Abstract

Suicide by pesticide ingestion is one of the three most common global means of suicide, causing over 150,000 deaths each year. The majority occur in rural agricultural communities, where pesticides are readily available to small-scale farmers and their families in poor under-resourced households. In addition to enormous individual, communal and societal suffering, as well as public health, economic, and developmental harm, human exposure to pesticides leads to serious human rights violations. This article focuses on the right to life, as the main right impacted by pesticide suicides while touching upon other human rights implications of pesticide self-harm. Our analysis shows that, by failing to restrict access to highly hazardous pesticides, states violate their obligations under international human rights law. States, businesses and civil society need to apply the human rights-based approach to preventing pesticide suicides and to develop a comprehensive plan to phase out or ban the most harmful pesticides.

Introduction

Pesticide self-poisoning (suicide) constitutes a major public health problem in many parts of the world (see ). It is one of the three most important global means of suicide, together with hanging and shooting (World Health Organisation Citation2019a). Of the 800,000 individuals who die from suicide each year—one death every 40 seconds—up to 20 percent (World Health Organisation Citation2019a, 2019b) die from pesticide self-poisoning. Most affected are the rural agricultural communities in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where 75.5 percent of all global suicides occur.

Figure 1. A patient with organophosphorus insecticide self-poisoning being cared for in Teaching Hospital Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. Photograph by Michael Eddleston, 2003. The patient gave informed consent for the use of this photograph.

Globally, the proportion of suicides using pesticides varies sharply, from less than 4 percent in the European region to over 50 percent in the Western Pacific region (Mew, Padmanathan, Konradsen, Eddleston, Change, Phillips, and Gunnell Citation2017). In the 1980s–1990s, between 60 and 90 percent of suicides in China, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Trinidad and Tobago were by pesticide ingestion (Jeyaratnam Citation1990; Bertolote, Fleischmann, Butchart, and Besbelli Citation2006). A sharp increase in fatal self-poisoning happened in agricultural societies after the introduction of highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs)Footnote1 into agricultural practice in the 1960s. This has resulted in an estimated 14 million deaths since the Green Revolution (Karunarathne, Gunnell, Konradsen, and Eddleston Citation2020).

The wide availability and accessibility of HHPs is to blame for the high number of pesticide suicides. In rural areas, small-scale farmers store pesticides in, or in close proximity to, their homes and common use areas. High-concentration agricultural pesticide formulations are readily available for purchase in pesticide shops and in convenience stores, where they may be sold next to food and other everyday items (Vethanayagam Citation1962; Gunnell, Eddleston, Phillips, and Konradsen Citation2007). In a recent study of rural and semi-urban Sri Lanka, 79 percent of households used and stored high-strength agricultural pesticides (Pearson, Metcalfe, Jayamanne, Gunnell, Weerasinghe, Pieris, Priyadarshana, Knipe, Hawton, Dawson, Bandara, DeSilva, Gawarammana, Eddleston, and Konradsen Citation2017).

A large proportion of pesticide suicides are impulsive, with little planning (Eddleston, Karunaratne, Weerakoon, Kumarasinghe, Rajapakshe, Sheriff, Buckley, and Gunnell Citation2006; Conner, Phillips, Meldrum, Knox, Thang, and Yang Citation2005). Most persons who engage in suicidal behavior are ambivalent about wanting to die, with self-harm serving as a response to often transient psychosocial stressors (World Health Organization Citation2018b). Surviving a suicidal action usually allows the person to find the support he or she requires from family, community or social and mental health services, and a different way to deal with the crisis.

The link between suicide and mental illness is not as prominent in LMICs as in high-income countries, although researchers have proposed a link between pesticide use, depression, and suicide (Meyer, Koifman, Koifman, Moreira, De Rezenda Chrisman, and Abreu-Villaça Citation2010; London, Flisher, Wesseling, Mergler, and Kromhout Citation2005). This link is weak because individuals with little suicidality die when they ingest highly hazardous pesticides with little thought, after just minutes of contemplation, with no ability to change the outcome after ingestion. Awareness is rising of the more appropriate view of suicide as a social and public health issue that is best addressed by social and public health programs, rather than solely within a mental health framework (Vijayakumar Citation2007).

Since the 2000s, the number of pesticide suicides has decreased, impacted by effective pesticide regulation, mechanization of agriculture, and migration from countryside to cities (Gunnell, Knipe, Chang, Pearson, Konradsen, Lee, and Eddleston Citation2017; Mew et al. Citation2017). However, conservative estimates suggest that there are at least 110,000 deaths from pesticide self-poisoning worldwide annually, with 168,000 likely to be a better estimate when underreporting in India is included (Mew et al. Citation2017). Pesticide suicides are underreported due to the stigma of suicide and its criminalization in some countries (Mew et al. Citation2017; Gunnell et al. Citation2017). In addition, in many countries, incidence reporting and data collection on suicide are unreliable due to weak surveillance systems, making it difficult to obtain good quality estimates of suicide incidence (Knipe, Chang, Dawson, Eddleston, Konradsen, Metcalfe, and Gunnell Citation2017).

Reducing access to the means of suicide is an effective way to prevent pesticide suicides

From a public health perspective, restricting access to the means of suicide is likely to be the most effective way to prevent deaths due to pesticide self-poisoning. Means restriction as a method of suicide prevention has widely proven its effectiveness: Restricting access to railway platforms and bridges used for jumping, introducing strict gun laws, removal of carbon dioxide from domestic gas, and limiting access to medicines used for suicides have all decreased deaths from suicide worldwide (Yip, Caine, Yousuf, Chang, Wu, and Chen Citation2012). Banning and removing HHPs from agricultural practice through legislation and importation limitations, and otherwise reducing availability—especially where the intent is low (World Health Organization Citation2009a) and pesticide poisoning is a common means of suicide—have demonstrated their effectiveness in many countries (Gunnell et al. Citation2017).

The public health perspective prioritizes prevention and population-based strategies for preservation of public health and well-being. Introduction of public health measures, such as limitations on advertising and sale of tobacco and alcohol and prescription sale of certain medicines, helps achieve protection of public health (Hemenway, Barber, and Miller Citation2010), especially for persons in situations of vulnerability. Similarly, restricting access to HHPs is especially important in cases of vulnerable agricultural populations living in LMICs without adequate access to information on pesticide harms, opportunities for protection from exposure, treatment of poisoning, and counseling in instances of distress (Gunnell, Eddleston, et al. Citation2007). It is argued that, in these cases, public health considerations and rights of individuals to be free from, for example, second-hand smoke, gun violence, unsafe driving, or HHPs harms outweigh the freedom of choice to use these products by others (Ulrich Citation2019).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that many pesticide suicides could be prevented through restricting access to poisons (World Health Organization Citation2016). Many people feel suicidal from time to time. Means restriction works because suicidal impulses are usually transient, lasting only minutes or hours (World Health Organization Citation2014). The easy accessibility of lethal means, such as guns or HHPs, during these periods of heightened risk may make the difference between survival and death (Eddleston and Gunnell Citation2020). Making such means difficult to access will often result in the use of a less lethal means (such as self-poisoning with medicines) or prevent the suicide attempt from occurring altogether. Surviving a suicide attempt allows the person to return to her or his family and community and obtain the support she or he may need from mental health services. The great majority of survivors do not go on to repeat the act or to die from suicide (Carroll, Metcalfe, and Gunnell Citation2014). Means restriction makes suicidal impulses survivable, whatever the surrounding situation and stresses (Eddleston and Gunnell Citation2020).

Government regulations to reduce the availability of HHPs offered a highly cost-effective means to dramatically reduce pesticide suicides in South Korea, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. The best evidence for the effectiveness of this approach from suicide comes from Sri Lanka.

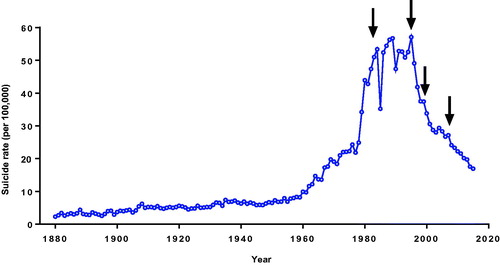

With the introduction of pesticides into everyday use in Sri Lanka during the Green Revolution of the 1960–1970s, the annual suicide rate increased from 5 per 100,000 population to 24 per 100,000 in 1976, and to astonishing 57 per 100,000 in 1995. In response to this crisis, the Office of the Registrar of Pesticides in 1983 started to ban the HHPs most responsible for pesticide suicides. Parathion and methyl parathion were banned in 1984; all remaining WHO Class I toxicity organophosphorus insecticides (including methamidophos and monocrotophos) in 1995; endosulfan in 1998; and paraquat, fenthion, and dimethoate in 2008–2011 (Knipe, Chang, et al. Citation2017). The 1983 ban appears to have stopped the exponential rise in national suicide rate; the subsequent bans have resulted in a dramatic decline in the total national suicide rate: greater than 70 percent over 20 years (see ). The suicide rate in Sri Lanka is currently 17 per 100,000 and continues to fall (Knipe, Gunnell, and Eddleston Citation2017). The bans have saved an estimated 93,000 lives at an estimated direct governmental cost of less than $2 per disability-adjusted-life-year (DALY),Footnote2 or $50 per life. Importantly, the ban of these HHPs in Sri Lanka was not associated with any apparent effect on agricultural cost or yields (Manuweera, Eddleston, Egodage, and Buckley Citation2008), and switching to other means of suicide was insignificant (Gunnell, Fernando, Hewagama, Priyangika, Konradsen, and Eddleston Citation2007).

Figure 2. Incidence of suicide in Sri Lanka, 1880–2015. Arrows show timing of pesticide bans (1984: parathion, methylparathion; 1995: all remaining WHO class I toxicity pesticides, including methamidophos and monocrotophos; 1998: endosulfan; 2008: dimethoate, fenthion, paraquat). Reproduced with permission from Knipe, Gunnell, and Eddleston (Citation2017).

Prior to its ban in 2011–2012, the herbicide paraquat was responsible for the majority of suicides in the rural areas in the Republic of Korea, accounting for 35.5 percent of all pesticide-related deaths. After the government refused a license renewal, banned all production (2011), and prohibited distribution (2012), the pesticide suicide mortality halved from 5.26 to 2.67 per 100,000 population between 2011 and 2013. Method substitution occurred but did not exceed the reduction in the suicide rate of poisoning, so the reduction in overall suicide rate was sustained (Myung, Lee, Won, Fava, Mischoulon, Nyer, Kim, Heo, and Jeon Citation2015; Cha, Chang, Gunnell, Eddleston, Khang, and Lee Citation2016).

In Bangladesh, after all WHO Class I toxicity HHPs were banned in 2000, there were 35,071 (95 percent CI [confidence interval] 25,959 to 45,666) fewer pesticide suicides in 2001–2014 compared with the number predicted based on trends in 1996–2000. Pesticide poisoning deaths fell from 6.3 per 100,000 in 1996 to 2.2 per 100,000 in 2014, with the overall incidence of unnatural deaths falling from 14.0 per 100,000 to 10.5 per 100,000 (Chowdhury, Dewan, Verma, Knipe, Isha, Faiz, Gunnell, and Eddleston Citation2018).

Restricting access to highly lethal means of suicide is a key way to rapidly reduce suicidal deaths (Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman, Sarchiapone, Carli, Hoschl, Barzilay, Balazs, Purebl, Kahn, Saiz, Lipsicas, Bobes, Cozman, Hegerl, and Zohar Citation2016). Complimentary measures include responsible reporting of suicide in the media (such as avoiding language that sensationalizes suicide and explicit descriptions of methods used), early identification and management of mental and substance-use disorders, and follow-up care through regular contact, including by phone or home visits, for people who have attempted suicide, together with provision of community support (World Health Organization Citation2014).

Pesticides, suicides, and human rights

In addition to the enormous suffering and loss placed by pesticide self-poisoning on individuals, their families, communities, and society, the wide availability of HHPs in poor rural communities unable to store or use them safely infringes on individual human rights, such as the right to life, the right to health, the rights to a clean environment, food and clean water, information, remedy, as well as labor and environmental standards. After discussing the most important right in relation to suicides—the right to life—we will touch on other important rights.

The right to life

Many human rights are impacted by the wide availability of HHPs, their use in self-harm and poisoning, and the resulting high number of deaths despite low intention to die. However, the main affected human right is the right to life. Life historically enjoys special status and protection in jurisdictions around the world (Wicks Citation2010). Usually domestic protection of the right to life concentrates on the general criminal law prohibition of the “arbitrary” deprivation of human life. In the question of suicide prevention, the burden usually is placed on healthcare and mental health professionals, police, and school councilors to ensure mental health support and protection of life of suicidal individuals (Wicks Citation2010; Ho Citation2014).

Based on the analysis of international human rights law, we argue that in certain circumstances the state has an obligation to take positive measures to protect the right to life of individuals in the situation of vulnerability in the community from self-inflicted harm. Furthermore, by allowing easy access to highly toxic substances such as pesticides by vulnerable rural individuals, states violate their duty to protect life. As demonstrated, preventing access to HHPs at moments of suicidality markedly increases the chance that the person will use a less lethal method, thereby surviving, or not harming him- or herself at all.

The value of life has been the object of considerable philosophical debate for over two millennia (Mishara and Weisstub Citation2005). The discourse has evolved from Judeo-Christian religious beliefs in the sanctity of life determined by God to philosophical ideas about the inherent dignity and worth of each individual in the human rights system. The initial prohibition on intentional killing as the primary obligation of the state (a negative obligation) has grown into a positive obligation to preserve the lives of individuals if the state has jurisdiction and physical control over the persons (Allen Citation2013; Ho Citation2014).

Currently, the right to life is entrenched in the constitutions and other legislations of the majority of common and civil law countries. States affirm their interest in preserving the lives of their residents by adopting suicide prevention and mental health strategies and by placing restrictions on access to suicide means, such as barriers on bridges, railway, and train platforms and prescription medicine sale and gun control rules. It is also confirmed by the fact that, in jurisdictions that allow it, physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia is allowed only in certain strictly limited circumstances. Some countries even criminalize suicide by imposing fines or prison sentences on suicide survivors (Mishara and Weisstub Citation2016).Footnote3

International human rights law has developed the ideas of the right to life further. Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states, “everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person” (United Nations General Assembly Citation1948). According to Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), “every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life” (United Nations General Assembly Citation1966a).

The General Comment No 36 (United Nations Human Rights Committee Citation2018) on the right to life helps countries to understand the extent of their obligations under the ICCPR. The General Comment affirmed:

[T]he right to life has crucial importance both for individuals and for society as a whole. It is most precious for its own sake as a right that inheres in every human being, but it also constitutes a fundamental right whose effective protection is the prerequisite for the enjoyment of all other human rights and whose content can be informed by other human rights (United Nations Human Rights Committee Citation2018).

The General Comment No 36 further noted that the right to life should not be interpreted narrowly. It concerns the entitlements of individuals to be free from acts and omissions that may be expected to cause their unnatural or premature death (para. 3). Paragraph 1 of Article 6 of the ICCPR provides that no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his or her life and that the right shall be protected by law. The duty to protect the right to life includes an obligation for state parties to adopt any appropriate laws and other measures in order to protect life from all reasonably foreseeable threats (para. 18). It requires states parties to take special measures of protection toward persons in situation of vulnerability whose lives have been placed at particular risk because of specific threats or preexisting patterns of violence (para. 23).

Particularly on the subject of suicide, the General Comment states, “While acknowledging the central importance to human dignity of personal autonomy, States should take adequate measures, without violating their other Covenant obligations, to prevent suicides, especially among individuals in particularly vulnerable situations” (para. 9).Footnote4

The duty to take positive measures to protect the right to life derives from the general duty to ensure the rights recognized in the Covenant (Article 2, para. 1) when read in conjunction with Article 6, as well as from the duty to protect the right to life by law (United Nations Human Rights Committee Citation2018). States are under a due diligence obligation to undertake reasonable positive measures that do not impose on them disproportionate burdens (para. 21).

Regional human rights systems also put the right to life at the center of their framework. Article 2 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) states, “Everyone’s right to life shall be protected by law” (Council of Europe Citation1950). Similar to the interpretation of UN agencies, the European Court of Human Rights affirms that state must not only refrain from the “intentional “taking of life (negative obligation) but also take appropriate steps to safeguard the lives of those within its jurisdiction (positive obligation).Footnote5

The African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR) entrenches the right to life in Article 4 (Organisation of African Unity Citation1981). Article 4 of the American Convention on Human Rights provides similar guarantees (Organization of American States Citation1969). The right to life is also recognized as part of customary international law, making it obligatory to states that have not ratified major human rights treaties. The right to life is one of the peremptory norms (jus cogens) from which no derogation is permitted, confirming its special status.

Thus, states’ obligation to protect life includes positive obligation to protect the right to life and offers a stronger protection to people in a state’s jurisdiction and in the situation of vulnerability. It follows that, in certain circumstances, states are under an obligation to take positive measures to protect life, even against actions by which individuals endanger themselves, particularly if they are in the jurisdiction and physical control of the state or in the situation of vulnerability. Usually, UN agencies identify rural workers and peasants as such a group, including the most vulnerable people working in rural areas, smallholder farmers, and landless workers (United Nations General Assembly Citation2012).

Several factors make it difficult for peasants and other people working in rural areas to make their voices heard, to defend their human rights and tenure rights, and to secure the sustainable use of the natural resources on which they depend. Rural women carry out a disproportionate share of unpaid work; are often heavily discriminated against in the access to natural and productive resources, financial services, information, and employment and social protection; and face violence in manifold forms (United Nations General Assembly Citation2012).

A wide range of factors put farmers and agricultural/rural communities in the situation of vulnerability, including: poverty; lack of education and information about harms associated with pesticides use; lack of social, health, and community services; gender inequality; domestic violence; dowry issues; long distance to urban areas where more services are available (Chapman and Carbonetti Citation2011).

The UN Declaration on Peasants affirmed that small-holder farmers and people living and working in rural areas—being especially affected by climate change, poverty, and the changing dynamics in agriculture, input, and food markets that all are placing pressure on their traditional lifestyles, food security, and modes of livelihood—are among the most vulnerable groups in the world (United Nations Human Rights Council Citation2018). The recognition that smallholder farmers and other rural populations are among the most discriminated against and vulnerable people in many parts of the world underlines that special measures need to be taken to lessen the impact of HHPs on rights and lives.

In the case of pesticide suicides, the wide availability of highly hazardous substances in agricultural communities puts people who are poorly equipped to understand dangers associated with these hazardous substances into direct risk to their lives. The ICCPR obliges states to take positive measures to protect the right to life of vulnerable individuals, means that states need to take action to restrict the wide availability of these substances in rural communities, thus protecting peoples’ right to life.

A clear distinction needs to be drawn between people wishing to die to avoid suffering or debilitating and painful illness and those vulnerable individuals resorting to self-harm with lethal means in a moment of short-lived crisis. For the impulsive suicides in LMICs in the situation of vulnerability, absence of counseling and mental health services, as well as recourse and coping means in a case of personal conflict, the state has an obligation to prevent suicide. State-approved physician-assisted suicide in clearly defined circumstances and strictly implemented safeguardsFootnote6 allow terminally ill people, who experience severe physical or mental pain and suffering, to die with dignity. These measures exist usually in high-income countries (HICs), due to careful balancing of the interests of the state in protecting “sanctity” of life and competing interests, such as personal autonomy, dignity, and respect for private and family life (Wicks Citation2010; Tiensuu Citation2015).

This article argues that states’ heightened obligation to protect the right to life of vulnerable individuals, such as people working and living in rural communities, encompasses the duty to adopt positive measures to protect people’s right to life. This is done by severely restricting or banning means of suicide such as HHPs to protect vulnerable individuals without the long-standing predetermination to end their life—as is normally the case with pesticide suicides. Needless to say, such measures will also help to mitigate environmental, public health, and other harmful impact of HHPs use.

What else do states need to do to protect the right to life?

States that have ratified such binding international treaties as the ICCPR and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR; United Nations General Assembly Citation1966b) or that adhere to the UDHR have a legal obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill the human rights of people residing in their territories, including to give effect through legislative and other measures, and to provide effective remedies and reparation to all victims of violations of the right to life.

In addition to restricting or banning HHPs to protect the right to life from impulsive suicides of people in the situation of vulnerability, there are lesser obligations the right to life imposes on states. The obligation to respect the right to life requires states to refrain from engaging in conduct interfering with the enjoyment of the right. States should avoid encouraging pesticide use; eliminate tax incentives and subsidies for pesticide use; and refrain from marketing, advertising, and officially registering unsafe products, including HHPs.

The obligation to protect the right to life requires state parties to establish a legal framework to ensure the full enjoyment of the right to life by all individuals as may be necessary to give effect to the right to life (United Nations Human Rights Committee Citation2018). This may include the duty to enact and enforce necessary laws and policies on sound management of chemicals and pesticides and to adopt legislation addressing heightened vulnerability of farmers and agricultural workers. It requires states to protect life from all possible threats, including preventing third parties from interfering with the right to life. States must ensure that private actors (i.e., the pesticide and agricultural industry) comply with environmental, human rights, and other standards and provide adequate information and marketing for their products, including with regard to dangers presented by HHPs.

The obligation to fulfill requires states to create legal, institutional, and procedural conditions to fully realize human rights implicated by pesticides. The extent of this obligation varies according to the available resources. This may mean an obligation to enact national mental health and suicide prevention strategies, ensuring access to impartial legal remedies when human rights violations are alleged, decriminalizing suicide and self-harm, and protecting survivors and their families from discrimination. Knowing that wide availability to HHPs may lead to their use as means of suicide in a moment of crisis, states should provide mental health, counseling, social, and community services; protection from domestic violence; and measures for organizing community support and aimed at decreasing stigma and prejudice associated with suicide.

Other human rights

The brief overview below of other human rights influenced by the wide availability of HHPs for self-harm and suicide is presented in order to draw a general picture of how stricter pesticide management could help address some of the issues faced by vulnerable rural communities.

The 2017 Report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food affirmed that “hazardous pesticides impose a high cost on governments and have catastrophic impact on the environment, human health and society as a whole, implicating a number of human rights and putting vulnerable groups at elevated risk of rights abuses” (UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Citation2017). The Rapporteur emphasized that HHPs have “detrimental impacts on internationally recognized human rights,” stating, “Evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates the inability of States and businesses to ensure that HHPs will be used safely throughout their lifecycle. Among those at grave risk of becoming victims of HHPs are agricultural workers, children, and low income and minority communities, especially in developing countries.”

The report called for a worldwide phase-out of HHPs that inflict significant damage on human rights, health, and the environment, stating, “Risks are particularly grave in developing countries, many of which import these highly hazardous pesticides despite having inadequate systems to reduce risks” (UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Citation2017). The report emphasized that, despite the evidence that there are almost always safer alternatives to highly hazardous pesticides available, HHPs continue to be used widely.

The right to health

The right to health stems from Article 25 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 25 affirms “the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, water, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services” (United Nations General Assembly Citation1948).

The right to health is entrenched in Article 12 of the ICESCR, which states that everyone has the right “to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.” State parties should take steps to achieve the full realization of this right, including “the improvement of all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene” (2(b)) and “the prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases (2(c); United Nations General Assembly Citation1966b).

The wide availability of HHPs has a major impact on the right to health, with significant public health consequences when nonfatal self-poisonings result in physical and mental health harm to individuals. In nonfatal self-poisoning (attempted suicide), which is considerably more frequent than completed suicide, pesticide poisoning results in temporary or permanent disability and high healthcare costs (Bertolote et al. Citation2006). Data from Sri Lanka show substantial public health costs of treating self-poisoned patients, with costs higher if patients are placed in intensive care units or transferred to secondary hospitals, which is frequent with serious pesticide poisoning cases (Wickramasinghe, Steele, Dawson, Dharmaratne, Gunawardena, Senarathna, De Silva, Wijayaweera, Eddleston, and Konradsen Citation2009).

The right to health is impacted when a person is not able to receive the necessary mental health or other health services, poisoning treatment and follow up after the incident. The duty to protect imposes on states an obligation to protect people from discrimination by third parties, such as refusal of healthcare and stigmatization of people who survive suicide and their families. It includes ensuring that third parties provide adequate information and safety measures with regard to pesticide use, label clarity, and application standards, among others.

The right to information

The United Nations and regional intergovernmental organizations have emphasized the importance of information in the area of the environment (United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment Citation1994). Article 19 of the UDHR and Article 19.2 of the ICCPR state that the right to freedom of expression includes freedom to seek, receive, and impart information (United Nations General Assembly Citation1948, Citation1966a). The right to information, as developed further by the UN agencies, requires that information be relevant and comprehensible, that it be provided in a timely manner, and that the procedures to obtain information be simple. It includes the right to be informed, even without a specific request, and “imposes a duty on Governments to collect and disseminate information and to provide due notice of significant environmental hazards” (United Nations General Assembly Citation1948, Citation1966a).

It has been long observed that the majority of small-holder farmers in LMICs possess little information about the toxicity, correct application, and hazards associated with pesticide use (Mengistie, Mol, and Oosterveer Citation2017). It has been argued that in many LMICs, poverty and illiteracy make safe use of HHPs impossible. Pesticide industry labeling practices are inconsistent, incomplete, vastly different in high-income countries and LMICs, and serve mainly as detractors from legal challenges of negligence and malpractice directed at the industry (Rother Citation2018).

Although the use of pesticides for suicide does not require reading the label, information on toxicity as well as implications and consequences of poisoning may deter people from using them in agriculture. The often-complicated nature of pesticide labels leaves end users in LMICs unable to fully comprehend and use the information on the labels (Rother Citation2018). One 2014 study showed that only 8 percent of 220 Ethiopian vegetable farmers were able to correctly read and comprehend the information on pesticide label (Mengistie et al. Citation2017). Another study showed that labels of all six products sold by Bayer and Syngenta in the Punjab region of India were lacking in various essential aspects of clarity or missing required information (European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights Citation2015).

The right to remedy

If alleged violations of human rights as a result of pesticide self-poisoning are not investigated according to domestic and international standards, it constitutes a violation of the right to remedy. The right to remedy is based on the principle of accountability and is enshrined in Article 8 of the UDHR, which states that “everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunal for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law” (United Nations General Assembly Citation1948). Article 2 of the ICCPR states that each state party has to ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms are violated shall have an effective remedy (United Nations General Assembly Citation1966a).

There are reports of victims of highly hazardous pesticide poisoning who, after many years of efforts, still have no access to justice and no effective remedy, with perpetrators of violations relating to toxic pesticides not held accountable (United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Implications for Human Rights of the Environmentally Sound Management and Disposal of Hazardous Substances and Wastes [Special Rapporteur on Hazardous Substances and Wastes] Citation2018). To mention just one case, 24 school children in the town of Tauccamara in the Peruvian Andes died after drinking a milk substitute contaminated with the HHP methyl parathion (Pesticide Action Network North America Citation2005). A Peruvian Congressional Investigative Subcommittee concluded that there is significant evidence of responsibility of the business and the country’s Ministry of Agriculture (Rosenthal Citation2003). The state government and the business (Bayer) refused to cooperate with the decision and provide compensation, despite efforts since 1999 by activists and the families of the children.

Non-discrimination

The wide availability of HHPs that people in crisis may use to harm themselves affects mostly people in low-income agricultural societies. As the UN Special Rapporteur on Hazardous Substances and Wastes (Citation2017) pointed out: “The adverse impacts of toxins on the poor, the young, older persons, minorities, indigenous peoples and other vulnerable groups are unequal and different genders are affected in different ways.”

Poor and disadvantaged people and minorities are affected by pesticide self-harm more profoundly because they live in rural areas, lack choice of other employment options, have unimpeded access to pesticides, and lack literacy skills to understand the risks associated with HHPs. The negative effect on the vulnerable groups is even more evident when combined with poor access to information and awareness of the risks associated with pesticide use, and adverse social and economic conditions. LMIC governments are often ill-equipped to meet the general health and mental health needs of their populations, even more so in the poorer agricultural areas (International Labour Organization Citation2015; Knipe, Williams, Hannam-Swain, Upton, Brown, Bandara, Change, and Kapur Citation2019). Services are scarce and, where they do exist, difficult to access and often underresourced. In the situation of a mental health crisis, counseling and medical treatment are needed but are often not available in the rural agricultural communities where most pesticide self-poisonings occur (Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts, Posada-Villa, Gasquet, Kovess, Lepine, Angermeyer, Bernert, De Girolamo, Morosini, Polidori, Kikkawa, Kawakami, Ono, Takeshima, Uda, Karam, Fayyad, Karam, Mneimneh, Medica-Mora, Borges, Lara, De Graaf, Ormel, Gureje, Shen, Huang, Zhang, Alonso, Haro, Vilagut, Bromet, Gluzman, Webb, Kessler, Merikangas, Anthony, Von Korff, Wang, Brugha, Aguilar-Gaziola, Lee, Heeringa, Pennell, Zaslavsky, Uston, and Chatterji Citation2004). People living in rural areas may have limited options when seeking mental health help as well as remedy and counseling in cases of domestic abuse or conflict (Vijayakumar Citation2017).

Globally, men die of suicide more than women, but in LMICs, women are impacted by suicide more than in HICs (World Health Organization Citation2014). The global male-to-female ratio for completed suicides shifts from 3.5 in HICs to 1.6 in WHO South-East Asia region (World Health Organization Citation2014). This is especially relevant for young women in Asian countries, as suicide rather than maternal-related issues is the single leading cause of death among women of reproductive age (Marahatta, Samuel, Sharma, Dixit, and Shrestha Citation2017). Being female is a risk factor for depression and anxiety disorders due to lack of empowerment, educational opportunities, and cultural norms restricting self-expression, space, and choice (Marahatta et al. Citation2017).

Even more, when low-income vulnerable agricultural communities with lack of access to healthcare and other public health interventions have wide access to toxic substances they cannot use safely, these communities are placed in a situation of double vulnerability. As the Special Rapporteur on Hazardous Substances and Wastes (Citation2017: 5) noted, “[in] addition to double standards of protection within countries, there are double standards of protection between countries, particularly between developing and industrialised countries, which are often exploited by businesses with global supply and value chains. The transfer of toxic production and disposal processes to the marginalized or the less fortunate is of grave concern.”

Business obligations

Within the human rights paradigm, states are the ultimate duty-bearers in relation to the obligation to protect human rights. However, other actors also have responsibilities regarding the promotion and protection of human rights. Pesticide manufacturers are infringing on the rights to health and life by making available and promoting the use of highly hazardous substances that are likely to harm health and cause loss of life, inadequately educating farmers about their proper use and associated harms, and polluting water and contaminating food with chemicals (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Citation2011).

Some pesticide manufacturers are known to export HHPs banned in their own countries of domicile to lower-income countries, usually LMICs with weaker monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. The examples include paraquat—a highly toxic weedicide chemical with a case fatality over 40 percent, when less than a mouthful of the ingested substance could lead to death. Paraquat is prohibited for use in the European Union and China but is produced by pesticide companies in these jurisdictions and exported to other countries (Public Eye Citation2020; Market Insider Citation2018). Frequently, paraquat is exported to LMICs, where poorly educated farmers suffer harms to health and loss of life as a result of its use. The other example is profenofos, an insecticide prohibited for use in Switzerland due to its harmful effect on human health and the environment but that is produced in this country for export (Public Eye Citation2020). In response to the critique of double standards, pesticide-producing companies have insisted on the freedom of choice of importing countries to purchase products they deem necessary for local agriculture. However, importing LMICs may lack capacity to assess potential harms to health and lives of their populations, may have lower enforcement standards, and may not be able to impose standards of protection available in HICs. It is reasonable to assume that populations in LMICs may encounter higher risk of exposure to HHPs and thus experience more profound adverse effects of HHPs than those producing them in HICs.

When HHP manufactures accept the need for protection from high toxicity of their products, they emphasize the importance of following the label in relation to the mode and frequency of use, wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), and avoiding use of their products for other than recommended purposes. Usage not according to these terms is labeled “misuse” and its consequences are blamed on the farmers. The concept of misuse is shifting the blame from businesses to farmers when, in real circumstances, the chemical could never have been used safely by small-scale farmers in LMICs (Eddleston and Gunnell Citation2020).

In recommending following the label and the use of PPE, pesticide businesses select the wrong form of prevention in the hierarchy of hazard controls. In the hierarchy of hazard controls, “elimination” (physically removing the hazard) precedes other methods, such as “substitution” (replacing the hazard), “engineering controls” (isolate people from the hazard), “administrative controls” (change the way people work), and the least effective PPE (protect the worker with personal protective equipment). Thus, businesses rely on the easiest and least effective form of prevention of exposure. The use of PPE equipment has proven to be ineffective and unpractical in subtropical climates where most LMICs are situated. This rejection of the hierarchy of hazard controls shows a failure in fulfilling the companies’ responsibility to prevent human rights violations (Eddleston and Gunnell Citation2020).

Another recommendation of pesticide companies to minimize harms from usage of their products is a “safe use and storage” approach. It advises farmers to store their pesticides securely, reducing access to toxic substances at times of stress by providing lockable storage. A randomized controlled trial including 223,000 people in 53,000 Sri Lankan households demonstrated that improved household storage of pesticides is ineffective in resource-poor, small-scale LMIC farming communities (Pearson et al. Citation2017; World Health Organization Citation2016). Studies in China showed that only 4 percent to 13 percent of households still used community pesticide storage after three years (World Health Organization Citation2016). The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations does not recognize the concept of safe use and storage, and removed these terms from its International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management at its 2014 revision (Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization Citation2014; World Health Organization Citation2016).

The responsibility of businesses to protect human rights is detailed in the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights developed by the United Nations. According to the principles, business enterprises should not only respect human rights but also avoid infringing on the human rights and address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved. Businesses’ responsibility requires that they seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products, or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts. In order to identify and prevent the adverse human rights impact, businesses should carry out human rights due diligence, including assessing actual and potential human rights impacts, integrating and acting on the findings, tracking responses, and communicating how impacts are addressed (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Citation2011).

Pesticide regulation as a solution to self-poisoning suicides

Pesticide legislation was developed after the introduction of pesticides in everyday life. In it, states recognized the need to protect life and health by using legislation to restrict access by the general population to the most toxic substances, such as highly hazardous pesticides or rodent-control products. Typical protection measures have involved requiring sales of restricted substances to take place only between buyers and sellers with licences (backed by training, certification, and similar controls), restricting the amounts supplied, and requiring such restricted substances to be kept locked away with their sales and use recorded (i.e., the “Poisons Act” of 1972 in the United Kingdom).

Legislative controls on pesticides were historically limited mainly to voluntary schemes, with legal restrictions or bans applying to only the most toxic substances (as determined by their hazardous properties), with some few pesticides falling under “poisons rules” controls.

Ongoing measures being advocated for or implemented (by states or other actors) to improve the health and safety of agricultural workers exposed to pesticides are, for example, improvements in understanding of pesticide labels (Rother Citation2018), training such as FAO's Farmer Field Schools, and improved access to PPE and other aspects of pesticides management (Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organisation 2014). Although worthwhile in themselves, they will not address the problem of pesticide suicides. Legislative restrictions on HHPs have been shown to be the most effective in reducing pesticide suicide rates. These restrictions are implemented on the national level in the form of bans on certain pesticides, restrictions on their use to licensed professionals, bans on imports and sales, and stricter rules for pesticide registration. Taking into account the fact that substances may be registered under different names in different countries, each country needs to collect information on what HHPs are registered and used in the country in order to understand which require stricter rules or ban.

Supranational control of pesticides could be helpful in regulating HHPs as it pulls scarce resources and technical expertise together to adopt a regional approach to pesticide regulation. Such regional systems exist, for example, in West Africa (Food and Agriculture Organization Citation2017) and the European Union (European Union Citation2020). The EU Pesticide Database, among others, provides overall guidance on registration, sale, usage, and the like. Whereas regional regulation may be considered effective, international regulation of pesticides and other chemicals harmful to health and environment has been unable to provide protection to those who need it most.

International regulations on pesticide management include chemical conventions such as the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade, and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (United Nations General Assembly Citation1998; United Nations General Assembly Citation2001). The Rotterdam Convention—the only international treaty that could restrict HHPs usage for the protection of health and lives from self-poisoning—avoids the discussion of pesticide suicides, terming it “misuse” and specifically excluding it from its remit. The choice to blame suicide on pesticide misuse and persons’ actions rather than on the introduction of these toxic compounds to rural villages, thus excluding it from the possible protection in the international convention, has negatively impacted suicide prevention in LMICs tremendously.

It is currently national regulation that is most effective in preventing pesticide suicides (Gunnell et al. Citation2017). Many LMICs developed pesticide management statues in the 1980 and the 1990s and are now starting to update them.Footnote7 In the new statues, it is essential to acknowledge the problem of pesticide suicide and to establish principles of stricter pesticide regulation, including a ban on all HHPs and, ultimately, a human rights-based approach to pesticide control.

The need for a human rights-based approach

In the case of suicide prevention and pesticide control, the indivisibility of human rights is particularly relevant, when the right to life, health, information, remedy, clean environment, water, and safe labor standards come together to support the need for stricter pesticide regulation and ultimately for the phasing out of HHPs.

The negative impact of pesticide use on human rights, health, and lives of vulnerable individuals makes a strong case for the application of a human rights-based approach to pesticide management. A human rights-based approach is a conceptual framework that is based on human rights standards and is designed to promote and protect human rights. In the case of a human rights approach to pesticide management, it would analyze inequalities at the heart of the pesticide management regime and redress discriminatory practices and unjust distributions of power. Under this approach, legislation and policies would be crafted mindful of human rights and the potential negative consequences of the legislation on vulnerable persons and groups, with principles and standards derived from international human rights treaties guiding policy development (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Citation2006; World Health Organization Citation2009b).

Applying a human rights-based approach to pesticide management would mean that the full realization of human rights in relation to pesticide use is seen as one of the goals of pesticide management. A human rights-based approach becomes relevant in countering discriminatory practices inherent in pesticide regulations and the operations of the international pesticide industry. Being at the center of all pesticide regulations, guiding the development of pesticide management policies and the interpretation of states’ national laws and international rules on pesticide management would allow better protection of human rights and the health of vulnerable rural populations.

The human rights-based approach would complement work on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are based on human rights. In fact, rapidly reducing and progressively eliminating exposure to toxic chemicals hazardous to lives, health, and the environment is essential not only for the protection of human rights and dignity but also for achieving the SDGs (United Nations General Assembly Citation2015). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and 17 Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 2015 include goals and targets directly related to addressing toxic chemicals, including pesticide poisoning, and prevention of suicide. Broadly speaking, all SDGs are affected by pesticide self-poisoning, but the most relevant and directly related is SDG 3 on good health and well-being.

SDG 3 aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all people, at all ages. This goal includes target 3.4: “[T]o promote mental health and well-being and reduce mortality from non-communicable diseases by one third by 2030” Within Target 3.4, suicide rates are proposed as indicators of progress (3.4.2). The SDG also include target 3.9 ‘to substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination by 2030’ (United Nations General Assembly Citation2015).

In order to effectively address the problem of suicide, the human rights-based approach to pesticide management and work directed at achieving the SDGs needs to complement other long-term suicide prevention interventions and methods, such as improving healthcare and support, gender-sensitive suicide prevention approaches, protection from domestic violence and familial abuse, and promotion of state and community interventions aimed at mental health support and coping strategies. The human-rights based approach having ultimate interests of a person at its heart will help guide state response to this problem in the most effective way.

Conclusion

In this article we have discussed the multiple ways in which pesticide suicides undermine human rights. Universality and indivisibility of human rights are particularly relevant in the case of suicide prevention and pesticide control, as rights such as the right to life, health, information, remedy, and equality come together to support the need for stricter pesticide regulation and ultimately for phasing out HHPs.

The ban of HHPs and their substitution with safer alternatives for crop protection is imperative to better protect, realize, and respect human rights; achieve sustainable development goals; and protect public health. Employing the human rights approach to pesticide management means phasing out HHPs not only to protect environment and ensure food safety but to protect human rights and save lives. One current priority is to generate a dialogue about pesticide suicides among populations in situations of vulnerability and the responsibility of states to prevent it. A clear timeline for the phase-out of HHPs and their substitution with safer alternatives is necessary on national, regional, and global levels. In addition to the recognition and reiteration of the state’s obligation to prevent pesticide suicides globally, the pesticide industry needs to take a bigger responsibility for the harmful effects of the HHPs they manufacture.

Acknowledgments

The Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention is funded by an Incubator Grant from the Open Philanthropy Project Fund, an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation, on the recommendation of GiveWell, USA. The authors would like to thank Professor Bernard Duhaime, Faculty of Law and Political Science at the University of Quebec in Montreal, and chair-rapporteur of the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, for his invaluable insight and support. We are especially grateful to Professor Brian Mishara, director of the Centre for Research and Intervention on Suicide, Ethical Issues, and End-of-Life Practices (CRISE), University of Quebec in Montreal, for comments and suggestions. We are indebted to Dr. Richard Brown, WHO, for sharing his experience on pesticide management and legislation. We thank Dr. Lovleen Bhullar, research fellow at the School of Law of the University of Edinburgh for edits. We would like to thank Baskut Tuncak, the UN Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes, and Hilal Elver, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food for advice and encouragement.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Leah Utyasheva

Leah Utyasheva holds an LL.M. in Comparative Constitutional Law from the Central European University, Budapest, and a PhD in Human Rights Law from the University of Newcastle, United Kingdom. She has worked in the area of human rights and rule of law for more than 15 years. She is currently a policy director for the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention, University of Edinburgh.

Michael Eddleston

Michael Eddleston is professor of clinical toxicology in the Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutics Unit of the University of Edinburgh, and consultant physician at the National Poisons Information Service, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. He trained in medicine at Cambridge and Oxford, with an intercalated PhD at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, and the University of Cambridge. His research aims to reduce deaths from pesticide and plant self-poisoning in rural Asia, a cause of as many as 200,000 premature deaths each year and a top three global means of suicide. To do this, he performs clinical trials in South Asian district hospitals to better understand the pharmacology and effectiveness of antidotes and community-based controlled trials to identify effective public health interventions. He has recently established the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention at the University of Edinburgh to drive research into and implementation of pesticide regulation (www.centrepsp.org).

Notes

1 Highly hazardous pesticides refer to pesticides that are acknowledged to present particularly high levels of acute or chronic hazards to health or environment, according to internationally accepted classification systems such as the WHO or Globally Harmonized System of Classification (GHS), or their listing in relevant binding international agreements or conventions. In addition, pesticides that appear to cause severe or irreversible harm to health or the environment under conditions of use in a country may be considered to be and treated as highly hazardous (Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization Citation2016).

2 Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY) is a metrics quantifying the burden of disease from mortality and morbidity. One DALY is one lost year of “healthy life” (World Health Organization Citation2018a).

3 The majority of the countries that adopted criminal punishment for attempted suicide do not prosecute or punish suicide attempters. The 2016 study concluded that countries that punish attempted suicide do not have lower suicide rates than other countries (Mishara and Weisstaub Citation2016).

4 Other interpretative comments by the UN agencies do not specifically pay attention the subject of suicide. Concluding observations of the Human Rights Committee concerning Ecuador of 1998 is a notable exception. In this document, the committee reflected on the issue of high numbers of suicides of young women that appeared to be related to the prohibition of abortion. The committee found this situation incompatible with Article 6 and recommended positive action (Concluding Observation: Ecuador (1998), para. 11).

5 In Keenan v. United Kingdom (European Court of Human Rights Citation2001) and Renolde v. France (2008) in the situation of mentally ill prisoners, the Court held that the state bears a duty to adequately protect life of detainees under their control from self-inflicted harm, including suicide. In Haas v. Switzerland (European Court of Human Rights Citation2011), the Court noted that Article 2 creates for the authorities a duty to protect vulnerable persons, even against actions by which they endanger their own lives.

6 Usually, state instructions on physician-assisted suicide suggest doctors assist suicide as “a last resort when no cure is available for the patient’s terminal or chronically unacceptable condition, and when the diagnosis has been confirmed by another specialist who has treated the patient himself. Under these conditions the doctor must choose between the duty to preserve life and the duty as a doctor to do everything possible to relieve the unbearable suffering, without prospect of improvement, of a patient committed to his care” (Tiensuu Citation2015: 261).

7 Prior to 1987, Nepal and Papua New Guinea did not have pesticide legislation. Burma and China did not have it until 1992. The 1993 FAO survey indicated that about 25 percent of LMICs lacked any kind of legislation to govern the distribution and use of pesticides. Additionally, 76 percent of countries in Africa lacked pesticide control laws (Schaefers Citation1996).

References

- ALLEN, Neil. (2013) The right to life in a suicidal state. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 36(5), 350–357. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.09.002

- BERTOLOTE, José M., FLEISCHMANN, Alexandra, BUTCHART, Alexander, and BESBELLI, Nida. (2006) Suicide, suicide attempts and pesticides: A major hidden public health problem. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 84(4), 260–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.06.030668

- CARROLL, Robert, METCALFE, Chris, and GUNNELL, David. (2014) Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 9(2), e89944. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089944

- CHA, Eun Shil, CHANG, Shu Sen, GUNNELL, David, EDDLESTON, Michael, KHANG, Young-Ho, and LEE, Won Jin. (2016) Impact of paraquat regulation on suicide in South Korea. International Journal of Epidemiology, 45(2), 470–479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv304

- CHAPMAN, Audrey, and CARBONETTI, Benjamin. (2011) Human rights protections for vulnerable and disadvantaged groups: The contributions of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Human Rights Quarterly, 33(3), 682–732. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2011.0033

- CHOWDHURY, Fazle Rabbi, DEWAN, Gourab, VERMA, Vasundhara R., KNIPE, Duleeka W., ISHA, Ishrat Tahsin, FAIZ, M. Abdul, GUNNELL, David J., and EDDLESTON, Michael. (2018) Bans of WHO Class I pesticides in Bangladesh—Suicide prevention without hampering agricultural output. International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(1), 175–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx157

- CONNER, Kenneth R., PHILLIPS, Michael R., MELDRUM, Sean, KNOX, Kerry L., ZHANG, Yanping, and YANG, Gonghuan. (2005) Low-planned suicides in China. Psychological Medicine, 35(8), 1197–1204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329170500454x

- COUNCIL OF EUROPE. (1950) European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, as amended by Protocols Nos. 11 and 14. In ETS 5, Council of Europe (ed.) (Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe).

- DEMYTTENAERE, Koen, BRUFFAERTS, Ronny, POSADA-VILLA, Jose, GASQUET, Isabelle, KOVESS, Viviane, LEPINE, Jean Pierre, ANGERMEYER, Matthias C., BERNERT, Sebastian, DE GIROLAMO, Giovanni, MOROSINI, Pierluigi, POLIDORI, Gabriella, KIKKAWA, Takehiko, KAWAKAMI, Norito, ONO, Yutaka, TAKESHIMA, Tadashi, UDA, Hidenori, KARAM, Elie G., FAYYAD, John A., KARAM, Aimee N., MNEIMNEH, Zeina N., MEDINA-MORA, Maria Elena, BORGES, Guilherme, LARA, Carmen, DE GRAAF, Ron, ORMEL, Johan, GUREJE, Oye, SHEN, Yucun, HUANG, Yueqin, ZHANG, Mingyuan, ALONSO, Jordi, HARO, Josep Maria, VILAGUT, Gemma, BROMET, Evelyn J., GLUZMAN, Semyon, WEBB, Charles, KESSLER, Ronald C., MERIKANGAS, Kathleen R., ANTHONY, James C., VON KORFF, Michael R., WANG, Phillp S., BRUGHA, Traolach S., AGUILAR-GAXIOLA, Sergio, LEE, Sing, HEERINGA, Steven, PENNELL, Beth Ellen, ZASLAVSKY, Alan M., USTUN, T. Bedirhan, and CHATTERJI, Somnath. (2004) Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of the Americal Medical Association, 291(21), 2581–2590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.21.2581

- EDDLESTON, Michael, KARUNARATNE, Ayanthi, WEERAKOON, Manjula, KUMARASINGHE, Subashini, RAJAPAKSHE, Manjula, SHERIFF, M. H. Rezvi, BUCKLEY, Nick A., and GUNNELL, David. (2006) Choice of poison for intentional self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka. Clinical Toxicology, 44(3), 283–286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650600584444

- EDDLESTON, Michael, and GUNNELL, David. (2020) Preventing suicide through pesticide regulation. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(1), 9–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30478-X

- EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR CONSTITUTIONAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS. (2015) Ad hoc Monitoring Report: Claims of (non-)adherence by Bayer CropScience and Syngenta to the Code of Conduct Provisions on Labelling, Personal Protective Equipment, Training, and Monitoring. [Online]. Available: https://www.business-humanrights.org/it/node/129031 [22 June 2020].

- EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS. (2001) Keenan v. United Kingdom.

- EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS. (2011) Haas v. Switzerland.

- EUROPEAN UNION. (2020) The European Union Pesticide Database. [Online]. Available: http://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/public/?event=homepage&language=EN [22 June 2020].

- FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION. (2017) Implementing the Rotterdam Convention through Regional Collaboration in West Africa. The Example of the Permanent Interstates Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel (CILSS) (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization).

- FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION and WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. (2014) The International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization).

- FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION and WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. (2016) Guidelines on Highly Hazardous Pesticides (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization).

- GUNNELL, David, EDDLESTON, Michael, PHILLIPS, Michael R., and KONRADSEN, Flemming. (2007) The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: Systematic review. BMC Public Health, 7(1), 357. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-357

- GUNNELL, David, FERNANDO, Ravindra, HEWAGAMA, Medhani, PRIYANGIKA, W. D., KONRADSEN, Flemming, and EDDLESTON, Michael. (2007) The impact of pesticide regulations on suicide in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(6), 1235–1242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dym164

- GUNNELL, David, KNIPE, Duleeka, CHANG, Shu-Sen, PEARSON, Melissa, KONRADSEN, Flemming, LEE, Won Jin, and EDDLESTON, Michael. (2017) Prevention of suicide with regulations aimed at restricting access to highly hazardous pesticides: A systematic review of the international evidence. Lancet Global Health, 5(10), e1026–e1037. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30299-1

- HEMENWAY, David, BARBER, Catherine, and MILLER, Matthew. (2010) Unintentional firearm deaths: A comparison of other-inflicted and self-inflicted shootings. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(4), 1184–1188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2010.01.008

- HO, Angela Onkay. (2014) Suicide: Rationality and responsibility for life. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(3), 141–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900305

- INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION. (2015) Global evidence on inequalities in rural health protection: New data on rural deficit in health coverage for 174 countries. In ESS- Extension of Social Security, X. Scheil-Adlung (ed.) (Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office).

- JEYARATNAM, J. (1990) Acute pesticide poisoning: A major global health problem. World Health Statistics Quarterly, 43(3), 139–144.

- KARUNARATHNE, Ayanthi, GUNNELL, David, KONRADSEN, Flemming, and EDDLESTON, Michael. (2020) How many premature deaths from pesticide suicide have occurred since the agricultural Green Revolution? Clinical Toxicology, 58(4), 227–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2019.1662433

- KNIPE, Duleeka, CHANG, Shu-Sen, DAWSON, Andrew, EDDLESTON, Michael, KONRADSEN, Flemming, METCALFE, Chris, and GUNNELL, David. (2017) Suicide prevention through means restriction: Impact of the 2008-2011 pesticide restrictions on suicide in Sri Lanka. PLOS ONE, 12(3), e0172893.

- KNIPE, Dulleka, GUNNELL, David, EDDLESTON, Michael. (2017) Preventing deaths from pesticide self-poisoning-learning from Sri Lanka’s success. Lancet Global Health, 5(7), e651–e652. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30208-5

- KNIPE, D., WILLIAMS, A. Jess, HANNAM-SWAIN, Stephanie, UPTON, Stephanie, BROWN, Katherine, BANDARA, Piumee, CHANG, Shu-Sen, and KAPUR, Nav. (2019) Psychiatric morbidity and suicidal behaviour in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 16(10), e1002905. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002905

- LONDON, Leslie, FLISHER, Alan J., WESSELING, Catharina, MERGLER, Donna, and KROMHOUT, Hans. (2005) Suicide and exposure to organophosphate insecticides: Cause or effect? American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 47(4), 308–321.

- MANUWEERA, Gamini, EDDLESTON, Michael, EGODAGE, Samitha, and BUCKLEY, Nick A. (2008) Do targeted bans of insecticides to prevent deaths from self-poisoning result in reduced agricultural output? Environmental Health Perspectives, 116(4), 492–495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.11029

- MARAHATTA, Kedar, SAMUEL, Reuben, SHARMA, Pawan, DIXIT, Lonim, and SHRESTHA, Bhola. (2017) Suicide burden and prevention in Nepal: The need for a national strategy. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health, 6(1), 45–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/2224-3151.206164

- MARKET INSIDER. (2018) Market Research on Paraquat in China. [Online]. Available: https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/market-research-on-paraquat-in-china-1027514540 [20 March 2020].

- MENGISTIE, Belay T., MOL, Arthur P. J., and OOSTERVEER, Peter. (2017) Pesticide use practices among smallholder vegetable farmers in Ethiopian Central Rift Valley. Environment, Development, and Sustainability, 19(1), 301–324. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9728-9

- MEW, Emma J., PADMANATHAN, Prianka, KONRADSEN, Flemming, EDDLESTON, Michael, CHANG, Shu-Sen, PHILLIPS, Michael R., and GUNNELL, David. (2017) The global burden of fatal self-poisoning with pesticides 2006–15: Systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 219, 93–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.002

- MEYER, Armando, KOIFMAN, Sergio, KOIFMAN, Rosalina Jorge, MOREIRA, Josino Costa, DE REZENDE CHRISMAN, Juliana, and ABREU-VILLAÇA, Yael. (2010) Mood disorders hospitalizations, suicide attempts, and suicide mortality among agricultural workers and residents in an area with intensive use of pesticides in Brazil. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, 73(13–14), 866–877. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15287391003744781

- MISHARA, Brian, and WEISSTUB, David. (2005) Ethical and legal issues in suicide research. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 28(1), 23–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2004.12.006

- MISHARA, Brian, and WEISSTUB, David. (2016) The legal status of suicide: A global review. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 44(January-February), 54–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2015.08.032

- MYUNG, Woojae, LEE, Geung-Hee, WON, Hong-Hee, FAVA, Maurizio, MISCHOULON, David, NYER, Maren, KIM, Doh Kwan, HEO, Jung-yoon, and JEON, Hong Jin. (2015) Paraquat prohibition and change in the suicide rate and methods in South Korea. PloS one, 10(6), e0128980. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128980

- ORGANISATION OF AFRICAN UNITY. (1981) African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights (“Banjul Charter”) (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Organisation of African Unity).

- ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES. (1969) American Convention on Human Rights, “Pact of San Jose” (San José, Costa Rica: Organization of Americal States).

- PEARSON, Melissa, METCALFE, Chris, JAYAMANNE, Shaluka, GUNNELL, David, WEERASINGHE, Manjula, PIERIS, Ravi, PRIYADARSHANA, Chamil, KNIPE, Duleeka W., HAWTON, Keith, DAWSON, Andrew H., BANDARA, Palitha, DESILVA, Dhammika, GAWARAMMANA, Indika, EDDLESTON, Michael, and KONRADSEN, Flemming. (2017) Effectiveness of household lockable pesticide storage to reduce pesticide self-poisoning in rural Asia: A community-based, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 390(10105), 1863–1872. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31961-X

- PESTICIDE ACTION NETWORK NORTH AMERICA. (2005) Tribunal Investigates Children’s Pesticide Poisoning. [Online]. Available: http://www.panna.org/legacy/panups/panup_20051209.dv.html [22 June 2020].

- PUBLIC EYE. (2020) Toxic exports: A Syngenta Pesticide Banned in Switzerland Pollutes Drinking Water in Brazil. [Online]. Available: https://www.publiceye.ch/en/media-corner/press-releases/detail/toxic-exports-a-syngenta-pesticide-banned-in-switzerland-pollutes-drinking-water-in-brazil [18 June 2020].

- ROSENTHAL, Erika. (2003) The tragedy of Tauccamarca: A human rights perspective on the pesticide poisoning deaths of 24 children in the Peruvian Andes. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 9(1), 53–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/107735203800328821

- ROTHER, Hanna-Andrea. (2018) Pesticide labels: Protecting liability or health? Unpacking ‘misuse’ of pesticides. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health, 4(August), 10–15.

- SCHAEFERS, George A. (1996) Status of pesticide policy and regulations in developing countries. Journal of Agricultural and Urban Entomology, 13(3), 213–222.

- TIENSUU, Paul. (2015) Whose right to what life: Assisted suicide and the right to life as a fundamental right. Human Rights Law Review, 15(2), 251–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngv006

- ULRICH, Michael. (2019) A public health approach to gun violence, legally speaking. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 47(2_suppl), 112–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110519857332

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY. (1948) Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Universal Declaration Declaration - 217 A(III) (New York, NY: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY. (1966a) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. In Treaty Series (vol. 999) (Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY. (1966b) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. In Treaty Series (vol. 993) (Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY. (1998) Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade. In Treaty Series (vol. 2244) (Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY. (2001) Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. In Treaty Series (vol. 2256) (Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY. (2012) Final Study of the Human Rights Council Advisory Committee on the Advancement of the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas. UN Doc. A/HRC/AC/8/6 (Geneva, Switzerland: UN Human Rights Council).

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY. (2015) Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Transform Our World. [Online]. Available: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ [18 June 2020].

- UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE. (2018) ICCPR General Comment No. 36 on Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, on the Right to Life. UN Doc. CG 36 - CCPR/C/GC/36 (Geneva, Switzerland: UN Human Rights Committee).

- UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL. (2018) Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas. UN Doc. A/HRC/39/12 (Geneva, Switzerland: UN Human Rights Council).

- UNITED NATIONS OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS. (2006) Frequently Asked Questions on a Human Rights-based Approach to Development Cooperation. UN Doc. HR/PUB/06/8 (Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS. (2011) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, In Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy Framework.’ UN Doc. HR/PUB/11/04 (Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE ENVIRONMENT. (1994) Final Report to the UN (Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE IMPLICATIONS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND MANAGEMENT AND DISPOSAL OF HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES AND WASTES. (2017) Report on the Implications for Human Rights of the Environmentally Sound Management and Disposal of Hazardous Substances and Wastes. UN Doc. A/HRC/36/41 (Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE IMPLICATIONS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND MANAGEMENT AND DISPOSAL OF HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES AND WASTES. (2018) Report to the UN General Assembly. UN Doc. A/73/567 (New York, NY: United Nations).

- UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE RIGHT TO FOOD. (2017) Report to the UN Human Rights Council. UN Doc. A/HRC/34/48 (Geneva, Switzerland: UN Human Rights Council).

- VETHANAYAGAM, A. V. (1962) “Folidol” (Parathion) Poisoning. British Medical Journal, 2(5310), 986–987.

- VIJAYAKUMAR, Lakshmi. (2017) Challenges and opportunities in suicide prevention in South-East Asia. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health, 6(1), 30–33.

- VIJAYAKUMAR, Lakshmi. (2007) Suicide and its prevention: The urgent need in India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(2), 81–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.33252

- WICKRAMASINGHE, Kanchana, STEELE, Paul, DAWSON, Andrew, DHARMARATNE, Dinusha, GUNAWARDENA, Asha, SENARATHNA, Lalith, DE SIVA, Dhammika, WIJAYAWEERA, Kusal, EDDLESTON, Michael, and KONRADSEN, Flemming. (2009) Cost to government health-care services of treating acute self-poisonings in a rural district in Sri Lanka. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87(3), 180–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.08.051920

- WICKS, Elizabeth. (2010) The Right to Life and Conflicting Interests (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press).

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. (2009a) Guns, knives and pesticides: Reducing access to lethal means. In Series of Briefings on Violence Prevention: The Evidence (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization).

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. (2009b) A Human Rights-Based Approach to Health (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization).

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. (2014) Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization).

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. (2016) Safer Access to Pesticides for Suicide Prevention: Experiences from Community Interventions (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization).