ABSTRACT

Enhancing urban heritage can benefit the local community, but development has a negative impact on both the landscape and the social environment. The Viñales Valley (Cuba) is a priority hub of tourism development where ecotourism and cultural tourism have rapidly increased. The lack of hotel accommodation has contributed to the growth of room rental in private houses in Viñales, a protected world heritage landscape. The aim of this study is to determine the impact of home stay tourism on Viñales, both in physical terms (modifications to housing and the urban landscape) and in social terms (the changes and ‘benefits and losses’ perceived by the owners/hosts of the homes available for rent). The inventory we made detected 392 rental homes and we interviewed 74 landlords. The most clearly negative results are that renting out accommodation for tourists is the direct cause of the reduction in urban green spaces, the use of new building materials or the emergence of modern architectural structures. In social terms, the management of tourist activity is principally shouldered by women, leads to changes to daily habits and transforms the home into a work space. Finally, this activity causes social problems because of the emergence of social differences.

Introduction, aims, and methodology

In addition to sun and beach tourism, a new type of tourism has emerged in recent years, which focuses on the relation between tourists, the land and its residents. These tourists are more concerned with getting something out of their experience, are committed to the environment, seek authenticity and are interested in the cultural, historical, and ecological values of their destination. Tourists are motivated by a desire to see and experience life as it is really lived and seek to do so by entering into contact with the local population (MacCannell, Citation1973). This kind of tourism can be named community-based tourism (CBT) and its aim is to boost rural development, in both developed and developing countries. CBT is a form of tourism closely related to nature, culture and local customs and is designed to attract tourists eager for authentic experiences, improve community development, alleviate poverty and allow the conservation of natural and cultural resources (Samsudin & Maliki, Citation2015).

The Viñales Valley is an inland destination in Cuba with exceptional natural and cultural resources, which have been afforded various forms of official protection. In turn, this natural and cultural heritage attracts tourists from far and wide. In this way, tourism development has been linked to these values and the economic evolution of Cuba. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the consequent loss of its economic support caused a severe economic crisis that the Cuban State decided to counteract by strengthening the sugar, biotechnological and tourist sectors (Reid-Henry, Citation2007). In relation to tourism, those responsible for economic policy promoted the participation of the private sector, as complementary to the public sector, through people working on a self-employed basis and renting out their homes. According to Echarri, Cisneros, Robert, and Perera (Citation2019), the right to be self-employed dates back all the way to 1978 with the publication of Decree-Law No.14 ‘On the execution of self-employed working activities,’ which was subsequently derogated by Decree-Law No. 141/93 (Council of State, Citation1993). After this, the Decree-Law No. 171 of 15 May 1997 on ‘Renting of Residences, Rooms or Spaces’ authorised homeowners to rent out

residences, rooms, with or without their own bathroom facilities, and other spaces regarded as an integral part of the residence, at a freely agreed price and after registration with the authorities of the municipality in which the residence is located. (Council of State, Citation1997, art. 74: not paginated)

During those years, tourist demand has increased and part of it has been taken care of by renting out ‘casas particulares’ (literally, private houses, guesthouse type accommodation that rent rooms to Cubans or foreigners). This type of renting falls within the scope of ‘Home stay’: accommodation in which guests pay to spend the night and interact with the family who generally lives in the same home (Alonso, Citation2012; Galbreath, Citation2017; Ismail, Hanafiah, Aminuddin, & Mustafa, Citation2016; Jamaludin, Othman, & Awang, Citation2012; Lynch, Citation2005). Rebecca Ogden (Citation2019) analyses travel guides for Cuba and found that, in relation to accommodation in private houses, ‘The rough guide to Cuba’ by McAuslan and Norman (Citation2009) stated that this was ‘an ideal way to get a good impression of the country and its people’. Furthermore, they agree that private houses allow tourists to have a ‘more authentic experience’ by sharing the home and the private spaces of a ‘real’ Cuban family, as opposed to the ‘inauthenticity’ offered by traditional hotels and tourist resorts.

To get an authentic experience, the tourist must move from the recreated tourist scene, the ‘front,’ to the real rear space, the ‘back’ (Goffman, Citation1959, quoted in MacCannell, Citation1973). In terms of physical space, this is experienced in the homes of the local people. The home becomes a place of work and the members of the family become hosts to tourists who want to live the experience of cohabiting with an ‘authentic’ Cuban family. The relationship established between host and guest is influenced by the commercial exchange and it is the host who needs to ensure that the customer is comfortable, satisfied and enjoys their stay. This unusual relationship established between the host/entrepreneur and the guest/customer is related to the concept of ‘emotional labour’ coined by Hochschild (Citation1983, p. 7): ‘the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display’. Its principal objective is to influence the customer’s experience so that they are aware of the quality of the service and evaluate it positively (Hochschild, Citation1983; Molina Rodríguez, Citation2017).

In the case of Viñales, the town has a considerable number of ‘casas particulares’ that rent out rooms – many of which are protected – and, in fact, the total number of rooms on offer is higher than the number offered by hotels (Álvarez, Citation2009). Reconciling the patrimony in Viñales and its society with the development of tourism is a challenge that must be risen to if the town's cultural significance is to be maintained. In fact, if UNESCO is to continue to protect the area, Viñales must safeguard the integrity and singularity of its patrimony.

Given these circumstances, that is, (1) the increase in the number of ‘casas particulares’ due to the policies of the public administration and public interest, (2) the transformation of these homes into businesses and of their owners into entrepreneurs and (3) the need to protect the cultural and natural heritage, the basis of touristic activity and of the ‘authentic’ experience of the tourist, it is necessary to understand and evaluate the current situation, which will serve as a reference point for policies aimed at planning and protection. Consequently, the aim of this study is to determine the impact of the ‘casas particulares’ tourism in Viñales, both in physical terms (modifications to residences and the urban environment) and social terms (changes, ‘benefits and losses’ perceived by the owners/hosts of the accommodation for rent). The questions we have specically asked are: What characteristics does the renting of ‘casas particulares’ in Viñales have?, How does the renting of ‘casas particulares’ affect them and the protected urban landscape? What perception do renters have of this activity and its effect on their lives and daily living spaces?

The methodology uses both quantitative and qualitative techniques. Our fieldwork enabled us to inventory and map as many as 392 houses that rent out rooms, identified by a symbol in the main entrance. Once the houses for rent had been identified, we made appointments with 74 landlords of private houses and conducted structured interviews. The guide used for the interviews had four sections. The first collected sociodemographic data (age, level of education, employment sector, among others); the second collected data about the residence (such as commercial name, postal address, year of construction and the difference parts that make up the residence and the modifications made to it as a result of its use as a casa particular); the third section examines the reasons why the owners began renting out their ‘casa particular’ and how they have developed the business; and in the fourth section, the interviews ask about the owners’ personal experiences of renting their homes, such as how it has influenced their lifestyles, their incomes, their privacy and the level of stress that it may generate. In addition, between 2008 and 2013 we stayed in a variety of private houses at different times, which enabled us to engage in participant observation and fine tune the results we obtained.

After the introduction, first section describes the context and discussion of the problems analysed and the objectives, questions, and research methodology. After this, the second section discusses urban heritage as a resource, whereas the third section focuses on Viñales as a protected natural and urban landscape which is undergoing an increase in tourist activity. The fourth section analyses the relationship between renting houses to tourists and the impact on residential and social areas in recent years. Finally, the results are discussed, and the conclusions are presented.

The urban landscape: a tourist resource

The cultural landscape has been described as a social and cultural product, a cultural projection of society on a particular area. It is possible to say that the landscape is like a document of human history related to human values and place (Sauer, Citation1925). The various layers of the landscape show the cultural values of a community (Nogué, Citation1989, Citation2007, Citation2008) and the signs that give each region its own character (Besse, Citation2000; quoted in Mata, Citation2008), which are useful for understanding the landscape as heritage and a resource (Martínez de Pisón, Citation1997; Mata, Citation2008; Ortega, Citation1998; Sanz, Citation2000). According to the European Landscape Convention, ‘“Landscape” means an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors’ (Council of Europe, Citation2000, p. 2) and is a fundamental dimension of the patrimonial richness of regions (Troitiño & Troitiño, Citation2016).

The concept of urban landscape was included in the Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding of Beauty and Character of Landscapes and Sites, approved by the UNESCO in 1962 (Lalana, Citation2011; Zoido, Citation2012). Thirty years later, in 1992, UNESCO established the criterion that cultural landscapes would be included on the heritage list for ‘exceptional character amongst the combined works of nature and of man, which are of outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological, and/or anthropological points of view’ (Gómez-Mendoza, Citation2013, p. 11).

The management of historical urban landscapes obliged new heritage – conservation policies to be formulated. UNESCO described the historical urban landscape as an urban area resulting from the historical stratification of values and cultural and natural attributes that covers the general urban context and its geographical environment, above and beyond the historical site or centre (UNESCO, Citation2011). Authors such as Lara (Citation2002) and González-Varas (Citation2016) consider that the economy needs to be conserved and developed if the urban landscape and heritage, which must be protected, are to acquire value. Urban historical heritage, then, can be used to catalyse a city’s socioeconomic development. The heritage and all its associated assets are, therefore, a beneficial resource for local development (Lazzarotti, Citation2013), as well as an opportunity for conservation (Zárate, Citation2016). However, this resource is a delicate and fragile one (Andrés, Citation1998), and its exploitation for purposes of tourism can have socioeconomic and functional impacts (Citation2012; Prats, Citation2011; Troitiño, Citation1998 & Vera & Dávila, Citation1995).

There is the danger that economic dynamism may be slowed down by the conservation of specific heritage buildings, which may lead to historical urban landscapes being transformed into museums (Brandis & Del Río, Citation1998; De la Calle, Citation2002; De la Calle & Gracia, Citation1998). In turn, depending on the type of heritage resources and the intensity with which they are exploited, they may degrade (Gómez-Mendoza, Citation2013; Nogué, Citation1989; Sanz, Citation2000).

Viñales: natural and urban landscape, world heritage, and tourist destination

Viñales is a Cuban town in the northern-central area of the province of Pinar del Río, 28 km from the capital of the province and with an area of 714 square kilometres. The biggest mountain range is the Sierra de los Órganos, a karstic landscape consisting of a combination of valleys and peculiar hills called ‘mogotes’. The Viñales Valley itself has a surface area of 74 square kilometres, 10% of the whole municipality (ONEeI, Citation2015). The area has 3 main towns (Viñales, República de Chile, and El Moncada), 12 concentrated rural villages and some others that are more scattered. In 2015, its population was 27,806 inhabitants, about a third of whom lived in Viñales, the main town (IPF, Citation2014; ONEeI, Citation2015).

The town of Viñales began in the 1860s as a small collection of houses at a crossroads between a large area of farmland and the city of Pinar del Río. It was formally recognised as a village in the last third of the nineteenth century and separated from Pinar del Río in 1878. The original activity of the Viñales Valley was cattle farming, which was subsequently replaced by growing and selling tobacco, which led to the development of the town.

Viñales has a historic centre with a heritage value that is in ‘harmony and coherent with the image of the whole’ (Menéndez-Cuesta, Citation2015, p. 229). This means that the heritage value of the ‘villa’ is not derived from the presence of architecturally or historically unique buildings (for example, a large cathedral or a castle), but that its uniqueness lies in the preservation of all the traditional and, in many cases, humble houses that originally constituted the town. At first, the town developed along the road connecting Puerto Esperanza and the city of Pinar del Río and then, along a parallel street. The subsequent growth led to the traditional grid-shaped outline with rectangular islands, formed by single-family buildings with a single floor, paired with adjoining buildings, with an extensive facade in the form of long strips and with arcades and backyards (Melero, Citation2005).

The houses were built with perishable materials (wood and ‘guano,’ the Cuban word for palm leaves), replaced by the light creole-tile roofs, wooden ceilings and the column system in the porticos. This typology, mostly in buildings with heritage value, led to a highly homogenous urban landscape. For a long time, there was the lack of development and dynamism which meant that the area stagnated (Hernández, Citation2012; Mesa, Citation2008), but then in the 1970s, new areas of urban development (Alonso, Citation2010) gave rise to higher buildings that broke the original profile of the urban landscape (Melero, Citation2005).

The convergence of natural and cultural heritage means that the area has been subject to various forms of conservation. In 1979, the natural site of the Viñales Valley and the colonial urban area of the historic site were declared a National Natural Monument, with an area of 3907 ha. In 1980, the Revitalisation Plan for Viñales was drafted, with the order to preserve and prioritise its historical value and maintain a coherent image for the whole town. Subsequently a series of recommendations were made for architectural development (Dirección Provincial de Planificación Física, Citation1988a), a master Plan for Viñales Town Centre was drafted (Dirección Provincial del Planificación Física, Citation1988b) and a study of the town centre was made (Dirección Provincial de Planificación Física, Citation1990).

In 1999 the Viñales Valley was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. This decision was based on the exceptional karstic landscape, and also on the human criterion of the traditional ways of life in tobacco plantations which had cultural and architectural expressions all of their own. It protected up to 7419 ha. The value of the built heritage lies in the homogeneity of the whole and the type of architecture concentrated in the original area, which is a synthesis between agricultural activity and urban settlement (Rigol, Citation2005). The Viñales Management Plan zoned the historical urban site, identified the built heritage to be protected, formulated restrictions for its preservation and established regulations for both the historical nucleus and the Viñales environment (Oficina de Patrimonio, Citation1999). Despite this, there was no technical infrastructure for its effective application (Cabrera & Reyes, Citation2005).

Shortly after, in 2001, the Cuban authorities declared Viñales a national park covering an area of 150 km2. The buffer area of the park was considered to be a suitable an area for the sustainable development of tourism (Hernández, Citation2012). This in turn meant that a Regional Plan for the Tourist Hub of Viñales (Departamento de Planeamiento Turístico, Citation2001) was needed. The plan included new regulations for the protection of urban heritage, such as the prohibition of non-residential uses, the modification of facades and roofs, and the construction of second floors.

Concern about the impacts of tourism development led to the creation of the Viñales General Plan of Urban Management between 2006 and 2009. This plan specified four degrees of protection for the buildings in the urban centre of Viñales. The plan meant that 5% of the houses were given the highest degree of protection; 45% the second highest; 35% the third highest and 15% the fourth highest. The impacts of tourism on Viñales caused concern due to the fragility of its residential heritage, the occurrence of natural disasters and the actions of its inhabitants. The diagnosis highlighted the need to preserve the heritage and the lack of conservation and rehabilitation initiatives needed to ensure this (Menéndez-Cuesta, Citation2015, p. 251).

Results

The realisation that the landscape in Viñales had a value turned it into a priority area for developing tourism. As long ago as 2005, visitors numbered 800,000 with increases of over 50,000 visitors per campaign (Menéndez-Cuesta, Citation2015). Nowadays, the area’s economy is based on tourism, an important part of which is renting houses and the services provided by the tenants. To see what consequences this activity has on the urban landscape and on the tenants’ lives, we now go on to discuss impacts of renting for purposes of tourism.

The impacts of renting houses to tourists in Viñales

The Regional Plan for the Tourist Hub of Viñales (Departamento de Planeamiento Turístico, Citation2001, p. 127), stated that because of the ‘impact of tourism on the town, a study needs to be made of the housing and the services in the town centre.’ At that time, there were 173 houses being rented out to tourists and the plan suggested that this be increased to 300 (Departamento de Planeamiento Turístico, Citation2001, pp. 87–88). The general trend was growth: in 1998 there were 62 of these houses (Ecovida, Citation2003) and by 2004 this number had increased to 350 (Rojas, Citation2005). In 2005, the number fell to 261 (León & San Martín, Citation2016) whereas in 2007 the number of tenants offering ‘food and Cuban traditions to foreign visitors’ increased to 297 (López, Citation2007). In 2016 León & San Martín recorded 700 houses with 1300 rooms (León & San Martín, Citation2016), although this figure probably included the whole town. Finally, a group of tenants in Viñales provided the town with 911 houses with 1900 rooms that were ‘visited by 80% of the province’s new tourists’ (Carta, Citation2016: not paginated). According to the Ministry of Tourism, there were 365 houses in Viñales town centre in 2017, while on the Homestay.com web portal 605 houses were on offer for accommodation with families (last checked 11/2018). This figure did not include some houses because they did not fulfil all the requirements.

On the landlords

It can be seen, then, that house rental was increasing rapidly, but what do we know about the owners of these houses, the landlords? The average age of the landlords was 48, and most of them were between 40 and 49 (35%), then 30–39 (22%) and 50–59 (14%). It should be pointed out that 25% of the total number of landlords were over 60. In terms of education, many landlords have university degrees (43.24%); 27.03% have received technical training; 18.92% have medium levels of education; 9.46% have completed their secondary education; and 2% have completed primary education. It seems clear that the more educated someone is, the more likely it is, first, that they will see the opportunity for business that room rental offers; second, that they will be able to apply their knowledge of management; and third, that their greater professional status and their age will enable them to have acquired a house with the features required for renting.

Some authors (Lynch, Citation2005; McIntosh, Lynch, & Sweeney, Citation2011), believe that ‘homestay’ accommodation is generally a complementary source of income to homeowners’ principal sources of earnings; however, 45.95% of the respondents stated that it is their only source of income. If we add to this figure all those landlords who said they were homemakers or retired, renting is the main economic activity for 58.18% of the respondents. Other main economic activities are tourism (12.16%), services (5.41%), education (5.41%) and culture (4.05%). Only three landlords responded that agriculture is their main activity, which shows a dissociation between the reason why the Viñales Valley is attractive to tourists – its natural and cultural landscape of tobacco plantations and ‘mogotes’ – and its guarantors, the farmers.

Renting is regulated by the Cuban government and renters have to pay monthly taxes. A total 36.1% respondents think that these are appropriate, whereas 30.0% state that they are unfair for a variety of reasons, with some complaining that they pay the same tax regardless of the location of their home (in the centre or on the periphery) or that they pay the same rate in high and low season, regardless of the money they earn. Respondent #37 states that

the taxes are appropriate but they are inflexible, for example, they should not charge us during those months when we have no customers or, better still, it would be fairer to pay a rate that was based on the amount of money you earnt: if you earn, you pay the tax, if you don’t it is unfair to pay a fixed tax.

the tax should reflect where the home is located, for example, (…) why should a landlord whose home is in one of the backstreets pay the same as someone whose home is on the main road where there is more accommodation and customers turn up regularly?

Another important issue mentioned in the interviewees’ responses is that they avoid ‘doing anything illegal’ as they are afraid of losing their license or being sanctioned by the Cuban authorities. Although a special license is needed, for example, to work as a tour guide, it is common for the landlord to offer these services in an informal way. Some of the services that are provided ‘illegally’ are horseback riding, bike rides or walks in the valley. Another activity that landlords avoid is exchanging clients.

When they were asked about the qualities of a good host, the landlords answer that they need to be friendly, kind, polite, trustworthy, reliable, noble, honest, and ‘respectful to the tourist’. The interviewees insist on being ‘a good Cuban’ or being ‘oneself,’ concepts that are essential to the tourist’s quest to experience and live with local society.

The landlords organise activities to make the tourist feel at home and at ease. They insist that they must ‘care for them properly and provide them with a good service,’ cook well and be clean, work hard, be efficient, and ‘offer a quality service’. To be able to offer this service, they ‘learn about their tastes and preferences’. Finally, they believe that establishing a relationship with the tourist is important and that spending time talking is fundamental. Being communicative is constantly mentioned in the interviews. One of the landlords even mentioned that he reads up on the tourists’ country so that he can have something to talk about.

Over half of the landlords believe that the tourists are not much trouble, but those who find them a nuisance say that it is because they have little respect for the house rules, smoke, make noise, bring friends in, or try to negotiate prices. They also complain that they are indifferent, uncommunicative and anti-social.

On the rental homes

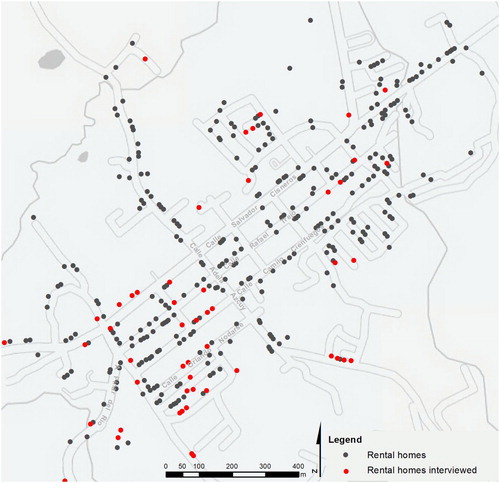

shows all the rental homes available in Viñales town centre (gray and red) and the ones which we have visited and where we have interviewed the landlords (red). As can be seen, the rental homes are not limited to the historical centre and can be found throughout the whole settlement.

Figure 1. Location of rental homes and the rental homes where the owners were interviewed. Base Map: openstreetmap.org. Source: authors.

The rental homes are of a variety of types. In terms of the extent to which they are protected, the houses offering rooms for rent have similar values to the houses in Viñales as a whole: level of protection 1, 1.0%; level of protection 2, 33.0%; level of protection 3, 42.8%; and level of protection 4, 23.2%. In general, the houses are single-storey (79.7%), although 6.8% have two storeys and one house has four. They have between one and nine rooms. The most frequent number of rooms is three (39.2%), followed by four (25.7%). The houses are shared: that is to say, they are the owner’s habitual residence and the tourist’s holiday residence, which means that they need to be big enough for both uses. The owners are required to provide tourists with a bathroom for their exclusive use, so 47.3% of the houses have 2 bathrooms and 23% have 3; 70.3% have a kitchen and 24.3% have 2. In the latter case, the traditional kitchen is in the inside of the house and the open kitchen is in the patio. The kitchen is an important room, since tourists normally require food to be provided, which is supplementary income for the landlord.

The traditional houses in the historic centre of Viñales have a backyard with fruit trees, in which animals are kept and vegetables are grown. The front yard is generally a garden with a portico on the main façade. Of the rental homes, 45.9% have a backyard, 52.7% have a front garden, and 39.2% have a portico.

To determine the impact of tourism on housing and the urban landscape, we analysed the changes they have undergone. Of all the houses analysed, 52.8% have undergone some sort of change. In some cases, extra rooms have been added (1 room in 38.5% of the houses; 2 in 28.2%, and 3 in 12.8%); and in others, a bathroom has been added for the exclusive use of the tourists (20.5%). In most cases (approximately 60%), these extensions have been made at the expense of reducing or eliminating the backyard, while in a few cases another floor has been added to the house.

The increase in the built-up area has had several effects on the urban landscape of Viñales. Of particular importance is the decrease in the amount of green space because of houses being extended into backyards (), the disruption of the skyline because of extra storeys being added to originally one-storey houses () and the loss of a unified urban image with the increase in height, the use of new building materials, architectural finishes that imitate the style of North-American houses (turned balustrades, closed front gardens or excessive decoration), or with landlords making adaptations to match what they believe to be tourist expectations, such as Caribbean colours (Pérez, Nel·lo, & Muro, Citation2018).

Discussion and conclusions

This increase in living standards works in favour of maintaining and conserving the urban environment. In the specific case of Viñales, Mesa and Cordova (Citation2013:, p. 677), agree with the results of the present study and believe that the increase in quality of life has improved ‘the structure and aesthetics of the residences (…) they are looked after, the gardens are well tended and plants are sown (…)’.

In the case of Viñales, the quality of its urban landscape has been affected. Exploiting built-up space to maximise income has an effect on heritage houses. People extend their houses to the limit, so their new features are a symbolic and practical response to the socioeconomic conditions associated with tourism (Palmer, Citation2014). Extensions into backyards has reduced green spaces, leading to considerable saturation and congestion of the urban area, which is gradually being clogged by new buildings. Also, the loss of patios means that residents no longer have the space for activities and leisure. The decrease in vegetation and the addition of extra storeys to some houses modify the skyline and change traditional views. New materials, changes to roofs and the introduction of new types of building break the unity of the town’s landscape and jeopardises its conservation as collective heritage.

Houses have been improved to create pleasant spaces and offer appropriate services, but in some cases these improvements create spaces that are not traditional and there is a risk of the town turning into a ‘theme park’ and losing its ‘real’ authenticity. But it is also true that renting rooms in private houses enables tourists to find accommodation without having to build hotel complexes, which have a greater impact on the urban landscape.

In ‘home stays’, tourists derive satisfaction directly from the fact that they are living with a family in their own home, which gives their visit meaning. And if they are staying in a colonial house, the experience is a special one. Even so, the local people are not aware of the need to preserve or restore heritage houses responsibly. In this regard, responsible tourism in rental homes can also be used to spread the values of their heritage and it should not be forgotten that people often value their own heritage more when they see that outsiders attach importance to it.

The people who actually manage home-stays are usually women with a university education. This result coincides with the finding of Anna Cristina Pertierra (Citation2008) in her analysis of the woman-home relationship in Santiago de Cuba. She states that since the 1990s the benefits of participating in the official labour market in Cuba decreased, which meant that the home became a centre for both legal and illegal economic activities which were mostly conducted by women, including even highly qualified ones. In addition, the advantage of homestay programmes extends beyond the economic benefits. The commercialisation of the home offers women new professional opportunities (Galbreath, Citation2017). Another characteristic that agrees with the findings of other studies is that for a high percentage the primary occupation of the homeowner is managing the ‘casa particular’. This situation differs from typical homestays where the homeowners’ principal occupation is agriculture and/or pastoral farming and tourism is merely a complementary source of income (Galbreath, Citation2017; Jamaludin et al., Citation2012; McIntosh et al., Citation2011).

There is no doubt that the everyday life of landlords has been affected. In ‘casas particulares,’ the home, a private space, becomes a place of work into which owners welcomes tourists whilst continuing to go about their daily lives with their families. The need to please the tourist, as described by most of the interviewees, is linked to the definition of ‘emotional labour’ by Hochschild (Citation1983). The interviewees are referring to this when they clearly describe how they have to be and behave: they need to be affable, good people, pleasant, responsible, trustworthy, considerate, honest and, finally, they need to respect the tourist. For some owners of ‘casas particulares,’ all of these characteristics can be summarised in the all-encompassing phrase ‘to be a good Cuban’. These demands on their behaviour, when added to the increased amount of housework, have implications on the homeowners because 58.1% admitted that they suffer from anxiety or stress, one of the most common consequences of emotional work.

Renting out rooms influences relations with family members, friends and neighbours. On one hand, the tasks related to tourist activity limit their free time so that visits or trips with family members and friends are reduced. Furthermore, some trips that can be considered leisured-focused are carried out with tourists, without third parties being invited. Also, family members and friends are unwilling to visit renters because they are afraid of bothering the tourists. These limitations, self-imposed by landlords and their families, are entirely coincident with the results achieved by Mesa (Citation2008) and Mesa and Cordova (Citation2013).

In the case of hosts (the owners of ‘casas particulares’) and guests (the tourists) and in keeping with the theory of emotional work, it is likely that the former is really just acting out a role for the benefit of the latter. This view is partly corroborated by the findings of Simoni (Citation2016) who, in part of his book ‘Tourism and Informal Encounters in Cuba,’ analyses relations between tourists/buyers and premises / tobacco sellers in Viñales and Havana and arrives at the conclusion that these vary from being a simple ‘market exchange’ to different types of ‘hospitality.’ In the present case, the host–guest relationship is always conditioned by the commercial activity and can be summarised in the comment of interviewee #1 ‘I love being a host, especially when I charge (the bill) (laughter).’

Supplemental income for hosts in rural areas contributes to economic and community development. Revenue earned by hosts can be channelled through the community as a result of direct, indirect, and induced spending. Landlords are definitely earning more money but their desire to please tourists has led to new economic activities being introduced. Home rental improves the economy and provides generally informal work for a considerable number of people (cleaning, laundry, tourist guides and other unregulated activities), but it also raises social issues because it leads to two quite distinct social classes: landlords, who are paid in dollars, and those who are paid in Cuban pesos. This double economy has consequences. For example, landlords monopolise building services – many couples have found that they are effectively excluded from the urban area because they cannot afford to pay for the materials or for professional builders for a new house – or they purchase all the crops produced by local farmers to cover the tourists’ needs, which pushes up prices. In terms of employment, tourism is an attractive proposition and there is often a scarcity of accommodation, which often prompts local workers to leave their jobs and work in home rental.

Generally speaking, it is worrying to see that income from tourism is not evenly distributed in the population. In particular, it is the farmers who tend to lose out despite the fact that they have been the guardians of the world heritage landscape characterised by tobacco plantations and their associated traditions and architecture.

To sum up, in recent years, Viñales has been gradually deteriorating because of a lack of control and, as Menéndez-Cuesta (Citation2014 & Citation2015), urban regulations need to be redefined, public spaces need to be appreciated and the visual aspect of the landscape needs to be taken into account so that decisions can be taken about urban development and changes, because the very heritage of the region is in danger. The declaration of Viñales as a world heritage site has promoted a kind of tourism that has boosted local economic development, but it has also had other more negative impacts and, although considerable effort has been made to reconcile protection with economic pressures, there is still a great deal of work to be done (Rigol, Citation2015).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yolanda Pérez Albert

Yolanda Pérez Albert (PhD) is a Senior lecturer at the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Tarragona, Spain). Her main research interests are Geographical Information Technologies applied to the management of tourism activity, the impact of tourism in protected areas and the quality of the landscape and its public use.

José Ignacio Muro Morales

José Ignacio Muro Morales (PhD) is a Senior lecturer of human geography at the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Tarragona, Spain). In recent years, he has carried out various researches on urban geography: reform and renovation of vulnerable urban areas and the dynamics of citizen participation. He is currently researching the urban landscape as a collective value.

Marta Nel-lo Andreu

Marta Nel·lo Andreu, (PhD) is a professor of Geography of Tourism and Recreation and Geographies of Development at the Rovira I Virgili University (Tarragona). She is part of the Research Group on Territorial Analysis and Tourism Studies (GRATET). In recent years she has carried out various researches on tourism and development, ecotourism and social impacts of tourism research. Since 2010 she is International Coordinator of The International Investigators Network of Tourism, Cooperation and Development (COODTUR).

References

- Alonso, A. N. A. (2010). El paisaje cultural del Valle de Viñales, análisis de sus cambios durante el período 1971–2005 [The cultural landscape of the Viñales Valley: analysis of the changes between 1975 and 2005] (M.Ths in Geography, Environment and Territorial Planning). La Habana: Universidad de La Habana, Facultad de Geografía, 62 pp.

- Alonso, M. (2012). El papel de las casas particulares en la promoción del destino Cuba. La experiencia de la casa Bellavista – Havana [The cultural landscape of the Viñales Valley: analysis of the changes between 1975-2005]. In 2ª Convención Internacional de Estudios Turísticos. La Habana, Cuba: Universidad de La Habana.

- Álvarez, G. (2009). Estudio de factibilidad económico-financiera de la propuesta de desarrollo turístico del Municipio de viñales [Economic-financial feasibility study of the proposal for developing tourism in the municipality of Viñales]. Facultad de Ciencias, Sede Universitaria Minas de Matahambre. Retrieved from http://www.monografias.com/trabajos76/factibilidad-economico-financiera-desarrollo-turistico/factibilidad-economico-financiera-desarrollo-turistico3.shtml#ixzz4RJDDODC4

- Andrés, J. L. (1998). El paisaje urbano como recurso turístico [The urban landscape as a tourism resources]. In Á. L. Molina Molina, J. L. Andrés Sarasa, C. Espejo Marín, J. Lamba Maurandi, J. J. Eiroa García, & C. M. Cremades Griñan (Eds.), La recuperación de los núcleos urbanos y su entorno. Aportaciones para su estudio histórico-geográfico (pp. 19–45). Murcia, Spain: Universidad de Murcia, Servicio de Publicaciones.

- Besse, J.-M. (2000). Voir la Terre. Six essais sur le paysage et la géographie [Seeing the Earth. Six essays on landscape and geography]. Arlés: Actes du Sud ENSP/Centre du Paysage, 161 pp.

- Brandis, D., & Del Río, I. (1998). La dialéctica turismo y medio ambiente en las ciudades históricas: una propuesta interpretativa. Ería, 47, 229–240.

- Cabrera, N., & Reyes, M. (2005). El Plan de Manejo. In M. Vendittelli, M. Arjona, & M. Terreni (Presentadores) (Eds.), Viñales, un paisaje a proteger [Viñales: An exceptional natural and cultural place] (pp. 57–66). La Habana, Cuba: ORCALC/UNESCO.

- Carta. (2016). Carta a Raúl Castro del colectivo de arrendatarios de Viñales [Letter to Raúl Castro from the tenants of Viñales]. Retrieved from https://cibercuba.com/noticias/2016-07-04-u1-carta-raul-castro-del-colectivo-de-arrendatarios-de-vinales?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium

- Communist Party of Cuba. (2011). VI Congreso del Partido Comunista de Cuba. Lineamientos de la política económica y social del partido y la revolución [The 6th Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba. Guidelines of the Economic and Social Policy of the Party and the Revolution]. Retrieved from https://www.pcc.cu/sites/default/files/documento/pdf/20180426/lineamientos-politica-partido-cuba.pdf

- Council of Europe. (2000). European landscape convention. Florence: 20.X.2000. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/1680080621

- Council of State. (1993). Gaceta Oficial. 8 de septiembre, n° 5 extraordinario, 11.

- Council of State. (1997). Decreto-Ley N° 171 de 15 de mayo de 1997 sobre el arrendamiento de viviendas, habitaciones o espacio [Decree Law No. 171, May 15, 1997 on the rental of homes, rooms or spaces].

- De la Calle, M. (2002). La ciudad histórica como destino turístico [The historical city as a tourist destination]. Barcelona: Ariel. 302 pp.

- De la Calle, M., & Gracia, M. (1998). Ciudades históricas: patrimonio cultural y recurso turístico [Historical cities: cultural heritage and tourism resource]. Ería, 47, 249–266.

- Departamento de Planeamiento Turístico (DPT). (2001). Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial. Polo Turístico Viñales [Regional Plan. The Tourist Hub of Viñales]. Pinar del Río: Dirección Provincial de Planificación Física. 143 pp.

- Dirección Provincial de Planificación Física de Pinar del Río. (1988a, February). Algunas consideraciones y recomendaciones inmediatas para el desarrollo arquitectónico y urbano del pueblo de Viñales [Some immediate considerations and recommendations for the architectural and urban development of Viñales], 18 pp.

- Dirección Provincial de Planificación Física de Pinar del Río. (1988b, September). Plan Director del Núcleo Urbano de Viñales [Master plan for the Urban Cenre of Viñales], 31 pp.

- Dirección Provincial de Planificación Física de Pinar del Río. (1990, March). Estudio de centro en el núcleo urbano de Viñales [Study of the Viñales town centre], 52 pp.

- Echarri, M., Cisneros, L., Robert, M. O., & Perera, L. (2019). Emprendimientos turísticos: realidades y desafíos para Cuba [Tourist entrepreneurship: Realities and challenges for Cuba]. Economía y Desarrollo, 161(1), e5.

- Ecovida. (2003). Parque Nacional Viñales. Plan de Manejo (2004-2008) [Viñales National Park. Management Plan (2004-2008)]. Pinar del Río, Cuba: Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Medioambiente.

- Galbreath, A. (2017). Exploring tourism opportunities through homestay/homeshare, Clemson University. All Theses. 2625. Retrieved from https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2625

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books.

- Gómez-Mendoza, J. (2013). Del patrimonio-paisaje a los paisajes-patrimonio [From Heritage as landscape to landscape as Heritage]. Documents D’Anàlisi Geogràfica, 59(1), 5–20. doi: 10.5565/rev/dag.48

- González-Varas, I. (2016). La ciudad y su paisaje histórico [The city and its historical landscape]. In I. González-Varas (Ed.), Ciudad, Paisaje y Territorio. Conceptos, métodos y experiencias (pp. 21–143). Madrid: Editorial Munilla-Lería.

- Hernández, C. L. (2012). Influencia del turismo en el desarrollo local de Viñales. Efectos positivos y negativos de la industria turística en el desarrollo de Viñales [The effect of tourism on local development in Viñales. Positive and negative effects of the tourist industry on the development of Viñales]. Madrid: Académica Española. 136 pp.

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press. 327 pp.

- Instituto de Planificación Física de Cuba (IPF). (2014, October). Población de los asentamientos humanos cabeceras municipales según censos 1970, 1981, 2002 y 2012 [Population of the main human municipal settlements according to the censuses of 1970, 1981, 2002 and 2012]. La Habana.

- Ismail, M. N. I., Hanafiah, M. H., Aminuddin, N., & Mustafa, N. (2016). Community-based homestay service quality, visitor satisfaction, and behavioral intention. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 222, 398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.192

- Jamaludin, M., Othman, N., & Awang, A. R. (2012). Community based homestay programme: A personal experience. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 42(2010), 451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.04.210

- Lalana, J. L. (2011). El paisaje urbano histórico: modas, paradigmas y olvidos [The historical urban landscape: modes, paradigms and omissions]. Ciudades, 14(1), 15–38.

- Lara, J. J. (2002). El patrimonio urbano del siglo XXI: políticas y estrategias sobre el patrimonio integral urbano [The urban heritage of the 21st century: policies and strategies on integral urban heritage]. In P. Pumares, M. A. Asensio, & F. F. Fernández, (Coords.) (Eds.), Turismo y transformaciones urbanas en el siglo XXI (pp. 397–433). Almería: Universidad de Almería.

- Lazzarotti, O. (2013). Patrimoine et tourisme: histoire, lieux, acteurs, enjeux [Heritage and tourism: history, places, actors and challenges]. Paris: Belin.

- León, A., & San Martín, A. C. (2016). Viñales, de la parálisis al ‘boom’ privado. (repleta de turistas, en la zona escasean los lugares para hospedarse) [Viñales: from paralysis to private boom] CUBANET. Noticias de Cuba, May 2, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.cubanet.org/destacados/vinales-de-la-paralisis-estatal-al-boom-privado/

- López, L. (2007). Gestión del Patrimonio Natural con fines turísticos en el valle de Viñales, sitio declarado Patrimonio de la Humanidad [Management of natural heritage for tourism purposes in the Viñales Valley, a world heritage site] (Phd Thesis). Tutors Antonio Ramos & Eduardo Salinas, Universidad de Alicante y Universidad de Pinar del Río, 303 pp.

- Lynch, P. A. (2005). Sociological impressionism in a hospitality context. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(3), 527–548. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.09.005

- MacCannell, D. (1973, November). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603. doi: 10.1086/225585

- Martínez de Pisón, E. (1997). El paisaje, patrimonio cultural [Landscape: Cultural heritage]. Revista de Occidente, 194-195, 37–49.

- Mata, R. (2008). El paisaje, patrimonio y recurso para el desarrollo territorial sostenible. Conocimiento y acción pública [The landscape: Heritage and resource for sustainable regional development]. Arbor. Ciencia, Pensamiento y Cultura, CLXXXIV, 729, 155–172.

- McAuslan, F., & Norman, M. (2009). The rough guide to Cuba. Rough Guides, 608 pp.

- McIntosh, A. J., Lynch, P., & Sweeney, M. (2011). “My home Is My castle”. Journal of Travel Research, 50(5), 509–519. doi: 10.1177/0047287510379160

- Melero, N. (2005). Viñales, un sitio natural y cultural excepcional [Viñales: An exceptional natural and cultural place]. In M. Vendittelli, M. Arjona, & M. Terreni (Eds.), Viñales, un paisaje a proteger (pp. 21–30). La Habana, Cuba: ORCALC/UNESCO.

- Menéndez-Cuesta, I. M. (2014). El patrimonio cultural y natural, tema clave de los planes de ordenamiento territorial y urbano [Cultural and natural heritage: The key to the regional and urban organisation plans]. Revista Planificación Física, Cuba, 19, 5–11.

- Menéndez-Cuesta, I. M. (2015). El papel del Ordenamiento Territorial y Urbano en la gestión y conservación del patrimonio [The role of regional and urban organisation in the management and conservation of the heritage] (PhD Thesis). La Habana: Tutored by Ángel Isac & la Dra. Isabel Rigol, 964 pp.

- Mesa, Y. (2008). El arrendamiento de habitaciones en el Valle de Viñales: Una mezcla de cubanía y hospitalidad a la luz de la naturaleza [Room rental in the Viñales Valley: A mixture of Cuban customs and hospitality in the light of nature] (Degree Thesis). La Habana: Departamento de Sociología, Universidad de la Habana.

- Mesa, Y., & Cordova, Y. (2013). El arriendo de habitaciones y casas particulares. Su impacto en el Valle de Viñales [Room rental in the Viñales Valley: a mixture of Cuban customs and hospitality in the light of nature]. In J. A. Márquez Domínguez, R. González Sousa, & A. Rúa de Cabo (Eds.), Actas II Congreso Internacional de Desarrollo local. Por un desarrollo local sostenible (pp. 666–679). La Habana, Cuba: Universidad de La Habana.

- Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social. (2010). Resolución n° 32/2010. Reglamento del ejercicio del trabajo por cuenta propia [Regulation for the exercise of self-employment]. Retrieved from http://cubasindical.blogspot.com/2010/11/resolucion-no-322010-ministerio-de.html

- Molina Rodríguez, J. (2017). El trabajo emocional en el sector turístico. Obstáculos y facilitadores empresariales y su consecuencia para los trabajadores [Emotional work in the tourism sector. Obstacles and business facilitators and their consequences for workers]. Girona: Memoria presentada para optar al título de Dr. por la Universitat de Girona, Dr. Esther Martínez García. 172 pp. Retrieved from https://www.tesisenred.net/bitstream/handle/10803/456584/tjmr_20170711.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Nogué, J. (1989). Paisaje y turismo [Landscape and tourism]. Estudios Turísticos, 103, 35–45.

- Nogué, J., (Ed.). (2007). La construcción social del paisaje [The social construction of the landscape]. Madrid: Ed. Biblioteca Nueva.

- Nogué, J., (Ed.). (2008). El paisaje en la cultura contemporánea [The landscape in contemporary culture]. Madrid: Ed. Biblioteca Nueva, 304 pp.

- Oficina de Patrimonio. (1999). Plan de Manejo Valle de Viñales, Provincia de Pinar del Río, Cuba [Management Plan for Valle de Viñales, Province of Pinar del Río, Cuba] (pp. 72). Viñales, Cuba: Municipio de Viñales, Oficina de Patrimonio.

- Ogden, R. (2019). Lonely planet: Affect and authenticity in guidebooks of Cuba. Social Identities, 25(2), 156–168. doi: 10.1080/13504630.2017.1414592

- ONEeI. Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información. (2015). Anuario Estadístico Pinar del Río, 2014. Viñales [Pinar del Río Statistical Year Book, 2014. Viñales]. 87 pp.

- Ortega, J. (1998). El patrimonio territorial: el territorio como recurso cultural y económico [Regional heritage: the región as a cultural and economic resource]. Ciudades, 4, 33–48.

- Palmer, C. T. (2014). Tourism, changing architectural styles, and the production of place in Itacaré, Bahia, Brazil. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 12(4), 349–363. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2014.934378

- Pérez, Y., Nel·lo, M., & Muro, J. I. (2018). El impacto de la actividad turística en el paisaje urbano. El caso del Valle de Viñales (Cuba) [The impact of tourism on the urban landscape] Paper presented. In II Jornadas Internacionales de Investigación sobre Paisaje, Patrimonio y Ciudad. Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá de Henares y Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes.

- Pertierra, A. C. (2008). En casa: Women and households in post-soviet Cuba. Journal of Latin American Studies, 40(4), 743–767. doi: 10.1017/S0022216X08004744

- Prats, L. (2011). La viabilidad turística del patrimonio [The viability of heritage for tourism]. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 9(2), 249–264. doi: 10.25145/j.pasos.2011.09.023

- Reid-Henry, S. (2007). The contested spaces of Cuban development: Post-socialism, post-colonialism and the geography of transition. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 38, 445–455.

- Rigol, I. (2005). Viñales ¿por qué un paisaje cultural? ? [Viñales: why a cultural landscape?]. In M. Vendittelli, M. Arjona, & M. Terreni (Eds.), Viñales, un paisaje a proteger (pp. 31–38). La Habana, Cuba: Oficina Regional de Cultura de la UNESCO.

- Rigol, I. (2015). La recuperación del patrimonio monumental en Cuba [Recovering historical heritage in Cuba]. In L. Gómez & O. Niglio (Eds.), Conservación de centros históricos en Cuba (pp. 35–60). Roma, Italy: Esempi di Architettura, Aracne Editrice.

- Rojas, A. (2005). Entre Pinar y Esperanza [Between Pinar and Esperanza]. In M. Vendittelli, M. Arjona, & M. Terreni (Eds.), Viñales, un paisaje a proteger (pp. 29–43). La Habana, Cuba: ORCALC/UNESCO.

- Samsudin, P. Y., & Maliki, N. Z. (2015). Preserving cultural landscape in homestay programme towards sustainable tourism: Brief critical review concept. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 170(2015), 433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.004

- Sanz, C. (2000). El paisaje como recurso [Landscape as a resource]. In E. Martínez de Pisón (Ed.), (Dir.). Estudios sobre el paisaje (pp. 281–291). Madrid: Fundación Duques de Soria, UAM.

- Sauer, C. O. (1925). The Morphology of Landscape. University of California Publications in Geography, vol. 2, no. 2, 19–54, reprinted in J. Leighly, 1963 (Ed). Land and Life: A Selection from the writings of Carl Ortwin Sauer, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles: 315–350.

- Simoni, V. (2016). Tourism and informal encounter in Cuba. New York: Berhahn, 266 pp. Retrieved from https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.cu/html/iarrendamiento.html

- Troitiño, M. A. (1998). Turismo y desarrollo sostenible en ciudades históricas [Tourism and sustainable development in historical cities]. Ería, 47, 211–227.

- Troitiño, M. A. (2012). Turismo, patrimonio y recuperación urbana en ciudades y conjuntos históricos [Tourism, heritage and urban recovery in cities and historical ensembles]. Patrimonio Cultural de España, 6, 147–164.

- Troitiño, M. A., & Troitiño, L. (2016). Patrimonio y turismo. Reflexión teórico-conceptual y una propuesta metodológica integradora aplicada al municipio de Carmona (Sevilla, España) [Heritage and tourism. Theoretical-conceptual reflection and a methodological proposal for integration applied to the municipality of Carmona (Seville, Spain)]. Scripta Nova , XX (543).

- UNESCO. (2011). Recomendación sobre el paisaje urbano histórico [Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, including a glossary of definitions]. Retrieved from http://portal.unesco.org/es/ev.php-URL_ID=48857&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

- Vera, F., & Dávila, M. (1995). Turismo y patrimonio histórico-cultural [Tourism and historical-cultural heritage]. Estudios Turísticos, 126, 161–178.

- Zárate, M. A. (2016). Paisajes culturales urbanos, oportunidad para la conservación del patrimonio y el turismo sostenible [Urban cultural landscapes: opportunity for the conservation of heritage and sustainable tourism]. Estudios Geográficos, 77(281), 693–728. doi: 10.3989/estgeogr.201624

- Zoido, F. (2012). Paisaje urbano. Aportaciones para la definición de un marco teórico, conceptual y metodológico [Urban landscape. Contributions to the definition of a theoretical, conceptual and methodological framework]. In C. Delgado, J. Juaristi, & S. Tomé (Eds.), Ciudades y paisajes urbanos en el siglo XXI (pp. 13–92). Santander, Spain: Ediciones de Librería Estudio.