ABSTRACT

Introduction

Immunization is the best strategy to protect individuals from invasive meningococcal disease (IMD). To support decision-making around immunization, this paper considers what has led four countries and regions of two more to introduce the quadrivalent MenACWY vaccine in toddlers (ages 12–24 months).

Areas covered

A narrative literature review was conducted to identify countries that have introduced a MenACWY vaccination program for toddlers. Information from peer-reviewed publications, reports, and policy documents for each identified country was extracted. Australia, Chile, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and regions of Italy and Spain have introduced the MenACWY vaccine in their toddler programs, driven by the rising incidence of MenW and MenY and the vaccine’s ability to provide protection against other serogroups. Australia and the Netherlands considered the economic impacts of implementing a MenACWY toddler vaccination program. Vaccination uptake and effects are reported for three countries; however, in two, isolating the vaccine’s effect from the collateral effect of COVID-related measures is difficult.

Expert opinion

Increased convergence of vaccination policies and programs is needed internationally, as IMD recognizes no borders.

PL AIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Vaccination is the best defense against meningitis, a deadly disease. While someone of any age can contract it, children 0–24 months of age are disproportionately affected. The increasing number of cases of meningitis has led four countries plus regions of two more to introduce into their vaccination schedules for toddlers (ages 12–24 months) a vaccine that protects against four different serogroups rather than one serogroup alone. This paper considers what has driven that shift.

1. Background

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is a major cause of meningitis and septicemia, both serious and life-threatening illnesses. The number of global meningitis cases increased from 2.50 million (95% CI 2.19–2.91) in 1990 to 2.82 million (2.46–3.31) in 2016 [Citation1]. Incidence rates vary greatly across regions, with the highest rates reported in Northern Africa across the so-called African meningitis belt, where individual countries have reported rates up to 1,000/100,000 inhabitants [Citation2]. While any age group can be affected, infants (0–12 months) and toddlers (12–24 months) constitute the highest proportion of IMD cases, with the majority of cases caused by the A, B, C, W, and Y serogroups (the ratio of cases caused by the individual serogroups varies by geographical region and time) [Citation3,Citation4]. Beyond children, adolescents and young adults are also more affected than other age groups [Citation3,Citation4].

If IMD is untreated, fatality rates can reach up to 50% [Citation5]. Many organisms can cause meningitis, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites; of these, bacterial meningitis is of particular concern [Citation5]; the median fatality rate for bacterial meningitis, even when treated, is estimated at 14.4% [Citation6]. Studies have shown that lifelong sequelae can occur in childhood survivors, such as deafness and a need for amputation, that severely impact the lives of patients and their families [Citation7,Citation8]. Moreover, IMD presents a high cost burden to healthcare systems and society due to the direct impact of the disease, the management of outbreaks, and the costs of long-term care for chronic complications [Citation9–11]. Immunization with monovalent meningococcal vaccines (primarily MenC) provides insufficient protection against IMD because various meningococcal serogroups other than C circulate unpredictably, and several are prevalent simultaneously. There are vaccines on the market that allow for coverage against several serogroups. Currently, there are four vaccines available on the market that have been added to the World Health Organization’s prequalified list of vaccines [Citation12].

In the example of the UK, serogroup W levels rose sharply between from 2009 to 2014 [Citation4,Citation13]. In 2014, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization (JCVI) – the official body that advises UK health departments on immunization – advised adopting the MenACWY conjugate vaccine [Citation14]. The following year, a new MenACWY vaccination program was introduced in adolescents in the UK: firstly, through a temporary meningococcal ‘freshers’ vaccination program targeting students attending university for the first time; and secondly, through a permanent vaccination program in schools (school year 9 or 10). In both cases, a MenACWY vaccination program replaced the existing MenC vaccination program [Citation4]. Following the anticipated withdrawal of the conjugate Haemophilus type b (Hib) and MenC vaccine in toddlers (Menitorix®) from the market, the JCVI in their February 2020 meeting discussed introducing separate vaccines to cover Hib and MenC in that age group [Citation15]. This is an opportunity to ensure that the increased protection afforded by a quadrivalent MenACWY vaccine is available at 12 months of age within the national immunization program. Indeed, the JCVI has identified MenACWY vaccination as a ‘future proof’ option compared with the monovalent MenC vaccine because it provides improved resilience against the unpredictable emergence of virulent serogroups in the future [Citation15].

The UK is not the only country revising its meningococcal vaccination strategy [Citation2]. Australia, Chile, the Netherlands, and several regions of Italy and Spain have already introduced the MenACWY vaccine in their toddler schedules. Moreover, Switzerland introduced the MenACWY vaccine in children at 24 months of age.

This review focuses on toddlers due to the high incidence and high burden of the disease in this age group and the subsequent recent changes in toddlers’ vaccination programs. It analyzes the rationale behind the introduction of a MenACWY vaccination program or shift from the monovalent MenC vaccine to the quadrivalent MenACWY vaccine in four countries and several regions of two more and highlights common drivers. We will focus on:

The epidemiology of meningococcal disease in the countries discussed here and the vaccine strategy of each prior to the introduction of the MenACWY vaccine.

The policies and rationale that informed the implementation of the change to understand which cohorts were chosen and why.

The reported and expected epidemiological outcomes of the change.

2. Methods

A narrative literature review [Citation16] was conducted to identify countries that have introduced nationally or regionally a quadrivalent MenACWY vaccination program for toddlers (12–23 months of age) or young children (24 months of age, as for Switzerland). Relevant information from reviews, scientific articles, policy documents, and other publications for each identified country was extracted. Countries that introduced the vaccine in infants with a booster in toddlers, such as Argentina, or due to pilgrimage, such as Saudi Arabia, were excluded from the literature review due to the difference of target population.

Germany and France, neither of which included MenACWY vaccination for toddlers in their schedules but have reviewed or are currently assessing this possibility [Citation17,Citation18], were included only in the analysis of the incidence of cases to provide a clearer regional epidemiological perspective and partially analyzed in the discussion to provide additional learnings. However, the focus of this review is on countries that introduced MenACWY vaccination in toddlers.

3. Results

3.1. Countries

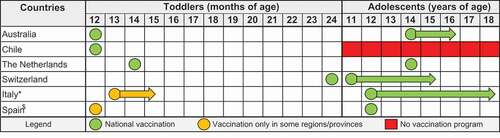

Australia, Chile, the Netherlands, and several regions of Italy and Spain have introduced the quadrivalent MenACWY vaccine in their toddler programs. Switzerland introduced the vaccine in children 24 months old. In addition, five out of these six countries have also introduced a quadrivalent MenACWY vaccination for adolescents. The recommendations for both the toddler and the adolescent age groups are listed in .

Figure 1. Recommended age at MenACWY vaccination. * In Italy, vaccination in toddlers is strongly recommended by the national medical associations in the 2019 Calendario Vaccinale per la Vita; the recommendations have already been adopted in at least 8 of the 21 regions/autonomous provinces. Recently, the Italian authorities have also considered the introduction of an additional vaccination for children at 6 years of age. $ In Spain, toddler vaccination is present in only two regions, Castilla y León and Andalucía.

3.1.1. Australia

In Australia, the quadrivalent MenACWY vaccination program has been funded for all toddlers at 12 months of age since 2018, replacing the MenC component of the combined Hib (PRP-T) and MenC vaccination [Citation19]. The authors of the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) MenACWY vaccine assessment state that introducing the vaccine would allow for budget benefits because of cost minimization in comparison with other vaccines against meningococcal disease and increased coverage for strains not covered under the current vaccination regimen [Citation20].

3.1.2. Chile

Chile was the first country to introduce routine MenACWY vaccination for toddlers when MenW incidence started to rise steeply in the late 2000s, particularly among children below the age of 5 [Citation21]. Mandatory vaccination at 12 months was introduced in 2014 by the Ministry of Health after a pilot vaccination project launched in 2012 targeting infants, toddlers, and young children (from 9 months to 5 years) in the most affected regions proved successful in reducing cases [Citation22]. Before the introduction of the MenACWY vaccine, no vaccination program against IMD existed [Citation21].

3.1.3. The Netherlands

In Europe, the Netherlands was the first country to introduce MenACWY vaccination in toddlers, in 2018, including an economic analysis in its assessment [Citation23]. The Netherlands’ Health Council (Gezondheidsraad) recommended the MenACWY vaccine for the toddler age group because of an increase in MenW cases, the MenACWY vaccine’s safety profile, its favorable risk-benefit and cost-efficacious profile (despite being slightly higher than the commonly used reference value of €20,000 per quality-adjusted life year [QALY]) [Citation23]. In the same year, the Health Council also recommended the MenACWY vaccine for adolescents starting at the age of 14 [Citation24].

3.1.4. Switzerland

In Switzerland, the Federal Commission for Vaccine Issues (Eidgenössische Kommission für Impffragen) updated its recommendations in 2018: instead of administering MenC vaccination at 12–15 months and a booster in adolescence, the commission recommended MenACWY conjugate vaccination at 24 months, because no MenACWY vaccine is licensed in Switzerland for children below 2 years of age, and an adolescent booster [Citation25]. Direct and indirect protection provided by the vaccine in toddlers and epidemiological trends of MenW cases primarily led to this recommendation [Citation26].

3.1.5. Italy

In Italy, the National Vaccination Plan (Piano Nazionale Prevenzione Vaccinale) 2017–2019 recommended MenACWY conjugate vaccination only in adolescents [Citation27]. However, because the immunization recommendations made by the Vaccination Calendar for Life (Calendario Vaccinale per la Vita) [Citation28] published by the major pediatric associations (PAs) in 2019 strongly endorsed full adoption of MenACWY vaccination in toddlers, many of the 21 regions in Italy have either started following the PAs’ advice and offer quadrivalent vaccination for toddlers (at either 13 or 24 months) and for adolescents in their reimbursement plan [Citation29–36] or offer the vaccine with a copayment [Citation37]. Some regions included the vaccine in their regional recommendations well before 2019; for example, the Apulia region recommended it in 2017 [Citation36]. The main reasons stated by the major PAs were the increase in MenW cases in Europe and better protection against additional serogroups [Citation28]. In line with these reasons, in 2021 an Italian health technology assessment document supported the extension of MenACWY vaccination to a cohort of 6-year-old children and a cohort of young adults [Citation38].

3.1.6. Spain

Since 2019, the national Spanish guidelines have recommended the quadrivalent vaccine in adolescents [Citation39]; in some regions, the vaccine is also recommended for toddlers. The regions of Castilla y León [Citation40] and Andalucía [Citation41] have replaced the MenC vaccine at 12 months and 12 years with the MenACWY vaccine, primarily due to recent increases in MenW and MenY cases. In 2021, the Vaccine Advisory Committee of the Spanish Association of Pediatrics (Comité Asesor de Vacunas de la Asociación Española de Pediatría) supported this change, with the goal of making an epidemiologically significant impact quickly [Citation42].

3.2. Incidence and mortality of IMD before the introduction of the quadrivalent vaccine

Before the introduction of the quadrivalent vaccine, the six countries described above, except Italy, reported a high incidence of IMD and MenW IMD. The standardized incidence of IMD reported from 2010 to 2016 was low in Italy compared with Spain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland (). However, it is important to mention that cases are systemically underreported in Italy due to limited testing capacity [Citation43].

Figure 2. Standardized incidence (cases per 100,000) of IMD (all serogroups) by country [Citation21,Citation25,Citation44].

![Figure 2. Standardized incidence (cases per 100,000) of IMD (all serogroups) by country [Citation21,Citation25,Citation44].](/cms/asset/efcf3e43-f425-4fe3-b632-8c1b3c4fd860/ierv_a_2128771_f0002_oc.jpg)

Whereas most countries under review reported a decline in IMD due to a decreasing number of serogroup B and C incidence rates (the latter mostly due to the implementation of MenC vaccination programs) [Citation42], there was a notable increase in the incidence of IMD caused by serogroup W (). For comparison, include the incidence of three European countries, which have not (yet) introduced the quadrivalent vaccine in toddlers: Germany, France, and the UK. Germany reported a minor increase in MenW cases from 0.0135 in 2015 to 0.0316 in 2016 cases per 100,000 inhabitants; the rate remained stable at 0.03 throughout 2017 and 2018 [Citation44]. France experienced a substantial increase in MenW cases from 2016 (0.068) to 2017 (0.11) and onwards [Citation44]. Among these three countries, the steepest increase in MenW cases was registered in the UK, where the rate per 100,000 inhabitants went from 0.039 in 2010 to 0.273 in 2018, peaking at 0.361 in 2016 [Citation44].

Figure 3. Standardized incidence (cases per 100,000) of IMD cases due to serogroup W by country [Citation21,Citation25,Citation44].

![Figure 3. Standardized incidence (cases per 100,000) of IMD cases due to serogroup W by country [Citation21,Citation25,Citation44].](/cms/asset/d88b3717-e7f3-4f4b-885a-6252f40ebcd6/ierv_a_2128771_f0003_oc.jpg)

Notably, the introduction of MenACWY vaccine for toddlers in Chile in 2014 led to a drastic reduction in both overall IMD cases () and MenW cases (), from 0.8 to 0.4 and from 0.55 to 0.2, respectively [Citation21].

3.3. Reasons for introduction

Although several arguments have been made for the introduction of the quadrivalent vaccine in national or regional immunization programs (see for an overview by country), the main argument by all countries has been the rising incidence of MenW (and partially MenY) in infants, toddlers, and adolescents. All countries reviewed here stated that direct protection from the high mortality and morbidity of IMD during periods of high incidence drove their policy update (see ).

Table 1. Summary of reasons for the introduction of MenACWY vaccine in toddlers.

MenW is more aggressive than other serogroups and can lead to septic shock and/or fatality over the course of a few hours. For this reason, early diagnosis of the disease is critical and makes direct protection from the disease all the more important [Citation45]. At the same time, some countries, such as Switzerland, argued that the vaccination of toddlers also provides indirect protection to other age groups; the protection can be extended into adulthood by a booster dose given during adolescence [Citation26]. In addition, Australia and Italy explicitly cite an additional benefit resulting from broader serogroup coverage of MenACWY due to the unpredictable epidemiology [Citation28,Citation46].

Australia and the Netherlands are the only countries in our review that cited economic reasons for the introduction of MenACWY vaccination. In Australia, a change from MenC to MenACWY vaccination in toddlers was considered to be cost-neutral. For adolescents, however, the Australian PBS considered the cost/QALY of the MenACWY vaccine to be above the threshold of 15,000 Australian dollars (AUD)/QALY (~8,215 British pounds [GBP]) compared with current MenC vaccination and advised reducing the price of the vaccine [Citation20]. In the Netherlands, the cost-effectiveness of MenACWY vaccination was slightly higher than the threshold (20,000 EUR, ~17,140 GBP) compared with current MenC vaccination; however, the Gezondheidsraad concluded that the vaccine nonetheless provided a benefit given the severity of IMD [Citation23]. On top of cost-effectiveness reasons, it is worth considering the possible positive socioeconomic impact of a MenACWY vaccination program in toddlers in terms of health equity. Low household income and social deprivation of the municipality of residence are recognized risk factors for IMD hospitalization, particularly in children of preschool age (≤4 years) [Citation47]. Therefore, a MenAWCY vaccination program in toddlers might be an effective way to protect children and to promote social equity in the population.

Moreover, the Andalucía region in Spain supported the introduction of MenACWY vaccination in toddlers based on the intrinsic difficulties of achieving high vaccine coverage quickly in adolescents [Citation41]. Thus, Andalusian authorities expect that a toddler vaccination program would allow for quicker population coverage [Citation41].

3.4. Effects of vaccination programs

In Australia, authorities registered a dramatic decrease in IMD cases per 100,000 from 1.1 in 2018 to 0.3 in 2020. A similar decrease is visible also in the proportion of isolates attributable to MenW and MenY. In particular, the proportion of MenW cases over all IMD cases decreased from 38% in 2018 to 18% in 2020. The decrease in IMD cases is coincident both with widespread public health initiatives designed to reduce COVID-19 transmission and with changes in the immunization program [Citation48], such as the introduction of the MenACWY vaccine in toddlers (as demonstrated from the decrease in the proportion of MenW cases).

In Chile, MenW incidence in toddlers and young children (from 12 months to 4 years of age) declined from 1.3/100,000 in 2012 to 0.1/100,000 in 2016, a 92.3% reduction after vaccination implementation. Any indirect effects of vaccination have not yet been observed [Citation21]. Indeed, the reactive MenACWY vaccination implemented in Chile in children aged 9 months to 5 years had an impact only on this age group. Chile’s approach (particularly the 2012 targeted vaccination program) has been successful in this age group, as no further cases due to serogroup W have been identified in this vaccinated cohort [Citation49].

In the Netherlands, MenW cases are declining after the introduction of MenAWCY vaccination in 2018: 62 cases with serogroup W were reported in 2019 and 12 cases in 2020 as compared with 102 cases in 2018. Of note, the low number of cases in 2020 was likely due in part to the measures against COVID-19 [Citation50]. A recent publication shows that the new MenACWY vaccination program was effective in preventing IMD-W in the target population in the Netherlands. From 2014 to 2020, MenW incidence rate lowered by 61%, with a decrease of 82% in vaccine-eligible age group (15- to 36-month olds and 14- to 18-year olds) and of 57% in vaccine non-eligible age groups. Moreover, vaccine effectiveness was 92% against IMD-W vaccine-eligible toddlers [Citation51].

Overall, given the recent introduction of the vaccine in many countries and the recent public health measures put in place due to the Covid-19 pandemic, it is rather early and difficult to evaluate the full impact of MenACWY immunization in most countries, including Australia and the Netherlands, with the exception of Chile.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings of this study

The main reason for introducing a vaccination program or switching from MenC to MenACWY vaccination in the countries discussed here is the increase in IMD and MenW IMD incidence: apart from Italy, all countries that have introduced the quadrivalent vaccine had reported a high incidence of both overall IMD and MenW IMD cases and increasing case numbers. Since IMD is systemically underreported in Italy because of limited testing capacity [Citation43], local Italian authorities may be addressing the suspected higher number of overall and MenW IMD incidence by introducing the quadrivalent vaccine. In addition, periodic increases in MenY cases have been observed in Europe [Citation18,Citation52]. It is important to recognize and address the unpredictability of the changing epidemiology of IMD cases.

Following the introduction of MenACWY vaccination, Chile has seen a steep decline in cases. In the coming years, we expect to see similar results in Europe and Australia. Switching from MenC to MenACWY vaccine might lead to limited additional costs for the healthcare system, as demonstrated by the economic analysis carried out in the Netherlands [Citation23]. Replacing the Hib/MenC vaccine with separate Hib and MenACWY vaccines would be cost-neutral, as seen in Australia [Citation20].

It is important to highlight the impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic on meningococcal vaccination rates as well as the incidence of IMD. A good example is France, where, on one hand, the first lockdown led to a reduction in vaccination catch-up, and a persistent shortfall in infant Men C vaccination booster at 12 months was registered after the first 10 months of the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation53]. On the other hand, IMD cases due to hyperinvasive isolates decreased during the lockdown [Citation54]. Such trends were seen also in other countries [Citation55].

In the UK, the delivery of MenACWY vaccine in 2020 into school immunization programs was interrupted from 20 March 2020, following UK government COVID-19 guidance [Citation56]. This had a significant impact on the uptake of MenACWY vaccination program in the 2019–2020 academic year. The MenACWY vaccine coverage rate among adolescents 14 years old in 2019–2020 was 58.3% compared with 88.0% in 2018–2019 and 86.2% in 2017–2018 [Citation57]. The lower vaccination rates among adolescents could risk indirect protection for the wider population.

The lower vaccination rates as well as the lower incidence of IMD cases may predict reduced immunity in the population with possible rebound of IMD once constraint measures are ended. Thus, MenACWY vaccination in toddlers may represent an essential addition to the routine adolescent immunization program to promote herd protection against IMD and, in particular, MenW.

4.2. What is already known on this topic

Several recent studies have reviewed IMD vaccination policies. Epidemiological trends and the availability of new vaccines have led many authors to assess the current status of IMD vaccination policies around the globe. In particular, Booy et al. (2019) found that many countries affected by an increase in MenW cases enhanced surveillance to monitor meningococcal disease and that an increasing number of countries have implemented vaccination campaigns to prevent MenW in infants, toddlers, and/or adolescents [Citation58]. Presa et al. (2019) reviewed MenACWY vaccine studies that span multiple age groups and found that the MenACWY vaccine generally demonstrated similar tolerability and immunogenicity in comparison with other meningococcal vaccines and with concomitant administration of other routine vaccines. The authors argue that continual updates to meningococcal vaccine recommendations in response to changing epidemiology, as have been undertaken for MenW, are necessary to promote optimal population protection [Citation59]. Finally, Taha et al. (2020) review the epidemiological trends and the vaccination policies in France with an eye to Europe. The authors concluded that it is time to consider not only national epidemiology but also trends in the region, and in this regard, they claim that an increase of group W cases encourages switching from the MenC to the MenACWY vaccine in both toddlers and adolescents across Europe [Citation18].

4.3. What this study adds

This study draws conclusions from countries that have already introduced the quadrivalent vaccine and can provide guidance to decision-makers in similar scenarios. To draw a comparison with MenC vaccine, the evidence shows that countries that introduced routine MenC vaccination had decreasing trends in numbers of IMD cases; this was not the case for countries without routine MenC vaccination [Citation60,Citation61]. Overall, given the global mobility of IMD, aligning vaccine practices seems advisable given the regional and cross-national epidemiological scenario. This study provides an overview of the evidence and the reasons that led several countries or regions of countries to implement the MenACWY vaccine in toddlers.

4.4. Limitations of this study

The narrative review methodology allowed the authors to identify the reasons that led the identified countries to introduce the MenACWY vaccine in toddlers through a review of a mix of published studies and policy documents that provide a clear overview of the processes that led to the introduction of the vaccine. However, a systematic review of published evidence coupled with semi-structured interviews with policymakers might provide information not captured in this study.

5. Conclusion

The rising incidence of MenW cases globally has led several countries to update their vaccination recommendations by introducing the quadrivalent conjugate vaccine, MenACWY, which allows for broader protection. The vaccine was first introduced in adolescents; however, some countries or regions of countries introduced or extended coverage to toddlers. The reasons for introducing the MenACWY vaccine in toddlers are primarily epidemiological. The rising incidence of MenW cases and MenY cases in some countries, coupled with the vaccine’s ability to provide protection against several serogroups in high-incidence patient groups, was mentioned across all the six countries analyzed. Some countries also considered economic reasons when evaluating the new vaccination program. MenACWY vaccination in toddlers does not seem to offer indirect protection to other age groups, such as adolescents and young adults, which are often responsible for carriage. Therefore, some countries like Australia, Italy, and the Netherlands introduced MenACWY vaccination in adolescents to provide direct as well as indirect protection.

The introduction of the MenACWY vaccination in toddlers in Chile in 2012 (pilot) and 2014 (nationally) led to a steep reduction in cases; similar outcomes are expected for Europe and Australia. The introduction of the MenACWY vaccine in toddlers is currently being discussed in many countries, including the UK. Here, in addition to MenW epidemiological trends, the recent COVID-19 pandemic severely affected vaccination strategies, which might have severe consequences for the incidence of many infectious diseases, including IMD.

This might be an opportunity to future-proof the national immunization schedule by increasing protection through a quadrivalent MenACWY vaccine available at 12 months of age, as the countries analyzed in this review decided to do.

6. Expert opinion

This study aimed to draw conclusions from countries that have introduced a MenACWY quadrivalent vaccine in toddlers and can provide guidance to decision-makers in other countries.

The rise in incidence of MenW and MenY, which are often not covered under current vaccination strategies, is the leading reason for countries to rethink and update their vaccination schedules. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic and the related public health measures implemented across the globe have had a substantial impact on both vaccination rates and infectious disease outbreaks, which may predict reduced immunity in the population and a possible rebound of IMD cases in the future. Therefore, several countries including the UK are currently revising their meningococcal vaccination strategy.

This review found that epidemiological reasons, primarily the rise of MenW and MenY cases, and the need for direct protection in age groups with high incidence (infants, toddlers, adolescents) are the major factors driving decisions. However, both the reasons considered and decisions taken are often limited to country borders and do not reflect broader regional trends. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to adopt comprehensive and converging evidence-based vaccination policies that are not limited by current political borders. Two out of the six countries analyzed in this review included economic factors, such as budget impact or cost-effectiveness analyses, in their decision-making processes. Economic assessments might be key drivers in countries with more economic-driven decision-making processes, such as the UK.

Therefore, there is a great need for future research that focuses on analyzing real-word clinical and economic data from countries that have introduced the MenACWY vaccine in toddlers. This review identifies some clinical evidence on the impact of the vaccine on the incidence of IMD coming from Chile (the first of the countries to introduce the MenACWY vaccine in toddlers), the Netherlands, and Australia. However, more evidence is expected in the near future.

Moreover, there is a need for research analyzing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and related public health measures on vaccination uptakes and disease outbreaks, as well as research on perceptions and hesitancy toward new vaccination policies. This research will be key in understanding how to implement new vaccination measures most effectively and efficiently across different population groups.

Ultimately, this review calls for an update that analyzes recent policy developments with regard to IMD vaccination strategies across the globe, including countries that did not introduce MenACWY vaccination in toddlers and countries that are considering or would need to replace MenC vaccination with MenACWY vaccination in toddlers. Other review updates should also include newly published studies that report on either clinical or economic evidence, as well as information on current policies for reimbursement and access to MenACWY vaccines across countries.

These research topics will be key to constructing ‘future-proofed’ vaccination strategies for IMD and other infectious diseases. In the future, toddler MenACWY vaccination might become an integral part of vaccination programs across a number of countries; and in some cases, we will witness a shift from current MenC vaccination schemes to MenACWY vaccination schemes in toddlers, as currently discussed in the UK.

It is to be hoped that there will be an increased convergence of vaccination policies and programs internationally or at least at the regional level, as IMD recognizes no borders. Finally, future vaccination policies and programs will need to put increased emphasis on the integration of evidence on vaccination perception and hesitancy in decision-making processes. The COVID-19 pandemic has left little room for interpretation on this matter.

Article highlights

This paper considers what has led four countries plus regions of two more to introduce the quadrivalent MenACWY vaccine in toddlers (ages 12–24 months) and in some cases shift from the monovalent MenC vaccine to the quadrivalent MenACWY.

The countries/regions discussed have taken the rising incidence of MenW and MenY cases as an opportunity to future-proof their national immunization schedule by increasing protection through a quadrivalent MenACWY vaccine available at 12 months of age.

This study is based on a narrative literature review of peer-reviewed articles and governmental reports and policy documents.

Declaration of interest

C Valmas and H Rashid are full-time employees of Sanofi, 410 Thames Valley Park Drive, Reading, Berkshire, RG6 1PT, UK. Emanuele Arcà and Marja Hensen are paid employees of Pharmerit International, an OPEN Health Company, which was contracted by Sanofi to support data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or material discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium for their review work. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

CV: Conception, analysis of data, revision of manuscript, final approval, acceptance of responsibility for contents of manuscript

EA: Conception, analysis of data, drafting and revising the manuscript, final approval, acceptance of responsibility for contents of the manuscript

MH: Conception, analysis of data, drafting and revising the manuscript, final approval, acceptance of responsibility for contents of the manuscript

HR: Conception, analysis of data, revision of manuscript, final approval, acceptance of responsibility for contents of manuscript

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Muhamed-Kheir Taha (Invasive Bacterial Infections Unit and the National Reference Centre for Meningococci and Haemophilus influenzae, Paris, France) for his contribution to the discussion. We also thank Katharina Verleger (Real World Evidence and Systemic Consultant, Berlin, Germany) for her contribution to the collection and analysis of data and Christina DuVernay (OPEN Health, Bethesda, Maryland, US) for editorial support.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zunt JR, Kassebaum NJ, Blake N, GBD 2016 Meningitis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of meningitis, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Dec;17(12):1061–1082.

- Parikh SR, Campbell H, Bettinger JA, et al. The everchanging epidemiology of meningococcal disease worldwide and the potential for prevention through vaccination. J Infect. 2020 Oct;81(4):483–498.

- Gobin M, Hughes G, Foulkes S, et al. The epidemiology and management of clusters of invasive meningococcal disease in England, 2010–15. J Public Health. 2020;42(1):e58–e65.

- Public Health England. Invasive meningococcal disease in England: annual laboratory confirmed reports for epidemiological year 2018 to 2019 2019.

- World Health Organization. Meningococcal meningitis 2018 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningococcal-meningitis

- World Health Organization. Defeating meningitis 2030: baseline situation analysis. 20 February 2019 [Cited 2022 Jul 20] Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/defeating-meningitis-2030-baseline-situation-analysis

- Borg J, Christie D, Coen PG, et al. Outcomes of meningococcal disease in adolescence: prospective, matched-cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):e502–e509.

- Viner RM, Booy R, Johnson H, et al. Outcomes of invasive meningococcal serogroup B disease in children and adolescents (MOSAIC): a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(9):774–783.

- Wright C, Wordsworth R, Glennie L. Counting the cost of meningococcal disease. Paediatr Drugs. 2013;15(1):49–58.

- Scholz S, Koerber F, Meszaros K, et al. The cost-of-illness for invasive meningococcal disease caused by serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis (MenB) in Germany. Vaccine. 2019;37(12):1692–1701.

- Anonychuk A, Woo G, Vyse A, et al. The cost and public health burden of invasive meningococcal disease outbreaks: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(7):563–576.

- World Health Organization. Prequalified vaccines [ Cited 19 July 2022]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/vaccines/prequalified-vaccines?field_vaccines_effective_date%5Bdate%5D=&field_vaccines_effective_date_1%5Bdate%5D=&field_vaccines_type%5B%5D=Meningococcal+ACYW-135+%28conjugate+vaccine%29&field_vaccines_name=&search_api_views_fulltext=&field_vaccines_number_of_doses=

- Public Health England. Meningococcal ACWY vaccination programme: information for healthcare practitioners. 2015 [updated Jun 2020; cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/menacwy-programme-information-for-healthcare-professionals

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. Minute[s] of the meeting on 1 October 2014 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://app.box.com/s/iddfb4ppwkmtjusir2tc/file/229171787772

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. Minute[s] of the meeting held on 04 and 05 February 2020 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://app.box.com/s/iddfb4ppwkmtjusir2tc/file/636396626894

- Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006 August;5(3):101–117.

- Koch-Institut R. Meningokokken, invasive Erkrankungen (Neisseria meningitidis) 2021 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Merkblaetter/Ratgeber_Meningokokken.html

- Taha M-K, Gaudelus J, Deghmane A-E, et al. Recent changes of invasive meningococcal disease in France: arguments to revise the vaccination strategy in view of those of other countries. Hum Vaccine Immunother. 2020;16(10):2518–2523.

- National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance. Significant events in meningococcal vaccination practice in Australia 2020 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2021-02/Meningococcal-history-Feb%202021.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. 5.06 Meningococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine serogroups A, C, W-135 and Y, Pre-filled syringe, 0.5mL, Nimenrix ®, Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd. 2018 [Cited 2022 Jul 5]. Available from: https://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-03/files/men-acwy-vaccine-infants-psd-march-2018.pdf

- Villena R, Valenzuela MT, Bastias M, et al. Meningococcal invasive disease by serogroup W and use of ACWY conjugate vaccines as control strategy in Chile. Vaccine. 2019 Oct 31;37(46):6915–6921.

- Ministerio de Salud. Decreto 1201 exento modifica decreto n° 6, de 2010, que dispone vacunación obligatoria contra enfermedades inmunoprevenibles de la población del país 2013 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1056598

- Gezondheidsraad. Vaccinatie tegen meningokokken 2018 [updated 2018 Dec 19; cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/documenten/adviezen/2018/12/19/vaccinatie-tegen-meningokokken

- Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu. Meningococcal ACWY 2018 [updated 2020 Sept 4; cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.rivm.nl/en/meningococcal-acwy

- Bundesamt für Gesundheit. Invasive Meningokokkenerkrankungen 2007–2016. BAG-Bulletin 5 vom 29. January 2018. [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.infovac.ch/docs/public/neisseria/1-invasive-meningokokkenerkrankungen-2007-2016.pdf

- Bundesamt für Gesundheit. Anpassungen der Impfempfehlungen zum Schutz vor invasiven Meningokokken-Erkrankungen: bundesamt für Gesundheit; 2018 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/mt/i-und-b/richtlinien-empfehlungen/neue-empfehlungen-2019/impfempfehlung-meningokokken-anpassung.pdf.download.pdf/impfempfehlung-meningokokken-anpassung-de.pdf

- Ministero della Salute. Piano Nazionale Prevenzione Vaccinale. PNPV 2017-2019 2017 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf

- Società Italiana di Pediatria. Calendario Vaccinale per la Vita 2019 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: http://www.igienistionline.it/docs/2019/21cvplv.pdf

- Azienda Provinciale per i Servizi Sanitari. Calendario provinciale delle vaccinazioni dell’infanzia e dell’adolescenza 2019 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.vaccinarsintrentino.org/assets/uploads/files/9/calendario-provinciale-delle-vaccinazioni.pdf

- Regione del Veneto. Meningococco ACWY Coniugato 2019 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://salute.regione.veneto.it/mobilevac/Malattie/Dettaglio?Id=MNACWYCO

- Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia. Aggiornamento dell’ Offerta Vaccinale per Infanzia e Adolescenza nella Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia 2019 2018 [updated 2018 Dec 21; cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.regione.fvg.it/rafvg/export/sites/default/RAFVG/salute-sociale/promozione-salute-prevenzione/FOGLIA5/allegati/Allegato_1_alla_Delibera_2425-2018.pdf

- Emilia-Romagna R Il calendario vaccinale pediatrico 2019 [ updated 10 December 2019; cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://salute.regione.emilia-romagna.it/sanita-pubblica/vaccinazioni/vaccinazioni-per-target-diversi/vaccinazioni-per-bambini-e-adolescenti/il-calendario-vaccinale-pediatrico

- Regione Marche. Il Calendario vaccinale 2018 [updated 2018 Nov 8; cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.vaccinarsinellemarche.org/vaccinazioni-marche/calendario-vaccinale

- Regione Puglia. Calendario vaccinale per la vita 2019 [ updated 2 August 2019; cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.vaccinarsinpuglia.org/notizie/2019/08/calendario-vaccinale-per-la-vita-2019-le-nuove-proposte-del-board

- Regione Sicilia. Calendario vaccinale per la Vita della Regione Sicilia 2019 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.vaccinarsinsicilia.org/assets/uploads/files/9/calendario-vaccinale-sicilia-2019.pdf

- Regione Puglia. Approvato il nuovo calendario vaccinale per la vita 2017 della Regione Puglia 2017 [updated 2017 Dec 20; cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.sanita.puglia.it/archivio-news_det/-/journal_content/56/20182/approvato-il-nuovo-calendario-vaccinale-per-la-vita-2017-della-regione-puglia

- Regione Liguria. Calendario vaccinale della Regione Liguria - Marzo 2017 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.vaccinarsinliguria.org/assets/uploads/files/9/Calendario_vaccinale_Liguria_2017.pdf

- Boccalini SPD, Mennini FS, Marcellusi A, et al. Health Technology Assessment (HTA) sull’introduzione di coorti aggiuntive per la vaccinazione contro il meningococco con vaccini quadrivalenti coniugati in Italia. J Prev Med Hyg. 2021;62(suppl. 1):E1–E128.

- Ministerio de Saludad. Vacunas y Programa de Vacunación 2021 [updated 2021 Jan 31; cited 2022 Jul 20. Available from: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/vacunas/profesionales/enfMeningococicaInvasiva.htm

- Junta de Castilla y Leòn. Instruccion conjunta de 9 de Julio de 2020 de la direccion general de salud publica y de la direccion general del planificacion y asistencia sanitaria sobre la vacunacion de rescate al meningococo ACWY en adolescentes y jovenes. 2020 [Cited 2022 Jul 20. Available from: https://www.saludcastillayleon.es/profesionales/en/vacunaciones/vacunacion-frente-meningococo-acwy-adolescentes-jovenes.files/1647434-INSTRUCCI%C3%93N%20CONJUNTA%20DGP_DGPAS%20VACUNACI%C3%93N%20DE%20RESCATE%20MENINGOCOCO%20ACSY%20EN%20ADOLESCENTES%20Y%20J%C3%93VENES.pdf

- Junta DA. Consejería de Salud y Familias. Meningococo C - ACWY 2020 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/saludyfamilias/areas/salud-vida/vacunas/paginas/menc.html

- Alvarez Garcia FJ, Cilleruelo Ortega MJ, Alvarez Aldean J, et al. [Immunisation schedule of the Pediatric Spanish Association: 2021 recommendations]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2021 Jan;94(1):53e1–53 e10.

- Azzari C, Nieddu F, Moriondo M, et al. Underestimation of invasive meningococcal disease in Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Mar;22(3):469–475.

- ECDC. Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases for Invasive Bacterial Diseases (2018 data): invasive H. influenzae disease, invasive meningococcal disease and invasive pneumococcal disease 2020 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx?Dataset=27&HealthTopic=36

- Mustapha MM, Marsh JW, Harrison LH. Global epidemiology of capsular group W meningococcal disease (1970-2015): multifocal emergence and persistence of hypervirulent sequence type (ST)-11 clonal complex. Vaccine. 2016 Mar 18;34(13):1515–1523.

- Taha MK, Deghmane AE, Antignac A, et al. The duality of virulence and transmissibility in Neisseria meningitidis. Trends Microbiol. 2002 Aug;10(8):376–382.

- Taha M-K, Weil-Olivier C, Bouée S, et al. Risk factors for invasive meningococcal disease: a retrospective analysis of the French national public health insurance database. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(6):1858–1866.

- Lahra MM, Robert George CR, Shoushtari M, et al. Australian Meningococcal Surveillance Programme Annual Report, 2020. 45. 2021 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/5C71FABF639650F6CA2586520081286B/$File/australian_meningococcal_surveillance_programme_annual_report_2020.pdf

- Map S, O’Ryan M, Bravo MTV, et al. The current situation of meningococcal disease in Latin America and updated Global Meningococcal Initiative (GMI) recommendations. Vaccine. 2015;33(48):6529–6536.

- Rijksinstituut foor Bolksgezondheid en Milieu. Stand van zaken meningokokkenziekte serogroep W 2021 [Cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.rivm.nl/meningokokken/toename-meningokokkenziekte-serogroep-w-sinds-oktober-2015

- Ohm M, Sjm H, van der Ende A, et al. Vaccine impact and effectiveness of meningococcal serogroup ACWY conjugate vaccine implementation in the Netherlands: a nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis. 2022 Jul 6;74(12):2173-2180.

- Bröker M, Jacobsson S, Kuusi M, et al. Meningococcal serogroup Y emergence in Europe: update 2011. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012 Dec 1;8(12):1907–1911.

- Taine M, Offredo L, Drouin J, et al. Mandatory infant vaccinations in France during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. In: Front Pediatr. 2021 May 28;9:666848.

- Taha M-K, Deghmane A-E. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown on invasive meningococcal disease. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):1–6.

- Brueggemann AB, Mjj VR, Shaw D, et al. Changes in the incidence of invasive disease due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis during the COVID-19 pandemic in 26 countries and territories in the Invasive Respiratory Infection Surveillance Initiative: a prospective analysis of surveillance data. Lancet Digital Health. 2021;3(6):e360–e370.

- Department for Education. Schools, colleges and early years settings to close. 18 May 2020 [Cited 20 July 2022]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/schools-colleges-and-early-years-settings-to-close

- Public Health England. Meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) vaccine coverage for the NHS adolescent vaccination programme in England, academic year 2019 to 2020. 2021.

- Booy R, Gentile A, Nissen M, et al. Recent changes in the epidemiology of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup W across the world, current vaccination policy choices and possible future strategies. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(2):470–480.

- Presa J, Findlow J, Vojicic J, et al. Epidemiologic trends, global shifts in meningococcal vaccination guidelines, and data supporting the use of MenACWY-TT vaccine: a review. Infect Dis Therap. 2019;8(3):307–333.

- Hong E, Barret AS, Terrade A, et al. Clonal replacement and expansion among invasive meningococcal isolates of serogroup W in France. J Infect. 2018 Feb;76(2):149–158.

- Whittaker R, Dias JG, Ramliden M, et al. The epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease in EU/EEA countries, 2004-2014. Vaccine. 2017 Apr 11;35(16):2034–2041.