Abstract

Styles of knitwear associated with places, such as Shetland’s “fair isle” and Ireland’s “aran” knitting, are viewed through the lens of “tradition” by many consumers and makers. The creative process which results in such textile products is widely recognized as a communal one and set within centuries-long (real and imagined) historical contexts. This popular understanding includes a valorization of hand skills, particularly the improvizational fluency of expert hand knitters of the past. Their remembered ability to work and re-work inherited forms into innovative objects with minimal or no written instruction is an example of the “improvizational dynamics” which make “copying and reproduction…part and parcel of the creative process”. During the twentieth century, Shetland “fair isle” and Irish “aran” knitting experienced commercial success fueled by both hand and machine making practices, part of their industrial heritage which influences production today. With the increasing globalization of the mass market apparel industry, “fair isle” and “aran” knitwear styles have been absorbed into an international design lexicon that is drawn on by a wide range of producers. Contemporary commercial producers of knitwear in Shetland and Ireland distinguish themselves from their international mass market counterparts by emphasizing their enmeshment in a living, longstanding, communal creative web of hand and machine-making practices. This article explores the relationship between creativity and repetition in contemporary Shetland “fair isle” and Irish “aran” knitting, drawing on interviews and observations from two studies, one about “skill” in the knit industry of Shetland and Ireland funded by the Carnegie Trust (2018–19) and one about the value of Shetland hand knitting (2016–17). The article argues that repetition (including that enabled by “traditional” hand knitting patterns and the designs programmed into automated production systems) and the mutually disruptive interplay of hand and machine processes are key to creativity in place-based knitting practices.

Introduction

This article considers “creativity” in knit production in two geographical areas: Shetland (an island archipelago off the north coast of Scotland) and in Ireland (specifically counties Donegal and Galway). Shetland and Ireland each boast distinct varieties of knitwear, each named after islands: as well as Shetland lace knitting, Shetland is home to “fair isle” stranded colourwork, named after the island called Fair Isle, while Ireland is home to “aran” knitting, a heavily textured cabled style named after the Aran Islands.Footnote1 Within the situated networks of people, place and material that produce place-based knitting in Shetland and Ireland, designers and makers navigate both (1) creative industries policy and practice which focuses on individualized creative innovation and (2) heritage discourse which attributes distinctiveness to places and origins rather than people and innovation. While both these approaches are often used tactically and skillfully in order to make knit production and related activity viable, the creativity that animates such place-based communities of practice is more accurately described in terms of the “improvizational dynamics” which make “copying and reproduction…part and parcel of the creative process” (Svašek Citation2016, 2; see also Hallam and Ingold Citation2007). The kaleidoscopic reimagining of a long-evolving and growing “shared repertoire” (Wenger Citation1998, 16) is a process which springs to life in the moments forms pass between, for example, hand and machine, photograph and chart, or people.

This article draws on primary material from two research projects: a project about “skill” in the knit industry of Shetland and Ireland funded by the Carnegie Trust, which included interviews with key individuals in Shetland and Ireland in 2018–19 and visits to sites such as factories, studios, shops and tourism venues during the same period; and a 2016–17 study of Shetland hand knitting, undertaken in partnership with a voluntary group called ShetlandPeerieMakkers (Carden Citation2018a). Shetland and Ireland are included in comparative perspective to highlight how the particularities of places with distinct knitting “traditions” exist within international cultures of craft and global systems of manufacturing.

The parallels between fair isle and aran knitting go beyond being named after northern European islands. These kinds of knitwear have shared periods of commercial popularity since the early 20th century, have both become symbolic of aspects of national identity, and are both a focus of fascination for contemporary hand knitters while forming part of the design repertoire of international mass manufacture. The people who are at the center of this article—those who make knitwear in the places that are home to fair isle and aran knitting—navigate similar “landscapes of practice” (Wenger-Trayner et al. Citation2014). In both areas, subsets of already small populations perform a wide range of hand, machine, domestic, leisure and commercial making that is brought into interdependence by the close-knit nature of small communities and by contemporary understandings of knitting “tradition.”

Creativity and Place-Based Knitting

While places like Shetland and rural Ireland are frequently used as sources of creative inspiration for knitting products, from hand knitting patterns to fast fashion knitwear, contemporary knitting practitioners and commercial knitwear businesses in places with widely recognized knitting “traditions” have a complicated relationship to dominant discourses of creativity. First, they must navigate “urban and western-centric notions of creativity promoted in the creative economy” (Hawkins Citation2016, 9), which define creativity as individual innovation through concepts such as intellectual property (Garnham Citation2005; Frew Citation2011) and often overlook everyday creativity such as knitting (Platt Citation2019, 369). Second, rural and island places are viewed through a heritage lens which positions craft as communal creativity, with distinctiveness and invention attributed to places and their “traditions” rather than people (Turney Citation2009; Luckman Citation2012, 215; Carden Citation2018a, 45–49).

The notion of innovation established in mainstream creative economy discourse (that is, as a distinct and individually-attributable advance oriented toward economic growth) is challenged by those considering creativity from other perspectives. In the field of craft and design, for example, Twigger Holroyd et al. (Citation2015: 2) argue that innovation includes not only technological novelty but also “new ways of transmitting knowledge from one generation to the next” or restoring “a sense of place and meaning to our material culture” (Carden Citation2018a, 31). Anthropologists have problematized the relationship between innovation and creativity, arguing against “a limited understanding of creativity as pure innovation” (Svašek Citation2016, 2; see also Hallam and Ingold Citation2007, 10). Part of the impetus for this work in anthropology is recognizing the diverse forms of human creativity into which “The mantra of creativity and/as innovation spreads with neoliberal capitalism” Meyer (Citation2016, 315). Svašek (Citation2016, 2) asserts that “practices of copying and reproduction should not be placed in opposition to creativity, but conceptualized as part and parcel of it,” arguing for “improvization” as a model of creativity rather than “innovation.”

Place-based knitting is one realm where copying and reproduction can be seen as animating and generative, rather than necessarily a creative dead end. As vernacular craft and everyday creativity (Hawkins Citation2016, 9), hand knitting involves the circulation of algorithmic patterns for stitches and garments and the know-how to produce replicable products. As manufacturing, knitwear production involves the recreation of recognizable styles, including those which communicate a connection to pre-industrial hand knitting practice. What imbues contemporary knitting with “place-based” qualities—both specific visual and textural features associated with places, and enmeshment in localized process and practice—is generative repetition and copying, including transposition between different social contexts and between mutually disruptive hand and machine operations.

Place-Based Knitting in Shetland and Ireland

One of the things that makes places like Shetland and specific parts of Ireland creative wellsprings for knitting is the intimacy with which different modes of making meet in them. In rural and island places with small populations, the “creating” (Svašek Citation2016, 2) of knitting happens in different social contexts which are highly visible to each other and often intersect. This includes, to different degrees in different places: local industry, domestic vernacular craft, craft tourism, online leisure knitting communities and the international fashion trade. Some brief historical information on knitting in each of the locations of this study is necessary before we can consider how different kinds of knitting come into contact with each other there today.

The long history of Shetland’s knitwear industry is intertwined with that of the islands’ landscape and broader economy through crofting, fishing and trading (Abrams Citation2005, Laurenson Citation2013). In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the knitting trade included a “barter truck” system whereby knitters were paid in goods rather than money, making them vulnerable to exploitation by retailers and landowners (Abrams Citation2012, 603; Mann Citation2017, 98). Shetland became known for both its lace knitting and its fair isle colourwork (Chapman Citation2015, 197). The 20th century popularity of Shetland knitwear, particularly its fair isle designs, contributed to the Shetland knitwear industry remaining an important part of the islands’ economy and a significant employer until the late twentieth century, combining elements of home and factory, hand and machine production (Bennett Citation1981, 223; Fryer Citation1995). The arrival of the North Sea oil industry brought about swift changes in Shetland’s economy and social life in the 1970s and 1980s (Byron and McFarlane Citation1980; Byron Citation1986), including a boom in salaried work for women which, alongside other social change, reduced the role of knitting as a widespread economic activity (Fryer Citation1995, 178). This intensified the heritage gaze on Shetland knitting, with knitting singled out as one of the traditional industries eligible for support from Shetland’s newfound oil wealth.

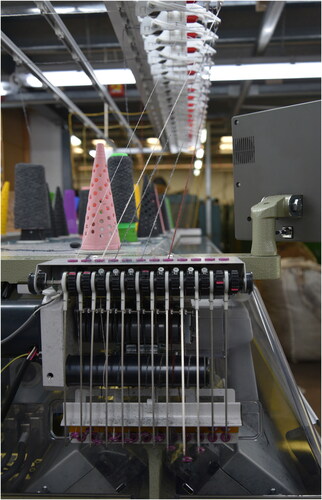

Today Shetland has two knitting factories using Shima Seiki machines (), as well as the University of the Highlands and Islands’ “Textile Facilitation Unit” (TFU), a mini-factory which produces knitwear for students and customers using the same kind of machinery (). A varied range of Shetland designer-makers do some or all elements of production in their own studios, using less elaborate equipment like flat-bed/v-bed knitting machines (sometimes called “hand frames”) and linking machines.Footnote2 The TFU’s customers include designer-makers who use the facility for short runs (that is, small quantities) of industrial production.

Figure 1 A Shima Seiki machine, Jamieson’s of Shetland. Photo by Susan Timmins as part of this study. Copyright the author. 2018.

Figure 2 A Shima Seiki machine in the Textile Facilitation Unit (TFU). Photo by Susan Timmins as part of this study. Copyright the author. 2018.

Commercial knit producers in contemporary Shetland participate in a “making culture” (Carr and Gibson Citation2016) that includes within its “ecology of skilled practice” (Mann Citation2017) the historically rooted and live practice of noncommercial knitting in Shetland, tourist activity within Shetland, and the enveloping discourse of a global leisure knitting community. Many of today’s domestic hand knitters in Shetland have personal or family experience of Shetland’s knitting industry, whether in factories or in widespread home piecework networks. Almost all local commercial knit producers are somehow involved in Shetland Wool Week, an annual craft tourism event, whether through studio visits, factory tours, workshops or sales at the festival. The existence of a global leisure knitting community not only provides a steady flow of craft tourists but a year-round, multi-layered online discourse that constructs Shetland as a source of knitting skill and inspiration (Carden Citation2019). This enmeshment of industry, vernacular craft, tourism and online activity provides a rich flow of inspiration and adaptation, replication and copying between them. In addition, fashion brands from Chanel and Alexander MacQueen to high street brand Oasis have created Shetland-inspired garments (BBC. Citation2015; Mower Citation2016; Shetland Museum and Archives Citation2017). Indeed, some expert Shetland knitters suggest that while younger generations may object to their own designs being directly copied without credit or permission, in the past they themselves fully expected fashion industry visitors on research trips to recreate what they saw.

In Ireland, commercial hand knitting also commonly took place on a piecework basis in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but knitting in Ireland was not as prominently or broadly embedded in a communal way of life and economy as it was during this period in Shetland. The enduring depopulation and deprivation of rural western parts of Ireland after the Great Famine of the 1840s prompted various government and charitable attempts to support rural economies, notably including the Congested Districts Board, which had a significant impact on areas like Donegal (Beattie Citation2013). Breathnach (Citation2004, 84) reports that the Congested Districts Board combatted the tendency for “knitted goods” to be paid for with barter and traded within networks of indebtedness, similar to the Shetland barter-truck system but characterized by the local wheeler-dealer figure known as the “gombeenman”: “gombeenman control also incorporated a bonded labor market, also termed the ‘truck system,’ where bartering or payment in kind was used to exchange goods for textile out-work.”

Aran knitting, a heavily cabled fabric which began to be promoted as a distinct place-based style in the early twentieth century, “was adopted and developed for an international craft and fashion market in the 1930s and 1940s” (Cléir Citation2011, 206) and was boosted in the mid-20th century by the economic and cultural influence of Irish-America. By the 1960s, when the aran jumper became particularly popular, the longstanding migration of Irish people to the USA was accompanied by a contrary flow of Irish-American tourism to Ireland. Aran knitting offered a ready symbol of connection and belonging that transcended its occasional moments as a fashion trend to become one of the standard visual short-hands for Irish identity.

Within Ireland, the continuing influence of aran knitting is visible at sites of knitwear production and retail. Certain places, particularly along the west coast, hold clusters of these sites. In southwest County Donegal, for example, there are commercial knitting factories in Kilcar, Glencolumbkille and Ardara, as well as hand knitting for sale (), a wool spinning mill, handweaving studios and a carpet weaving factory (Beattie Citation2013). Aran knitting is prominent in associated retail spaces as well as tourist sites. The Aran Islands themselves, in County Galway, are home to a high-end knitting factory and shop (), a separate tourist-focused retail space and individual makers for whom knitting provides one among several sources of income. In Galway city, a major tourism hub, a wide range of modes and sites of production can be traced through the aran-style knitwear available in city center shops, from mass-produced and imported jumpers to those labeled with names of individual local hand-knitters ().

Figure 4 Dresser full of handknit Aran knitwear by Kathleen Meehan, Donegal. Photo by the author. 2018.

While the history of aran knitting is intimately connected to tourism, and few international tourists in Ireland today escape contact with aran knitting in the form of souvenirs and marketing imagery, craft tourism that approaches knitting as a skilled activity for tourists to learn and take part in has been slow to develop in Ireland in comparison to Shetland. However, the growth in leisure knitting in the early 21st century, not least in North America, combined with the international reach of aran knitting as a symbol and the visibility of sheep in the Irish landscape, create an appetite for, and expectation of, a more participatory knitting experience amongst craft-enthusiast tourists. Small-scale, specialist knitting tourism ventures have recently been joined by one of Ireland’s mainstream tour companies which has added “Knitting Tours” to its selection (Irish Tourism Group Citation2022). In recognition of the commonalities between Ireland and Shetland for craft tourists, this Irish company has in recent years offered a knitting tour of Shetland.

Close contact between local industry, vernacular craft, craft tourism, online-mediated leisure knitting communities and globalized garment manufacturing in Shetland and Ireland provides many opportunities for cross-fertilization between these different modes of making. A Donegal hand-knitter reports once providing stitch pattern swatches to the founder of a company that markets mass-produced aran jumpers as corresponding to family names.Footnote3 Some businesses in Shetland and Ireland produce both commercial knitwear and yarn for hand knitting.Footnote4 Leisure knitting tourists at such as those at Shetland Wool Week visit factories and watch fleece being sorted by hand as a kind of spectator sport.Footnote5 Shetland knitwear designer-makers also teach classes of visiting tourists or online learners, showing family pictures along with knitting and design processes.Footnote6 In Ireland and Shetland, local knitwear companies and mass market brands take inspiration from old garments found in sheds or archives (Shetland Museum and Archives Citation2017).Footnote7 Hand knitters around the world reverse engineer, recreate and re-mix place-based garments encountered in person or refracted through media (such as Hollywood films: see Shaffer Citation2020).Footnote8 The “working reference materials” of past local industry in places such as Shetland are reproduced as inspiration for today’s leisure knitters (Christiansen Citation2016, 12).

The fair isle yoke jumper is one example of a design that has bridged different modes of making, in terms of social contexts and, as Abrams and Gardner (Citation2021, 171–172) highlight, hand and machine processes. This style of sweater combines a plain body and sleeves with a multicolored design on the yoke, most commonly some variation on a “star and tree” design incorporating the decreases between chest and neck. The fair isle yoke jumper was particularly fashionable in the 1960s, but remained a Shetland knit industry staple through succeeding decades and recurs in mass market fashion and in hand knitting; a designer with a long history in the Shetland knit industry wondered aloud in an interview “why has that come back?”Footnote9

The 1950s “arrival of the domestic knitting machine in many island homes” (Fryer Citation1995: 175) enabled a piecework system whereby plain bodies and sleeves would be made on domestic knitting machines, while the yokes were handknit, usually by different people.Footnote10 Interviewing volunteer hand knitting tutors in Shetland in 2017, those who had grown up with commercial knitting happening in their households often remembered the production of this kind of garment. Two interviewees remember their respective mothers doing different parts of this process:

It was really the bodies for whole jumpers, with plain Shetland jumper weight wool, so she would knit the body and she’d knit the ribbing and she would knit the cuff and the sleeve and then she would have to graft it, and have it all ready so I think it was then packaged up to somebody else, who then knitted on a yoke, hand knitted on a yoke.Footnote11

And then the fashion then came to yokes, and that was about the time when I was I suppose 3, 4, 5… she was getting to knit about 5 yokes a fortnight, roughly, and she would get the bodies and everything, somebody else had made them so she just did the yokes and grafted on the necks and the cuffs and things.Footnote12

This yoke-knitting mother and her daughter taught a class together at Shetland Wool Week in 2016 (see Carden Citation2018a: 35), where international craft tourists approached this stalwart design of the late twentieth-century Shetland knitting industry as a canvas for their individual creativity in color choice. The daughter continues to teach classes of recreational knitters and produce knitting patterns which build on family experience of commercial hand knitting. As a design like the fair isle yoke moves between industry and leisure making and travels around the world, different considerations of efficiency, materials and individual agency provide moments of improvizational creativity.

Those knitting quantities of items for sale in the 1960s-1990s had varying amounts of freedom in color combinations depending on their client. Shetland knitter Hazel Tindall, in public talks, has commented on the choice commercial knitters had in the 1960s, as opposed to later on when clients became more prescriptive: “When I started there was nobody telling me what colors I would use. I looked at the graph pattern and decided well I’ll have a few rows of this and a few rows of that and I ken I made some horrendous fair isle yokes, but they all got selt.”Footnote13 The ability to improvise with color was part of some commercial hand-knitters’ special expertise, as this interviewee recalls:

mum’s 78 now, she speaks about being praised for her colourwork…she did knit for a wee while to [for] X. During the 1990s some time she did a wee bit again for X and she did the lace gloves, she did some of them. But I think she found that too repetitive, because the colours were set.Footnote14

A Shetland woman who worked as a knitwear designer in the 1980s remembers the improvizational skill of those who knit for her: “they were amazing, they could just knit whatever. I’d give them a bag of color and a swatch…if I was ‘industry’ at that point, what were they knitting for their families?”Footnote15 She recalls a knitter asking permission to “knit one of hers” for their own purposes and says there “must have been a whole lot of knitters who picked up for businesses and had the skills” to adapt or copy those designs in their own noncommercial knitting.Footnote16

Of course, copying is not always welcome or ethical; for those trying to make a living or a name from their creativity in knitting, being able to accurately attribute credit and assert ownership is vital. Individuals working within place-based knitting practices often pay homage to the heritage, tradition or past generations of artisans that fuel and legitimize their own creative production, while formulating their own improvizations in ways that can be credited and faithfully reproduced. Two of these techniques of reproduction are patterns, for hand knitters, and programs, for industrial knitting software.

Patterns and Programs: Repetition and Automation

If copying between different social contexts and modes of making fuels creativity in place-based knitwear, patterns and programs are key pathways for this generative transposition. In hand knitting, patterns for stitch repeats and whole garments record making practices and carry instructions from person to person; in digitally automated knitting, such instructions are programmed into software for communication to machines as well as between people. The shared algorithmic properties of hand knitting patterns and computer coding are often remarked upon, including in studies of STEM education (e.g. Pöllänen and Pöllänen Citation2019, 20; Dodson-Snowden Citation2022).

When today’s knitters discuss earlier generations of Shetland knitting, an absence of written patterns is often mentioned. Arnold (Citation2010, 87) observes that “Shetland hand knitters over 60 years of age in 2003 seem to have been taught to knit by maternal osmosis or by imitating their female relatives…The Shetland process begs questions about how patterns developed and how new ideas were assimilated.” This kind of knitting could be viewed as more like an oral tradition than a written one (see Chapman Citation2015, 115 on similar dynamics in nineteenth century Shetland lace knitting). In the case of fair isle, “there was a visual passing on of design by copying actual knitted garments, and later graph paper and dots were used as visual memory aids” (Arnold Citation2010, 87). The Shetland Guild of Spinners, Dyers and Weavers have published “A Shetlander’s Fair Isle Graph Book” (2016), featuring designs drawn in colored pencil in notebooks once in the possession of the man “in charge of the Hosiery (Knitwear) Department at Anderson & CO [a local company] in the mid-20th century” (Christiansen Citation2016, 7). It is not clear how these particular notebooks were used, but the practice of using graph paper to draw or “dot out” sequences of color changes allows for the reproduction, tweaking and re-mixing of fair isle designs within different knitted items. The improvizational fluency of expert fair isle knitters is reminiscent of Svašek’s (Citation2016, 6) discussion of improvization in jazz music:

Like musical fragments that are reproduced and expanded in succeeding performances, visual fragments and stylistic features are also recycled, reconfigured and recombined—in new times, places and infrastructures…

An expert Shetland fair isle knitter in her 60 s remembered knitting classes in school where color patterns were copied and adapted into garments:

half the class would dot out patterns in the graph book, so she only had about six of us at a time and the following week you swapped…It was probably copying patterns more from traditional graph books and we chose the ones we wanted to dot out and we also probably also chose the ones we wanted to knit into the garments we were going to knit.Footnote17

Indicating a similar improvisatory process, an expert aran knitter in Donegal (a rare contemporary professional hand knitter), reports being asked “how many patterns did I know…I said sure I know hundreds of them? You mix them up, you don’t make any two the same, which I don’t usually…”Footnote18

Knitting patterns, both for stitch repeats and whole garments, circulate through instructional literature in the form of books, pamphlets and magazines which have shaped perceptions of the knitting of Shetland and Ireland far beyond their shores (for example, see Chapman Citation2015 on “Shetland” lace in nineteenth century pattern books). “Island” knitting instruction books comprise a subgenre of their own, whether those focusing on one island or those that reference an assortment of islands, creating a vision of Britain and Ireland as a literally and geopolitically wooly archipelago (e.g. Thompson Citation1971; Starmore and Matheson Citation1983; Pearson Citation[1984] 2015; Dawson Citation1998; Breitenfeldt, McEndoo and Bail O’Keeffe Citation2015).

Most of these books are not written by people who live in the places referenced, but patterns for knitted garments are also part of the mixture of products sold by knitwear designers, knitting teachers and yarn producers in Shetland and Ireland. As an Irish knitwear designer who champions aran knitting tweeted: “Pattern design must be part of a product mix & sometimes a loss leader to build community…Designers may teach, sell kits, video or garments.”Footnote19 A Shetland designer (Carden Citation2018a, 28) with a diverse range of professional knitting-related practices, from teaching to dyeing yarn, describes the attraction of pattern design:

it almost came about by accident in some ways, but now it’s really, it is mainly what I do and I can see there’s such a big market for it. And it’s kind of a way of making money without having to produce something and sell it. You’re doing the design work and then you can sell the patterns and you’re not having to do work to constantly produce things which is kind of outwearing.Footnote20

The internet has enabled garment patterns to be produced and shared by individuals with minimal gatekeeping. Simultaneously, the millennial surge in online knitting publications and communities (Humphreys Citation2009: Orton-Johnson Citation2013: Pierce Citation2014) has created new markets for instructional literature and new opportunities for people steeped in place-based knitting to represent their own creative skill.

Carr and Gibson (Citation2016, 307) observe that in the contemporary world, “the ability to work with materials in skilled ways is under threat from automation, deskilling and labor precarity.” The history of textile-making holds important examples of the interrelationship of automation, skill and labor, including the role of mechanized spinning and weaving technology in catalyzing the First Industrial Revolution, and the Luddite workers’ protests which became emblematic of resistance to industrialization (Duarte, Sanches, and Dedini Citation2018, 193; Acemoglu and Restrepo Citation2019, 4; Spencer Citation2001, 8).

The latter half of the nineteenth century brought several significant innovations in the mechanization of knitting (Spencer Citation2001, 8, 10). The flat bar machine patented in 1865 by Rev. Isaac Wixom Lamb was used and adapted by the founders of the Dubied and Stoll companies which still exist today (Spencer Citation2001, 192). Varieties of hand-operated “flat” knitting machines are still used by many small producers in Shetland and Ireland, creating garments that are sometimes termed “hand-loomed.”Footnote21

Abrams and Gardner (Citation2021, 169) explain that “hand-operated and then automated knitting machines” were introduced to Shetland “late” compared with mainland Britain, where mechanization was widespread in industry in the end of the nineteenth century. By the 1940s the use of hand-operated machines was established in Shetland factory settings, supporting demand for volume production, and domestic machines became increasingly prevalent during “the postwar decades” (Abrams and Gardner Citation2021, 177). Non-digital electric automation of knitting machines took hold in Shetland in the 1960s (Abrams and Gardner Citation2021, 173). In pre- and post-partition Ireland, successive government initiatives to encourage rural industry included the introduction of knitting machines to increase productivity in economically deprived and depopulated regions. Around the beginning of the 20th century, “The old hand-knitting industry of Donegal, which had almost disappeared because of mechanized competition from Leicester, was stimulated by the [Congested District Board’s] provision of knitting-machines at cost price and on easy terms” (Bourke Citation1993, 114). Later factory-based mechanization of Irish knitting is dramatized in Brien Friel’s play Dancing at Lughnasa, set in 1930s Donegal (see O’Kelly Citation2014, 34). In a 1940 Dáil debate, Seán O’Grady reported that within the knitting industry, “some two-thirds of the wages paid are in respect of flat-machine knitting”Footnote22. Electrification of rural Donegal in the 1950s, just as electricity was reaching particularly rural areas of Shetland, enabled further automation (Sayres Citation2001, 13; Abrams and Gardner Citation2021, 173).

Since the 1980s in both Shetland and Ireland industrial machines, usually still involving flat beds of needles, have been combined with digital programming technology, enabling complex designs and high-volume production to be enacted with minimal physical intervention. Companies providing computerized mass manufacturing processes for knitwear include Dubied, Stoll and Shima Seiki, the Japanese firm whose system is used by the factories encountered in Shetland and Ireland in the course of this research. CAD (computer-aided design) became widespread in the knitwear industry in the 1990s (Abrams and Gardner Citation2021, 186)

Advanced digital automation, although it can increase volume production and offer “an even greater number of pattern-making and garment-shaping possibilities” (Abrams and Gardner Citation2021, 186), also presents obstacles to long-established machine knitting practices. Like many manufacturing processes, the Shima Seiki system (which includes software, machinery, training and repair) is evolving in the direction of increased automation. While “whole garment” machines are available, which reduce the need for separate linking and finishing processes, these are not currently used in Shetland (the perception being that “for fair isle it struggles a bit”Footnote23) and are rarely used by the Irish producers in question here. The models commonly in use by these small-scale producers are flat knitting machines, electrically powered and computer-operated. Updates to this type of software and machinery in recent years have, first, increased digital monitoring and control of physical machinery and, second, provided operators with a greater range of templates, i.e. pre-programmed designs. Small producers of niche, place-based knitwear are already experiencing elements of this global evolution in the direction of automation as challenges.

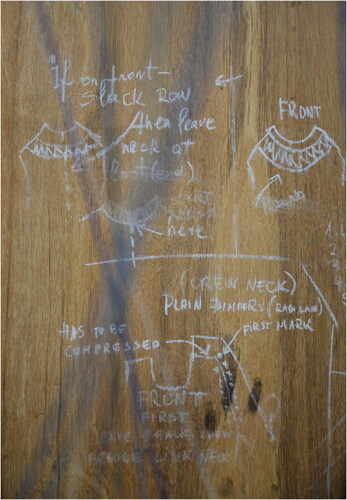

An example from Shetland shows how increased digital monitoring and control of machinery, as integrated software is updated, can have unwelcome consequences by limiting scope for creative improvization. A family-run spinning mill and factory has developed a longstanding core product range of what a manager describes as “traditional fair isle but with lots of colors…thirteen color fair isle. So, we’re pushing to the maximum of what the machines are capable of” (). Footnote24 This business has taken an independent approach to working with machines and software over the years: “you have a problem and you work your way through it”Footnote25 Problem-solving and communication are visible in handwritten notes and drawings on wood near machinery (). Geographical distance from training and repair services, as well as individual aptitude, encourages a creative approach to getting things done. One of the operations this business has long performed with Shima Seiki equipment is knitting pockets into some of its 13-color jacquard fair isle designs. Because of the machine’s limitations (i.e. not being designed to switch from creating one to two separate layers of knit fabric at once), the company achieved these pockets by making physical interventions in the machine. These interventions included “hanging extra carriers off the back rail” and stopping and starting the machine at different phases in its sequence of operations.Footnote26 However, recent system updates make this kind of do-it-yourself workaround more difficult. In newer versions, the software monitors where elements of the physical mechanism are throughout the process, and reacts to interruptions or unexpected sequences of events as potential catastrophes. Talking about this issue, the manager remarked “With older systems you could literally tell the machine to smash itself in half…The new machine doesn’t let you do that…they don’t really want you to”.Footnote27

Figure 7 Fair isle knitwear in progress, Jamieson’s of Shetland. Photo by Susan Timmins as part of this study. Copyright the author. 2018.

Figure 8 Handwritten notes on Jamieson’s of Shetland knitting factory wall. Photo by Susan Timmins as part of this study. Copyright the author. 2018.

Updates to this kind of industrial knitting software are also increasing their emphasis on standard garment templates as starting points. While people can still choose to change or work without these standard starting-points, expectations of the average user and the consequent emphasis of instructional material and training are following the direction of travel toward more digitally automated, lower-intervention ways of working. As Gibson (Citation2016, 65) suggests, there are “lockins between product design and labor process.” The “capacities and affordances” of software and machinery, no less than other “more-than-human materials” (Gibson Citation2016, 65) like wool, shape path-dependent creative decision-making. An Irish knitting factory owner suggested that the shifting affordances of this software are a challenge for producers like himself, saying “we don’t use it the way the big companies do…Shima wants to make the whole world wear the same kind of sweater…we can’t sell that stuff.”Footnote28 During my research I heard that owners of an Irish and a Shetland knitting factory had spoken together about their shared need to find ways around the updated system. It is easy to see why encouraging the idiosyncratic making processes of individual producers might not be a priority for a company like Shima Seiki, which caters to a wide range of businesses around the world and is driven by economies of scale that do not favor small producers of niche knitwear. The sense of the technology as both a powerful tool and, sometimes, an adversary to be outwitted, informs how “skill” is conceptualized in this sector, with greatest respect shown for the skillfulness of those programmers and technicians who can do what “they don’t really want you to.” Their improvizational creativity responds to the changing affordances of machines and software to solve unforeseen problems and produce innovative results.

Advances in industrial knitting software can open up as well as shut down opportunities for creative engagement between people, hands and machines. For example, changes in how programmed items are visually represented by industrial knitting software enable greater mutual understanding between programmers, technicians and designers with little experience of production systems. Advances in Shima Seiki software enable the user to view a programmed design very much as it would look as knitted fabric, including the capacity to scan in specific yarns and simulate how samples knitted in these drape over 3 D forms. This combats the challenge identified by Eckert (Citation2001: 54) in her work on computer aided design in knitwear: “The only model of a knitted structure is a knitted structure.” Modeling what manipulations of specific yarn will result in, to the degree of sensitivity desired for individual garments, is a complicated and costly process, heavily reliant on knitted samples. Matković (Citation2010: 124) suggests that “in the production of knitwear manufacturing technology and design are intermingled in a way that is quite unlike the other branches of industrial design.” For technicians working in small units like Shetland’s Textile Facilitation Unit, with clients who may arrive with anything from “a full tech pack with all the details” to “a scribbly drawing,” technical support, programming and design shade into each other: “It’s not just we’re the technicians, we’re making a program. When customers come in, it’s a consultation.”Footnote29 Ever more accurate simulated sampling addresses the “communication bottleneck” that Eckert (Citation2001: 29) highlighted and opens up more opportunity for creative improvization between people, hands and machine.

The evolving languages of knitting patterns and programs primarily aim to enable mimetic production of knitted items. However, these algorithmic formulas simultaneously fuel creativity by helping information move between times, places and individuals, gathering reinterpretations and new contextual applications as it goes.

Conclusion

Repetition and the mutually disruptive interplay of hand and machine processes are key to creativity in place-based knitting practices. The creative process which results in such textile products such as fair isle and aran knitting is widely recognized as a communal one and set within centuries-long (real and imagined) historical contexts. This popular understanding includes a valorization of hand skills, particularly the improvizational fluency of expert hand knitters of the past. Their remembered ability to work and re-work inherited forms into innovative objects with minimal or no written instruction is an example of the “improvizational dynamics” which make “copying and reproduction…part and parcel of the creative process” (Svašek Citation2016, 2; see also Ingold and Hallam Citation2007). During the twentieth century, Shetland “fair isle” and Irish “aran” knitting experienced commercial success fueled by both hand and machine making practices (Abrams Citation2005; Carden Citation2018b), part of their industrial heritage which influences production today (Gibson Citation2016).

Mechanization, in knitting as elsewhere, is often conflated with de-skilling and diminution of creativity through the replication of forms which are both standardized and divorced from the iterative, artisanal interventions of human hands. Yet in the places where these hand skills are perhaps most romanticized, people who work with and design for machines engage with them creatively, sometimes in idiosyncratic ways. Small industrial knitwear producers in places like Shetland and rural Ireland work within the same ecosystem of machinery, software and training as many large-scale producers around the world. In so doing, these producers of place-based products make a name for themselves in the complex landscape between alienated automation and anonymised “tradition,” using the material and cultural resources of small places to practically champion the much-theorised “situated” nature of creativity (Price and Hawkins Citation2018, 6); asserting that as a factory manager in Shetland put it, “we manipulate these machines.”Footnote30

With the increasing globalization of the mass market apparel industry, fair isle and aran knitwear styles have been absorbed into an international design lexicon that is drawn on by a wide range of producers. Contemporary commercial producers of knitwear in Shetland and Ireland distinguish themselves from their international mass market counterparts by emphasizing their enmeshment in living, longstanding, communal web of hand and machine-making practices. This kind of making culture is creatively animated by the replication and transformative transposition of designs and practices between different kinds of knitters and different modes of making.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Siún Carden

Dr. Siún Carden is a Research Fellow in the University of the Highlands and Islands’ Center for Island Creativity, in Shetland. Her background is in social anthropology and her current research interests include creative economies, art and social practice, islands and knit textiles. [email protected]

Notes

1 For the purposes of this article, Fair Isle and Aran refer to islands while fair isle and aran refer to styles of knitting.

2 Shima Seiki is one brand of commercial knitwear machinery, which is highly automated and integrated with design software, enabling efficient industrial production. Flat-bed and v-bed machines operate on the same basic principle of yarn being carried across a bed of needles which incorporate it into the growing fabric, but they are hand-operated or only lightly mechanised and hence are sometimes called hand-flats.

3 Interviewee 4, interviewed by author, Donegal (Ireland), 18/12/18

4 e.g. Jamieson’s of Shetland and Donegal Yarns

5 Oliver Henry of Jamieson and Smith wool brokers demonstrates wool sorting daily during Shetland Wool Week.

6 Interviewee 16, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland) 16/11/16; Interviewee 17, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland) 7/1/16; Interviewee 14, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland), 09/11/18

7 Interviewee 2, interviewed by author, Inis Meáin (Ireland), 18/10/18.

8 See ‘The Handsome Chris Pullover (from Knives Out)’ by Caryn Shaffer, Citation2020. Online at https://www.ravelry.com/patterns/library/the-handsome-chris-pullover. Accessed 31/01/22.

9 Interviewee 20, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland), 16/12/16.

10 This hand-and-machine fair isle yoke jumper production method was also used in the past in Ireland ‘when a big demand came in for them’, as reported by Interviewee 3, interviewed by author, Donegal (Ireland), 17/12/18. In Sayres (Citation2001, 12), a Donegal knitter remembers “We all knitted fair isles…for a few years until the Aran sweaters became fashionable.”

11 Interviewee 21, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland) 08/12/16.

12 Interviewee 16, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland) 16/11/16.

13 A Conversation on Fair Isle Knitting with Hazel Tindall and Janette Budge, 2020. Produced by Shetland Amenity Trust as part of Shetland Wool Week. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_mAKHFSkLUk. Accessed 13/10/22.

14 Interviewee 21, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland) 08/12/16

15 Interviewee 20, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland) 16/12/16

16 Ibid.

17 Interview 19, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland) 25/10/16

18 Interviewee 4, interviewed by author, Donegal (Ireland), 18/12/18

19 Edel MacBride, Twitter post, 20/02/19, http://twitter.com/edelspirit

20 Interviewee 18, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland) 17/01/17

21 Interviewee 3, interviewed by author, Donegal (Ireland),17/12/18

22 Vote 54 – Gaeltacht Services. Dáil Éireann (10th Dáil), Committee on Finance. 17/04/1940. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1940-04-17/20/. Accessed 13/10/2022.

23 Interviewee 15, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland), 12/10/185

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Interviewee 2, interviewed by author, Inis Meáin (Ireland), 18/10/18

29 Interviewee 11, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland), 21/11/18

30 Interviewee 15, interviewed by author, Mainland (Shetland), 12/10/185

References

- Shetland Museum and Archives. 2017. “Oasis Inspired by Shetland Museum Textile Collection.” Accessed 31 January 2022. https://www.shetlandmuseumandarchives.org.uk/blog/oasis-inspired-by-shetland-museum-textile-collection.

- Abrams, Lynn. 2005. Myth and Materiality in a Woman’s World: Shetland 1800–2000. Manchester: Manchester University Press

- Abrams, Lynn. 2012. “There is Many a Thing That Can Be Done with Money”: Women, Barter, and Autonomy in a Scottish Fishing Community in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 37 (3): 602–609. doi:10.1086/662700

- Abrams, Lynn, and Lin Gardner. 2021. “Recognising the Co-Dependence of Machine and Hand in the Scottish Knitwear Industry.” Textile History 52 (1–2): 165–189. doi:10.1080/00404969.2021.2014768

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo. 2019. “Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33 (2): 3–30. doi:10.1257/jep.33.2.3

- Arnold, Christine. 2010. “An Assessment of the Gender Dynamic in Fair Isle (Shetland) Knitwear.” Textile History 41 (1): 86–98. doi:10.1179/174329510x12670196126683

- BBC. 2015. “Chanel Apologises over Mati Ventrillon Shetland Knitwear Designs.” BBC News NE Scotland, Orkney & Shetland, 8–12. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-35042291

- Beattie, Sean. 2013. Donegal in Transition: The Impact of the Congested Districts Board. Newbridge, Ireland: Merrion.

- Bennett, H. M. 1981. “The Origins and Development of the Scottish Hand-Knitting Industry.” [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Edinburgh.

- Bourke, Joanna. 1993. “Home Industries.” In Husbandry to Housewifery: Women, Economic Change, and Housework in Ireland 1890–1914, edited by Joanna Bourke. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Breathnach, Ciara. 2004. “The Role of Women in the Economy of the West of Ireland, 1891–1923”. New Hibernia Review 8 (1): 80–92. doi:10.1353/nhr.2004.0017

- Breitenfeldt, Sara, Suzanne McEndoo, and Evin Bail O’Keeffe. 2015. These Islands: Knits from Ireland, Scotland, and Britain. Cork, Ireland: Anchor and Bee.

- Byron, Reginald, and Graham McFarlane. 1980. Social Change in Dunrossness: A Shetland Study. London, UK: Social Science Research Council

- Byron, Reginald. 1986. Sea Change: A Shetland Society, 1970–1979, No. 32. St. John’s, Newfoundland: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Carden, S. 2018a. Shetland Hand Knitting: value and Change. Lerwick, UK: University of the Highlands and Islands.

- Carden, S. 2018b. “The Aran Jumper.” In Design Roots: Local Products and Practices in a Globalized World, eds. Stuart Walker, Martyn Evans, Jeyon Jung, Tom Cassidy and Amy Twigger-Holroyd. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic

- Carden, S. 2019. “The Place of Shetland Knitting.” Textile 17 (4): 357–367. doi:10.1080/14759756.2019.1639416

- Carr, Chantel, and Chris Gibson. 2016. “Geographies of Making: Rethinking Materials and Skills for Volatile Futures.” Progress in Human Geography 40 (3): 297–315. doi:10.1177/0309132515578775

- Chapman, Roslyn. 2015. “The History of the Fine Lace Knitting Industry in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Shetland.” PhD, University of Glasgow.

- Christiansen, C. 2016. “Introduction.” In A Shetlander’s Fair Isle Graph Book, Shetland Guild of Spinners, Dyers and Weavers, 7–13. Lerwick, UK: Shetland Times.

- Cléir, Síle de. 2011. “Creativity in the Margins: Identity and Locality in Ireland’s Fashion Journey.” Fashion Theory 15 (2): 201–224.

- Dawson, Pam. 1998. Traditional Island Knitting: Including Aran, Channel Isles, Fair Isle, Falkland Isles, Iceland and Shetland. Tunbridge Wells, UK: Search Press, Limited.

- Dodson-Snowden, Emily. 2022. “Knitting Code: Examining the Relationship between Knitting and Computational Thinking Skills Using the Nexus of Practice.” Theses and Dissertations – Education Sciences, University of Kentucky.

- Duarte, Adriana Yumi Sato, Regina Aparecida Sanches, and Franco Giuseppe Dedini. 2018. “Assessment and Technological Forecasting in the Textile Industry: From First Industrial Revolution to the Industry 4.0.” Strategic Design Research Journal 11 (3): 193–202. doi:10.4013/sdrj.2018.113.03

- Eckert, Claudia. 2001. “The Communication Bottleneck in Knitwear Design: Analysis and Computing Solutions.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 10 (1): 29–74. doi:10.1023/A:1011280018570

- Frew, Terry. 2011. The Creative Industries: Culture and Policy. London, UK: Sage.

- Fryer, Linda. G. 1995. Knitting by the Fireside and on the Hillside: History of the Shetland Hand Knitting Industry c.1600–1900. Lerwick: Shetland Times Ltd.

- Garnham, Nicholas. 2005. “From Cultural to Creative Industries.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 11 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1080/10286630500067606

- Gibson, C. 2016. “Material Inheritances: How Place, Materiality, and Labor Process Underpin the Path-Dependent Evolution of Contemporary Craft Production.” Economic Geography 92 (1): 61–86. doi:10.1080/00130095.2015.1092211

- Hallam, E. and Ingold, T. (eds) 2007. Creativity and Cultural Improvisation. New York, NY: Berg

- Hawkins, Harriet. 2016. Creativity. London: Routledge.

- Holroyd, Amy Twigger, Tom Cassidy, Martyn Evans, Elena Gifford, and Stuart Walker. 2015. “Design for “Domestication”: the Decommercialisation of Traditional Crafts.” The Value of Design Research: 11th European Academy of Design Conference, Paris.

- Humphreys, Sal. 2009. “The Economies within an Online Social Network Market: A Case Study of Ravelry.” In ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation. Brisbane, Australia: QUT Brisbane: Creative Industries Faculty.

- Irish Tourism Group. 2022. “Knitting Tours.” https://www.knittingtours.com/knitting-tours/. Accessed 31 January 2022.

- Laurenson, Sarah (Ed.). 2013. Shetland Textiles: 800 BC to the Present. Lerwick, UK: Shetland Amenity Trust.

- Luckman, Susan. 2012. Locating Cultural Work. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Mann, Joanna. 2017. “Knitting the Archive: Shetland Lace and Ecologies of Skilled Practice.” Cultural Geographies 25 (1): 91–106. doi:10.1177/1474474016688911

- Matković, Vesna Marija Potočić. 2010. “The Power of Fashion: The Influence of Knitting Design on the Development of Knitting Technology.” Textile 8 (2): 122–146. doi:10.2752/175183510X12791896965493

- Meyer, B. 2016. “Afterword: Creativity in Transition.” In Creativity in Transition: Politics and Aesthetics of Cultural Production across the Globe, edited by M. Svašek, and B. Meyer, vol. 6, 312–318. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Mower, S. 2016. “Alexander McQueen Spring 2017 Ready-to-Wear Collection.” Vogue. https://www.vogue.com/fashion-shows/spring-2017-ready-to-wear/alexander-mcqueen. Accessed 31 January 2022.

- O’Kelly, Hilary. 2014. Cleo: Irish Clothes in a Wider World. Dublin: Associated Editions.

- Orton-Johnson, Kate. 2013. “Knit, Purl and Upload: New Technologies, Digital Mediations and the Experience of Leisure.” Leisure Studies 33 (3): 305–321. doi:10.1080/02614367.2012.723730

- Pearson, Michael. (1984) 2015. Michael Pearson’s Traditional Knitting: Aran, Fair Isle and Fisher Ganseys, New & Expanded Edition. New York, USA: Courier Dover Publications.

- Pierce, Jennifer Burek. 2014. “Knitting as Cultural Heritage: Knitting Blogs and Conservation.” In Annual Review of Cultural Heritage Informatics: 2012–2013, edited by Samantha K. Hastings, 63–76. Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Platt, Louise. C. 2019. “Crafting Place: Women’s Everyday Creativity in Placemaking Processes.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 22 (3): 362–377. doi:10.1177/1367549417722090

- Pöllänen, Sinikka, and Kari Pöllänen. 2019. “Beyond Programming and Crafts: Towards Computational Thinking in Basic Education.” Design and Technology Education 24 (1): 13–32.

- Price, L, and H. Hawkins. 2018. Geographies of Making, Craft and Creativity. Oxon, UK: Routledge

- Sayres, M. 2001. “Conversations in Donegal: Mary McNellis and Con O’Gara.” New Hibernia Review 5 (3): 9–21. doi:10.1353/nhr.2001.0052

- Shaffer, Caryn. 2020. “The Handsome Chris Pullover (from Knives Out).” Ravelry. https://www.ravelry.com/patterns/library/the-handsome-chris-pullover. Accessed 31 January 2022.

- Spencer, D. J. 2001. Knitting Technology: A Comprehensive Handbook and Practical Guide. Cambridge, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Starmore, Alice, and Anne Matheson. 1983. Knitting from the British Islands: 30 Original Designs from Traditional Patterns. London: Book Club Associates

- Svašek, M. 2016. “Introduction.” In Creativity in Transition: Politics and Aesthetics of Cultural Production across the Globe: 6, edited by M. Svašek and B. Meyer, 1–32. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Thompson, Gladys. 1971. Patterns for Guernseys, Jerseys, and Arans: Fishermen’s Sweaters from the British Isles. Massachusetts, USA: Courier Corporation.

- Turney, Joanne. 2009. The Culture of Knitting. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Wenger, Etienne. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger-Trayner, Etienne, Mark Fenton-O’Creevy, Steven Hutchinson, Chris Kubiak, and Beverly Wenger-Trayner, eds. 2014. Learning in Landscapes of Practice: Boundaries, Identity, and Knowledgeability in Practice-Based Learning. London New York: Routledge.