Abstract

The identification of clothing is one of a range of tools used by forensic anthropologists to aid the identification of the dead. Clothing and shoes directly and indirectly represent both people’s bodies and their identities. Where means allow, individuals will usually choose what to wear each day, as part of their social or cultural identity. These are conscious decisions that are an important aspect that defines them and will inform how they are perceived by others.

After the death of a loved one, clothes are often kept, and act as an enduring presence. Clothes and shoes are vessels or containers, becoming reliquaries that remind us of their owners. Shoes particularly embody the idea of transience or movement from one place to another, from one city to another, perhaps from life to afterlife and from existence to no longer existing.

Within my research I am considering unidentified deaths. What happens to individuals who cannot be identified? And what does it mean to a society if human remains cannot be named?

As an artist my approach to these questions is through creative practice, questioning the space between life and death and acknowledging that transition. Can a previous existence be acknowledged in a way that demonstrates care, without simply reporting a death or adding to statistics? Working in bioplastic I have created a body of work that directly references these questions.

In this paper I will discuss my creative practice approach to the theme of acknowledgement of unidentified dead. This practice aims to raise questions about how it is possible to consider, and remember the lives lived by unidentified human remains.

Identity

My current research is borne out of a previous project that explored unidentified dead within mass graves, focusing primarily on the Former Yugoslavia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. With this work I explored the importance that fabric had in helping to prove genocide at Srebrenica. During the Hague trials, forensic scientists showed that that the same fabric had been used as ligatures and blindfolds and could be seen across numerous grave sites therefore proving a level of coordinated planning in advance of the events that took place (.

“Lie Down” is made from torn strips of cloth tied as if for the purpose of blindfolding or tying hands. I dyed the lower section with coffee grounds as a symbol of societal breakdown—coffee is an important aspect of community in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Shortly after the war in Bosnia, Interpol stated that it is “the right of human beings not to lose their identity after death,” (RESOLUTION No. AGN/65/RES/13 − 1996) however this statement led me to question the right to identity of those individuals who cannot be scientifically “identified.”

In 2019 I spent a year working for Crisis as an Outreach Arts Facilitator with rough sleepers. During this time, I began to consider unidentified deaths closer to home. Homeless services often know the names of clients that approach them for help, but many others remain unseen, unnoticed people, operating completely outside of societal structures. Initial research took me to the missing persons database, a public site that lists the details of each unidentified body in the UK. At the time of writing there are 566 unidentified people listed on this site. Some are relatively recent but others date back as far as the mid 1960s. Each individual is listed with a generalized location, description and potential identifying features and/or belongings, with images included if available. These items and details are often incredibly poignant but not necessarily complete enough to enable identification. However, the belongings do often show a small picture of the end of that life and a glimpse of that person.

For example, one entry is as follows:

Black “Karrimor” rucksack,

umbrella,

map of Winchester,

black male pants,

white t-shirt,

“Marina Cole” novel “The Close” (2006),

4/5 white flannels,

2 packets of polos,

Germolene, KitKat and various other wrappers,

garden trowel,

gloves,

flask,

torch,

old Walkman-style radio,

sleeping bag,

tobacco and Rizla papers,

Zantac.

There is agency within this list. 2 packets of polos and a KitKat are treats, not food, and imply a future in which these will be consumed. The map too could imply a destination, or perhaps it was somewhere this (male) individual had been? A sense of character may be deduced from a choice of book, but perhaps this was a gift. The context makes these items also take on a sense of the funereal, grave goods perhaps for a journey into the afterlife. (“Case 17-008997” 2017)

Through my research I question whether these people were really alone in the world? Perhaps this is a life (and/or death) they chose, or did circumstance dictate this final outcome? Some are suicides, others are presumed to be homeless, some have simply fallen ill suddenly without identifying items on their person.

Unidentified human remains have no one available to consider their final wishes. Without identity their wish to be remembered cannot be known nor can their preferences on how their remains should be handled. Without a formal identity, relatives and friends who may be looking for them cannot be informed. Therefore, these individuals go unnoticed, unacknowledged, and therefore forgotten. There is no opportunity for the enactment of the rites of passage associated with the loss of a human life.

In such a situation questions over the rights of the dead and whether acknowledgement matters, should be considered? Of course, it is important to understand what has happened, especially in cases where there may have been any criminal activity, but does acknowledgement matter to the body? Perhaps communities need to acknowledge these deaths as resulting from societal failures in, for example mental health services or housing, or from family breakdown. It is these communities that are relied on in death to identify each of these individuals.

Is it only important to be able to name a body? After the Guatemalan genocide in 1960 anthropologist Victoria Sanford noted that families looking for loved ones within the carefully laid out belongings would say “Si no tiene dueño, entonces es mio [If it has no owner, then it’s mine]” (Sanford Citation2003) unable to find anything within the clothes and belongings that they recognized, they felt such strength within their communal bonds that they were prepared to accept another body as their own relative. This communal acknowledgement of each body makes sure that each individual is mourned and not forgotten.

When considering identity in this context, most people assume that science can step in, but DNA is only useful if there is something to cross reference a sample to. Fingerprints are only useful if they are already recorded on a database. Documents can identify someone but only if carried about their person. What is crucial to identity is the people who knew the individual, the community, a friend or relative who can acknowledge the passing and step forward to identify the individual. Clothing can often be the first step in the identification process for surviving relatives.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina clothing was recorded alongside each of the human remains, often washed, and laid out for relatives to view. A forensic book of belongings was produced showing photographs of the items of clothing and belongings and this was taken and shown to living relatives.

Adam Rosenblatt argues that the forensic process itself is a form of care. He suggests that “Various aspects of forensic work are irreducibly tactile: exhuming the grave; lifting out, sorting and assembling individual bodies; matching them with their clothing and other personal objects; and extracting the samples that are used for DNA analysis, for example.” (Rosenblatt Citation2015).

This sense of care and acknowledgement of the unidentified dead is what I am exploring within my work; some proof of a previous existence, that goes beyond analytical data that is presented in an environment that, although public, keeps the information away from the majority. I am interested in the impression of continued and/or residual presence within environments, a haunting perhaps but not in the traditional (supernatural) sense. When referencing her book “Ghostly Matters” in an interview, Avery Gordon stated that “haunting is a way we’re notified that what’s been suppressed or concealed is very much alive and present.” (Gordon, Hite, and Jara Citation2020) The unseen/unnoticed deaths that I am examining haunt the present, urging the acknowledgement of their passing.

The missing persons database lists the site of each person’s death, not in a detailed, specific way but rather in more generalized varied locations, from train stations to remote woodland. I am interested in asking whether these sites hold any form of residual presence, what this might be, how this presence is manifest and how one might go about representing this?

The first rule of forensic science states that “every contact leaves a trace” explained here within Forensic Botany. Principles and Applications to Criminal Casework

“Crime scene investigation is based on the principles of transfer theory, in particular, Locard’s Exchange Principle. Locard’s Exchange Principle states that any time two or more surfaces come in contact with each other, there is a mutual exchange of trace matter between the two surfaces. A common generalization from this principle is “every contact leaves a trace.” This concept is critical for considering how evidentiary samples can be utilized to link a suspect to a victim, a victim to a crime scene, or a suspect to a scene.”(Gomez-Beloz Citation2006)

By conceptually exploring the unintended final resting spaces of the unidentified dead, I am looking for liminal presence, a space between life and death and acknowledging that transition “Death itself, as a stage, is inherently unstable and liminal.” The transition from life to death, that is, to die, is for the person concerned no doubt a watershed event. Yet, from the perspective of the survivors, it presents itself also as a change in phase of existence, since for them there is a certain continuity between the qualities of a person who is alive and those that characterize him or her immediately after death.(Berger and Kroesen Citation2016)

Some of the remains listed on the database are discovered after bodies have been skeletonized and as explained here in an article about human decomposition, in The Guardian “A decomposing body significantly alters the chemistry of the soil beneath, causing changes that may persist for years. Purging releases nutrients into the underlying soil, and maggot migration transfers much of the energy from a body to the wider environment. Eventually, the whole process creates a ‘cadaver decomposition island,’ a highly concentrated area of organically rich soil. As well as releasing nutrients into the wider ecosystem, the cadaver also attracts other organic materials, such as dead insects and fecal matter from larger animals.” (Costandi Citation2015)

Through this idea of a “decomposition island,” I began to consider the surrounding plant material from sites where human remains have been found. Without preservation, human bodies become nutrients, feeding the soil and nourishing plants that often begin to flourish because of the raised nutrient levels. Plants here appear to be the “observers” of these deaths. Scientists are currently asking similar questions. A paper published in Trends in Plant Science October 2020 suggests that “…plants might assist forensic teams in the search of missing persons using remote sensing technology. With plants acting as environmental sentinels…”(Brabazon et al. Citation2020) Scientists have begun using drones to visualize changes in hyperspectral reflectance and autofluorescence within plant material over large areas as it is thought that “Vegetation that is currently considered as an obstacle to cadaver recovery has the potential to become a significant asset in the detection of human remains through UAV-based remote sensing.” (Brabazon et al. Citation2020)

The scientific discipline of forensic botany studies plant material at scenes of crime, usually to determine what has happened rather than who it has happened to, but plants (acting as observers) can often show botanists a snapshot of what has taken place. The conceptual absorption of decomposition continues indefinitely within plant material. As plants die back, they enrich the soil once more. Water too is an important aspect of this process. The human body is made up of more than 70% water. Water has always existed on earth in the same quantity, continually recirculating. Water has been a fundamental part of everyone who has ever existed, so in essence water is all the people who have existed before. Water and nutrients within the human body become part of the surrounding environment, the decomposition island. This circular process of renewal creates a physical continuation of presence within space.

Materiality

When considering the belongings left by unidentified human remains, the item that appears in almost every entry of the database is shoes. Shoes particularly embody the idea of transience or movement from one place to another, from one city to another, from life to afterlife, from existence to no longer existing. The saying “If the shoe fits” refers to something being the truth about someone, and of course Cinderella was identified as the owner of her shoe by a process of investigation that could be seen as similar to forensic work.

Artists have used shoes to symbolize “the missing” on a number of occasions, for example, artist Chiharu Shiota used shoes to explore “how familiar objects gain and lose meaning, and what an object says about its owner. The artist describes objects such as shoes as acting like a “second skin,” containing the imprint of a person.” (Kutner Citation2014) another example is the memorial on the banks of the Danube River in Budapest created by film director Can Togay together with the sculptor Gyula Pauer. “The shoes are so tangible that it is easy to imagine the people who wore them, whose feet shaped them, who were forced to take them off before they were killed. Each shoe has a personality; each has the imprint of the foot that wore it. The only thing missing is the owner. The shoes help us to conjure up something akin to the faces of the owners—those whose faces were obliterated—turning them from statistics into living, breathing human beings.” (Silver Ochayon)

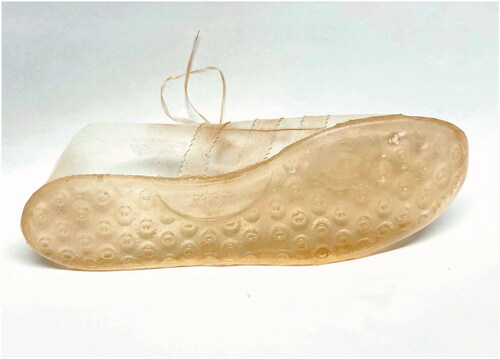

When deciding how to approach my ideas relating to the shoes of unidentified dead, bioplastics became an important material, allowing me to explore the ideas I had been researching. Gelatin is a biopolymer that is typically a waste product from the food industry. When combined with glycerin it produces a robust clear, sheet material. The gelatin I chose to use is pork gelatin because it is bodily, being made from pig collagen sourced from skin, bone, and connective tissue. It has a direct connection to forensics, as in the UK, pigs are used to train cadaver dogs, because aspects of their pathology closely resemble that of humans.

Gelatin Bioplastic is transparent and malleable, and easily made in a home kitchen. It has a ghostly quality, that can physically embody the ideas of something that is missing, barely there. Bioplastic is also ephemeral. As a biodegradable material, it slowly breaks down (just as bodies do) becoming part of its surroundings. It is also made predominantly of water, like humans (and all animal life forms). The process of evaporation can be seen to have ghostly qualities; moisture is held in the air that remains unseen. Bioplastic is made predominantly with water and the process of creation requires that evaporation takes place. References to the “unseen” act as a metaphor for the unseen in society, the lonely, the homeless or outsiders that many unidentified people inevitably were (.

With some experimentation I have developed a way of making clothes and shoes from gelatin bioplastic. These items directly and indirectly represent both people’s bodies and their identities. Where means allow, individuals will usually choose what to wear each day, as part of their social or cultural identity, and these conscious decisions define them and determine how they are perceived by others. Items of clothing are also used to help with the identification of an individual after death. They are listed within the entries on the missing persons database as a way of attempting to identify individuals. Clothes are often kept after the death of a loved one, “as a point of material contact with the body of a once living person. They thus provide a means by which memories of that living body can be generated.” (Hallam and Hockey Citation2001) Clothes and shoes are vessels or containers, acting as reliquaries that remind us who they belonged to.

“The artifacts exhumed from the graves have a social as well as a forensic life. First, they act as signifiers of the missing persons for family members, and then they become relics. Once exhumed, the artifacts that enter the forensic and legal processes exist as evidence of both the crimes and the persons. Once the evidentiary process has ended, however, these artifacts are returned to the families of the missing, where they still retain meaning. They provide a physical connection to and a testimony of the life and death of their missing family member. They become relics.” (Jugo Citation2017) ( and .

The Cinderella story is an interesting one too in relation to my research. A glass shoe would not display the individuality of the owner within its materiality and shoe size alone is also unlikely to identify an individual unless the size is either exceptionally large or small. Through history however extremely small female feet have been a sign of beauty “Our findings that small foot size relative to stature often increased female attractiveness while average foot size relative to stature was generally preferable for males are consistent with the hypothesis that humans possess an evolved preference for small female feet as one facet of the general preference for signs of youth and nulliparity in females.” (Fessler et al. 2005) However it is the glass reference within the Cinderella story and the barely visible bioplastic that is interesting here. The history of glass used for the slipper within the Cinderella story has been questioned and appears to stem from one version written in 1697 by Charles Perrault titled Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre (Cinderella, or the little glass slipper). However, there are questions about whether the author meant to write “verre” or “vair.” The word vair refers to a rare squirrel fur used in clothing by nobility in the Middle Ages. “Furthermore, this gazing at the shoe is a phantasm of the marital consummation of this love. As a phantasmic image, the pantoufle de verre/vair (fourrure) assumes the fetishistic quality of the foot which is described by Freud” (Murray Citation1976) This passage highlights a reference to a phantasmic image, whether that be because it is made of glass or is simply seen a premonition is unclear .

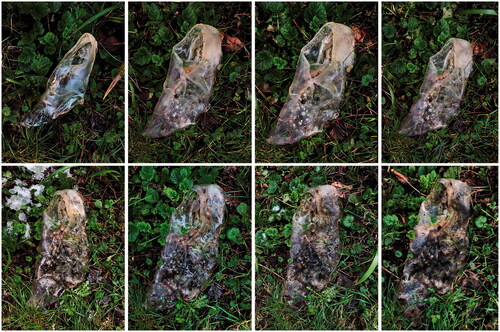

Using the thoughts and ideas outlined above I have produced an ongoing body of work that explores the acknowledgement of unidentified dead. Starting with the examination of entries on the missing persons database but also considering individuals that are potentially even more difficult to identify such as those found as a result of archaeological digs. The idea of remaining presence fuels this enquiry. Water and nitrogen are part of all living things but also part of the process of decomposition. They continue as cycles of renewal within the atmosphere as well as the soil. Gelatin bioplastic’s ephemeral qualities embody the process of life and death as well as it’s precariousness within the environment.

The potential invisibility and continued existence as a haunting presence is also captured using this clear material. By creating shoes with the bioplastic, I am directly referencing a familiar object that is listed with every missing person entry. Shoes are personal; they are worn everywhere and when old they become molded to the shape of the individual foot. They leave imprints where they have been, and these traces can also be used within forensics. This concept of “the trace” is referenced within the shoes that I have cast - see Bioplastic Wrangler Boot 2021. The extraction of the original shoe from the bioplastic “skin” leaves a residual trace of the leather surface, showing the individuality of each item. Creases and lines highlight a sense of lived experience and again this trace parallels aspects of forensic investigation such as fingerprint retrieval (.

The ability to gradually decompose is an important aspect here too. Directly evidencing the fragility of the dead body within the environment and returning it to the soil. By displaying the shoe in a gallery environment, the potential for decay is embedded within its materiality but as part of the development of this body of work I have also documented the shoes’ decay in other contexts, allowing me to visualize and consider decomposition as part of the work (process and outcome).

With my research I raise awareness of the existence of individuals who have died unnoticed, people who are currently only acknowledged as a reference on a database. With no one to mourn or remember them, these individuals will fade from society’s consciousness. By making reference to the belongings that unidentified individuals had with them at the point of their death, I directly connect to aspects of their individuality. This individuality within well-worn belongings is akin to identity in life as well as death. Belongings help individuals to convey how they are seen by others and when well-worn become recognizably theirs. In death belongings have an increased poignancy every mark seems to have a story to tell. To loved ones these are precious items kept safe to remember times spent together, but when items are discovered with unidentified human remains the individuality of items is perhaps all we have to suggest something of the individual’s identity. My use of bioplastic within my art practice embodies the precariousness of physical presence. My research and practice aim is to open conversations that will hopefully allow viewers to acknowledge the passing of individuals who have passed unknown.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katie Taylor

Katie Taylor is at The School of Arts, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, United Kingdom. She is a contemporary sculptural installation artist. Her work explores the interface between materiality and memory. [email protected]

References

- Agency, National Crime. 2017. Case 17-008997. National Crime Agency. https://missingpersons.police.uk/en-gb/case/17-008997#.

- Berger, Peter, and Justin Kroesen. 2016. Ultimate Ambiguities: Investigating Death and Liminality. New York: Berghahn Books.

- http://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=4089584

- Brabazon, Holly, Jennifer M. Debruyn, Scott C. Lenaghan, Fei Li, Amy Z. Mundorff, Dawnie W. Steadman, and C. Neal Stewart. 2020. “Plants to Remotely Detect Human Decomposition?” Trends in Plant Science 25 (10): 947–949. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2020.07.013.

- Costandi, Mo. 2015. “Life after Death: The Science of Human Decomposition.” The Guardian, October 20. https://www.theguardian.com/science/neurophilosophy/2015/may/05/life-after-death.

- Fessler, Daniel M. T., Daniel Nettle, Yalda Afshar, Pinheiro, Isadora de Andrade, Bolyanatz, Alexander, Mulder, Monique Borgerhoff, Mark Cravalho, Tiara Delgado, et al. 2005. “A Cross-Cultural Investigation of the Role of Foot Size in Physical Attractiveness.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 34 (3): 267–276. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-3115-9.

- Gomez-Beloz, Alfredo. 2006. “Forensic Botany. Principles and Applications to Criminal Casework.” Economic Botany 60 (2): 192–193. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2006)60.

- Gordon, Avery F., Katherine Hite, and Daniela Jara. 2020. “Haunting and Thinking from the Utopian Margins: Conversation with Avery Gordon.” Memory Studies 13 (3): 337–346. doi:10.1177/1750698020914017.

- Hallam, Elizabeth, and Jennifer Lorna Hockey. 2001. Death, Memory, and Material Culture. Oxford: Berg.

- Jugo, Admir. 2017. “Artefacts and Personal Effects from Mass Graves in Bosnia And Herzegovina. Symbols of Persons, Forensic Evidence or Public Relics?” Les Cahiers Irice N 19 (2): 21–40. doi:10.3917/lcsi.019.0021. https://www.cairn.info/revue-les-cahiers-sirice-2017-2-page-21.htm.

- Kutner, Max. 2014. “What’s In a Shoe? Japanese Artist Chiharu Shiota Investigates.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/whats-shoe-japanese-artist-chiharu-shiota-investigates-180952458/.

- Murray, Timothy C. 1976. “A Marvelous Guide to Anamorphosis: Cendrillon ou La Petite Pantoufle de Verre.” MLN 91 (6): 1276. doi:10.2307/2907137.

- RESOLUTION No. AGN/65/RES/13 – 1996. edited by Interpol.

- Rosenblatt, Adam. 2015. Digging for the Disappeared: forensic Science after Atrocity. Stanford Studies in Human Rights. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Sanford, Victoria. 2003. Buried Secrets: Truth and Human Rights in Guatemala. 1 ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Silver Ochayon, Sheryl. “The Shoes on the Danube Promenade – Commemoration of the Tragedy.” Yad Vashem –The World Holocaust Remembrance Center. https://www.yadvashem.org/articles/general/shoes-on-the-danube-promenade.html.