ABSTRACT

This paper uses the notion of material affordances to show that a focus on how people engage with materials helps understanding how organizations transit toward sustainability. Material affordances refer to the enablements and constraints afforded by materials to someone engaging with an environment for a particular purpose. Based on a qualitative study of a company's efforts at becoming circular, we show that material affordances are evolutive as organizational members shift focus from the development of products to the establishment of a circular business model. We also show that affordances are distributed across the company's circular ecosystem. Between what they enable and prevent, they invite humans to a dynamic engagement with materials that decenters human agencies to incorporate material agency in such efforts. A key contribution of the notion of material affordances is to put the relationships of humans and materials at the core of a transition toward circularity and sustainability.

Introduction

Echoing the massive and growing evidence of transgressions against the planet's boundaries (Steffen et al. Citation2015; Figueres et al. Citation2017) and accompanying the mounting conviction that climate change tops the list of global risks (World Economic Forum (WEF) Citation2020a), a growing number of political, economic, and opinion leaders in China (Winans, Kendall, and Deng Citation2017), Africa (World Economic Forum (WEF) Citation2020b), the European Union (EU) (Völker, Kovacic, and Strand Citation2020) and the USA (ReMade Institute Citation2021) have turned to the circular economy as a pathway to sustainability. This pathway intends to break with the current linear economic rationale of take-make-dispose (e.g. Esposito, Tse, and Soufani Citation2018), decouple economic growth from the use of natural resources (Lazarevic and Valve Citation2017), and enable a more balanced interplay between environmental and economic systems (Ghisellini, Cialani, and Ulgiati Citation2016).

The ability of a circular economy to deliver sustainability does not enjoy a consensus, though (Aguilar-Hernandez, Dias Rodrigues, and Tukker Citation2021). Critiques of the circular economy(Corvellec, Stowell, and Johansson Citationinpress) question the technocentric focus of end-of-pipe circular policies (Calisto Friant, Vermeulen, and Salomone Citation2021). They note that these policies focus on a relatively small fraction of materials in the global throughput (Åkerman, Humalisto, and Pitzen Citation2020), and with unclear system boundary limits (Korhonen, Honkasalo, and Seppälä Citation2018; Inigo and Blok Citation2019). They also bring forth that the wearing down (Parrique et al. Citation2019), contamination (Baxter, Aurisicchio, and Childs Citation2017), and dissipation in the environment (Cullen Citation2017) of materials set clear limits on how sustainable any circular economy can become. This is why it has been suggested to answer the question of whether ‘circular economy business models capture intended environmental value propositions’ with idiosyncratic case by case approaches of the business models and their stakeholders (Manninen et al. Citation2018, 413) rather than aggregations of different understandings of circularity.

Drawing on this suggestion of focusing on specific cases to assess the actual sustainability of circularity, we analyze the efforts by a small Swedish company producing signs to translate general circular principles (e.g. Stahel Citation2016) into actual circular practices to offer more sustainable products and services. To delve into the practicalities of these efforts, we draw on Gibson’s (Citation1986) concept of affordance and ask: how do organizational members engage with materials for the development of circular products, circular business models, and a circular economy as a means of promoting sustainability?

Employing Gibson’s (Citation1986) concept of affordance, we demonstrate how the company's work with the development of circular products, circular business models, and a circular economy is conditioned by material affordances. Material affordances refer to the enablements and constraints that materials afford someone engaging with it for some purpose. They are actionable properties between the physical world and a person or animal (Letiche and Lissack Citation2009); they also constitute a methodological formula to unfold the micro-sociality of material things (Harré Citation2002). Essentially relational through the assumption of mutual causality between perceiver and circumstances, affordances avoid a collapse into material determinism; rather they stress the entanglements of the material and social.

Material affordances emerge in our study as the backbone of business development toward circularity and sustainability. Investigating the concrete engagements (Corvellec, Babri, and Stål Citation2020) of organizational members with plastic, metal, glass, and wood, we find that material affordances are sequentially evolving as people shift focus from the development of products to the establishment of a circular business model and contribute to a circular economy, thereby learning more about materials and circularity. We also find that material affordances are dynamically distributed across what has been called the company's circular ecosystem (Konietzko, Bocken, and Hultink Citation2020; Boldrini and Antheaume Citation2021), in the sense that they are not the same for all stakeholders. Based on these findings, we suggest in our discussion that, between what material affordances enable and prevent, they invite humans to a dynamic engagement with materials that departs from human exceptionalism and anthropocentrism (Cielemęcka and Daigle Citation2019), decenters human agencies to incorporate material agency (Knappett and Malafouris Citation2008), and acknowledges the systematic entanglements (Hodder Citation2012) of material and human agencies in how organizations work with sustainability.

Our conclusions align with recent calls for a move to a relational view (Ergene, Banerjee, and Hoffman Citation2020; Walsh, Böhme, and Wamsler Citation2020) within the field of organizational sustainability. To understand organizational dynamics toward circularity and sustainability, we suggest a systematic focus on how people in organizations concretely engage with materials. Correspondingly, we suggest that an affordance-based approach to these engagements can contribute to underlie such a focus: theoretically, with an interpretative understanding of how organizations strive for circularity and sustainability; methodologically, with a focus on relationships among humans and materials rather than on the intrinsic qualities of materials; and practically, with guidelines for developers to work with and communicate around materials when developing products and business models for circularity and sustainability. This paper follows a conventional structure, with the next section introducing the key tenets of the notion of affordance.

Theory: on affordances

An evolving notion

The term ‘affordance’ was coined by J. J. Gibson (Citation1986) to introduce a noun that would encapsulate a relational understanding of perception in environmental psychology. For Gibson, an affordance referred to what the environment offers an animal, including a human – what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill. If a terrestrial surface is nearly horizontal, rather than slanted; nearly flat, rather than convex or concave; and sufficiently extended relative to the size of the animal; and if its substance is rigid relative to the weight of the animal, then the surface affords support (Gibson Citation1986, 127).

Gibson stressed that affordances are properties of the environment, but relative to the animal and unique for it. Arguing against a separation of the natural environment and the cultural environment, he stated:

[A]n affordance is neither an objective property nor a subjective property; or it is both if you like. An affordance cuts across the dichotomy of subjective-objective and helps us to understand its inadequacy. It is equally a fact of the environment and a fact of behavior. It is both physical and psychical, yet neither. An affordance points both ways, to the environment and to the observer. (Gibson Citation1986, 129)

Forty years after J. J. Gibson introduced his interactionist view of perception and action, the notion of affordance migrated outside its original field, ‘leaving behind much of the conceptual apparatus of Gibsonian psychology’ (Bloomfield, Latham, and Vurdubakis Citation2010, 416). Some scholars draw affordances toward ontology and turn them into properties of things. Turvey (Citation1992, 174), for example, defines an affordance as ‘an invariant combination of properties of a substance and surface.’ Others draw affordances toward epistemology and feature them as means for sentients to understand their world (Costall Citation1995). Yet others, such as (Greeno Citation1994), are keen at maintaining that the notion is inherently relational:

An affordance relates attributes of something in the environment to an interactive activity by an agent who has some ability, and an ability relates attributes of an agent to an interactive activity with something in the environment that has some affordance. (338)

An affordance is not only enabling, though; it constrains as well (Hutchby Citation2001). The idea that the ‘environment constrains what the animal can do’ was already present in Gibson's writing (Citation1977, 143); but the understanding of the constraint dimension of an affordance was further developed by Norman (Citation1999), among others. Norman suggested that constraints can be physical, as when one cannot move a cursor outside the screen; logical, as when users can deduce the actions required of them; or cultural, as when referring to learned conventions. Moreover, affordances differ in relation to the perceivers’ intentions: ‘[S]omeone wanting to walk along a path may consider a barricading affordance constraining, whereas someone wishing to prevent passage would consider it enabling,’ as Volkoff and Strong (Citation2013, 824) explain.

Add-ons to the original theory

In its migration from environmental psychology, Gibson's conceptual invention attracts many add-ons. For example, stressing the relational and non-determinist characters of affordance, Markus and Silver (Citation2008, 622) introduce the notion of functional affordance to depict ‘the possibilities for goal-oriented action afforded to specified user groups by technical objects.’ Anderson and Robey (Citation2017, 103) coin the notion of affordance potency defined as ‘the strength of the relationship between the abilities of the individual and the features of the system at the time of actualization, conditioned by the characteristics of the work environment’ to explain why affordances differ in their efficacy to users. And Nagy and Neff (Citation2015, 5) suggest that imagined affordances emerge ‘between users’ perceptions, attitudes, and expectations; between the materiality and functionality of technologies; and between the intentions and perceptions of designers.’

Another add-on is the distinction between first-order and second-order affordances (Van Leeuwen and Stins Citation1994). Second-order affordances are opened chronologically by the actualization of more directly perceived, first-order affordances. At its simplest level, a whiteboard with magnetic patient tags allows nurses to visualize the occupation of beds in an intensive care ward (a first-order affordance), allowing them to monitor bed allocation (a second-order affordance) (Beynon-Davies and Lederman Citation2017). Orders of affordances build one upon the other. As Leidner, Gonzalez, and Koch (Citation2018, 125) has noted, ‘second-order affordances cannot be actualized until the first order affordances have been actualized,’ which they exemplify with: ‘Interacting with peers is a first-order affordance that makes several other affordances possible, including building relationships, finding resources, and helping peers.’ van Leeuwen, Smitsman, and van Leeuwen’s (Citation1994) mention of third-order affordances evokes the possibility of chains of affordances. However, Zech et al. (Citation2017, 255) note, most works make use of affordance of the first-order ‘that is, affordances that are immediately related to an agent's skills,’ something that they attribute to ‘Gibson's characterization of affordances, in which the relationships between an agent's skills and associated action opportunities in the environment are a core underpinning’ and explain that there are relatively few works which perceive second-order affordances.

With a focus on the relationships of humans to materials and matter, our position is that of affordances as relational – situated between actors and the physical environments – and dynamic. Refusing to abide by an objective-versus-subjective mode of thinking, we see in the notion of affordance a way of expressing the relationships that emerge and become in the mutual agency (Burke and Wolf Citation2020) of human and material interaction in an organizational setting. An affordance stands for a potentiality that may or may not be exploited, and Davis and Chouinard (Citation2016, 244) suggest that one ask: ‘Affordance for whom and under which circumstances?’ Neither intrinsic to matter nor a product of imagination, affordances express how designers relate to the product qualities that materials afford, sales personnel relate to the customer's needs that different materials afford, and sustainability consultants relate to the environmental impact that materials afford.

Method: a case study of circular business model development

Research setting

Accus, the company we followed for this case study (Flyvbjerg Citation2011), designs, installs, and maintains signs – primarily outdoor signs with or without lighting, but also products for indoor environments, such as office directional signs. In its simplest form, a light sign is a solid frame with a source of light and a translucent or transparent front. Today's frames are usually aluminum, but they can be made of steel or any other solid material; sources of light used to be neon tubes, but are increasingly LED; the fronts are most often acrylic, but can be made of glass; and plastic foils are used to mask some areas but not others, so that a name or a brand lights up.

Only a small amount of the production is done internally, as most of it is conducted by Verbalux, a sign manufacturer with which Accus has long worked with. A key group of customers for Accus is the real estate companies that install illuminated signs with their name, or their tenants’ name, on their buildings – on office buildings or shopping malls, for example. Accus employs several designers to offer customized signs of a quality that harmonizes with the architecture and the environment, and it has received several awards for its contribution to the city's environment. Accus has a staff of 18 (2019) and gross sales revenue of EUR 2.8 million.

The CEO, who is a member of the family that owns the company, is committed to the notion of circularity as a means of sustainability, making the Accus case particularly relevant for our study purposes. Prior to our fieldwork having even commenced, the CEO had taken several initiatives to promote sustainability at Accus: installing solar panels at the headquarters office, supplying all-electric cars for the sales force with electricity from renewable sources, offering products with LED-based light sources, avoiding products containing PVC or phthalates, and joining the United Nations Global Compact.

Inspired by a growing interest in the circular economy, as raised by the European Commission (Citation2015/614) and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (Citation2015), the CEO applied for and received financial support from Vinnova, Sweden's innovation agency, in 2016 and again in 2017 for a project to develop circular signs – signs produced in the spirit of the circular economy. He made study visits to companies considered pioneers in circular business models, hired an industrial designer with a special expertise in sustainability, invited a waste management company to assess the recyclability of Accus’ signs, and retained a consultant specializing in transitions to circular business models. Accus’ designers were charged with imagining circular signs, and a task force elaborated on ways of leasing signs rather than selling them. Their goal was the reuse of signs, remaking them with parts of old signs, and recycling their components. About two years into their project, Accus launched Re:Sign, a brand that would signal its offering of circular signs and the company's orientation toward a circular business model. The company was initially more successful in gaining media interest than customers interested in their circular vision, but then saw its circular business take off in 2021 when it won a major local government procurement that explicitly asked for circular signs.

Qualitative data collection

Beginning in September 2016 and lasting for 36 months, the fieldwork was conducted by the second author, who was an embedded but independent co-applicant to Accus’ circular-signs project in the name of his university. This position gave him extended access to Accus and most of its partners, allowing the collection of multiple and sometimes divergent views on this project. He was also able to follow the project as it evolved from start to finish, allowing him to overcome the limitations of retrospective data collection (cf., Silverman Citation2011). This privileged access to a single case laid the groundwork for a longitudinal qualitative epistemology that fit our aim of researching the practical details of organizational members’ engagement with materials over time as they developed circular products and a circular business model.

Data collection rested mostly on observations, completed with interviews and document analysis, for the most part in Swedish. It encompassed well over 120 active contact hours with people working with the project.

Observations

The second author attended all 10 steering committee meetings of the circular-signs project and participated in two meetings with the project reference group, which comprised representatives of the main customers and partners in the project. He attended seven presentation meetings for employees and external stakeholders, including two presentations of a draft of a circular business model to the company's primary customers, and the official launch for VIP customers of Re:Sign. Moreover, he participated actively in six workshops with Accus’ designers in charge of introducing circular-signs proposals. He also participated in a series of five workshops with external consultants, representatives of the sales force, and Accus’ leadership, in their development of solutions for a circular business model. These workshops gave him the opportunity to follow the genesis of the company's circular business model, following the issues that people raised and addressed from one meeting to another, keeping track of abandoned solutions, asking questions about specific issues to enrich and validate his understanding of the company's project, but also communicating his views on it. Direct participation provided him with rich access to the engagement of Accus’ organizational members with the material practicalities of a circular product and business-model development. On all these occasions, informal chats were held about the further developments of circular-signs offerings to participants.

Meetings, presentations, and workshops, which were about materials, prototypes, recycling, circularity business model development, were documented through field notes and copies of PowerPoint presentations made at these meetings by other participants, inclusive of confidential documents with figures on gross sales revenues, margins, and strategic orientations.

Interviews

In addition to these observations, the second author conducted four formal interviews with the CEO of Accus, one with the CEO of Verbalux, and 12 interviews with groups of two or three Accus’ employees, speaking with nearly all of the case company's members about how they approached the development of circular products and a circular business model for the company. These interviews served to obtain clarifications about observations and technical queries, as well as occasions to test intermediary ideas about the projects with the people who participated in them. They lasted from one to two hours and were transcribed verbatim.

Reports

Based on the collected material, the second author wrote a report that described the activities undertaken during the first phase of the circular signs project (Author 2, 2018) that he presented at an information meeting for Accus and Verbalux organizational members, members of the steering committee, and members of the reference group. A second report (Authors 1–3, 2019) was delivered in October 2019 as per the contract with the funding agency.

Qualitative data analysis

Accus granted the first and third authors access to the material in October 2018. The fieldwork data were uploaded into an N-Vivo database and analysed collaboratively in four iterative (Silverman Citation2011; Swedberg Citation2014) rounds of coding and analysis: initial joint coding, organization of affordances, coding for whom and which context, and introduction of sub-categories.

Initial joint coding

First, we went through the data chronologically to identify what informants said about the affordances of different materials. We worked on a joint coding of the data, going through one another's coding in continuing discussions. This initial coding was theoretically informed by the symmetry of enablements and constraints in affordances underscored, for example, by Norman (Citation1999) and Hutchby (Citation2001). We identified, for example, the ability or inability of materials and signs to resist light, fatigue, dirt, and vandalism; or, when actors discussed the ways in which a material or a sign could or could not be reused, reshaped, reprocessed, recycled, or made part of a narrative on circularity or sustainability. As this coding demonstrated that metal, plastic, glass, and wood attracted most of the attention of Accus’ members, we decided to focus our attention on these four materials.

Organization of affordances

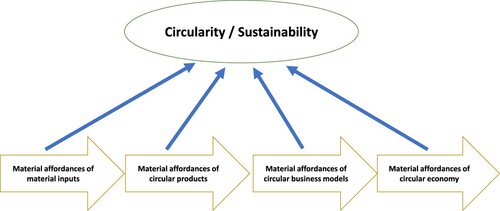

Second, drawing on the C. Van Leeuwen and Stins (Citation1994) and L. van Leeuwen, Smitsman, and van Leeuwen (Citation1994) observation that affordances can build onto each other in first-, second-, and even third-order affordances, we found that material affordances for circularity could be organized in sequences from first-order affordances of material inputs, to second-order affordances of circular products, to third-order affordances of circular business models, and finally to fourth-order affordances of the circular economy. The finding that the affordances for circularity attached by organizational members to metal, plastic, glass, and wood evolved sequentially as the company's project went from developing circular products to developing a circular business model is discussed as sequentially evolutive affordances in the analysis.

Coding for whom and in which context

Third, finding that the recommendation by (Davis and Chouinard Citation2016, 244) to ask ‘affordance for whom and under what circumstances?’ resonated with our purpose to put material affordances in their organizational context, we coded our data for who suggested which material affords what, in which context, for which purpose(s), and at which stage of the process. For example, we paid particular interest to occasions in which actors discussed how one can convince commercial partners to be interested in signs that present circular qualities. This new coding allowed us to identify differing views of the designers, salesforce, suppliers, customers, and members of the reference group about the respective affordances of metal, plastic, glass, and wood for the development of circular signs. Of interest to the architects but not necessarily to sales personnel, for instance, were material affordances for circularity that were critical for designers to imagine signs that could be easily assembled and disassembled. Knowing that different stakeholders held different views on the affordances of the various materials laid the groundwork for our finding that material affordances are dynamically distributed.

Introducing sub-categories

Finally, we introduced sub-categories for the first two orders of affordances: For first-order affordances for circularity of material inputs, we distinguished among Supply-ability, Constructability and maintainability, and Post-usability and recyclability, matching the simplified life-cycle perceptions of our respondents. And for second-order affordances of products, we introduced the subcategories of Design-ability, Recyclability, Remake-ability, and Reusability, matching the 3R perspective (recycle-remake-reuse) promoted by Accus’ industrial designer in order to understand the challenges of circularity. These subcategories were introduced to enable a systematic comparison of the material affordances of metal, plastic, glass, and wood. Introducing these subcategories also prompted us to proceed to a control search of our data for material affordances about which we had lesser data, for example, looking after statements about the supply-ability of wood or the post-usability of acrylic.

presents an overview of our empirical material: synthetic formulations of material affordances based on direct quotes, summaries of workshops, slideshow presentations, and observations (all of which were in Swedish). This presentation goes from first-order material affordances of material inputs, to second-order material affordances of circular products, third-order of circular business model, and fourth-order of the circular economy, to illustrate how affordances evolve from one order to another.

Table 1. Materials affordances for circularity.

Analysis: unfolding affordances

A close reading of what aluminum, acrylic, glass, and wood do and do not enable demonstrates that material affordances are situated and relational in at least two ways: they evolve and they differ. Material affordances evolve as a result of a shift in focus among organizational members from material inputs for circularity, to circular product, to a circular business model, to a circular economy. In short, they are sequentially evolutive. Material affordances differ because they are understood in changing contrast to one another; thus they are dynamically distributed.

Sequentially evolutive affordances

The sequential evolution of material affordances draws on the notion of orders of affordances (Van Leeuwen and Stins Citation1994; van Leeuwen, Smitsman, and van Leeuwen Citation1994; Beynon-Davies and Lederman Citation2017; Leidner, Gonzalez, and Koch Citation2018). Material affordances for circularity align in sequences, moving from first-order material affordances of material inputs (Zech et al. Citation2017), to second-order material affordances of circular products, to third-order material affordances of circular business models, and fourth-order material affordances of the circular economy. They build upon one another, while referring to circularity and sustainability (See ).

First-order material affordances for circularity

The first order pertains to the way physical and social qualities of material inputs enable or constrain an implementation of circular thinking (e.g. sourcing from secondary material market, enabling repair and take-back, increasing the durability of products, reducing footprint). As a sales manager explained:

‘The proportion of environmentally friendly material that we can offer in foils if extremely small. Its perhaps white, black and a couple of basic colors’ (Interview, January 17th, 2017) However, aluminum allows for sourcing and disposal organized around recyclability, for example; but it prevents a significant reduction of environmental impact due to the high impact at the extraction, production, and recycling stages. Acrylic affords replacement of the environmentally unfriendly material PVC; but it prevents longevity due to poor aging because of ultraviolet and weather sensitivity; its recyclability is also limited here in practice, as there is no demand for the small volumes of acrylic for recycling that Accus can produce. Likewise, the physical and social affordances of glass and wood condition what Accus’ organizational members deem possible to do or not to do when developing circular products, business models, and a circular economy.

Second-order material affordances

These material affordances pertain to what the material dimension of circular products affords organizational members for circularity. Accus’ members chose to engage with the development of circular signs via circular design and the three circular Rs of reusing a sign, remaking it with parts of an old sign, and recycling its components:

When we get the signs back we can now easily separate everything; electronics, metal, aluminum, and sell it. We couldn't do that before. Everything was welded and bolted together …

And glued …

We couldn't remove the light emitting diodes previously … but we can now. (Interview, October 4, 2018)

Third-order material affordances

These material affordances pertain to what the material dimension of a circular business model affords Accus’ organizational members for circularity. They developed third-order material affordances by embedding first- and second-order material affordances in an emerging business model inspired by a circular mode of thinking, a piecemeal work with practical choices to make about what it means to produce circular signs:

We will not be able to replace everything at once; we’ll have to work with improving bit by bit. We have found some ways that at least makes them better right now. At least there is potential to make signs circular on a component level and to use more recycled material. We allow ourselves to have different levels of circularity and we have figured out where the largest potential lies: when we update and replace components. And when we decide what should circulate faster and what we should try to circulate even slower (Accus CEO, Interview, October 4, 2018)

Fourth-order material affordances

These material affordances pertain to what the material dimension of the circular economy affords Accus’ organizational members for sustainability. Accus’ consistent commitment to circularity from inputs to production, maintenance, take-back, and discard serves to demonstrate the affordances of the circular economy for a reduced environmental and social impact of business activities.

The durable character of glass allows for the advocacy of long-term, standard solutions, as opposed to single-use customer-specific products, questioning the societal norm of single-use materials and advocating a more responsible use of materials. Wood allows for a means of sustainable transition and steps toward renewable material sourcing, as opposed to extraction-based sourcing. That material affordances also prevent things tending to be downplayed – that the absence of bio-sourced acrylic does not allow for the end of fossil-fuel dependency, for example, or that an increased circularity of signs does not allow for the questioning of norms and practices of the rapidly changing visual communication supports that lie behind the rapid turnover characterizing thee commercial signs that are currently available. Purchasing is here key to retain a sense of control. As the Accus CEO explained in an early interview:

How do we make our materials as green [environmentally friendly] as possible by sourcing them from the right places and using more recycled material; to actually move further back in the chain and audit their production processes, transports. We want to go as far upstream as possible. We want to use as much recycled material as possible and we want to control that. (Interview, November 29, 2016)

Dynamically distributed affordances

Material affordances also vary in relation to one another, as they are routinely contrasted to one another. For example, a designer explains that Accus ‘Is moving more and more from acrylic to MDF [Medium Density Fibreboard].’ (Interview, October 1, 2018). Physical, cultural, and logical affordances (Norman Citation1999) are dynamically distributed across the spectrum of materials that one can use to produce signs. For instance, aluminum is less expensive than steel, but it comes with a significant environmental impact with its extraction, production, and recycling stages. But some comparisons are ambiguous, as there is a lack of hard data on circular ability (Kristensen and Mosgaard Citation2020) and material affordances for sourcing, construction, use, take-back, reuse, and recycling may be unclear and contradictory. Moreover, material affordances evolve over time, in unanticipated ways (Burke and Wolf Citation2020), with some materials trumping others as actors, knowledge, or cultural acceptances change. Accus’ organizational members often experience the need for tradeoffs among environmental qualities on ambiguous grounds.

Affordances even vary in relation to who is considering them (Markus and Silver Citation2008). As (Gibson Citation1986) noted, just as surfaces are different for four-legged animals than for water bugs, material affordances differ depending on who or what is engaged in the context, specifically who is considering the affordance or for whom the affordance is considered (cf., Leidner, Gonzalez, and Koch Citation2018). For example, Verbalux CEO explained that developing circular signs may be a problem when it comes to selling but not to producing them:

In terms of the product sales, I can see difficulties. It is possible to find the right materials to produce for circularity. That's not where I see the problem; that's rather an opportunity … being able to choose the correct material … aluminum, plastic, acrylic, that's absolutely feasible for us. (Interview, January 19, 2017)

The circular ability of signs is permanently renegotiated across Accus’ ecosystem (Konietzko, Bocken, and Hultink Citation2020), as constellations of actors, materials, products, and contexts create new conditions for affordances. A designer explains:

As often and far as possible, we try to keep ourselves PVC-free. Unfortunately, all the suppliers don't really have the [adequate] supply but if we keep asking for it, they’ll eventually have to do something about it. (Interview, December 16, 2020)

The development of circular signs at Accus lands a dynamic distribution of material affordances for a circular economy across material inputs, products, and business models, but also across suppliers, partners, customers, preferences, and time. In particular, much effort was spent increasing the readiness of Accus’ ecosystems to accept standardization (see Parida et al. Citation2019). From the normalization of secondary material sourcing; to product design geared toward recyclability; to the development of standardized systems for reuse, rental, leasing, and take-back options, Accus’ Re:Sign system is an effort to navigate, but also an effort to organize the changing landscape of material affordances for recycling, reuse, longevity, reduced environmental impact, fossil-fuel independence, and material responsibility.

Discussion: dynamics of the material and the social

Drawing on the engagement of Accus’ organizational members with materials, we present in this final section two theoretical contributions of an affordance-based approach to understanding the role of materials for circularity and sustainability efforts: how material affordances are invitations to action which call for answers that decenter humans from the relationships of corporations and the natural environment.

Inviting to action

Between what they enable and what they constrain, the successive orders of material affordances invite organizational members to develop more circular and sustainable relationships with the natural environment. Affordances invite organizational members to reflect on what materials allow: how wood relates to plastics when developing circular products, whether all parts of a light sign need to circulate at the same speed when developing a circular business model, or how wood allows the development of a fossil free circular economy – and thereby bind together the physical with the logical and the cultural (Norman Citation1999). Each invitation is ‘a space of opportunity or frustration’ (Leonardi Citation2011, 163) for ‘human movement toward world and action’ (Letiche and Lissack Citation2009, 62) that provides ‘both physical and psychical’ (Gibson Citation1986, 129) limits to the company's work with sustainability.

The same as with affordances, these invitations are evolutive: They are not fixed in time but evolve as participants discover new possibilities offered by materials, learn about unknown technological solutions, change objectives, or see their partners modify their views. Engaging with materials is a process of learning and knowledge creation (Brix Citation2017), with the knowledge that emerges as actors critically reflect upon which materials, products, and business models afford circularity and sustainability. To meet these invitations, actors draw on the way past and possible futures of materials condition the development, distribution, and recirculation strategies of products and services; build on the ability of materials to inform new sustainability narratives about products, services, and business models (cf., Humphries and Smith Citation2014); and develop products and business models. At the core of these invitations is what materials afford.

These invitations are also distributed: Material affordances have different functions (Markus and Silver Citation2008) and potencies (Anderson and Robey Citation2017) as stakeholders have different intentions (Volkoff and Strong Citation2013), goals, experiences, and understandings of the potentials and limits of materials. To convince suppliers, architects, and real estate developers of the relevance and feasibility of Accus’ circular plans, the CEO needs to negotiate the contours of the circular-signs project, discussing such issues as the advantages of standard signs with reusable glass fronts, or the practical conditions of take-back in leasing arrangements. In spatial theory parlance, the invitations made by material affordances do not delimit a Euclidian space, but a topological one (Shields Citation2013), subjectively created (Quattrone and Hopper Citation2005) among stakeholders through their actual interactions. These invitations are fragile, contingent, and dynamic – susceptible to get out of sight at any moment, as solutions are discarded, objectives displaced, or economic imperatives set before environmental ones.

In addition, invitations call for answers, and material affordances induce organizational actors to engage with materials if these parties want to fulfill their plans.

Calling for answers

Accus’ journey (Milne, Kearins, and Walton Citation2006) toward circularity demonstrates the mattering of matter beyond a mere human interpretative practice. Rejecting views of affordance as ontological property of things (e.g. Turvey Citation1992) or epistemological means for sentients to make sense of their world (e.g. Costall Citation1995), a symmetrical understanding of affordances (e.g. Greeno Citation1994) stresses that material affordances are neither purely human nor purely material; they emerge from the interactions of humans and materials, granting an active role to both.

This symmetry of material affordances restates the tenet of sociomateriality studies (Orlikowski and Scott Citation2008) that ‘actors, objects, and intentions are entangled in a complex bundle of practice’ (Jarzabkowski and Pinch Citation2013, 580), rendering the social and the material mutually constitutive (Carlile et al. Citation2013). When designers ponder how users may react to wooden signs, or when business model developers wonder how to convince customers that a contract with a take-back clause is preferable to one without, these are but two examples of how organizational developments build on the entanglements of humans and material (Hodder Citation2012). As chains of orders of affordances (van Leeuwen, Smitsman, and van Leeuwen Citation1994; Zech et al. Citation2017) and the distribution of affordance across the organizational ecosystem show, the development of circular and sustainable products and business models rests on human-material relationships that emerge and develop or wane and disappear between the flux of innovation possibilities of what is enabled and the constraints of what is prevented.

More generally, a paradox of the Anthropocene is to bring forth the responsibility of man for this new geological era, but, at the same time, to demonstrate that materials in their entanglements with humans are neither passive nor always predictable (Latour Citation2018). Studies inspired by actor-network theory have empirically demonstrated the symmetric potential of humans and non-humans for agency, for example, when it comes to realizing visions for sustainability (Allen, Brigham, and Marshall Citation2018). A focus on affordances provides a theoretical ground to methodologically acknowledge the agency of materials in a wider span of organizational processes and business practices.

Material agencies lack the consciousness and intentionality that characterize human agencies (Knappett and Malafouris Citation2008). Yet, the Accus case shows, the dynamics of symmetric agencies manifested in chains of affordances of different orders, and spread over the organizational ecosystem, condition the dynamics of relationships of humans with humans, humans with materials, and materials with materials. A focus on material affordances makes clear how materials are able to redirect human intentions (Fatimah and Arora Citation2016), in the use or reuse of recycled materials, for example. And a focus on material affordances is a way of making this symmetrical agency graspable.

As shown in the analysis, the invitation made by material affordances to circular and environmental action is not given beforehand but rather is contingent upon the changing configurations of entanglements that emerge from what people sense that materials afford the development of circular and sustainable products and business models. Affordances, owing to their relational character, therefore, allow for a dynamic understanding of the symmetric role of humans and materials in organizational sustainability efforts, but also show how these evolving relationships take shape. Supportive of Bansal and Knox-Hayes’s (Citation2013) emphasis on materiality, we argue therefore that paying greater attention to material affordances make way for a theoretical, methodological and practical understanding of the interface between social and natural worlds (Jennings and Hoffman Citation2017), in a way that acknowledges the evolutive and distributive agency of both sides, thereby avoiding the biases of human exceptionalism and anthropocentrism (Cielemęcka and Daigle Citation2019). Neither materials nor humans are at the center of the journey toward circularity and sustainability, but their relationships are.

Acknowledging material agency implies a demotion of humans from their self-attributed centrality, in a transition to circularity and sustainability. Building on the literature on order of affordances (Van Leeuwen and Stins Citation1994; Beynon-Davies and Lederman Citation2017; Zech et al. Citation2017, 255; Leidner, Gonzalez, and Koch Citation2018, 125) we aim to contribute to the literature on organizational circularity and sustainability with the argument that one needs to take the relationships of human organizational actors with organizational material throughputs seriously if one is to appreciate circularity and sustainability efforts.

The environmental effects of businesses have their origin in the way humans engage with materials in organizational processes, not the least the waste that this engagement leaves behind to read and handle (Corvellec Citation2019). Because materials in the Anthropocene literally strike back, acknowledging a symmetry of human and material agencies – even if we speak of agencies of different kinds – entails inviting more modest, reflexive, and responsible engagements with materials, in sharp contrast to a non-reflexive anthropocentric teleology of extraction, use, and discards. Asking if a material, product, or business model affords circularity and sustainability is an invitation to an engagement with materials that goes beyond their practical potential and encompasses how they mediate the relationships of business to the natural environment. Humanity is being faced with the ultimate material challenge: sustainability. And to examine the affordances that materials offer to humans may be the best practical way to reach the heart of this challenge.

Concluding reflections

We suggest that a focus on affordances offers possibilities for researchers and practitioners to rethink the relationships of corporations to the physical world and participate in the ‘emergence of novel if still diffuse ways of conceptualizing and investigating material reality’ (Coole and Frost Citation2010, 2) attuned to the environmental challenges of the Anthropocene (Hoffman and Jennings Citation2015).

The Anthropocene makes the conventional understanding of individual and organizational actions as separated from both the social and the physical worlds untenable, and we therefore stress that it is the age of human and material entanglements (Gibson, Bird, and Fincher Citation2015). Facing unprecedented environmental threats (Ripple et al. Citation2019), corporations need to learn what to do with the broad range of materials that their industrial processes have released in the environment now that these materials have developed an ascendency on humans and nature that none seems to be able to handle.

Affordances cater to a relational view (Corvellec, Babri, and Stål, Citation2020; Ergene, Banerjee, and Hoffman Citation2020; Walsh, Böhme, and Wamsler Citation2020) that can serve as a theoretical acknowledgement of the entanglements of human and material agencies; a methodological approach to the relationships among humans and materials; and a practical guideline to new relationships between businesses and their physical environments (Corvellec and Stål Citation2017).

The decentering of humans (Cielemęcka and Daigle Citation2019) invites more modest, reflexive, and responsible engagements with materials, in sharp contrast to a non-reflexive anthropocentric teleology of extraction, use, and discard. Asking if a material, product, or business model affords sustainability invites us to engage with materials beyond their immediate practical potential and to recognize that materials and energy throughputs mediate organizational relationship to the natural environment. Queries for such ‘sustainable affordance’ open for ethical and political considerations about the social license of bringing materials onto markets (e.g. how material uses impact climate change). Thus, affordances open up avenues for discussing and analyzing aspects of intergenerational justice, and the decisive question of how to secure future welfare.

Affordances can therefore become political tools in the sense that featuring material affordances as positive or negative can orient the entanglements of materials and humans and therefore the impact of human activities on the environment. For example, a firm that markets products as free of conflict minerals reinforces the positive affordances of material substitution; whereas a legislative body that taxes CO2 emissions at extraction or post use reinforces the negative affordance of fossil fuels. Organizational, as well as political, actors have the possibility to play on constraints and enablements to govern material uses, and we suggest calling for a deliberate influencing of material affordances for a politics of material affordances: a systematic effort to orient what materials are able, and not able, to do. A politics of material affordances would make some affordances, and thus materials, more attractive, and others less. Not in a mechanical way, as the entanglements of humans with other humans and materials and of materials with other materials and humans are too contingent to be predictable, but in an aspirational way: working for a responsible politics of the material.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- European Commission. 2015/614. “Closing the loop – An EU action plan for the Circular Economy.” European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/strategy.htm.

- Aguilar-Hernandez, G. A., J. F. Dias Rodrigues, and A. Tukker. 2021. “Macroeconomic, Social and Environmental Impacts of a Circular Economy up to 2050: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies.” Journal of Cleaner Production 278: 123421.

- Åkerman, M., N. Humalisto, and S. Pitzen. 2020. “Material Politics in the Circular Economy: The Complicated Journey from Manure Surplus to Resource.” Geoforum 116: 73–80.

- Allen, S., M. Brigham, and J. Marshall. 2018. “Lost in Delegation? (Dis)organizing for Sustainability.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 34 (1): 29–39.

- Anderson, C., and D. Robey. 2017. “Affordance Potency: Explaining the Actualization of Technology Affordances.” Information and Organization 27 (2): 100–115.

- Bansal, P., and J. Knox-Hayes. 2013. “The Time and Space of Materiality in Organizations and the Natural Environment.” Organization & Environment 26 (1): 61–82.

- Baxter, W., M. Aurisicchio, and P. Childs. 2017. “Contaminated Interaction: Another Barrier to Circular Material Flows.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 21 (3): 507–516.

- Beynon-Davies, P., and R. Lederman. 2017. “Making Sense of Visual Management Through Affordance Theory.” Production Planning & Control 28 (2): 142–157.

- Bloomfield, B. P., Y. Latham, and T. Vurdubakis. 2010. “Bodies, Technologies and Action Possibilities: When Is an Affordance?” Sociology 44 (3): 415–433.

- Boldrini, J.-C., and N. Antheaume. 2021. “Designing and Testing a New Sustainable Business Model Tool for Multi-actor, Multi-level, Circular, and Collaborative Contexts.” Journal of Cleaner Production 309: 127209.

- Brix, J. 2017. “Exploring Knowledge Creation Processes as a Source of Organizational Learning: A Longitudinal Case Study of a Public Innovation Project.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 33 (2): 113–127.

- Burke, G. T., and C. Wolf. 2020. “The Process Affordances of Strategy Toolmaking when Addressing Wicked Problems.” Journal of Management Studies 58 (2): 359–388.

- Calisto Friant, M., W. J. V. Vermeulen, and R. Salomone. 2021. “Analysing European Union Circular Economy Policies: Words versus Actions.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 27: 337–353.

- Carlile, P. R., D. Nicolini, A. Langley, and H. Tsoukas. 2013. “How Matter Matters: Objects, Artifacts, and Materiality in Organization Studies: Introducing the Third Volume of ‘Perspective on Organization Studies’.” In How Matter Matters: Objects, Artifacts, and Materiality in Organization Studies, edited by Paul R. Carlile, Davide Nicolini, Ann Langley, and Haridimos Tsoukas, 1–15. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cielemęcka, O., and C. Daigle. 2019. “Posthuman Sustainability: An Ethos for Our Anthropocenic Future.” Theory, Culture & Society 36 (7-8): 0263276419873710.

- Coole, D. H., and S. Frost. 2010. “Introducing the New Materialisms.” In New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics, edited by Diana H. Coole, and Samantha Frost, 1–43. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Corvellec, H., and H. Stål. 2017. “Evidencing the waste effect of product-service systems (PSSs).” Journal of Cleaner Production 145: 14–24.

- Corvellec, H. 2019. “Waste as Scats: For an Organizational Engagement with Waste.” Organization 26 (2): 217–235.

- Corvellec, H., M. Babri, and H. Stål. 2020. “ Putting Circular Ambitions into Action: The Case of Accus, a Small Swedish Sign Company.” In Handbook of the Circular Economy, edited by Miguel Brandão, David Lazarevic, and Göran Finnveden, 266–277. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Corvellec, H., A. Stowell, and N. Johansson. inpress. “Critiques of the Circular Economy.” Journal of Industrial Ecology.

- Costall, A. 1995. “Socializing Affordances.” Theory & Psychology 5 (4): 467–481.

- Cullen, J. M. 2017. “Circular Economy: Theoretical Benchmark or Perpetual Motion Machine?” Journal of Industrial Ecology 21 (3): 483–486.

- Davis, J. L., and J. B. Chouinard. 2016. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36 (4): 241–248.

- Doganova, L., and M. Eyquem-Renault. 2009. “What Do Business Models Do? Innovation Devices in Technology Entrepreneurship.” Research Policy 38: 1559–1570.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2015. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Isle of Wight: Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

- Ergene, S., S. B. Banerjee, and A. Hoffman. 2020. “(Un)Sustainability and Organization Studies: Towards a Radical Engagement.” Organization Studies 42 (8): 1319–1335.

- Esposito, M., T. Tse, and K. Soufani. 2018. “Introducing a Circular Economy: New Thinking with New Managerial and Policy Implications.” California Management Review 60 (3): 5–19.

- Fatimah, Y. A., and S. Arora. 2016. “Nonhumans in the Practice of Development: Material Agency and Friction in a Small-Scale Energy Program in Indonesia.” Geoforum 70: 25–34.

- Figueres, C., H. J. Schellnhuber, G. Whiteman, J. Rockström, A. Hobley, and S. Rahmstorf. 2017. “Three Years to Safeguard Our Climate.” Nature News 546 (7660): 593–593.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2011. “Case Study.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by Norman K. Denzin, and Yvonna S. Lincoln, 301–316. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Ghisellini, P., C. Cialani, and S. Ulgiati. 2016. “A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a Balanced Interplay of Environmental and Economic Systems.” Journal of Cleaner Production 114: 11–32.

- Gibson, J. J. 1977. “The Theory of Affordances.” In Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing, edited by Robert Shaw, and John Bransford, 67–82. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gibson, J. J. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gibson, K., R. D. Bird, and R. Fincher, eds. 2015. Manisfesto for Living in the Anthropocene. Brooklyn, NY: Punctum Books.

- Greeno, J. G. 1994. “Gibson’s Affordances.” Psychological Review 101 (2): 336–342.

- Harré, R. 2002. “Material Objects in Social Worlds.” Theory, Culture & Society 19 (5-6): 23–33.

- Hodder, I. 2012. Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hoffman, A. J., and P. D. Jennings. 2015. “Institutional Theory and the Natural Environment: Research in (and on) the Anthropocene.” Organization & Environment 28 (1): 8–31.

- Humphries, C., and A. C. T. Smith. 2014. “Talking Objects: Towards a Post-Social Research Framework for Exploring Object Narratives.” Organization 21 (4): 477–494.

- Hutchby, I. 2001. “Technologies, Texts and Affordances.” Sociology 35 (2): 441–456.

- Inigo, E. A., and V. Blok. 2019. “Strengthening the Socio-Ethical Foundations of the Circular Economy: Lessons from Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Cleaner Production 233: 280–291.

- Jarzabkowski, P., and T. Pinch. 2013. “Sociomateriality Is ‘the New Black’: Accomplishing Repurposing, Reinscripting and Repairing in Context.” M@n@gement 16 (5): 579–592.

- Jennings, P. D., and A. J. Hoffman. 2017. “Institutional Theory and the Natural Environment: Building Research Through Tensions and Paradoxes.” In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, edited by Renate E. Meyer, Christine Oliver, Thomas B. Lawrence, and Royston Greenwood, 759–785. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Reference.

- Knappett, C. L., and L. Malafouris, eds. 2008. Material Agency: Towards a Non-anthropocentric Approach. New York: Springer US.

- Konietzko, J., N. Bocken, and E. J. Hultink. 2020. “Circular Ecosystem Innovation: An Initial Set of Principles.” Journal of Cleaner Production 253: 119942.

- Korhonen, J., A. Honkasalo, and J. Seppälä. 2018. “Circular Economy: The Concept and Its Limitations.” Ecological Economics 143: 37–46.

- Kristensen, H. S., and M. A. Mosgaard. 2020. “A Review of Micro Level Indicators for a Circular Economy – Moving Away from the Three Dimensions of Sustainability?” Journal of Cleaner Production 243: 118531.

- Latour, B. 2018. Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Translated by Catherine Porter. Cambridge: Polity.

- Lazarevic, D., and H. Valve. 2017. “Narrating Expectations for the Circular Economy: Towards a Common and Contested European Transition.” Energy Research & Social Science 31: 60–69.

- Leidner, D. E., E. Gonzalez, and H. Koch. 2018. “An Affordance Perspective of Enterprise Social Media and Organizational Socialization.” The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 27 (2): 117–138.

- Leonardi, P. M. 2011. “When Flexible Routines Meet Flexible Technologies: Affordance, Constraint, and the Imbrication of Human and Material Agencies.” MIS Quarterly 35 (1): 147–167.

- Letiche, H., and M. Lissack. 2009. “Making Room for Affordances.” Emergence: Complexity & Organization 11 (3): 61–72.

- Manninen, K., S. Koskela, R. Antikainen, N. Bocken, H. Dahlbo, and A. Aminoff. 2018. “Do Circular Economy Business Models Capture Intended Environmental Value Propositions?” Journal of Cleaner Production 171: 413–422.

- Markus, M. L., and M. S. Silver. 2008. “A Foundation for the Study of IT Effects: A New Look at DeSanctis and Poole’s Concepts of Structural Features and Spirit.” Journal of the Association for Information Systems 9 (10/11): 609–632.

- Milne, M. J., K. Kearins, and S. Walton. 2006. “Creating Adventures in Wonderland: The Journey Metaphor and Environmental Sustainability.” Organization 13 (6): 801–839.

- Nagy, P., and G. Neff. 2015. “Imagined Affordance: Reconstructing a Keyword for Communication Theory.” Social Media + Society 1 (2): 1–9.

- Norman, D. A. 1999. “Affordance, Conventions, and Design.” Interactions 6 (3): 38–43.

- Orlikowski, W. J., and S. V. Scott. 2008. “Sociomateriality: Challenging the Separation of Technology, Work and Organization.” The Academy of Management Annals 2 (1): 433–474.

- Parida, V., T. Burström, I. Visnjic, and J. Wincent. 2019. “Orchestrating Industrial Ecosystem in Circular Economy: A Two-Stage Transformation Model for Large Manufacturing Companies.” Journal of Business Research 101: 715–725.

- Parrique, T., J. Barth, F. Briens, C. Kerschner, K.-P. Alejo, K. Anna, and J. H. Spangenberg. 2019. Decoupling Debunked: Evidence and Arguments against Green Growth as a Sole Strategy for Sustainability. Brussels: European Environmental Bureau.

- Perey, R., S. Benn, R. Agarwal, and M. Edwards. 2018. “The Place of Waste: Changing Business Value for the Circular Economy.” Business Strategy and the Environment 27 (5): 631–642.

- Quattrone, P., and T. Hopper. 2005. “A ‘Time’ Space Odyssey’: Management Control Systems in Two Multinational Organisations.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (7-8): 735–764.

- ReMade Institute. 2021. “Sustainability, Recycling and the Concept of a Circular Economy Are All Topics Vitally Important in Today’s Changing World.” Accessed February 18. https://remadeinstitute.org/circular-economy.

- Ripple, W. J., C. Wolf, T. M. Newsome, P. Barnard, and W. R. Moomaw. 2019. “World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency.” BioScience 70 (1): 8–12.

- Shields, R. 2013. Spatial Questions: Cultural Topologies and Social Spatialisation. London: Sage.

- Silverman, D. 2011. Qualitative Research: Issues of Theory, Method and Practice. London: SAGE.

- Stahel, W. R. 2016. “Circular Economy – A New Relationship with Goods and Material Would Save Resources and Energy and Create Local Jobs.” Nature 431: 435–438.

- Steffen, W., K. Richardson, J. Rockström, S. E. Cornell, I. Fetzer, E. M. Bennett, R. Biggs, et al. 2015. “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet.” Science 347 (6223): 736–746.

- Swedberg, R. 2014. The Art of Social Theory. Princeton, NJ and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Turvey, M. T. 1992. “Affordances and Prospective Control: An Outline of the Ontology.” Ecological Psychology 4 (3): 173–187.

- van Leeuwen, L., A. Smitsman, and C. van Leeuwen. 1994. “Affordances, Perceptual Complexity, and the Development of Tool Use.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 20 (1): 174–191.

- Van Leeuwen, C., and J. Stins. 1994. “Perceivable Information or: The Happy Marriage Between Ecological Psychology and Gestalt.” Philosophical Psychology 7 (2): 267–285.

- Völker, T., Z. Kovacic, and R. Strand. 2020. “Indicator Development as a Site of Collective Imagination? The Case of European Commission Policies on the Circular Economy.” Culture and Organization 26 (2): 103–120.

- Volkoff, O., and D. Strong. 2013. “Critical Realism and Affordances: Theorizing IT-Associated Organizational Change Processes.” MIS Quarterly 3: 819–834.

- Walsh, Z., J. Böhme, and C. Wamsler. 2020. “Towards a Relational Paradigm in Sustainability Research, Practice, and Education.” Ambio.

- WEF (World Economic Forum). 2020a. The Global Risks Report 2020. Cologny/Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- WEF (World Economic Forum). 2020b. “Transforming African Economies to Sustainable and Circular Models.” Accessed February 18. https://www.weforum.org/our-impact/the-african-circular-economy-alliance-impact-story.

- Winans, K., A. Kendall, and H. Deng. 2017. “The History and Current Applications of the Circular Economy Concept.” Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 68: 825–833.

- Zech, P., S. Haller, S. R. Lakani, B. Ridge, E. Ugur, and J. Piater. 2017. “Computational Models of Affordance in Robotics: A Taxonomy and Systematic Classification.” Adaptive Behavior 25 (5): 235–271.