Abstract

In this article, we introduce a new dataset on financial support for the International Criminal Court (ICC) and examine how this support has changed over its two decades of existence. We first consider how the ICC’s overall budget has changed over time. Then, we explore the evolution of support from individual donor governments. In addition, given former Prosecutor Bensouda’s emphasis on the effective investigation and prosecution of sexual and gender-based crimes, we examine the extent to which ICC funding is consistent with its apparent commitment to gender justice. Our research contributes to debates about the cost of justice, donors and norm diffusion, South–North clashes over the definition and delivery of justice, and gender mainstreaming within costly international justice processes. We argue that the level of funding state parties and other bodies allocate to particular forms of justice is a better proxy for their commitment to justice than their rhetoric, and conclude that the patterns of funding seen at the ICC support the claim that the Court remains, to a significant extent, a tool of powerful states.

Introduction

Funding issues are central to many controversies facing the International Criminal Court (ICC or the Court). Some criticism focuses on the Court’s internal workings. Among other things, it works slowly, and the prosecution’s cases are often underwhelming despite the resources invested in lengthy investigations (Guilfoyle, Citation2019; Kersten, Citation2016). Critiques from the Global South see Western countries using the power of the purse to direct the Court’s attention away from the alleged war crimes of their own citizens and toward crimes in Africa, in particular (Clarke, Citation2019; Murithi, Citation2012; New African, Citation2012). Other critics are concerned about value for money or the operation of financial interests in the Court. They consider the privatization of justice and the opportunity costs of the money spent over two decades on 30 cases across 17 situations, as of early 2022 (Abebe, Citation2014; Kendall, Citation2015). Still others fault the ICC for devoting insufficient attention and resources to the needs of victims (Moffett & Sandoval, Citation2021; Redress, Citation2019). Thus, many of the criticisms of the Court are rooted in questions of finance.

Funding pressures became particularly acute in the ICC’s second decade. During that time, the global economy was buffeted by the 2008 Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in 2020. State parties also have grown increasingly frustrated with the Court’s meager accomplishments. They simultaneously want it to be more efficient and to expand the number of investigations. More generally, states seek to advance their interests through international courts like the ICC. As Hillebrecht (Citation2021, p. 114) argued, constraining the financing of international courts enables governments to profess adherence to international norms by being state parties while maintaining control behind the scenes.

States may also increase their funding of courts to discipline rivals, or to claim the ethical high ground while avoiding the costs of potentially more effective policy options. The response of many states to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine is illustrative. Through March and April 2022, 43 mostly European state parties to the Rome Statute (which established the ICC) referred the situation in Ukraine to the ICC. When Prosecutor Karim Khan issued a call for financial support in March 2022, 20 countries replied by mid-May (Office of the Prosecutor, Citation2022). Even the United States is exploring how it can support ICC prosecutions in Ukraine. As of May 2022, bipartisan negotiations in Congress were examining how to provide financial assistance to the Court without violating existing US law designed to limit cooperation with the ICC (Goodman, Citation2022).

For its part, the ICC has the impossible task of delivering impartial justice while depending on capricious states to keep the lights on, to say nothing of collecting evidence and apprehending suspects. The ICC frequently does not do itself any favors, however. For example, it has a long record of underestimating resource needs (Cannock & O’Donohue, Citation2018). Evenson and O’Donohue (Citation2015) summarized the consequences of the budget dynamics prior to the invasion of Ukraine thus:

[T]he ICC’s decision-making has been driven by pressure from a small number of states to minimize costs and to even impose zero-growth, regardless of increasing demand and workload. This has undermined the court’s performance, allowed states to focus their budgetary negotiations on artificial bottom lines, and distorted understandings of the court’s real resource needs.

Despite the centrality of funding to the Court’s success, remarkably little attention has explicitly focused on broader budgetary trends. This article introduces a new dataset that examines the evolution of the Court’s funding.Footnote1 Furthermore, we explore how Court finance has been used to advance different political agendas and document budget politics within the Court. Finally, we examine patterns in funding for initiatives designed to increase gender equality, gender justice, and the prosecution of sexual and gender-based crimes (SGBC) in order to evaluate whether the Court’s budget reflects its stated priorities. Our findings largely support postcolonial and feminist criticisms of the ICC.

The politics of the ICC

Although discontent emerged within a few years of the Court’s creation in 2002 (Ainley, Citation2011; Mamdani, Citation2008; Mills, Citation2012; Waddell & Clark, Citation2008), as the end of the ICC’s first decade approached, it faced a growing chorus of criticism. Although rarely explicitly stated in these terms, many concerns about the Court are rooted in budgetary control by European powers. For many observers, Western countries using their resources to interfere in the internal affairs of countries in the Global South evokes the colonial past. In the eyes of some critics, the ICC represents a tool with which Western countries use law to continue to dominate the rest of the world (Clarke, Citation2019). As Mahmood Mamdani noted, the ICC “is dancing to the tune of Western States. Given Africa’s traumatic experience with the very same colonial powers that now, in effect, direct the ICC, it is an unfortunate case of déjà vu” (New African, Citation2012).

Tim Murithi (Citation2012) has been most explicit in indicting finance as a cause of the “African Criminal Court” critique. He argued that the Court is beholden to its primary funders, that is, primarily Western countries. Moreover, African states lack the power to serve as a counterweight, either within the Assembly of States Parties (ASP) or in international relations more generally.

Allegations extend to personnel. Some argue that funding gives European powers control over staffing many of the most important positions within the Court (Kimenyi, Citation2013). The implication is that wealthy state parties angle to install their citizens in positions to advance their interests. More generally, financial leverage may enable Western countries to ensure that key personnel have views that align with their own preferences.

Poor countries’ primary weapon to counter financial and political control is the withdrawal threat. Burundi and the Philippines took this path. The Gambia and South Africa deposited notifications of withdrawal, but both subsequently rescinded these notifications before they took effect. Below, a new dataset on ICC funding is used to outline the nature of ICC funding and trends over time, and to draw preliminary conclusions on the extent to which the criticism of the ICC as a political or neocolonial institution is warranted.

The ICC budget process

In simplest terms, the ICC’s budget is set in a three-step process. First, the Court itself proposes a budget for the coming year.Footnote2 The proposal is then reviewed by an independent 12-member body, the Committee on Budget and Finance (CBF), to which civil society organizations are invited to contribute at the CBF annual session. Finally, the original budget proposal and the CBF’s recommendations are scrutinized by the ASP, which ultimately sets the Court’s budget on the basis of one country, one vote.Footnote3

Once the overall budget is set, state parties’ individual contributions are calculated. During treaty negotiations, there was a proposal to fund the Court through the United Nations. The primary opponents were the United Nations’s biggest contributors—namely the United States, Germany, and Japan—and the idea was abandoned (Schabas, Citation2020). However, assessed contributions for the Court are calculated in the same way as for the United Nations. Per Article 117 of the Rome Statute, “contributions of States Parties shall be assessed in accordance with an agreed scale of assessment, based on the scale adopted by the United Nations for its regular budget and adjusted in accordance with the principles on which that scale is based.”

In other words, states are assigned a proportion of the overall budget that is essentially based on the size of their economies. As such, our data available on the Harvard Dataverse site show that the ICC’s largest funders are large European economies, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Brazil.

Funding politics

Funding has always been a challenge for the ICC to effectively fulfill its mandate. The situation became more acute in the last decade as growing demand for the Court’s services has coincided with states’ greater reticence to pay. Each new episode of mass violence generally brings calls for ICC investigation, potentially adding to its workload. The ICC has a contingency fund for unexpected expenses, but it remains underfunded as rules require it only be replenished when it goes below €7 million (Corey-Boulet, Citation2011). At the same time, criticism of the slow pace of investigations raises questions about whether spending more on the Court is prudent. The case for growing funding became harder still as the global economy has been buffeted by economic crises.

Funding constraints have had pernicious effects on the Court’s ability to deliver on its core mission of holding perpetrators accountable and realizing justice for victims. Among other things, victim participation has been curtailed by resource limitations (Corey-Boulet, Citation2011). The quality of the cases also has suffered. After Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda took office in 2012, budgetary constraints led to some fateful personnel choices. Investigators were rotated to different investigations based on the urgency of need. Preliminary examinations were conducted on a “stop–go” basis in which they were carried forward as far as possible and then put on hold as staff shifted to other situations. Some observers have argued that budget shortfalls contributed to the collapse of some of the ICC’s earliest cases (O’Donohue, Citation2020). The Independent Expert Review (Citation2020, p. 312) summarized the budget tension between the Court and the ASP thus:

To many in the Court, States Parties seem to be more interested in reducing the budget than in providing the resources needed for the Court to function fully. Moreover, the ASP is seen as intent on micro-managing the operation of the Court. … For their part, many States Parties are frustrated with the Court, which they consider does not deliver full value for the funding their taxpayers provide, in terms of reducing the incidence of the crimes set out in the Rome Statute, through convictions and deterrence.

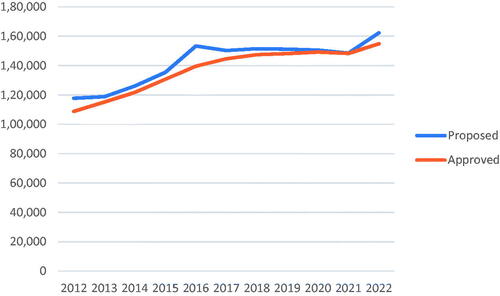

provides an overview of ICC budget figures since 2012. Although the ICC’s budget might appear large, many observers argue that it is insufficient to conduct the limited number of investigations that have been launched (O’Donohue, Citation2020). In fact, the funding allocated by several countries toward domestic atrocity crime investigations dwarf what is provided to the ICC (Ford, Citation2017). In addition, as of 2015, the ICC Office of the Prosecutor’s (OTP’s) budget was €8 million less than the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia at its peak (Evenson & O’Donohue, Citation2015).

There is some question about whether the insufficiency of the budget is caused by state parties using the purse strings to control Court behavior, or the Court failing to adequately estimate its needs. As Hillebrecht (Citation2021, p. 129) highlighted, “The ICC is in a perennially difficult position with respect to budgeting. If the Court asks for too much, they are painted as greedy. If they ask for too little, they are unable to fulfill their legal mandate. The Court’s budgetary mismanagement and miscalculations have been ‘unforced errors.’”

As documented below, evidence suggests the ASP having a markedly greater impact on the Court’s performance (and reputation). Regardless of whether there are institutional failures of the Court in drafting budget proposals, as illustrates, it is clear that, particularly through 2016, there was a growing divergence in what the Court requested and what the ASP approved. Convergence may represent the Court being (temporarily) cowed by the ASP.

Some of the ICC’s biggest funders began pushing for zero budget growth as early as 2008, with the global financial crisis tightening fiscal belts. Some of this policy’s strongest proponents were wealthy Western countries. From the start, the Coalition for the International Criminal Court (CICC) warned that zero growth “would undermine the effectiveness of the court’s work and would curtail its ability to respond promptly to situations where crimes are committed” (Corey-Boulet, Citation2011). Initially, Prosecutor Bensouda appeared successful in arguing for more resources. During her first four years in office (2012–2016), the OTP’s budget increased by 63 percent, to €43 million (O’Donohue, Citation2020). Then, things began to change.

In 2016, a group including the ICC’s largest financial backers renewed efforts to curb the Court’s growth,Footnote4 citing internal inefficiencies and the global financial crisis (Evenson & O’Donohue, Citation2016). This “zero nominal growth” (ZNG) model would fix the budget for several years without even adjusting for inflation (CICC, Citation2016). Some observers have argued that state parties’ sudden willingness to enforce budget restrictions in 2016 was tied to the contentiousness of the ICC’s activities at the time. The move coincided with the OTP’s more provocative moves to widen its gaze beyond Africa, which threatened the interests of the United States, United Kingdom, and Russia. In 2014–2015, Bensouda opened preliminary examinations in Palestine and Ukraine and accelerated the preliminary examination in Afghanistan (O’Donohue, Citation2020). At the same time, state parties sought to forestall Burundi and South Africa’s withdrawal from the Rome Statute by placating their criticisms that the Court was too focused on Africa. Thus, while insisting on a zero-growth budget policy, states simultaneously called on the OTP to expand its investigatory reach. As Elizabeth Evenson and Jonathan O’Donahue (Citation2016) argued, “The hypocrisy here is at a new level—supporting further ICC investigations (importantly, outside of Africa) one day but refusing to fund them the next.”

Pressure from the ASP continued. The Court has been asked to present “sustainable” budget proposals that include increases only after exploring all possible avenues for savings and efficiencies.Footnote5 State parties further requested inclusion of an annex to the program budget documenting the Court’s savings and efficiency accomplishments in the current year and plans for the next.Footnote6 State parties soon went one step further. At its 2019 session, the ASP asked for even more detailed accounting of savings and efficiencies in future budgets.Footnote7 Thus, the Assembly has shown increasing willingness to micromanage ICC spending alongside its insistence that the Court reduce spending, with state parties all the while maintaining their rhetoric that the Court should expand its geographical reach.

Waning financial support has had measurable effects on the ICC’s ability to deliver justice. The OTP cited budgetary constraints as the reason it “hibernated” preliminary examinations in Nigeria and Ukraine and to justify the selective investigation of crimes in Afghanistan (Amnesty International, Citation2021; Anderson, Citation2021). An Independent Expert Review (Citation2020) recently commissioned by the ASP concluded that the OTP’s Investigation Division was “severely under-resourced,” having 87 fewer full-time staff than estimated to be necessary to effectively manage its current workload. It further concluded that the budget process was flawed. Per the report, “it is apparent that the trust relation between the Court and the ASP (including its subsidiary bodies) can and should be improved. … [T]here seems to be a perception within some quarters of the Court that States Parties are using the budget process to interfere with the Court’s cases” (Independent Expert Review, Citation2020, p. 106).

Nonetheless, rather than urge the Assembly to increase funding, the report concluded that “the Court should accept the legitimate authority of the ASP to decide its budget and should tailor its activities to match the resources available” (Independent Expert Review, Citation2020, p. 313). The report further recommended that, if necessary, “Feasibility-related factors should be seriously considered after the opening of an investigation. Should more situations reach the investigation stage without sufficient resources available to conduct serious investigations, the OTP should hibernate de-prioritised investigations” (Independent Expert Review, Citation2020, p. 313).

Cannock and O’Donohue (Citation2018) argued that the Court has meekly acquiesced to the situation and now in its budget requests asks for what it thinks state parties will provide rather than undertaking rigorous assessment of what it actually needs. Clearly, however, the Court is deeply concerned about zero nominal growth’s operational and reputational consequences. It has tried to fight back as best as it can. For instance, in its proposed 2018 budget, the Court lamented:

A ZNG budget will cause the [OTP] to lose staff and operational capability. The detrimental effect of this—in particular, delays in investigations and prosecutions—will ultimately hamper the ability of the Court to deliver on core mandates. A ZNG budget will undercut the Registry’s capacity to provide vital services to the OTP and the Court as a whole, including in the key area of victim and witness support. … The Judiciary will be negatively affected by these constraints on OTP and the Registry, not least in terms of delay and inefficiencies in proceedings. … In sum, a ZNG budget is not commensurate with the reality of the Court’s operations, and will severely undermine the effective discharge of its mandate as set by the Rome Statute.Footnote8

What does the control of the ICC’s resources mean for the validity of the criticisms against it? Before the mass 2022 Ukraine referral, the ICC was becoming increasingly constrained by its largest donors, as its budget remained relatively static while investigations were increasing, and evidence was building in multiple cases that would justify trials. Bensouda opened 10 investigations during her tenure as prosecutor, including five proprio motu and eight outside the African continent.

Yet, despite the drive to move “out of Africa,” every case to reach trial at the ICC has been drawn from its African investigations. The proprio motu situations and those referred by third-party states (e.g., Venezuela) or on contested territory (e.g., Bangladesh/Myanmar, Palestine, and Ukraine) are vastly more expensive to investigate, as the Court lacks the assistance of the state party concerned, or the state where the alleged crimes originated. The pressure on the ICC budget has had the effect, intended or not, of restricting the actual practice of trying cases to African situations. While establishing intent would be extremely difficult—state parties do not announce that they seek to protect the interests of the United States, United Kingdom, or Israel in insisting on conservative budgets—the donations that state parties have attempted to earmark for the Ukraine investigation demonstrate that when state parties support investigations, they are able to back up their support with financing (Office of the Prosecutor, Citation2022). That they have rarely ever done this in the Court’s history, including for UNSC-referred investigations, and never at this scale, suggests that their financial contributions are a reasonable proxy for their interests in international justice. Current attempts in the US Congress to find ways to fund the ICC, the jurisdiction of which the United States refuses to accept, also make the Court appear to be a tool of the wealthiest states in the international system (Goodman, Citation2022).

What does the ICC spend its money on?

provides a breakdown of proposed and approved budget line items for 2022 (see Harvard Dataverse for historical data). The Registry receives the biggest proportion of the budget, approaching 50 percent in many years. The Registry is the Court’s administrative backbone, managing everything from court records, library facilities, and support services for victims, witnesses, and counsel to external relations, security, and human resources. The OTP is the second largest line item, followed by the Judiciary. These lines cover salaries and activities of the respective organs. Premises funding supports the Court’s physical infrastructure. The Independent Oversight Mechanism, itself a product of state party frustration with the ICC, was established by the ASP in 2009 to inspect, evaluate, and investigate Court operations. The Office of Internal Audit, by contrast, provides internal quality control, reporting to senior management on the Court’s performance. The host state loan represents the repayment of Dutch outlays to construct the ICC’s premises.

Table 1. 2022 proposed and approved line-item budgets (in thousands of euros).

More fine-grained analysis of the budget leads many to fear that budget issues can hamper justice in specific ways. Despite critics’ focus on the OTP, it is comparatively well financed compared to other Court organs. The Independent Expert Review (Citation2020, p. 268), for example, pointed out that 32% of the Court’s 2020 budget request was for the OTP, whereas only 2.2% was dedicated to defense counsel. An earlier assessment shows that these proportions differed little from at least a decade earlier (Rogers, Citation2017). This also represents a much weaker investment in defense legal aid compared to previous international criminal tribunals. For example, defense was accorded about 10% the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia’s budget, and around seven percent at the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (Rogers, Citation2017). Furthermore, there has long been a concern that victim participation will be hampered with budget cuts (International Federation for Human Rights, Citation2012).

Debt politics

Like many intergovernmental organizations, the ICC struggles to get state parties to pay their dues, which calls into question state parties’ commitment toward justice. Budgets are of limited use if the money is not actually delivered. This further complicates the Court’s ability to complete its mission.

One can only surmise whether states are sending a political message by not paying their dues, but the likelihood is greater when rich countries are the culprits. As shows, as of 2019, it is predominantly the richest state parties that have shorted the ICC the most (see Harvard Dataverse for historical data). The amounts can be staggering, particularly when compared to the ICC’s overall budget. In 2019, for example, the top 10 debtors owed approximately €80 million, when the approved annual budget for the year was a little over €148 million.

Table 2. Top debtors in 2019 by absolute amount in arrears (amount in euros).

The Rome Statute contains provisions to sanction state parties for nonpayment. Specifically, countries in arrears can have their voting rights suspended. However, the treaty is written such that there are few consequences, particularly for rich countries. Article 112, paragraph 8 of the Statute dictates that the suspension of voting rights can be enforced when “the amount of [a State Party’s] arrears equals or exceeds the amount of the contributions due from it for the preceding two full years.” Practically, rich countries can withhold much more substantial sums without crossing this threshold. Provisions also permit the ASP to allow states to retain voting rights “if it is satisfied that the failure to pay is due to conditions beyond the control of the State Party.” Thus, sanctions are at the discretion of state parties.

The countries that have been sanctioned owe dramatically less, meaning that their failure to pay has much more limited effects on the Court’s ability to fulfill its mandate. With the notable exceptions of Argentina and Brazil, the countries meeting the Statute’s definition of “in arrears” are overwhelmingly poor. However, aside from Venezuela, only poor African and island states have had their voting rights suspended (see Harvard Dataverse for data on countries in arrears and suspensions). Thus, even by the treaty’s own criteria, larger economies like Argentina and Brazil are not sanctioned, despite their arrears having a much more dramatic effect on the Court’s ability to function effectively.

Gender spending at the ICC

To more fully understand the impact of funding politics on the practices of the Court, we turn to its work on gender equality, gender representation, and sexual and gender-based crimes to assess the extent to which budgetary constraints impact the gender-related commitments made by the ICC. Gender spending was selected for special focus as Bensouda named “[e]nhanc[ing] the integration of a gender perspective in all areas of [the OTP’s] work and continu[ing] to pay particular attention to sexual and gender-based crimes and crimes against children” a top policy priority in her first Strategic Plan for 2012–2015 (International Federation for Human Rights & Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice, Citation2021). The issue-specific rather than state-specific focus of gender work offers a different lens through which to view the exercise of financial power within international justice.

The Rome Statute is innovative in several ways with respect to gender justice. For the first time in an international/ized criminal court, it recognizes rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, and sexual violence as war crimes and crimes against humanity, and includes gender-based persecution as a crime against humanity. The procedures established for the Court are gender-sensitive (or at least should be). For instance, the Statute mandates the creation of a Victim and Witness Unit within the Registry, to include staff with expertise in trauma related to sexual violence, and requires the Court to take appropriate measures to protect the safety and physical and psychological well-being of victims and witnesses, particularly when charges involve SGBC. It also establishes the rights of victims to participate in cases and seek reparations from the Trust Fund for Victims (TFV). In terms of representation, the Statute requires fair representation of male and female judges, and that state parties account for the need to appoint judges with expertise on violence against women or children. The OTP is further required to appoint advisers with issue expertise, including SGBC. Potentially transformative in terms of gender justice, the prosecutor can initiate preliminary examinations proprio motu, which allows action on information brought by NGOs with the networks and expertise to gather evidence on SGBC.

The relatively progressive nature of the Rome Statute is, to a large extent, the result of concerted advocacy by women’s organizations in the run-up to the Rome conference, coordinated through the Women’s Caucus for Gender Justice.Footnote9 Although the Caucus had to make significant compromises on the ways that gender and forced pregnancy are defined in the Rome Statute, and was concerned that the Court could become a tool of the UNSC, it did envisage the Court as having significant potential to bring about gender justice (Women’s Caucus for Gender Justice, Citation1998, Citation2002).

To what extent has the promise of the Rome Statute been achieved, and what role has funding played? To explore this question, we first examine the way gender issues appear in the Court’s proposed budgets, then compare the Gender Report Cards issued by Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice (WIGJ, the NGO that the Women’s Caucus became after the Court came into being), and finally analyze the TFV and the Court’s practice of issuing reparations. Whereas WIJG is focused on gender above other Court priorities, our aim is to present trends over time on this specific issue, rather than to compare gender to other issue areas. Using WIJG data is appropriate here as it holds the categories of analysis and bases of judgment constant across time. These data are also the most robust available: WIJG is well-resourced (mostly through the Foreign Offices of Global North states such as Canada, Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom) and highly networked within the international criminal justice system. Future research drawing on this dataset should compare gender funding with other issues on the Court’s agenda.

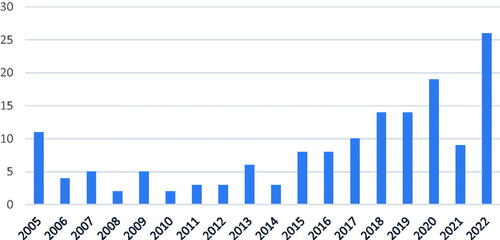

As the Court’s work has expanded, there has been an increase in the number of mentions of gender in the ICC’s Proposed Budgets, as indicates. Over time, however, the emphases have changed substantially, with more expansive goals gaining priority. In the Court’s early years, gender mentions in the budget focused on fair representation of gender across professional and staff roles, creating and resourcing a Gender and Children’s Unit, resources for gender-sensitivity training, and developing a policy on gender crimes and crimes against children. From 2009 onward, the proposed budgets requested resources for psychosocial resources to support victims and witnesses.

From 2013, the first full year under Prosecutor Bensouda, gender mentions began increasing as the OTP sought to finalize its policy on SGBC. From 2014 we see a much more goal-driven approach, with a commitment from the OTP to “enhance the integration of a gender perspective into all areas of our work and to continue to pay particular attention to sexual and gender-based crimes and crimes against children” (ICC Proposed Budget 2014); and from 2015, the OTP adopted a number of indicators to monitor its achievements against gender (and other) objectives. In 2017, first mention was made of resources for gender analysis in investigations and in 2018 there was an increased priority given in the budget to fair gender representation at the Court.

The focus on the Court’s internal practices alongside its prosecutorial practices continued in 2019, including the establishment of a Focal Point for Women, and performance indicators on gender awareness training and milestones in the gender/geographical action plan appeared in 2020 and 2021. In 2022, there was another step change aligned to new Prosecutor Karim Khan, who renewed the OTP’s focus on gender crimes and crimes against children (ICC Proposed Budget Citation2022, 63). The Gender and Children’s Unit was repositioned under a deputy prosecutor, to elevate it in the OTP hierarchy and ensure all OTP staff have access to specialized knowledge on gender-based crimes and crimes against children. Resources are also needed to appoint a new legal officer to provide legal and operational support to all teams on SGBC and crimes against children, and to provide specialized training for staff. The Registry also requested resources to establish a Focal Point for Gender Equality that would:

provide support to the principals in strengthening gender equality at the Court through five main functions: (i) advocating for women’s and gender issues; (ii) providing individual counseling; (iii) monitoring the Court’s progress in strengthening gender equality; (iv) raising awareness through training programmes, workshops and events; and (v) advising on gender parity targets. (ICC Proposed Budget, 2022, p. 86)

There is a tension between the increased mentions of gender in Proposed Budgets and the minimal budget increases sanctioned by the ASP. Indeed, a comparison of WIGJ’s first (2005) and most recent (2018) Gender Report Cards shows little improvement in appraisals of the Court’s work on gender. Given the focus on gender in both OTP policy and budgetary requests, the widespread rhetorical support for gender justice among state parties—for instance, via the United Kingdom’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative—and the relatively low level of controversy that work on gender equality and gender-based crimes generates among ICC funders—when compared, for instance, to work on situations impinging on powerful state interests such as Palestine and Afghanistan—this result is surprising.

The 2005 Report Card began by analyzing the profile of appointments, finding a generally good balance between men (53%) and women (47%) in professional and general posts, but a significantly higher number of men appointed to the List of Legal Counsel (84% vs. 16%). It found that, “Despite explicit mandates within the Rome Statute for legal expertise in relation to sexual and gender violence, and expertise in trauma also related to sexual and gender violence, not a single position has been recruited by the Court with this expertise as the primary criteria” (WIGJ, Citation2005). On the positive side, by the time the report was published, most of the staff at the ICC had completed at least a half-day of gender training.

In addition to staffing, the Report Card assesses the implementation of the Court’s gender mandates and finds that insufficient funding impacted the Court’s investigations and outreach. Poorly staffed investigation teams, a lack of key legal advisors, understaffing of field offices, and insufficient community outreach are all likely to have been detrimental to the reporting and investigation of SGBC. The Report Card also noted that the TFV was not yet operational as the ASP had not yet approved its regulations. The TFV, discussed in more detail below, is the innovative body that acts alongside the Court to support victims and administer reparations, including support for SGBC victims.

The 2005 Report Card made 16 recommendations, with six relating directly to recruitment, including “Greater emphasis on recruiting expertise (both legal and trauma) in relation to sexual and gender violence across all three organs of the Court.” Other substantive recommendations include increasing the Court’s budget to enable it to be driven by its mandate rather than resource constraints; increasing outreach activities; establishing a Gender Sub-Committee of States Parties; and for the ICC to commit to prosecuting SGBC whenever possible.

The 18-page 2005 Report Card was dwarfed by the latest, 172-page Report Card published by WIGJ in 2018. This Report analyzed the gender implications of Amendments to the Rome Statute and state withdrawals, preliminary examinations, investigations and active cases, and procedures and jurisprudential developments at the Court. The report also included an evaluation of the budget, noting:

The proposed budget of the Court does not appear to explicitly take gender mainstreaming or gender responsiveness into account. The goal of gender responsive budgeting is to review the impact of budget allocations from a gendered perspective, ensure a gender equitable distribution of resources, and contribute to equal opportunity for all. (WIGJ, Citation2018, p. 20)

The Report also noted that the repeated references to conservative budgeting in the OTP’s budget request suggests that there may not be sufficient resources to build effective SGBC cases. The Report criticized the resource-driven approach that the organs of the Court take to ASP budget requests, arguing instead that state parties should fund based on need, and perhaps even establish a specific budget allocation to investigate SGBC. This approach is impossible in the face of the ZNG policy. Finally, the 2018 Report Card noted that neither the Registry budget nor the TFV Secretariat budget appear to have been developed with gender in mind; nor does either include gender analysis of the distribution of resources.

Overall, the recommendations of the 2018 Report were comparatively less focused on gender balance of staff and counsel at the Court than its 2005 predecessor. Substantive recommendations around budget include that the CBF should request that future budgets from organs of the Court have gender-specific allocations for outreach, victim participation, witness engagement, investigations, recruitment, and training. Moreover, the Court should adopt a gender mainstreaming approach to all budget and resource allocation issues. Linked to resource allocation, the 2018 Report Card suggested that the Court request urgent funds to appoint a full-time gender advisor within all organs of the Court and a gender legal advisor within the Trial Division of the Judiciary. Further recommendations suggested appointing a gender and legal advisor to the OTP’s Preliminary Examinations Team and allocating sufficient resources to enable a gender analysis and thorough investigation of SGBC in each situation.

After 16 years in operation when the 2018 Report Card was published, it is incredible that a Court with a commitment to gender issues from the outset is receiving these recommendations. More work is needed on whether the responsibility for these failures lies predominantly with Court staff or the decisions by the ASP, although, as discussed earlier and illustrated by the response to Ukraine, state parties (and indeed other states and nonstate actors) are free to increase funding and support for the Court at any time. What has become clear through the Independent Expert Review (Citation2020) is that the Court has failed to implement gender mainstreaming in all organs; failed to achieve gender equality within its structures; and failed to prevent bullying and harassment, including sexual harassment, within its practices. And, despite attempting to prosecute SGBC in many of its cases, the OTP has only achieved two successful prosecutions for such offenses in 20 years (Ntaganda and Ongwen, the latter still subject to appeal),Footnote10 with experts suggesting that its lack of resources to train and increase the capacity of critical actors (investigators, medical personnel, police, etc.) is at least partly to blame (Seelinger, Citation2016).

The Trust Fund for Victims and its reparations practices also are important in assessing the ICC’s delivery on gender justice. Women’s rights and gender advocates have long held that retributive justice is not gender justice: Gender justice requires rights of participation at trials and rights to reparation for victims, not just gender mainstreaming through prosecutorial practice or gender equality in staff roles. To the extent that the Court is a tool of neocolonial powers used to discipline less powerful states, we would expect to see a relatively low level of funding for reparative measures, as the principal role of a highly politicized court would be retributive.

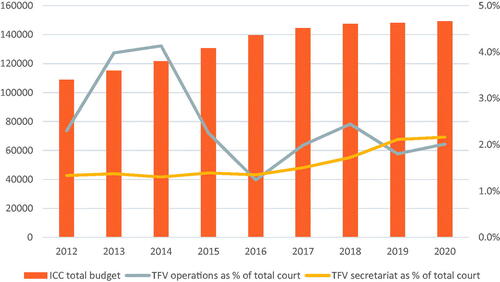

The TFV has a two-part mandate: “(i) to implement Court-Ordered reparations and (ii) to provide physical, psychological, and material support to victims and their families.” To carry out its mandate, the TFV needs significant funding. illustrates current TFV Director Pieter de Baan’s view that the TFV is responsible for “50 percent of the court’s impact but only 2 percent of its budget” (Anderson & van den Berg, Citation2020). Two things are noteworthy: Relatively low amounts of spending are directed toward reparations and victim support (generally around two percent of the total ICC budget) and there is a relatively high level of spending on the Secretariat relative to operational spending. As Redress (Citation2019, p. 34) observed, “Each year the Trust Fund has only a fraction of what is needs to fulfill its mandates.”

The problem is not only the level of funding but also its predictability. Redress (Citation2019, pp. 12–13) noted,

[T]he ability of the Trust Fund to successfully fulfill its mandates depends on its ability to attract sustained funding. … The Fund must … diversify its funding sources as the current dependence on voluntary donations is unsustainable… The Trust Fund’s efforts to raise funds must be complemented by more focused attention by States to the tracing, freezing and seizing of the assets of convicted persons for the benefit of reparations.

Given that voluntary donations from state parties account for the vast majority of the TFV budget (€2.8 m in 2020, compared to €14,500 from private individuals and institutions), responsibility for the underfunding of the TFV rests with wealthy state parties. Again, this supports the claim that the Court is a politicized tool of powerful states, or at least that the state parties that fund the Court are less committed to reparative than to retributive justice.

This said, the TFV is widely thought to have been too slow to undertake the assistance and support that it can afford, suggesting institutional problems alongside recalcitrance among donors. According to the Independent Expert Review (Citation2020, p. 292), the fact that “the TFV has not been successful in attracting more donations is partly due to … how the TFV and its Secretariat have been construed, governance and management issues within the Secretariat, ineffective oversight, and the absence of a fundraising strategy.” The review further highlighted a 2019 finding of the CBF, which “noted with concern the constant under-implementation rate” of the TFV on budget. It further noted that the implementation of reparations to victims required a strengthened organizational structure (Independent Expert Review, Citation2020, p. 308).

The second part of the TFV’s mandate is to implement Court-ordered reparations. The 2019 Redress report noted,

[P]roviding meaningful reparations in a timely manner has proven to be a challenge for the Court. To date, only a fraction of the victims that have either applied for or are eligible to receive reparations have actually seen any tangible benefits, despite reparations awards of millions of euros or US dollars and draft implementation plans of hundreds of pages. (Redress, Citation2019, p. 18)

The Reparations Order in the case of Prosecutor v. Bosco Ntaganda promises a step change in reparations practice at the ICC, but there is much work for the TFV to do—not least an historic fundraising effort—to transform the order into real benefits for victims. Nonetheless, the language of the order is a significant victory for campaigners for gender-sensitive reparations. Whether state parties and other interested actors fund the TFV sufficiently to fulfill its mandate in this case remains to be seen, but our analysis suggests that, despite rhetorical support for victims, lack of funding will lead to a paucity of genuine justice.

Conclusion

ICC state parties’ response to Ukraine seems to support the charge that the Court is a tool of powerful states. In this new environment, providing more financial support to the ICC allows states to demonstrate a commitment to global accountability norms while also sticking it to a rival country, without disrupting the narrative of Western progress on which international criminal justice rests (Simpson, Citation2007).

This new hyperactivity from state parties does not negate widespread perceptions of the ICC as an expensive, slow, and unbalanced court in which some donors have disproportionate influence. From the beginning, it has operated in the uncomfortable reality that, although its legitimacy is built on being perceived as apolitical, the Court is fundamentally reliant on states (Ba, Citation2020; Bosco, Citation2014). Prosecutor Khan seems acutely aware of the reputational risks of the influx of resources brought by the Russian invasion. In public comments, Khan asserted, “We will not earmark for Ukraine. I can’t accept that” (Goodman, Citation2022). The Court seems to be at the whim of a group of state parties that attempt to manipulate its budget to achieve foreign policy goals rather than to fund it on a needs-basis to achieve its mandate.

Looking to broader trends, some of the most innovative aspects of the Court are relatively costly: Investigating and prosecuting SGBC requires high levels of resources, as does adequately supporting and repairing victims. The Court has not had a sufficient budget to achieve its aims, particularly around gender justice, but donors are not entirely at fault, and many have donated to ICC work on SGBC. In fact, this is a fruitful area for further research.

There is much more to say about the need for the Court to convince state parties that it provides good value for money. There is also research that needs to be done on the extent to which low or insecure funding has led to the failures in the Court system that do not seem to be directly tied to money—for instance bullying and harassment—and the TFV’s chronically slow processes. But at least in terms of the Court’s gender mandates, the commitment of two consecutive prosecutors to gender justice and the innovations in the Ntaganda reparations order suggest that some level of success is attainable, if state parties are willing to fund it. We can but hope that the renewed interest in justice that the invasion of Ukraine has awakened in donors leads to a better, consistently funded, and therefore more independent Court, which is increasingly able to prosecute cases and offer reparation to victims across the globe, no matter whose interests are at stake.

Acknowledgments

This publication is based on activities and or/research supported by the GCRF Gender, Justice and Security Hub. The authors thank Cameron Russell and Claire Wilmot for valuable research assistance on this article. Thank you to Michael Broache, Courtney Hillebrecht, and anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eric Wiebelhaus-Brahm

Eric Wiebelhaus-Brahm, PhD in political science, is associate professor in the School of Public Affairs at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. His work focuses on human rights, transitional justice, and peace and conflict studies. E-mail: [email protected]; Twitter: @wiebelhausbrahm.

Kirsten Ainley

Kirsten Ainley is Associate Professor of International Relations and the Co-Principal Investigator of the UKRI GCRF Gender, Justice and Security Hub. Her research focuses on international policy and practice in military, legal and development-focused interventions, and the impacts of these interventions. E-mail: [email protected]; Twitter: @kirstenainley.

Notes

1 Data are available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/JE8SKW.

2 The budgeting process within the ICC is still, to a large extent, a black box. Given that the overall budget is relatively fixed, there is intra-institutional competition for resources; for instance, a greater demand from the Registry will need to be compensated for elsewhere. The principals of the Court (its president, prosecutor, and registrar) claim in the “Proposed Programme Budget for 2023 of the International Criminal Court: to work together to streamline the Court’s budget, although this process needs further research.

3 The Coalition for the ICC is particularly active around budget issues, advocating that the Court deliver rigorous, disciplined budgets and that state parties fund the ICC sufficiently to deliver meaningful justice.

4 The initiative was introduced by Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Poland, Spain, the United Kingdom and Venezuela.

5 Official Records, Fifteenth session, 2016 (ICC-ASP/15/20), vol. I, part III, ICC-ASP/15/Res.1, Section L, para. 1.

6 Official Records, Fifteenth session, 2016 (ICC-ASP/15/20), vol. I, part III, ICC-ASP/15/Res.1, Section L, para. 2.

7 Official Records, Eighteenth session, 2019 (ICC-ASP/18/20), vol. I, part III, ICC-ASP/18/Res.1, Section K, para. 6.

8 Proposed Programme Budget for 2018 of the International Criminal Court Budget, Annex X, para. 5. Accessed at https://asp.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/asp_docs/ASP16/ICC-ASP-16-10-ENG.pdf.

9 At the same time, it must be noted that the statute’s definition of gender is inherently conservative: “the term ‘gender’ refers to the two sexes, male and female, within the context of society,” Article 7(3).

References

- Abebe, D. (2014, December 12). I.C.C.’s Dismal record comes at too high a price. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2014/12/11/do-we-need-the-international-criminal-court/iccs-dismal-record-comes-at-too-high-a-price

- Ainley, K. (2011). The International Criminal Court on trial. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 24(3), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2011.558051

- Amnesty International. (2021, July 26). The cost of hibernated investigations. Amnesty Human Rights in International Justice (HRIJ). https://hrij.amnesty.nl/the-cost-of-hibernated-icc-investigations-blog-series/

- Anderson, J. (2021, October 21). Afghanistan: A war of positions at the ICC. JusticeInfo.Net. https://www.justiceinfo.net/en/83498-afghanistan-war-of-position-icc.html

- Anderson, J., van den Berg, S. (2020, December 9). ICC Trust Fund: The black hole. JusticeInfo.Net. https://www.justiceinfo.net/en/46199-icc-trust-fund-black-hole.html

- Ba, O. (2020). States of justice: The politics of the International Criminal Court. Cambridge University Press.

- Bosco, D. (2014). Rough Justice: The International Criminal Court in a world of power politics. Oxford University Press.

- Cannock, M., O’Donohue, J. (2018, May 2). Don’t ask and you won’t receive – Will the ICC request the resources it needs in 2019? Amnesty HRIJ. https://hrij.amnesty.nl/icc-zero-growth-dont-ask-and-you-wont-receive/

- Clarke, K. M. (2019). Affective justice: The International Criminal Court and the Pan-Africanist pushback. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478090304

- Coalition for the International Criminal Court. (2016, November 21). Victims to lose out with states’ double-standard on ICC budget—Coalition for the International Criminal Court. https://www.coalitionfortheicc.org/news/20161121/victims-lose-out-states-doublestandard-icc-budget

- Corey-Boulet, R. (2011, September 28). Concern over ICC funding. Inter Press Service. https://www.ipsnews.net/2011/09/concern-over-icc-funding/

- Evenson, E. M., O’Donohue, J. (2015, November 3). Still falling short—The ICC’s capacity crisis. OpenDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/openglobalrights-openpage/still-falling-short-icc-s-capacity-crisis/

- Evenson, E. M., O’Donohue, J. (2016, November 23). States shouldn’t use ICC budget to interfere with its work. OpenDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/openglobalrights-openpage/states-shouldn-t-use-icc-budget-to-interfere-w/

- Ford, S. (2017). What investigative resources does the International Criminal Court Need to succeed: A gravity-based approach. Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 16(1).

- Goodman, R. (2022, May 27). How best to fund the International Criminal Court. Just Security. https://www.justsecurity.org/81676/how-best-to-fund-the-international-criminal-court/

- Guilfoyle, D. (2019). Lacking conviction: Is the International Criminal court broken? An organisational failure analysis. Melbourne Journal of International Law, 20(2), 401–452. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20210112042064

- Hillebrecht, C. (2021). Saving the international justice regime. Cambridge University Press.

- Independent Expert Review. (2020). Final report of the independent expert review of the international criminal court and the rome statute system. International Criminal Court. https://asp.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/asp_docs/ASP19/IER-Final-Report-ENG.pdf

- International Federation for Human Rights & Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice. (2021). Accountability for sexual and gender-based crimes at the ICC: An analysis of Prosecutor Bensouda’s legacy (No. 772a). https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/cpiproc772ang-1.pdf

- International Federation for Human Rights. (2012). Cutting the Weakest Link: Budget Discussions and their Impact on Victims Rights to Participate in the Proceedings [FIDH Position Paper]. https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/cpiasp598ang2012.pdf

- Kendall, S. (2015). Commodifying global justice: Economies of accountability at the International Criminal Court. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 13(1), 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqu079

- Kersten, M. (2016). Justice in conflict: The International Criminal Court’s impact on conflict, peace, and justice. Oxford University Press.

- Kimenyi, M. S. (2013, October 17). Can the International Criminal Court play fair in Africa? Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2013/10/17/can-the-international-criminal-court-play-fair-in-africa/

- Mamdani, M. (2008, September 10). The new humanitarian order. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/new-humanitarian-order/

- Mills, K. (2012). Bashir is dividing us: Africa and the International Criminal Court. Human Rights Quarterly, 34(2), 404–447. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2012.0030

- Moffett, L., & Sandoval, C. (2021). Tilting at windmills: Reparations and the International Criminal Court. Leiden Journal of International Law, 34(3), 749–769. https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215652100025X

- Murithi, T. (2012). Africa’s relations with the ICC: A need for reorientation? In A fractious relationship: Africa and the International Criminal Court (pp. 4–9). Heinrich Böll Stiftung. https://ke.boell.org/sites/default/files/perspectives_01.2012_web1.pdf

- New African. (2012, March 1). Who pays for the ICC? New African Magazine. https://newafricanmagazine.com/3049/

- O’Donohue, J. (2020, April 14). ICC Prosecutor Symposium: Wanted–International prosecutor to deliver justice successfully across multiple complex situations with inadequate resources. Opinio Juris. http://opiniojuris.org/2020/04/14/icc-prosecutor-symposium-wanted-international-prosecutor-to-deliver-justice-successfully-across-multiple-complex-situations-with-inadequate-resources/

- Office of the Prosecutor. (2022, May 17). ICC Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan QC announces deployment of forensics and investigative team to Ukraine, welcomes strong cooperation with the government of the Netherlands. International Criminal Court. http://www.icc-cpi.int/news/icc-prosecutor-karim-aa-khan-qc-announces-deployment-forensics-and-investigative-team-ukraine

- Redress. (2019). No time to wait: Realising the right to reparations for victims before the International Criminal Court. Redress. https://redress.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/20190221-Reparations-Report-English.pdf

- Rogers, R. J. (2017). Assessment of the ICC’s Legal Aid System. Global Diligence LLP. https://www.icc-cpi.int/itemsdocuments/legalaidconsultations-las-rep-eng.pdf

- Schabas, W. A. (2020). An Introduction to the International Criminal Court 6th Edition. Cambridge University Press.

- Seelinger, K. T. (2016). Response to question: “How can the ICC OTP secure better cooperation from first responders and those working on the ground with victims and survivors to assist in the investigation and prosecution of sexual and gender-based crimes?” The International Criminal Court Forum. https://iccforum.com/sgbv

- Simpson, G. J. (2007). Law, war and crime: War crimes. Trials and the Reinvention of International Law. John Wiley & Sons.

- Waddell, N., & Clark, P. (Eds.). (2008). Courting conflict? Justice, peace and the ICC in Africa. Royal African Society.

- Women’s Caucus for Gender Justice. (1998, July 17). Propio Motu Power of Prosecutor, Women’s Caucus. http://iccwomen.org/wigjdraft1/Archives/oldWCGJ/icc/iccpc/rome/propiomotu.html

- Women’s Caucus for Gender Justice. (2002, July 1). Everything you wanted to know about the International Criminal Court but didn’t have time to ask. http://iccwomen.org/wigjdraft1/Archives/oldWCGJ/icc/iccpc/072002/july1event.html

- Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice. (2005). Gender report cards on the International Criminal Court 2005. Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice. https://4genderjustice.org/ftp-files/publications/Gender_Report_Card_2005.pdf

- Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice. (2018). Gender report cards on the International Criminal Court 2018. Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice. https://4genderjustice.org/ftp-files/publications/Gender-Report_design-full-WEB.pdf