This is the first in a new regular edition of the Bulletin of Spanish Studies on Visual Studies. The editors marked its inauguration by asking a number of major visual-studies scholars based in the UK, or whose career began there, to place the trajectory of their own academic work within the development of the wider (and still growing) field of Visual Hispanic Studies. Our intention is not by any means to set a UK-biased agenda, but to celebrate the role the Bulletin has played, and continues to play, in the development of Hispanism in the UK and beyond. This focus also marks the fact that, despite initial resistance from some quarters, the growth of Visual Studies within Modern Languages across Europe and the Americas has taken on such momentum that any attempt on our part to mark its development without limiting the geographical scope would have been impossible. In spite of a title that might suggest a bias towards Spain, it has always been the intention of the Bulletin to expand the parameters of Spanish Studies,Footnote1 and from the outset, back in the 1920s, this meant incorporating work on Portugal and Latin America and attempting to find a linguistically elegant, yet ideologically uncontroversial, way of acknowledging the debated borders of what we think of as the ‘hispanic’.Footnote2 As Ann Mackenzie pointed out in an article commemorating the journal’s eightieth year, the focus has always been on international scholarship, collaboration and mentorship.Footnote3 To mark this tradition, the editors have asked our contributors to focus part of their essay on their own academic trajectory, in the hope that this might inspire future editions on visual topics including, but not limited to the ones offered here: on TV studies, adaptation, dance, photography, digital film-making, documentary film-making and sculpture.

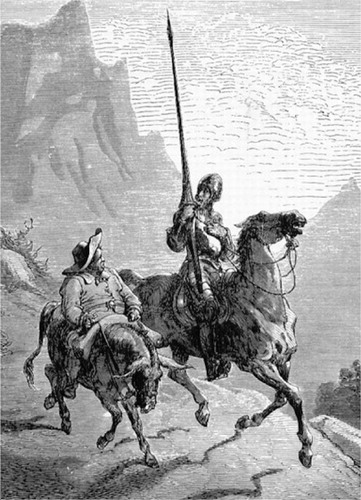

This familiar image could be regarded as a slightly tongue-in-cheek metonym for the ‘visually hispanic’. It is also a reminder of the intimate connection that exists between image and text and of the condensed impact the visual has upon the verbal.Footnote4 Most viewers will recognize these men illustrated here by Doré as Don Quijote and Sancho Panza, fewer will have read El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha from cover to cover, and yet, without the mass appeal of the original, this would just be a tall knight with a long lance and a stout man on a donkey: the contrast might be amusing, but the image would have no particular affective force. Such are the connections between the visual and the verbal that we celebrate in this first regular Visual Studies issue of the Bulletin of Spanish Studies, along with the ever-expanding boundaries of a discipline whose mobile focus of inquiry is indicated in the Bulletin’s lengthy subtitle: Hispanic Studies and Researches on Spain, Portugal and Latin America.

The Visual Studies strand of UK Hispanism has, of course, passed through many stages since the 1980s when Spanish-language film was gradually—and often grudgingly—accepted on to the Modern Language curriculum. At that time, the range of films available was so limited that academic attention focused almost by default on auteurs like Buñuel, Saura and Erice. Since those early days, however, the discipline has kept pace with the mechanics of reproduction, responding to the release on DVD of an ever-widening range of experimental and popular auteurs, genre-films and TV series, and adjusting its theoretical foundations to support changing preoccupations. Film is the Saturn-like art that feeds off the other six (Hegel’s Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Dance, Music, Poetry), so it is not surprising that as visual theory has adapted to the speedy, slippery evolution of the society of the spectacle, academics in Modern Languages have trespassed with increasing confidence across the boundaries that once separated academic disciplines. There are many imaginary maps of Visual Hispanism that could be tracked, say, from 1984, when Ted Riley stepped from the Spanish Golden Age into Film Studies with an article on Erice published in this journal, to 2008, when Catherine Grant, having extended her Hispanic Studies expertise to the editorial board of Screen, wrote the first of her now highly influential film blogs: Film Studies for Free.Footnote5 This imaginary map could, of course, be tracked back to different origins and mapped on to different pathways, all of which were punctuated by a series of theoretical turns: the role of the auteur has been questioned; the economics of production has been brought into play; the balance of power in the field of the gaze has been scrutinized; the bias towards experimental and art film has been challenged and, more recently, the rise of interest in ‘embodied’ viewing has marked, perhaps for the first time, serious and widespread attempts to acknowledge the impact of the viewer’s position (gendered, academic or otherwise) on the process of perception.Footnote6 For all its manifest pleasures, the recent UK film Pride (Matthew Warchus, 2014) was harsh towards 1980s feminists who were fixated by subject positions: but it is to them that we owe the contemporary rise in affect studies. Although it may at times have seemed a bit po-faced in practice, announcing a speaking or viewing position is what lies at the heart of contemporary theoretical advances. So it is a pleasure to see that, despite their very different subject-matter and experience of Visual Hispanism, each of the following essays is marked in some way by the growth of affect studies and of attention to ‘embodied’ viewing.

Paul Julian Smith opens with an overview of the development of Hispanic Visual Studies. As someone who has written so widely on visual culture, he is well-placed to suggest that the way forward for the discipline lies in emphasizing transmedial connections, especially in the television drama which is the artistically and commercially dominant screen fiction in most Spanish-speaking countries. Smith also wonders whether the future of the auteurist films that were once the main focus of academic study may lie in art galleries rather than on our cinema screens. His recommendation is that we forge closer alliances with colleagues in Social Sciences and journalistic film reviewers in an effort to promote the Modern Languages tradition of close formal analysis while paying closer attention to industrial concerns. Sally Faulkner also addresses the transmedial, along with gendered bodies and the border crossings between literature, TV and film, in an essay that traces the development of Adaptation Studies from its faltering start in the 1990s—when the need to ‘corral’ film for academic study minimized the relationship between film and written text—to the more prominent part it now plays in the contemporary intermedial turn. She traces her growing interest in the middle-brow, then gives close attention to silent film, memory, cinephilia, colonialism and intertextuality in Portuguese director Miguel Gomes’ film, Tabu (Portugal, Germany, Brazil, France 2012). Julián Daniel Gutiérrez-Albilla deals with the Spanish dancer and choreographer La Ribot, who is one of the most internationally critically-acclaimed of contemporary Spanish dancer/performance artists, and yet whose work tends to be overlooked in the field of Spanish cultural studies. Focusing on the way her work undercuts the reification of live performance with video projections that problematize the political ontology of dance, this essay develops from his earlier investigation of embodiment and subjectivity and Spanish-language film. Gutiérrez-Albilla highlights the role of the body as ‘document’ in the transmission of memory and history from the body of one viewer, or participant, to the next, as well as foregrounding the significance of the medium of dance/performance art for thinking about the field of Spanish visual cultural studies more broadly.

In Andrea Noble’s essay, the body-as-messenger becomes, literally, a matter of life and death, as contemporary theoretical approaches to embodied viewing and affect take a sober turn to consider the iconography of the severed head in contemporary Mexico. Noble questions the ethics of viewing atrocity caused by narco violence and the bicentenary celebrations of Mexico’s independence from Spain. Addressing the role of cyberspace and print media in the dissemination of visual material, she emphasizes the need to attend to the strictly local power struggles that still hold sway in an ever-more global and virtual visual world. Her salutary reminder that journalism—to cite just one of her examples—may unwittingly invoke death sentences in Mexico is a useful counterbalance to our sometimes blasé approach to the blurring of national boundaries in contemporary visual studies.

The need to pay due attention to the local is also addressed in Rob Stone’s essay on digital and Basque film-making. The only one of our contributors to have come to Spanish (and Basque) language film by way of Film Studies, in his essay Stone generously acknowledges his mentors and introduces the motif of the broken frame to explore the digital revolution. Marking the blurring of boundaries between academic film criticism and practical filmmaking, this essay addresses his recent study of Basque cinema within the wider local cultures of literature, sport, music and food, and celebrates the difficulty of definition (of what we mean by Spanish cinema) as a positive point of departure. Stephen Hart also embraces academic theory, film practice and the digital turn in an essay that traces the increasing importance of practical filmmaking to his work on Latin-American film. His association with the Cuban film director Julio García Espinosa led to an invitation to teach documentary filmmaking courses at the Escuela International de Cine y Televisión in Havana that, in turn, inspired his first, hilarious, experience of making a short film on Vallejo in Paris. This alerted Hart to the symbiotic relationship that exists between screenplay and shooting process, and to the fact that the wider cinematic apparatus has a life of its own that may well have very little connection to the original direction.

Jo Evans uses Ortega y Gasset’s phrase, ‘yo soy yo y mi circunstancia’, as a verbal ‘Macguffin’ to retrace her experience of Visual Hispanism and examine the introduction of public art to the capital of Fuerteventura. Connecting the arrival of sculpture on the island with Unamuno’s exile there in 1924, this essay argues that the ‘parque escultórico’ is a useful reminder of the importance of ‘placement’ and of the dynamic relationship that exists between work and viewer, and suggests that, while public art will always reflect the dominant power in the gaze, the art brought to the capital by this series of symposia could be seen as a model of sustainable cultural development for recessionary times. The edition then ends with a brief postscript that turns away from the UK discipline, but also traces an earlier UK/Hispanic visual connection. Returning to Paul Julian Smith’s observations about the advantage of interactive collaboration across the Humanities and the Social Sciences, this brief postscript, based on an interview with one of Spain’s most prolific film historians, looks back to an earlier UK/Hispanic visual connection between Professor José María Caparrós Lera of Barcelona University and a previous-generation Paul Smith (a History scholar, rather than a Film and Visual Studies scholar), to mark the ongoing importance to the discipline of international collaboration across academic disciplines.Footnote7

This issue has a number of people to thank: Ann Mackenzie, and colleagues at Taylor and Francis, for suggesting the idea of a regular Visual Studies edition of the Bulletin, the Bulletin’s editorial team, Ceri Byrne in particular, and to our Special Guest Co-editor for this inaugural issue, Núria Triana-Toribio.

JO EVANS

University College London.

Notes

1 Ann L. Mackenzie, ‘The Next Century: The Bulletin Goes Forward’, Bulletin of Spanish Studies: Hispanic Studies and Researches on Spain, Portugal and Latin America, LXXIX:1 (2002), 7–32 (p. 8).

2 Mackenzie, ‘The Next Century’, 9; Ann Mackenzie points out (p. 10) that this is the reason for the Bulletin’s rather cumbersome subtitle: Hispanic Studies and Researches on Spain, Portugal and Latin America.

3 See Mackenzie, ‘The Next Century’, 11, 16.

4 Two of the contributors to this volume have discussed elsewhere the inseparability of the visual and the verbal. See Paul Julian Smith on an earlier piece by Andrea Noble, in Spanish Visual Culture: Cinema Television, Internet (Manchester/New York: Manchester U. P., 2006), 1.

5 See Mackenzie, ‘The Next Century’, 29, n. 54 for details of other Bulletin articles on film. Film Studies for Free can be consulted at: <http://filmstudiesforfree.blogspot.co.uk>(accessed 28 November 2014).

6 See, for example, Jennifer M. Barker, The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 2009); Barbara M. Kennedy, Deleuze and Cinema: The Aesthetics of Sensation (Edinburgh: Edinburgh U. P., 2002).

7 Paul Smith, Lecturer in History at Kings College London, and editor of The Historian and Film (Cambridge: Cambridge U. P.: 1976).