Abstract

Taking the concept of intersemiotic translation as its point of departure, this introduction to the special issue presents an overview of the various ways in which translation, cloth and textile intersect, as well as a brief outline of how the articles included here address these intersections. An inter-semiotic translation is that in which a verbal sign is interpreted into a non-verbal system of symbols, in this case cloth and textile. Indeed, cloth and textile are at the heart of some of the most interesting and productive conceptualisations of translation, and semioticians have also proposed that cloth and textile can be understood as languages that are always-already in translation. Moreover, tailoring and painting, where clothes and textiles feature largely, have been used as rich and fruitful metaphors for the act of translating. In addition, interpreters have sometimes adapted their dress, that is, translated it, to be able to better perform their roles, while fashion and haute couture designers have also been cast as cultural interpreters. The articles that comprise this special issue consider all these dimensions and more, dealing with topics that range from science and technology, to art, literature and illustration; fashion and consumption; and political activism in a broad range of geographical contexts including Europe, Asia and Latin America.

Background

Translation is one of the most vital forces available for introducing new ways of thinking and inducing significant cultural change. Already in 1959 Roman Jakobson proposed a typology of translation that divided it into intralingual (as rewording within one language), inter-lingual (between languages) and inter-semiotic, that is, interpretation between different sign systems, “as when a piece of music interprets a poem” (Pym Citation2010, 150), and Umberto Eco also included translatory movements between semiotic systems in his theories (Eco Citation2001). In a similar vein, in his volume on translation, the French philosopher Michel Serres considered how different sciences translate concepts from each other, how paintings can translate physics—in particular, persuasively arguing that Turner’s paintings translated thermodynamics—and how literature translated religion, interpreting Faulkner’s work as a translation of the Bible (Serres Citation1974). The key issue is that translation, instead of being regarded as a finished product in the form of a text, is considered a process of communication between domains otherwise thought to be separate. In a chapter significantly entitled “How newness enters the world,” Homi Bhabha famously drew from this insight to study communication processes between cultural groups, drawing attention to the intermediary position of the translator, the cultural hybridity inherent to that position, and the problematic nature of the cultural borders crossed by translators (Bhabha Citation1994/2004). This became known as cultural translation, and the potential of translation to innovate was highlighted. However despite this considerable potential, and despite flourishing in other fields, inter-semiotic and cultural translations in relation to cloth or textile have been rare. Although translation in this sense can mean the conversion of something from one form or medium into another, and therefore we could speak of cloth or textile as translations of, for instance, image into fabric, or even science and technology into wearables (see de la Garza in this volume), the term is rarely used in this way. Indeed, in their introduction to the Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, Mona Baker and Gabriela Saldanha observe that:

One of the most fascinating things about exploring the history of translation is that it reveals how narrow and restrictive we have been in defining our object of study […] when we read about how African interpreters regularly translate African drum language into actual words, for instance, we begin to realise the current literature on translation has hardly started to scratch the surface of this multi-faceted and all-pervasive phenomenon […] I know of no research that looks specifically at the phenomena of intralingual or inter-semiotic translation. We do have classifications such as Jakobson’s, which alert us to the possibility of such things as inter-semiotic and intralingual translation, but we do not make any genuine use of such classifications in our research. (Saldanha & Baker, Citation2019, xx)

Contributing to address this gap, this special issue argues that the concept of translation, understood as a process of transformation, is a particularly useful one as an interdisciplinary interpretive framework and conceptual tool to address the various roles of cloth and textile in society and culture, and in particular as it circulates across media, cultures and societies. In fact, cloth and textile are at the heart of some of the most interesting and productive conceptualisations of translation, and semioticians have also proposed that cloth and textile can be understood as languages-in-translation. Tailoring and painting, where clothes and textiles feature largely, have been used as rich and fruitful metaphors for the act of translating. Moreover, interpreters have sometimes adapted their dress, that is, translated it, to be able to better perform their roles, while fashion and haute couture designers have also been understood as cultural interpreters. This introduction provides a brief overview of this potentially very fertile background of intersections, and also of how the articles that comprise this special issue engage with them here.

Cloth and Textile: Always Already in Translation

As the words “text” and “texture” share a common lineage, stemming from the Latin “textere” which means to weave, it is perhaps no surprise that literary translators have at times conceptualized their work in terms of textiles. Literary theorist Gayatri Chakravorti Spivak has used the image of the text as textile, suggesting that in the act of translating “we feel the selvedges of the language-textile give way, fray into frayages or facilitations” (Spivak Citation2000 [1993], 398). Indian feminist writer C.S. Lakshmi employs a textile image similar to Spivak’s, casting translation as an unraveling of the fabric, through an act of appropriation (Bassnett Citation2014b, 68). Conceptualisations of translation in the East have also relied on textile as a powerful metaphor. In China the term for translation itself, 翻译, fanyi, means the turning over of a brocade, showing the pattern on the reverse side to be different. But contrary to the use of the same metaphor in western texts such as Cervantes’ Don Quixote, where the underside of an embroidered Flemish tapestry is used to prove the irreconcilable difference between the original and the translation, in Chinese and Japanese the importance of difference is acknowledged (Guldin Citation2016, 44). In this volume, Shen Zheng employs this metaphor to present her comparative research on fashion microblogs in Ireland and China, which she translated into English and Chinese respectively over a three year period, with a bilingual digital text-mining tool also designed by her, in order to compare the strategies followed by the bloggers. This allowed for the identification of types and categories that were useful in both languages. The blogs themselves are, Shen contends, akin to a piece of brocade, in that they turn out to be, in various ways, versions of each other in a different language. The article thus provides empirical and visual evidence on the use of translation as a research approach to understand fashion blogging and the values there expressed, across cultures. Her work also contributes to research on how we read websites for translation, where the verbal content is just one element in a semiotic system that also includes visual images, frequently of textiles.

And if translators have conceived of their work as consisting of deep engagement with text as textile, semioticians have described actual textiles as text, in fact as a kind of language that is, as it were, always already in translation. Roland Barthes’ work on semiotics famously conceived of the entire “fashion system” as resting on the possibility to translate garments into a language comprised by the captions, titles and texts in fashion magazines (Barthes Citation1990 [1967]). Fashion brand names have also been theorized as signs whose function is mainly being in constant translation. The brand is “the cipher of a style that establishes an immediate chain between the garment and the language. We say, for instance, ‘I am wearing a Gucci’, when we mean ‘a knitwear set designed and produced by Gucci’” (Calefato Citation2021, 127). The given name of the brand condenses ample portions of meaning as it also is taken to express an imaginary life philosophy, thereby “translating” all this information from the wearer to others. On this account, fashion, instead of mainly dealing with the clothing of the body per se, deals with its inscription within a systemic space of signs. The article by Zhuang Su and Siyang Song in this volume considers the brand name and logo of Kenzo, a designer famous for the hybrid nature of his many cultural translations in dress, namely the famous tiger icon. Through the analysis of different forms of visual text structures throughout the whole process of fashion communication, the article explores the semiotic transformation process and strategy of the tiger icon by means of theories of visual rhetoric. The focus of the article is on the many ways the tiger is translated, as it transforms historically and as it moves from the actual garments to architectural features of the shops and also in its role as the organizing element of advertising campaigns. In a similar manner, Yu Chen claims in her discussion of costume in the film “Lost in Translation” by Sofia Coppola in this volume that this film employs “costume as a fluent visual language that effectively communicates the character’s identities and their relationship, but also as a means to indicate their transformation as they are displaced, and their evolving relation to the cultural setting where they are located, translating in this sense” (Chen Citation2021). She also highlights the importance of costume to research in both translation and film studies when she notes that: “Speaking of the relationship between film and translation, theorist Michael Cronin has said ‘part of the excitement of research in this domain is that so much remains to be done in terms of uncovering the representation of translation in world cinema’ (Citation2009). As Sofia Coppolas’s work shows, closely reading costume will be central to this research” (2021).

Embroidery too has often been characterized as a kind of language that is always-already in translation. In his volume on the misnamed Bayeaux tapestry (), where Arthur Wright contends the depictions on the margins alluding to fables and proverbs provide a kind of running commentary to the depictions on the main panels, he observes that the embroidered representations are signs and, as such, they form a language of their own. “Not one with an alphabet of precisely spelled orthography, demanding an accompanying lexicon, but a truly every day, practical or demotic set of signatures, an informal system or shorthand” (Wright Citation2019, 6). Because of this, Wright proposes to think of the Bayeaux as a “strip with separate commentaries, in fact commentaries in two languages [Latin and embroidery] and one of them at least [embroidery] for all tongues,” implying it is always already in translation. De la Garza, Hernández and Rosar explore this topic at length here, arguing that “the same stitches are used by embroiderers all over the world, providing a sort of international vocabulary that crosses the boundaries of countries and epochs and can be understood by many” (Citation2021). They further argue that this quality of embroidery makes it ideal for political activism as it puts a message across very effectively, and they provide many examples of embroidered work in Latin America in which women have been translating anger and frustration as well as hope into remarkable pieces that range from accessories used as props—such as the “green tide” of handkerchiefs in Chile and Argentina—to public art, as the collective street embroidery that takes place in Mexico. Importantly, beyond the translation of feeling into material objects, embroidery has also helped to disseminate their stories of resistance as framed by their translations, so that they can reach a broader variety of audiences, beyond their communities of origin. In Wright’s terms, they also feature commentary in two languages, Spanish and embroidery, the latter aiming to be “for all tongues.”

The Translator as Tailor/Dressmaker

Among the metaphors employed to understand the act of translating is that of tailoring: the translation as clothing put on the body of the original content, to make the (naked) meaning presentable to a specific society, dressed in appropriate garb for a new situation (Van Wyke Citation2011). As put by Nicholas Perrot referring to his translation of Assyrian writer Lucian into French:

I do not always bind myself either to the words or to the reasoning of this author, and I adjust things to our manner and style with his goal in mind. Different times demand different reasoning as well as different words. And ambassadors [i.e., texts] are accustomed […] to dressing themselves according to the fashion of the country where they are sent’ (quoted in Van Wyke, p. 25).

Translation theorist Lawrence Venuti developed an influential theory on two types of translating strategies, namely domestication and foreignization, that is also particularly apt for illustration with metaphors from the realm of dress (Venuti 1995 [2008]). In brief, domestication involves an ethnocentric reduction of the foreign text to the target language’s cultural values, “leaving the reader in peace and moving the author toward the reader.” Whereas foreignization aims for the translation to register the linguistic and cultural difference of the foreign text, “sending the reader abroad” (Venuti 1995 [2008], 20). Venuti thus advocated estranging the translation style so as to make the foreign identity of the source text evident as the ethical, non-imperialist choice. The translation should not seem to be transparent, but on the contrary, come across as translated text. While the quotation above by Perrot advocated domestication, German translator Von Herder argues instead for foreignization in these terms:

The French, too proud of their national taste, assimilate everything to it rather than accommodating themselves to the taste of another time. Homer must enter France a captive, clad in French fashion […] must let them shave off his venerable beard and strip off his simple attire […] We poor Germans on the other hand, lacking as we do […] a tyranny of national taste, just want to see him as he is (Von Herder Citation2002, 208).

While Denham, translator of Virgil, wrote “as speech is the apparel of our thoughts, so are there certain garbs and modes of speaking which vary with the times, the fashion of our clothes being not more subject to alteration than that of our speech’ (Van Wyke, p. 23). Interestingly, Lakoff and Johnson, who argued that conceptual metaphors are based on bodily experience, also employed a clothing metaphor to convey the way language and thought are both separate and intertwined, describing language as ‘the dress wrapped around thoughts” (Guldin Citation2016, 15). Henry Rider, the 17th century English translator of Horace, also used this translator-as-tailor image, involving the remodeling of old garments and arguing that translations of authors from one language to another are like re-purposed old garments, turned into new fashions “in which though the stuffe still be the same, yet the die and trimming are altered, and in the making, here something added, there something cut away” (Rider quoted in Venuti, Citation1995: 49–50). Translation as tailoring is seen here as a means of preserving outdated clothing, that is, of transforming what is considered to be good to ensure its longevity (Bassnett Citation2014b, 84). Walter Benjamin too, in his seminal essay “The Task of the Translator,” wrote “the language of the translation envelopes its content like a royal robe with ample folds” (Citation2000, 79).

In this volume, de la Garza considers tailoring and dressmaking as a material, rather than textual, translation of scientific ideas and concepts. Drawing from feminist translation theories and strategies, she presents the work of women textile artists whose dress installations have featured in science museums and galleries as translation—rather than as illustration or facilitation. The very choice of dress as the end product of the translation makes the feminine visible, opening the seemingly “hard” world of science to a wider audience by using the “softer” medium of textile: although gender boundaries are now far more fluid than they were even fifty years ago, “the dress has remained a garment that typifies femininity in all its guises” (Edwards Citation2017, 14). Among the works discussed is Primitive Streak, a collection of 26 dresses and a hat by Helen and Kate Storey that explain nine key events that take place during the first 1,000 hours of the life of the embryo, from fertilization to the appearance of recognizable human form; Femme Vitale, a flamboyantly patterned pharmaceutical frock by Susie Freeman and Liz Lee made of 27,774 pills and capsules of eleven different drugs that were prescribed to a woman suffering from metabolic syndrome over ten years, also forcefully conveying, in its design, the nature of the syndrome; and the “making” approach to teaching STEM through and with the arts and humanities (STEAM) that introduces concepts from mathematics and physics through the textile crafts, focused on the kinetic: crocheting hyperbolic planes into scarves and cowls, or sewing circuits, among other works discussed.

The fact that women feature frequently in both fields, translation and clothes/textiles, and the gender implications of this are also taken up by Petra Leutner in her article here, on how the ideas and principles of the Bauhaus design school in Germany (1919–1933) were translated into textile and cloth. At the center of Bauhaus esthetics, Leutner claims, were functionalism, abstraction and the realization of the “Gesamtkunstwerk” (total work of art). The Bauhaus esthetic thus decisively shaped the development of art and design in the 20th century. Her article discusses the many difficulties encountered in the attempt to translate this esthetic to textiles and fashion. It shows the institutional problems that arose, since a rejection of female creativity prevailed within the Bauhaus school, so that female students had to work primarily in weaving. The examples of Gunta Stölzl and Anni Albers are used to explain how the female artists finally managed to successfully translate the Bauhaus style into textile works. This piece also traces how fashion designers in the 21st century, on the occasion of the Bauhaus anniversary in 2019, referred to the art school and how two-dimensional patterns of weaving were translated into fashion collections.

The Translator as Painter—and Designer

Another common image for the translator has been that of a portrait painter, the sitter standing for the source text and the painting for the translation. Dryden uses the metaphor to argue for fidelity, saying that the painter has the duty of making his portrait resemble the original. Tytler uses it too, but to argue that although the translator cannot use the same colors as the original, he is nevertheless required to give his picture “the same force and effect” (Bassnett Citation2014a, 72). And as Anne Hollander has argued, “clothing appears in all traditions of figurative painting, often filling two thirds of the frame without seeming to be there” (Hollander Citation2016, 8). Hollander adds that the force of the Mona Lisa lies “to a not inconsiderable degree in the thin veil darkly silhouetted alongside her falling hair, the one-sided wrap of her mantle, the many regular and subdued folds descending from the narrow band at her neckline. Different decisions about the details of the veil, dress and scarf would have produced different effects in the smile” (Hollander Citation2016, 8). This shows not only to what extent the “copy,” that is the translation, can have a much longer and prolific afterlife than the “original” or source text, and the agency of the translator, but also the extent to which the ability to depict clothes and fabric—soft furnishings, tapestries, embroidery—was implied in the translator-as-painter image.

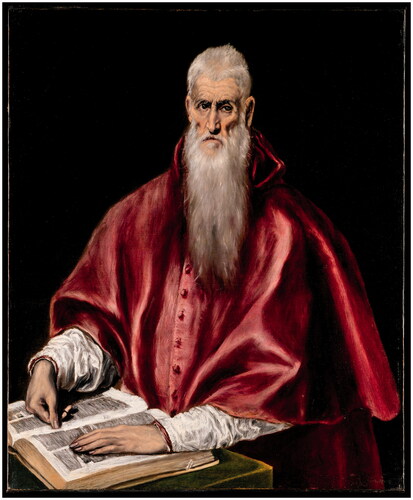

More relevant for illustrating how the translator-as-painter is relevant to cloth and textile in our case is the example of the various paintings of Saint Jerome (c. 342–420), best known as a translator of the Bible, which depict him at work, and in one of the genres also elegantly dressed in his Cardinal vestments. The paintings by El Greco (1609) and Francisco de Zurbarán stand out for the way they render the fabrics. There are at least five paintings of Saint Jerome by El Greco. On the version shown here () the deep folds in the garments are striking, as well as the shine of the silk and the contrast between the deep red and the white. El Greco is said to have applied “his distinctive mode of expression to all the fabric in his pictures, giving cloth not only new scope for pictorial action but new ways of resembling phenomena other than cloth” (Hollander Citation2016, 50–52). Zurbarán on the other hand, celebrated for his exquisitely rendered draperies and haunting colors of the fabrics (Bowles Citation2011, 35), also painted St Jerome several times, but he usually made woolen fabric hang around the figure in stiff folds, in contrast to the light silk El Greco painted. For his Jerome in the Desert, Tormented by his Memories of Dancing Girls also known as “The Temptation of Saint Jerome” (1639) () however, it is the women’s attire that take up most of the canvas. Both these paintings—and presumably others by the same and other Spanish painters from El Prado museum—in turn acted as the “source text” that Spanish designer Cristóbal Balenciaga translated into actual dress. The woman’s ensemble he designed in 1963 in silk plain waive (see image of Women’s Ensemble by Cristóbal Balenciaga, 1963 on the LACMA website at https://collections.lacma.org/node/201073), today part of the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, features the colors of El Greco’s St Jerome, and the cape seems to be inspired on the Saint’s mozzetta. But the heavy drapery recalls Zurbarán’s work. Balenciaga’s talent for fusing traditional religious dress as depicted on these paintings with modern lines and dramatic silhouettes made his work stand out as innovative and sophisticated textile translations. The idea that designers were artists is “a mid-nineteenth century French invention which enabled the dress designer to be deemed an original genius, much like the painter” (Neal Citation2019, 122). Painter, translator and designer are thus shown to largely share, through metaphor, a rich semantic field.

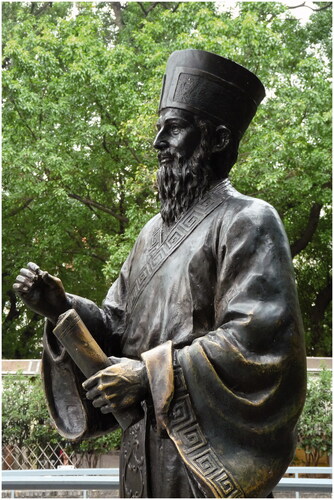

Figure 4 Matteo Ricci with his 'translated' dress (attribution: creative license AwOiSoAk KaOsIoWa).

This is a topic that Germán Gil-Curiel discusses in relation to Irish artist Harry Clarke, whom he claims translated the works of Edgar Allan Poe he analyses here, from word into image, while enriching the source text by adding to it highly original and detailed costumes for the main characters, and also textiles more generally. Although Clarke is mostly famous for his stained glass and book illustration, he also designed fabric for dresses, and two sets of handkerchiefs for Sefton fabrics. The article is based on Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay “The Task of the Translator,” where Benjamin claims that translations ought to be regarded as the after-life of a source text, stating that the idea of life and afterlife in works of art should be regarded “with entirely unmetaphorical objectivity” for “a translation comes later than the original and […] their translation marks their stage of continued life.” This seems particularly suitable for the horror tales by Poe that focus on death and life after death that are the subject of this article. In his guise as visual artist/translator and also designer, Clarke contributed to the afterlife of the tales “Ligeia” and “Morella” (Poe Citation1919 and Citation1923 [1839]), partly by completing, as it were, the canvas, or in other words, enriching the source language, with his exquisitely rendered costumes.

Beyond painting, the costume and fashion designers and textile artists who have engaged with literary, visual or digital works for the creation of their outfits and pieces play a crucial role in the translation of the cultural values expressed in the garments they bring from novels, poems, songs, paintings or films into their fashion creations, often across cultures. Equally, they have played a role dressing the foreign for presentation, unleashing creativity into garments that are then available for consumers’ self-construction and expression. From Alexander McQueen’s sustained engagement with films ranging from “One Flew Over a Cukoo’s Nest” to “The Birds” or Givenchy and Jean Paul Gaultier’s “Appearances can be Deceiving: the Frida Kahlo wardrobe” exhibition, based on their interpretations of the famous painter’s personal wardrobe with emphasis on the topics of disability, ethnicity and the post-human, costume and fashion designers can be understood as translating from the semiotic codes of the adapted works into the tangible materiality of textiles, enabling creativity as the languages of culture, art and fashion are crossed. It is to this topic of interpretation that we now turn.

Translation, Interpretation and Dress

Translating, Lynne Schwartz argues, “may feel like writing, it is a form of writing, but in fact the act it resembles most is acting” (Schwartz Citation2017, 10). Indeed, translation is a performance, all about doing. The dress they wear has had considerable impact on the work of some translators, and was itself bound to the process of translating. Take for instance Matteo Ricci (6 October 1552 − 11 May 1610), an Italian Jesuit priest and a founder of the missions to China, who translated the Confucian classics into Latin for the first time, and also, with the help of Xu Guangqi, Euclid’s Elements into Chinese, among other seminal work in cartography, history and literature. He was also the first European to enter the Forbidden City in Beijing in 1601, invited by the Emperor, and successfully converted several prominent Chinese officials to Catholicism. It is said of him that he was able to make connections at the highest levels because he presented himself as a “sort of ‘Western Christian in Chinese skin’,” that “skin” regarding mainly his appearance, specially clothes and garments in general (Ambrogio Citation2014, 152). In a letter dated 4 November 1595 Ricci described his attire thus:

I have acquired a silk robe for solemn visits […] made of ruby silk with long and large open sleeves; around the low hem there is a half span trimming of very bright turquoise silk, and the same trimming runs around armholes and collar up to the belt. The belt is made of the same fabric as the robe, and from it many pendants flutter down to the ground, similar to the belt of our widows […] the headdress has similarities with our bishop’s one […] to wear that silk robe makes me seem very authoritative (quoted in (Ambrogio Citation2014, 153).

A statue of Ricci wearing the clothes he describes on the letter is shown on image 4 here (). Dressed in them, he appeared as a Chinese literati among the literati. While there was some controversy on Ricci’s taking up this rich attire instead of the plain monastic western dress he ought to have worn, the success of his mission inspired others to do the same. His decision involved far more than a simple changing of garments of course, as it signaled a deeper and more complex adaptation to the society where he was working. He basically had to translate his clothes in order that his other translation work be effective. Or as put by Dario Tessicini: “The 17th century Jesuit Matteo Ricci’s decision to dress as a Confucian scholar while on his mission in China was meant to ‘translate his social position into Chinese’” (Tessicini Citation2014, 2). Other translators in Asia who worked for European colonizer or settler groups are also sometimes quoted as having to dress in particular ways for their interpretations, or performed translations, to be regarded as official. (See for instance Chan’s account of translators as negotiators for the Dutch in Formosa (Chan Citation2014)).

Figure 5 Carl Linnaeus wearing Lappish garments. Author: Bj.schoenmakers, painter: Juul Smulders (attribution: creative license).

In a different context, that of science, the case of Carl Linnaeus is also worth mentioning. Linnaeus laid the foundations for systematizing botany by formalizing the binomial nomenclature, that is, the system of naming organisms employed today, thereby significantly contributing to advance communication among botanists in the world, providing a common language. Prior to his work there were competing names for plants invented by different botanists. He also significantly advanced botany by studying the uses of plants among the indigenous Sami culture of Lapland. After his return from his trips to Lapland, he became well known for wearing Lappish garments to demonstrate for his students the ways in which the Sami engaged with plants for a variety of botanical purposes, or in other words, translate to them “the ways of the Sami people” (Balick and Cox Citation2021, 14). His portrait at the botanical garden in Delft, the Netherlands, depicts him wearing these garments (). From Venuti’s perspective above, it can be said that while Ricci “domesticated” his attire in translation, Linnaeus “foreignized” it.

Dress in translation is the topic that Eugenia Paulicelli deals with in her article in this volume. Her article employs the notion of cultural translation as an interpretive lens and mode of interrogation to analyze a case study in fashion, that of Gucci and its relationship with the Harlem-based designer Daniel Day, known as Dapper Dan. The article draws from the work of Homi Bhabha and the concept of cultural translation he developed in his 1994 book The Location of Culture mentioned above, in which he approaches translation as a process, a discursive practice and ultimately a political strategy that in turn could be a form of activism (Bhabha Citation1994/2004). Rather than migrants being transformed by cultural translation, Bhabha specifically refers to the possibility for migrants themselves to transform receiving cultures—exactly what Ricci aspired to do—and so produce what he called a “third space,” or, in Roland Barthes’ terms, a third meaning and alternative culture. This article illustrates how a minoritarian group or culture resists assimilation into white hegemonic culture, producing an alternative hybrid language in the domains of fashion and style. The article contextualizes this critical discourse in what bell hooks, among others, has identified as a commodification of otherness that is often masked by a recurrent discourse on cultural diversity (hooks Citation1992/2015, 21–40). However in the case examined the designs by Dapper Dan eventually led to his collaboration with Gucci, thus illustrating the shifts in power inherent in the construction and maintenance of the “third space.”

From a different perspective, Lin Pang employs the metaphor of terroir to argue that

Belgian fashion designers are able to translate the national, regional and local identity of the country into their sartorial work, in a similar manner as the French wine-makers transform terroir with regard to specific national and regional wines (Pang Citation2021).

Conclusion

To summarize, this special issue puts forward a highly original take on the subject of cloth and textile in translation. It explores the connections between textile, dress and translation from various different perspectives: from articles that employ theories of translation as their theoretical framework, inter-semiotic translation, and cultural translation, to articles that discuss linguistic translation using digital tools, including data mining and visualizations. The topics addressed are also wide-ranging: from science and technology, to art, literature and illustration; fashion and consumption; and political activism. Moreover, the articles also consider a broad variety of contexts, with cases drawn from Europe, Latin America and Asia, and include some established and well known voices in the field, as well as early career scholars and practitioners. It is, in sum, ambitious, broad in scope, innovative and it will hopefully be inspiring. We expect that it will stimulate further research on textiles, cloth and culture from the perspective of translation, that is, as transformation and becoming.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Armida de la Garza

Armida de la Garza* is Senior Lecturer in Digital Arts and Humanities at University College Cork Ireland. She is interested in collaborative, interdisciplinary research that bridges the gap between science and the arts. Her recent research projects include internationalizing the curriculum for STEAM and working with students as partners in virtual international mobilities. She started her academic career as a translator. [email protected]

Wang Jie

Wang Jie is Qiushi Distinguished Professor at the College of Media and International Culture in Zhejiang University China and Distinguished Professor of the Ministry of Education of the Yangtze River Scholars. His main research interests include esthetics, esthetic anthropology and contemporary Chinese esthetics. [email protected]

References

- Ambrogio, Selusi. 2014. “The Jesuit Dilemma in Asia: Being a Naked Acetic or a Court Literate?” In Global Textile Encounters, by Marie-Louise Nosch, Feng Zhao and Lotika Varadarajan, 151–158. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Balick, Michael J., and Paul Alan Cox. 2021. Plants, People and Culture: The Science of Ethnobotany. Abingdon: CRC Press.

- Barthes, Roland. 1990 [1967]. The Fashion System. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Bassnett, Susan. 2014a. Translation Studies. London: Routledge.

- Bassnett, Susan. 2014b. Translation: The New Critical Idiom. London: Routledge.

- Benjamin, Walter. 2000. “The Task of the Translator.” In The Translation Studies Reader, by Lawrence Venuti. London: Routledge.

- Bhabha, Homi. 1994/2004. The Location of Culture. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bowles, Hamish. 2011. Balenciaga and Spain. New York: Rizzoli.

- Calefato, Patrizia. 2021. Fashion as Cultural Translation: Signs, Images, Narratives. London: Anthem Press.

- Chan, Pin-Ling. 2014. “The Political and Diplomatic Significance of Interpreters/Translators in 17th Century Colonial Taiwan.” In Translations, Interpreters and Cultural Negotiators: Mediating and Communicating Power from the Middle Ages to the Modern Era, by Federico M. Federici and Dario Tessicini, 136–154. London: Palgrave.

- Chen, Yu. 2021. “A Costume Analysis of the film ‘Lost in Translation’ (Coppola 2003).” Textile, Cloth and Culture 20 (2): 231–236.

- Cronin, Michael. 2009. Translation Goes to the Movies. Abingdon: Routledge.

- De la Garza, Armida, Claudia Hernández-Espinosa, and Rosana Rosar. 2021. “Embroidery as Activist Translation in Latin America.” Textile, Cloth and Culture 20 (2): 168–181.

- Eco, Umberto. 2001. Experiences in Translation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Edwards, Lydia. 2017. How to Read a Dress. London: Bloomsbury.

- Guldin, Rainer. 2016. Translation as Metaphor. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hollander, Anne. 2016. Fabric of Vision: Dress and Drapery in Painting. London: Bloomsbury.

- hooks, bell. 1992/2015. Black Looks: Race and Representation. London: Routledge.

- Neal, Lynn S. 2019. Religion in Vogue: Christianity and Fashion in America. New York: New York University Press.

- Pang, Ching Lin. 2021. “Terroir in a Dress. Understanding Antwerp-Style Fashion.” Textile, Cloth and Culture 20 (2): 237–240.

- Poe, Edgar Allan. 1919 and 1923 [1839]. Tales of Mystery and Imagination. London: Harrap.

- Pym, Anthony. 2010. Exploring Translation Theories. London: Routledge.

- Saldanha, Gabriela, and Mona Baker. 2019. Introduction. In Routledge Encycopledia of Translation Studies by M. Baker & G. Saldanha, third Edition, xv–xxiv. London: Routledge.

- Schwartz, Lynne Sharon. 2017. Crossing Borders: Stories and Essays about Translation. London and New York: Seven Stories Press.

- Serres, Michel. 1974. La Traduction. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorti. 2000 [1993]. “The Politics of Translation.” In The Translation Studies Reader, by Lawrence Venuti, 397–416. London and New York: Routledge.

- Tessicini, Dario 2014. “Introduction: Translators, Interpreters and Cultural Negotiators.” In Translators, Interpreters, and Cultural Negotiators: Mediating and Communicating Power from the Middle Ages to the Modern Era, by Federico M. Federici and Dario Tessicini, 1–9. London: Palgrave.

- Van Wyke, Ben 2011. “Imitating Bodies and Clothes: Refashioning the Western Conception of Translation.” In Thinking through Translation with Metaphors, by James St Andre, 17–46. Manchester: St Jerome Publishing.

- Venuti, Lawrence. 1995 [2008]. The Translator's Invisibility: A History of Translation. London: Routledge.

- Von Herder, Johann Gottfried. 2002. “The IDeal Translator as Morning Star.” In Western Translation Theory: From Herodotus to Nietzsche, by Douglas Robinson, 207–208. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Wright, Arthur C. 2019. Decoding the Bayeux Tapestry: The Secrets of History's Most Famous Embroidery Hidden in Plain Sight. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books Ltd.