?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The Cordillera region of the Northern Philippines features ethnolinguistic weaving traditions which are now moving towards extinction. A practitioner-led research project developed a weaving tool-kit to support the preservation of weaving traditions, but further questions regarding the status of women textile workers arose as a result. The habitus of the researcher as a part-time textile lecturer created an interweaving between the differing, yet connected project participant experiences. Discourse analysis of participant observation data, community workshop reflections and documentary photography enabled a methodology to evolve which articulates the raw understandings this research raised. A research question asked: How can craft generate economic opportunities and enhance livelihoods for women? The findings and end point of this article propose that Bourdieu’s theories of practice are a useful framework through which textile workers can understand more clearly the different forms of capital their roles embody.

Introduction

Textile postgraduate education embraces a range of education contexts and is an expansive professional field which includes industrial, artisan, craft and designer practices. The social and material nature of textiles is leading UK based academic programmes to undertake to make their textile courses decolonized and to be supportive of international collaboration, circular economies, and to address UN sustainable goals. Practitioners who research, practice and teach, are particularly well placed to undertake project opportunities such as the British Council Crafting Futures programme “which aims for a sustainable future through making and collaboration” (British Council Citation2021). An opportunity arose in 2018 for the author, who met the required programme characteristics to participate in a Crafting Futures project based in the weaving communities of the Northern Philippines Cordillera region. The project was entitled Creating a Sustainable Textile Future for Women: Digitizing Cordillera Weaving Tradition (CSTFW) and began with the research question How can craft generate economic opportunities and enhance livelihoods for women? The project involved a short research visit and follow up work which took eighteen months to complete, between 2018 and 2020. The author, while part of a larger project team, reflects personally in this article how practitioner reflection and structural research methods, can enable a complex picture of textile practice, research and education to be created.

The CSTFW project sought specifically to develop a weaving tool-kit to support the preservation of an extant weaving tradition. The creation of woven teaching samples developed from extant textile material enabled a new position from which to consider the role of textiles in relation to the “future of craft by understanding its value in our history, culture and world today” (British Council Citation2021). Within the Cordillera region of the Philippines and other global Crafting Futures contexts, elderly community artisans may be the last generation to pass on traditional craft knowledges in oral traditions. The CORDITEX project from the University of the Philippines Baguio led by Professor of Social Anthropology, Dr. Analyn Salvador-Amores established that there is a body of textile patterns which can no longer be woven by the Itneg ethnolinguistic community weavers who have traditionally woven cloth as part of their intangible cultural heritage. A cluster of Itneg communities still live in a lowland area named Manabo, near the Abra delta in the Cordillera region. The Itneg community during the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, from 1521 until the Philippine revolution in 1896–1897 were not recognized as a distinct population are were given the name Tinguian, along with all the other people from the Cordillera mountains.

The Itneg communities today preserve their culture through a hybrid of traditional practices and Christian religion. Itneg woven textiles are regarded specifically as testimonies of the Itneg culture with distinct floating warp and supplementary weft woven patterns celebrating Itneg life. Itneg weaving was initially constructed on nimble and transportable backstrap looms until the point where the Spanish colonizers introduced large European style floor looms. Itneg textiles such as funerary blankets are a feature of global museum collections and literature (Aquino Citation2005; Cole Citation1922; CORDITEX Citation2019; De las Penas and Salvador-Amores Citation2016; Eggan Citation1956; Johnson and Yushan Citation2012), however due to changes in culture and work practices, traditional Itneg weaving many methods, have been lost. The Crafting Futures programme supports British practitioners to participate in projects within international craft communities, with research questions posed to address problems which are connected to the losses of craft traditions and knowledges. Crafting Futures as a programme, has arisen within the decolonized paradigm shift and seeks to explore the definitions and boundaries of design (and craft) as they shift in global discourse (Crosby Citation2019, 63).

Design practitioners who have grown into research from creative practice origins and who are within the first six years of their first academic appointment, have been identified as in particular need of support to undertake research as Paul Rodgers AHRC Leadership Fellow in Design 2019 states: “this next generation of researchers need encouragement and support, now more than ever.” This article establishes that while there is an opportunity for practitioners, they may need additional support if they are to avoid treating participants and communities as an archive to be mined (Tuhiwai Smith Citation1999, 58). This article explores the perceptions and insights of a part-time textile practitioner-educator entering into this area of research: “Whether we are talking about non-exploitative methodology…or writing ethnography, we are talking about power—who has it, how it is used, for what purposes” (Wolf Citation1992, 133).

The Fetishization of Extant Knowledges and Cultures

The Cordillera region of the northern Philippines has a community-based weaving tradition identified as an ethnolinguistic culture which embodies language, culture, rituals, beliefs and practices. The Itneg community originated as forest dwellers from the mountains of the Cordillera and have preserved their practices through an oral culture despite periods of colonialization and relocation. Starting from the Spanish colonization, the introduction of western monetary systems, inter-community marriages and Christian churches have brought the outside into these once culturally and geographically isolated communities. The weavers who participated in the Crafting Futures programme come from communities now considered to be economically deprived, with many families living below the poverty line (Asian Development Bank Citation2002, 55) ().

Figure 1 Master Weaver Catalina Ablog of Mindoro, Vigan Ilocos Sur). Photo Credit: Kelly, R. (2019).

The Crafting Futures programme is seeking to support the craft traditions and autonomous life, which traditional communities such as the Itneg peoples represent. The economic and social concerns which affect the livelihoods of women living within the Cordillera region are complex (CORDITEX Citation2018) and the processes of capitalism and colonialism have created circumstances which have resulted in the decline of traditional community life (Asian Development Bank Citation2002, 27). The Cordillera is a place of natural wealth, but the region is promoted as a rich resource to foreign investors who have undertaken aggressive land development since the late nineteenth century (Singson Citation2014). Twenty of the poorest provinces in the Philippines are within the Cordillera region, where illiteracy and low educational attainment for women is commonplace. (Asian Development Bank Citation2002, 27). Commercial farming, chemical fertilizers and increased deforestation, have placed the biodiverse crops of the high wet lands (heirloom rice) and lowlands (cotton) in environmental jeopardy (Damian Citation2019; Glover and Stone Citation2018, 784; Kelly and Stephens Citation2019; Rodgers Citation2019a). Now, rare prized Philippine cotton is sold overseas before its seed has been planted (Gutierrez Citation2018).

The CSTFW project is exploring the livelihood and precarity of textile practices as structures which have the potential to be woven or constructed differently. While there has been a sustained impact on the intangible cultural heritages of the Cordillera (UNESCO Citation2012), there is evidence cited by Glover and Stone (Citation2018, 780), that through a mix of good fortune from the point when UNESCO recognized the Ifugao Rice Terraces as “in danger” (UNESCO Citation2012) that a commercial fetishization process of the Cordillera and its communities has begun. Historical anti-commodities such as heirloom rice and organic Philippine cotton have switched from low to high value produce and the knowledge which arises from Cordillera weaving practices is also being identified more formally as valuable intangible cultural heritage (Acabado and Martin Citation2020).

The CORDITEX project from the university of the Philippines Baguio led by Professor of Social Anthropology Dr. Analyn Salvador-Amores is a significant research project exploring the mathematical and scientific structures of the Itneg weaving tradition. Tim Ingold (Citation2011, 14) compares the anthropologist with the scientist as the differences between the etic which represents a neutral value free approach perspective against the emic, which “spells out the specific cultural meanings that people place upon it” (Ingold Citation2011, 14), so it is noteworthy that the CORDITEX interdisciplinary team comprises scientists, mathematicians and anthropologists and is bringing the etic and emic together. The British Council Crafting Futures programme promotes craft practices in an emic approach but there is a change emerging which is articulating the interdisciplinary nature of textile practice and textile research which favors etic research specifically within global traditional textile research (see FootnoteNote 1). Oral traditions practiced within the Cordillera combine distinct culturally specific knowledge systems, so when textile and craft traditions are researched by outsiders and are described using scientific discourse, the patterns, structures, tools, materials and methods become fetishized (Marx Citation1967 [1867] in Glover and Stone 2017): “If there are any icons here, they are diagrams rather than images” (Tedlock and Tedlock Citation1985, 121).

Reviving the Cordillera Weaving Tradition

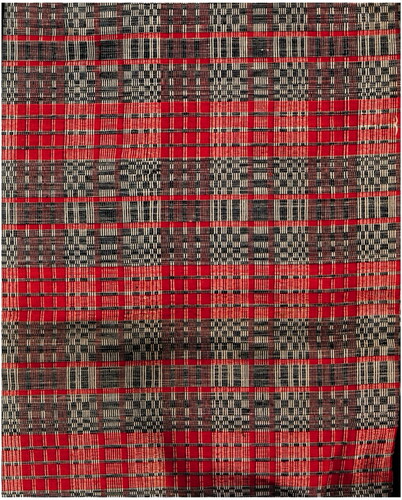

Periodic revivals in craft traditions have been identified by Peach (Citation2013,163) as a recurrent feature in times of change and uncertainty (). Anni Albers (Citation1941) described traditional handweaving thus… “It is true that such work is often no more than a romantic attempt to recall a temps perdu, a result rather of an attitude than of procedure”. The research undertaken by the CSTFW project (2019) identified that the diminishment of the Itneg weaving tradition is in part due to:

Figure 2 Adaptation of the traditional Pinilian supplementary weft method used by weavers based in Santiago, Ilocos Sur. Photo Credit: Kelly, R. (2019).

International research and study contributed to the removal of textiles, artifacts and tools from the Cordillera during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The textiles that are the concern of the CORDITEX and Crafting Futures project) were woven as burial cloths and the practice of extended rituals of burial within the Cordillera have diminished over the course of the twentieth century.

The oral tradition of weave teaching has diminished within the Cordilleran communities since the 1950s as a result of population decline and increase in overseas Philippine worker migration.

To date, weaving is not taught as a core or specialist subject within Philippines elementary, secondary school or higher education, this means that community-based weaving education is practiced informally.

The communities who use floor looms (rather than backstrap looms) repeat the use of warp and heddle configurations with no change to patterns or structure. The knowledge of the pattern structures could be said to be held within the loom.

This means that when a loom is dismantled, the pattern is also dismantled.

(Adapted from the CSTFW research report by Kelly, Kettle, and Stephens (Citation2019)

() features reflections of weavers who participated in a Crafting Futures development workshop held at the University of the Philippines Baguio. The weavers describe the act or ritual of weaving as a habitus (Bourdieu Citation2010; Grenfell Citation2012) meaning that weaving can enable a sense of identity in relation to community, place and within a social order. Rather than focus on the income or specific outcomes which weavers generate from their work, through workshop discussions, the weavers who participated in the project consider the benefits of weaving as being able to work independently to support their families, to work indoors during typhoons and to be able to raise their children. When women weave, they can impose an order on their lives and wellbeing and that can cease when they leave their looms.

Table 1. Extract taken from Creating a Sustainable Textile Future for Women report (Kelly, Kettle, and Stephens Citation2019).

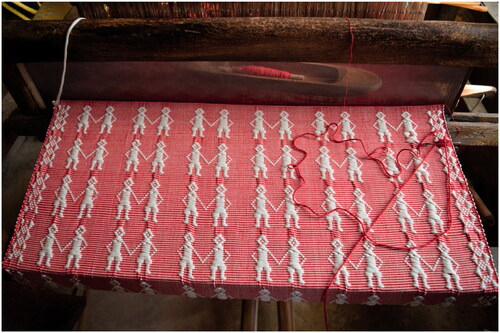

The Manabo weaving community which originate as Itneg ethnolinguistic speakers, comprised at the time of writing of four elderly women who are the last remaining master weavers of this community. The Manabo weavers have traditionally produced textiles distinct in connection to traditional belief systems and land. The Binakul Pattern () is representative of traditional stories and is reproduced from memory in a form of weaving meditation. When interviewed, the weavers said that their weaving work is very difficult and tiring on both mental and physical levels, but it is noteworthy that the elderly women we met were independent, socially active and are all still working as weavers.

Figure 3 Binakul old textile sample. Photo Credit: The CORDITEX Research Archive. The University of the Philippines, Baguio.

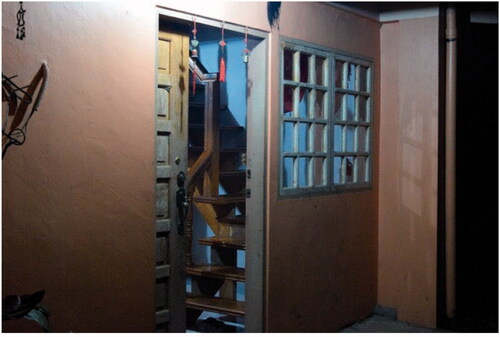

The Sabangan Weavers Association hail from the same linguistic origins as the Manabo community, but live near the sea at Mindoro, Vigan Ilocos Sur. Within this community we saw the direct affect which climate change and UN global challenges 1 (No poverty), 6 (clean water and sanitation) and 13 (climate action) (United Nations Citation2020) is having within such communities. The Sabangan community is at particular risk from sea erosion, and their homes were badly damaged as a result of the December 2018 typhoon. The Sabangan group comprise of three master weavers aged 85, 75 and 79 with an apprentice weaver aged 16, one of three young weavers we met. The apprentice is the granddaughter of Master Weaver Catalina Abalog, who learns beside her grandmother, learning through an oral teaching process ().

Figure 4 A weaver’s view to their garden from her typhoon ravaged home. Photo Credit: Kelly, R. (2019).

There appeared to be high levels of actualizing (Maslow Citation1943) and a notable wellbeing amongst the weavers. While the term habitus explains a disposition to speak positively about weaving, from a humanist position (Somekh and Lewin Citation2011, 324) it is also possible to reflect on the power, creativity and autonomy which such women represent. While there is a strength and capability demonstrated, it must be noted again that the Itneg weavers and their communities are mostly living in economic deprivation and climate change is affecting the Philippines to an increasing extent within the lowland delta where deforestation causes landslides which affect all aspects of community work and rice farming (Gabattiss Citation2018; Glover and Stone Citation2018). The concerns of the Sabangan community of weavers from their own words, are their low income, the loss of their heritage, their inaccessibility to local weaving cotton and the effects of rising sea levels their exposure to environmental changes.

The challenges of the Cordillera have been identified to align with the UN sustainable development agenda 2030 (United Nations Citation2020) and the Philippines is also included in the Development Assistance Committee list for the Office for Development Assistance (OECD 2020). Theories of Change (NESTA Citation2011) have been developed by the Crafting Futures projects to support action of change to enable craft communities who are at risk of their practices and culture disappearing but who are also working in precarious circumstances. Theories of Change bring together pragmatism with epistemology (Biesta Citation2010, 96) and the research process starts with final aims, then works back from that point to the point of entry. Theories of Change are helpful for the concrete thinking (Dalsgaard Citation2014, 1) which short term funded international projects require, but there is a contrast with interpretative research approaches. For practitioner researchers specifically to address the research questions which involve the problems which DAC list communities are facing as global challenges, there is an embedded complexity to the task.

Data and Discourse

American feminist anthropologist Margery Wolf describes in A Thrice Told Tale (Citation1992) thus: “The anthropologist listens to as many voices as she can and then chooses among them when she passes their opinions on to members of another culture. The choice is not arbitrary but then neither is the testimony… ” Wolf (Citation1992, 11). There is a wealth of Cordilleran weaving history held within global museum collections, in literature from nineteenth century anthropological studies and there are testimonies of this culture being celebrated and valued by research projects today. But what benefits have the communities ever gained from this? In ethnographic research, as in textile community practice and teaching, it seems that often more is learnt more about yourself than the context of the subjects/participants you are working with. So when working directly with weavers and their communities, auto-ethnographic methods are helpful for the researcher to understand their position in relation to research participants. If presented honestly in addition to the weaving information gathered, the qualitative data collected also included: Phone calls and text messages to families and children; bitten finger nails; incorrect clothing; lack of money; nausea, sleeplessness, worry, heat and fear. The difference between a researcher’s self-reflection is that through the economies of research, such reflections become experiential capital. But for the participants more often than not, nothing changes as a result.

Reflection on Photograph- Leaving our homestay at 2am to travel to Abra. (Image Rachel Kelly) this image illustrates the reality of our visit which meant that we (Kelly & Stephens) had much less sleep than we would normally survive on. The lack of sleep, dangers of travelling at night and tiredness on arrival to visit the communities provided an ‘edge’ from which to reflect. Our instincts were both sharpened and impaired during the project, making the experience deeply memorable. Every aspect of what we did, how we travelled enabled us to connect to the project, this place of weaving in the land of the Cordillera in the Philippines ().

Looking back at notes taken at the time, it was in the experience of this project where insights emerged which enabled the research questions to be addressed. A great part of understanding from this project came from an emerging textile identity (habitus) which comes from practice, but which places women textile workers in liminality within structures which prohibit development or growth. Similar to a teaching tutorial, when it is often difficult to capture fully at the time the reflection-in action moment (Schön Citation1987), praxis becomes an outcome of action through face-to-face conversations, sharing materials, stories and through solidarity. Within the Crafting Futures project, such situations or events would not be happening, had the project not taken place. Situated experiences play an important role when they become recognizable and identified by others (Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Koro-Ljungberg, MacLure, and Ulmer Citation2018, 809 in Denzin and Lincoln Citation2018). Interactions as research opportunities, serve a purpose beyond a project’s boundaries specifically when they are translated as fuel for education praxis. First-time practitioner-researchers who are engaging in projects such as Crafting Futures can be described as being susceptible to absorb the research experience as fully as they can (Shreeve, Citation2011), so within this first-time international research experience, everything stuck, was remembered and was documented. It is through a retrospective carding process that the richness of the experience can be evaluated and tested through discourse analysis methods. The rawness of the researcher then becomes a form of potential research in itself and this potential is perhaps what Rodgers (Citation2019b, 1) claims as “the necessary” within Design research today ().

Figure 8 Pinilian Horse Pattern: Learning tool-kit ‘new’ woven sample created by Dr Michelle Stephens. Photo Credit: Stephens, M. (2019).

Discourse analysis methods enabled the research questions to be explored through reflective interpretation of the data (Lee in Lee and Poynton Citation2000, 188 and in Somekh and Lewin, Citation2011, 140). The data available for analysis within the Crafting Futures project varied from semi-structured interview notes and workshop reflections, but it was the documentary photographs taken by the project photographer which became essential documents of the research as discourse. In analyzing the photographs taken on return from the Philippines, the memories of the weaving workshops in the Cordillera got mixed with recollections and images from personal working experiences. Images can become entangled through reflective practice and layered like a palimpsest where past memories becomes visible within a present image or surface (Ingold Citation2020). Weaver Catalina Abalog’s garden became a recurring memory or palimpsest where the experience at the time, which was representative of a paradise, was contrasting with questions around the circumstances of the weaver. The home of the weaver embodied an idea of perfection, if perfection is to be a woman doing work she feels proud of and working with independence, agency and autonomy: “To work in your own home, with your hands on your own loom, making textiles which affirm your sense of self at a deep level…and to have a small garden in which from dry ground is emerging some healthy looking pak choi” (From the author’s reflective project notes).

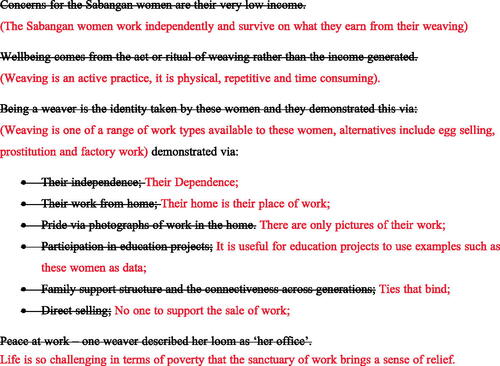

The CSTFW project used ethnographic methodology as a research process which can be guided by “uncertainty and contradictions…open-endedness and the open mind” Frankham and Edwards-Kerr (Citation2009) in Somekh and Lewin (Citation2011, 34). It also involved reflections on the research which involved data collected, but to be reflected on afterwards. Within a context where a white European researcher is traveling to the opposite side of the globe, the questions we ask and methods we use can become more important than the answers we seek (Wolf (Citation1992, 5). A discourse analysis method which uses a text reversal process (Threadgold in Lee and Poynton Citation2000, 48) enabled alternative or different facing perspectives like a warp and weft to emerge:

(The Sabangan women work independently and survive on what they earn from their weaving)

(Weaving is an active practice, it is physical, repetitive and time consuming).

(Weaving is one of a range of work types available to these women, alternatives include egg selling, prostitution and factory work) demonstrated via:

Their Dependence;

Their home is their place of work;

There are only pictures of their work;

It is useful for education projects to use examples such as these women as data;

Ties that bind;

No one to support the sale of work;

Life is so challenging in terms of poverty that the sanctuary of work brings a sense of relief.

Bourdieu’s theory of practice helps to clarify further, the opposing dispositions which this project presented:

(Bourdieu Citation1977, 101 in Thatcher et al. 2015, 8–10).

Habitus describes the role of textile practice and the identity of women textile workers who draw strength from their independence and autonomy. The weft of the project involves the capital of the participant, be it economic, social or intangibly cultural. The floating supplementary weft threads which are a characteristic of Cordilleran weaving can be visualized as the field and context of Crafting Futures as a concern which connects the Itneg weavers to a global community of craft practice. The resulting outcome is the capacity for a community of shared understanding to emerge as textile practice, which within such a globally disconnected context may seem strange to describe as also feeling at times, inseparable and connected.

Conclusion

The practical and supportive outcomes of the CSTFW project provided twenty-two small portable looms which aimed to recreate the portability of the traditional Cordillera backstrap loom. The backstrap loom is a sustainable alternative to be considered by the Itneg community who have for various aforementioned reasons, broken down or reallocated their frame looms and are to a certain extent, needing to learn again. A weave learning tool-kit in the form of a booklet which includes weaving drafts, drafting information and drafted textile study samples was provided as a practical outcome of the CSTFW project. The University of the Philippines Baguio team will use the weaving drafts developed to generate Itneg weaving patterns using a digital loom. In the future and it is hoped that master weavers, younger community members and students from the University of the Philippines will be able to work together in a new form of tradition, to produce digital reproductions of their patterns and develop new, yet culturally intangible weaving traditions.

The grip which Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice provides is vital to reflect on if marginalized women workers are to challenge and seek improvements in their livelihoods. Itneg practices will remain unsustainable unless economic outcomes or values of master craft practices are heightened through the shared knowledge and the craft activism which programmes such as Crafting Futures create. It is through respectful useful collaborations with outsiders, and in preservation of traditional intellectual property rights where, this work can commence in earnest. Within textile practice and education, there is often a tolerance in, rather than a construction of the structures in which we are held. The manner in which the weavers in the Cordillera tolerate aspects of their situations may seem to over simplify things (Stronach and Maclure Citation1997, 5; Atkinson 2003), but their tolerance gives power those who will continue until their breaking point occurs:

The critical point is that both sides of the coin of global cultural process today are products of the infinitely varied mutual contest of sameness and difference on a stage characterized by radical disjunctures between different sorts of global flows and the uncertain landscapes created in and through these disjunctures. (Appadurai Citation1990, 308)

Local, community and ground level craft praxis is required to balance out western orientated research paradigms and the colonial baggage we bring. The Mi’kmaw concept of Two-Eyed seeing is a term attributed to Elder Albert Marshall (Peltier Citation2018) and is a term which serves to synthesize indigenous methodology with western research methods. While a Two-Eyed seeing approach may enable community centered knowledges to be brought into focus, it is likely that Two Eyed seeing ‘will be congruent with decolonizing approaches to research and founded in Indigenous knowledges, methodologies, and ways of knowing (Kovach, 2009 in Wright et al. Citation2019, 16). Projects such as Crafting Futures paired with an openness to reflective auto-ethnographic methodologies enable a layering and palimpsest which comprises of experiences across different textile contexts to be created. Such textile envisions are vital to describe and discuss through research dissemination if we are to address some of the wider questions this article raises. The reflexive textile practitioner-educator within opportunities such as Crafting Futures projects can make the jump from the project context to their UK Higher Education teaching practice, to create awareness and stimulate change. However, it is with regret that like Margery Wolf I am also left asking myself: “Am I appropriating the collective experience of people [from Peihoten] for my own purposes, for my personal career needs? Yes, I suppose this is true” Wolf (Citation1992, 123).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rachel Kelly

Rachel Kelly is a senior lecturer on the Textile Programmes at Manchester School of Art and gained an MA in Design for Textile Futures from Central St Martins College of Art and Design, London in 2001. Rachel is currently studying for a Doctor of Education at ESRI/MMU. Rachel undertook a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning from 2016 to 2017 the result of which was the development of practice-based models for interdisciplinary collaborative pedagogy. Rachel has been recognized internationally and has exhibited within ground breaking design exhibitions such as Nobel Textiles The I.C.A London in 2009; Design for The Elastic Mind at MOMA New York in 2010. Since 2017, Rachel has been part of two British Council Crafting Futures Research Projects which continue to stimulate Rachel's keen research interest in collaboration; sustainability; textile practice education; digitisation and creative practice identity. Rachel will be a co-host of the Textiles and Place conference https://www.textileandplace.co.uk/ [email protected]

Notes

1 For an example of scientific and mathematical studies of Andean weaving traditions see: [online] [https://www.bbk.ac.uk/downloads/research/ref-impact-case-study-modern-languages-and-linguistics-andean-textiles-and-recovering-traditional-crafts.pdf]

References

- Acabado, S., and M. Martin. (2020). “Saving Ifugao Weaving in the Philippines.” Accessed 13 June 2021. https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/ifugao-weaving/]

- Albers, A. 1941. “Handweaving Today: Textile Work at Black Mountain College.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://albersfoundation.org/teaching/anni-albers/texts/

- Appadurai, A. 1990. “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy.” Theory Culture Society 7 (2–3): 295–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/026327690007002017.

- Aquino, M. U. 2005. “Dynamics of Weaving and Development of an Itneg Community in Abra, Philippines.” https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=PH2006000431

- Asian Development Bank. 2002. The Indigenous Peoples/Ethnic Minorities and Poverty Reduction: Philippines. Manila, Philippines: Environment and Social Safeguard Division, Regional and Sustainable Development Dept., Asian Development Bank. 971-561-442-6

- Biesta, G. 2010. “Pragmatism and the Philosophical Foundations of Mixed Methods Research.” In SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research, 95–118. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506335193.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. “Structures and the Habitus.” In R. Nice (Trans.), Outline of a Theory of Practice (Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology, 72–95. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812507.004.

- Bourdieu, P. 2010. Distinction. London and New York: Routledge.

- British Council. 2021. “Crafting Futures.” Accessed 22 May 2021 https://design.britishcouncil.org/projects/crafting-futures/

- Cole, F. C. 1922. The Tinguian Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe: Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe (Vol. 14, No. 2). Prabhat Prakashan. Accessed 31 July 2021. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12545/12545-h/12545-h.htm

- CORDITEX 2018. Executive Summary. Baguio City, Philippines: University of Philippines.

- CORDITEX 2019. Anthropological Analysis; Mathematical Symmetry and Technical Characterisation of Cordillera Textiles. Baguio City, Philippines: University of the Philippines (UP) Baguio.

- Crosby, Alexandra. 2019. “Design Activism in an Indonesian Village.” Design Issues 35 (3): 50–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/desi_a_00549.

- Dalsgaard, P. 2014. “Pragmatism and Design Thinking.” International Journal of Design 8 (1): 143–155.

- Damian, V. 2019. “Cordillera Facing Heirloom Rice Production Shortage.” The Philippine Daily Inquirer. Accessed 22 May 2021. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1193453/cordillera-facing-heirloom-rice-production-shortage

- De las Penas, M., and A. V. Salvador-Amores. 2016. “Mathematical and Anthropological Analysis of Northern Luzon Funeral Textile.” https://archium.ateneo.edu/mathematics-faculty-pubs/1/

- Denzin, N. K. and Y. S. Lincoln, eds. 2018. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Eggan, F. 1956. “Ritual Myths among the Tinguian.” The Journal of American Folklore 69 (274): 331–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/536339.

- Frankham, J., and D. Edwards-Kerr. 2009. “Long Story: Beyond 'Technologies' of Knowing in Case-Study Work with Permanently Excluded Young People.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 13 (4): 409–422. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802242108.

- Gabattiss, J. 2018. “Rice Farming Up to Twice as Bad for Climate Change as Previously Thought, Study Reveals.” https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/rice-farming-climate-change-global-warming-india-nitrous-oxide-methane-a8531401.html

- Glover, D., and G. D. Stone. 2018. “Heirloom Rice in Ifugao: An ‘Anti-Commodity’ in the Process of Commodification.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (4): 776–804. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1284062.

- Grenfell, M. 2012. Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Gutierrez, P. J. M. 2018. “HABI Moves to Reintroduce Cotton to Indigenous Weavers.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://businessmirror.com.ph/2018/10/10/habi-moves-to-reintroduce-cotton-to-indigenous-weavers/

- Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2020. “Provocation 2 Presentation at Manchester School of Architecture.” Accessed 12 February 2020. https://www.msa.ac.uk/media/msaacuk/documents/events/2020/provocation2.pdf

- Johnson, K. F., and T. Yushan. 2012. “A Weaver Loos at Tinguian blankets. Textile Society of America Symposium 2012.” Accessed 22 April 2021. [https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1062&context=tsanews

- Kelly, R., and M. Stephens. 2019. “The Digitization of Cordillera Weaving: Designing a New Oral Tradition.” IASDR 2019 Paper Presentation. Accessed 22 May 2021. https://iasdr2019.org/uploads/files/Proceedings/vo-f-1273-Kel-R.pdf

- Kelly, R., A. Kettle, and M. Stephens. 2019. Creating a Sustainable Textile Future for Women. Evaluation Report. London: British Council.

- Koro-Ljungberg, M., M. MacLure, J. Ulmer. 2018. “D… a… t… a…, Data++, Data, and Some Problematics.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 5th ed, 462–484, N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning. Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

- Lee, A., and C. Poynton. 2000. Culture & Text. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Marx, K., 1967 [1867]. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Vintage.

- Maslow, A. 1943. https://www.learning-theories.com/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs.html

- NESTA. 2011. Theory of Change. Accessed 19 February 2019. http://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/daclist.htm

- Orr, S., and A. Shreeve. 2018. Art and Design Pedagogy in Higher Education. London: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315415130.

- Peach, A. 2013. “What Goes around Comes around? Craft Revival, the 1970s and Today.” Craft Research 4 (2): 161–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/crre.4.2.161_1.

- Peltier, C. 2018. “An Application of Two-Eyed Seeing: Indigenous Research Methods with Participatory Action Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17 (1): 160940691881234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918812346.

- Rodgers, P. 2019a. “Design Research for Change.” Accessed 05 March 2021. https://www.designresearchforchange.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/DR4C-FINALBOOK.pdf

- Rodgers, P. 2019b. Interview: Professor Paul Rodgers. https://ahrc.ukri.org/research/readwatchlisten/features/interview-professor-paul-rodgers/

- Satterthwaite, J., E. Atkinson, and K. Gale. 2003. Discourse, Power and Resistance: Challenging the Rhetoric of Contemporary Education. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books Ltd.

- Schön, D. A. 1987. “Jossey-Bass Higher Education Series.” Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Shreeve, A. 2011. “Being in Two Camps: conflicting Experiences for Practice-Based Academics, Studies in Continuing Education.” Studies in Continuing Education 33 (1): 79–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2011.521681.

- Singson, M. 2014. “Indigenous Women Struggle Against Development Aggression.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://apwld.org/indigenous-women-struggle-against-development-aggression/

- Smith, L. T. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London; New York; Dunedin, New Zealand; New York: Zed Books; University of Otago Press; Distributed in the USA exclusively by St. Martin's Press

- Somekh, B. and Lewin, C. eds.,2011.Theory and Methods in Social Research. Sage.

- Stronach, I., and M. Maclure. 1997. Education Research Undone: The Post-Modern Embrace. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Tedlock, B., and D. Tedlock. 1985. “Text and Textile: Language and Technology in the Arts of the Quiché Maya.” Journal of Anthropological Research 41 (2): 121–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/jar.41.2.3630412.

- Threadgold, T. 2000. “Poststructuralism and Discourse Analysis.” In Culture and Text, edited by A. Lee and C. Poynton. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield.

- UNESCO. 2012. “Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras.” Accessed 24 August 2016. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/722/

- United Nations. 2020. Sustainable Development Goals. Accessed 1 October 2020. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf

- Wolf, M. 1992. A Thrice Told Tale: Feminism, Postmodernism & Ethnographic Responsibility. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Wright, A. L., C. Gabel, M. Ballantyne, S. M. Jack, and O. Wahoush. 2019. “Using Two-Eyed Seeing in Research with Indigenous People: An Integrative Review.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18: 160940691986969. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919869695.