ABSTRACT

In this study, the paradoxes and difficulties of using WhatsApp for meaningful education are highlighted. As a case study of technology implementation, the author employs virtual ethnography and interviews with supervisors, developers and teachers to examine all significant pedagogical initiatives in Israel’s high schools that utilise WhatsApp. These initiatives are analysed through the theoretical lens of sharing and its cultures of production and circulation. Sharing and circulating are fundamental epistemological aspects of knowledge in new media as they play a major part in how knowledge is created, perceived and learned. Indeed, the findings show that using WhatsApp broadens and diversifies classroom instructional practices, including shifts towards more dialogic teaching, but at the same time, traditional communicative assumptions, conservative school modalities, power structure and epistemologies are maintained. Sharing is now seen as a pedagogical practice, yet implementing WhatsApp in schools happens while its epistemological aspects are narrowed.

Introduction

Seventy-three per cent of the global population aged 10 and above owns a mobile phone (and over 80% in the Americas, CIS and Europe; ITU, Citation2023). As a result of these numbers, schools are adapting social network-based pedagogies (Rosenberg & Asterhan, Citation2018) and contributing to the expansion of Blended Learning, which is conceptualised as spearheading neoliberal efforts to re-make education towards a more data-driven and digitally reliant environment (Ball & Grimaldi, Citation2021). But what does it mean to blend the school’s ‘culture of acquisition’ (Lave, Citation1997) with the new media’s culture of sharing and circulation? Non-digital concepts of acquisition and transmission fail to convey how knowledge is produced and meaning is negotiated through online sharing and circulation (Lampinen, Citation2015). The epistemological ramifications of the ‘blend’ are understudied. Analysis of such pedagogies in terms of knowledge production and circulation is required to understand contemporary education and the nature of knowledge work that schools enhance.

While the research is clear about how educational technology affects teacher–student classroom interactions, it lacks conceptualisation and understanding of pedagogical practices with social media (Harper, Citation2018). Reviewing social media use in classrooms, Van Den Beemt et al. (Citation2020) further argued that the research fails to take into account the interrelations between the different levels of curriculum: school (intended level), teachers (implemented level) and students (attained level). The current study uses a large-scale case study to deepen our understanding of this educational phenomenon, which is embedded in its cultural and sociological context and, at the same time, is not solely dependent on it. In other words, this study looks at how WhatsApp is used for teaching in Israeli high schools. It critically examines how educational technology is applied (Facer & Selwyn, Citation2021), focusing on the relations between the intended and the implemented levels (Van Den Beemt et al., Citation2020).

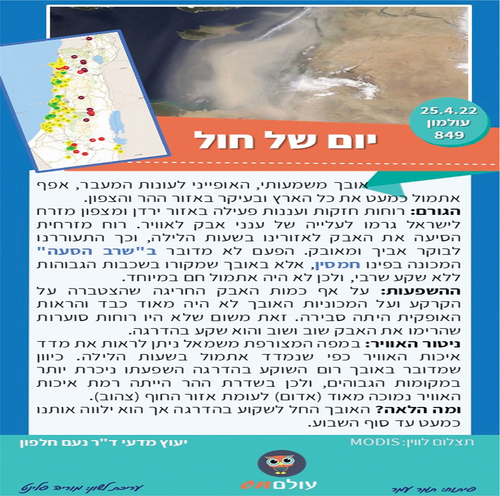

In Israeli high schools, WhatsApp is widely used for pedagogical purposes. Israel has adopted a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) policy, facilitating vast techno-pedagogical options for schools, in terms of device use and pedagogical opportunities. Consequently, the implementation of the BYOD policy has turned principals, pedagogical coordinators and teacher-entrepreneurs into influential policymakers, beyond their own schools (Slakmon, Citation2017). Tailored to the BYOD policy and based on the already existing closed designated WhatsApp groups formed by teachers with their students, various Israeli teacher-initiators devised WhatsApp subject-matter small ‘news agencies’, circulating subject-matter news to groups of subscribed teachers, who in turn can use these short segments of information in their teaching. presents a typical post of the ‘agencies’. To date, 14 national-scale WhatsApp-based pedagogical initiatives operate, reaching more than 18,000 members, mostly teachers. Twelve projects were formed around Geography, Biology, STEM disciplines Physics and Space Science, History, Literacy and English as a foreign language (EFL). One project addresses high school students and offers informal, out-of-school learning opportunities, while another is dedicated to the circulation of technology-based pedagogical knowledge in all disciplines. There are 20,268 Israeli high school teachers in these disciplines (Central Bureau Statistics Israel, Citation2019; see for segmentation by discipline). Consequently, the exposure to the projects among teachers is vast. Since Israeli teachers tend to create classroom WhatsApp groups (Rosenberg & Asterhan, Citation2018) for every classroom they teach, the potential distribution range of the projects reaches nearly every Israeli high school student.

Table 1. WhatsApp-based pedagogical initiatives in Israel.

By surveying the nature of the initiatives, the extent of distribution and the common pedagogical uses of WhatsApp in secondary schools in Israel, the study will shed light on the pedagogical culture that emerges at the intersection between digital sharing and ICT-based instructional initiatives. The research focuses on the following questions: what are the pedagogical uses of WhatsApp and their underlying rationale and how do schools reconcile WhatsApp’s social network knowledge production and circulation with existing perceptions on knowledge and learning? While this research is based in Israel, it has broader implications. WhatsApp use for pedagogy is an understudied phenomenon on a national scale. The use of WhatsApp for educational is a global phenomenon, therefore understanding its pedagogical uses and the challenges and opportunities it presents can inform educators and researchers worldwide. Furthermore, the reconciliation of social network knowledge production with traditional perceptions of knowledge and learning is a universal educational challenge in the digital age.

Background

WhatsApp and education

WhatsApp is the most popular messaging app worldwide (Statista, Citation2024), representing a form of virtual sociability and intimacy (Karapanos et al., Citation2016), associated with feelings of togetherness, endless availability and a sense of belonging (Ahad & Lim, Citation2014; Matassi et al., Citation2019; O’Hara et al., Citation2014). While WhatsApp fosters an immersive digital environment that enhances social connections and communal experiences, it also presents challenges. This is evidenced by the significant prevalence of cyberbullying among younger users in educational settings. In Israel, 30% of students were victims of cyberbullying within classmates’ WhatsApp groups (Aizenkot & Kashy-Rosenbaum, Citation2021).

WhatsApp’s pedagogical uses have not been sufficiently investigated. Most of the studies are prospective in nature and have been conducted in higher educational settings (Farahian & Parhamnia, Citation2021; Schwarz et al., Citation2017) and, referring to social media in general, with students (Van Den Beemt et al., Citation2020). Studies conducted in schools reveal that students refer to the socio-emotional aspects of WhatsApp communication as the major educational benefits the application conveys, citing its contribution to communication between students, peer support, sense of belonging and self-expression (Cetinkaya, Citation2017). Teachers primarily use WhatsApp for creating closed classroom groups (Rosenberg & Asterhan, Citation2018) that serve mainly as a general additional communicative channel for organisational purposes (Abualrob & Nazzal, Citation2020). To a degree, WhatsApp replaces traditional communication channels and Learning Management Systems. Out-of-Class Communication, which improves classroom climate (Hershkovitz et al., Citation2019), is less common. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, pedagogical uses of WhatsApp, such as expanding learning towards transmedia studies, stretching classroom boundaries or extending learning beyond formal learning hours or beyond conventional learning goals, are less common and seldom reported (Amry, Citation2014; Budianto & Arifani, Citation2021; Costa-Sánchez & Guerrero-Pico, Citation2020). One exception is Kizel’s (Citation2019) study of youth’s WhatsApp philosophical community of inquiry. Four groups of secondary school students used WhatsApp for Philosophy for Children practices. Kizel argues that the WhatsApp virtual relations reported by the students go as far as resembling Buberian I – Thou relations (Buber, Citation1970), characterised by mutuality, presence and freedom. He thus describes WhatsApp communication as an ‘I-Space-Thou’ possibility for a full human encounter.

Sharing and the culture of circulation

I share therefore I am. (Turkle, Citation2015, p. 46)

Sharing is ‘a broad category of social practices’ (John, Citation2016, p. 5) with multiple meanings. On the one hand, sharing signals having something in common with someone else without dividing it into parts. The shared object remains intact. The sharer’s ownership is not impaired. In fact, the value of the shared object, including abstract objects, sometimes increases with circulation. On the other hand, the term is used for acts that are not ‘real’ sharing but sometimes resemble the digital version of commodity exchange, such as buying or lending, for example when it is used as a euphemism for selling personalised data to advertisers (Belk, Citation2007, Citation2014). Besides being a constituent activity of social media, sharing also operates in sharing economies and in the development of intimate relationships: these three arenas are designed and nurtured in such a way that the intimate relationships mediated by social media themselves are enhanced by the sharing economy (John, Citation2016).

Digital sharing contributes to the expansion of the public over the private. Sharing is directed from the private to the public and vice versa in a circle, which blurs the distinctions between the spheres (John, Citation2016; Papacharissi, Citation2010). The shared object moves downward (‘pushed’ by promoting agencies) and sideways by the other participants using their own public spheres, walls and channels. Sharing is an integral part of the contemporary capitalist knowledge economy. It is the very fundamental practice of social networks, and at the same time, in the eyes of cooperative economy proponents, it is viewed as a ‘remedy’ for contemporary economic problems (Bradley & Pargman, Citation2017). On both sides, though, it has a positive moral dimension, as it enacts values and emotions associated with care, as a technology both of caring for the self (Quinn & Powers, Citation2016) and of caring for the other by promoting commonality, trust, openness, fairness, mutuality and understanding.

The practice of sharing is seen as a reflective process of self-care and self-understanding (Quinn & Powers, Citation2016). Our subjectivity is tied to our actions and thoughts, which are shaped by our surroundings. In the case of social media, these platforms provide a platform for the expression of subjectivity. The role of visibility is emphasised in the formation of identity. The digital persona is constructed not only through one’s presence on social networks but also through sharing on these platforms. Teachers who are active on digital media are in a constant state of self-recreation and are cognisant of this impact. This understanding significantly influences their readiness to participate in the digital world (Asterhan & Rosenberg, Citation2015).

Reconciling social network knowledge production with traditional views of knowledge and learning is a universal educational challenge in the digital age. This research aims to explore the pedagogical applications of WhatsApp by asking: What are the pedagogical uses of WhatsApp and what is the rationale behind them? How do schools reconcile knowledge production and circulation within WhatsApp’s social network with existing perceptions of knowledge and learning?

ContextFootnote1

WhatsApp is widely integrated into the pedagogy in Israeli high schools for both organisational and instructional purposes. presents the 14 major WhatsApp-based pedagogical initiatives found and studied. As seen in , the exposure rate to WhatsApp initiatives varies across disciplines. The lowest rates of teachers’ exposure, found in EFL, literature and physics, are 21.5%, 23.2% and 29%, respectively. The history initiatives reach at least 63.9% (the estimation is based on History in the AM exposure rate and does not include Historium, since we don’t have data on cross-memberships). Geography projects are the most popular. Geography and biology exposure rates indicate that every teacher in these disciplines subscribes to the services. As a result, these figures are underestimated since they do not include teachers who circulate through alternative channels, such as Facebook, designated websites and Telegram, for which data is only partially available. Despite the platform, digital media literacy (Schreurs & Vandenbosch, Citation2021) is not considered an educational goal in either initiative.

Almost all of the projects (8 out of 14) function as traditional news agencies that are adapted to age groups through WhatsApp. Three projects, Historium, The Literary Blog and The Pocket Library, use WhatsApp to send links to a main internet site whenever updated materials are published there. All three are produced by the National Library and are linked to its humanities centre. One project, Balcony, also produced by the National Library, functions as an alternative curriculum for high school students. It has about 400 subscribers. One project, Going Easy on Digital, which closed in 2024, was developed by the Technology division of the Ministry of Education. It was dedicated to the dissemination of techno-pedagogical knowledge and introduction of updated technological tools for teachers.

Technically, the designated WhatsApp messages are created with Google Slides/PowerPoint/Canva templates. They contain an illustrative image and 100–200 words of informative text. At this point, the projects differ in dialogic potential. Some projects, including OlamOn, Olamon Physics and Good Morning Environment, save posts as JPEG and share them as pictures. As such, the posts are objects, not hypertext, and cannot contain links or invoke channel surfing. This format prevents receivers from editing the text. The JPEG format intentionally leaves information mediation in teachers’ hands. Other projects use dialogic potential differently. GMB uses two posts in each distribution, one with an intriguing image and the other with informative text. In this case, the image is shared as a closed, non-editable post, and the text is open for additional sharing but also for manipulations, so that the receivers can cut, paste, add to the text or integrate it into their posts/pedagogical works. Other projects send out posts as texts (WhatsApp Project, NLC). Typical texts, formats and design of the projects are presented in Appendix 1.

Materials & method

To study the frequency, content and style of WhatsApp posts, virtual ethnography (Falzon, Citation2012; Marcus, Citation1995) was used to follow and analyse the chains of production, circulation and use. The author and/or an assistant researcher were silent members in at least one WhatsApp group for each of the projects (five out of nine groups in OlamOn, participant observation in OlamOn composers’ WhatsApp group, named ‘OlamOn conversation’; six out of ten in Good Morning Biology (GMB); both groups of OlamOn Physics; one group of the other projects) (see for the collected data summary). In total, we joined 25 WhatsApp groups across various projects. Additionally, the initiatives’ websites, Telegram and Facebook pages were followed. Membership in the groups provided data on style, content, frequency of publications and consistency across groups. Participation in groups included documentation of discourse, publications and their nature, style and frequency.

Table 2. Data collection summary.

A semi-structured interview was conducted with the eight teacher-entrepreneurs of the projects, in which they described the initiative’s history, its vision, its objectives, its rationale, its future plans, how they are composing and circulating posts on a daily basis and many other aspects of their daily work. To understand the position of the Ministry of Education regarding the initiatives, the regulations and institutional support given to the projects, five interviews were conducted with senior officials in the Ministry of Education: the head of the pedagogical development wing in the Ministry of Education, also serving as the national supervisor for the instruction of geography, Ms. Dalia Fenig; the national supervisor for the instruction of biology (GMB), Dr Irit Sadeh; the national supervisor for the instruction of Physics (OlamOn Physics), Dr Zvika Aricha; the national supervisor for the instruction of English (WhatsApp Project), Dr Ziona Levy; the national supervisor for the instruction of History in Israel’s state-funded religious schools (History on the AM), Ms. Bilhah Gliksberg (the supervision is divided between two officials, one for the religious state-funded official schools, one for non-religious state-funded official schools).

Data on the views of the end-users, the teachers and the instruction enabled by the messages received was gathered in interviews with 54 teachers/active users and 16 teachers who quit the groups and stopped implementing the initiatives. During the interviews (via phone), teachers were asked about their sharing practices, how they use messages in and out of the classroom and the challenges they face when using social media. During the interviews, it became apparent that some teachers use more than one project. The interviews with these teachers were expanded to include their modes of use for each initiative.

Analysis

The data were analysed using a variety of methods. The analysis process was designed to understand the interaction between different curriculum levels: the school (intended level), teachers (implemented level) and students (attained level). For the WhatsApp posts, a blend of content and visual analysis techniques was utilised (Gaskell, Citation2000; Gomez-Cruz & Siles, Citation2021). This included examining the content, frequency, style, and production, circulation and use of these posts. The focus was on discourse, publications, nature, style and frequency within the groups.

The interviews were analysed using various content analysis techniques (Bauer, Citation2000). It involved descriptive coding and aggregation practices, assertions and statements. The aim was to allow categories and themes to emerge from the data. Second, through inference, a depiction of the ideological social and epistemological world from which the initiatives emerged was constructed. The interviews with teacher-entrepreneurs offered insights into the history, vision, aims, rationale and future plans of the projects. Interviews with senior officials in the Ministry of Education provided an understanding of the institutional perspective on these initiatives. Lastly, interviews with teachers/users shed light on their sharing practices, message usage in classrooms and beyond, and challenges encountered when using social media. This analysis helped us understand how WhatsApp initiatives are implemented and used in practice.

Results

WhatsApp’s pedagogical initiatives from the perspective of policymakers

Technology was cited as a key factor driving pedagogical innovation by all policy makers interviewed. They were enthusiastic about teachers’ initiatives like those discussed in this study. There were different views among them regarding how innovative WhatsApp projects are these days, compared with their initial emergence as educational innovations in 2014. All of them claimed that they were glad to use their own communication channels with teachers to help WhatsApp-based pedagogies expand and reach more teachers. The rationale that led to the endorsement of the first initiative, OlamOn, by Israel’s Ministry of Education and later to its replications in other disciplines is based on two pillars: first, policymakers see these teacher-led initiatives as a way to encourage teachers’ creativity and productivity, especially against the backdrop of teachers who only use ready-made instruction materials. Second, the initiatives are perceived as instrumental in the attempt to reconfigure school time by expanding digital space. Coming to terms with the improbability of reforming the core curricular structure of Israeli schools, and the need to transform learning within schools, the head of the pedagogical development administration in the Ministry of Education says:

The issue of integrating innovative technologies is the essence of my job … I understood that math (studies) would always get many (instruction) hours, that religion will get many hours in religious schools … (so) I said to myself, why fight over these hours? Let us use the hours nobody cares about, after school hours … There is a lot of time there, and the children are there. What are they doing? They social network … I must learn how to take advantage of these places. The children will learn without being aware that they are learning … (D. Fenig, personal communication, March 14, 2016)

Official support

Most projects receive the support and encouragement of national subject-matter supervisors. In each case, the supervision offices support the work and are in direct contact with the developers. The nature of the support and the type of involvement that the supervisors have with the entrepreneurs vary, from financial support to feedback on content, advice on alignment with official curriculum, integration with other technological tools, close personal guidance and distribution, depending on their perception of the centrality or importance of the initiative for their role. As of now, the government partially funds all programmes except GMB and OlamOn. However, only the initiatives central to the supervisor’s pedagogical goal are integrated into the curriculum. A pedagogical resource book was developed based on the posts (GMB); the WhatsApp Project was endorsed as a national learning environment to the extent that it was included in the national matriculation exams; History on the AM was modified to better adapt it to remote learning during COVID-19.

Informal alternative curriculum in the digital age

The WhatsApp initiatives serve as an alternative curriculum to the official approved one by composing and circulating posts related to the official curriculum. These posts are intended to be used for students’ learning. The initiators also work as mid-level pedagogical officials and their initiatives are supported, although loosely regulated, by subject-matter general supervisors. As informal as they may sound, these initiatives serve as a second curriculum, including all the political issues associated with formal and hidden curricular issues. The production of the posts resonates with considerations like those of traditional curricular design. For example, the dominance of Hebrew over Arabic is maintained despite the transition to the digital realm. All of the materials are developed in Hebrew and almost all of the circulation is done in Hebrew. Only three projects translate their posts into Arabic: the posts in the WhatsApp project are composed and circulated in English, Arabic and Hebrew. Olamon and Easy Going on Digital have one Arabic WhatsApp group each, where some posts are translated and circulated. Hence, despite the fact that 26.8% of high school students learn in Arabic speaking schools (Ministry of Education, Citation2020), with the exception of the EFL WhatsApp Project, only two groups out of almost one hundred WhatsApp and Telegram groups and Facebook pages operate in Arabic.

Dialogue restrictions in the WhatsApp groups

The projects use social media within existing educational structures and regularities. Consequently, in all initiatives, dialogue within the groups follows a similar pattern of participation as in traditional classrooms. In other words, it is restricted. Only admins can generate and circulate messages in closed groups where members cannot respond. According to the OlamOn developer, who established the norm, the dialogue is deliberately restricted because the initiative is not intended to stimulate discussion among ‘strangers’ who joined a shared interest group, but rather to integrate the messages in classroom WhatsApp groups teachers run.

Developers see their role as providing rich and diverse subject-related stories. Not all of them see their role in also providing instructional advice to teachers on how to use messages and WhatsApp communication (OlamOn, GMB, OlamOn Physics, WhatsApp Science). Some developers integrate pedagogical suggestions for teachers or add questions and learning instructions to students. Although rarely, OlamOn also composes posts in this manner, called OlamOn dilemmas. The message is then composed in a debate style and ends with instructions for resolution. In the first approach, the lack of teaching support leaves teachers alone to integrate WhatsApp messages into their own educational approach or simply share them with their students. However, 91.8% of respondents would like a pedagogical discussion on how to implement the initiatives in their instruction. As a result of the constraints on dialogue in the groups, the projects’ learning potential is restricted. The inability to share impressions and experiences in groups blocks creative and successful use of the posts. In addition, it blocks discussions about WhatsApp-related teaching challenges. Users are left behind WhatsApp ‘doors’. The same is true with the second approach in which WhatsApp is used to circulate teacher-proof learning materials with no opportunity for pedagogical discourse. This initiative was originally developed as a network for teachers to engage with content for pedagogical purposes. In reality, the materials do not enable teachers to generate pedagogical changes or innovation, and the project resembles traditional top-down curriculum cultures of production and circulation. Teachers are then expected to share the posts with their students in their own pre-existing groups or use them as a basic resource in their pedagogy. The circulation is structured so that posts will reach students through a top-down, one-way approach from their teachers. Students are not expected to share these posts. They are end-users, unlike social media circulation cultures.

Role of WhatsApp initiatives in classroom instruction

Teachers-users reported two reasons for engaging in social network-based pedagogy: the wish to diversify classroom pedagogy and expanding their education by reading the messages. Teachers used the project to expand their knowledge in their own discipline and other disciplines. While only a small minority use the projects only for this purpose, more than a third of the interviewees mentioned its importance to their general education. One teacher said it helped her learn and understand a discipline she was asked to teach without prior preparation.

Teachers often shared posts outside of their students’ groups. Teachers rarely shared posts with the families of students, but many shared relevant posts with their own families. Nearly one-third of teachers share posts with their peers. Some share with homeroom teachers to urge them to use the posts in their morning discussions with their homeroom students. Some share the posts with colleagues. This mode of sharing rarely prompts discussions. An interesting peer sharing was noticed among EFL teachers who tended to share in a top-down manner, from the discipline coordinator to all teachers. In this case, WhatsApp messages are the lesson plans. Thus, as already seen in the close guidance and supervision over the ‘WhatsApp Project’, EFL teachers have fully incorporated WhatsApp-based materials into an official curriculum.

Sharing messages with the students in the classroom WhatsApp groups is used by nearly two thirds of the teachers. Teachers tend to share posts with classroom groups rather than individual students. Only two teachers mentioned being selective with the addressees: they only share with ‘strong’ classrooms. The frequency of sharing varied greatly, from a few teachers who rarely share (a few times a year), to seldom sharing (once in three weeks), to the majority of teachers who select the most relevant posts and share most of them. Some teachers mentioned considerations about digital overload. As stated above, since EFL’s WhatsApp Projects works as a curriculum, sharing with students is mandatory. Asked whether circulation yields dialogue, only a few teachers reported frequent dialogues about shared content. Interestingly, only one teacher mentioned reducing sharing because of students’ lack of response.

Seventeen WhatsApp-based instructional practices were found. (The most common practices are in italics). The most common practice of WhatsApp initiatives was using it as part of classroom instruction. Owing to their availability, alignment with the curriculum, and the fact that the messages are posted in the morning, they have been widely used in classrooms, primarily as part of lesson plans and occasionally as the core of lessons. Other identified practices were as follows: Usage in a planned lesson, as an added ingredient of lesson plans: as a presentation, as a handout, as the main resource of a lesson, for text-based or text-inspired scientific discussion, including post-sharing posts and student-initiated discussions, as texts for Kahoot lessons and game-based learning, as a trigger for additional, related information seeking, as a trigger for discussing current events related to the discipline, as an exercise text to prepare for quizzes and exams, as a template for students to make their own posts, as an initiator for writing argumentative essays, as a corpus of data for students to categorise and label different kinds of geographical information, as part of the larger educational process, as an initiator for debate and discussion in plenary morning meetings and as printed decoration of classroom walls.

Discussion

To account for WhatsApp’s pedagogical use and rationale, the study provided an in-depth analysis of WhatsApp pedagogical uses in high schools. Classroom pedagogy was enriched by WhatsApp introduction in ways that include enhancing text-based or text-inspired discussions, supporting student-initiated discussions, connecting classroom learning to the outside world and providing didactic advice. The underlying rationale for these uses is rooted in the motivations: the need to leverage social media to engage learners; the desire to create new shared spaces for groups of teachers and students; and the goal of re-contextualising school knowledge by associating it with the culture of sharing.

The second research question asked how schools reconcile knowledge production and circulation within WhatsApp’s social network with their existing perceptions of knowledge and learning. The reconciliation of WhatsApp’s social network knowledge production with schools’ existing perceptions of knowledge and learning has been challenging. The study highlights a tension between WhatsApp’s potential to support novel ways of knowledge production and the tendency of schools to use WhatsApp in ways that reproduce traditional classroom structures and hierarchies. Specifically, it notes that WhatsApp initiatives impose old communicative assumptions and absolutist epistemologies on new media, control the sharing options of information, block the width of dialogue and allow conversational spaces to function only in a top-down unidirectional mode, suggesting that schools are working with contradictory knowledge and learning frameworks. WhatsApp is used to circulate ideas without harnessing the potential the new culture of circulation has for learning in terms of dialogicality, knowledge building and hierarchical opportunities. Far from the ‘I – Thou’ relations observed by Kizel (Citation2019) with the same tool but in a radically different setting, WhatsApp is simply used as a messaging system, domesticated to enhance classroom instruction. The potential of social media in changing learning and knowledge is not fully exploited.

WhatsApp-based pedagogy represents the ways new media pedagogies are re-making education, supplementing and bypassing textbooks and the traditional official curriculum (Ball & Grimaldi, Citation2021). The grassroots initiative of enthusiastic teacher-entrepreneurs has transformed ICT from school communication patterns and learning management systems into pedagogical use. In a manner not initially intended, WhatsApp messages are increasingly replacing traditional textbooks. While textbook writing was previously closely controlled by the Ministry of Education, neoliberal policies have enabled new media initiatives to thrive and open arenas for curricular development. Post by post, the meaning of textbook, resource, text and lesson plan has gained new meaning. The initiatives expand the school’s curricular boundaries to mobile environments. Formerly, the influence of teachers was limited to their own students, and their teaching was governed by curriculum standards. It was difficult to imagine a small group of teachers having daily access to nearly every high school teacher and student nationwide. But the power that lies in the hands of teachers-developers is unprecedented. Thus, social network-based pedagogies transform teachers into curriculum developers and policy makers on a national scale. Referring back to Van Den Beemt et al. (Citation2020) threefold differentiation of curricular levels, the study reveals an increasing liquidity of levels. Teachers-developers are now working at the intended and implemented level.

We have observed two key facets of school sharing: First, the digital practice of sharing is now also considered a pedagogical practice as teachers point to it as an educational act in its own right. As a second point, the actual uses of sharing in the projects have completely altered the principles of social media sharing. Speed, multiple layers, decentralisation and multi-directional distribution have transformed social media sharing and circulation into a crucial aspect of the meaning made in the production of virtual objects – messages and images alike. Those dimensions are added to traditional knowledge structures. We can also understand the projects as an attempt to anchor learning and instruction into the new socio-emotional framework of adolescents’ lives and the culture of sharing that social media has created, and as an attempt to re-contextualise school knowledge by associating it with the positive values enacted in the culture of sharing (John, Citation2016). The practice of sharing has been normalised both as an expectation and as an instructional approach. At the same time, sharing is being modified. In this process of using digital technologies for traditional purposes, the authoritative voice of the developers is maintained. Users are left to be only ‘readers’ or ‘commentators’ in their own group consistent with the epistemological hierarchy of knowers and consumers. The reproduction of the existing classroom structure in a way that preserves the traditional roles of the teacher and the students, albeit in a new space, provides an answer to the lure of technology with an application that uses current trends, but at the same time, modifies its use, offering a school-like, familiar version of technology. In this way, sharing empowers the confines of the classroom while preventing any attempts to transform it.

Finally, the following five research limitations should be considered: generalisability, applicability, comprehensiveness, influencing factors and longitudinal impact. They may also point to potential future research. Generalisability: While the research was conducted on a national scale, it still represents a case study of a single country. Therefore, the applicability of the findings to other countries may be limited and requires further research. Applicability: Focusing on high schools may limit the findings’ applicability to other educational levels. Comprehensiveness: Additional ethnographic data on WhatsApp implementation in classrooms is needed to reflect on real-world usage. Influencing factors: While studying technological implementation, the study did not account for other potential influencing factors, such as technology acceptance models. Longitudinal impact: The research did not examine the long-term impacts of WhatsApp for teaching and learning. Future research should focus on assessing sustained WhatsApp effects on both educational practices and student outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Orly Shapira, Sharon Hirsch and Tamar Amar for their contribution to the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benzi Slakmon

Benzi Slakmon is a learning scientist, pedagogy developer, and researcher at Tel Aviv University’s Department of Education Policy and Administration. A major focus of Slakmon’s research is the use of dialogue, deliberation and collaborative learning in educational settings. As part of his studies, he examines the dynamics of online platforms in educational settings with the objective of enhancing learning environments through innovative pedagogical methods.

Notes

1. The context section is a factual overview of the field of WhatsApp pedagogical uses, and it is therefore considered a finding in itself.

References

- Abualrob, M., & Nazzal, S. (2020). Using WhatsApp in teaching chemistry and biology to tenth graders. Contemporary Educational Technology, 11(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.30935/cet.641772

- Ahad, A. D., & Lim, S. M. A. (2014). Convenience or nuisance? The ‘WhatsApp’ dilemma. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 155, 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.278

- Aizenkot, D., & Kashy-Rosenbaum, G. (2021). Cyberbullying victimization in WhatsApp classmate groups among Israeli elementary, middle, and high school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15–16), NP8498–NP8519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519842860

- Amry, A. B. (2014). The impact of WhatsApp mobile social learning on the achievement and attitudes of female students compared with face to face learning in the classroom. European Scientific Journal, 10(22), 1857–7881.

- Asterhan, C. S., & Rosenberg, H. (2015). The promise, reality and dilemmas of secondary school teacher–student interactions in Facebook: The teacher perspective. Computers & Education, 85, 134–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.02.003

- Ball, S. J., & Grimaldi, E. (2021). Neoliberal education and the neoliberal digital classroom. Learning, Media and Technology.

- Bauer, M. W. (2000). Classical content analysis: A review. In M. W. Bauer, & G. Gaskell (eds.), Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound (pp. 131–151). Sage.

- Belk, R. (2007). Why not share rather than own? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 611(1), 126–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206298483

- Belk, R. (2014). You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1595–1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001

- Bradley, K., & Pargman, D. (2017). The sharing economy as the commons of the 21st century. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy & Society, 10(2), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx001

- Buber, M. (1970). I and thou (W. Kauffman, Trans.). Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Budianto, L., & Arifani, Y. (2021). Utilizing WhatsApp-driven learning during the COVID-19 outbreak: Efl users’ perceptions and practices. Call-Ej, 22(1), 264–281.

- Central Bureau Statistics Israel. (2019). Teaching staff in upper division schools, by teaching subjects and selected attributes. https://old.cbs.gov.il/shnaton69/st08_39x.pdf

- Cetinkaya, L. (2017). An educational technology tool that developed in the natural flow of life among students: WhatsApp. International Journal of Progressive Education, 13(2), 29–47.

- Costa-Sánchez, C., & Guerrero-Pico, M. (2020). What is WhatsApp for? Developing transmedia skills and informal learning strategies through the use of WhatsApp – A case study with teenagers from Spain. Social Media+ Society, 6(3), 2056305120942886. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120942886

- Facer, K., & Selwyn, N. (2021). Digital technology and the futures of education: Towards ‘non-stupid’optimism. UNESCO Futures of education report.

- Falzon, M. A. (Ed.). (2012). Multi-sited ethnography: Theory, praxis and locality in contemporary research. Ashgate Publishing.

- Farahian, M., & Parhamnia, F. (2021). Knowledge sharing through WhatsApp: Does it promote EFL teachers’ reflective practice? Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-12-2020-0456

- Gaskell, G. (2000). Individual and group interviewing. In M. W. Bauer & G. Gaskell (eds.), Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound (pp. 38–56). Sage.

- Gomez-Cruz, E., & Siles, I. (2021). Visual communication in practice: A texto-material approach to WhatsApp in Mexico City. International Journal of Communication (Online), 4546. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/17503/3579

- Harper, B. (2018). Technology and teacher–student interactions: A review of empirical research. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 50(3), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2018.1450690

- Hershkovitz, A., Elhija, M. A., & Zedan, D. (2019). Whatsapp is the message: Out-of-class communication, student-teacher relationship, and classroom environment. Journal of Information Technology Education, 18, 073–095. https://doi.org/10.28945/4183

- ITU. (2023, September 14). Mobile phone ownership. Facts and figures 2022 – Mobile phone ownership (itu.Int).

- John, N. A. (2016). The Age of sharing. Polity.

- Karapanos, E., Teixeira, P., & Gouveia, R. (2016). Need fulfillment and experiences on social media: A case on Facebook and WhatsApp. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 888–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.015

- Kizel, A. (2019). I–thou dialogical encounters in adolescents’ WhatsApp virtual communities. AI & SOCIETY, 34(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-017-0692-9

- Lampinen, A. (2015). Deceptively simple: Unpacking the notion of “sharing”. Social Media + Society, 1(1), 2056305115578135. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115578135

- Lave, J. (1997). The culture of acquisition and the practice of understanding. In D. I. Kirshner & J. A. Whitson (eds.), Situated Cognition: Social, Semiotic, and Psychological Perspectives, (pp. 63–82). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Marcus, G. E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523

- Matassi, M., Boczkowski, P. J., & Mitchelstein, E. (2019). Domesticating WhatsApp: Family, friends, work, and study in everyday communication. New Media & Society, 21(10), 2183–2200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819841890

- Ministry of Education. A broad perspective: Education in numbers. (mabat rachav: Misparim al hinuch). http://ic.education.gov.il/QvAJAXZfc/opendoc_pc.htm?document=Mabat_rachav.qvw&host=qvsprodlb&sheet=SH11&lang=en-US

- O’Hara, K. P., Massimi, M., Harper, R., Rubens, S., & Morris, J. (2014). Everyday dwelling with WhatsApp. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work & social computing (pp. 1131–1143).

- Papacharissi, Z. (2010). A private sphere: Democracy in a digital age. Polity Press..

- Quinn, K., & Powers, M. R. (2016). Revisiting the concept of ‘sharing’ for digital spaces: An analysis of reader comments to online news. Information Communication & Society, 19(4), 442–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1092565

- Rosenberg, H., & Asterhan, C. S. (2018). “WhatsApp, teacher?” – Student perspectives on teacher-student WhatsApp interactions in secondary schools. Journal of Information Technology Education Research, 17, 205–226. https://doi.org/10.28945/4081

- Schreurs, L., & Vandenbosch, L. (2021). Introducing the social media literacy (SMILE) model with the case of the positivity bias on social media. Journal of Children and Media, 15(3), 320–337.. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2020.1809481

- Schwarz, B., Rosenberg, H., & Asterhan, C. (Eds.). (2017). Breaking down barriers? Teachers, students and social networks. MOFET books. (Hebrew).

- Slakmon, B. (2017). Educational technology policy in Israel. Pedagogy Culture & Society, 25(1), 137–149.. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2016.1231709

- Statista. (2024). Most popular global mobile messenger apps. https://www.statista.com/statistics/258749/most-popular-global-mobile-messenger-apps/

- Turkle, S. (2015). Reclaiming conversation. Penguin Books.

- Van Den Beemt, A., Thurlings, M., & Willems, M. (2020). Towards an understanding of social media use in the classroom: A literature review. Technology, Pedagogy & Education, 29(1), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2019.1695657

Appendix 1.

Typical texts, formats and design of the projects

GMB. (translation: WHY?) The fact that an elephant lives longer than a mouse shouldn’t surprise us. Usually, in the animal world, larger species live longer than smaller ones. But, why is it that when it comes to canines, the lifespan of larger species is shorter than that of their smaller counterparts? Why does a gigantic Great Dane live no longer than 10 years while a chihuahua can live to be 18? The answer may be connected to the allocating of energy animals use for different purposes. Some canine races can be up to 50 times larger than others. The larger the dog, the more energy it has to devote to processes of ‘physiological maintenance’ which in turn leads to a higher wear and faster ageing process. As for a little good deed – there may be some senior citizens among us or people with medical pre-conditions, who are afraid to leave their homes at this time. This is the time to offer some help and to take their dogs out for a walk, regardless of its age or size.;)

Good Morning Biology … Man’s best friend … and all

Resource: https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/why-do-small-dogs-live-longer-than-big-dogs

Olam’On Physics Will one of the components used by future moon settlers be … urine? NASA, The United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration, intended to land people on the moon by the year 2024 and build a permanent base there that will also be used as a jumping board to reach Mars. One idea for building such a base is creating a mixture of the urine of the base settlers with the soil on the ground, in order to create a strong durable substance from which residential and other buildings can be constructed. This substance may also be used to build shelters for radioactive radiation during solar eruptions. These shelters are necessary as the moon does not have atmospheric layers to block the dangerous solar radiation. Urine might also be used to produce drinking water. This has already been done in the international space camp.

• Why do NASA engineers deal with developing solutions such as recycling urine to produce drinking water and building materials?

• How could the moon be used as a jumping board to reach Mars?

OlamOn. OlamOn News flash 27.8.20 Hurricane Laura. Within the next few hours hurricane ‘Laura’ is predicted to hit the Mexican Gulf coast.

A Hurricane is a tropical storm created over the Atlantic Ocean. The storm erupts in an area in which warm water evaporates quickly. The hurricane season lasts from June until November, but most storms occur in the months of August – October.

Hurricane Laura is expected to hit the coasts of Louisiana and Texas, and continue on to the mainland, after which it will subside and head North East. The storm is expected to be extremely powerful: category 5 (The highest level) on the Saffir Simpson scale.

Consequences: Hundreds of ml. of rain are expected in the area, and there is great fear of life threatening floods in wide areas. Winds are expected to reach a high of 250 km/h and cause trees and electric poles to collapse, while widely damaging infrastructure. Severe warnings have been published, and there is fear that the combination of the corona virus and the hurricane might make mass evacuation extremely difficult.

What’s Up Project

Dear Teachers,

Welcome to the WhatsUp project!

You are receiving this Whatsapp message because you are registered for the WhatsUp Project.

In this unit, there is a Quizlet activity introducing the difficult words that need reviewing before the students read the text. Students then read the text and answer the questions. They will get immediate feedback with their score. If you would like to get the score, ask your students to take a screenshot of it and send it to you. There are a few additional activities after the quiz.

Link to activity

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdWMUdUqwveFvenZgtG6wztR1_lO2-a45hQeD5VVDi3huuosQ/viewform

All the texts are on the Facebook page of the project and you are welcome to leave comments and share ideas under the relevant texts https://www.facebook.com/WhatsUp-Project-200004883696144/

History on the AM

The day Tel Aviv was bombed

Difficult battles had been taking place for almost a year in areas surrounding the Mediterranean Sea, but life in Tel Aviv, the first Hebrew city, went on as usual. At 4 PM on the sixth of the Hebrew month of Elul 5700 (9 September 1940), Tel Aviv too, was attacked as WW II reached its shores. Without warning, tens of Italian bomber groups that took off from Greek Islands, showered the neighbourhood of Neve Sha’anan and Trumpeldor St. The most horrid attack ever to strike Tel Aviv caused over one hundred casualties and two hundred and fifty wounded civilians. Many houses collapsed and electrical as well as water systems were damaged. Leaders from around the world expressed their condolences for those killed in the attack and to those injured, and donations and aid were sent from America to the ailing city. City council members took quick action, and so did local volunteers and the British government, which allowed for rescue and recovery. Many of the victims were buried in mass graves, and many residents of Tel Aviv moved to the city of Jerusalem until they could safely return. In the months that followed, the city continued to endure bombing (as did the city of Haifa whose refineries were a preferred target of the planes of the Axis powers). The bombing strengthened the need for an effective civil defence system. The first stage of the establishment of the home front command had begun.

———————————-

The bombing in Tel Aviv was the event that precipitated Jewish settlement and Israel’s efforts to create a civil defence system known today as the ‘Home Front Command’. What is the role and the importance of this authority today?