ABSTRACT

Background: There is a need to better understand HPV vaccination (HPVv) implementation in WHO Europe Region (WHO/ER), including recommendations, funding, and vaccination coverage rates (VCR).

Methods: A targeted literature review (up to 31 January 2020) was conducted using national health ministry websites, WHO database, and published studies from WHO/ER countries (n = 53). HPVv recommendations and funding data (target age, gender, schedule, setting, target and monitored VCR) for primary and catch-up cohorts were collected.

Results: National recommendations for HPVv exist in 46/53 (87%) countries, of which 38 (83%), 2 (4%), and 6 (13%) countries provided full, partial, or no funding, respectively, for the primary cohort. Fully or partially funded HPVv was provided for girls only in 25/53 (47%) countries and for both boys and girls in 15/53 (28%) countries. HPVv catch-up was fully or partially funded in 14/53 (26%) countries. Among 40 countries with a national immunization program (NIP), monitored VCRs ranged from 4.3% to 99% (n = 30). Of the 10 countries reporting VCR targets, only Portugal exceeded its target.

Conclusion: Of the 53 WHO/ER countries, 40 have funded HPVv NIPs, among which 30 report VCRs. Additional efforts are required to ensure HPVv NIPs are fully funded and high VCRs maintained.

1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is linked to a number of anogenital (cervical, vaginal, vulvar, anal) and oropharyngeal cancers [Citation1]. Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer affecting women in the European Union (EU) with an estimated 33,000 new diagnoses and 15,000 deaths annually [Citation2]. HPV vaccines were introduced in 2006 [Citation3] and their safety and effectiveness are now well established [Citation4–6]. Their safety and efficacy have been proven, included in their product information leaflet, and are continuously evaluated by the European Medicines Agency [Citation7–9]. HPV vaccines have been steadily incorporated in primary prevention programs worldwide, with 100 out of 195 countries having implemented national HPV vaccination (HPVv) programs as of October 2019 [Citation10]. The European Society of Gynecologic Oncology (ESGO) supports vaccination programs for children and young adolescents, with a catch-up program for young adults, if feasible, and also vaccination on an individual basis [Citation11].

HPVv programs for adolescents have been recommended by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Although the European region has been considered among the most developed with advanced health systems, implementation of HPVv programs has varied considerably across Europe, due to differences in political will, and funding availability in individual countries [Citation12–18].

One of the important measures of success for a national immunization program (NIP) is the vaccine coverage rate (VCR) [Citation19]. The importance of achieving a high VCR and meeting VCR targets defined at a national level is underscored by the European Vaccine Action Plan 2015–2020 (EVAP) [Citation20], published by the WHO Regional Office for Europe (WHO/ER, which covers 53 countries; see Supplementary Table 1 for a full list). However, the approaches used to measure, report, and monitor VCRs are heterogenous across countries [Citation19].

To describe the current state of implementation of HPVv programs for adolescents in the World Health Organization European Region (WHO/ER) we reviewed publicly available data on the status of these programs, including both target and actual VCRs for all 53 WHO/ER nations.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

Between August 2018 and January 2020, a targeted literature review was performed to search the internet for available information on HPVv recommendations and programs, and on target and actual HPVv VCRs in WHO/ER countries. The following keywords were used: ‘HPV + [Country name],’ ‘HPV program + [Country name],’ ‘HPV vaccination + [Country name],’ ‘HPV vaccination coverage + [Country name],’ ‘HPV target coverage + [Country name].’ Individual searches were conducted to translate these keywords using the local languages of all 53 countries. Whenever relevant, peer-reviewed publications indexed on PubMed until 31 January 2020 were included in this review.

2.2. Data sources

Data sources were stratified into primary, secondary, and tertiary data sources (see Supplementary table 2). Primary data sources included official government and national health service websites, while secondary data sources included peer-reviewed publications and association websites. Tertiary data sources used included the WHO, the HPV Information Centre, and websites of nonprofit non-governmental organizations (NGO). Tertiary sources were only used if primary and secondary data sources were not available. Data on regional vaccination programs were only included in countries where regional authorities are autonomous (i.e. Spain and Italy) and to a large extent independent of the national authority in the implementation of vaccination programs.

Data on HPVv recommendations, programs, target, and actual VCRs in 44 out of 53 WHO/ER countries were further validated by local experts employed by MSD. Data for the following countries did not undergo local validation: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Iceland, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkey.

2.3. Data collection

To identify data on the recommendation for HPVv, implementation of HPVv, and target and actual VCRs across countries, the following data fields were extracted where available: recommendation regarding HPVv; year of HPVv program introduction; target population of HPVv (primary and catch-up cohorts if available); age and gender of target population; HPVv funding status; main location where HPVv was administered in the primary cohort; future plans for implementing gender-neutral vaccination (GNV) HPVv programs; VCR target (including the defined number of doses, population, and timeframe); and monitored VCR (including the defined number of doses, population, and time of assessment). No calculation was undertaken on VCRs; VCRs were presented as reported in the sources.

Given that the aim of this research was to review adolescent HPVv (including catch-up cohorts, and associated target and monitored VCRs), data on recommendations, funding, and VCRs for risk groups were out of the scope of this study. The key definitions used during data collection and analysis are shown in .

Table 1. Key definitions of categories used during the data collection

2.4. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Countries were categorized according to the level of out-of-pocket payment required in order for individuals to obtain HPVv as follows: Fully Funded, where no out-of-pocket payment was required; Partially Funded, if a partial out-of-pocket payment was required, and No Funding, where the full cost of the vaccination was covered by the individual (see ).

Countries were grouped into four categories based on their HPVv recommendation and implementation status, as follows: Recommendation and Funding (partial or full), Recommendation Only (no funding), and No Recommendation or Funding (see ). The fourth category (no data) included countries for which there were no data available on HPVv recommendation or funding (see ).

Countries where HPVv was supported by external funding sources such as GAVI (Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization) were included in the Recommendation and Funding (partial or full) category. In countries with NIPs traditionally funded at a national level (i.e. centralized system), but with a national recommendation for HPVv with no funding and only several different pilots or regional programs in place, the country in question was included in the Recommendation Only category. Countries with a decentralized healthcare system, regional implementation of nationally recommended programs were included in the Recommendation and Funding category. While data have been reported separately for the Belgium regions of Flanders and Wallonia-Brussels, results have been categorized and counted as a single country for the purpose of this study.

Finally, where countries provide full funding for one brand of HPVv but not all brands of HPVv, such countries have been categorized as providing full funding (fully funded).

In line with a recent study that reviewed VCRs for HPVv in 30 countries in the European Union/European Economic Area and Switzerland [Citation21], we categorized each country based on VCR level as follows: high VCR (≥71% coverage), moderate VCR (51–70% coverage), low VCR (31–50% coverage), and very low VCR (≤30% coverage).

Where available, the dose associated with the VCR has been reported in this study. Where countries reported a monitored VCR following both the 1st and 2nd doses of HPVv, data pertaining to both doses have been collected. Countries that did not report the number of doses associated with the monitored VCR have been labeled as ‘Unclear (i.e. ≥1).’

3. Results

3.1. Overview of HPVv recommendation and funding in WHO/ER for the primary cohort

Of the 53 countries included in the analysis, HPVv for the primary cohort was categorized as No Recommendation or Funding in 7 (13%) countries (Albania, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Ukraine) and Recommendation Only (no funding) in 6 (11%) countries (Andorra, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Kazakhstan, Poland, the Russian Federation, and Serbia) (). The remaining 40 (75%) countries were categorized as Recommendation and Funding (partial or full), of which 2 (4%) countries were categorized as providing partial funding (France and Monaco), while 38 (72%) countries were categorized as providing full funding.

Table 2. Overview of HPVv recommendations for primary cohorts by country in WHO/ER (n = 53)

Among the 46 countries with a national recommendation on HPVv for a primary cohort of adolescents (i.e. regardless of the funding status), 25 (54%) countries recommended HPVv for primary cohorts of girls only and 21 (46%) for primary cohorts of girls and boys (). Among the 25 countries with girls only HPVv recommendations, 21 (84%) provide full funding, and 4 (16%) no funding. Among the 21 countries with girls and boys HPVv recommendations, 15 (71%) provide full funding for girls and boys, and 4 (19%) funding for girls only (boys recommended only), and 2 (10%) no funding for girls or boys.

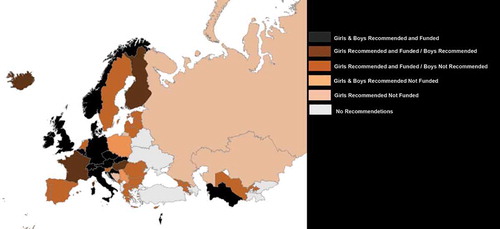

A map of HPVv funding for the primary cohort is presented in .

Figure 1. Recommendations and funding status across the WHO/ER for the primary cohort in girls and boys

The ages at which HPVv was available for primary cohorts varied across the 46 countries with HPVv national recommendation for a primary cohort of adolescents (i.e. regardless of the funding status). Ages at which HPVv was recommended were age 12 (n = 16, 35% countries), age 11 (n = 11, 24%), age 9 (n = 6, 20%), age 13 (n = 5, 11%), age 10 (n = 4, 9%) and age 14 (n = 1, 2%). In Iceland, the recommended HPVv starting age for primary cohorts differed for boys (age 9) and girls (age 12), while in Belgium the starting age differed between regions (age 12 in Flanders, and age 13 in Wallonia-Brussels). There were no available data on the recommended age of HPVv for the primary cohorts of Bosnia & Herzegovina.

Five countries within the WHO/ER reported regional variations in the implementation of HPVv programs. In Poland and the Russian Federation where there are no national programs, HPVv was implemented and managed by regional/municipal authorities. In Belgium, as for every vaccination program, HPVv was independently implemented by the two regional authorities (Flanders and Wallonia-Brussels) (). Finally, in Spain and Italy where vaccination programs are managed by regional authorities, there were some regional differences in the population (in terms of age and gender) eligible for HPVv programs (see Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 for detailed information on these two countries).

3.2. Vaccination setting for HPVv programs in WHO/ER for the primary cohort

Among the 40 countries with funding for HPVv, 17 (43%) countries delivered HPVv for primary cohorts at schools only while 16 (40%) countries delivered HPVv via healthcare centers only (see , and Supplementary Table 5). In Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, and Uzbekistan, HPVv programs were delivered via both schools and healthcare centers. For the remaining three countries (Moldova, Montenegro, Armenia), no information was available on the setting of HPV vaccination (see , and Supplementary Table 5).

Table 3. List of WHO/ER countries with a reported HPVv recommendation and/or program for the catch-up cohort (n = 18)

3.3. Overview of HPVv recommendation and funding in WHO/ER for catch-up cohorts

A total of 17/53 (32%) countries within the WHO/ER had implemented HPVv recommendations (with or without funding) for catch-up cohorts. Of these 17 countries, 14 (82%) were categorized as Recommendation and Funding (partial or full) and 3 (18%) were categorized as Recommendation Only (no funding) ().

Table 4. List of WHO/ER countries reporting a monitored VCR (n = 30) †.

Of the 14 countries categorized as Recommendation and Funding (partial or full), a total of 9 (64%) countries provided full funding for HPVv catch-up programs (Denmark, Germany, Israel, Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK), while the remaining five (36%) provided partial funding (Austria, Belgium, France, Italy, and North Macedonia). A total of seven WHO/ER countries reported full or partial funding for GNV HPVv for catch-up cohorts as of January 2020 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Israel, Switzerland, and the UK) (). Three countries (France, Finland, and Iceland) provided funding for HPVv for girls but not for boys (boys had recommendation only) at the time this study was carried out ().

Catch-up HPVv was provided for diverse age groups, starting at as young as 12 years (in Italy and Belgium) and including those aged up to 26 years (in Italy, North Macedonia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden). Catch-up HPVv in all other countries was provided for age groups falling between these two age thresholds (), although catch-up HPVv was provided at any age in some regions of Italy (see below).

Regional variations in eligibility (in terms of age and gender) for catch-up HPVv were identified in Italy, Spain, and Switzerland (see supplementary materials for full details). In Italy, age-based eligibility for the catch-up cohort was defined as 12–18, 12–25, 12–26, or not restricted (i.e. HPVv is given at any age), depending on the region. In Spain meanwhile, catch-up HPVv was offered to groups aged between 14 and 26, with different autonomous regions defining different eligible age groups within this range. Finally, in Switzerland catch-up, HPVv was available for both girls and/or boys between 15 and 19 years of age, with variations in the exact eligibility criteria across the country’s cantons.

3.4. Monitored and target VCR for HPVv in the primary cohort across WHO/ER

Monitored VCR for HPVv was reported for 30/53 (57%) WHO/ER countries. The definition of VCR varied across countries, with VCRs reported following at least one dose for 5 (17%) countries and following at least two doses for the remaining 25 (83%) countries (). Ten (33%) of the 30 countries had defined a national VCR target for HPVv for the primary cohort ().

Table 5. List of WHO/ER countries with target VCR (n = 10)

Of the 25 countries reporting a monitored VCR following at least two doses of HPVv, 24 (80%) pertained to a primary cohort of girls. Of the 24 countries, 10 (42%) (including Flanders region of Belgium) reported a high VCR (i.e. ≥71%), six (25%) countries reported a moderate VCR (i.e. 51–70%), six (25%) countries (including Wallonia-Brussels region of Belgium) reported a low VCR (i.e. 31–50%), and three (13%) countries had a very low VCR (≤30%) (note that data for Belgium were reported separately for the Flanders and Wallonia-Brussels regions, leading to a total of 25 VCRs in this instance).

Meanwhile, among the five countries that reported a monitored VCR following at least one dose of HPVv for girls, two (40%) countries (Austria and the Czech Republic) reported a moderate VCR (i.e. 51–70%), while two (40%) countries (Germany and Slovenia) reported a low VCR (i.e. 31–50%) and one (20%) country (Kazakhstan) reported a very low VCR (i.e. ≤30%).

Just four countries with a GNV program (Austria, Czech Republic, Italy, and Switzerland) reported a monitored VCR for boys, which in all cases was categorized as either low (Austria) or very low (Czech Republic, Italy, and Switzerland). Israel reported a combined monitored VCR for boys and girls, which also fell in the ‘low’ category (). This is expected to the extent that the vast majority of HPVv programs for boys started only recently, sometimes several years after the introduction of HPVv programs for girls.

Of the 10 countries reporting both a target and monitored VCR for HPVv (), only Portugal exceeded its VCR target, which was set at 85% for 10–14 year-old girls, while its monitored VCR stood at 90–94% for the 2004–2006 female birth cohort who received two HPVv doses in 2018. In countries with a monitored VCR that was lower than their VCR target, the difference between the target and the monitored VCR ranged from 6% to 71%, with the UK, Sweden, and Ireland being the closest to achieving their respective VCR targets ().

4. Discussion

This study reviewed the recommendations and funding for HPVv in primary (i.e. adolescent) and catch-up cohorts in WHO/ER countries, in addition to the available monitored and target VCRs for these countries. The present study has included the entire WHO/ER region, a wider range and number of countries compared to similar previously conducted reviews [Citation21,Citation22], and we were additionally able to identify data on VCR for cohorts of boys, which has not, to our knowledge, been previously reported.

Overall, our study showed that a high proportion of WHO/ER countries (46/53, i.e. 87%) were found to have recommendations for HPVv in place for adolescent girls. Of the countries with recommendations, the majority provided full funding (n = 38, i.e. 83%), while two (4%) provided partial funding and six (13%) provided no funding. Full funding of HPV vaccination programs has shown to drive HPVv success measured by higher VCR [Citation23].

More than half of all countries with HPVv recommendations in place recommended vaccination exclusively for girls (n = 25, i.e. 54%), while the remaining 21 countries (46%) recommended HPVv for both boys and girls (i.e. GNV), although no funding was provided for boys in 6 (29%) of these countries. Of the seven countries offering GNV, for the catch-up cohort, five had fully funded programs while two (Austria and Belgium) offered partial funding only. However, five countries (the Netherlands, Portugal, and Sweden) plan to extend fully funded HPVv programs for boys effectively starting in 2020 (Portugal, Sweden, Finland) and in 2021 (France and the Netherlands).

While a substantial proportion of WHO/ER countries have implemented HPVv and an increasing number are including boys in such programs, the proportion of primary populations that have been successfully vaccinated under such programs (as determined by the monitored VCR) varies considerably across countries. Data regarding monitored VCR were reported for a total of 30 countries (although data for Belgium were split for Flanders and Wallonia-Brussels, giving a total of 31 VCRs), and ranged from as low as 4% in Bulgaria to 99% in Turkmenistan. In the present study, countries were most commonly classified as having a High VCR for girls (i.e. ≥71% coverage) (n = 10/30; 33%), followed by low VCR (i.e. 31–50% coverage) (n = 8/30; 27%) next most common, then moderate VCR (i.e. 51–70% coverage) (n = 8/30; 27%) and finally very low VCR (i.e. ≤30% coverage) (n = 4/30; 13%). Of the 15 countries with GNV programs, only (27%) reported monitored VCRs for boys which were classified as either ‘low’ or ‘very low.’ The VCRs reported for boys were lower than those reported for girls in the same countries, which is consistent with the fact that the majority of HPVv programs for boys started several years after those initiated for adolescent girls. This gap between VCRs for boys and girls was highest in Italy, where coverage for boys and girls differed by 45%, followed by Switzerland (43%), Czech Republic (30%), and Austria (20%).

We were unable to find reports of monitored VCRs for 16 of the 46 WHO/ER countries (35%) that have HPVv programs. This could be attributed to a small period of time between the implementation of the HPVv program and the commencement of this study. This could also be due to a lack of HPVv monitoring and reporting practices as described by Nguyen-Huu et al. who proposed several reasons for observed fluctuations and differences in monitored VCR including affordability of vaccines, mandatory requirements for a medical prescription in order to receive HPVv, and previous HPV vaccine controversies within a country [Citation21]. Other studies have also suggested that the setting of vaccination (e.g. school vs healthcare center), availability of catch-up HPVv programs, centralized vs. decentralized program delivery, and social norms and values (e.g. related to sexual activity) were additionally noted as reasons for HPVv VCR variability in different countries [Citation19,Citation24,Citation25].

Due to the limited information on heterogeneity across and within WHO/ER in the way countries monitor, collect and report VCR, further country-specific analysis will be required to articulate the factors within HPVv programs that impact coverage and to confirm the accuracy of the data published. However, the absence of reported VCRs for HPVv in 10 countries and lack of updated VCRs in WHO/ER hinder the interpretation of VCRs across countries. Furthermore, a rigorous comparison across all monitored VCRs in WHO/ER was not feasible due to variations in the way VCR is reported, as highlighted by Markowitz et al. (2012) [Citation26]. There is substantial variation in the way the VCR is reported in terms of the year, the age of the target cohort, the strategy adopted to implement the HPVv program, and the number of doses received by the target population (with some defining coverage as having received two doses of HPVv, while others defining it as having received at least two doses).

There is a need to improve HPVv programs, and to monitor and report HPVv coverage across WHO/ER, using standardized processes and guided by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. An in-depth analysis of VCR data according to standard pre-defined VCR measurements is required in order to analyze the VCR gaps between countries and potentially find indicators that limit or increase coverage of HPVv in childhood and adolescent populations.

In a recent publication [Citation27], WHO’s global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer proposes a vision of a world where cervical cancer is eliminated as a public health problem (i.e. a threshold of 4 per 100 000 women-years) and includes (1) 90% of girls fully vaccinated with HPV vaccine by age 15 years, (2) 70% of women are screened with a high-performance test by 35 years of age and again by 45 years of age, and (3) 90% of women identified with cervical disease receive treatment (90% of women with precancer treated, and 90% of women with invasive cancer managed). These targets must be met by 2030 for countries to be on the path toward cervical cancer elimination [Citation27]. Given the current VCRs summarized in this targeted review, there are still improvements to make to reach the WHO’s 90% VCR target for HPV vaccine in girls up to 15 years of age.

4.1. Limitations

Findings of this review were mainly limited by variations in data availability which limited the choice of study approach to performing a targeted literature review. Data collection was based on publicly available online sources from official websites (e.g. those belonging to national governments and ministries of health). As such, the data included may not capture information regarding prospective policy changes released via online news outlets, meetings, conferences, etc. Moreover, it should be noted the data in this study correspond to a specific time period (i.e. up to 31 January 2020), and therefore any updates that have taken place on government/ministry of health websites since then are not reflected in this study.

5. Conclusions

Fourteen years after the initial licensing of HPVv in 2006, fully funded HPVv programs are provided for the primary cohort in 38 out of 53 (72%) countries included in the WHO/ER region. Furthermore, 15 (28%) countries provide fully funded GNV HPVv programs for primary cohorts, while 7 (13%) provide full or partial funding for GNV HPVv catch-up cohorts, thus offering equal access to protection against HPV related cancer and diseases. As of 31 January 2020, 6 (11%) countries recommended HPVv without having implemented a program, and 7 (13%) countries still have no recommendation nor implementation of HPV immunization for childhood and adolescent populations. The majority of countries (81% or 43/53) have not established a VCR target for HPVv, while a substantial number of those with recommendations in place for HPVv did not report a monitored VCR (16/46 countries). Our study indicates considerable room for improvement in both the reporting of monitored VCRs and in increasing the HPVv VCR for all cohorts across countries in WHO/ER.

This is particularly the case for boys, for whom reporting of VCR was found to be less frequent and, when reported, substantially lower than VCR for girls within the same country, although this is often the result of boys HPVv programs starting at a later date, sometimes years after the introduction of HPVv programs for girls. Efforts in comparing and contrasting HPVv VCR across WHO/ER countries would be aided by consistent national requirements for regularly measuring and reporting HPVv VCR. Such efforts are to be encouraged, as monitoring is critical for gauging the success of HPVv programs, detecting low VCRs, and addressing them.

Author contributions

PF, TB, SV, NG, and RD were responsible for the study conception and design; NG was responsible for data collection. All authors were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data. NG was responsible for the initial draft of the manuscript, all authors reviewed the content, revised it critically for intellectual content, and approved the final version for publication. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work described in this study.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Declaration of interest

Paolo Bonanni received grants for epidemiological and HTA research projects from GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, and Seqirus and fees for taking part in advisory boards on different vaccines from the same companies. Pier Luigi Lopalco received grants for specific research projects from GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, and Pfizer and fees for taking part in advisory boards on different vaccines from GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, and Seqirus. Elmar A. Joura has received advisory board fees and lecture fees from MSD and Roche Diagnostics and research grant through Medical University from Merck. Nathalie Gemayel is a full-time employee at Amaris Consulting which has received funding for the completion of the present study. Pascaline Faivre, Stefan Varga, Tobias Bergroth, and Rosybel Drury are full time employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. (MSD), a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Medical writing support, provided by Khalid Siddiqui from Amaris Consulting UK Ltd, was utilized in the production of this manuscript and funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (106.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yousra Khecha, Raina Jia, and Loukia Mantzali from Amaris Consulting UK Ltd for support with secondary research on HPV recommendation status in WHO European countries. The authors would like to thank our expert colleagues in MSD subsidiaries of WHO European regions who further validated our data points.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Human papillomaviruses. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2007;90:1–636.

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control. Factsheet about human papillomavirus; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/human-papillomavirus/factsheet

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007 Mar 23;56(RR–2):1–24.

- Arbyn M, Xu L. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic HPV vaccines. A Cochrane review of randomized trials. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018 Dec;17(12):1085–1091.

- Garland SM, Kjaer SK, Munoz N, et al. Impact and effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: a systematic review of 10 years of real-world experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 15;63(4):519–527.

- Drolet M, Benard E, Perez N, et al. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019 Aug 10;394(10197):497–509.

- European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics (EPAR): gardasil 9 2020; 2020 Nov [cited 2020 May 06]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/gardasil-9

- European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics (EPAR): gardasil 2020; 2020 Nov [cited 2020 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/gardasil

- European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics (EPAR): cervarix 2020; 2020 Nov [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cervarix

- World Health Organization. Major milestone reached as 100 countries have introduced HPV vaccine into national schedule; 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/31-10-2019-major-milestone-reached-as-100-countries-have-introduced-hpv-vaccine-into-national-schedule

- Joura EA, Kyrgiou M, Bosch FX, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination: the ESGO–EFC position paper of the European Society of Gynaecologic Oncology and the European Federation for Colposcopy. Eur J Cancer. 2019;116:21–26.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidance for the introduction of HPV vaccines in EU countries; 2008. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/0801_GUI_Introduction_of_HPV_Vaccines_in_EU.pdf

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Introduction of HPV vaccines in EU countries – an update; 2012. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/20120905_GUI_HPV_vaccine_update.pdf

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidance on HPV vaccination in EU countries: focus on boys, people living with HIV and 9-valent HPV vaccine introduction; 2020. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Guidance-on-HPV-vaccination-in-EU-countries2020-03-30.pdf

- Takla A, Wichmann O, Carrillo-Santisteve P, et al. Characteristics and practices of national immunisation technical advisory groups in Europe and potential for collaboration, April 2014. Euro Surveill. 2015 Mar 5;20(9):21049.

- Nohynek H, Wichmann O, D’Ancona F, et al. National advisory groups and their role in immunization policy-making processes in European countries. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(12):1096–1105.

- Dorleans F, Giambi C, Dematte L, et al. The current state of introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination into national immunisation schedules in Europe: first results of the VENICE2 2010 survey. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(47):19730.

- Poljak M, Seme K, Maver PJ, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type-distribution, cervical cancer screening practices and current status of vaccination implementation in Central and Eastern Europe. Vaccine. 2013 Dec 31;31(Suppl 7):H59–70.

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, et al. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016 Jul;4(7):e453–63.

- World Health Organization. European vaccine action plan 2015–2020. Copenhagen, Denmark: Regional Office for Europe; 2014. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/255679/WHO_EVAP_UK_v30_WEBx.pdf

- Nguyen-Huu NH, Thilly N, Derrough T, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage, policies, and practical implementation across Europe. Vaccine. 2020 Feb 5;38(6):1315–1331.

- Elfstrom KM, Dillner J, Arnheim-Dahlstrom L. Organization and quality of HPV vaccination programs in Europe. Vaccine. 2015 Mar 30;33(14):1673–1681.

- Lefevere E, Theeten H, Hens N, et al. From non school-based, co-payment to school-based, free Human Papillomavirus vaccination in Flanders (Belgium): a retrospective cohort study describing vaccination coverage, age-specific coverage and socio-economic inequalities. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5188–5195.

- Ferrer HB, Trotter C, Hickman M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):700.

- Kessels SJ, Marshall HS, Watson M, et al. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30(24):3546–3556.

- Markowitz LE, Tsu V, Deeks SL, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine introduction–the first five years. Vaccine. 2012 Nov 20;30(Suppl 5):F139–48.

- World Health Organization. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem; 2020.