ABSTRACT

Drawing from a study of women on boards in Egypt, in this methodological article we propose and illustrate four parts of a multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process for Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) as a method of uncovering hidden stories of marginalised voices and unrecognised contexts. Underpinned by Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology, our novel four-stage approach includes visual images as an alternative mode of data (re)presentation within the hermeneutic circle of interpretation. We show how IPA enables (re)imagining new possibilities of doing and writing feminist research and promotes an in-depth knowledge of the lived experience of women, as well as the systemic issues that concern them. Our contribution highlights our IPA process and outcomes, as a form of feminist praxis that prioritises the recognition of marginalisation and Otherness, embraces an ethic of care towards research participants and researchers, and provides a transformative, emancipatory opportunity for reciprocal learning, awareness and knowing of experience.

Introduction

Within the Middle East context, women’s voices have been marginalised, positioned as Other, and their experiences continue to be unrecognised in mainstream Western academic literature (Abdullah, Ismail, and Nachum Citation2016; Zattoni, Douglas, and Judge Citation2013). This article draws from a study focussing on the experiences of women on boards in Egypt. While we offer some insights into women’s contextual positioning, the main aim of this article is to outline a methodological approach that enables subverting the exclusion and marginalisation of Othered voices to recognise women’s lives, intersubjectivities and experiences as locally situated and interpreted within their own contexts. To achieve this, we propose, illustrate and discuss a multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process for Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA).

With its origins in Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology, and drawing from phenomenology and hermeneutic theory, IPA is an approach to interpreting qualitative data based on human experience. As a methodological approach, IPA is widely used in psychology research, where it focuses phenomenologically on exploring individuals’ lived experiences while interpreting these experiences hermeneutically in relation to their context (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009). However, IPA remains in its infancy within Management and Organisation Studies (MOS) and is yet to be widely adopted for the interpretation of more sociologically based studies (Gill Citation2014). Given the emphasis of the underlying study on women’s marginalisation and embodied experiences, we take a feminist approach to IPA. In this paper, therefore, we illustrate the application of a feminist approach to IPA to argue for its powerful potential in researching the marginalised within MOS.

Although some previous research within health and psychology adopts a feminist approach to IPA (Clifford, Craig, and Mccourt Citation2019; Cohen et al. Citation2022), feminist IPA has been little used in MOS research (Hamdan et al. Citation2022). As feminist scholars and inspired by feminist phenomenologists such as Sarah Ahmed and Simone de Beauvoir (see Ahmed Citation2006; de Beauvoir Citation2009), our ideological and political positions guide us to seek embodied knowledge about the positions of Others, particularly those who have been under-researched, marginalised or ignored. Aligning with feminist critiques of phenomenology that beings are embodied and gendered (Berggren and Gottzén Citation2023), this feminist inspiration allows us to overcome one of the challenges of Heideggerian hermeneutic phenomenology which tends to regard ways of being and knowing as disembodied and gender neutral. Hence, our feminist approach to IPA seeks to address and transform the social and political constructs that oppress or constrain women, enabling us to embed feminist research processes and ways of working into our collaboration with participants and with each other as researchers; by this, as we go on to illustrate in this article, we mean the use of reflexivity, challenging hierarchal power relations and prioritising an ethic of care for participants and researchers.

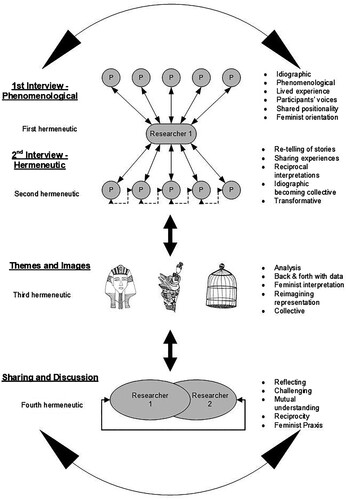

Drawing from interview data with Egyptian women involved in board roles, we illustrate the application of our innovative multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process for IPA. Our approach goes beyond traditional methods of IPA, which tend to focus on a ‘double hermeneutic’ of interpretation whereby the researcher interprets the interview data in which the participants interpret their own experience (Montague et al. Citation2020; Smith and Osborn Citation2003). Instead, our multidimensional process has four parts of feminist hermeneutic interpretation within the whole of the hermeneutic circle; that is, the back and forth of interpretation between the various parts of the text and the whole text, in a constant and ongoing process (Grondin Citation2015). These four parts involve a first phenomenological interview; a second hermeneutic interview; a reimagined (re)presentation of the data through visual images; and finally, reflection, sharing and discussion between researchers. The use of visual images to reflect thematic metaphors and an alternative mode of data (re)presentation as part of the interpretive process is particularly novel in IPA.

The contribution of the article is two-fold: First, we contribute to phenomenological research (Avakian Citation2020; Belova Citation2006; Letiche Citation2009) and the possibilities for IPA in MOS by outlining the process and reflecting on our innovative multidimensional feminist hermeneutic approach to IPA. This gives insights into how IPA can be applied in a MOS context. Second, contributing to a feminist approach to researching and writing (Klostermann Citation2020), we propose IPA as a form of feminist praxis by illustrating the feminist outcomes of our approach, which results in a non-exploitative approach to research, embedded in an ethic of care towards participants and researchers, generating rich data and reciprocal empowering outcomes. Together, we argue that the process and outcomes of our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic approach to IPA produce a depth of visibility and understanding of the marginalised voices.

Our article is structured as follows: first, we briefly outline the position of women on boards in the Middle East and the Egyptian context to recognise their contexts and marginalisation. Second, we discuss Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology and IPA as a method, including its benefits and shortcomings. In the spirit of feminist hermeneutic reflexivity, we then situate ourselves as the authors of this text, before arguing for a feminist approach to IPA. We then reflect on our approach to IPA and how we used it to uncover marginalised experiences. In doing so, we exemplify the four parts of our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic approach and the feminist outcomes of this approach. Our discussion and concluding remarks highlight our contributions and how our innovative approach to IPA contributes a transformational form of feminist praxis and richness to the analysis while amplifying marginalised voices through situated and embodied knowledge.

Contextualising women on boards in the Middle East

Although women are globally underrepresented on boards (Gabaldon et al. Citation2016), they are almost absent on boards in the Middle East and little is known about their experiences (Abdellatif Citation2022). To put this in context, compared to 20% women representation in the West, women are almost absent on boards in the Middle East at 2% (International Finance Corporation Citation2019). Not only are they underrepresented on boards in their contexts, their voices remain marginalised within dominantly Western mainstream organisation research (Jamjoom and Mills Citation2023), even when the extant literature repeatedly called for further exploration of such contexts (Abdullah, Ismail, and Nachum Citation2016; Sidani and Thornberry Citation2010; Zattoni, Douglas, and Judge Citation2013). This is particularly problematic as it fails to consider that women’s access to boards is shaped by situated cultural attitudes toward gender and interwoven contextual factors, social institutions and cultural milieu in this geographical space (Mahadeo, Soobaroyen, and Hanuman Citation2012). Therefore, in problematising the conceptualisation of women as a homogenous or a unified subjectivity (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, and Jackson Citation2008), our feminist approach to knowledge, illuminating marginalised voices of Middle Eastern women not only captures an alternative or more equal way of creating reality (Saukko Citation2003), but also emancipates, empowers, and liberates Othered stories.

Yet, it is key to acknowledge that while the Middle East region shares similar culture and language, it is historically, socially, economically, and politically diverse with different dialects and customs, thus, cannot be rendered monolithic. Specifically, there are variations from one country to another regarding the constraints on women’s lives and work. For instance, due to feminist movements together with a relatively open environment, women in countries such as Egypt and Lebanon encounter fewer restrictions on work (Tadros Citation2018) compared to countries like Saudi Arabia (Aldossari and Murphy Citation2023). In the context of access to boards, a research study finds women’s representation on boards in Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco to be 8.2%, 7.9%, and 5.9% respectively (Abdelzaher and Abdelzaher Citation2019). With a specific focus on Egypt, Egypt targets reaching 30% women representation by 2030, which has guided institutional reforms including amending Egypt’s Code of Corporate Governance to reflect the importance of gender diversity on boards (Egyptian Institute of Directors Citation2016). Notwithstanding recent reforms, Egypt ranked 129th in the global gender gap report with a concern of a constant decrease in women’s access to senior positions (World Economic Forum Citation2022) including board roles. After offering some contextualisation to the phenomenon, we now turn to the broad philosophical and methodological underpinning of our study on women on boards in Egypt – hermeneutic phenomenology and IPA.

Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology

Hermeneutic phenomenology stems from Heidegger’s writings (1889–1976). While phenomenology uncovers meaning as lived in everyday existence (Van Manen Citation2017) to capture ‘the very nature of the things’ (Van Manen Citation1990, 177), meaning within hermeneutics not only originates from an awareness of contexts but also from the dialectical relationships between languages, texts, and contexts (Vannini Citation2008). Thus, when phenomenology describes the lived experience, hermeneutics explains it through interpretation (Finlay Citation2009). This requires one to go beyond what is said, to uncover hidden or taken for granted meaning (Freeman Citation2008). Hermeneutics, as an interpretative process, is therefore used extensively in theology to interpret theological meaning, but our approach here is in relation to social science, generating a situated phenomenological understanding of human beings, in our case women on boards in Egypt.

For Heidegger, phenomenology incorporates ideas from hermeneutic theory (Langdridge Citation2008), entailing that phenomenological meaning lies in interpretation (Heidegger Citation1926/Citation1962). Since meanings can be ‘visible’ or ‘hidden’, it is only through our interpretations that meaning may ‘appear’ (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009). Emphasising our embeddedness in the world, Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology argues for an individual’s situatedness in language, culture, and social relationships (Finlay Citation2009). Interpretation then becomes a foundational mode of existing, ‘being’; to live is to interpret (Eatough and Smith Citation2017). Thus, we are ourselves hermeneutic, interpreters, and understanders. It is this ontological foundation that shapes understanding of the nature of reality (Annells Citation1996; Laverty Citation2003; Van Manen Citation2014), where contextual interpretation and meaning are sought and valued (Tufford and Newman Citation2012).

Consequently, in applying Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology to research, it underpins what is termed the ‘double hermeneutic’ of the interpretive process, where the participant interprets their own experiences during the research interaction and the researcher then forms their own interpretation through the process of analysis (Montague et al. Citation2020). The hermeneutic circle in research represents the ongoing non-linear back and forth of interpretation between the various parts of the data and the interpretive whole (Grondin Citation2015). Inevitably, the researcher brings their own subjectivity and preconceptions to the interpretive process. Other phenomenologists, such as Husserl, advocate what is termed ‘bracketing out’, meaning setting aside one’s own beliefs and assumptions and avoiding interpretation through one’s own biases and pre-assumptions (Kafle Citation2013). However, Heidegger explicitly rejected the possibility of this, acknowledging that people bring their own experiences and understandings to the interpretive hermeneutic process (Larkin, Watts, and Clifton Citation2006), which has the potential of highlighting our active engagement with the data as humans, researchers and analysts.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA)

We now turn to IPA, a qualitative research approach, which is embedded in Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology. Essentially, IPA is the practical application of a hermeneutic phenomenological analytical process in research. From a phenomenological perspective, IPA reveals phenomena by focusing on participants’ lived experiences and exploring their relatedness to, or involvement in, the phenomenon in question (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009). From a hermeneutic stance, IPA is an interpretive endeavour (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009) that focuses on understanding participants and their world as socially/historically contingent and contextually bound, emphasising the inextricable interweaving of person and world (Eatough and Smith Citation2017).

IPA originated in the discipline of psychology (see Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009), being applied particularly to health psychology, counselling and therapeutic work, and is now prolific in this field. Its emphasis on the idiographic and individual experience makes it suitable for the interpretation of psychological phenomena. Gill’s (Citation2014) review of the possibilities of phenomenology for organisational research suggests that proponents of IPA have encouraged its expansion into cognate disciplines, given that it can examine the experiential. The use of IPA has broadened into other disciplines, such as education (Thurston Citation2014), humanities (Hefferon and Ollis Citation2006), and health (Cassidy et al. Citation2011). The use of IPA in management and organisation studies (MOS) is relatively recent but is beginning to build in volume. For example, it has been used to give accounts of organisational change (Sanchez De Miguel et al. Citation2015); to address women’s career barriers (Murtagh, Lopes, and Lyons Citation2007); to explore critical moments of management lived experience (Jedličková et al. Citation2022); to capture the experiences and psychological strain of middle managers (Sengupta, Mittal, and Sanchita Citation2022); and to explore managerial ethical decision-making (Jayawardena-Willis, Pio, and Mcghee Citation2021). We contend that IPA holds great potential in the study of management, culture and organisation in terms of highlighting phenomena and promoting the interpretation of experience. Indeed, it was deemed highly suitable for our study of the experience of women on boards in Egypt, as an analytical process to allow phenomenological hermeneutic interpretation.

IPA has three key features: experience; idiography; and interpretation through the hermeneutic circle (Eatough and Smith Citation2017), which we address in turn. Firstly, experience in IPA is uniquely embodied, situated, and perspectival. Experience is subjective because ‘what we experience is phenomenal rather than a direct reality’ (Eatough and Smith Citation2017, 8). Thus, participants are treated as the experiential experts of the phenomenon under investigation and, because experience is complex, IPA attempts to gain a rich understanding of the individual through attending to all aspects of this lived experience. This involves individuals’ desires, motivations, and belief systems, and how they manifest themselves (or not) in behaviour and action. Attending to these aspects of experience is critical for rich understanding (Eatough and Smith Citation2017).

The second feature of IPA is idiography, which depicts IPA’s focus on the particular. It centres around the particular person, their views, perceptions, experiences and understandings in relation to a specific phenomenon in a particular context (Larkin, Watts, and Clifton Citation2006). Thus, IPA starts with an in-depth examination of a single individual case (subjective experience) before moving to look for patterns of convergence and divergence across cases (Eatough and Smith Citation2017). In so doing, IPA is committed to valuing individuality through focusing on the particularity and uniqueness of individual experiences. Such an approach illuminate participants’ voices and centres their stories (Larkin, Watts, and Clifton Citation2006).

Finally, within IPA, interpretation takes place through the hermeneutic circle, as the most resonant idea of hermeneutic theory (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009), conveying the dynamism of interpretation and understanding (Annells Citation1996) as it becomes knowing. Interpretation in that sense is a non-linear, iterative process that requires moving back and forth between parts and wholes of texts, to make sense, interpret, facilitate understanding and uncover hidden meanings (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009). Interpretation through the hermeneutic circle also involves analysing ‘the contexts in which the whole and parts are embedded’ (Eatough and Smith Citation2017, 12). Drawing from Heideggerian philosophy, IPA involves a two-stage interpretation, a double hermeneutic. Researchers engage with the data trying to make sense (during the analysis stage) of the participants’ trying to make sense (in an interview setting) of their own experiences, hence a double hermeneutic (Smith and Osborn Citation2003).

Despite these rigorous features and the potential of adopting IPA in MOS, we find two problematisations that this article, and its underlying research, aims to address. The first is the lack of transparency or scarce detail on the analytical process of IPA and its application across different studies. This makes it difficult to ascertain, or replicate, the hermeneutic dimension embedded in the hermeneutic circle within the research or understand the potential implications of this process on the research outcomes. IPA is a flexible analytical process, such that it has been referred to as a craft rather than a scientific method (Gill Citation2014), but enhancing understanding of its detailed application enables the authenticity of its outcomes. Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (Citation2009) outline a process of analysis whereby they first annotate one individual case, including essential qualities arising in the participant, secondly identify overarching (subordinate) themes, thirdly, bring together more abstract superordinate themes from that first case before repeating the same process to the next case and the whole sample, and then lastly provide an interpretation of how the various parts form an understanding of that phenomena or experience. This goes beyond a simple thematic analysis in the degree of depth of interpretation for each individual lived experience and the dialogue between the researcher and the text within the double hermeneutic circle of interpretation. Similarly, Cope (Citation2011) outlines a 6-stage model of interpretive phenomenological analysis that moves through familiarisation, immersion, categorisation, any pattern recognition, interpretation and finally explanation or abstraction. However, many studies appear only to give a brief mention of the analytical process, which is problematic when translating a method from one discipline to another.

The second problematisation is the degree of critique offered in the interpretative process of the phenomena in question. Although proponents of IPA empathise that the experience of an individual is socially/historically embedded in their context (Eatough and Smith Citation2017), how that individual/world relationship is interpreted will depend on the ontological positioning of the participant and the researcher alike (Van Manen Citation1990). For example, in the case of women on boards in our study, the focus is on the lived experiences of women who are marginalised and under-represented in this context. Their bodily and social experience, specifically their gender and its social construction, is relevant to their perception and experience (Meléndez and Özkazanç-Pan Citation2021) and their hermeneutic interpretation of this experience. While ways of being are essentially embodied and gendered (Berggren and Gottzén Citation2023), Heidegger’s phenomenology has been critiqued by feminist scholars for presupposing a gender-neutral view of ‘being in the world’ or what Heidegger termed Dasein (Huntington Citation2001). Instead of focussing on social relations and the influence of social markers such as gender, Heidegger rather focussed on the philosophy of human ontology or the human condition (Huntington Citation2001). Aligned with feminists’ argument that ontological position cannot be disentangled from one’s social situation and gender, we see that feminist phenomenology can centralise being, embodiment and ontology in the social experience (Holland and Huntington Citation2001; Oksala Citation2004). Therefore, by taking a feminist approach to IPA, we can both empathise the embodied experiences of our participants and place women’s experiences in an interpretation and critique of social context. In this sense, we suggest that Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology can align with feminist ideals, where the quest of seeking understanding cannot be conducted from a detached, objective, disembodied or disengaged standpoint (Kafle Citation2013). More specifically, ‘what something means depends on the cultural context in which it was originally created as well as the cultural context within which it is subsequently interpreted’ (Patton Citation2002, 113), which helps us as feminist researchers to bring back to the centre marginalised contexts and invisible voices. Before illustrating how we applied this feminist approach to IPA in our study, we see it important to reflect on our own positionalities and how our own social positions influence our feminist methodological approach.

Our positionalities and situatedness

The critique of representation problematizes the relationship between world and knowledge, seen and see-er, object and subject. (Letiche Citation2009, 2)

First author

In conducting this research as an Egyptian woman and a feminist researcher, I acknowledge sharing similar identities culture, and language as well as professional experiences with the research participants. Before shifting to academia, I worked as a Managing Director in Egypt and faced multiple barriers to leadership positions. This background informed the choice and focus of this research to prioritise illuminating women’s experiences and the contextually interwoven gendered, cultural and structural impediments that they experience, which are significantly marginalised in mainstream Western research. In conducting this research, being an ‘insider’ helped approach the study with a cultural, contextual, and language awareness and familiarity, which facilitated relational sense-making; that is, such positionality shaped the nature of the relationship with the research participants and influenced the information that the participants were willing to share (Berger Citation2015), enhancing the collaborative nature of knowledge (co)production. However, this shared familiarity with the researched and context was also challenging in uncovering hidden or taken for granted meaning. For example, as an Egyptian woman myself, the participants assumed that I already ‘know’ what they mean by what they say, and understand their embodied reflections without needing any further elaboration.

Second author

I am a white, middle-aged English woman from a working-class background. Some elements of my experience, related to class and gender, have caused me to feel like an outsider at times. Being the first and only member of my family generation to go to university, I was aware of feeling very different from the privately educated, affluent students who predominated, and again I was marginalised when I worked in the accounting profession, being female in a highly male-dominated context, where there were few senior women and where my gendered and classed body was not the norm. Feminism, for me, centres on addressing structural, social and cultural marginalisation and inequalities, using research methods that invoke connectedness and trust. My experiences help me to empathise with others who are marginalised. However, I am also aware of the privilege that education and Western whiteness brings, meaning that I cannot ‘know’ fully the experiences of women such as our research participants. I am also conscious that, as a white, European academic, I need to be reflexively aware of how academia itself privileges the production of knowledge from the Global North and strive not to be complicit in this process. Working on this research with the first author enabled mutual learning, critical questioning and challenging each other’s assumptions that supported our intersubjective feminist reflexivity (see Haynes Citation2023) and collaborative knowledge production.

Our feminist positioning and methodological approach to IPA

We use IPA here as a form of feminist praxis that seeks to uncover and recover marginalised Others and as means of dismantling the dominant Western, patriarchal and androcentric sources of knowledge (Burgess-Proctor Citation2015). To us, being a feminist researcher means that we see our research and writing as a political endeavour and a feminist project (Boncori Citation2022). This takes a number of forms. First, we aspire to co-create knowledge about the position of women, particularly those who have been Othered, under-researched and marginalised. This study of women on boards in Egypt reflects gendered dynamics and experiences situated in a particular context that remains largely ignored within mainstream organisation research. Second, as Klostermann (Citation2020) argues, feminist research can both surface women’s experiences and struggles and politicise and explicate their social construction. Thus, in illuminating the social and political constructs that oppress or constrain women, we enable their transformation by making them visible. Third, we seek to research in such a way that nurtures feminist principles of care, ethics and reciprocity in our methods and ways of working, with an awareness of the relationship between the process and the product of research (Haynes Citation2008).

We therefore embedded these feminist political endeavours into our reading of the IPA process. To promote knowledge of the marginalised, an underlying intent of the study was to uncover stories of marginalised voices within an unrecognised context, using a method that enables the recognition and interpretation of those invisible stories. As can be seen from our position statements, we tried to avoid enforcing acontextual normative Western narratives of Egyptian women, but rather to place our participants’ voice at the centre of the study. Hearing and analysing stories in their context allow for recognition of difference between women, to subvert rendering them as a coherent unitary category (Mohanty Citation2003). With its focus on localised knowledge, our feminist approach to IPA enabled us to problematise research in MOS that normatively embodies White, Western women’s experiences, where women who do not fit this ‘image’ are presented as the Other (Calás and Smircich Citation2006). Thus, departing from an emphasis on researching the privileged, our feminist positioning and research orientation brings marginalised stories back to the centre (Harding Citation1991) to access invisible under-represented voices (Hesse-Biber Citation2014).

Our feminist political intent in our approach to IPA seeks not only to construct new knowledge of women’s experiences but also to promote social change and challenge the multiple interlocking oppressions that women may face (Clifford, Craig, and Mccourt Citation2019). Although women’s experiences are diverse and distinct, their experiences in public and private institutions may expose common sources of power, dominance or oppression. Hence, while illuminating individual experiences and sensemaking, our hermeneutic interpretive approach highlights the gendered power imbalances and wider structural factors that may underlie them. Rejecting society as gender neutral, our feminist politics seeks to expose oppressive systems to enable their transformation. Doing so allows us to move away from an entirely individualised knowledge of experience to a conceptualisation of affective solidarity with others (Vachhani and Pullen Citation2019) and helps to support incorporating culturally sensitive and social justice perspectives into traditional knowledge production, especially when exploring personal experiences and the systemic issues which influence them (Cohen et al. Citation2022).

Our practice of the IPA method incorporates some key tenets of the feminist method. First, we sought to avoid hierarchical power relations within the research process, where participants are seen as experts and engaged actively and collaboratively in the process of knowledge (co)production. When interviews were conducted by the first author, she sought to build trust with the participants through sharing mutual vulnerabilities, where attention was paid to expressions of emotion and subjective experience from participants and researchers alike. This aligns with feminist scholars who ‘often position themselves as reflexive actors within structures and practices of inequality and oppression, rather than as neutral observers’ (Bell et al. Citation2020, 184). Thus, while it contests knowledge production as independent of the researchers producing it, reflexivity can become a central tenet of feminist identity beyond research (Haynes Citation2023). Additionally, we embraced the feminist concept of ‘ethic of care’ in our research, which commits to practice that respects relationality and positionality, and centres notions of care, between the self and the other (whether participants or researchers) (Preissle Citation2007; Sai et al. Citation2024); that is, conducting research that cares for/about/with self and others to enable surfacing marginalisation in the pursuit of promoting justice (Brannelly and Barnes Citation2022). Furthermore, in conducting and presenting our research, we also adopted an innovative approach to the IPA method to reflect our feminist stance, such as collaborative working and the use of visual images for thematic representation. Such an approach resonates with feminist scholars within MOS aiming to embed feminism and carry out research and writing ‘differently’, to respect difference, to embrace own and others’ vulnerabilities, to resist the ‘linear’, masculine, patriarchal knowledge, and to reflect on the ethical and political dimensions of knowledge production (see, for example, Bell et al. Citation2020; Boncori Citation2022; Kociatkiewicz and Kostera Citation2023; Kostera Citation2023).

In summary, our feminist approach to IPA advances openness, reflexivity and sensitivity to power relations in the hermeneutic circle between participants and researchers, which supports an ethic of care in the research relationship. In so doing, it enables uncovering marginalised contexts and centring Othered voices to be heard and to be seen, while bringing forth new meanings and understandings, and promoting an alternative, more equal and inclusive way of revealing lived realities.

Conducting IPA: a multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process

After discussing IPA’s key philosophical tenets, situating ourselves as the authors of this text, and arguing for the transformative potential of a feminist approach to IPA, in this section we address how we applied IPA in our study. In doing so, we do not present the process as a rigid template for others to follow; rather, we illustrate the methodological choices underpinned by our feminist positioning and exemplify some of the outcomes of the method. Thus, our presentation of the process offers possibilities for feminist IPA that others could seek inspiration from.

We illustrate four parts of our research process, which we have termed a ‘multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process’ for IPA. While conducting this study mirrors the non-linear dynamic process of interpretation, as typically seen in IPA’s double hermeneutic (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009), our approach went further to incorporate multidimensional layers of interpretation as part of the whole hermeneutic circle. According to Heidegger, the hermeneutic circle is a constant and ongoing process where interpretation is borne out of presupposition and anticipation but also is ‘borne out by the things themselves’ (Grondin Citation2015, 299); that is, it allows for a process of interpretation that recognises contextual situatedness and preunderstandings, of both researcher and participants, while producing knowledge that relies on all the multidimensional parts of the whole in the research process.

In the following section, we identify four key parts to the multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process forming the whole of the hermeneutic circle in our study (depicted in ) by exemplifying the process of interpretation within these parts, before discussing the outcomes of this process. These four parts are: a first phenomenological interview; a second hermeneutic interview; a reimagined (re)presentation of the data using images; and finally, reflection, sharing and discussion between researchers.

The phenomenological interviews

All of the interviews for the study were carried out by the first author with 12 Egyptian women, who were senior executives and/or board members (executive and non-executives) within the Egyptian banking sector. Each participant was interviewed twice, resulting in a total of 24 in-depth semi-structured interviews, each interview lasting between 60 and 90 min. As a phenomenological study, paying attention to the process of interviews was key.

Some qualitative studies may end data collection after a single interview, relying on the researcher’s interpretation of the participant’s interpretation of themselves in that interview. However, in phenomenological studies accessing the lived experience is crucial (Eatough and Smith Citation2017; Van Manen Citation2014), and in hermeneutic phenomenology, which underpins IPA, the hermeneutic process requires a means of establishing and understanding a deeper meaning of individuals in their socio-cultural context. Therefore, to embed the hermeneutic process more firmly in their method, some IPA scholars undertake a two-stage interview process (Doyle Citation2007; Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009).

Our study followed this two-stage interview process, or what Van Manen (Citation1990) refers to as a first phenomenological interview, followed by a hermeneutic second interview. The goal of the first interview was to establish trust and a rapport with the participants to make them feel comfortable with sharing their lived experiences to then be followed with a reconstruction of their experience (Seidman Citation2006) in a second interview. This second interview was not only used as a ‘member reflection’ to enhance the research credibility and trustworthiness (Tracy, Citation2010) but also to overcome the challenge of the first author’s ‘insider’ position and the perceived familiarity and assumed understanding with the researched; that is, given the shared positionality with the participants, the second interview was essential in uncovering taken for granted meaning and assumptions about the phenomenon in question through probing participants’ storytelling in the first interview. In other words, the second interview helped in sustaining an active engagement between the researcher and the participant as they collaboratively seek to gain a deeper understanding not only of what was said but, importantly, of what was omitted or unsaid.

As depicted in as ‘1st interview – phenomenological’, the first interview was phenomenological, where the focus was on exploring participants’ experiences, narratives, and stories. It enabled an idiographic account of individual lived experience to gain a phenomenological understanding of what it was to be that individual woman in that context. It aimed at establishing a foundational trust with participants and gathering experiential material (Van Manen Citation2014). Aligned with feminist methodology, Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology recognises our situatedness as researchers in the interpretative process. Therefore, in this interview, the first author was transparent about her positionality as a woman with similar contextual and professional background. This shared positionality of the first author as an Egyptian woman of colour was beneficial in lessening gendered and colonial ideologies that invoke power and emotion in the research relationship (Faria and Mollett Citation2016) allowing for more open interaction, and enabled having insights into the shared gendered, racial, and cultural challenges faced by the women in a more nuanced way, compared to a White Western researcher (Haynes Citation2023). As feminists assert, the notion of ‘woman’ is not a universal category and research needs to allow for a consideration of race, class, religion, culture and socio-political context, going beyond Western ethnocentrism (see, for example, Gallhofer Citation1998; Haynes Citation2023; Prasad, Segarra, and Villanueva Citation2020). However, notwithstanding their shared similarities, the first author approached the topic with a feminist awareness and reflexivity (Daley Citation2010) and was explicit that she cannot suggest she is the same as any of the participants, given that our lived experiences are uniquely shaped by other intersectional differences such as class.

In this part of the research process within the whole of the hermeneutic circle, being open about the positional (dis)similarities with the participants enabled nurturing mutual trust and embracing vulnerability to centre women’s voices, being, and lived experiences. Since a feminist ethic of care, through caring for/with Others, drives the marginalised to make sense of their Otherness (Johansson and Wickström Citation2023), not only creating such an enabling space for vulnerability and trust to be mutually shared helped the participants to make sense of their own lives during the interview, but also the researcher to recognise their marginalisation and Otherness in this context.

The hermeneutic interviews

The second hermeneutic part of the multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process of IPA, centres on the explicit double hermeneutic of the second interview. The double hermeneutic of IPA involves a two-stage interpretation in which the researcher brings their own experiences and sensemaking to the experiences of the participants; that is, as the participants try to make sense of their own experiences, the researcher interprets the participants’ sensemaking in the double hermeneutic process (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009). In this case, the participants were invited to take part in second hermeneutic interviews to allow a space for further reflections, insights, emotions and feelings that emerged in the first phenomenological interview, within their own sensemaking double hermeneutic process.

The second interview built on the foundational trust established in the first interview. Motivated by an ethical commitment towards participants (Manning Citation2018), the second interview was designed with a desire to respect participants’ knowledge and experience, with an awareness of difference, sensitivity to Otherness, and aliveness (Letiche Citation2009). The focus was on bringing forth the participants’ voices and experiences, in a way that prioritises care, compassion, relatedness, and connectivity between researchers and participants (Harding and Norberg Citation2005). Since some of the stories shared triggered emotions such as sadness and anger and informed by a feminist understanding of emotions as an epistemic resource (Lutz Citation2002), it was key to prioritise these emotions and allow time during the interview to connect and relate together through these emotions with care and compassion.

Depicted in , as ‘2nd interview – hermeneutic’, the second interview, with its hermeneutical turn, served two main purposes. First, from a feminist approach to knowledge production, the first author shared her interpretations of participants’ stories in the second interview, inviting them to confirm, amend, or add any additional meaning or insights, which prompted further disclosures by, and new understandings, for both parties, in a caring relational collaborative process. This did not only shift research power relations (Preissle Citation2007) from researcher-participant to knowledge co-creators (Van Manen Citation1990) but also enabled deeper understanding, where the second hermeneutical circle unfolded allowing participants to reconstruct their narratives (Birt et al. Citation2016; Doyle Citation2007). For instance, when participants heard their journeys to board being told as stories by others (first author) during the second interview, they reconstructed their initial understanding of giving up as emerged in the first interview and instead recognised it as resilience and persistence.

With a focus on relationality and relationship building with participants, the second purpose of the hermeneutic interview was to allow a space for empowerment and emancipation. As Koelsch (Citation2013) argues, if research empowers participants to action, then participants can engage and change the status quo, where a political intent for the transformation of oppressive systems and structures is a tenet of feminist research, as we explained earlier. Therefore, prior to the second interview, the first author had two informal interviews with key women leaders in an entity that monitors and promotes more women on boards in Egypt and the MENA region. This meeting resulted in an agreement of mediating between the entity and the participants of this study. As a form of ‘giving back’, and to embed a feminist ethic of care and reciprocity in the research process, this mediation was in place to help women explore different paths to boardrooms, by sharing key information about the entity’s services and contacts, training and educational support guide, and details on a database for women on boards, or those who aspire to be. Through this intervention, the participants also had the opportunity to hear the stories of other women in similar situations, including some sharing of individual stories of both success and struggles from women who had explicitly consented to some of their experiences being revealed to others in the research process. It is through this process of sharing, reciprocity and relationality that struggles within lived experiences were not confined to that of individual knowledge, which participants found to be empowering, emancipating and comforting.

This second hermeneutic interview, therefore, was used to move beyond research as ‘transactional’ to research as ‘transformational’ (Cho and Trent Citation2006), one that catalyses change and embeds an ethic of care toward its participants (Preissle Citation2007), and where our feminist approach centres around supporting and respecting participants’ lives (Burgess-Proctor Citation2015). The outcome of this feminist approach and its emancipating and empowering potentials were evident in the types of responses given by the participants who indicated the influence of the second interview on their sense of self, in which they felt heard, recognised and valued. Their reflections mirrored not only their reconstruction of meaning but also the cathartic and healing potential of feminist-informed IPA interviews, where silence and Otherness are subverted through mutual care and respect, to reclaim one’s voice as valid:

I felt like I was visiting a psychiatrist, do you know this feeling? I have this feeling that I can speak out loud to someone … so you want to speak openly about some challenges that you are not vocal about, that was really very relieving. And then you start to look and realise, I am good, I’m not that bad, I’m doing well, I have achievements. I can talk and I can speak, So I started to question myself why do I have some self-esteem … I was starting to lose myself. (Meera, 40, senior executive)

Looking back at their stories, some participants realised that their success was undermined by marginalisation and silencing, thus, by allowing a space for their stories to be heard, they reconstructed the narrative and started to reclaim their voice.

When you talk and put things in a chronological order, you get a different picture of what you do, you know what I mean? So, when I talked with you, I felt like I’m not that bad as I think, and I am OK, and I’m fine and I have made lots of progress. Do you know why? Because I started to tell it to someone … (Reem, 35, senior executive)

It was more than excellent and really very interesting, and it is really informative and beneficial because you made me start to see how the academic dimension looks at the practical dimension, so it is really fascinating … I feel like I’m heard, like the world can actually see me now … I’m really happy, I’m listening to you while I am actually smiling and happy. (Ruby, 43, senior executive)

However, within this feminist collaboration, care was reciprocal. In particular, as a space which was originally created to empower the participants, the second interview became the same space where the researcher herself felt empowered. The first author found that the participants often gave advice in relation to her position as an Egyptian woman, researcher, and single parent living in the UK. They showed reciprocal care, encouraging her to keep going regardless of the inevitable hurdles on the way, which caused her also to find the process transformative and empowering as she reflected on and learned more, both about her own sense of self and the research process:

I know it is never easy to raise your kids alone while working, studying and being away from home … don’t you ever think that when you fall, you will not stand up again … God created us to make changes to our world, so he will never leave us, he will always be with us … if it is difficult now for you, believe that it will always get better. Don’t you ever give up! [Amira, 59, board member].

Analysis: a reimagined (re)presentation of the data using images

The third part of our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process for IPA involved analysing the data from the first and second interviews. This represents the third part of the hermeneutic circle of understanding, depicted in as ‘Themes and Images’. This included a two-stage process of first analysing the data hermeneutically into themes, followed by a further analytical stage of alternatively (re)presenting and developing the themes in the form of images. This latter stage is not a typical means of analysis using IPA and to our knowledge has not been used before, hence it forms an innovative part of our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process for IPA, as we discuss further below.

The analysis of the interviews was a cyclic, non-linear, iterative, and inductive process. As discussed earlier, our analysis followed a case-by-case approach; we started looking at each individual case before analysing data at the collective level. IPA usually draws upon small homogenous situated samples to focus on revealing the experience relevant to the phenomenon and the particularity of each individual case before exploring convergence and divergence of experiences across cases (Eatough and Smith Citation2017). We followed this approach, but our feminist ethic of care informed the analytical process, by paying attention to participants’ tones, pauses, sighs, emotion and embodiment, listening to what is said and unsaid, with an ethical commitment to hear and try to understand their perspectives and experiences in both interviews. For the first case, the experiential, semantic, and language content were explored, followed by producing a set of emergent subordinate themes. Looking for patterns, links, and connections, subordinate themes were developed into more abstract analytical themes, superordinate themes. After finalising the analysis of the first account, each case was analysed individually using the same process to appreciate the unique insights and lived experiences of each participant. Superordinate themes were those identified as relating across the individuals. Yet, although superordinate themes were at the collective level, they were still illustrated with particular examples from the individual case and captured in the participant’s words to preserve the individuality of each woman’s lived experience and amplify their unique voice. Making sense of the data involved engaging in a hermeneutical dialogue with the text to move from the particular to the shared, parts to whole, and from the descriptive to the interpretative (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009). It is this hermeneutic approach that makes IPA different from thematic analysis (see Braun and Clarke Citation2006) as it pays particular attention to the idiographic, to the double hermeneutic of the researcher interpreting the participants’ own interpretation of themselves, and it offers multiple levels of interpretation by both participant and researcher in the hermeneutic circle.

Since the aim of the underlying research project was to centre the experiences and lived realities of marginalised Egyptian women on boards in the banking sector, it was key to consider how to construct, organise, and tell their stories. We could have conveyed the interpretative themes in traditional forms of written academic presentation. However, an alternative means of data representation was chosen to develop and (re)present the themes in the form of images. This represented a second stage in the thematic IPA analysis and is an innovation exclusive to our study. Although IPA has been utilised extensively in psychology, as an approach to adopting the method into other disciplines such as MOS, opportunities for methodological innovation occur. Hence, reflecting on the means of presenting the IPA narrative ‘differently’, resonates with recent debates on researching and writing differently (Boncori Citation2022).

Given our feminist approach to IPA, we wanted to engage with different forms of storytelling (Steyaert and Hjorth Citation2002) and data representation that both uncover marginalised subjectivities and also convey the social and political dimensions of the research in eliciting forms of oppression. In particular, using metaphors and art, we, the researchers and storytellers in organisations, seek to illuminate local meanings to (re)imagine new possibilities (Akin and Schultheiss Citation1990). This is essentially powerful since writing in organisational studies is itself an organising practice that involves telling stories through using metaphors (Caicedo Citation2011). With an understanding that seeing reality with and through art enables us to capture plurality and reimagine possibilities, art, as used here, is considered as an alternative genre of speaking; a space for political, ideological and ethical speech. Thus, in telling stories through this visual language, we go beyond words to explore new ways of knowing, one that holds a potential transformative power in unearthing the experiential dimension in a non-textual form (Ewenstein and Whyte Citation2007). Moreover, as Belova (Citation2006, 93) articulates:

Looking can be conceptualised as a deeply embodied and pre-reflective involvement with the surrounding world and others where all senses intertwine, rather than form a hierarchy, to create a lived-out experience.

Visual metaphors were utilised as meaning vehicles with the primary aim of understanding the individual and collective experience of the women in our study; that is, in presenting superordinate themes, as the idiographic became collective, visual images were used as an alternative mode of data (re)presentation, revealing lived experience in an affective, playful, intimate, dynamic, and relational way. Specifically, inspired by the metaphors evident in the participants’ own words, such as ‘Pharaoh’, ‘whirlpool’, ‘caged’, our visual representations of these themes were utilised as invoking artistic ways of knowing and understanding (Klostermann Citation2020). Thus, they capture, in image form, the phenomenological – the visceral, embodied, emotional nature of the participants’ experiences. These depictions also insert a third level of hermeneutic interpretation; since they were an interpretation and representation of superordinate themes, which were themselves originally informed by the double hermeneutic previously occurring during our interpretation of the participants’ own interpretation of themselves. As part of the hermeneutic circle, they iterate the back and forth of individual and collective, part and whole, which results in an enhanced deeper understanding. Depicted in as ‘Themes and Images’, this part of the hermeneutic circle captures our interpretive analytical process through visual images to convey the women’s stories, embedded in the particular sociocultural context of Egypt and encapsulating metaphors of the Pharoah, the Lever and the Patriarchal Cage.

The Pharoah

The Pharoah as a metaphor captures men’s unadulterated power within both private and public domains. Particularly, the visual dimension of the Pharoah encapsulates the gendered context and culture of Egypt in which men and masculinity dominate, and where women are subjected to masculine power in terms of their ability to partake in business settings, such as boardrooms. The authority and command of the Pharaoh represent the necessary sponsorship and patronage of men when women are Othered as not belonging to that position nor enabled to enact their own voice to challenge the embedded patriarchal patterns. The use of this metaphor is manifested eloquently in Christine’s account, which reveals the intensity of men’s power and control in this context:

You must thrive his ego for you to thrive … if my intention is only to bloat you [masculine] so that you get me promoted or for you [masculine] to feel that you’re humiliating me, for me uh this is the creation of the pharaoh and this is literally against my principles … When I try to think about it, what could I do that is within my control to access the board rather than thinking now for example of what could change in Mohamed for me to be on the board. (Christine, 37, senior executive)

The Lever

The Lever metaphorically represents the blurred boundaries at the intersection of the private-public, personal-professional, or family-work realms, overburdening women and impeding their representation on boards. The Lever therefore reflects the experience of having to balance intersecting forces as a lever does on a fulcrum or fixed point. It was inspired by participants’ metaphorical use of ‘whirlpool’, thus, was depicted artistically by the wind-blown dress, a woman constrained, with arms folded against the struggle as she tries to survive interwoven barriers of neoliberalism at multiple levels. However, within The Lever metaphor, there is still the possibility of agency and resilience as a lever exerts force and reflects possibilities. This metaphor is reflected in Nadine’s quote, in which despite the ‘whirlpool’ of her responsibilities, she still makes time for her own studies:

I am a married woman and I have children … it is a roller coaster, I am someone who comes back from work to finish domestic work so by 12:00am I start studying, then I sleep by 2:00am to wake up 6:00am, prepare the sandwiches for my children, wake them up to go to school then I get dressed, I go to my work and spend the whole day at work and then I come back to take my children to their sports’ trainings, so it is nothing to say but roller coaster. That’s it, my life is a whirlpool! (Nadine,40, board member)

The Patriarchal Cage

Metaphorically, the Patriarchal Cage describes women’s perceptions of entrapment in patriarchy revealing the way in which women are positioned in society. As an ornamental bird cage, it depicts women as an object of beauty or interest, subject to the gaze, monitoring and dependency of men, while it signifies constraint and lack of freedom in society. It is representative of the contextual and structural factors which inhibit women and their emancipation:

The way society looks at women is still not a proper look … The way you stand, the way you talk, the way you express, the way you comment, the way you position yourself, the way you even pose the question. Everything you do is monitored, judged, and observed … you are required to do so many things, to look professional, to be professional, you are required not to be misperceived, to watch what you’re saying, all this, because everything counts. Everything! (Meera,40, senior executive)

Reciprocal sharing and discussion between researchers

In coming together as the authors of this text, the fourth part of our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process for IPA occurred when we both discussed and reflected on the interviews, and particularly the visual images, as a means of understanding the broader experiences of women accessing boardrooms in the socio-political context of Egypt. This part is depicted as ‘Sharing and Discussion’ between the researchers in .

Our process of reflection on the research and critical challenge between us as authors, enhanced our mutual understanding of both the phenomena at stake (women’s experiences on boards in Egypt) and the hermeneutic process for both of us. For example, since, as can be seen from our earlier positionality statements, we are from different cultural backgrounds, each of us as researchers and authors had to address our pre-existing assumptions and knowledge of the Egyptian context. Hence, questions such as ‘what is the culture like? What are the general expectations and norms for women?’ from the second author, as a White British woman who has never visited Egypt. For the first author, as an Egyptian researcher now living in Britain, the questions were around how her own socialisation and experiences of being an Egyptian woman have influenced her research design and perceptions of the participants’ experiences and how her pre-existing understanding has been challenged throughout the analysis process. As Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology acknowledges, pre-existing understanding and experiences will be inherent to the interpretive hermeneutic process, as it is impossible to exclude them from the process of interpretation and understanding. This dialogical dimension and critical questioning between us as researchers formed part of the hermeneutic circle of back-and-forth interpretation between the parts and the whole of the research process. Hence, this fourth stage was integral to the whole hermeneutic circle of interpretation as depicted in .

Yet, this fourth stage of sharing and discussion in our multidimensional process was essentially embedded with feminist research principles. In our critical dialogues, we embraced vulnerabilities and tried to be reflexive about how our subjectivities and positioning influenced our understandings. We aimed to work with reciprocity and collaboration that minimised power relations or hierarchies in the interpretative or writing process, and we both (co)constructed and contributed to the argumentation. We approached the writing with a reciprocal ethic of care that saw both of us support each other through personal and professional challenges during the writing of the article. Our individual and shared vulnerabilities enabled us to develop practices and imaginaries of care (Johansson and Wickström Citation2023), between us, as women, as feminists, and as researchers, and with the research participants. The writing, as well as the overarching research, became a form of feminist praxis, that enabled a greater understanding of the marginalised with a transformational potential to subvert Othering.

Discussion

We now reflect on our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process for IPA as a whole, its potential, outcomes, and challenges as well as our approach’s contributions. The whole hermeneutic circle of our research process is depicted by the large circular arrows, surrounding the various parts (). While the first phenomenological interviews sought an idiographic account of lived experience, suffused with a feminist ethic of care towards participants, the second interviews had distinct hermeneutic aspects through a ‘retelling’ of participants’ stories in the first interview, to elucidate deeper meaning and co-construct nuanced understandings of the participants’ lived experience by both the researcher and the participants themselves. As a form of giving back and reciprocity, within this second interview, information was shared about the support available for women aspiring to or joining boards in Egypt, with an emancipatory and transformative intent that centred on a feminist ethic. As a result, during this second hermeneutic interview, the idiographic lived experience was highlighted but moved towards becoming a collective understanding for the participants and the researcher.

The back and forth between the two interviews of each individual enabled a third hermeneutic process of analysis between meanings and context that led to further new understandings. This resulted in the superordinate themes being (re)produced in alternative forms through means of visual images representing thematic metaphors that captured women’s embodied experiences. Consideration of experiences between each individual fertilised interpretation towards a more collective understanding of the contextual issues that the women faced in being and becoming on boards in the Egyptian context. Our feminist interpretation of these themes is embedded in the metaphors representing the Pharoah, the Lever, and the Patriarchal Cage, which symbolise the barriers, challenges and systemic issues facing women. Such an analytical approach enabled us to surface these more structural and ingrained issues facing the women, their collective experience of the broader Egyptian socio-cultural context as well as their individual lived experiences.

While the use of alternative, metaphorical representations of the women’s experiences in the form of hand-drawn visual images makes visible the collective experiences of Egyptian women’s stories and dismantles their silencing in mainstream organisation research, as a methodological paper, it is beyond the scope of this article to address detailed accounts of their individual experience and context. Rather, our focus in this paper is to show how these representations allow embedding an additional layer of hermeneutic interpretation while capturing an artistic understanding of the experience of the systemic issues facing women. Finally, in the multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process, our reciprocity and collaboration as authors, in reflecting, sharing, and discussing the hermeneutic process and outcomes, formed an additional layer and integral part of the hermeneutic circle of interpretation. Underpinning all of the research process in the hermeneutic circle is the notion of a feminist approach to methodology and ways of researching that centres reflexivity and ethic of care in relations between researchers and participants, and between researchers.

In sharing the details of each stage of the process within the larger hermeneutic circle, in the article (and in ), we have illustrated how and where the hermeneutic analysis occurred, which we hope will be of interest to researchers who may wish to adapt our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic method for IPA for their own studies. To some degree, the hermeneutic circle described above may seem like a fairly linear or straightforward process. However, like much qualitative research, it was messy, non-linear and challenging. For instance, since many IPA studies do not detail the steps taken in the analysis, the analytical process was challenging specifically on how to move from/between parts to the whole of text, experience and context; that is, how the analysis moves from one case to another, from the individual to the collective, while appreciating the particularity of each account, and their context. Additionally, although the first author’s ‘insider’ positionality as an Egyptian woman was enabling, researching the familiar was also challenging. Given the nurtured trust and shared positionality, as both participants and researcher engaged in the hermeneutic circle of understanding with comfort and familiarity, it was sometimes emotionally challenging to unpack some of the participants’ stories as they started to share it.

In summary, the three dimensions of IPA, experience, idiography and interpretation, allow for a hermeneutic interpretative method that centres on the phenomenology of lived experience, as richly situated, embodied and perceptual. Derived from Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology, the focus is on one’s being and its position in the world, hence person and context are inextricable, open to interpretive analysis. IPA achieves this through its idiographic nature which recognises experiences as individually lived and values participants’ unique subjective accounts of living a specific phenomenon within a particular context. In so doing, it deliberately allows for an in-depth individual analysis before moving towards any sense of collective analysis and understanding. For these reasons, we see the potential of hermeneutic phenomenology and IPA, which can afford interpretive insights into being and experience, set in context.

However, as we reflected earlier and according to our positioning on and understanding of feminism, a feminist approach to IPA allows for a more political approach in amplifying Othered voices. In valuing the subjective as a source of knowledge, such an approach focuses on those subjectivities (mostly of women or other oppressed groups) who are marginalised, under-represented or even persecuted for different reasons of difference. Hence, this feminist approach to IPA not only aims to enable those subjectivities to be heard and seen but also to highlight the underlying cultural antecedents and systemic dimensions of women’s experiences and their marginalisation. As a result, and inspired by feminist phenomenologists such as Sarah Ahmed and Simone de Beauvoir, our feminist approach addresses some of the critique offered by feminists to Heideggerian phenomenology (see, Berggren and Gottzén Citation2023; Huntington Citation2001); that is, our approach does not assume any form of gender neutrality in subjective experience, nor does it shy away from interpreting collective experience as mediated through systemic gendered norms, cultures or institutions. In this sense, our feminist approach to IPA contributes knowledge on gendered contexts as well as gendered individual experiences with a feminist intent that knowledge can promote transformation.

Furthermore, our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process goes further than traditional approaches to IPA in its degree of hermeneutic analysis. Within IPA, since researchers share the fundamental property with the participants ‘of being a human being’ (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2009, 3), they can consciously use their humanity to interpret the participants’ experiences through their accounts of them. Our approach to IPA similarly allows for the human capacity of reflecting, thinking and feeling to support our interpretations of participants’ interpretations of their experiences within the double hermeneutic. However, our research took the hermeneutic process further, with four multidimensional parts informing the whole of the hermeneutic circle of interpretation, allowing an interpretive dialogue between researcher and participant, researcher and text, and researcher and researcher.

We argue that our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic method for IPA nonetheless results in a rich and transformative approach to knowledge that overturns excluded and marginalised voices, resulting in feminist praxis that prioritises the recognition of Otherness. Our contribution is, therefore, two-fold: First, we contribute to phenomenological research (Avakian Citation2020; Belova Citation2006; Letiche Citation2009) by illustrating and exemplifying how our innovative multidimensional feminist hermeneutic approach to IPA results in a process that allows opportunities for openness, reciprocity, and transformation, each contributing further depth of understanding, interpretation and knowing to the overarching research. Thus, we offer the possibilities for IPA in MOS by giving insights into how IPA can be applied. Second, we contribute to feminist approaches to researching and writing (Klostermann Citation2020) by illustrating the feminist outcomes of our process, resulting in a non-exploitative approach to research, embedded with an ethic of care for participants and researchers alike, which generates rich data and knowledge on both individuals and contextual issues. These empowering and transformative outcomes are a form of feminist praxis. Together, we argue that the process and outcomes of our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic approach to IPA produce a depth of visibility and understanding, representing a political endeavour, with the potential for uncovering the experiences of the marginalised in organisational and cultural contexts.

Conclusion

This article outlines our novel methodological approach – a multidimensional feminist hermeneutic process for IPA – derived from a study of women on boards in Egypt. We illustrate how IPA can be applied to organisational research, in relational ways that not only enables (re)imagining new possibilities of doing and writing feminist research but also promote an in-depth knowledge of the lived experience of Othered voices, as well as the systemic issues that concern them. Specifically, our intent is to show how this approach enables excluded and marginalised voices to be amplified and understood, resulting in a locally situated knowledge that appreciates women’s lives and contexts, to acknowledge their being and experiences. Yet, we do not claim that our multidimensional feminist hermeneutic method for IPA is the only way of approaching feminist IPA; rather, we present it as one way of embedding feminist principles into a phenomenological hermeneutic analysis. Indeed, there are limitations within our process that we were not able to address. For example, it would have been interesting to show the visual metaphorical images to the participants and seek their reflections on them and the potential of these visual metaphors in capturing their experiences. This would have added another layer of hermeneutic interpretation as the participants could have interpreted our visual metaphorical interpretation of their individual and collective experiences, which they had also interpreted in the first and second interviews. However, due to logistical and time constraints, this additional layer of interpretation was not possible, thus, it would be beneficial for future research to carry out a similar analytical method, while building this additional interpretive layer in the process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdellatif, A. 2022. Women on Boards: An IPA Study of the Facilitators and Barriers to Women’s Representation on Boards Within the Egyptian Banking Sector. Newcastle: Northumbria University.

- Abdelzaher, A., and D. Abdelzaher. 2019. “Women on Boards and Firm Performance in Egypt: Post the Arab Spring.” The Journal of Developing Areas 53 (1): 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2019.0013

- Abdullah, S. N., K. N. I. K. Ismail, and L. Nachum. 2016. “Does Having Women on Boards Create Value? The Impact of Societal Perceptions and Corporate Governance in Emerging Markets.” Strategic Management Journal 37 (3): 466–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2352

- Ahmed, S. 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University.

- Akin, G., and E. Schultheiss. 1990. “Jazz Bands and Missionaries: OD Through Stories and Metaphor.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 5 (4): 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683949010142731

- Aldossari, M., and S. E. Murphy. 2023. “Inclusion Is in the Eye of the Beholder: A Relational Analysis of the Role of Gendered Moral Rationalities in Saudi Arabia.” Work, Employment and Society, in press.

- Annells, M. 1996. “Hermeneutic Phenomenology: Philosophical Perspectives and Current Use in Nursing Research.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 23 (4): 705–713. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb00041.x

- Avakian, S. 2020. “Nikos Kazantzakis’s Phenomenology and Its Relevance to the Study of Organizations.” Culture and Organization 26 (3): 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2019.1570195

- Bell, E., S. Meriläinen, S. Taylor, and J. Tienari. 2020. “Dangerous Knowledge: The Political, Personal, and Epistemological Promise of Feminist Research in Management and Organization Studies.” International Journal of Management Reviews 22 (2): 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12221

- Belova, O. 2006. “The Event of Seeing: A Phenomenological Perspective on Visual Sense-Making.” Culture and Organization 12 (2): 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759550600682866

- Berger, R. 2015. “Now I See It, Now I Don’t: Researcher’s Position and Reflexivity in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 15 (2): 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

- Berggren, K., and L. Gottzén. 2023. ““It’s Not Just Dad Who’s Got Problems”: Feminist Phenomenology and Young Men’s Violence Against Women.” Men and Masculinities 26 (3): 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X231183389

- Birt, L., S. Scott, D. Cavers, C. Campbell, and F. Walter. 2016. “Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation?” Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

- Boncori, I. 2022. Researching and Writing Differently. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Brannelly, T., and M. Barnes. 2022. Researching with Care: Applying Feminist Care Ethics to Research Practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Burgess-Proctor, A. 2015. “Methodological and Ethical Issues in Feminist Research with Abused Women: Reflections on Participants’ Vulnerability and Empowerment.” Women's Studies International Forum 48: 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.10.014

- Caicedo, M. H. 2011. “The Story of Us: On the Nexus Between Metaphor and Story in Writing Scientific Articles.” Culture and Organization 17 (5): 403–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2011.622902

- Calás, M. B., and L. Smircich. 2006. “From the ‘Woman’s Point of View’ Ten Years Later: Towards a Feminist Organization Studies.” In The SAGE Handbook of Organization Studies, edited by S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, and W. R. Nord, 284–346. London: SAGE.

- Cassidy, E., F. Reynolds, S. Naylor, and L. De Souza. 2011. “Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis to Inform Physiotherapy Practice: An Introduction with Reference to the Lived Experience of Cerebellar Ataxia.” Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 27 (4): 263–277. https://doi.org/10.3109/09593985.2010.488278

- Cho, J., and A. Trent. 2006. “Validity in Qualitative Research Revisited.” Qualitative Research 6 (3): 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106065006

- Clifford, G., G. Craig, and C. Mccourt. 2019. ““Am iz Kwiin” (I’m his Queen): Combining Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis with a Feminist Approach to Work with Gems in a Resource-Constrained Setting.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 16 (2): 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1543048

- Cohen, J. A., A. Kassan, K. Wada, and M. Suehn. 2022. “The Personal and the Political: How a Feminist Standpoint Theory Epistemology Guided an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 19 (4): 917–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2021.1957047

- Cope, J. 2011. “Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretative phenomenological analysis.” Journal of Business Venturing 26 (6): 604–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.06.002

- Daley, A. 2010. “Reflections on Reflexivity and Critical Reflection as Critical Research Practices.” Affilia 25 (1): 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109909354981

- de Beauvoir, S. 2009. The Second Sex. translated by: Borde, C. and Malovany-Chevallier, S. (1949). New York: Vintage Books.

- Doyle, S. 2007. “Member Checking with Older Women: A Framework for Negotiating Meaning.” Health Care for Women International 28 (10): 888–908. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330701615325

- Easterby-Smith, M. P., R. Thorpe, and P. Jackson. 2008. Management Research: Theory and Research. London: SAGE.

- Eatough, V., and J. A. Smith. 2017. “Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, edited by C. Willig, and W. Stainton-Rogers, 194–212. London: Sage.