ABSTRACT

Technology-driven workplace tracking is becoming increasingly widespread and normalized. However, experiences of the tracking practices and their impact on individual employees and employers are not fully understood. Eleven qualitative interviews investigated employees’ and employers’ subjective and affective perceptions and experiences of workplace tracking, finding that employees were ambivalent about being tracked, their divergent feelings affecting their actions and experiences, while employers emphasized the benefits, concerns and rationales of the practice. This research highlights the affective side of the tracking practice by revealing how employee and employer experiences and perceptions of workplace tracking are embodied in divergent ways, with meanings ascribed to technologies culturally situated, mediated by context, positionality and use. Recommendations are proposed for further research as well as a collective policy framework governing workplace tracking to address current tensions within a fairer organizational culture.

Introduction

Workplace tracking via digital technologies can take on any number of forms and includes the tracking and monitoring of employees by employers and organizations (Lupton Citation2016; Moore Citation2018b). The process can be subtle and unnoticed, like the ambient data collected through building access cards or cash register logs tracking employee transactions, to more invasive methods such as geolocation tracking of an employee’s whereabouts, equipment or perceived productivity (Ball, Di Domenico, and Nunan Citation2016; Lupton Citation2016; Moore Citation2018b). Motivations for organizations to embrace these technologies include opportunities for increasing productivity and economic growth by leveraging control over workers, while improving business processes and marketing to customers (Moore Citation2018a; Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021). The desire for enhanced productivity and earnings has seen policy favour the introduction of tracking technologies in government and businesses across European, North American and Australasian countries, more often than not, without careful review or supporting social and cultural rearrangement (Dean and Spoehr Citation2018). This is concerning as there is currently a lack of adequate legislation or agreed practice protecting employees from the increased uptake of technology-driven tracking in the workplace (Moore Citation2018b). Employees and employers are invariably left to negotiate the machinations of workplace tracking on their own.

Understanding how employees and their employers are negotiating social meaning, norms and purposes of technology-driven tracking in the workplace is complicated, problematic and challenging (Moore Citation2018b), and the motivation for this study. As the rules of engagement change so too does the social meaning employees assign to their work practices (Nicolini Citation2013). Management research, for the most part, has tended to focus on the positives of technological innovation and data analytics while neglecting adverse outcomes for staff (Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021). Studies challenging these positive framings of technological innovation within organizational settings have included Anteby and Chan’s (Citation2018) technology-driven coercive surveillance study; Elmholdt, Elmholdt, and Haahr’s (Citation2021) investigation of digital self-tracking affordances in the workplace; and the subjective experiences of digital technology within employment settings (Manley and Williams Citation2022) and everyday personal usage (Lyall and Robards Citation2018). It is at the nexus of these studies that our research seeks to extend this contribution to further understand workers subjective interactions with workplace tracking technology. Therefore, this study seeks to understand the affective experiences of workers with workplace tracking technologies and how these encounters shape impressions of fairness and justice within the workplace. This study contributes to existing research by presenting an empirical and qualitative analysis of the subjective understandings, perceptions and experiences of both employees and employers involved in the constellation of workplace tracking; we reveal some of the more critically divergent views of this contested space and propose a way forward.

Twelve employees and employers participated in 11 semi-structured interviews conducted in 2019. The interviews sought both employees’ and employers’ perceptions of workplace tracking, generating insights across everyday practices, experiences, oversight and management. For convenience, two participants from the same organization conducted their interview together. Two other participants had higher duty roles and therefore were able to provide reflective responses as both an employee and employer. Our analysis of the participants’ responses generates new understandings of the subjective and affective meaning placed on workplace tracking processes and practices and demonstrates how tracking can shape employee assumptions, perceptions and values of employment, directly impacting conceptions of fairness within their organization.

In our literature review, the arguments and theories relevant to organizational justice, surveillance and workplace tracking are highlighted for their significance, especially to employee experiences. Next, we describe the theoretical foundations and methodology for the research. Key findings are then presented, including employees’ actions and feelings in the embodiment of tracking technology, affective response, the impacts of being watched and resentment as well as the highlighted benefits, concerns and rationales of the tracking, along with slippages in managing its monitoring. We follow with a critical discussion of the implications of this research, concluding with recommendations for future policy design to alleviate some of the tracking’s more oppressive features. The limitations of the study and further research priorities are also outlined.

Literature review

Workplace tracking

Workplace tracking is not a straightforward nor universal practice, rather, it is situated within the complex weave of workplace relations and organizational culture, which is messy, contested and negotiated. It encompasses a wide variety of activities, from the positive inducement of health and wellbeing tracking programmes (Richardson and Mackinnon Citation2018) to dictating and monitoring dispatch times in warehouse settings (Moore and Robinson Citation2016), as in the case of Amazon with ‘heightened stress and physical burnout’ among workers the result (Moore Citation2018b, 164).

In some workplaces, staff can have their web-browsers and computers monitored with productivity apps such as Work Time and Better Work (Lupton Citation2016), allowing both the employee and employer to measure the time spent on tasks and respond accordingly in terms of issuing rewards or penalties. While employee performance management is an often-cited case for technology-driven workplace tracking, there is no one simple reason that organizations track employees. There is no doubt that an important motivation for monitoring worker productivity is not to manage individuals, but to collect empirical evidence for business process improvement (Rossi and Lindman Citation2014; Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021). The data yield from analytics are becoming a favoured tool for management because it brings an air of objectivity and statistical certainty to the measurement of activities that can be used to benchmark improvements and reduce costs.

Workplace surveillance via CCTV cameras, device and computer monitoring, biometric finger printing, and GPS tracking often occur via incidental processes implemented under a logic of improved safety and security for the benefit of employees (Clark Citation2019; Marx Citation2016b). Tracking does not need to be fixed to the workplace and is being applied in ways that continuously redefine the physical space and the parameters of work activities. A common example of this includes the monitoring of the driving behaviours of truck drivers via GPS tracking and onboard diagnostic systems for the purpose of delivery route optimization (Hopkins and Hawking Citation2018).

Moreover, with the rapid shift to remote work amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic, Microsoft Teams and other collaboration and communication software are being used by organizations to monitor employees, fostering an atmosphere of constant surveillance (Jeske Citation2021). Carr (Citation2020) likened the architecture of platforms like Microsoft Teams and Zoom to the Panopticon, with everyone performing the dual roles of watchers and the watched. Workplace tracking demonstrates a real and growing emphasis on metricizing and anatomizing the individual in ways that reinforce scientific approaches to the management of labour, asserting an individualistic sense of responsibility, aligned with the principles of neoliberalism (Mennicken and Espeland Citation2019). We are at a point in time where the hyper-individualism of the contemporary worker is being promoted while collective employee powers, such as trade unionism, are weakening (Dardot and Laval Citation2013).

Within this, it is critical to understand the affective and subjective experiences of those who are tracked. Existing research has placed more emphasis on explaining why workers accept tracking technologies, their coalescence is often explained by the precarious nature of their employment, the power imbalance present in employment settings, and the general doxic relationship of practice with digital devices and data (Moore Citation2018c; Smith Citation2018). There is a gap in the literature relating to understanding the contextually situated nature of worker responses to tracking that this research addresses.

Digital tracking in organizations: perceptions of fairness

It is critical to consider how workplace tracking can shape localized workplace contexts including the degree to which tracking is accepted and embraced or mistrusted and contested by staff depending on position and roles, i.e. is the tracking perceived as fair and just. Presently there is a lack of primary research pertaining to the effects of an increasingly technologically mediated workplace on employee perceptions of fairness. To understand a worker’s perception of fairness there needs to be a consideration for how employees conceptualize their working environments. Employees shape assumptions and values of their workplace dynamically through manifestation, realization, symbolization and interpretation of their organizational context (Hatch Citation1993). The need to understand this dynamic shaping of employment working contexts has been echoed in recent workplace tracking studies calling for research to move beyond simple dyadic investigation (of the observer and the observed) to a lively, affective behavioural understanding (Leonardi and Treem Citation2020; Newlands Citation2021). So, how do employees’ assumptions of the way something should be translated into practice? How do the artefacts of communication, process and feedback in workplace tracking impact employees’ values? What symbols adhere? Is tracking perceived as authoritarian, invasive and burdensome or, efficient, productive, accountable and positive? These are just some of the considerations that coalesce around workplace tracking and employees’ and employers’ perceptions of fairness.

The way workplace fairness is conceptualized in academic research is through the notion of organizational justice and the belief that if employees are treated fairly, they will engage more productively in their organizations (Elliot and Arthur Citation2020; Nabatchi, Bingham, and Good Citation2007; St-Pierre and Holmes Citation2010). Conversely, if workers feel mistreated, they can experience feelings of anger, outrage and resentment (Nabatchi, Bingham, and Good Citation2007). Mediating employees’ perceptions of fairness are the actions of their supervisors and managers, and the organization itself, indicating that there are multiple sites of (in)justice for employees to navigate (Konovsky Citation2000; Rupp and Cropanzano Citation2002; St-Pierre and Holmes Citation2010).

Of key significance in our research is the issue of procedural justice and workers’ perceptions of fairness in the procedural actions of tracking and outcomes in work processes (Nabatchi, Bingham, and Good Citation2007; Rupp and Cropanzano Citation2002; St-Pierre and Holmes Citation2010). Six criteria are critical in driving procedural justice: consistency, bias-suppression, accuracy, correctability, representation and ethicality (St-Pierre and Holmes Citation2010). Jeffrey (Citation2000) has previously highlighted how digitally monitored employees want some level of control over consistency, accuracy, necessity, process or outcome of monitoring in their workplace, and that is an issue we take up in this research.

Unsurprisingly, when these actions are not achieved the worker can feel alienated and disenfranchised (Moore Citation2018b; Stein et al. Citation2019). Conversely, workers who perceive workplace tracking as fair tend to have some control over the process and are satisfied with the programme (Jeffrey Citation2000). Hence, when perceptions of fairness are lacking, workplace tracking can resemble methods of surveillance, creating conflict and leading to opposition and resistance from the employees.

Workplace control and surveillance: changing perceptions of fairness

Traditional theorizing about organizational surveillance tends to centre around Foucauldian theory and the panoptic schema of self-management, discipline and control (McKinlay and Starkey Citation1998; Sewell Citation1998). However, the intensification of surveillance in organizational settings through technological development has seen theoretical shifts in the framing of this, with many scholars now examining workplace tracking as an act of surveillance capitalism (Ball Citation2010; Hassard and Morris Citation2021).

Surveillance capitalism links economic and corporate advancement to the systemic logic of accumulating data as the fundamental model for the creation of wealth (Zuboff Citation2015). At the same time, surveillance capitalism repositions perceptions of fairness and justice for employees. The prioritization of data as a mechanism for generating profit, provides the rationale for organizational surveillance. If new products and insights, and greater efficiency and effectiveness, are built on technology for ‘mediating, gathering, storing, processing and distributing information’ (De Vaujany et al. Citation2021, 680), then the more employee data organizations have the greater the opportunity for a competitive advantage. In this sense, organizational surveillance is located, not as an isolated object of technology, but as an embodied activity etched into the everyday work practices of corporations aiming to use data to predict, control and change worker behaviours for economic advancement (Zuboff Citation2015). Under the logic of surveillance capitalism, procedural justice is difficult to locate as an employee’s embodied practice is the site of surveillance.

In organizational settings, technology is presented conversely, as freeing, and making things easier and more convenient for the worker (De Vaujany et al. Citation2021; Hassard and Morris Citation2021; Villadsen Citation2017). Nevertheless, just as greater autonomy is offered through technology, so too is the level of control and monitoring placed onto the worker. It is critical to understand how workers’ perceptions of fairness and justice are changing as workplace technology impacts employees’ work-life balance, the spatio-temporal boundary of employment settings, monitoring outside of work, the contractual relationships of employment, unpaid work hours and the exploitation of labour (De Vaujany et al. Citation2021; Hassard and Morris Citation2021; Villadsen Citation2017). In essence, the practices of workplace tracking are shifting from a space of dyadic exchange between managers and workers to a complicated confederation of people and machines in society with both soft and incidental, and direct and conspicuous surveillance taking place (Jensen et al. Citation2020; Marx Citation2016b). These confederations legitimize a culture with surveillance creep in full flight, where monitoring and tracking of people and mining of their data – as another corporate-owned asset – is normalized and expected (Ball Citation2010; Lyon Citation2018; Newlands Citation2021). What must then be questioned is whether, employee surveillance is operating outside the boundaries of good governance and becoming ungovernable (De Vaujany et al. Citation2021), with unfair implications for workers and unexpected outcomes for organizations (Anteby and Chan Citation2018; Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021). At this juncture our study seeks to extend this research by connecting the potential of digitized technology, like workplace tracking, to appear as a form of oppressive surveillance and control (Anteby and Chan Citation2018), which directly impacts the employee’s conceptions of fairness.

Newlands’s (Citation2021) research on food delivery workers in the gig economy, at platforms including Deliveroo, Foodora and UberEats, exemplifies how technology is shifting employee perceptions of fairness and justice through algorithmic surveillance. What results is artificial intelligence continuously monitoring and analysing worker performance, while allocating tasks in a recursive model that sees future earnings determined by recent data inputs, including time to accept an order, travel time to restaurants and customers, and number of orders (Veen, Barratt, and Goods Citation2020). This performance data are used to continuously train the system, creating a situation where workers are excluded from tasks algorithmically. Deliveroo’s performance reports notify workers of their status, including whether or not they meet or fall below stipulated service level criteria (Veen, Barratt, and Goods Citation2020), however this is absent of context and circumstances (Newlands Citation2021). For example, effects of one-off traffic conditions, delays in meal preparation time by the restaurant, are all outside of a worker’s control. When managerial surveillance is offset with algorithmic surveillance, human control and insight are reduced. The effects of employee monitoring can become normative, transforming worker values towards cooperation in order to receive the next piece of work, while strengthening managerial prerogative. While simultaneously weakening worker perceptions of fairness and procedural justice as machine-driven control and management are unable to account for employee subjectivities.

Organizational and managerial literature regarding workplace tracking tends to emphasize the organization’s benefits, while neglecting the context, including the human, affective and emotional side of workplace tracking. Much of the literature positions workplace tracking as being normalized and in the background – out of sight and out of mind – with the worker’s acceptance assumed (Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021). Our study challenges this notion and proposes the affective and sensed nature of the monitoring must be considered as it is very much at the forefront of the worker’s experience. Our approach is in line with De Vaujany et al. (Citation2021, 683) who argue that ‘control and surveillance [is] being increasingly enacted through sensory perception and affect’. Therefore, qualitative inquires uncovering in-depth knowledge of workers’ affective encounters, and subjective perceptions and experiences, with workplace tracking is critical (Ball Citation2001). Especially considering the unprecedented rapid shift to digitized remote working resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic (Hassard and Morris Citation2021; Kolb et al. Citation2020; Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021).

Affect theory in workplace tracking

The theoretical lens our research brings to the work is that of subjectivity, embodiment and affect, positioning the worker not as a passive end-user in the digital tracking monolith, but rather, as a ‘digital wayfarer’ (Hjorth and Pink Citation2014, 45) with agency ‘actively working to engage in data sense-making’ (Lupton Citation2017, 4). The tracked worker is on a trajectory in which they consider and analyse different aspects of the process as a set of embodied experiences in their lives, ‘learn[ing] as they move through a digital material environment’ (Fors et al. Citation2020, 29). In an organizational setting, the worker’s subjective, embodied experience of being monitored will shape their assumptions and perceptions of work practices, values and beliefs and conceptions of fairness within their organization.

An example of worker embodiment of workplace tracking can be found in Richardson and Mackinnon’s (Citation2018) study of university staff experiences of a health and wellbeing tracking programme. Some staff found that they continued to monitor their sedentary levels at work once the programme had ended. Their tracking was performed with either a device or cerebrally through their tacit knowledge of required daily levels of activity, in turn, interpreting their actions heuristically. Unbeknown to the staff, however, was that the goal of their employer was for workers to form the health and wellbeing programme into a habitual, embodied continuous action, thus optimizing health and productivity levels (Richardson and Mackinnon Citation2018). Workplace tracking, from this perspective, generates affective forces which come to shape the behaviour and identities of workers.

Affects are intensities made, transmitted and felt through the body and surrounding material infrastructures, that are reconceptualized by the mind as feelings; this offers the subject the potentiality to be affected or affect change onto others (Massumi Citation2002; Moore Citation2018b) and the researcher the opportunity to understand new phenomena from its affect. Philosophers Massumi (Citation2002), Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) have linked affect to the realm of human–nonhuman interactions, and this has been extended to digital tracking, where researchers have highlighted agentive and affective forces found in an array of tracking practices (Lupton Citation2020a; Pink et al. Citation2017; Sumartojo et al. Citation2016). For example, the affective forces found in digital tracking research include: empowering you, make you change, surprise you, be overwhelming, make you feel good or make you feel bad (Lupton Citation2020a), to name a few. Framing this study through an affective lens presents an opportunity to understand how employees and employers’ experience workplace tracking as part of their organization and how perceptions of fairness are manifested. Moreover, understanding of the affective dimensions co-created between people and technology can illuminate how surveillance cultures are produced within the workplace further impacting conceptions of fairness and justice for the employee.

Methodology

This research is guided by a qualitative and interpretive approach to elicit a deeper understanding of how employees and employers’ inter-subjectively engage in and understand workplace tracking. Semi-structured interviews were chosen because of their open-ended nature and capacity to interrogate the experiences, understandings and feelings people have that are not easily quantifiable (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2012). This method allowed for an in-depth approach to data collection with interpretive content and thematic analysis emergent from within the initial interview questions.

Sampling and data collection

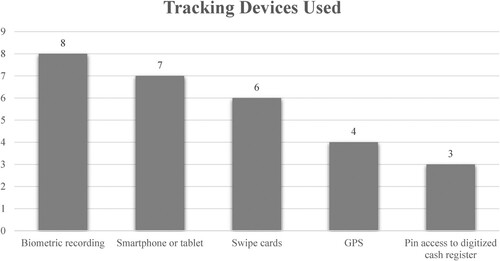

The only sample requirement for the study was that participants used some form of digital tracking in their everyday work duties. For this study, digital tracking technologies are considered any form of digital technology that tracks an action of an employee or employer. This included sensor-driven devices that are warn such as GPS trackers, to static unobtrusive technologies like digital timesheets, cash register logon systems or building entry logs. Three managers from two organizations agreed to participate in the study. Once the managerial interviews were conducted, we sought permission to contact employees from the same companies, using a snowball sampling method (Robson Citation2011). Of the 19 employees we approached, four agreed to participate. To generate the remaining sample, we advertised the research project over different social media platforms, with a further five participants agreed to be interviewed. As a result, there were 12 employees and employers located in three states and territories across Australia who participated. They represented a range of vocations (see ) and engaged with several different types of workplace tracking (see ). Interviews took place between June and July 2019. Both the employer and employee interviews had similar questions, although the sequence of questions differed in each interview, depending on the responses provided. Employee interviews were conducted in local cafes away from their place of work, while for participants not living in the Canberra region they were held online. Employers on the other hand were happy to conduct their interviews at their place of business.

Table 1. Workplace tracking either performed or endured by participants.

Analysis

In preparation for coding, the interviews were transcribed verbatim to ensure that each participant’s voice was captured and heard (Freeman and Neff Citation2021). Analysis then began with a close reading of the data, looking for particular actions, processes, terms, feelings, beliefs and meanings presented by the participants (Charmaz Citation2014). This line-by-line coding offered the opportunity for different thematic threads to be detected. The analysis concluded with the most significant and frequent codes identified and given analytical importance over less frequently mentioned initial codes (Charmaz Citation2014). While relevant theories, discussed previously, informed the design of this study, including the interview schedule, the coding process was inductive and interpretive, allowing participants’ voices and experiences to shape the findings. What resulted was a theoretical framework, which incorporated nodes such as embodiment, affects, feelings of being watched, employee resentment, employer perceptions and rationales and employer slippages, which are expanded on in the following section. Before the findings are presented we acknowledged the limitations of our methodology.

Limitations

This qualitative study offers new insights into workplace tracking, contextually situated through the lens of human experience. Research of this nature is particularly critical currently as a diverse array of technology-driven tracking is expanding across a varied range of organizational settings where big data analytics and business intelligence predominate (Moore Citation2018b). As yet, adequate social understandings of the implications of workplace tracking have not been reached (Moore Citation2018b), and a deeper understanding of the subjective and affective experiences of organizations and their staff will help to foster a wider collective social meaning of the practice.

By interviewing employees and employers about their experiences of workplace tracking, this study contributes to an empirical understanding that will inform future research agendas, policies and practices of workplace tracking. As this study attracted participants on a voluntary basis, using snowballing methods through personal contacts and online advertisements, researchers did not endeavour to select specific organizations to feature in this research, hence no organization-specific conclusions can be drawn. Therefore, nuanced organizational contexts are outside of this study’s scope. We acknowledge this is a limitation of the study, however it is balanced by the rich personal insights of the individual participants. Limiting this study to perspectives of individual employees also meant that specifics around their terms of employment and contracts were deemed irrelevant to the purpose of the study and not sought.

The wide spread of industries among the sample could also be regarded as a potential limitation of the study. However, the participants’ vocation was not the primary attribute influencing recruitment, rather, it was the participants’ varied experiences of workplace tracking that was the objective. Following on from the procedural justice literature informing this study, irrespective of organizational setting, there are core uniting values through which workers perceive workplace tracking and fairness that this research aims to understand (Elliot and Arthur Citation2020; Greenberg Citation2011; Jeffrey Citation2000; Konovsky Citation2000; Nabatchi, Bingham, and Good Citation2007; Ötting and Maier Citation2018; Paré and Tremblay Citation2007).

Lastly, while we did not intentionally endeavour to recruit participants who held dual roles of employee and employer, there were some who did fit this category, resulting in unexpected findings, for example, exhibiting a higher level of acceptance of tracking. This finding may inspire future research that looks at the role of the organizational hierarchy in individuals’ acceptance of tracking.

Findings

Perhaps understandably, employees’ beliefs, views and feelings towards workplace tracking varied depending on the context of use. Some were unperturbed by the tracking, others were ambivalent about the practice, while some had significant concerns about the implementation process and ensuing outcomes. Employers were, for the most part, optimistic in their depictions of the tracking programmes, citing the potential of digital technology and ensuing tracking cultures to make processes and procedures more efficient. These divergent perspectives made it clear from the outset that workplace tracking is a complex, negotiated and frictional practice, that is constructed and mediated within the existing socio-cultural relations of the work environment.

Employee perspectives

Embodiment

All participants described some form of embodiment – the tangible coalescence of being monitored within themselves – in their interactions with workplace tracking. The most frequent response was that it had become normalized into a habitual work process. For example, for Participant 5 (P5), workplace tracking such as having their speed and location monitored of their car ‘just become a normal part of the job … It just became something you did, and you didn’t think about it’, while P1 added:

I’m sort of surprised at how much I’ve just taken to doing it [smartphone recorded timesheets] … I’ve never had to do that before. And now it’s just like second nature … just get my phone out [and] sign out.

This embodiment of workplace tracking also changed employee behaviours. P2 demonstrated this point by stating:

I look at myself in my position right now, I’d say I am probably a much more careful worker. Yeah, I mean it’s [the tracking] forced me to be really scrupulous and careful with my time. I’ve changed the way I operate my work calendar and even schedule appointments to check my email … I feel that it’s necessary. I wouldn’t have done that before.

Affects

The affective dimensions of workplace tracking elevated the importance of self-management for most participants, with a heightened sense of awareness of tracking around tasks. P1 demonstrated this with their digital timesheet: ‘Today was busy [and] I worked through without having a break. But I notice there’s a half-hour break taken off so I can then edit that and remove that break from my shift’. In contrast, other participants explained that peers would self-manage the operation of workplace tracking. P7 explained how peers tried to bypass the tracking of transactions on a cash register by keeping a worker’s log-in open: ‘Some people have made a habit of logging on and just keeping it that way in case it gets busier. And I have made a habit of logging off every time someone does that’. While P6 noted: ‘If you don’t have your [digitized security] pass on you other people around the office will probably take notice of it and be really concerned, so you always have to have your pass on you always’. These actions described by P6 and P7 demonstrate the affective force of workplace tracking shaping worker responses.

While the aim of workplace tracking may be about improving efficiencies many of the participants expressed their frustration in a changing practice where the day-to-day activity of workplace tracking at an operational level, could be: ‘really annoying’ (P5 and P11); ‘frustrating’ (P10); ‘[a] little bit clunky’ (P9); and ‘takes forever to do things’ (P6).

Participants also explained both negative and positive affects through the accountability the workplace tracking produced: ‘[I felt] bad about it, that I’m limited or restricted in … normal human behaviour, like just going and chatting with someone’ (P12). However, P9, a hospitality worker who had higher duties, and so provided information as both an employee and employer, interpreted this differently: ‘I enjoy the accountability. It’s good to be able to say, well, you know, you can track back and see, I have done the right thing … I like the accountability’. P9’s dualistic role as employee and employer seems to result in more positive affective moments which shaped their thinking about the tracking.

Moreover, there was a degree of cognitive internalization of the organization’s goals taking place by the workers as they connected to and identified with the aims of workplace tracking. This was evident in the responses of others, for example P2: ‘I really feel that it’s to ensure that the organization is held in the highest level. And if there was something … they can deal with it quickly’. While P5 added: ‘I think it was to improve performance, I think it was ultimately for the franchise to show that we are meeting [their targets], because you know the franchise is under a lot of pressure too from head office’. Responses like this have been identified in a number of other studies, demonstrating that employees’ have a propensity to internalize the goals and objectives of organizational leaders when they are aware of being monitored (Jensen et al. Citation2020; Subašić et al. Citation2011), an observation that challenges ideas that surveillance will improve worker autonomy.

The affective differences in experiences and perceptions noted in our study, about why the tracking exists and how, and for what ends, also highlights the power imbalances located between employees and employers and how that asymmetry is reflected in the ways workplace tracking is engaged with and understood. Participants’ ambivalence expressed underlying concern, for example: ‘I guess, sometimes ignorance is bliss, in a way. Because if I did have access, and understanding of how it all works, maybe it would actually force me to question how it all really functions’ (P10). P2 added: ‘I think most people [fellow peers] appear to have just gotten used to it and go about whatever they are doing. And I think in time I will too. However, I think it’s becoming quite ignorant’.

The personal dimensions of workplace tracking described by the participants demonstrate how digital technology is producing positive and negative changes in the worker’s environment (Moore Citation2018b), with employees left to self-manage and make sense of these changes. This in turn is informed by the affects produced by workplace tracking, with changes impacting the employee’s subjective perceptions of fairness within their organization. What can result are negative assumptions about the technology, mistrust and misgivings towards supervisors and the organization and a sense of punitive workplace culture, as the findings demonstrate next.

Feelings of being watched

All but one of the employees interviewed discussed their feelings of being watched via the tracking programme. At the onset of P9’s employment they felt untrusted due to the monitoring: ‘I was thinking oh no, I am being watched like I wasn’t being trusted’. P2 revealed the same sentiments: ‘I feel that it [smartphone] could be used to listen into [my] conversations at anytime … so, like right now … I could actually be listened to’. The feelings of being watched increased when employees were informed about the tracking. P12 explained the moment their employer informed them that their building access card was also a GPS tracker: ‘[My] manager said to me: … “There is a feature in this card that … can track you” … I said: “No I didn’t know that”. And he said: “We can. We can track you”’. The uncertainty in feelings of being watched without a clear understanding of the procedure or the accountabilities attached to monitoring exacerbated feelings of procedural injustice.

Acceptance of monitoring is premised on a sense of organizational justice and fairness, often found missing in this study. More often than not, interviewees considered the uncertain and ambiguous nature of tracking to be compounded by a lack of justification and responsiveness. P5 explained: ‘There were a few times where I felt like I definitely went over [the speed limit] … but they didn’t notice … there was definitely an element of just knowing that you’re being watched, even if they’re not actually watching’. Another participant explained:

I have a laptop that they gave to me from work. I’m sure it probably has some sort of GPS tracking … I don’t know if they actually actively monitor it. I know that they have the ability to see … our [web-browser] history. But I don’t know if they actually actively monitor what we do (P6).

Employee resentments

For many employees workplace tracking manifested in a sense of uncertainty, estrangement and resentment, exacerbated by feelings of anxiety, stress, annoyance and invasiveness (Moore Citation2018b). P5 summed up these estranged feelings: ‘I always felt anxiety whenever it [speed] flipped up a little bit. I was like, am I going to get pinged for this. So, there was definitely a bit of anxiety … [it] can be a bit of pressure’. Another participant felt that the accountability of working on a secure computer linked to their biometric log-in was complicated, annoying and stressful:

I think it’s just annoying … when … we went from just logging on [to our computers] with your password to the fingerprint. Now, that was a freken (sic) nightmare! Because, if you were stressed, and you get a bit sweaty, it wouldn’t register. So, if you actually had to do something. You know it’s more than annoying. It does affect your health. Yeah. Because there were times when I just felt like smashing the computer! (P11).

But on a personal level. It’s [workplace tracking] so invasive because everything you’re doing, you’re constantly going, is this the right thing to say? … You’re walking on eggshells just waiting, you know, to stand on an egg that just wasn’t a shell!

Employer perspectives

Rationales

The employer experience evident in our study underpins an important observation that workplace tracking is a complex and contested space ascribed through positionality. The risks and benefits, and the upsides and downsides, of workplace tracking vary between different socio-cultural actors in every organization (Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021). Employers’ rationales for implementing workplace tracking included increased productivity, accountability, streamlining processes, cost cutting and increased safety and security. For example, P1 stated that workplace tracking:

Makes it easy for us to process payroll more efficiently and accurately … I think ideally, it’s to make it more streamlined. If the computer has to auto approve shifts that’s one less thing for management to do and you are limiting possible human error.

Benefits and concerns

Employer perspectives often accentuated the benefits of workplace tracking, including a belief that monitoring was accurate and streamlined work processes:

New staff members that come on board love it. Because it’s not just documenting their times in and out, they can put in their availability. So, they can put if they can’t work on certain days permanently, or whether it’s [a] one off day that they want to have off, or they can register their annual leave. They can check the roster on the system, they can also check to make sure they’ve scanned in an out correctly (P8).

Employers also acknowledged that some of their workers did have concerns about the practice, such as misgivings about the processes of biometric tracking. Two organizations in the study have a biometric timesheet system and stated that employees had concerns regarding the use of their fingerprint to log-on. Therefore, both employers pointed out to their employees that the system did not rely on a fingerprint, but the veins in the thumb/finger: ‘It’s not … the fingerprint, it’s the veins that get scanned … [but there was] a handful of people that were sort of a bit sceptical about it at first’ (P8). While P1 added:

Some staff when they start their employment were like, is this a thumbprint thing … Yeah, so many people questioned it … then my new spiel became, you just insert your finger here all the way through [and] it will record the pattern of your veins. So, everyone has been told it’s not recording your fingerprint.

I think, if anything, something we’ve learned from respected people in the cyber industry is that a person sitting getting a briefing or listening to this from the Privacy Officer sits there and says. What is it, what’s in it for me? They related back to the individual (P3).

Employer slippages

In this study, we labelled a number of notable breakdowns in policy or oversight as employer slippages. Employers indicated that slippages in a tracking programme’s implementation and management contributed to employees’ sense of unease and injustice. These employer slippages are examples of how the nuanced balance of risks and benefits of technology-driven tracking in workplaces can slip with unexpected implications to negative consequences for the employees and employers (Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021).

One manager described how the unsuccessful implementation of a digital timesheet system risked the creation of conflicting records, as the old analogue system continued to run alongside the new digital one:

[The workplace tracking] has been there for like three or four years … we still use paper timesheets as well. We’re using two systems with the idea to phase out the paper timesheets and only use the [digital] system … but at this point there’s so many discrepancies between what people do and do not sign out for, and what people write on their timesheets that we haven’t gotten rid of the [paper] timesheets yet (P1).

One of the things that was interesting is that it [digital timesheet system] now becomes, I guess like a digital database. So if we get audited, [say] from the Taxation Department or Fair Work, then they would have a database that they could view … so if a staff member, for instance, put their hand up to Fair Work and said I work eight-hours every day and [was] refused a break. If they [Fair Work] then asked to view the … information … there would be proof, there that that staff member never took a break.

Investigator: So … is it [digital timesheet system] a leased software?

P8: Yes, we pay for the software usage every year.

Investigator: Does [the software company] … have access to any of that data?

P8: They should. Yeah.

Investigator: Are the employees aware of that?

P8: Ummm possibly not. Possibly not. I don’t know. I mean, it would only be certain, I don’t know how they work at [the software company]. It’s just like any sort of software program, whoever makes the software needs to be able to have access to it.

I noticed you use the term tracking. Now, what’s in the name? We don’t refer to some of these devices as tracking, we refer to them as to factor authentication access control and so forth. So, when you use the term tracking, it’s almost implied that you are being followed. We have very, very limited if any, tracking enabled within the department that I’m aware of. So, for example, even your simplistic access control, that’s purely to gain access to authorised areas, it can have that capability enabled, [but] we don’t.

Discussion

This research highlights the affective aspect of technology-driven workplace tracking by showing how employees and employers perceive and ascribe meaning through subjective and embodied experiences of tracking that are complex and, at times, conflicting. This in turn has both positive and negative effects on how workers interpret and understand fairness and justice within their organization.

Collectively, employees express affect when they discuss the recurring theme of experiencing workplace tracking as a normalized, everyday action, formed and embodied in routine. Tracking that can be as simple as logging on and off from the cash system (as demonstrated in P7’s interview) becomes routine, enabling productive work habits that benefit the organization. P7’s embodiment of this type of tracking as justifiable, for contributing to workplace safety corresponds with the perspective of their employer (P8), demonstrating how embodiment as a cognitive act that comprises sensing, feelings and affect can also be intersubjective (Fors and Pink Citation2017; Lupton Citation2020b). Tracking then becomes normative, it is part of being-in the work practice and explains how the embodied experiences of being monitored multiply and are shared by employees and employers.

The affective nature of the tracking assemblage witnessed in this study was, at least in part, one of compulsion, with employees feeling compelled to self-manage their workplace tracking. The evidence indicates that conspicuous forms of monitoring can be coercive, at times this includes peers expecting conformity towards tracking from others (Jensen et al. Citation2020). Self-managing the tracking programme heightened employees’ awareness, both in respect to complications the tracking caused for work processes and the sense of accountability it produced. Most concerning in the acquiescence to workplace tracking that employees noted is the power imbalance it highlights in the workplace (Barry and Wilkinson Citation2011; Rose and Busby Citation2017). The possibility that organizations could achieve better outcomes with less coercive, more balanced, approaches needs to be raised. Employee monitoring adopted under the guise of scrutinizing productivity may not be the best approach to business process improvement or better employee performance (Laker et al. Citation2020).

Employees often discussed monitoring in connection with a feeling of being watched that resulted in resentment, especially when the monitoring was considered excessive or unnecessary and resembled forms of surveillance and control. These sentiments have also been found within research conducted with airport security workers (Anteby and Chan Citation2018) and employees participating in workplace wellness programmes (Elmholdt, Elmholdt, and Haahr Citation2021). This demonstrates, not only how a workers’ sense of procedural justice is embodied in their experience of workplace tracking, but also how important it is for monitoring to be justifiable and valid.

Such perceptions of being watched demonstrated that most employees in the study felt that workplace tracking was not procedurally fair, their assumption being that the programme could be used for punitive and surveillance reasons, for example P5’s belief that monitoring their deliveries could result in repercussions for poor driver behaviour. There is sense here, that the rights of the worker might be undermined by the sharing of data. These feelings are unsurprising with tracking technologies, especially within an unbalanced power dynamic like that existing between employers and employees in the workplace (Andrejevic Citation2019). While it is acknowledged that there is a potential to empower staff through surveillance, the majority of the participants in our study did not feel empowered, and their feelings of being disempowered are concerning.

Workplace tracking is not always conspicuous and can take the form of soft surveillance (Marx Citation2016a) via sensors and devices that collect data incidental to the work activity. Usually, this is done with the worker’s knowledge but without transparency in terms of how it is being used or, with what implications. For example, monitoring swipe card access to authorized areas (as observed by P3) can seem appropriate, providing it does not restrict access to privilege or opportunity. In our study, the employees’ negative affective experiences of being watched, even when it was indirect, such as the anxiety experienced by P11 with the arrival of a biometric log-in system, are understandable. Without a clear understanding of why they are being monitored, or by whom, employees will speculate on the reasons behind tracking and formulate their own subjective conclusions.

Therefore, employees ‘who are under the influence of assumptions will notice and respond to some aspects of the organizational world more than other aspects’ (Hatch Citation1993, 663), i.e. they will interpret things as they seem to be, not necessarily as they are. These subjective assumptions our participants gave to workplace tracking are similar to the findings of past organizational tracking research (Anteby and Chan Citation2018; Elmholdt, Elmholdt, and Haahr Citation2021; Manley and Williams Citation2022). However, significant in the context of our study, and adding to this literature, are our participants’ perceptions that the workplace tracking they were subjected to was procedurally unjust and unfair. Our findings also indicate that at least some of the more negative feelings employees held about the tracking programmes result simply from poor planning. Poor communication and poor management led to slippage around digital tracking programmes that saw them being understood in ways that were never intended. What this highlights is that workplace tracking is neither static nor objective but existing subjectively in flux (Elmholdt, Elmholdt, and Haahr Citation2021; Woolgar and Neyland Citation2013). It is then left to the employees to make sense and manage these changes in their working environment.

The positions adopted by some employers, alongside the experiences of disempowerment and insecurity felt by the workers, created ambiguity between supervisors and workers regarding the meanings, orientations and implications of tracking. The result for the employee is that their working conditions may be transformed, in both positive and negative ways, but that they must assume responsibility for discovering how the tracking is being used, to what effect, and self-manage their own response. This directly impacts the employee’s perceptions of fairness and justice for their position and the organization in general.

Compared to the views of other employees interviewed, our study participants who held the dual role of employee and employer demonstrated a much greater acceptance of digital tracking, as being procedurally fair and just. An observation supporting one of the key concerns coming forward from surveillance capitalism literature: digital technology has the normative effect of changing and moulding worker values and behaviours to elicit new behaviours conforming with expected practice (Zuboff Citation2015). Indeed Anteby and Chan (Citation2018) demonstrated this with their research into airport security workers’ responses to increased security and control. Our research then extended these findings placing workplace tracking within the regime of workplace control (Elmholdt, Elmholdt, and Haahr Citation2021; Manley and Williams Citation2022), which directly impacts a workers perception of fairness and justice.

Our findings correspond with Moore’s (Citation2018b) study, demonstrating that when employers implement workplace tracking without conveying the programme’s real intent to their employees it can be viewed as authoritarian. Workers can become suspicious, disenfranchised and demoralized. To counteract this, we propose that workplace tracking needs to be negotiated and justified through extensive consultation and exchange. The balance of what will and will not be monitored needs to be expressed in clear policies and guidelines with training in suitable governance frameworks undertaken by the monitors. Drawing on the work of Akhtar and Moore (Citation2016, 124; see also Moore Citation2021), we recommend policy management that ensures:

Negotiation with employees before any new forms of employment tracking are implemented. Agreed assurance that the digital tracking programme is equitable and justified.

Open two-way communication with the employee about what is being tracked and why. Full transparency about who has access to generated data, including third-party owners and operators of software.

Clear consent should be sought by the employer and voluntarily given by the employee. Regular feedback, re-consent processes are provided to employees.

Employment tracking is minimized, defined and focussed on business activities that require monitoring. Tracking cannot be ubiquitous and ever-present or experimental. Spaces allocated for workers to go to where they know their actions will not be tracked (see also Kolb et al. Citation2020).

Full consideration for the proportionality of the tracking. Workplace tracking actions and outcome must be justifiable and balanced against impacts on employee’s privacy and autonomy (see also Kolb et al. Citation2020).

Ensure sufficient safeguards are in place including ethical safeguards. Precautions must be in place to ensure the parameters and limits of surveillance are described and implemented with the aim of minimizing intrusion of monitoring and surveillance creep. This should include safeguards for the transparent and ethical use of AI (Floridi Citation2019; Laker et al. Citation2020).

Conclusion

In this paper, we found that employees and employers engaged with digital technologies in highly ambivalent ways that reflected their positionality and work role in the organization and impacted on how they understood the measures that had been introduced. Some were left feeling that digital workplace tracking is a form of conspicuous, hierarchical and procedural surveillance, enabling employers to rigorously monitor their performance, behaviour and presence. This resulted in employees feeling estranged and resentful. Their response is not objective but affective, embodied subjectively in feelings and interpretations, demonstrating that workplace tracking is not simply accepted but is an ambivalent, messy and contested space. In contrast, it was clear that the employers were often ill-equipped in their own technical understanding and rationale for workplace tracking and communicated the intentions and implications of tracking to their staff poorly.

While there is a belief among employers that digital technology is beneficial, objective and can run unabated from human intervention, this did not balance with the experiences of employees. Furthermore, it is when employers implement workplace tracking with inadequate policies and procedures, or poorly communicated goals about outcomes and accountabilities, that the result is defined by experiences of confusion, disempowerment and alienation. Thus, demonstrating how using digital technologies to increase workplace tracking can lead to senses of injustice and unfairness. Rather than accepting digital technology as ungovernable, there needs to be a conceptual shift from organizational leadership in their thinking about surveillance, from a regime of automated control, towards responsibility. Workplaces need to ensure that all the attributes required for good governance are enacted in workplace tracking, from confidentiality to integrity, availability, accountability, transparency, responsiveness and incorporating a participatory approach to the empowerment of employees, to name a few.

This study has been limited by the size and diversity of the sample, our only criteria for sampling being that the participants were engaged in some form of digital workplace tracking. However, the study does include a diverse number of vocations, each with individual and unique social structures, which we consider important, as understanding the impact of workplace tracking will always need to be contextualized to its environment. Even so, from the perspective of procedural justice embedded in this study, it is clear that there is a universal understanding of fairness in the workplace, with themes of openness, consistency and accuracy, challenged in the unified responses of most participants. The findings present a unique, in-depth and rich description of affective experiences of workplace tracking that extends existing studies with new insights into developing work practices, opening up avenues for repositioning the governance of digital technology, improving policy design and for further research.

Our research has demonstrated the importance of understanding workplace tracking through the lens of the people who experience it. We recommend that future research examines employees’ different tactics of dealing with organizational tracking, while investigations focus on specific vocations to uncover a more nuanced and emic understanding of workplace tracking. There is also scope to extend research on employment tracking to other stakeholders in the workplace tracking assemblage. This could include the designers and owners of the tracking devices, software and applications; and the human resource ecosystems that oversee, and legislate, the installation of digital tracking programmes in organizations. Finally, considering the sharp and dramatic way in which some organizations have changed their working habits, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, there are new opportunities to understand what impacts workplace tracking has on remote or hybrid workers (Kolb et al. Citation2020; Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021). Further research into workplace tracking, including the constitution of technology governance, is critical as progressively more employees and employers are required to work with a growing array of advanced digital technologies designed to accumulate and analyse large quantities of employee data via artificial intelligence with very little human intervention. Without these policy and research agendas in place, the likelihood is that modern working conditions will become more oppressive, more contested and problematic for employees and employers in the future.

Acknowledgements

Paul Bowell would like to acknowledge the Commonwealth’s contribution through the receiving of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship during the production of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Akhtar, Pav, and Phoebe V. Moore. 2016. “The Psychosocial Impacts of Technological Change in Contemporary Workplaces, and Trade Union Responses.” International Journal of Labour Research 8 (1–2): 102–131.

- Andrejevic, Mark. 2019. “Automating Surveillance.” Surveillance & Society 17 (1/2): 7–13. doi:10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.12930

- Anteby, Michel, and Curtis K Chan. 2018. “A Self-fulfilling Cycle of Coercive Surveillance: Workers’ Invisibility Practices and Managerial Justification.” Organization Science 29 (2): 247–263. doi:10.1287/orsc.2017.1175

- Ball, Kirstie S. 2001. “Situating Workplace Surveillance: Ethics and Computer Based Performance Monitoring.” Ethics and Information Technology 3 (3): 211–223. doi:10.1023/A:1012291900363

- Ball, Kirstie. 2010. “Workplace Surveillance: An Overview.” Labor History 51 (1): 87–106. doi:10.1080/00236561003654776

- Ball, Kirstie, MariaLaura Di Domenico, and Daniel Nunan. 2016. “Big Data Surveillance and the Body-Subject.” Body & Society 22 (2): 58–81. doi:10.1177/1357034X15624973

- Barry, Michael, and Adrian Wilkinson. 2011. “Reconceptualising Employer Associations Under Evolving Employment Relations: Countervailing Power Revisited.” Work, Employment and Society 25 (1): 149–162. doi:10.1177/0950017010389229

- Carr, Nicholas. June 2020. Not Being There: From Virtuality to Remoteness 2020 [cited 31 December June 2021]. http://www.roughtype.com/?p = 8824.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Clark, Bethany. 2019. Surveillance in the Workplace. Rigby Cooke Lawyers 2019 [cited September 2020]. https://www.rigbycooke.com.au/surveillance-in-the-workplace/.

- Dardot, Pierre, and Christian Laval. 2013. The New Way of the World: On Neoliberal Society. Translated by Elliott Gregory. London: Verso.

- Dean, Mark, and John Spoehr. 2018. “The Fourth Industrial Revolution and the Future of Manufacturing Work in Australia: Challenges and Opportunities.” Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 28 (3): 166–181. doi:10.1080/10301763.2018.1502644

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Masumi. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- De Vaujany, François-Xavier, Aurélie Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, Iain Munro, Yesh Nama, and Robin Holt. 2021. “Control and Surveillance in Work Practice: Cultivating Paradox in ‘New’ Modes of Organizing.” Organization Studies 42 (5): 675–695. doi:10.1177/01708406211010988

- Elliot, Adjeley Maude Ashong, and Reginald Arthur. 2020. Organizational Justice: Does “It” Matter? Empirical Analysis of the Influence of Information Technology on Employee Justice Perceptions. In Advances in human factors and systems interaction: Proceedings of the AHFE 2020 Virtual Conference on Human Factors and Systems Interaction, July 16–20, 2020, USA, ed. Isabel Nunes, 83–89. Cham, SZ: Springer.

- Elmholdt, Kasper Trolle, Claus Elmholdt, and Lars Haahr. 2021. “Counting Sleep: Ambiguity, Aspirational Control and the Politics of Digital Self-tracking at Work.” Organization (London, England) 28 (1): 164–185. doi:10.1177/1350508420970475

- Floridi, Luciano. 2019. “Translating Principles Into Practices of Digital Ethics: Five Risks of Being Unethical.” Philosophy & Technology 32 (2): 185–193. doi:10.1007/s13347-019-00354-x

- Fors, Vaike, and Sarah Pink. 2017. “Pedagogy as Possibility: Health Interventions as Digital Openness.” Social Sciences 6 (59): 1–12. doi:10.3390/socsci6020059

- Fors, Vaike, Sarah Pink, Martin Berg, and Tom O’Dell. 2020. Imagining Personal Data: Experiences of Self-tracking. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Freeman, Jaimie Lee, and Gina Neff. 2021. “The Challenge of Repurposed Technologies for Youth: Understanding the Unique Affordances of Digital Self-Tracking for Adolescents.” New Media & Society, 1–18. doi:10.1177/14614448211040

- Gioia, Dennis A., Kevin G. Corley, and Aimee L. Hamilton. 2012. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1177/1094428112452151

- Greenberg, Jerald. 2011. “Organizational Justice: The Dynamics of Fairness in the Workplace.” In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol 3: Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization, edited by Sheldon Zedech, 271–327. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Hassard, John, and Jonathan Morris. 2021. “The Extensification of Managerial Work in the Digital Age: Middle Managers, Spatio-temporal Boundaries and Control.” Human Relations, 1–32. doi:10.1177/00187267211003

- Hatch, Mary Jo. 1993. “The Dynamics of Organizational Culture.” The Academy of Management Review 18 (4): 657–693. doi:10.2307/258594

- Hjorth, Larissa, and Sarah Pink. 2014. “New Visualities and the Digital Wayfarer: Reconceptualizing Camera Phone Photography and Locative Media.” Mobile Media & Communication 2 (1): 40–57. doi:10.1177/2050157913505257

- Hopkins, John, and Paul Hawking. 2018. “Big Data Analytics and IoT in Logistics: A Case Study.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 29 (2): 575–591. doi:10.1108/IJLM-05-2017-0109

- Jeffrey, M. Stanton. 2000. “Traditional and Electronic Monitoring from an Organizational Justice Perspective.” Journal of Business and Psychology 15 (1): 129–147. doi:10.1023/A:1007775020214

- Jensen, Nathan, Elizabeth Lyons, Eddy Chebelyon, Ronan Le Bras, and Carla Gomes. 2020. “Conspicuous Monitoring and Remote Work.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 176: 489–511. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2020.05.010

- Jeske, Debora. 2021. “Monitoring Remote Employees: Implications for HR.” Strategic HR Review 2 (2): 42–46. doi:10.1108/SHR-10-2020-0089

- Kolb, Darl G, Kristine Dery, Marleen Huysman, and Anca Metiu. 2020. “Connectivity in and Around Organizations: Waves, Tensions and Trade-offs.” Organization Studies 41 (12): 1589–1599. doi:10.1177/0170840620973666

- Konovsky, Mary A. 2000. “Understanding Procedural Justice and Its Impact on Business Organizations.” Journal of Management 26 (3): 489–511. doi:10.1177/014920630002600306

- Laker, Benjamin, Will Godley, Charmi Patel, and David Cobb. 2020. “How to Monitor Remote Workers – Ethically.” MITSloan Management Review 2: 1–5.

- Leonardi, Paul M, and Jeffrey W Treem. 2020. “Behavioral Visibility: A New Paradigm for Organization Studies in the Age of Digitization, Digitalization, and Datafication.” Organization Studies 41 (12): 1601–1625. doi:10.1177/0170840620970728

- Lupton, Deborah. 2016. The Quantified Self. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Lupton, Deborah. 2017. “Towards Sensory Studies of Digital Health.” Digital Health 3: 1–6. doi:10.1177/205520761774009

- Lupton, Deborah. 2020a. “Data Mattering and Self-Tracking: What Can Personal Data Do?” Continuum 34 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/10304312.2019.1691149

- Lupton, Deborah. 2020b. Data Selves: More-than-Human Perspectives. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Lyall, Ben, and Brady Robards. 2018. “Tool, Toy and Tutor: Subjective Experiences of Digital Self-Tracking.” Journal of Sociology 54 (1): 108–124. doi:10.1177/1440783317722854

- Lyon, David. 2018. The Culture of Surveillance: Watching as a Way of Life. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Manley, Andrew, and Shaun Williams. 2022. “‘We’re Not Run on Numbers, We’re People, We’re Emotional People’: Exploring the Experiences and Lived Consequences of Emerging Technologies, Organizational Surveillance and Control among Elite Professionals.” Organization 29 (4): 692–713. doi:10.1177/1350508419890078

- Marx, Gary T. 2016a. “Surveillance and Surveys: The Soft Interview of the Future.” Society 53 (3): 301–306. doi:10.1007/s12115-016-0017-5

- Marx, Gary T. 2016b. Windows Into the Soul: Surveillance and Society in an Age of High Technology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- McKinlay, Alan, and Ken Starkey. 1998. Foucault, Management and Organization Theory from Panopticon to Technologies of Self. London, UK: SAGE.

- Mennicken, Andrea, and Wendy Espeland. 2019. “What’s New with Numbers? Sociological Approaches to the Study of Quantification.” Annual Review of Sociology 45 (1): 223–245. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041343

- Mohelska, Hana, and Marcela Sokolova. 2018. “Management Approaches for Industry 4.0 – The Organizational Culture Perspective.” Technological and Economic Development of Economy 24 (6): 2225–2240. doi:10.3846/tede.2018.6397

- Moore, Phoebe V. 2018a. “On Work and Machines: A Labour Process of Agility.” Soundings 69: 15–31. doi:10.3898/SOUN:69.01.2018

- Moore, Phoebe V. 2018b. The Quantified Self in Precarity: Work, Technology and What Counts. Oxford, UK: Routledge.

- Moore, Phoebe V. 2018c. “Tracking Affective Labour for Agility in the Quantified Workplace.” Body & Society 24 (3): 39–67. doi:10.1177/1357034X18775203

- Moore, Phoebe V. 2021. “AI Trainers: Who is the Smart Worker Today?” In Augmented Exploitation, Artificial Intelligence, Automation and Work, edited by Phoebe V. Moore and Jamie Woodcock, 13–30. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Moore, Phoebe V., and Andrew Robinson. 2016. “The Quantified Self: What Counts in the Neoliberal Workplace.” New Media & Society 18 (11): 2774–2792. doi:10.1177/1461444815604328

- Nabatchi, Tina, Lisa Blomgren Bingham, and David H. Good. 2007. “Organizational Justice and Workplace Mediation: A Six-Factor Model.” The International Journal of Conflict Management 18 (2): 148–174. doi:10.1108/10444060710759354

- Newlands, Gemma. 2021. “Algorithmic Surveillance in the Gig Economy: The Organization of Work Through Lefebvrian Conceived Space.” Organization Studies 42 (5): 719–737. doi:10.1177/0170840620937900

- Nicolini, Davide. 2013. Practice Theory, Work & Organization. An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ötting, Sonja K., and Günter W. Maier. 2018. “The Importance of Procedural Justice in Human–Machine Interactions: Intelligent Systems as New Decision Agents in Organizations.” Computers in Human Behavior 89: 27–39. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.07.022

- Paré, Guy, and Michel Tremblay. 2007. “The Influence of High-Involvement Human Resources Practices, Procedural Justice, Organizational Commitment, and Citizenship Behaviors on Information Technology Professionals’ Turnover Intentions.” Group & Organization Management 32 (3): 326–357. doi:10.1177/1059601106286875

- Pink, Sarah, Shanti Sumartojo, Deborah Lupton, and Christine Heyes La Bond. 2017. “Mundane Data: The Routines, Contingencies and Accomplishments of Digital Living.” Big Data & Society 4 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1186/s40537-016-0062-3

- Richardson, Steven, and Debra Mackinnon. 2018. “Becoming Your Own Device: Self-tracking Challenges in the Workplace.” Canadian Journal of Sociology 43 (3): 265–289. doi:10.29173/cjs28974

- Robson, C. 2011. Real World Research. 3rd ed. West Sussex: John Wiley.

- Rose, Emily, and Nicole Busby. 2017. “Power Relations in Employment Disputes.” Journal of Law and Society 44 (4): 674–701. doi:10.1111/jols.12062

- Rossi, Matti, and John Lindman. 2014. “Identifying Opportunities for It-Enabled Organizational Change.” In Computing Handbook: Information Systems and Information Technology, edited by Heikki Topi and Allen Tucker, 508–518. Philadelphia, PA: CRC Press LLC.

- Rupp, Deborah E., and Russell Cropanzano. 2002. “The Mediating Effects of Social Exchange Relationships in Predicting Workplace Outcomes from Multifoci Organizational Justice.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 89 (1): 925–946. doi:10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00036-5

- Sewell, Graham. 1998. “The Discipline of Teams: The Control of Team-based Industrial Work Through Electronic and Peer Surveillance.” Administrative Science Quarterly 43 (2): 397–428. doi:10.2307/2393857

- Smith, Gavin J. D. 2018. “Data Doxa: The Affective Consequences of Data Practices.” Big Data & Society 5 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1186/s40537-017-0110-7

- St-Pierre, Isabelle, and Dave Holmes. 2010. “The Relationship Between Organizational Justice and Workplace Aggression.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 66 (5): 1169–1182. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05281.x

- Stein, Mari-Klara, Erica L. Wagner, Pamela Tierney, Sue Newell, and Robert D. Galliers. 2019. “Datification and the Pursuit of Meaningfulness in Work.” Journal of Management Studies 56 (3): 685–717. doi:10.1111/joms.12409

- Subašić, Emina, Katherine J. Reynolds, John C. Turner, Kristine E. Veenstra, and S. Alexander Haslam. 2011. “Leadership, Power and the Use of Surveillance: Implications of Shared Social Identity for Leaders’ Capacity to Influence.” The Leadership Quarterly 22 (1): 170–181. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.014

- Sumartojo, Shanti, Sarah Pink, Deborah Lupton, and Christine Heyes La Bond. 2016. “The Affective Intensities of Datafied Space.” Emotion, Space and Society 21: 33–40. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2016.10.004

- Trittin-Ulbrich, Hannah, Andreas Georg Scherer, Iain Munro, and Glen Whelan. 2021. “Exploring the Dark and Unexpected Sides of Digitalization: Toward a Critical Agenda.” Organization 28 (1): 8–25. doi:10.1177/1350508420968184

- Veen, Alex, Tom Barratt, and Caleb Goods. 2020. “Platform-capital’s ‘App-etite’ for Control: A Labour Process Analysis of Food-Delivery Work in Australia.” Work, Employment and Society 34 (3): 388–406. doi:10.1177/0950017019836911

- Villadsen, Kaspar. 2017. “Constantly Online and the Fantasy of ‘Work-Life Balance’: Reinterpreting Work-Connectivity as Cynical Practice and Fetishism.” Culture and Organization 23 (5): 363–378. doi:10.1080/14759551.2016.1220381

- Woolgar, Steve, and Daniel Neyland. 2013. Mundane Governance: Ontology and Accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. 2015. “Big Other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects of an Information Civilization.” Journal of Information Technology 30 (1): 75–89. doi:10.1057/jit.2015.5