Abstract

Adopting the format of an edited and annotated conversation, Danish researcher and designer Rosa Tolnov Clausen, American artist and professor Marianne Fairbanks and British writer and professor Jessica Hemmings discuss some of the circumstances in which community hand weaving projects may flourish. Decisions around the types of space Clausen’s Weaving Kiosk (2017–ongoing) and Fairbanks’s Weaving Lab (2016–ongoing) have occupied, how hand weaving may be made portable, the impact of duration and responsibility toward the material, as well as social, outcomes are discussed. While our conversation tries to understand what is shared by the Kiosk and Lab, we also acknowledge where different cultural and historical contexts cause the potential and challenges of these two initiatives to differ. The Weaving Kiosk and Weaving Lab are not intended as performances, but instead place emphasis on how hand weaving may build social connections. The format of this article foregrounds the conversational nature of social hand weaving and hopefully offers inspiration to others interested in expanding the purpose of contemporary hand weaving and textile scholarship.

In their introduction to the “Crafting Community” issue of this journal published in 2016, Canadians Kirsty Robertson and Lisa Vinebaum write:

We argue that one of the most profound recent developments in the field of contemporary fiber is a substantial shift in site from private space to public space, away from the domestic sphere, and into public sites such as cafés, pubs and bars, storefronts, galleries, public transportation, the streets, and cyberspace. What is more, knitting, sewing, crochet, and even weaving in public spaces is most often undertaken by groups of individuals, marking a parallel shift away from the individual maker. We contend that these public, collective types of making also have a performative bent, transforming public spaces into shared, dynamic, communal social space (Citation2016, 5).

In the edited and annotated conversation that follows, Danish researcher and designer Rosa Tolnov Clausen, American artist and professor Marianne Fairbanks and I tackle some of the circumstances in which community hand weaving projects may flourish, in an effort to understand more clearly their potential. We focus on two specific initiatives: Clausen’s Weaving Kiosks (2017–ongoing) and Fairbanks’s Weaving Lab (Citation2016–ongoing), both of which exemplify Robertson and Vinebaum’s observations of a shift in craft practices from private to public space, occurring with groups rather than solitary makers.

We address some of the challenges and potentials even weaving offers—a clause Robertson and Vinebaum understandably used because looms are one of the least transportable textile tools. Decisions around the types of space the Kiosk and Lab have occupied, how hand weaving can be made portable, the impact of duration and responsibility toward the material, as well as social, outcomes are discussed. We hope that sharing these experiences may offer inspiration to others interested in expanding the purpose of contemporary hand weaving. While our conversation tries to understand what is shared by the Kiosk and Lab, we also acknowledge where different cultural and historical contexts cause the potential and challenges of these two initiatives to differ.

Moving weaving out of the studio or factory and into public spaces is not a new strategy. Performative hand weaving projects have long shared an attention to the meaning of weaving, but without necessarily always emphasizing the production of cloth. One of the most well cited examples is the performance Slumber (1993) by American artist Janine Antoni who hand wove by day a cloth patterned with a translation of data from her eye movements gathered during her sleeping hours.Footnote1 Other experiments with the use of weaving as an action and performance include early works using tapestry by British artist Shelly Goldsmith such as Dew Point (2000) which involved unpicking her tapestry weaving in the gallery over the course of six week exhibitionFootnote2; Scottish artist Susan Mowatt’s explorations of drawing and unweaving of tapestryFootnote3; Japanese-German artist Yuka Oyama’s performance The Stubborn Life of Objects #03 The Weaver (2015)Footnote4; American Indira Allegra’s BODYWARP series (2017–2019)Footnote5; Interlace, textile research by the Dutch designer Hella JongeriusFootnote6; and American artist HM’s explorations of weaving and walking as part of a 2020 Guggenheim Fellowship.Footnote7

Where several decades ago works such as Antoni’s Slumber (1993) and Goldsmith’s Dew Point (2000) focused on making solitary production visible in the gallery space, more recent initiatives have increasingly worked to include the public or an audience.Footnote8 These recent examples arguably exemplify a growing trend toward forms of collaborative practice noted by Robertson and Vinebaum that are now familiar across the arts. While these examples share an interest in the meaning of weaving, a key distinction exists between projects that refer to woven cloth and the tools of weaving, versus practices that involve the literal production of cloth.

In Citation2012, Claire Bishop wrote in her introduction to the now well quoted book Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship:

To put it simply: the artist is conceived less as an individual producer of discrete objects than as a collaborator and producer of situations; the work of art as a finite, portable, commodifiable product is reconceived as an ongoing or long-term project with an unclear beginning and end; while the audience, previously conceived as a ‘viewer’ or ‘beholder’, is now repositioned as a co-producer or participant […] these shifts are often more powerful as ideals than as actualized realities, but they all aim to place pressure on conventional modes of artistic production and consumption. (Citation2012, loc 76–77)

While Bishop’s observations remain pertinent today, the fundamental difference between the examples she discusses and the focus here is that the “actualized reality”—the very stuff of material and community making—of Clausen’s Weaving Kiosk and Fairbank’s Weaving Lab go beyond the rehearsal of ideals to make real social and material change.

Several antecedents to the Weaving Kiosk and Weaving Lab have emerged since the weaving performances by artists such as Antoni and Goldsmith. American Anne Wilson’s Wind-Up: Walking the Warp (2008) at the Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago followed by Local Industry (2010) at the Knoxville Museum of ArtFootnote9 first wound a warp and later, with a community of volunteer weavers and no financial exchange for time or materials, hand wove a seventy-five feet nine inch long textile. (Molinski Citation2011, 4). Where Wilson worked with specific local histories, American artist Travis Meinolf (Citation2019) has explored a pop-up approach to weaving. When based in Berlin, Meinolf adapted his counterbalance floor loom for transport by adding wheels, allowing him to teach workshops in fields, on bridges and in train stations (Hemmings Citation2012, 125). Since returning to his native California, he has run workshops using backstrap loomsFootnote10 which “must be attached to trees, bodies, or other structures and require the collective participation of viewers to function properly, thereby linking them in a temporary social bond” (Robertson and Vinebaum Citation2016, 5). Recently Meinolf has held public weaving events on a contested site in his local area - land which was once a golf course that some residents advocate should now become a public park (Meinolf, Citation2020).

Like Wilson and Meinolf, Clausen’s Weaving Kiosk and Fairbank’s Weaving Lab produce cloth. But their reasons for doing so differ. Launched in February 2017, nine iterations of Clausen’s Weaving Kiosk in four Nordic cities (Stockholm, Helsinki, Copenhagen and Reykjavik) have occupied public spaces where weaving tools, materials and product proposals are made available. Participants in a Weaving Kiosk are invited to use the available samples as inspiration or production guidelines. The Weaving Kiosk began in 2017, before the start of Clausen’s PhD at the University of Gothenburg. Since running the Kiosk from within her PhD research, Clausen cites a greater emphasis on her contextualization of the Kiosk in relation to other examples of participatory practice.Footnote11

Weaving Lab, launched in Madison, Wisconsin, USA, first ran for three months in the summers of 2016 and 2017. Two-week versions of the Lab traveled to Oak Park, Illinois, Oslo, Norway, Copenhagen, Denmark and Gothenburg, Sweden in 2019. Fairbanks describes the Lab as a social space, combining inquiry and informal conversations, and considers historical models of local production to ask whether access to looms as a social destination might create a contemporary analog to the “fireside industries.” The Lab invites participants to approach weaving as an end in itself, and to consider weaving in relation to time, rhythm, meditation, materiality, pattern, and process. In the dialogue that follows, the importance of weaving as an action rather than an object differs. Neither the Weaving Kiosk or Weaving Lab are intended as performances, but both share an emphasis on the social and, as we came to learn through our conversation, the importance of duration.

Jessica: Your projects seem motivated to ensure weaving is not treated as specialist knowledge. How did weaving come to have such a significant place in your practices?

Marianne: My journey to weaving has many starts and stops. When I was an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, I met Sherry Smith who was my main Fibers professor. She is a weaver with amazing technical skills. Between my studies and working for two years as Smith’s studio assistant, weaving became ingrained in how I could understand things. After that, I knew I loved Fibers and it was the way that I wanted to work. When I went to graduate school, I stepped back from Fibers specific work and started doing collaborative work and social practice. Years later, when I came to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I came back to weaving with fresh eyes.

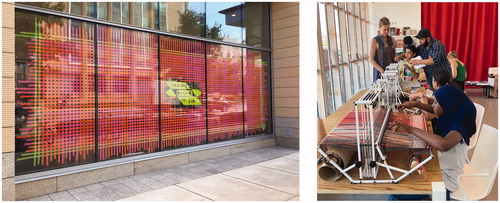

Where I teach now is within the School of Human Ecology, which historically was called the School of Home EconomicsFootnote12 and focused on the domestic and utilitarian histories of weaving.Footnote13 As a student of Sherry Smith, weaving was as an art form. In the intervening years it was social practice that fed me, and that was the lens that I brought to weaving. Weaving Lab () became a way for me to blend the production, domestic and utilitarian side with my interests in social practice and invention.

Rosa: My interest for weaving started during my exchange studies at the Kunsthochschule Berlin Weissensee, from Kolding School of Design in Denmark. During a weaving course I took in Berlin I felt as if something fell into place. The social practice perspective came later, when I started working with Blindes ArbejdeFootnote14 in Denmark as part of my master thesis at Kolding. As an obligatory part of the thesis project each student had to work with a collaborative partner outside the school. I wanted to work with textile production in Denmark, and one of the few remaining places I found was Blindes Arbejde, an organization for social-economic craft production that employs blind and visually impaired craftsmen in brush and broom binding, restoring Danish design furniture classics and hand weaving. The time I spent in the weaving workshop there made me aware of how hand weaving and the weaving workshop meant a lot of different things for the weavers beyond the physical product. It was this understanding that made me focus my practice more on designing and facilitating weaving spaces for other people.

Jessica: The titles of your projects – the Weaving Kiosk [Rosa] and the Weaving Lab [Marianne] – suggest a particular purpose for these spaces?

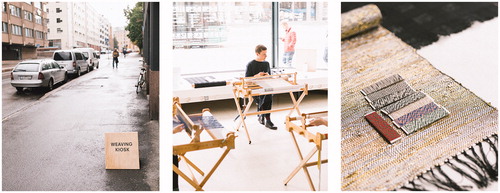

Rosa: My interest with the title was to disrupt some of the associations that exist about weaving, such as it being an unquestionably technically difficult craft, or space and time consuming. The word kiosk connotes the convenience and accessibility of this weaving workshop in terms of space, location and process. And I was interested in visitors producing actual products by hand in order to insert this into commercial associations. The Kiosk as a market place seemed to suit ().

Marianne: At the University of Wisconsin-Madison there are labs filled with researchers working in the STEM fields. I wanted to position weaving research as something of equal importance to the research in other major labs around campus. A Weaving Lab could be a space to explore new ideas about weaving and collectively make and interrogate cloth.

It took me a while to come to the revelation that I wanted the people who visited the Lab to be acknowledged as researchers, to reflect their own participation as scholarship. Part of the project that is very important to me is that we understand craft, materiality and process as knowledge and research. I love the technical aspects of math and pattern systems and the algorithms in weaving. They are applied in a very physical way with the intersection of threads.

Jessica: Do either of you feel the need to work against weaving stereotypes? Marianne, you mentioned some of the earliest associations in your contexts coming out of home economics. Rosa, has sloydFootnote15 been an influence in the regions where you work?

Rosa: Yes, the motivation behind the Weaving Kiosk was to show hand weaving in a new light. The loom, compared to a pair of knitting needles, is an investment in terms of money, time and space. In most of the big cities in the Nordic countries there are weaving facilities but they often are not directly visible on street level because of their limited commercial capacity. These spaces offer different entry points to weaving, usually through a course. Committing to a weekly weaving course is today difficult for many people and there are certain steps that you seem to have to learn to weave the right way. My hypothesis is that this prevents some people from even trying to weave. A very strict, rule-bound approach was not how I learned to weave. In my education in both Kolding and Berlin we were encouraged to sit down at a loom and experiment. In the semester before I did my thesis project, I went on exchange to Aalto University in Helsinki to get a better understanding of weaving theory. I feel that the way I started weaving means that I am convinced that with enough time I can do anything on the loom.

I became interested in exploring what would happen if I created a number of weaving spaces in Nordic cities that would be visible on the street level and easy to access both spatially and technically, where no right or wrong was taught and where participants would only have to commit to the weaving process depending on the duration of their production. Instead of instructions in the traditional form I provide proposals for products that not only interact with current fashion but also invite interpretation.Footnote16

Jessica: I am realizing that although you both described different educational routes into weaving, you share a common strength. Marianne, you said that your first experience with weaving used it as an artistic practice which required a high level of technical competence, but was not necessarily design training. Rosa, you enjoyed a design education but had a particular weaving interest which required self-teaching. Your technical expertise has allowed you to see new alternatives for weaving.

You have both made considerable efforts to make the Kiosks and Labs your coordinate mobile. How would you explain the importance of the physical environments of your projects to empower weaving?

Marianne: Originally, the Wisconsin Institute of Discovery hosted the Weaving Lab. It was a central space on campus, and it ran five days a week, for three months, for two consecutive summers. What was exceptional was that during those months people came consistently. I was able to achieve my goal to have people visit not just once, but again and again and have ongoing conversations.

In hindsight I think the duration is more important than I had originally understood. In the summer of 2019, I ran a pop-up version of the Lab in Oslo, Copenhagen and Gothenburg. The project engaged an audience in each space in ways that seemed atypical for the programming usually offered in those venues. And yet, the shorter two-week durations did not support one goal of the project, which is to build more social spaces that can attract people again and again, and facilitate ongoing conversations and a sense of community.

What is hard to quantify is how people take the experience of the Lab and continue to find ways to incorporate making into their daily lives. How has their experience of the Weaving Lab changed how they think about textiles? Weaving? Process? Making? Craft? Art? I have questions around the impact of the project on the individual and how the venue informs the researcher’s experience. Personally, I do not want to be in spaces that are already deemed craft workshops because I would prefer to subvert expectations.

Jessica: It can be difficult today to ask others for their time to do anything, let alone make return visits. Rosa, I understand you have been reluctant to require people to sign up for participation in the Weaving Kiosks. Marianne, from your experience in Wisconsin, do you have any insights into what drives repeat visits?

Marianne: It seems that having a good location is key and in Wisconsin the building was in the center of the campus with people walking through. One of my favorite examples of a return visitor is this fourteen-year old kid who had summer camp on campus and every day after camp he would come by – every day!

My experience comes from running Mess HallFootnote17 in Chicago (2003–2013) which was a small event-based art space which was located in a storefront and benefited from being near good public transportation and lots of walking traffic. Since then, I have often wondered how artists could activate empty retail spaces for short durations.Footnote18 If spaces were thought of as a temporary resource that could be activated by artists, the community and the landlords would benefit.

Jessica: Rosa, how would you describe the impact different settings have had on the Kiosks?

Rosa: I have also noticed how my weaving spaces change character depending on duration. There have been two approaches to longer durations that have worked especially well. The Weaving Kiosk in Stockholm (Feb. 1−25, 2017) was in the same space for nearly a month. Every day there were more people who had heard about the Kiosk, and many people came back a couple of times. The other approach we used in Helsinki was a series of six Kiosks of varying length that took place in intervals of approximately two months around the city. These were announced through Facebook. Facebook became the permanent location of the Kiosk and participants moved around in the city to each new venue. The Kiosks were treated as one, despite the locations not being the same.

Storefronts are expensive and difficult to get, but because of the mobility of the Weaving Kiosk, I can set it up or dismantle it in a couple of hours. That has made it easy to ask places with storefronts to borrow their space, for example during a holiday period. I get a visible weaving space and they get part of their rent paid even when they were closed. There are some very interesting potentials in thinking about real estate and weaving spaces in this way.

Jessica: You both refer to your projects as flexible and have made particular decisions and adjustments to make weaving portable. Marianne, do you want to mention some of the ways that you first made weaving not just portable but even pocketable?

Marianne: This question of portability was actually quite easy in Madison because I could take the floor loom, put it on some wheels, and roll it down the street to another venue. Despite wheeling the looms down the street, the first Lab was made up of floor looms and in fact wasn’t particularly portable. From observing visitors stopping but not having a lot of time to stay, I wanted them to engage with weaving, even if it wasn’t in the Lab – a takeaway that someone could bring home in their pocket. With a laser cutter and some material tests, I started on prototypes that would have everything necessary to weave, like needles and a comb. First called Pocket Loom because of the cell phone size, I now call it Hello Loom because I like to think of weaving as a way of making a message.

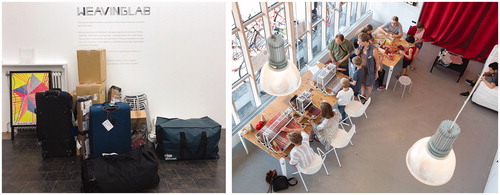

Taking the Weaving Lab to Scandinavia in the summer of 2019 was a big transition and one large challenge was to figure out how to get looms across an ocean ().Footnote19 The floor loom is a bulky tool but felt like a critical component of the Lab. It is a simple tool with harness systems and treadles that provide thousands of possible pattern options. The way it is engineered and then activated by the weaver’s body is so holistic, engaging mind, hands and feet. I wanted to make sure participants could have experience of using their whole body at the loom because the process is quite magical. For the international travel, I was not able to ship the looms but worked hard to make connections and found some generous individuals that graciously lent me some floor looms.

Jessica: Rosa, you have also made specific decisions about the types of looms in the Kiosks?

Rosa: The Kiosk started from the practical question: How do I make hand weaving visible and accessible in northern European cities? I knew I had a car available and that it is possible to travel between most of these countries by car, so the Kiosk developed particularly with a focus on what a Ford Tourneo Connect can contain. I defined what elements were important to have in a weaving workshop – looms, shelves, tables, sewing machines, yarn and other tools – and then choose or developed, together with designer Martin Born, the elements that fit my purpose and the space of my carFootnote20 ().

Jessica: A Weaving Kiosk to fit a small van!

Rosa: Yes, all elements of the Kiosk are modular, so if it makes sense to only bring two looms and part of the shelf that is also possible.Footnote21 This means I was also able to take the Kiosk with me on the airplane when I went to Iceland. I chose to work with rigid heddle loom by LervadFootnote22 because it is light, easy to assemble, transport and use, and allows for the production of rather large pieces of cloth.

I have never seen the Kiosk as something permanent, more as a seed for something to grow out of. Visitors may see and imagine having a loom at home. In the Nordic countries, we do not see looms in everyday life, but they are around. I wanted to place weaving right in front of people so they cannot avoid it. Then we can start speaking about all the looms and possibilities for weaving.

Marianne: I agree! The Weaving Lab makes five looms visible, and I think the magic and the demystification are part of what I love. I want participants to sit down and weave but also see what small-scale production might look and sound like. The Weaving Lab triggers memories and stories, often about what knowledge of weaving was around.

Jessica: There is a risk when you are inside an arts department or a creative community of preaching to the converted. How do you reach new audiences?

Rosa: The changing location of the Weaving Kiosk, especially in Helsinki, has meant that people of different demographic backgrounds have visited and been able to weave. Of course, people who are already interested in weaving come by, but given that the weaving process is so easy to master using rigid heddle looms, experienced weavers do not necessarily have an advantage over a person with little or no weaving experience. This means that there is no hierarchy in the Weaving Kiosk – no particularly bad or good weavers.

The accessibility of the space and weaving process, as well as not being obliged to invest a lot of time and money as a visitor in the Kiosk has, I think, also been important in order to attract a wide audience. You do not have to be a passionate weaver to take part; it is fine to be in the space for just a couple of hours.

Marianne: Many research labs on campus are focused on the invention of new technology; my Lab as a social practice focuses on the value of creativity and community. While the idea of a lab might be ordinary on a campus, the public and participatory nature of the Weaving Lab is less expected.

When the Lab traveled and gained exposure to international audiences in art-based spaces it seemed like we were able to interact with both audiences who came because they were interested in weaving and those who had little knowledge of the form. Traveling internationally with the Lab made me keenly aware of what it means to be the host which is something that I know Rosa is often thinking about (Clausen Citation2020). With two of my assistantsFootnote23 we brought the project to life in Oslo and Copenhagen where we started recognizing our American sensibilities and mannerisms. For the first time I realized how people were not used to the way that we would invite them in or offer them a participatory experience. In a gallery people walk in and they expect a certain look and to have a hands-off experience. Here we are saying, “would you like to sit down and learn how to weave?” We really worked to get them to participate in ways that felt most comfortable. When running the Lab in the USA, our role as hosts seemed to be informed by both the context of education but also the sales or service industry, as we all had previous experiences working in those arenas. I think once we were in another country, our cultural specificities played a large role in how the project was perceived.

Jessica: Much of this conversation has focused on the spaces and duration of portable weaving events. Projects that are primarily focused on community and social contributions have inescapable material outcomes that also demand our responsibility. How have you worked with questions of ownership in collective weaving?

Rosa: With the Kiosk the product was in focus from the beginning. I was interested in seeing whether we could get people to make things that they would actually like and use. I have been working with Merja Hannele Ulvinen, a fashion designer, on the product proposals for the Weaving Kiosk that can be produced within a reasonable timeframe and considered fashionable. We spend a lot of time helping people transform their textiles into products. In the future, I want to involve the weavers in finishing and sewing, which can create an even stronger sense of skill as well as pride and ownership.

Marianne: In Weaving Lab, the focus is less on the product and more on the process. There are multiple prompts I invite around weaving, including time, meditation, math, production, and sound. Some of the promptsFootnote24 require signing up for one hour and others are drop in. The prompts that have many hands weaving the same cloth become part of a collective production. Other longer durational weaving produces a single result that I document and offer to the participant. I tell them ahead of time that they will receive the weaving upon completion and people are happy to sign up for an experience without the end product being the main focus.

Jessica: Rosa and Marianne, thank you.

Figure 1 Weaving Lab, 2017 (exterior), Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, Madison, WI, Flagging tape, adhesive, vinyl signage, Photo by Marianne Fairbanks. Weaving Lab, 2019 (interior), Copenhagen Contemporary, Photo by Lara Kastner.

Figure 2 Weaving Kiosk, 2018 (exterior), Kalleria, Helsinki, Photo by Johannes Romppanen. Weaving Kiosk, 2018 (interior), The Nordic Culture Point, Helsinki, Photo by Johannes Romppanen. Weaving Kiosk textile, The Nordic Culture Point, Helsinki, 2018, Photo by Johannes Romppanen.

Figur 3 Weaving Lab materials packed up, 2019, Oslo, Norway, RAM Galleri. Weaving Lab materials unpacked, 2019, Copenhagen Contemporary, Photo by Lara Kastner.

Editing, annotating, rereading and revising the above dialogue brought topics into focus which were not apparent to us at the beginning of this conversation. Duration offers social hand weaving projects a different relationship with participants to what a one-off event can create. Attention to this has come into greater clarity only through this conversation. Much like the workshop participants who recognize that hand weaving is an invitation to think and act in a more intentional and methodical manner, our conversation has also exposed the quandary of how best to understand the impact of each iteration of the Weaving Kiosk and Weaving Lab. Bishop recognized, in reference to participatory art, that projects which unfold over time “tend to value what is invisible: a group dynamic, a social situation, a change of energy, a raised consciousness. As a result, it is an art dependent on first-hand experience, and preferably over a long duration (days, months or even years)” (Bishop Citation2012, loc 151). While the Weaving Kiosk, in particular, differs from Bishop’s description that “participatory art is often at pains to emphasize process over a definitive image, concept or object” both the Kiosk and the Lab share a particular research challenge: “very few observers are in a position to take such an overview of long-term participatory projects: students and researchers are usually reliant on accounts provided by the artist, the curator, and handful of assistants, and if they are lucky, maybe some of the participants” (Bishop Citation2012, loc 151–157).

Reflection requires a decompression time of its own—most particularly for those directly involved with the planning and delivery of a public event. But this need for reflection runs against the acknowledged benefit of creating events of a longer duration that build participants expectation and planning for the next event—or as Meinolf succinctly explains, the opportunity to be able to say, “come next time” (Meinolf Citation2020). Untangling cause and effect can be difficult in dynamic circumstances where the number of variables is constantly changing and the organizer is unable to gain critical distance from their own creation. This makes decisions regarding the ways these projects may develop in future often feel murky and even dictated to a large degree by chance (the next invitation, opportunity to use a space, or empty time on the calendar)—sentiments that do not fit with the sheer amount of time, energy and care that goes into launching and delivering each project iteration. While socially oriented projects such as the Weaving Kiosk and Weaving Lab focus their energies on what may be best for participants, further questions around the sustainability of delivery for those who conceive of and organize such events is an additional area that deserves serious consideration. Until then, we can try our best to remember that social hand weaving initiatives are extraordinarily context sensitive. Much like cloth itself, they not only require, but also have great capacity, to accommodate a constant need to adapt and adjust.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jessica Hemmings

Jessica Hemmings writes about textiles. She is currently Professor of Craft and Vice-Prefekt of Research at HDK-Valand, University of Gothenburg, Sweden and the Rita Bolland Fellow at the Research Center for Material Culture in the Netherlands (2020–2021). www.jessicahemmings.com [email protected]

Rosa Tolnov Clausen

Rosa Tolnov Clausen is a Danish textile designer and PhD student in the field of Crafts at University of Gothenburg in Sweden. Her creative practice oscillates between the fields of craft and design. She creates physical spaces about the practice of hand weaving, using the craft as a catalyst for physical, social and creative interaction. Her PhD research seeks to understand the motivations for hand weaving in the Nordic region today and to spatially speculate on the how hand weaving process can take place. www.rosatolnovclausen.com

Marianne Fairbanks

Marianne Fairbanks is a visual artist, designer, and Associate Professor of Design Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and her BFA from the University of Michigan. Her work spans the fields of art, design, and social practice, seeking to chart new material and conceptual territories, to innovate solution-based design, and to foster fresh modes of cultural production. www.mariannefairbanks.com www.weavinglab.com

Notes

1 JH: “Antoni transforms the fleeting act of dreaming into a sculptural process. Between 1994 and 2000, the artist slept while an electroencephalograph machine recorded her eye movement. During the day, Antoni would sit at the loom and weave shreds of her nightgown in the pattern of her REM. The patterns were woven into the blanket that covered the bed where the artist as [sic] she slept at night” (Antoni Citation2020).

2 JH: Shelly Goldsmith’s Dew Point (2000) was unwoven by the artist between January and March of 2000 in the British Crafts Council Gallery, London as part of the exhibition Ripe curated by Louise Taylor.

3 JH: Susan Mowatt explains of her solo exhibition Weaving Home at GalleryGallery, Kyoto, Japan in February 2012: “In this work I explore themes of slowness, materiality, non-permanence, mindfulness and making. People viewing the exhibition see someone slowly performing a simple task, five floors above one of the busiest intersections in Kyoto’s shopping district.” (Email correspondence with Jessica Hemmings on 14 April 2020.) Elsewhere Mowatt describes her interest in “weaving tapestries [that] could be relevant in the twenty-first century in a world which is so fast paced and immediate because [tapestry weaving] is a very long, laborious, repetitious process (which I like).” https://www.johngraycentre.org/about/museums-service/exhibitions/east-lothian-visual-artists-and-craft-makers-awards-a-retrospective-exhibition/susan-mowatt/ (accessed March 11, 2020).

4 JH: Writing of “The Weaver” as part of her Norwegian Artistic Research Fellowship (2012–2017) Yuka Oyama reflects: “With this piece I aimed to emphasize the merging of an object into a person and vice versa. For instance, musical instruments almost become a part of musicians’ bodies, jewellers and their tools create jewellery pieces, and weavers and looms cooperate to weave.” See Oyama (Citation2017, 75).

5 JH: “BODYWARP explores weaving as performance and calls for a unique receptivity to tensions in political and emotional spaces. The work investigates looms as frames through which I as the weaver become the warp and am held under tension, as I perform a series of site-specific interventions using my body. Like the accumulation of memory on cloth, in BODYWARP, looms and other tools of the weaver’s craft become organs of memory, pulling my body into an intimate choreography involving maker, tools and the narrative of a place” (Allegra Citation2020).

6 JH: Hella Jongerius’s solo exhibition “Interlace, textile research” was exhibited by Lafayette Anticipations in 2019. See Kvadrat (Citation2020).

7 JH: See Mirra (Citation2020).

8 JH: Kirsty Darlaston (Citation2011, ii) introduces her research by writing: “As the weaver/researcher, I set up a loom at a local library and wove a community tapestry over a period of two years recording the conversations that I had with community library-users at the loom […] The key themes that emerged from the conversations at the loom centred on the relationship between making and time; craft as work; the makers endurance and the body of the maker as a site of pain; the ‘cleverness’ of making; and the embodied experience of beauty, as well as the force of craft in storytelling and memory.”

9 JH: Analysis of Anne Wilson’s (Citation2019) work has been published extensively, including the exhibition catalogue: Susan Snodgrass (Citation2011) and Lisa Vinebaum (Citation2016).

10 JH: Backstrap looms are one of the most portable systems available to create woven cloth. Thought to have originated in Asia, backstop looms are used in weaving traditions found around the world including the subcontinent of India, central and south America and countries such as Indonesia and Japan.

11 RC: For further reading see Bishop (2012), Kouhia (Citation2016), Waldén (Citation1994), Clausen (Citation2020), Illich (Citation1973), Moeran (Citation2007), Hastrup (Citation1992), Jungnickel (Citation2018) and Star (Citation2007).

12 MF: The School of Human Ecology originated as the Department of Home Economics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1903. The school changed its name to the School of Human Ecology (SoHE) in 1997 (Meg McMahon Citation2017).

13 JH: Lisa Vinebaum notes: “Fairbanks also draws inspiration from collaborative craft educations in the US, like settlement schools, and from Appalachian weaving cooperatives like Fireside Industries and Berea College – initiatives that emphasized individual creation for economic gain together with mutual aid.” See Lisa Vinebaum (Citation2019, 32).

14 RC: Blindes Arbejde [Work by the Blind] is a business-run foundation founded in 1929. https://www.blindesarbejde.dk/om-blindes-arbejde/ (accessed March 10, 2020).

15 JH: See Otto Salomon (Citation2010, 11). Robertson and Vinebaum similarly recognize historical antecedents for the current social craft trend in their introduction to the Crafting Community issue of this journal.

16 RC: Similar to the Japanese weaving philosophy Saori, which is characterized by the idea that everyone can weave and that mistakes in the weave should be embraced and even emphasized; imperfection and mistakes are an expression of self. See more Saori Global Official Website (Citation2020).

17 MF: Mess Hall was an experimental cultural center in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago (2003–2013) where visual art, radical politics, creative urban planning, and applied ecological design informed each other. The initiative was founded by Temporary Services, Ava Bromberg, Marianne Fairbanks & Jane Palmer, Sam Gould, and Dan S. Wang. See https://temporaryservices.org/served/mess-hall/ (accessed March 8, 2020).

18 MF: While there might not be an exact model for how artists can do this, I was inspired by the work of Ken Dunn who established City Farm in Chicago, Illinois. See https://cityfarmchicago.org/ (accessed March 11, 2020].

19 MF: For the Weaving Lab at the Röhsska Museum of Craft and Design in Gothenburg, Sweden, all of the yarns and textiles had to be frozen so that the museum could ensure that we were not introducing pests to the museum.

20 RC: Portable looms are not a new invention. Margaret Olofsson Bergman (b. 1872), for example, patented not only the Bergman Floor loom, but also the Bergman Suitcase loom. See Bergman suitcaseloom (Citation2020).

21 The furniture for the Weaving Kiosk was developed and built by designer Martin Born.

22 The Lervad rigid heddle looms were manufactured by Danish maker Lervad through the 1980s. Read more about the use of the rigid heddle loom in the Weaving Kiosk in “Having Visits - Considerations on the researcher-as-host in participatory projects” Clausen (Citation2020).

23 MF: Erica Hess and Kat Bunke traveled with the Lab as assistants in August of 2019 at RAM Galleri in Oslo, Norway and Copenhagen Contemporary in Copenhagen, Denmark. Kat Bunke also assisted in October, 2019 at the Röhsska Museum of Craft and Design in Gothenburg, Sweden.

24 MF: Loom 1: Chaos and Structure (washcloth); Loom 2: Collective Production (bolt); Loom 3: Math based patterning systems-color relationships (pillows); Loom 4: Weaving Sounds—With Joseph Adamik (towels) 1 hour durational (must sign up); Loom 5: Meditation (rugs).

References

- Allegra, I. 2020. Accessed 7 March 2020. https://www.indiraallegra.com.

- Antoni, J. 2020. Accessed 8 March 2020. http://www.janineantoni.net/#/slumber/.

- Bergman suitcaseloom. 2020. Accessed 10 March 2020. https://nordicmuseum.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/58D37B09-3F66-4B9D-9ED3-152170762542

- Bishop, C. 2012. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso. Ebook.

- Clausen, R. T. 2020. “Having Visits: Considerations on the Researcher-as-Host in Participatory Projects.” Journal of Arts & Communities 10 (1&2): 109–127. doi:10.1386/jaac_00009_1.

- Darlaston, K. 2011. “The Loom as a Stage for Performing the Social and Cultural Meanings of Craft and Making.” PhD diss., University of South Australia.

- Hastrup, K. 1992. “Out of Anthropology: The Anthropologist as an Object of Dramatic Representation.” Cultural Anthropology 7 (3): 327–345. doi:10.1525/can.1992.7.3.02a00030.

- Hemmings, J. 2012. Warp & Weft: Woven Textiles in Fashion, Art and Interiors. London: Bloomsbury.

- Illich, I. 1973. Tools for Conviviality. London: Open forum series.

- Jungnickel, K. 2018. Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. London: Goldsmiths Press.

- Kouhia, A. 2016. “Unravelling the Meanings of Textile Hobby Crafts.” Ph.D., University of Helsinki.

- Kvadrat. 2020. Accessed 16 March 2020. http://kvadratinterwoven.com/interlace.

- “Meg McMahon.” 2017. Meg McMahon, August 10. Accessed 10 March 2020. https://sohe.wisc.edu/announcement/1900-1909/

- Meinolf, T. 2019. Accessed 30 September 2019. https://actionweavings.tumblr.com/

- Meinolf, T. 2020. Skype interview with Jessica Hemmings March 12.

- Mirra, H. 2020. Accessed 31 July 2020. https://www.gf.org/fellows/all-fellows/helen-mirra/

- Moeran, B. 2007. “From Participant Observation to Observant Participation: Anthropology, Fieldwork and Organizational Ethnography.” Creative Encounters Working Papers #2, Copenhagen Business School, July 2007. Accessed 7 February 2020. https://openarchive.cbs.dk/handle/10398/7038.

- Molinski, C. 2011. “Notes on an Exhibition.” In Anne Wilson Wind/Rewind/Weave, edited by Susan Snodgrass. Knoxville, TN: Knoxville Museum of Art and Whitewalls, Inc.

- Oyama, Y. 2017. “The Stubborn Life of Objects.” The Norwegian Artistic Research Fellowship Programme Diss., Oslo National Academy of the Arts and The Norwegian Artistic Research Fellowship Programme.

- Robertson, K., and L. Vinebaum. 2016. “Crafting Community.” Textile 14 (1): 2–13. doi:10.1080/14759756.2016.1084794.

- Salomon, O. 2010. “Introductory Remarks’, from the Teacher’s Handbook of Slöjd.” In The Craft Reader, edited by Glenn Admason, 11–15. Oxford: Berg.

- Saori Global Official Website. 2020. Accessed 7 December 2020. https://www.saoriglobal.com/home

- Snodgrass, S., ed. 2011. Anne Wilson Wind/Rewind/Weave. Knoxville, TN: Knoxville Museum of Art and Whitewalls, Inc.

- Star, S. L. 2007. “Living Grounded Theory Cognitive and Emotional Forms of Pragmatism.” In The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory, edited by Antony Bryant and Kathy Charmaz, 75–93. London: Sage. doi: https://dx-doi-org.ezproxy.ub.gu.se/10.4135/9781848607941.

- Vinebaum, L. 2016. “Performing Globalization in the Textile Industry: Anne Wilson and Mandy Cano Villalobos.” In The Handbook of Textile Culture, edited by Janis Jefferies, Diana Wood Conroy and Hazel Clark, 169–185. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

- Vinebaum, L. 2019. “Weaving Lab: Social + Science.” Surface Design Journal Summer: 30–35.

- Waldén, L. 1994. Handen Och Anden: de Textila Studiecirklarnas Hemligheter. Stockholm: Carlsson.

- Wilson, A. 2019. Accessed 30 September 2019. https://www.annewilsonartist.com/local-industry-overview.html.