ABSTRACT

The contribution of the open-plan office to work and organisation has long been a matter of some debate. Aside from its economic advantages, it is argued that it provides an important opportunity for colleagues to share knowledge and help each other. It is recognised, however, that the presence and participation of others can undermine the ability of personnel to concentrate on individual tasks and subjects work to interruption. This paper seeks to show how these seemingly contradictory issues are matters participants themselves orient to on a daily basis. In particular, it explores the interactional practices in and through which participants address and, to some extent reconcile, these competing demands; initiating brief conversations while seeking to preserve the integrity of the ongoing tasks in which colleagues are engaged. This article focuses on participants progressively establishing momentary encounters that enable them to exchange information and resolve the inevitable difficulties colleagues face in organisations.

1. Introduction

The open-plan office has a long and interesting history and it is now a familiar feature of the corporate environment. The first purpose built open-plan office was created in the UK in 1729 for the East India Company, and from the mid-eighteenth century industries such as banking, rail, insurance, retail, petroleum and telegraphy began to implement this new form of office (Hamilton Citation2011). Based initially on the model of the factory, it was recognised that the open-plan office had significant advantages, allowing staff to be ‘housed’ within the same space and significantly lowering operating costs (Maher and von Hippel Citation2005). In these spaces, conversations were not encouraged. Indeed, it was believed that work would be more efficient without conversations, thereby ‘creating an introverted sense of the company as a family dedicated to the ‘sacrament of work’ (Kellaway Citation2013).

Over the last three decades or so, we have witnessed a revitalised commitment to the open-plan office, driven not just by the direct economic advantages of locating numerous staff within the same physical space, but by the growing interest in facilitating communication, team working and ‘informal’ collaboration amongst personnel to foster ‘knowledge sharing’ and innovation (Baldry Citation1999; Burkeman Citation2013). Developments such as Facebook’s ‘hacker cave’ (for 2800 engineers in Menlo Park), Google’s ‘landscraper’ in London, and Apple’s new corporate campus in Cupertino which promises ‘the ultimate crucible of collaboration (Nesta Citation2015 para. 4) are exemplary in this regard. Indeed, ideologically they align with the 1960s German movement Burolandschaft, meaning ‘office landscaping’ (Baldry and Barnes Citation2012). Here, open-plan offices were used to encourage people to talk to one another, moving away from the popular American structures of cubicles or cellular offices (Boutellier et al. Citation2008).

An important characteristic of the open-plan office across various sectors is that they draw together personnel who have differing roles and responsibilities but may be involved in the same overall projects; offering opportunities for communication and collaboration (see for example Bjerrum and Bødker Citation2003; Hutchinson and Quintas Citation2008; Koskinen, Pihlanto, and Vanharanta Citation2003; Boutellier et al. Citation2008). Here lies the crux of the issue touched on by various studies: on the one hand personnel have individual tasks, responsibilities and commitments, and, on the other, they rely upon the contributions of colleagues to undertake particular activities – to share information, secure advice, resolve problems, and the like. So, personnel will often rely on the contributions of others to manage their work, but are in a heightened risk of being interrupted as others also seek help or information.

This makes the open-plan office a perspicuous setting for the study of interruptions (Mark, Citation2015), with face-to-face interruptions imposing heightened interpersonal demands (Wajcman and Rose Citation2011). And yet we have gaps in our knowledge about how individuals manage and experience interruptions (Feldman and Greenway Citation2021). The majority of studies of the open-plan office have tended to consider accounts of, and attitudes to, interruptions. In contrast, this paper seeks to analyse the interactional organisation of moments that are routinely characterised as ‘interruptions’, in order to consider how personnel themselves produce, manage, and orient to, interruptions in their everyday work. In doing so, we are led to a rather distinctive characterisation of the ‘interruption’. Our observations and insights are based on the analysis of a substantial corpus of video-based field studies undertaken in a range of open-plan offices in the UK and elsewhere. The offices in question are drawn from different sectors but each involves a division of labour in which personnel rely upon the contributions of colleagues to undertake particular tasks and activities. We focus in particular on the ways in which participants establish and legitimise moments of collaboration.

2. Communication in the open-plan office

The open-plan office has generated substantial interest within organisation studies over many years (Oldham and Brass Citation1979; Sundstrom, Burt, and Kamp Citation1980; Crouch and Nimran Citation1989; Kim and de Dear Citation2013; McElroy and Morrow Citation2010; Baldry and Barnes Citation2012). These studies have tended to explore the relative advantages and disadvantages of open-plan office environments for productivity, innovation, employee satisfaction and well-being. Furthermore, studies have examined how these advantages and disadvantages are mediated by power, status, age and so forth (Zalesny and Farace Citation1987; Baldry and Barnes Citation2012; McElroy and Morrow Citation2010).

However, the debate struggles to find consensus in relation to matters of communication.

On the one hand, studies note the value of the open-plan office for encouraging informal contact and conversation between personnel to enhance knowledge-sharing, performance and innovation (Bjerrum and Bødker Citation2003; Hutchinson and Quintas Citation2008; Koskinen, Pihlanto, and Vanharanta Citation2003; Boutellier et al. Citation2008). On the other hand, research has drawn attention to the problems and difficulties faced by personnel in the open-plan office, most notably the threats of interruption and distraction. It is argued that these difficulties can significantly reduce productivity and employee well-being (Oldham and Brass Citation1979; Latham Citation1987; Crouch and Nimran Citation1989; Sundstrom, Herbert, and Brown Citation1982; Danielsson and Bodin Citation2009; De Croon et al. Citation2005; Kaarlela-Tuomaala et al. Citation2009; Danielsson et al. Citation2014). There is therefore a tension that pervades studies of the open-plan office and draws attention to the importance of enabling personnel to both reap the rewards from the presence and participation of colleagues while preserving some semblance of distance and privacy (Fayard and Weeks Citation2011).

These various studies of the open-plan office exhibit some puzzling differences with regard to communication and social interaction. For instance, in exploring patterns of communication in shared offices, Appel-Meulenbroek, de Vries, and Weggeman (Citation2017) found that the intervisibility and proximity of colleagues were most strongly associated with where knowledge was shared. And yet, a notable recent study measured the effect on interaction resulting from the transition of a large tech company to an open-office environment (Bernstein and Turban Citation2018) and found that face-to-face interaction decreased by over 70%, with collocated colleagues communicating more through digital means. Furthermore, the study claims that productivity (measured by metrics used in the firm’s performance management system) declined as email exchanges replaced face-to-face interactions. Thus, they demonstrate that the move to open offices does not necessarily generate a more vibrant work environment, as people retreat to digital media.

Interestingly, while these studies draw out broader patterns and trends, they do not explore actual episodes of interaction and communication in any qualitative depth. So, while the communicative tensions that arise are well-documented, accounts of specific moments in which people initiate face-to-face encounters in shared offices are rare. These are the practical matters that confront participants on a daily basis within the office, but there is little detailed qualitative analysis of specific episodes of conduct and communication that arise within the open-plan office and, in particular, the ways in which participants themselves initiate and manage conversations with others.

This draws us to reflect on another body of literature that bears upon these debates – that concerned with interruptions at work, where an individual unexpectedly suspends an ongoing work task (Puranik, Koopman, and Vough Citation2020). These studies consider work interruptions as ubiquitous in organisational life (Puranik, Koopman, and Vough Citation2020; Feldman and Greenway Citation2021), and most especially in open-plan office settings (Mark Citation2015). While studies often highlight a concern with interruptions due to digital technologies (González and Mark Citation2004; Stanko and Beckman Citation2015; Sonnentag et al. Citation2018), Wajcman and Rose’s (Citation2011) influential article revealed that face-to-face interruptions by colleagues were more common than technologically-mediated interruptions. Moreover, they described how workers could control their communication media to manage and access information at convenient moments, whereas with face-to-face interruptions ‘a worker usually has to react almost immediately … as it is generally considered rude to ignore a colleague and leave them waiting for a response’ (Wajcman and Rose Citation2011, 950).

So, moments when someone initiates an action to secure a colleague’s attention encouraging them to end or suspend a current activity are ubiquitous in office life, and, particularly relevant to open-plan work settings. However, recent reviews suggest that ‘our knowledge about how individuals experience work interruptions remains incomplete’ (Feldman and Greenway Citation2021). To attend to this concern, Feldman and Greenway (Citation2021, 72) examined the emotional experience of interruptions, explaining how positive interruption experiences can be differentiated from negative interruption experiences by three key factors: ‘time worthiness (i.e. whether or not an interruption is perceived as worthy of someone’s time), timing (i.e. whether an interruption is perceived as occurring at a ‘good’ vs. a ‘bad’ time), [and] duration (i.e. whether or not an interruption is perceived as taking a lot of vs. not much of someone’s time)’. These are insightful findings that we will return to later. But, like the bulk of the literature on the open-plan office, this study explored accounts of, and attitudes towards, interruptions, rather than examining the real-time production of those encounters. Indeed, in their review of 247 studies of work interruptions, Puranik, Koopman, and Vough (Citation2020, 832) argue that ‘despite the … involvement of other people, the quality of social interaction and the relational context of an interruption have been mostly ignored in prior work’. They attribute this to three reasons: (i) lab studies cannot recreate these complex dynamics, (ii) in field studies, the social interaction during an interruption is often ignored or is impossible to capture as a result of a frequency approach, and (iii) most interruption research focuses on performance and well-being outcomes while ignoring interpersonal outcomes.

This study, then, is rather different. It explores the interactional practices on which participants rely in initiating brief exchanges within the open-office environment and the delicacy with which they gain knowledge, support and advice from others. The issue with which the paper is concerned therefore is sometimes characterised as the problem of ‘interruption’ within office work but as we hope to show, the ways in which participants initiate these brief exchanges is designed to avoid interruption – to systematically gain the cooperation of colleagues in momentarily dealing with the problem or issue at hand.

3. Approach: a note on method

In addressing the ways in which personnel initiate collaboration in the open-plan office, this article draws on the burgeoning corpus of research informed by ethnomethodology (EM) and conversation analysis (CA) concerned with the organisation of social interaction in the workplace and, in particular, studies of multimodal or embodied conduct (see for example Drew and Heritage Citation1992; Heath and Luff Citation2000; Llewellyn and Hindmarsh Citation2010). Much of this work draws on the analysis of video recordings of everyday work and increasingly features within the field of organisation studies (Samra-Fredericks Citation2004; Hindmarsh and Pilnick Citation2007; Llewellyn Citation2015; Gylfe et al. Citation2016; LeBaron et al. Citation2016; Yamauchi and Hiramoto Citation2016; Hindmarsh and Llewellyn Citation2018; Oshima and Asmuß Citation2018; Oittinen Citation2018; Tuncer Citation2018; Tuncer and Licoppe Citation2018). And it forms part of a burgeoning, and broader, interest in the analysis of video data in management and organisation studies (see, for example, the special issue of Organizational Research Methods, edited by LeBaron, Jarzabkowski, and Pratt Citation2018).

This study uses video recordings to identify interactional practices fundamental to the initiation of talk at work. Therefore, the paper addresses the interplay of talk, bodily conduct and the use of material and digital objects and resources in the co-production of particular tasks and activities (see for instance Llewellyn and Hindmarsh Citation2010). The analysis primarily focuses on the sequential character of the participants’ conduct and the ways in which particular actions are sensitive to and render relevant actions by others. A concern with the sequential organisation of interaction drives the distinctiveness of the EM/CA approach, where actions are seen to be both context sensitive – attentive to the immediately prior context of action – and context renewing – establishing the new interactional context in which subsequent actions arise (Heritage Citation1984).

To work at this granular level, the transcription of talk (Jefferson Citation1984) and embodied conduct (Luff and Heath Citation2015) is a critical tool to unpack the resources that colleagues are using to coordinate conduct, and to explore the temporal and sequential relationships between different aspects of conduct. In line with the EM/CA approach which focuses on the multimodal interplay of verbal and non-verbal behaviour, extracts from the recordings of audio-visual data are transcribed using these standard CA orthographies (Jefferson Citation1984), in order to aid the analysis and identify patterns of conduct.

As such, this article is concerned with practice and adopts a ‘situational approach’ to practice (Nicolini Citation2017) by interrogating ‘interactional practices’ – that is, the patterned ways in which various interactional resources, both spoken and bodily, feature in organising activities with others. In keeping with this fine-grained qualitative approach, the study explores these interactional practices through the presentation and detailed discussion of a small number of examples. This is in line with what Reay et al. (Citation2019) call term the ‘long data excerpts approach’ to the presentation of qualitative data:

Rather than presenting a general theoretical narrative in which data serves to support the identification of theoretical concepts, the long data excerpts approach organises findings around raw data such as meaningful extracts of conversations, exchanges during meetings, or other forms of dialogue that can be analysed. By presenting data in an unfiltered way, authors attempt to respect the integrity of the interchange. (Reay et al. Citation2019, 201)

From the outset of the project, the authors recognised the importance of gathering data from a variety of settings – settings that involved different forms of task, role and responsibilities to enable us to begin to identify both common and more local reasons and resources on which participants draw in establishing collaboration in an open-office environment. The data were gathered in a number of companies in different countries, the lead author undertook many months of data collection and successfully secured access by sending emails, cold calling and presenting the research study to senior members of the organisations. All research sites provided very different services, where personnel were engaged in different sorts of task and relied upon rather different divisions of labour and responsibility. The common thread was that each of the organisations was committed to using an open-plan office to facilitate knowledge sharing. So, the offices housed a range of personnel responsible for different tasks and activities within the organisation and yet rely upon collaboration with, and in some cases, support from, colleagues. The research sites are presented in , which highlights the three settings used to illustrate the findings in this paper. The common language within all the offices is English, although occasionally in the offices in Abu Dhabi and Egypt, some individuals speak Arabic.

Table 1. Research sites.

Given the issues raised within research on the open-plan office, the authors were particularly interested in the ways in which participants, in the performance of their individual tasks, established, if only momentarily, conversations to discuss some matters of work with colleagues. The authors excluded non-work conversations to focus on aspects that relate to the organisational knowledge sharing, a theme that pervades the literature. A substantial corpus of these episodes was assembled, with a focus on their initiation, and progressively the authors identified some features of how personnel established conversations with colleagues. It is these interactional practices that form the focus of the analysis discussed here.

The authors curated a collection of 43 data extracts in which personnel-initiated conversations with colleagues, who in large part were engaged in distinct and somewhat unrelated activities. The talk that had arisen during a substantial proportion of the data corpus had been transcribed, and for the 43 extracts the authors undertook systematic transcription of the participants’ talk, visible on nonverbal conduct, and the use of tools and technologies. The analysis addressed both the concurrent and sequential characteristics of the participants’ action and activities; and focused in particular on how participants progressively and contingently aligned their actions to co-produce brief episodes of conversation.

4. Analysis

In the next few sections, we discuss a series of instances that could easily be characterised as ‘interruptions’, moments when an individual initiates a conversation with a colleague who is engaged in an unrelated activity. The ‘unrelated activities’ that feature in these extracts include various tasks on the computer, as well as conversations with other people. Through the consideration of this range of instances, we build a picture of the patterned ways in which people manage entry into a new work conversation, while their colleagues manage (temporary) disengagement from their tasks. The first four instances present relatively seamless – although richly delicate – initiations, offering insights on the work of each party in different situations. But we end this section with a very rare deviant case, one where the interruption is, to a certain extent, rejected. We argue that this final case complements the rest, by highlighting the significance of the order that we find in the vast majority of cases. This speaks to the expectations that personnel have when orienting to interruptions.

4.1. Stepwise movement into engagement

It is long been recognised that momentary conversations and brief exchanges are a pervasive feature of work within many open-plan offices and yet personnel often remark on how it can be difficult to work uninterrupted. In this data corpus encompassing a range of physical and organisational environments, it is found that personnel are highly sensitive to the concurrent obligations and responsibilities of their colleagues and it is rare to find instances in which they demand the attention of others. Indeed, even though they might need another’s help or assistance, participants show a remarkable sensitivity to the concurrent involvement of others and the ways in which they are engaged in other tasks. As an example, consider the following extract drawn from an estate agents office.

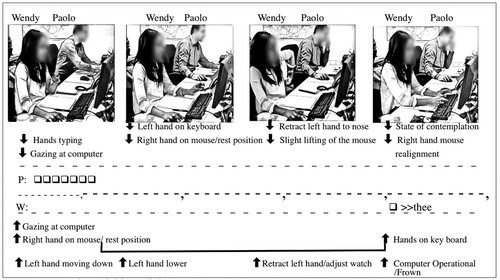

WendyFootnote1 and Paolo are sitting alongside each other working on different briefs. Paolo specialises in sales; he is more senior and he is preparing details for another property. Wendy deals with lettings and is relatively new to the office. Wendy recently finished speaking on the phone with a client (the phone call lasted approximately 10 minutes). The phone call relates to a property where Wendy will be required to change the format of the contract. After putting the phone down, she returns to working on the contract on her computer. Moments later she asks Paolo how to change an 18-month contract to a 12-month contract.

Wendy’s query would appear to interrupt the activity in which Paolo is engaged and following a brief exchange with Wendy he returns to the document on which he is working and continues with the task at hand. On closer inspection, it is found that the placement of Wendy’s query is oriented to the activity in which Paolo is engaged and is designed to minimise the interruption it might otherwise have cause.

Firstly, the specific placement of the query is sensitive to the emerging conduct of Paolo. Even though Wendy recognises the need to change the contract during the phone call she does not attempt to raise the question with Paolo either during the call or immediately after she replaces the receiver. She returns to her computer. Moments later, Paolo stops typing, leans back, withdraws his hands from the keyboard and gently rests his head on his hand (as if in contemplation). Even though his right hand remains on the mouse and he continues to look at the screen, Paolo’s reorientation suggests a temporary pause or break in the activity in which he is engaged ().

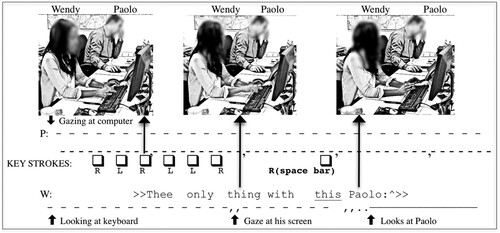

Secondly, Wendy does not immediately produce the query (‘if they had an eighteen month property tenancy’), but foreshadows the question with a prefatory utterance that refers back to an earlier conversation and minimises the problem with which she needs assistance ‘the only thing with this Paolo is if they had’. So, Wendy stresses the limited scope of the upcoming query; only relating to this one aspect of the case. Her conduct and her enquiry display that she is dealing with this issue right now and needs assistance at this moment.

Thirdly, the reference to ‘this’ not only suggests it is a matter with which Paolo has some familiarity, but also one that can be seen in the workspace. As Wendy utters ‘this’ she taps her space bar with a flourish, marking a break in her typing as she moves into this momentary discussion with Paolo (see ). Paolo glances towards Wendy’s screen and shows her how to alter the contract; the matter and this brief episode of interaction is over in a few seconds.

In seeking the assistance of a colleague, therefore, participants may go to some trouble not only to avoid interrupting the activity but to minimise the demands they place on the other. In the case at hand, Wendy is sensitive to and monitors the activity in which Paolo is engaged and seeks to position and articulate her query with regard to a potential juncture or break in the task in which he is engaged. The query is contingently positioned with regard to the emerging actions of her co-participant. She only issues the actual question when Paolo displays his willingness to temporarily suspend the activity in which he is engaged to resolve the problem at hand. In other words, even though Wendy positions the onset of her utterance at a potential break or boundary within the current activity of her colleague, she does not assume that it would be appropriate to ‘bluntly’ ask the question, but rather delays the production of the query until she has secured Paolo’s cooperation. Providing the background prior to issuing the question, coupled with the various pauses and perturbations in its delivery, are interactional practices in and through which the participants can progressively and contingently establish a moment of collaboration.

The fragment points to a further issue that is critical to many conversations that arise within the open-office environment, namely the matter of warrant or legitimacy. The back-referencing found in the way in which Wendy foreshadows the query, not only provides a framework to make sense of the question and progressively establish a mutual orientation, but also provides a warrant or justification for the query whilst Paolo is dealing with other matters. It is clearly a matter that Wendy and Paolo have already discussed, a matter that she has been tasked with dealing with, and yet a matter that, given her relative lack of experience, she may not be able to deal with alone. In seeking to initiate a conversation with her colleague, Wendy is not simply sensitive to his current commitments and activity, but reveals from its outset, that the matter at hand is something that will have to resolved and is a necessary feature of producing the contract. Paolo’s assistance is a necessary feature of the work at hand and seeking his assistance is justified and heard to be justified in those terms.

4.2. Catching a colleague on the move

It has long been argued that the proximity of personnel within the open-plan office, their ability to see each other and move freely within the environment can contribute to the exchange of information, ideas and knowledge (see for example Whittaker, Frohlich, and Daly-Jones Citation1994; Appel-Meulenbroek, de Vries, and Weggeman Citation2017). The data analysed in this study suggest that the ways in which people pass through the office can serve to occasion conversations about work and related matters. These ‘passing encounters’ pose some interesting issues for how participants balance the need to initiate talk with respecting the demands and the integrity of activities in which others may be engaged. To borrow a phrase used by E.C. Hughes (Citation1958) colleagues have to provide others with the ‘elbow room’ to undertake their own tasks and activities. A recurrent issue in this regard, is how individuals occasion a conversation when colleagues are talking with each other while they do not want the lose the opportunity to engage with one of them.

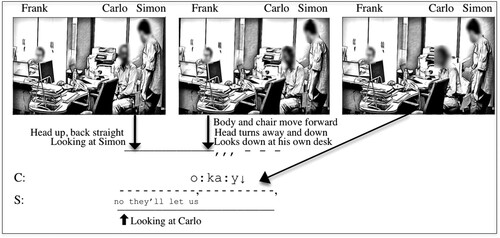

Consider the following extract drawn from a renewable energy firm. Simon, the lead project engineer, has crossed the office and is talking with Carlo, an installation manager. Frank, a project development manager, is sitting nearby. Immediately following Carlo’s ‘okay’ (line 2, Extract 2), Frank starts to ask Simon about a trip they plan to Razeeza. This question is unrelated to the topic discussed by Simon and Carlo, and yet there is less than a quarter of a second between Carlo’s final utterance and Frank’s initiating utterance.

Frank’s question is systematically designed to secure Simon’s engagement while not interrupting or unsettling the conversation between his colleagues. Indeed, until they have finished speaking, they are largely unaware that Frank is preparing to initiate conversation with Simon. Frank preserves the integrity of their encounter whilst preparing to exploit the opportunity afforded by one of his colleagues being close by.

There are various features of his colleagues’ talk and bodily comportment that enable Frank to identify when it might be opportune to initiate conversation. Firstly, Simon begins to summarise the conversation by remarking that the possible problem should not pose difficulties ‘no they’ll let us’ (on line 3). Secondly, Carlo’s ‘okay’ (on line 4), coupled with its falling intonation and no immediate response from Simon implicates the end of the conversation. Thirdly, Simon pivots his body and begins to progressively turn away from Carlo during ‘no they’ll let us’ (on line 3). Similarly, when Carlo utters the word ‘okay’ (on line 4), he moves his head down and away from Simon and reorients his chair towards his computer screen. These resources enable Frank to anticipate the upcoming close of the conversation and position his utterance to co-occur with its end ().

Anticipating just when it is appropriate and reasonable to initiate a conversation with a colleague, balancing the need to talk without interrupting or the losing the opportunity, is by no means unproblematic. Frank has already attempted to initiate conversation with Simon a little earlier in the conversation but in realising his colleagues’ conversation was not drawing to conclusion abandoned the attempt. It is illustrated in . There are a number of aspects of interaction that suggest that the conversation is drawing to an end, most explicitly, Carlo pushing his chair backwards and turning away from Simon. At that moment, Frank turns towards Simon, lifts his index finger and opens his mouth as if he is about to speak (see image ii in ). He quickly desists as Carlo glances back at Simon and continues the conversation.

It is worth adding that, in this case, the design of the initiating utterance names the principal recipient at the outset, seeking to secure his immediate alignment to enable the query to be voiced. He awaits Simon’s alignment before continuing. There is a deference in the way in which the query is both positioned and voiced that displays a remarkable sensitivity to placing demands on Simon. It nicely reflects and preserves an asymmetry in their respective organisational responsibilities.

There is a delicacy that arises in the ways in which personnel attempt to piggyback conversations on the passing encounters of colleagues. On the one hand, it provides a potential opportunity to exploit the presence and passing engagement of others, but on the other hand, an employee may not want to be seen exploiting the apparent ‘availability’ of another. Frank does indeed persist in seeking to talk to Simon, and one suspects that Simon may well be aware of his colleague’s previous attempt, but he does not design the closing of his conversation with Carlo to prefigure turning to and initiating talk with Frank. This may, in part, account for the positioning and design of Frank’s initiating utterance. The attempts to secure the attention of the other are not only sensitive to the emerging and contingent production of the conversation as it progresses towards potential closure, but they are designed to be unobtrusive; enabling engagement but not demanding attention from any of the participants. In other words, the initiation is sensitive to preserving the integrity if the current engagement and if necessary, to enable the participants to disregard, for the time being, the presence and conduct of a colleague. Frank’s attempt to initiate conversation may well be noticed but it is not ‘noticeable’ – it does not intrude on or disrupt the activity that, in this case, it is designed to follow.

Successive conversations between personnel in the office might suggest that individuals are open and available for talk with others at any moment within the course of their daily work. In our data, this is not the case. There is an orientation to legitimising encounters even though one party may be about to finish talking with another and a delicacy in the ways in which a new encounter is initiated. Engaging the other is warranted by virtue of resolving a potential matter, a matter, that at least in the way the topic begins, would appear to be resolvable quickly with dispatch. There is again an implied brevity to the matter one party raises with the other. Moreover, the extract exposes the ways in which the co-participant is sensitive to interruption and sensitive to avoid the others’ conversation, systematically monitoring the emerging course of talk and interaction, in attempt to secure the opportunity to initiate engagement whilst preserving the integrity of the activity in which his colleagues are engaged.

4.3. Temporarily suspending an individual task or activity

Notwithstanding the delicacy with which personnel may seek to initiate talk with colleagues, beginning a conversation will frequently demand that some current task or activity is temporarily delayed or suspended. In many cases, the suspension of a current task is prefigured by finishing some element of the task – sending an e-mail, finalising a column in Excel or simply completing a sentence. The initiation of these brief encounters, therefore, is an emerging process, it emerges progressively in and through the emerging action and interaction of both participants.

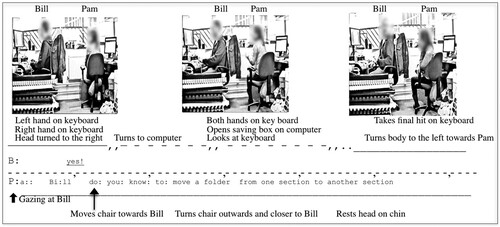

The following example is drawn from a university administrative office. Pam and Bill are in charge of postgraduate students. Pam is new to the office and Bill is providing her with informal support and guidance. Bill has just returned to his desk after a short break away from the office. A minute or so after his return, Pam utters ‘ar Bill’, Bill responds with ‘yes!’ and Pam begins to frame her query.

Rather like the previous example, the initiation requests Bill’s attention but does not provide or project a sense of the issue that is about to be raised; indeed, Bill’s response provides a relatively open opportunity to Pam to raise whatever query she has in mind. It is interesting to note, however, that the query is raised just as Bill returns to his desk. The placement of the initiation turn is interesting in as much as it appears to seek to secure Bill’s attention before he re-engages fully in his previous activity. His response is interesting in this regard.

He immediately replies to the request but does not immediately abandon the activity which he has just begun. As Pam continues with ‘do you … ’ (on line 3), Bill remains visually oriented towards his screen, but slightly rotates his swivel chair towards Pam, a movement that foreshadows realigning towards Pam moments later. He moves to open a ‘save’ window on his computer, and towards the end of the query, hits the return key with some force three times and turns his chair towards Pam. By the completion of the query, Bill is oriented towards Pam, leaning back in his chair.

Therefore, there is a process through which the participants progressively establish mutual orientation and commitment to addressing the issues that Pam has posed. Bill does not solely reply to the initiation verbally, but also through the ways in which he orients to Pam, while simultaneously undertaking specific activities on the computer, he projects his commitment while working to disengage from the activity at hand. It enables Pam, not only to presuppose Bill will indeed address her query, but to provide further background to the query as Bill undertakes a series of actions to suspend his current activity. Indeed, one suspects the question itself is delayed, or rather the background is progressively developed, to just the moment where Pam anticipates Bill is available to reply and discuss the question ().

Suspending one and beginning another activity, is systematically and collaboratively accomplished. As Pam draws closer to Bill, he displays various ways in which he is working to suspend his current task and how he is physically moving into more focused interaction with Pam. Bill’s orientation to the computer, his transformation in his material engagement with the keyboard and his use of the swivel chair are critical to the ways in which he shows a progressive re-alignment to Pam.

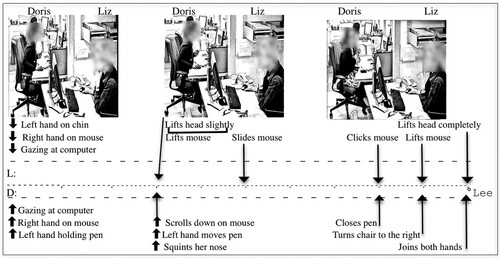

To explore these issues in a little more detail, it is worth considering a further example again drawn from an administrative office. Liz is the senior manager and Doris a newly appointed administrative assistant.

For 20 minutes or so, all of the personnel in the office have been working in silence and, indeed, for the past hour Doris and Liz have not talked to each other at all. Doris then starts to ask Liz about whether there is additional programme information other than in the handbook that she can send to a prospective student.

Doris, positions her initiating utterance, with regard to an apparent break or juncture in Liz’s activity. Liz has been active with her mouse and then lifts and makes an audible clicking noise and at that moment Doris loudly closes the top of her pen turns her body towards Liz (see image iii, ). Sensitive to Doris’ change of orientation, Liz once again lifts her mouse and raises her head from the resting position.

The design of the initiating utterance provides the opportunity to the speaker to progressively unfold the background to the problem with which she is faced, while simultaneously enabling the recipient, in this case Liz to progressively draw her activity to a temporary close. Indeed, calling out her name in this way, and securing an initial response from Liz (‘hmh’) provides Doris with the resources with which to raise some unspecified matter, but displays, at this moment, the recipient’s constrained availability. In delivering an expanded history to the problem, Doris not only provides Liz with the resources with which to disambiguate the query but enables Liz to progressively realign her involvement from the task in which she is engaged in. It also serves to provide grounds, warrant, for what could be considered a potential interruption, dealing with a problem that is not Doris’s personal problem but rather a difficulty faced by a student.

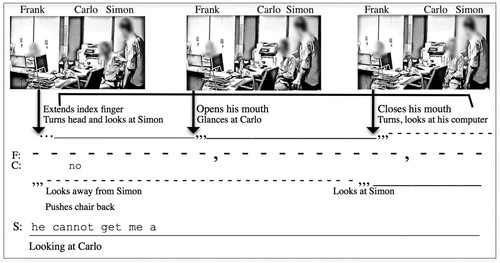

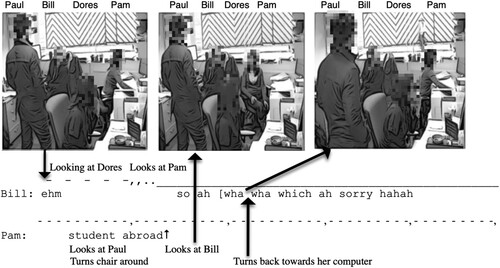

4.4. A contrasting case

Throughout our data corpus, we find a remarkable sensitivity amongst personnel to the current commitments and responsibilities of others and to preserving each other’s ability to undertake particular tasks and activities uninterrupted. It is rare to find examples of personnel initiating, unilaterally, an encounter with others, and the frequent, brief exchanges that arise are routinely foreshadowed by a stepwise progression into interaction. In this regard, we undertook a wide-ranging review of the data corpus to find instances of personnel unilaterally initiating an encounter with a colleague and participants treating the initiation as potentially some form of interruption. The following example is rather different from the material so far in as much as it involves a colleague seeking to proffer help uninvited but it provides it sense of how a unilateral intervention is treated within the open-plan office. We join the action as two colleagues, Bill and Doris, are dealing with a student, Paul, and are seeking to clarify which programme he is attending. Pam is working on a document unrelated to the problem with which her colleagues are dealing.

Pam volunteers the information ‘study abroad’ – information that is indeed correct. Her contribution is uninvited and receives no immediate response from either her colleagues or the student. And as Bill ignores the contribution and continues to speak to the student (line 7), Pam immediately turns back to her computer. Bill hesitates. A moment later he abandons the turn in which he is engaged and apologises to Pam. Bill seeks to transform his apparent faux pas into a joke with Pam accepting his apology. However well-motivated, Pam’s unilateral contribution to her colleagues’ conversation is treated as problematic, as inappropriate and unwarranted, an intervention, even interruption of the activity that is neither invited nor facilitated. Its transformation into a joke serves to quickly ameliorate Pam’s mistake and Bill’s potential rudeness and avoid the social import of this seemingly innocuous problem ().

It is interesting to note that even in cases where colleagues volunteer, rather than seek, assistance or help, they typically, and progressively, establish the cooperation of the co-participant(s) prior to issuing a contribution to the activity at hand. The delicate, stepwise process through which they secure the commitment of a colleague to talk, if only briefly, displays a respect for the activity in which the other is engaged and at least in some cases, their responsibility to undertake particular activities or tasks independently of others – a form of both respecting and preserving the division of labour within the fine details of the workplace interaction.

5. Discussion

It has long been recognised that aside from its economic advantage, the open-plan office provides important opportunities to enable personnel to communicate with each other with ease and to facilitate the exchange of information, ideas and knowledge. However, a range of studies demonstrate that the open-plan office can subject staff to unnecessary interruption and undermine their ability to sustain attention and undertake their particular tasks and responsibilities. Furthermore, as Puranik, Koopman, and Vough (Citation2020) suggest, the nature of these interruptions and the ways in which they arise in and through interaction remain largely unaddressed. This paper has revealed how participants themselves orient to, and seek to reconcile, the seeming contradictory demands to which they are subject in working within an open-plan office. A key contribution of this paper, then, is to demonstrate that the tension between knowledge sharing and interruption that is evident in contrasting accounts in the literature is also a participants’ concern that is concretely reflected in the interactional practices used to initiate encounters with other in the open-plan office.

Those interactional practices can be seen to attempt to preserve the integrity of another’s individual tasks, while nevertheless building opportunities for knowledge sharing and other forms of collaboration. We do not believe that the interactional practices we observe in this research study are exclusive to open-plan offices. However, we do believe that they are highly relevant to our understanding of open-plan offices – indeed, open-plan offices are a perspicuous setting for the study of interruptions and the study of these interruptions similarly provide insights relevant to wider debates around work in the open-plan office.

Building on from this, the findings offer a new lens from which to consider to Feldman and Greenway’s (Citation2021) interest in the ways in which participant differentiate between positive interruption experiences and negative interruption experiences. Feldman and Greenway (Citation2021) discuss how interruptions are perceived as more positive if they are seen to be worthy of the participant’s time, arriving at an appropriate time, and not seen as taking up too much time. Rather interestingly, we see how the interactional practices bound up with the initiation of conversations are designedly oriented to similar features. That is to say, not only are these matters of concern to those interrupted, but to those designing the interruption. For instance, prior to initiating talk, individuals are highly sensitive to the conduct of colleagues, almost surreptitiously scrutinising their conduct to seek to determine an upcoming break or boundary in the activity in which they are engaged (see extracts 1, 2 and 4). The data extracts also show how individuals routinely build in a warrant into their initiation of an interruption, attending to how the person can help and how long it will take by alluding to the brevity of the proposed encounter (see extracts 1 and 2), giving background to the query at hand (see extract 4). Furthermore, they also suggest the timeliness, or ‘timeworthiness’, of the interruption by reflecting the kind of urgency needed to resolve it (see extracts 1 and 3). In this way, the article shows that in the design of their interruptions, individuals display a clear sensitivity to the very same elements of timeworthiness, timing and duration that are found by Feldman and Greenway (Citation2021) to be features of positive interruptions.

More broadly still, this then brings into view our distinctive concern with interaction. The interactional lens we adopt moves beyond the common focus on the views or experiences of individuals being interrupted and works to reveal two key aspects of work in the open-plan office. Firstly, it brings to light the effort and work undertaken by those who want to initiate a new conversation in the open-plan office. Indeed, the person interrupting will often have limited access to their colleague’s activity, they cannot see precisely what is on their screen or the specific task in which they engaged, but from such matters as the pace and force of key-strokes, the structure of glances and the use the mouse, they begin to discern upcoming junctures, boundaries within the emergent activity (excerpt 1). Such effort is disregarded in the myriad of studies around interruption in open-plan offices. And, secondly, the interactional lens rather powerfully reveals the ways in which these brief encounters in the open-plan office are initiated progressively and are contingently accomplished. They are far from unilateral. We see how, for example, how those interrupted will often complete some element of their task in progress while displaying, through its embodied production, both a disengagement from that task and a concomitant re-focusing on their colleague and their concern (extracts 3 and 4). In these ways and others, the shape and progressivity of these encounters can be seen to collaboratively accomplished throughout.

This raises questions about how we can best research and analyse interruptions and the open-plan office. For instance, Feldman and Greenway (Citation2021, 97) suggest that ‘organizations could develop training programs to teach employees how to interrupt others in ways that are more likely to yield positive emotions’. To complement that aim, our study offers materials and insights that could be used to underpin those organisational efforts. Furthermore, while the research lens in many studies of the open-plan office considers the ‘interrupted employee’, our study encourages an approach that takes seriously the interplay of conduct amongst personnel. For instance, while one line of research (see Wajcman and Rose Citation2011) is to consider how individuals manage their availability (headphones, do not disturb signs, etc.), it would be just as fruitful to consider how their colleagues attend to those techniques when they need to initiate conversations with them. And, furthermore, as virtual teams proliferate, we might consider the extent to which the interactional practices that we have identified in the open-plan office are relevant to, or replicated in, video-mediated communication.

6. Conclusion

It has long been recognised, from the early ethnographies of the Chicago school onwards, that the culture or rather cultures of organisation arise in and are sustained through social interaction. In recent years, we have witnessed the emergence of methodological and analytic resources that have provided the opportunity to scrutinise the interactional organisation of occupational activities and demonstrated the ways in which the fine details of talk and embodied action underpin cultures of work and organisation. The open-plan office is particularly interesting in this regard, raising issues of policy and of ideology that bear upon contemporary notions of work and collaboration. It allows us to explore how participants themselves resolve one of the central tensions that arise by virtue of the commitment to creating spaces that facilitate knowledge sharing, informal communication and collaboration, namely how personnel reconcile openness and availability with the responsibility to undertake independent and interdependent tasks and activities within a complex division of labour. In this paper, we hope to have spotlighted some of the interactional practices that underpin and sustain the culture of these particular organisational settings and the flexible, interdependencies of task and activity on which they rely.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank current and past members of the Work, Interaction and Technology Group at King’s College London, for your invaluable help over the years on this research study, in particular Paul Luff and Dirk vom Lehn.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 All the names of people used throughout this article are pseudonyms.

References

- Appel-Meulenbroek, R., B. de Vries, and M. Weggeman. 2017. “Knowledge Sharing Behavior: The Role of Spatial Design in Buildings.” Environment and Behavior 49 (8): 874–903.

- Baldry, C. 1999. “Space - The Final Frontier.” Sociology 33 (3): 535–553.

- Baldry, C., and A. Barnes. 2012. “The Open Plan Academy: Space, Control and the Undermining of Professional Identity.” Work, Employment and Society 26 (2): 228–245.

- Bernstein, E., and S. Turban. 2018. “The Impact of the ‘Open’ Workspace on Human Collaboration.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 373 (1753): 20170239.

- Bjerrum, E., and S. Bødker. 2003. “Learning and Living in the ‘New office’.” in Proceedings of the Eighth European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. ECSCW 2003 (Helsinki, Finland, Sep. 14–18). Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003, pp. 199–218.

- Boutellier, R., F. Ullman, J. Schreiber, and R. Naef. 2008. “Impact of Office Layout on Communication in a Science-Driven Business.” R and D Management 38 (4): 372–391.

- Burkeman, O. 2013. “Open Plan Offices Were Devised by Satan in the Deepest Caverns of Hell.” The Guardian, 13 November. http://www.theguardian.com/news/2013/nov/18/openplan-offices-bad-harvard-business-review.

- Crouch, A., and U. Nimran. 1989. “Office Design and the Behavior of Senior Managers.” Human Relations 42 (2): 139–155.

- Danielsson, C. B., and L. Bodin. 2009. “Difference in Satisfaction with Office Environment among Employees in Different Office Types.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 1: 241–257.

- Danielsson, C. B., H. S. Chungkham, C. Wulff, and H. Westerlund. 2014. “Office Design’s Impact on Sick Leave Rates.” Ergonomics 57 (2): 139–147.

- De Croon, E., J. Sluiter, P. P. Kuijer, and M. Frings-Dresen. 2005. “The Effect of Office Concepts on Worker Health and Performance: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Ergonomics 48 (2): 119–134.

- Drew, P., and J. Heritage. 1992. Talk at Work: Interaction in Institutional Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fayard, A. L., and J. Weeks. 2011. “Who Moved My Cube.” Harvard Business Review. July–August Issue. https://hbr.org/2011/07/who-moved-my-cube.

- Feldman, E., and D. Greenway. 2021. “It's a Matter of Time: The Role of Temporal Perceptions in Emotional Experiences of Work Interruptions.” Group & Organization Management 46 (1): 70–104.

- González, V. M., and G. Mark. 2004. “Constant, Constant, Multi-Tasking Craziness.” Managing muLtiple Working Spheres. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 113–120).

- Gylfe, P., H. Franck, C. LeBaron, and S. Mantere. 2016. “Video Methods in Strategy Research: Focusing on Embodied Cognition.” Strategic Management Journal 37 (1): 133–148.

- Hamilton, C. I. 2011. The Making of the Modern Admiralty: British Naval Policy-Making, 1805-1927. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. (p. 15).

- Heath, C., J. Hindmarsh, and P. Luff. 2010. Video in Qualitative Research. Sage Publications, Los Angeles.

- Heath, C., and P. Luff. 2000. Technology in Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. 1984. Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Hindmarsh, J., and N. Llewellyn. 2018. “Video in Sociomaterial Investigations: A Solution to the Problem of Relevance for Organizational Research.” Organizational Research Methods 21 (2): 412–437.

- Hindmarsh, J., and A. Pilnick. 2007. “Knowing Bodies at Work: Embodiment and Ephemeral Teamwork in Anaesthesia.” Organization Studies 28 (9): 1395–1416.

- Hughes, E. C. 1958. Men and Their Work. Glencoe, Illinois: Free Press.

- Hutchinson, V., and P. Quintas. 2008. “Do SMEs Do Knowledge Management? Or Simply Manage What They Know?” . International Small Business Journal 26 (2): 131–154.

- Jefferson, G. 1984. “Transcript Notation.” In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis, edited by J. M. Atkinson, and J. Heritage, ix–xvi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kaarlela-Tuomaala, A., R. Helenius, E. Keskinen, and V. Hongisto. 2009. “Effects of Acoustic Environment on Work in Private Office Rooms and Open Plan Offices–Longitudinal Study During Relocation.” Ergonomics 52 (11): 1423–1444.

- Kellaway, L. 2013. “The Beginnings of the Modern Office.” BBC Radio. July 22. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-23502251.

- Kim, J., and R. de Dear. 2013. “Workspace Satisfaction: The Privacy-Communication Trade-off in Open Plan Offices.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 36: 18–26.

- Koskinen, K. U., P. Pihlanto, and H. Vanharanta. 2003. “Tacit Knowledge Acquisition and Sharing in a Project Work Context.” International Journal of Project Management 21 (4): 281–290.

- Latham, H. 1987. “Speech Communication in the Office.” Facilities 5 (12): 7–13.

- LeBaron, C., M. K. Christianson, L. Garrett, and R. Ilan. 2016. “Coordinating Flexible Performance During Everyday Work: An Ethnomethodological Study of Handoff Routines.” Organization Science 27 (3): 514–534.

- LeBaron, C., P. Jarzabkowski, and M. G. Pratt. (Eds.) 2018. “Special Issue on Video-Based Research Methods.” Organizational Research Methods 21 (2): 239–260.

- Llewellyn, N. 2015. “He Probably Thought we Were Students’: Age Norms and the Exercise of Visual Judgement in Service Work.” Organization Studies 36 (2): 153–173.

- Llewellyn, N., and J. Hindmarsh. 2010. Organisation, Interaction and Practice. Studies in Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Luff, P., and C. Heath. 2015. “Transcribing Embodied Action.” In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, edited by D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, and D. Schiffrin, 367–390. New Jersey, US: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Maher, A., and C. von Hippel. 2005. “Individual Differences in Employee Reactions to Open Plan Offices.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 25 (2): 219–229.

- Mark, G. 2015. “Multitasking in the digital age.” Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics 8 (3): 1–113.

- McElroy, J. C., and P. C. Morrow. 2010. “Employee Reactions to Office Redesign: A Naturally Occurring Quasi-Field Experiment in a Multi-Generational Setting.” Human Relations 63 (5): 609–636.

- Nesta. 2015. Machines for Thinking. Nesta Blog. [Blog Post]. January 28. https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/machines-thinking.

- Nicolini, D. 2017. “Practice Theory as a Package of Theory, Method and Vocabulary: Affordances and Limitations.” In Methodological Reflections on Practice Oriented Theories, edited by M. Jonas, B. Littig, and A. Wroblewski, 19–34. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Oittinen, T. 2018. “Multimodal Accomplishment of Alignment and Affiliation in the Local Space of Distant Meetings.” Culture and Organization 24 (1): 31–53.

- Oldham, G. R., and D. J. Brass. 1979. “Employee Reactions to an Open Plan Office: A Naturally Occurring Quasi-Experiment.” Administrative Science Quarterly 24 (2): 267–284.

- Oshima, S., and B. Asmuß. 2018. “Mediated Business: Living the Organizational Surroundings–Introduction.” Culture and Organization 24 (1): 1–10.

- Puranik, H., J. Koopman, and H. C. Vough. 2020. “Pardon the Interruption: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda for Research on Work Interruptions.” Journal of Management 46 (6): 806–842.

- Reay, T., A. Zafar, P. Monteiro, and V. Glaser. 2019. “Presenting Findings from Qualitative Research: One Size Does Not Fit All!.” In The Production of Managerial Knowledge and Organizational Theory: New Approaches to Writing, Producing and Consuming Theory, edited by T. B. Zilber, J. M. Amis, and J. Mair, 201–216. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

- Samra-Fredericks, D. 2004. “Understanding the Production of ‘Strategy’ and ‘Organization’ Through Talk Amongst Managerial Elites.” Culture and Organization 10 (2): 125–141.

- Sonnentag, S., L. Reinecke, J. Mata, and P. Vorderer. 2018. “Feeling Interrupted—Being Responsive: How Online Messages Relate to Affect at Work.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 39 (3): 369–383.

- Stanko, T. L., and C. M. Beckman. 2015. “Watching you Watching me: Boundary Control and Capturing Attention in the Context of Ubiquitous Technology use.” Academy of Management Journal 58 (3): 712–738.

- Sundstrom, E., R. E. Burt, and D. Kamp. 1980. “Privacy at Work: Architectural Correlates of job Satisfaction and job Performance.” Academy of Management Journal 23 (1): 101–117.

- Sundstrom, E., R. K. Herbert, and D. W. Brown. 1982. “Privacy and Communication in an Open Plan Office: A Case Study.” Environment and Behavior 14 (3): 379–392.

- Tuncer, S. 2018. “Non-participants Joining in an Interaction in Shared Work Spaces: Multimodal Practices to Enter the Floor and Account for It.” Journal of Pragmatics 132: 76–90.

- Tuncer, S., and C. Licoppe. 2018. “Open Door Environments as Interactional Resources to Initiate Unscheduled Encounters in Office Organizations.” Culture and Organization 24 (1): 11–30.

- Wajcman, J., and E. Rose. 2011. “Constant Connectivity: Rethinking Interruptions at Work.” Organization Studies 32 (7): 941–961.

- Whittaker, S., D. Frohlich, and O. Daly-Jones. 1994. “Informal Workplace Communication: What Is It Like and how Might we Support it?” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 131–137. Boston, USA: ACM Press.

- Yamauchi, Y., and T. Hiramoto. 2016. “Reflexivity of Routines: An Ethnomethodological Investigation of Initial Service Encounters at Sushi Bars in Tokyo.” Organization Studies 37 (10): 1473–1499.

- Zalesny, M. D., and R. V. Farace. 1987. “Traditional Versus Open Offices: A Comparison of Sociotechnical, Social Relations, and Symbolic Meaning Perspectives.” Academy of Management Journal 30 (2): 240–259.