Abstract

Dealing with the legacy of the past has become a popular demand in postconflict and posttransition countries. However, the pursuit of truth can be a divisive issue that threatens rather than promotes understanding, particularly in divided societies. Would a minimalist truth satisfy the victim-centered right to know, without disturbing delicate balances in society? This article theorizes how different designs of truth commissions impact social outcomes, contrasting two ideal types: thin truth, which gives solely individual factual knowledge, and thick truth, which produces a public report and searches for a pattern of events. We look at the case of Spain, which long used a “policy of forgetting” to deal with the crimes of the Civil War and Franco dictatorship and where the politics of memory has become a partisan issue, and embed experimental treatments into a representative survey conducted in 2021. Our findings show that restricting truth brings no advantages, as the different designs have no significant impact on the highly polarized reactions. The research has implications for policy by showing how different truth commission formats (fail to) impact on reconciliation.

In 2000, 64 years after the killing of his grandfather by Francisco Franco’s troops, Emilio Silva Barrera was finally able to discover where the remains were buried. The information came from a private interview Silva Barrera had carried out for a book on his family’s history. From this incident, Silva Barrera—along with Palma Granados, Jorge López, and Santiago Macías—founded the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH), dedicated to finding the remains of Republicans who had been disappeared by Franco forces.

This process of private individuals seeking the truth of what happened to their relatives is typical in Spain. More than 40 years after Franco’s death, there has still not been a comprehensive reckoning with the events of the Civil War (1936–1939) and the crimes of the Franco regime (1939–1975). For many years, events were deliberately ignored, under a “pact of forgetting” established during the transition to democracy. Recent attempts to examine the past, through a Historical Memory Law in 2007 and the Democratic Memory Law of 2022, have turned into partisan issues.

This study examines the impact of the pursuit of truth in polarized societies. Mechanisms to deal with the legacy of the past are increasingly used throughout the world, following the increasing focus on victim-centered approaches (Dyrstad & Binningsbø Citation2019), often with the hope that acknowledgment of the past will somehow contribute to reconciliation. However, the empirical evidence supporting such claims is still scarce. Indeed, in polarized societies, examples suggest the opposite is true, with truth becoming a divisive issue. In this context, some countries attempt to restrict the access to truth. As well as the Spanish example, in Northern Ireland, there has never been a truth commission, and a law is being passed at the time of writing that would mean deaths during the conflict are investigated by an independent commission resulting only in a private report for the families. Does this satisfy the victims’ right to know without upsetting delicate balances in a postconflict society? What consequences might such a strategy have?

Variations in truth commission design and format can lead to different outcomes (Kochanski, Citation2020; Stahn, Citation2005; Zvobgo, Citation2019). In this article, we consider how the truth commission can vary in the content of the truth (whether it is about forensic facts or whether it delves into more subjective or complex issues, such as responsibility for the overall conflict) and its outreach (whether it is communicated to the victims only or to the whole society). We focus on two ideal types of truth commission design: thin truth, which gives factual information to only those individuals most affected, contrasted with thick truth, which generates a public report that examines a pattern of events. We theorize that thin truth will help victims’ individual reconciliation with the past. Thick truth, which would be the normatively encouraged form, impacts social reconciliation, but in a polarized society it can have negative effects because it exposes structural or long-standing discrimination (Samii Citation2013). Such a challenge is most dangerous where the cleavage in society—whether partisan, ideological, ethnic, or other—overlaps previous perpetrator/victim identities.

Answering this question with observed data is problematic, as the design of the truth commission cannot be separated from the circumstances of the case. We therefore turn to an experiment embedded in an original representative survey in order to test how the public reacts to different truth commission designs. We conducted the survey in Spain, which for decades did not address the crimes of the Civil War and the Franco era, but which recently has proposed a process for the pursuit of truth. The survey ran October 6–8, 2021, with 1,050 respondents, and this time frame allowed us to exploit a moment when there had been a legislative commitment to the pursuit of truth by the Spanish government, but the form that would be implemented had not yet been determined. We could therefore use a research design with an experimental vignette that presented thin and thick truth.

The results of the experiment show that those most opposed to a truth process (the right-wing respondents) are no more likely to see any positive outcomes from thin truth than from thick truth. It is with some relief that we conclude that compromising on normative aims does not bring empirical benefits, at least as shown in this research. However, the results do reinforce that the pursuit of truth is a highly polarizing issue, with the left wing mostly positive and the right wing negative across all measures. Furthermore, even those on the left view thick truth as negative for social reconciliation, which is consistent with recent research that shows that a backlash effect to transitional justice can spill over into the wider society (Villamil & Balcells, Citation2021). In short, truth commissions are judged through the lens of the cleavage in polarized societies, but compromising on the design of the truth commission does not alleviate this problem. This finding has policy implications for different designs for the pursuit of truth and truth commissions by showing that implementing a minimalist pursuit of truth with the aim of avoiding controversy and polarization does not bring any advantages and therefore is not justified.

The article proceeds as follows: The first sections review the literature on truth commissions and develop our theoretical framework; the next section explains our case selection and gives some background to transitional justice in Spain; next, we describe our experiment; and in the subsequent sections, we give the findings and the discussion of the results, followed by the conclusion.

Literature review

Effects of the pursuit of truth

Given that transitional justice is a relatively recent area of study (Teitel, Citation2003), there is still a great deal that we do not know about whether and how different transitional justice mechanisms work (van der Merwe et al., Citation2009). This article focuses on the pursuit of truth broadly, with the aim to inform truth commissions, taken as temporary, officially-mandated bodies that seek to gather information about past events (Dancy et al., Citation2010; Hayner, Citation2011). Originally seen as a second-best solution when trials were politically impossible (Chapman & Ball, Citation2001; Mamdani, Citation2005), truth commissions are now seen as a valid way to fulfill the “inalienable right to know the truth about past events and about the circumstances and reasons which led, through systematic, gross violations of human rights, to the perpetration of heinous crimes” (Orentlicher, Citation2005 Principle 1, Annex II) and a way to balance the delicate compromise between examining the past while impacting the future (Gonzalez-Enriquez et al., Citation2001; Pion-Berlin, Citation1994). Truth commissions are now often used in conjunction with trials, although in different combinations.Footnote1

With the increasing use of truth commissions came increased examination of the impact of the pursuit of truth.Footnote2 Some supporters endorse truth commissions for normative reasons, for example, the pursuit of truth fulfills moral obligations to victims (Minow, Citation1998) and brings satisfaction, which is a form of reparation for victims (Orentlicher, Citation2005; van Boven, Citation2005). Others focus on empirical outcomes, particularly reconciliation. We define reconciliation as “changing the motivations, goals, beliefs, attitudes, and emotions of the great majority of the society members regarding the conflict, the nature of the relationship between the parties, and the parties themselves” (Bar-Tal & Bennick, Citation2004, p. 12). Thus, reconciliation can be at the individual level or affect society. Reconciliation can also range from minimal, such as mere coexistence with former enemies (Crocker, Citation2000), through to the comprehensive reconstruction of social bonds (Crocker, Citation2000) and a shared comprehensive vision of the past, reciprocal acknowledgment of past suffering, and mutual recognition and acceptance (Bar-Tal & Bennick, Citation2004; Skaar, Citation2012). Advocates assert that the pursuit of truth can aid in individual healing and societal reconciliation (Minow, Citation1998).

However, skeptics claim that truth processes can do more harm than good. The pursuit of truth can highlight social divisions and make reconciliation more difficult to achieve (Snyder & Vinjamuri, Citation2003). Truth can hinder reconciliation because “the evil is so ghastly that it is unlikely to be mitigated by further understanding of the details” (Daly, Citation2008, p. 37). In particular, truth can be a problematic concept in divided societies. In many societies, there can be multiple perspectives on the truth, and “the truths are not only multivarious and subjective but also mutually exclusive” (Daly, Citation2008, p. 26). Although skeptical about the benefits of truth, many researchers conclude not that the pursuit of truth should be avoided, as refusing to engage with the past is considered to be worse, but that the alternative is to do truth better (Daly, Citation2008; Fletcher & Weinstein, Citation2002; Hayner, Citation2011).

Thus, there is a need for further empirical evidence of the impact of truth on reconciliation. In the last few decades, there has been increased emphasis on the need to carefully assess the effects of transitional justice (Brahm, Citation2007; Dancy et al., Citation2010; Dancy & Thoms, Citation2022; Gibson, Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2006; Mendeloff, Citation2004, Citation2009; Olsen et al., Citation2010b; Olsen et al., Citation2010c; Sikkink & Walling, Citation2007; Wiebelhaus-Brahm, Citation2010). Despite the linkage of truth and reconciliation in popular views and among policy activists (Daly, Citation2008; Kochanski, Citation2020), the findings are mixed, particularly with respect to polarized societies (Bassiouni Citation1996; Sarkin Citation1999). For example, Gibson (Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2006) found that truth leads to reconciliation, however, only among those already disposed to accept the findings of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission report. Most research on truth and reconciliation in divided societies is pessimistic (Daly, Citation2008; Daly & Sarkin, Citation2007; Fletcher & Weinstein, Citation2002). Problems include a lack of knowledge of the crimes, interviewees refusing to accept the evidence of events even when presented with it, and the differential interpretation of events by opposing groups (Illić, 2004, cited in Daly Citation2008, pp. 37–38). Communities draw on history or a metanarrative to reframe their thinking around atrocities and sometimes recast them as morally acceptable and even a source of pride (Fletcher & Weinstein, Citation2002).

In this context, advice is needed on how best to design the pursuit of truth in order to bring about reconciliation. Such an endeavor matters because information gained can be used to support normative arguments about truth commission design.

Theoretical framework

Our aim is to explore how different forms of truth commissions can lead to different impacts on reconciliation. We first conceptualize how the truth commission can vary in the content of the truth, which is considered, on one hand, as forensic facts and, on the other, as a broad pattern of events that exposes more subjective or complex issues, such as responsibility for the overall conflict. The second variation is on the outreach, which, on the one hand, is communicated only to the individual victim or descendants but, on the other, is an extensive remit to reach the whole society ().

Table 1. Different aspects of truth commission design.

A truth commission that reports forensic facts limits itself to a truth that is “factual, verifiable and can be documented and proved,” called “microscopic truth” by the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC South Africa, Citation1998, p. 113). Such a commission investigates each incident, but considers it as isolated from other incidents. The commission identifies events as atomized happenings that are located in a specific time and space, but are not part of any temporal or spatial narrative. At the other end of the scale we have a truth commission that “investigates a pattern of events that took place over a period of time” (Hayner, Citation2011, pp. 11–12). This truth commission goes beyond the individual events to capture a wider dynamic. Single events are understood not only as individual incidents but also as part of a broader arc that can help answer why these events happened and how such a situation came about. It attempts to understand the context, the justifications, and the motivations for the sweep of events. This truth commission casts light on the systemic causes of violence embedded in attitudes and relations within the society.

As well as content, truth commissions can also be distinguished by different approaches to outreach. On one hand, information can be shared with only those directly concerned, such as close family. The truth is a private matter, and once the information is delivered, the matter is considered closed. At the other end of the scale, the truth commission “engage[s] directly and broadly with the affected population, gathering information on their experiences … concluding with a final report” (Hayner, Citation2011, pp. 11–12). This truth commission encompasses a broad approach to the output, disseminating the information as widely as possible in order not only to answer questions about what happened in the past but also to start a dialogue about how to prevent such events in the future. This conversation involves all of society, as these questions involve changes in structures and systems.

In the analysis, we focus on two ideal types of truth commission design: thin truth, which is limited in both its content and outreach and gives factual information only to those individuals most affected, contrasted with thick truth, which is expansive in both its content and outreach and generates a public report that examines a pattern of events.Footnote3 Most commentators on truth commissions endorse thick truth, and some observers would say it is normatively imperative (Hayner, Citation2011). However, it is important to know the empirical consequences of these choices, in particular if a truth commission has a limited remit for politically expedient reasons, how damaging is thin truth? We therefore turn to the impact of thin and thick truth on individual and social reconciliation.

We theorize that even thin truth can have positive effects on individual reconciliation by impacting processes important in dealing with the past, such as grieving and closure. First, the content of the truth has effects. The individuals affected receive the objective and forensic facts about the incident, which brings closure to victims (Herman, Citation2022; but see Mendeloff, Citation2009). For example, for 64% of families of disappeared relatives surveyed in Nepal, their top priority was to know the fate of their loved one, to be able to grieve and let go (Robins, Citation2011).Footnote4 Second, the outreach, although only to the immediate family, also has an impact. The event is recognized and reified, as the production of information about the event implies that the incident needs to be identified and investigated, and the victim should be informed, requiring resources and time. Therefore, the information about the event and recognition of it as worthy of investigation can help the individual move on.

Transitional justice is moving toward a victim-centered focus, and thin truth can provide a minimum level of victim satisfaction. Therefore, thin truth can have positive effects for individual reconciliation. However, thin truth cannot affect societal reconciliation, as it does not engage with a larger story about the events that happened; nor does it open a conversation with society about how to prevent such a history repeating itself. Although thin truth may have spillover effects at the content level, because victims can seek to spread and connect the information that is revealed to them, this is not endorsed at an official level and so can be countered. It is difficult for these spillover effects to lead to societal reconciliation without formal and deliberate social outreach. Thin truth is presented as something private, that should be hidden away.

Thick truth goes beyond thin truth in both content and outreach. The content of thick truth is to search for a pattern of events. Whereas with thin truth the factual and forensic information about the event puts the focus on the victim, with thick truth the exposition of a pattern of events puts the focus on the perpetrators and the system that enabled them. The information is therefore about the structural features of society.

The second feature of thick truth is its outreach, which puts information about the events in the public domain. With the production of a report, the public knows the details of the events that took place. This has effects because people care about procedural justice (Tyler, Citation2003) and prefer transitional justice that punishes perpetrators and brings relief to victims (Tellez, Citation2019b). A report opens a public debate and so is in direct dialogue with society (the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission referred to “social” and “dialogical” truth). This debate requires facing the past and opens the possibility of reforming the future, ensuring that such events can never happen again (e.g., the reports Nunca Más [Never Again] and [¡Basta Ya!] (Enough Already!) from the Argentine National Commission on the Disappeared and the Colombian National Center for Historical Memory, respectively).

Third, the satisfaction of this sense of justice also leads to a feeling of living in a society in which justice is valued and prioritized. These are core democratic values, and so, in a society that has transitioned to democracy, this process underlines the change of values with the new regime (Olsen et al., Citation2010a). When the country’s values align with one’s personal values, this generates social and political engagement (Tyler & Jackson, Citation2014). Therefore, through a sense that justice has been fulfilled and a feeling that democratic values have been endorsed, thick truth has an effect on societal changes. Through opening a public debate, the report requires groups in society to face their previous roles and power relations, requiring a change in group dynamics. Thick truth therefore also has an effect on how groups in society live together.

These observations lead us to a number of expectations that the different output formats will affect perceptions of reconciliation. We expect thin truth to be linked to positive reconciliation for individual victims, but not to be linked to any societal reconciliation. We expect thick truth, by contrast, to be linked to both positive reconciliation for individuals and also to societal reconciliation.

We now turn to how this link between different levels of truth and societal reconciliation can be affected in a polarized society, whether the cleavage is partisan, ideological, ethnic, or other. Social identity is an important determinant of reconciliation in divided societies (Gibson & Gouws, Citation1999; Samii, Citation2013). There is increasing recognition that mechanisms for pursuing truth are deeply embedded in the political circumstances in which they take place (Daly, Citation2008; Daly & Sarkin, Citation2007; Gillooly et al., Citation2024). This political aspect of processes affects not only whether the pursuit of truth takes place (Escudero, Citation2014) but also what effects such practices can have. A focus on simply thin truth can be seen as advantageous in polarized societies, as the facts satisfy the victim-centered focus and the victims’ right to know, understood in the narrowest meaning of the phrase, yet the information revealed need not threaten any delicate balances in society. The facts are personalized and limited to the specific case involved. Importantly, there is no public campaign awareness of the content of the information given to victims, and any spillover by victims attempting to link the content they have received can be denied or relegated to the private realm. Thin truth does not directly challenge the structural causes of the violence. It satisfies victims’ rights, but takes this focus as a way to evade going deeper into patterns of action, responsibilities, and indeed an understanding of how these events could have taken place and the possibilities of them happening again.

By contrast, thick truth, with its creation of a “macro” story about the conflict, is problematic in polarized societies. We theorize that thick truth, which would be the normatively encouraged form, exposes structural or long-standing discrimination and aims to recalibrate and challenge the distribution of power in a society. Such confrontation is most dangerous where the cleavage in society overlaps previous perpetrator/victim identities. By identifying a pattern of events, a unifying narrative emerges that often casts one party as the principal perpetrator. This focus on the perpetrators—and, in particular, the casting of one group in society as the principal source of atrocities—increases the sense of in-group/out-group dynamics (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). Those cast as the perpetrators will not endorse a truth that incriminates them. For example, in Guatemala, the Truth Commission found that conflict was extremely one-sided: State forces and related paramilitary groups were responsible for 93% of the human rights violations documented (Commission for Historical Clarification, Citationn.d., para. 82). Yet, this revision was not accepted by the political and economic elites or by the military, and this failure has been a core driver in the lack of reconciliation in Guatemala (Brett, Citation2022). By contrast, those who feel that a process is telling “their” truth will be more positive about the democratic effects of the procedure (Daly, Citation2008).

These observations lead us to expectations for how different groups in society evaluate the impacts of thin and thick truth. Because thin truth does not challenge the structures of society or open a public debate about the causes of the events, thin truth does not feed into polarization, and so we do not expect strong differences by which group in society is evaluating the option. Thick truth, by contrast, is more problematic in a polarized society, as it is seen as disturbing social hierarchies. Moreover, these reactions are further determined by which group in society is evaluating the option, with the group cast as the perpetrators more negative about thick truth compared to thin truth. Our expectation is that these people will perceive impacts on reconciliation as less positive than those who are feel that the truth commission tells “their” truth across all measures.

Case selection and background

Each transitional context is particular to itself, but countries transitioning out of periods of oppression and gross human rights violations face certain common problems, one of which is addressing the past (Hayner, Citation2011). There is acknowledgment that addressing the past is a delicate process in which some groups can see themselves as winners while others see themselves as losers. Politicians and leaders can exploit findings for their own ends. For this reason, the case of Spain is interesting from both an academic and policy perspective. The transition to democracy was based on a “pact of forgetting.” This pact allowed members of the Francoist regime to remain in positions of power among the right-wing political party, a legacy that has remained through current times, with Spain strongly polarized along the left–right axis (Orriols & León, Citation2020; Torcal & Comellas, Citation2022). The pact also meant that patterns of victimization were not addressed, which has also contributed to this polarization (Balcells, Citation2012). Spain is therefore a good case of a polarized society and specifically one in which the divide in society overlaps perceptions of perpetrator/victim.

Attitudes toward transitional justice are also divided. A survey in 2008 showed that support for a truth commission in Spain was low and split, with about 40% for and just over 40% against (Aguilar et al., Citation2011). Currently, the country is at an interesting moment, as it is reviewing its approach to the past (see the next section). In 2007, a Law of Historical MemoryFootnote5 initiated the process and, at the time of the survey (October 2021), the government had declared its intention to reform the issue and was working on a new Law of Democratic Memory (passed in October 2022).Footnote6 Therefore, there was an opportunity to explore public opinion around different forms of pursuing the truth, from the private and individualized methods, which were the status quo at the time, to a formal and public process, during a period when the issue was salient but the forms were as yet undetermined.

Case background

An estimated 800,000 people lost their lives through legal and extrajudicial killings during Spain’s Civil War (19360–1939), and around 50,000 opponents to Franco’s regime were killed during the 1939–1975 dictatorship, alongside more than 300,000 people who were sent to concentration camps and many more into exile (Aguilar, Citation2008b; Aguilar et al., Citation2011). Yet, Spain’s transition to democracy has often been described as peaceful and successful and praised as a model to follow (Lopez Guerra, Citation1998). During the transition period, the approach was of silence and forgetting the past, and it was argued that leaving the past behind was the only way to ensure a peaceful transition to democracy (Aguilar, Citation2002, Citation2008a). A pact of forgetting instituted an amnesty lawFootnote7 that shielded the Franco regime from any judicial proceedings (Aguilar, Citation2009). This measure was presented and is still considered by many as the basis for reconciliation among Spaniards (Escudero, Citation2014). A limited and fragmented reparative process took place between 1976 and 1984 involving different categories of beneficiaries on the Republican side (Aguilar, Citation2009). However, transitional justice measures that are usually considered to be fundamental during a transition out of a period of gross human rights violations were never implemented during Spain’s democratization, for example, official condemnation of the dictatorship, symbolic measures aimed at the reparation of the victims, vetting, the creation of a truth commission, particularly not bringing perpetrators of human rights violations to trial.

Although the civil war was a long time ago, the more recent political violence from the Franco era is well within living memory, and relatives of those killed are still alive.Footnote8 Furthermore, recent studies show that victimization can resonate through generations (Balcells Citation2012; Lupu & Peisakhin Citation2017; Hadzic et al., Citation2020). Thus, in recent years, national and international organizations began pointing out that Spain was ignoring important obligations that are recognized under international law. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch supported the claims of victims and lobbied for them on the international political stage (Escudero, Citation2014), while the United Nations and the European Union denounced Spain’s policy of silencing and forgetting (Davis, Citation2005). In parallel, from 2000, a social and political debate began in Spain about the shortcomings of previous transitional justice measures (Aguilar, Citation2008b), driven by factors such as generational change, the actions of a private association devoted to locating and exhuming mass graves dating from the Civil War (Association for the Recuperation of Memory), and the actions by Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzón in ordering Chilean President Pinochet’s arrest in London under the principle of universal jurisdiction (Davis, Citation2005; Golob, Citation2008).

The resulting debate was two-sided, mirroring the idea of las dos Españas—namely, the existence of two opposed Spains. On one side, the conservative social and national political forces, represented mainly by the right-wing People’s Party (Partido Popular, PP), positioned themselves against “digging up the past,” framing this action as a way to incite feelings of revenge, hatred, and division among the population. In contrast, progressive political parties and social associations, such as the left-wing Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and United Left (Izquierda Unida), urged for policies aimed at dignifying the victims of the Civil War and the dictatorship, highlighting the duty of the state to reveal the truth.

In 2007, during the government of the PSOE, the Law of Historical Memory was passed. It deals with four main issues: the establishment of a more comprehensive reparation scheme for victims, the exhumation of mass graves, the removal of Francoist symbols, and the regulation of access to archives. On one side, it met the opposition of the right-wing PP as creating ruptures within the country (Labanyi, Citation2008b). On the other, it was received with disappointment by many victims’ groups, such as the Association for the Recuperation of Memory and Amnesty International, (Escudero, Citation2014), with a main criticism being the way the law put forward memory as “a personal and family matter” (Labanyi, Citation2008a).

When the government switched to the right-wing PP in 2011, it cut funding for exhumations, effectively stopping the Memory Law. In 2014, the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation, and guarantees of nonrecurrence, Pablo de Grieff, gave an extensive and critical assessment to the United Nations of the implementation of the transitional justice measures in Spain. Again, a major criticism was the lack of any state policy seeking truth, with “no official information and no mechanisms for elucidating truth” (de Greiff, Citation2014, p. 1), along with the “privatization” of exhumations that led to the indifference of state bodies. Given this lack of state initiative, the Rapporteur called for the creation of some form of truth commission that would achieve “an exhaustive understanding of the human rights and humanitarian law violations” that had occurred (de Greiff, Citation2014, p. 11).

When the left-wing PSOE again regained power, it began to move forward new legislation, the Law on Democratic Memory, to address the failings of the previous law. The draft of the Law on Democratic Memory shifts some responsibilities to the state, including locating and exhuming mass graves and the institution of a public prosecutor’s office in charge of human rights and democratic memory, along with other proposals, such as the cancelation of all unjust sentences promulgated during the dictatorship, increased education about Franco’s repression, and the removal of Francoist symbols. The proposal led to fierce and frequent debates in Parliament between the government, on one side, and on the other, the PP and the far-right splinter party Vox that owed its popularity, in part, to the negation of historical memory (Xidias, Citation2021). One key aspect was that the proposal does not address international criticisms from the United Nations and Amnesty International that Spain should overturn the 1977 Amnesty Law, which became a key sticking point for the Catalan Republican Left (Esquerra Republicana Catalana, ERC), whose support was needed to pass the law. The law was passed in October 2022 (i.e., after the fielding of the survey) and both the PP and Vox have pledged in election campaigns to repeal it if they take power.

Method

Given that preconditions in society, design of a truth commission, and impact of a truth commission are tangled together, testing of how design affects outcomes is difficult, if not impossible, to assess with observational data. We therefore use an experiment to separate out the different effects. Experiments have strong internal validity by isolating the impact of the experimental difference—that is, the design of the truth commission—on the different forms of reconciliation. We embedded the experiment into an original online survey in Spain that ran October 6–8, 2021.Footnote9 The survey was delivered by Netquest, a survey marketing firm that runs regular political surveys around the world. The sample was of 1,051 respondents aged 18 and older across the territory of Spain, with quotas for age and sex. Each treatment group was 350 respondents and was randomly generated, again with the same quotas.Footnote10

The experiment used short vignette primes. First, respondents were told that they would look at hypothetical situations. At the time of the survey, there was discussion about a range of different possible ways to pursue truth, particularly around looking for the disappeared, where options ranged from private initiatives, as in the status quo, to a government-authorized search, but nothing was decided. Then, all respondents were given a short text that set the context for the subsequent information. This text stated, “In the past few months, a law has been approved in Spain that will examine the events of the Civil War and the Franco era.”Footnote11 Following this preamble, the sample was randomized into three groups and each group received a prime of a different hypothetical scenario and then were asked their degree of agreement with the outcome statements.

The first prime reversed the introduction of a commission and was used to create a hypothetical situation similar to the status quo at the time of the survey. The second prime captured thin truth, in which events were investigated but the results were shared only with the victims’ families, and for their eyes only. The third prime captured thick truth that produced a public report that went beyond the events to look also at the causes and consequences ().Footnote12

Table 2. Experimental primes.

We included four different questions to operationalize different dependent variables. Each question took the form of agreement with a statement, and the agreement scale ran from 0 (“I do not agree at all”) to 10 (“I totally agree”). The outcome questions captured (1) whether there should be any investigation into the past, (2) expectations about individual-level closure, and (3) expectations about society-level closure and (4) reconciliation between opposing groups in society. The statements were, “it is not a good idea to stir up the past,” “it [the pursuit of truth] will help victims turn the page,” “it will help society turn the page,” and “it will help groups that have different views about the past live together,” all randomly presented.

Ideological self-placement was measured by positioning on the left-right scale. The questions stated, “I consider myself politically on the right” and respondents could answer on a 10-point agreement scale that ran from 0 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree). The answers were then calibrated into three groups—left wing, moderates, and right wing—by taking the proportions from national survey data.Footnote13 In our sample, 44% were left wing, 41% were moderates, and 15% were right wing.Footnote14

The survey also included a series of potential confounding variables that previous research finds impact on perspectives in Spain on transitional justice (Aguilar et al., Citation2011). Thus, we included religiosity, measured by degree of agreement with the statement, “I go to church often,” and victimization during the Civil War and/or Franco dictatorship, measured by degree of agreement with the statement, “I consider myself or my family to be victims of the Civil War or the Franco dictatorship.”

We further included two other variables to measure political attitudes. The first captured political efficacy and was measured with the degree of agreement with the statement, “I believe my vote makes a difference.” The second captured political trust and was measured with the degree of agreement with the statement, “In general, I trust the institutions of my country.”Footnote15 The variables were complemented with the demographic questions on sex, coded 1 for female and 0 otherwise; age, reported in three categories of 18–34, 35–64, and 65+; and education, reported in four categories of low secondary, high secondary, technical training, and university or postgraduate.

To estimate the effects of our treatment conditions on the outcome questions, we ran OLS regressions of the dependent variables, including the treatments and the confounding and control variables.Footnote16 The treatment was interacted with the respondents’ political positioning, as the issue of historical memory is a strongly partisan issue in Spain and also members of the left wing overall consider themselves more as victims, and the right-wing members consider their group more as perpetrators (although with actions justified as being required to defend and hold the nation together; see Núñez Seixas, Citation2005). We tested the main claim that respondents with different political orientations evaluate dealing with the past differently, while also testing whether different formats can influence those views. The results show the predictive probabilities of the treatment and polarization variables.

Findings

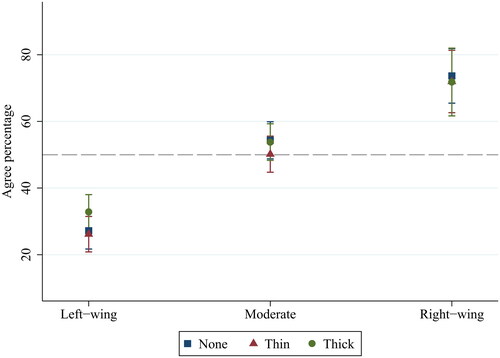

We first look at views on dealing with the past, in response to the statement that it is bad to disturb the past ().

The results clearly show large and significant differences between each of the three political orientations (left wing, moderates, and right wing). Those who were right wing were 72%–73% in agreement with the statement that it is bad to disturb the past, while those who were left wing were only 26%–33% in agreement. The moderates were largely 50/50 on this issue. This result serves to show the deep polarization that exists on the topic of transitional justice and opening the past in Spain. We also see that these views are consistent across each of the experimental treatments, which is not surprising, as this question captures an underlying perspective. We can consider this question a benchmark of the degree of polarization on the issue.

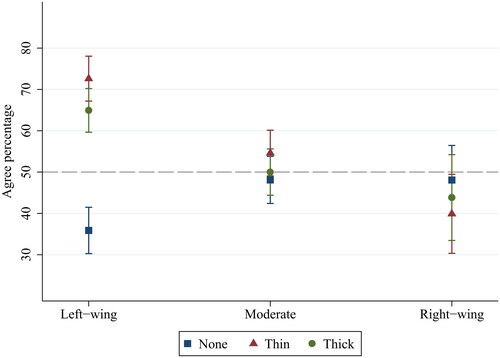

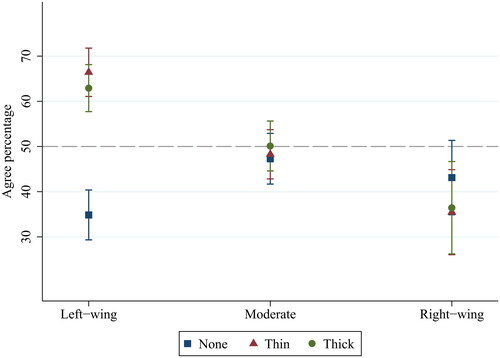

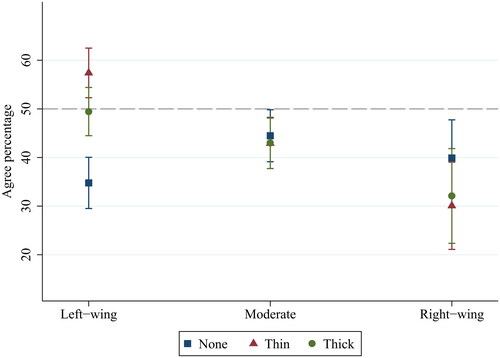

We then turn to the outcome questions and look at individual closure for victims (), societal closure (), and societal reconciliation ().

Figure 2. Degree of agreement that commission will help victims turn the page, by political position.

Figure 3. Degree of agreement that commission will help society turn the page, by political position.

Figure 4. Degree of agreement that commission will help groups live together, by political position.

Across all graphs, we see negative views when the pursuit of truth does not happen (squares in all figures). This is unsurprising, as this result captures both views on the pursuit of truth but also views on the government not following through on a policy. Therefore, we should be cautious about interpreting the absolute values of support. Rather, our main focus of interest is whether there is a difference between thin truth and thick truth across different forms of reconciliation and within different political groups.

Our expectations around thin truth were, first, that that it would be evaluated more positively for individual closure () rather than the two social forms of reconciliation ( and ) and, second, that both left-wing and right-wing respondents would have similar attitudes to thin truth (triangles in all figures). The left wing were net positive (above 50%) on all the forms of reconciliation. On victims turning the page, levels of support were 73%; on society turning the page, support was 66%; and for groups living together, support was 57%. These differences are significant, so we can infer that, at least in the case of the left wing, support for thin truth is high, but with significantly higher endorsement for individual closure rather than for societal reconciliation. We argue that left-wing respondents are positive about any truth commission because the left-wing cleavage overlays the victim cleavage and so they see benefits from the exposure of truth. The higher level of expected individual reconciliation, compared with societal reconciliation, shows that these respondents take into account the polarizing effects of the truth commission, even when it gives only thin truth.

On the second part of the expectation, we see that the left-wing and right-wing respondents did not hold similar views. Indeed, the right-wing respondents were net negative about thin truth across all the forms of reconciliation, with victims turning the page at 40%; society turning the page at 35%; and groups living together at 30%. The differences between the left-wing and right-wing respondents are significant in all the forms of reconciliation. The right-wing cleavage overlays the perpetrator cleavage and so the right-wing rejects revelations of the truth.

Our expectations around thick truth were, first, that only the left-wing would have positive evaluations but also, second, these would be positive across all forms of reconciliation. The findings show that both these expectations are broadly supported. On victims turning the page, levels of support were 67%; on society turning the page, support was 63%; although for groups living together, support was neutral at 49%. However, we should nuance these results somewhat. First, although the left-wing members were positive, the levels of support were lower than for thin truth (although not significantly), whereas we would expect the left wing to be more positive about thick truth compared to thin truth. Second, the result for groups living together was neutral and was the lowest result for the left wing. These results reveal that, as before, left-wing respondents were influenced by the negative polarizing effects, and in the case of thick truth these effects outweighed the potential benefits of a genuine evaluation of the structural causes of the atrocities. This finding may be a function of time, if respondents think the systemic features of society are too entrenched to change, and future research could explore whether this result holds up in light of more recent examples. The right-wing members were net negative across all the forms of reconciliation, with victims turning the page at 43%, society turning the page at 36%, and groups living together at 32%. Importantly, the right wing was no more negative about thick truth than about thin truth.

Discussion

The main contribution of this article is to understanding whether different designs of the pursuit of truth can alleviate some of the problems around addressing the past in polarized societies. The blunt answer is no. Truth commissions aim for thick truth, exposing a pattern of past events, yet some argue this approach is more dangerous in polarized societies as it can inspire a structural-level interpretation of the past. By contrast, thin truth is hidden and private. Although such a form of truth goes against the aims of truth commissions, some countries try to limit investigations to thin truth, and it could be said that at least it brings relief to victims and some closure. In a divided society, it is important to know whether there can be any public acceptance for such an approach, which might outweigh the disadvantages.

Our findings show that this is not the case. First, there is no significant difference across different forms of reconciliation, so having thin truth is not a way to bring relief to victims nor does it impact social outcomes. Second, right-wing respondents are opposed to thin truth across all forms of reconciliation. Therefore, thin truth is not a way to avoid the underlying polarization in society. Third, all the results are driven by preexisting polarization. Even a hidden, private, and thin form of truth is not attractive to the right-wing respondents, even for the most personal outcome, which is to bring relief to victims. In other words, no form of design will overcome the right-wing antipathy to the idea of pursuing the truth.

On the other hand, the findings also expose the dangers of thick truth. The left wing is supportive about thick truth for most forms of reconciliation, with the notable exception of whether it would help groups live together. The normative expectation of transitional justice is that a public commission creates a public version of the truth, and that such a commission helps society close the books on disputes around the past and move on, enabling groups to live together. Tellingly, even our left-wing respondents were ambivalent about whether such an intervention would help societal reconciliation. These results are consistent with the findings on a backlash to symbolic transitional justice (Villamil & Balcells, Citation2021), and here the same effect is shown with a different transitional justice measure. The issue of the past is politicized, relevant, and sparks extremely polarized responses.

Conclusion

The pursuit of truth continues to be popular around the world in response to transitional situations and even as a way of dealing with traumatic situations from the past, such as colonialization and slavery. Yet, the impacts of these actions are not clear, with claims that they entrench divisions. Some argue that this is particularly true in divided and polarized societies.

This article tackles this claim head on and examines whether anything would be gained from the morally distasteful solution of taking a minimalist strategy and using a private and individualized approach in order to produce a thin truth, rather than a more conventional and comprehensive truth commission. With some relief, we find that such a way of pursuing the truth does not make a difference. The depressing significance of this finding, however, is that the views on the endeavor are already so polarized that in no instance does the right wing support any form of action. The antipathy cannot be overcome through a different design that avoids a formalized truth commission.

As with any experiment, the research benefits from strong internal validity, but the generalizability of the results should be explored with similar experiments in other transitional situations, particularly ones that are more recent. Another line of inquiry is to look more deeply at the interaction between partisanship and transitional justice measures, to isolate and identify the mechanisms that lead to rejection of opening up the past. Studies could also look at other forms of divided societies, such as those in which the cleavage is ethnic or ideological, or societies in which the cleavage does not overlap the characterization as perpetrator. Such studies could expose alternative mechanisms that are at work.

This study considered truth commission design in isolation, but in some processes it is one part of a transitional justice package. Further research could engage more deeply with the impact of different combinations of trials and truth commissions, which can be particularly polarizing in divided societies.

The results have implications for policy. Reassuringly, they show that there is no advantage to limiting the content or outreach of a truth commission. As such, they bring empirical support to the normative claims around truth commissions. Such an understanding is crucial in order to enable transitional justice to truly help create a new future in a transitional country.

Ethical clearance

The study received ethical clearance from Universitat Pompeu Fabra, CIREP 208, prior to the delivery of the survey.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nada Ahmed, Laia Balcells, António Luís Dias, Vicente Druliolle, Filipa Raimundo, Joana Rebelo Morais, and attendees at the 2022 International Conference for Europeanists and 2022 Conflict Research Society conference for useful comments.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lesley-Ann Daniels

Lesley-Ann Daniels holds a doctorate from the Universitat Pompeu Fabra and is a Marie Curie Fellow at the University of Oslo. Her research interests are attitudes to peace, conflict resolution and transitional justice.

Virginia Zalunardo

Virginia Zalunardo holds a master’s degree in International Development from the Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals and is currently a Senior Business Consultant at NTT DATA working in research projects for European and international organisations.

Notes

1 Here are examples of some different combinations: In Sierra Leone (2002–2004), the truth commission and trials ran in two separate processes with no formal relationship; in Guatemala (1997–1999), the truth commission report gave rise to prosecutions for crimes; in Colombia (2017–2022), giving information on the facts of involvement in crimes and expressing responsibility and remorse has led to reduced sentences for perpetrators. A more detailed examination of the relationship between trials and truth commissions is beyond the scope of this article.

2 See Aguilar et al. (Citation2011), Dyrstad and Binningsbø (Citation2019), Hall et al. (Citation2017), Samii (Citation2013), and Tellez (Citation2019a, Citation2019b) for works on the impact of transitional justice more broadly.

3 The two other categories created by this division are a personal broad-brush report that is directed to the individual but examines the patterns of events, which has empirical contradictions as the aim of a broad report is to identify structural dynamics and the audience is society; and a limited report that is publicly available but focuses only on the forensic facts. Such a report is empirically feasible but of less theoretical interest, as it does not engage with the structural dynamics.

4 This is the motivation behind initiatives such as the Colombian government-sponsored database the System of Information Network on the Disappeared and Dead (SIRDEC), maintained by the Institute of Forensic Medicine, which keeps a national register of the disappeared and helps individuals to trace those who have been lost.

5 Law 52/2007 that recognised and broadened the rights and establishes measures in favor of those who suffered persecution or violence during the Civil War and the dictatorship (Law of Historical Memory) (Ley por la que se reconocen y amplían derechos y se establecen medidas en favor de quienes padecieron persecución o violencia durante la guerra civil y la dictadura). See Boletín Oficial del Estado BOE-A-2007-22296. Available at https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2007/12/26/52/con.

6 Law 20/2022, 19 October, of Democratic Memory (Ley de Memoria Democrática). See Boletín Oficial del Estado BOE-252- 20/10/2022. See Boletín Oficial del Estado BOE-A-2007-22296. Available at https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2007/12/26/52/con. The law was supported by the PSOE, United We Can (Podemos), National Basque Party (PNV), Basque Country Unite (EH Bildu), Commitment (Compromís), and the Catalan Democratic European Party (PDeCAT).

7 Law 46/1977 of Amnesty (Ley 46/1977, de 15 de octubre, de Amnistía). See Boletín Oficial del Estado BOE-A-1977-24937. Available at https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/1977/10/15/46/con.

8 It is not unusual to investigate historical human rights abuses. For example, the Czech Republic’s Office for the Documentation and the Investigation of the Crimes of Communism was set up in 1995 to investigate crimes committed from 1948 to 1989, and the 2018 Seychelles Truth, Reconciliation and National Unity Commission looks at the human rights abuses committed in the 1977 coup, while more broadly the 2009 Truth and Justice Commission in Mauritius examined the effects of 370 years of slavery.

9 The study received ethical clearance from Universitat Pompeu Fabra, CIREP 208 prior to the delivery of the survey.

10 The sample size of 350 respondents per group allows us to reach .8 power with an expected effect size of .23.

11 All the primes contained reference to the law in order to avoid excessive variation between the control group and the treatments and to keep the focus on the variation of the forms of truth.

12 To avoid deception, the respondents were told prior to the treatment that they would be looking at a hypothetical statement, and at the end of the survey there was a debriefing statement that clarified “at the present moment, it has not been decided how to implement this law.”

13 Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, Barómetro de septiembre 2021, Estudio 3334.

14 The corresponding categories in the CIS survey are 44% left-wing (1–4 out of 10 on a left-right scale), 38% moderates (5–6 out of 10), and 18% right-wing (7–10). The results are the same if using a binary variable corresponding to right-wing and all else, whether right-wing is 6–10 or 7–10.

15 Each of the agreement questions is measured on a disagreement-agreement scale, in which 0 is strongly disagree and 10 is strongly agree. The answers are then converted to dummy variables by coding answers 6–10 as 1 (high) and the rest as 0.

16 Results are the same without the confounding and control variables.

References

- Aguilar, P. (2002). Memory and amnesia: The role of the Spanish Civil War in the transition to democracy. Berghahn Books.

- Aguilar, P. (2008a). Políticas de la memoria y memorias de la política. El caso español en perspectiva comparada. Alianza Editorial.

- Aguilar, P. (2008b). Transitional or post-transitional justice? Recent developments in the Spanish case. South European Society and Politics, 13(4), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608740902735000

- Aguilar, P. (2009). The timing and the scope of reparation, truth and justice measures: A comparison of the Spanish, Argentinian and Chilean cases. In K. Ambos, J. Large, & M. Wierda (Eds.), Building a future on peace and justice: Studies on transitional justice, peace and development. The Nuremberg declaration on peace and justice (pp. 503–529). Springer-Verlag.

- Aguilar, P., Balcells, L., & Cebolla-Boado, H. (2011). Determinants of attitudes toward transitional justice. Comparative Political Studies, 44(10), 1397–1430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011407468

- Balcells, L. (2012). The consequences of victimization on political identities. Politics & Society, 40(3), 311–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329211424721

- Bar-Tal, D., & Bennick, G. H. (2004). The nature of reconciliation as an outcome and as a process. In Y. Bar-Simon-Tov (Ed.), From conflict resolution to reconciliation (pp. 11–38). Oxford University Press.

- Bassiouni, M. C. (1996). Searching for peace and achieving justice: The need for accountability. Law and Contemporary Problems, 59(4), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/1192187

- Brahm, E. (2007). Uncovering the truth: Examining truth commission success and impact. International Studies Perspectives, 8(1), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-3585.2007.00267.x

- Brett, R. (2022). In the aftermath of Genocide: Guatemala’s failed reconciliation. Peacebuilding, 10(4), 382–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2022.2027660

- Chapman, A. R., & Ball, P. (2001). The truth of truth commissions: Comparative lessons from Haiti, South Africa, and Guatemala. Human Rights Quarterly, 23(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2001.0005

- Commission for Historical Clarification. (n.d). Guatemala memory of silence. Retrieved October 2, 2023, https://hrdag.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/CEHreport-english.pdf

- Crocker, D. (2000). Truth commissions, transitional justice, and civil society. In R. I. Rotberg & D. Thompson (Eds.) Truth v. justice: The morality of truth commissions (pp. 99–121). Princeton University Press.

- Daly, E. (2008). Truth skepticism: An inquiry into the value of truth in times of transition. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 2(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijn004

- Daly, E., & Sarkin, J. (2007). Reconciliation in divided societies: Finding common ground. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Dancy, G., Kim, H., & Wiebelhaus-Brahm, E. (2010). The turn to truth: Trends in truth commission experimentation. Journal of Human Rights, 9(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754830903530326

- Dancy, G., & Thoms, O. T. (2022). Do truth commissions really improve democracy? Comparative Political Studies, 55(4), 555–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140211024305

- Davis, M. (2005). Is Spain recovering its memory? Breaking the “Pacto del Olvido”. Human Rights Quarterly, 27(3), 858–880. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2005.0034

- de Greiff, P. (2014). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence. UN: A/HRC/30/42. Retrieved October 2, 2023, from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/803412?ln=en, last

- Dyrstad, K., & Binningsbø, H. M. (2019). Between punishment and impunity: Public support for reactions against perpetrators in Guatemala, Nepal and Northern Ireland. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 13(1), 155–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijy032

- Escudero, R. (2014). Road to impunity: The absence of transitional justice programs in Spain. Human Rights Quarterly, 36(1), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2014.0010

- Fletcher, L. E., & Weinstein, H. M. (2002). Violence and social repair: Rethinking the contribution of justice to reconciliation. Human Rights Quarterly, 24(3), 573–639. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2002.0033

- Gibson, J. L. (2004a). Does truth lead to reconciliation? Testing the causal assumptions of the South African truth and reconciliation process. American Journal of Political Science, 48(2), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519878

- Gibson, J. L. (2004b). Overcoming apartheid: Can truth reconcile a divided nation? Russell Sage Foundation.

- Gibson, J. L. (2006). The contributions of truth to reconciliation: Lessons from South Africa. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 50(3), 409–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002706287115

- Gibson, J. L., & Gouws, A. (1999). Truth and reconciliation in South Africa: Attributions of blame and the struggle over apartheid. American Political Science Review, 93(3), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2307/2585571

- Gillooly, S., Solomon, D., & Zvobgo, K. (2024). Co-opting truth: Explaining quasi-judicial institutions in authoritarian regimes. Human Rights Quarterly, 46(1), 67–97.

- Golob, S. R. (2008). Volver: The return of/to transitional justice politics in Spain. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, 9(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14636200802283647

- Gonzalez-Enriquez, C., Aguilar, P., & Barahona de Brito, A. (2001). Conclusions. In A. Barahona de Brito, C. Gonzalez-Enriquez, & P. Aguilar (Eds.), The politics of memory: Transitional justice in democratizing societies (pp. 303–314). Oxford University Press.

- Hadzic, D., Carlson, D., & Tavits, M. (2020). How exposure to violence affects ethnic voting. British Journal of Political Science, 50(1), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000448

- Hall, J., Kovras, I., Stefanovic, D., & Loizides, N. (2017). Exposure to violence and attitudes towards transitional justice. Political Psychology, 39(2), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12412

- Hayner, P. B. (2011). Unspeakable truths: Transitional justice and the challenge of truth commissions (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Herman, J. L. (2022). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence - From domestic abuse to political terror (4th ed.). Hachette.

- Kochanski, A. (2020). Mandating truth: Patterns and trends in truth commission design. Human Rights Review, 21(2), 113–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-020-00586-x

- Labanyi, J. (2008a). Entrevista con Emilio Silva. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, 9(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/14636200802283654

- Labanyi, J. (2008b). The politics of memory in contemporary Spain. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, 9(2), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/14636200802283621

- Lopez Guerra, L. (1998). The application of the Spanish model in the constitutional transitions in Central and Eastern Europe. Cardozo Law Review 1997-1998, 19, 1937–1952.

- Lupu, N., & Peisakhin, L. (2017). The legacy of political violence across generations. American Journal of Political Science, 61(4), 836–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12327

- Mamdani, M. (2005). Amnesty or impunity? A preliminary critique of the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (TRC). Diacritics, 32(3), 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/dia.2005.0005

- Mendeloff, D. (2004). Truth-seeking, truth-telling, and postconflict peacebuilding: Curb the enthusiasm? International Studies Review, 6(3), 355–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-9488.2004.00421.x

- Mendeloff, D. (2009). Trauma and vengeance: Assessing the psychological and emotional effects of post-conflict justice. Human Rights Quarterly, 31(3), 592–623. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.0.0100

- Minow, M. (1998). Between vengeance and forgiveness: Facing history after genocide and mass violence. Beacon Press.

- Núñez Seixas, X.-M. (2005). Nations in arms against the invader: On nationalist discourses during the Spanish civil war. In C. Ealham & M. Richards (Eds.), The splintering of Spain: Cultural history and the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39 (pp. 45–67). Cambridge University Press.

- Olsen, T. D., Payne, L. A., & Reiter, A. G. (2010a). The justice balance: When transitional justice improves human rights and democracy. Human Rights Quarterly, 32(4), 980–1007. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2010.0021

- Olsen, T. D., Payne, L. A., & Reiter, A. G. (2010b). Transitional justice in balance: Comparing processes, weighing efficacy. United States Institute of Peace Press.

- Olsen, T. D., Payne, L. A., Reiter, A. G., & Wiebelhaus-Brahm, E. (2010c). When truth commissions improve human rights. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 4(3), 457–476. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijq021

- Orentlicher, D. F. (2005). Updated set of principles for the protection and promotion of human rights through action to combat impunity (Vol. E/CN.4/200, D. Orentlicher, Ed.). United Nations Commission on Human Rights.

- Orriols, L., & León, S. (2020). Looking for affective polarisation in Spain: PSOE and podemos from conflict to coalition. South European Society and Politics, 25(3-4), 351–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2021.1911440

- Pion-Berlin, D. (1994). To prosecute or to pardon - Human rights decisions in the Latin American Southern cone. Human Rights Quarterly, 16(1), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.2307/762413

- Robins, S. (2011). Towards victim-centred transitional justice: Understanding the needs of families of the disappeared in postconflict Nepal. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 5(1), 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijq027

- Samii, C. (2013). Who wants to forgive and forget? Transitional justice preferences in postwar Burundi. Journal of Peace Research, 50(2), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343312463713

- Sarkin, J. (1999). The necessity and challenges of establishing a truth and reconciliation commission in Rwanda. Human Rights Quarterly, 21(3), 767–823. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.1999.0042

- Sikkink, K., & Walling, C. B. (2007). The impact of human rights trials in Latin America. Journal of Peace Research, 44(4), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343307078953

- Skaar, E. (2012). Reconciliation in a transitional justice perspective. Transitional Justice Review, 1(1), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.5206/tjr.2012.1.1.4

- Snyder, J., & Vinjamuri, L. (2003). Trials and errors: Principles and pragmatism in strategies of international justice. International Security, 28(3), 5–44. https://doi.org/10.1162/016228803773100066

- Stahn, C. (2005). The geometry of transitional justice: Choices of institutional design. Leiden Journal of International Law, 18(3), 425–466. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156505002827

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Teitel, R. G. (2003). Transitional justice genealogy. Harvard Human Rights Journal, 16(69), 72–74.

- Tellez, J. F. (2019a). Peace agreement design and public support for peace: Evidence from Colombia. Journal of Peace Research, 56(6), 827–844. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319853603

- Tellez, J. F. (2019b). Worlds apart: Conflict exposure and preferences for peace. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(4), 1053–1076. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002718775825

- Torcal, M., & Comellas, J. M. (2022). Affective polarisation in times of political instability and conflict. Spain from a comparative perspective. South European Society and Politics, 27(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2022.2044236

- TRC South Africa. (1998). Truth and Reconciliation Commission South Africa report. Retrieved October 2, 2023, from https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/

- Tyler, T. R. (2003). Procedural justice, legitimacy, and the effective rule of law. Crime and Justice, 30, 283–357. https://doi.org/10.1086/652233

- Tyler, T. R., & Jackson, J. (2014). Popular legitimacy and the exercise of legal authority: Motivating compliance, cooperation, and engagement. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 20(1), 78–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034514

- van Boven, T. (2005). Basic principles and guidelines on the right to a remedy and reparation for victims of gross violations of international human rights law and serious violations of international humanitarian law. Vol. UNGA Res 6. United Nations.

- van der Merwe, H., Baxter, V., & Chapman, A. R. (2009). Assessing the impact of transitional justice. United States Institute of Peace Press.

- Villamil, F., & Balcells, L. (2021). Do TJ policies cause backlash? Evidence from street name changes in Spain. Research & Politics, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/20531680211058550

- Wiebelhaus-Brahm, E. (2010). Truth commissions and transitional societies: The impact on human rights and democracy. Routledge.

- Xidias, J. (2021). From Franco to Vox: Historical memory and the far right in Spain. CARR Research. Insight 2021.1. Centre for the Analysis of the Radical Right.

- Zvobgo, K. (2019). Designing truth: Facilitating perpetrator testimony at truth commissions. Journal of Human Rights, 18(1), 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2018.1543017