ABSTRACT

In this paper, we share with the reader our individual and collective experience of a reading circle organised during the pandemic, at a time of social distancing. The collective reading allowed ‘us’ to become-with other humans, non-humans, and more-than-humans with the materiality of different bodies. The reading circle allowed individual vulnerability to be shared in a process of becoming-together a multiple ‘Author’ who authored a ‘Composition’. We thus propose to the reader a Composition, in which we experiment with an embodied process of writing, where a drawing and words are mingled in-between poesy and prose. In their being intertwined, reading- and writing-together enabled a different ‘academicity’, emerging as an alternative to an individualistic experience of the neo-liberal Academia.

Writing follows life like its shadow,

extends it, hears it, engraves it.

(Hélène Cixous, Rootprints)

Introduction

The reading circle we are going to tell you about originated from the impossibility of physically meeting at work during the academic year 2020–2021 due to the spread of COVID-19. The initiative was led by one of the authors wishing to turn this material constraint into an occasion to meet and think-with colleagues at the department of Organization and Management at Mälardalen University, Sweden, as well as with other scholars interested in joining. The main purpose was to create a new ‘meeting place’ in circumstances requiring distancing and, eventually, to turn an impossibility into an impossibilityFootnote1 – as we want to write it to remember that vulnerabilities and threats (like those a pandemic exposes us to) can generate opportunities and encounters. In other words, this impossibility descends from an affective tension and from a situated, embodied intention to keep generating and circulating knowledge within an academic community despite living in times of crises, of ‘staying home’, ‘social distancing’, ‘staying-together-apart’.

Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus (1980/1987) was the ambitious oeuvre we approached together – the initiative was designed to support a collective exploration of its main concepts. Since its inception, the reading circle had revolved around individual reading and collective discussion. Both are scholarly (embodied and situated) practices often taken for granted in the academic context; practices that precede any writing and, hence, are key in Academia. However, it often happens that academic reading and academic writing are conceived as separated and solipsistic practices, inscribed into a competitive framework, and legitimised by a final, possibly ‘excellent’, output: a publication. What we are going to tell you about in the next few pages, has widely overcome such academic individualism and, as we will say later in the text, turned out to be an affective experience of togetherness not defined by the output. We did not engage in writing this article for the sake of publishing but, rather, we have been writing to honour our collegial embodied experience. We would not describe the reading circle as a study circle in that it was not driven by a ‘cognitive’ or ‘instrumental’ motivation to produce some sort of objective knowledge to transfer into specific working practices (for example, a research project or a teaching activity), but it was aimed at bringing forth some form of presence, connection, and solidarity during the pandemic.Footnote2

As taking place at a peculiar (pandemic) time, it was clear to all of us that engaging in such an experience would entail confronting a complexity that, eventually, we all became accustomed to and have generously embraced. However, it is too early to disclose the end of our story. Let us just mention that the complexity we have experienced has brought a process of becoming-together with other humans, non-humans, and more-than-humans: first of all, the book in its digital or analog edition, then pen and paper, computers and cameras, phones and headphones, along with other technical apparatuses, objects, and participants’ animal companions, as well as spaces and places distributed across disciplinary, organisational, temporal (i.e. different time zones) and geographical boundaries. It has been an emergent process of connecting affectively, which has led the above-mentioned heterogeneity of actors to become an assemblage of various materials that have transformed each other while interacting in the reading circle.

The invitation to join the reading circle spread beyond the department of Organization and Management by reaching scholars at a different stage of their careers – early career scholars as well as senior researchers – at Mälardalen University, but also at universities in Finland and Italy. Our diversity enabled us ‘to think and feel, to be males and females, junior or senior without censor’ (Mandalaki Citation2021, 1019). The gathering’s attendance was never constant but ranged from five to thirteen participants. Indeed, presence was not stated as being mandatory: inclusiveness and openness were the qualifying principles.

The invitation to join was initially accompanied by a document explaining how the reading circle would be run. In this document, five roles (facilitator, summariser, word master, passage person, connector) and related tasks were introduced to organise the discussion. However, it became clear during the first meeting that this structure was nothing but constraining. A collegial decision to not carry on with this structure was made, but a shared calendar was kept. We decided that the reading circle was to take place online, once a month, on Friday afternoons, for one hour, and always at the same time (12:15–13:15 CET). People willing to participate were invited to read one specific chapter before each meeting. In this way, the reading circle ran between October 2020 and March 2022 (summer breaks excluded, for a total of 15 meetings, each corresponding to one chapter). The initial calendar was scheduled until June 2021, with a question attached to the calendar invite for the last meeting: ‘To be continued?’. What happened afterwards is probably less important than telling you what happened over the course of the meetings.

In the next pages, we will reflect on the experience of reading together and reading through the experience of those scholars who read and wrote before us. Reading is never an isolated activity. Even when we open a book, others are already present in our reading. More importantly, reading is an activity conducted on the shoulders of giantsFootnote3, never conducted in a vacuum but rather influenced by authors who have written before us. Reading is thus connecting with those who have read in the past – in a sense it is connecting with our literary ancestors, as well as our colleagues while projecting us into the future. Our reading, as any other reading, is historically as well as technologically located. If in a near future we go back to the same book, our reading will not be the same. Furthermore, reading enacts an affective experience that is connected to other similar experiences. Our reading circle becomes like a jewel set in other reading circles. The process, put in motion by reading together, brought to the fore the desire to write, thus transforming the readers into writers. The embodied experience of reading and writing produced creative work in the form of what we call a ‘Composition’ that is presented in the third section of this article, together with a drawing that should be considered part of the composition in which drawing, writing, prose, and poetry form an indivisible whole. As in the art of creating a musical piece, melodies are woven together to form a whole (i.e. composition). The etymology of composition comes from the Latin cum – with, together – and ponere – to place. Composition is thus the act or process of composing, and how a thing is arranged into specific proportion or relation and especially into artistic form. Kathleen Stewart writes about compositional theory as ‘the form of a sharply impassive attunement to the ways in which an assemblage of elements comes to hang together as a thing that has qualities, sensory aesthetics and lines of force and how such things come into sense already composed and generative and pulling matter and mind into a making: a worlding’ (2014, 119).

Then, we – a multiple Author in its becoming – share some of the most embodied and affective meanings of the reading circle, while moving from reading to writing. In the discussion, we position our embodied collective experience in Academia as a possibility for a different ‘academicity’ (Brunila Citation2016), meaning that the becoming of a professional self is a process through which we become culturally intelligible academics and position ourselves in academic practices. In the conclusion, we highlight two contributions that the article offers to the ‘writing differently’ movement. The first is the neologism readingwriting that stresses the circularity between the two practices and the second is the aesthetic experience of the musicality materialised in the Composition, a form of writing in which design, prose, and poetry are mingled.

Becoming together with different reading circles

Reading circles, reading groups, literature circles, book clubs … when browsing what has been written previously about reading circles, we realised that there are many names used to describe the phenomenon of a small number of people regularly meeting up to discuss a book that they all (are expected to) have read (Brabham and Villaume Citation2000; Peplow Citation2011). Our reading confirmed what some of us already suspected: that over the past 30 years reading circles seem to have become increasingly more common (Peplow Citation2011). One possible explanation for this is that the gatherings need no longer take place in real life – a reading circle can, as in our case, also convene online (Porath Citation2018). We found that the literature on reading circles seemed, however, to primarily view reading circles from an instrumentalist perspective.

In education, reading circles are often ‘used’ in a more or less structured form (Begoray and Banister Citation2007; Falk and Dierking Citation2002; Railton and Watson Citation2005) for various social and pedagogical benefits (Cremin and Swann Citation2016; Cumming-Potvin Citation2007; Parrott and Cherry Citation2011). Reading together has for example been shown to lead participants to form positive social associations with reading (Bloome and Kim Citation2016) and students feel they read the books ‘more deeply’ compared to when they read on their own (Çetinkaya and Topçam Citation2019).

Similarly, literature provided examples of an instrumental view on reading circles from other areas than education. Amongst groups of professionals, for example medical doctors or nurses, the reading circle is said to be useful not only to promote professional praxis (Lyons and Ray Citation2014); learning and growth (Jordan et al. Citation2020; Kooy and Colarusso Citation2014); professional identity and a positive attitude towards the profession (Çetinkaya and Topçam Citation2019; Ho et al. Citation2022), but also to provide the possibility to better understand the community the professionals serve (Begoray and Banister Citation2007; Goldberg and Pesko Citation2000). Furthermore, reading circle literature suggests various formats of the reading circle that have been used to foster personal development, for example as part of therapy for people in mental distress (Shipman and McGrath Citation2016), or among prisoners, where the reading circle has proven to provide a space where the individual prisoner is able to deal with emotionally difficult topics together with others facing similar issues (Billington Citation2011; Hartley Citation2020; Nolan Citation2020). With benefits like these it is no wonder that reading circles are valued instrumentally!

But whereas it seemed to us as if the literature is replete with examples of when the reading circle has been used instrumentally, for a particular purpose, we also found studies that strengthened us in our thinking that the reading circle cannot – and should not – be reduced to an instrument.

Some of this literature suggests that the coming together to discuss a shared reading has a value in itself. Often in this literature, the ‘Salons’ organised in Early Modern Revolutionary France are mentioned. These were reading circles where members of the bourgeoisie met to discuss recently published texts, and as the reader of this text may remember from her History-classes in school, the Salons are commonly said to have played an important role for France’s cultural and intellectual development – and they also inspired the middle class in other countries to organise similar gatherings. In the Salons, the discussion of joint readings took place in a domestic setting; a setting that had feminine connotations since the salons were often organised by and attracted women who, through the reading circle, were able to form their own spaces and communities (Hartley Citation2020; Kiernan Citation2011; Long Citation2003; Rehberg Citation2011; Sedo Citation2003).

Reading this literature, we found support for our own experiences of the reading circle not merely being an autonomous and individual process with benefits for each individual participant (Street Citation1984), but a social process (Bloome Citation1985; Swann and Allington Citation2009). If reading is always reading with others, as we stated in the introduction, a reading circle is an explicit committed social practice (Allington and Swann Citation2009). Just as members of other reading circles (Shipman and McGrath Citation2016), we perceived that the reading performed alone prior to the convening of the reading circle was an instance of reading together intimately tied to our reading during and after our gatherings.

From this perspective, it makes sense to describe the reading circle as an ‘intersubjective dialogic process’ (Álvarez-Álvarez Citation2016, 228) amongst us that participate. In the reading circle, an interpretative community is formed, where the meaning of the text is negotiated between the participants (Fish Citation1980). Looking at previous literature on reading circles, it also seems to us, that a key to the possibility of such a community emerging is the non-hierarchical set-up of the reading circle. This encourages active participation (McCall Citation2010), making the reading circle a site for joint intellectual curiosity (Long Citation2003) – we would add affective curiosity too – and provides a space for us, the participants, to engage in collective inquiry (Beach and Yussen Citation2011) which is multidimensional.

When reflecting upon the reading circle from this perspective, the social practice of reading together is about enjoying with others a joint exploration of a written piece (Hartley Citation2020), not for the heeding of particular social and intellectual expectations concerning literature (Nolan Citation2020), but as a way to enable conversations that matter to us as participants (Cameli Citation2020). Of course, by engaging in this process, we do engage in processes of cultural transfer whereby values, norms and ideas are (re)constructed (den Toonder, Saskia, and van Voorst Citation2017). Reading together may be described as a ‘powerful coalescing presence’ (Hodge, Robinson, and Davis Citation2007, 102), whereby common frames of references (Shipman and McGrath Citation2016) and other social bonds are constructed (Long Citation2003). But this is a process that not only takes place on an intellectual level. It also involves, as King, formulates it, ‘affective responses […] which would otherwise remain dormant’ (2002, 32).

When we engage in this social practice with all of ourselves, community is fostered (Chisolm et al. Citation2017). This is not to say that all participants of all reading circles are always in concord. We certainly weren’t. Participants in reading circles may have severe difficulties understanding each other, especially if not belonging to the same community initially (Poyas and Elkad-Lehman Citation2022). But in the process of reading together, something happens, and this something can potentially give rise to action, which is why reading circles have been said to be interesting sites for learning about the emergence of social processes (Greiner et al. Citation2021) or, as Bozalek (Citation2022) has experienced, sites for responding to and playfully experimenting with the text.

For us, the reading circle was an opportunity to read, think, and feel together. And, later on, it also became about writing together. In a moment, we will share this writing with you. We write ourselves – about our reading together and the experiential and affective meaning of our reading – and we put ourselves into a poetic Composition in an open-ended process of becoming-with. But first, some reflections about how our composition came to be.

Becoming embodied writing

Similar to the practice of reading, writing too can be an affective practice: a practice where our ‘leaky bod[ies]’ (Pullen Citation2018, 128) our ‘feeling fingers’ (Mandalaki Citation2021, 1019) and our ‘lips […], in their plurality’ (Ahonen et al. Citation2020, 454) no longer need to be hidden behind the curtains. An increasing number of organisational scholars are paving the way by exposing vulnerability when writing about our insecurities (Jääskeläinen and Helin Citation2021), our shame (van Amsterdam Citation2015), or our grief (Boncori and Smith Citation2019; Katila Citation2019; Kivinen Citation2021). Standing in contrast to the traditional, rigorous, masculine conventions and forms of understanding in Academia, this sort of writing is highly embodied.

Embodied writing expresses the visceral and sensual forms of knowledge production, the aesthetic perceptions often mediated through art-based forms of communication (Biehl-Missal Citation2015). It is an intimate experience that holds a promise of collectiveness, of ‘being together in our textual as well as our broader academic encounters’ (Mandalaki Citation2021, 1009). Our writing, whether written by one or more writers is, as Pullen (Citation2018) illustrates, not an isolated activity. When writing through our bodies, we do it in relation to other possible bodies, whether they are present or imagined. Moreover, embodied writing does not presume a single author writing about a personal experience; on the contrary, often these texts have been collectively written (see for example Huopalainen and Satama Citation2019; Jääskeläinen and Helin Citation2021). Writing together has the potential of converting ‘individual and collective struggles […] into words’ (Ahonen et al. Citation2020, 484). The process of collective and emerging experimentation can bring together different voices in a way that blurs the boundaries between me, you, and us. Hence, embodied writing is an engagement of care for and with each other (Mandalaki Citation2021).

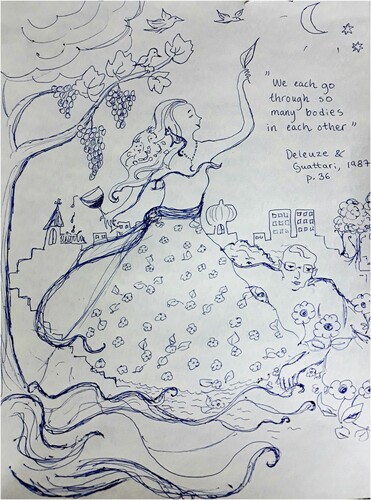

Our Composition is a piece of embodied writing, emerging from bodies in connection. It blossomed out of a long and slow process of reading together. During and after our reading, we wrote individual reflections, which we then shared with each other. Reflections met and reflections clashed. Lines were not in perfect accord with each other, instead, they were affective outbursts of various emotions and exposed vulnerabilities. We experimented with thoughts through words but also through a drawing (), communicating what words were unable to express at that particular moment. The reflections were written for us in the reading group, and there was initially no intention to publish them. Hence, there was no need to worry about whether the language was ‘good enough’ or if any references were inserted in their proper format. Rather, our reflections were liberating acts of struggle, to make sense of our shared reading.

Figure 1. Going Through, a sketch by Laura JaramilloFootnote4 (2021).

With our individually written reflections in front of us, our eyes were caught by a multiplicity of voices. When reading through them, we could feel each other. Tuning in, moving from one to another, breathing everyone’s breath, lines became connected. In this process, the individual differences faded as our multiplicities turned into a diverse whole. A Composition had taken form and musicality by melting feelings and thoughts.

A Composition: the inner musicality of writing about reading

In the beginning, there was reading for myself …

When I was a child, I was very shy

and the world ‘out there’ was sometimes simply too noisy, sometimes too boring,

to deal with.

Books soon came to me, and they were my refuge: the ‘room’ of my own, where no one was

asking me to speak gently or behave well.

It was just me and an overwhelming uplifting sense of freedom of being myself, of crying or

laughing, pausing, or jumping, getting away or staying focused.

… And there was reading in the sun,

something I love deeply and that gives me the sense of summer,

a sensory experience that takes my whole body.

I cannot really comment on what I read,

but I perfectly remember the heat of the sun on my body and belly

because I was lying down, and the heat from the sky took me

but also reverberated from the dark colour of the rock that held the heat of the sun.

It was an erotic experience,

but I cannot say that the book was erotic in any sense!

… And there was reading, always with a pen in my hand.

The writing and drawing make the reading part of a craft; I use my hands.

I feel the (light) weight of the pen, pencil or stylus in my hand, the friction of the nib of the pen or pencil on the page, or the smoothness of the stylus on the digital screen.

The pages become colourful and different from each other.

No one page looks the same.

All my reading alone,

whether at the beach, on my couch, on the bus, on the train, or wherever I am,

happens along with my packs of Post-its, a couple of pens, and my trusted notebook.

As I read, I take notes, I write, and in my hand tires as I scribble.

My holidays always entail me bringing a couple of Post-its, my notebook,

and a book or two.

If I were Alfred Kiefer,

I would do a gigantic sculpture of my body, made up of piled-up lead books

and dream of the constant alchemical transmutation of matter.

In that dream, anything is possible.

I can become the moon if I like, or birds flying towards it.

Books have helped me to develop an inner sense of me

in all her multiple and layered vulnerability.

But acceptance comes slowly,

not without pain …

I find myself in unfamiliar territory, captured by doubt.

The statue I am building is

falling apart.

… I am not convinced.

I feel rejected by the words I have read.

Worse yet, I seem to not have found anything to grasp here.

I reached out for something but fear I have ended up empty-handed.

Eventually, I notice that I am turning my pages in frustration.

I have written notes and read until my right hand hurt.

I have understood something, I tell myself.

But I feel a creeping sense of doubt.

I have so much to read, and so much to understand.

How do others deal with this?

I was not enough anymore.

Books may turn reading into a line of flight

to let my individual vulnerability flourish

and populate my own room with Others.

Intensities start circulating all around

and we are on a different plateau.

We meet on our digital screens.

Fragments of multiple spaces

and multiple I’s connecting in a digital terrain.

We are reading together.

Struggling …

… And then we laugh.

In a way, it does not matter what we read.

A Thousand Plateaus is just a pre-text; the text we read is our reactions and the flow of conversation that the pre-text had set in motion.

The feeling of knowing that I am not alone and that if I do not understand I might learn from the rest or possibly feel a sense of camaraderie in my lack of understanding together with Others.

In fact, the reading circle has offered some sort of sanctuary, or shelter.

To and with my fellow explorers I can voice and share my frustration.

Together we contextualise and illustrate ideas and demystify concepts and quotes.

And as time goes by, I realise that my notetaking has gradually changed. The first chapter is full of notes to myself. In the following chapters, I see more question marks. The questions are not only ‘What does this mean?’ but also questions to Others. ‘Do you agree?’ ‘What do you think?’

I am writing to someone.

Small invitations for someone to respond. To interact.

I am not writing in isolation,

actually, ‘I am constantly imagining you in front of me’ (Pullen Citation2018, 123).

Your words connect with my words. Our words connect with others.

We are playing Ping Pong.

It is the sound of alternating comments, basically saying

‘it might be like this or it might be otherwise’

There is nothing to prove.

It is the most liberating feeling.

Philosophical concepts are not meant to be pinned down to any single meaning,

rather they should reverberate in different contexts, different situations

when they are put to use

and sent back to another player.

We meet again in our square digital boxes to exchange thoughts.

The discussions are lively, but I often find myself being surprisingly quiet.

My thoughts resemble abstract lines, unable to be articulated at the moment.

Instead, I listen.

I am drawing as I listen.

Drawings mix with lines of words as the pen is moving with my hand.

Thoughts are put aside in favour of creation.

I wish to form ‘true repetition in existence rather than an order of resemblance in thought’ (Deleuze Citation1968/Citation1994, 13).

The Italian waters shimmering in the background as we speak mix with the sounds of traffic from city life in Stockholm and trees calmly dancing in the wind in a Finnish forest. A new assemblage is taking form, becoming central to our reading experience – and as we speak it feels like ‘any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be’ (Massumi in Deleuze and Guattari Citation1980/Citation1987, 7). We have deterritorialised the book from its covers by drawing new lines, supplementing it with the text of our situated selves – a circular time, which from one plateau to another has linearity that goes both forward and backward and on parallel and crossed planes.

We have been reading together

and we are living that knowledge on our skin,

still.

We have been fascinated and curious.

We have also been frustrated, angry, and unsure of ourselves.

We have exposed ourselves to each other, sharing our vulnerabilities, instead of

hiding them away.

It is not easy to name our pain,

to make it a location for theorising (hooks Citation1994)

… But we feel that we should give it a try.

Becoming-with people, texts, materials, and discourses

In the drawing that opens the previous section, and that Laura sketched during one of our meetings, there is an inscription from Deleuze and Guattari: ‘we each go through so many bodies in each other’ (Citation1980/Citation1987, 36). It was only in re-reading the text, collectively assembled as a Composition, several times, that we fully understood that it performs ‘us’ as a single and multiple Author. Our individual words and experiences have been mingled and now it is this Composition that materialises our embodied beings and the flow from one body to another, and another, and another … again. Words come in written form, from different hands, and it is the rhythm of the Composition which is intended to produce an affective effect in touching an audience. The words of the Other touch the being of the One, and are together morphed in the writing process until they materialise a multiple and indistinguishable Author. It is symbolic transformative touch (Hancock, Sullivan, and Tyler Citation2015) that makes our academic writing ‘naked’ and attuned with an onto-epistemological relational stance of knowing that allows us to enhance and appreciate vulnerability instead of hiding it behind conventional ‘knowledge production practices’ (Meriläinen, Salmela, and Valtonen Citation2022). The Author of the Composition is naked and, thus, exposed to embodied human and non-human alterity accompanying and transforming the writing in its becoming.

Bodies and words are entangled in an irreversible process of becoming-with alterity. This process brings the traces of the past; it has a present form in the actual Composition; and it will, in the future, continue to become-with the readers’ individual activity of reading it and through it entering the experience of the multiple Author appropriated through their own experience both as individuals and as individuals living in Academia. This process leads to the recognition of alterity as necessary to the manifestation of the self (Ferrando Citation2020); also, the process brings along ethical responsibilities to think otherwise and account for the entangled materialisation of all bodies and their agential contributions (Barad Citation2007) to the becoming of the Composition.

Through the Composition, the multiple Author enacts a ‘presence’ in the Academia and performs the possibility of a different ‘academicity’ (Brunila Citation2016). The concept of ‘performing academicity’ stresses how the becoming of a professional self is a process where being a culturally intelligible academic is ‘understood as a citational and reiterative discursive practice within multiple and contradictory power–knowledge relations’ (Brunila Citation2016, 386). We add that it is not only a discursive process but historical and material as well. It is about enacting and materializing ‘entanglements of the past/present/future histories’ (Bozalek Citation2022, 558) and has important consequences in the shaping of the academic subject and in what stories he (sic) tells other stories with to make worlds (Haraway Citation2016).

The Composition allowed performing a different academicity as embodying ‘a style of connected thinking and writing that troubles the predictable academic isolation of consecrated authors by gathering and explicitly valorizing the collective webs one thinks with, rather than using the thinking of others as a mere ‘background’ against which to foreground one’s own’ (Puig de la Bellacasa Citation2012, 202). The multiple Author emerged in intra-actions of thinking and knowing with care, at a pandemic time of inescapable troubles.

The context created by COVID-19 impacted on us as academics blurring the boundaries between public and private, work and home, working activities and leisure and our academic practice of reading together was transversal to those boundaries. We were not reading only instrumentally, nor only for pleasure, rather we were affirming and defending a positive space for intellectual curiosity. In reading together, a powerful coherence principle is enacted; a principle which testifies to a way of doing academicity as a collective presence, linking the personal and the professional, being colleagues and being friends, valuing reciprocal trust and collaboration over competition and productivity enhancement. It is a transgressive presence, both because it crosses several boundaries and because it does not respect, nor reproduce, the canons of the neo-liberal Academia, and the social conventions of professional orthodoxy. Performing academicity differently is not only the activity of reading alone-together – in the socio-professional context of those (persons and books) who did it before us and will do it in the future – it is also differing difference in reading across space and time (Deleuze Citation1968/Citation1994) or, in Barad’s words, across ‘differentiatings of spacetimemattering’ (Citation2007, 179). Differing reading does not occur in evenly spaced individual moments (time); it does not take place in a fixed spatial geometry of pre-existing points (space); finally, it does not unfold through individually articulated or static, immutable or passive entities (matter/ing). Differing reading cuts across individual embodied vulnerabilities that, in being exposed, become a shared vulnerability that releases a liberating affirmative force, able to free us from the burden of social distancing, academic expectations, and the slavish attribution of ‘the right interpretation’ when reading a book. Echoing other scholars’ stories like ours, we similarly appreciate that ‘[t]he reading circle was created as a safe space where voicing anxieties without fear of being ridiculed was supported’ (Meriläinen, Salmela, and Valtonen Citation2022, 80) and, yet, ‘[b]eing part of a collective allowed for feeling safe enough to take risks and write differently in a conventional academic context’ (Van Amsterdam et al. Citation2023, 4).

We read texts and texts read us. Moreover, in digital Zoom-connections we read the placeness of the con-text of texts. We read and intra-act with the materialities of the reciprocal physical rooms, we open to each other private spaces and the narratives inscribed in the objects in the rooms, we see the choices of different home places for connecting; we see how the weather changes the light of the room, and how weathering colours the Zoom-connections. The con-text of the text was also formed by glasses of water, cups of tea, non-human animal companions passing by or heard in the distance; by faces more or less tired, and more or less animated by the discussion. All different materialities are present, taking an active part in putting a text in its con-text, both in the past, when we were connecting through a communicative technology such as Zoom, and in the present, when a hypothetical reader will approach this article and translate it into his/her/their material world.

Reading is thus corporeal. To be precise, it is an affective way ‘of being inter-corporeally together in our field and writing practices’ (Mandalaki and Pérezts Citation2022, 598). It is a social and professional practice involving things, places, atmospheres, other Others, imagined smells and tastes that are excluded by the technological medium but that are re-created in and by the unfolding sense of intimacy. Reciprocal trust emerges from doing things together, and from it the desire of ‘making’ something together leads some participants of the reading circle from reading to writing. Hélène Cixous (Citation1993, 21) has pointed out that ‘writing and reading are not separable, since reading is a part of writing, and since a ‘real’ reader is already on the way of writing’. In the Composition we offer to the reader, our writing is hence both a writing from our bodies and an ethical practice of caring for our community.

Closing as contributing

This article is a multi-layered text. It has first a confessional story, written in a personal tone and inviting the reader to join a collective experience of reading together in order to overcome the social distancing imposed by the unusual time of COVID-19. The rhetoric of this layer of writing is inscribed in the text in order to persuade the reader that reading is a social and academic practice and that in reading we go through a transformative process that connects our historicity with all reading circles taking place before ours as well as with texts embodied in our reading of a specific one (i.e. Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus): we read it with and through multiple previous readings. Also, we recognise a reading circle as a professional practice affecting us as situated readers experiencing the impossibility of a different ‘academicity’.

A second layer of writing is constituted by experimenting with creative writing and giving form to a Composition, in which the distinctions between drawing and writing, poems and prose, individual and collective authoring are blurred. As in letting oneself go to a musical composition, the readers are invited to immerse themselves in the rhythm of our Composition, indulge in the pleasure of looking at a delicate design, and follow different melodic lines. The rhetoric of this layer of writing is meant to persuade the reader that reading is an aesthetic endeavour that mirrors our writing as a collective and embodied experience. We aimed to reach out to touch and move the reader as much as we incorporated our ideal reader as an interlocutor into the text.

In the third layer of the article, a different register is activated, and there we assume the posture of the multiple Author who theorises on the oeuvre and makes explicit the contributions it offers, not only to the special issue but to the ‘writing differently’-movement.

A first contribution has the form of an invitation to consider the neologism readingwriting as a new concept that blurs the boundaries between what are considered as two separate academic practices. In so doing the desire that connects the two activities may come to light. As a matter of fact, reading and writing can be considered two separate activities if we look at their different accomplishments, however they are not separate when we consider the circularity of desire that touches our bodies, our reading bodies are affected by the aesthetics of readingwriting and feel the anticipated desire to touch other bodies and move them.

In order to articulate better what desire does in readingwriting, we recall the powerful metaphor of skin writing that Brewis and Williams (Citation2019) have elaborated to account for the two drives present in the reality of our organised lives. One force is constituted by the experience of sharing internal lived experience, and the second by the desire to externalise and abstract. Can they be brought into contact? We have experienced how the genesis of our Composition was deeply inscribed in the desire to express our lived experience in Academia in a peculiar time and how we were writing for the pleasure of experimenting with writing without having in mind to open the Composition outside us, the readerwriters. Writing is the desire that comes from reading, and it is the anticipation of the desire to be read, a desire to transgress the boundaries of the skin, to step out of the ‘private’ text and stretch out to touch the reader in a movement of circularity of desire. The way in which we have been moved by the text circulates and moves out to touch the readers, to get under their skin.

The second contribution is an invitation to let go of the grip of rationality and surrender to the aesthetic experience of our Composition. We composed it affectively and emergently and now we are reaching out to you, the reader, and getting under your skin to transport you into the realm of drawing, poetry, and musicality. The Composition is not done to be understood but to be sensed. It aims to elicit aesthetics by knowing with the senses and feeling the rhythms inscribed in words. The Composition is an embodied and affective writing about reading which celebrates the passion and the ordinary beauty of reading. In being read by you, the reader, the circularity of the transmission of affect closes in on itself.

Can we, organisation studies scholars, learn to write more creatively and gain something new from experiencing readingwriting? This article gives a positive answer to that question, arguing that we may gain an aesthetic awareness of the materiality and corporeality implied in the way we reach out to other authors and other readers. Language is material and we are bodies that experience the pleasure of looking at words and lines, smelling the paper or blinking at the brightness of the screen. Maybe we are eating something juicy while reading and sinking into a comfortable old sofa which envelops our bodies. Maybe we will put more care in how we write if we consider that the books we read and the books we write go deeper under our skin and into our corporeality. We are the books we have read, and we touch other bodies with our books, our words, and our imagination – or lack of it. If we keep that in mind when we write, then we keep in mind all the Others that we do not know, but we reach out to.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank David Ashby who proofread our article and suggested the very last sentence. It seems to us as if he felt embraced by our Composition and we embraced him in it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This rhetoric device is in debt to Jacques Derrida’s method (1976) of writing called sous rature (in English: ‘writing under erasure’) – borrowed from Heidegger. It consists of writing a word and crossing it out to highlight that the word is necessary for communication but yet not sufficient for conveying the intended meaning one can carry by writing it sous rature instead. Here, we want to stress the morphing of an actual impossibility into a concrete possibility without escaping from or forgetting the constraining conditions from where the reading circle started. Hence, we keep the meaning of ‘possibility’ within the word ‘impossibility’.

2 This is not to say that a ‘study circle’ cannot be initiated with the same purpose as our reading circle. Indeed, Susan Meriläinen, Tarja Salmela and Anu Valtonen (Citation2022) give a beautiful account of their experiences of exploring vulnerable relational knowing, in the context of a study circle. In our case, though, we did not convene with the explicit purpose of ‘studying’, but of reading together.

3 In a letter to Robert Hooke in 1675, Isaac Newton, made his most famous statement: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants”. This statement is now often used to symbolise scientific progress. Robert Merton examined the origin of this metaphor in his On the Shoulder of Giants (Merton Citation1965). The shoulder-of-giants metaphor can be traced to the French philosopher Bernard of Chartres, who said that we are like dwarfs on the shoulders of giants, so that we can see more than they, and things at a greater distance, not by virtue of any sharpness of sight on our part, or any physical distinction, but because we are carried high and raised up by their giant size.

4 We wish to acknowledge the help we received from Antonio Strati in the graphical rendering of the image, originally a pen drawing on paper.

References

- Ahonen, P., A. Blomberg, K. Doerr, K. Einola, A. Elkina, G. Gao, J. Hambleton, et al. 2020. “Writing Resistance Together.” Gender, Work & Organization 27: 447–470. doi:10.1111/gwao.12441.

- Allington, D., and J. Swann. 2009. “Researching Literary Reading as Social Practice.” Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics 18 (3): 219–230. doi:10.1177/0963947009105850.

- Álvarez-Álvarez, C. 2016. “Book Clubs: An Ethnographic Study of an Innovative Reading Practice in Spain.” Studies in Continuing Education 38 (2): 228–242. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2015.1080676.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Beach, R., and S. Yussen. 2011. “Practices of Productive Adult Book Clubs.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 55 (2): 121–131. doi:10.1002/JAAL.00015.

- Begoray, D. L., and E. Banister. 2007. “Learning About Aboriginal Contexts: The Reading Circle Approach.” Journal of Nursing Education, 324–326.

- Biehl-Missal, B. 2015. “‘I Write Like a Painter’: Feminine Creation with Arts-Based Methods in Organizational Research.” Gender, Work & Organization 22 (2): 179–196. doi:10.1111/gwao.12055.

- Billington, J. 2011. “Reading for Life’: Prison Reading Groups in Practice and Theory.” Critical Survey 23 (3): 67+. doi:10.3167/cs.2011.230306.

- Bloome, D. 1985. “Reading as a Social Process.” Language Arts 62 (2): 134–142.

- Bloome, D., and M. Kim. 2016. “Storytelling: Learning to Read as Social and Cultural Processes.” PROSPECTS 46 (3-4): 391–405. doi:10.1007/s11125-017-9414-9.

- Boncori, I., and C. Smith. 2019. “I Lost My Baby Today: Embodied Writing and Learning in Organizations.” Management Learning 50 (1): 74–86. doi:10.1177/1350507618784555.

- Bozalek, V. G. 2022. “Doing Academia Differently: Creative Reading/Writing-With Posthuman Philosophers.” Qualitative Inquiry 28 (5): 552–561. doi:10.1177/10778004211064939.

- Brabham, E. G., and S. K. Villaume. 2000. “Questions and Answers: Continuing Conversations About Literature Circles.” The Reading Teacher 54 (3): 278–280.

- Brewis, D. N., and E. Williams. 2019. “Writing as Skin: Negotiating the Body in(to) Learning About the Managed Self.” Management Learning 50 (1): 87–99. doi:10.1177/1350507618800715.

- Brunila, K. 2016. “The Ambivalences of Becoming a Professor in Neoliberal Academia.” Qualitative Inquiry 22 (5): 386–394. doi:10.1177/1077800415620213.

- Cameli, S. 2020. “A Different Kind of Book Club.” The Learning Professional 41 (1): 48–51.

- Çetinkaya, FÇ, and A. B. Topçam. 2019. “A Different Analysis with the Literature Circles: Teacher Candidates’ Perspectives on the Profession.” International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 7 (4): 8–16. doi:10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.7n.4p.8.

- Chisolm, M., A. Azzam, M. Ayyala, R. Levine, and S. Wright. 2017. “What’s a Book Club Doing at a Medical Conference?” MedEdPublish 7: 146. doi:10.15694/mep.2018.0000146.1.

- Cixous, H. 1993. Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Cixous, Hélène, and Mireille Calle-Gruber. 1997. Hélène Cixous, Rootprints: Memory and Life Writing. London, New York: Routledge.

- Cremin, T., and J. Swann. 2016. “Literature in Common: Reading for Pleasure in School Reading Groups.” In In Plotting the Reading Experience: Theory/Practice/Politics., edited by P. M. Rothbauer, K. I. Skjerdingstad, L. McKechnie, and K. Oterholm, 279–300. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Cumming-Potvin, W. 2007. “Scaffolding, Multiliteracies, and Reading Circles.” Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne de L'éducation 30: 483–507. doi:10.2307/20466647.

- Deleuze, G. 1968/1994. Difference and Repetition. Reprint. New York: Colombia University Press.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1980/1987. A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translation and foreword Brian Massumi. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press.

- den Toonder, J., M. V. Saskia, and S. van Voorst. 2017. “Cultural Transfer in Reading Groups: From Theory to Practice and Back.” Research for All 1 (1): 52–63. doi:10.18546/RFA.01.1.05.

- Derrida, J. 1976. Of Grammatology. Trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Falk, J. H., and L. D. Dierking. 2002. Lessons Without Limit: How Free Choice Learning is Transforming Education. Lanham, MD: Rowman Altamira.

- Ferrando, F. 2020. Philosophical Posthumanism. London: Bloomsbury.

- Fish, S. 1980. Is There a Text in This Class? Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Goldberg, S. M., and E. Pesko. 2000. “The Teacher Book Club.” Educational Leadership 57 (8): 39–41.

- Greiner, R. S., J. L. Callahan, K. Kaeppel, and C. Elliott. 2021. “Advancing Book Clubs as non- Formal Learning to Facilitate Critical Public Pedagogy in Organizations.” Management Learning 53 (3): 1–19.

- Hancock, P., K. Sullivan, and M. Tyler. 2015. “A Touch Too Much: Negotiating Masculinity, Propriety and Proximity in Intimate Labour.” Organization Studies 36 (12): 1715–1739. doi:10.1177/0170840615593592.

- Haraway, D. J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Hartley, J. 2020. “Twenty Years Behind Bars: Reading Aloud in Prison Reading Groups.” Changing English 27 (1): 100–108. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2019.1666251.

- Ho, J., S. Smith, E. Oakley, and N. L. Vanderford. 2022. “The use of a Book Club to Promote Biomedical Trainee Professional Development.” Heliyon 8 (1): e08675.

- Hodge, S., J. Robinson, and P. Davis. 2007. “Reading Between the Lines: The Experiences of Taking Part in a Community Reading Project.” Medical Humanities 33: 100–104. doi:10.1136/jmh.2006.000256.

- hooks, b. 1994. Teaching to Transgress. Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York, London: Routledge.

- Huopalainen, A. S., and S. T. Satama. 2019. “Mothers and Researchers in the Making: Negotiating ‘New’ Motherhood Within the ‘New’ Academia.” Human Relations 72 (1): 98–121. doi:10.1177/0018726718764571.

- Jääskeläinen, P., and J. Helin. 2021. “Writing Embodied Generosity.” Gender, Work & Organization 28 (4): 1398–1412. doi:10.1111/gwao.12650.

- Jordan, J., R. A. Bavolek, P. L. Dyne, C. E. Richard, S. Villa, and N. Wheaton. 2020. “A Virtual Book Club for Professional Development in Emergency Medicine.” The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 22 (1): 108–114.

- Katila, S. 2019. “The Mothers in Me.” Management Learning 50 (1): 129–140. doi:10.1177/1350507618780653.

- Kiernan, A. 2011. “The Growth of Reading Groups as a Feminine Leisure Pursuit: Cultural Democracy or Dumbing Down?” In Reading Communities: From Salons to Cyberspace, edited by Sedo D. Rehberg, 123–139. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- King, C. 2002. “I Like Group Reading Because we Can Share Ideas’: The Role of Talk Within the Literature Circle.” Literacy 31 (1): 32–36.

- Kivinen, N. 2021. “Writing Grief, Breathing Hope.” Gender, Work & Organization 28 (2): 497–505. doi:10.1111/gwao.12581.

- Kooy, M., and D. M. Colarusso. 2014. “The Space in Between: A Book Club with Inner-City Girls and Professional Teacher Learning.” Professional Development in Education 40 (5): 838–854. doi:10.1080/19415257.2013.834839.

- Long, E. 2003. Book Clubs. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lyons, B., and C. Ray. 2014. “The Continuous Quality Improvement Book Club: Developing a Book Club to Promote Praxis.” Journal of Adult Education 43 (1): 19–21.

- Mandalaki, E. 2021. “Author-ize me to Write: Going Back to Writing with our Fingers.” Gender, Work & Organization 28: 1008–1022. doi:10.1111/gwao.12584.

- Mandalaki, E., and M. Pérezts. 2022. “It Takes two to Tango: Theorizing Inter-Corporeality Through Nakedness and Eros in Researching and Writing Organizations.” Organization 29 (4): 596–618. doi:10.1177/1350508420956321.

- McCall, A. L. 2010. “Teaching Powerful Social Studies Ideas Through Literature Circles.” The Social Studies 101: 152–159. doi:10.1080/00377990903284104.

- Meriläinen, S., T. Salmela, and A. Valtonen. 2022. “Vulnerable Relational Knowing That Matters.” Gender, Work & Organization 29 (1): 79–91. doi:10.1111/gwao.12730.

- Merton, R. K. 1965. On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript. New York: The Free Press.

- Nolan, M. 2020. “Reading Massacre: Book Club Responses to Landscape of Farewell.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 62 (1): 73–96. doi:10.7560/TSLL62104.

- Parrott, H. M., and E. Cherry. 2011. “Using Structured Reading Groups to Facilitate Deep Learning.” Teaching Sociology 39 (4): 354–370. doi:10.1177/0092055X11418687.

- Peplow, D. 2011. “‘Oh, I’ve Known a Lot of Irish People’: Reading Groups and the Negotiation of Literary Interpretation.” Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics 20 (4): 295–315. doi:10.1177/0963947011401964.

- Porath, S. L. 2018. “A Powerful Influence: An Online Book Club for Educators.” Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 34 (2): 115–128. doi:10.1080/21532974.2017.1416711.

- Poyas, Y., and I. Elkad-Lehman. 2022. “Facing the Other: Language and Identity in Multicultural Literature Reading Groups.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 21 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1080/15348458.2020.1777868.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. 2012. “‘Nothing Comes Without Its World’: Thinking with Care.” The Sociological Review 60 (2): 197–216. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02070.x.

- Pullen, A. 2018. “Writing as Labiaplasty.” Organization 25 (1): 123–130. doi:10.1177/1350508417735537.

- Railton, D., and P. Watson. 2005. “Teaching Autonomy.” Active Learning in Higher Education 6 (3): 182–193. doi:10.1177/1469787405057665.

- Rehberg, S. D. 2011. From Salons to Cyberspace. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sedo, D. R. 2003. “Readers in Reading Groups.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies 9 (1): 66–90. doi:10.1177/135485650300900105.

- Shipman, J., and L. McGrath. 2016. “Transportations of Space, Time and Self: The Role of Reading Groups in Managing Mental Distress in the Community.” Journal of Mental Health 25 (5): 416–421. doi:10.3109/09638237.2015.1124403.

- Stewart, K. 2014. “Tactile Compositions.” In In Objects and Materials: A Routledge Companion, edited by P. Harvey, E. Casella, G. Evans, H. Knox, C. McLean, E. Silva, N. Thoburh, and K. Woodward, 119–127. London: Routledge.

- Street, B. V. 1984. Literacy in Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Swann, J., and D. Allington. 2009. “Reading Groups and the Language of Literary Texts: A Case Study in Social Reading.” Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics 18 (3): 247–264. doi:10.1177/0963947009105852.

- van Amsterdam, N. 2015. “Othering the ‘Leaky Body’. An Autoethnographic Story About Expressing Breast Milk in the Workplace.” Culture and Organization 21 (3): 269–287. doi:10.1080/14759551.2014.887081.

- Van Amsterdam, N., D. van Eck, K. Meldgaard Kjær, M. Leclair, A. Theunissen, M. Tremblay, A. Thomson, et al. 2023. “Feeling clumsy and curious. A collective reflection on experimenting with poetry as an unconventional method.” Gender, Work & Organization, 1–20. DOI: 10.1111/gwao.12964.