Abstract

This article examines the academic discussion about human rights education for children and young people and argues that the current state of research does not provide sufficient support and guidance to nations, schools, and teachers in the establishment of human rights education in schools. The article’s aim is to add insights into how scholarly work may be contributing to the low uptake of human rights education in formal schooling. By drawing on educational children’s rights research and research on human rights education, three cardinal complications are identified; (1) that the main research fields that address education and rights do not seem to communicate, (2) that it is unclear what are the aims of human rights education are, and (3) that a curriculum for human rights education is missing. The cardinal complications are closely examined and discussed, and a middle ground is explored and progressively visualized.

Introduction

Recent experiences of war, terrorism, injustice, and intolerance, and worrying attempts to dismantle democracy, global friendship, and international cooperation illustrate the importance of people’s and societies’ resistance capacity. Human rights provide an ethical code for such resistance, and to strengthen a human rights culture, the education of children and young people has been identified as essential (Cassidy et al., Citation2014; Rinaldi, Citation2017; United Nations, Citation2006, Citation2011; Zembylas, Citation2017).

The world’s educational systems are therefore responsible for enabling the growing generations to understand the role that human rights play in our lives and the vitality of democratic regimes. This has been labeled “human rights education” (HRE), defined as “education about, through, and for human rights” (Gerber, Citation2008; Leung et al., Citation2011; Struthers, Citation2015; United Nations, Citation2011). Attitudes, values, and beliefs are shaped at an early age, and many argue that children therefore should be introduced to human rights in their initial school years (Lucas, Citation2009; Struthers, Citation2016). Despite strong support for HRE for children and young people, it does not seem to take place in schools as hoped for (Gerber, Citation2008; Lundy et al., Citation2012; Parker, Citation2018; Tibbitts & Kirschschläger, Citation2010). Several aspects in policy and practice have been identified that appear to hinder the realization of such education.

In this article, I will however focus on another matter that is negatively affecting the pace at which education for human rights is being introduced in schools—namely, the academic discussion about human rights education. Research is a significant factor in the construction of societal phenomena, such as HRE: The phenomenon is defined, central problem areas and their solutions are claimed, and the phenomenon is framed with a certain vocabulary. In this article, research itself is accordingly viewed as a central contributor to how HRE for children and young people is perceived and realized in wider society. I will argue that the current state of research does not provide sufficient support and guidance to nations, schools, and teachers in the establishment of HRE in schools. The ambition of the article is to provide an elaborated argument for why and around which matters experts from different research fields and positions need to start talking and listening to one another and start acting together. This is imperative to advance HRE in schools.

Education and rights

The connection between education and the strengthening of human rights was laid out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, Citation1948) and reiterated in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (United Nations, Citation1966) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989). The specific term “human rights education” was introduced by the United Nations in the mid-1990s (Coysh, Citation2017). Since then, a series of UN activities has been launched to define and refine what is meant by HRE, and to spur states to include HRE in their formal school systems. Research that examines HRE in formal schooling is limited, but available work confirms the indications in a UN evaluation (United Nations, Citation2010) that, if HRE occurs at all, it does not match the broad scope envisaged in the United Nations’ definition (Gerber, Citation2008; Struthers, Citation2015; United Nations, Citation2011).

One factor shown to hamper the realization of HRE in formal schooling is insufficient policy direction at the national level. Large differences have been demonstrated between countries’ national curricula in terms of how requirements for HRE are expressed, from being barely noticeable (Bron & Thijs, Citation2011) to being clearly expressed (Rinaldi et al., Citation2020). The incentives to teach about and for human rights, therefore, differ largely between nations (Gerber, Citation2008; Parker, Citation2018; Tibbitts & Kirschschläger, Citation2010). Some authors have connected this absence of explicit direction to an escalating questioning of human rights in wider society (Struthers, Citation2016; Tibbitts & Katz, Citation2017). Various voices have begun to construct human rights as controversial; the political right contests the legitimacy of human rights on the basis that the human rights system disregards national sovereignty and culture; the political left questions the value of the rights discourse by arguing that the human rights movement privileges a juridical perspective and takes little interest in actual human life. Voices from the Global South have criticized the human rights project for hegemonically imposing Western values onto local cultures. In a social landscape in which skepticism toward human rights is frequently voiced, politicians often hesitate to push for HRE and teachers may be reluctant to teach this area, as it is perceived to be contested and politically problematic (Rinaldi, Citation2017; Struthers, Citation2019).

In educational practice, issues identified as hindering the realization of HRE in school largely concern teachers’ knowledge and attitudes. First, teachers seem to be generally unaware that HRE exists and of the responsibility it places on nations, schools, and teachers (Tibbitts & Kirschschläger, Citation2010; Waldron & Oberman, Citation2016). Teachers’ knowledge about human rights appears to be insufficient (Çayır & Bağlı, Citation2011; Perry-Hazan & Tal-Weibel, Citation2020). To some extent, teacher education has been found to address children’s rights (Cassidy et al., Citation2014), and when asked about HRE, teachers tend to talk about children’s rights rather than human rights, and to refer to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989) rather than any general human rights treaties (Struthers, Citation2015; Zembylas et al., Citation2015). Second, human rights are conceived as a difficult and complex teaching area, one in which teachers will be required to simultaneously deal with facts, emotions, morality, and opinions. Because of the perceived complexity and sensitivity of the topic, teachers also hesitate to introduce the topic until the later school years (Bron & Thijs, Citation2011; Leung et al., Citation2011; Quennerstedt, Citation2019; Rinaldi, Citation2017).

Aims and outline

As indicated, earlier research has pointed out problematic areas in policy and practice as possible explanations for why HRE does not take place. The aim of this article is to add insights into how scholarly work may be contributing to the low uptake of HRE for children and young people in school. This is done by unfolding the following three cardinal complications in scholarly work that address children’s rights in education and school-based human rights education:

The main research fields that examine the intersection between education and rights do not seem to communicate. Thinking from these fields that could complement each other and strengthen school-based HRE is rarely brought together.

It is unclear what the main aim of HRE is. This constitutes a major barrier to the realization of HRE in schools.

There is no established idea about what the educational content of HRE is for specific school years and ages of children; a curriculum and an idea of progression are lacking, as is an educational conceptualization of the teaching and learning of human rights.

The cardinal complications have been formulated by drawing on educational children’s rights research and research on human rights education for children and young people in school. My reading has been extensive, but it should be noted that what I present is not a review of the literature. This is a literature-based argument that points out the key problems and a call for a new direction in the scholarly work on children’s and young people’s human rights education.

The main body of the article consists of a close examination of the cardinal complications. I scrutinize the ensuing problems and how they may impinge on the effectuation of HRE in schools. An additional objective is to take some first steps toward, if not a solution, at least a terrain for a solution. This is done by highlighting aspects that should be brought together to form what I call a middle ground. This middle ground offers a platform from which ideas about children’s and young people’s HRE can be further developed and eventually articulated. The exploratory search for such a middle ground will be pursued progressively throughout the article, and its central features are visualized in a series of figures that, step by step, fill the middle ground with substance. The article concludes with a tentative formulation of central topics for further academic elaboration that emerges from the amalgamation of ideas and thinking that signifies the middle ground.

The article approaches HRE as a global issue. No particular national context is in view, and research literature from a range of countries is used to build the argument. My analysis and suggestions also aim to transcend any national situation.

Cardinal complication #1: Rights education in school—between children’s rights research and HRE research

Research that intersects education and human rights can be found in different fields. A significant part of this research belongs to the field that can be labeled “educational children’s rights research.” A characteristic of this research is that the rights of the child are taken as a central starting point, and a view of children and young people as fully fledged rights holders is insisted on. Rights-oriented educational research is also conducted within the field of HRE research. There, education for human rights is the starting point, rather than a particular rights holder. In the following, I will argue that neither of these fields of study on their own provides an adequate ground for advancing and supporting children’s and young people’s human rights education in school. To elaborate on this claim, I will outline the central features and objectives of each research field, thereby displaying the differences between them, their respective vital contributions, and why the respective fields on their own do not suffice.

Educational children’s rights research

Children’s rights research within the field of education puts the child in the center of attention and approaches education and its institutions from an explicit child rights perspective. School is viewed as a setting in which children and young people are to be respected as complete rights holders in the present. Theorizing about children, childhood, and the child as a citizen, with strong references to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989), forms a foundation for the research. On this basis, children’s rights researchers examine educational institutions and situate responsibility with states, institutions, and professionals.

The research within the field is dominated by studies that have examined whether and how children’s rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989) are realized in school practice. A recent review of educational children’s rights research undertaken since the adoption of the convention (Quennerstedt & Moody, Citation2020) has confirmed the high frequency of implementation research shown in earlier reviews (Quennerstedt, Citation2011; Reynaert et al., Citation2009). Matters that are examined include how teachers view rights for children and whether the child’s rights are being upheld in school—concerning the latter, for example, if children with special needs or who have experienced forced migration (Alderson, Citation2018; Bačáková, Citation2011) are given equal access to quality education. The implementation research further demonstrates infringements of human rights principles in school, such as violence, bullying, discrimination, or transgression of the right to privacy (Perry-Hazan & Lambrozo, Citation2018). The aspect that is given the most attention, however, is how schools deal with children’s participation and influence. A large number of studies have examined whether and how rights within this area are upheld, and how schools work to let children give their views on matters, are listened to, and have real opportunities to influence their situation (Sargeant & Gillett-Swan, Citation2019; Theobald et al., Citation2011).

Quennerstedt and Moody (Citation2020) identified a paucity of studies that pose core educational/pedagogical questions in relation to children’s rights in education. The authors argued that the research questions that dominate educational children’s rights research are formulated from a legal perspective (e.g., How are rights implemented, respected, guaranteed, or promoted in educational settings?) or a sociological perspective (e.g., What inequalities can be found? How do children’s agency and status take shape? How is the power balance constituted?). This research has predominantly drawn on political/philosophical or rights theories, or sociological theorizing—for example, childhood studies. Educational or pedagogical theory has rarely been cited, and research questions that foreground teaching processes, learning processes, educational content, the pedagogical classroom situation, and so on have been infrequent. This meager attention to the core questions of education is a first problem within educational children’s rights research when investigating what HRE might be in school for children and young people.

A second problem is that connections to wider human rights research or references to general human rights treaties are weak. Human rights terminology is altogether infrequent; instead, children’s rights provide the prevailing terminology, and the main reference point is the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989). Rights research concerning children is thereby detached from the broader research into human rights. This separation, and the negative consequences of it, has been highlighted by several scholars (Cassidy et al., Citation2014; Quennerstedt, Citation2010; Struthers, Citation2015). Children’s rights researchers’ limited attention to human rights may shed light on why HRE has not generated a high degree of interest among educational children’s rights researchers or is even unknown to them.

In summary, the predominant perspective taken in educational children’s rights research has accentuated the full human value of the child and the practicing of rights here and now in schools. By privileging attention to the child as a rights holder, and by detailing how schools have dealt with a rights perspective on children and young people, the field makes a vital contribution. Two limitations of educational children’s rights research in relation to HRE are the lack of attention to core educational/pedagogical questions and the absence of human rights framing and terminology.

HRE research

HRE research has focused on the very issue of education for human rights, and human rights terminology has provided the central conceptual reference point. This research has raised and debated core educational questions, with frequent references to educational and pedagogical theorizing. The aims of HRE have been discussed (this will be thoroughly examined in the next section and therefore not further pursued here). Questions of pedagogy have been addressed, as choices of instruction methods are considered to be crucial to whether HRE will accomplish its purposes. Scholars who have engaged in discussions of educational methods for HRE have often drawn on theories of critical pedagogy. Teaching methods that center critical reflection and interactive and learner-centered activities, and that contain participatory and empowering processes in which learners practice human rights actions, have commonly been held forth as beneficial, or even necessary, in full-scale HRE (Heggart, Citation2012; Tibbitts & Kirschschläger, Citation2010; Zembylas, Citation2017).

In discussions of educational content in HRE, the importance of connecting the content to learners’ everyday lives has been emphasized. Research has shown that, too often, human rights teaching tends to focus on the “exotic”—rights for people far away, and rights violations in these places, are more frequently addressed than rights and rights transgressions in the children’s own context. Several authors have argued that the opposite approach should be taken, connecting human rights to learners’ own local situation (Lucas, Citation2009; Waldron & Oberman, Citation2016). Hands-on methodological support has also been offered, for example, in a collection of essays providing concrete examples of human rights education in classrooms (Katz & Spero, Citation2015). The research field accordingly has contributed rich, theoretically grounded support for the design and practice of HRE for children and young people.

However, the main body of HRE scholarly literature has been directed to arenas other than formal schooling. The limited research that has addressed school-based human rights education has primarily examined curricula and teachers’ understandings—the main results of this research have been mentioned earlier: large curricula variations between nations and teachers who are unaware or feel insecure and hesitate to teach human rights. Concrete HRE initiatives have tended to be small-scale, often driven by particularly enthusiastic teachers. Even when rights education is a required element of the curriculum, the actual classroom activities seem to be generally limited and weak (Gerber, Citation2008; Quennerstedt, Citation2019). Taken together, the findings of school-based studies indicate that HRE for children and young people is not a well-integrated feature of school teaching.

The main focus of HRE research is, instead, nongovernmental organization (NGO) projects and community activities to promote and further human rights knowledge. The participants in these initiatives are rarely children. Rather, the intra-field discussion seems mainly to have an adult learner in mind. For example, little consideration has been given to how the age of the learner might be significant for conceiving the purpose, content, or pedagogical design of HRE. With some exceptions, the implications of the learner being a child is therefore not a question the research field has engaged with when considering HRE. Equally, considerations of how HRE needs to be adapted to contextual factors—such as the character, role, and function of the setting in which it is to be undertaken—are also rare.

The main contribution of HRE research is that it has privileged core educational questions, and thereby elaborated on matters of aims, content, and pedagogy. That the field only sparsely has engaged in school-based HRE is a limitation: The absence of considerations of the effect of the learner’s age and the setting for the learning constitute therefore problematic voids in the research. Put briefly, in mainstream HRE scholarship, children have not been the main learners and school has not been the main setting for HRE.

A new space between research fields: A middle ground?

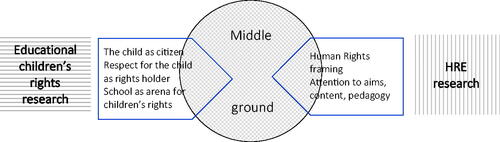

The exploration of educational children’s rights research and HRE research leads to the conclusion that neither of these fields alone can provide sufficient ground for advancing children’s and young people’s HRE in the school context. Both address important matters relating to HRE for children but overlook other central aspects. By bringing the contributions from the two fields together, some initial features of a middle ground can be discerned, as visualized in . When a view of the child as a full status rights holder to be respected and regarded as a citizen in school, as emphasized in educational children’s rights research, is blended with HRE research’s explicit human rights terminology and focused elaborations of processes and pedagogy, a new understanding of HRE for children and young people can emerge.

Even though HRE research has identified and discussed core educational issues, two aspects touched on above need further examination. First, in relation to one of the most basic educational questions—namely, the aim of education (i.e., Why should certain education take place at all?)—HRE scholarship has not provided sufficient clarity. Instead, notably differing ideas regarding the purpose of HRE are present in the literature. Second, and related to the question of purpose, is the limited attention to educational content demonstrated in the research. Concrete elaborations of the “what?” question (What should be taught and learned?) have been scarce, and educational content has not been discussed in relation to age and school levels. These two aspects constitute cardinal complications and will be addressed in the following two sections.

Cardinal complication #2: What does human rights education aim for?

It is not straightforward to understand what HRE is, as it overlaps with other curriculum areas, such as citizenship education, peace education, education for democracy, antiracist education, and intercultural education (Bajaj, Citation2011, Heggart, Citation2012; Tibbitts, Citation2002, Citation2017). Teachers’ confusion about how these differ has been demonstrated (Cassidy et al., Citation2014; Zembylas et al., Citation2015). Davies (Citation2010), for example, raised the essential question of whether HRE is an umbrella term for all these approaches or should be understood as a distinctive area alongside them. Tibbitts (Citation2014) argued that HRE is indeed something specific and accentuated two unique features. The first concerns the aim of education: Tibbitts highlighted that HRE is directed to the empowerment of learners to know and claim their rights. According to Tibbits, this objective goes beyond educating about values related to justice and the general participation ambition of citizenship education. Second, she pointed out that the close relation to the United Nations, international human rights law, and interstate political diplomacy gives HRE a unique backdrop. The HRE initiatives under UN leadership and actuation have prompted a holistic definition of and a global movement for HRE, which is not the case for the overlapping other curriculum areas. Not all scholars writing on the topic of HRE have distinguished as sharply as Tibbits between HRE and these other curriculum areas, however (Al-Daraweesh & Snauwaert, Citation2015; Bron & Thijs, Citation2011). Hence, scholarly and professional uncertainty about whether HRE is something specific or is largely the same thing as—for example, citizenship education or peace education—presents a difficulty.

A particular complexity arises from the lack of clarity concerning the ultimate objective of HRE. The aim of education is foundational in educational thinking and deliberation: All other considerations and choices follow from the aim. It is impossible to make choices about educational content or pedagogy if it is not clear what is to be attained. Since the mid-1900s, but even more so since the 1990s, HRE has developed into an important component in the wider human rights movement, driven mainly by the United Nations and NGOs (Russell & Suárez, Citation2017). These main actors view the ultimate aim of human rights education in different ways, disparities that are reflected in recent scholarly work on HRE.

Organizations’ differing views on the aim of HRE

Coysh (Citation2017) discussed how the United Nations’ engagement and discourse in recent decades have moved HRE from dwelling in the margins of international human rights activities to being a powerful idea that is actively included in, for example, postconflict peacebuilding, community development, and school curricula. At the same time, however, the discussion about HRE has become more mainstreamed and implementation-oriented. Bajaj (Citation2011) described how a scholarly consensus around certain core components of HRE has gradually been established. These include an agreement that such education must aim toward the development of cognitive, emotional, and attitudinal abilities, and toward action competences. Furthermore, it is agreed that human rights must be embedded in educational content and processes. The most widespread definition of HRE is found in the UN Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training (UN, Citation2011). According to this, HRE should aim at:

promoting universal respect for and observance of all human rights and fundamental freedoms and thus contributing, inter alia, to the prevention of human rights violation and abuses by providing persons with knowledge, skills and understanding and developing their attitudes and behaviors, to empower them to contribute to the building of a universal culture of human rights.

The UN definition points out the promotion of respect for and observance of human rights as a central striving of HRE. Such respect is expected to contribute to the realization of the aspects listed thereafter. The declaration asserts that this is to be achieved by educating persons about human rights (knowledge and understanding about the norms, principles and values, and the mechanisms for their protection), through human rights (teaching and learning in a rights-respecting way), and for human rights (enabling learners to enjoy and exercise their rights and respect and uphold the rights of others; see United Nations, Citation2011). The main aim of HRE stated in the UN definition is the building of a universal culture of human rights. Through education, learners should be empowered to contribute to such a societal development.

NGOs’ work to promote human rights education benefits from the successful UN discourse and, in part, also aligns with it. But, at the same time, the NGO perspective, being rooted in social movements and mobilization against the unjust exercise of power, has traditionally had a conflict-ridden relationship to the state, and thus also to national and supranational directives. The UN message of HRE as a means to build a universal culture of human rights for respect and stability is therefore, to some extent, in tension with the activist, bottom-up perspective of NGOs (Bajaj, Citation2011; Gerber, Citation2008). From this view, HRE should empower learners to act in defense of human rights individually as well as in groups and communities. The signaling of collectivity and grass-root movements protesting against injustice and rights violations indicates a different main aim for HRE than the United Nations’ aim.

The consensus on core components and educational content and processes is therefore only a surface agreement. The ultimate aim of HRE departs in two directions, representing foundationally different perceptions of what is to be attained through HRE. The UN discourse’s prioritization of building a human rights culture (Gerber, Citation2008) is expected to promote social cohesion, societal stability, peace, and respect for and tolerance of difference (Bajaj, Citation2011, Citation2017; Struthers, Citation2015). The NGO-related critical discourse’s emphasis on cultivation of action competence for social change (Monaghan et al., Citation2017) anticipates that individuals and groups take action in the protection of human rights, and are prepared to counter oppressive regimes, injustice, and human rights violations (Tibbitts, Citation2017; Zembylas, Citation2017).

Practice-oriented and critical HRE-scholars

The differing conceptions presented above are reflected in HRE scholarship. Coysh (Citation2017) distinguished two groups of HRE scholars: the practice-oriented and the critical. The practice-oriented literature seeks to investigate and describe the undertaking of HRE in informal and formal settings. The UN approach to HRE is generally taken as the starting point in this work, and critical exploration or discussion of the underlying rationale, aims, or what HRE actually means is not in focus.

Research-based pedagogical tools have been developed to support HRE in school (Katz & Spero, Citation2015). Criticism in practice-oriented and school-based HRE research has been directed to the governing of education, educational processes, and practical design, and teachers’ and students’ conceptions of HRE. As mentioned, weak curriculum support, insufficient teacher knowledge or feelings of uncertainty, and a tendency to focus on people and places far away have been demonstrated. Also, school programs for human rights education have been both applauded and criticized (Davies, Citation2010; Sebba & Robinson, Citation2010; Trivers & Starkey, Citation2012).

The critical scholarship has directed less attention to the practical undertaking of HRE and instead highlighted and addressed a range of problematical aspects in the dominant UN discourse. A technical teaching approach to HRE has been identified, in which juridical treaty awareness is the prioritized educational content, and education is treated as one-way transmission from teacher to student (Tibbitts, Citation2017). An uncritical tendency in the discourse has been demonstrated, which discourages critical analysis of human rights and the human rights regime. This lack of critique creates an idea of a dichotomous split between rights-respecting and rights-violating communities being communicated to learners (Al-Daraweesh & Snauwaert, Citation2015; Keet, Citation2017; Zembylas, Citation2017). The critical scholarship has further argued that HRE should be acknowledged as part of a political and ideological struggle for social justice, and therefore should be understood as a tool for social change (Heggart, Citation2012). The way that HRE has developed as a result of the UN discourse is therefore seen as problematic (Al-Daraweesh & Snauwaert, Citation2015; Keet, Citation2012). Instead, a transformative HRE has been argued for, in which critical knowledge and action competence are developed in participatory educational processes. The learner needs to be personally transformed through HRE by developing a view of him- or herself and others as rights holders, and an awareness of one’s agency and ability to engage in actions for social change (Monaghan et al., Citation2017).

Policy actors’ (the United Nations’ and NGOs’) differing ideas of the ultimate aim of HRE is ground for confusion, and the available HRE scholarship may be seen to exacerbate the divergence. If the practical scholarship has been seen to be too uncritical and conventional, the critical scholarship has been described as too politically motivated, presenting a potentially unacceptable message to states that do not see the role of the school as being to foster social and political activism (Mejias & Starkey, Citation2012). Coysh (Citation2017) highlighted how little the two HRE approaches engage with each other, and Parker (Citation2018) maintained that this scholarly disagreement over the meaning and aim of HRE constitutes a signal-noise problem that hampers any development of HRE in school, and so this conflict “rumble[s] on unresolved alongside a passionate support for the project” (p. 7).

Toward the middle ground: Reconstructing the aims of HRE

If HRE is to be included in school as a recognized part of children’s and young people’s education, a more unified and comprehensible aim needs to be established that is adapted to school as a setting for human rights education. To produce an aim that both galvanizes schools and teachers to provide a comprehensive curriculum that truly qualifies as human rights education and is acceptable to various political actors in states for inclusion in national curricula, insights from both the practice-oriented and the critical scholarship should be acknowledged and merged. The limitations of each respective approach can be remedied by the strengths of the other. This includes, for example, complementing the concrete methods and teaching support developed by practice-oriented scholarship with critical scholarship’s emphasis on the necessity and benefits of participatory and interactive pedagogy. The absent critique and interrogation of the theoretical foundations of HRE in the practical work can be balanced with the critical scholarship’s arguments for the need to foster critical thinking capacity, including a reflection about human rights themselves.

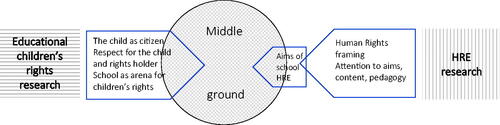

The aims of HRE for children and young people in school, therefore, need to undergo a reconstruction on the way to the middle ground, as visually represented in .

Adaptation to the school context is not limited to a clearer account of the aims, however. Educational content that supports the achievement of the aims must be chosen. The main governing structure for educational content in school is the curriculum, which is often formulated at a national level. This matter is explored in the next section.

Cardinal complication #3: The missing curriculum

The third and final cardinal complication for HRE in school is the lack of a developed curriculum. A curriculum presents a selection of knowledge and skills that teachers are expected to plan for and teach, and that students are expected to learn and master. A curriculum agreed upon at the political level, therefore, is an important tool both for states to govern formal education and for teachers in their professional work.

The selection of educational content to be included in the curriculum is not neutral; rather, it is the result of a struggle between the proponents of various perspectives, negotiated by policymakers, subject experts, and the profession. For well-established school subjects, such as mathematics or history, perceptions of central content are also carried by professionals in what have been called selective traditions (Sund & Wickman, Citation2008). These are sometimes in accordance with the national curriculum, and sometimes not. Through the support of national curricula and professional selective traditions, teachers have a common and relatively stable perception of what is to be taught and learned that guides them in their teaching. For established subjects, general curriculum patterns are similar across nations: for example, that children should learn the history of their own community in more detail than world history, or that language education includes reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills, as well as grammar. To a significant extent, therefore, curricula are international in character, which gives teachers of certain subjects a global identity. The curriculum framework also includes an idea of progression—for example, what is included in early education as well as at intermediate and advanced levels.

Problems around the development of an HRE curriculum

For HRE, none of this is at hand. The varying and generally weak national school curricula give insufficient guidance and regulations for the content of HRE (Phillips, Citation2016; Quennerstedt, Citation2019). HRE-curriculum traditions carried by the professionals themselves are nonexistent.

Parker’s (Citation2018) analysis of the absence of a curriculum for HRE, and how this is a significant explanation for the scarcity of HRE in schools, is illuminating. Parker described how new school courses are notoriously difficult to establish because the curriculum is already in place and its advocates resist change. Curriculum development and reform, therefore, demands intense engagement from key actors—and from curriculum scholars, in particular. The disengagement of academics from curriculum development in recent decades has had troublesome consequences for a new field, such as HRE, according to Parker. Curriculum scholars have turned their interest away from the formation of school knowledge and skills, to focus instead on ideology critique and the learner. These are, of course, important matters, but they have, Parker argued, outmaneuvered research attention to content selection and teaching. In this landscape, educational content is more or less taken for granted as already established (Parker, Citation2018).

The general tendency described above is also true for HRE scholars. The lack of direct and detailed attention to content selection has resulted in a scarcity of academic curricular expertise on HRE, and an absence of concrete debates about what ought to be included in an HRE curriculum and what progression looks like. This leaves teachers without support; they are not offered well-deliberated and research-based suggestions of suitable educational content for the youngest age group, or any indications of what the content ought to be in the most advanced HRE for the oldest students in schools (Struthers, Citation2019). In the absence of a clear curriculum, provided either by the state or by the profession itself, one solution has been to turn to other actors who are seen as experts on human rights: NGOs (Mejias & Starkey, Citation2012).

NGOs have developed educational material and programs to support schools: Two examples are the UNICEF UKs Rights Respecting Schools Award and Amnesty International’s Human Rights Friendly Schools (Dunhill, Citation2019; Webb, Citation2014), both with an international scope. Educational resources offered by NGOs indicate areas to teach and even provide complete lesson plans. A potentially troublesome issue to raise here is that the selection of content and methods is handed over to actors outside of schools. There is a substantial risk that teachers are positioned as laypeople in relation to this particular field of knowledge. A further complication with the NGO material was shown by Struthers (Citation2019). Teachers in her study perceived NGO material as potentially biased and overly political. One interviewee said: “[W]hat I would want to see was that it [the material] was based in sound research: that it had been properly trialed and was academically sound rather than as part of any broader political agenda” (p. 194).

Taken together, there are several ways in which HRE is constituted as an atypical school activity: weak curriculum direction, low teacher confidence, and external actors providing content and resources. Several scholars have pointed out that human rights need to become a general part of school education, perceived as less special and more mainstream (Struthers, Citation2016; Zembylas et al., Citation2015). This requires that an idea of an HRE curriculum must be developed, which in turn could generate both clearer national curricula guidance and professionally carried selective traditions. I agree with Parker (Citation2018), who argued that the responsibility for formulating such an idea of an HRE curriculum rests largely on the specialist/academic community.

HRE pedagogy: Engage the teachers!

A curriculum primarily answers the question of what (i.e., What content?), but the parallel question of how (i.e., How to teach and learn?) cannot be neglected in the development of a curriculum. The methods for instruction and learning—that is, the pedagogy—are as important as the educational content if the aims are to be reached.

HRE research has highlighted the insufficiency of a technical transmission type of pedagogy in human rights education, focused on facts, treaties, and ethical principles. Critical HRE scholars have emphasized that, in order to provide comprehensive HRE (i.e., about, through and for human rights), an experience-based pedagogy is necessary. Students must experience being respected as full-status humans with rights and they need to be given opportunities to practice how to claim and exercise their own rights, and how to protect the rights of others. The need for students to reflect critically on human rights has also been underlined. But this remains to be done, since HR research has not addressed how this can be achieved within the frames of the formal education system, for students of varying ages. Such concrete adaption of HRE pedagogy to the school setting includes, for example, ideas about how to cultivate the ability to claim or exercise rights can progress from young children to a more advanced practice of older teens, or what kind of critical thinking is suitable in the first encounters with human rights, and how this expands with age. These are the type of questions that teachers struggle with, and for which scholarly support is currently absent.

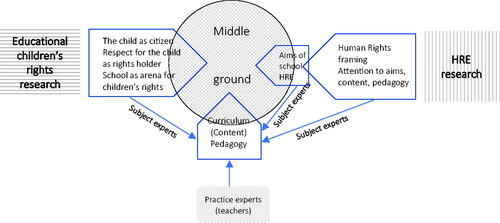

Responsibility for developing a school HRE curriculum and pedagogy should be taken up by children’s rights and HRE scholars. However, this endeavor needs to include another group of specialists: teachers. Teachers are experts in educational practice, in interaction with children and young people of various ages, and in the planning and undertaking of education. An important part of teacher professionalism lies in the specific competence to design teaching. Shulman (Citation1986, p. 13) expressed this concisely: “The teacher is not only a master of procedure, but also of content and rationale, and capable of explaining why something is done.”

illustrates how the expertise of different subject specialists and teachers could be merged to form the best possible ground for establishing an HRE curriculum and a pedagogy suitable for students of various ages. The matters of educational content and pedagogy accordingly need a detour on the way to the middle ground.

Concluding discussion: Toward a common ground for children’s and young people’s HRE

HRE for children and young people does not take place in schools in the way aimed for by the international community, national states, and NGOs. Explanations should be sought not only in policy and practice but also in the academic work that feeds into both political and professional sectors. This article has therefore highlighted to how current scholarly work contributes to a construction of HRE for children and young people in schools that currently fall short of supporting such policy and practice. By highlighting problematic areas, my ambition has been to provide an elaborated ground for a new direction in the academic discussion on human rights education for children and young people, which in turn can be a catalyst for change in school practice.

Three cardinal complications in scholarly work have been explored: (1) the separation between educational children’s rights research and HRE research, (2) the lack of clarity about the ultimate aims of HRE, and (3) the absence of an HRE curriculum. I have argued that researchers from various fields and perspectives need to meet around HRE in school. I have suggested that this conversation should also include teachers. To move forward, communication is accordingly needed between subject experts from different academic traditions and practice experts. This communication should be of a certain kind, one that aids the coordination of actions. I understand communication, as Dewey suggested, as the process of making something in common (Citation1929), and I propose that HRE for children be made in common for scholars interested in the issue.

Note here that making something in common does not mean to reach, or even aim for, an ultimate consensus. Debate and controversy are oxygen in the academic arteries, but they are not the end purpose or outcome. Everlasting scholarly dispute over a topic is not useful to society, which instead needs the academic community to reach conclusions and, based on these, to speak with a robust voice. Agreements may be tentative and temporary, but they are still agreements. Biesta pointed to how the coordination of actions to achieve something together is tied to communication:

As soon, however, as we start to act together, as soon as we engage in a common activity in order to achieve something together, it becomes important for the successful coordination of our activities that we adjust our individual patterns of being and doing. The point of Dewey’s view of communication is that we do not first need to agree about our interpretation of the world and only then can start acting together. His point rather is that the change of our individual perspectives is the result of our attempts to coordinate our actions and activities and it is in this way that we make something in common. (Biesta, Citation2006, p 17)

If HRE in school is to be achieved, the different research fields and perspectives need to join forces to create a common ground and coordinate actions. Only then can a comprehensible idea be robustly communicated to nations and teachers. The middle ground sketched here offers a meeting place for this endeavor, but what comes out of such scholarly communication and coordination of actions remains to be seen.

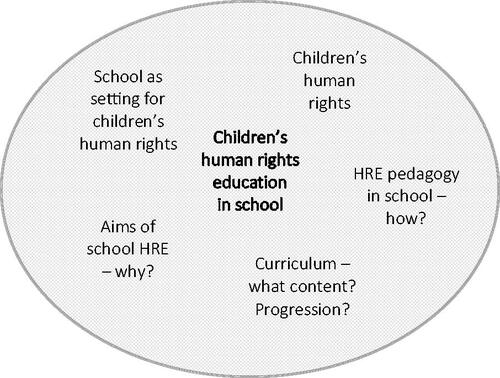

The middle ground

In the middle ground, positions that privilege the child and child rights in school and that place a central focus on human rights education should meet and their respective views amalgamate. Continued research and academic discussion should proceed from an integration of these two positions. visualizes aspects that need to be developed in common.

One matter that needs to be considered in the creation of a common understanding is the separation between children’s and human rights. Instead of approaching these as different areas, they should be viewed and conceptualized as parts of the same whole, manifested in the expression “children’s human rights.” The education discussed will then be children’s HRE.

To attain this, first, more scholarly attention needs to be directed to the relation between children’s and human rights. Second, the question must be raised as to whether human rights education for children and young people differs from human rights education for adults and, if so, in what way. This is important to engage in seriously because it lays the foundation for all ensuing reflections. Do, for example, the aims of the education vary depending on the age of the learner? Or are the aims the same?

One difference between HRE for adults and children is, of course, that for children it is provided in school. This is a crucial aspect that needs more attention. Formal schooling differs significantly from education in community projects or NGO activities. First, the education of children and young people in school is of great importance to nations; therefore, school education is highly regulated. A formulation of HRE for children in school must be compatible with varying national interests in the education of a population, but still encompass the breadth required. Second, the wide age range of learners must be addressed by engaging in how educational content and teaching methods can be adapted to children of differing ages, taking account of their respective knowledge and capacities. Schools are established institutions with strong traditions and trained professionals. The realization of HRE in schools, therefore, requires awareness and attention to traditions, both those that will support HRE and those that will oppose it. Teachers have been unanimously identified in research as key to the successful realization of HRE. Continued attention needs to be paid to teachers and significantly more to teacher education. Taken together, a major task for academic communication in the middle ground is to contextualize HRE to school as a particular setting for such education. Placing HRE in schools will inevitably affect how content and pedagogy are understood, and maybe also the aim of it.

If scholars who engage in rights education meet in the middle ground and start to coordinate their arguments and views, and together identify and elaborate on the main features of HRE, a ground for the proliferation of children’s and young people’s human rights education can be achieved. This ground will then not only be middle but, more importantly, common.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ann Quennerstedt

Ann Quennerstedt is a professor of education at Örebro University in Sweden. Her research examines a broad spectrum of children’s human rights issues in educational contexts, and she has published extensively on these matters. She leads the European Educational Research Association Network Research in Children’s Rights in Education and is associate editor of International Journal of Children’s Rights.

References

- Al-Daraweesh, F., & Snauwaert, D. T. (2015). Human rights education beyond universalism and relativism: A relational hermeneutic for global justice. Springer.

- Alderson, P. (2018). How the rights of all school students and teachers are affected by special educational needs or disability (SEND) services: Teaching, psychology, policy. London Review of Education, 16(2), 175–190. doi:10.18546/LRE.16.2.01

- Bačáková, M. (2011). Developing inclusive educational practices for refugee children in the Czech Republic. Intercultural Education, 22(2), 163–175. doi:10.1080/14675986.2011.567073

- Bajaj, M. (2011). Human rights education: Ideology, location, and approaches. Human Rights Quarterly, 33(2), 481–508. doi:10.1353/hrq.2011.0019

- Bajaj, M. (Ed.). (2017). Human rights education. Theory, research, practice. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Biesta, G. (2006). Context and interaction: Pragmatism's contribution to understanding learning-in-context. In Conference Paper. ESRC Teaching and Learning Research Programme Thematic Seminar Series. Exeter (Vol. 22).

- Bron, J., & Thijs, A. (2011). Leaving it to the schools: Citizenship, diversity and human rights education in the Netherlands. Educational Research, 53(2), 123–136. doi:10.1080/00131881.2011.572361

- Cassidy, C., Brunner, R., & Webster, E. (2014). Teaching human rights? ‘All hell will break loose!’ Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 9(1), 19–33. doi:10.1177/1746197913475768

- Çayır, K., & Bağlı, M. T. (2011). ‘No‐one respects them anyway’: Secondary school students’ perceptions of human rights education in Turkey. Intercultural Education, 22(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/14675986.2011.549641

- Coysh, J. (2017). Human rights education and the politics of knowledge. Taylor & Francis.

- Davies, L. (2010). The potential of human rights education for conflict prevention and security. Intercultural Education, 21(5), 463–471. doi:10.1080/14675986.2010.521388

- Dewey, J. (1929). Experience and nature. Open Court Publishing Company.

- Dunhill, A. (2019). The language of the human rights of children: a critical discourse analysis [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Hull.

- Gerber, P. (2008). From convention to classroom: The long road to human rights education [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Melbourne.

- Heggart, K. (2012). Synthesizing participatory human rights education and critical consciousness in Australian schools. In R. Mitchell and S. Moore (Eds.), Politics, participation & power relations (pp. 83–100). Brill Sense.

- Katz, S. R., & Spero, A. M. (2015). Bringing human rights education to US classrooms: Exemplary models from elementary grades to university. Springer.

- Keet, A. (2012). Discourse, betrayal, critique: The renewal of human rights education. In Safe spaces (pp. 5–27). Brill Sense.

- Keet, A. (2017). Does human rights education exist? International Journal of Human Rights Education, 1(1), 6.

- Leung, Y. W., Yuen, T. W. W., & Chong, Y. K. (2011). School‐based human rights education: Case studies in Hong Kong secondary schools. Intercultural Education, 22(2), 145–162. doi:10.1080/14675986.2011.567072

- Lucas, A. G. (2009). Teaching about human rights in the elementary classroom using the book A Life Like Mine: How children live around the world. The Social Studies, 100(2), 79–84. doi:10.3200/TSSS.100.2.79-84

- Lundy, L., Kilkelly, U., Byrne, B., & Kang, J. (2012). The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child: A study of legal implementation in 12 countries. Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast.

- Mejias, S., & Starkey, H. (2012). Critical citizens or neo-liberal consumers? Utopian visions and pragmatic uses of human rights education in a secondary school in England. In R. C. Mitchell and S. Moore (Eds.), Politics, participation & power relations (pp. 119–136). Brill Sense.

- Monaghan, C., Spreen, C. A., & Hillary, A. (2017). A truly transformative HRE: Facing our current challenges. International Journal of Human Rights Education, 1(1), 4.

- Parker, W. C. (2018). Human rights education’s curriculum problem. Human Rights Education Review, 1(1), 05–24. doi:10.7577/hrer.2450

- Perry‐Hazan, L., & Lambrozo, N. (2018). Young children's perceptions of due process in schools’ disciplinary procedures. British Educational Research Journal, 44(5), 827–846. doi:10.1002/berj.3469

- Perry-Hazan, L., & Tal-Weibel, E. (2020). On legal literacy and mobilization of students’ rights from a disempowered professional status: The case of Israeli teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 90, 103016. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2020.103016

- Phillips, L. (2016). Human rights for children and young people in Australian curricula. Curriculum Perspectives, 36(2), 1–14.

- Quennerstedt, A. (2010). Children, but not really humans? Critical reflections on the hampering effect of the 3 p's. The International Journal of Children's Rights, 18(4), 619–635. doi:10.1163/157181810X490384

- Quennerstedt, A. (2011). The construction of children's rights in education–A research synthesis. The International Journal of Children's Rights, 19(4), 661–678. doi:10.1163/157181811X570708

- Quennerstedt, A. (Ed.). (2019). Teaching children’s human rights in early childhood education and school. Educational aims, content and processes. Reports in Education 21. Örebro University.

- Quennerstedt, A., & Moody, Z. (2020). Educational children’s rights research 1989–2019: Achievements, gaps and future prospects. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 28(1), 183–208. doi:10.1163/15718182-02801003

- Reynaert, D., Bouverne-de-Bie, M., & Vandevelde, S. (2009). A review of children’s rights literature since the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Childhood, 16(4), 518–534. doi:10.1177/0907568209344270

- Rinaldi, S. (2017). Challenges for human rights education in Swiss secondary schools from a teacher perspective. Prospects, 47(1–2), 87–100. doi:10.1007/s11125-018-9419-z

- Rinaldi, S., Moody, Z., & Darbellay, F. (2020). Children’s human rights education in Swiss curricula. An intercultural perspective into educational concepts. Schweizerische Zeitschrift Für Bildungswissenschaften, 42(1), 64–83.

- Robinson, C. (2017). Translating human rights principles into classroom practices: Inequities in educating about human rights. The Curriculum Journal, 28(1), 123–136. doi:10.1080/09585176.2016.1195758

- Russell, S. G., & Suárez, D. F. (2017). Symbol and Substance: Human Rights Education as an Emergent Global Institution. Human Rights Education, 19–46. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Sandell, K., Öhman, J., & Östman, L. (2005). Education for sustainable development: Nature, school and democracy. Studentlitteratur.

- Sargeant, J., & Gillett-Swan, J. K. (2019). Voice-inclusive practice (VIP): A charter for authentic student engagement. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 27(1), 122–139. doi:10.1163/15718182-02701002

- Sebba, J., & Robinson, C. (2010). Evaluation of UNICEF UK’s rights respecting schools award (RRSA). UNICEF UK.

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. doi:10.3102/0013189X015002004

- Struthers, A. E. (2015). Human rights education: Educating about, through and for human rights. The International Journal of Human Rights, 19(1), 53–73. doi:10.1080/13642987.2014.986652

- Struthers, A. E. (2016). Human rights: A topic too controversial for mainstream education? Human Rights Law Review, 16(1), 131–162. doi:10.1093/hrlr/ngv040

- Struthers, A. E. (2019). Teaching human rights in primary schools: Overcoming the barriers to effective practice. Routledge.

- Sund, P., & Wickman, P. O. (2008). Teachers’ objects of responsibility: Something to care about in education for sustainable development? Environmental Education Research, 14(2), 145–163. doi:10.1080/13504620801951681

- Theobald, M., Danby, S., & Ailwood, J. (2011). Child participation in the early years: Challenges for education. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 36(3), 19–26. doi:10.1177/183693911103600304

- Tibbitts, F. (2002). Understanding what we do: Emerging models for human rights education. International Review of Education [Internationale Zeitschrift fr Erziehungswissenschaft/Revue Inter], 48(3/4), 159–171. doi:10.1023/A:1020338300881

- Tibbitts, F. (2014). Human rights education here and now: US practices and international processes. Journal of International Social Studies, 4(2), 129–134.

- Tibbitts, F., & Katz, S. R. (2017). Dilemmas and hopes for human rights education: Curriculum and learning in international contexts. Prospects, 47(1–2), 31–40. doi:10.1007/s11125-018-9426-0

- Tibbitts, F., & Kirschschläger, P. G. (2010). Perspectives of research on human rights education. Journal of Human Rights Education, 2(1), 8–29.

- Tibbitts, F. L. (2017). Revisiting ‘emerging models of human rights education’. International Journal of Human Rights Education, 1(1), 2.

- Trivers, H., & Starkey, H. (2012). The politics of critical citizenship education: Human rights for conformity or emancipation? In R. C. Mitchell and S. Moore (Eds.), Politics, participation & power relations (pp. 137–151). Brill.

- United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights, General Assembly resolution 10 December 1948, 217 A (III).

- United Nations (1966). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI), 16 December 1966.

- United Nations (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. General Assembly resolution 44/25, 20 November 1989.

- United Nations (2006). World Programme for Human Rights Education. First Phase. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

- United Nations (2010). Final evaluation of the implementation of the first phase of the World Programme for Human Rights Education, General Assembly A/65/322, 24th August 2010.

- United Nations (2011). World Programme for Human Rights Education. General Assembly Resolution 66/137, 19 December 2011.

- Waldron, F., & Oberman, R. (2016). Responsible citizens? How children are conceptualised as rights holders in Irish primary schools. The International Journal of Human Rights, 20(6), 744–760. doi:10.1080/13642987.2016.1147434

- Webb, R. (2014). Doing the rights thing: An ethnography of a dominant discourse of rights in a primary school in England [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Sussex. EThOS. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/50800/

- Zembylas, M. (2017). Cultivating critical sentimental education in human rights education. International Journal of Human Rights Education, 1(1), 3.

- Zembylas, M., Charalambous, P., Lesta, S., & Charalambous, C. (2015). Primary school teachers’ understandings of human rights and human rights education (HRE) in Cyprus: An exploratory study. Human Rights Review, 16(2), 161–182. doi:10.1007/s12142-014-0331-5