?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This article focuses on South Korea as a case, analyzes a collection of 87,487 tweets referencing both COVID-19 and South Korea during the period of the pandemic, and examines global users’ understandings and/or assessments of South Korean responses to the health crisis. This article uses Pseudo-document-based Topic Model (PTM) as an advanced machine learning technique for classifying short texts into viable topics or themes. In the PTM results, human rights-related topics received much less attention than other topics on government responses, health measures, vaccines, and economic issues. Furthermore, discussions on surveillance, restrictions on assembly, and stigmatization of religious groups tended to emerge rather briefly and soon subsided. Rights protection in the South Korean context appeared at odds with the larger target of protecting public health and the safety of society. The analyses demonstrate a tradeoff between implementing public health imperatives and respecting human rights in South Korea.

Introduction

Governments worldwide have struggled to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, an unprecedented global health crisis, with vulnerable groups at risk of infection, devastation, cynicism, and depression (Forman & Kohler, Citation2020; Hatcher, Citation2020; Kavanagh & Singh, Citation2020; Travaglino & Moon, Citation2020). In tandem with governments’ measures to control its spread (e.g., tracking and testing, lockdowns, and closure of public places), individuals and group members did their part by practicing personal hygiene and social distancing, although they also coped with psychological depression (Lee et al., Citation2020).

As time and this parallel movement advanced, scholars began to address citizens’ public discussions of the pandemic on different social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, and Reddit (Ordun et al., Citation2020). This scholarly interest stemmed from indications that online platforms are invaluable venues for citizens to respond to health policy measures, express their feelings and thoughts, and share their views with other users. Public opinion of this sort characterizes the collective voices on social media and, thus, analyzing and understanding these opinions as expressed in these forums are critical. As Murdie (Citation2022) emphasizes in this volume, public opinion related to human rights merits attention for future scholarship of human rights. Added to this is the value of social media postings in providing policy implications as well as highlighting the connections between policymaking, public opinion, and media coverage (Wicke & Bolognesi, Citation2020).

Analyses of COVID-19 postings in general have provided insights into how citizens in many parts of the world felt about and reacted to the unfolding health crisis, but they often lack analytical power because they were not focused on a particular country or specific policy response (Yin et al., Citation2020). Although COVID-19 was a global pandemic, the cases, deaths, and responses were all decidedly particular to individual nations. As Chiozza and King (Citation2022) report in this volume, from the initial phase of the pandemic, we witnessed a great deal of variation in government responses and learned the salience of the regime type. With an emphasis on individual attitudes, Chilton et al. (Citation2020) show that national public opinions vary greatly about the legitimacy of liberty restrictions designed to combat COVID-19. Against this backdrop, I focus on South Korea as a case, analyzing a collection of 87,487 tweets referencing both COVID-19 and South Korea during the period of the pandemic, January 2020 to August 2021, and examining global users’ understandings and assessments of South Korean responses to the health crisis.

South Korea serves as an excellent laboratory for such a study because its case demonstrates both the achievements and limits of a national response from a human rights perspective. The South Korean strategy called the “K-quarantine” was once hailed as a model for other countries, involving, as it did, using extensive testing, tracking, and treatment to keep the cases low and encouraging social distancing and wearing masks as daily practices. The K-quarantine appeared to have worked in halting a large outbreak without shutting down the country’s borders or locking down towns (Kim et al., Citation2020). Although the strategy aimed at sustaining a fragile balance between using government power to protect public health and not infringing on civil liberties, critics challenged the K-quarantine from the perspectives of civil liberty and basic human rights (Ryan, Citation2020; Yamin & Habibi, Citation2020). Therefore, I examined how much attention human rights issues received from global Twitter users and what specific topics were of most interest to users who appeared to care about human rights.

For this article, I used Pseudo-document-based Topic Model (PTM) as an unsupervised machine learning technique for classifying short texts into viable topics or themes (Zuo et al., Citation2016). PTM shares the topic model advantages of automatically providing a mixture of topics from a document and data corpus but mitigates its disadvantages of not effectively handling short texts that lack sufficient word co-occurrence information. The use of a topic model fits with the key empirical focus of this article: the themes in the public discussion on Twitter regarding South Korean responses to the pandemic. The technique allowed for gauging the value online users attached to public health, foreign responses, patients’ rights, and human rights in general in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The rise of the K-quarantine

A pandemic triggers national health authorities and other government entities to mobilize to contain the infecting virus, treat the infected, and alert citizens (You, Citation2020). In response to COVID-19, countries’ preparedness, experiences, resources, and support from citizens varied greatly, and governments thus appeared to be responding differently to the crisis (Spadaro, Citation2020). The severity of infections and associated mortality rates also contributed to differences in national responses related to, for instance, lockdowns, travel bans, the use of personal equipment like masks, and privacy restrictions (Duic & Sudar, Citation2021).

Nonetheless, countries do respond to infectious disease outbreaks in strikingly similar ways: They immediately implement emergency management policies that involve readying health facilities and professionals, tracking and tracing the spread of the virus, ensuring proper individual hygiene, and, if need be, restricting normal activities of individuals and communities. Proper coordination and collaboration with health agencies and professionals are imperative for containing the spread of viruses.

The South Korean response was no exception. The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in unprecedented policy measures to bring the spread under control that had been chosen and implemented with consideration for the country’s handling of previous infectious diseases, such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak of 2015. In the aftermath of its flawed MERS response, the South Korean government made four dozen reforms to strengthen public health emergency preparedness including ensuring effective testing, tracing, and treatment (You, Citation2020).

A South Korean white paper summarized the government’s response in three policy strategies: (1) swift action; (2) the “3Ts” of widespread and rigorous testing, contact tracing, and treatment; and (3) public–private partnerships and civic awareness (ROK, Citation2020). Scholars have emphasized the country’s democratic unitary political system coupled with strong public trust in healthcare professionals as the key conditions that enabled speedy implementation of policy decisions at the local level (Chung & Choe, Citation2008; You, Citation2020). The implementation was further buttressed by a well-coordinated national plan aided by governing bodies, including the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The government’s and communities’ efforts halted a large outbreak without shutting Korea’s borders or locking down towns (Kim et al., Citation2020).

These efforts are why the South Korean path to COVID-19 containment was hailed as a successful case. International society praised the country’s readiness associated with the efficient 3Ts, timely provision of personal protective equipment (PPE), effective treatment of patients, and invoking civic conscience for the shared goal of fighting the virus (Lee & Lee, Citation2020). The K-quarantine, a rhetorical nod to the global popularity of K-pop, was also praised for allowing the government and the nation to pursue the two-pronged strategy of containing the spread of the virus while keeping the economy running (Yi & Lee, Citation2020).

Rights debates

Just as policy responses elsewhere inevitably involved legal and policy measures restricting various rights of citizens, and traded off certain rights in favor of health-related entitlements (Brysk, Citation2022; Chenoweth, Citation2022; Chiozza & King, Citation2022), South Korea also implemented and consolidated measures that limited basic civil rights as well as restricting economic activities (e.g., restaurants, bars, and shops; Botto, Citation2020). Following the path of other countries—including China, Hong Kong, and Singapore—South Korea also turned to surveillance as a means of containing and removing the virus and brought back policies that severely limited citizens’ right to association and assembly (Cha, Citation2020). To ensure effective surveillance, the country relied heavily on IT-based epidemic containment strategies used for documentation, modeling, and contact tracing (Park et al., Citation2020). South Korea took part in the global response that 34 countries worldwide, including 22 democracies adopted, employing some type of digital programs immediately after the pandemic began (Chiozza & King, Citation2022; Eck & Hatz, Citation2020).

Surveillance

In March 2021, the South Korean government launched the COVID-19 Epidemiological Investigation Support System (EISS), a new computer network designed to support epidemiological investigations of confirmed cases (Ryan, Citation2020). It targeted confirmed patients with remarkable speed and accuracy of information acquisition aided by an AI-driven smart city technology system. EISS allows investigators to combine the results of interviews with medical records, credit card transactions, transportation card details, and CCTV footage by automatically identifying a confirmed person’s location and movements over time. The system was updated with data added from overseas immigration and healthcare facility records.

What made all these surveillance strategies possible was a legal breakthrough triggered by the flawed response to the 2015 MERS outbreak. One of the four dozen legal reforms after 2015 included amending the Contagious Disease Prevention and Control Act and this amendment permitted health authorities to override certain provisions in the Personal Information Protection Act, which initially banned the collection, use, and disclosure of personal data without consent from infected individuals and those suspected to be infected. All of these developments raised concerns from various sectors of society over privacy and personal information protection. As Brysk (Citation2022) points out in this volume, health-related international jurisprudence established responsibilities of medical professionals and government agencies relative not only to patients’ access to essential medicines but also to their privacy.

Several months after the first confirmed case in South Korea in January, 2020 international media and human rights groups began to criticize that personal information released by the South Korean government disrupted private lives and invoked social stigma and warned of human rights infringements caused by the IT-based system, including mobile apps designed to collect users’ geolocated movement data. During the earlier phase of the emergency in 2020, the public decried the authorities’ handling and sharing of intimate personal details on infected and potential patients, such as their location, age, and sex and the names of the restaurants, shops, and other business premises they had visited. Public disclosures of the travel paths and contacts of confirmed cases increasingly raised concerns about privacy invasion (Park et al., Citation2020).

On March 9, 2020, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea issued a recommendation warning that excessive public disclosures could undermine public health by dissuading those suspected of infection from cooperating voluntarily and causing public disdain or social stigma. This intervention served as an impetus for the health authority to go through a serious of revisions on the disclosure guidelines ranging from limiting the scope of disclosures, through excluding a confirmed patient’s personal details, to making route disclosures nearly anonymized in late 2020. The subsequently decreased privacy concerns coupled with a high level of public support for contact tracing led to the intrusive surveillance structure being sustained and deployed.

From June 2020, the contact tracing method evolved into the QR code-based system through which the managers at restaurants, cafes, fitness centers, and other public places asked visitors to produce an ephemeral QR code and have the QR code scanned. To alleviate private concerns, the authority ensured that ephemeral and pseudonymized QR codes are separated from personally identifiable data, the pieces of the data are combined only when a visitor is confirmed positive, and the collected data are removed from the server after four weeks (Park et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, public anxiety remains about the potential leakage of the personal data collected through the QR code, and concerns remain about the lack of legal basis for how long the information needs to be kept and when it should be removed.

Stigmatization

From the beginning of the pandemic, South Koreans received flurries of emergency text messages from authorities, alerting them to be wary of the movements of citizens with COVID-19 infections. A typical alert contained the infected person’s age, gender, and area of residence and a detailed log of his or her movements to the minute; the names of businesses he or she had visited and at what times were also released. Singapore followed suit, but the alerts there never reached the detail of those in South Korea. South Korean authorities released details such as when people left for work, whether they wore masks on the subway, the stations where they changed trains, and the massage bars they visited for leisure.

The specificity of the released public data about infected persons raised inevitable concerns about privacy because the data could be identifiable, and one problem was, expectedly, social stigmatization. In many multicultural societies, certain specific groups were stigmatized in efforts to blame the coronavirus pandemic on those associated as carriers of the virus (Roberto et al., Citation2020). In South Korea, infected patients and those who were suspected were perceived as responsible for the spread of the virus. They were often ignored or treated as criminals when they had no possible individual responsibility (Oh et al., Citation2020). Infected citizens who violated health authority mandates were considered candidates for the same electronic monitoring anklets worn by sex offenders.

After cases were confirmed at the Itaewon club, local newspapers explicitly named the club as a gay bar and ran articles stigmatizing sexual minorities and holding them responsible for the virus’s spread. The government’s monitoring technology and standardized tracing methods all escalated the atmosphere for demonizing the LGBTQ community. Visitors to the club were pressured to hide their identity, and a private education institution instructor was accused of causing further infection by hiding his job and movements; he was eventually arrested and sentenced to six months in jail. Scholars assert that the government’s overconfidence in the K-quarantine and their quarantine-first strategy inevitably resulted in targeting the groups that contracted the virus, and it tarnished the impacts of the government regimen. These groups included religious groups, foreigners, and participants in public protests (Oh et al., Citation2020).

The right of assembly at a crossroads

As the country was consumed in the second and third waves of the pandemic during the period of 2020–2021, government authorities, including President Moon, became increasingly strident, promising to use the blunt force of the law to punish those who betrayed the government’s epidemiological efforts. “No freedom of religion, assembly, or expression can be asserted at the cost of such damage,” Moon stressed, accusing religious group members and protesters of spreading the virus and thus risking the public safety by attending weekly services or occupying the streets. As Badran and Turnbull (Citation2022) show in this volume, such a policy direction needs to be viewed in the larger global context in which many governments began to use the pandemic as a reason for consolidating power, using excessive force and legal measures such as declaring states of emergency vis-à-vis controlling civil society. The government rightfully imposed certain restrictions on public gatherings to curb the spread of the virus but also wrongly used its enhanced power to demonize public demonstrations and crush dissent.

During 2020–2021, rallies of more than 10 protesters were mostly banned in South Korea, and most rallies were prohibited from several key avenues in downtown Seoul. In the summer of 2021, when the country was grappling with a fourth wave of infection fueled by the Delta variant, the police took even more stringent measures to ban and punish one-person rallies in consideration of virus outbreaks from antigovernment rallies in the summer of the previous year and as a caution against the possibility of small rallies growing larger. The police used the repressive tactic of erecting so-called bus walls, using parked police buses along main avenues and around the central square in downtown Seoul to seal off the entire area. The police also set up more than 80 checkpoints to block vehicles that were suspected of carrying protesters and equipment to check pedestrians to ensure that they would not join the protests. This suppression of public rallies was often juxtaposed on TV screens with images of thousands of shoppers gathered in packed retail stores without any intervention from enforcement officers.

South Korea’s imperfect balancing efforts between protecting the public health and protecting human rights could serve as a reminder of the economy-first mentality that pervaded the country under authoritarian governments in the 1970s and 1980s (Koo & Choi, Citation2019). Protesters defying COVID-19 warnings were easily stigmatized and criminalized and in the aftermath, the country witnessed the erosion of the democratic foundation that had buttressed the country and often garnered the nation praise for having achieved both economic growth and democracy. As Chenoweth (Citation2022) asserts in this volume, protesters who were wearing masks and social distancing outdoors seized the opportunities to accommodate the public health interests with their right to peaceful assembly. South Korean protesters demanding labor reforms, religious rights, and freedom of expression were no exception.

The anticipated rights discussion online

The South Korean response to the pandemic and the rights debate provide a larger context in which citizens made sense of and discussed the COVID-19 pandemic both on and offline. Researchers have recognized Twitter as a cyber public sphere that permits netizens to address their perceptions of and attitudes toward government policies shaping collective life. I hypothesize that global Twitter users paid attention to different aspects of the rights debate even if their attention was relatively marginal compared with the degree of attention paid to public health issues. I further hypothesize that Twitter users’ discussions of rights issues might have centered around the surveillance, stigmatization, and right of assembly issues that received notable attention from the media and past studies.

Data collection

I collected Twitter data using the Twitter API v1 accessed through the Academic Research product track and constructed a text corpus of 87,487 tweets from January 20, 2020, when the first COVID-19 patient was reported in South Korea, to August 31, 2021, the end of the observation period for this article. Using searchtweets (a Python library) to extract Twitter data, I queried the Academic Research product track on several combinations of terms, such as covid + south korea, pandemic + south korea, and pandemic + korea, to create the dataset of COVID-19 tweets focused on South Korea.

For topic modeling, I only focused on non-retweets, which decreased the corpus from 120,000 to 87,487 tweets. In other words, I had to preprocess the corpus only on the “text” field without duplication, removing retweets that would inflate the number of texts unnecessary for the analyses. With the information accessed through the API, I had to remove all the metadata, including the https hyperlink, and short words of fewer than three characters. Hashtags were also removed, because these features could cause strong influence over classification of latent topics. I next conducted standard preprocessing to prepare the Twitter data for topic modeling. I processed each tweet text to remove all punctuation marks, numbers, stopwords, and web addresses, and further implemented lower-casing, stemming, and tokenization. I needed to reduce the complexity of the data corpus in order to effectively identify the patterns that emerged from the public discussions.

Topic models

Topic models refer to a suite of algorithms for discovering the hidden semantic structures in large collections of documents (Blei, Citation2012; Park et al., Citation2019). Using vast amounts of documents as input, a topic model produces a set of interpretable topics and assesses the extent to which each document exhibits those topics. These individual documents with different weights of topics are often aggregated alongside a time unit (e.g., year), and this aggregation reveals which topics show higher probabilities than others within that time window. This powerful approach of topic models has been applied in many different fields, such as marketing, sociology, political science, digital humanities, and human rights (Boyd-Graber et al., Citation2017; Lynam, Citation2016).

The most popular technique of topic modeling is Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) as the simplest model of the kind. LDA posits that the documents themselves are observed, whereas the topic structure—the topics, topic distributions in a document, and topic assignment of a word in a document—is hidden (DiMaggio et al., Citation2013). The key computation problem of LDA, a family of Bayesian probabilistic approaches, is inferring the hidden topic structure—that is, posterior distribution, using the observed document (Bagozzi & Berliner, Citation2018).

Although LDA is a powerful tool and has been used widely, it suffers from several technical problems, and there is an ongoing debate on the nature of and solutions for these limits (Dieng et al., Citation2019). One stream involves its low performance when LDA is applied to a set of short texts, including tweets. The problem stems from the lack of information on word co-occurrence in each short text relative to conventional documents that comprise longer sections of text. Short texts make it difficult for algorithms to discern a meaningful number of topics in different proportions, which in turn decreases the number of topics a researcher has available for extracting semantic meanings from large documents. Efforts were made to aggregate short texts into regular-sized pseudo-documents using auxiliary contextual information— such as authorship, hashtags, time, and locations (Hong & Davison Citation2010).

Among the aggregation solutions, I used PTM, which uses implicit aggregation of short texts against data sparsity. In this way, the topic distribution modeling of a vast number of short texts is transformed into the topic modeling of many fewer pseudo-documents, which in turn are much more beneficial for parameter estimation. PTM assumes a high volume of extremely short texts are generated from much less yet regular-sized pseudo-documents (Zuo et al., Citation2016), and does not require the use of auxiliary information, which is not always available or is too costly for deployment (Zuo et al., Citation2016).

I provide the algorithm describing the generative process for topic modeling with PTM. From Steps 1–3, I first consider three multinomial distributions that follow Dirichlet Allocations (ψ, θl, Φz) with the corresponding hyperparameters (λ, α, β). In Step 4(a), a multinomial distribution ψ is introduced to model the distribution of short texts over pseudo-documents. I assume each short text belongs to one and only one pseudo-document. Then, in step 4(b), each word in a short text is generated by first sampling a topic z from topic distribution θl of its pseudo document, and then sampling a word from word distribution Φz (Zuo et al., Citation2016).

1. Sample ψ ∼ Dir(λ)

2. For each topic z

a. Sample Φz ∼ Dir(β)

3. For each pseudo document

a. Sample θl ∼ Dir(α)

4. For each short text ds:

a. Sample a pseudo document l ∼ Multi(ψ):

b. For each word wi in ds:

i. Sample a topic z ∼ Multi(θl):

ii. Sample the ith word wi ∼ Multi(Φz)

I used the Tomotopy package in Python to perform the PTM using the PTModel functions whose implementation was based on the algorithms used in this article.

Topic modeling requires the number of topics to be specified. I ran several different experiments varying the number of topics from 15 to 45, with 5 as the step unit, and selected the final model in consideration of both the highest coherence values measuring semantic similarity between high scoring words in the topic and the lowest perplexity values measuring how well the selected model predicts a sample. I settled with a solution that generated 35 topics with a coherence value score of 3,529.99 and a perplexity value score of .73, a best fitting model characterizing interpretability of the identified topics as well as predictability of the model (Bagozzi and Berliner, Citation2018; Syed and Spruit, Citation2017).

Analyses

shows the 35-topic solution, listing the 20 highest-ranked terms for each topic, the labels corresponding to the terms of each topic and the topic’s reference number. These 35 topics from the final model are the best characterizations of the collected corpus of COVID-19 tweets. They are presented in clusters around broader themes and appear in order from the themes with more attention to those with less. Within each theme, the corresponding topics are displayed in the order of their probability scores or the degree of attention. The themes constructed from the topics were (1) countries’ responses and records; (2) infections, testing, tracing, treatment, and social distancing; (3) vaccine and vaccination; (4) economic issues; (5) US military base in Korea and US forces; (6) human rights; (7) youth and culture; and (8) technology.

Table 1. Topic keywords and labeling.

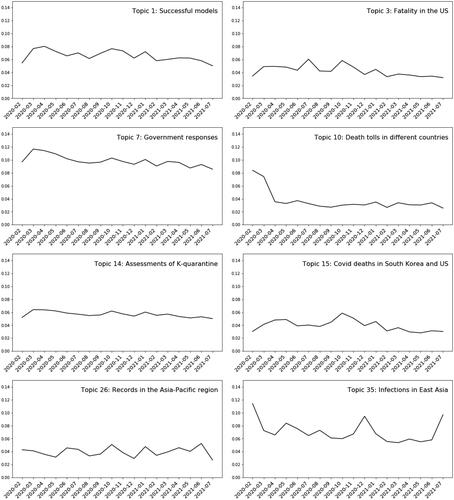

Countries’ responses and records topics

Seven of the 35 topics that emerged from the tweet corpus reflected the theme of countries’ responses and records with the highest probability scores. These tweets discussed countries’ responses to the pandemic and their records of infection and death under the following topics: successful models (Topic 1), fatalities in the United States (Topic 3), government responses (Topic 7), death tolls in different countries (Topic 10), assessment of K-quarantine (Topic 14), COVID-19 deaths in South Korea and the United States (Topic 15), records in the Asia-Pacific region (Topic 26), and infections in East Asia (Topic 35). The topics in this cluster reflect Twitter users’ concerns about and interest in how countries, including their own, responded to the pandemic and how their performances might have been compared with the South Korean response (see ).

The topic of fatalities in the United States, for example, included the words population, country, Trump, United States, president, test, world, China, Germany, Italy, and fatality. These terms reflect a clear concern about COVID-related fatalities in countries around the world, including the United States. One tweet with the largest topic score under this topic went as follows: “South Korea, population 51 million. South Korea has had 2,073 covid deaths. The US, in reality, has around 800,000. How do you explain this?” Another states, “Just having a look at the case fatality rates in different countries. Apparently, you want to live in New Zealand, Sweden, or South Korea.”

Although several topics under the category of countries’ responses and records reflected some understanding of governments’ responses compared with South Korea as a reference, Topic 14, assessment of K-quarantine, refers exclusively to the South Korean strategy, with terms such as response, system, great, effort, quarantine, safe, privacy, and strategy. The tweet that reflected Topic 14 with the highest probability stated, “Why does South Korea have a better COVID response? Because they have a better government system and a better economic system. Why is our country not doing well?” By contrast, under Topic 35, infections in East Asia, Twitter users were alarmed by the recent surges in South Korea and other Asian countries during the third and fourth waves of the pandemic. These tweets criticized the once-touted Asian collectivist model with representative messages such as, “Once a model in fighting the pandemic, the country has been slow to vaccinate its people, even as it is being hit by its worst-ever wave of infections”

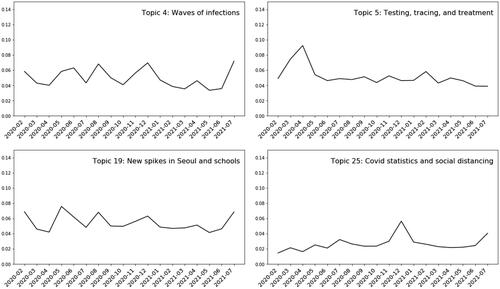

Infections, testing, tracing, treatment, and social distancing topics

Topics 4, 5, 19, and 25 captured issues concerning the theme of infections, testing, tracing, treatment, and social distancing. Topic 4, waves of infection, comprised the terms infection, wave, second, virus, country, disease, third, surge, outbreak, and record, reflecting the later spread of the virus in South Korea in contrast with the country’s impeccable initial record. The topic terms in this tweet dominated the word assignment: “Once a COVID success story, South Korea sweats through summer of Delta surge.” Topic 19, new spikes in Seoul and schools, reflected the ongoing spread and related anxiety and new restrictions with a focus on metropolitan Seoul and in schools. One user posted a tweet wondering if the South Korean government had really banned public music events with music above 180 bpm due to COVID-19, and another was critical of the unprecedented new measures banning playing music faster than 120 bpm in Seoul gyms to curb rising COVID-19 cases (see ).

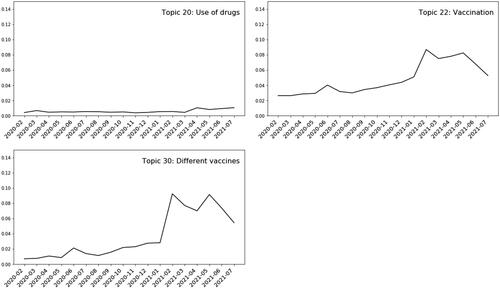

Vaccines and vaccination topics

Undoubtedly, vaccines and vaccination received tremendous attention from global Twitter users who mentioned both COVID and South Korea. Topics 20, 22, and 30 constituted the vaccine theme, and these comprised discussions of the availability and efficiency of certain drugs, vaccination in North Korea, users’ concerns about the delayed vaccine rollout, and South Korea’s online vaccination reservation system. The top words under Topic 22, vaccination, were vaccine, vaccination, treatment, North Korea, company, and emergency. A tweet exhibiting this topic with the highest probability criticized the country’s low vaccination record: “South Korea currently ranks second-to-last among OECD member countries, with only 13.49 percent of its population fully vaccinated, and critics have argued that the government dragged its feet in rolling out the national vaccination campaign” (see ).

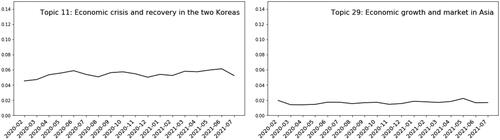

Economic issues topics

Topics 11 and 29 were the most straightforward to interpret because these involved the impacts of COVID-19 on national and global economies. Topic 11, economic crisis and recovery in the two Koreas, contrasted South Korea’s relatively quick recovery from the economic downturn to North Korea’s experience of one of its worse economic crises in two or three decades. A tweet from this topic with high word assignment observed, “North Korea’s economy took its biggest hit in 23 years in 2020 because of continued UN sanctions, COVID-19 lockdowns and bad weather.” Whereas Topic 11 depicted economic difficulties and recovery in the context of the two Koreas, Topic 29 focused on what occurred in Asian countries such as China, Japan, and India during the pandemic. The most highly ranked terms include market, impact, China, Japan, stock, economy, global, Asia, economic, growth, and pandemic (see ).

US camp and the military

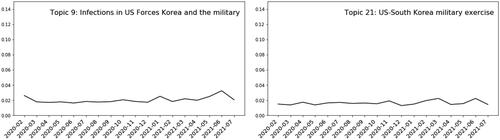

Two topics related to infections in the military, particularly on bases such as US Forces Korea (USFK) and in the Korean military, which was known as a major cluster of COVID-19 infections. Topic 9, infections in US Forces Korea and the military, encompassed the terms member, positive, service, arrival, USFK, quarantine, military, and soldier. Tweets under this topic referred to USFK-affiliated individuals who had tested positive for COVID-19 after arriving in South Korea and delivered information on the vaccination statuses of the people associated with USFK, from US service members to South Korean employees. This topic also comprised episodes of infections within the military, including the scandalous infection of the Cheonghae Unit. By contrast, Topic 21, US–South Korea military exercise, reflects controversies on the proper scale for US–South Korea joint drills in the middle of the pandemic, with the highest-ranked terms being military booth, mask, trade, immunity, joint, free, office, herd, exercise, drill, and United States (see ).

Human rights-related topics

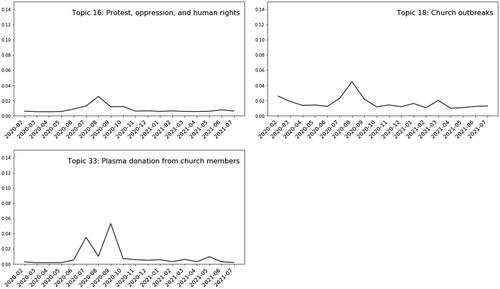

Given my priority of noting to what extent Twitter users attended to human rights issues compared with more general health-related issues, the PTM results show that even though the human rights-related topics (Topics 16, 18, and 33) were clearly meaningful, they received much less attention than other topics that dealt with government responses, health measures, vaccines, and economic issues. Furthermore, the discussion on surveillance, restrictions on assembly, and stigmatization of religious groups tended to appear rather briefly and soon subside, as shown in Topics 16, 18, and 33 in . All of this suggests that rights issues remained largely parochial in South Korea-focused COVID-19 tweets and in public discussions of COVID-19 and South Korea (see ).

Nevertheless, these topics are highly important ones for this study, because they represent the public discussion of South Korean government measures toward religious groups, political dissidents, and protesters, Twitter users’ assessments of those measures, and how international society—including the United Nations—responded to the measures. The top words under Topic 16, protest, oppression, and human rights, included international, religious, movement, concern, oppression, religion, raise, call, NGOs, human rights, stop, and destruction, not only specifying key actors and issues with movement, religion, and NGOs, but also negatively portrayed what occurred with words such as oppression, stop, and destruction. A representative tweet whose terms contained the highest probability of this topic urged that “international leaders and human rights NGOs call on South Korea to stop oppression of minor religion for COVID-19.”

Topic 33, plasma donation from church members, included terms related to plasma donation from Shincheonji, a church group that was largely responsible for the first wave of the pandemic in South Korea and thus became the target of public disdain—such as plasma, church, donation, shincheonji, cure, recovered, and factcheck. Challenging the public’s view that this church group was resistant to blood donation, a tweet with the highest probability of this topic called attention to “third plasma donation drive of 4,000 church members who have fully recovered from COVID-19” using the hashtag #StopFakeNews.

Youth and culture

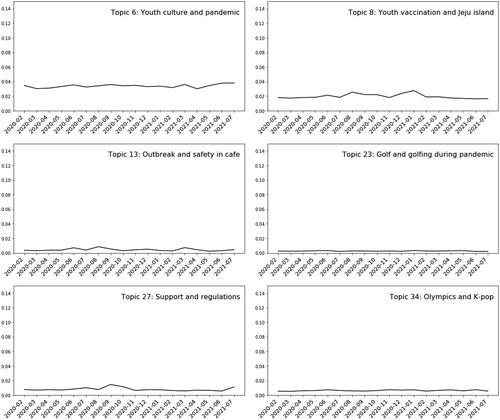

Several topics were associated with the spread of the virus and its impacts on everyday life (Topics 6, 8, 13, 23, 27, 34) with relatively lower probability scores. Topic 6, youth culture and the pandemic—with top words such as online, group, event, food, pandemic, concert, trip, friend, video, university, music, and sport—focused on the rapid spread of the virus among youth, with their low vaccination rates, and its impacts on schooling, jobs, businesses, sports, and other cultural activities. One tweet expressed concerns about small businesses that were hard hit by semi-shutdowns and other restrictive measures: “Small business owners in South Korea are being driven out of business as the country has gone into the toughest.” Another representative tweet discussed young people’s economic difficulties: “Koreans in 20s and 30s give up job search amid prolonged COVID-19 crisis” (see ).

Topic 13, outbreak and safety in cafes—with top words such as café, outbreak, masks, response, Blackpink, and Starbucks—highlighted episodes of the infection that occurred in cafés as popular public gathering locations where people enjoy K-pop artists such as Blackpink; this topic warned of the dangers of not wearing masks in such indoor settings. Topic 23, golf and golfing during the pandemic, highlighted the increasing popularity of golf among young people during the pandemic. Topic 27, support and regulations, lamented the absurd regulations that were put into place, including the ban on outdoor cultural festivals as well as the ban on playing loud music in gyms. One representative tweet complained, “No music over 120 BPM allowed in gyms in South Korea? Mimicking their neighbours to the North.” Topic 34, the Olympics and K-pop, touched on Japan’s response to the pandemic during the summer Olympic games with a negative tone and discussed the popularity of K-pop despite the unprecedented pandemic crisis.

The use of technology

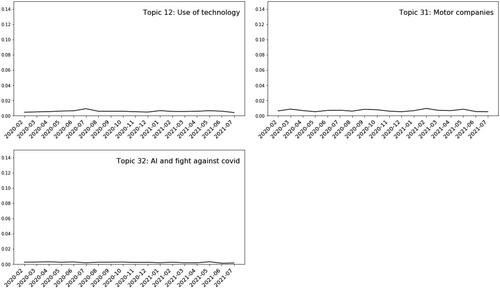

The final meaningful category of topics concerned technology, which has some relation to human rights issues—for instance, privacy. It is worth noting, however, that the topic scores and overall probabilities assigned to these topics were the lowest for topics in any other categories. Two topics related to technology: the use of technology by motor companies and AI and the fight against COVID-19 (see ).

Topic 12, use of technology, had the top words podcast, technology, surveillance, credit, casino, αι, tech, startups, success, and security and highlighted the potential uses of technology for surveillance in the context of successful containment of the virus during a pandemic. The tweet with the highest probability for this topic remarked, “Only South Korea used app-based contact tracing right. Benchmark for a successful COVID-19 contact-tracing operation is to trace and quarantine 80% of close contacts within 3 days of a case being confirmed.” However, criticizing unbearable workloads, one Twitter user posted, “South Korea’s delivery workers go on strike against overwork amid COVID-19.”

Topic 32, artificial intelligence (AI) and the fight against COVID, brought to the fore the use of AI-assisted technologies in fighting the spread of the COVID-19 in South Korea; terms included virus, intelligence, AI, expert, sonn, artificial, jung, lockdown, answer, popular, tech, fast, kore, park, diplomat, ml, drive-thrus, attack, and machine learning. A tweet in which this topic dominated succinctly summarizes the country’s winning strategy: “South Korea Winning the Fight Against Corona Virus Using #BigData And #AI by Go to #MachineLearning #Artificialintelligence.” Topic 31 was motor companies and referred to automobile companies such as Hyundai as well as disruptions to the global supply chain.

Tweeter users’ discussion of human rights in a nutshell

Here I asked whether Twitter users’ attention to human rights topics corresponded with or could be predicted by my discussion of the rights debate that occurred in South Korea. The results from the PTM largely confirmed my expectations of global Twitter users’ discussion of central human rights issues, such as surveillance, stigmatization, and the right of assembly. First, stigmatization was a significant concern, as indicated by the prevalence of several topics (16, 18, and 33) that consisted of terms associated with religious groups—for example, shincheonji, church members, the youth, gym users, participants of cultural events, and COVID patients.

Second, surveillance was a key issue across different topics regarding privacy in the context of the K-quarantine (Topic 14) and was viewed as an inevitable concern once technology was being used to trace the spread of the disease. Contrary to my expectation, however, Twitter users paid relatively little attention to the government’s suppression of the right of assembly. Nonetheless, government’s control over rights to assembly and association could be inferred from some of the dynamics of topic shifts; consider, for example, the apex of Topic 18, church outbreak in August 2021, when the government sought to crack down on protesters linked to religious groups and churches, using COVID-19 as an excuse to control peaceful protesters. This episode is consistent with what Badran and Turnbull (Citation2022) report in this volume, regarding how the state could use the pandemic to crush dissent using public health emergencies. The conservative church groups critical of President Moon’s tough stance on religious freedom insisted on maintaining a street presence, but that invited a convenient pretext to shut down ongoing dissent.

With the topic model approach revealing unexpected patterns or semantic meanings of the texts, the analyses permitted reflecting on newer, unanticipated forms of rights infringements. The findings from the PTM indicated that existential threats stemming from the pandemic prompted newer forms of government intervention in civic life. When South Korea set another new high during the second and third waves, for example, the Ministry of Health and Welfare announced the unprecedented new measures of banning playing music faster than 120 bpm in gyms in Seoul and prohibiting music events with music above 180 bpm. These measures might be understood as extending regulations that were already placed on public spaces, such as the restricted maximum capacities and hours of operation for cafes, bars, and restaurants. Yet global Twitter users often ridiculed and fiercely criticized these government measures as actively encroaching on civic life.

Other unforeseen examples of abuses were linked to workers’ rights and rights with economic activities. Although they did not rise to the frequency of a formal topic or theme and did not emerge as one of the economic issues identified by PTM, the worsening working conditions of delivery workers received sizable attention from Twitter users. A sizable number of tweets expressed empathy toward platform workers who went on strike against overwork amid COVID-19 and sympathized with members of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions who marched in major cities amid police blocks; these workers were marching for safe employment and better working conditions. The other notable theme I identified that did not fall under a topic cluster concerned what was happening to owners of restaurants, cafes, and other small businesses who were most negatively affected by government restrictions on operating hours and curfews. Alarmed by the impacts of government measures that severely hampered economic activity for small business owners, citizens began to be wary of the unfairness of government mandates on operating hours and their consequences for economic freedom.

Conclusion

South Korea’s battle against COVID-19 has been triumphant, as attested to by global Twitter users’ opinions of the country’s efficient responses and the corresponding topics that emerged in a text analysis by algorithm. In fact, the country has maintained an enviable track record of many fewer cases of infection and deaths than in other high-income countries. Furthermore, South Korea experienced only minimal damage to its economy (only a −1 percent GDP growth rate) in 2020, a feat achieved by no OECD countries. The question arises then of whether South Korea’s public health measures for achieving this success were consistent with international human rights norms.

If one prioritizes such paramount rights as the right to life and the right to health, the answer is clearly positive: many lives were saved and individuals protected from the novel coronavirus with the government’s strict measures. Compared, however, with how other interconnected yet competing rights are prioritized—such as freedom of expression, assembly rights and privacy protection—the answer is not necessarily positive. My findings from the PTM of 87,487 tweets concerning COVID-19 and South Korea indicate that COVID-19-related issues of human dignity, personal information protection, and assembly rights remain parochial compared with what users considered the more important issues of public health policies: testing and tracing, vaccinations, economic issues, and the youth. Rights protection appeared at odds with the seemingly larger target of protecting the public’s health and safety (Roberto et al., Citation2020).

Persons who were infected with COVID-19 and those who were suspected of infection were stigmatized to inform the public of the danger of the disease, but this tactic indiscriminately targeted religious groups, young people, protesters, and citizens who refused vaccination. In addition, the South Korean government actively employed surveillance to collect personal information on the public using its advanced AI technologies. Contrary to our conventional understanding of universal human rights as interconnected and indivisible, we undoubtedly witnessed tradeoffs among different kinds of rights in the case of South Korea. In this volume, Chiozza and King (Citation2022) make the case that, in the face of global health emergencies, governments have restricted some rights to protect other types of rights.

We are not equipped with tools to measure how South Korea’s handling of a myriad of human rights might compares with other high-income countries. Considering that savvy governments in most countries—autocratic and democratic—used the pandemic as an excuse to restrict civil liberties and rights, we simply cannot know where South Korea lands on the spectrum. The impacts of restricting a set of rights for the sake of protecting other prioritized rights can be only gauged through future research (Eck and Hatz, Citation2020). What I found, however, were concerned voices, feelings, and judgments from tens of thousands of Twitter users worldwide about the ways in which South Korea—often celebrated as a model country for the battle against the coronavirus—responded to this unprecedented project of humanity, and the collective opinion was consistent with my own evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of this Asian country’s path to managing COVID-19.

As Murdie (Citation2022) points out in this volume, it is crucial for a country to take rights-consistent public health measures because it could make citizens less likely to see the right to health as a counter to other civil and political rights. The will of the state then would spur the will of people, a launchpad for improved human rights.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jeong-Woo Koo

Jeong-Woo Koo is a professor of sociology at Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, South Korea. His research examines how world cultural processes shape state, organizational, and individual outcomes. His recent focus lies in the use of topic models to show the dynamic evolution of human rights norms and online users’ attitudes toward rights. He is currently working on a project addressing machine learning models for detecting online hateful expressions.

References

- Badran, S., & Turnbull, B. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and authoritarian consolidation in North Africa. Journal of Human Rights, 21(3), 263–282.

- Bagozzi, B. E., & Berliner, D. (2018). The politics of scrutiny in human rights monitoring: evidence from structural topic models of US State Department Human Rights Reports. Political Science Research and Methods, 6(4), 661–677. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2016.44

- Blei, D. M. (2012). Probabilistic topic models. Communications of the ACM, 55(4), 77–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/2133806.2133826

- Botto, K. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic and South Korea’s global leadership potential. [white paper]. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Boyd-Graber, J., Hu ., & Mimno, D. (2017). Applications of topic models. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval, 11(2–3), 143–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1561/1500000030

- Brysk, A. (2022). Pandemic patriarchy: The impact of a global health crisis on women's rights. Journal of Human Rights, 21(3), 283–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2022.2030209

- Cha, V. (2020). Asia’s COVID-19 lessons for the West: Public goods, privacy, and social tagging. The Washington Quarterly, 43(2), 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2020.1770959

- Chenoweth, E. (2022). Can nonviolent resistance survive COVID-19? Journal of Human Rights, 21(3), 304–316.

- Chilton, A., Cope, K. L., Crabtree, C., & Versteeg, M. (2020). The normative force of higher-order law: Evidence from six countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available at SSRN 3591270.

- Chiozza, G., & King, J. (2022). The state of human rights in a (post) COVID-19 world. Journal of Human Rights, 21(3), 246–262.

- Chung, K., & Choe, H. (2008). South Korean national pride: Determinants, changes, and suggestions. Asian Perspective, 32(1), 99–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2008.0032

- Dieng, A. B., & Ruiz, F. J., & Blei, D. M. (2019). The dynamic embedded topic model. Cornell University. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.05545: 1–17.

- DiMaggio, P., Nag, M., & Blei, D. M. (2013). Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of US Government Arts Funding. Poetics, 41(6), 570–606. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.004

- Duić, D., & Sudar, V. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the free movement of persons in the EU. EU and Comparative Law Issues and Challenges Series (ECLIC), 5, 30–56.

- Eck, K., & Hatz, S. (2020). State surveillance and the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Human Rights, 19(5), 603–612. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2020.1816163

- Forman, L., & Kohler, J. C. (2020). Global health and human rights in the time of COVID-19: Response, restrictions, and legitimacy. Journal of Human Rights, 19(5), 547–556. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2020.1818556

- Government of the Republic of Korea (ROK) (2020, 31 March). Tackling COVID-19: Health, Quarantine, and Economic Measures: Korean experience. https://ecck.or.kr/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Tackling-COVID-19-Health-Quarantine-and-Economic-Measures-of-South-Korea.pdf

- Hatcher, W. (2020). A failure of political communication not a failure of bureaucracy: The danger of presidential misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6-7), 614–620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020941734

- Hong, L., & Davison, B. D. (2010). Emperical study of topic modeling in Twitter. In Proceedings of the first workshop on social media analytics. ACM. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1964858.1964870

- Kavanagh, M. M., & Singh, R. (2020). Democracy, capacity, and coercion in pandemic response: COVID-19 in comparative political perspective. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(6), 997–1012. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8641530

- Kim, M.-H., Cho, W., Choi, H., & Hur, J.-Y. (2020). Assessing the South Korean Model of emergency management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Studies Review, 44(4), 567–578. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2020.1779658

- Koo, J.-W., & Choi, J. (2019). Polarized embrace: South Korean Media Coverage of Human Rights, 1990–2016. Journal of Human Rights, 18(4), 455–473. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2019.1629888

- Lee, H., Noh, E. B., Choi, S. H., Zhao, B., & Nam, E. W. (2020). Determining public opinion of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea and Japan: Social network mining on Twitter. Healthcare Informatics Research, 26(4), 335–343.

- Lee, S. M., & Lee, D. H. (2020). Lessons learned from battling COVID-19: The Korean experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7548. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207548

- Lynam, T. (2016). Exploring social representations of adapting to climate change using Topic modeling and Bayesian networks. Ecology and Society, 21(4), 16. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08778-210416

- Murdie, A. (2022). Hindsight is 2020: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for future human rights research. Journal of Human Rights, 21(3), 354–364.

- Oh, B. -I., Chang, Y., & Jeong, S. (2020). COVID-19 and the right to privacy: An analysis of South Korean Experiences [White Paper]. Korean Progressive Network Jinbonet and Institute for Digital Rights.

- Ordun, C., Purushotham, S., & Rraff, E. (2020). Exploratory analysis of COVID-19 tweets using topic modeling, umap, and digraphs. Cornell University. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.03082: 1–19.

- Park, B., Murdie, A., & Davis, D. R. (2019). The (co) evolution of human rights advocacy: Understanding human rights issue emergence over time. Cooperation and Conflict, 54(3), 313–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836718808315

- Park, S., Choi, G. J., & Ko, H. (2020). Information technology-based tracing strategy in response to COVID-19 in South Korea-privacy controversies. JAMA, 323(21), 2129–2130.

- Roberto, K. J., Johnson, A. F., & Rauhaus, B. M. (2020). Stigmatization and prejudice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 42(3), 364–378. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2020.1782128

- Ryan, M. (2020). In defense of digital contact-tracing: Human rights, South Korea and COVID-19. International Journal of Pervasive Computing and Communications, 16(4), 383–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPCC-07-2020-0081

- Spadaro, A. (2020). COVID-19: Testing the limits of human rights. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 11(2), 317–325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.27

- Syed, S., & Spruit, M. (2017). Full-text or abstract? Examining topic coherence scores using latent dirichlet allocation. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA) (pp. 165–174). doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/DSAA.2017.61

- Travaglino, G., & Moon, C. (2020, May 26). Explaining compliance with social distancing norms during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of cultural orientations, trust and self-conscious emotions in the US, Italy, and South Korea. PsyArXiv.

- Wicke, P., & Bolognesi, M. F. (2020). Framing COVID-19: How we conceptualize and discuss the pandemic on Twitter. PloS One, 15(9), e0240010.

- Yamin, A. E., & Habibi, R. (2020). Human rights and coronavirus: What’s at stake for truth, trust, and democracy. Health and Human Rights Journal.

- Yi, J., & Lee, W. (2020). Pandemic nationalism in South Korea. Society, 57(4), 446–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-020-00509-z

- Yin, H., Yang, S., & Li, J. (2020). Detecting topic and sentiment dynamics due to COVID-19 pandemic using social media. In International conference on advanced data mining and applications (pp. 610–623). Springer.

- You, J. (2020). Lessons from South Korea’s COVID-19 policy response. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6–7), 801–808. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020943708

- Zuo, Y., Wu, J., Zhang, H., Lin, H., Wang, F., Xu, K., & Xiong, H. (2016). Topic modeling of short texts: A pseudo-document view. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 2105–2114). ACM.