?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Understanding elderly consumers’ behaviour can be an effective tool for planning the tourist market. The changing demographic structure of the population poses new challenges, which require greater involvement of both the state and the private sector in addressing the issues of the aging society. The main objective of the article was to determine whether seniors’ tourist trips impacted on their final migration. An additional purpose was to establish the senior migrant profile. In order to answer the research question, primary quantitative research was performed, which consisted in collecting information from respondents through a standardized questionnaire. To systematize the reasons for seniors’ migrations, a cluster analysis (Ward’s method) was applied. The seniors moved to places where they found a clean environment of considerable tourist values. The migration improved their living standards and life quality. Almost half of the pensioners had previously visited the place where they moved to permanently.

Introduction

Knowing and understanding the behaviour of elderly consumers can be an effective tool for planning the tourist market, developing tourist products, and introducing innovations in tourism. Seniors’ participation in tourism is a more and more frequently discussed issue, both in theoretical considerations and in practitioners’ debates. Elderly people are perceived as an increasingly significant segment of the tourist market. In addition to the potential resulting directly from the dynamically growing size of the senior population, other important characteristics of the group are more and more often noticed: among others, large amount of free time, improving educational and financial structure, increase in physical and social activity. These promote the development of individual motivation for travelling and justify the creation of an offer tailored to the needs of a senior customer. This phenomenon is growing particularly in Europe.

The changing demographic structure of the population poses new challenges, which require much greater involvement not only of the state but also of the private sector in solving problems related to the physical, mental, and social health of seniors, and in planning the seniors’ abundant leisure time. Pensioners, who have a lot of free time at their disposal, spend most of it on recreation. This often becomes an inspiration to move permanently.

Free time is a part of human life in which one can freely decide on the way it is managed. Free time can be spent for recreation, entertainment, or personality development. People engage in leisure time activities of their own free will, and these are seniors who have the most free time among all age groups. Travelling to attractive places, they want to return there and live there permanently.

The main objective of the article was to determine whether seniors’ tourist trips had an impact on their final migration. An additional purpose was to establish the profile of a senior migrant.

Literature review

The influence of physical activity on the well-being and condition of seniors has been confirmed by numerous studies. The literature on this subject is very extensive. As Widawski (Citation2011) points out, one of the most important motives for seniors’ visits to a given tourist destination is health. The number of stays of seniors in spas, as well as in spa & wellness facilities is increasing. Horneman, Carter, Wei, and Ruys (Citation2002), Lee and Tideswell (Citation2005). According to them, the important reasons for travelling by elderly people include the desire to regenerate, rest and relax. It is very beneficial for the well-being and condition of the elderly.

The analysis of demographic forecasts and trends allowed the Polish government to prepare in 2013 the assumptions of the long-term senior policy in Poland in the form of a strategic document (ASOS, Citation2014-Citation2020, Citation2013). The document states that the main goal of the senior policy in the area of health and independence is to create conditions for maintaining good health and autonomy as long as possible, which is important for the development of senior tourism. It also points to the important role of physical activity in seniors. Therefore, this document is of key importance to the promotion associated with the correct habits and exercise.

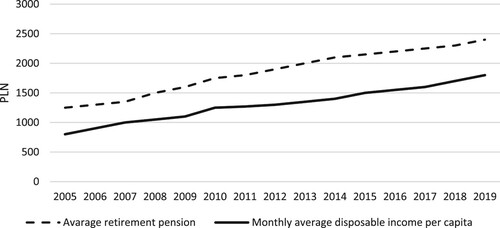

The financial situation of Polish pensioners has been improving every year since 2015, when numerous programs were launched, including Senior+ Program (Citation2021) and Active+ Program (Citation2021). As shown by the data of the Social Insurance Institution, i.e. the body that pays pensions in Poland, each year the amount of the average pension is higher and higher, which at the same time affects the average monthly income in households (). This has an impact on the quality of life of seniors, and thus also on the possibility of travelling. Moreover, as I. Stončikaitė (Citation2021) points out, holidays in the senior period become easier because older people are less responsible for their already adult children and household chores. Stončikaitė also adds that many seniors are willing to spend their savings in order to gain rewarding and meaningful life experiences through unlimited consumption on vacation.

Figure 1. Monthly average disposable income per capita in single retirees’ households and average gross retirement pension from non-agricultural social security system compared in PLN. Surce: Own study based on (Central Statistical Office, Citation2019).

The research on senior tourism is wide and related to its many aspects. It focuses, among others, on active recreation, discussed by Graja-Zwolińska and Spychała (Citation2012), Hołowiecka and Grzelak-Kostulska (Citation2013), or Ociepka and Pytel (Citation2016). The motives and perspectives of senior travelling were studied by Mokras-Grabowska (Citation2010), Niezgoda and Jerzyk (Citation2013), Oleśniewicz and Widawski (Citation2015), or Stasiak (Citation2011). Tourist behaviours were analysed by Bąk (Citation2012a, Citation2012b), Pytel (Citation2014), or Śniadek (Citation2007).

Seniors, having free time, like to travel and when they find a suitable place, they go to live there permanently. Research on the influence of tourism on senior migrations is scarce. The issue has been reported, among others, by King, Warnes, and Williams (Citation2000), who point at studies performed by geographers working in the field of tourism and by other migration researchers. One of the first accounts was that by Karn (Citation1977), illustrating how tourist areas could become places of retirement migration. Cribier and Kych (Citation1992, Citation1993) analysed the main objectives of retirement movements from London and Paris and identified their important stream. Similar trends were observed by Warnes (Citation1993) in Great Britain and Oberg, Scheele, and Sundstrom (Citation1993) in Sweden. Fewer studies have been reported at the international level, but recently this migration has increasingly attracted the attention of scholars, who are conducting many studies on the impact of foreign holidays on retirement migration decisions (Buller & Hoggart, Citation1994; Rodríguez, Fernandez-Mayoralas, & Rojo, Citation1998; Williams & Patterson, Citation1998; Williams, King, & Warnes, Citation1997).

Research of considerable importance was carried out by King et al. (Citation2000), who studied tourists in Tuscany, in Malta, on the Costa del Sol, and in the Algarve. These are areas of different histories, both in terms of tourism development and international migration. Tuscany has long been of interest to both tourists and foreign settlers, and its cities and rural areas are home to a large number of relatively wealthy and well-educated British retirees. Malta is also a characteristic region of pension migration, attracting ex-soldiers who served in British military bases on the islands and those who are married to Maltese women. In turn, retirement migration both on the Costa del Sol and in the Algarve has grown largely from mass tourism (Rodríguez et al., Citation1998; Williams & Patterson, Citation1998).

Large-scale migration of senior citizens to Southern Europe is a relatively new phenomenon. Despite the nineteenth and twentieth century traditions in Italy and later trends on the French Riviera, the inflows were felt only after 1960.

According to Williams et al. (Citation1997), the main reasons for pension migration development are the following:

increase of life expectancy;

income growth and wealth accumulation;

changing mobility patterns, which have provided more knowledge and experience of living in foreign places.

This is partly due to economic migration after 1945, but also to the rapid growth of international tourism.

A particular Southern European attraction for retirement migrants is the climate, also appreciated by tourists. Seniors are also invited by the tourist infrastructure and the relatively low cost of living and accommodation. Pension migration to foreign enclaves is strongly supported by tourism, which has generated international transport links and a number of service points where foreign languages are spoken. Elements attracting tourists are also attractive for emigrants and settlers (Buller & Hoggart, Citation1994).

Wiseman (Citation1980) maintains that pension migration should be perceived as a process and not as a single act. Also, Wiseman and Roseman (Citation1979) claim that retirement migration is a two-stage process, involving the migration decision and the choice of destination. Tourism often has a conclusive influence on the latter. Cuba (Citation1991) presents an alternative point of view, stating that the destination is first selected by means of holiday visits, and then follows a decision to live there. The number of final destinations determines the difference between the two models. The model by Cuba assumes selecting only one destination, whereas by Wiseman and Roseman allows for a wider range of options. However, research has shown that the same number of respondents indicated both one place and a few places that could be inhabited. The most common alternative was a destination in Europe.

Cribier (Citation1982), when describing French pension migrations, indicates three destination types:

return to the areas of origin;

family reunification, moving close to children and grandchildren;

searching for areas of high recreational value.

Wiseman and Roseman (Citation1979) specify that the American context of mass migration is slightly different, but there is evidence that family ties and the search for destinations of tourist value are also important.

Rodríguez et al. (Citation1998) reported that the majority of pensioners on the Costa del Sol coming from Northern Europe had been on vacation there before. This remains in line with a study by Williams, King, Warnes, and Patterson (Citation2000), who observed that nearly 3/4 of the study subjects had visited their destination during holidays, especially with reference to the Algarve and the Costa del Sol. Previous work or family ties were relatively more important in the case of Tuscany and Malta, but tourism still accounted for almost half of the respondents’ indications.

Another important factor linking tourism with retirement migration is possessing a second home, but on condition that visits are intensified, starting with leisure and seasonal ones, which then lead to permanent migration. A study by Williams et al. (Citation2000) confirms the role of possessing a second home in all four case studies, especially with regard to the Algarve (49.8%) and Tuscany (47.2%), but also to the Costa del Sol (34.0%) and Malta (28.2%). Second homes may become the first ‘permanent’ homes for migrant pensioners at their destination. The individual experience in tourist travel also plays an important role in the choice of destination.

As expected, the relationship between tourism and migration is very complex. Individual places can be experienced by tourists and this provides a direct insight into the reality of living there in the future.

The growing number of elderly people in Poland may become an important source of benefits for the tourism industry. Patkowska, Pytel, Oleśniewicz, and Widawski (Citation2017) indicate that the most frequently mentioned activities undertaken by the elderly include: watching TV, going to church, meeting friends at home, reading books, magazines, newspapers, and listening to the radio and music. This is the current situation of Polish seniors, but in the future, thanks to the growing interest in a healthy and active lifestyle and the growing awareness of the importance of tourism and recreation for improving the quality of life, the form of activity of the elderly will probably change. Both tourism and recreation, and especially physical activity, will be a key and integral component of a healthy lifestyle. Recreation is a factor that prevents aging through physical activity. It is an inseparable element of premature aging prevention and gerontological rehabilitation. Therefore, it seems that recreation will become a new trend among the future senior society. The seniors segment cannot be underestimated, because, as T. Olejniczak (Citation2015) points out, a person who enters the old age phase (conventionally it is 60 years old) will remain a consumer for 18 years (for men) and 23 years (for women). Additionally, there are also other advantages for tourism in the elderly segment. Belong to them:

(a). the growing percentage of elderly people in society,

(b). a lot of free time with seniors,

(c). increase in seniors’ income,

(d). no family obligations,

(e). the improving health of seniors, and

(f). high tendency to travel out of season.

All this means that in the future the senior segment will play a very important role in the functioning of the tourism industry. This phenomenon can be observed very well in Western Europe, but in Poland, it is only beginning to develop.

Research methodology

In order to answer the research question, the primary quantitative research was carried out, which consisted in collecting information from respondents through a standardized questionnaire. The study involved 530 people who had changed their place of residence on retirement. The obtained data were systematized with statistical methods. The matrix of the sampling method was the mechanism of stratified (proportional) random sampling. It consists in dividing the general population into strata (here, provinces) and directly selecting random samples from each stratum. The population was divided into strata in such a way that each element entered only one stratum and entered one of them. With the population of 37,216, level of confidence of 98%, fraction volume of 0.5, and maximum error of 5%, the required number of study participants equalled 533.

To systematize the reasons for seniors’ migrations, a cluster analysis (Ward’s method) was applied. The method allows to combine multiple objects without first providing the number of clusters, with the primary assumption that each object constitutes a separate cluster, and then the most similar objects are grouped, until one cluster containing all observations is created.

The distance of a new cluster from any other one is determined with the following formula:

(1)

(1) where

r – cluster numbers different from p and q

Dpr – distance of a new cluster from cluster numbered r

dpr – distance of a primary cluster p from cluster r

dqr – distance of a primary cluster q from cluster r

dpq – distance between primary clusters p and q

a1, a2, b – parameters determined by the following formulas in the Ward’s method:

(2)

(2) where n denotes the number of single objects in particular objects.

The end result is a dendrogram, i.e. a tree hierarchy of a set, which illustrates not only the general similarity structure, but also the subsequent stages of generalizing the degree of the set similarity (Runge, Citation1988). Cluster analysis is therefore a tool for data analysis, whose aim is to arrange objects in groups in such a way that the degree of association of objects with objects belonging to the same group is as high as possible, and that with objects from other groups as small as possible.

The dendrogram analysis should start with objects that constitute their own class; then we lower the uniqueness criterion, i.e. the threshold that determines the decision to assign two or more objects to the same cluster. In this way, we bind more and more objects together and combine them into bigger and bigger clusters, which are more and more different from each other. The end result is a combination of all objects. On the graph axis, agglomeration distances are identified. The method employs measures of distance between objects, with Euclidean distance as the most popular one. It reflects the real geometrical distance between objects in space. Determining the distance between new clusters requires the agglomeration principle, which informs us when two clusters are similar enough to be combined. The applied Ward’s method is characterized by using the analysis of variance attitude to estimate distances between clusters.

In order to identify the main groups of coherent causes of migration, the survey included questions asked to respondents in the questionnaires described above. The 18 questions concerned the reason for the pensioner’s change of residence. The calculations and dendrogram were performed in the Statistica software.

Results

More than 47% of all respondents indicated that they had earlier gone to the place of migration for their summer holidays. Pensioners charmed by the beauty of nature decided to change their place of residence. Their migration was year-round. Only 16% of the survey participants left home for winter; they moved mostly to their children living in the city, where they did not have to worry about heating or snow clearance, which are the most burdensome activities for seniors.

The conducted research allows to determine the profile of an elderly tourist migrant. This is most often a woman, well educated, aged 60–70 years, making a living from retirement. A detailed analysis shows that 58% of those who had previously travelled to the place of migration were women and 42% were men. The majority of these people had higher (35%) or secondary (32%) education. The analysis of the age structure indicates that seniors aged 60–64 years and 65–69 years constituted 29% each, and those aged 70–74 years comprised 13%. After migration, 84% of these people made a living from their pensions and only 5% from their salaries. Over 97% of the respondents indicated that they had moved to a new place not to work there.

The seniors pointed out many different causes of migration during retirement. The main ones were purchasing a house (37%) and improving the living standards and quality of life (34%). Over 17% of all studied Polish migrant pensioners indicated that they had permanently changed their place of residence because they had found a place of high tourist attractiveness and wanted to live there.

The cluster analysis with the Ward’s method allowed to systematize the reasons for seniors’ migrations. After obtaining a dendrogram for further research stages, it was cut at the position of link 30, which resulted in achieving five clusters.

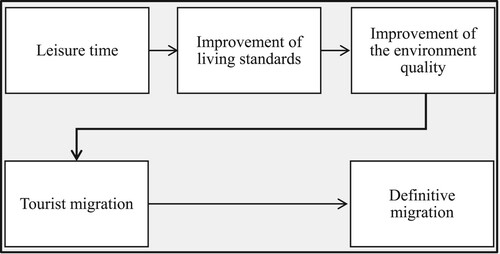

The analysis made it possible to identify the main types of permanent migration causes. Within the obtained cluster III – of tourist type – three responses were identified. These referred to the tourist attractiveness of the location, as well as to improving the living standards and the environment quality (). This allows one to maintain that the seniors moved to places where they found a clean environment of considerable tourist value. The migration improved their living standards and quality of life.

Table 1. Dendrogram clusters division into groups.

People for whom tourist attractiveness was an important factor of migration were 50% men and 50% women. Most of them, as many as 42%, had secondary education; 28% presented higher, 15% vocational, and 15% primary education. The majority were aged 60–64 years (34%) or 65–69 years (32%).

Among the respondents for whom tourist attractiveness was a factor of permanent migration, 48% indicated that migration resulted in a definite improvement of the living standards and quality of life. As many as 57% also reported that migration contributed to better climate and environmental conditions ().

Table 2. Responses regarding reasons for tourist migration.

After migration to a location of tourist attractiveness, 61% lived in an apartment and 34% in a house. Over 65% of the respondents indicated that the decision to migrate was not problematic for them. This probably resulted from the fact that 55% of the seniors migrated with their spouse and 10% with their spouse and children. There were 25% of lone migrants.

The remaining groups of migration reasons implied that an important role was also played by motives related to family and finances, family, economy, and health.

The classification of the reasons for the migration of pensioners in Poland established by means of cluster analysis has brought important quantitative and qualitative information about seniors’ migration, both from a cognitive and practical point of view. The agglomeration method has led to the identification of classes of objects most similar to each other in terms of their assumed characteristics and at the same time maximally different from objects in other clusters. Specifying these clusters allows to reveal the existing regularities between the objects and their distinctive features and to formulate conclusions.

Discussion

Currently, seniors are perceived as an important segment of the tourist market. Therefore, their participation in tourism is an issue that both researchers and practitioners are paying attention to. The aging society and thus the changing demographic structure of the population pose new challenges, which require much more extensive analysis than has been the case so far.

The results of the research conducted in Poland, i.e. a Central European country, are in many respects consistent with those of Western European investigators. The authors pointed at the essential role of earlier trips and recreation in the decisions on migration to places of tourist attractiveness. As mentioned in the Results section, as many as 47% of all respondents who migrated for tourist reasons indicated that they had earlier gone to the place of migration for their summer holidays. Similar studies were performed by Williams et al. (Citation2000). They analysed the association between pension migration and tourism in terms of changing social relations. They examined three issues. The first one was the role of tourism in defining the search for international spaces. The researchers tried to show previous connections with destinations by holiday trips and presented the phenomenon of second homes. The second point was to indicate that pension migration covered the complex issues of identity, consumption, and lifestyles. The study was conducted with a view to the emergence of new forms of lifestyles, as many retired people are looking for entertainment in the place where they migrate. The third aspect was that retired migrants became both potential participants and recipients of tourism.

Both the authors of this article and other researchers have tried to understand the mechanisms of pensioners’ migration. We determined that for 48% of the respondents, the improvement of the living standards and quality of life was important when taking the decision on tourist migration. Improvement of climate and environmental conditions turned out significant for 57% of the surveyed seniors. Rodríguez (Citation2001) aimed to deepen the understanding of the factors that led many older Europeans from Northern Europe to make the transition from tourism to migration. Despite considerable research difficulties, the author, considering the large scale of the influx of foreign tourists and residents, undertook a scientific analysis of this phenomenon. Previous experiences of migrants as tourists and their personal confirmation of a mobile lifestyle were highlighted. The article also discusses the attractiveness of the natural environment of the Costa del Sol. Besides, the author indicated the impact of retired foreign populations on target areas and future migration trajectories based on tourism. O’Reilly (Citation2003), using ethnographic data, examined the migration experience of three groups of British migrants in Spain: retired migrants, migrant entrepreneurs, and economically active consumption-driven migrants. He observed that the patterns of migration were inseparably linked to the history of tourism and previous British tourist travels to Spain. He also argued that theories of tourism as an escape could explain the behaviour of some migrants.

The results obtained by the authors allowed to indicate a change in pensioners’ lifestyle through permanent migration. The authors also indicated the main types of reasons for permanent migration. Within the obtained cluster III – of tourist type – three responses were identified, which referred to the tourist attractiveness of the location, as well as to improving the living standards and the environment quality. Similarly, Cohen, Duncan, and Thulemark (Citation2015) conducted research on mobility in lifestyles. In their paper, they described how migration intersected with mobility as a lifestyle. Their study allows for a broader understanding of the growing relationships among travel, leisure, and migration. The investigators revealed how contemporary lifestyle-based mobility patterns contributed to illustrating the breakdown of the division between work and leisure and to destabilizing the concepts of ‘home’ and ‘out of home’. They also suggested directions for further research on mobility in lifestyles.

The authors of the present article noticed that 55% of the seniors migrated with their spouse and 10% with their spouse and children. There were 25% of lone migrants. This demonstrates that migrants maintained their network of connections and the opportunities for tourist trips to their children and friends. Similar studies were conducted internationally by Casado-Díaz, Casado-Díaz, and Casado-Díaz (Citation2014). They revealed to what extent migrants built up social relations with their neighbours and the host society, while maintaining social links with their countries of origin. They pointed out the role of recreational travel in maintaining more and more dispersed social networks and social capital. Using a case study of 365 British seniors living on the Alicante coast to examine the migration of British pensioners to Spain, they indicated the significance of transnational social networks in the context of international retirement migration.

The links between migration and tourism in Poland are increasingly important. Nearly 20% of seniors move for tourist reasons. As indicated by Illés and Michalkó (Citation2008), tourism and migration are also increasingly significant elements of people’s mobility in Hungary. When reviewing the literature on the relationship between tourism and migration, the researchers identified a number of relevant factors to be applied in the Hungarian case, as well as numerous theoretical and empirical challenges. They highlighted two main issues: the seasonality of tourist flows and purchasing of real estate by foreigners. These topics were examined from a macroscale perspective, with the use of secondary data based on registers. Although the main emphasis was placed on the analysis of spatial patterns of the studied phenomena, social features were also taken into account.

An important factor influencing migration is the appropriate level of infrastructure and economic resources. As implied in the present paper, after migration, 84% of seniors made a living from their pensions and 5% from their salaries. Over 97% of the respondents indicated that they had moved to a new place not to work there. After migration to a location of tourist attractiveness, 61% lived in an apartment and 34% in a house. Migrant pensioners had adequate economic and infrastructural support. Similar research was performed by Gössling and Schulz (Citation2005). On the example of Zanzibar, they pointed out that the development of tourist infrastructure often attracted migrants over long distances, especially in developing countries, where the number of tourists has increased rapidly in the recent years. To analyse the scale and significance of tourism-related migration, they conducted a study in Tanzania. The results indicate that migrants shape the characteristics of Zanzibar’s tourism industry and that their presence has a significant impact on the culture, economy, and environment of the island.

A study by Williams and Hall (Citation2000) provides a broad view of tourism and migration behaviour. The authors analysed the relationship between these two and identified two general but interrelated categories: broad economic and social trajectories and tourist factors. A number of specific forms of tourism-related migration were then considered in the context of these social and economic trajectories. The article discusses labour migration, return migration, business migration, retirement migration, and the migration of second homes. Finally, the need to place research on the links between tourism and migration in a broader debate was emphasized.

Unlike in developing countries, where the study of migration is central, the literature on temporary mobility in the developed world is unsystematic. Bell and Ward (Citation2000), when analysing the reasons for this problem, tried to place tourism in the broader context of temporary and permanent population flows. They suggested that temporary flows had three characteristic dimensions – duration, frequency, and seasonality – which posed a huge methodological challenge. Nevertheless, they argued that both forms of population flow could usefully be classified under production- and consumption-related items. In this context, they studied similarities and differences in the intensity, composition, and spatial patterns of temporary and permanent flows, using data from the Australian census.

It is worth supplementing this discussion with the latest developments affecting the tourism market. With the beginning of the third decade of the twenty-first century, the travel industry has been hit hard by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus outbreak and is currently experiencing one of the most severe crises in history. The hotel, catering and transport sectors suffered the most, as they had to reduce their activities for a certain period. UNWTO World Tourism (Citation2021) reported that international tourist arrivals fell by an average of 74% in 2020 compared with level from 2019. The associated reaching loss USD 1.3 trillion in export revenues, is 11 times more than the losses caused by the 2009 global economic crisis.

According to the Polish Economic Institute (Citation2021), the total share of tourism in the creation of national GDP in Poland in 2018 was 4%, and the tourism industry is an important element of the labour market in Poland and maintains a total of nearly 1.4 million jobs. The multiplier effect is 5.3, thus each PLN 1.0 generated in the tourism industry generates an additional PLN 4.3 of added value for the entire economy.

Therefore, the epidemic crisis and the crisis in the tourism industry have an impact on the participation of seniors in tourist travel. As already mentioned, the domain of seniors’ trips is the implementation of health goals, among others in spas. However, health resorts that are part of the health care system in Poland were included in the epidemic protection program, performing vaccinations or serving as places of isolation of patients (Szromek, Citation2021). Although with the reduction of the next wave of disease (March 2021), tourist activity was restarted, the return to the pre-pandemic situation is estimated for 2023 (Goodgrer & Kieran, Citation2020). This is due not only to the limitations associated with the fear of illness, but also the change of the current form of meetings and conferences to meetings held remotely via the Internet. Until then, the tourist movement of seniors may be an extremely important catalyst for the revitalization of the tourism industry. The reason for this is especially the lack of seasonality of seniors’ trips, which can contribute to significant support for the tourism industry.

Conclusions

The aim of the article was to show the influence of tourist trips of seniors on their future fate. The study allowed to state that the tourist movements of pensioners influenced their definitive migrations. Almost half of the pensioners had previously visited the place where they moved to permanently.

The study results can be presented in the form of a diagram. Seniors, with plenty of free time, start thinking about improving their living standards and the quality of the environment in which they live. For this reason, tourist migrations take place. If seniors find a suitable place, they often move there permanently ().

Figure 2. Scheme of the process of seniors’ migration in the tourist aspect. Source: own elaboration

The information obtained may be used in marketing communication and planning of innovative tourist products. The offer for seniors should be diversified, and in places of tourist attractiveness, apart from hotels, there should be a possibility to purchase an apartment. In tourist marketing activities, it should be pointed out that places of tourist attractiveness invite seniors to live there permanently. British, German, or French seniors do not need to be convinced of the beneficial impact of tourism on their well-being and fitness, but Polish seniors still require encouragement. This is worth allocating appropriate resources because the benefits of increasing the level of tourist activity of older people are significant and can be noticed in various aspects of life, e.g. in property development activities.

The latest events in the world related to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic will also be affected. Tourism of seniors can support the tourism industry, thanks to the features that characterize tourist trips of seniors. It can support the tourism industry thanks to off-season stays, and at the same time reduce the phenomenon of overtourism during the holidays. It is also a research issue, which is the perspective of further research by the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adam R. Szromek

Adam R. Szromek is an Professor of Social Science, lecturer of Management at the Silesian University of Technology in Poland. His research interests focus on heritage tourism and health tourism with special attention to spa tourism management and business models in spa enterprises.

Sławomir Pytel

Sławomir Pytel is an Associated Professor at the University of Silesia in Katowice, specializing in the Earth Sciences. His research interests focus on seniors' displacements and the causes of these displacements. Other research areas are tourism, demographic changes, and aging of the society.

Julita Markiewicz-Patkowska

Julita Markiewicz-Patkowska is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Management and Institute of Tourism and Recreation, Wrocław School of Banking University in Wrocław. Creator of the Management Engineering specialization at Wrocław School of Banking University. Author of several dozen research projects; author or co-author of several dozen scientific publications on tourism, physical activity, management, and environment protection.

Piotr Oleśniewicz

Piotr Oleśniewicz is an Associate Professor, University School of Physical Education in Wrocław; Vice-Director of the Institute of Tourism and Recreation, Head of the Chair of Tourism and the Department of Sociocultural Foundations for Tourism. Chancellor's Proxy for strategy and development at the Humanitas University in Sosnowiec. Research interests: senior tourism, educational tourism, physical activity.

References

- Aktywni+ Program. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/aktywni-ministerstwo-oglasza-nowy-program-dla-seniorow

- ASOS 2014-2020. (2013). Długofalowa Polityka Senioralna w Polsce na lata 2014-2020 w zarysie, Warszawa. Retrieved from. https://das.mpips.gov.pl/source/Dlugofalowa%20Polityka%20Senioralna%20w%20Polsce%20na%20lata%202014-2020%20w%20zarysie.pdf (Access date: 4.08.2021)

- Bąk, I. (2012a). Turystyka w obliczu starzejącego się społeczeństwa. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, 258, 13–23.

- Bąk, I. (2012b). Zastosowanie wybranych metod statystyczno-ekonometrycznych w badaniu aktywności turystycznej seniorów w Polsce. Przegląd Statystyczny, 59(special issue 2), 312–332.

- Bell, M., & Ward, G. (2000). Comparing temporary mobility with permanent migration. Tourism Geographies, 2(1), 87–107. doi:10.1080/146166800363466

- Buller, H., & Hoggart, K. (1994). International counterurbanization: British migrants in rural France. Aldershot: Avebury.

- Casado-Díaz, M. A., Casado-Díaz, A. B., & Casado-Díaz, J. M. (2014). Linking tourism, retirement migration and social capital. Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 124–140. doi:10.1080/14616688.2013.851266

- Central Statistical Office, Retirement and other pensions. (2019). Warsaw 2020. Retrieved from https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5486/32/11/1/emerytury_i_renty_w_2019.pdf (Access date: 4.08.2021)

- Cohen, S. A., Duncan, T., & Thulemark, M. (2015). Lifestyle mobilities: The crossroads of travel, leisure and migration. Mobilities, 10(1), 155–172. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.826481

- Cribier, F. 1982. “Aspects of retirement migration from Paris: An essay in social and cultural geography.” In Geographical perspectives on the elderly, edited by A. M. Warnes, 111–137. London: David Fulton Publishers.

- Cribier, F., & Kych, A. (1992). La migracion de retraite des Parisiens: une analyse de la propension au départ. Population, 47, 677–718. doi:10.2307/1533738

- Cribier, F., & Kych, A. (1993). A comparison of retirement migration from Paris and London. Environment and Planning A, 25, 1399–1420. doi:10.1068/a251399

- Cuba, L. (1991). Models of migration decision making reexamined: The destination search of older migrants to cape Cod. The Gerontologist, 31(2), 204–209. doi:10.1093/geront/31.2.204

- Goodgrer, D., & Kieran, F. (2020). City tourism outlook and ranking: Coronavirus impacts and recovery. Oxford: Tourism Economics.

- Gössling, S., & Schulz, U. (2005). Tourism-related migration in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Tourism Geographies, 7(1), 43–62. doi:10.1080/1461668042000324058

- Graja-Zwolińska, S., & Spychała, A. (2012). Aktywność turystyczna wielkopolskich seniorów. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, 259, 54–63.

- Hołowiecka, B., & Grzelak-Kostulska, E. (2013). Turystyka i aktywny wypoczynek jako element stylu życia seniorów. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Oeconomica, 291, 165–179.

- Horneman, L., Carter, R. W., Wei, S., & Ruys, H. (2002). Profiling the senior traveler: An Australian perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 41(1), 23–37.

- Illés, S., & Michalkó, G. (2008). Relationships between international tourism and migration in Hungary: Tourism flows and foreign property ownership. Tourism Geographies, 10(1), 98–118. doi:10.1080/14616680701825271

- Karn, V. A. (1977). Retiring to the seaside. Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- King, R., Warnes, T., & Williams, A. (2000). Sunset lives: British retirement migration to the Mediterranean. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

- Lee, S. H., & Tideswell, C. (2005). Understanding attitudes towards leisure travel and the constraints faced by senior Koreans. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 11(3), 249–263.

- Mokras-Grabowska, J. (2010). Program “Europe Senior Tourism” – założenia, realizacja, efekty ekonomiczne. Łódź: Wyższa Szkoła Turystyki i Hotelarstwa w Łodzi.

- Niezgoda, A., & Jerzyk, E. (2013). “Seniorzy w przyszłości na przykładzie rynku turystycznego.” Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu szczecińskiego. Problemy Zarządzania, Finansów i Marketingu, 32, 475–489.

- O’Reilly, K. (2003). When is a tourist? The articulation of tourism and migration in Spain’s Costa del Sol. Tourist Studies, 3(3), 301–317. doi:10.1177/1468797603049661

- Oberg, S., Scheele, S., & Sundstrom, G. (1993). Migration among the elderly: The Stockholm case. Espace Populations Sociétés, 11(3), 503–514. doi:10.3406/espos.1993.1612

- Ociepka, A., & Pytel, S. (2016). Aktywność turystyczna seniorów w Polsce. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. Ekonomiczne Problemy Turystyki, 2(34), 83–94.

- Olejniczak, T. (2015). Przemiany segmentu konsumentów seniorów w Polsce. Marketing i Rynek, 1(2), 196-210.

- Oleśniewicz, P., & Widawski, K. (2015). Motywy podejmowania aktywności turystycznej przez osoby starsze ze Stowarzyszenia Promocji Sportu FAN. Rozprawy Naukowe Akademii Wychowania Fizycznego we Wrocławiu, 51, 15–24.

- Patkowska, J. M., Pytel, S., Oleśniewicz, P., & Widawski, K. (2017). The 21stcentury trends in senior tourism development among the baby boomer generation. Proceedings Book, 280–299.

- Polish Economic Institute. (2021). Retrieved from https://pie.net.pl/polska-turystyka-generuje-13-proc-pkb-na-ile-ucierpi-przez-pandemie/ (Access date: 4.08.2021)

- Pytel, S. (2014). Atrakcyjność turystyczna miejsc migracji seniorów z województwa śląskiego. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. Ekonomiczne Problemy Turystyki, 1(25), 327–340.

- Rodríguez, V. (2001). Tourism as a recruiting post for retirement migration. Tourism Geographies, 3(1), 52–63. doi:10.1080/14616680010008702

- Rodríguez, V., Fernandez-Mayoralas, G., & Rojo, F. (1998). European retirees on the Costa del Sol: A cross-national comparison. International Journal of Population Geography, 4(2), 183–200. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199806)4:2 < 183::AID-IJPG101 > 3.0.CO;2-8

- Runge, J. (1988). Rozkłady przestrzenne dojazdów do pracy dla miast województwa katowickiego w latach 1973 i 1978. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Śląskiego w Katowicach, 878(11), 101–118.

- Senior + Program. (2021). http://senior.gov.pl/program_senior_plus (Access date: 4.08.2021)

- Stasiak, A. (2011). Perspektywy i kierunki rozwoju turystyki społecznej w Polsce. Łódź: Wyższa Szkoła Turystyki i Hotelarstwa w Łodzi.

- Stončikaitė, I. (2021). Baby-boomers hitting the road: The paradoxes of the senior leisure tourism. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 1–13. doi:10.1080/14766825.2021.1943419

- Szromek, A.R. The role of health resort enterprises in health prevention during the epidemic crisis caused by COVID-19. Journal of Open Innovation Technology Market and Complexity. 2021, 7, 133. doi:10.3390/joitmc7020133

- Śniadek, J. (2007). Konsumpcja turystyczna polskich seniorów na tle globalnych tendencji w turystyce. Gerontologia Polska, 15(1–2), 21–30.

- UNWTO. (2021). UNWTOWorld Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex, January 2021. UNWTO World Tour. Barom. 2021, 19, 1–42.

- Warnes, A. M. (1993). “Demographic ageing: Trends and policy response.” In The changing population of Europe, edited by D. Noin and R. Woods, 82–99. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Widawski, K. (2011). Wybrane elementy dziedzictwa kulturowego środowiska wiejskiego – ich wykorzystanie w turystyce na przykładzie Hiszpanii i Polski. Rozprawy Naukowe Instytutu Geografii i Rozwoju Regionalnego, 17, 1–267.

- Williams, A., & Patterson, G. (1998). An empire lost but a province gained: A cohort analysis of British international retirement in the Algarve. International Journal of Population Geography, 4(2), 135–155. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199806)4:2 < 135::AID-IJPG99 > 3.0.CO;2-6

- Williams, A. M., & Hall, C. M. (2000). Tourism and migration: New relationships between production and consumption. Tourism Geographies, 2(1), 5–27. doi:10.1080/146166800363420

- Williams, A. M., King, R., Warnes, A., & Patterson, G. (2000). Tourism and international retirement migration: New forms of an old relationship in Southern Europe. Tourism Geographies, 2(1), 28–49. doi:10.1080/146166800363439

- Williams, A. M., King, R., & Warnes, T. (1997). A place in the Sun: International Retirement Migration from Northern to Southern Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 4(2), 115–134. doi:10.1177/096977649700400202

- Wiseman, R. F. (1980). Why older people move. Research on Aging, 2(2), 141–154. doi:10.1177/016402758022003

- Wiseman, R. F., & Roseman, C. C. (1979). A typology of elderly migration based on the decision making process. Economic Geography, 55(4), 324–337. doi:10.2307/143164