ABSTRACT

Introduction

As for other vaccines, vaccination hesitancy may be a determining factor in the success (or otherwise) of the COVID-19 immunization campaign in healthcare workers (HCWs).

Areas covered

To estimate the proportion of HCWs in Italy who expressed COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, we conducted a systematic review of the relevant literature and a meta-analysis. Determinants of vaccine compliance and options suggested by these studies to address vaccine hesitancy among HCWs were also analyzed. Seventeen studies were included in the meta-analysis and systematic review, selected from scientific articles available in the MEDLINE/PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus databases between 1 January 2020 and 25 January 2022. The vaccine hesitancy rate among HCWs was 13.1% (95%CI: 6.9–20.9%). The vaccine hesitancy rate among HCWs investigated before and during the vaccination campaign was 18.2% (95%CI = 12.8–24.2%) and 8.9% (95%CI = 3.4–16.6%), respectively. That main reasons for vaccine hesitation were lack of information about vaccination, opinion that the vaccine is unsafe, and fear of adverse events.

Expert opinion

Despite strategies to achieve a greater willingness to immunize in this category, mandatory vaccination appears to be one of the most important measures that can guarantee the protection of HCWs and the patients they care for.

1. Introduction

COVID-19, the infectious disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, was declared a pandemic in early 2020, having reached global proportions [Citation1]. To deal with the COVID-19 pandemic, a mass vaccination campaign was launched in European countries on 27 December 2020 [Citation2]. In Italy, the government opted to prioritize vaccination of healthcare workers (HCWs) (contextually to frail patients), a decision in line with the recommendations of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Citation3]. By providing critical care to patients who are or may be infected with SARS-CoV-2, HCWs are at high risk for exposure to the virus and thus the development of COVID-19; furthermore, vaccinating HCWs safeguards healthcare capacity [Citation2].

As with other vaccines, vaccine hesitancy can be a determining factor in the success (or otherwise) of the COVID-19 immunization campaign. In fact, in 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) listed vaccine hesitancy as a major health threat that year [Citation4]. Indeed, a 2022 narrative review [Citation5] COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy rates in 42/114 countries/territories worldwide ranged from 13% to 59%; this phenomenon appeared more pronounced in Africa, Europe, and Central Asia. Today, vaccine hesitancy is still a challenging health threat as it can compromise the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in the general population and subgroups, including health personnel.

Vaccination hesitancy among Italian HCWs is a topic already investigated in the literature; indeed, insufficient vaccination coverage in Italian health personnel is reported, considering other vaccine-preventable diseases recommended for the category [Citation6–8]. Factors explaining suboptimal vaccination attitudes among HCWs [Citation6–9] include misinformation, loss of confidence, fear of adverse effects, absence of educational campaigns, inaccurate risk perception, unknown or uncertain vaccination status and difficulties in accessing vaccination in the workplace.

To estimate the proportion of HCWs expressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Italy, we conducted a systematic review of the relevant literature and a meta-analysis. Determinants of vaccine compliance and options suggested by these studies to deal with vaccine hesitation among HCWs were also analyzed.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

The Scopus, MEDLINE/PubMed and Google Scholar databases (up to page 5) were systematically searched. Research articles, brief reports, reviews and meta-analyses published between 1 January 2019 and 25 January 2022 were included in our search. The following terms were used for the search strategy: (adherence OR hesitancy OR compliance OR attitude) AND (covid* OR SARS-CoV-2) AND (vaccin* OR immun*) AND (healthcare workers OR health personnel OR physician OR nurse OR doctor OR residents OR students) AND (Italy). Studies in English or Italian with full text were included. Abstracts without full text, letters to the editor not reporting original data, articles not reporting epidemiological data (editorials, commentaries, etc.) and all studies focusing on issues unrelated to the purpose of this review (vaccine knowledge, adverse vaccine reactions, etc.) were excluded. When necessary, study authors were contacted for additional information. References of all articles were reviewed for further study. The list of papers was independently screened by title and/or abstract by two reviewers who applied the predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were recorded and resolved by consensus.

Extracted data included year, sample size, number of hesitant HCWs, professional category, area of questionnaire administration, timing of the investigation (before or during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign), potential determinants of vaccine hesitancy, and options for managing hesitant HCWs.

2.2. Quality assessment

The quality of selected studies was assessed according to the STROBE checklist, which includes 22 methodological questions [Citation10]. Studies assessed according to STROBE had a minimum and maximum possible score of 0 and 44, respectively, and were classified as low quality (<15.5), moderate quality (15.5–29.5) or high quality (30–44).

The risk of bias for each study was independently assessed by two researchers. Discrepancies were recorded and resolved by consensus.

2.3. Pooled analysis

Three different meta-analysis groups were performed: the first included all HCWs, the second compared hesitancy according to different times of survey administration (before the vaccination campaign [1 February 2020–26 December 2020] vs. during the vaccination campaign [from 27 December 2020]) and the third by job category (HCWs, including residents vs. Medical School students). Sub-analysis by study quality was not possible because all studies were of high quality.

The pooled proportion in the meta-analysis was calculated using the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation to stabilize variances, and the DerSimonian-Laird weights for random effects models, with the estimate of heterogeneity obtained from the inverse-variance fixed-effects model. The pooled prevalence and the associated 95% Wald confidence interval were plotted, and a forest plot was drawn. The I2 statistic was calculated as a measure of the proportion of the overall variance attributable to heterogeneity between studies rather than to chance. Heterogeneity between studies in different groups was also assessed. A p-value<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance of the heterogeneity.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate stability; among the studies included in this systematic review, one study at a time was excluded, and the conclusion subsequently based on the others was then reevaluated to avoid severe distortions.

Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA MP17.

Strategies to increase vaccination compliance among HCWs and suggested strategies to address vaccine hesitancy were collected from all available studies and their respective findings were compared, with particular attention to the evidence presented in several of the included papers.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of relevant studies

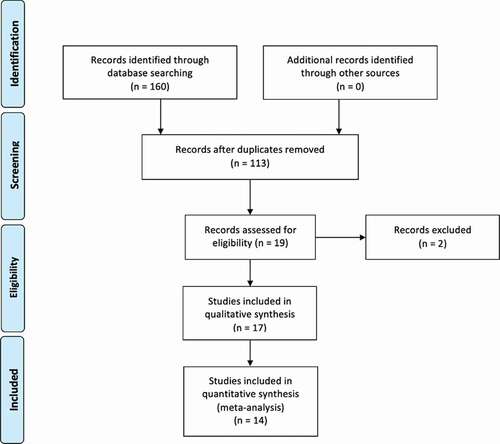

The flow-chart, constructed following the PRISMA guidance [Citation11] (), shows the process of article selection. According to the aforementioned inclusion criteria, 13 articles were identified in Google Scholar, 9 in Scopus, and 15 in MEDLINE/PubMed. After exclusion of duplicate articles in the two databases, there were 19 eligible studies [Citation12–30]. Of these, one [Citation29] was excluded because it evaluated the same phenomenon in a more recent, comprehensive article already included in the meta-analysis and another [Citation30] because additional information was requested from the authors but they did not respond. Thus, overall, 17 studies were eligible [Citation12–28], of which 14 were quantitative [Citation12–25] and three were qualitative [Citation26–28] (). The remaining 94 studies did not match the inclusion criteria [Citation27–114].

Table 1. Characteristics of the selected studies included in meta-analysis and systematic review.

3.2. Quality assessment

The STROBE checklist was applied appropriately to the included studies, and all were determined to be of high quality ().

3.3. Pooled analysis

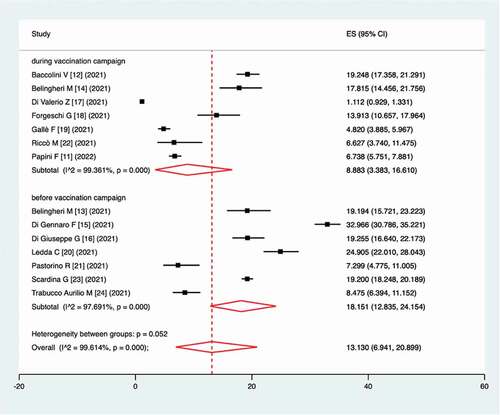

According to our meta-analysis, the prevalence of vaccine hesitancy among HCWs was 13.1% (95%CI: 6.9–20.9%), in accordance with an I2 of 99.6% and a p-value for the heterogeneity test of <0.0001. In a comparison of vaccine hesitancy according to different times of survey administration (before vs. during the vaccination campaign), the prevalence of vaccine hesitancy among HCWs investigated before and during the vaccination campaign was 18.2% (95%CI = 12.8–24.2%; I2 = 97.7%; p < 0.0001) and 8.9% (95%CI = 3.4–16.6%; I2 = 99.4%; p < 0.0001), respectively, according to a p value in the test of heterogeneity between sub-groups of 0.052 ().

Figure 2. Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of vaccine hesitancy as determined by the different timing of survey administration (before vs. during the vaccination campaign).

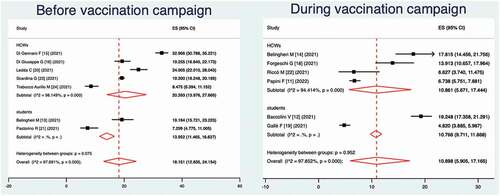

In a sub-analysis of vaccination hesitancy according to job category, the prevalence was 13.6% (95%CI = 5.8–24.1%; I2 = 99.7%; p < 0.0001) for HCWs and 9.5% (95%CI = 3.4–18.1%; I2 = 98.3%; p < 0.0001) for students, according to a p-value of 0.491 in the test of heterogeneity between sub-groups. Sub-analysis according to the different time of survey administration (before vs. during the vaccination campaign) is described in .

Figure 3. Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of vaccine hesitancy, by job category (HCWs, including residents vs. Medical School students) and as time of survey administration (before vs. during the vaccination campaign).

Sensitivity analysis showed no severe distortions from any specific study.

3.4. Determinants of vaccination compliance and suggested strategies to address vaccination hesitancy

All studies concluded that vaccination hesitation is a crucial issue in the management of COVID-19 pandemic. Many determinants of hesitancy have been investigated; most studies have reported that the main reasons are lack of information about vaccination, opinion that the vaccine is unsafe, and fear of adverse events [Citation14–17,Citation21,Citation23], with the exception of Trabucco Aurilio M et al. [Citation25] who did not identify safety concerns in their sample of nurses. Moreover, the role of pharmaceutical companies in influencing vaccine policy decisions and the uncertainty associated with the rapid development process of COVID-19 vaccines [Citation15–17,Citation23] were also determinants of the hesitation. Minor factors of a negative attitude toward the vaccine were fear of ineffectiveness due to virus mutations [Citation23], disagreement with vaccinations in general, the opinion that COVID-19 is not a threatening disease [Citation15] and lower trust in adenoviral vaccines amid reports of its association with thromboembolic events [Citation23]. A history of infection prior to vaccination [Citation13,Citation14,Citation20,Citation25] and a diagnosis among family members and friends [Citation15] did not appear to influence vaccination compliance nor hesitancy. Concern about COVID-19 disease-related risk is a determinant of better attitude, as reported by three studies [Citation12,Citation16,Citation17,Citation23], whereas for Bellingheri M et al. [Citation14] it did not influence willingness. HCWs reported that the safety and protection of themselves and their patients was one of the main reasons for vaccination uptake [Citation17,Citation21]; it was particularly important for individuals with comorbidities [Citation21], even though, as reported by Bellingheri M et al. [Citation15], some HCWs reported immune disorders and severe allergies as additional reasons for avoiding receiving COVID-19 vaccination. HCWs with higher education degree and information from scientific sources were associated with better acceptance [Citation17,Citation20,Citation21]; indeed, HCWs who used mass media or the Internet as their main source of information did not have significant benefit in their willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine in the future [Citation17]. Overall, the main determinant of vaccination compliance was having received previous vaccination, especially the anti-influenza vaccine [Citation12,Citation14–16,Citation18,Citation22,Citation25].

Regarding age, higher levels of compliance have been reported in young HCWs [Citation18,Citation21], even if Ledda C et al. [Citation21] reported low hesitancy in subjects older than 51 years. More discussed is the different approach to immunization between the sexes, with four studies [Citation12,Citation17,Citation20,Citation21] reporting better compliance in males and two [Citation13,Citation25] in females.

Physicians seemed to report less hesitancy, compared with other healthcare professionals [Citation12,Citation17,Citation24]; in particular, physicians employed in pediatrics, oncology, and geriatrics seemed more prone to have an accepting attitude toward vaccines (probably because of the characteristics of their patients) [Citation18]. In general, having worked in a COVID-19 ward increased compliance with vaccination [Citation18,Citation24]. Furthermore, as reported by Riccò M et al. [Citation23], health personnel identified vaccines as instrumental in coping with a series of significant issues that emerged during the first stage of the pandemic, i.e. the limited reliability of most Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), the limited utility of non-pharmacological interventions in healthcare settings, inappropriate risk perceptions among many healthcare professionals and awareness of the difficulty of tracing and tracking HCWs. Finally, as reported by Baccolini V et al. [Citation13], hesitancy to the COVID-19 vaccine has changed over time and in relation to several factors, including confidence in the efficacy and safety of the vaccine, perception of disease risk and education level. By identifying the factors that hinder vaccination, it will be possible to plan vaccination campaigns that can lead to overcome resistance on the part of health personnel [Citation19].

Regarding strategies to manage vaccine hesitancy among HCWs, many authors have proposed the urge to better educate health personnel and fight fake news [Citation12–15,Citation17,Citation18,Citation25,Citation28]; in fact, improving vaccine acceptance and information in HCWs can be doubly effective in the struggle against the pandemic, as they are employed on the frontlines and can be decisive in influencing the general population [Citation18].

On the other hand, the presence of a non-negligible number of HCWs who are opposed or undecided may compromise hospital health policies and jeopardize the safety of the fragile patients with whom they come into contact [Citation25], so several recent works have advocated mandatory vaccination, in response to a pressing social need to protect individual and public health, and above all as a defense of vulnerable subjects or patients [Citation12,Citation14,Citation23,Citation26,Citation28]. Health personnel themselves have expressed fair adherence to mandatory vaccination for health professional [Citation27]. In fact, knowledge of recommended vaccinations and acceptance rates of mandatory vaccinations increased significantly among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy [Citation21].

4. Conclusion

Our meta-analysis estimated vaccine hesitancy among HCWs in Italy to be 13% (95%CI = 7–21%), lower than the value reported in a 2021 scoping review (23%) [Citation114] that investigated vaccine hesitancy among HCWs worldwide. Moreover, our study showed that vaccine hesitancy decreased in the study set during the vaccination campaign, compared with those set before it (9% vs 18%); probably, evidence of vaccine safety, increased incidence of COVID-19 cases, and the example of other colleagues increased vaccine compliance, as also reported by Baccolini V et al. [Citation13].

Considering the occupational category, students appear to be slightly less hesitant than HCWs (9% vs. 14%). This difference is more pronounced in the subjects interviewed before the start of the vaccination campaign, with students showing a percentage of hesitancy equal to 14%, whereas for HCWs this was 20%; on the other hand, the subjects interviewed during the vaccination campaign expressed the same value of vaccination hesitancy (8%). Considering that, especially during the first lockdown, academic and internship activities were suspended [Citation115], Medical School students should have had less ‘on-the-ground’ awareness of COVID-related issues. On the contrary, HCWs experienced the concerns of nosocomial management, ward reorganization, awareness of being at risk for infection, awareness of the complications of COVID-19. Nevertheless, the data showed that despite this, HCWs were more hesitant than students of Medical School.

The systematic review showed the main determinants of vaccination hesitancy; lack of information about the vaccination, the opinion that the vaccine is not safe, and fear of adverse events are known determinants of vaccination refusal in the scientific literature; indeed, these data confirmed evidence already reported in the literature for other vaccinations [Citation6–8]. On the other hand, the role of pharmaceutical companies in influencing vaccination policy decisions and the incertitude associated with the rapid development process of COVID-19 as determinants of hesitation are pathognomonic of COVID-19 vaccination compared with other vaccines; such evidence, confirmed by other studies in the literature [Citation116], should be surprising considering that HCWs should be familiar with the mechanism of drug development and marketing.

History of disease or experience with it among family members and friends did not influence opinion about immunization, whereas fear of COVID-19 complications and the safety and protection of self and patients seemed to increase willingness to vaccinate. Higher education and scientific sources have played a fundamental role in the attitude of HCWs; indeed, it must be considered that older Italian HCWs (including nurses and auxiliary staff) often do not have a master degree. Trust in the scientific community has already been identified has a major determinant of vaccination compliance in the general population [Citation117,Citation118] and thus, also for health care workers has a main role. Then again, the role of social media and the internet in spreading misinformation, and thereby facilitating vaccine distrust, is well known [Citation119,Citation120].

In any case, one of the main determinants of vaccination adherence was having received a previous vaccination, particularly anti-influenza vaccine; this evidence had already been reported in the literature for other vaccinations [Citation71,Citation121], but it seems to be valid for COVID-19 vaccination as well [Citation114].

The relationship between age and willingness to vaccinate is already reported in the literature, especially regarding other vaccinations [Citation8]. Our systematic review did not clearly highlight the attitude to COVID-19 vaccination of Italian HCWs considering age class, but a scoping review in 2021 [Citation114] showed that older health personnel were more likely to accept COVID-19 vaccines, worldwide. Anyway, we can consider the professional category as a proxy for the age group and therefore our meta-analysis showed a better compliance in students (hence young subjects) especially before the beginning of the vaccination campaign; more studies are needed to evaluate this topic for Italian HCWs. The same issue is evidenced with regard to sex, with the scoping review mentioned above suggesting better compliance in male subjects [Citation114].

Regarding the professional category, physicians seem to be more prone to vaccination and this evidence is confirmed in the literature [Citation8,Citation122]; moreover, this topic has been well studied with regard to other vaccinations and many studies in the literature agree that a higher level of education and degree are associated with a better compliance to vaccination [Citation123,Citation124].

Having worked in a COVID-19 ward is another determinant of vaccination readiness, probably because those HCWs have seen COVID complications up close; furthermore, Italian HCWs at the beginning of the pandemic considered the availability of PPE inadequate [Citation125] and so, as also reported by Bianchi FP et al. [Citation126], the vaccine may be considered by HCWs as a type of PPE.

Education of HCWs and fighting fake news to combat vaccination hesitancy among HCWs are topics investigated in many studies in the literature [Citation127–134]; despite this, our systemic review revealed that mandatory anti-COVID-19 was desirable for both the authors of the studies and the interviewed HCWs themselves. Indeed, on 1 April 2021, the Italian Government issued the Decree Law no. 44 establishing compulsory COVID-19 vaccination for HCWs [Citation26].

The main limitation of this meta-analysis was the high heterogeneity across studies, as indicated by the I2 values. The reason of this high heterogeneity may be multiple. Indeed, one of the reasons is that the phenomenon was investigated among the HCWs of many Italian regions; moreover, the author investigated the ‘vaccine hesitancy’ using different definitions as reported in . Furthermore, the performed sensitivity analyses did not show an improving of heterogeneity values across studies. Anyway, the use of a random-effects analysis in statistical analysis minimized this bias; therefore, this does not appear to be a critical issue. It was also not possible to stratify susceptible HCWs on the basis of their previous illness, gender, age group, and job mansion. Another argument is that most surveys were administered online or on social media and thus it is possible that HCWs answered more than one questionnaire; this potential bias is unfortunately not detectable or correctable. However, a strength of our review and meta-analysis was the large sample size resulting from the collation of selected papers, which improved statistical analysis and provided a better view of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Italian HCWs. In addition, all studies were published from 2021, so this view is up-to-date and reliable. Finally, the meta-analysis showed a comparison of vaccine hesitancy before and during the vaccination campaign, not previously reported in the literature.

5. Expert opinion

Our study highlighted a moderate proportion of healthcare workers expressing hesitation in vaccination and the main determinants of vaccination compliance. Despite strategies to achieve greater immunization willingness in this category, a few months after the start of the vaccination campaign the Italian government opted for mandatory vaccination. This strategy, which has already proved successful with regard to other categories of the population [Citation135], appears to be the only one capable of guaranteeing the protection of HCWs and the patients they care for.

Vaccination resistance by healthcare professionals is a globally studied phenomenon [Citation31,Citation61,Citation74,Citation114], although it may seem counterintuitive. Therefore, even though education and training programs are essential, especially for HCWs with lower levels of education, they do not seem to be sufficient [Citation104]. Emergency situations require drastic measures such as mandatory vaccination; the obligation introduced in Italy, in fact, is based on fitness for work assessed by occupational health physicians, with suspension of salary until immunization [Citation28]. The impact of this law on immunization status has led to an increase in vaccination coverage with the elimination of the last resistance in health personnel. Paradoxically, however, hundreds of HCWs still reject the vaccine.

Vaccination of HCWs, especially in a pandemic context, is a vital measure from a public health perspective; in fact, it guarantees the protection of operators and patients (especially the most fragile ones), allows the safety of nosocomial structures and reduces absenteeism due to illness, ensuring a smooth service to citizens. Furthermore, HCWs are among the most trusted sources of vaccine information and have a direct influence on the vaccination decisions of their patients and social contacts [Citation136]. Indeed, the success of a vaccination campaign largely depends on the penetrance of the message addressed to general population, which takes on an even more strategic value when vaccine candidates suffer from chronic diseases [Citation137,Citation138]. This last point is of crucial importance in the fight against the pandemic and the return to normalcy.

On the other hand, the role of information sources, particularly social media, must also be questioned. Italy has already experienced the risk of vaccine campaign failure due to the uncontrolled dissemination of erroneous information by the media on two separate occasions (Fluad 2014, Vaxveria 2021) [Citation139,Citation140]. Although media content cannot be controlled, it must be taken into account that especially social platforms are the battlefield of Italian no-vax groups that, even if small in number, are very organized and able to circulate false news in a very short time [Citation140]. As reported by Paris C et al. [Citation141], media communication has a dramatic effect on vaccine hesitancy even in HCWs. This is precisely why it is appropriate for public health institutions to organize to ensure proper institutional and scientific communication, especially on social networks.

The presence of figures of high scientific depth on the mass and social media is fundamental in order to disseminate the most up-to-date scientific evidence and inform and educate the population [Citation142]. Scientific community must deal with this issue with a better willingness to communicate even the clinical studies to those people not able to understand the medical information autonomously. Experiences reported in Italy, such as that of the website ‘Vaccinarsi,’ indicate that during the pandemic there was a strong increase in views, concluding that combining disciplines such as health education and digital communication through Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) represents the best strategy to support citizens [Citation75]. At the same time, training experiences of health operators in digital communication and social networks knowledge are reported [Citation143].

Finally, the role of the Italian government should also be discussed. The decision of the obligation in health professionals (and subsequently in the over 50s) should have been explained more clearly and justified from a scientific point of view [Citation67]. Politicians should not be seduced by the vote pool of the no vax and anti-science community, but should rely on scientific evidence and educate the population to data-based decisions.

In conclusion, vaccination hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine among Italian health professionals is an existing phenomenon. In order to achieve a high vaccination coverage, mandatory vaccination was introduced, which resulted in an increase in vaccination uptake with the achievement of very high vaccination coverage. This strategy is successful and has already been tested with the flu vaccine in some Italian regions in previous years [Citation140], with interesting results [Citation144]. Potential susceptibility to vaccine-preventable diseases has been addressed many times by our research team [Citation8,Citation123,Citation145–154]; we must emphasize that even in the time of COVID-19, circulation of microbiological agents in nosocomial facilities is still possible. Therefore, our opinion is that the obligation of vaccination should be deeply considered by policymakers in order to extend to health professionals, especially those working in wards particularly at risk, even for other vaccine-preventable diseases. The effects of this mandatory strategy should be evaluated in terms of cost-efficacy and considering the medical-legal aspects, but at present we believe that it is the fastest solution to solve the problem of vaccination hesitation in healthcare personnel. At the same time, in the medium-long term, complementary strategies to increase vaccination compliance should be put in place, in order to reevaluate the attitude of the HCWs toward vaccination and possibly return to a non-mandatory strategy.

Article highlights

Vaccine hesitancy can be a determining factor in the success (or otherwise) of the COVID-19 immunization campaign

Vaccination hesitancy among Italian HCWs is a topic already investigated in the literature

Insufficient vaccination coverage is reported, considering other vaccine-preventable diseases recommended for the category

Our study estimated the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Italian HCWs (not currently available from institutional data), that was assessed around 13%.

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy decreased in the study set during the vaccination campaign, compared with those set before it (9% vs 18%)

The scenario of management strategies for hesitant individuals is very difficult

Our results highlight that vaccine hesitancy in healthcare professionals is a genuine public health concern in Italy

Mandatory vaccination seems to be a winning strategy to deal with low uptake

Author contributions

FPB and ST conceived the study. FPB and PS did the literature research. FPB did the meta-analysis. SL and AM participated in the design of the meta-analysis. NB supervised the meta-analysis. FPB and ST co-drafted the first version of the article.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19). [ Updated 2021 May 13; cited 2022 Jan 4]. Available From: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses

- Bianchi FP, Germinario CA, Migliore G, et al. Control Room Working Group. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a preliminary report. J Infect Dis.2021 Aug 2;224(3):431–434.

- CDC. The importance of COVID-19 vaccination for healthcare personnel. [ Updated Dec 14 2021; cited 2022 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/hcp.html

- World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health in 2019. [cited 2022 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

- Sallam M, Al-Sanafi M, Sallam M, et al. Map of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates per country: an updated concise narrative review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022 Jan 11;15:21–45.

- Squeri R, Di Pietro A, La Fauci V, et al. Healthcare workers’ vaccination at European and Italian level: a narrative review. Acta Biomed. 2019 Sep 13;90((9–S)):45–53.

- Barchitta M, Basile G, Lopalco PL, et al. Vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccination among Italian healthcare workers: a review of current literature. Future Microbiol. 2019 Jun;14:15–19.

- Bianchi FP, Vimercati L, Mansi F, et al. Compliance with immunization and a biological risk assessment of health care workers as part of an occupational health surveillance program: the experience of a university hospital in southern Italy. Am J Infect Control. 2020 Apr;48(4):368–374.

- Boccia S, Colamesta V, Grossi A, et al. Improving vaccination coverage among healthcare workers in Italy. Epidemiol Biostat Public Health. 2018. 15(3)

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

- Papini F, Mazzilli S, Paganini D, et al. Healthcare workers attitudes, practices and sources of information for COVID-19 vaccination: an Italian national survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 10;19(2):733.

- Baccolini V, Renzi E, Isonne C, et al. Vaccine hesitancy among Italian university students: a cross-sectional survey during the first months of the vaccination campaign. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Nov 7;9(11):1292.

- Belingheri M, Ausili D, Paladino ME, et al. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine and reasons for adherence or not among nursing students. J Prof Nurs. 2021 Sep-Oct;37(5):923–927.

- Belingheri M, Roncalli M, Riva MA, et al. vaccine hesitancy and reasons for or against adherence among dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021 Sep;152(9):740–746.

- Di Gennaro F, Murri R, Segala FV, et al. Attitudes towards Anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination among healthcare workers: results from a national survey in Italy. Viruses. 2021 Feb 26;13(3):371.

- Di Giuseppe G, Pelullo CP, Della Polla G, et al. Surveying willingness toward SARS-CoV-2 vaccination of healthcare workers in Italy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021 Jul;20(7):881–889.

- Di Valerio Z, Montalti M, Guaraldi F, et al. Trust of Italian healthcare professionals in covid-19 (anti-sars-cov-2) vaccination. Ann Ig. 2021 Aug 3;34:217–226.

- Forgeschi G, Cavallo G, Lorini C, et al. Investigating adherence to COVID-19 vaccination and serum antibody concentration among hospital Workers-The experience of an Italian private hospital. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Nov 16;9(11):1332.

- Gallè F, Sabella EA, Roma P, et al. Knowledge and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among undergraduate students from central and Southern Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jun 10;9(6):638.

- Ledda C, Costantino C, Cuccia M, et al. Attitudes of healthcare personnel towards vaccinations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Mar 8;18(5):2703.

- Pastorino R, Villani L, Mariani M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on flu and COVID-19 vaccination intentions among university students. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jan 20;9(2):70.

- Riccò M, Ferraro P, Peruzzi S, et al. Mandate or not mandate: knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Italian occupational physicians towards SARS-CoV-2 immunization at the beginning of vaccination campaign. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Aug 11;9(8):889.

- Scardina G, Ceccarelli L, Casigliani V, et al. Evaluation of flu vaccination coverage among healthcare workers during a 3 years’ study period and attitude towards influenza and potential COVID-19 vaccination in the context of the pandemic. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jul 9;9(7):769.

- Trabucco Aurilio M, Mennini FS, Gazzillo S, et al. Intention to be vaccinated for COVID-19 among Italian nurses during the pandemic. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 May 12;9(5):500.

- Vinceti SR. COVID-19 Compulsory vaccination of healthcare workers and the Italian constitution. Ann Ig. 2021 Oct;34(3): 207–216 .

- Craxì L, Casuccio A, Amodio E, et al. Who should get cOVID-19 vaccine first? A survey to evaluate hospital workers’ opinion. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Feb 25;9(3):189.

- Frati P, La Russa R, Di Fazio N, et al. Compulsory vaccination for healthcare workers in Italy for the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Aug 29;9(9):966.

- Monami M, Gori D, and Guaraldi F, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy and early adverse events reported in a cohort of 7,881 Italian physicians. Ann Ig. 2021 Nov;34(4):344–357.

- Barello S, Nania T, Dellafiore F, et al. ‘Vaccine hesitancy’ among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020 Aug;35(8):781–783.

- Shakeel CS, Mujeeb AA, Mirza MS, et al. Vaccine acceptance: a systematic review of associated social and behavioral factors. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Jan 12;10(1):110.

- Viola A, Muscianisi M, Voti RL, et al. Predictors of Covid-19 vaccination acceptance in IBD patients: a prospective study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec 1;33(1SSuppl 1):e1042–e1045.

- Sabbadin C, Betterle C, Scaroni C, et al. Frequently asked questions in patients with adrenal insufficiency in the time of COVID-19. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021 Dec 24;12:805647.

- Bianco A, Della Polla G, Angelillo S, et al. vaccine hesitancy: a cross-sectional survey in Italy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022 Jan;2:1–7.

- Luma AH, Haveen AH, Faiq BB, et al. Hesitancy towards Covid-19 vaccination among the healthcare workers in Iraqi Kurdistan. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2022. Jun. 3: 100222.

- Baccolini V, Renzi E, Isonne C, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Italian university students: a Cross-Sectional survey during the first months of the vaccination campaign. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(11):1292. Published 2021 Nov 7.

- Contoli B, Possenti V, Minardi V, et al. Is the willingness to receive vaccination against COVID-19 among the elderly in Italy? Data from the PASSI d’Argento surveillance system. Front Public Health. 2021 Nov 5;9:736976.

- Russo AG, Tunesi S, Consolazio D, et al. Evaluation of the anti-COVID-19 vaccination campaign in the metropolitan area of Milan (Lombardy Region, Northern Italy). Epidemiol Prev. 2021;45(6):568–579. English.

- Lecce M, Perrone PM, Bonalumi F, et al. 2020-21 Influenza vaccination campaign strategy as a model for the third COVID-19 vaccine dose? Acta Biomed. 2021 Oct 19;92(S6):e2021447.

- Guidry JPD, Perrin PB, Bol N, et al. Social distancing during COVID-19: threat and efficacy among university students in seven nations. Glob Health Promot. 2021 Oct;26:17579759211051368.

- D’Errico S, Zanon M, Concato M, et al. “First do no harm.” No-fault compensation program for COVID-19 vaccines as feasibility and wisdom of a policy instrument to mitigate vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Sep 30;9(10):1116.

- Scoccimarro D, Panichi L, Ragghianti B, et al. Sars-CoV2 vaccine hesitancy in Italy: a survey on subjects with diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2021 Oct 28;31(11):3243–3246.

- Bertoni L, Roncadori A, Gentili N, et al. How has COVID-19 pandemic changed flu vaccination attitudes among an Italian cancer center healthcare workers? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Oct;6:1–6.

- Bechini A, Zanella B, Bonito B, et al. Quality and safety of vaccines manufacturing: an online survey on attitudes and perceptions of Italian internet users. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Sep 13;9(9):1015.

- Freeman EE, Chamberlin GC, McMahon DE, et al. Dermatology COVID-19 Registries: updates and Future Directions. Dermatol Clin. 2021 Oct;39(4):575–585.

- Aricò E, Castiello L, Bracci L, et al. Antiviral and immunomodulatory interferon-beta in high-risk COVID-19 patients: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2021 Sep 3;22(1):584.

- Concas G, Barone M, Francavilla R, et al. Twelve months with COVID-19: what gastroenterologists need to know. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Jul;31:1–21.

- Del Riccio M, Boccalini S, Rigon L, et al. Factors influencing SARS-CoV-2 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in a population-based sample in Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jun 10;9(6):633.

- Flacco ME, Soldato G, Acuti Martellucci C, et al. Interim estimates of covid-19 vaccine effectiveness in a mass vaccination setting: data from an Italian province. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jun 10;9(6):628.

- Asadi Faezi N, Gholizadeh P, Sanogo M, et al. Peoples’ attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine, acceptance, and social trust among African and middle East countries. Health Promot Perspect. 2021 May 19;11(2):171–178.

- Perrone PM, Biganzoli G, Lecce M, et al. Influenza vaccination campaign during the COVID-19 pandemic: the experience of a research and teaching hospital in milan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 May 30;18(11):5874.

- Troiano G, Nardi A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health. 2021 May;194:245–251.

- Priori R, Pellegrino G, Colafrancesco S, et al. Response to: ‘correspondence on ‘SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy among patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: a message for rheumatologists” by Smerilli. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Oct;80(10):e169.

- Smerilli G, Cipolletta E, Moscioni E, et al. Correspondence on ‘SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy among patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: a message for rheumatologists.’ Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Oct;80(10):e168.

- Watanabe M, Balena A, Tuccinardi D, et al. Central obesity, smoking habit, and hypertension are associated with lower antibody titres in response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2022 Jan;38(1):e3465.

- Efficace F, Breccia M, Fazi P, et al. GIMEMA-ALLIANCE digital health platform for patients with hematologic malignancies in the COVID-19 pandemic and postpandemic era: protocol for a multicenter, prospective, observational study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021 Jun 1;10(6):e25271.

- Vitali M, Pironti P, Salvato D, et al. COVID-19 pandemic influence frozen shoulder outcomes? Rehabilitacion (Madr). 2021 Jul-Sep;55(3): 241.

- Di Pumpo M, Vetrugno G, Pascucci D, et al. COVID-19 a real incentive for flu vaccination? Let the numbers speak for themselves. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Mar 18;9(3):276.

- Maniaci A, Ferlito S, Bubbico L, et al. Comfort rules for face masks among healthcare workers during COVID-19 spread. Ann Ig. 2021 Nov-Dec;33(6):615–627.

- Crawshaw AF, Deal A, Rustage K, et al. What must be done to tackle vaccine hesitancy and barriers to COVID-19 vaccination in migrants? J Travel Med. 2021 Jun 1;28(4):taab048.

- Sallam M. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Feb 16;9(2):160.

- Damiani G, Allocco F, Malagoli P, Young Dermatologists Italian Network, Malagoli P. COVID-19 vaccination and patients with psoriasis under biologics: real-life evidence on safety and effectiveness from Italian vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021 Aug;46(6):1106–1108.

- Greenhawt M, Kimball S, DunnGalvin A, et al. Media influence on anxiety, health utility, and health beliefs early in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic-a survey study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021 May;36(5):1327–1337.

- Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Nov 20;11(11):CD006207.

- Odone A, Bucci D, Croci R, et al. Vaccine hesitancy in COVID-19 times. An update from Italy before flu season starts. Acta Biomed. 2020 Sep 7;91(3):e2020031.

- Nanni O, Viale P, Vertogen B, et al. A cluster-randomized study with hydroxychloroquine versus observational support for prevention or early-phase treatment of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020 Jul 31;21(1):689.

- Stefanizzi P, Bianchi FP, Brescia N, et al. Vaccination strategies between compulsion and incentives. The Italian green pass experience. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022 Jan;13:1–3.

- Valerio A, Nisoli E, Rossi AP, et al. Obesity and higher risk for severe complications of Covid-19: what to do when the two pandemics meet. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2020 Jun 29;27(S Pt 1):e31–e36.

- Papadopoulos NG, Custovic A, Deschildre A, et al., Pediatric Asthma in Real Life Collaborators. Impact of COVID-19 on pediatric asthma: practice adjustments and disease burden. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Sep;8(8:2592–2599.e3.

- Del Duca E, Chini L, Graziani S, et al. with the Italian Pediatric Immunology and Allergology Society (SIAIP) vaccine committee. Pediatric health care professionals’ vaccine knowledge, awareness and attitude: a survey within the Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. Ital J Pediatr. 2021 Sep 9;47(1):183.

- Di Giuseppe G, Pelullo CP, Paolantonio A, et al. Healthcare workers’ willingness to receive influenza vaccination in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey in Southern Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jul;9;9(7):766.

- Caserotti M, Girardi P, Rubaltelli E, et al. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc Sci Med. 2021 Mar;272:113688.

- Bechini A, Garamella G, Giammarco B, et al. Paediatric activities and adherence to vaccinations during the COVID-19 epidemic period in Tuscany, Italy: a survey of paediatricians. J Prev Med Hyg. 2020 Jul 4;61(2):E125–E129.

- Salomoni MG, Di Valerio Z, Gabrielli E, et al. Hesitant or not hesitant? A systematic review on global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in different populations. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Aug 6;9(8):873.

- Arghittu A, Dettori M, Dempsey E, et al. Health communication in COVID-19 era: experiences from the Italian VaccinarSì network websites. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 May 25;18(11):5642.

- Khan S, Gilani US, Raza SMM, et al. Knowledge, awareness and practices of Pakistani professionals amid-COVID-19 outbreak. Sci Rep. 2021 Sep 2;11(1):17543.

- Rahmani A, Dini G, Orsi A, et al. Reactogenicity of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a young working age population: a survey among medical school residents, within a mass vaccination campaign, in a regional reference teaching hospital in Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Nov 3;9(11):1269.

- Pedote PD, Termite S, Gigliobianco A, et al. Influenza vaccination and health outcomes in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective cohort study. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Apr 8;9(4):358.

- Antonelli-Incalzi R, Blasi F, Conversano M, et al. Manifesto on the value of adult immunization: “We Know, We Intend, We Advocate.” Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Oct 22;9(11):1232.

- The Lancet. COVID-19: learning as an interdependent world. Lancet. 2021 Sep 25;398(10306): 1105.

- Shemtob L, Ferris M, Asanati K, et al. Vaccinating healthcare workers against covid-19. BMJ. 2021 Aug;11(374):n1975.

- Della Polla G, Licata F, Angelillo S, et al. Characteristics of healthcare workers vaccinated against influenza in the era of COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jun 24;9(7):695.

- Keske Ş, Mutters NT, Tsioutis C, et al. EUCIC influenza vaccination survey team. Influenza vaccination among infection control teams: a EUCIC survey prior to COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine. 2020 Dec 14;38(52):8357–8361.

- Franchini M, Pieroni S, Martini N, et al. Shifting the paradigm: the Dress-COV telegram bot as a tool for participatory medicine. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Nov 26;17(23):8786.

- Quiros-Roldan E, Magro P, Carriero C, et al. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the continuum of care in a cohort of people living with HIV followed in a single center of Northern Italy. AIDS Res Ther. 2020 Oct 4;17(1):59.

- Dalla Volta A, Valcamonico F, Pedersini R, et al. The spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection among the medical oncology staff of ASST Spedali Civili of Brescia: efficacy of preventive measures. Front Oncol. 2020 Aug 18;10:1574.

- Della Polla G, Pelullo CP, Di Giuseppe G, et al. Changes in behaviors and attitudes in response to COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination in healthcare workers and university students in Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Nov 3;9(11):1276.

- Farì G, de Sire A, Giorgio V, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in a cohort of Italian rehabilitation healthcare workers. J Med Virol. 2022 Jan;94(1):110–118.

- Hajure M, Tariku M, Bekele F, et al. Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers: a systematic review. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:3883–3897. Published 2021 Sep 21.

- Riad A, Pokorná A, Antalová N, et al. Drivers of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Czech university students: national Cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Aug 25;9(9):948.

- Saied SM, Saied EM, Kabbash IA, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J Med Virol. 2021 Jul;93(7):4280–4291.

- Mant M, Aslemand A, Prine A, et al. University students’ perspectives, planned uptake, and hesitancy regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study. PLoS One. 2021 Aug 3;16(8):e0255447.

- Aw J, Seng JJB, Seah SSY, et al. Vaccine hesitancy-A scoping review of literature in high-income countries. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Aug 13;9(8):900.

- Gerussi V, Peghin M, Palese A, et al. Vaccine hesitancy among Italian patients recovered from COVID-19 infection towards Influenza and SARS-Cov-2 vaccination. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Feb 18;9(2):172.

- Chew NWS, Cheong C, Kong G, et al. An Asia-Pacific study on healthcare workers’ perceptions of, and willingness to receive, the COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2021 May;106:52–60.

- Javier PF, Ramón DG, Ana EG, et al. Attitude towards vaccination among health science students before the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jun 12;9(6):644.

- Li M, Luo Y, Watson R, et al. Healthcare workers’ (HCWs) attitudes and related factors towards COVID-19 vaccination: a rapid systematic review. Postgrad Med J. 2021 Jun 30; postgradmedj-2021-140195. DOI:10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140195.

- Riad A, Abdulqader H, Morgado M, et al. Drivers of dental students’ COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 May 29;9(6):566.

- Biswas MR, Alzubaidi MS, Shah U, et al. Review to find out worldwide COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its underlying determinants. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Oct 25;9(11):1243.

- Cascini F, Pantovic A, Al-Ajlouni Y, et al. Attitudes, acceptance and hesitancy among the general population worldwide to receive the COVID-19 vaccines and their contributing factors: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2021 Oct;40:101113.

- Riad A, Huang Y, Abdulqader H, et al. Iads-Score. Universal predictors of dental students’ attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination: machine learning-based approach. Vaccines (Basel).2021 Oct 10;9(10):1158.

- Bai W, Cai H, Liu S, et al. Attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines in Chinese college students. Int J Biol Sci. 2021 10; 176:1469–1475. Published 2021 Apr.

- Di Martino G, Di Giovanni P, Di Girolamo A, et al. Attitude towards vaccination among healthcare workers: a multicenter cross-sectional study in a Southern Italian Region. Vaccines (Basel). 2020 May 24;8(2):248.

- Brunelli L, Antinolfi F, Malacarne F, et al. Range of strategies to Cope with healthcare workers’ vaccine hesitancy in A North-Eastern Italian Region: are they enough? Healthcare (Basel). 2020 Dec 23;9(1):4.

- Costantino C, Ledda C, Squeri R, et al. Perception of healthcare workers concerning influenza vaccination during the 2019/2020 season: a survey of Sicilian University Hospitals. Vaccines (Basel). 2020 Nov 16;8(4):686.

- Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance is correlated with conspiracy beliefs among university students in Jordan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Mar 1;18(5):2407.

- Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, et al. Approach for managing COVID-19: the importance of understanding the motivational roots of vaccination hesitancy for SARS-CoV2. Front Psychol. 2020 Oct 19;11:575950.

- Graffigna G, Palamenghi L, Boccia S, et al. ‘Relationship between citizens’ health engagement and intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine in Italy: a mediation analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2020 Oct 1;8(4):576.

- Mustapha T, Khubchandani J, Biswas N. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in students and trainees of healthcare professions: a global assessment and call for action. 2021;Brain Behav Immun Health. 16:100289.

- Eguia H, Vinciarelli F, Bosque-Prous M, et al. Hesitation at the gates of a COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Feb 18;9(2):170.

- Gallè F, Sabella EA, Roma P, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination in the elderly: a cross-sectional study in Southern Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Oct 21;9(11):1222.

- Townsel C, Moniz MH, Wagner AL, et al. vaccine hesitancy among reproductive-aged female tier 1A healthcare workers in a United States Medical Center. J Perinatol. 2021 Oct;41(10):2549–2551.

- Reno C, Maietti E, Fantini MP, et al. COVID-19 vaccines acceptance: results from a survey on vaccine hesitancy in Northern Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Apr 13;9(4):378.

- Biswas N, Mustapha T, Khubchandani J, et al. The nature and extent of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in healthcare workers. J Community Health. 2021 Dec;46(6):1244–1251.

- Cupertino F, Spataro S, Spinelli G, et al. The university as a safe environment during the SARS-COV-2 pandemic: the experience of Bari Politecnico. Ann Ig. 2021 Mar-Apr;33(2):201–202.

- Dzieciolowska S, Hamel D, Gadio S, et al. Covid-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and refusal among Canadian healthcare workers: a multicenter survey. Am J Infect Control. 2021 Sep;49(9):1152–1157.

- Sturgis P, Brunton-Smith I, Jackson J. Trust in science, social consensus and vaccine confidence. Nat Hum Behav. 2021 Nov;5(11):1528–1534.

- Cadeddu C, Sapienza M, Castagna C, et al. Trust in the scientific community in Italy: comparative analysis from two recent surveys. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Oct 19;9(10):1206.

- Muric G, Wu Y, Ferrara E. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy on social media: building a public Twitter data set of antivaccine content, vaccine misinformation, and conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021 Nov 17;7(11):e30642.

- Hernandez RG, Hagen L, Walker K, et al. COVID-19 vaccine social media infodemic: healthcare providers’ missed dose in addressing misinformation and vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Sep 2;17(9):2962–2964.

- Hall CM, Northam H, Webster A, et al. Determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination hesitancy among healthcare personnel: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2021 Oct;29.

- Lee JT, Althomsons SP, Wu H, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination coverage among health care personnel working in long-term care facilities, by job category, National Healthcare Safety Network - United States, March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Jul 30;70(30):1036–1039.

- Bianchi FP, Tafuri S, Spinelli G, et al. Two years of on-site influenza vaccination strategy in an Italian university hospital: main results and lessons learned. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Nov;4:1–6.

- Antinolfi F, Battistella C, Brunelli L, et al. Absences from work among healthcare workers: are they related to influenza shot adherence? BMC Health Serv Res. 2020 Aug 18;20(1):763.

- Felice C, Di Tanna GL, Zanus G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on healthcare workers in Italy: results from a National E-Survey. J Community Health. 2020 Aug;45(4):675–683.

- Bianchi FP, Tafuri S, Migliore G, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptomatic disease in five-month follow-up: a retrospective cohort study. Vaccines (Basel).2021 Oct 7;9(10):1143.

- Dib F, Mayaud P, Chauvin P, et al. Online mis/disinformation and vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19: why we need an eHealth literacy revolution. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Feb;24:1–3.

- Wilson SL, Wiysonge C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob Health. 2020 Oct;5(10):e004206.

- Carrieri V, Madio L, Principe F. Vaccine hesitancy and (fake) news: quasi-experimental evidence from Italy. Health Econ. 2019 Nov;28(11):1377–1382.

- Possenti V, Luzi AM, Colucci A, et al. Communication and basic health counselling skills to tackle vaccine hesitancy. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2019 Apr-Jun;55(2):195–199.

- Langiano E, Ferrara M, De Vito E. La formazione del personale sanitario in ambito vaccinale [Training on vaccination for health care professionals]. Ig Sanita Pubbl. 2017 Sep-Oct;73(5):497–505.

- Biasio LR, Carducci A, Fara GM, et al. Health literacy, emotionality, scientific evidence: elements of an effective communication in public health. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018 Jun 3;14(6):1515–1516.

- Schumacher S, Salmanton-García J, Cornely OA, et al. Increasing influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers: a review on campaign strategies and their effect. Infection. 2021 Jun;49(3):387–399.

- Tognetto A, Zorzoli E, Franco E, et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination among health-care workers: the impact of different tailored programs in four University hospitals in Rome. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(1):81–85.

- Sindoni A, Baccolini V, Adamo G, et al. Effect of the mandatory vaccination law on measles and rubella incidence and vaccination coverage in Italy (2013-2019). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Aug;4:1–10.

- Giambi C, Fabiani M, D’Ancona F, et al. Parental vaccine hesitancy in Italy - Results from a national survey. Vaccine. 2018 Feb 1;36(6):779–787.

- Campanati A, Martina E, Diotallevi F, et al. How to fight SARS-COV-2 vaccine hesitancy in patients suffering from chronic and immune-mediated skin disease: four general rules. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Nov 2;17(11):4105–4107.

- Diotallevi F, Campanati A, Radi G, et al. Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 in psoriasis patients on immunosuppressive therapy: implications of vaccination nationwide campaign on clinical practice in Italy. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021 Dec;11(6):1889–1903.

- Signorelli C, Odone A, Conversano M, et al. Deaths after Fluad flu vaccine and the epidemic of panic in Italy. BMJ. 2015 Jan;14(350):h116.

- Bianchi FP, Tafuri S. A public health perspective on the responsibility of mass media for the outcome of the anti-COVID-19 vaccination campaign: the AstraZeneca case. Ann Ig. 2022 Feb 3.

- Paris C, Bénézit F, Geslin M, et al. vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Infect Dis Now. 2021 Aug;51(5): 484–487.

- Fontaine G, Maheu-Cadotte MA, Lavallée A, et al. Communicating science in the digital and social media ecosystem: scoping review and typology of strategies used by health scientists. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2019 Sep 3;5(3):e14447.

- Odone A, Gianfredi V, Sorbello S, et al. The use of digital technologies to support vaccination programmes in Europe: state of the art and best practices from experts’ interviews. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(10):1126. Published 2021 Oct 3.

- Genovese C, La Fauci V, Costa GB, et al. A potential outbreak of measles and chickenpox among healthcare workers in a university hospital. Euromediterranean Biomed J. 2019;14(10): 045–048

- Di Lorenzo A, Tafuri S, Martinelli A, et al. Could mandatory vaccination increase coverage in health-care workers? The experience of Bari Policlinico General Hospital. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Nov;30:1–2.

- Bianchi FP, Tafuri S, Larocca AMV, et al. -term persistence of antibodies against varicella in fully immunized healthcare workers: an Italian retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021 May 25;21(1):475.

- Bianchi FP, Larocca AMV, Bozzi A, et al. Long-term persistence of poliovirus neutralizing antibodies in the era of polio elimination: an Italian retrospective cohort study. Vaccine. 2021 May 21;39(22):2989–2994.

- Bianchi FP, Mascipinto S, Stefanizzi P, et al. Long-term immunogenicity after measles vaccine vs. wild infection: an Italian retrospective cohort study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Jul 3;17(7):2078–2084.

- Bianchi FP, Mascipinto S, Stefanizzi P, et al. Prevalence and management of measles susceptibility in healthcare workers in Italy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020 Jul;19(7):611–620.

- Bianchi FP, De Nitto S, Stefanizzi P, et al. Long time persistence of antibodies against Mumps in fully MMR immunized young adults: an Italian retrospective cohort study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020 Nov 1;16(11):2649–2655.

- Bianchi FP, De Nitto S, Stefanizzi P, et al. Immunity to rubella: an Italian retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2019 Nov 8;19(1):1490.

- Bianchi FP, Stefanizzi P, De Nitto S, et al. Immunogenicity of measles vaccine: an Italian retrospective cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2020 Feb 18;221(5):721–728.

- Vimercati L, Bianchi FP, Mansi F, et al. Influenza vaccination in health-care workers: an evaluation of an on-site vaccination strategy to increase vaccination uptake in HCWs of a South Italy Hospital. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(12):2927–2932.

- Bianchi FP, Gallone MS, Gallone MF, et al. HBV seroprevalence after 25 years of universal mass vaccination and management of non-responders to the anti-Hepatitis B vaccine: an Italian study among medical students. J Viral Hepat. 2019 Jan;26(1):136–144.