and nonmaterial sources of state capacity. We also trace South Korea's pandemic response as a benchmark that approximates an ideal type, demonstrating how high state capacity and non-populist leadership result in effective management under uncertain conditions. The data for the analysis come from newspapers and reports retrieved from EMIS (Emerging Market Information Sources) and Lexis Nexis between 1 February and 31 December 2020. Press releases and reports by national and international public and private organizations were also included in the analysis. COVID-19 data was retrieved from Our World in Data, and government measures to counter COVID-19 were traced through the Coronavirus Government Response Tracker at the University of Oxford.

In what follows, we first engage in a conceptual discussion of crisis and state capacity, with a focus on identifying those elements of state capacity that matter the most in fighting a pandemic of the size and nature of COVID-19. We then discuss our conceptualization of populism, also with reference to the key defining features of populist rule in relation to state capacity, and turn to the empirical analysis of three cases, where we trace how these features have played out and thus resulted in considerable divergence in terms of management of the pandemic in the crucial early months of the crisis. We conclude with a discussion of our findings and implications for future research.

Crisis, state capacity, and populism: the need for conceptual clarity

Rosenthal et al. (Citation1989, p. 10) define a crisis as ‘a situation in which there is a perceived threat against the core values or life-sustaining functions of a social system that requires urgent remedial action in uncertain circumstances.’ This definition is particularly apt for COVID-19 as the pandemic constitutes severe social, political, and economic threats to states and requires urgent action due to its extremely contagious and unpredictable nature. Successful management of such crises requires a strong state capacity with a focus on coordination and high degrees of public trust and legitimacy (Christensen & Lægreid, Citation2020; Christensen et al., Citation2016).

State capacity, however, remains a contested concept. Depending on the area of inquiry, it can be studied as a ‘dependent variable’ or ‘independent variable,’ and it can cover several activities, ranging from coercion to extraction (de la Cruz et al., Citation2022, p. 131). Also, state capacity has different but interconnected dimensions. Bakır (Citation2015, pp. 69–71) distinguishes between ‘administrative’ and ‘institutional capacity’ and demonstrates how they are interrelated as key dimensions of state capacity.

In the simplest definition, state capacity is ‘the ability of state institutions to effectively implement official goals’ (Sikkink, Citation1991) or ‘a government's ability to make and enforce rules, and to deliver services’ (Fukuyama, Citation2013, p. 352). In more specific terms, Berwick and Fottini (Citation2018) analyse state capacity by distinguishing between ‘capacity for’ and ‘capacity through.’ Accordingly, ‘capacity for’ refers to three key activities for which states need to develop capacity, namely extraction, which relates to a state's ability to secure revenues, coordination which refers to the ‘capabilities of state agents to organize collective action’, and compliance which means ‘the ability of state leaders to secure compliance with their goals’ (Berwick & Fottini, Citation2018, p. 76 and 78–79). States also need resources to develop the necessary capacity to achieve these goals, which brings us to the notion of ‘capacity through.’ We treat ‘resources’ broadly, including material and non-material instruments the state needs to possess and effectively deploy to realize these goals. These resources include revenues of the state, reliable information, and a competent administration capable of extracting revenues and ensuring effective coordination and compliance (see also Lindvall & Teorell, Citation2016).

The political economy literature demonstrates that a competent bureaucracy is instrumental in ensuring extraction, coordination, and compliance by addressing collective action problems, facilitating high-quality information flows with non-state institutional actors, and pursuing long-term goals (Evans, Citation1995; Öniş, Citation1991). However, a well-functioning central administration is not a sufficient resource, where ‘local discretion’ is also warranted in today's uncertain world marred by wicked crises (Berwick & Fottini, Citation2018, p. 84; Acemoğlu et al., Citation2015). Effective vertical coordination between central and local authorities becomes essential in crisis situations, given that local institutional actors are more often ‘faced with practical challenges or the operational side of a crisis’ (Christensen et al., Citation2016, p. 892). Also, non-state institutional actors are considered ‘sources of expertise and coordination,’ with which the state should work to enhance its coordination capacity (Berwick & Fottini, Citation2018, p. 79). Compliance, on the other hand, is incurred at two levels: first, within the state, with public sector agents complying with political leaders’ goals; second, between the state and the mass public, where the public complies with the directives of the state (Berwick & Fottini, Citation2018, pp. 79–80).

Defined as such, the relational nature of coordination and compliance becomes clear. Both aspects of state capacity relate to what Mann (Citation1984, p. 189) has referred to as the state's ‘infrastructural power,’ meaning the ability to ‘penetrate civil society, and to implement logistically political decisions throughout the realm.’ State power does not only emanate from the policies of governments but is also embedded in the state's relationship with society at large. This requires a more encompassing societal analysis of state capacity, which Migdal (Citation1994) calls ‘the state in society’ perspective. Accordingly, the ‘mutually empowering’ nature of the state-society nexus constitutes the main source of state capacity, which requires researchers to ‘eschew a state-versus-society perspective that rests on a view of power as a zero-sum conflict between the state and society’ (Migdal et al., Citation1994, p. 4). We will demonstrate below that it is also this societal core of state capacity that populist leaders undermine. For the state-society synergy to work effectively, legitimacy and inclusive governance play a key role as they facilitate compliance whereby successful delivery by the governments may bolster its legitimacy across society, also referred to as output legitimacy (Scharpf, Citation1999). The level of public trust, in turn, determines the extent to which citizens will cooperate with governments in achieving collective goals (Christensen et al., Citation2016, p. 889) .

Table 1. Conceptualizing State Capacity in COVID-19.

The case of COVID-19 illustrates that for successful management of the crisis, all three capacities outlined above need to be rapidly mobilized where, in addition to financial resources, states need to rely heavily on well-coordinated local responses, a properly functioning public health system, scientific expertise, transparent information flow, and public trust (Capano et al., Citation2020; Greer et al., Citation2020; Kavanagh & Singh, Citation2020; Moisio, Citation2020). A health crisis at the scale of COVID-19 is a ‘complex intergovernmental problem’ which demands strong intergovernmental coordination (Paquet & Schertzer, Citation2020). Given that social distancing and mask-wearing have proven effective in reducing the transmission rate of COVID-19, voluntary compliance of the public with these and other related measures is also considered essential (Moon, Citation2020). Nonetheless, public compliance requires transparent, reliable, and up-to-date information flow from state to citizens on issues such as the rates of transmission and the geographic distribution of cases, as well as evidence-based justifications of government responses (Sharma et al., Citation2020, p. 13). Furthermore, the government should be able to count on public trust in its measures and demands from the citizens (OECD, Citation2020).

The literature demonstrates the role of state capacity and state-society coordination in tackling complex crises like COVID-19 (Mao, Citation2021; Serikbayeva et al., Citation2021; Siedlok et al., Citation2021). However, what is often overlooked is that political agency plays a central role in conditioning how state capacity translates into actual policy outcomes. The performance of states may diverge considerably in the face of ‘wicked crises’ despite possessing a similar degree of state capacity. Addressing this gap is important, especially given the quasi-consensus that we are now living in a populist era that drives global politics. We will demonstrate that certain features of populist rule weakened state capacity at a time when it was most needed during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before showing how that has happened, we first clarify our conceptualization of populism and its relationship to state capacity.

Populism in power and state capacity

Populism is an essentially contested concept. It can be theorized as ‘an ideology which considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté général (general will) of the people’ (Mudde, Citation2004, p. 542). This ideational approach, however, rests on a minimal definition of populism, which downplays the role of political agency and the governance style of populist parties and leaders. Those approaches which conceptualize populism as a political strategy bring personalistic populist leadership, hence political agency, into the picture (Weyland, Citation2017) yet say very little about how that leadership is enacted (Baykan, Citation2018, p. 75). Discourse-theoretical approaches to populism underscore the primacy of discourse in the articulation of the ‘people’ (Laclau, Citation2005) but largely leave the extra-linguistic practices of populist leaders and parties out of focus. Hence, all these three main approaches to populism – as an ideology, political strategy, and discourse – by not paying due attention to political agency and governance that are both central to our conceptualization of state capacity above, fall short of assisting us in understanding the ways in which populist rule impacts on state capacity.

Understanding the relationship between populism and state capacity requires a theorization of the former, where political leadership coupled with the style of governance is at the centre of analysis. This is where we turn to those approaches to populism, which conceptualize it as a ‘political style’ (Moffitt, Citation2016; Ostiguy, Citation2009, Citation2017). These accounts underscore the centrality of personalistic leadership in populism but also zoom in on the specific ways in which populist leaders govern to secure the allegiances of their supporters. Ostiguy's (Citation2017) conceptualization of populism through the ‘high-low axis’ becomes particularly useful here. The high-low axis relates to the ‘ways of ‘being’ and ‘acting’ in politics’, with two major components: the socio-cultural component, which relates to political actors’ manners, language, and demeanours; and the political-cultural component, which refers to their ‘form of political leadership and preferred modes of decision-making in the polity’ (Ostiguy, Citation2017, pp. 78–85). It is the latter component that directly relates to how political actors choose to govern the polity, thus bearing implications for state capacity.

Approaching populism as a style entails a normatively neutral position (Ostiguy, Citation2017, p. 74), whereby one may argue that the informal practices fostered by this political style may, in fact, facilitate faster responses in crisis situations. Yet, public policy scholars have argued otherwise that a populist regime would limit its state capacity mainly by disregarding expertise, pushing for centralization of power, and reducing accountability through polarization (Bauer & Becker, Citation2020; Peters & Pierre, Citation2019, Citation2020). These aspects relate directly to the political-cultural component of the high-low axis associated with a populist style of governance. At the core of populism lies the ‘flaunting of the low’, whereby the ‘low’ in the political-cultural component implies ‘very personalistic, strong (often male) leadership’ and ‘preference for decisive action often at the expense of some ‘formalities’’ (Ostiguy, Citation2017, p. 76, 84, 85). As such, ‘populist personalized leadership, as a form of rapport, of representation, and of problem-solving’ becomes ‘a way to shorten the distance between the legitimate authority and the people’ (Ostiguy, Citation2017, p. 84). In crisis situations, this translates into a denial of expert knowledge, an exclusive focus on personalized leadership at the expense of negotiation and deliberation with relevant stakeholders, and the portrayal of competing political actors as largely incompetent (Moffitt, Citation2016). Hence, in overlap with the characteristics of populist rule associated with state capacity, conceptual approaches to populism as a ‘political style’ also point to a form of populist governance where expert knowledge is largely denied (disregarding of expertise); power is centralized in the leader at the expense of bureaucracy, civil society and other relevant stakeholders (pushing for centralization of power); and constraints on the powers of the personalistic leader are minimized (reducing accountability), allowing us to observe whether populism as a political style, in fact, has a negative impact on state capacity in crisis situations. We claim all three aspects of the populist rule bring about institutional erosion and undermine state-society ties at large, which, in turn, weaken state capacity.

The first aspect, disregarding expertise takes the form of ‘sidelining’ and ‘ignore(ing) the policy advice’ of the bureaucracy and relevant experts (Peters & Pierre, Citation2019, p. 1529). As polarization is utilized as a governing strategy by populist leaders to divide societies along partisan/ideological lines, they weaken social cohesion and public trust (Carothers & O’Donohue, Citation2019). In a polarized political context, excessive politicization of the administration, where loyalty trumps expertise in appointments and policy choices (Peters & Pierre, Citation2019, pp. 1527–1528), further inhibits state capacity.

The second aspect, centralization of power, manifests itself in expanding the policy discretion of the executive as well as centralizing resources (Bauer & Becker, Citation2020, p. 20). The accumulation of power in the hands of populist leaders, which is justified on the ground of effective decision-making, in fact, leads to the weakening of state capacity as it dents institutional infrastructure to enable high-quality information flows, overcome collective action problems, and implement policies through effective state-society cooperation.

The final aspect, reducing accountability, relates to populist leaders’ aversion to checks and balances at three levels: horizontal, vertical, and diagonal (Lührmann et al., Citation2020). While vertical accountability relates to the relationship between governments and citizens and thus pertains more to electoral politics, horizontal accountability concerns the checks on the executive by the different branches of government, including judicial oversight, and diagonal accountability entails the control exerted on governments by those actors that are outside formal institutions, most notably independent media, and civil society (Lührmann et al., Citation2020, p. 813). When populists take steps to reduce accountability, these can take various forms, such as curbing judicial independence, suppressing civil society organizations that are critical of their rule, and limiting the freedom of the press (Müller, Citation2016, pp. 44–75) – all of which lead to poor governance in the face of complicated crises.

The logic of case selection: South Korea, Brazil, and Turkey

We examine three cases to trace the process of how state capacity and populist leadership interacted with one another in the most acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. We compare South Korea, Brazil, and Turkey. South Korea approximates an ‘ideal type’ in our comparative design, as the country emerged as a ‘success story’ (Kim, Citation2021) thanks to high state capacity and effective non-populist leadership during the pandemic. With a significantly low number of cases and fewer than 1,000 cumulative confirmed deaths by the end of 2020, South Korea kept the humanitarian and economic fallout of the pandemic as low as it could be during the most acute phase of the crisis. It, therefore, constitutes a useful benchmark for a comparative assessment of Brazil and Turkey .

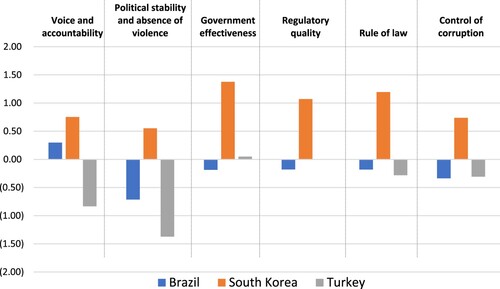

Figure 2. Main Governance Indicators – Brazil, South Korea, Turkey. Source: World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators. Each parameter takes a value between +2.5 (highest) and −2.5 (lowest). Figures belong to 2020.

We also examine Brazil and Turkey as similar cases concerning state capacity. Brazil and Turkey, however, demonstrated considerable differences in terms of overall COVID-19 performance in the first year of the pandemic (see ). This, we suggest, demonstrates the role of political agency and the variety of populist leadership in times of severe crisis. It is true that both countries were governed by right-wing authoritarian populist leaders in the most acute phase of the pandemic. Jair Bolsonaro came to power in Brazil in January 2019 from the fringes of Brazilian politics and has widely been referred to as a ‘radical right’ or ‘far right’ populist leader in both the socio-cultural and political-cultural conceptualisations of populism as a political style, thanks to his anti-establishment and politically incorrect demeanour and discourse, his polarizing rhetoric and governance pitting him in an eternal struggle as the voice of the ‘people’ against their enemies, and his exclusive policies towards state institutions and society at large (Casarões & Leal Farias, Citation2022; Farias et al., Citation2022; Guimaraes & de Oliveira e Silva, Citation2021; Louault, Citation2022; Mignozetti & Spektor, Citation2019).

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who, after coming to power with a single-party government under the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2002, first took substantial steps towards democratic consolidation in Turkey, only to turn toward increasingly populist and divisive rhetoric and politics, as the party's dominance has grown since the early 2010s. Like Bolsonaro, Erdoğan's leadership is also widely considered as right-wing populist in style, with a strong ‘low-populist’ appeal as the representative of the ordinary masses embodied in a highly personalistic leadership against domestic and foreign elites/conspirators, along with a polarizing and hyper-centralized form of governance at the expense of democratic deliberation and inclusive rule (Baykan, Citation2018). However, when it comes to narrating the pandemic and managing COVID-19, the style of populist leadership diverged to a certain extent, leading to different paths through which state capacity was mobilized in Brazil and Turkey (see ).

Table 2. The Logic of Case Selection.

We use process tracing in the following sections, where we identify the sequences of events that have resulted primarily from populist leaders’ specific actions that are conceptualized above as characteristic of populist rule. We found that disregarding expertise, centralization of power, and reducing accountability under populist leadership hampered the state's capacity to govern, which is conceptualized as the power to extract, coordinate, and ensure compliance.

South Korea: high state capacity meets effective leadership

South Korea represents one of the exemplary cases among late developing countries achieving significant development. As an agricultural-based, low-income country in the 1950s, South Korea has been transformed into a technological powerhouse in the twenty-first century. South Korea also improved national public health infrastructure parallel to its economic development, and, currently, ‘the number of hospital beds per capita, 12.3 beds per 1,000 population, is two times higher than the average in Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries’ (Kim, Citation2021). Extensive literature has documented the fundamental role of state capacity and government intervention in South Korea's successful economic transformation by extracting and distributing resources, coordinating bureaucratic institutions, and establishing cooperation mechanisms with non-state institutional actors (Amsden, Citation1989; Evans, Citation1995; Öniş, Citation1991).

State capacity and effective leadership enabled South Korea to develop a comprehensive COVID-19 strategy. South Korea recorded its first COVID-19 cases in January 2020, earlier than most other countries in the world. The country adopted a ‘whole-of-government’ approach (Government of the Republic of Korea, Citation2020) with ‘agile, adaptive, and transparent actions by the South Korean government, as well as evidence-based policy decisions and collaborative governance’ (Moon, Citation2020, p. 653). The combination of the extractive, coordination, and compliance capacities of the state, as well as the voluntary compliance of citizens guided by effective leadership, helped South Korea to keep the total number of cases and deaths significantly low (see ).

The political leadership in South Korea has relied on scientific expertise since the early days of the pandemic. The government followed the lead of the medical community and health experts when it came to policy development and implementation (Moon et al., Citation2021: 657). A close partnership between bureaucratic authorities and scientific communities avoided over politicization of the pandemic and enabled high-level intergovernmental coordination, with the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) taking the central stage as an autonomous agency (Moon et al., Citation2021, p. 657). The South Korean government also adopted an aggressive ‘test-trace-isolate system’ (Chekar et al., Citation2021) with the help of a strong technological infrastructure (Government of the Republic of Korea, Citation2020). As a result, the country managed to test ‘about 10,000 people per million’ as of April 18, 2020 – a number significantly higher than other well-resourced countries – along with additional innovative techniques such as establishing ‘drive-through and walk-through testing stations’ to reduce the spread of the virus (Moon, Citation2020, p. 653).

In addition, close coordination mechanisms were established between the health bureaucracy, local authorities, and non-state actors to implement consistent testing, tracing, and treatment procedures (labelled as ‘3 T strategy’). The government coordinated with private firms in the early stages to produce testing kits, develop software apps, and use mobile GPS data in order to trace infected patients and regularly update the public about the geographical spread of the virus (Government of the Republic of Korea, Citation2020, pp. 35–62). The swift response of the government in adopting appropriate countermeasures along with a transparent communication strategy proved instrumental in convincing citizens to follow social distancing and other COVID-19-related rules.

South Korea's capacity to use digital technology was complemented by strong coordination at the local level. The municipalities and district representatives attended the central government's daily COVID-19 meetings, which ‘ensured that all city and district governments were aware of decisions and actions being carried out on the national level and that they could inform policymaking at the central level by directly communicating their local needs and priorities’ (Dyer, Citation2021, p. 15). For each citizen contracting virus and self-isolating, local councils assigned a case officer, who remained in contact with infected people during quarantine. In this period, case officers provided ‘food, drink, bin liners, a thermometer for monitoring their condition, and face masks and hand sanitiser to help prevent further infection’ (Chekar et al., Citation2021). Financial and mental support were also provided to the people in self-isolation to assist them in complying with the restrictions.

The effective state support and coordination were complemented by strong compliance of citizens as the South Korean state exercised a high capacity to penetrate society and ensure compliance at the state-society nexus. To this end, the government pursued a transparent strategy for communicating with citizens. Transparency in releasing COVID-19-related data on a regular basis and explaining the next steps to citizens in a clear way helped the government gain much-needed public trust in the middle of an unprecedented pandemic. For instance, Moon et al. (Citation2021, p. 654) cite a national survey pointing out that ‘a majority (74.4%) of citizens were satisfied with the transparent communication and agile response to the problem.’ Other studies also confirm these findings (Mao, Citation2021, p. 326), suggesting that thanks to vertical and horizontal cooperation in administration and credible and transparent information flows, public trust in government remained high during the pandemic, which, in turn, provided a shield against fake news, polarization, mass anxiety and panic among citizens.

Overall, South Korea has managed the COVID-19 crisis effectively, which is approximated to an ‘ideal type’, with high state capacity in relevant realms combined with responsible leadership prioritizing scientific expertise and public trust. As a result, South Korea managed to weather the pandemic storm without having to impose full lockdowns or economic shutdowns, even in the most acute phase of the crisis.

Brazil: science wars meet intergovernmental confrontation

Disregarding expertise and the push for centralization of power were the two populist hallmarks of Brazil's early reactions to COVID-19. When COVID-19 first hit Brazil in late January, it was met with denial based on an anti-science discourse by President Bolsonaro. Bolsonaro's anti-science standing predates the pandemic and pervades various government policies. For instance, even before the pandemic, the Minister of Education under the Bolsonaro government has frequently attacked universities and the scientific community for serving as ‘ideological factories’ which raise ‘leftist and communist militants’ (Monteiro, Citation2020, p. 5). The government's anti-science stance was also clearly visible in its responses to the forest fires in the Amazon when it encouraged illegal loggers and dismissed the president of the National Institute for Space Research for his criticisms of government policies (Monteiro, Citation2020, p. 5).

Hence, it did not come as a great surprise when Bolsonaro initially dismissed COVID-19 as a ‘little flu’ and continued to downplay it even after he allegedly tested positive for the virus by encouraging masses to join his rallies, shaking hands and not wearing a mask (France 24 Citation2020b). This was also in alignment with his well-polished masculine image of a strongman. Bolsonaro's Foreign Minister framed COVID-19 and the World Health Organization as part of a global conspiracy with the goal of Chinese domination at its core (Zilla, Citation2020). The anti-science rhetoric quickly translated into policies where scientific expertise was not only explicitly disregarded but also punished. In April 2020, Bolsonaro removed from office his first health minister, who disagreed with him on social distancing measures and expressed his reservations about the use of the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine. When his successor, who also defended quarantine measures, resigned in May, Bolsonaro replaced him with an army general who did not have prior experience in public health matters (BBC News, Citation2020a).

Disregard of expertise resulted in a situation where, despite scientific advice to the contrary, the central government did not implement any centrally coordinated lockdowns or curfews in the country. Except for temporary travel and border restrictions, the main measures taken by the central government remained limited to those designed to cope with the pandemic's economic impacts, such as financial assistance for businesses and limited social aid programmes (Urban & Saad-Diniz, Citation2020). Bolsonaro went as far as declaring that ‘deaths are a fact of life and should not stand in the way of restoring the economy’ (Spektor, Citation2020), urging people to return to work even when deaths were spiking (Londono et al., Citation2020). Hence, whichever capacity the state initially possessed in the way of coordination and compliance to fight the pandemic was not mobilized. The state was left ‘incapacitated’, where the government ‘withheld some of the tools or resources that contribute to state capacity’ (Levinson, Citation2014, p. 197) in managing the pandemic. As a result, the country missed what is often referred to by epidemiologists as the ‘golden time’ for the necessary containment measures, including epidemiological survey-based mitigation (Moon, Citation2020, p. 653), and despite enjoying the advantage of encountering COVID-19 later than most other countries, quickly rose to the top in the number of cases and deaths with the highest rate of transmission in the world (The Lancet, Citation2020). Furthermore, the anti-science messages at the top found resonance across a certain segment of the public and hampered public compliance with the necessary measures by leading to mass public demonstrations against social distancing and other sanitary measures such as mask-wearing when the pandemic was at its peak (Granada, Citation2020, p. 2).

If disregard for expertise was one feature of populist governance that incapacitated the Brazilian state in the face of COVID-19, the push for the centralization of power was the one that weakened the capacity that the state possessed and accelerated de-institutionalization, particularly in the way of coordination. After the pandemic hit Brazil, vertical relations between the centre and the local level (federal states and municipalities) were defined by confrontation rather than cooperation and coordination. Bolsonaro's drive for further centralization and exclusion of sub-national entities from decision-making was well-known even before he came to power when he made the call for ‘More Brazil, less Brasilia’ in his election campaign. This policy was reflected in his pandemic politics, with grave consequences for public health. During the pandemic, the president of the National Council of State Secretaries of Health was excluded from participating in the decisions of the Ministry of Health, while the COVID-19 Crisis Committee, which was eventually established, had no state or municipal representatives (Abrucio et al., Citation2020, pp. 671–672). After state and municipal officials started taking initiatives for local lockdown measures in late January, they were met with harsh reactions from the central administration. It was revealed that in a cabinet meeting on 22 April, Bolsonaro expressed that he ‘wanted to arm the entire populace to defend themselves against dictatorship’ – meaning the governors (Zilla, Citation2020, p. 4). Meanwhile, federal prosecutors launched various investigations into local pandemic responses. These investigations, which mainly took the form of corruption probes, were then used by the president to shift the blame and responsibility for the worsening state of the pandemic to the local officials who stood politically opposed to the central government (Pedroso et al., Citation2020).

These attacks from the political centre extended beyond the local institutions to the institutions of the central state, such as the Supreme Court, which ultimately allowed the local governments to take health protection measures at their own discretion (Zilla, Citation2020, p. 4). There was also a constant tug of war over information between the centre and the local governments, with the Ministry of Health regularly accusing the states of distorting the number of deaths while at the same time trying to conceal information from the general public by reducing the frequency with which citizens were informed on the number of cases and deaths (Abrucio et al., Citation2020, p. 673) and by ceasing to report the cumulative totals and cases in May, which was later overturned by the Supreme Court (BBC News, Citation2020b).

The lack of coordination between the central and the local levels, driven by the insistence on the centralization of power, had heavy consequences. For instance, Rio experienced an ill-timed opening partly due to the incorrect data supplied by the centre showing a decline in cases in the city. It was later found that the reported low numbers were related to the central bureaucratic delays in communications to local officials, leading ultimately to the local decision to ease restrictions while the number of cases in the city was still very high (Fonseca & Gaier, Citation2020). It also had significant repercussions on the use of financial resources, as the local administrators announced that they were not getting the resources in the early phase of the pandemic (Abrucio et al., Citation2020, p. 671). It took until the end of May for the central government to organize the federal distribution of financial resources, mainly due to its insistence on changing the Constitution to establish a ‘war budget’ instead of dispensing funds through federative forums where officials from the centre and the federal states would normally get together (Abrucio et al., Citation2020, p. 671). Furthermore, the lack of central coordination resulted in intergovernmental conflict between federal states as, in the case of the Consortium of the Northeast and states such as Sao Paulo and Maranhão, which ‘took decisions that produced horizontal and vertical competition for scarce supplies in the fight against COVID-19″ (Abrucio et al., Citation2020, p. 672). This also led to a rise in the reported number of corruption cases related to the purchase of scarce health resources precisely because an organized federal response was largely absent in central coordination of the much-needed and limited resources at the local level (France 24, Citation2020a).

Overall, the case of Brazil shows how key elements of populist governance, particularly the disregard for expertise and the push for centralized exclusionary governance, have weakened the coordination and compliance capacity of the Brazilian state in its encounter with the pandemic. This resulted in ill-timed openings and mismanagement of much-needed financial and sanitary resources.

Turkey: populist governance under authoritarianism

As two notable late developers, Brazil and Turkey have similar degrees of state capacity in broader terms. However, compared to Brazil, Turkey acted relatively early and adopted at the onset of the pandemic a mix of policy instruments such as curfews, travel restrictions, and quarantines, along with daily public briefings on the necessary sanitary measures and the state of the pandemic in the country. Turkey even enjoyed a brief period of national consensus and unity at the beginning of the pandemic. Erdoğan empowered the minister of health, Fahrettin Koca, a doctor and technocratic figure with extensive cross-party support (Aydın-Düzgit, Citation2020). A scientific advisory board of doctors and epidemiologists was established in January to advise the government. The opposition parties also refrained from criticizing the government in the early phases. However, this initial wave of elite cooperation soon evaporated, and certain features of populist governance took centre stage in derailing the management of the crisis.

The government's attempt to centralize pandemic management led to coordination problems with municipalities controlled by the Republican People's Party, the main opposition party in Turkey. In the March 2019 elections, the opposition bloc won Turkey's three largest cities (Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir), which were critical for the government to sustain patronage networks at the local level. During the pandemic, the mayors of Istanbul and Ankara tried to launch donation campaigns in their cities. The central government reacted harshly by suspending ‘these fundraising initiatives, started its own national campaign, and opened criminal investigations into these local efforts’ (Aydın-Düzgit, Citation2020). The government used various administrative measures to avoid opposition from reaching out to citizens, even in small cities where the support of the local authorities proved critical for poorer segments of society. Also, the government did not inform the local authorities beforehand when they declared a weekend lockdown in April 2020. The announcement was last-minute, typically reflecting the centralized ‘top-down’ populist decision-making without proper institutional consultation and coordination. The outcome was total chaos, leaving local authorities and healthcare workers unprepared (Aydın-Düzgit, Citation2020). Hence, the central government hampered both the extraction capacity of the state by suspending any local means to raise funds, the coordination of the delivery of critical services to the local communities, and the compliance of citizens through transparent and effective communication (Fox, Citation2020).

In the Turkish case, centralization entailed not only the exclusion of oppositional local officials but also relevant professional organizations from policymaking and implementation, resulting in a lack of coordination and major policy failures (Aydın-Düzgit et al., Citation2021). For example, the government promised the free delivery of surgical masks to all citizens. However, the policy utterly failed due to the exclusion of the local and non-state actors, such as municipalities or pharmacists’ associations, which could have made effective delivery possible (Bakır, Citation2020, p. 432). Instead, the government chose the Turkish Postal Service of 14,000 delivery workers to deliver the masks to 25 million households, and even though Postal Service officials were cognizant of the impossibility of the task, ‘in line with the presidential bureaucracy, they positioned themselves as loyal, obedient and committed actors whose primary role was to implement presidential decisions’ (Bakır, Citation2020, p. 432).

However, the government's policies did not accompany an outright anti-science stance as seen in Brazil but mostly came in the form of disregarding the advice of experts when the recommendations did not suit its priorities. One case in point was the decision to normalize on 1 June, which was taken by the central authority due mostly to economic concerns. A more gradual normalization process was advised by several relevant stakeholders, such as the Turkish Medical Association (Citation2020), certain economists researching COVID-19 (Çakmaklı et al., Citation2020), and even some members of the government's scientific advisory board (Kayaalp & İbrahim, Citation2020). Yet, none of those concerns were addressed by the government, resulting in ‘lowered compliance with the social distancing measures, ultimately leading to higher number of official cases and deaths during the summer than in most European states’ (Aydın-Düzgit et al., Citation2021, p. 13; also see Turkish Medical Association, Citation2020).

Pandemic management in Turkey also entailed various attempts to curb, in particular, the diagonal accountability of the executive in the context of a polarizing discourse where those in the opposition who were critical of the government's policies faced punishment. As even the officially confirmed numbers began to spike in early September, the government's clampdown extended to the Medical Association, which started the campaign: ‘You Are Not Governing! We Are Dying!’ to draw attention to the rapid rise in cases and the increasing fragility of the Turkish health system. The leader of the ultra-nationalist Nationalist Action Party (MHP), the AKP's junior coalition partner, called in mid-September for the banning of the Turkish Medical Association and prosecution of its top executives (Deutsche Welle Turkish, Citation2020). Scientific research on COVID-19 was also made subject to the mandatory permission of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry established a commission under its supervision to oversee COVID-19-related research (Bilim Akademisi, Citation2020; also see Bayram et al., Citation2020).

High levels of public mistrust in the government and state institutions predate the pandemic, thanks to the government's polarizing rhetoric and policies. Yet, such attacks on accountability in the management of COVID-19 have further eroded public trust in the government and damaged compliance with the necessary measures. According to an opinion poll, those who do not trust the official COVID-19 figures provided by the government increased from 30 per cent to almost 59 per cent between April and August 2020 (Euronews, Citation2020). As the real extent of the crisis has largely been hidden from public sight since June, individual compliance with the necessary measures considerably relaxed during the summer and into fall, where social distancing rules were violated in personal interactions as well as through communal gatherings such as weddings (Elbek, Citation2020).Footnote2

Polarization not only hampered the coordination but also the extraction capacity of the Turkish state. Due to stagnation in the Turkish economy, Erdoğan attempted to create new resources by launching a national donation campaign for COVID-19, which divided the nation between those who saw this as a national effort that required unity and others as a sign of weakness on the part of government that could not be trusted with the money. It was found that by May, only 23 percent of the citizens stated that they contributed to the campaign (Gazete Duvar, Citation2020) where the bulk of the $300 million raised by the end of June came from businesses that relied on government contracts (Aksoy, Citation2020, p. 2).

Overall, Turkey's response to the pandemic embodied features of populist governance, which undermined overall state capacity. However, the populist nature of the government in Turkey was not as intense as was the case in Brazil regarding the management of COVID-19.

Conclusion

Uncertainty defines the political-economic landscape in the contemporary international order. The massive ambiguity, frequent crises, and growing difficulty in predicting how the future might unfold make state capacity indispensable to improve the resilience of societies in the face of ‘wicked crises.’ Paradoxically, however, the current global environment is also associated with the rise of populist leadership, which is likely to undermine state capacity through institutional erosion. This article has sought to explore how key features of populism, understood as political style, have impeded the effective management of COVID-19 by weakening state capacity. We have shown how disregard for scientific expertise, centralization of power, and measures to reduce accountability through polarization have targeted the main sources of state capacity in these states and, in doing so, have weakened the capacity of these states to extract, coordinate and achieve compliance in containing the health crisis.

Disregard of expertise has either totally incapacitated the state to act (in Brazil) or led to coordination and compliance problems at the vertical and/or horizontal levels (Turkey). The push for centralization in both cases translated into conflictual relations between the central and the local governments (or, in the case of Brazil, federal) as well as between the central state and extra-state actors. This weakened the coordination between central government and local authorities in the most acute phase of the pandemic. The Turkish government, for example, blocked opposition municipalities from extracting revenues that hampered effective local governance.

The analysis of the three cases has thus shown that not all the identified features of populist governance have played a similar role in the cases under analysis. Although common elements of populist governance have surfaced across different geographies when faced with the COVID-19 crisis, both their form and impact came in national colours. While disregard of expertise was present in both cases, it was combined with anti-science denialism in the case of Brazil, leading to a total failure. In the case of polarization, time was observed as a key factor in the extent of influence that it has had on the state's capacity to tackle the crisis. The longstanding polarizing discourse and policies of Erdoğan meant that government messages on the state of the pandemic or the necessary measures to limit transmission were received with mistrust by certain segments of the public, regardless of whether a solidarity discourse was adopted by the leader, as was the case with Erdoğan in Turkey in the early days of the pandemic.

This article has drawn attention to the importance of studying populism not merely in relation to democracy but also with respect to state capacity. We have suggested that in order to have a better understanding of how populist rule relates to state capacity in different areas of policymaking, we need to conceptually engage with populism as a political style which allows us to focus on populist political leadership and models of decision-making which impact on the capacity of states to deal with multi-layered crises. Using South Korea as a benchmark – and comparing it with Brazil and Turkey – we demonstrated that state capacity and political leadership are critical factors that inform governance performance in the COVID-19 pandemic.

State capacity will occupy a central stage in a post-pandemic world, with ongoing geopolitical conflicts, climate emergencies, economic protectionism, and other looming global challenges that expand beyond the health sector. In such a context, the question of how nations can build resilience through state capacity will gain even more significance. Our study has aimed to make a modest contribution to that debate through a focus on how a certain type of governance has had an impact on state capacity in the face of a truly global crisis that shook all states and their capacity to deliver.

Acknowledgments

We have been working on this article for a long time. We first developed the idea in the early days of COVID-19 and shared our initial thoughts at the ‘Epidemic and Society’ webinars organized by the Istanbul Policy Centre. Our contribution to the ‘Politics of COVID-19 Pandemic: Explaining Diverging State Responses in the Global South’ project at City, University of London (led by Madura Rasaratnam and Mustafa Kutlay) in the form of a policy briefing on pandemic management in Turkey provided additional momentum for the paper. We want to thank Oliver Stuenkel and four anonymous reviewers for their comprehensive feedback on different versions of the manuscript. We also thank Ali Baydarol for his excellent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Senem Aydın-Düzgit

Senem Aydın-Düzgit is a professor of International Relations at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Sabancı University, Turkey, and a Richard von Weizsäcker Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy, Berlin.

Mustafa Kutlay

Mustafa Kutlay is a senior lecturer at City, University of London, Department of International Politics, UK.

E. Fuat Keyman

E. Fuat Keyman is a professor of Political Science and International Relations at Sabancı University, Turkey.

Notes

1 The academic literature on the state has placed relatively more weight to the discussion of the sovereignty and power of states than their capacity, except for crisis periods such as the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis when the concept of state capacity came to the forefront. While we acknowledge that state capacity is also closely linked with state power and sovereignty, it is also a concept that is distinct from both in the way in which it relates to governance, sustainability, and resilience of states.

2 For a detailed chronology of events and examples of declining public trust, see Aydın-Düzgit et al. (Citation2021).

References

- Abrucio, L. F., Grin, J. E., Franzese, J., Segatto, I. C., & Couto, G., C. (2020). Combating COVID-19 under Bolsonaro’s federalism: A case of intergovernmental incoordination. Brazilian Journal of Public Administration, 54(4), 663–677.

- Acemoğlu, D., Garcia-Jimeno, C., & Robinson, J. A. (2015). State capacity and economic development: A network approach. American Economic Review, 105(8), 2364–2409. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20140044

- Aksoy, A. H. (2020). Turkey and the corona crisis: The instrumentalization of the pandemic for domestic and foreign policy. In IEMed Mediterranean Yearbook 2020. (https://www.iemed.org/publication/turkey-and-the-corona-crisis-the-instrumentalization-of-the-pandemic-for-domestic-and-foreign-policy/)

- Amsden, A. H. (1989). Asia’s next giant: South Korea and late industrialization. Oxford University Press Inc.

- Aydın-Düzgit, S. (2020). Turkey: Deepening discord and illiberalism amid the pandemic. In T. Carothers & A. O’Donohue (Eds.), Polarization and the pandemic. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/04/28/turkey-deepening-discord-and-illiberalism-amid-pandemic-pub-81650)

- Aydın-Düzgit, S., & Keyman, F. E. (2020). Governance, state, and democracy in a post-corona world. IPC Policy Brief. April. https://ipc.sabanciuniv.edu/Content/Images/Document/governance-state-and-democracy-in-a-post-corona-world-9825a1/governance-state-and-democracy-in-a-post-corona-world-9825a1.pdf

- Aydın-Düzgit, S., Kutlay, M., & Keyman, F. E. (2021). Politics of pandemic management in Turkey. Policy Briefing. Politics of COVID-19 Pandemic: Explaining Diverging State Responses in the Global South Project, September. https://politicsofpandemic.com/api/uploads/Turkey_pandemic_policy_briefing_published_3464d16146.pdf

- Bakır, C. (2015). Bargaining with multinationals: Why state capacity matters. New Political Economy, 20(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2013.872610

- Bakır, C. (2020). The turkish state’s responses to existential COVID-19 crisis. Policy and Society, 39(3), 424–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1783786

- Balta, E., & Özel, S. (2020). The battle over the numbers: Turkey’s low case fatality rate. Paris: Institut Montaigne. (https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/blog/battle-over-numbers-turkeys-low-case-fatality-rate)

- Bauer, W. M., & Becker, S. (2020). Democratic backsliding, populism, and public administration. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 3(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvz026

- Baykan, T. S. (2018). The justice and development party in Turkey: Populism, personalism, organization. Cambridge University Press.

- Bayram, H., Köktürk, N., Elbek, O., Kılınç, O., Sayıner, A., & Dağlı, E. (2020). Interference in scientific research on COVID-19 in Turkey. The Lancet, 396(10249), 463–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31691-3

- BBC News. (2020a). Coronavirus: Brazil passes 100,000 deaths as outbreak shows no sign of easing. August 9. (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-53712087)

- BBC News. (2020b). Coronavirus: Brazil resumes publishing Covid-19 data after court ruling. June, 9. (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-52980642)

- Beach, D. (2016). It’s all about mechanisms – what process-tracing case studies should be tracing. New Political Economy, 21(5), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2015.1134466

- Bengtsson, B., & Ruonavaara, H. (2017). Comparative process tracing: Making historical comparison structured and focused. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 47(1), 44–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393116658549

- Bennett, A., & Checkel, J. (Eds.). (2015). Process tracing: From metaphor to analytical tool. Cambridge University Press.

- Berwick, E., & Fottini, C. (2018). State capacity redux: Integrating classical and experimental contributions to an enduring debate. Annual Review of Political Science, 21(1), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-072215-012907

- Bilim Akademisi. (2020). It is problematic to subject scientific research on COVID-19 to permission. (https://en.bilimakademisi.org/it-is-problematic-to-subject-scientific-research-on-covid-19-to-permission/)

- Bosancianu, C. M., Hilbig, H., Humphreys, M., KC, S., Sampada, K. C., Lieber, N., & Scacco, A. (2020). Political and social correlates of COVID-19 mortality. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/ub3zd.

- Brown, F. Z., Brechanmacher, S., & Carothers, T. (2020). How will the coronavirus reshape democracy and governance globally? Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/04/06/how-will-coronavirus-reshape-democracy-and-governance-globally-pub-81470)

- Çakmaklı, C., Demiralp, S., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & Yesiltas, S., Yıldırım, M., (2020). COVID-19 and emerging markets: An epidemiological model with international production networks and capital flows. NBER Working Paper 27191, May 2020.

- Capano, G., Howlett, M., Jarvis, D. L. S., Ramesh, M., & Goyal, N. (2020). Mobilizing policy (In)Capacity to fight COVID-19: Understanding variations in state responses. Policy and Society, 39(3), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1787628

- Carothers, T., & O’Donohue, A. (2019). Democracies divided: The global challenge of political polarization. Brookings Institution Press.

- Casarões, G. S. P., & Leal Farias, D. B. (2022). Brazilian foreign policy under Jair Bolsonaro: Far-right populism and the rejection of the liberal international order. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 35(5), 741–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2021.1981248

- Chekar, C. K., Moon, J. R., & Hopkins, M. (2021). The secret to South Korea’s COVID success? Combining high technology with the human touch. The Conversation, October 21, https://theconversation.com/the-secret-to-south-koreas-covid-success-combining-high-technology-with-the-human-touch-170045

- Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (2020). Balancing governance capacity and legitimacy: How the Norwegian government handled the COVID-19 crisis as a high performer. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 774–779. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13241

- Christensen, T., Lægreid, P., & Rykkja, L. H. (2016). Organizing for crisis management: Building governance capacity and legitimacy. Public Administration Review, 76(6), 887–897. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12558

- de la Cruz, F., Tezanos, S., & Madrueño, R. (2022). State capacity and the triple COVID-19 crises: An international comparison. Forum for Development Studies, 49(2), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2022.2071334

- Deutsche Welle Turkish. Bahçeli’swn TTB Kapatılsın Çağrısı (Bahçeli Calls for Banning TTB). September 17, 2020. (https://www.dw.com/tr/bahçeli-ttb-kapatılsın-çağrısı-yaptı/a-54956075)

- Do Prado, M. F., et al. (2020). Analysis of COVID-19 under-reporting in Brazil. Revista Brasileira De Terapia intensiva, 32(2), 224–228.

- Dyer, P. (2021). Policy and institutional responses to COVID-19: South Korea, The Brookings Doha Center. (https://www.brookings.edu/research/policy-and-institutional-responses-to-covid-19-south-korea/)

- Elbek, O. (2020). COVID-19 Outbreak and Turkey. Turkish Thuracic Journal, 21(3), 215–216. https://doi.org/10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2020.20073

- Euronews. (2020). Araştırma: Sağlık Bakanlığı’nın COVID-19 Verilerine Güvenenlerin Oranı Yüzde 36′ya Düştü. (Poll: Those who Trust in the Data Provided by the Ministry of Health has Dropped to 36 per cent.) September 7. 2 (https://tr.euronews.com/2020/09/07/arast-rma-sagl-k-bakanl-g-n-n-covid-19-verilerine-guvenenlerin-oran-yuzde-30-a-dustu)

- Evans, P. B. (1995). Embedded autonomy: States and industrial transformation. Princeton University Press.

- Farias, D. B. L., Casaroes, G., & Magalhaes, D. (2022). Radical right populism and the politics of cruelty: The case of COVID-19 in Brazil under president bolsonaro. Global Studies Quarterly, 2(2), 1–13.

- Fonseca, P., & Gaier, R. V. (2020). Brazil’s rio risks second wave of COVID-19 with Ill-timed reopening. Reuters, September 16. (https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-brazil-rio/brazils-rio-risks-second-wave-of-covid-19-with-ill-timed-reopening-idUSL1N2GC240)

- Fox, T. (2020). Brother Tayyip’s soup kitchen. Foreign Policy, April 17. (https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/17/erdogan-turkey-coronavirus-relief-politics-akp-chp-brother-tayyip-soup-kitchen/)

- France 24. (2020a). Another disease plagues Brazil COVID fight: Corruption. August 28. https://www.france24.com/en/20200826-another-disease-plagues-brazil-covid-fight-corruption

- France 24. (2020b). Brazil COVID-19 death toll surpasses 90,000 as government ends travel ban. July 30. https://www.france24.com/en/20200730-brazil-COVID-19-19-coronavirus-jair-bolosnaro-death-toll

- Fukuyama, F. (2013). What is governance? Governance, 26(3), 347–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12035

- Gazete Duvar. (2020). Metropoll Araştırması (Metropoll Poll). May 6. (https://www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/gundem/2020/05/06/metropoll-arastirmasi-mansur-yavas-tayyip-erdogani-gecti)

- Government of the Republic of Korea. (2020). All about Korea’s response to Covid-19. Ministry of Interior and Safety, 20 October, https://www.mois.go.kr/eng/bbs/type002/commonSelectBoardArticle.do?bbsId = BBSMSTR_000000000022&nttId = 80581

- Granada, D. (2020). The management of the coronavirus pandemic in Brazil and necropolitics: An essay on an announced tragedy. Somatosphere. (http://somatosphere.net/2020/brazil-necropolitics.html/)

- Greer, S. L., King, J. E., da Fonseca, M. E., & Peralta-Santos, A. (2020). The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. Global Public Health, 15(9), 1413–1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1783340

- Guimaraes, F. d. S., & de Oliveira e Silva, I. D. (2021). Far right populism and foreign policy identity: Jair bolsonaro’s ultra-conservatism and the New politics of alignment. International Affairs, 97(2), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa220

- Hartley, K., & Jarvis, D. S. L. (2020). Policymaking in a Low-trust state: Legitimacy, state capacity, and responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Policy and Society, 39(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1783791

- Hendrix, S. C. (2010). Measuring state capacity: Theoretical and empirical implications for the study of civil conflict. Journal of Peace Research, 47(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310361838

- Kapucu, N., & Moynihan, D. (2021). Trump’s (mis)management of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. Policy Studies, 42(5–6), 592–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2021.1931671

- Kavaklı, K. C. (2020). Did populist leaders respond to the COVID-19 pandemic more slowly? Evidence from a global sample. Working Paper. https://kerimcan81.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/covidpop-main-2020-06-18.pdf

- Kavanagh, M. M., & Singh, R. (2020). Democracy, capacity and coercion in pandemic response – COVID-19 in comparative political perspective. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(6), 997–1012. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8641530

- Kay, J., & King, M. (2020). Radical uncertainty. The Bridge Street Press.

- Kayaalp, E., & İbrahim, B. I. (2020). COVID-19 and healthcare infrastructure in Turkey. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. https://medanthroquarterly.org/rapid-response/2020/08/covid-19-and-healthcare-infrastructure-in-turkey/

- Kim, J.-H. (2021). Emerging COVID-19 success story: South Korea learned the lessons of MERS. 5 March, https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-south-korea

- Kleinfeld, R. (2020). Do authoritarians or democratic countries handle pandemics better? Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/03/31/do-authoritarian-or-democratic-countries-handle-pandemics-better-pub-81404)

- Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. Verso.

- Levinson, J. D. (2014). Incapacitating the state. William and Mary Law Review, 56(1), 181–226.

- Lindvall, J., & Teorell, J. (2016). State capacity as power: A conceptual framework. STANCE Working Paper Series, No. 1. Lund: Lund University.

- Londono, E., Andreoni, M., & Casado, L. (2020). Brazil, once a leader, struggles to contain virus amid political turmoil. New York Times, May 16. .

- Louault, F. (2022). Populism and authoritarian drift: The presidency of bolsonaro in Brazil. In A. Dieckoff, C. Jaffrelot, & E. Massicard (Eds.), Contemporary populists in power (pp. 93–111). Palgrave.

- Lührmann, A., Marquardt, K. L., & Mechkova, V. (2020). Constraining governments: New indices of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal accountability. American Political Science Review, 114(3), 811–820. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000222

- Mann, M. (1984). The autonomous power of the state: Its origins, mechanisms and results. European Journal of Sociology, 25(2), 185–213. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975600004239

- Mann, M. (2008). Infrastructural power revisited. Studies in Comparative International Development, 43(3–4), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-008-9027-7

- Mao, Y. (2021). Political institutions, state capacity, and crisis management: A comparison of China and South Korea. International Political Science Review, 42(3), 316–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512121994026

- McKee, M., Gugushvili, A., Koltai, J., & Stuckler, D. (2021). Are populist leaders creating the conditions for the spread of COVID-19? International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10(8), 511–515.

- Meckling, J., & Nahm, J. (2018). The power of process: State capacity and climate policy. Governance, 31(4), 741–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12338

- Micinski, R. N., & Bourbeau, P. (2023). Capacity-Building as intervention-lite: Migraton management and the global compacts. Geopolitics. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2023.2170789

- Migdal, J. (1994). The state in society: An approach to struggles for domination. In J. Migdal, A. Kohli, & V. Shue (Eds.), State power and social forces. Cambridge University Press.

- Migdal, J., Kohli, A., & Shue, V. (1994). State power and social forces. Cambridge University Press.

- Mignozetti, U., & Spektor, M. (2019). Brazil: When political oligarchies limit polarization but fuel populism. In T. Carothers & A. O’Donohue (Eds.), Democracies divided: The challenge of political polarization (pp. 228–257). Brookings Institution Press.

- Moffitt, B. (2015). How to perform crisis? A model for understanding the Key role of crisis in contemporary populism. Government and Opposition, 50(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.13

- Moffitt, B. (2016). The global rise of populism: Performance, political style, and representation. Stanford University Press.

- Moisio, S. (2020). State power and the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Finland. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 61(4–5), 598–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1782241

- Monteiro, M. (2020). Science is a War zone: Some comments on Brazil. Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society, 3(1), 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/25729861.2019.1708606

- Moon, J. M. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 with agility, transparency and participation: Wicked policy problems and new governance challenges. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13214

- Moon, J. M., Suzuki, K., In Park, T., & Sakuwa, K. (2021). A comparative study of COVID-19 responses in South Korea and Japan: Political nexus triad and policy responses. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 87(3), 651–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852321997552

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C. (2020). Will the coronavirus ‘Kill Populism’? Don’t count on it. The Guardian, May 27. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/27/coronavirus-populism-trump-politics-response

- Müller, J.-W. (2016). What is populism? University of Pennsylvania Press.

- OECD. (2020). Transparency, communication and trust: The role of public communication in responding to the wave of disinformation about the new coronavirus. OECD Policy Response. Paris: OECD.

- Öniş, Z. (1991). The logic of the developmental state. Comparative Politics, 24(1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.2307/422204

- Ostiguy, P. (2009). The high and the low in politics: A two-dimensional political space for comparative analysis and electoral studies. Kellogg Institute Working Paper No. 360.

- Ostiguy, P. (2017). Populism: A socio-cultural approach. In C. R. Kaltwasser, et al. (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 73–97). Oxford University Press.

- Pappas, T. S., & Kriesi, H. (2015). Populism and crisis: A fuzzy relationship. In H. Kriesi & T. S. Pappas (Eds.), European populism in the shadow of the great recession (pp. 303–325). ECPR Press.

- Paquet, M., & Schertzer, R. (2020). COVID-19 as a complex intergovernmental problem. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 53(1), 343–347. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000281

- Pedroso, R., Reverdosa, M., & Barnes, T. (2020). As coronavirus cases explode in Brazil, so do investigations into alleged corruption. CNN, July 8. (https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/08/americas/brazil-coronavirus-corruption-intl/index.html)

- Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (2019). Populism and public administration: Confronting the administrative state. Administration & Society, 51(10), 1521–1545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399719874749

- Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (2020). A typology of populism: Understanding the different forms of populism and their implications. Democratization, 27(6), 928–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1751615

- Rodrik, D., & Walt, S. (2021). How to construct and new global order. (https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/new_global_order.pdf)

- Rosenthal, U., Charles, M. T., & Hart, P. (Eds.). (1989). Coping with crises: The management of disasters, riots and terrorism. Charles C. Thomas.

- Scharpf, F. (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and democratic? Oxford University Press.

- Serikbayeva, B., Abdulla, K., & Oskenbayev, Y. (2021). State capacity in responding to COVID-19. International Journal of Public Administration, 44(11–12), 920–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2020.1850778

- Sharma, D. G., Talan, G., & Jain, M. (2020). Policy response to the economic challenge from COVID-19 in India: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(4), 1–16.

- Siedlok, F., Hamilton-Hart, N., & Shen, H.-C. (2021). Taiwan’s COVID-19 response: The interdependence of state and private sector institutions. Development & Change, 53(1), 190–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12702

- Sikkink, K. (1991). Ideas and institutions: Developmentalism in Brazil and Argentina. Cornell University Press.

- Spektor, M. (2020). Brazil: Polarizing presidential leadership and the pandemic. In T. Carothers & A. O’Donohue (Eds.), Polarization and the pandemic. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/04/28/brazil-polarizing-presidential-leadership-and-pandemic-pub-81639)

- Stasavage, D. (2020). Democracy, autocracy, and emergency threats: Lessons for COVID-19 from the last thousand years. International Organization, 74(supplement), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000338

- The Lancet (Editorial). (2020). COVID-19 in Brazil: ‘So What?’. The Lancet, 395(10235), 1461. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31095-3

- Turkish Medical Association. (2020). COVID-19 sixth evaluation report. April, 20. https://www.ttb.org.tr/yayin_goster.php?Guid = 42ee49a2-fb2d-11ea-abf2-539a0e741e38

- Urban, M., & Saad-Diniz, E. (2020). Why Brazil’s COVID-19 response is failing? The Regulatory Review, June 22. (https://www.theregreview.org/2020/06/22/urban-saad-diniz-brazil-covid-19-response-failing/

- Weiss, L., & Thurbon, E. (2022). Explaining divergent national responses to COVID-19: An enhanced state capacity framework. New Political Economy, 27(4), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1994545

- Weyland, K. (2017). Populism: A political-strategic approach. In C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. O, Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 48–73). Oxford University Press.

- Zilla, C. (2020). Corona crisis and political confrontation in Brazil: The president, the people, and democracy under pressure. SWP Comment. No. 36. Berlin: SWP. (https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.184492020C36/)